Summary

Exposure to hepatitis viruses is a recognized occupational risk for health care personnel (HCP). This report establishes new CDC guidance that includes recommendations for a testing algorithm and clinical management for HCP with potential occupational exposure to hepatitis C virus (HCV). Baseline testing of the source patient and HCP should be performed as soon as possible (preferably within 48 hours) after the exposure. A source patient refers to any person receiving health care services whose blood or other potentially infectious material is the source of the HCP’s exposure. Two options are recommended for testing the source patient. The first option is to test the source patient with a nucleic acid test (NAT) for HCV RNA. This option is preferred, particularly if the source patient is known or suspected to have recent behaviors that increase risk for HCV acquisition (e.g., injection drug use within the previous 4 months) or if risk cannot be reliably assessed. The second option is to test the source patient for antibodies to hepatitis C virus (anti-HCV), then if positive, test for HCV RNA. For HCP, baseline testing for anti-HCV with reflex to a NAT for HCV RNA if positive should be conducted as soon as possible (preferably within 48 hours) after the exposure and may be simultaneous with source-patient testing. If follow-up testing is recommended based on the source patient’s status (e.g., HCV RNA positive or anti-HCV positive with unavailable HCV RNA or if the HCV infection status is unknown), HCP should be tested with a NAT for HCV RNA at 3–6 weeks postexposure. If HCV RNA is negative at 3–6 weeks postexposure, a final test for anti-HCV at 4–6 months postexposure is recommended. A source patient or HCP found to be positive for HCV RNA should be referred to care. Postexposure prophylaxis of hepatitis C is not recommended for HCP who have occupational exposure to blood and other body fluids. This guidance was developed based on expert opinion (CDC. Updated U.S. Public Health Service guidelines for the management of occupational exposures to HBV, HCV, and HIV and recommendations for postexposure prophylaxis. MMWR Recommend Rep 2001;50[No. RR-11]; Supplementary Figure, https://stacks.cdc.gov/view/cdc/90288) and reflects updated guidance from professional organizations that recommend treatment for acute HCV infection. Health care providers can use this guidance to update their procedures for postexposure testing and clinical management of HCP potentially exposed to hepatitis C virus.

Introduction

Exposure to hepatitis viruses has long been recognized as an occupational risk for health care personnel (HCP), and recommendations previously were established for managing occupational exposures to bloodborne pathogens, including hepatitis C virus (HCV) (1) (Supplementary Figure, https://stacks.cdc.gov/view/cdc/90288). HCP might be exposed to blood or other body fluids, by injury from a used needle or from a splash of blood or body fluids into the eye or mouth, while caring for a patient. A source patient refers to any person receiving health care services whose blood or other potentially infectious material is the source of the HCP’s exposure. Although sharps injury prevention measures have led to overall exposure decreases in recent decades, blood and body fluid exposures, including sharps injuries, continue to occur (2). During 2018, a total of 34 U.S. hospitals reported through the Exposure Prevention Information Network (EPINet) a rate of 12.6 HCP blood and body fluid exposures per 100 average daily census days among the reporting hospitals (3). Similar exposures occur in other health care settings (e.g., nursing homes, clinics, and emergency departments) and during provision of in-home health care services.

Background

For approximately 885 HCP with percutaneous exposure to anti-HCV–positive blood (72.7% of exposures) or body fluids (27.3% of exposures) during 2002–2015 in the United States, the estimated risk for HCV infection was reported as approximately 0.2% (two of 885; 95% confidence interval [CI]: 0%–0.52%) (4). HCV RNA status of the anti-HCV positive source patients was not described. Among 458 HCP with mucocutaneous exposure, the risk for HCV infection was 0% (95% CI: 0%–0.6%) (4). Recently published studies have reported similar infection risks with percutaneous exposure (4–7), although risks ranging from 0% to 10% have been reported from studies published earlier (1,4,6); variability might be explained in part by mechanism of injury, sensitivity of the test used to detect infection, and HCV RNA status of anti-HCV–positive source patients.

Transmission risk might be higher for HCP with exposure to hollow-bore needles (4,8). Challenge studies in chimpanzee animal models have demonstrated that an infectious titer (i.e., chimpanzee infectious dose) was required to transmit infection and that the needed inoculum was different in another animal model (i.e., human liver–chimeric mouse) (9). Data from one European case-control study of HCP who experienced seroconversion after exposure to an anti-HCV–positive source patient during 1991–2002 demonstrated that, among the limited number for whom source-patient HCV RNA status was known (n = 37; 62% of HCP who seroconverted), all source patients had been HCV RNA positive (8).

