Highlights

-

•

CRLF2 overexpression associates with IKZF1 deletions that lead to a dominant-negative effect and with IKZF1 plus.

-

•

Paediatric patients with a high load expression of IK4 isoform presented higher CRLF2 transcript levels.

-

•

CRLF2 overexpression and IKZF1 deletions conferred poorer prognosis both to paediatric patients treated with RELLA05 protocol as well as to adult patients.

Keywords: CRLF2, IKZF1, Gene expression; Gene deletions; Outcome; B-ALL

Abstract

Cytokine Receptor-Like Factor 2 (CRLF2) overexpression occurs in 5-15% of B-cell precursor acute lymphoblastic leukaemia (B-ALL). In ∼50% of these cases, the mechanisms underlying this dysregulation are unknown. IKAROS Family Zinc Finger 1 (IKZF1) is a possible candidate to play a role in this dysregulation since it binds to the CRLF2 promoter region and suppresses its expression. We hypothesised that IKZF1 loss of function, caused by deletions or its short isoforms expression, could be associated with CRLF2 overexpression in B-ALL. A total of 131 paediatric and adult patients and 7 B-ALL cell lines were analysed to investigate the presence of IKZF1 deletions and its splicing isoforms expression levels, the presence of CRLF2 rearrangements or mutations, CRLF2 expression and JAK2 mutations. Overall survival analyses were performed according to the CRLF2 and IKZF1 subgroups. Our analyses showed that 25.2% of patients exhibited CRLF2 overexpression (CRLF2-high). CRLF2-high was associated with the presence of IKZF1 deletions (IKZF1del, p = 0.001), particularly with those resulting in dominant-negative isoforms (p = 0.006). Moreover, CRLF2 expression was higher in paediatric samples with high loads of the short isoform IK4 (p = 0.011). It was also associated with the occurrence of the IKZF1 plus subgroup (p = 0.004). Furthermore, patients with CRLF2-high/IKZF1del had a poorer prognosis in the RELLA05 protocol (p = 0.067, 36.1 months, 95%CI 0.0-85.9) and adult cohort (p = 0.094, 29.7 months, 95%CI 11.8–47.5). In this study, we show that IKZF1 status is associated with CRLF2-high and dismal outcomes in B-ALL patients regardless of age.

Introduction

CRLF2 (cytokine receptor factor 2) overexpression (CRLF2-high) is a marker of poor prognosis in acute lymphoblastic leukaemia (ALL). Previous studies demonstrated that patients with CRLF2-high have worse event-free survival with a higher cumulative incidence of relapse in both B-cell precursor (B-ALL) and T-cell ALL (T-ALL) [1,2]. CRLF2-high occurs in 5-15% of B-ALL and is enriched in the B-other subgroup (cases lacking commonly found genetic abnormalities) [3]. CRLF2 and IL7 receptor (IL7R) are subunits of a heterodimeric complex that binds its ligand, thymic stromal lymphopoietin (TSLP). Upon stimulation, the receptor changes its conformation and activates JAK auto-phosphorylation, mainly JAK2. The cascade is then activated, and it culminates with STATs transcriptionally regulating growth and apoptotic target genes. CRLF2-high, therefore, contributes to leukaemic transformation via JAK-STAT pathway dysregulation [4].

The mechanisms underlying CRLF2 overexpression are not yet fully elucidated. Some genomic lesions involving this gene have already been described, such as IGH-CRLF2, P2RY8-CRLF2, PAR1 region deletions and the CRLF2 F232C mutation. However, only half of the CRLF2-high cases harbour at least one of these known genetic abnormalities [5], [6], [7], [8]. Thus, for the other half of CRLF2-high cases, the mechanisms accounting for this gene's upregulation are still unknown. A previous study described that IKZF1 (IKAROS) binds to the CRLF2 promoter suppressing its expression through recruitment of chromatin methylators, which specifically increase trimethylation of histone 3 lysine 9 (H3K9me3) [9]. IKZF1 is a transcription factor that physiologically represses or activates genes involved in lymphoid differentiation through chromatin remodelling (nucleosome and deacetylase complex). Exons 4-6 of IKZF1 code DNA-binding zinc finger domains, while exon 8 codes a zinc finger dimerization domain. Alternative splicing of IKZF1 mRNA generates at least 13 different variants, including both long (IK1-IK3) and short (IK4-IK10) isoforms [10]. Those isoforms play different roles depending on their DNA-binding ability. Genome-wide studies have identified IKZF1 gene deletions (IKZF1 del) in ∼15% of paediatric and 40%-50% of adult B-ALL cases [11]. These deletions give rise to the same isoforms generated by splicing and have been consistently associated with adverse outcomes [12]. Intragenic deletions affecting exons 4–7 impair IKZF1 DNA-binding activity and it results in a dominant-negative effect, while deletions of the whole gene, as well as deletions of exons 1,2, lead to the gene haploinsufficiency. Of note, it has been shown that ∼50% of patients with CRLF2 overexpression also carry some IKZF1-associated abnormalities [5]. In the present study, we hypothesised that the role of IKZF1 on CRLF2 overexpression (even in the absence of genomic lesions involving CRLF2) could involve either the presence of IKZF1 somatic deletions or IKZF1 short isoforms in B-ALL.

