Abstract

This paper describes a method to reconstruct complete birth histories for women in the 1900 and 1910 U. S. census IPUMS samples. The method is an extension of an earlier method developed by Luther and Cho (1988). The basic method relies on the number of children ever born, number of children surviving, number of children coresident in the household and age-specific fertility rates for the population to probabilistically assign an “age” to deceased and unmatched children. Modifications include the addition of an iterative Poisson regression model to fine-tune age-specific fertility inputs. The potential of complete birth histories for the study of the U.S. fertility transition is illustrated with a few examples.

Reconstruction of Birth Histories using Children Ever Born and Children Surviving Data from the 1900 and 1910 United States Censuses

Research on the fertility transition in the United States has been hampered by poor data availability. A national birth registration system was first established for 10 states and the District of Columbia in 1915 and not completed until 1933, near the end of the century-long fertility decline. In the absence of birth registration records, most researchers have turned to census data, including IPUMS microdata samples and complete-count datasets (Ruggles et al. 2018). Census data have several drawbacks for the study of fertility, however. Most obviously, because most censuses documented only the living population and did not identify relationships outside the household, we have no way of knowing whether an enumerated woman had experienced the death or departure from the household of one or more of her children. As a result, census data are of limited use in addressing several important questions in the literature, such as the timing of births, the relative contribution of starting, stopping, spacing, and postponement in the fertility transition, and related questions about the knowledge, acceptability, and use of birth control (Timæus 2008, Alter 2016).

In this paper, I describe a method to reconstruct birth histories for women in the 1900 and 1910 census IPUMS samples that allow direct measurement of birth intervals, parity progression measures by women’s age and duration of marriage, and the construction of birth timing models. The method is an extension of an earlier method developed by Luther and Cho (1988) and can be applied to censuses and surveys with number of children ever born (CEB) and number of children surviving (CS) data. Briefly, the method uses CEB, CS, the number and ages of coresident children, and age-specific fertility rates as inputs to probabilistically assign an age to women’s deceased and “unmatched” children. (Although nonsensical, I follow Luther and Cho in referring to the “age” of a deceased child as the age the child would have been if he or she had survived to be enumerated by the census. I also follow Luther and Cho and the creators of the “own-child” method (Cho, Retherford and Choe 1986) in designating living children linked to their coresiding mothers in the census as “matched” own children and living children non coresident with their mothers as “unmatched” children.) Because a child age j born to a woman age g at census date t represents, on average, a birth to a woman at exact age g – j at time t – j – 0.5, combining imputed ages of deceased and unmatched children with the observed ages of matched children results in each woman’s complete birth history, up to the date of the census. The extension to Luther and Cho’s method described here is the addition of an iterative Poisson regression model to fine-tune age-specific fertility inputs for individual women.1 The regression includes social, economic and demographic covariates of fertility available in the census, including each woman’s birth cohort, census region, rural/urban residence, literacy, race, place of birth, parents’ places of birth and—for women currently-married with spouses present in the household—her spouse’s occupation, literacy, place of birth, parents’ places of birth and age differential from spouse. After describing Luther and Cho’s method and the proposed extension, I illustrate the potential of complete birth histories for the study of the U.S. fertility transition with a few examples.

Background and Data Considerations

According to the most frequently-cited estimates (Coale and Zelnik 1963), fertility in the United States fell at a more or less constant rate from 7.0 children per woman in 1800 to 2.2 in 1940. In addition to its relatively early onset—prior to significant industrialization, urbanization, mortality decline, and the onset of fertility decline in most other countries—the decline appears to have been initiated by couples employing an unusual amount of birth “spacing” behavior, the intentional lengthening of intervals between births relative to prior generations (Haines 1989). Fertility decline in most European countries, in contrast, was driven by couples’ increasing practice of “stopping” behavior or “parity-dependent control,” the cessation of childbearing after reaching a target number of children (Knodel 1974; Knodel and van de Walle 1979; Alter 2016). New England couples and Quaker women in the Mid-Atlantic region, who were on the vanguard of fertility decline in the United States, may have started intentionally spacing births as early as the late eighteenth century (Wells 1971; Main 2006), several generations before parity-dependent control can be detected in the mid nineteenth century (Hacker 2016). A study of fertility decline among the predominately-Mormon settlers of Utah and their descendants also demonstrated significant birth spacing—although in combination with significant stopping behavior—beginning with the 1845–49 birth cohort (Anderton and Bean 1985).

Census data have been the basis for most research on nineteenth- and early twentieth-century U.S. fertility. Early studies based on aggregate child-woman ratios (e.g., Easterlin 1976; Vinovskis 1976) have given way to individual-level studies based on IPUMS samples and complete-count datasets (e.g, Dribe, Hacker and Scalone 2014; Hacker 2016), especially for the period after 1850, when mothers can be matched to coresident children in the household.

Investigators have addressed the problem of the unknown number of women’s deceased and non coresident (unmatched) children in census data in two ways. One way is through own-child estimation methods (OCM), a reverse-survival method that adjusts cross-tabulations of the number of mothers and their children by single years of age for estimates of the number of deceased and unmatched children to yield age-specific fertility rates (Cho, Retherford and Choe 1986; Reid et al. 2019). From these rates researchers have estimated the extent of birth stopping behavior in the aggregate population using Coale and Trussell’s m parameter (e.g., Hacker 2003, 2016) and average birth spacing at low parities (Ewbank 1989). These indirect methods have been criticized for their imprecision (e.g., Okun 1995), however, and cannot be used at the individual level. A second approach is to sidestep the issue by modeling couples’ recent “net” marital fertility, or reproduction (e.g., the number of own children less than age five living in the household). Since few children in the United States left the household before age 15 and group differentials in mortality were modest relative to differentials in fertility (Dribe et al. 2014; Scalone and Dribe 2017; Dribe et al. forthcoming), models of reproduction can be useful in identifying the relative importance of social, economic, and demographic factors in the fertility transition. Neither approach, however, allows direct measurement of birth intervals or testing of hypotheses related to birth timing—birth starting, stopping, spacing, and postponement—that dominate the current literature on the European fertility decline (see, for example, Bengtsson and Dribe 2006, van Bavel 2004; Alter 2016).

The 1900 and 1910 censuses provide a partial exception to the shortcomings of U.S. census data. Both censuses asked women the total number of children she had ever borne (CEB) prior to the census. The question counted children across all marriages; a woman giving birth to one child in a first marriage and two children in a second marriage should have reported three CEB on the census. The 1900 and 1910 censuses are also the only U. S. censuses that asked women the total number of her children surviving (CS) at the time of the census. Together, CEB and CS implicitly measure the number of deceased children. With the help of the IPUMS microdata samples of the censuses, which include variables linking mothers to their own-children and spouses, researchers can also determine the number and age of children coresident with their mothers and the number of non coresident (unmatched) children. Additional data of use to researchers interested in birth interval analysis include duration of current marriage (included in both censuses) and number of times married (included only in the 1910 census).

Similar census and survey data exist for other times and places. The 1940–1990 U.S. censuses also asked women the number of children ever born. Unfortunately, these censuses did not include a question on child survival, making it impossible to determine whether children who were not present in the household were missing because they were deceased or because they resided elsewhere. As discussed further below, the ability to determine why is child was not present in the household is critical in determining birth probabilities when imputing ages. The 1911 Census of Ireland the 1911 Census of England and Wales asked women the number of children born in her current marriage, the number of children still living, and the number of children that had died. Many censuses and surveys for developing nations with poor vital registration systems have included CEB and CS data to allow estimation of fertility and child mortality. Luther and Cho demonstrated their method of birth reconstruction using the Korean National Fertility Survey of 1974 (1988). IPUMS International currently includes 66 census samples containing children ever born and children surviving data from 30 nations available for public use (Minnesota Population Center 2019).

Methodological approaches to reconstructing birth histories and the comparative potential of the results will depend in part on differences in the wording of CEB and CS questions in the census or survey, instructions to enumerators, universe of women asked the questions, availability of other questions included in the census or survey, and availability of microdata. Differences between how the 1900 and 1910 U.S. censuses collected CEB and CS data were minor. The 1900 census instructions to enumerators mentioned only that the “object is to get the number of children each woman has had, and whether the children are or are not living on the census day.” The 1910 instructions emphasized that the answer should include “children by any former marriage as well as by her present marriage” and that the number should not include “children which her present husband may have had by a former wife, even though they are members of her present family” (IPUMS USA 2019).

Instructions to enumerators in both years emphasized that stillbirths were not be counted. Enumerators were instructed to record a “zero” if the woman had not borne children. Despite these instructions, 4.7 percent of ever-married women in the 1900 and 1910 IPUMS samples had blank, illegible or inconsistent responses for CEB and CS. In these cases, the IPUMS project imputed a response from a donor woman in the dataset with the same age, marital status, race, and number of coresiding own-children in the household.2 For 43 percent of these cases the IPUMS project allocated zero children ever born. Virtually all these women had no children present in the household. The remaining 57 percent of women with missing or invalid CEBs—most of whom had own children present in the household—received a non-zero allocation from a donor woman with the same characteristics. These allocations are consistent with Haines’ prior assessment of the potential impact of women with missing 1900 and 1910 CEB data to the results of the two-census parity increment method. He concluded that the most consistent results were obtained when half of all women with missing parity data in 1900 and 1910 were classified as having zero parity and the other half were assigned parities typical of women with valid data in the same age group (Haines 1989).

Including cases with imputed CEB and CS data had a negligible impact on the overall results. The average CEB for all women age 15–68 in the combined IPUMS 1900 and 1910 samples, for example, was 3.1808 when all women, including women with imputed CEBs were included, and 3.1813 when only women with non-imputed data were included. Investigators concerned that the imputation procedure may bias their results can use the quality flag variables included in the IPUMS to exclude women with imputed CEB and CS data. To the extent that the imputation procedure was correct on average, however, excluding cases with missing CEB and CS data has the potential to introduce bias, rather than removing it. Because the IPUMS allocations are consistent with Haines’ independent assessment, I included cases with imputed CEB and CS in the subsequent analysis.

The most significant difference between the 1900 and 1910 U.S. censuses was in the universe of women asked the questions. The 1900 U.S. census instructions emphasized that the CEB and CS questions applied “only to women.” No mention was made of women’s marital status or age. In contrast, the 1910 census instructions specified that the questions applied only to women “who are now married, or who are widowed, or divorced.” Although it is unclear how assiduous enumerators were in inquiring about the fertility of unmarried women, some recorded CEB and CS answers for single women in 1900, suggesting that the children of these women were illegitimately born. Unfortunately, the IPUMS project chose to enforce a consistent universe of ever-married women and discarded the small number of responses from single women in 1900.

