ABSTRACT

Alternative polyadenylation (APA) is a widespread post-transcriptional modification method that changes the 3′ ends of transcripts by altering poly(A) site usage. However, the longitudinal transcriptomic 3′ end profile and its mechanism of action are poorly understood. We applied diurnal time-course poly(A) tag sequencing (PAT-seq) for Arabidopsis and identified 3284 genes that generated both rhythmic and arrhythmic transcripts. These two classes of transcripts appear to exhibit dramatic differences in expression and translation activisty. The asynchronized transcripts derived by APA are embedded with different poly(A) signals, especially for rhythmic transcripts, which contain higher AAUAAA and UGUA signal proportions. The Pol II occupancy maximum is reached upstream of rhythmic poly(A) sites, while it is present directly at arrhythmic poly(A) sites. Integrating H3K9ac and H3K4me3 time-course data analyses revealed that transcriptional activation of histone markers may be involved in the differentiation of rhythmic and arrhythmic APA transcripts. These results implicate an interplay between histone modification and RNA 3′-end processing, shedding light on the mechanism of transcription rhythm and alternative polyadenylation.

KEYWORDS: Polyadenylation, diurnal rhythm, post-transcriptional regulation, poly(A) signal, histone modification, Pol II

Introduction

Rhythmic gene expression, which is common in eukaryotes, is controlled by a set of protein complexes that respond to the light/dark cycle [1,2]. In plants, this rhythmic regulatory network severely affects flowering time, development, and disease resistance, among others [3]. The advent of microarray and RNA-seq has helped to identify many rhythmically expressed genes in plants [4–8]. Gene expression rhythms are predominantly achieved by light and the internal circadian clock [9]. The central clock regulatory loop consists of two MYB-like transcription factors, LATE ELONGATED HYPOCOTYL (LHY) and CIRCADIAN CLOCK ASSOCIATED 1 (CCA1), which act as repressors of TIMING OF CAB EXPRESSION1 (TOC1). Conversely, TOC1 indirectly represses the expression of CCA1 and LHY [10]. The central loop is in crosstalk with a morning and evening loop [11]. In the morning loop, PSEUDORESPONSE REGULATOR 5 (PRR5), PRR7, and PRR9 bind to the promoters of CCA1 and LHY and repress their expression [12]. LHY and CCA1 in turn activate the expression of PRR9 and PRR7 [13]. The evening loop consists of bidirectional regulation between TOC1 and GIGANTEA (GI), together with the evening complex [11]. The EARLY FLOWERING3 (ELF3), ELF4, LUX ARRYTHMO (LUX), and BROTHER OF LUX ARRHYTHMO (BOA) constitute the evening complex, which acts as a transcriptional repressor targeting PRR9, PRR7, and LUX itself [14]. Although the components vary, the central oscillators of higher plants, animals, and fungi are similar [15,16].

The complex regulation of diurnal gene expression requires precise transcription, maturation, and translation. Polyadenylation is an essential post-transcriptional process for most eukaryotic mRNA maturation, stability, nuclear exportation, and translation activity [17]. The polyadenylation process is mediated by protein complexes that recognize several poly(A) signals and cleave downstream, following poly(A) tail synthesis [18]. These protein complexes include the cleavage and polyadenylation specificity factor (CPSF) complex, cleavage stimulatory factor (CstF) complex, cleavage factor Im (CFIm) complex, cleavage factor IIm (CFIIm) complex, and poly(A) polymerase (PAP) [19–21]. Of these, AtCPSF30 and AtCPSF100 were demonstrated to be genetically associated with poly(A) signal choices in the near upstream element (NUE) and far upstream element (FUE) in Arabidopsis, respectively [22,23]. The sites for polyadenylation (poly(A) sites, also designated as cleavage sites) are not exclusively distributed at the end of the gene bodies. Rather, they can be found in alternative areas within the gene body, which are known as alternative polyadenylation (APA) sites. Research has demonstrated that >50% of genes use APA in plants and animals [24–29]. APA can directly change the protein-coding sequences or gain/exclude regulatory elements by altering the 3ʹ UTR length, modulating gene expression, and, in turn, resulting in phenotypic variation [30–32]. APA has also been shown to be associated with circadian regulation. Our results showed that polyadenylation is required to maintain the rhythms of TOC1 and CCA1 [33]. In murine liver and embryonic fibroblasts, cold-induced proteins regulate the amplitude of temperature entrained by circadian gene expression by APA [34]. Moreover, approximately 1000 genes exhibit a circadian rhythm with proximal/distal poly(A) site usage in mouse livers [34,35]. A mathematical model was proposed to describe the population dynamics of APA transcripts in conjunction with rhythmic expression [36].

A recent study has revealed that transcription activation-associated histone markers participate in the regulation of diurnal gene expression [37]. Moreover, histone modifications are associated with APA [38]. Recently, we reported that histone deacetylation participates in 3ʹ-end processing in Arabidopsis [39]. Histone markers organize chromatin states and affect Pol II occupancy, which confers co-transcription [40,41]. It is well known that Pol II occupancy largely determines transcription processing, of which Serine 2 phosphorylation of Pol II is critical for mRNA 3ʹ-end processing [42,43]. These results indicate that transcription rhythm formation is a systematic regulatory network orchestrated throughout chromatin organization, co-transcription, and RNA maturation.

Although studies have revealed that polyadenylation and APA function in regulating the transcription rhythm, arrhythmic transcripts are rarely addressed. Specifically, neither the features nor the mechanism of action of the APA genes producing both rhythmic and arrhythmic transcripts has been reported. Herein, we have employed poly(A) tag sequencing (PAT-seq) to study the dynamic APA profile throughout the diurnal light/dark cycle of Arabidopsis. PAT-seq is a high-throughput method that exclusively sequences the 3ʹ end of mRNA [44], which preserves the poly(A) tail to allow mature RNA identification and reveals the poly(A) sites at a single nucleotide resolution. By integrating with time-course analyses, this approach allowed us to classify APA events that produce both rhythmic and arrhythmic transcripts. Furthermore, public datasets of nascent RNA-seq and ChIP-seq of H3K9ac and H3K4me3 were used to investigate the potential mechanisms of rhythmic and arrhythmic transcription differentiation.

Results

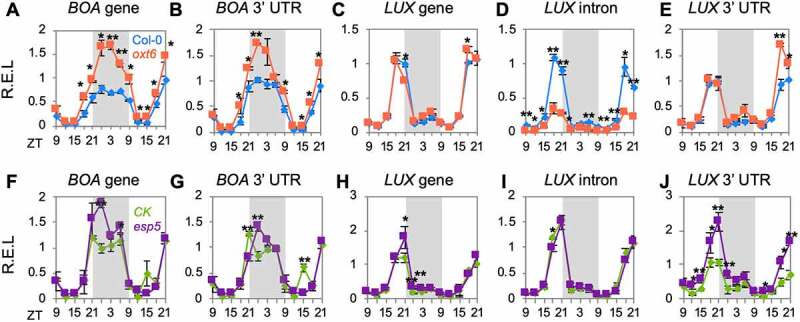

Polyadenylation is required for orchestrating the diurnal expression level of APA isoforms of clock genes

