Abstract

In the last few decades, there have been numerous crises and disasters that negatively affected the hospitality industry. Different countries around the world experienced natural disasters, financial crises, violent attacks, and public health crises, all of which were studied in detail, except for public health crises. Thus, this study focuses on the effects of the Covid-19 public health crisis on the hospitality industry from the viewpoint of a select group of hospitality leaders in the USA, Israel, and Sweden. The opinions and viewpoints of these leaders focused on the handling of the Covid-19 crisis through the lens of the social systems theory and Hofstede's (1980) cultural dimensions.

Keywords: COVID-19 pandemic, Health-related crisis, Hospitality industry, Qualitative research

1. Introduction

According to Laws and Prideaux (2005), a crisis is an event that suddenly transpires into an unfavorable situation. The hospitality industry has become of growing importance to the global economy, and the COVID-19 pandemic has laid bare the industry’s vulnerability. The hospitality industry involves a large number of customers and employees and high exposure to both national and international guests, which dramatically increases the potential for exposure to and spreading of infections (Leung & Lam, 2004). However, the COVID-19 pandemic is an ongoing event and only a few previous studies have focused on the impact of public health crises on the hospitality industry, as most research has focused on economic rather than public health crises (Mair et al., 2014; Jian et al., 2017).

According to Pizam and Mansfeld (1996), Lepp and Gibson (2003), and Taylor and Toohey (2006), perceptions of personal and physical security influence people’s intentions to travel to a destination that suffers from security concerns, and these perceptions are fueled in part by the media (Kozak et al., 2007), friends and family (Murphy et al., 2007; Gitelson and Kerstetter, 1995), and by information released by government agencies such as the US Center for Disease Control and the US State Department. According to Schroeder and Pennington-Gray (2014) public health-related crises, such as epidemics, are always covered by the media in a negative light. Countries heavily impacted by the COVID-19 pandemic went as far as to close down (Tanne et al., 2020). In 2020, travel restrictions took effect across the globe, creating an economic crisis of unprecedented magnitude (Tanne et al., 2020; Fernandes, 2020). In Israel, 82% of all employment is in the service sector (Plecher, 2020a). In Sweden, 65% of gross domestic product (GDP) is generated by the service sector (Plecher, 2020b). In the United States, the service industry is responsible for 77% of GDP and is one of the largest job creators (Duffin, 2020).

As the global economy moves from a manufacturing economy toward a service economy, the of study of hospitality crisis management is crucial for two reasons. First, overreliance on revenue from the hospitality industry can be devastating (Israeli and Reichel, 2003), as lost revenue contributes to a downward economic trend and increased unemployment (Henderson, 2007; Karsavuran, 2020). The second reason is that the way a country, industry, or company manages its recovery plays a significant role in how well that country, industry, or company emerges from a crisis (Racherla and Hu, 2009). As Racherla and Hu state, “An organization’s crisis management capabilities should be of such quality that an evolving crisis can be resolved quickly and prevented from spreading to the extent possible” (2009 p. 562). The COVID-19 pandemic is an ongoing event

so understanding its full impact on the international hospitality industry from a leadership perspective and its potential consequences are not yet fully understood.

This qualitative study has three aims: 1) to examine the opinions and viewpoints of hospitality leaders on the impact of COVID-19 on their personal life, the company they work for, the hospitality industry, their country, and the world, using Social Systems Theory (SST); 2) to evaluate what actions were taken to ameliorate effects of COVID-19; 3) to evaluate whether perceptions of COVID-19’s effects on the hospitality industry vary, using Hofstede’s five cultural dimensions. In the following sections, the literature is revised with further explanations that justify the proposed prediction.

2. Literature review

2.1. Public health-related crises

Over the last 50 years, according to Statista, major virus outbreaks such as H1N1 in 2009 (284,500 deaths), Ebola in 1976 (13,562 deaths), SARS (severe acute respiratory syndrome) in 2002 (774 deaths), H7N9 (bird flu) in 2013 (616 deaths), and COVID-19 in 2020 (1.090 million + deaths) created tangible shocks to the world (Elflein, 2020). The impact of these outbreaks on the hospitality industry in the affected countries was enormous. Some researchers have studied the effects of such outbreaks on the hospitality and restaurant industry. For example, in 1976, Bellevue Stratford Hotel in Philadelphia experienced a fatal Legionnaires’ disease outbreak and closed four months later due to a drop in bookings, which went from 80% occupancy to as low as 3% (Markel, 2018). In 1993, the Jack-in-the-Box restaurant company in Fan Francesco experienced a large-scale E. coli outbreak, which nearly bankrupted the company (Andrews, 2013).

2.2. SARS

Similar to COVID-19, SARS was declared a “pandemic” by the World Health Organization (WHO) in 2003. This declaration, alongside extensive media coverage, resulted in a global panic.

The SARS outbreak illustrated the link between travel, tourism, and infectious disease (Henderson and Ng, 2004; McKercher and Chon, 2004; Washer, 2004) that spread globally through international tourists returning home after visiting affected areas (Mason et al., 2005). The outbreak caused an unprecedented move by the WHO: after 45 years, it issued a “general travel advisory” that closed borders and discouraged travel to affected areas. China, Hong Kong, Vietnam, and Singapore lost an estimated US$20 billion in GDP and three million jobs in the tourism sector (Kuo et al., 2008). Many destinations experienced dramatic declines in revenue and visitor numbers. Toronto, Canada, lost 4.5 million dollars in revenue over the same period the year before, and in 2004 Asia saw a 70% decline in tourist arrivals (McKercher and Chon, 2004; Rosszell, 2003). Similarly, Chien and Law (2003) found that hotels in Hong Kong during the pandemic dropped from 80% occupancy to 10%, which led many to go out of business or institute massive pay cuts and indefinite no-pay leave.

2.3. Ebola

The Ebola outbreak of December 2013, traced to Guinea, was the first time the disease had resurfaced since 1976 and was the deadliest incident since the disease’s discovery. The Ebola virus caused its victims to experience fever, vomiting, and diarrhea, and the death rate was very high. Kongoley (2015) found that the Ebola outbreak in Sierra Leone in 2014 caused hotels, restaurants, night clubs, casinos, and guest houses to close, leading to a 20% unemployment rate. According to Maphanga and Henama (2019), Tanzania experienced a 30%–40% decline in lodging occupancy rates and overall economic retraction across the infected African countries. Nigeria was also severely impacted by Ebola (Bali et al., 2016).

2.4. Covid-19

According to Statista (2019), in 2019, the global travel and tourism industry directly contributed 2.9 trillion USD to the global GDP (Lock, 2020a). Employment in the hospitality industry has never been as high or as in the last few years. Unfortunately, this ended abruptly in late February and early March 2020. The first cases of COVID-19 pandemic began in China in early December of 2019 and spread quickly to Europe, the USA, and the rest of the world. Since February 2020, US hotels have lost in excess of $46 billion, and 4.8 million hospitality and leisure jobs have been lost. Lodging operations such as the AHLA in the USA projected occupancy rates below 20% in the last few months of 2020 (AHLA, 2020). In Israel, the lodging industry is losing $142 million a month, according to the Israel Hotel Association (JNS, 2020). In Sweden, the average lodging occupancy rate dropped 34% from August 2019 to August 2020, resulting in a financial loss of 1.6 billion Swedish kronor ($182 million USD) (Nyhetsrummet, 2020), and the US lodging occupancy rate showed a year-over-year decrease of 30% (Lock, 2020b).