The lack of data on illegitimate children can create significant bias in the calculation of age-specific marital fertility rates for young women using OCM (Reid et al. 2019). Although we lack the necessary data for a full assessment, the available evidence suggests the potential bias in reconstructed birth histories from excluding births to single women is insignificant for most results, especially if analyses are limited to ever-married women or to women in birth cohorts who had completed most of their childbearing years. There are several reasons why. To begin with, out-of-wedlock births were relatively rare at the turn of the twentieth century. In 1940, when vital registration data first become available in the United States, just 7.1 births per thousand were to single women. Even if we allow for the possibility of higher illegitimacy rates in earlier generations, the illegitimate birth rate was likely very low for women in all but the youngest age groups.3 Second, women in both censuses who subsequently married after giving birth to an illegitimate child should have reported the child as part of her total CEB in the 1900 and 1910 censuses. A 60-year old woman enumerated by the 1900 census who gave birth to an illegitimate child in 1860 at the age of 20, for example, should have reported the child if she was ever married in the 40-year interval between 1860 and 1900. Since about 93 percent of women born in 1840 eventually married (see Table 4 below), it is likely that most illegitimate children were counted by the census. Finally, there is evidence to suggest that many single women with illegitimate children present in the household misreported their marital status as marital status as widowed, divorced or married with spouse not present, and thus should have answered CEB and CS questions (Preston et al. 1992). Overall, the evidence suggests that a very low proportion of births are missing from CEB and CS data because of illegitimate births among single women, with the possible exception of births to single women age 15–19 and 20–24 at the time of the 1900 and 1910 censuses. Users relying on CEB and CS data to represent the fertility of the overall female population, rather than the ever-married female population, should of course be aware that CEB and CS data for younger women may be biased downwards by unrecorded births to single women.

Table 4.

Descriptive Statistics, Women’s Imputed Birth Histories, 1900 and 1910 IPUMS samples

| All women, 15–68 | Ever-married women, 15–68 | Currently-married women, 15–68 | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| born 1840–49 | born 1840–49 | born 1840–49 | |||||||

| Census Year | 1900 | 1910 | (Diff.) | 1900 | 1910 | (Diff.) | 1900 | 1910 | (Diff.) |

|

|

|

|

|||||||

| Children ever born | 4.73 | 4.90 | 0.17 | 5.11 | 5.24 | 0.13 | 5.32 | 5.35 | 0.03 |

| Children surviving | 3.38 | 3.34 | −0.04 | 3.65 | 3.57 | −0.08 | 3.85 | 3.73 | −0.12 |

| Mean age at birth | 29.27 | 29.44 | 0.17 | 29.27 | 29.44 | 0.17 | 29.59 | 29.60 | 0.01 |

| Mean age at first birth | 22.00 | 21.93 | −0.07 | 22.00 | 21.93 | −0.07 | 22.00 | 21.92 | −0.08 |

| Mean age at last birth | 36.92 | 37.48 | 0.56 | 36.92 | 37.48 | 0.56 | 37.56 | 37.87 | 0.31 |

| Proportion childless | 0.165 | 0.138 | −0.028 | 0.100 | 0.078 | −0.022 | 0.098 | 0.080 | −0.018 |

| Proportion single | 0.073 | 0.065 | −0.008 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 |

| Proportion Widowed, Divorced or Separated | 0.273 | 0.436 | 0.163 | 0.294 | 0.466 | 0.172 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 |

| Parity Progression Ration (Pj to P2) | 0.90 | 0.90 | 0.01 | 0.90 | 0.90 | 0.01 | 0.91 | 0.91 | 0.00 |

| Parity Progression Ration (P2 to P3) | 0.87 | 0.88 | 0.00 | 0.87 | 0.88 | 0.00 | 0.88 | 0.89 | 0.00 |

| Parity Progression Ration (P3 to P4) | 0.86 | 0.86 | 0.00 | 0.86 | 0.86 | 0.00 | 0.87 | 0.87 | 0.00 |

| Parity Progression Ration (P4 to P5) | 0.84 | 0.84 | 0.00 | 0.84 | 0.84 | 0.00 | 0.85 | 0.84 | −0.01 |

| Birth interval (years) (P1 to P2) | 4.10 | 4.23 | 0.13 | 4.10 | 4.23 | 0.13 | 4.09 | 4.17 | 0.09 |

| Birth interval (years) (P2 to P3) | 3.39 | 3.60 | 0.21 | 3.39 | 3.60 | 0.21 | 3.39 | 3.57 | 0.18 |

| Birth interval (years) (P3 to P4) | 3.13 | 3.28 | 0.15 | 3.13 | 3.28 | 0.15 | 3.13 | 3.29 | 0.17 |

| Birth interval (years) (P4 to P5) | 2.98 | 3.12 | 0.13 | 2.98 | 3.12 | 0.13 | 2.99 | 3.15 | 0.16 |

| Age-Specific Birth Rates | |||||||||

| 15–19 | 0.072 | 0.072 | 0.000 | 0.077 | 0.077 | 0.000 | 0.078 | 0.077 | −0.001 |

| 20–24 | 0.199 | 0.206 | 0.008 | 0.214 | 0.221 | 0.006 | 0.218 | 0.222 | 0.005 |

| 25–29 | 0.221 | 0.227 | 0.006 | 0.239 | 0.243 | 0.004 | 0.243 | 0.247 | 0.003 |

| 30–34 | 0.206 | 0.210 | 0.005 | 0.222 | 0.225 | 0.003 | 0.230 | 0.228 | −0.002 |

| 35–39 | 0.153 | 0.160 | 0.006 | 0.166 | 0.171 | 0.005 | 0.177 | 0.175 | −0.003 |

| 40–44 | 0.078 | 0.084 | 0.006 | 0.084 | 0.090 | 0.006 | 0.095 | 0.096 | 0.001 |

| 45–49 | 0.015 | 0.014 | −0.001 | 0.016 | 0.015 | −0.001 | 0.018 | 0.017 | −0.001 |

| N | 125,469 | 17,926 | 116,310 | 16,760 | 82,094 | 8,945 | |||

Notes: Estimates for all women were constructed by adding single women in the 1900 and 1910 IPUMS samples to the ever-married women with reconstructed birth histories described in the text. Single women’s children ever born and age-specific birth rates were assumed to be zero. All other information for single women was set to system missing. Ever-married women include widowed, divorced, currently-married women with spouses not present and currently-married women with spouses present. Currently-married women included only women with spouses present in the 1900 and 1910 IPUMS samples. For women in the 1900 IPUMS sample, 63 percent of all births were imputed using the procedure described in the text. Among women in the 1910 IPUMS sample, 81 percent of births were imputed.

Source: 1900 and 1910 IPUMS datasets (Ruggles et al. 2018).

The 1910 U.S. census asked currently-married men and women the duration in years of their current marriage and the number of times they had been married, allowing the possibility of modeling birth probabilities as a function of women’s marital duration—or marital duration and age—instead of age only, but only for women in their first marriages. Unfortunately, the number of times married variable was not captured by Ancestry.com in their transcription of the 1910 census and is not available in the 1910 complete-count IPUMS dataset. The 1900 census, moreover, did not ask respondents the number of times they had been married, making it impossible to use the same approach in that census. It is therefore only possible to determine the age at first marriage for a small subset of women in the one percent 1910 IPUMS sample. In the analysis that follows, therefore, I employ fertility schedules by women’s ages rather than their marriage durations, which allows me to construct birth histories for women in the five-percent 1900 IPUMS sample, for currently divorced and widowed women in the one-percent 1910 IPUMS sample, and ultimately for all ever-married women in both the 1900 and 1910 IPUMS complete-count datasets. I limit the analysis to women currently age 15–68 in both samples. Although preliminary 1900 and 1910 complete-count datasets are now available, the data are not fully coded and more difficult to analyze. The methods described here should transfer easily to the final versions of the complete-count datasets when released by the Minnesota Population Center.

In contrast to the U.S. 1900 and 1910 U.S. censuses, which asked ever-married women the total number of CEB and CS across all of her marriages, the 1911 Census of Ireland and the 1911 Census of England and Wales asked currently-married women the number of children born, number of children surviving, and number of children dying in her current marriage and the duration of that marriage. There are several advantages to having CB and CS apply only to women’s current marriages. Researchers will be confident that women’s birth histories were not interrupted by unobserved periods of widowhood or divorce. Researchers will also be able to model birth probabilities as a function of marital duration and age (not age only) and analyze the interval between marriage and first birth in the reconstructed birth histories. Timæus, Reid, Jaadla, and Garrett (2019) are currently working on such a project for England and Wales. In contrast, birth histories reconstructed with U.S. data will include unknown periods when some women were widowed or divorced. In addition, other than the date of first birth, reconstructed birth histories for U.S. women will have an indeterminate start to the risk of childbearing and cannot be used to model the duration between marriage and first birth.4 There are several major disadvantages to the Irish, English and Welsh census data, however. First, the restriction of the CEB and CS data to the marriages of currently-married women eliminates illegitimate births to single women (many of whom will be counted in the U.S. data if the woman subsequently married) and eliminates the births of currently widowed and divorced women (which are included in the U.S. data). In the combined U.S. 1900 and 1910 IPUMS samples, the latter group is responsible for 16.0 percent of all children ever born reported by women age 15–68, and 30.6 percent of all children ever born to women age 50–68. Second, the number of births in women’s previous marriages and their timing will not be known, resulting in partial birth histories for a large but unknown number of currently-married women. Researchers relying on birth histories reconstructed with census data from Ireland, England or Wales will not know women’s true parity at the beginning of each birth interval, a critical factor in a couple’s decision to proceed to the next birth and the timing of that birth. Because the chances of being in a second order or higher marriage and having given birth to a child in a previous marriage increases with age, unknown parity will be especially problematic comparing birth intervals among women in different age groups/birth cohorts.5

Before describing Luther and Cho’s method and its application to the U.S. data in more detail, it should be noted that CEB data are an important source on the fertility transition in their own right. Paul David and Warren Sanderson (1987; 1988, 1990) and coauthors (David et al. 1988) have made extensive use of CEB in the 1910 census in several papers describing the potential of “cohort parity analysis,” a method of inferring the extent and timing of marital fertility control from parity distributions of married women by age and marital duration. Jones and Terlit (2008) used CEB data in the 1900, 1910, and 1940–1990 IPUMS samples to examine the impact of spouses’ occupational income score on women’s completed fertility. They concluded that occupational income had a remarkably consistent negative relationship with fertility across time and cross-sectionally and that increasing incomes played a major role in the fertility transition. CEB data have a few significant drawbacks when used this way, however. The dependent variable, completed fertility, is the cumulative result of couples’ marriage and fertility behavior over many years in the past—in some cases decisions made more than 50 years before the census—while independent variables are measured in the present, increasing the chances of measurement bias. We have no way of knowing if the residence and spouse’s occupation recorded for a currently-married woman age 70 in the 1900 census, for example, were the same as the woman’s residence and her spouse’s occupation circa 1860 during her peak childbearing years. In contrast, models of recent net marital fertility employed by other investigators (e.g., Dribe et al. 2014; Hacker 2016) rely on independent variables measured within a few years of a couple’s observed childbearing.