This report establishes new CDC guidance that includes recommendations for a testing algorithm and clinical management for HCP with potential occupational exposure to HCV, supplanting published recommendations (1) (Supplementary Figure, https://stacks.cdc.gov/view/cdc/90288). The new CDC guidance was developed on the basis of expert opinion and reflects current understanding of the viral dynamics of early HCV infection and recent guidance from the American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases (AASLD) and the Infectious Diseases Society of America (IDSA) that recommends treatment of acute HCV infection (https://www.hcvguidelines.org/unique-populations/acute-infection) (10). Testing guidance for source patients is described in consideration of the increasing incidence of acute HCV infection (11). Health care providers can use this guidance to update their procedures for postexposure testing and clinical management of HCP potentially exposed to hepatitis C virus.

Methods

CDC developed this guidance with individual input and review by coauthors from federal agencies and academic and private health care institutions with subject matter expertise in occupational health and viral hepatitis epidemiology. The literature search described in the recent review of HCV incidence after HCP exposure through 2016 (4) was updated through October 2019, resulting in the inclusion of one additional reference (5). This guidance was presented to the Healthcare Infection Control Practices Advisory Committee for review and input at a public meeting in Atlanta, Georgia, on November 14, 2019. Subsequently, CDC made minor revisions to the figures for clarification to address the committee’s input.

Rationale and Evidence

Updated Guidance from Clinical Organizations

Recent guidance from AASLD and IDSA recommends a test-and-treat strategy for persons with acute HCV infection on initial diagnosis without awaiting spontaneous resolution (10). Although spontaneous clearance occurs in approximately 25% to 45% of acute infections (1,12,13), delays introduced by waiting for clearance might be associated with substantial anxiety on the part of the exposed HCP, might result in lost work time and risk for transmission depending on the HCP’s HCV RNA level (14), and might increase the possibility of loss to follow-up. Furthermore, emerging data about treatment of acute HCV infection with shortened courses of all-oral, direct-acting antiviral (DAA) regimens demonstrate potential benefit for treatment during the acute phase (10,15–18).

Follow-Up Testing of HCV-Exposed HCP

For exposed HCP for whom follow-up testing is indicated, CDC continues to recommend early testing for HCV RNA at 3–6 weeks after exposure. HCV RNA becomes detectable on average within 1 week after exposure; most infected persons will have detectable HCV RNA within 1–2 weeks of exposure when tested with HCV RNA detection tests approved by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (19,20). However, CDC now recommends additional follow-up testing at 4–6 months for anti-HCV with reflex or follow-up HCV RNA if anti-HCV positive because of the possibility of intermittent periods of aviremia during acute HCV infection. This phenomenon has been reported previously among exposed persons, including those who progressed to chronic infection, primarily when using older HCV RNA tests (7,21–35). Anti-HCV seroconversion occurs, on average, 8–11 weeks after exposure (1,20), although cases of delayed seroconversion have been documented among persons with immunosuppression (e.g., immunosuppression from human immunodeficiency virus [HIV] infection) (36,37). Frequency of testing during the follow-up period depends on the management objectives and plan for timing of therapy if seroconversion occurs.

Increasing Incidence of Acute HCV Infection

In the United States, incidence of acute HCV infection is increasing, primarily related to injection drug use, with a 3.7-fold increase in cases reported to CDC during 2010–2017 (11). During 2014–2017, window-period infections (HCV RNA positive and anti-HCV negative) were identified among 5.3% of HCV RNA–positive deceased organ donors who had risk factors (38). These window-period data among a discrete population with recent behavioral risk for acquiring HCV indicate the possibility that, in certain health care settings, HCP might be exposed to source patients with early HCV infection before those patients develop serologic evidence of infection or symptoms indicative of viral hepatitis.

