Abstract

Intestinal epithelial cells exist in physiological hypoxia, leading to hypoxia-inducible factor (HIF) activation and supporting barrier function and cell metabolism of the intestinal epithelium. In contrast, pathological hypoxia is a common feature of some chronic disorders, including inflammatory bowel disease (IBD). This work was aimed at studying HIF-associated changes in the intestinal epithelium in IBD. In the first step, a list of genes responding to chemical activation of hypoxia was obtained in an in vitro intestinal cell model with RNA sequencing. Cobalt (II) chloride and oxyquinoline treatment of both undifferentiated and differentiated Caco-2 cells activate the HIF-signaling pathway according to gene set enrichment analysis. The core gene set responding to chemical hypoxia stimulation in the intestinal model included 115 upregulated and 69 downregulated genes. Of this set, protein product was detected for 32 genes, and fold changes in proteome and RNA sequencing significantly correlate. Analysis of publicly available RNA sequencing set of the intestinal epithelial cells of patients with IBD confirmed HIF-1 signaling pathway activation in sigmoid colon of patients with ulcerative colitis and terminal ileum of patients with Crohn’s disease. Of the core gene set from the gut hypoxia model, expression activation of ITGA5 and PLAUR genes encoding integrin α5 and urokinase-type plasminogen activator receptor (uPAR) was detected in IBD specimens. The interaction of these molecules can activate cell migration and regenerative processes in the epithelium. Transcription factor analysis with the previously developed miRGTF tool revealed the possible role of HIF1A and NFATC1 in the regulation of ITGA5 and PLAUR gene expression. Detected genes can serve as markers of IBD progression and intestinal hypoxia.

Keywords: intestinal bowel disease, hypoxia, cobalt, hydroxyquinolines, caco-2 cells, urokinase-type plasminogen activator receptor, disease markers, transcriptomics

1 Introduction

Some pathologic conditions, such as inflammatory bowel disease (IBD), including ulcerative colitis (UC) and Crohn’s disease (CD), are associated with pathological hypoxia (Taylor, 2018). UC affects only the colon, while CD affects both the small and large intestines. The exact pathogenesis of IBD is still unclear, but it is a complex pathology involving genetics, environment, microbiome, and immunome (Borg-Bartolo et al., 2020). Hypoxia leading to hypoxia-inducible factor (HIF)-signaling pathway activation is a common feature of inflammatory diseases, including IBD (Kerber et al., 2020). HIF-1α is protective in IBD models (Kim et al., 2021), and HIF-2α is essential in maintaining the immune response and regenerative capacity of the intestinal epithelium in IBD (Ramakrishnan and Shah, 2016). At the same time, HIF-2α but not HIF-1α constitutive activation leads to IBD development or exacerbation in colitis models (Xue et al., 2013; Solanki et al., 2019). HIF-1α activation in myeloid cells aggravates, and HIF-2α activation ameliorated IBD in murine models (Kim et al., 2018; Kerber et al., 2020). These results emphasize that the degree of hypoxia and HIF activation can lead to both adaptation and damage to the intestinal epithelium.

The human small intestine consists of crypts and villi, and the colon consists of crypts only. Crypts are invaginations aligned by intestinal stem cells, early progenitor transit-amplifying cells, and differentiating cells (Rangel-Huerta and Maldonado, 2017). The colon surface and small intestine villi are covered by specialized epithelium with differentiated cells, such as enterocytes and goblet cells (Singhal and Shah, 2020). The main enterocyte functions are to create a barrier between the external and internal environment and to provide regulated transport of substances between these environments (Schoultz and Keita, 2020). There is a unique oxygen gradient from the crypt to the intestinal lumen. Electron paramagnetic resonance oximetry revealed partial oxygen pressure (pO2) gradient from 59 mm Hg (8%) in the small intestine wall to 22 mm Hg (3%) at the villus apex and <10 mm Hg (2%) in the small intestinal lumen, whereas colon pO2 is 5–10 mm Hg near the crypt-lumen interface, and 11 (∼2%) and 3 mm Hg (∼0.4%) in the lumen of ascending and sigmoid colon, respectively (Singhal and Shah, 2020). Thus, intestinal cells exist under conditions ranging from mild to pronounced hypoxia, which leads to HIF stabilization and adaptation to hypoxic conditions (Pral et al., 2021). HIF stabilization in physiological hypoxia supports cell metabolism and barrier function of the intestinal epithelium (Glover et al., 2016).

Modeling of the human intestinal epithelium is possible with human colon adenocarcinoma cell line Caco-2 (Nikulin et al., 2018b). Undifferentiated Caco-2 (uCaco-2) cells actively proliferate, resembling intestinal stem cells, but contact inhibition stimulates differentiation and suppresses proliferation. Differentiated Caco-2 (dCaco-2) cells acquire enterocyte properties, such as cylindrical cell shape, formation of intercellular junctions and microvilli, specific enzyme and marker expression (Ding et al., 2021). Extracellular matrix can support cell attachment, proliferation, and differentiation (Mutsenko et al., 2017), and use of laminins specific for the intestinal basal membrane can bring the gut model properties closer to conditions in vivo (Nikulin et al., 2018a, 2019). Microfluidic devices with a culture medium flow that simulates blood flow create even more physiological conditions for the cell model (Samatov et al., 2016, 2017; Sakharov et al., 2019). Caco-2 intestinal model is suitable to study hypoxia effects (Maltseva et al., 2020; Nersisyan et al., 2021a). Small molecules can fit in the enzyme active center inhibiting its activity (Smirnov et al., 2011; Ivanenkov et al., 2015). Oxyquinoline derivatives can directly block the prolyl hydroxylase active center leading to HIF stabilization (Knyazev et al., 2019a; 2019b). Cobalt (II) chloride (CoCl2) also serves as a chemical hypoxia inductor by replacing Fe2+ ions in the prolyl hydroxylase active center, induction of ascorbate oxidation, and other potential mechanisms (Muñoz-Sánchez and Chánez-Cárdenas, 2019). Previously, we showed that chemical hypoxia models, induced by CoCl2 and OD, may serve as models of severe and mild hypoxia, respectively (Knyazev et al., 2021; Knyazev and Paul, 2021).

This work aimed to study the effects of chemical HIF activation on dCaco-2 and uCaco-2 cells as the intestinal model and compare observed changes with patterns in the intestinal epithelium of IBD patients to find hypoxic markers, relevant for IBD.

2 Materials and Methods

2.1 Cell Cultures and Treatments

Caco-2 cells were received from the Russian Vertebrate Cell Culture Collection (Institute of Cytology, Russian Academy of Sciences, St. Petersburg, Russia). The cells were incubated in Gibco minimal essential medium with L-glutamine, 20% Gibco FBS One Shot, and 1% Gibco Pen Strep (Thermo Fisher Scientific, United States ). The cells were seeded in the 6-well culture plates (TPP Techno Plastic Products AG, Germany) at a seeding density of 0.3 x 106 cells per well and cultivated for 21 days to achieve cell differentiation, as previously published (Nersisyan et al., 2021a). On the last week of differentiation new portion of cells was seeded in the 6-well culture plates at the same seeding density and cultivated to 80% of confluence. The cell culture medium of differentiated and undifferentiated Caco-2 was replaced with either medium with 300 μM CoCl2, medium with 5 μM OD 4896–3,212 (ChemDiv Research Institute, Khimki, Russia), or fresh medium. OD stock solution was diluted in DMSO at 10 mM, so 0.5% DMSO was also added to CoCl2 and control medium, and cells were incubated 24 h before lysis for RNA and protein extraction.