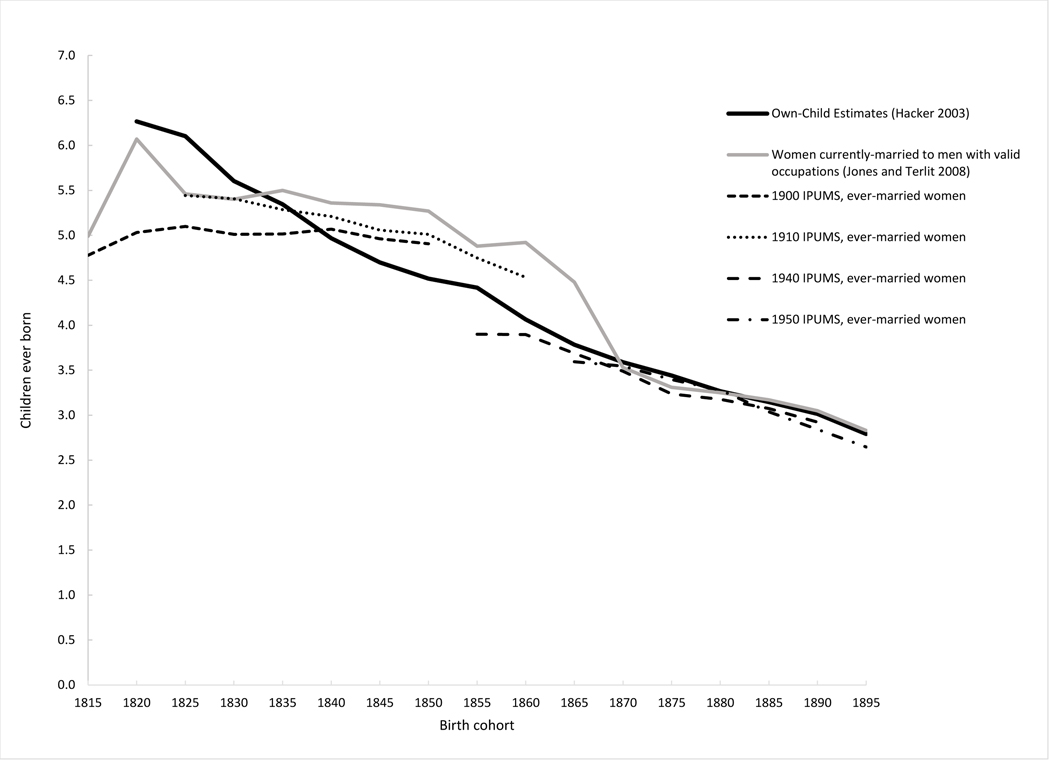

Given the many years lapsing between the births of children and their measurement in the 1900 and 1910 censuses, CEB and CS data are also susceptible to survivorship and recall biases. To explore possible biases, Figure 1 compares estimates of CEB for women in different birth cohorts between 1815 and 1899 using different censuses and estimation methods. Most of the estimates plotted in the figure are CEB data directly reported by ever-married white women age 50–84 in the 1900, 1910, 1940 and 1950 IPUMS samples, who had completed their childbearing (unfortunately, the 1920 and 1930 U.S. censuses did not include a CEB question). The black dashed line for women in the 1900 IPUMS sample, for example, shows the average CEB reported by white women born 1845–49 (who were age 50–54 in the 1900 IPUMS sample), 1840–44 (age 55–59 in the 1900 IPUMS sample), 1835–40 (age 60–64), 1830–34 (age 65–69), 1825–29 (age 70–74), 1820–24 (age 75–79), and 1820–24 (age 80–84). Other black dashed lines shows the average CEB reported by ever-married women by birth cohort in different IPUMS samples. Women in the same birth cohorts were 10 years older in the 1910 IPUMS sample than in the 1900 IPUMS sample. The 1845–49 birth cohort, which was age 50–54 in the 1900 IPUMS sample, for example, was age 60–64 in the 1910 IPUMS samples. Assuming no survivorship or recall biases, and no childbearing past age 50, women in the same birth cohort should have the same average number of CEB in each sample. The solid grey line plots similar CEB estimates constructed by Jones and Terlit (2008) for women in the same IPUMS samples, but with the universe limited to currently married white women who had a spouse present in the household and whose spouse had a valid occupation. When cohorts were estimated in more than one IPUMS sample, Jones and Terlit averaged the estimates. Finally, the solid black line in the figure plots the mean children ever born estimated using OCM analysis of white women in the 1850–1880 and 1900–1940 IPUMS samples (Hacker 2016).6

Figure 1.

Children ever born by mother’s birth cohort, white women in the United States

The figure indicates close correspondence among the various estimates for women born after 1870. For women born prior to 1870, however, there was little agreement among the various estimates for women in the same cohorts, with the widest differences for cohorts born in the early part of the nineteenth century. The OCM-based estimates indicate a long-term and steady decline in CEB by women’s birth cohort, from an average of 6.3 children per woman in the 1820–24 birth cohort to 2.8 children per woman in the 1895–99 birth cohort. Average CEB for ever-married white women in the 1900 and 1910 IPUMS samples show a much flatter fertility decline in the earlier part of the century. CEB estimates for ever-married white women in the 1910 IPUMS sample, for example, fell from 5.4 children in 1820–24 (0.7 fewer children than the OCM estimate) to 5.0 children in 1850–54 (0.5 more children than the OCM estimate). Estimates from the 1900 IPUMS sample indicate a modest increase in the number of CEB between the 1815–19 and 1840–44 cohorts. Jones and Terlit’s estimates indicate little change in CEB between cohorts of women born near the beginning the nineteenth century and cohorts born near the middle of the century. Jones and Terlit’s estimates are also higher than other estimates for most cohorts, no doubt because of their additional selection criterion of currently-married women with spouses present, who presumably experienced less marital disruption than ever-married women.

Although we cannot be certain about the causes of the many discrepancies, the greatest differences occurred prior to the onset of the mortality transition—which began in the United States circa 1870 (Haines 2000)—and are for the most part consistent with what is known about recall and survivorship biases. Several studies have noted that women tend to omit more children as they age, particularly children who died young and children who left home many years prior to the census (Potter 1977; Shryock and Siegel 1973: 511–12; Haines 1989). Recall bias may explain why retrospective CEB estimates for older women in the IPUMS samples tended to be lower relative to OCM estimates than estimates for younger women and why fertility declines based on CEB data are flatter than the decline based on OCM estimates. Interestingly, the period of most-rapid decline in fertility in the Jones and Terlit series – between the 1865–69 and 1870–74 cohorts – corresponds with the greatest shift in years between the IPUMS samples and the age of women reporting CEB. Jones and Terlilt’s estimate of CEB for the 1865–59 birth cohort was obtained from women age 40–44 in the 1910 IPUMS sample, while their estimate for the 1870–74 cohort was obtained from women age 65–69 in the 1940 IPUMS sample. The shift is consistent with expectations about recall bias, with younger women recalling the number of her children more accurately and older women under-reporting the true number. Other biases at clearly at work, however, as the Jones and Terlit’s estimate for younger women in the 1910 IPUMS sample was much higher than other estimates, while their estimate for older women in the 1940 census corresponds well with other estimates, including the OCM estimates. It is possible, of example, that the upward bias to Jones and Terlit’s estimates from relying only on currently-married women with spouses present and with valid occupation offsets the recall bias among older-age women.

Survivorship selection biases likely played a major role in differing cohort estimates prior to the mortality transition. Retrospective CEB estimates are based only on women who survived to the 1900 and 1910 censuses; OCM estimates, in contrast, are based on women who were enumerated in one or more the censuses between 1850 and 1880. Many of these women died in the interval between the enumeration of the 1850 census and the 1900 census. Research is split on the question of whether and how fertility influenced women’s longevity (Hurt et al. 2006; Penn and Smith 2007; Kaptijn et al. 2015; Poulain 2015), but the potential for survivorship bias is large. Nineteenth-century life tables (Hacker 2010) indicate that less than 40 percent of white women age 30 in 1860 survived to age 70 in 1900. If women who died before 1900 were not as physically robust as women who survived, their fertility may have been lower. These women’s fertility would be included in OCM analyses of period fertility, but not in the CEB cohort estimates derived from the 1900 or 1910 censuses. Women with higher fertility were exposed to greater risks of death in childbirth and from related maternal causes, on the other hand, suggesting women with higher fertility would have been less likely to survive to the twentieth century than women with lower fertility. Perhaps tellingly, CEB estimates from the 1910 IPUMS sample are higher than the CEB estimates from the 1900 IPUMS sample for women in the same cohorts, despite these women being ten years older in 1910. Because these women had already survived their childbearing years and the difference is opposite of what is expected from recall bias, the higher CEB estimates in the 1910 IPUMS sample strongly suggests that women’s prior fertility was negatively correlated with their subsequent mortality, at least after menopause.

Some differences between the CEB and OCM estimates and differences between the 1900 and 1910 CEB estimates likely reflect compositional differences in the population included in the estimates. The 1900 and 1910 CEB estimates include immigrant women who arrived shortly before the censuses. These women had more children, on average, than white women in the same cohorts living in the United States between 1850 and 1880 (King and Ruggles 1990; Morgan, Watkins and Ewbank 1992; Hacker and Roberts 2018), increasing CEB estimates relative to OCM estimates and possibly even 1910 CEB estimates relative to 1900 CEB estimates. Finally, although it is unclear how it may have biased responses, differences in the wording of the questions and instructions to enumerators discussed earlier may explain some differences between the 1900 and 1910 CEB estimates for women in some cohorts.

Luther and Cho’s Method of Birth Reconstruction

Luther and Cho presented their method of reconstructing complete birth histories (1988) as an extension of the own-child method (OCM) for censuses and surveys containing retrospective children ever born and children surviving data. In standard OCM analysis researchers first match mothers to their own-children in the household. The matched file is then aggregated by different combinations of mothers’ and children’s ages and adjusted for mortality, unmatched children, and suspected census undercounts to obtain the number of children born to the number of women at each age between 15 and 49 in each year before the census. Back projections are typically limited to 15 years before the census when children increasingly begin to leave home. Dividing the number of births by the number of mothers at each age yields age-specific fertility rates. In the extension proposed by Luther and Cho, children ever born and children surviving data are used to make adjustments at the individual level rather than at the aggregate level. The method probabilistically assigns an “age” (and an associated birth year and mother’s age at birth) to each deceased and unmatched child using age-specific fertility rates for women in the cohort (derived from OCM), age-specific mortality rates, age patterns of unmatched children, and the existing distribution of siblings in the household. For younger women, who tended to have fewer deceased children and a greater proportion of children still living at home, the resulting birth histories (right censored at the date of the census) are typically a combination of a large majority of coresident own children with known ages and a small minority of deceased and non coresident children with imputed ages. Among older women, who tended to have more deceased and fewer coresident children, reconstructed birth histories typically include higher proportions of imputed births. Luther and Cho limited the application of their method to women age 15–68.