Postexposure Prophylaxis

Postexposure prophylaxis (PEP) of hepatitis C is not recommended for HCP who have occupational exposure to blood and other body fluids (1,10,39–41) (Supplementary Figure, https://stacks.cdc.gov/view/cdc/90288). A 2017 publication estimated that 0.2% of percutaneous exposures result in HCV transmission (4). In contrast, older literature reported that approximately 1.8% of exposures resulted in transmission, meaning that routine PEP use for all occupational exposures would treat approximately 100 HCV-exposed persons for every two persons who might become infected (40). However, with the substantially lower 2017 transmission estimate of 0.2% for percutaneous exposures and 0% for mucocutaneous exposures (4), routine PEP would need to be administered to approximately 1,000 persons with percutaneous exposures for every two persons who might become infected, with no benefit to those with mucocutaneous exposures. Treatment efficacy and duration that would be required for HCV PEP has not been established (40,41). In 2019, a pilot trial of a 2-week DAA PEP regimen was initiated for HCP who were exposed from hollow-bore needlestick injury to an HCV RNA–positive source patient (42). Although the sample size will likely be insufficient for statistical power to determine whether PEP prevents seroconversion, this is the first DAA PEP study of HCV-exposed HCP. In contrast with other bloodborne pathogens for which PEP is recommended, curative DAA therapy is reserved for treatment if HCV transmission does occur (10,15–17,40,41).

CDC Guidance and Recommendations

Test the Source Patient

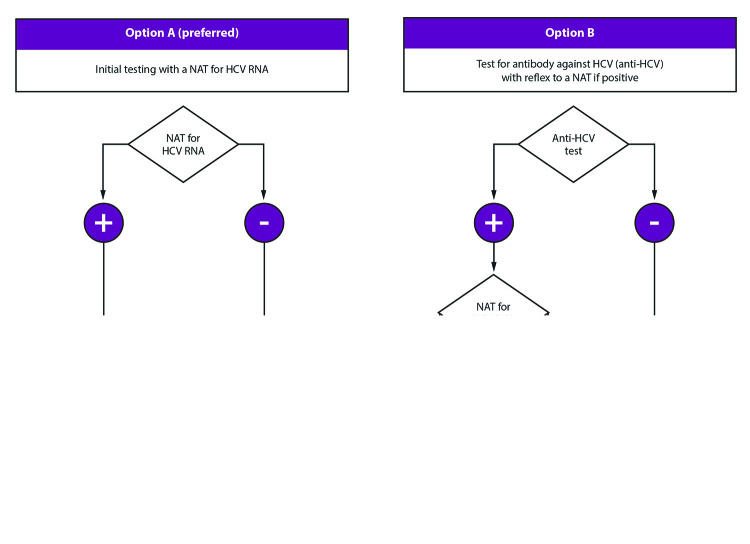

Baseline testing of the source patient should be performed as soon as possible (preferably within 48 hours) after the exposure (1,39,40) (Figure 1) (Box). This guidance provides two options for initial source patient testing: 1) option A (preferred), to test for HCV RNA, or 2) option B, to test for anti-HCV and then if positive, test for HCV RNA (Figure 1). All source patients who are anti-HCV positive should be tested by a nucleic acid test (NAT) for HCV RNA (43), preferably with a reflex test by using the same specimen if cross-contamination is not a concern or by using a fresh aliquot of the same sample if stored correctly. If HCV RNA tests are positive but the RNA level is less than the lower limit of quantitation of the assay, the results are reported as <XX IU/mL (e.g., <15 IU/mL if the lower limit of quantitation of the assay is 15 IU/mL). This means that HCV RNA was detected in the sample but is not quantifiable and that the person from whom the sample was collected should be considered to have current HCV infection (20).

FIGURE 1.

Testing of source patients after potential exposure of health care personnel to hepatitis C virus — CDC guidance, United States, 2020*

Abbreviations: AASLD-IDSA = American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases and the Infectious Diseases Society of America; HCP = health care personnel; HCV = hepatitis C virus; NAT = nucleic acid test.

* Testing of the source patient should be performed as soon as possible (preferably within 48 hour) after exposure. Testing may follow option A (preferred), which is testing with a NAT for HCV RNA, or option B, which is testing for anti-HCV with reflex to a NAT for HCV RNA if positive. If the source patient is known or suspected to have recent behaviors that increase risk for HCV acquisition (e.g., injection drug use within the previous 4 months) or if risk cannot be reliably assessed, initial testing of the source patient should include a NAT for HCV RNA. A source patient found to be positive for HCV RNA should be referred to care. Follow-up testing of HCP is recommended if the source patient is HCV RNA positive, anti-HCV positive with HCV RNA status unknown, or cannot be tested. Persons with detectable HCV RNA at any point should be referred to care consistent with current AASLD-IDSA guidelines for evaluation and treatment of all persons with acute or chronic HCV infection. Guidance for hepatitis C treatment (https://www.hcvguidelines.org) is evolving with emerging data on treatment with direct-acting antivirals.

BOX. Testing of source patients and health care personnel potentially exposed to hepatitis C virus — CDC guidance, United States, 2020.