We have previously reported that the poly(A) factor PCFS4 regulates the rhythm of TOC1 and CCA1 [33]. To investigate whether polyadenylation is commonly required for the diurnal expression levels and time-course expression profiles of clock genes, BOA and LUX were studied in two mutants of core poly(A) factors (CPSF30 and CPSF100). In the CPSF30-knockout mutant (oxt6), the amplitude of BOA was dramatically enhanced during the night at both gene (primers target to 5ʹ UTR) and transcription levels (primers target to the end of 3ʹ UTR) (Figure 1(a,b)). The transcription model of LUX has allowed us to quantify the two transcripts generated by APA. We found that the knockout of CPSF30 dramatically repressed the amplitude of intronic LUX polyadenylation at the end of the light period. Conversely, the amplitude of the 3ʹ UTR polyadenylated transcript of LUX was significantly increased by the end of the 2nd light period (the 8th day of seedling) (Figures 1c and 1e)). The results demonstrate that the amplitude of APA transcripts produced by LUX can be differentially regulated by CPSF30. The diurnal expression level of BOA within the hypermorphic CPSF100 mutant (esp5) also changed (Figure 1(f,g)). The peak of the BOA gene and 3ʹ UTR polyadenylated transcript was altered from zeitgeber time 21 (ZT21) to ZT24 in esp5. CPSF100 dramatically affected the amplitude of the 3ʹ UTR polyadenylated transcripts in LUX (Figures 1h and 1j)). The results demonstrate that polyadenylation is required for maintaining proper diurnal expression levels of clock genes, and APA transcripts that originate from the same gene can be differentially regulated by poly(A) factors.

Figure 1.

Defective polyadenylation reshapes the rhythm of clock genes. Relative expression level (R.E.L) of gene and transcript expression levels of clock genes (BOA and LUX) in mutants AtCPSF30 (oxt6) (a-e) and AtCPSF100 (esp5) (f-j). The grey box indicates the subjective night. Error bars represent the standard deviation from three biological replicates and asterisks are indicative of statistically significant differences using one-way ANOVA. ZT indicates Zeitgeber time. In (a–j), data are presented as mean ± SD. *p-value < 0.05. **p-value < 0.01

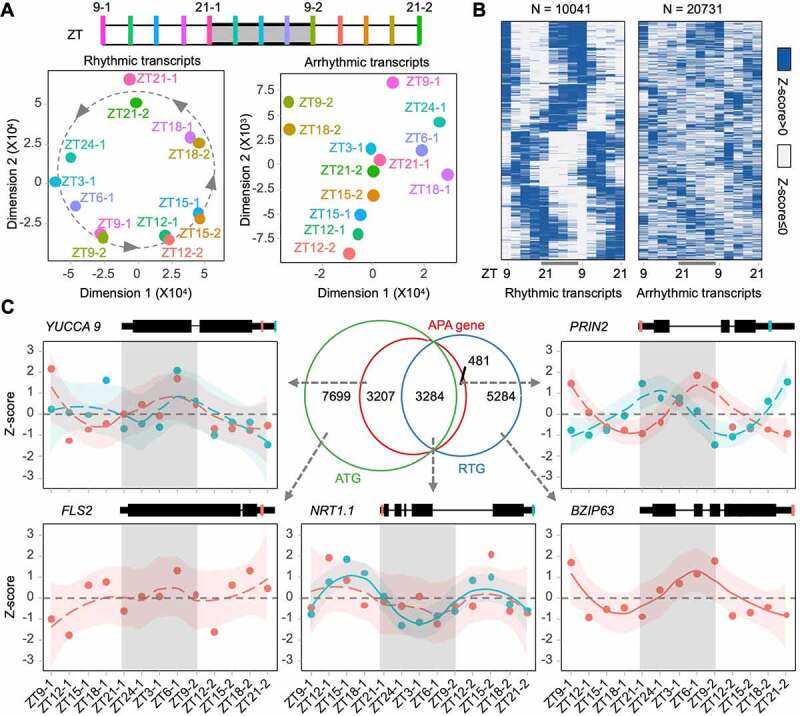

Dynamic diurnal rhythm of polyadenylation in Arabidopsis

As shown in (Figure 1), APA transcripts from one gene appear in different rhythms. Thus, we employed PAT-seq to profile dynamic polyadenylation across two light periods and one night period at three-hour intervals (Figure 2(a) upper panel). Sequencing coverage showed rhythmic 3ʹ transcript ends of known clock genes, such as BOA, LUX, CCA1, and TOC1 (Supplemental Figure S1A). The diurnal rhythm of each poly(A) transcript was calculated using the MetaCycle package [45]. Transcripts were classified into rhythmic and arrhythmic subclasses based on Benjamini Hochberg p values. The results show that PRIN2 generates two rhythmic transcripts, and FPA generates both rhythmic and arrhythmic transcripts (Supplemental Figure S1B). Multi-dimensional scaling analyses showed that rhythmic transcripts were well organized according to their time points, whereas arrhythmic transcripts were not (Figure 2(a), lower panel). Heatmaps demonstrated that these two classes of transcripts were expressed rhythmically and arrhythmically, respectively (Figure 2(b)).

Figure 2.

Diurnal rhythm of polyadenylation profile in Arabidopsis. (a) Multi-dimension scales of rhythmic and arrhythmic poly(A) transcripts. Grey shadow indicates night time; (b) Heat maps illustrate the time-course expression profiles of rhythmic and arrhythmic poly(A) transcripts; (c) Venn diagram of genes producing rhythmic poly(A) transcripts (RTG), genes producing arrhythmic poly(A) transcripts (ATG), and APA genes. The rhythm of genes involved in important biological processes is shown by Z-scores of expression level (dots). Expression trends along with time-course are performed by the ‘loess’ method. Standard deviations are shown by subjective coloured shadows. Gene models and identified polyadenylation sites are marked with coloured lines on genes

In total, we identified 30,772 highly confidential poly(A) transcripts (reads >10, at least one-time point), which were distributed into 32.63% rhythmic transcripts and 67.37% arrhythmic transcripts. The Venn diagram shows that 41.6% (3284 + 481) of rhythmic transcript genes (RTG) and 45.74% (3284 + 3207) of arrhythmic transcript genes (ATG) were APA genes (Figure 2(c)). Additionally, 3284 genes were overlapped by RTG and ATG (designated as asynchronous genes), indicating that these genes produce both rhythmic and arrhythmic transcripts by APA. NRT1.1, encoding a nitrate transporter, produces a truncated 5ʹ UTR polyadenylated arrhythmic transcript and a full-length 3ʹ UTR polyadenylated rhythmic transcript. Moreover, YUCCA 9 and FLS2, which function in auxin biosynthesis and plant immunity, respectively, generate arrhythmic transcripts, and PRIN2 and BZIP63, which are involved in plastid redox signalling and regulation of circadian oscillator genes, respectively, produce rhythmic transcripts.

Collectively, PAT-seq of time-course Arabidopsis seedlings identified 3284 asynchronous genes producing both rhythmic and arrhythmic transcripts, 5765 rhythmic unique genes, and 10,906 arrhythmic unique genes (Figure 2(c)).