2.5. Social systems theory (SST)

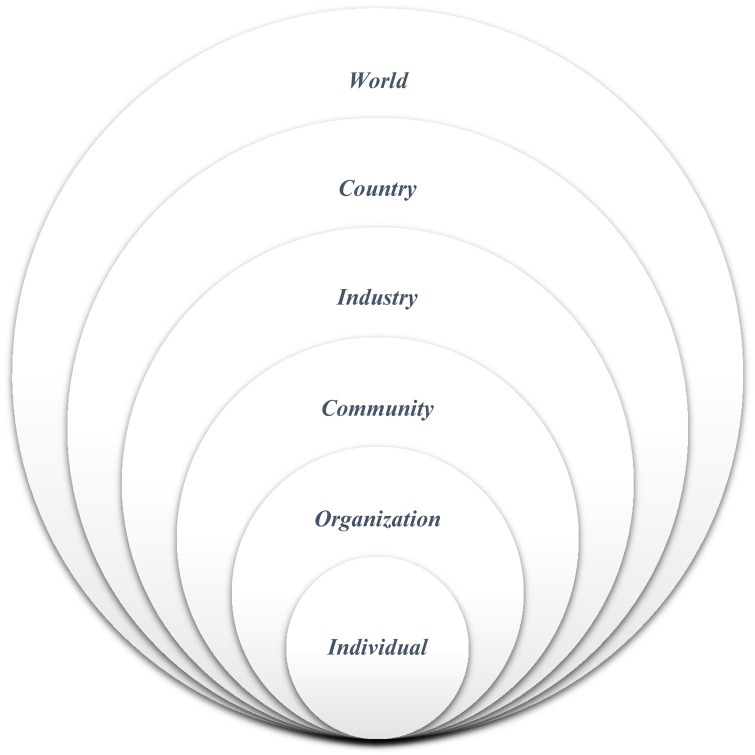

This study utilizes SST to identify the opinions, feelings, and attitudes of hotel managers on the effects of COVID-19 on their personal lives, communities, workplaces, hospitality industry, and country as a whole. SST is the study of society as a complex arrangement of elements, including individuals and human groups, as they relate to a whole such as a country or the world. It is concerned with the interaction or relationship between each subgroup (Dossa, 1990). SST posits that the components (parts) of the system are interconnected, and what happens in one component affects the others and the system as a whole. The foundation of SST is communities (Reicherter and Billek-Sawhney, 2003). While SST has not been extensively used in hospitality and tourism research, it was employed by Reicherter and Billek-Sawhney (2003) as a tool for analyzing social systems and emphasizing the need for older adult communities to promote welfare among the community and residents (Reicherter and Billek-Sawhney, 2003). SST was used to examine the interrelations between individuals and their communities, such as hospitality organizations, the hospitality industry, the country, and the world as they relate to the COVID-19 pandemic. That is, this study shows how COVID-19 has affected individuals and their communities in Sweden, Israel, and the USA.

2.6. Cultural differences theory

Hofstede (1980) developed a five-dimensional model on which the differences among national cultures can be understood. The five dimensions are individualism vs collectivism, power distance, uncertainty avoidance, masculinity vs. femininity and long-term vs. short-term orientation. In 2010, Hofstede et al. (2010) added a sixth dimension by the name of indulgence vs. restraint. and Crotts and Pizam (2003) found that national cultures affect the evaluation of travel services and ultimately the willingness to do repeat purchases. Furthermore, Crotts and Erdmann (2000) p. 417) provided in their study “tentative evidence in support of Hofstede’s conceptual framework that national culture influences consumers’ willingness to report dissatisfaction.” Respondents from highly masculine societies with dominant traits being achievement, assertiveness, and material rewards more often showed a willingness to report dissatisfaction than respondents from low to moderately masculine societies. Ahlawat (2016) study concludes that Hofstede’s scorecard for each country can provide human resource managers better insight into the employees’ countries culture while also helping to manage various aspects of human resource management practices. Kristjansdottir (2019) found that Hofstede’s cultural dimensions suggested that only uncertainty avoidance and individualism positively impacted tourism inflow, while power distance, masculinity, and orientation had a negative impact on tourism. Litvin (2019) found that prior research has indicated that Hofstede’s cultural dimensions of uncertainty avoidance explain travel planning and vacation behaviors. Furthermore, current research indicates that cultural dimensions also explains post-trip attitude and satisfaction. Each country in comparison to each other will vary; for instance, Israel’s data may be skewed as they have such a large immigrant population, and new citizens change the existing values (Hofstede Insights, 2020).

2.6.1. Power distance

The power distance of each country, defined as the extent to which less powerful members of institutions and organizations within a country expect and accept that power is distributed unequally, differs slightly between the countries examined here, with Sweden scoring 31, the US scoring 40, and Israel scoring 13. Israel’s low score reflects its belief in an egalitarian mindset. Israelis believe in independence and equal rights for employees. Israelis earn respect in their careers through experience; everyone relies on each other and expects to be consulted when decisions are made. The same is apparent in Sweden, too. While Swedes score a bit higher on power distance, they have similar views to Israelis. The difference in the USA is that everyone is considered unique, so they are not equal. However, the combination of a low score (40) for power distance and the highest score (91) for individualism reflects the USA’s focus on the premise of “liberty and justice for all” (Hofstede Insights, 2020).

2.6.2. Individualism vs. collectivism

Individualism is a huge part of US culture. In their careers, Americans are required to be selfreliant and to show initiative beyond what their supervisors tell them to do. This individualism plays a part in upward movement and promotions. Sweden scores 71 in individualism, confirming the similarities between Sweden and the USA. They are both individualistic communities and are focused on themselves and the wellbeing of their families and no one else. Israel, with a score of 54, is on the border between individualistic and collectivistic, with some families focusing on the parent–child relationship instead of the extended family, and others focusing on the relationship of the family, as a whole, in society (Hofstede Insights, 2020).

2.6.3. Masculinity vs. femininity

Hofstede’s third dimension is masculine/feminine. A country with a high score is considered masculine, which means it is considered to be driven by competition and success to be a winner. Scoring low is considered feminine and focuses on the quality of life and caring for others. Each country ranked differently for this dimension. Sweden scored 5, putting it in the feminine category. Swedes live by the Lagom (just the right amount), enforced by “Jante Law” (egalitarian lifestyle), which repels a masculine lifestyle. With a score of 62, the USA is the opposite of Sweden and a masculine society. According to Hofstede’s theory, Americans like to show off their successes and are driven by competition. Israel is considered neutral, with a score of 47, and exhibits characteristics of both masculine and feminine societies. Some Israelis are showing off their status with material items (masculine), while others do not, focusing on their families and quality of life instead (feminine) (Hofstede Insights, 2020).

2.6.4. Uncertainty avoidance

The uncertainty avoidance dimension refers to the degree to which members of society handle ambiguous or unknown factors relating to the future and the beliefs these cultures hold to avoid such things. Israel (81) holds the strongest uncertainty avoidance index among the three. This score shows that Israelis are very expressive, need rules in their society, and value security and hard work. Sweden (29) reflects the opposite, with a relaxed environment, as demonstrated in other dimensions. Sweden remains open to innovative ideas, as does the USA (46), which allows for advances in society and deviation from norms, resulting in freedom of expression (Hofstede Insights, 2020).

2.6.5. Long-term vs. short-term orientation

Long-term orientation describes how each society handles changes in the present and future while maintaining a connection to the past; each country prioritizes each goal differently. Low scores on this dimension reflect a normative society that honors traditions and is skeptical of change, while high scores reflect pragmatism and looking to the future in an open-minded way. Both the USA (26) and Israel (38) are considered normative societies. Israel’s score supports its high score in the uncertainty avoidance dimension: Israelis do not stray from traditional culture and focus on the present. Americans tend to validate the information in search of the truth, making them practical rather than pragmatic. Sweden (46) shows no preference for a pragmatic or normative approach (Hofstede Insights, 2020).