Source-patient testing

Testing of the source patient may follow option A (preferred), which is testing with a nucleic acid test (NAT) for hepatitis C virus (HCV) RNA, or option B, which is testing for anti-HCV with reflex to a NAT if positive.

If a source patient is known or suspected to have recent behaviors that increase risk for HCV acquisition (e.g., injection drug use within the previous 4 months) or if risk cannot be reliably assessed, initial testing should include a NAT.

Follow-up testing of health care personnel (HCP) is recommended if the source patient is HCV RNA positive, anti-HCV positive with RNA status unknown, or cannot be tested.

HCP testing*

Baseline testing of HCP for anti-HCV with reflex to a NAT if positive should be conducted as soon as possible (preferably within 48 hours) after the exposure and may be simultaneous with source-patient testing.

If follow-up testing of HCP is recommended based on the source-patient’s status, test with a NAT at 3–6 weeks postexposure.

If the HCP is NAT negative at 3–6 weeks postexposure, a final test for anti-HCV at 4–6 months postexposure is recommended.

A source patient or HCP who is positive for HCV RNA should be referred to care.

* Follow-up testing of HCP is also warranted when concerns exist about specimen integrity, including handling and storage conditions that might have compromised source-patient test results, or if they exhibit any clinical signs of HCV infection.

If the source patient is known or suspected to have recent behavior risks for HCV acquisition (e.g., injection drug use within the previous 4 months) or if risk cannot be reliably assessed, initial testing should include a NAT for HCV RNA. Persons with recently acquired acute infection typically have detectable HCV RNA levels as early as 1–2 weeks after exposure (19,20). Source patients determined to be positive for anti-HCV or HCV RNA should be reported to the state or local health department (11) and referred for clinical management, as recommended (10). False-positive anti-HCV results are known to occur among populations at low risk (44).

HCV RNA testing is preferred for source patient testing. However, if anti-HCV testing is performed, a sufficient blood sample should be obtained for simultaneous or reflex (if anti-HCV positive) HCV RNA testing. This can minimize the need to redraw blood and reduce delays in establishing the status of the source patient. Testing of the source patient and baseline testing of the HCP might be either concurrent or sequential; follow-up testing of the HCP should be determined by the source patient’s status.

If the source patient is HCV RNA or anti-HCV positive with unavailable NAT or if the HCV infection status is unknown (e.g., when the HCP sustains a percutaneous injury from a needle in the trash), follow-up testing of the exposed HCP should be initiated. Follow-up testing for an HCP exposed to blood or body fluids from a source patient who tests anti-HCV positive but HCV RNA negative is not recommended because this status can indicate a previously cleared or cured infection. However, instances might occur when follow-up testing is warranted (e.g., when specimen integrity concerns exist, including handling and storage conditions, that might have compromised test results) (20) or if the HCP exhibits any clinical signs of HCV infection.

Test the HCP

Baseline Testing

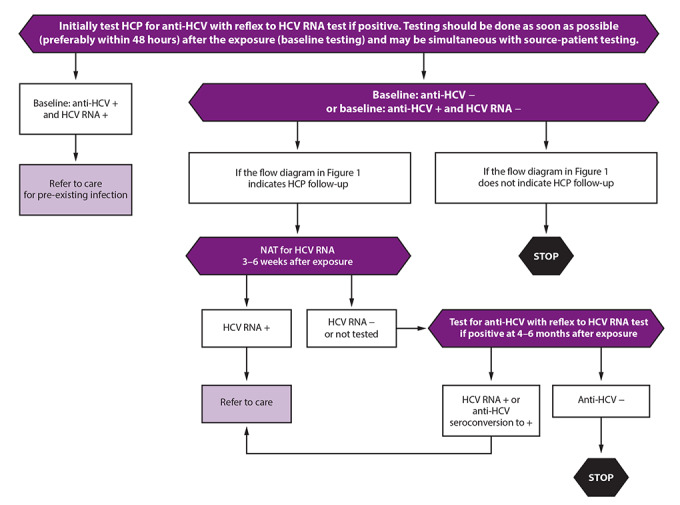

HCP should have an initial baseline test for anti-HCV with testing for HCV RNA if positive (i.e. either reflex or follow-up NAT) as soon as possible (preferably within 48 hours) after the exposure to rule out a pre-existing chronic infection (Box) (Figure 2). HCP testing positive for HCV RNA at baseline should be referred to care for pre-existing current HCV infection. If HCP are anti-HCV positive and HCV RNA negative at baseline, this likely indicates a previously cleared infection; therefore, if test results for the source patient warrant follow-up testing for HCP in context of a current exposure (Figure 1), HCP should be tested for HCV RNA instead of retesting for anti-HCV, which usually will remain positive regardless of current infection status.