2.2 RNA Extraction, Library Preparation and Sequencing

Cells were lysed in 700 μL of QIAzol Lysis Reagent (Qiagen, Hilden, Germany) with subsequent RNA extraction with miRNeasy Mini Kit (Qiagen) according to the manufacturer protocol, including on-column treatment with RNase-Free DNase Set (Qiagen). RNA was extracted in 30 μL of RNase-free water. RNA concentration was measured with NanoDrop 2000 Spectrophotometer (Thermo Fisher Scientific). A260/A280 and A260/A230 ratios were more than 2.0, and RNA Integrity Number (RIN) according to 2,100 Bioanalyzer with Agilent RNA 6000 Pico Kit (Agilent Technologies, Santa Clara, CA, United States ) was not less than 9.7 for all RNA samples.

Libraries for mRNA sequencing were prepared with TruSeq Stranded mRNA Library Prep (Illumina, San Diego, CA, United States) with 1 μg total RNA in three biological replicates for each condition. Library quality check was provided with Agilent High Sensitivity DNA Kit (Agilent Technologies). Sequencing with NextSeq 550 (Illumina) generated single-end 75-nucleotide reads. The sequencing data is available online in the Gene Expression Omnibus (GEO) with the accession numbers GSE186295 and GSE158632.

2.3 Sequencing Data Processing

The FASTQ file quality was assessed with FastQC v0.11.9 (Babraham Bioinformatics, Cambridge, United Kingdom). After adapter trimming with cutadapt v2.10 (Martin, 2011) reads were mapped on the reference human genome (GENCODE GRCh38.p13) with STAR v2.7.5b (Dobin et al., 2013). The count matrix was generated with GENCODE genome annotation (release 34) (Frankish et al., 2019). FASTQ files for intestinal cells in IBD and healthy control were downloaded from the online repository (E-MTAB-5464) (Howell et al., 2018). Differential expression analysis was performed with DESeq2 v1.28.1 (Love et al., 2014); false discovery rates (FDRs) were calculated by the Benjamini–Hochberg procedure. Differences were considered significant at FDR <0.05 and log fold changes modulo >1.0.

2.4 Gene Set Enrichment Analysis and Transcription Factors Search

Gene set processing and Venn diagram creation was made with jvenn tool (Bardou et al., 2014). Gene set enrichment analysis was performed using Fgsea package version 1.16.0 (Korotkevich et al., 2016). Gene sets were downloaded from Gene Set Enrichment Analysis (GSEA) site (http://www.gsea-msigdb.org), from The Molecular Signatures database (MSigDB 7.4) to assess the activity of hallmark gene sets (Subramanian et al., 2005; Liberzon et al., 2015). The Database for Annotation, Visualization and Integrated Discovery (DAVID) v6.8 (Huang et al., 2009) was used to reveal Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes (KEGG) pathways activity (Kanehisa et al., 2021).

The previously developed miRGTF-net tool was used to find transcription factors regulating genes of interest (Nersisyan et al., 2021b). The publicly available datasets of RNA sequencing data for colorectal cancer were received from The Cancer Genome Atlas Program Colon Adenocarcinoma (TCGA-COAD) cohort (Cancer Genome Atlas Network, 2012).

2.5 Proteome

Differentiated Caco-2 cells after 24 h incubation with CoCl2 and control Caco-2 cells were lysed with ice-cold lysis buffer with 4% SDS and 0.1 M DTT in 0.1 M Tris-HCl (pH 7.6) and briefly sonicated on the ice with CPX 130 Ultrasonic Processor, 130 W, 20 kHz (Cole-Parmer Instruments, Vernon Hills, IL, United States ), 30 s in pulse regimen and 30% amplitude. Total protein concentration was measured with Pierce BCA Protein Assay Kit - Reducing Agent Compatible (Thermo Fisher Scientific). Tripsinized protein samples were analyzed with the Q Exactive HF hybrid quadrupole-orbitrap mass spectrometer with nano-electrospray ionization (nESI) source operated in the positive ionization mode (Thermo Fisher Scientific), the emitter voltage of 2.1 kV, the capillary temperature of 240 C. Progenesis IQ software (Waters Corporation, Milford, MA, United States ) was used to quantify protein levels with subsequent analysis with the SearchGUI v.3.3.1 software and the HumanDB database (UniProt Release 2018_05). Differential expression was assessed with the iBAQ algorithm using MaxQuant 1.6 software (Max Planck Institute of Biochemistry, Martinsried, Germany). Differences were considered significant at a fold change >2.0 and Student’s t-test p < 0.05.

3 Results

3.1 General Pattern of Expression Changes in Response to Cobalt (II) Chloride and Oxyquinoline Derivative Exposure in Differentiated and Undifferentiated Caco-2 Cells

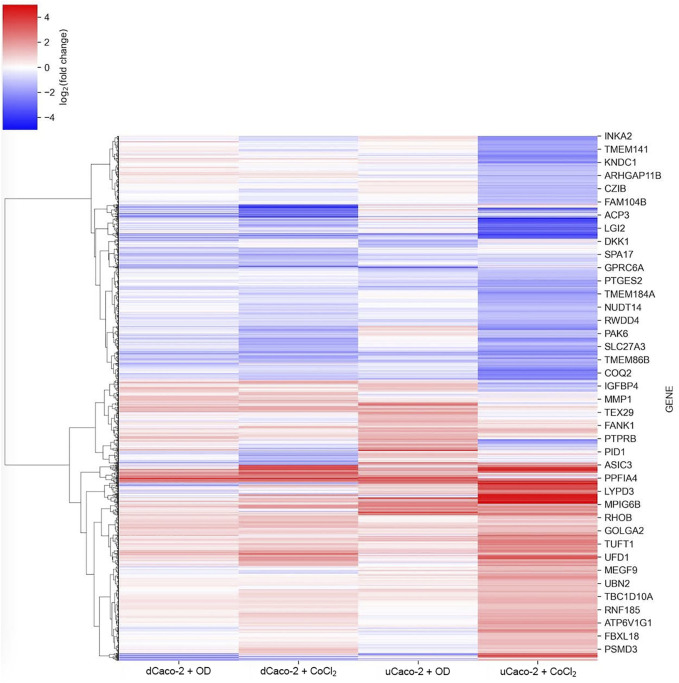

There is no generally accepted list of genes that should respond to HIF activation in all cells and tissues, although some studies show common patterns (Benita et al., 2009). We performed an analysis of gene expression changes in dCaco-2 and uCaco-2 upon exposure to OD and CoCl2 as known activators of the HIF-signaling pathway. The total number of genes whose expression changed significantly in at least one experimental group was 7,180. The pattern of expression changes was similar in all treatments with a notably stronger effect of CoCl2 in both cell types, the most pronounced in uCaco-2 (Figure 1 and Supplementary Table S1).

FIGURE 1.

mRNA expression changes for differentiated Caco-2 (dCaco-2) and undifferentiated Caco-2 (uCaco-2) upon cobalt (II) chloride (CoCl2) and oxyquinoline derivative (OD) treatment. The heatmap includes genes with differential expression in at least one combination of cell line and treatment.