2.6.6. Indulgence vs. restraint

Indulgence stands for a society that allows relatively free gratification of basic and natural human drives related to enjoying life and having fun. Restraint stands for a society that suppresses gratification of needs and regulates it by means of strict social norms (Hofstede Insights, 2020)

3. Methodology

3.1. Research approach and sampling

We adopted an inductive qualitative approach, utilizing open-ended questions for in-depth interviews using the SST framework. The COVID-19 pandemic is novel so not much is known about the evolving and increasing crisis. In the instance of novel problems where understanding must be developed about how things are happening, qualitative research is more appropriate than quantitative research (Strauss and Corbin, 1998; Tetnowski and Damico, 2001; Kaushal and Srivastava, 2020). This study used non-probability criterion sampling, which seeks cases that meet some criterion that is useful for quality assurance (Creswell and Poth, 2018). The key criterion for inclusion was a formal leadership position (in a top or high-level management position), working in the USA, Israel, or Sweden, and employed in the hospitality industry. Beyond these critical factors, we recorded other demographic aspects that might influence findings, such as position, level of education, marital status, and gender. We did not aim to collect a generalizable sample, but we did seek a homogeneous criterion for a comparative sample from three countries. Consequently, we recruited people in leadership positions or business owners for a valid comparison. Further, for ethical reasons, we left it optional for participants to report their income, and we did not ask about sexual orientation to avoid the perception of segmentation or purposeful selection and to show sensitivity. Most participants willingly identified their gender, marital status, and education but did not disclose their income. All names and affiliations are kept confidential (Fig. 1 ).

Fig. 1.

Social System Theory Representation.

The research did not offer any external incentive for participation; however, participants expressed curiosity about other leaders’ opinions in the study. Hence, we offered a summary of the study results to all participants. We contacted potential participants through a number of channels, including, but not limited to, hospitality associations, business contacts, and pre-existing university databases. Regardless of communication source or country, information on the study was given to all potential participants when soliciting participation, and the criterion was consistent.

Data was collected between May 2020 and August 2020. The final sample totaled 45 participants, 15 from the USA, 16 from Israel, and 14 from Sweden. The sample sizes were consistent with previous influential qualitative research methodology recommendations. Specifically, Dukes (1984) recommends 3–10 participants, Wolcott (2008) any participant above one, Yin (2014) 4–5 cases, and Creswell and Poth Cheryl (2018) advises that sampling should continue until the study reaches saturation (e.g., the information provided by participants is repetitive).

3.2. Interviews

All interviews followed the SST. All participants were asked six main questions and additional probing questions to solicit more in-depth answers. This strategy provided greater depth to participants’ stories and utilized sensitizing concepts (Given, 2008; Lugosi et al., 2016). The full interview guide is provided in Appendix 1. Due to the COVID-19 pandemic, all interviews were conducted via the online platform, Zoom. Permission was sought to record participants, and once granted, the interview proceeded. On average, interviews lasted 60 min. Interviews in Israel were conducted in Hebrew, fully transcribed, translated into English, verified by a native speaker, and back-translated to verify consistency and validity of the interview translation. Interviews in Sweden were conducted in English, so no translation was necessary. All interviews were transcribed verbatim before being used for the study.

4. Findings and discussion

4.1. Demographics

The USA and Israel samples were dominated by males (12 and 14). Sweden's gender category was more evenly distributed, with eight males and six females. The education category was mainly bachelor degrees (U.S. 11, Israel 8, and Sweden 11). Marital status in the USA and Israel was mainly married (8 and 13 respectively), whereas Sweden had more domestic partners (9).

Finally, the job position category in the USA was seven at the director level while Israel and Sweden had five and six respectively business owners. Details of demographic variables are described in Table 1 .

Table 1.

Demographics.

| USA | Israel | Sweden | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | |||

| Male | 12 | 14 | 8 |

| Female | 3 | 2 | 6 |

| Education | |||

| Master | 3 | 3 | |

| Bachelor | 11 | 8 | 11 |

| Vocation School | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| High school | 3 | ||

| Marital Status | |||

| Married | 8 | 13 | 6 |

| Partner | 1 | 9 | |

| Divorced | 2 | 1 | |

| Single | 1 | ||

| Position | |||

| Owner/CEO | 4 | 5 | 6 |

| Manager/GM | 1 | 3 | 4 |

| Director/President | 7 | 2 | |

4.2. The COVID-19 pandemics effect on an individual level

On an individual level, most of the participants in all three countries displayed strong emotions of despair, stress, anxiety, denial, fear for the unknown, concerns for their jobs, and worry for the wellbeing of their families.

4.2.1. The United States

In the case of the American subjects, Hofstede’s (1980) theory of individualism was strongly was confirmed. The American subjects focused mainly on themselves and their family. During interviews, all participants deviated towards individualism. For example:

“I think initially you know for my wife, and I was automatically worried, you can't help as a human being but worry about the future because it is unexpected. It is unknown, so I think there's an automatic sense of worry, and there's the fear of the unknown… like, what's going to happen because we don't know what's going to happen.” (P 3)

“…stress at home because I had my elderly mother with us and not being able to go out into public because I couldn't bring it back to her has just it's been a lot in the last three months” (P7)

“…initially it was, you know, very scary…it was just … this shock…certainly fear, I am upset, I feel strong emotions fear, anger, despair” (P.10).

Masculinity has taken a priority in their lives before pandemic but became less dominant during the pandemic when focus shifted to the family and friends. For example:

“There's my son, my daughter in law. My granddaughter. They came over more just to my house I cooked more for them. We played board games…I mean it was just a time of bonding for us.” (P.11)

“I think that [COVID-19 lockdown] definitely has helped me take a step back and reevaluate. You know, what are the things that are important… I have connected more deeply. I think I connect now more with friends and family.” (P.4)

“I've learned to appreciate how fragile actually life is and circumstances are…” (P.6)

4.2.2. Israel

In Israel, the personal effects of COVID-19 were most expressive and portrayed a strong sense of loss in the business and intense emotions about family, colleagues, and uncertainty.

Supporting the lowest score on individualism the highest on uncertainty avoidance scale among all three countries. Israeli participants shared:

“My hotel had worked at a speed of 120 km/h and in one day was down to zero. There is a lot of stress, managing 5600 employees, thinking of what to do with each one, how to take care of them. This is where the personal and emotional issue comes in a bit, we are all human beings and you must think about the implications for the people” (P3).

“The feeling is a terrible feeling of instability. Feeling of crisis, we’ve gone through a lot of crises in the industry, but we haven’t had a crisis which led to a complete stop to 0% work. The skies are closed, and there is uncertainty affecting the situation, a lot of uncertainty (P.6)

My family is in France, and I can’t visit them. It’s not that I can’t visit them … it bothers me a lot” (P. 11)

“…on a personal level I'm fine, I’m working, but sometimes it's not easy to get up in the morning, to get to the office, as someone has said: we work in reverse all day. Instead of selling we are busy with refunds, reports, discussions with suppliers, with customers… legal matters.” (P.13)

“I’m considering everything. I am considering a career change. I'm not sure I'll do it eventually, but yeah” (P.4)

On the positive side, unlike the USA, the Israeli participants are not rediscovering family connections but seem to already have a strong family connection and seek solace in it. Participants shared:

“Even my friends … I sometimes call to support them and get support from them, and at the end of the day they too just sit at home” (P2)

I tried to think how I can enjoy being with my family, to stop everything else - something I had not done…” (P.11)

4.2.3. Sweden

Participants from Sweden expressed a bit more philosophical point of view, and while it affected them emotionally, there was a perception that while they feel the effects of COVID-19 on the emotional level, there is an amount of steadiness in the emotions overall view on the personal level. Unlike the USA and Israel, participants in Sweden did not show strong emotional fluctuations between business and family but instead accepting the pandemic and steadiness. This supports Hofstede (1980) model of Swedish people being more long-term oriented (53) and having the lowest score on uncertainty avoidance (29) and masculinity (5). Participants expressed the following views:

“Many different phases, of course, a certain panic in the beginning when there were so many negative events in quick succession.” (P1)

“It was more like an “in your face” sensation that this was something serious and that “ok, now we won’t see each other for a while,” but all in all it felt more like accepting the facts and trying to stay calm and focusing on the fact that considering the situation.” (P.9)

“Well, I am a born optimist, and I have made it so far, and I think I will recover as soon as this is over. Of course, I am thinking about it. 51 years old, how easy is it to find a job? No, I don’t think it has affected me that much emotionally. I have the same positive view as a few months ago.” (P. 12)

4.3. COVID-19 effect on an organizational level

4.3.1. The United States

On the questions of “how the COVID-19 pandemic affected your organization?”, participants in the USA expressed a strong sense of shock and anxiety and worry about financial hardships and how unfavorable prognosis is for their organizations' future. For example:

“An incredible dropping in sales and revenue, it was the biggest thing that occurred. A lot of my employees decided that they would not work in this environment because of their fear of either infecting themselves or infecting someone within their family.” (P.2)

“In a big way…we closed doors for a hotel in March I think it was initially, just the two weeks and obviously that is not the case… there's several months’ business interruptions for this organization here and the same pictures our hotels around the world… a huge number of properties within the brand, of course, have had to close their doors due to local restrictions or just lack of business. So there's definitely been a major impact.” (P.6)

“It's been devastating for our resort. We've been closed, so we're going on our third month of closure. We had an incredibly difficult week last week. We laid off 380 employees last week. I kind of gave myself a different ability over the last couple of days to look at this and kind of work through what some of it emotionally means for them and for me. But it's been a roller coaster of the good of helping and then bad of delivering some very unfortunate news last week.” (P.7)

Managers noted changes in hotel guests, for example:

“… emotional escalation emotionally charged, I suppose. So you feel that people are more stressed and taking it off on employees. So how did you perceive the dynamic. The way that I'm seeing that we have more people staying in our hotels who are not seasoned travelers. We have seen more of that we've seen more alcohol abuse. When people check in more partying in our hotels.” (P.11)

On the positive side, hospitality leaders in the USA find increased feelings of empathy and compassion. Contrary to Hofstede (1980) claims and scores, US managers showed deviation from the masculinity dimension to feminine. Several managers stated:

“I feel my empathy for people. It's a very challenging experience to kind of watch what this has done, everybody long term and short term employees have been here, so I feel a lot of empathy and sadness probably towards you know employees that may not return to work” (P.4)

“The COVID has brought people together not physically as we're social distancing …but you care for people more, you tend to understand people more you want to understand and listen and coupled with what happened in our within our society.” (P.15)

Moreover, there is an increase in innovation and adaptation with the use of technology. Thus, showing support for below-average scores for uncertainty avoidance (46) (Hofstede insights, 2020). Several participants said:

“Technology that was I think that was a positive thing for us and will continue to be, but maybe relying on technology or implementing technology to help so it would not be so laborious or people-intensive.” (P.5)

4.3.2. Israel

In Israel, the hospitality participants expressed strong distress about how much negative impact COVID-19 had on their hospitality organization, concern for employees, and hotel guests' quality. Again supporting Hofstede (1980) finding for a very high score of uncertainty avoidance.

“Most of them are on unpaid leave because there are a lot of veteran employees here; many of them have accrued a lot of days off over the years. The CEO, in a very wise decision, I think, told them first to use the days off, I'm talking about dozens of days off.” (P.1)

“…towards March 20th, they shut us down completely. I sat with the owner, we had dismissed all the employees, and at this point, I cannot bring anyone back, and I’m waiting until things return to normal. I sat down with the CEO, and we said goodbye to almost 400 employees."(P.2)

“I found myself talking to employees at night, whereas during normal times, it was not meant to be like that. You know there is a hierarchy, not because of ego or anything, but there is a hierarchy where they should talk to their direct managers.” (P.10)

Similarly to the USA managers in Israel noted changes in hotel guests, for example:

“A lot of "Burgas people" are now staying in our hotels. It's a lot of what I would sometimes call "bastards", not all of them, though. We see things like violence and drugs, things that we were not used to in our hotels, and the managers grumble a bit, but I tell them, let's be happy with what we have at the moment because there are many hotels in Israel that have not opened at all.” (P.3)

Some managers expressed doomed expectations for the near future of their organization. For example:

“We all hope that around next year, let’s say, we’ll start seeing drizzles of tourism, and if it takes more time than that, then it's hard to believe we’ll survive this.” (P.13)

4.3.3. Sweden

Even though Swedish people are very low on the uncertainty avoidance scale and show less emotional distress than Israel and the USA, the participants still expressed uncertainty and dramatic adverse effects the industry suffered during this pandemic. Some examples of discussions are:

“In an almost inexplicable way, we have been down by 98% in the business, and we lost all catering revenues in 7 days’ other operations down by a minimum of -50%. It will take many years to recover from this.” (P.1)

“Tremendously. Even if we make the majority of our business during the summer season, we usually have a healthy business during the spring and early summer. That was completely halted, and we did very little if any business during this period.” (P.3)

“The feeling is that it is very uncertain what the future will bring. We’ve received some information saying that nobody knows what’s going to happen come fall. It’s looking quite uncertain at the moment, so we can’t say for sure whether it’s going to be a massive failure or not” (P.9)

On a positive side of events, the participants noticed customer support of their business and new marketing approaches:

“It’s been especially strange because the golfing industry has had such an upturn, and we’ve had a lot of visitors, especially during the springtime and in the summer …those visitors are largely within the risk group [high risk due to the age], so it’s been quite a complex puzzle” (P.6)

“We had many spontaneous visitors. We had many that supported us; at least we felt huge support fast. The first weekend after the big drop, we had many visitors, some of them were just here to grab a coffee, but still, it made us stronger.” (P.14)

“We’ve tried to develop different promotions especially now that the border towards Finland has reopened we’ve come up with different discounts for the cost of staying at a hotel within the ABC chain, and the more nights the guests stay, the discounts get bigger and bigger, so that’s what we do related to the accommodations and when it comes to food we haven’t really created any special promotions or discounts.” (P.9)

Some point out good handling of the crisis but expressed the need for better crisis plans.

“We acted quickly, and we acted firmly, but with hindsight, we could have had more plans for crisis management in place. That would have benefited us.” (P.3)

4.4. COVID-19 effect on a community

4.4.1. The United States

As the discussion progressed from personal and organizational level to a bigger picture of the communities, participants consistently expressed the pandemic's adverse effects on people in their community. Participants voiced strong emotions of anger, sadness, stress, and shock from such dramatic changes in their lives and lives in their community.

“So the effects have been large I think that alone in the fear and the anxiety and the stress. I think many of my friends…I know that they shared similar feelings concerns. The next day, or not knowing if it was the day that you that was difficult… Devastating. You know, unfortunately, have suffered great losses, not just from a financial standpoint, but also from a stability standpoint..″ (P.4)

“And so my state of mind on this is I'm angry. I'm mad, I'm disappointed. I'm sad. I'm trying to understand why this is happening and why this is happening to our community, and what we're doing to support the community. We've served you know 10s of thousands of meals during this to You know, different sectors of the community that are food impoverished.” (P.9)

Participants expressed consistently strong feelings of compassion, empathy, and need to support and give. For example, some participants said:

“We made a donation to “Feeding Tampa”, we had raised money. This was a perfect opportunity for us to help to generate meals for our theme Tampa.” (P.3)

“The biggest thing for me personally is the social connection with my friends, and they would say the same thing…it was probably the biggest impact. Most of my personal friends are older than me, and some even retired even if they weren't worrying so much about their job like I was, I am missing the social connection.” (P.14)

While people expressed a more vital need and awareness for social support, they did not indicate much government support to the community. For example:

“There was no attempt [from the government] to help certain people who might be more vulnerable or who have, you know, more needs. Not by the government, but by certain people in the neighborhood. Yes, by some of the churches, there is.” (P.11)

4.4.2. Israel

In Israel, participants expressed strong emotions of anger in people, lack of unity, change in life values and poor support of people by the government:

“A lot of difficulties, a lot of anger I see in people, a lot of anger. I do not know; maybe because of my point of view, the focus is mainly on the economic crisis. The huge distrust in the government that exists here, because of the truly scandalous treatment of this crisis, so I do not know, it's like everyone else you know, people continue to live, adapt to it, say "it's surreal, it's surreal".” (P.5)

“I think the Corona has simply woken people up, each in his/her own way. People who have realized they needed to make some financial and value changes in their lives, each in his/her own way. It has simply caused people to turn 180 degrees… that seems to be the main thing.” (P.6)

