Abstract

Purpose

Parent report was compared to judgments made by a trained researcher to determine the utility of the Vocal Development Landmarks Interview (VDLI) for monitoring development of vocal behaviors in very young children.

Method

Parents of 40 typically developing children, ages 6–21 months, provided full-day naturalistic audio recordings of their children's vocalizations after completing the VDLI. Six 5-min segments of highly voluble periods were selected from each recording and were analyzed, coded, and scored by the researcher. These data were then compared to the parents' VDLI responses. Parent–researcher agreement was examined using two methods and a generalized linear mixed model. Patterns of disagreement were explored descriptively to gain insights regarding potential sources of parent–researcher differences. Finally, developmental patterns in the researcher-observed vocal behaviors were examined as a function of children's age.

Results

No significant differences in parent–researcher agreement were found for the Canonical and Word subscales of the VDLI; however, significant differences in agreement were found for the Precanonical subscale. Mean percentages of agreement were high overall for both scoring methods evaluated. Additionally, the researcher's categorization and quantification of vocal behaviors for each age group aligned well with developmental trajectories found in the literature.

Conclusion

Results provide further support for use of parent report to assess early vocal development and use of the VDLI as a clinical measure of vocal development in infants and toddlers ages 6–21 months.

Infants' prelinguistic vocalizations serve an important role in facilitating the development of early speech and spoken language skills. Long before uttering their first words, infants progress through a series of predictable vocal stages that lay the foundation for the production of meaningful speech (Oller et al., 1999; Stark, 1980; Vihman et al., 1985). However, for children at risk for developmental delays (e.g., children with Down syndrome, hearing loss, autism, cerebral palsy, cleft palate), this predictable pattern of vocal development may be disrupted or delayed. If not detected early enough, such delays could have cascading effects, impacting later stages of language and communicative development. Although significant advancements have been made in early detection and intervention of language-related problems, there is still a need for sensitive and clinically valid tools to screen and monitor the prelexical vocal development of young children (Kishon-Rabin et al., 2005; Moeller et al., 2011). Such information has the potential to guide early intervention teams in detecting communication and language deviations and delays as early as possible and evaluating the functional effectiveness of early intervention strategies.

While many tools currently exist for use in assessing the early communication and language skills of young children, most give limited attention to the prelexical vocal stages of development and, instead, focus more on symbolic gestures and the comprehension and production of words. Additionally, many comprehensive communication and language assessment tools are designed for use in a research context and often rely on methods that are costly, time consuming, and labor intensive (e.g., video/audio recordings, phonetic transcription, coding of language behaviors). However, the monitoring of infants' prelexical vocal development has relevance beyond the research context, including clinical and home/community-based early intervention settings, and therefore requires tools that are designed with these contexts in mind. Ideally, a practical measure of vocal development would incorporate a comprehensive set of vocal behaviors that captures the full continuum of prelexical vocalizations and early lexical development (from prebabble to early word stages) to serve as a guide for practitioners in tracking major vocal milestones and forecasting next steps in early intervention. Despite the importance and value of such a measure, the direct assessment of children's vocal development presents a number of methodological challenges, including infants' limited attention and cooperation, possible fear of strangers and unfamiliar testing environments, and limited or variable language skills (Fenson et al., 2000). Such factors often prevent researchers and practitioners from gathering timely, reliable, and/or valid information about infants' vocal development (Kishon-Rabin et al., 2005). However, one useful alternative to addressing these challenges is the use of parent report in assessment. The objective of the current study was to compare parent report on a measure of infant vocal development (the Vocal Development Landmarks Interview [VDLI]) to researcher judgment of infant vocalizations to determine the utility of parent report for monitoring infants' development of vocal behaviors.

Parent Report in Assessment

Parents are in a unique position to provide insights regarding their children's developmental status and level of functioning in naturalistic settings. In addition to being their children's first and most significant teachers, parents have extensive knowledge of their children's behaviors and skills. Parents can provide comprehensive and accurate estimates of their children's abilities and performance based on their daily interactions (Dale, 1991; Dale et al., 1989; Squires & Bricker, 2009), and parental observations are often used to validate the findings of other assessments (Division for Early Childhood, 2007). Parents' ability to recognize changes in their children's behaviors and skills over time also makes parent report especially valuable when evaluating the development of young children (Lyytinen et al., 1996; Oller et al., 2001; Ramsdell-Hudock et al., 2018). Furthermore, unlike direct testing, which tends to be expensive, time consuming, and lacking in ecological validity (Lichtenstein, 1984; Rescorla & Alley, 2001), parent report tends to hold high ecological validity and is relatively inexpensive.

The extant literature indicates that parent report is used widely throughout the medical, clinical, and educational communities. Several studies have confirmed the value of parent report in detecting problems and delays in young children's development, learning, and behaviors (Glascoe, 1999a; Pulsifer et al., 1994; Squires & Bricker, 2009). Within the field of pediatrics, eliciting parental concerns has been identified as a primary method of developmental surveillance and screening (Poon et al., 2010). A meta-analysis conducted by Glascoe (1999b) examined the value of parents' concerns in detecting developmental and behavioral problems and revealed that, on average, parents were reliable reporters of their children's development and behavioral status, regardless of education, socioeconomic status, and child-rearing experience. Additionally, several studies have reported the use of parent report tools in pediatrician offices and home visits as being an efficient, valid, and cost-effective alternative to the use of developmental screening tools completed by medical personnel (McKnight, 2014; Poon et al., 2010; Schonwald et al., 2009; Sices et al., 2008).

Parent report is also considered a valuable methodological approach for assessing children's linguistic and auditory development and a promising tool for assessing children's early vocal development. With regard to language development, some argue that it is more representative of young children's abilities than laboratory samples (Dale, 1991; Feldman et al., 2005). Moderate-to-high correlations have been found between parent report of language skills and standardized assessments or structured language samples for children between the ages of 2 and 3 years (Feldman et al., 2005; Rescorla & Alley, 2001; Ring & Fenson, 2000; Wetherby et al., 2002). Likewise, strong correlations have been found between parent report of preverbal and verbal communication skills and video-recorded observations of those same skills with children as young as 7–30 months of age (Karousou & Nikolaidou, 2015). Strong psychometric properties of some of the most commonly used parent report measures of children's language abilities provide further evidence for the validity of parent report in assessing early linguistic development in children (e.g., Fenson et al., 2007, 1993, 1994; Law & Roy, 2008; Wetherby et al., 2002). Similarly, several parent report questionnaires of early auditory abilities have been developed and numerous studies have shown that parents can provide accurate reports of their children's auditory responses and functional listening skills using such measures (Bagatto & Scollie, 2013; Ben-Itzhak et al., 2014; Coninx et al., 2009; May-Mederake et al., 2010; Robbins et al., 1991).

Although studies focused specifically on parent report of early vocal development are more limited, they have generally been promising. Parent report has proven to be particularly useful in identifying the onset of canonical babbling in infants as young as 8 months of age (Oller, 1980, 2000; Oller et al., 1999, 2001) and the repertoire of syllables regularly produced by infants in babbling (Ramsdell et al., 2012). In a series of studies, Oller et al. (1999, 2001) found that regardless of education, ethnicity, or socioeconomic status, over 90% of parents were able to accurately report the onset of their children's canonical babbling with no or little training. In a study by Ramsdell-Hudock et al. (2018), the number of utterances and phonetic segments produced by infants per parent report were found to increase significantly with age and follow the expected developmental trajectory.

Less is known about parents' ability to report on the earliest aspects of infant vocal development (e.g., vocal behaviors beginning as early as 6 months of age). Only a limited number of studies have examined whether parents can accurately identify some of the earliest types of vocal productions (e.g., vowel glides, bilabial fricatives, and marginal syllables) and distinguish between these various vocalization types (Ambrose et al., 2016; Cantle Moore, 2014; Karousou & Nikolaidou, 2015; Kishon-Rabin et al., 2005; Moeller et al., 2019). It remains unclear whether parents can identify nuanced early vocal behaviors or if the saliency and frequency of early emerging vocal productions influence parents' accuracy in reporting on these behaviors. Unlike the transition from vowels to canonical syllables in which there is a clear, recognizable change in a child's ability to produce well-formed phones and syllables (Oller, 1980), the transition from early vowel-like vocalizations to true vowels may not be as noticeable and, therefore, may be difficult for parents to identify and accurately report. In addition, some vocal behaviors may occur infrequently, potentially making them difficult for parents to notice. Conversely, some behaviors may be so expected that parents report on them indiscriminately, rendering them insensitive.