We performed gene set enrichment analysis to assess the activity of pathways and biological processes in Caco-2 cells upon HIF-pathway activation. We used hallmark gene sets from The MSigDB. Both OD and CoCl2 have activated HALLMARK_HYPOXIA Pathway in uCaco-2 and dCaco-2, confirming the activation of the HIF signaling pathway. Also, in all experimental settings except uCaco-2 OD stimulation, there was activation of the following pathways: HALLMARK_TNFA_SIGNALING_VIA_NFKB, HALLMARK_P53_PATHWAY, and HALLMARK_MTORC1_SIGNALING. It appears that activation of genes regulated by NF-kB in response to tumor necrosis factor α (TNFα) may indicate intersections between hypoxic and inflammatory effects of chemical HIF activators. CoCl2 and OD may activate apoptotic processes through genes involved in the p53 pathway and proliferation through genes upregulated through activation of the mTORC1 complex.

CoCl2 specifically activates the following pathways in both uCaco-2 and dCaco-2: HALLMARK_COMPLEMENT, HALLMARK_REACTIVE_OXYGEN_SPECIES_PATHWAY, HALLMARK_INFLAMMATORY_RESPONSE. It indicates activation of inflammatory response in Caco-2 cells, and reactive oxygen species can be generated in cells upon CoCl2 stimulation as a side effect apart from HIF stabilization (Muñoz-Sánchez and Chánez-Cárdenas, 2019).

3.2 Core Gene Set Responding to Chemical Hypoxia Simulation in Caco-2 Cells

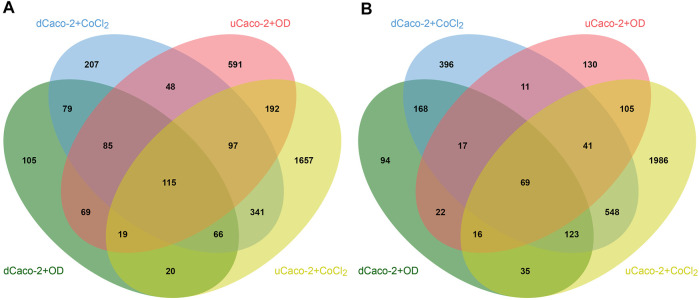

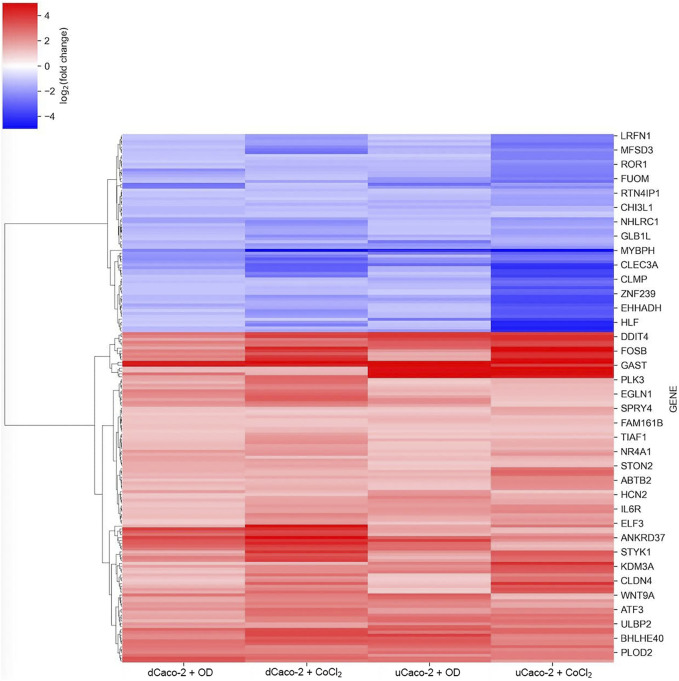

The core gene set with the same expression change direction both for uCaco-2 and dCaco-2 upon CoCl2 and OD treatment included 184 genes, 115 upregulated and 69 downregulated (Figure 2 and Supplementary Table S2). As for the complete list of differentially expressed genes, more pronounced expression changes were observed upon CoCl2 exposure, especially in uCaco-2 (Figure 3).

FIGURE 2.

Intersections of differentially expressed genes in differentiated Caco-2 (dCaco-2) and undifferentiated Caco-2 (uCaco-2) upon cobalt (II) chloride (CoCl2) and oxyquinoline derivative (OD) treatment. (A)—upregulated genes. (B)—downregulated genes.

FIGURE 3.

mRNA expression changes for the core gene set reacting to chemical hypoxia simulation in differentiated Caco-2 (dCaco-2) and undifferentiated Caco-2 (uCaco-2) upon cobalt (II) chloride (CoCl2) and oxyquinoline derivative (OD) treatment.

Enrichment Analysis of differentially expressed genes in both types of cells and both treatments using DAVID v6.8 revealed significant activation of the following KEGG pathways: Glycolysis/Gluconeogenesis (hsa00010), HIF-1 signaling pathway (hsa04066), Fructose and mannose metabolism (hsa00051), and Carbon metabolism (hsa01200), which is evidence in favor of an activation of the hypoxia signaling pathway and corresponding metabolic changes. This gene set was used as a possible HIF-associated pattern in intestinal cells exposed to hypoxia.

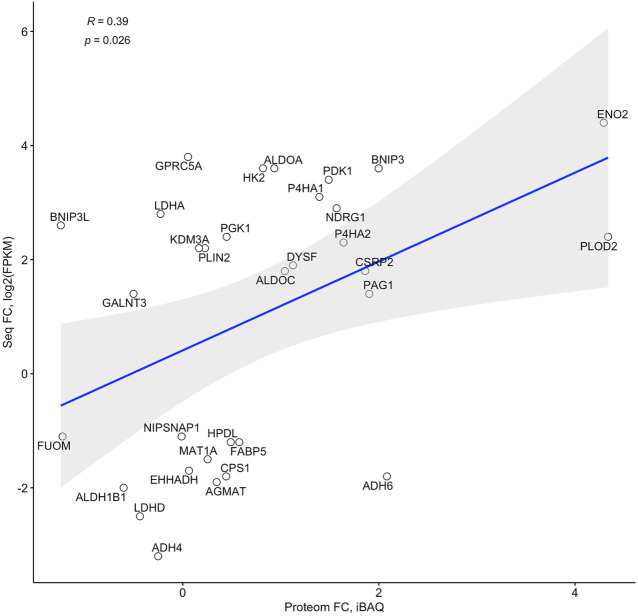

Proteomic profiling of dCaco-2 upon CoCl2 stimulation and in control conditions revealed 3,361 proteins, of them 209 were upregulated and 28 downregulated significantly (p < 0.05) after CoCl2 stimulation. Gene set enrichment analysis for these proteins have not revealed significantly activated pathways at FDR<0.05, but p < 0.05 without Benjamini-Hochberg adjustment was revealed for Ribosome (hsa03010) and Endocytosis (hsa04144) KEGG pathways, suggesting an effect of HIF activation on protein synthesis and nutrient transport. Of the 184 genes on the list of HIF-associated genes, a protein product was detected for 32 genes. Analysis of fold changes in proteomic and sequencing data confirmed a significant correlation between these indicators (Figure 4). Next, we compared this gene list with specific expression changes in the intestinal epithelium of IBD patients.

FIGURE 4.

Correlation of fold changes in the RNA sequencing (Seq FC) and proteome (Proteom FC) data in differentiated Caco-2 (dCaco-2) upon cobalt (II) chloride (CoCl2) treatment.