Tables 1 and 2 and figures 2 and 3 illustrate the application of Luther and Cho’s method to a mother age 48 in the 1900 census with eight CEB, seven CS to the time of the census, and six children coresident in the household ages 25, 17, 15, 13, 11, and 5. From these inputs we can calculate that one of the mother’s eight CEB is deceased and one is living elsewhere (unmatched). We can also calculate the corresponding birth year and mother’s age at birth for the six coresident children. In this example, shown in detail in Table 1, the mother gave birth to her 25-year old coresident child sometime between June 1, 1874 and May 31, 1875 (nominal year 1874) while between the ages of 22.0 and 23.997 (average age 23.0). She gave birth to her five other coresident children in nominal years 1882, 1884, 1886, 1888, and 1894 while about age 31.0, 33.0, 35.0, 37.0, and 43.0, respectfully. The age of the deceased child and non coresident child are unknown. To construct the mother’s complete birth history, we need to impute a census age for each of these two children.

Table 1.

Example of a partial birth history for a woman age 48 at the 1900 census

| Child’s age at last birthday | Child’s birth date range | Child’s nominal year of birth | Mother’s age at birth | Mother’s average age at birth | Child’s status at 1900 census |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||||

| 25 | June 1, 1874 – May 31, 1875 | 1874 | 22.0 – 23.997 | 23.0 | Living, coresident |

| 17 | June 1, 1882 – May 31, 1883 | 1882 | 30.0 – 31.997 | 31.0 | Living, coresident |

| 15 | June 1, 1884 – May 31, 1885 | 1884 | 32.0 – 33.997 | 33.0 | Living, coresident |

| 13 | June 1, 1886 – May 31, 1887 | 1886 | 34.0 – 35.997 | 35.0 | Living, coresident |

| 11 | June 1, 1888 – May 31, 1889 | 1888 | 36.0 – 37.997 | 37.0 | Living, coresident |

| 5 | June 1, 1894 – May 31, 1895 | 1894 | 42.0 – 43.997 | 43.0 | Living, coresident |

| Unknown | Unknown | Unknown | Unknown | Unknown | Deceased |

| Unknown | Unknown | Unknown | Unknown | Unknown | Living, non co-resdent |

Notes: Example woman has 8 children ever born, 7 children surviving, and 6 children coresident children ages 25, 17, 15, 13, 11 and 5. From these data we can determine that two children -- one deceased and one unmatched (living, but non coresident) -- are missing from the woman’s birth history. Each missing child, shown in bold, has an unknown age at the 1900 census and an associated birth year and mother’s age at birth. The 1900 census was enumerated on June 1, 1900.

Table 2.

Imputed complete birth history for example woman shown in table 1

| Child’s age at last birthday | Child’s birth date range | Child’s nominal year of birth | Mother’s age at birth | Mother’s average age at birth | Child’s status at 1900 census |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||||

| 27 | June 1, 1872 – May 31, 1873 | 1872 | 20.0 – 21.997 | 21.0 | Living, non coresdent |

| 25 | June 1, 1874 – May 31, 1875 | 1874 | 22.0 – 23.997 | 23.0 | Living, coresident |

| 21 | June 1, 1878 – May 31, 1879 | 1878 | 26.0 – 27.997 | 27.0 | Deceased |

| 17 | June 1, 1882 – May 31, 1883 | 1882 | 30.0 – 31.997 | 31.0 | Living, coresident |

| 15 | June 1, 1884 – May 31, 1885 | 1884 | 32.0 – 33.997 | 33.0 | Living, coresident |

| 13 | June 1, 1886 – May 31, 1887 | 1886 | 34.0 – 35.997 | 35.0 | Living, coresident |

| 11 | June 1, 1888 – May 31, 1889 | 1888 | 36.0 – 37.997 | 37.0 | Living, coresident |

| 5 | June 1, 1894 – May 31, 1895 | 1894 | 42.0 – 43.997 | 43.0 | Living, coresident |

Notes: Ages in bold and associated birth year and mother’s age at birth were imputed using the procedure described in text and by Luther and Cho (1978). Children were then sorted by nominal year of birth.

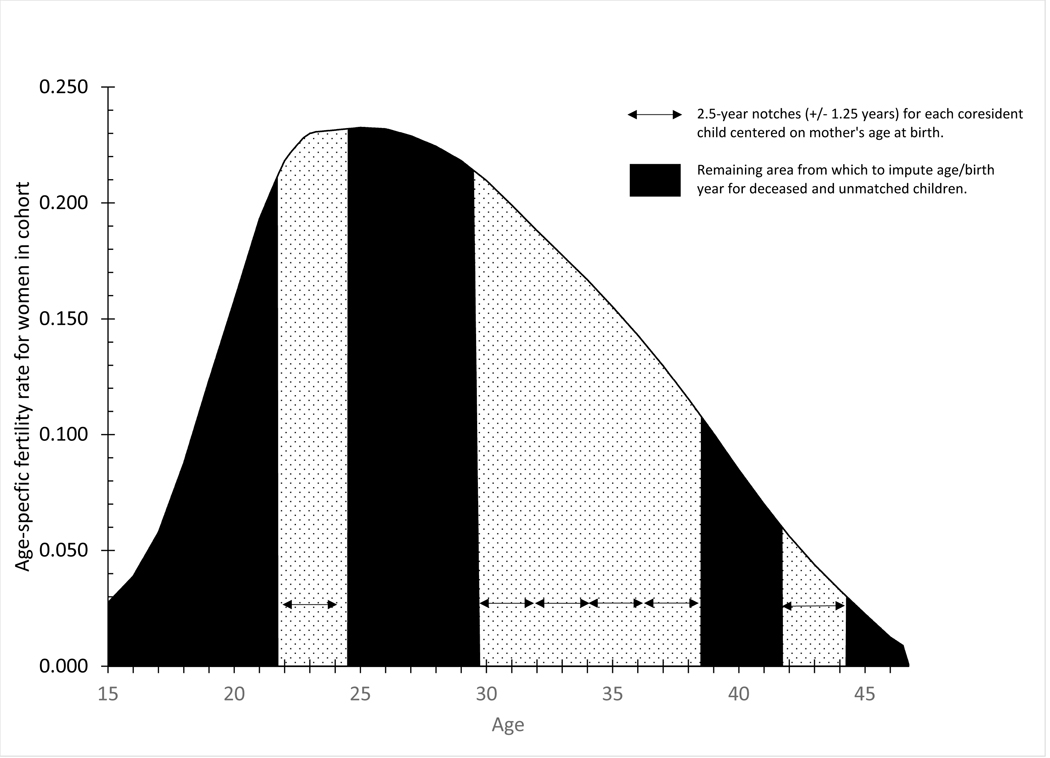

Figure 2.

Assumed age-specific fertility schedule for example mother age 48 in the 1900 census with notches for coresident children ages 25, 17, 15, 13, 11 and 5

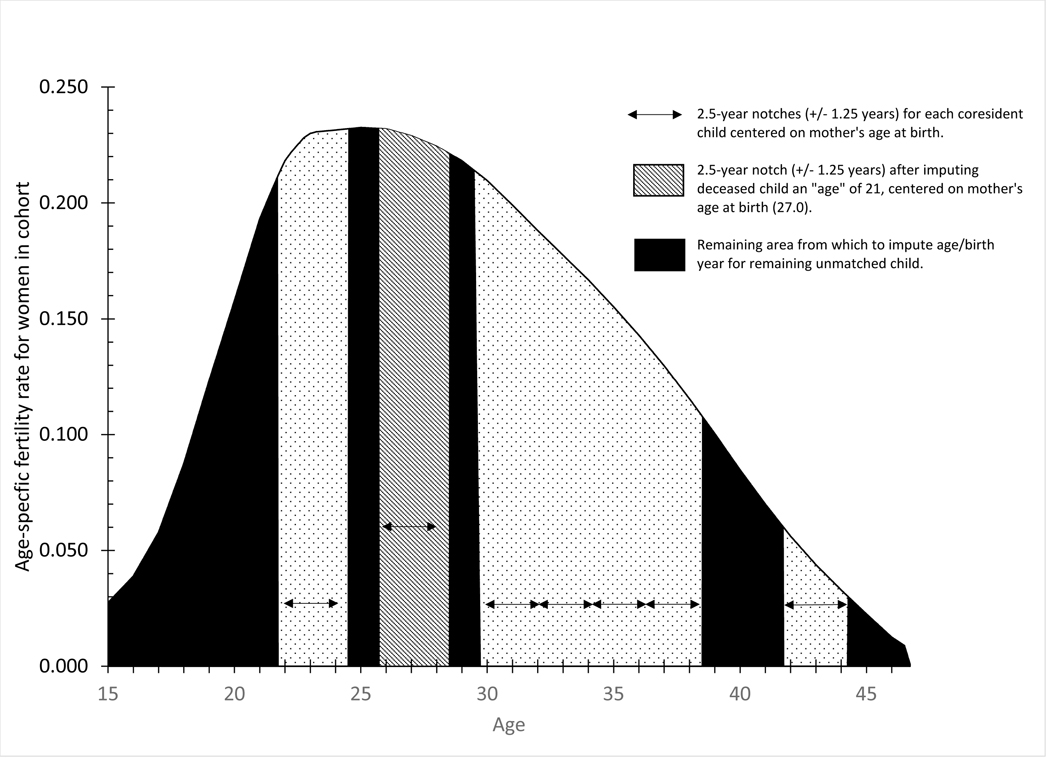

Figure 3.

Assumed age-specific fertility schedule for example mother age 48 in the 1900 census with notches for coresident children and notch for first imputed child

Luther and Cho assumed that the birth of deceased and unmatched children could not be in the same year as that of a matched, coresident child. Although twins or a second birth in the same year are possible, such births are extremely unlikely relative to the chance of a birth in a year without a known birth. Luther and Cho also assumed that the probability of a birth in the year immediately prior to or after a known birth was reduced, consistent with a period of postpartum infertility and typical 9-month gestation. To model the negligible probability of a birth in the same year and the reduced probability in adjacent years, Luther and Cho “notched” the average age-specific fertility curve for women in the mother’s birth cohort plus or minus 1.25 years around the mother’s average age at birth for each matched, coresident child (see figure 2 for an illustration of the example woman in Table 1 with +/− 1.25 year notches around the birth of children at ages 23.0, 31.0, 33.0, 35.0, 37.0, and 43.0). A mother who gave birth at age 23.0, for example, was assumed to have zero probability of having given birth to another child between the ages of 21.75 and 24.25. The remaining unnotched area under fertility curve (shown in black in the figure) represents a first approximation of the probability that the mother gave birth at those ages. In our example, the unnotched space under the fertility curve between ages 24.5 and 25.5 represents 10.5% of the total unnotched space between ages 15 and 46. In practice, when imputing an age and associated mother’s age at birth for a deceased or an unmatched child, we must also account for the conditional probability that a child born j years before the census died or left home before the census. These conditional probabilities are easily calculated with cohort life tables of survivorship by single years of age for both sexes combined and the observed age-profile of unmatched children in the population. Children were more likely to have died or left home the older their age at the census because of their longer exposure to the cumulative risks, so birth probabilities for a deceased or an unmatched child are somewhat higher at women’s younger ages and somewhat lower at women’s older ages than shown in the figure.