FIGURE 2.

Testing of health care personnel after potential exposure to hepatitis C virus — CDC guidance, United States, 2020*

Abbreviations: AASLD-IDSA = American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases and the Infectious Diseases Society of America; HCP = health care personnel; HCV = hepatitis C virus; NAT = nucleic acid test.

* Baseline testing of HCP for anti-HCV with reflex to a NAT for HCV RNA if positive should be done as soon as possible (preferably within 48 hours) after the exposure and may be simultaneous with source-patient testing. If follow-up testing is recommended based on the source-patient’s status, test for HCV RNA at 3–6 weeks postexposure. Testing for HCV RNA performed at 6 weeks postexposure has the advantage of coinciding with human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) postexposure testing schedules if HIV surveillance is recommended. If HCV RNA is negative at 3–6 weeks postexposure, a final test for anti-HCV at 4–6 months postexposure is recommended due to the possibility of intermittent periods of aviremia in acute HCV infection. If the HCP was anti-HCV positive and HCV RNA negative at baseline, testing at this time should be conducted for HCV RNA detection, as persons successfully treated for HCV infection will remain anti-HCV positive and HCV RNA negative unless reinfected. Testing performed at 6 months postexposure has the advantage of coinciding with hepatitis B virus (HBV) postexposure testing schedules if HBV testing is recommended. HCP with anti-HCV seroconversion and negative HCV RNA should be referred for further evaluation. False-positive anti-HCV results are known to occur among low-risk populations. Anti-HCV seroconversion occurs on average 8–11 weeks after exposure, although cases of delayed seroconversion have been documented among persons with immunosuppression such as in HIV infection. For persons who had a negative anti-HCV result and are immunocompromised, testing for HCV RNA can be considered. Also, for persons with a positive anti-HCV and negative HCV RNA result, HCV RNA testing should be repeated if an additional potential HCV exposure occurred within the past 6 months, clinical evidence of HCV infection is present, or concerns exist about specimen integrity, including handling and storage conditions that might have compromised test results. Exposed persons who develop viral syndromes suggestive of acute HCV infection at any point should be retested for HCV RNA. Persons with detectable HCV RNA at any point should be referred to care consistent with current AASLD-IDSA guidelines for evaluation and treatment of all persons with acute or chronic HCV infection. Those persons with acute infection should be treated on initial diagnosis without awaiting spontaneous resolution. Guidance for hepatitis C treatment (https://www.hcvguidelines.org) is evolving with emerging data on treatment with direct-acting antivirals.

HCV PEP Not Recommended

HCV PEP with DAA therapy is not routinely recommended. The risk for transmission of HCV from percutaneous exposures (0.2%) and mucocutaneous exposures (0%) is low (4) and in most situations does not justify giving DAAs to several hundred exposed HCP because of potential side effects; furthermore, efficient duration of PEP has not been established. DAA therapy is highly efficacious in eradicating acute and chronic infections (10,15–17,40,41); therefore, new HCV infections should be identified early and treated, and the strategy of testing and treating if transmission occurs is recommended.

Testing 3–6 Weeks Postexposure

If the source patient is HCV RNA positive or source-patient testing is not performed or not available, HCP baseline testing should be followed by a NAT for HCV RNA at 3–6 weeks after exposure. This test also should be performed if a source patient is anti-HCV positive and no source patient HCV RNA testing is available. A NAT performed at 6 weeks postexposure has the advantage of coinciding with HIV postexposure testing schedules, if recommended (39).

Testing 4–6 Months Postexposure

For all HCP for whom follow-up testing is recommended, a final test for anti-HCV at 4–6 months with testing for HCV RNA if positive (i.e. either reflex to or follow-up NAT) should be conducted (1,10,39,40). Testing performed at 6 months postexposure has the advantage of coinciding with hepatitis B virus (HBV) postexposure testing schedules, if recommended (39,45). Exposed HCP who develop illness with symptoms indicative of acute HCV infection at any point should be tested for HCV RNA.