3.3 Potential HIF-Associated Changes in Intestinal Epithelium of Patients With Inflammatory Bowel Disease

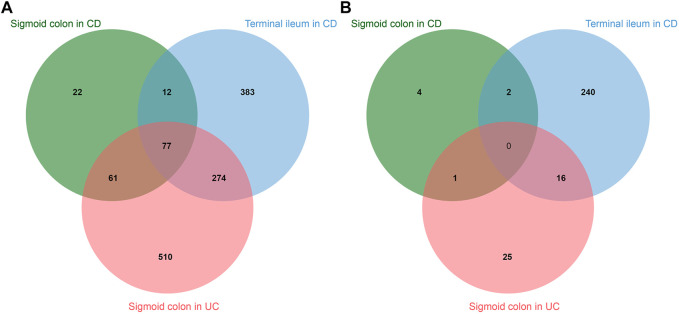

IBD includes CD, which affects both the small and large intestine, and UC, which affects the colon only. We performed an analysis of a publicly available RNA sequencing set of purified intestinal epithelial cells from pediatric biopsies including IBD and healthy controls (E-MTAB-5464) (Howell et al., 2018). We used the data on RNA expression in sigmoid colon of patients with UC and terminal ileum and sigmoid colon of patients with CD and individuals without IBD. Comparison of disease state with healthy control revealed the upregulation of 172 genes in sigmoid colon in CD, 476 genes in terminal ileum in CD, and 922 genes in sigmoid colon in UC. The downregulation was revealed for 7 genes in sigmoid colon in CD, 258 genes in terminal ileum in CD, and 42 genes in sigmoid colon in UC (Figure 5).

FIGURE 5.

Intersections of differentially expressed genes in sigmoid colon of patients with Chron’s disease (CD), terminal ileum of patients with CD, and sigmoid colon of patients with ulcerative colitis (UC). (A)—upregulated genes. (B)—downregulated genes.

Gene Set Enrichment Analysis has shown activation of HALLMARK_INFLAMMATORY_RESPONSE in all groups and downregulation of HALLMARK_OXIDATIVE_PHOSPHORYLATION in sigmoid colon in UC and terminal ileum in CD, possibly indicating hypoxic response (Samanta and Semenza, 2017). The common gene set for all pathologies includes 77 genes with significant activation of the following KEGG pathways: Cytokine-cytokine receptor interaction (hsa04060) and Chemokine signaling pathway (hsa04062), which indicates the immune nature of IBD. Moreover, enrichment analysis revealed significant activation of the HIF signaling pathway in terminal ileum in CD and sigmoid colon in UC.

We analyzed the intersection of these IBD-associated genes with possible HIF-associated gene set from the experiment with chemical hypoxia models in Caco-2 cells. We noted upregulation of ITGA5, MICB, PLAUR, and DYSF and downregulation of GSTA2, SLC2A2, and KDM8 in terminal ileum of patients with CD. Only two genes from Caco-2 experiment-derived gene set were also upregulated in sigmoid colon of patients with CD (BHLHE40 and PLAUR), and eleven genes from this gene set were upregulated in sigmoid colon of patients with UC (ITGA5, RNF183, BHLHE40, PLAUR, PFKFB3, FSCN1, SOCS3, RNF24, CSRP2, PIK3CD, DYSF).

The only differentially expressed gene in all samples was PLAUR, which encodes the urokinase-type plasminogen activator receptor (uPAR) which may indicate its involvement in the course of IBD. The HIF signaling pathway according to gene set enrichment analysis was activated in terminal ileum in CD and sigmoid colon in UC, and their gene list share ITGA5, PLAUR, and DYSF genes.

3.4 Transcription Factors Regulating ITGA5 and PLAUR Expression

As ITGA5 and PLAUR genes are both upregulated in hypoxia model and IBD specimens and interact with each other to activate intracellular signaling (Smith and Marshall, 2010). We performed an analysis of potential transcription factors regulating both these genes with the previously developed tool miRGTF-net (Nersisyan et al., 2021b) and received 345 potential transcription regulators of ITGA5 and PLAUR, including HIF1A and HIF3A. Next, we analyzed expression correlation for these transcription factors, ITGA5, and PLAUR in the mRNA-sequencing data of colorectal cancer samples from TCGA to find regulators which expression significantly correlates with both ITGA5 and PLAUR in the samples of intestinal origin. GRHL2 and ZC3H8 have a negative correlation and MSC, NFATC1, PRDM1, and SPI1 have a positive correlation with ITGA5 and PLAUR. Of these transcription factors, all except SPI1 are regulated by HIF1A according to miRGTF-net. Only NFATC1 has a tendency to be upregulated in Caco-2 according to our RNA sequencing data: 1.6 times in dCaco-2 with OD and uCaco-2 with CoCl2, 1.9 times in dCaco-2 with CoCl2, and 2.9 times in uCaco-2 with OD, suggesting its possible role in ITGA5 and PLAUR upregulation in hypoxia and IBD.

4 Discussion

There is no generally accepted list of genes that always reacting to HIF-pathway activation. Benita et al. have identified HIF-1-target genes combining genomic data from different experiments and found out core gene set of 17 genes that responded to hypoxia in all studied cell types (Benita et al., 2009). Of them, all genes responded to chemical HIF-stabilization at least in one type of cells and treatment options in our experiments, but only nine genes responded in both uCaco-2 and dCaco-2 upon CoCl2 and OD stimulation: ANKRD37, NDRG1, PDK1, BNIP3, DDIT4, P4HA1, KDM3A, BHLHE40, and ALDOC. Only nine genes from this core gene set were detected in proteomic data of dCaco-2 upon CoCl2 stimulation and five of them were differentially expressed on the protein level: NDRG1, PDK1, BNIP3, P4HA1, and ALDOC. Not all genes reacting to hypoxia have a HIF-binding site and some genes respond to HIF stabilization in specific cell sets (Benita et al., 2009). Hypoxia can induce gene expression not only directly through HIF, but also indirectly through regulation of microRNAs and transcription factors (Makarova et al., 2014). This makes it reasonable to search for a specific gene set responding to hypoxia in a particular cell type, as for the intestinal epithelium in our study.

CoCl2 and OD are known HIF inductors, acting through inhibition of HIF prolyl hydroxylases (Knyazev et al., 2021), so their effect on cells is regarded as a chemical model of hypoxia. Gene set enrichment analysis of differentially expressed genes in Caco-2 intestinal barrier model upon CoCl2 and OD exposure confirmed activation of hypoxia response and also an inflammatory response, proliferation, and apoptosis pathways, which are known effects of HIF activation (Corrado and Fontana, 2020).

Analysis of differentially expressed genes in the Caco-2 model of intestinal hypoxia revealed 115 upregulated and 69 downregulated genes. Enrichment analysis of this gene list confirmed HIF-1 signaling pathway activation and showed involvement of carbon metabolism and glycolysis/gluconeogenesis. HIF-dependent regulation of glycolytic, carbohydrate and fatty acid metabolism is a known process in the intestinal epithelium (Konjar et al., 2021).

Not always activation of a gene at the transcriptional level means activation at the translation level, so proteome data do not always correlate with transcriptomic data (Wang et al., 2019). We confirmed a significant correlation of gene expression at mRNA and protein level in Caco-2 cells exposed to CoCl2. It allows us to use RNA-sequencing data from the hypoxia experiment to search for HIF-dependent genes in samples of intestinal epithelium in IBD.