Although parent report is typically considered a useful method for assessing the development of young children across developmental domains, there have been concerns raised about the accuracy of parent report and the potential for biased reporting. However, Dale et al. (1989) argue that such limitations can be overcome with the use of specific practices to optimize the reliability and validity of parent report, for example, using a recognition format rather than simple recall and assessing behaviors that are currently occurring (not retrospective), newly emerging, and relatively frequent. Similarly, Feldman et al. (2000) suggested providing training to parents to improve the accuracy of parent report, especially when the behaviors being queried require subjective judgments of their observations.

The Vocal Development Landmarks Interview

In an effort to address the need for an efficient, clinically valid, and reliable method for assessing infants' earliest vocal behaviors, Moeller et al. (2019) developed the VDLI. The VDLI is a parent report interview that evaluates the prelexical vocal and early lexical development of infants ages 6–21 months. The tool uses audio samples of authentic infant vocalizations to make targeted vocal behaviors clear and understandable to parents. The VDLI was originally piloted with parents of 80 children who were hard of hearing and 21 children with normal hearing (Ambrose et al., 2016). Results from this study revealed that the VDLI was sensitive to age and hearing status and was related to performance on concurrent measures of early communication abilities. In a subsequent study (Moeller et al., 2019), a revised version of the VDLI was given to parents of 160 typically developing children with normal hearing. Results from that study indicated that the VDLI accurately captured the developmental trajectory of vocal landmarks and was related to performance on a concurrent measure of early speech and language skills.

Current Study and Research Questions

The current study sought to further investigate the validity of the VDLI by examining concordance between parent report of early vocal behaviors assessed on the VDLI and judgments made by a trained researcher based on analysis of naturalistic audio recordings of children's vocalizations. This article addressed two research questions.

-

How well do parents and a trained researcher agree in their judgments of infant vocal behaviors that are surveyed on the VDLI?

We compared agreement across behaviors (identifying behaviors with the highest and lowest levels of agreement) and across subscales. Based on previous literature, we know that parents can reliably report the onset of their infants' canonical babbling and early lexical development. However, it is unclear if parents are able to accurately report on a variety of precanonical behaviors. It was predicted that parent–researcher agreement would be higher for the Canonical and Word subscales than the Precanonical subscale.

-

How well does the researcher's categorization and quantification of child vocal behaviors reflect the expected developmental pattern?

Based on the findings from our previous research showing that the VDLI reflects the expected developmental sequence of vocal behaviors (e.g., precanonical behaviors dominate the early months, canonical behaviors overlap with precanonical behaviors and increase steadily with age, and words emerge after the emergence of canonical behaviors), it was predicted that this developmental pattern would emerge in the researcher's categorization and quantification of vocal behaviors.

Method

Participants

All participants in the current study were part of a larger, cross-sectional study in which the VDLI was administered to parents of 160 typically developing infants who lived in homes where English was the primary language (for additional details regarding the larger study, see Moeller et al., 2019). Forty of these parents were selected and invited to collect all-day audio recordings of their children's vocal behaviors. Selection criteria were based on child age (to yield five children from eight age groups: ages 6–7, 8–9, 10–11, 12–13, 14–15, 16–17, 18–19, and 20–21 months), child sex, and maternal education level, with the goal of having a relatively even distribution of sex and maternal education level across each of the eight age groups. The researchers obtained ethics approval from two institution review boards: Boys Town National Research Hospital (approved Protocol 14-09-XP) and the University of Nebraska–Lincoln (approved Protocol 20160616233EX). All participants gave informed consent before taking part in this study. Table 1 summarizes demographic information for the parent and child participants in this study.

Table 1.

Demographic characteristics for parent and child participants.

| Characteristic | Parent (n = 40) | Child (n = 40) |

|---|---|---|

| Gender | ||

| Female | 37 (92.5%) | 21 (52.5%) |

| Male | 3 (7.5%) | 19 (47.5%) |

| Age | ||

| M | 31.3 years | 13.5 months |

| SD | 5.3 years | 4.7 months |

| Range | 22–45 years | 6–21 months |

| Maternal education level | ||

| High school or less | 8 (20.0%) | |

| Some college | 5 (12.5%) | |

| College degree | 15 (37.5%) | |

| Postgraduate degree | 12 (30.0%) |

VDLI Measure

The VDLI is a parent report interview designed to evaluate the prelexical vocal and early lexical development of infants, ages 6–21 months. The interview is presented to parents with the aid of a PowerPoint presentation, which contains audio samples of authentic infant vocalizations intended to help make the vocal behaviors targeted on the VDLI clear and understandable to parents. The VDLI is designed to address a developmental range from prebabble vocalizations to early word combinations. The interview contains a warm-up section and 18 individual items targeting vocal behaviors across three subscales: Precanonical, Canonical, and Word. As indicated in Table 2, the Precanonical subscale consists of seven items that target early vocal behaviors: pitch variations, mixed vowels, bilabial fricatives (i.e., sounds made while blowing through the lips), marginal syllables, reduplicated glides with vowels, vocal imitations, and range of vowels. The Canonical subscale consists of five items that query parents about more advanced vocal behaviors: canonical syllables, reduplicated canonical, variegated canonical, jargon, and range of consonants. The Word subscale contains six items that address advanced forms of vocal production: word imitations, closed syllables, consonant and vowel productions, true words, and two-word combinations. The measure yields a score for each subscale and a total score. A complete description of the VDLI with technical, administrative, and scoring details is available in the Supplemental Material for Moeller et al. (2019).

Table 2.

Vocal Development Landmarks Interview (VDLI) items, descriptions, and scoring type.

| VDLI item | Description of vocal behavior | Scoring |

|---|---|---|

| PC 2-1: Pitch Variation | Rising, falling, varied pitch contours | Frequency |

| PC 2-2: Mixed Vowels | 2 + well-formed vowels in a row; glide + vowel | Frequency |

| PC 2-3: Bilabial Fricatives | Vibration of lips or raspberries | Frequency |

| PC 2-4: Marginal Syllables | Slow timing, not well formed | Frequency |

| PC 2-5: Reduplicated Glide + Vowel | Repetitive string of /j, w, h/ + vowel(s) | Frequency |

| PC 2-6: Vocal Imitation | Clear attempts to imitate vocal behaviors/words | Frequency |

| PC 2-7: Range of Vowels | Count of vowels produced in isolation or with glides | Inventory |

| CB 3-1: Canonical Syllables | Clear well-formed syllable (e.g., /ba, gi, uk/) | Frequency |

| CB 3-2: Reduplicated Canonical | Repetitive strings of well-formed syllables (/bababa/) | Frequency |

| CB 3-3: Variegated Canonical | Repetitive strings with varied vowels/consonants | Frequency |

| CB 3-4: Jargon | Strings of variegated syllables with changing intonation | Frequency |

| CB 3-5: Range of Consonants | Count of consonants in babble | Inventory |

| WP 4-1: Word Imitations | Imitates adult words | Accuracy |

| WP 4-2: Closed Syllables | Final consonant present in words | Correctness |

| WP 4-3a: Consonant Production | Count of consonants produced consistently in words | Inventory |

| WP 4-3b: Vowel Production | Count of vowels produced consistently in words | Inventory |

| WP 4-4: True Words | Count of spontaneous words | Inventory |

| WP 4-5: Two-Word Combinations | Count of spontaneous true word combinations | Inventory |

Note. PC = Precanonical subscale; CB = Canonical subscale; WP = Word subscale.