“I’ve seen some extreme events [in my life] due to my advanced age, in such periods, we felt united, and everyone helped each other. In this period of time, it's every man for himself. The discourse on social media is violent, divisive, very harsh discourse, I do not have many good things to say about us now. We’ve been exposed in all our shame. I have no other words for it. In times like this, I always said, "wow, I'm so happy to be an Israeli. Everyone helps each other" today, the feeling is that every man is for himself.” (P.2)

4.4.3. Sweden

Leaders in Sweden had mixed opinions about COVID-19 effects’ on their community. One participant indicated that people split into two camps, extremely scared or unaffected. For example:

“Extremely limited, largely normal life. I have noticed a big difference between friends; however, some hardly care at all; others are extremely scared, which you have to respect.” (P.1)

“Very negative… the streets are empty, cars everywhere on the streets, parked! No one is out, and I live in the city center, so we had noticed especially in the beginning that no one was out - now it’s better, though.” (P.3)

Some participants observed increased unity in their communities and the importance of mutual support supporting the feminine attribute of the culture (Hofstede, 1980). One of several participants said:

“We got more united but at the same time more fragile and therefore we also realized that we had to help each other… so, we got a lot more united as a community, instead of acting on an individual level. We realized that we had to help each other out and take responsibility to try and stop the spreading of the virus within the community.” (P.9)

Finally, consistent with previous sections, Swedish participants had a more optimistic and positive view of how the pandemic was managed. For example:

“When you talk to people, a lot of them are more or less unaffected by it, so if we try to look at it from a bigger perspective, then I think our local community really shouldn’t complain much about things closing down and so on… we’ve not really been affected that badly at all, and we’ve been able to mitigate the effects quite well” (P.10)

“Stockholm as a community, has been very flexible, and they were fast with reaching out with proper information, economic support, and they went out with a list with different tools and changed rules. The community went out early with a list of different ways of getting support. The support may not have helped us economically, but they made it easier for us to conduct our organization.” (P.15)

4.5. COVID-19 effect on the hospitality industry

4.5.1. The United States

The participants pointed out how devastating the pandemic was to the hospitality industry. There was a strong consensus that this is the worst experience they had in their careers and how hard it was to plan for the future. However, some pointed out that financial fitness before the pandemic and the ability to adapt, will ultimately determine who will survive this crisis. Thus, they continued showing low levels of uncertainty avoidance. For example:

“There's nothing like this; it has been the worst. It is definitely the hardest thing that I've experienced, and I think many participants have experienced it. Terrorism issues in the past, all that stuff is kind of localized, but this has been a global event. And so it's hard to, it's hard to plan fully for something like that.” (P.1)

“I can tell you that we have hotel owners that own ABC hotels, that will not be able to sustain if they don't get any sort of financial assistance, and so they may be forced to close. We have some that have a 4% occupancy. We're going forward with this, but we have some who don't have the resources to be able to do that.” (P.15)

“I just think it depends on the category. So you look at that, you know, you go back to the pizza delivery. Some segments are thriving and I think they'll continue to thrive. I think brands like ABC have done a very nice job.” (P.14)

Several participants pointed out that the industry's reputation is at risk and expressed their concerns about their future ability to hire qualified staff due to exposed vulnerability to external forces like this pandemic. Remarkably, as the discussion progressed to the bigger picture (industry), Americans started to show more signs of a masculinity side of individualism in business (action), but on the personal level, as indicated before, they showed more compassion and a more feminine dimension. For example:

“I've been in this industry over you know at 45 years. And the thing that really hurts me the most is to see, you know, the employees and our hotels, just you know basically thrown by the wayside. Say I will call you when we need you. Sorry, you know, yesterday we love you, we love you, we love you. You're the best, you're, you know, our employees are the best and all. And then you know when this happens, it's kind of, well, sorry. And that really hurts me to see that.” (P.5)

“It is getting more and more difficult. We have to let go of our staff in our hotels; some just found other jobs and do not want to come back into the industry, do not want to go through this again. It's going to be a challenge to re-staff. I think the ones who did not work through this [COVID-19]. They [future employees] still, I think, they will still see hospitality as an attractive option. I think the ones who survived this, may not.” (P.11)

4.5.2. Israel

In Israel, consistent with previous sections, participants expressed strong emotions regarding the industry's pandemic effect. Participants expressed a strong sense of foreboding and the collapse of many businesses before long. Thus, consistently showing high levels of uncertainty avoidance. Here are some of the examples:

“It's awful! I'm trying to say that for me, yes, we’ve lowered prices and did marketing… it works, and if they had not closed us back then we would’ve been able to continue working, and if the next wave is not so terrible, we are in business and growing. But I think it can cause many companies and businesses that are centered around leisure, culture, and international tourism, to collapse.” (P.8)

“It’s not at all clear to me what I can or cannot do, what is allowed, and what is forbidden. It's terribly confusing, and the more I listen, the more I get confused. That’s as far as I’m concerned anyway. There are no clear guidelines. It’s not clear to me.” (P.13)

Some reinforced the opinion that the government poorly handled the pandemic:

“I don’t know how many companies will survive. As it deepens, I don’t know how many more companies will survive this crisis because it’s a crisis it's not so much the Corona as our administration. Because with all the conflicting messages we get every day.” (P.11)

Others think that luxury tourism will be the first to return:

“…in my opinion, the first to return is luxury tourism, as richer tourists that are more well-off, have been less harmed and can afford to travel exclusively, which allows for more social distancing like private cars, hotels with separate rooms or private pool, and renting villas instead of staying in a hotel.” (P.6)

4.5.3. Sweden

In Sweden, leaders expressed distress about the industry’s vulnerability to the crisis, lack of clear messages and governmental support compared to other industries. Similarly, while Swedes are very low on uncertainty avoidance, such dramatic events as the COVID-19 pandemics created considerable concern. For example:

“Very negative! Our industry is weak… in times of crisis; it becomes very clear. Especially during this specific crisis, because people won’t go out. We can’t bring our work home; it is not easy for us to survive. I think that we will not attract young people to work within the industry or a different kind of people will start working within the industry, people with less knowledge about the industry for an example.” (P.3)

“Black. Blood bath. All travel just stopped. Everything was done from home; meetings got canceled, 250 persons or 3 persons. Everything was canceled, and we stopped traveling personally – abroad or in Sweden. It is just now that had started when the holiday season began. We start thinking: “how can we live in the future?” We can all survive a few months, but what will happen if we have to stay at home for several years?” (P.12)

“I think that the information concerning the industry has not been as clear; I wish that we could have started the process earlier; there was a lot of waiting for the restrictions. We knew that the restrictions were coming, so I wished we got more help.” (P.3)

Some expressed strong pessimism and uncertainty about the future impact:

“A lot… I believe that a lot of people’s dreams disappeared overnight. Not only for small entrepreneurs but for big chains as well, they are talking about a drop of 80%” (P.2)

“It has had a massive impact, and unfortunately, we have not seen the full extent of the crisis yet. The industry was affected by fairly low profitability even before the crisis at the same time as the actions taken by the government (restrictions) affected this industry more than any other industry.” (P.4)

Some discussed adaptation, creativity, and increased support:

“I can see more creativity now. Here in the [city], people are selling lunch, they also donate money to the hospital, to the nurses and doctors. And yes, a lot more “take away” of course… And we did a virtual nightclub! but the government has received much criticism for the support they have offered to the industry because the support does not apply to the hospitality industry in different ways.” (P.5)

4.6. COVID-19 effect on a country

4.6.1. The United States

On the country level in the USA, the principal message participants expressed was a lack of unity, confusion, and a politicized approach. Participants expressed awareness that there are fears and denial, increasing social issues like diversity, inequality, and a much greater divide than initially perceived. The USA has the highest score of Power Distance (40) among the three countries, but contrary to this, one could notice a strong rebuke of the political situation in the country.