In assigning an age to each deceased and unmatched child, Luther and Cho first randomly determined which child to assign and then imputed the age using relative birth probabilities for each mother’s age at birth. After the age of the first deceased or unmatched child was determined, the woman’s fertility schedule was again notched at the corresponding mother’s age at birth, the relative birth probabilities recalculated for each child’s age/mother’s age at birth, and the process repeated until the ages of all deceased and unmatched children were assigned. In our example, the imputation program randomly chose to impute the age of the deceased child first and then randomly assigned an “age” of 21 using the conditional birth probabilities. As shown in Figure 3, the mother’s fertility schedule was again notched +/− 1.25 years at her corresponding average age at birth (27.0). On the next pass, the program assigned an age for the unmatched child using the remaining area under the fertility curve and conditional probabilities of unmatched children by age. In our example, the randomly assigned age for the unmatched child was 27 at the time of the census, born about 27.5 years before the census when the mother was on average 21.0. Table 2 shows the reconstructed complete birth history for the example woman with the imputed age, birth year, and mother’s age at birth for her deceased and unmatched children.

In most cases, of course, the imputed ages for deceased and unmatched children are more likely to be incorrect than correct (if we knew the correct ages to make the assessment). In the example, the unknown true ages of the imputed children could have been any two of 26 possible different ages. The only ages the program could not have imputed were the ages of the existing children. Because the program assigns ages randomly—albeit based on the conditional probabilities of deceased and unmatched children at each age—the program is likely to impute different ages for deceased and unmatched children each time it runs. In the overall population, however, the imputed ages of deceased and unmatched children will correspond with the calculated birth probabilities. Age-specific fertility patterns and average birth intervals for all but the smallest population subgroups should be approximately correct. Indeed, as discussed below, the overall results match closely with OCM estimates. Results of birth spacing models and other applications of the data are also consistent with expectations and previous studies, adding confidence to the results.

I followed Luther and Cho’s method closely, but with a few minor changes.7 Table 3 summarizes the results. It shows the number of all living coresident, deceased, and unmatched (living, non coresident) children in the 1900 and 1910 IPUMS samples for mothers age 15–68 by mothers’ age at birth and cohort. In total for both census years, the imputation procedure assigned a census age for 843,662 deceased and 685,039 unmatched children. Together with the 2,093,500 births represented by women’s coresident children, these imputed births allow the construction of birth histories for 1,469,764 women age 15–68. Complete birth histories—from age 15 to 49—were constructed for 246,381 women who turned age 50 before the census.

Table 3.

Number of living, deceased and unmatched (non coresident) children by mothers’ age at birth, mothers’ birth cohort, and sample, Luther and Cho birth reconstruction method

| 1900 IPUMS Sample | 1910 IPUMS Sample | ||||||||||||||||

|

|

|

||||||||||||||||

| 1830–39 Birth Cohort (71,566 women) | 1830–39 Birth Cohort | ||||||||||||||||

|

|

|

||||||||||||||||

| Age | Living, coresident | Dead | Unmatched | Total | Age | Living, coresident | Dead | Unmatched | Total | ||||||||

| 15–19 | 1,167 | 4% | 11,551 | 42% | 14,698 | 54% | 27,416 | 100% | 15–19 | - | - | - | - | ||||

| 20–24 | 6,063 | 8% | 27,783 | 39% | 37,652 | 53% | 71,498 | 100% | 20–24 | - | - | - | - | ||||

| 25–29 | 10,204 | 14% | 26,559 | 35% | 38,797 | 51% | 75,560 | 100% | 25–29 | - | - | - | - | ||||

| 30–34 | 14,525 | 21% | 21,719 | 31% | 34,096 | 48% | 70,340 | 100% | 30–34 | - | - | - | - | ||||

| 35–39 | 18,531 | 32% | 15,768 | 27% | 24,060 | 41% | 58,359 | 100% | 35–39 | - | - | - | - | ||||

| 40–44 | 15,689 | 48% | 7,984 | 24% | 8,941 | 27% | 32,614 | 100% | 40–44 | - | - | - | - | ||||

| 45–49 | 4,414 | 72% | 1,010 | 17% | 686 | 11% | 6,110 | 100% | 45–49 | - | - | - | - | ||||

| Total | 70,593 | 21% | 112,374 | 33% | 158,930 | 46% | 341,897 | 100% | Total | - | - | - | - | ||||

| 1840–49 Birth Cohort (125,469 women) | 1840–49 Birth Cohort (17,926 women) | ||||||||||||||||

|

|

|

||||||||||||||||

| Age | Living, coresident | Dead | Unmatched | Total | Age | Living, coresident | Dead | Unmatched | Total | ||||||||

| 15–19 | 2,792 | 6% | 17,739 | 40% | 24,377 | 54% | 44,908 | 100% | 15–19 | 273 | 4% | 2,594 | 40% | 3,582 | 56% | 6,449 | 100% |

| 20–24 | 16,179 | 13% | 43,806 | 35% | 64,626 | 52% | 124,611 | 100% | 20–24 | 1,536 | 8% | 6,805 | 37% | 10,155 | 55% | 18,496 | 100% |

| 25–29 | 37,237 | 27% | 40,561 | 29% | 61,030 | 44% | 138,828 | 100% | 25–29 | 2,717 | 13% | 6,827 | 34% | 10,788 | 53% | 20,332 | 100% |

| 30–34 | 59,498 | 46% | 31,960 | 25% | 37,573 | 29% | 129,031 | 100% | 30–34 | 3,603 | 19% | 5,586 | 30% | 9,667 | 51% | 18,856 | 100% |

| 35–39 | 62,639 | 65% | 21,924 | 23% | 11,705 | 12% | 96,268 | 100% | 35–39 | 4,251 | 30% | 3,741 | 26% | 6,309 | 44% | 14,301 | 100% |

| 40–44 | 36,171 | 74% | 11,410 | 23% | 1,429 | 3% | 49,010 | 100% | 40–44 | 3,398 | 45% | 1,853 | 25% | 2,304 | 30% | 7,555 | 100% |

| 45–49 | 7,512 | 82% | 1,530 | 62% | 90 | 1% | 9,132 | 100% | 45–49 | 904 | 72% | 217 | 17% | 135 | 11% | 1,256 | 100% |

| Total | 222,028 | 38% | 168,930 | 29% | 200,830 | 34% | 591,788 | 100% | Total | 16,682 | 19% | 27,623 | 32% | 42,940 | 49% | 87,245 | 100% |

| 1850–59 Birth Cohort (183,708) | 1850–59 Birth Cohort (31,490 women) | ||||||||||||||||

|

|

|

||||||||||||||||

| Age | Living, coresident | Dead | Unmatched | Total | Age | Living, coresident | Dead | Unmatched | Total | ||||||||

| 15–19 | 10,673 | 16% | 23,812 | 36% | 31,677 | 48% | 66,162 | 100% | 15–19 | 744 | 6% | 4,104 | 35% | 6,738 | 58% | 11,586 | 100% |

| 20–24 | 71,999 | 39% | 52,282 | 29% | 58,041 | 32% | 182,322 | 100% | 20–24 | 4,039 | 13% | 10,276 | 32% | 17,562 | 55% | 31,877 | 100% |

| 25–29 | 131,246 | 66% | 42,127 | 21% | 25,618 | 13% | 198,991 | 100% | 25–29 | 8,765 | 25% | 9,307 | 27% | 16,595 | 48% | 34,667 | 100% |

| 30–34 | 135,990 | 78% | 33,575 | 19% | 5,734 | 3% | 175,299 | 100% | 30–34 | 14,170 | 46% | 6,891 | 22% | 9,860 | 32% | 30,921 | 100% |

| 35–39 | 102,501 | 78% | 26,513 | 20% | 2,025 | 2% | 131,039 | 100% | 35–39 | 14,466 | 64% | 5,047 | 22% | 2,964 | 13% | 22,477 | 100% |

| 40–44 | 40,684 | 78% | 10,982 | 21% | 429 | 1% | 52,095 | 100% | 40–44 | 7,933 | 72% | 2,604 | 24% | 412 | 4% | 10,949 | 100% |

| 45–49 | 3,217 | 80% | 793 | 20% | 15 | 0% | 4,025 | 100% | 45–49 | 1,446 | 81% | 326 | 18% | 24 | 1% | 1,796 | 100% |

| Total | 496,310 | 61% | 190,084 | 23% | 123,539 | 15% | 809,933 | 100% | Total | 51,563 | 36% | 38,555 | 27% | 54,155 | 38% | 144,273 | 100% |

| 1860–69 Birth Cohort (254,897 women) | 1860–69 Birth Cohort (46,238 women) | ||||||||||||||||

|

|

|

||||||||||||||||

| Age | Living, coresident | Dead | Unmatched | Total | Age | Living, coresident | Dead | Unmatched | Total | ||||||||

| 15–19 | 39,286 | 53% | 23,040 | 31% | 12,482 | 17% | 74,808 | 100% | 15–19 | 2,361 | 16% | 4,874 | 33% | 7,751 | 52% | 14,986 | 100% |

| 20–24 | 165,753 | 72% | 49,229 | 21% | 14,140 | 6% | 229,122 | 100% | 20–24 | 17,836 | 41% | 11,374 | 26% | 14,826 | 34% | 44,036 | 100% |

| 25–29 | 208,399 | 81% | 41,874 | 16% | 7,777 | 3% | 258,050 | 100% | 25–29 | 31,967 | 67% | 9,182 | 19% | 6,818 | 14% | 47,967 | 100% |

| 30–34 | 142,151 | 82% | 28,654 | 17% | 2,802 | 2% | 173,607 | 100% | 30–34 | 31,092 | 77% | 7,567 | 19% | 1,605 | 4% | 40,264 | 100% |

| 35–39 | 39,300 | 82% | 8,468 | 18% | 331 | 1% | 48,099 | 100% | 35–39 | 21,973 | 77% | 6,023 | 21% | 480 | 2% | 28,476 | 100% |

| 40–44 | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | 40–44 | 8,391 | 77% | 2,407 | 22% | 99 | 1% | 10,897 | 100% | |

| 45–49 | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | 45–49 | 603 | 80% | 145 | 19% | 6 | 1% | 754 | 100% | |

| Total | 594,889 | 76% | 151,265 | 19% | 37,532 | 5% | 783,686 | 100% | Total | 114,223 | 61% | 41,572 | 22% | 31,585 | 17% | 187,380 | 100% |

| 1870–79 Birth Cohort (352,143 women) | 1870–79 Birth Cohort (63,731 women) | ||||||||||||||||

|

|

|

||||||||||||||||

| Age | Living, coresident | Dead | Unmatched | Total | Age | Living, coresident | Dead | Unmatched | Total | ||||||||

| 15–19 | 62,190 | 69% | 19,872 | 22% | 8,377 | 9% | 90,439 | 100% | 15–19 | 9,846 | 55% | 4,848 | 27% | 3,120 | 18% | 17,814 | 100% |

| 20–24 | 169,820 | 80% | 33,075 | 16% | 9,711 | 5% | 212,606 | 100% | 20–24 | 39,247 | 74% | 10,319 | 19% | 3,439 | 6% | 53,005 | 100% |

| 25–29 | 72,188 | 84% | 11,828 | 14% | 1,511 | 2% | 85,527 | 100% | 25–29 | 47,136 | 81% | 9,100 | 16% | 1,977 | 3% | 58,213 | 100% |