We searched for co-directed significant expression changes in the intestinal hypoxia model and intestinal epithelium in IBD. Possible HIF-associated gene list from Caco-2 model has seven genes in common with terminal ileum of patients with CD, two genes with sigmoid colon of patients with CD, and eleven genes with sigmoid colon of patients with UC. According to gene set enrichment analysis, the HIF signaling pathway was significantly activated in CD terminal ileum and UC sigmoid colon, which have three activated genes in common: ITGA5, PLAUR, and DYSF. BHLHE40 was upregulated for sigmoid colon in both UC and CD. Only PLAUR, encoding uPAR, was activated in all three clinical specimen groups. Comparison of differentially expressed genes from the KEGG HIF-1 pathway for the Caco-2 model, CD terminal ileum and UC sigmoid colon revealed intersections, with the most prominent changes for PFKFB3, TIMP1, ANGPT2, HK3, SERPINE1, and TLR4.

BHLHE40 encodes Basic Helix-Loop-Helix Family Member E40 that is a stress-inducible transcription factor and is activated by HIF and p53, regulating cell survival and proliferation (Kiss et al., 2020). It is a part of core response to hypoxia gene set (Benita et al., 2009) and regulates inflammatory response in the IBD model (Yu et al., 2018). DYSF encodes dysferlin that is a type-II transmembrane protein and is expressed in various tissues, primarily in muscle, controlling membrane repair and vesicle trafficking (Barefield et al., 2021). Its role in IBD is unclear, but elevated levels have been found in the blood of patients with IBD (Ostrowski et al., 2019).

Gene encoding uPAR was upregulated in all IBD samples. The three domains of the uPAR molecule form a cavity for the ligand of this receptor, the urokinase-type plasminogen activator (uPA). In this regard, uPAR is one of the key regulators of pericellular proteolysis, participating in the extracellular matrix remodeling and cell migration regulation (Gorrasi et al., 2020). Extracellular matrix degradation by protease systems is increased in inflamed and damaged tissues, including in IBD, which is an important component of tissue repair control (Genua et al., 2015).

uPAR can interact with vitronectin and integrins, leading to intracellular signal activation and regulating cell proliferation and survival (Smith and Marshall, 2010). An interaction between purified uPAR and α5β1 integrin has been shown in vitro (Wei et al., 2005), with the D3 domain of the uPAR molecule possibly forming the integrin-binding site (Chaurasia et al., 2006; Tang et al., 2008). Co-immunoprecipitation of uPAR and integrin α5β1 has also been detected (Ghiso et al., 1999; Wei et al., 2001). uPAR enhances the binding of integrin α5β1 to fibronectin (Ghiso et al., 1999; Monaghan et al., 2004) and increases cell proliferation through integrin α5β1 signaling (Aguirre-Ghiso et al., 2001; Monaghan-Benson and McKeown-Longo, 2006). The complex of α5β1 integrin and uPAR can lead to activation of the epidermal growth factor receptor signaling pathway (Aguirre Ghiso, 2002; Liu et al., 2002). There was a significant increase in the expression of the ITGA5 gene encoding integrin α5 in Caco-2 cells upon HIF stabilization, in terminal ileum in CD, and in sigmoid colon in UC, which together with the increased expression of uPAR may lead to increased signaling through these molecules.

The role of uPAR in the IBD pathogenesis remains unclear. uPAR is expressed in intestinal crypts in normal state and IBD, although no significant expression difference has been detected (Gibson and Rosella, 1996). The intestinal nerve tissue expresses uPAR in IBD, in contrast to the nerve tissue of the healthy intestine (Laerum et al., 2008). In an animal model of IBD, increased uPAR expression at the protein and mRNA levels was detected in intestinal tissue, and this increase was predominantly due to macrophages in the intestinal wall (Genua et al., 2015). In our experiment, we observed increased PLAUR expression in dCaco-2 and uCaco-2 cells as a model of intestinal epithelium upon hypoxia exposure and HIF activation. Howell et al. used magnetic bead sorting for the epithelial cell adhesion molecule to sequence intestinal epithelium in IBD and healthy control (Howell et al., 2018), indicating activation of uPAR expression specifically in the intestinal epithelium.

On the one hand, HIF-activated uPAR expression stimulates extracellular matrix degradation promoting epithelial barrier destruction and cell invasion in carcinomas (Büchler et al., 2009). On the other hand, the uPAR pathway is required for efficient epithelial wound repair by stimulating extracellular matrix remodeling and cell migration (Stewart et al., 2012). It is likely that just as varying degrees of hypoxia can both promote and impair gut barrier function, so varying degrees of uPAR activation can be both damaging and regenerative. Mice with uPAR knockdown were more susceptible to the development of IBD in an experimental model (Genua et al., 2015), which may indicate a protective role of uPAR during HIF activation and inflammation. The total level of uPAR increases in patients with IBD, but the level of membrane-associated uPAR decreases as proteolysis and accumulation of the soluble form of uPAR occurs, which does not perform its functions in the activation of intracellular signaling pathways (Genua et al., 2015) This is consistent with the elevated blood level of the soluble form of uPAR in IBD (Lönnkvist et al., 2011; Kolho et al., 2012). Thus, increased uPAR expression in the intestinal epithelium may be associated not with the destruction of the extracellular matrix and damage to the intestinal wall but rather with damage adaptation, stimulation of migration and proliferation to repair the epithelial layer through interaction with integrins. Pharmacological activation of the HIF-signaling pathway stimulated intestinal epithelium repair regulating integrin expression and function (Goggins et al., 2021).

HIF-1 activation can upregulate uPAR expression (Büchler et al., 2009; Nishi et al., 2016). Hypoxia also enhances the expression of ITGA5 (Ju et al., 2017). We identified possible transcription regulators of ITGA5 and PLAUR with the previously developed tool miRGTF-net (Nersisyan et al., 2021b). HIF1A and HIF3A are both transcription factors that can regulate these genes. Analysis of correlation of all detected transcription factors with ITGA5 and PLAUR in the colorectal cancer samples from TCGA revealed six genes with significant correlation. Of these six genes, only NFATC1 expression has a tendency to be upregulated in uCaco-2 and dCaco-2 upon HIF-pathway activation, suggesting its regulatory role, and NFATC1 expression is regulated by HIF1A according to miRGTF-net. This suggestion is supported by NFATC1 activation in hypoxic conditions (Shin et al., 2015; Xiao et al., 2020).

5 Conclusion

Hypoxia is a common feature in IBD pathogenesis. Chemical hypoxia induction in the Caco-2 intestinal model with cobalt (II) chloride and oxyquinoline derivative revealed potential intestinal HIF-associated gene core. Of that gene core, ITGA5 and PLAUR genes were also upregulated in intestinal epithelial cells in IBD, suggesting activation of tissue regeneration program upon HIF activation. HIF-dependent upregulation of transcription factor NFATC1 is a possible mechanism of ITGA5 and PLAUR activation.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets presented in this study can be found in online repositories. The names of the repository/repositories and accession number(s) can be found in the article/Supplementary Material.

Author Contributions

DM conceptualized and reviewed the work. MS worked on analysis and visualization of the bioinformatics data presented. MR carried out laboratory experiments. EK carried out laboratory experiments, worked on curation, analysis and visualization of the data presented, prepared the original draft, edited and reviewed it. All authors contributed to the article and approved the submitted version.

Funding

The reported study was funded by RFBR, project number 20-34-70092 (EK, DM, MR) and Laboratory of Molecular Physiology at HSE University (MS).