“People are in denial, to a degree, and it also, unfortunately, depends on what political side of the fence. I think that's something that has been handled very, very poorly. Unemployment is at an all-time high. There's been a lot of inequity with regard to how funds, particularly unemployment, was dispersed. There has been complete and total disregard by the states, right now, with regard to what the CDC [Center for Disease Control] guidelines were, because if you followed the CDC guidelines. Nobody should be open.” (P.2)

“Devastating effects nationwide and it has created… an incredible fear and a lot of people and a greater divide…One that is extremely concerned for their health and you know still probably even scared to go out in public. And then the other half of the country says, it’s all a scheme, and everything's back to normal. It's ridiculous what we've done to the economy… it is now a political issue.” (P.4)

“It seems like it has all political; the disease is politicized. It's more, it seems like it's become more of a Democrat or Republican response. And it shouldn't be… it's not about one political party or the other, but it surely seems to me that it's become political…. So that's disappointing to me as an individual, it's unfortunate. I have lost trust in them [politics]. Yeah. I have, you know, because it's become so politicized and there's been so much misinformation in this information.” (P.13)

Consistent with the COVID-19 effects on the personal level, some participants indicated a change in values. Specifically, the realization that family and interpersonal bonds are far more important in people's lives than successful career or material things (more feminine). Here is one example of an insightful comment:

“I think it's really impacted society as a whole and the way that we as people have been living our lives. I have to work hard. We have to try hard. We have to be successful; we have to make more money, we have to continue bettering ourselves. And I think, you know, we've really done a 180 where we've now stepped back. Yes, we need to be able to take care of ourselves and our families. But what's more important than making money and bettering ourselves, but the families that we have and our health. Right… Our happiness, and our ability to live a quality life rather than just quantity and having material things that are supposed to bring us happiness. Peoples’ health is important…” (P.3)

One participant expressed an interesting view on perceived American freedom and wearing a mask:

“…the whole thing that our President won't put a mask on. You know, in work I think by watching the NY governor press conferences …He explained to people why they're wearing masks. They needed to do this, and it worked. I mean, people just need to be told the truth. And you know it has nothing to do with freedom …wearing a mask.” (P.12)

4.6.2. Israel

In Israel, participants thought that the country is in confusion, chaos, panic, and just like the USA, it has a heavily politicized approach to managing COVID-19. Israel has the lowest (13) power distance score and it shows in the participants’ perceptions:

“We are in quite serious confusion. The left-hand does not know what the right hand is doing; the coalition and the opposition are fighting each other much harder. I don’t know, I feel like I'm sitting on the fence, looking and waiting to see what happens next. Look, right now, I think they're getting into some kind of convergence, even the state itself. I very much hope that soon they’ll regain their composure, whoever makes the decisions, and someone will take the reins and start leading us. Because otherwise, the chaos will only get bigger, that's how I feel.” (P.13)

“The situation is a big deal. A lot of difficulties, a lot of anger I see in people, a lot of anger. I do not know; maybe because of my point of view, the focus is mainly on the economic crisis. The huge distrust in the government that exists here, because of the truly scandalous treatment of this crisis” (P.5)

“There is the hysteria that is created, I do not get into whether it is right or not. The hysteria is a bit excessive.” (P.10)

One insightful participant noticed a shift in war politics and the annexation of Gaza:

“It has completely changed the country. I think that the differences between the left and the right are slowly being blurred. Political opinions have suddenly disappeared. If I think about it for a moment, the really significant thing for me is that people are not interested in issues such as the annexation of Gaza. Security issues have all of a sudden moved to the background. The IDF's [Israel Defense Forces] primary concern has suddenly become the Corona, which is something it has begun to manage. This is the war we are dealing with, and no one is interested in the annexation issue discussed a month ago. And I think that's what the Corona has changed. Financial and job security has become paramount.” (P.6)

“The distribution [financial support] method doesn’t make sense at all. It doesn’t make sense.” (P.11)

Several participants expressed distress about the treatment of elderly citizens:

“The issue of helping the elderly, there are many elderly people who do not have anything to eat at home, they have to leave the house and have no one to bring them food, they should have had a food distribution system for the elderly.” (P.9)

4.6.3. Sweden

In Sweden, there is an awareness that poor handling of the pandemic and subsequent negative press damaged the “brand” of Sweden.

“I think Sweden confidence and our general image has been affected both nationally as well as internationally now that we’ve chosen our own path to such a great extent.” (P.10)

“Negative, unfortunately, as the image of Sweden is negative abroad. I do not think the picture is completely correct, though, but this will also become clear in maybe a year.” (P.1)

The realization that their lives are privileged relative to other countries, supporting the fact that this nation is the highest on an indulgence dimension (78):

“I mean we live in the western world, we’re very privileged, it was a huge shock for everyone and then this turned into deaths and sorrow and then it kind of went back to a different type of terror and worry across the country, Swedes are quite timid and shy, we’re still people that live with a very high standard of living, we have a lot to do, a lot to enjoy no matter where people live in Sweden, so I think that basically everything kind of turned into worry as well as hope, and then there was a very bad coverage from the media in Sweden” (P.6).

Hopes that national travel and national awareness:

“I hope that the Swedish people will start traveling more in-between in our country and not only around the world. We are curious in Sweden, but hopefully, we can be more curious about what we got in our country instead. That’s my hopes… They have given the Swedish people one’s own responsibility. I mean we have not that many restrictions. The biggest impact was the restriction of that you were not allowed to meet in bigger groups.” (P.2)

Many participants expressed a concern about the poor treatment of the elderly:

“… but we did fail in our care for the elderly. I am not thinking about the number of deaths; I am thinking about the number of people who died alone! I hope that we won’t forget that work category with assistant nurses, and we have to give them respect….” (P.14)

4.7. COVID-19 effect on the world

Across all three countries in this study, participants unanimously pointed out a lack of unity to fight pandemic worldwide. Participants perceived a strong lack of communication among countries and no collaboration but rather competition for a vaccine. Sadly, participants expressed little trust and a lack of knowledge about the World Health Organization (WHO). It felt like participants did not watch as closely global events relative to the country (something closer to them) during interviews. However, if asked after a short consideration, people perceived the world in relative terms compared to other countries. Finally, participants hoped that globalization would be reduced, and people would appreciate their own countries.

4.7.1. The United States

In the USA specifically, participants indicated that there would be a reduction in international travel, and some mentioned disagreement with the USA withdrawal from WHO.

Finally, even when prompted to talk about the world, the participants’ responses were still mainly country-focused, not global-focused.

“It's a pandemic. It pretty much touched everything in the world. The world economy is going to struggle to recover, just like the U.S. economy is going to struggle to recover. I just think it's going to take a very, very long time.” (P.2)

“I don't think there's going to be good sharing and communication of that information between the countries. I don't feel like we are united. As a world as successfully as we could be. I think there's infighting. And people think you know egos competition.” (P.3)

“Whether that's work travel or whether that's pleasure travel. I don't think there's going to be a significant population that will say I need to get on the plane to go for a vacation abroad…we just need the comfort level in the vaccine.” (P.15)

“…we're talking about pulling out of the World Health Organization. I think that's absurd.” (P.12)

4.7.2. Israel

In Israel, when asked about the global effects of COVID-19, participants were more likely to compare to Europe and express frustration that Israel's response to the pandemic was mismanaged.

“Every country takes care of itself. So, we’ve seen very strongly this phenomenon of state centralization. It will be interesting to see how the priorities in the world change once the world starts to recover.” (P.12)

“I think what will happen the day after, unfortunately, is that there will be a reduction in globalization, I mean… we have traveled too much for every little thing, I am in the field of tourism, and I wish it comes back, but I think we will see a reduction.” (P.7)

“At first, I thought the Corona was fiction not because of the trade wars between the U.S. and China. I said that maybe there is something to it, but they’re probably exaggerating. The world has become colder and more alienated. The world is divided in two before and after the Corona. Historically, once in a century, there is an epidemic, so we are part of history. It will have heavy consequences because even when things start moving, they will not move at the same rate because people have no money.” (P.10)

“I know there were a lot of casualties in the U.S., and I look more on the micro-level. I compare it to Europe, to France in particular, and Sweden. Why Sweden? Because Sweden didn’t do a thing, didn’t close…They said: you’re sick, stay home. They took care of them. In the end, they didn’t have too many deaths. Relative to Israel, that was correct, but their lives didn’t change. People continued to work, were not harmed financially. This is the only country that decided not to close. And today, six months in retrospect, the situation there is not worse than in other countries.” (P11)

4.7.3. Sweden

In Sweden, participants talked about the need for sustainability and hoped that the COVID19 pandemic would create a push toward that. They have shown a bit more macro (global) awareness rather than country centric.