In the warm-up section of the VDLI, parents are asked a series of open-ended questions that are designed to guide the examiner in making a global determination of the child's current vocal stage (precanonical, canonical, or word). In the event that the global stage is unclear from the parental response, the examiner is given the flexibility to ask follow-up questions to clarify. The information gathered from the warm-up questions is used to determine which subscales of the VDLI to administer. Basal and ceiling decision rules are also included to avoid asking parents to report on vocalizations that are no longer relevant to their child's linguistic level or are a long way off developmentally, while also accounting for children who may be transitioning between stages. For younger infants (6–12 months of age), the rules involve determining whether or not the child is producing more than two true words, which guides administration of either the Canonical and Word subscales (if answer is “yes”) or the Precanonical and Canonical subscales (if answer is “no”). For infants 13 months of age and older, the decision rules are based on the estimated number of words the child is producing, establishing whether the Precanonical and Canonical subscales (if the child produces zero or one word), the Canonical and Word subscales (if the child produces two to 49 words), or only the Word subscale (if the child produces 50 or more words) will be administered. Results from our previous studies involving the VDLI (Ambrose et al., 2016; Moeller et al., 2019) indicate that the warm-up section provides reliable guidance to the examiner regarding which subscales to administer.

The VDLI consists of three types of scoring formats: (a) frequency ratings, (b) phonetic or word inventories, and (c) accuracy or correctness ratings (see Table 2). For items requiring a frequency rating, parents listen to vocal samples of infants producing the target behavior and then estimate the frequency of the target behavior in their child's repertoire, using a 4-point Likert scale (i.e., “never,” “rarely,” “sometimes,” or “frequently”; adapted from Kishon-Rabin et al., 2005). Most items requiring a frequency rating are presented in a paired-comparison format in which the target behavior is contrasted with a vocal behavior of similar form (i.e., precanonical, canonical, or word) yet differing complexity (e.g., reduplicated vs. variegated canonical sequences). For items requiring reports of the child's phonetic or lexical inventory, parents are asked to provide an estimate of the number of different sounds or words their child is currently producing. Audio samples are provided for three of the inventory items (PC 2-7: Range of Vowels, WP 4-4: True Words, and WP 4-5: Two-Word Combinations) to ensure parents understand the behavior being queried. Audio files are not presented with the remaining three inventory items (CB 3-5: Range of Consonants, WP 4-3a: Consonant Production, WP 4-3b: Vowel Production), which were judged in the tool's development to be clear to parents without support of audio samples, in part because they used a recognition format in which parents were asked only about their child's production of a limited set of phonemes and the examiner provided examples of those phonemes in the context being queried. For phonetic inventories, the examiner uses a list of the most common early developing vowels and consonants when querying parents about the sounds their child produces. There are two items on the VDLI that require parents to report on either the accuracy or the correctness of their infant's vocalizations. For the accuracy item (WP 4-1: Word Imitations), parents are prompted to listen to samples of various child word imitations and indicate how close their own child's imitations are to words they model using a visual scale from “far off” to “somewhat close” to “very close.” Similarly, for the correctness item (WP 4-2: Closed Syllables), parents are prompted to listen to samples of children producing words ending in closed and open syllables and, using the 4-point Likert scale of never, rarely, sometimes, or frequently, indicate how frequently their child produces words with closed syllables.

Procedure

The researchers utilized two sources of data from a previous larger study conducted by Moeller et al. (2019): parents' responses on a brief demographic questionnaire (i.e., race, ethnicity, age, and maternal education level) and their responses on the VDLI. Naturalistic audio recordings of children's vocal behaviors that were collected shortly after the parents completed the VDLI were gathered as part of the current study.

Parent-Reported VDLI Responses

The VDLI was administered to parents over the telephone with the aid of a shared PowerPoint presentation with embedded audio files of authentic infant vocalizations, which parents accessed via a secure website. Prior to beginning the interview, parents were informed that the purpose was to gain an understanding of the types of sounds and/or words their child produced on a daily basis. They were informed that they would be listening to examples of infants making various sounds and talking and that their task was to think about the sounds their child produced on a typical day and consider whether or not their child's productions were similar to the ones heard in the samples provided. Parents were allowed to listen to each audio example as often as desired.

Due to the basal and ceiling conventions established for the VDLI, parents were only administered the VDLI subscales (Precanonical, Canonical, and Word) that were appropriate for their child's current developmental level. Sixteen parents were administered the Precanonical and Canonical VDLI subscales, 20 were administered the Canonical and Word subscales, and four were administered only the Word subscale. This resulted in data on the Precanonical subscale for 16 children, the Canonical subscale for 36 children, the Word subscale for 24 children, and a total score for all 40 children. Each response type (frequency, inventory, and accuracy/correctness) had a corresponding scoring scheme that utilized a point scale ranging from 0 to 3. For each subscale, children's item scores were summed and divided by the total points possible for the subscale, yielding a percent score. If a child was not administered a subscale because it was deemed to be too far above or below their developmental level, they were assigned a score of 0 or 100, respectively, on that subscale. Total VDLI scores were calculated by averaging the percent scores for each of the three subscales.

Audio Recordings and Vocal Segment Selection

Following completion of the VDLI, parents were asked to collect a naturalistic recording of their infant's vocal behaviors using a Language Environment Analysis (LENA; LENA Research Foundation) digital language processor (DLP). Each DLP weighs about 2 oz, measures about 1 × 6 × 9 cm, and is worn by the infant using a customized vest. The DLP records up to 16 hr of audio in the child's natural environments. Parents were mailed a LENA DLP, two vests, instructions, and return packaging and were asked to gather an all-day recording of their child within 2 weeks of completing the VDLI, picking a typical day when at least one parent was home with the infant.

The returned audio recordings were analyzed and labeled using the automated LENA software. Of the four reports generated by the LENA system (i.e., adult words, conversational turns, child vocalizations, and audio environment), only the child vocalizations reports were used in the current study. The child vocalizations report provides an estimate of the number of vocalizations the child produced during the recording (LENA Research Foundation, 2015). Nonspeech utterances, such as vegetative sounds (e.g., burping, sneezing, and breathing) and fixed signals (e.g., crying and laughing), are not counted as child vocalizations. The child vocalizations reports were used to select six highly voluble 5-min audio segments (30 min in total) from each child's audio recording, a length that preliminary analyses indicated allowed for sufficiently stable scores. These 30-min audio segments were then exported as individual WAV files.

Vocal Segment Coding

All primary coding was completed by the first author (hereafter referred to as the researcher). Prior to coding the audio recordings of infants' vocalizations, the researcher received extensive training in the identification and categorization of the infant vocal behaviors addressed on the VDLI (i.e., training up to consistent agreement with the final author) using audio samples from pilot subjects. Definitions, categories, and rules for coding vocalizations were based on the literature regarding infant vocal development. If the researcher had questions about the coding of a vocal behavior, coding decisions were made through consensus with the final author. 1

All coding was completed in the Computerized Language Analysis (CLAN) program (MacWhinney, 2000) using the aforementioned WAV files. After tagging each vocalization in CLAN, the researcher coded each vocalization according to categories representing the VDLI vocal behaviors (see Table 2). If the child produced vocalizations from a subscale of the VDLI that was not administered to the parent, those vocalizations were coded only by subscale (i.e., as being a precanonical-, canonical-, or word-level behavior), rather than by a specific item-level vocal behavior. After coding was completed, the CLAN analysis tools were used to compute output totals for each vocal behavior. Additionally, the vocal behavior codes and subscale codes were utilized to tally the number of vocalizations corresponding to each subscale, which were then divided by the total number of vocalizations the child produced in the 30-min sample to yield the proportion of vocalizations that were at the precanonical, canonical, and word levels.

In addition to being coded, vocalizations were broadly transcribed. These broad transcriptions allowed the researcher to determine the accuracy of word imitations and the number of different words, word combinations, closed syllables, vowels, and/or consonants observed in each child's repertoire for purposes of scoring the inventories and the accuracy/correctness items. Following the methods of Stoel-Gammon (1987), a conservative approach was applied for crediting vowel and consonant productions: A child received credit for a vowel or consonant if they produced the phoneme a minimum of 3 times within the 30-min audio sample. This procedure supported the researcher's identification of consistently used phonemes rather than every phoneme produced. This was expected to allow the researcher's responses to align with responses of parents, who were likely to listen more globally to their child's productions and thus report phonemes they consistently heard their child produce as opposed to every phoneme they had ever heard their child produce.