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher’s Note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Supplementary Material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fgene.2021.791640/full#supplementary-material

References

- Aguirre Ghiso J. A. (2002). Inhibition of FAK Signaling Activated by Urokinase Receptor Induces Dormancy in Human Carcinoma Cells In Vivo . Oncogene 21, 2513–2524. 10.1038/sj.onc.1205342 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aguirre-Ghiso J. A., Liu D., Mignatti A., Kovalski K., Ossowski L. (2001). Urokinase Receptor and Fibronectin Regulate the ERKMAPK to p38MAPK Activity Ratios that Determine Carcinoma Cell Proliferation or Dormancy In Vivo . Mol. Biol. Cel 12, 863–879. 10.1091/mbc.12.4.863 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bardou P., Mariette J., Escudié F., Djemiel C., Klopp C. (2014). Jvenn: an Interactive Venn Diagram Viewer. BMC Bioinformatics 15, 293. 10.1186/1471-2105-15-293 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barefield D. Y., Sell J. J., Tahtah I., Kearns S. D., McNally E. M., Demonbreun A. R. (2021). Loss of Dysferlin or Myoferlin Results in Differential Defects in Excitation-Contraction Coupling in Mouse Skeletal Muscle. Sci. Rep. 11, 15865. 10.1038/s41598-021-95378-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benita Y., Kikuchi H., Smith A. D., Zhang M. Q., Chung D. C., Xavier R. J. (2009). An Integrative Genomics Approach Identifies Hypoxia Inducible Factor-1 (HIF-1)-Target Genes that Form the Core Response to Hypoxia. Nucleic Acids Res. 37, 4587–4602. 10.1093/nar/gkp425 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Borg-Bartolo S. P., Boyapati R. K., Satsangi J., Kalla R. (2020). Precision Medicine in Inflammatory Bowel Disease: Concept, Progress and Challenges. F1000Res 9, 54. 10.12688/f1000research.20928.1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Büchler P., Reber H. A., Tomlinson J. S., Hankinson O., Kallifatidis G., Friess H., et al. (2009). Transcriptional Regulation of Urokinase-type Plasminogen Activator Receptor by Hypoxia-Inducible Factor 1 Is Crucial for Invasion of Pancreatic and Liver Cancer. Neoplasia 11, 196–IN12. 10.1593/neo.08734 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cancer Genome Atlas Network (2012). Comprehensive Molecular Characterization of Human colon and Rectal Cancer. Nature 487, 330–337. 10.1038/nature11252 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chaurasia P., Aguirre-Ghiso J. A., Liang O. D., Gardsvoll H., Ploug M., Ossowski L. (2006). A Region in Urokinase Plasminogen Receptor Domain III Controlling a Functional Association with α5β1 Integrin and Tumor Growth. J. Biol. Chem. 281, 14852–14863. 10.1074/jbc.M512311200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Corrado C., Fontana S. (2020). Hypoxia and HIF Signaling: One Axis with Divergent Effects. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 21, 5611. 10.3390/ijms21165611 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ding X., Hu X., Chen Y., Xie J., Ying M., Wang Y., et al. (2021). Differentiated Caco-2 Cell Models in Food-Intestine Interaction Study: Current Applications and Future Trends. Trends Food Sci. Technol. 107, 455–465. 10.1016/j.tifs.2020.11.015 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Dobin A., Davis C. A., Schlesinger F., Drenkow J., Zaleski C., Jha S., et al. (2013). STAR: Ultrafast Universal RNA-Seq Aligner. Bioinformatics 29, 15–21. 10.1093/bioinformatics/bts635 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frankish A., Diekhans M., Ferreira A.-M., Johnson R., Jungreis I., Loveland J., et al. (2019). GENCODE Reference Annotation for the Human and Mouse Genomes. Nucleic Acids Res. 47, D766–D773. 10.1093/nar/gky955 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Genua M., D'Alessio S., Cibella J., Gandelli A., Sala E., Correale C., et al. (2015). The Urokinase Plasminogen Activator Receptor (uPAR) Controls Macrophage Phagocytosis in Intestinal Inflammation. Gut 64, 589–600. 10.1136/gutjnl-2013-305933 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ghiso J. A. A., Kovalski K., Ossowski L. (1999). Tumor Dormancy Induced by Downregulation of Urokinase Receptor in Human Carcinoma Involves Integrin and MAPK Signaling. J. Cel Biol. 147, 89–104. 10.1083/jcb.147.1.89 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gibson P. R., Rosella O. (1996). Abnormalities of the Urokinase System in Colonic Crypt Cells from Patients with Ulcerative Colitis. Inflamm. Bowel Dis. 2, 105–114. Available at: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/23282516 . 10.1097/00054725-199606000-00006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glover L. E., Lee J. S., Colgan S. P. (2016). Oxygen Metabolism and Barrier Regulation in the Intestinal Mucosa. J. Clin. Invest. 126, 3680–3688. 10.1172/JCI84429 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goggins B. J., Minahan K., Sherwin S., Soh W. S., Pryor J., Bruce J., et al. (2021). Pharmacological HIF-1 Stabilization Promotes Intestinal Epithelial Healing through Regulation of α-Integrin Expression and Function. Am. J. Physiol. Liver Physiol. 320, G420–G438. 10.1152/ajpgi.00192.2020 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gorrasi A., Petrone A. M., Li Santi A., Alfieri M., Montuori N., Ragno P. (2020). New Pieces in the Puzzle of uPAR Role in Cell Migration Mechanisms. Cells 9, 2531. 10.3390/cells9122531 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Howell K. J., Kraiczy J., Nayak K. M., Gasparetto M., Ross A., Lee C., et al. (2018). DNA Methylation and Transcription Patterns in Intestinal Epithelial Cells from Pediatric Patients with Inflammatory Bowel Diseases Differentiate Disease Subtypes and Associate with Outcome. Gastroenterology 154, 585–598. 10.1053/j.gastro.2017.10.007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang D. W., Sherman B. T., Lempicki R. A. (2009). Bioinformatics Enrichment Tools: Paths toward the Comprehensive Functional Analysis of Large Gene Lists. Nucleic Acids Res. 37, 1–13. 10.1093/nar/gkn923 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ivanenkov Y. A., Vasilevski S. V., Beloglazkina E. K., Kukushkin M. E., Machulkin A. E., Veselov M. S., et al. (2015). Design, Synthesis and Biological Evaluation of Novel Potent MDM2/p53 Small-Molecule Inhibitors. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 25, 404–409. 10.1016/j.bmcl.2014.09.070 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ju J. A., Godet I., Ye I. C., Byun J., Jayatilaka H., Lee S. J., et al. (2017). Hypoxia Selectively Enhances Integrin α5β1 Receptor Expression in Breast Cancer to Promote Metastasis. Mol. Cancer Res. 15, 723–734. 10.1158/1541-7786.MCR-16-0338 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kanehisa M., Furumichi M., Sato Y., Ishiguro-Watanabe M., Tanabe M. (2021). KEGG: Integrating Viruses and Cellular Organisms. Nucleic Acids Res. 49, D545–D551. 10.1093/nar/gkaa970 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kerber E. L., Padberg C., Koll N., Schuetzhold V., Fandrey J., Winning S. (2020). The Importance of Hypoxia-Inducible Factors (HIF-1 and HIF-2) for the Pathophysiology of Inflammatory Bowel Disease. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 21, 8551. 10.3390/ijms21228551 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim Y.