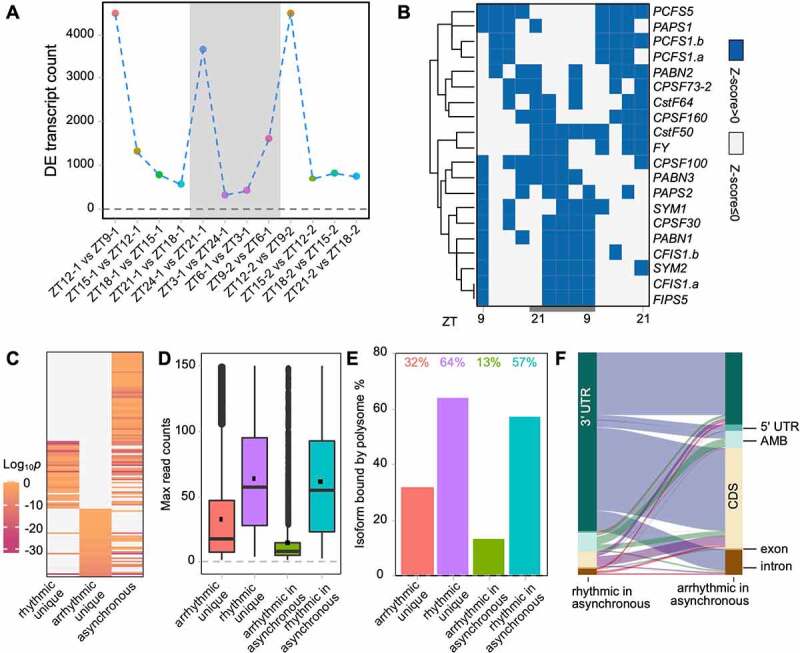

Features of diurnal polyadenylation rhythm

To investigate whether the polyadenylation process is regulated by biorhythm, RNA-seq data from public databases were reanalysed to uncover the expression of poly(A) factors in clock gene mutants. The results showed that the expression levels of 70 annotated transcripts (TAIR10), transcribed from 25 core polyadenylation machinery components, were altered at various levels in the mutants (Supplemental Figure S2). This indicates that the polyadenylation process may be regulated by the circadian clock loops. To further evaluate the polyadenylation rhythm under diurnal light/dark conditions, differential expression (DE) studies were conducted between two adjacent time points of PAT-seq. This showed that DE transcript counts fluctuate across time courses (Figure 3(a)). The count of DE transcripts is sensitive to light, which can largely increase the counts. Furthermore, we identified 20 transcripts from poly(A) factors that are rhythmically expressed, from the PAT-seq data (Figure 3(b)). All of these contain the CPSF component (CPSF30, CPSF73, CPSF100, CPSF160, and FY) transcripts. This indicates that polyadenylation may be diurnally regulated in Arabidopsis.

Figure 3.

Features of the rhythmic and arrhythmic transcripts. (a) Differential expression (DE) transcript counts along with time course. Adjacent time points are compared; (b) Heatmap of significant rhythmically expressed transcripts derived from core poly(A) factors; (c) Comparison of enriched non-redundant gene ontology terms among diverse types of genes. ‘asynchronous’ indicates genes producing both rhythmic and arrhythmic transcripts; (d) Read counts of different transcript types; (e) Percentage of transcripts found on polysome; (f) Sankey plot illustrates the source of poly(A) sites in APA genes. Each line represents a gene

Gene ontology enrichment reveals that rhythmic unique genes, arrhythmic unique genes, and asynchronous genes are functionally different (Figure 3(c) and Supplemental Table S1). For instance, rhythmic unique genes are enriched in circadian rhythm and cell redox homoeostasis, while arrhythmic unique genes are enriched in cell division and signal transduction; asynchronous genes are enriched in both photosynthesis and RNA processing.

Arrhythmic transcripts were expressed at a lower abundance than rhythmic transcripts (Figure 3(d)). Moreover, the expression levels of arrhythmic transcripts from asynchronous genes are much lower than transcripts from arrhythmic unique genes. However, there is no major difference between transcripts from rhythmic unique genes and transcripts from asynchronous genes. This raises the concern of whether arrhythmic transcripts can be translated. Thus, polysome-bound PAT-seq data prepared by immunoprecipitation of FLAG-tagged RPL18 were used to identify the translation activity of rhythmic and arrhythmic transcripts. Results showed that approximately 32% of transcripts from arrhythmic unique genes and 13% of arrhythmic transcripts from asynchronous genes could be translated, although their translation activity was lower than that of rhythmic transcripts (Figure 3(e)). This indicates that some of the arrhythmic transcripts are used in protein coding, rather than being the noise of the transcriptome.

To further understand the APA features of asynchronous genes, the Sankey plot was used to uncover the genomic location of the source of APA transcripts (Figure 3(f)). It shows that most rhythmic transcripts from asynchronous genes reside in the 3ʹ UTR. However, these 3ʹ UTR polyadenylated transcripts share the same gene sources with coding sequence (CDS) and 3ʹ UTR polyadenylated arrhythmic transcripts. In other words, asynchronous genes position APA sites between the 3ʹ UTR and CDS.