Approaches for Evaluating Agreement

Two scoring approaches were used to evaluate agreement between the researcher's coded observations of the vocal samples and parents' responses on the VDLI. In the primary approach, the researcher's coded observations and the parents' responses for each item were converted into binary scores representing presence versus absence of a behavior (heretofore referred to as the presence–absence approach). In the secondary approach, the researcher's coded observations were converted into scores that aligned with the VDLI scoring (heretofore referred to as the VDLI-aligned approach). However, unlike the presence–absence approach, which could be applied to all items, those with a frequency rating response did not lend themselves to application of the VDLI-aligned approach due to differences in how the parents and the researcher made judgments about frequency: Parents were asked to make subjective judgments about how often (i.e., the frequency) their child produced the target behaviors (never, rarely, sometimes, and frequently), while the researcher tallied specific behaviors from careful analysis of the selected 30-min audio recordings. Therefore, the presence–absence approach was used as the primary evaluation approach in this study, as it allowed all VDLI items to be placed on the same scale and was necessary for our subsequent analysis (see the Statistical Analyses section). The secondary VDLI-aligned approach captured some of the variability in children's vocal productions not afforded by the presence–absence approach for the eight items that utilized inventory reports or accuracy/correctness ratings.

Presence–absence approach. For this scoring approach, if a vocal behavior was heard by the researcher at least once during the 30-min audio sample, it was assigned a score of 1 (present). If no evidence of a behavior was heard, it was assigned a score of 0 (absent). The same presence–absence scoring was used to recode the parent-reported VDLI responses. For example, for the 10 frequency-based items, when parents indicated the presence of a behavior (i.e., “rarely,” “sometimes,” or “frequently”), these were recoded as 1 (present), while behaviors reported as “never” or absent received a score of 0. Similarly, for the eight VDLI-aligned items involving an inventory report or accuracy/correctness rating, when parents reported the production of a phoneme, words, closed syllable, and/or word imitation (i.e., corresponding to a VDLI score of either 1, 2, or 3), these were recoded as 1 (present), while reports of no production (absent) maintained a score of 0. It should be noted that for two inventory items on the Word subscale (WP 4-3a and WP 4-3b), a score of 0 did not always correspond to absent behaviors, but rather an inventory of zero, one, or two consonants for WP 4-3a and zero or one vowel for WP 4-3b. Agreement for the presence–absence approach was defined as concordance between the parent and researcher that a specific behavior was either present or absent.

VDLI-aligned approach. For this scoring approach, which was applied to the eight VDLI items that utilized either an inventory report or an accuracy/correctness rating, the researcher's coding and transcriptions of children's vocalizations were converted into scores that aligned with the respective VDLI scoring schemes. For the six items that involved phoneme or lexical inventories, the VDLI score reflected parent's report of the size of their child's phoneme or lexical inventory. Likewise, the researcher's transcriptions of these six vocal behaviors were tallied and assigned a score using the same scoring scheme. For the item that required an imitation accuracy rating (WP 4-1), the VDLI score was assigned based on parent's report of how accurately their child imitates adult words (0 = no imitation, 1 = far off, 2 = somewhat close, 3 = very close). The researcher's scoring procedures for this item involved identifying each instance of the child imitating an adult form in the 30-min sample and assigning each imitation a score based on the number of accurate components it contained. For example, if a child's imitation contained at least one correct phoneme (consonant or vowel), contained the correct number of syllables, and mimicked the prosody of the caregiver, it was scored as very close (3), as the inclusion of such components demonstrates a close approximation of an adult form. However, if an imitation only contained two of the components noted above, it was scored as somewhat close (2), and if it only contained one of the components, it was scored as far off (1). The researcher assigned a score of 0 for this item if no imitations were heard in the 30-min sample. If the researcher heard more than one imitation, the scores for all imitations were averaged and rounded to the nearest score (1, 2, or 3). For the item that required a correctness rating (WP 4-2: Closed Syllables), parents were asked to indicate how frequently their child correctly produced closed syllables. The researcher's scoring procedure for this item involved counting each time the child produced a word in which the adult form had a final consonant (closed syllable) and determining whether the child used a final consonant. The number of words a child produced using a closed syllable was then divided by the total number of closed syllable opportunities, resulting in a proportion of closed syllables. A proportion of 0 received a score of 0, a proportion of 0.33 or below received a score of 1, a proportion of 0.34–0.66 received a score of 2, and a proportion of 0.67 or greater received a score of 3.

Agreement for the VDLI-aligned approach was based on adjacency rather than exact agreement: parent and researcher scores were considered to be in agreement if they fell within 1 point (plus or minus) of each other (e.g., parent said “1” and researcher said “2”). The use of adjacent agreement was considered to be a more appropriate standard of agreement for the VDLI-aligned scores due to differences in the parents' and the researcher's exposure to and opportunities to witness children's vocalizations (day-to-day interactions [parents] vs. 30 min of selected audio recording from a single day [researcher]).

Interrater reliability. Reliability of scoring was established by an undergraduate student in speech-language pathology who had experience in transcribing vocalizations using the International Phonetic Alphabet and coding infant/toddler language samples. As with the researcher, this reliability coder received extensive training in identification and categorization of infant vocalizations addressed on the VDLI using audio samples from pilot subjects.

Following the training period, one 30-min audio sample was randomly selected for reliability scoring from each of the eight age groups, resulting in interrater reliability for 20% of the sample. All audio samples were scored using both the presence–absence and VDLI-aligned approaches. Reliability was assessed in two ways: (a) mean percentage of absolute agreement for presence–absence scoring and (b) mean percentage of adjacent agreement for VDLI-aligned scoring. The resulting reliability was high for both types of agreement. The overall mean percentage of absolute agreement for presence–absence scoring was 98% (range: 91%–100%), while that of adjacent agreement for VDLI-aligned scoring was 100%.

Statistical Analyses

The first research question explored the extent to which parents and the researcher agreed in their judgments of infant vocal behaviors surveyed on the VDLI. A finding of acceptable concordance between parent and researcher reports would provide further evidence of the utility of parent report to examine a range of infant vocal behaviors. In this study, we define “acceptable” as at least moderate levels of agreement (between 0.60 and 0.74) using guidelines from Cicchetti (1994). To analyze this question statistically, we converted all scores to presence–absence scoring and used a generalized linear mixed model (GLMM) using presence–absence as the outcome score with a logit link and binomial variance function and estimated using adaptive Gaussian quadrature. The model included fixed effects for VDLI item and rater (parent or researcher) and a random intercept effect for child. A random effect is necessary to account for the same person being scored by two raters on multiple items (creating within-subject correlated data). The GLMM provides a direct test of whether the researcher's judgments differed significantly from the parents' judgments for each of the respective subscales using odds ratios. Intraclass correlations were used to measure the proportion of between-subjects variance for each subscale. Additionally, descriptive results, including mean percentages of parent–researcher agreement, were calculated for both presence–absence and VDLI-aligned scoring. Finally, patterns of disagreement at the item level for both presence–absence (for all items) and VDLI-aligned (for the eight relevant items) scoring were explored descriptively to gain insights regarding potential sources of parent–researcher differences.

The second research question examined whether the researcher's categorization and quantification of child vocal behaviors observed in the audio samples reflected the expected developmental pattern. Three linear regressions were carried out to investigate the relationships between age and the proportions of vocal behaviors the researcher coded as precanonical, canonical, and word. Additionally, descriptive statistics were used to explore how the proportions of vocal behaviors varied as a function of age. All analyses were performed using either SPSS Version 24.0.0.1, SAS Version 9.4, or R statistical software.

Results

Parent–Researcher Agreement on VDLI Behaviors

No significant differences in rater agreement were found for the Canonical (p = .5439) or Word (p = .1918) subscale (see Table 3). However, the GLMM results indicate a significant difference in parent–researcher agreement for the Precanonical subscale, as reflected in the test of the group effect (−2.907; p = .0168). This is the log odds of responding “1” (present) for the researcher versus responding “1” for the parent, which can be interpreted in terms of odds ratios. 2 Results indicate that the odds of responding “1” on the Precanonical subscale are 18 times higher for the parent than for the researcher (signified by the negative coefficient).

Table 3.