No further follow-up is indicated for HCP who remain anti-HCV negative at 4–6 months. However, for those who had a negative anti-HCV result at 4–6 months and are immunocompromised or have liver disease, an additional test for HCV RNA can be considered (20). Seroconversion from anti-HCV negative to anti-HCV positive with undetectable HCV RNA can indicate resolved infection or acute infection during a period of aviremia (31). In addition, false-positive anti-HCV tests have been reported to occur (44). For HCP with a positive anti-HCV result and confirmed undetectable HCV RNA after 4–6 months, a NAT for HCV RNA should be repeated if clinical evidence of HCV infection is present (31). Tests should be repeated if concerns exist about results being compromised because of storage and handling errors or other issues that might affect specimen integrity (20).

Management of HCP Who Acquire HCV

HCP with detectable HCV RNA or anti-HCV seroconversion as a result of an occupational exposure should be referred for further care and evaluation for treatment as indicated in AASLD-IDSA guidelines (10). Because DAA therapy is highly efficacious in eradicating acute and chronic infections (10,15–17,40,41), new HCV infections should be identified early and treated (10). Additional recommendations are available to facilitate provision of occupational infection prevention and control services to HCP (46).

Acknowledgment

Raymond Chung, Massachusetts General Hospital, Boston.

Conflicts of Interest: All authors have completed and submitted the International Committee of Medical Journal Editors form for disclosure of potential conflicts of interest. No potential conflicts of interest were disclosed.

References

- 1.CDC. Updated U.S. Public Health Service guidelines for the management of occupational exposures to HBV, HCV, and HIV and recommendations for postexposure prophylaxis. MMWR Recommend Rep 2001;50(No. RR-11). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Mitchell AH, Parker GB, Kanamori H, Rutala WA, Weber DJ. Comparing non-safety with safety device sharps injury incidence data from two different occupational surveillance systems. J Hosp Infect 2017;96:195–8. 10.1016/j.jhin.2017.02.021 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.International Safety Center. EPINet sharps injury and blood and body fluid data reports. Charlottesville, VA: University of Virginia [undated]. https://internationalsafetycenter.org/exposure-reports

- 4.Egro FM, Nwaiwu CA, Smith S, Harper JD, Spiess AM. Seroconversion rates among health care workers exposed to hepatitis C virus-contaminated body fluids: the University of Pittsburgh 13-year experience. Am J Infect Control 2017;45:1001–5. 10.1016/j.ajic.2017.03.011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Goel V, Kumar D, Lingaiah R, Singh S. Occurrence of needlestick and injuries among health-care workers of a tertiary care teaching hospital in North India. J Lab Physicians 2017;9:20–5. 10.4103/0974-2727.187917 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Jagger J, Puro V, De Carli G. Occupational transmission of hepatitis C virus. JAMA 2002;288:1469–71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Morin T, Pariente A, Lahmek P; Investigator Group of ANGH, SPILF, FNPRH. Favorable outcome of acute occupational hepatitis C in healthcare workers: a multicenter French study on 23 cases. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol 2011;23:515–20. 10.1097/MEG.0b013e3283470241 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Yazdanpanah Y, De Carli G, Migueres B, et al. Risk factors for hepatitis C virus transmission to health care workers after occupational exposure: a European case-control study. Clin Infect Dis 2005;41:1423–30. 10.1086/497131 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bukh J, Meuleman P, Tellier R, et al. Challenge pools of hepatitis C virus genotypes 1-6 prototype strains: replication fitness and pathogenicity in chimpanzees and human liver-chimeric mouse models. J Infect Dis 2010;201:1381–9. 10.1086/651579 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases; Infectious Diseases Society of America. HCV guidance: recommendations for testing, managing, and treating hepatitis C. Alexandria, VA; Arlington, VA: American Association for the Study of Liver Disease; Infectious Diseases Society of America [undated]. https://www.hcvguidelines.org [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 11.CDC. Reported number of acute hepatitis C cases—United States, 2001–2017. In: Surveillance for viral hepatitis—United States, 2017. Atlanta, GA: US Department of Health and Human Services, CDC; 2019. https://www.cdc.gov/hepatitis/statistics/2017surveillance/TablesFigures-HepC.htm