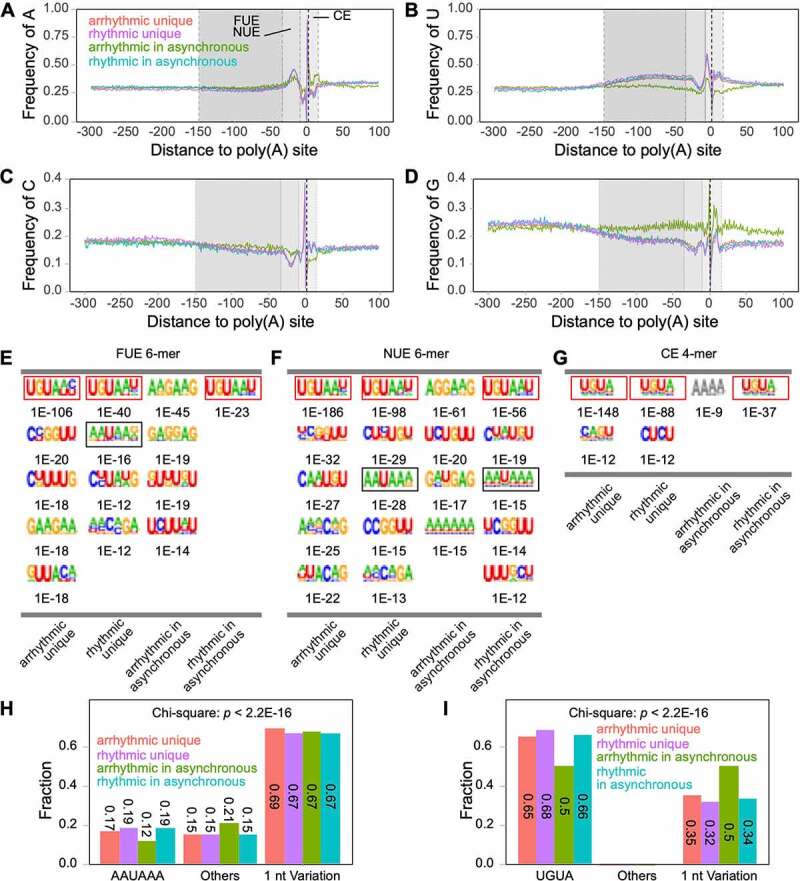

Rhythmic and arrhythmic transcripts embedded with different poly(A) signals

Poly(A) signals are crucial for polyadenylation in both animals and plants [17,18]. The nucleotide usage between 300 nt upstream of poly(A) sites and 100 nt downstream of poly(A) sites were calculated (Figure 4(a-d)). The results showed that arrhythmic transcripts from asynchronous genes have a slightly different A/C usage than the other three classes of transcripts in FUE, but have a visibly different NUE and CE poly(A) signal compared to the others (Figures 4a and 4c). The U/G usage of arrhythmic transcripts from asynchronous genes greatly differed from the others in all FUE, NUE, and CE poly(A) signals (Figures 4b and 4d). A previous study identified that upstream elements (identical to plant FUE) and poly(A) signal elements (identical to plant NUE) are predominantly 4-mer and 6-mer motifs, respectively, in animals [46,47]. Plant NUE is also predominantly composed of 6-mer motifs, whereas plant FUE is far more complex than that of an animal [18]. To distinguish the signal difference between rhythmic and arrhythmic transcripts, 6-mer FUE and NUE and 4-mer CE motifs were enriched. The results showed that the top five enriched motifs (potentially positive) of FUE, NUE, and CE differed among all four transcript classes (Figure 4(e-g)). Strikingly, three signal elements in arrhythmic transcripts from the asynchronous genes class were quite different compared to the unique classes or rhythmic transcripts from the asynchronous genes. Neither UGUA-like (red boxed) nor AAUAAA-like (black boxed) elements could be found in the arrhythmic transcripts from asynchronous genes (Figure 4(e-g)). This class only shows enriched elements with a potentially false-positive motif (grey coloured) in CE (Figure 4(g)). A common UGUA-like motif can be found in all rhythmic transcripts from asynchronous genes, rhythmic unique transcripts, and arrhythmic unique transcripts. Studies have revealed that UGUA and AAUAAA are canonical poly(A) signals upstream of the cleavage site [18,47,48]. Moreover, 1-nt variations in poly(A) signals can be efficiently recognized by protein complexes [18]. Since we can observe UGUA-like signals throughout FUE, NUE, and CE, and find AAUAAA-like signals in FUE, we searched for UGUA, AAUAAA, and their 1-nt variations from −150 nt to +15 nt around cleavage sites. The proportion of AAUAAA in arrhythmic transcripts from asynchronous genes is lower than the other three transcript classes but has a higher proportion of other unknown signals (Figure 4(h)). Moreover, it also contained less UGUA, but a higher proportion of UGUA 1-nt variation (Figure 4(i)). Chi-square tests showed that these differences were statistically significant.

Figure 4.

Rhythmic and arrhythmic transcripts have different nucleotide contents

(a-d) Single nucleotide profiles of different transcript clusters. FUE, far upstream element; NUE, near upstream element; CE, cleavage element; (e-g) Motif enrichment of FUE, NUE, and CE. Canonical signals are boxed. Enriched E-values are shown below each motif. The potentially false-positive motif is shown with grey font; (h-i) The fraction of AAUAAA and UGUA from −150 nt to +15 nt of poly(A) sites.

In conclusion, these results show that different poly(A) signals may be involved in the differentiation of rhythmic and arrhythmic transcripts from asynchronous genes.

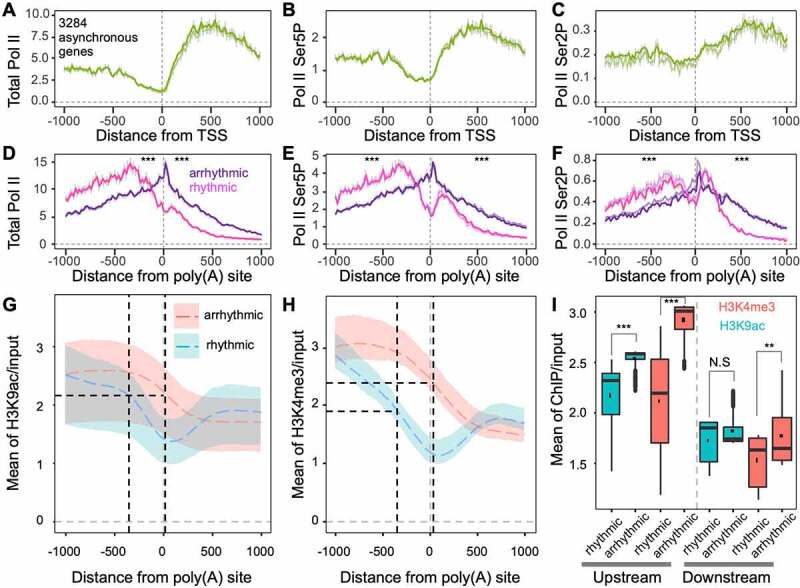

Rhythmic and arrhythmic transcripts coupled with different Pol II occupancy and histone modification

Nascent RNA-seq uses Pol II and phosphorylated Pol II antibodies to pull down nascent RNA [42,49]. It shows the profiles of Pol II and phosphorylated Pol II occupancy during co-transcription and, consequently, the termination windows of transcription. Combined with public Arabidopsis NET-seq data, we found that rhythmic unique transcripts and arrhythmic unique transcripts coupled with dramatic Pol II occupancy around transcription start sites (TSS), either total Pol II or phosphorylated Pol II (Supplemental Figure S3A, C, and E). It is reasonable to conclude that the difference in expression patterns between rhythmic unique and arrhythmic unique transcripts could be due to different transcription activities. Moreover, Pol II densities around poly(A) sites of rhythmic unique transcripts were significantly higher than arrhythmic transcripts (Supplemental Figure S3B, D, and F). Diurnal H3K9ac and H3K4me3 profiles show that both histone markers around poly(A) sites of rhythmic unique transcripts were higher than arrhythmic unique transcripts (Supplemental Figure S3G and H), reflecting the fact that the chromatin region producing rhythmic unique transcripts is more active than those producing rhythmic transcripts. Besides, the decrease in H3K9ac and H3K4me3 coincided with RNA 3ʹ-end transcription (Supplemental Figure S3G and H). They reach distinct troughs at cleavage sites, indicating the interplay between histone modification and polyadenylation.

Since 3284 genes can generate both rhythmic and arrhythmic transcripts, the study of the crosstalk between APA and the diurnal rhythms of transcripts was considered. Rhythmic transcripts and arrhythmic transcripts from asynchronous genes share the same promoter but different 3ʹ ends (Figure 5(a-f)). The total Pol II density of rhythmic transcripts reached a peak around −300 nt of poly(A) sites (Figure 5(d)). However, the total Pol II density of arrhythmic transcripts reached a peak at the poly(A) sites (Figure 5(d)). The total Pol II profiles of rhythmic and arrhythmic transcripts were significantly different upstream and downstream of poly(A) sites. These dramatic differences were also found in phosphorylated Serine 2 (Ser2P) and Serine 5 (Ser5P) Pol II profiles (Figures 5e and 5f). While the Ser2P and Ser5P profiles of rhythmic transcripts had two peaks, the profiles of arrhythmic transcripts only showed one peak at the poly(A) site (Figures 5e and 5f). The results indicate that rhythmic and arrhythmic transcripts undergo different termination mechanisms.

Figure 5.