Fixed effects results of the generalized linear mixed model testing for differences in parent–researcher agreement as a function of subscale (Precanonical, Canonical, Word).

| Subscale | n | GR estimate | SE | Z | p | ICC |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Precanonical | 16 | −2.91 | 1.22 | −2.40 | .0168 | .21 |

| Canonical | 36 | 0.25 | 0.41 | 0.61 | .5439 | .68 |

| Word | 24 | −0.70 | 0.53 | −1.31 | .1918 | .66 |

Note. All scores were placed on a presence–absence scale for the purposes of the generalized linear mixed model. GR = the group effect (log odds of responding “1” for the researcher vs. the parent); ICC = intraclass correlation coefficient (proportion of unexplained variance at the subject level).

Intraclass correlation coefficients (ICCs) are typically interpreted as a measure of agreement. In calculating ICCs from the GLMM, the ICC is the proportion of the total variation accounted for by variability between subjects. The computed ICC is further interpreted as the correlation among repeated observations by participant. This correlation varied by subscale: ICC = .21 for the Precanonical subscale, ICC = .68 for the Canonical subscale, and ICC = .66 for the Word subscale. The standard deviations for the random effects (child) were 0.94, 2.64, and 2.53 for the Precanonical, Canonical, and Word subscales, respectively.

Mean percentages of agreement also were calculated for both presence–absence (overall, subscale, and item) and VDLI-aligned (item only) scoring. As indicated in Table 4, overall presence–absence agreement was 87.4%, with similarly high levels of agreement for the Precanonical (90.2%), Canonical (82.8%), and Word (91.0%) subscales. At the item level (see Table 5), presence–absence agreement reached high levels (≥ 87.5%) for 12 of the 18 items, with the lowest levels of agreement occurring on items PC 2-6: Vocal Imitation (62.5%), CB 3-4: Jargon (66.7%), and PC 2-3: Bilabial Fricatives (68.8%). For the VDLI-aligned scoring, agreement reached high levels (≥ 87.5%) for seven of the eight items, with the lowest level occurring on item WP 4-3a: Consonant Production (83.3%).

Table 4.

Parent–researcher agreement per Vocal Development Landmarks Interview subscale and overall for presence–absence scoring.

| Subscale | n | M (SD) |

|---|---|---|

| Precanonical | 16 a | 90.18 (11.33) |

| Canonical | 36 a | 82.78 (17.99) |

| Word | 24 a | 90.97 (18.38) |

| Overall | 40 | 87.37 (11.78) |

Indicates the number of parents who were administered the subscale.

Table 5.

Descriptive information for parent–researcher agreement on Vocal Development Landmarks Interview (VDLI) items.

| Item | VDLI-aligned agreement | PA agreement | Percent reporting presence |

Instances and direction of PA disagreement |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Researcher | Parent | Researcher | Parent | |||

| PC 2-1: Pitch Variation | 100% | 100% | 100% | |||

| PC 2-2: Mixed Vowels | 100% | 100% | 100% | |||

| PC 2-3: Bilabial Fricatives a | 68.8% | 68.8% | 100% | +5 | ||

| PC 2-4: Marginal Syllables | 100% | 100% | 100% | |||

| PC 2-5: Reduplicated Glide + Vowel | 100% | 100% | 100% | |||

| PC 2-6: Vocal Imitation a | 62.5% | 68.8% | 93.8% | +1 | +5 | |

| PC 2-7: Range of Vowels | 93.8% | 100% | 100% | 100% | ||

| CB 3-1: Canonical Syllables b , c | 83.3% | 100% | 83.3% | +6 | ||

| CB 3-2: Reduplicated Canonical | 94.4% | 91.7% | 97.2% | +2 | ||

| CB 3-3: Variegated Canonical a , b | 77.8% | 88.9% | 72.2% | +7 | +1 | |

| CB 3-4: Jargon b , d | 66.7% | 27.8% | 55.6% | +1 | +11 | |

| CB 3-5: Range of Consonants | 97.2% | 91.7% | 97.2% | 88.9% | +3 | |

| WP 4-1: Word Imitations | 91.7% | 91.7% | 91.7% | 100% | +2 | |

| WP 4-2: Closed Syllables | 87.5% | 87.5% | 79.2% | 75.0% | +2 | +1 |

| WP 4-3a: Consonant Production | 83.3% | 91.7% | 91.7% | 100% | +2 | |

| WP 4-3b: Vowel Production | 95.8% | 95.8% | 95.8% | 100% | +1 | |

| WP 4-4: True Words | 95.8% | 100% | 100% | 100% | ||

| WP 4-5: Two-Word Combinations c | 100% | 79.2% | 33.3% | 37.5% | +2 | +3 |

Note. +[number] indicates the number of times one judge observed the behavior but the other did not (e.g., +5 in parent column means in five cases, parents observed the behavior and the researcher did not). Superscript letters refer to hypotheses regarding factors contributing to parent–researcher disagreements (for items with > 3 disagreements). PA = presence–absence; PC = Precanonical; CB = Canonical; WP = Word.

Insufficient opportunity for researcher to observe.

Parents had trouble understanding description or identifying behavior.

Behavior was rare or just emerging.

Coding definition too strict.

A final descriptive analysis involved exploration of patterns of disagreement between parents and the researcher to gain insights about potential sources of difference. As shown in Table 5, four major patterns emerged across the items: (a) complete (100%) agreement between parent and researcher, (b) disagreements in which parents reported the behavior but the researcher did not, (c) disagreements in which the researcher reported the behavior but the parents did not, and (d) occurrence of both types of disagreements (i.e., for some children, the researcher reported the presence of the behavior but the parents did not, and for other children, the parents reported the presence of the behavior but the researcher did not).

For five of the seven items on the Precanonical subscale, both the researcher and parents reported presence of the behaviors in 100% of the subjects. For the two remaining items (PC 2-3: Bilabial Fricatives and PC 2-6: Vocal Imitation), disagreements primarily arose when the parents reported presence of the behavior but the researcher did not. When parents reported these behaviors were present, they typically reported them as occurring “rarely” in contrast to other precanonical items where presence was more often reported as “sometimes” or “frequently.”

For the Canonical subscale, two of the five items had agreement levels above 90% (CB 3-2: Reduplicated Canonical and CB 3-5: Range of Consonants). In addition, both parents and the researcher reported observing these two behaviors in a high percentage of subjects (≥ 88.9%). For CB 3-1: Canonical Syllables and CB 3-3: Variegated Canonical, agreement was 83.3% and 77.8%, respectively; disagreements primarily arose due to the researcher reporting presence of the behaviors, whereas parents reported them as being absent. For item CB 3-4: Jargon, there was 66.7% agreement; disagreements were due to parents reporting presence of the behavior and the researcher reporting the behavior was not observed. As with the two behaviors on the Precanonical subscale where disagreements arose, this behavior was reported as occurring “rarely” by the majority of parents, whereas the majority of parents reported “sometimes” or “frequently” for the other canonical behaviors.

For the Word subscale, four of the six items had very high agreement (> 91%). As with most behaviors that had high presence–absence agreement, both parents and the researcher reported observing these four behaviors in a high percentage of subjects. Item WP 4-2: Closed Syllables also had relatively high agreement (87.5%), while item WP 4-5: Two-Word Combinations had the lowest level of agreement in the Word subscale (79.2%). For this item, disagreements were mixed, with two arising due to the researcher reporting the presence of the behavior and parents not reporting, and three in which parents reported the presence of the behavior and the researcher did not.

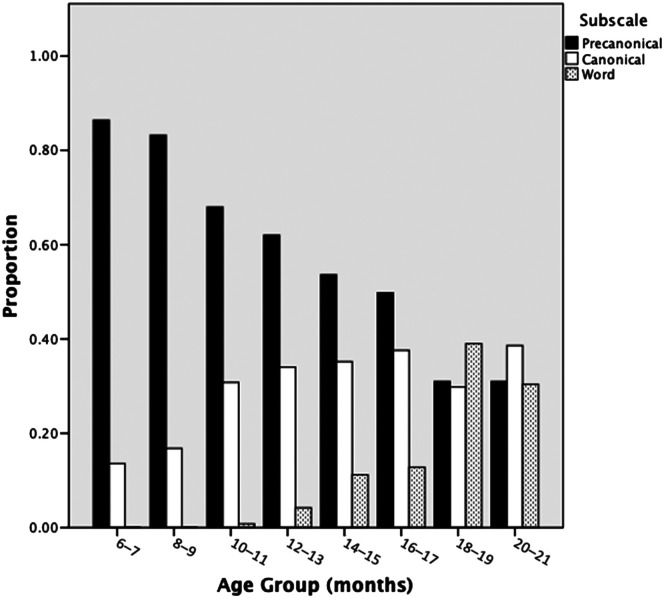

Proportions of Researcher-Observed VDLI Vocal Behaviors by Age Group

Three simple linear regressions were conducted to examine the relationship between age and the researcher-coded proportions of vocalizations at the precanonical, canonical, and word levels. For precanonical productions, there was a significant decrease in proportion by age (β = −.043, p < .0001), indicating that the proportion of vocalizations coded as precanonical decreased by an average of .043 with each extra month of age. For canonical productions, there was a significant increase in proportion by age (β = .016, p = .0006), indicating that the proportion of vocalizations coded as canonical increased by an average of .016 with each extra month of age. For word productions, there was also a significant increase in proportion by age, with a slightly steeper slope than for canonical (β = .027, p < .0001), with results indicating that for each extra month of age, the proportion of vocalizations coded as word increased by an average of .027.