- 12.Micallef JM, Kaldor JM, Dore GJ. Spontaneous viral clearance following acute hepatitis C infection: a systematic review of longitudinal studies. J Viral Hepat 2006;13:34–41. 10.1111/j.1365-2893.2005.00651.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Seo S, Silverberg MJ, Hurley LB, et al. Prevalence of spontaneous clearance of hepatitis C virus infection doubled from 1998 to 2017. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol 2020;18:511–3. 10.1016/j.cgh.2019.04.035 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Henderson DK, Dembry L, Fishman NO, et al. Society for Healthcare Epidemiology of America. SHEA guideline for management of healthcare workers who are infected with hepatitis B virus, hepatitis C virus, and/or human immunodeficiency virus. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol 2010;31:203–32. 10.1086/650298 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Naggie S, Fierer DS, Hughes MD, et al. Acquired Immunodeficiency Syndrome Clinical Trials Group (ACTG) A5327 Study Team. Ledipasvir/sofosbuvir for 8 weeks to treat acute hepatitis C virus infections in men with human immunodeficiency virus infections: sofosbuvir-containing regimens without interferon for treatment of acute HCV in HIV-1 infected individuals. Clin Infect Dis 2019;69:514–22. 10.1093/cid/ciy913 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Boerekamps A, De Weggheleire A, van den Berk GE, et al. Treatment of acute hepatitis C genotypes 1 and 4 with 8 weeks of grazoprevir plus elbasvir (DAHHS2): an open-label, multicentre, single-arm, phase 3b trial. Lancet Gastroenterol Hepatol 2019;4:269–77. 10.1016/S2468-1253(18)30414-X [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Deterding K, Spinner CD, Schott E, et al. HepNet Acute HCV IV Study Group. Ledipasvir plus sofosbuvir fixed-dose combination for 6 weeks in patients with acute hepatitis C virus genotype 1 monoinfection (HepNet Acute HCV IV): an open-label, single-arm, phase 2 study. Lancet Infect Dis 2017;17:215–22. 10.1016/S1473-3099(16)30408-X [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Rockstroh JK, Bhagani S, Hyland RH, et al. Ledipasvir-sofosbuvir for 6 weeks to treat acute hepatitis C virus genotype 1 or 4 infection in patients with HIV coinfection: an open-label, single-arm trial. Lancet Gastroenterol Hepatol 2017;2:347–53. 10.1016/S2468-1253(17)30003-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kleinman SH, Lelie N, Busch MP. Infectivity of human immunodeficiency virus-1, hepatitis C virus, and hepatitis B virus and risk of transmission by transfusion. Transfusion 2009;49:2454–89. 10.1111/j.1537-2995.2009.02322.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Association of Public Health Laboratories. Interpretation of hepatitis C virus test results: guidance for laboratories. Silver Spring, MD: Association of Public Health Laboratories; 2019. https://www.aphl.org/aboutAPHL/publications/Documents/ID-2019Jan-HCV-Test-Result-Interpretation-Guide.pdf