Transcription activation histone markers are associated with rhythmic and arrhythmic transcript differentiation from the same genes. (a-c) Nascent RNA profiles around transcription start sites (TSS) of genes producing both rhythmic and arrhythmic transcripts. The y-axis indicates the mean depth of subjective Pol II occupancy; (d-f) Nascent RNA profiles around poly(A) sites of rhythmic and arrhythmic transcripts. The Wilcoxon signed-rank test was used to test differences across separate groups, either upstream or downstream of poly(A) sites. *** indicates p < 0.001; (g) H3K9ac profiles around poly(A) sites of rhythmic and arrhythmic transcripts. Black dashed vertical lines indicate the peaks of total Pol II corresponding to panel D. Coloured shadows indicate H3K9ac variation ranges corresponding to the circadian clock. The coloured dashed line indicates the mean of H3K9ac corresponding to the circadian clock; (h) H3K4me3 profiles around poly(A) sites of rhythmic and arrhythmic transcripts; (i) H3K9ac and H3K4me3 levels at upstream (−1000 to 0 bp) and downstream (0 to 1000 bp) of poly(A) sites of rhythmic and arrhythmic transcripts. ** indicates p < 0.01, N.S. indicates non-significance (p > 0.05)

By tracking H3K9ac profiles around poly(A) sites of asynchronous genes that generate rhythmic and arrhythmic transcripts, we found that the polyadenylation of rhythmic transcripts couple with a significant trough, whereas H3K9ac profiles in arrhythmic transcripts do not appear to have a trough (Figure 5(g)). This shows that when Pol II occupancy reaches a peak, the H3K9ac levels of rhythmic and arrhythmic transcripts were almost the same. Importantly, H3K9ac levels of rhythmic transcripts drop sharply after the Pol II peak; however, H3K9ac levels of arrhythmic transcripts decreased much slower. The pattern difference of H3K4me3 around poly(A) sites of rhythmic and arrhythmic transcripts is similar to that of H3K9ac (Figure 5(h)). Also, H3K4m3 levels of rhythmic transcripts were lower than those of arrhythmic transcripts, while Pol II occupancy on genes of rhythmic transcripts reached peak levels. H3K4me3 upstream of poly(A) sites in rhythmic transcripts decreased more sharply than H3K9ac. A statistical study showed that H3K9ac and H3K4me3 levels located 1 kb upstream of the poly(A) sites of rhythmic transcripts were significantly lower than those of arrhythmic transcripts (Figure 5(i)). However, H3K9ac and H3K4me3 located 1 kb downstream were not significantly different between the two classes of transcripts. To exclude whether H3K9ac and H3K4me3 around the 3ʹ end come from fragments of short genes during sonication (the 3ʹ ends are close to 5ʹ ends), the lengths of genes generating rhythmic and arrhythmic transcripts were calculated (Supplemental Figure S4). The median length of genes generating both rhythmic and arrhythmic transcripts is 2324 bp, which indicates that H3K9ac and H3K4me3 occupancy on the 3ʹ end of genes is independent of transcription start.

Herein, H3K9ac and H3K4me3 histone markers may be involved in orchestrating Pol II occupancy density and in differentiating rhythmic and arrhythmic APA events.

Discussion

PAT-seq identifies bi-dimensional diurnal rhythm landscape

Diurnal or circadian rhythm is a common feature in most eukaryotes and plays a vital role in various biological processes [1,50,51]. Previous studies have utilized microarrays and identified about 10–30% of Arabidopsis mRNAs and about 10–15% of mammalian mRNAs that are expressed in a diurnal/circadian rhythm [5,52–54]. Using RNA-seq, a recent study found that 1446 APA events are regulated by diurnal rhythms under light/dark cycling conditions [55]. However, microarrays can only identify a small set of known genes, and the arrays remain incomplete [56]. Besides, some weakly expressed genes cannot be detected by microarray analysis [57]. Although high-throughput RNA-seq has been applied to circadian rhythm studies [7,8,58–60], the identification of transcript isoforms depends on a well-annotated transcriptome and genome. Moreover, it is difficult to precisely map poly(A) sites because of read coverage bias at the 3ʹ end of transcripts [61].

PAT-seq is an efficient method for genome-wide profiling of mature transcript expression and poly(A) site locations, both in plants and animals [26,62]. In this study, we adopted PAT-seq for rhythmic transcript expression and APA studies. The method produced credible indicators of diurnal expression levels of genes and their transcripts involved in transcription rhythm regulation (Supplemental Figure S1A). Our results show that 10,041 transcripts from 9049 genes are presented with a significant rhythmic pattern within the Arabidopsis Col-0 CS60000 strain (Figure 2(b)). The number of rhythmic transcripts is far more than the ~1600 genes identified by microarray [63]. Hence, combined with time-course sampling, PAT-seq could simultaneously and bi-dimensionally uncover APA and diurnal rhythm information.

Diurnal polyadenylation rhythm in Arabidopsis

APA has been reported to play a role in rhythmic gene expression in eukaryotes [33–36]. However, the relationship between diurnal rhythm and polyadenylation has never been studied in detail at the genome-wide level. We identified that Arabidopsis mRNA contains approximately 1/3 rhythmic and 2/3 arrhythmic polyadenylated transcripts in this study and that each class contains genes involved in important biological processes (Figure 2). Pairwise time course comparisons among our PAT-seq data showed that several DE polyadenylated transcripts fluctuated over time (Figure 3(a)), which demonstrates that polyadenylation rhythm is common at the genome-wide level. Hence, the DE counts at light transition times are dramatically higher than those at other points, meaning that light input largely affects the polyadenylation rhythm. A frequently asked question is whether those low-expressed or all APA isoforms can be translated. The answer is yes, as proven in a previous study [64]. By integrating these published data and our diurnal PAT-seq data, we further proved that the translational activities of rhythmic and arrhythmic transcripts were different (Figure 3(e)).

Genes of rhythmic and arrhythmic unique transcripts and APA genes producing both rhythmic and arrhythmic transcripts were functionally different (Figure 3(c)). This indicates that different diurnal rhythmic types of transcripts undergo different transcriptional regulation mechanisms. For example, genes that only produce rhythmic transcripts coupled with a higher transcription activity are orchestrated at higher transcription activation histone markers than genes that only produce arrhythmic transcripts (Figure 3(d) and Supplemental Figure S3). A common manifestation is that the cleavage site of polyadenylation coincides with the trough of histone markers from the −1 kb to 1 kb window of poly(A) sites (Supplemental Figure S3C and H), which indicates that the erasure of H3K9ac and H3K4me3 may promote polyadenylation.

Differentiation of rhythmic and arrhythmic transcripts on APA genes

As mentioned above, we found that 3284 APA genes can generate both rhythmic and arrhythmic transcripts. This gene class is a valuable resource for studying the interplay between APA and the diurnal rhythm of transcripts. In this case, most of the APAs were found between the 3ʹ UTR and CDS (Figure 3(f)). The poly(A) signals of rhythmic and arrhythmic transcripts from asynchronous genes are different, which the arrhythmic parts do not embed with canonical poly(A) signals (Figure 4). This indicates that different polyadenylation efficiencies may result in different expression patterns (Figure 3(d)) since Pol II abundance differences (Figure 5(a-f)) are not as large as those between rhythmic unique and arrhythmic unique transcripts (Supplemental Figure S3A-F). The H3K9ac and H3K4me3 dropping rates were different between rhythmic and arrhythmic transcripts (Figure 5(d-f)). The start of H3K9ac and H3K4me3 decreasing sites in rhythmic transcripts coincided with the peak of Pol II densities (Figure 5(d-h)). However, H3K9ac and H3K4me3 still maintain elevated levels, which may promote a continuous increase in the Pol II density of arrhythmic transcripts. Remarkably, a trough in the histone modification profile is only present in rhythmic transcripts from asynchronous genes (Figures 5g and 5h), which further proves that the erasure of H3K9ac and H3K4me3 promotes polyadenylation efficiency. Furthermore, the H3K9ac and H3K4me3 levels in the −1 kb windows of rhythmic transcripts are significantly lower than those of arrhythmic transcripts from asynchronous gene clusters (Figures 5g and 5h). This is quite different from the difference between rhythmic and arrhythmic transcripts from unique genes (Supplemental Figure S3G and H).