Descriptive statistics were used to explore patterns in the researcher-observed proportions. As illustrated in Figure 1, precanonical vocal productions accounted for over 80% of vocal productions observed by the researcher for children in the youngest two age groups, whereas canonical productions accounted for less than 20%, with words not yet emerging. As the age of the children increases, the proportion of precanonical vocalizations observed by the researcher declined, while canonical productions and eventually word productions began accounting for larger proportions of vocal productions. Thus, observer categorizations of the children's vocalizations reflected an expected developmental pattern.

Figure 1.

Proportions of researcher-observed vocalizations at the Precanonical, Canonical, and Word subscales for each age group.

Discussion

The purpose of this study was to determine whether parent report on the VDLI is a valid means for quantifying infants' vocal behaviors. We also explored whether the researcher's categorization and quantification of infant vocalizations observed in the audio recordings reflected the expected developmental patterns. Collectively, the results indicate that parents can reliably report on their children's prelexical and early lexical development and provide support for use of the VDLI as a clinical measure of vocal development in infants and toddlers ages 6–21 months.

Parent–Researcher Agreement

Our first research question explored the extent of agreement between parent and researcher judgments of vocal behaviors surveyed on the VDLI. As predicted, no significant differences in parent–research agreement were found for the Canonical and Word subscales, but a statistically significant difference in agreement was found for the Precanonical subscale. The absence of differences in parent–researcher agreement for the Canonical and Word subscales aligns with previous literature that indicates parents can reliably report on the onset of their infants' canonical babbling (Oller, 1980, 2000; Oller et al., 1999, 2001) and early lexical development (Dale, 1991; Feldman et al., 2005). On the Precanonical subscale, however, parents were 18 times more likely to report the presence of these behaviors compared to the researcher. Upon closer analysis of the data associated with these subscale items, this discrepancy was found to be largely related to only two items (PC 2-3: Bilabial Fricatives and PC 2-6: Vocal Imitation). These findings suggest that there may have been insufficient opportunity for the researcher to observe these behaviors in the 30-min sample. The finding that the discrepancy was largely related to only two items also indicates that not all precanonical behaviors are necessarily challenging for parents to identify and/or report on.

The computed ICCs revealed limited variability across parent ratings on the Precanonical subscale, with nearly all parents reporting these behaviors as being present. This lack of variability among parent reports highlights a potential issue with the sensitivity of the presence–absence scoring for such behaviors, indicating that it may not capture differential reporting among parents. Future studies should monitor this pattern to further assess this hypothesis.

Overall, mean percentages of parent–researcher agreement were high for both the presence–absence and VDLI-aligned scoring. These findings suggest that parents (or a trained researcher listening to 30 min of audio recording of the child) can reliably identify and report on the presence (or absence) of key vocal landmarks and provide accurate estimates of the children's vocal repertories. Such findings are consistent with the results of several previous studies (Karousou & Nikolaidou, 2015; Oller et al., 1999, 2001).

When examining the results of the presence–absence agreement at the item level, four patterns emerged that provide further insight into parents' abilities to reliably identify the presence of certain vocal behaviors assessed by the VDLI, as well as potential sources of disagreement. The first pattern that emerged involved 12 vocal behaviors that resulted in complete (100%) or near-complete (≥ 87.5%) agreement between parents and researcher. Additionally, these behaviors were almost always reported as being present by both the researcher and parents. The high rates of agreement, coupled with behaviors nearly always being reported as present, indicate that these behaviors are clear landmarks prototypical of children within these age groups and can be easily identified and reported by parents. As such, these landmarks may be ideal for use as “red flag” indicators, as a lack of their reported presence could indicate potential cause for concern, especially when later (canonical and word) behaviors are not reported. What these results do not tell us is whether the vocal behaviors with or near 100% agreement were just emerging or were well established in the infants who demonstrated them. This again speaks to a potential issue with the sensitivity of the presence–absence scoring, as it may not provide sufficient information for identifying individual differences among children of particular ages. The ability to distinguish between an emergent versus a well-established developmental behavior is commonly used by clinicians and practitioners to set intervention goals or to judge the extent of progress made as a result of interventions. In this regard, the presence–absence scoring approach would likely be too blunt a measure for judging some VDLI vocal behaviors. This is where the frequency-based scoring may be more useful for the assessment of VDLI behaviors, as the 4-point Likert scale is inherently designed to capture variability in development. However, as mentioned earlier in this article, parent–researcher agreement was not examined for the frequency-based scoring due to difficulty in aligning the appraisal methods used by parents and the researcher for their frequency-based judgments.

A second pattern that emerged from the presence–absence agreements consisted of differences in which parents reported presence of a behavior but the researcher did not. This pattern emerged for three vocal behaviors (PC 2-3: Bilabial Fricatives, PC 2-6: Vocal Imitation, and CB 3-4: Jargon). One explanation for this pattern is that the researcher did not have ample opportunity to observe the behavior in the selected 30-min audio segments. This hypothesis is supported by the fact that the majority of these differences occurred among infants from the youngest two age groups where parents reported these behaviors as occurring infrequently. The researcher's observations confirmed that these behaviors were seldom produced. Such findings suggest that these behaviors may have been emerging or produced only in select contexts, thus reducing the likelihood that the researcher would observe them in the 30-min samples. An alternative explanation for this pattern could be that the coding definition to which the researcher adhered may have led to a stricter interpretation of this behavior by the researcher than by parents.

A third pattern that emerged involved differences in which the researcher reported presence of a behavior and parents did not. This pattern was most prominent on two items on the Canonical subscale: CB 3-1: Canonical Syllables and CB 3-3: Variegated Syllables. This finding was somewhat surprising as prior research clearly states that parents can reliably report the onset of canonical babbling in infants (Oller, 1980; Oller et al., 1999, 2001). However, the VDLI asks parents to report on a range of canonical behaviors, not just canonical forms. One explanation for the differences could be that the VDLI item descriptions or audio examples may not have been clear to some parents. It is also possible that some parents may have had difficulty discriminating between similar-sounding vocal behaviors that are within the infants' vocal repertoire. For example, reduplicated syllables are, by definition, “canonical syllables repeated in a string.” It is not uncommon for children to alternate between single canonical syllables (e.g., /ba/) and reduplicated syllables (e.g., /bababa/). However, due to their saliency, parents may attend more to reduplicated syllables than single canonicals, which, in turn, could influence their low reporting on single syllables. Similarly, parents may find it challenging to identify the contrast between variegated babbling and jargon, as jargon is a form of variegated babble, the only difference being that jargon has a speechlike prosody. As with canonical and reduplicated syllables, children may alternate between variegated babbling and jargon, making it challenging for parents to distinguish between the two at certain developmental stages, resulting in reporting on the presence of the more salient behavior. These findings provide guidance for possible improvements to the descriptions and examples of selected VDLI items in the Canonical subscale to ensure that parents have a clear understanding of the vocal behaviors about which they are being asked to report.

A final pattern that emerged was one in which disagreements were mixed between parents and the researcher. This type of pattern was most prominent on the item measuring two-word combinations (WP 4-5). One explanation for this difference is that the behavior was just emerging and/or infrequent, thus making the observation of its presence challenging for both parents and the researcher. This hypothesis is supported by the low percentages at which these behaviors were observed by both the researcher and parents (33% and 38%, respectively).