| 30–34 | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | 30–34 | 32,199 | 82% | 6,199 | 16% | 695 | 2% | 39,093 | 100% | |

| 35–39 | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | 35–39 | 8,748 | 82% | 1,809 | 17% | 69 | 1% | 10,626 | 100% | |

| 40–44 | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | 40–44 | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | ||

| 45–49 | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | 45–46 | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | ||

| Total | 304,198 | 78% | 64,775 | 17% | 19,599 | 5% | 388,572 | 100% | Total | 137,176 | 77% | 32,275 | 18% | 9,300 | 5% | 178,751 | 100% |

| 1880–89 Birth Cohort (192,735 women) | 1880–89 Birth Cohort (84,102 women) | ||||||||||||||||

|

|

|

||||||||||||||||

| Age | Living, coresident | Dead | Unmatched | Total | Age | Living, coresident | Dead | Unmatched | Total | ||||||||

| 15–19 | 10,228 | 78% | 1,800 | 14% | 1,148 | 9% | 13,176 | 100% | 15–19 | 14,759 | 70% | 4,185 | 20% | 2,182 | 10% | 21,126 | 100% |

| 20–24 | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | 20–24 | 41,232 | 81% | 7,295 | 14% | 2,587 | 5% | 51,114 | 100% | |

| 25–29 | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | 25–29 | 17,075 | 86% | 2,505 | 13% | 375 | 2% | 19,955 | 100% | |

| 30–34 | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | 30–34 | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | ||

| 35–39 | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | 35–39 | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | ||

| 40–44 | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | 40–44 | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | ||

| 45–49 | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | 45–49 | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | ||

| Total | 10,228 | 78% | 1,800 | 14% | 1,148 | 9% | 13,176 | 100% | Total | 73,066 | 79% | 13,985 | 15% | 5,144 | 6% | 92,195 | 100% |

| 1890–99 Birth Cohort (0 women) | 1890–99 Birth Cohort 45,829 women) | ||||||||||||||||

|

|

|

||||||||||||||||

| Age | Living, coresident | Dead | Unmatched | Total | Age | Living, coresident | Dead | Unmatched | Total | ||||||||

| 15–19 | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | 15–19 | 2,544 | 77% | 424 | 13% | 337 | 10% | 3,305 | 100% | |

| 20–24 | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | 20–24 | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | ||

| 25–29 | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | 25–29 | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | ||

| 30–34 | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | 30–34 | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | ||

| 35–39 | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | 35–39 | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | ||

| 40–44 | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | 40–44 | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | ||

| 45–49 | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | 45–49 | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | ||

| Total, all birth cohorts | Total, all birth cohorts | ||||||||||||||||

|

|

|

||||||||||||||||

| Age | Living, coresident | Dead | Unmatched | Total | Age | Living, coresident | Dead | Unmatched | Total | ||||||||

| 15–49 | 1,698,246 | 58% | 689,228 | 24% | 541,578 | 18% | 2,929,052 | 100% | 15–49 | 395,254 | 57% | 154,434 | 22% | 143,461 | 21% | 693,149 | 100% |

Source: 1900 and 1910 IPUMS datasets (Ruggles et al. 2018).

Because of their children’s shorter exposure to risk, the birth histories of women in more recent birth cohorts (mothers who were younger at the time of each census) contain a higher proportion of coresident children with known ages compared to the birth histories of women in earlier birth cohorts (mothers who were older at the time of the census). In the 1910 IPUMS sample, for example, 61 percent of the children born to mothers in the 1860–69 birth cohort were enumerated as coresident with their mothers in the 1910 census and therefore can be associated closely with their mother’s age at birth via their observed age. The remaining 39 percent of the children born to these women were either deceased or non coresident, requiring their ages to be imputed. Only 36 percent of children born to mothers in the 1850–59 birth cohort and only 19 percent of the children born to women in the 1840–49 birth cohort were still coresident with their mothers in the household in the 1910 census, when their mothers were in their fifties and sixties, requiring even higher percentages of children’s ages to be imputed. Thus, women in earlier birth cohorts who were older at the time of the census have birth histories constructed from greater percentages of imputed births. The lower proportion of known births among women in earlier birth cohorts also reduces the area notched from each woman’s predicted fertility schedule and likely lowers the accuracy of the reconstructed birth histories.

Researchers should be careful not to conflate women’s age at the census with women’s age at the birth of their children. Older women in the census had proportionately fewer coresident children and proportionately more deceased and unmatched children than younger women. Older women’s birth histories therefore contain proportionately more imputed births. Within each birth cohort of women, however, children born during women’s older ages were born more recently than children born during women’s younger ages, and thus had shorter exposures to the risks of death and leaving home. Only 39 percent of children born to mothers age 20–24 in the 1850–59 birth cohort were coresident with their mother at the time of the 1900 census compared to 78 percent of the children born when these women were age 40–44. Thus, within each birth cohort of mothers, women’s birth histories contain relatively fewer imputed births at older ages than at younger ages.

Birth histories among women less than age 50 at the time of the census are right-censored and complete only to the mother’s age in the census. Although births among these women can still be used in event-history analyses—e.g., differentials in birth timing among currently-married women age 25–29—study of the distribution of births across the full childbearing age range is limited to women in the 1830–39 and 1840–49 birth cohorts in the 1900 IPUMS sample and women in the 1840–49 and 1850–59 birth cohorts in the 1910 IPUMS sample.

Because women’s birth histories in the 1840–49 birth cohort were imputed using two separate censuses (in 1900 when women in the cohort were age 50–59 and in 1910 when age 60–68), comparison of the estimates has the potential to suggest whether results are robust to selection and recall and biases over the ten-year span between the two censuses and potential errors introduced by the imputation procedure. Table 4 shows a few descriptive statistics for three groups of women in the 1840–49 birth cohort: (1) all women in the cohort surviving to the 1900 or 1910 censuses; (2) all ever-married women in the cohort at the time of the census; and (3) all currently-married women with spouses present in the cohort at the time of the census. The groups are not distinct: ever-married women are included with single women in the all women category, while currently-married women with spouses present are included with widowed, divorced and separated women in the ever-married category. To construct descriptive statistics for all women, I added single women in the 1900 and 1910 IPUMS samples back to the dataset of women with reconstructed birth histories and assumed they had no children. As discussed above, some single women likely had illegitimate children that were not reported in the census, imparting a downward bias to age-specific fertility rates, especially among women age 15–19 and age 20–24 at the time of the 1900 and 1910 censuses. Women age 15–24 in the 1840–49 birth cohort shown in table 4, however, were over age 50 at the time of the 1900 census. Many of the women in the cohort who had illegitimate children in their teens or early twenties subsequently married, and should have reported their illegitimate children as part of their CEB total in the 1900 census. As shown in table 4, single women represented only 7.3 percent of all women in the cohort surviving to the 1900 census and only 6.5 percent of women surviving to the 1910 census. Illegitimate births among these women are therefore very unlikely to bias the overall results significantly.

Although the second and third groups shown in table 4 are limited to women who married prior to the census—and who therefore should have answered the CEB and CS questions in the census—the descriptive statistics summarize their fertility over their full prior life course, including the years they spent single, widowed or divorced, not just the years they spent married. In other words, the age-specific rates shown are general fertility rates, not marital fertility rates. Because 93 percent of women in the 1840–49 birth cohort eventually married, and many of the currently widowed or divorced spent most of their childbearing years married, results do not vary dramatically between the three groups. Unsurprisingly, however, women currently married at the time of the census experienced the highest fertility rates, especially at older ages when they would have experienced less marital disruption than ever-married women, who included significant proportions of women who were currently widowed, divorced or separated.

The 125,469 women born 1840–49 in the 1900 IPUMS sample reported more than 594 thousand births. Among these births, 63 percent were imputed using the procedures described in the text. The 1910 IPUMS sample is a smaller density sample. The 17,926 women who were born in the 1840–49 cohort, survived to the 1910 census, and were included in the 1910 IPUMS sample reported close to 88 thousand births. Among these births, 81 percent were imputed. Despite being based on different women, measured by different censuses taken ten years apart, a different number of cases, and with a substantial difference in the percentages of imputed births, the two sets of estimates are very close. The average number of children ever born and average age at last birth was slightly higher when measured in 1910 than when measured in 1900, consistent with more robust health among women in the cohort surviving to 1910, but the differences were modest. There was proportionately fewer childless couples when measured in 1910 compared to the proportion when measured ten years earlier, suggesting lower survival among childless women. Among currently-married women, CEB, age-specific fertility rates, and parity progression ratios were nearly identical in both census samples. Birth intervals were modestly longer—about one or two months on average—among women in the 1910 sample. This difference can be explained by the earlier mean age at first birth and later mean age at last birth of women who survived the additional ten years to the 1910 census.