Studies have suggested the potential role of histone modification in polyadenylation, where nucleosome organization is severely affected by these histone markers [38,65]. We recently proved that histone deacetylation functions in 3ʹ-end processing [39]. Taken together with the difference in poly(A) signals, histone modifications are involved in orchestrating Pol II occupancy profiles and synergistically determining the cleavage position for polyadenylation. This may be a part of the mechanisms used in the differentiation of rhythmic and arrhythmic transcripts in APA genes. Thus, the differentiation of rhythmic and arrhythmic transcripts on APA genes is a systematic regulatory network orchestrated from chromatin to mRNA. Further high-throughput sequencing, biochemical, and genetic studies would be valuable in the investigation of other histone markers’ roles in polyadenylation and will enhance the understanding of the mechanisms of rhythmic and arrhythmic transcript differentiation from APA genes.

Material and methods

Plant materials, growth conditions and RNA isolation

Wild type (Columbia-0, Col-0 ecotype), oxt6 (an AtCPSF30 knockout mutant, Col-0 ecotype) [66], esp5 (a point mutation of AtCPSF100, C24 ecotype) and its control transgenic plant amp311 (designated as CK in this study, also C24 ecotype) [67] seeds were surface sterilized and synchronized in the dark for 3 days at 4°C. Then, seeds were sown on ½ MS medium with 0.8% phytagel and kept vertical growth for 6 days. To avoid light or dark stress, growth chamber condition was set to 12 h/12 h period of light/dark (120 μmol m−2 s−1, at 9:00 am light on) at 22°C. On the 7th day, seedlings were harvested every 3 h starting from 9:00 am until 9:00 pm on the 8th day (Figure 2(a), upper panel). Total RNA from three biological replicates (∼10 plants each) was extracted using the TRIzol reagent (Invitrogen), and treated with DNase I (Takara) following RNA purification. Qualified total RNA was used for PAT-seq libraries construction.

RT-qPCR

Total RNAs of wild type, oxt6, esp5 and CK were isolated as described above and subjected to cDNA synthesis using a first-strand cDNA synthesis kit (Applied Biological Materials Inc, ABM). qPCR was performed on Bio-Rad CFX96 Real-Time instrument by SYBR Premix Ex Taq II fluorescent dye (Roche). UBQ10 was chosen as a housekeeping reference gene for the normalization of expression. Primers designed before proximal poly(A) sites could quantify the transcript levels of gene including all the transcripts, while the primers after proximal poly(A) sites could accurately amplify transcripts using distal poly(A) sites. All primer sequences used in this study are listed in Supplemental Table S2. Three independent biological replicates and three technical repetitions were performed in all experiments.

PAT-seq library preparation and sequencing

PAT-seq libraries were prepared as described [39]. Briefly, 2 µg of qualified total RNA was fragmented at 94°C for 4 min with 5 × first strand buffer (Invitrogen). Poly(A) tags were enriched with oligo(dT)25 magnetic beads (New England Biolabs). Reverse transcription and template switching was performed with barcoded oligo(dT)18 primers and Locked Nucleic Acid (LNA™) modified 5ʹ adaptor by SMARTSCRIBE (Clontech), respectively. Generated cDNA was purified by AMPURE® XP beads (Beckman) and amplified by Phire II (Thermo Fisher Scientific). Quality of PAT-seq libraries was examined on Agilent Bioanalyzer 2100, Qubit 2.0 and qPCR. Qualified libraries were sequenced on Illumina HiSeq 2500 platform at the facility located in the College of the Environment and Ecology, Xiamen University.

PAT-seq data processing

The raw reads were quality filtered by FASTX-Toolkit (Version 0.0.14, parameters‘-q 20 -p 50 -v -Q 33’). A custom perl script was then used to trim barcodes and poly(T) stretches at the 5ʹ of reads. The clean reads were aligned to Arabidopsis reference genome (The Arabidopsis Information Resource, TAIR10, www.arabidopsis.org) by Bowtie2 software (Version 2.1.0, parameters ‘-L 25 -N 1 -i S,1,1.15 – no-unal’). The first biological repeat of 12 am sample on the 8th day was excluded due to low mapping rate (31.41%). Internal priming reads were filtered out and poly(A) sites were identified by a 24 nt interval clustering according to our previous publication [68]. A poly(A) site with at least one time point with more than 10 reads was considered as a high confidential poly(A) site and was used for further analyses.

DESeq2 package (version 1.26.0) was used to normalize reads and compare differential expression poly(A) sites between neighbouring time points. An adjusted p-value (padj) <0.05 was used as a cut-off for differentially expressed poly(A) sites.

The sequences surrounding poly(A) sites ranging from −300 to +100 nt were extracted for single nucleotide profile analysis as previously reported [18]. Homer2 (version 4.11) was used to enrich poly(A) signals in FUE regions (−150 ~ −35 nt from the poly(A) site), NUE regions (−35 ~ −10 nt from the poly(A) site), and CE regions (−10 ~ +15 nt from the poly(A) site), respectively. Top 5 and potential positive motifs were adopted in this study. In addition, the canonical UGUA, AAUAAA signal and their 1-nt variants were analysed from −150 ~ +15 nt of poly(A) sites.

Flag tagged RPL18 pull down PAT-seq data of wild type was download from NCBI SRA database under projects of PRJNA343037. Data processing was according to methods described above.

Rhythmicity detection by MetaCycle

To identify diurnal rhythm of transcripts and genes, the MetaCycle R package [45] was applied to identify diurnal rhythm of transcripts. Benjamini Hochberg p values <0.05 threshold was considered as statistically significant rhythmic transcripts.

Gene Ontology enrichment

Genes were submitted to Agrigo2 (http://systemsbiology.cau.edu.cn/agriGOv2/) for Gene Ontology enrichment. The subjective results were submitted to Revigo (http://revigo.irb.hr/) for removing redundant terms. Non-redundant terms were preserved for further comparison.

Data analysis of circadian factor mutants

RNA-seq datasets of circadian mutants were downloaded from NCBI SRA database under projects of SRP082192 and SRP108492. Transcription expression values were identified by Kallisto 0.44.0 version [69] with ‘quant’ mode. Transcript models are according to TAIR10 annotation. Expression data of poly(A) factors were extracted for plotting according to the list from previous publication [21].

Plant nascent RNA-seq data processing

Pre-processed Bed format files of GSE109974 and GSE117014 (GEO accessions) are kindly provided by Prof. Zhicheng Dong’s group. Read densities were normalized to the same reads counts. Coordinates of TSS and poly(A) sites are extracted according to transcript clusters. The subjective Pol II densities were mapped to −1 kb and 1 kb windows of TSS and poly(A) sites. Mean values of transcripts and two replicates were dependently plotted on figures. Standard error bars were shown on line plots.