Developmental Patterns

Our second research question explored the extent to which the researcher's categorization and quantification of child vocal behaviors observed in the audio samples reflected the expected developmental pattern. As predicted, a clear developmental pattern emerged that is consistent with the literature on stages of early vocal development and with the results reported in previous research involving parent-reported vocal behaviors using the VDLI (Moeller et al., 2019). For children in the youngest age groups (6–7 and 8–9 months), precanonical behaviors comprised the majority of infants' vocal productions, whereas canonical behaviors were just emerging, and word forms were not yet present. As age increased, infants' precanonical vocalizations began to steadily decline, whereas canonical forms and eventually words began to account for larger proportions of vocal productions. The shift from largely precanonical vocalizations at the earliest ages to increased use of canonical vocalizations and eventually vocalizations at the word level aligns with the findings of Nathani et al. (2006), who found that as infant age increases, the trend of less speechlike vocalizations (i.e., precanonical) tends to decline and adultlike and phonetically complex vocalizations (i.e., canonical and word) become increasingly common.

Canonical forms were present in the youngest age group but only just emerging, comprising less than 15% of infant vocal productions. Starting around 10 months of age, the proportion of canonical forms almost doubled, comprising over a third of infant vocalizations. These data are consistent with data from Oller and colleagues (Oller, 1980; Oller et al., 1999, 2001), who reported the mean age of onset of canonical babbling as 6 months, with most infants engaging in canonical babbling by 10 months of age.

Evidence of word productions began to emerge between 10 and 13 months of age, and at 18–19 months of age, they comprised the largest proportion of vocal productions. Although word productions showed a significant increase beginning at 18–19 months of age, precanonical and canonical forms were still very much present, each accounting for approximately one third of children's vocal productions. The finding that children in this sample continued to use precanonical and canonical vocalizations even after word productions became predominant aligns closely with findings reported by Robb et al. (1994). Robb et al. found that as children begin to transition into the single-word stage sometime between 12 and 18 months of age, they tend to exhibit a gradual increase in the number of single-word productions, with a marked increase occurring sometime between 13 and 21 months of age. Furthermore, Robb et al. found that even children as old as 19–25 months were still producing “nonword” vocalizations (i.e., precanonical and canonical), with some predominately producing such vocalizations until 16–17 months of age. Overall, the developmental pattern of vocal behaviors found in this study is consistent with the work of a number of investigators of infant vocal development (Bates et al., 1991; Nathani et al., 2006; Oller, 1980, 2000), including our own (Ambrose et al., 2016; Moeller et al., 2019), providing further evidence that the VDLI can capture the anticipated trajectory of infant vocal development and be used to monitor development over time.

Limitations and Future Directions

It is acknowledged that the sample size and range of participant demographics were relatively small for a GLMM analysis and exploring differences in agreement. In particular, the data gathered on the Precanonical subscale were based on the responses of only 16 parents, which likely contributed to the limited variability in parent report scores. Additionally, the limited variance in socioeconomic status among parents highlights the need for future studies of the VDLI using more diverse samples. Second, although the results from this study, as well as a preliminary analysis in which we examined the stability of scores across vocal samples of varying time lengths, indicated that the 30-min audio samples appeared to be sufficient for examining the presence of most vocal behaviors, longer samples may have provided more opportunity to observe vocal behaviors that were just emerging and/or produced infrequently (e.g., vocal imitations). Third, although it is unlikely that the children's vocal skills changed significantly in the 2 weeks between when parents were interviewed and audio recordings were obtained, it is possible that some development could have occurred, thus contributing to differences in parent and researcher reports. Fourth, research has shown that during phonetic transcription, listeners may intuitively interpret what is being said, and as a result, those interpretations may influence their transcriptions (Oller & Eilers, 1975). Although efforts were taken to ensure reliability of the researcher's transcriptions (e.g., extensive training, adherence to coding rules, consensus checks), we acknowledge that errors may have occurred. Finally, because parents and researchers used different criteria for judging the frequency of vocal behaviors, we were unable to directly compare agreement for frequency-based scores. This necessitated primary reliance on the presence–absence scoring, which may have limited the findings.

Despite these limitations, these results do provide us with direction for future research. As noted in our previous research (Ambrose et al., 2016; Moeller et al., 2019), future studies are needed to further examine the psychometric properties of the VDLI, including additional item analysis. Such research will confirm whether items that showed evidence of lower agreement should be modified or eliminated from the measure. Additionally, larger studies are needed to further examine potential factors that contribute to parent report of vocal behaviors. It would be of value to investigate the effects of priming (e.g., informing parents what vocal behaviors to listen for prior to the actual interview) on parent report using the VDLI. In addition, the VDLI needs to be explored further with various groups of children who are at risk for delays in early vocal development.

In the meantime, an app and a web-based platform to support VDLI administration have been developed, and the administration manual has been refined to include descriptions of how to administer, score, and interpret the VDLI in its current form. The manual and a beta version of the app, which sends deidentified data back to the VDLI developers, are being shared with professionals working with young children in a variety of settings (e.g., clinical, medical, and early intervention). Such efforts serve the dual purpose of continuing validation efforts and making the VDLI more accessible while validation efforts are ongoing. 3 Additionally, given the current situation surrounding the COVID-19 pandemic, we believe that access to the VDLI app may be extremely timely and beneficial.

Summary

This study was part of a multiphase investigation aimed at examining the validity of the VDLI. The current study used detailed coding and scoring to explore parent–researcher agreement on infants' vocal behaviors assessed by the VDLI at the precanonical, canonical, and word levels. No significant differences in parent–researcher agreement were found for the Canonical and Word subscales, but significant differences were found for the Precanonical subscale. High to moderate levels of agreement were found for all subscales for the presence versus absence of VDLI vocal behaviors as well as for all VDLI-aligned items. Researcher observations reflected the expected developmental trajectory for infant vocalizations. These findings, combined with those reported in previous studies, provide support for the use of the VDLI as a clinical tool for assessing the prelexical and early lexical sound development in infants and toddlers who may be at risk for delayed vocal development. Results also provide direction for further improvements of the tool.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by three grants: two from the National Institute on Deafness and Other Communication Disorders (R01 DC009560 and R01 DC006681) and one from the National Institute of General Medical Sciences (P20 GM109023). The content of this project is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health. We appreciate the early contributions of Sandie Bass-Ringdahl in developing the experimental version of the Vocal Development Landmarks Interview. We thank Kim Oller, Carol Stoel-Gammon, and David Ertmer for their input during formative stages of the Vocal Development Landmarks Interview. We appreciate the input of Elizabeth Walker on an earlier version of this article. Finally, we are grateful for the many parents who took the time to participate in this project.

Funding Statement

This research was supported by three grants: two from the National Institute on Deafness and Other Communication Disorders (R01 DC009560 and R01 DC006681) and one from the National Institute of General Medical Sciences (P20 GM109023). The content of this project is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health. We appreciate the early contributions of Sandie Bass-Ringdahl in developing the experimental version of the Vocal Development Landmarks Interview.

Footnotes

For more information on the coding guidelines used in this study, please contact the first author.

Odds ratio is computed as e−2.907 = 0.0546 and then 1/.0546 = 18.31502.

For more information on the manual and beta version of the VDLI app, please contact the corresponding (second) author.