-E., Lee M., Gu H., Kim J., Jeong S., Yeo S., et al. (2018). Hypoxia-inducible Factor-1 (HIF-1) Activation in Myeloid Cells Accelerates DSS-Induced Colitis Progression in Mice. Dis. Model. Mech. 11, dmm033241. 10.1242/dmm.033241 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim Y.-I., Yi E.-J., Kim Y.-D., Lee A. R., Chung J., Ha H. C., et al. (2021). Local Stabilization of Hypoxia-Inducible Factor-1α Controls Intestinal Inflammation via Enhanced Gut Barrier Function and Immune Regulation. Front. Immunol. 11, 609689. 10.3389/fimmu.2020.609689 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kiss Z., Mudryj M., Ghosh P. M. (2020). Non-Circadian Aspects of BHLHE40 Cellular Function in Cancer. Genes Cancer 11, 1–19. 10.18632/genesandcancer.201 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Knyazev E., Paul S. (2021). Levels of miR-374 Increase in BeWo B30 Cells Exposed to Hypoxia. Bull. Russ. State. Med. Univ. 11, 17. 10.24075/brsmu.2021.021 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Knyazev E. N., Petrov V. A., Gazizov I. N., Gerasimenko T. N., Tsypina I. M., Tonevitsky A. G., et al. (2019a). Oxyquinoline-Dependent Changes in Claudin-Encoding Genes Contribute to Impairment of the Barrier Function of the Trophoblast Monolayer. Bull. Exp. Biol. Med. 166, 369–372. 10.1007/s10517-019-04352-z [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Knyazev E. N., Zakharova G. S., Astakhova L. A., Tsypina I. M., Tonevitsky A. G., Sukhikh G. T. (2019b). Metabolic Reprogramming of Trophoblast Cells in Response to Hypoxia. Bull. Exp. Biol. Med. 166, 321–325. 10.1007/s10517-019-04342-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Knyazev E. N., Paul S. Y., Tonevitsky A. G. (2021). Chemical Induction of Trophoblast Hypoxia by Cobalt Chloride Leads to Increased Expression of DDIT3. Dokl. Biochem. Biophys. 499, 251–256. 10.1134/S1607672921040104 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kolho K.-L., Valtonen E., Rintamäki H., Savilahti E. (2012). Soluble Urokinase Plasminogen Activator Receptor suPAR as a Marker for Inflammation in Pediatric Inflammatory Bowel Disease. Scand. J. Gastroenterol. 47, 951–955. 10.3109/00365521.2012.699549 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Konjar Š., Pavšič M., Veldhoen M. (2021). Regulation of Oxygen Homeostasis at the Intestinal Epithelial Barrier Site. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 22, 9170. 10.3390/ijms22179170 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Korotkevich G., Sukhov V., Budin N., Shpak B., Artyomov M. N., Sergushichev A. (2016). Fast Gene Set Enrichment Analysis. bioRxiv. 10.1101/060012 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Laerum O. D., Illemann M., Skarstein A., Helgeland L., Øvrebø K., Danø K., et al. (2008). Crohn's Disease but Not Chronic Ulcerative Colitis Induces the Expression of PAI-1 in Enteric Neurons. Am. J. Gastroenterol. 103, 2350–2358. 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2008.01930.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liberzon A., Birger C., Thorvaldsdóttir H., Ghandi M., Mesirov J. P., Tamayo P. (2015). The Molecular Signatures Database Hallmark Gene Set Collection. Cel Syst. 1, 417–425. 10.1016/j.cels.2015.12.004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu D., Ghiso J. A. A., Estrada Y., Ossowski L. (2002). EGFR Is a Transducer of the Urokinase Receptor Initiated Signal that Is Required for In Vivo Growth of a Human Carcinoma. Cancer Cell 1, 445–457. 10.1016/s1535-6108(02)00072-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lönnkvist M. H., Theodorsson E., Holst M., Ljung T., Hellström P. M. (2011). Blood Chemistry Markers for Evaluation of Inflammatory Activity in Crohn's Disease during Infliximab Therapy. Scand. J. Gastroenterol. 46, 420–427. 10.3109/00365521.2010.539253 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Love M. I., Huber W., Anders S. (2014). Moderated Estimation of Fold Change and Dispersion for RNA-Seq Data with DESeq2. Genome Biol. 15, 550. 10.1186/s13059-014-0550-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Makarova J. A., Maltseva D. V., Galatenko V. V., Abbasi A., Maximenko D. G., Grigoriev A. I., et al. (2014). Exercise Immunology Meets MiRNAs. Exerc. Immunol. Rev. 20, 135–164. Available at: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/24974725. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maltseva D., Poloznikov A., Artyushenko V. (2020). Selective Changes in Expression of Integrin α-Subunits in the Intestinal Epithelial Caco-2 Cells under Conditions of Hypoxia and Microcirculation. Bull. Russ. State. Med. Univ. 23, 30. 10.24075/brsmu.2020.078 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Martin M. (2011). Cutadapt Removes Adapter Sequences from High-Throughput Sequencing Reads. EMBnet j. 17, 10. 10.14806/ej.17.1.200 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Monaghan E., Gueorguiev V., Wilkins-Port C., McKeown-Longo P. J. (2004). The Receptor for Urokinase-type Plasminogen Activator Regulates Fibronectin Matrix Assembly in Human Skin Fibroblasts. J. Biol. Chem. 279, 1400–1407. 10.1074/jbc.M310374200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Monaghan-Benson E., McKeown-Longo P. J. (2006). Urokinase-Type Plasminogen Activator Receptor Regulates a Novel Pathway of Fibronectin Matrix Assembly Requiring Src-dependent Transactivation of Epidermal Growth Factor Receptor. J. Biol. Chem. 281, 9450–9459. 10.1074/jbc.M501901200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muñoz‐Sánchez J., Chánez‐Cárdenas M. E. (2019). The Use of Cobalt Chloride as a Chemical Hypoxia Model. J. Appl. Toxicol. 39, 556–570. 10.1002/jat.3749 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mutsenko V. V., Bazhenov V. V., Rogulska O., Tarusin D. N., Schütz K., Brüggemeier S., et al. (2017). 3D Chitinous Scaffolds Derived from Cultivated marine Demosponge Aplysina Aerophoba for Tissue Engineering Approaches Based on Human Mesenchymal Stromal Cells. Int. J. Biol. Macromolecules 104, 1966–1974. 10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2017.03.116 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nersisyan S., Galatenko A., Chekova M., Tonevitsky A. (2021a). Hypoxia-Induced miR-148a Downregulation Contributes to Poor Survival in Colorectal Cancer. Front. Genet. 12, 662468. 10.3389/fgene.2021.662468 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nersisyan S., Galatenko A., Galatenko V., Shkurnikov M., Tonevitsky A. (2021b). miRGTF-Net: Integrative miRNA-Gene-TF Network Analysis Reveals Key Drivers of Breast Cancer Recurrence. PLoS One 16, e0249424. 10.1371/journal.pone.0249424 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nikulin S. V., Knyazev E. N., Gerasimenko T. N., Shilin S. A., Gazizov I. N., Zakharova G. S., et al. (2018a). Non-Invasive Evaluation of Extracellular Matrix Formation in the Intestinal Epithelium. Bull. Exp. Biol. Med. 166, 35–38. 10.1007/s10517-018-4283-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nikulin S. V., Knyazev E. N., Poloznikov A. A., Shilin S. A., Gazizov I. N., Zakharova G. S., et al. (2018b). Expression of SLC30A10 and SLC23A3 Transporter mRNAs in Caco-2 Cells Correlates with an Increase in the Area of the Apical Membrane. Mol. Biol. 52, 577–582. 