ChIP-seq data processing

Raw reads of SRP152291 were downloaded and quality controlled by fastp (version 0.19.6) with q20 option. Clean reads are mapped to TAIR10 genome by bowtie2 and PCR duplicates were removed. BAM files of replicates were merged for further processing. deepTools (version 3.1.3) was used to normalize BAM files by RPGC option (1X coverage depth) and convert to bigwig formats. bigwigCompare function in deepTools was then used to normalize ChIP samples to inputs, and ratio of ChIP/input was calculated. Mean values of H3K9ac and H3K4me3 across all time points were calculated for visualization.

Acknowledgments

We thank Zhicheng Dong’s group from Guangzhou University that provided nascent RNA-seq data. We also thank Haidong Qu, Xiuxiu Wang, Xiaoxuan Zhou, and Wenjia Lu for technical assistance, Taylor Li and Taylor & Francis Editing Services for language editing.

Funding Statement

This work was supported in part by National Natural Science Foundation of China [31671318], [32000448] and [61802323], Fundamental Research Funds for the Central Universities [20720190106], a grant from the U.S. National Science Foundation [IOS-154173], and grants from China Postdoctoral Science Foundation [2017M620274, 2018T110649]; National Science Foundation [IOS-154173]; Postdoctoral Research Foundation of China [2017M620274]; Postdoctoral Research Foundation of China [2018T110649];

Notes on contributors

QQL, JL, ZY and LH designed the research. ZY performed wet lab experiments. LH and YC contributed to material preparation. JL, ZY, CY, QQL and YS performed data analysis. JL, ZY, and QQL wrote and revised the manuscript.

Availability statement

The PAT‐seq data have been deposited in the BioProject database at NCBI (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/bioproject/) under accession number PRJNA559744.