“My hopes are that we will start a bigger debate about sustainability and climate, and my beliefs are that the subject will take a greater place.” (P.2)

“It's the biggest crisis we've had in my lifetime, and we do not yet know where it will end. Enormous values are lost, many people have become ill or even died, the economy stalls, many problems bubble to the surface, such as from neighbors to tensions between countries. Positive effects are increased collaborations, increased creativity, and some "cleansing" of finances at certain levels. WHO has not taken a leading role in this and has not been clear. In my world, this organization feels like a very sleepy organization that suddenly had a lot to do. There are major improvement measures to be made here. Although I do not like the United States withdrawing, they, like others, should increase their demands on the WHO “(P.1)

“Cooperation and communication. One part has to take the lead in a crisis like this, and that could well be WHO. Now it seems, every country has fended for itself. This goes for research, results, development of a cure, and a vaccine. Pooled resources are and will be the key.” (P.4)

“An awakening on a personal level but also on a much higher level, if it turns out that the virus comes from animal breeding, then the awakening has to concern that matter also, we need to make sure that we act in a more responsible way all over the planet. An awakening.” (P.9)

“I believe that we will travel less, and we will become more nationalistic in our mindset. We will benefit from Sweden; we will start to buy more things from Sweden in Sweden. We will also become suspicious against other countries, and at the same time, someone will start to get suspicious against Swedish authorities and the government. What collaboration? Every country has been making their decisions. The biggest problem is the structure of healthcare, and that has caused many deaths. And the elder care, they did not receive the kind of help or support that they needed, and I guess that the problem not only exists in Sweden.” (P.16)

5. Conclusion

The COVID-19 pandemic has dramatically changed the hospitality industry, and understanding its consequences is essential for its survival (Kaushal & Strivastava, 2020). The SST (Luhmann et al., 2013) and Hofstede (1980) cultural differences models were used to evaluate the perceived impacts of COVID-19 on the hospitality industries in the USA, Israel, and Sweden. Using the SST enabled us to analyze the interrelationships between the different parts of society and analyze their overall impact. As expected, we found that the SST holds true in this pandemic, and the individual effects of participants reverberate through their organizations, industry, communities, countries, and the world.

The adverse impacts of the COVID-19 pandemic have been felt across countries on a large scale, shaking political systems and responses. The pandemic’s effects on travel adversely affected tourism and, subsequently, the entire hospitality industry. Mixed political responses in different countries have added to the hardships faced by the hospitality industry, communities, and individuals. Adversity in the industry has affected peoples’ organizational perceptions and reverberated into their individual lives.

Cultural differences were reflected in the participants’ perceptions of events. If a dramatic enough event (such as the COVID-19 pandemic) is introduced into peoples’ lives, their values start to deviate, at least in the short term. For example, the strongly individualistic and masculine American society has rediscovered compassion and empathy toward coworkers, profound connection with family and friends, and focus on emotional values, causing it to become less individualistic, materialistic, and achievement-oriented, and more collectivistic. Sweden, which scored very low on uncertainty avoidance and high on indulgence, expressed fear and strong uncertainty about the hospitality industry’s future, which reverberated into personal and professional lives. Moreover, damage to the country’s image due to negative publicity affected peoples’ personal feelings about their country. Finally, Israel was very consistent with Hofstede’s cultural scores. Israel’s indulgence score is not known, but based on the interviews, it can be perceived as high and has changed with the realization of the need for financial security at the business level during adverse events. Finally, the image of the hospitality industry as a workplace was affected negatively, especially in the US, thus creating concerns about its ability to hire skilled workers in the future.

6. Theoretical contribution

This is the first study that we know of that combines SST and Hofstede’s cultural model and that applied this framework to evaluating pandemic events in the hospitality industry. This study provides insight for researchers about dynamic events that affect industries, individuals, organizations, communities, countries, and the world. This study lends itself to a practice-centric approach toward conceptualization when approaching research on the effect of the pandemic on the hospitality industry and uses a multicultural approach. Moreover, it provides a beginning for understanding how to apply SST to hospitality industry research and cross-cultural studies, which, to our knowledge, had not yet been applied.

7. Managerial implications

The findings of this study have several implications for management practice and open a new depth of understanding for leaders in the hospitality industry across the USA, Israel, and Sweden. COVID-19 is a novel, adverse global event that has affected the hospitality industry on a global scale. Awareness of how the pandemic has affected other leaders and employees, together with cultural dynamics on the individual, organizational, industry, and national levels, can help produce future strategies to mitigate the effects of the pandemic on employees and organizations. Some perceived future trends in the industry from experienced top participants can help managers plan for future events, perhaps adjust their expectations, and use some innovative ideas (technology) in their businesses.

8. Limitations

This study is not without limitations. First, as a qualitative study it lacks the generalizability of quantitative research. However, the depth of qualitative research is invaluable for formulating quantitative research questions for future studies. Second, the study (across all three countries) is male dominant. However, the “Woman in the Workplace 2020″ research found that in the past five years in corporate America, women in senior manager or director positions represent 33% of the total population and C-suite positions only 21% relative to their male counterparts (Huang et al., 2020). In Sweden, only 13% of women are in corporate leadership (Heguedus, 2012), and 32.2% of women in Israel are in managerial positions (IMFA, 2016). Thus, women are mainly underrepresented in high leadership positions, which is reflected in our sample. Finally, this study was conducted during the early stages of the COVID-19 pandemic, representing an insight into the pandemic’s early impact.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to express our sincere gratitude to all the respondents who participated confidentially in this research study. Without their open and sincere answers in this study would not have been possible. The authors are also grateful for the financial support provided by Jonas Nordén’s memorial fund.

Appendix

COVID-19 Social System Theory Interview Guide

Individual effects

Main question 1:

-

•

How did the events of COVID-19 affect you on a personal level?

Main question 2:

-

•

How are you coping with events of COVID 19?

-

•

What do you think you should do to cope with or mitigate these effects?

Guiding questions (Probes):

(in the areas of emotional health, physical well-being, economic security, social relations)

-

1.

What are your and your family's emotional states?

-

2.

What is your and your family's physical well-being effect?

-

3.

What do you feel towards your employees?

-

4.

How do you feel about your own job security?

-

5.

What steps for your career security are you planning to take?

-

6.

What have you personally learned from this experience?

Organizational effects

Main question 1:

-

•

How did COVID-19 affect your organization?

Main questions 2:

-

•

What steps were taken by your organization to mitigate the effects of COVID-19?

-

•

What is in your opinion should be done to mitigate the effects of COVID-19?

-

•

What steps should be taken in the future to mitigate the effects of similar events

Guiding questions (Probes):

(in the areas of shutting down the organization, terminating or furloughing employees, reducing prices, increasing marketing efforts, heavy losses, fear of bankruptcy, demoralization)

-

1.

Did your organization cease to operate?

-

2.

Have employees been laid off or furloughed?

-

3.

Has your organization continued to operate but in a partial manner?

-

4.

Has your organization adopted new ways of doing business (i.e. new products or services)?

-

5.

Has your organization increased its marketing efforts?

-

6.

Has your organization’s financial losses so large that it may be bankrupt?

-

7.

Are the employees anxious and demoralized?

-

8.

What steps should be taken to mitigate the above effects in your organization?

-

9.

What should be done to prevent these or similar effects in the future?

Community effects

Main question 1:

-

•

How did the events of COVID-19 affect your geographical and/or social community?

Main question 2:

-

•

What steps were taken by your community to mitigate the effects of COVID-19?

-

•

What do you think should be done to mitigate the effects of COVID-19 on your community? What steps should be taken to mitigate the effects of similar events in the future?