- 21.Busch MP, Kleinman SH, Jackson B, Stramer SL, Hewlett I, Preston S. Committee report. Nucleic acid amplification testing of blood donors for transfusion-transmitted infectious diseases: report of the Interorganizational Task Force on Nucleic Acid Amplification Testing of Blood Donors. Transfusion 2000;40:143–59. 10.1046/j.1537-2995.2000.40020143.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Glynn SA, Wright DJ, Kleinman SH, et al. Dynamics of viremia in early hepatitis C virus infection. Transfusion 2005;45:994–1002. 10.1111/j.1537-2995.2005.04390.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hajarizadeh B, Grebely J, Applegate T, et al. ATAHC study group. Dynamics of HCV RNA levels during acute hepatitis C virus infection. J Med Virol 2014;86:1722–9. 10.1002/jmv.24010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lavillette D, Morice Y, Germanidis G, et al. Human serum facilitates hepatitis C virus infection, and neutralizing responses inversely correlate with viral replication kinetics at the acute phase of hepatitis C virus infection. J Virol 2005;79:6023–34. 10.1128/JVI.79.10.6023-6034.2005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Mosley JW, Operskalski EA, Tobler LH, et al. Transfusion-transmitted Viruses Study and Retrovirus Epidemiology Donor Study Groups. The course of hepatitis C viraemia in transfusion recipients prior to availability of antiviral therapy. J Viral Hepat 2008;15:120–8. 10.1111/j.1365-2893.2007.00900.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Nübling CM, Unger G, Chudy M, Raia S, Löwer J. Sensitivity of HCV core antigen and HCV RNA detection in the early infection phase. Transfusion 2002;42:1037–45. 10.1046/j.1537-2995.2002.00166.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Page K, Osburn W, Evans J, et al. Frequent longitudinal sampling of hepatitis C virus infection in injection drug users reveals intermittently detectable viremia and reinfection. Clin Infect Dis 2013;56:405–13. 10.1093/cid/cis921 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Thimme R, Oldach D, Chang KM, Steiger C, Ray SC, Chisari FV. Determinants of viral clearance and persistence during acute hepatitis C virus infection. J Exp Med 2001;194:1395–406. 10.1084/jem.194.10.1395 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Villano SA, Vlahov D, Nelson KE, Cohn S, Thomas DL. Persistence of viremia and the importance of long-term follow-up after acute hepatitis C infection. Hepatology 1999;29:908–14. 10.1002/hep.510290311 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Wang CC, Krantz E, Klarquist J, et al. Acute hepatitis C in a contemporary US cohort: modes of acquisition and factors influencing viral clearance. J Infect Dis 2007;196:1474–82. 10.1086/522608 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Gruener NH, Heeg M, Obermeier M, et al. Late appearance of hepatitis C virus RNA after needlestick injury: necessity for a more intensive follow-up. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol 2009;30:299–300. 10.1086/595979 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Weseslindtner L, Neumann-Haefelin C, Viazov S, et al. Acute infection with a single hepatitis C virus strain in dialysis patients: analysis of adaptive immune response and viral variability. J Hepatol 2009;50:693–704. 10.1016/j.jhep.2008.11.023 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Bunchorntavakul C, Jones LM, Kikuchi M, et al. Distinct features in natural history and outcomes of acute hepatitis C. J Clin Gastroenterol 2015;49:e31–40. 10.1097/MCG.0000000000000076 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Sacks-Davis R, Grebely J, Dore GJ, et al. InC3 study group. Hepatitis C virus reinfection and spontaneous clearance of reinfection—the InC3 Study. J Infect Dis 2015;212:1407–19. 10.1093/infdis/jiv220 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Larghi A, Zuin M, Crosignani A, et al. Outcome of an outbreak of acute hepatitis C among healthy volunteers participating in pharmacokinetics studies. Hepatology 2002;36:993–1000. 10.1053/jhep.2002.36129 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Thomson EC, Nastouli E, Main J, et al. Delayed anti-HCV antibody response in HIV-positive men acutely infected with HCV. AIDS 2009;23:89–93. 10.1097/QAD.0b013e32831940a3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Vanhommerig JW, Thomas XV, van der Meer JT, et al. MOSAIC (MSM Observational Study for Acute Infection with Hepatitis C) Study Group. Hepatitis C virus (HCV) antibody dynamics following acute HCV infection and reinfection among HIV-infected men who have sex with men. Clin Infect Dis 2014;59:1678–85. 10.1093/cid/ciu695 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Abara WE, Collier MG, Moorman A, et al. Characteristics of deceased solid organ donors and screening results for hepatitis B, C, and human immunodeficiency viruses—United States, 2010–2017. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 2019;68:61–6. 10.15585/mmwr.mm6803a2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.University of California at San Francisco/Clinician Consultation Center. PEP quick guide for occupational exposures: exposures to HCV. San Francisco, CA: University of California; 2019. http://nccc.ucsf.edu/clinical-resources/pep-resources/pep-quick-guide-for-occupational-exposures/#_edn1

- 40.Naggie S, Holland DP, Sulkowski MS, Thomas DL. Hepatitis C virus postexposure prophylaxis in the healthcare worker: why direct-acting antivirals don’t change a thing. Clin Infect Dis 2017;64:92–9. 10.1093/cid/ciw656 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Hughes HY, Henderson DK. Postexposure prophylaxis after hepatitis C occupational exposure in the interferon-free era. Curr Opin Infect Dis 2016;29:373–80. 10.1097/QCO.0000000000000281 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.National Library of Medicine. HCV post-exposure prophylaxis for health care workers [Internet]. Bethesda, MD: National Library of Medicine [undated]. https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT03313414?id=NCT03313414&rank=1&load=cart

- 43.CDC. Testing for HCV infection: an update of guidance for clinicians and laboratorians. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 2013;62:362–5. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Moorman AC, Drobenuic J, Kamili S. Prevalence of false-positive hepatitis C antibody results, National Health and Nutrition Examination Study (NHANES) 2007–2012. J Clin Virol 2017;89:1–4. 10.1016/j.jcv.2017.01.007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Schillie S, Murphy TV, Sawyer M, et al. CDC. CDC guidance for evaluating health-care personnel for hepatitis B virus protection and for administering postexposure management. MMWR Recomm Rep 2013;62(No. RR-10). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.CDC. Infection control in healthcare personnel: infrastructure and routine practices for occupational infection prevention and control services (2019). Atlanta, GA: US Department of Health and Human Services, CDC; 2019. https://www.cdc.gov/infectioncontrol/guidelines/healthcare-personnel/exec-summary.html?deliveryName=USCDC_425-DHQP-DM11130