Disclosure of potential conflicts of interest

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

References

- [1].Nohales MA, Kay SA.. Molecular mechanisms at the core of the plant circadian oscillator. Nat Struct Mol Biol. 2016;23(12):1061–1069. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].Torres M, Becquet D, Franc JL, et al. Circadian processes in the RNA life cycle. Wiley Interdiscip Rev RNA. 2018;9(3):e1467. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Greenham K, McClung CR.. Integrating circadian dynamics with physiological processes in plants. Nat Rev Genet. 2015;16(10):598–610. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Schaffer R, Landgraf J, Accerbi M, et al. Microarray analysis of diurnal and circadian-regulated genes in Arabidopsis. Plant Cell. 2001;13(1):113–123. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Blasing OE, Gibon Y, Gunther M, et al. Sugars and circadian regulation make major contributions to the global regulation of diurnal gene expression in Arabidopsis. Plant Cell. 2005;17(12):3257–3281. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Filichkin SA, Breton G, Priest HD, et al. Global profiling of rice and poplar transcriptomes highlights key conserved circadian-controlled pathways and cis-regulatory modules. PLoS One. 2011;6(6):e16907. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Higashi T, Aoki K, Nagano AJ, et al. Circadian oscillation of the lettuce transcriptome under constant light and light-dark conditions. Front Plant Sci. 2016;7:1114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Kim JA, Shim D, Kumari S, et al. Transcriptome analysis of diurnal gene expression in Chinese cabbage. Genes (Basel). 2019;10(2):10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Oakenfull RJ, Davis SJ. Shining a light on the Arabidopsis circadian clock. Plant Cell Environ. 2017;40(11):2571–2585. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Nagel DH, Kay SA. Complexity in the wiring and regulation of plant circadian networks. Curr Biol. 2012;22(16):R648–R57. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Locke JC, Kozma-Bognar L, Gould PD, et al. Experimental validation of a predicted feedback loop in the multi-oscillator clock of Arabidopsis thaliana. Mol Syst Biol. 2006;2(1):59. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].Nakamichi N, Kiba T, Henriques R, et al. PSEUDO-RESPONSE REGULATORS 9, 7, and 5 are transcriptional repressors in the arabidopsis circadian clock. Plant Cell. 2010;22(3):594–605. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Farre EM, Harmer SL, Harmon FG, et al. Overlapping and distinct roles of PRR7 and PRR9 in the Arabidopsis circadian clock. Curr Biol. 2005;15(1):47–54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].Herrero E, Kolmos E, Bujdoso N, et al. EARLY FLOWERING4 recruitment of EARLY FLOWERING3 in the nucleus sustains the Arabidopsis circadian clock. Plant Cell. 2012;24(2):428–443. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].Brown SA, Kowalska E, Dallmann R. (Re)inventing the circadian feedback loop. Dev Cell. 2012;22(3):477–487. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].Saini R, Jaskolski M, Davis SJ. Circadian oscillator proteins across the kingdoms of life: structural aspects. BMC Biol. 2019;17:13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].Tian B, Manley JL. Alternative polyadenylation of mRNA precursors. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2017;18(1):18–30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18].Loke JC, Stahlberg EA, Strenski DG, et al. Compilation of mRNA polyadenylation signals in Arabidopsis revealed a new signal element and potential secondary structures. Plant Physiol. 2005;138(3):1457–1468. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [19].Shi Y. Alternative polyadenylation: new insights from global analyses. RNA. 2012;18(12):2105–2117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [20].Shi Y, Manley JL. The end of the message: multiple protein-RNA interactions define the mRNA polyadenylation site. Gene Dev. 2015;29(9):889–897. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [21].Hunt AG, Xu R, Addepalli B, et al. Arabidopsis mRNA polyadenylation machinery: comprehensive analysis of protein-protein interactions and gene expression profiling. BMC Genomics. 2008;9(1):220. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [22].Thomas PE, Wu X, Liu M, et al. Genome-wide control of polyadenylation site choice by CPSF30 in Arabidopsis. Plant Cell. 2012;24(11):4376–4388. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [23].Lin J, Xu R, Wu X, et al. Role of cleavage and polyadenylation specificity factor 100: anchoring poly(A) sites and modulating transcription termination. Plant J. 2017;91(5):829–839. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [24].Zhao Z, Wu X, Kumar PKR, et al. Bioinformatics analysis of alternative polyadenylation in green alga chlamydomonas reinhardtii using transcriptome sequences from three different sequencing platforms. G3 (Bethesda). 2014;4(5):871–883. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [25].Zhou X, Zhang Y, Michal JJ, et al. Alternative polyadenylation coordinates embryonic development, sexual dimorphism and longitudinal growth in Xenopus tropicalis. Cell Mol Life Sci. 2019;76(11):2185–2198. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [26].Fu H, Yang D, Su W, et al. Genome-wide dynamics of alternative polyadenylation in rice. Genome Res. 2016;26(12):1753–1760. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [27].Wu X, Gaffney B, Hunt AG, et al. Genome-wide determination of poly(A) sites in Medicago truncatula: evolutionary conservation of alternative poly(A) site choice. BMC Genomics. 2014;15(1):615. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [28].Zhu S, Wu X, Fu H, et al. Modeling of genome-wide polyadenylation signals in Xenopus tropicalis. Front Genet. 2019;10:647. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [29].Chakrabarti M, Dinkins RD, Hunt AG. Genome-wide atlas of alternative polyadenylation in the forage legume red clover. Sci Rep. 2018;8(1):11379. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [30].Xing D, Li QQ. Alternative polyadenylation and gene expression regulation in plants. Wiley Interdiscip Rev RNA. 2011;2(3):445–458. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [31].Deng X, Cao X. Roles of pre-mRNA splicing and polyadenylation in plant development. Curr Opin Plant Biol. 2017;35:45–53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [32].Chen W, Jia Q, Song Y, et al. Alternative polyadenylation: methods, findings, and impacts. Genomics Proteomics Bioinformatics. 2017;15(5):287–300. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [33].Xing D, Wang Y, Xu R, et al. The regulatory role of Pcf11-similar-4 (PCFS4) in Arabidopsis development by genome-wide physical interactions with target loci. BMC Genomics. 2013;14(1):598. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [34].Liu Y, Hu W, Murakawa Y, et al. Cold-induced RNA-binding proteins regulate circadian gene expression by controlling alternative polyadenylation. Sci Rep. 2013;3(1):2054. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [35].Gendreau KL, Unruh BA, Zhou C, et al. Identification and Characterization of transcripts regulated by circadian alternative polyadenylation in mouse liver. G3 (Bethesda). 2018;8(11):3539–3548. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [36].Ptitsyna N, Boughorbel S, El Anbari M, et al. The role of alternative Polyadenylation in regulation of rhythmic gene expression. BMC Genomics. 2017;18(1):576. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [37].Song Q, Huang TY, Yu HH, et al. Diurnal regulation of SDG2 and JMJ14 by circadian clock oscillators orchestrates histone modification rhythms in Arabidopsis. Genome Biol. 2019;20(1):170. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [38].Lee C-Y, Chen L. Alternative polyadenylation sites reveal distinct chromatin accessibility and histone modification in human cell lines. Bioinformatics. 2013;29(14):1713–1717. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [39].Lin J, Hung FY, Ye C, et al. HDA6-dependent histone deacetylation regulates mRNA polyadenylation in Arabidopsis. Genome Res. 2020;30(10):1407–1417. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [40].Wang J, Zhao Y, Zhou X, et al. Nascent RNA sequencing analysis provides insights into enhancer-mediated gene regulation. BMC Genomics. 2018;19(1):633. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [41].Kurup JT, Kidder BL. Identification of H4K20me3- and H3K4me3-associated RNAs using CARIP-Seq expands the transcriptional and epigenetic networks of embryonic stem cells. J Biol Chem. 2018;293(39):15120–15135. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [42].Nojima T, Al E, Grosso A. Mammalian NET-seq reveals genome-wide nascent transcription coupled to RNA processing. Cell. 2015;161(3):526–540. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [43].Kamieniarz-Gdula K, Gdula MR, Panser K, et al. Selective roles of Vertebrate PCF11 in premature and full-length transcript termination. Mol Cell. 2019;74(158–72.e9):158–172.e9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [44].Ma L, Pati PK, Liu M, et al. High throughput characterizations of poly(A) site choice in plants. Methods. 2014;67(1):74–83. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [45].Wu G, Anafi RC, Hughes ME, et al. MetaCycle: an integrated R package to evaluate periodicity in large scale data. Bioinformatics. 2016;32(21):3351–3353. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [46].Elkon R, Ugalde AP, Agami R. Alternative cleavage and polyadenylation: extent, regulation and function. Nat Rev Genet. 2013;14(7):496–506. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [47].Li W, You B, Hoque M, et al. Systematic profiling of poly (A)+ transcripts modulated by core 3ʹend processing and splicing factors reveals regulatory rules of alternative cleavage and polyadenylation. PLoS Genet. 2015;11(4):e1005166. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [48].Neve J, Burger K, Li W, et al. Subcellular RNA profiling links splicing and nuclear DICER1 to alternative cleavage and polyadenylation. Genome Res. 2016;26(1):24–35. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [49].Zhu J, Liu M, Liu X, et al. RNA polymerase II activity revealed by GRO-seq and pNET-seq in Arabidopsis. Nat Plants. 2018;4(12):1112–1123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [50].Maury E, Ramsey KM, Bass J. Circadian rhythms and metabolic syndrome: from experimental genetics to human disease. Circ Res. 2010;106(3):447–462. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [51].Seney ML, Cahill K, Enwright JF, et al. Diurnal rhythms in gene expression in the prefrontal cortex in schizophrenia. Nat Commun. 2019;10(1):3355. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [52].Harmer SL, Hogenesch JB, Straume M, et al. Orchestrated transcription of key pathways in Arabidopsis by the circadian clock. Science. 2000;290(5499):2110–2113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [53].Vollmers C, Gill S, DiTacchio L, et al. Time of feeding and the intrinsic circadian clock drive rhythms in hepatic gene expression. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2009;106(50):21453–21458. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [54].Lowrey PL, Takahashi JS. Mammalian circadian biology: elucidating genome-wide levels of temporal organization. Annu Rev Genomics Hum Genet. 2004;5(1):407–441. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [55].Yang Y, Li Y, Sancar A, et al. The circadian clock shapes the Arabidopsis transcriptome by regulating alternative splicing and alternative polyadenylation. J Biol Chem. 2020;295(22):7608–7619. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [56].Duffield GE. DNA microarray analyses of circadian timing: the genomic basis of biological time. J Neuroendocrinol. 2003;15(10):991–1002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [57].Nadon R, Shoemaker J. Statistical issues with microarrays: processing and analysis. Trends Genet. 2002;18(5):265–271. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [58].Muller NA, Wijnen CL, Srinivasan A, et al. Domestication selected for deceleration of the circadian clock in cultivated tomato. Nat Genet. 2016;48(1):89–93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [59].Zhang R, Lahens NF, Ballance HI, et al. A circadian gene expression atlas in mammals: implications for biology and medicine. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2014;111(45):16219–16224. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [60].Hughes ME, Grant GR, Paquin C, et al. Deep sequencing the circadian and diurnal transcriptome of Drosophila brain. Genome Res. 2012;22(7):1266–1281. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [61].Pickrell JK, Marioni JC, Pai AA, et al. Understanding mechanisms underlying human gene expression variation with RNA sequencing. Nature. 2010;464(7289):768–772. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [62].Ni T, Majerciak V, Zheng ZM, et al. PA-seq for global identification of RNA polyadenylation sites of kaposi’s sarcoma-associated herpesvirus transcripts. Curr Protoc Microbiol. 2016;41(1):14E.7.1–E.7.8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [63].Covington MF, Harmer SL. The circadian clock regulates auxin signaling and responses in Arabidopsis. PLoS Biol. 2007;5:e222. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [64].De Lorenzo L, Sorenson R, Baileyserres J, et al. Noncanonical alternative polyadenylation contributes to gene regulation in response to hypoxia. Plant Cell. 2017;29(6):1262–1277. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [65].Huang H, Chen J, Liu H, et al. The nucleosome regulates the usage of polyadenylation sites in the human genome. BMC Genomics. 2013;14(1):912. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [66].Zhang J, Addepalli B, Yun KY, et al. A polyadenylation factor subunit implicated in regulating oxidative signaling in Arabidopsis thaliana. PloS One. 2008;3(6):e2410. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [67].Herr AJ, Molnar A, Jones A, et al. Defective RNA processing enhances RNA silencing and influences flowering of Arabidopsis. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2006;103(41):14994–15001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [68].Wu X, Liu M, Downie B, et al. Genome-wide landscape of polyadenylation in Arabidopsis provides evidence for extensive alternative polyadenylation. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2011;108(30):12533–12538. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [69].Bray NL, Pimentel H, Melsted P, et al. Near-optimal probabilistic RNA-seq quantification. Nat Biotechnol. 2016;34(5):525–527. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The PAT‐seq data have been deposited in the BioProject database at NCBI (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/bioproject/) under accession number PRJNA559744.