10.1134/S0026893318040131 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Knyazev E. N., Maltseva D. V., Sakharov D. A., Gerasimenko T. N., Gerasimenko T. N. (2019). Use of Impedance Spectroscopy to Assess the Effect of Laminins on the In Vitro Differentiation of Intestinal Cells. Biiotehnologiâ (Mosk.) 35, 102–107. 10.21519/0234-2758-2019-35-6-102-107 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Nishi H., Sasaki T., Nagamitsu Y., Terauchi F., Nagai T., Nagao T., et al. (2016). Hypoxia Inducible Factor-1 Mediates Upregulation of Urokinase-type Plasminogen Activator Receptor Gene Transcription during Hypoxia in Cervical Cancer Cells. Oncol. Rep. 35, 992–998. 10.3892/or.2015.4449 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ostrowski J., Goryca K., Goryca K., Lazowska I., Rogowska A., Paziewska A., et al. (2019). Common Functional Alterations Identified in Blood Transcriptome of Autoimmune Cholestatic Liver and Inflammatory Bowel Diseases. Sci. Rep. 9, 7190. 10.1038/s41598-019-43699-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pral L. P., Fachi J. L., Corrêa R. O., Colonna M., Vinolo M. A. R. (2021). Hypoxia and HIF-1 as Key Regulators of Gut Microbiota and Host Interactions. Trends Immunol. 42, 604–621. 10.1016/j.it.2021.05.004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ramakrishnan S. K., Shah Y. M. (2016). Role of Intestinal HIF-2α in Health and Disease. Annu. Rev. Physiol. 78, 301–325. 10.1146/annurev-physiol-021115-105202 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rangel-Huerta E., Maldonado E. (2017). Transit-Amplifying Cells in the Fast Lane from Stem Cells towards Differentiation. Stem Cell Int. 2017, 7602951. 10.1155/2017/7602951 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sakharov D., Maltseva D., Knyazev E., Nikulin S., Poloznikov A., Shilin S., et al. (2019). Towards Embedding Caco-2 Model of Gut Interface in a Microfluidic Device to Enable Multi-Organ Models for Systems Biology. BMC Syst. Biol. 13, 19. 10.1186/s12918-019-0686-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Samanta D., Semenza G. L. (2017). Maintenance of Redox Homeostasis by Hypoxia-Inducible Factors. Redox Biol. 13, 331–335. 10.1016/j.redox.2017.05.022 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Samatov T. R., Senyavina N. V., Galatenko V. V., Trushkin E. V., Tonevitskaya S. A., Alexandrov D. E., et al. (2016). Tumour-Like Druggable Gene Expression Pattern of CaCo2 Cells in Microfluidic Chip. Biochip J. 10, 215–220. 10.1007/s13206-016-0308-3 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Samatov T. R., Galatenko V. V., Senyavina N. V., Galatenko A. V., Shkurnikov M. Y., Tonevitskaya S. A., et al. (2017). miRNA-Mediated Expression Switch of Cell Adhesion Genes Driven by Microcirculation in Chip. Biochip J. 11, 262–269. 10.1007/s13206-017-1305-x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Schoultz I., Keita Å. V. (2020). The Intestinal Barrier and Current Techniques for the Assessment of Gut Permeability. Cells 9, 1909. 10.3390/cells9081909 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shin J., Nunomiya A., Kitajima Y., Dan T., Miyata T., Nagatomi R. (2015). Prolyl Hydroxylase Domain 2 Deficiency Promotes Skeletal Muscle Fiber-Type Transition via a calcineurin/NFATc1-Dependent Pathway. Skeletal Muscle 6, 5. 10.1186/s13395-016-0079-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Singhal R., Shah Y. M. (2020). Oxygen Battle in the Gut: Hypoxia and Hypoxia-Inducible Factors in Metabolic and Inflammatory Responses in the Intestine. J. Biol. Chem. 295, 10493–10505. 10.1074/jbc.REV120.011188 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smirnov I., Carletti E., Kurkova I., Nachon F., Nicolet Y., Mitkevich V. A., et al. (2011). Reactibodies Generated by Kinetic Selection Couple Chemical Reactivity with Favorable Protein Dynamics. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 108, 15954–15959. 10.1073/pnas.1108460108 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith H. W., Marshall C. J. (2010). Regulation of Cell Signalling by uPAR. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cel Biol. 11, 23–36. 10.1038/nrm2821 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Solanki S., Devenport S. N., Ramakrishnan S. K., Shah Y. M. (2019). Temporal Induction of Intestinal Epithelial Hypoxia-Inducible Factor-2α Is Sufficient to Drive Colitis. Am. J. Physiology-Gastrointestinal Liver Physiol. 317, G98–G107. 10.1152/ajpgi.00081.2019 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stewart C. E., Nijmeh H. S., Brightling C. E., Sayers I. (2012). uPAR Regulates Bronchial Epithelial Repair In Vitro and Is Elevated in Asthmatic Epithelium. Thorax 67, 477–487. 10.1136/thoraxjnl-2011-200508 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Subramanian A., Tamayo P., Mootha V. K., Mukherjee S., Ebert B. L., Gillette M. A., et al. (2005). Gene Set Enrichment Analysis: a Knowledge-Based Approach for Interpreting Genome-Wide Expression Profiles. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 102, 15545–15550. 10.1073/pnas.0506580102 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tang C.-H., Hill M. L., Brumwell A. N., Chapman H. A., Wei Y. (2008). Signaling through Urokinase and Urokinase Receptor in Lung Cancer Cells Requires Interactions with β1 Integrins. J. Cel Sci. 121, 3747–3756. 10.1242/jcs.029769 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taylor C. T. (2018). Hypoxia in the Gut. Cell Mol. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 5, 61–62. 10.1016/j.jcmgh.2017.09.005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang D., Eraslan B., Wieland T., Hallström B., Hopf T., Zolg D. P., et al. (2019). A Deep Proteome and Transcriptome Abundance Atlas of 29 Healthy Human Tissues. Mol. Syst. Biol. 15, e8503. 10.15252/msb.20188503 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wei Y., Eble J. A., Wang Z., Kreidberg J. A., Chapman H. A. (2001). Urokinase Receptors Promote β1 Integrin Function through Interactions with Integrin α3β1. Mol. Biol. Cell 12, 2975–2986. 10.1091/mbc.12.10.2975 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wei Y., Czekay R.-P., Robillard L., Kugler M. C., Zhang F., Kim K. K., et al. (2005). Regulation of α5β1 Integrin Conformation and Function by Urokinase Receptor Binding. J. Cel Biol. 168, 501–511. 10.1083/jcb.200404112 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xiao C., Bai G., Du Y., Jiang H., Yu X. (2020). Association of High HIF-1α Levels in Serous Periodontitis with External Root Resorption by the NFATc1 Pathway. J. Mol. Hist. 51, 649–658. 10.1007/s10735-020-09911-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xue X., Ramakrishnan S., Anderson E., Taylor M., Zimmermann E. M., Spence J. R., et al. (2013). Endothelial PAS Domain Protein 1 Activates the Inflammatory Response in the Intestinal Epithelium to Promote Colitis in Mice. Gastroenterology 145, 831–841. 10.1053/j.gastro.2013.07.010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yu F., Sharma S., Jankovic D., Gurram R. K., Su P., Hu G., et al. (2018). The Transcription Factor Bhlhe40 Is a Switch of Inflammatory versus Antiinflammatory Th1 Cell Fate Determination. J. Exp. Med. 215, 1813–1821. 10.1084/jem.20170155 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The datasets presented in this study can be found in online repositories. The names of the repository/repositories and accession number(s) can be found in the article/Supplementary Material.