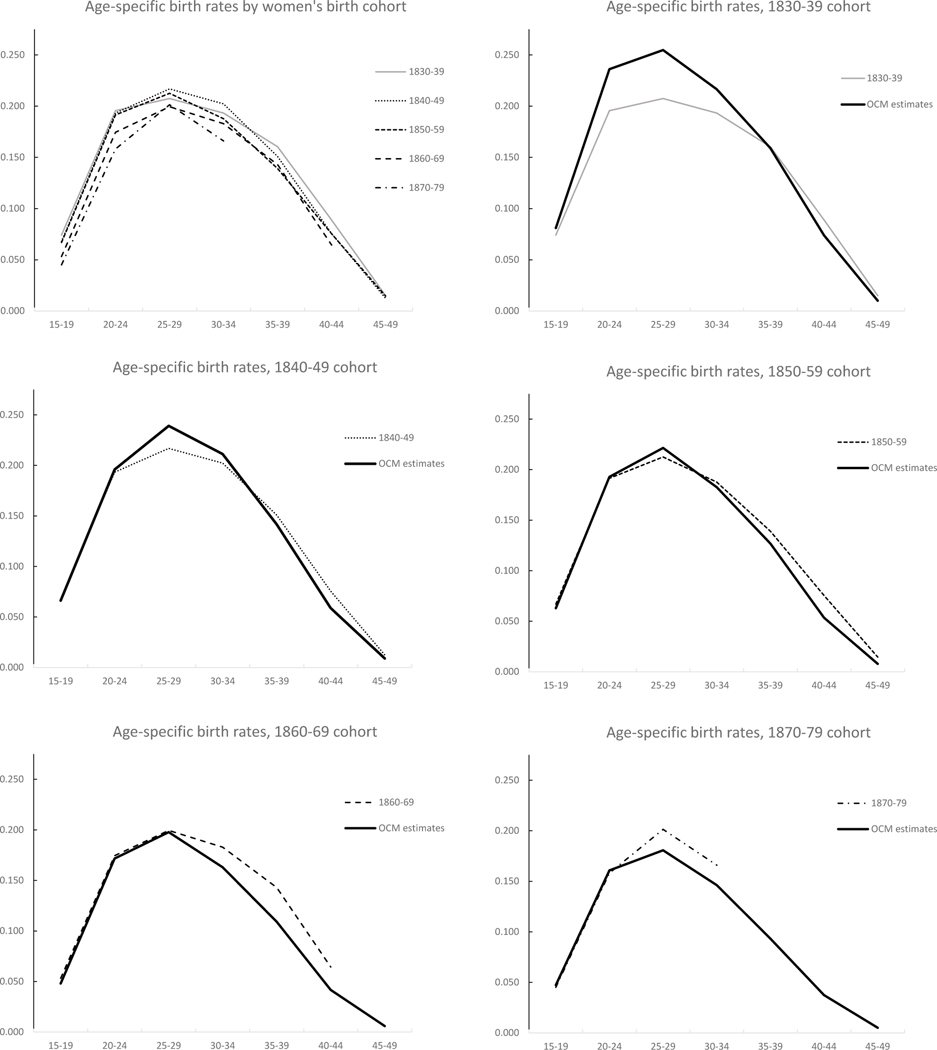

Figure 4 compares age-specific fertility rates for white women in the 1900 and 1910 IPUMS samples estimated from their reconstructed birth histories, with OCM estimates for white women in the 1850–1880 and 1900–1940 IPUMS samples (Hacker 2016). For these comparisons, I included single white women in the 1900 and 1910 IPUMS samples with the ever-married women with reconstructed birth histories, and again assumed these single women had no children. The top left panel compares results from the reconstructed birth histories by women’s birth cohort. The figure shows similar rates of childbearing by age among white women in the first three cohorts, although there was a modest decline in rates after age 35 with each subsequent cohort between 1830–39 and 1850–59. Fertility rates were modestly lower for all observed age groups among white women in the 1860–69 cohort, indicating an accelerating fertility decline among women of all ages. Among white women in the 1870–79 birth cohort, fertility rates were lower still, and appear to have been declining faster at older ages, although older age groups among women in this cohort were not observed before the 1910 census.

Figure 4.

Age-specific birth rates for white women with reconstructed birth histories, 1900 and 1910 IPUMS samples.

The other panels in figure 4 compare rates from the reconstituted birth histories with OCM estimates in different birth cohorts. In general, there is close agreement between the estimated rates for most cohorts. The greatest differences between the two sets of estimates was observed for white women in the earliest birth cohort (1830–39), with rates from the reconstructed birth histories being markedly lower during peak child bearing ages. The difference is consistent with underreporting of CEB among older women in the 1910 IPUMS sample, but may also reflect survivorship biases and errors in the assumptions used to generate the OCM estimates, including child mortality rates and census coverage errors.

At first glance, the close agreement between fertility rates estimated from reconstructed birth histories and OCM is surprising given the many possible sources of disagreement. As mentioned earlier, less than half of the young women enumerated by the 1850 and 1860 censuses survived to be enumerated by the 1900 and 1910 censuses. These women contributed births and risk-years to the OCM estimates, but were not among the women with reconstructed birth histories in the 1900 and 1910 IPUMS samples. If survivorship was correlated with fertility, we can expect rates based on the two methods to disagree. Second, OCM estimates do not include many immigrant women arriving in the United States shortly before the 1900 and 1910 censuses, whose childbearing may have differed from the white women included in the OCM analysis of the 1850–1880 censuses. Third, theOCM estimates derived from multiple censuses, estimates of mortality by age and year, estimates of children living apart from their mothers by age and year, and estimates of census undercounts by age and census, any of which could be faulty. Because the 1890 census was destroyed by fire, OCM estimates included estimates for some age groups interpolated from adjacent censuses. Finally, as mentioned earlier, reconstructed birth histories may suffer from recall and other types of biases.

Despite those many sources of disagreement, however, a relatively close agreement between the age patterns of childbearing estimated from reconstructed birth histories and OCM should be expected for one major reason: Luther and Cho’s birth imputation procedure relies on OCM rates as one of the principle inputs to determine birth probabilities by mother’s age. Those rates should act as a powerful force toward convergence, especially in younger ages and in early birth cohorts with higher proportions of imputed births.

Enhancements to the Luther and Cho Method: An iterative Poisson regression approach

Given the importance of OCM estimates to the imputation procedures, errors in those estimates will be reflected in the reconstructed birth histories. Even if we assume OCM estimates are accurate for the period estimated, and further assume they are representative of the childbearing experience of an average woman surviving to be enumerated by the 1900 and 1910 censuses, they are unlikely to be representative for all population subgroups, especially groups such as non-white women, who were not included in the OCM estimates. Contemporary observers and subsequent researchers have agreed that different groups of women — native-born white women of native parentage, “Yankee” women from New England, foreign-born women from southern Europe, Jewish women, black women, etc. — experienced diverging patterns of childbearing over the course of the fertility transition (e.g., Tolnay 1981; Haines 1989; King and Ruggles 1990; Morgan, Watkins and Ewbank 1994; MacNamara 2018). Although the age pattern of coresident children among different groups of women may have reflected these divergent patterns, imputed births will bias the results toward the OCM average rates for women in the cohort, obscuring group differences.

To minimize this source of bias, I used the birth histories constructed with Luther and Cho’s birth reconstruction method to construct a Poisson model of the number of children born to women in each age group, controlling for variables available in the census data. These variables included women’s birth cohort, nativity (state or country of birth), generation (native born with native-born parents, native born with one or more foreign-born parents, or foreign born), literacy (ability to read and write), paid labor force participation (coded from occupation), race, region of residence, and size of place. Unfortunately, the 1900 and 1910 censuses measured these variables, some of which are time dependent, only at the time of the census. For women with spouses present, I also included spouse’s occupation group (using the 1950 census occupational coding and major groups as noted by the IPUMS project), nativity and generation, literacy, race, and age differential from spouse. The dependent variable included the births of children imputed with the Luther and Cho method described above. It also included, however, a sizeable proportion of living coresident children (57.7 % of births overall), whose ages were observed in the census. After estimating the model coefficients, I discarded women’s imputed children, retained women’s coresident children, and repeated Luther and Cho’s birth reconstruction process using the model coefficients to predict each woman’s fertility by age in place of the cohort OCM estimates. I reiterated this process several times. Although model coefficients converged quickly after the first iteration of the model, I made four passes through the data (three model iterations), once with OCM estimates from Hacker (2003) and three times with the model coefficients. The multiple iterations maximized the influence of living, coresident children and ensured coefficients converged on a best estimate. Coefficients for the models constructed after the fourth pass through the data were saved for possible future use with the complete-count datasets.

I explored a number of different model specifications, including models for women in all age groups with interactions between age group and various independent variables (e.g., age and cohort, age and spouse’s occupation group, etc.) and interactions between other variables, but opted for separate models for each five-year age group with no other interactions, drawing from all ever-married women age 15–68 in the combined 1900 and 1910 IPUMS samples at risk of having births in the age group. In cases where women were right-censored by the census or were observed for only part of the estimated five-year age group, I adjusted the observed CEB upward to the equivalent of a five-year observation period. Each model was then weighted by women’s years of observation in the age group. I constructed separate models for currently-married women with spouses present and ever-married women without a spouse present (widowed, divorced and separated women). Models for currently-married women with spouses present included spouse’s occupation group, place of birth, and literacy. Models for ever-married women without a spouse present were more limited. I relied on 37 different nativity and generation groups (native-born of native parentage, born in Canada, England, Scotland, Wales, Ireland, France, Netherlands, Germany, Switzerland, Austria, Hungary, Norway, Sweden, Denmark, Russia, Mexico, other Europe, and other non-European foreign birthplaces, and second generation couples with parents born in Canada, England, Scotland, Wales, Ireland, France, Netherlands, Germany, Switzerland, Austria, Hungary, Norway, Sweden, Denmark, Russia, Mexico, other Europe, and other non-European foreign birthplaces). Because foreign-born women’s birthplaces were so closely correlated with their spouses’ birthplaces, I opted for a couple-level nativity measure in models with spouses present. The nativities of the parents of the childbearing woman and her spouse were classified according to the grandmother’s nativity, except in cases in cases where the grandmother was native born and the grandfather was foreign born, in which case the nativity of the grandfather was used. Couples’ nativities were classified according to the childbearing woman’s nativity, except in cases in cases where the childbearing woman was native born and her spouse was foreign born, in which case the spouse’s nativity was used. Unfortunately, little is known about group differences in the age pattern of mortality in the United States, so I assumed all groups experienced the age pattern in national life tables.