References

- Ambrose, S. E. , Thomas, A. , & Moeller, M. P. (2016). Assessing vocal development in infants and toddlers who are hard of hearing: A parent report tool. Journal of Deaf Studies and Deaf Education, 21(3), 237–248. https://doi.org/10.1093/deafed/enw027 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bagatto, M. P. , & Scollie, S. D. (2013). Validation of the Parents' Evaluation of Aural/Oral Performance of Children (PEACH) rating scale. Journal of the American Academy of Audiology, 24(2), 121–125. https://doi.org/10.3766/jaaa.24.2.5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bates, E. , Bretherton, I. , & Snyder, L. (1991). From first words to grammar: Individual differences and dissociable mechanisms. Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Ben-Itzhak, D. , Greenstein, T. , & Kishon-Rabin, L. (2014). Parent report of the development of auditory skills in infants and toddlers who use hearing aids. Ear and Hearing, 35(6), e262–e271. https://doi.org/10.1097/aud.0000000000000059 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cantle Moore, R. (2014). The infant monitor of vocal production: Simple beginnings. Deafness & Education International, 16(4), 218–236. https://doi.org/10.1179/1464315414Z.00000000067 [Google Scholar]

- Cicchetti, D. V. (1994). Guidelines, criteria, and rules of thumb for evaluating normed and standardized assessment instruments in psychology. Psychological Assessment, 6(4), 284–290. https://doi.org/10.1037/1040-3590.6.4.284 [Google Scholar]

- Coninx, F. , Weichbold, V. , Tsiakpini, L. , Autrique, E. , Bescond, G. , Tamas, L. , Compernol, A. , Georgescu, M. , Koroleva, I. , Le Maner-Idrissi, G. , Liang, W. , Madell, J. , Mikić, B. , Obrycka, A. , Pankowska, A. , Pascu, A. , Popescu, R. , Radulescu, L. , Rauhamäki, T. , … Brachmaier, J. (2009). Validation of the LittlEARS Auditory Questionnaire in children with normal hearing. International Journal of Pediatric Otorhinolaryngology, 73(12), 1761–1768. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijporl.2009.09.036 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Division for Early Childhood. (2007). Promoting positive outcomes for children with disabilities: Recommendations for curriculum, assessment, and program evaluation. https://www.naeyc.org/sites/default/files/globally-shared/downloads/PDFs/resources/position-statements/PrmtgPositiveOutcomes.pdf

- Dale, P. S. (1991). The validity of a parent report measure of vocabulary and syntax at 24 months. Journal of Speech and Hearing Research, 34(3), 565–571. https://doi.org/10.1044/jshr.3403.565 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dale, P. S. , Bates, E. , Reznick, J. S. , & Morisset, C. (1989). The validity of a parent report instrument of child language at twenty months. Journal of Child Language, 16(2), 239–249. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0305000900010394 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feldman, H. M. , Dale, P. S. , Campbell, T. F. , Colborn, D. K. , Kurs-Lasky, M. , Rockette, H. E. , & Paradise, J. L. (2005). Concurrent and predictive validity of parent reports of child language at ages 2 and 3 years. Child Development, 76(4), 856–868. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-8624.2005.00882.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feldman, H. M. , Dollaghan, C. A. , Campbell, T. F. , Kurs-Lasky, M. , Janosky, J. E. , & Paradise, J. L. (2000). Measurement properties of the MacArthur Communicative Development Inventories at ages one and two years. Child Development, 71(2), 310–322. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-8624.00146 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fenson, L. , Bates, E. , Dale, P. , Goodman, J. , Reznick, J. S. , & Thal, D. (2000). Measuring variability in early child language: Don't shoot the messenger. Child Development, 71(2), 323–328. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-8624.00147 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fenson, L. , Dale, P. S. , Reznick, J. S. , Bates, E. , Thal, D. J. , Bates, E. , Hartung, J. P. , Pethick, S. , & Reilly, J. S. (1993). The MacArthur Communicative Development Inventories: User's guide and technical manual. Singular. [Google Scholar]

- Fenson, L. , Dale, P. S. , Reznick, J. S. , Bates, E. , Thal, D. J. , & Pethick, S. J. (1994). Variability in early communicative development. Monographs of the Society for Research in Child Development, 59(5), 1–185. https://doi.org/10.2307/1166093 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fenson, L. , Marchman, V. , Thal, D. J. , Dale, P. S. , Reznick, J. S. , & Bates, E. (2007). Communicative Development Inventories. Brookes. [Google Scholar]

- Glascoe, F. P. (1999a). A method for deciding how to respond to parents' concerns about development and behavior. Ambulatory Child Health, 5, 197–208. [Google Scholar]

- Glascoe, F. P. (1999b). The value of parents' concerns to detect and address developmental and behavioural problems. Journal of Paediatrics and Child Health, 35(1), 1–8. https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1440-1754.1999.00342.x [Google Scholar]

- Karousou, A. , & Nikolaidou, K. (2015). Parents as informants of their children's communication and language skills: Concurrent validity study of the Communication Development Report (CDR). Hellenic Journal of Research in Education, 4, 30–52. [Google Scholar]

- Kishon-Rabin, L. , Taitelbaum-Swead, R. , Ezrati-Vinacour, R. , & Hildesheimer, M. (2005). Prelexical vocalization in normal hearing and hearing-impaired infants before and after cochlear implantation and its relation to early auditory skills. Ear and Hearing, 26(4), 17S–29S. https://doi.org/10.1097/00003446-200508001-00004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Law, J. , & Roy, P. (2008). Parental report of infant language skills: A review of the development and application of the Communicative Development Inventories. Child and Adolescent Mental Health, 13(4), 198–206. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1475-3588.2008.00503.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LENA Research Foundation. (2015). User guide LENA pro. https://cdn.shopify.com/s/files/1/0596/9601/files/LENA_Pro_User_Guide.pdf

- Lichtenstein, R. (1984). Predicting school performance of pre-school children from parent reports. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology, 12(1), 79–93. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF00913462 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lyytinen, P. , Poikkeus, A. M. , Leiwo, M. , Ahonen, T. , & Lyytinen, H. (1996). Parents as informants of their child's vocal and early language development. Early Child Development and Care, 126(1), 15–25. https://doi.org/10.1080/0300443961260102 [Google Scholar]

- MacWhinney, B. (2000). The CHILDES project: Tools for analyzing talk (3rd ed., Vol. I). Erlbaum. [Google Scholar]

- May-Mederake, B. , Kuehn, H. , Vogel, A. , Keilmann, A. , Bohnert, A. , Mueller, S. , Witt, G. , Neumann, K. , Hey, C. , Stroele, A. , Streitberger, C. , Carnio, S. , Zorowka, P. , Nekahm-Heis, D. , Esser-Leyding, B. , Brachmaier, J. , & Coninx, F. (2010). Evaluation of auditory development in infants and toddlers who received cochlear implants under the age of 24 months with the LittlEARS Auditory Questionnaire. International Journal of Pediatric Otorhinolaryngology, 74(10), 1149–1155. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijporl.2010.07.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McKnight, S. (2014). Implementing the Ages and Stages questionnaire in health visiting practice. Community Practitioner, 87(11), 28–32. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moeller, M. P. , Bass-Ringdahl, S. , Ambrose, S. E. , VanDam, M. , & Tomblin, J. B. (2011). Understanding communication outcomes: New tools and insights. In Seewald R. C. & Bamford J. M. (Eds.), A sound foundation through early amplification: Proceedings of the 2010 international conference (pp. 245–259). Phonak AG. [Google Scholar]

- Moeller, M. P. , Thomas, A. E. , Oleson, J. , & Ambrose, S. E. (2019). Validation of a parent report tool for monitoring early vocal stages in infants. Journal of Speech, Language, and Hearing Research, 62(7), 2245–2257. https://doi.org/10.1044/2019_JSLHR-S-18-0485 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nathani, S. , Ertmer, D. J. , & Stark, R. E. (2006). Assessing vocal development in infants and toddlers. Clinical Linguistics & Phonetics, 20(5), 351–369. https://doi.org/10.1080/02699200500211451 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oller, D. K. (1980). The emergence of the sounds of speech in infancy. In Yeni-Komshian G., Kavanagh J., & Ferguson C. (Eds.), Child phonology (pp. 93–112). Academic Press. https://doi.org/10.1016/B978-0-12-770601-6.50011-5 [Google Scholar]

- Oller, D. K. (2000). The emergence of the speech capacity. Erlbaum. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781410602565 [Google Scholar]

- Oller, D. K. , & Eilers, R. E. (1975). Phonetic expectation and transcription validity. Phonetica, 31(3–4), 288–304. https://doi.org/10.1159/000259675 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oller, D. K. , Eilers, R. E. , & Basinger, D. (2001). Intuitive identification of infant vocal sounds by parents. Developmental Science, 4(1), 49–60. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-7687.00148 [Google Scholar]

- Oller, D. K. , Eilers, R. E. , Neal, A. R. , & Schwartz, H. K. (1999). Precursors to speech in infancy: The prediction of speech and language disorders. Journal of Communication Disorders, 32(4), 223–245. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0021-9924(99)00013-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]