Guiding questions (Probes):

(in the areas of information, physical, economic, social and/or spiritual support)

-

1.

Did authorities provide proper information?

-

2.

Did the community and its leadership provide proper help/support in the areas of physical, economic, social, or spiritual?

-

3.

What steps should be taken by the community to mitigate the above effects?

-

4.

What should be done by the community to prevent these or similar effects in the future?

Industry effects

Main question 1:

-

•

How did the events of COVID-19 affect the industry?

Main question 2:

-

•

What steps were taken by the industry and its leadership to mitigate the effects of COVID-19?

-

•

What do you think should be done by the industry and its leadership to mitigate the effects of COVID-19?

-

•

What steps should be taken by the industry and its leadership, in the future, to prevent or mitigate the effects of similar events?

Guiding questions (Probes):

(in the areas of crisis planning, lobbying, disaster insurance plans, state and federal economic assistance)

-

1.

What if any industry crisis plans existed at the time COVID-19 erupted?

-

2.

How successful was the industry in lobbying for financial assistance from the federal and state governments?

-

3.

What steps should be taken by the industry and its leadership to mitigate the above effects?

-

4.

What should be done by the industry and its leadership to prevent these or similar effects in the future?

Country effects

Main question:

-

•

How did COVID-19 affect our country?

Main question 2:

-

•

What steps were taken by the leadership of our country (at the federal level) to mitigate the effects of COVID-19?

-

•

What do you think should be done by the leadership of our country to mitigate the effects of COVID-19?

-

•

What steps should be taken by the leadership of our country in the future to prevent or mitigate the effects of similar events

Guiding questions (Probes):

(in the areas of crisis/disaster planning, new legislation, disaster insurance)

-

1.

Was the country prepared for a disaster of this magnitude?

-

2.

Was the current economic assistance provided by the federal government sufficient?

-

3.

Was the current economic assistance provided by the federal government fair?

-

4.

Is the country doing all it can to develop a cure and/or a vaccine?

-

5.

What steps should be taken by the leadership of our country to mitigate the above effects?

-

6.

What should be done by the leadership of our country to prevent or mitigate the effects or similar events in the future.

World effects

Main question:

-

•

How did COVID-19 affect the entire world?

Main question 2:

-

•

What steps were taken by the World Health Organization (WHO) and its leadership to mitigate the effects of COVID-19?

-

•

What do you think should be done by the WHO and its leadership to mitigate the effects of COVID-19?

-

•

What steps should be taken by the WHO and its leadership in the future to prevent or mitigate the effects of similar events?

Guiding questions (Probes):

(in the area of international cooperation)

-

1.

Did countries cooperate with each other to find a cure or vaccine for COVID-19?

-

2.

Did countries learn from each other's experiences how to mitigate the effect of COVID-19?

-

3.

Should countries work together to cooperate in finding a cure and/or vaccine?

-

4.

What steps should be taken by the WHO to find a cure and/or vaccine?

-

5.

What should be done by the WHO to prevent or mitigate the effects or similar events in the future.

General Information (Organization)

-

1.

Employer (kept confidential this is for the record)

-

2.

Company industry:

-

3.

Number of employee’s total

General Information (Demographics)

-

1.

Gender

-

2.

Education

-

3.

Income

-

4.

Marital status

-

5.

Country

-

6.

Title

References

- Ahlawat R. Culture and HRM-application of Hofstede’s cultural dimensions in hospitality HRM. Int. J. Adv. Res. Manage. Soc. Sci. 2016;5(12):130–139. [Google Scholar]

- American Hotel and Lodging Association (AHLA) AHLA; 2020. AHLA COVID-19 Impact on the hotel industry.https://www.ahla.com/covid-19s-impact-hotel-industry [Google Scholar]

- Andrews J. Food Safety News; 2013. Jack in the Box and the Decline of E. coli.https://www.foodsafetynews.com/2013/02/jack-in-the-box-and-the-decline-of-e-coli/ Retrieved from. [Google Scholar]

- Bali S., Stewart K.A., Pate M.A. Long shadow of fear in an epidemic: fearonomic effects of Ebola on the private sector in Nigeria. BMJ Glob. Health. 2016;1(3):1–14. doi: 10.1136/bmjgh-2016-000111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chien G., Law R. The impact of the severe acute respiratory syndrome on hotels: a case study of Hong Kong. Hosp. Manage. 2003;22:327–332. doi: 10.1016/S0278-4319(03)00041-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Creswell J.W., Poth C. 4th edition. 2018. Qualitative Inquiry and Research Design. Los Angeles. [Google Scholar]

- Creswell John W., Poth Cheryl N. SAGE Publications. Kindle Edition; 2018. Qualitative Inquiry and Research Design. [Google Scholar]

- Crotts J.C., Erdmann R. Does national culture influence consumers’ evaluation of travel services? A test of Hofstede’s model of cross-cultural differences. Manag. Serv. Q. Int. J. 2000;10(6):410–419. [Google Scholar]

- Crotts J.C., Pizam A. The effect of national culture on consumers’ evaluation of travel services. Tour. Cult. Commun. 2003;4(1):17–28. [Google Scholar]

- Dossa P.A. Toward social system theory: implications for older people with developmental disabilities and service delivery. Int. J. Aging Hum. Dev. 1990;30(4):303–319. doi: 10.2190/T25G-CCVK-4C15-MM9T. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duffin E. Statista; 2020, Feb. 14. United States - Distribution of Gross Domestic Product (GDP) Across Economic Sectors 2017.http://www.statista.com/statistics/270001/distribution-ofgross-domestic-product-gdp-across-economic-sectors-in-the-us/ [Google Scholar]

- Dukes S. Phenomenological methodology in the human sciences. J. Relig. Health. 1984;23(3):197–203. doi: 10.1007/BF00990785. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elflein . Statista; 2020. Confirmed Cases and Deaths of Major Virus Outbreaks Worldwide in the Last 50 Years As of 2020.https://www.statista.com/statistics/1095192/worldwideinfections-and-deaths-of-major-virus-outbreaks-in-the-last-50-years/ Aug. 24. [Google Scholar]

- Fernandes N. 2020. Economic Effects of Coronavirus Outbreak (Covid-19) on the World Economy. Apr. 13. Retrieved from https://edisciplinas.usp.br/pluginfile.php/5662406/mod_resource/content/1/FERNANDES_Economic%20Effects%20of%20Coronavirus%20Outbreak%20%28COVID19%29%20on%20the%20World%20Economy.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- Gitelson R., Kerstetter D. The influence of friends and relatives in travel decisionmaking. J. Travel Tour. Mark. 1995;3(3) 59-56. [Google Scholar]

- Given L.M. SAGE; 2008. The SAGE Encyclopedia of Qualitative Research Methods. [Google Scholar]

- Heguedus N. Quartz; 2012. In Sweden, a Woman Makeup 45% of Parliament but Only 13% of Corporate Leadership.https://qz.com/37036/in-sweden-women-make-up-45-of-parliament-butonly-13-of-corporate-leadership/ [Google Scholar]

- Henderson J.C. Corporate social responsibility and tourism: hotel companies in Phuket, Thailand, after the Indian Ocean tsunami. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2007;26(1):228–239. [Google Scholar]

- Henderson J., Ng A. Responding to crisis: severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS) and hotels in Singapore. Int. J. Tour. Res. 2004;6:411–419. [Google Scholar]

- Hofstede G. SAGE; 1980. Culture’s Consequences: International Differences in Work-related Values.https://www.statista.com/statistics/375611/sweden-gdp-distribution-across-economic-sectors/ [Google Scholar]

- Hofstede G., Hofstede G.J., Minicov M. 3rd ed. McGraw Hill; New York: London: 2010. Culture and Organization: Software of the Mind: Intercultural Cooperation and the Importance for Survival. [Google Scholar]

- Hofstede Insights . Hofstede Insights; 2020. Country Comparison.https://www.hofstedeinsights.com/country-comparison/israel,sweden,the-usa/ Aug. 12. [Google Scholar]