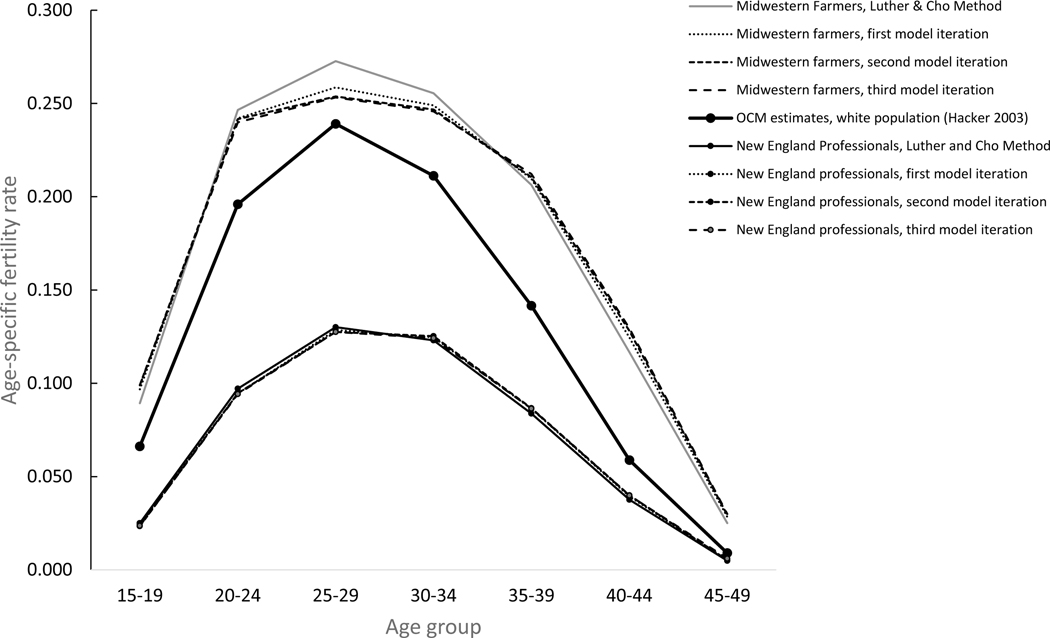

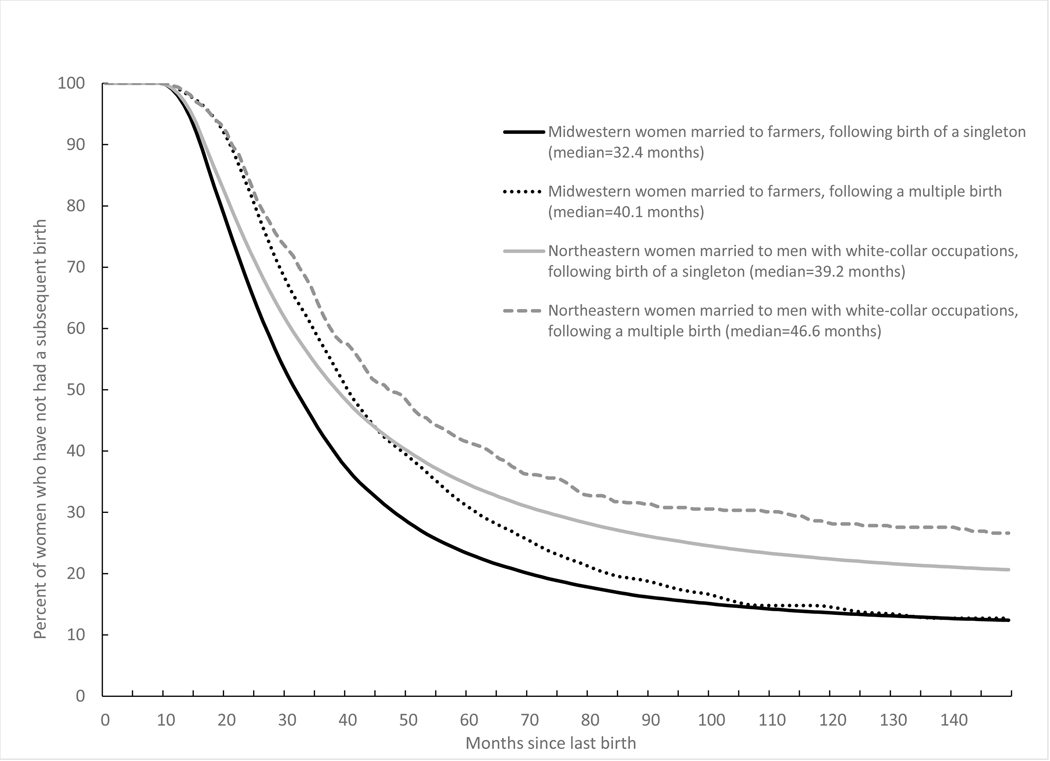

The models appear to yield good estimates. Although the models include too many variables to summarize in a table (68 coefficients in 7 age models across 4 different iterations), figure 5 illustrates the model results for two distinct groups of women in the 1840–49 cohort: literate, native-born white women of native parentage living in a large urban city in New England, currently married to a native-born white man with a professional occupation; and illiterate, native-born white women of native parentage living in the rural Midwest, currently married to a native-born white farmer of native parentage. The figure indicates a modest but significant departure from the age-specific fertility rates predicted by the basic Luther and Cho method for both groups of women with the first model iteration, and increasingly modest departures with each subsequent iteration. In general, the Poisson models indicated a slightly wider childbearing pattern than the initial results using the OCM estimates, with modestly higher age-specific fertility rates at younger and older ages and modestly lower age-specific fertility rates during women’s peak childbearing years. Among the farm women shown in figure 5, for example, the birth histories first reconstructed using Luther and Cho’s method indicated that 11.7 percent of Midwestern farm women’s childbearing took place after age 40. After the first iteration of the model, 12.6 percent of Midwestern farm women’s childbearing in the reconstructed birth histories took place after age 40. After model iteration 2, the percentage had increased to 13.0 percent, where it remained after model iteration 3. The percent of childbearing in farming women’s teens likewise increased from 7.4 percent in the initial run to 8.2 percent after the third model iteration, while the combined percentage of childbearing in the age groups 25–29 and 30–34 fell from 43.6 percent to 41.3 percent. Among women married to professional men in New England, however, the Poisson predicted modestly lower age-specific fertility rates in their teens after the third iteration (4.7 percent) relative to the first estimate based on OCM rates (5.0 percent).

Figure 5.

Age-specific birth rates, white women born 1840–49 currently married to spouses in selected occupations and regions

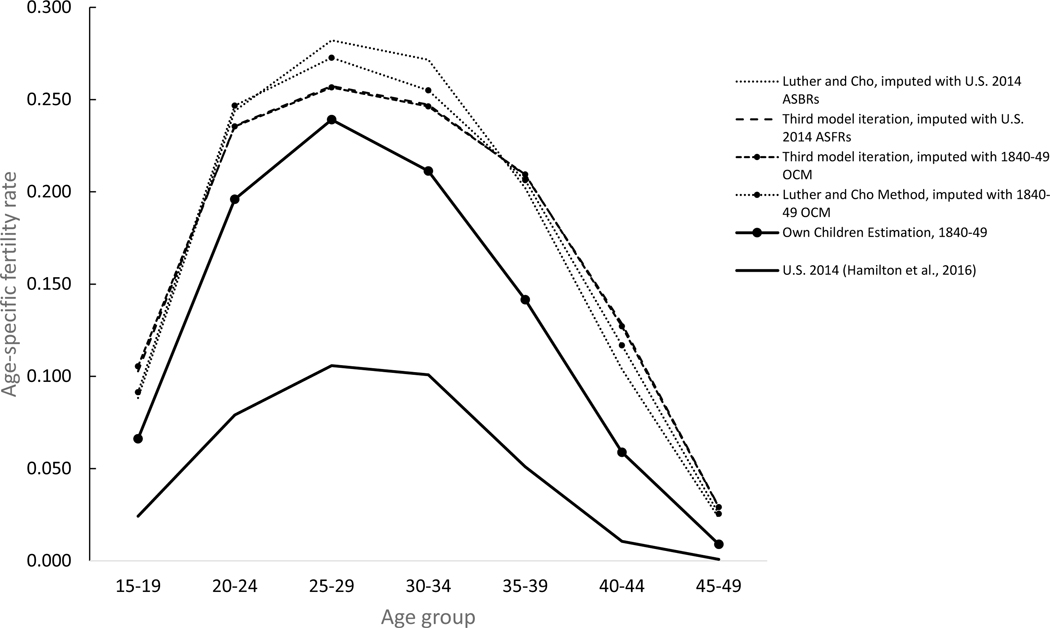

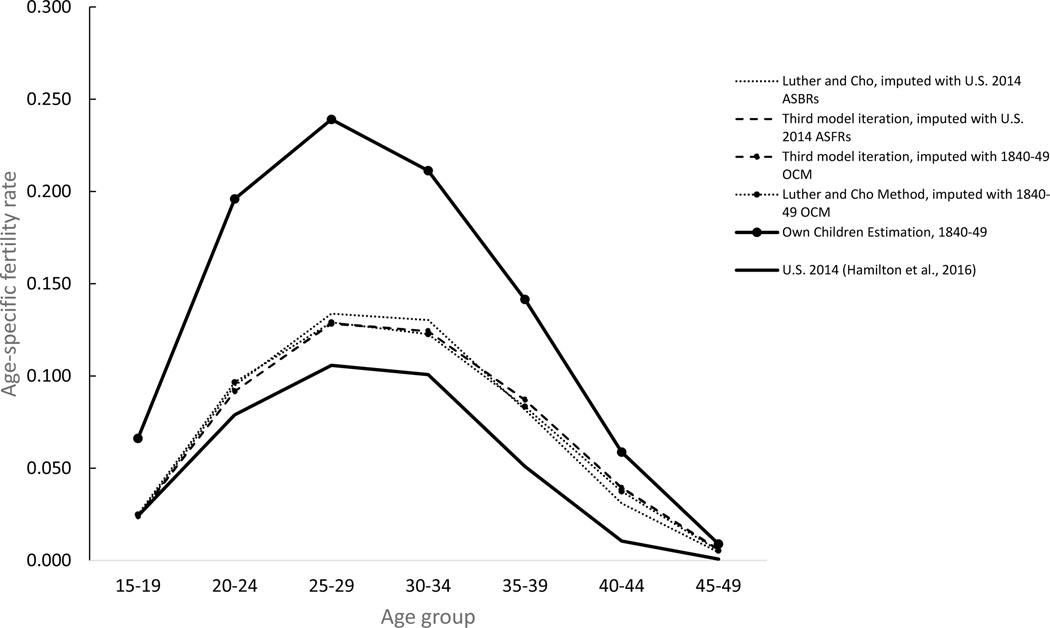

As a final check of the iterative Poisson regression approach’s ability to fine-tune predicted age-specific fertility rates, I repeated Luther and Cho’s birth imputation procedure using the age-specific fertility rates for women in the United States in 2014 as in the initial baseline for the imputation model and repeated all three model iterations. Figures 6 and 7 illustrates the results for the Midwestern women married to farmers and New England women married to professionals shown in figure 5. As expected, reliance on the 2014 population – which was characterized by higher proportions of childbearing between the ages of 25 and 35 and lower proportions of childbearing after age 35 than the 1840–49 OCM estimates originally used if figure 5 – had a significant impact on the timing of births imputed with the Luther and Cho method. Birth histories of women imputed with the 2014 age-specific fertility rates showed higher birth rates at age groups 25–29 and 30–34 and lower at age groups 35–39, 40–44 and 45–49. After the third model iteration, however, the estimated rates were virtually identical to those estimated after the third model iteration with the 1840–49 OCM estimates as the initial input for both groups of women. The estimated rates were within one percentage point of the rate predicted by with the 1840–49 OCM rates for both groups at in all age groups except for farm women in the age group 15–19, where the difference was just 2.5 percentage points. The practical conclusion is that the iterative regression approach employed here eliminates the need to have accurate age-specific fertility rates for women in each cohort and is able to fine-tune predicted fertility rates for different groups of women, including non-white women and women of different nativities and ethnicities.

Figure 6.

Age-specific birth rates, native-born white women born 1840–49 living in the Midwest region and currently married to farmers, by baseline imputation model and iteration number

Figure 7.

Age-specific birth rates, native-born white women born 1840–49 living in New Engand and currently married to men with professional occupation, by baseline imputation model and iteration number

Example Applications

There are many possible analytical uses for birth histories, including age- and marital duration-specific parity progression ratios, survival analysis of birth intervals, and Cox regression models of birth timing. As a conclusion to this article, two simple examples are shown.

The first example, shown in Table 5, compares the results of two Poisson models of recent fertility among currently-married women age 20–49 in the 1900 IPUMS sample by spouses’ occupation group. The first model relies on the number of currently-living children coresident with their mothers as the dependent variable. This variable is provided in the IPUMS dataset (nchlt5) and is frequently used in census-based analyses of women’s “net” reproduction (e.g., Dribe, Hacker and Scalone 2014; Hacker 2016). Among women included in the models, the average number of coresident own children less than five years of age was 0.790. In addition to reflecting differences in fertility, models relying on the number of living children as the dependent variable will also reflect differentials in infant and child mortality. The second model relies on the number of children born in the last five years as determined from the reconstructed birth histories. It is therefore a fertility measure, independent of infant and child mortality differentials. In addition to the number of living coresident children under age 5, this variable includes deceased and unmatched children imputed by the reconstruction process. The average number of children born in the last five years was 0.947, indicating that women in the models on average experienced the death or departure from the household of 0.157 children (16.6 percent of those born) during the five years preceding the census. Women currently married to farmers are the reference group for both models.

Table 5.