Material and methods

Patients and cell lines

We evaluated 91 paediatric (0-17 years old) and 40 adult (18-67 years old) B-ALL patients retrospectively collected from six cancer centres in Brazil (INCA-RJ, IPPMG/UFRJ-RJ, IMIP-PE, HEMORIO-RJ, ProntoBaby-RJ and Hospital Amaral Carvalho-SP). Mononuclear cells from bone marrow (BM) samples at diagnosis were isolated using Ficoll-Paque (Sigma-Aldrich) and screened for common B-ALL abnormalities, such as ETV6-RUNX1, BCR-ABL1, TCF3-PBX1 and KMT2A (MLL) rearrangements, following standard procedures [13]. The local Ethics and Research Committee approved this study (CAEE #87793418.0.0000.5274 and #33709814.7.0000.5274). The main demographic and clinical characteristics of B-ALL patients are summarised in Table 1.

Table 1.

Demographic, clinical and molecular characterisation of paediatric and adult B-ALL patients.

| Paediatric B-ALL | Adult B-ALL | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Variable | n (%) | Variable | n (%) |

| Age (years) | Age (years) | ||

| <5 | 33 (36.2) | 18-40 | 25 (62.5) |

| 5-10 | 31 (34.1) | 41-60 | 11 (27.5) |

| 11-17 | 27 (29.7) | 61-67 | 4 (10.0) |

| Sex | Sex | ||

| Female | 28 (30.7) | Female | 19 (47.5) |

| Male | 63 (69.3) | Male | 21 (52.5) |

| WBC count (x109/L) | WBC count (x109/L) | ||

| <50 | 69 (75.8) | <50 | 26 (65.0) |

| >50 | 22 (24.2) | >50 | 14 (35.0) |

| Common abnormalities* | Common abnormalities* | ||

| ETV6-RUNX1 | 11 (12.5) | ETV6-RUNX1 | - |

| Hyperdiploidy | 13 (14.8) | Hyperdiploidy | 3 (8.6) |

| B-other | 40 (45.5) | B-other | 11 (31.4) |

| BCR-ABL1 | 9 (10.2) | BCR-ABL1 | 17 (48.6) |

| KMT2A-rearranged | 4 (4.5) | KMT2A-rearranged | 2 (5.7) |

| TCF3-rearranged | 10 (11.4) | TCF3-rearranged | 2 (5.7) |

| Hypodiploidy | 1 (1.1) | Hypodiploidy | - |

| IKZF1 status | IKZF1 status | ||

| Wild-type | 61 (74.4) | Wild-type | 16 (45.7) |

| Deleted | 21 (25.6) | Deleted | 19 (54.3) |

| IKZF1 plus | IKZF1 plus† | ||

| No | 14 (66.7) | No | 8 (50.0) |

| Yes | 7 (33.3) | Yes | 8 (50.0) |

| Total | 91 (100) | Total | 40 (100) |

WBC, white blood cell count.

In 3 paediatric and 4 adult cases it was not possible to define the molecular group.

In 3 IKZF1 deleted cases it was not possible to distinguish IKZF1 plus from non-plus.

To compare and confirm our findings regarding patients’ samples, we characterized B-ALL cell lines with available data on Cancer Cell Line Encyclopedia (CCLE) database (https://sites.broadinstitute.org/ccle/datasets) according to CRLF2 expression to obtain a more representative panel of cell lines with CRLF2-high and -low. Based on the CRLF2 status, we included 3 cell lines with CRLF2-high (MUTZ5, MHH-CALL4 and KOPN-8) and 4 cell lines with CRLF2-low (RS4;11, NALM6, SEM and REH) in our analysis. DNAs and cDNA aliquots of these same cell lines were kindly provided by Dr Anthony M. Ford (The Institute of Cancer Research, London, UK), Prof Rolf Marschalek (Goethe-University of Frankfurt, Germany) and Dr Wendy Stock (University of Chicago Medical Center, USA). Thus, we evaluated CRLF2 and IKZF1 genomic lesions and expression levels on these cells (Fig. S1).

Nucleic acids extraction and cDNA synthesis

Genomic DNA and total RNA were isolated from BM samples at diagnosis using TRIzolTM reagent (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, California, USA) following the manufacturer's protocol. Subsequently, to wash away any remaining salt residues and to concentrate nucleic acids, both purified DNA and RNA were precipitated using a standard ethanol-isopropanol protocol. For some samples, DNA was alternatively isolated using the QIAamp DNA Blood Mini Kit (QIAGEN, Hilden, Germany) according to the manufacturer's instructions. Quantification was performed by measuring absorbance in the 260nM range using NanoDrop™ (Thermo Scientific, Waltham, Massachusetts, USA).

An initial concentration of 1µg of RNA was treated with AmbionTM DNase I (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, California/USA) and then used to synthesize the cDNA with SuperScriptTM II Reverse Transcriptase kit (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, California/USA). To confirm cDNA integrity, a fragment of GAPDH was amplified using the following primers: GAPDH Forward: 5’ - TGACCCCTTCATTGACCTCA - 3’; GAPDH Reverse: 5’ - AGTCCTTCCACGATACCAAA - 3’.

CRLF2 and IKZF1 gene expression analyses using reverse transcription quantitative real-time PCR

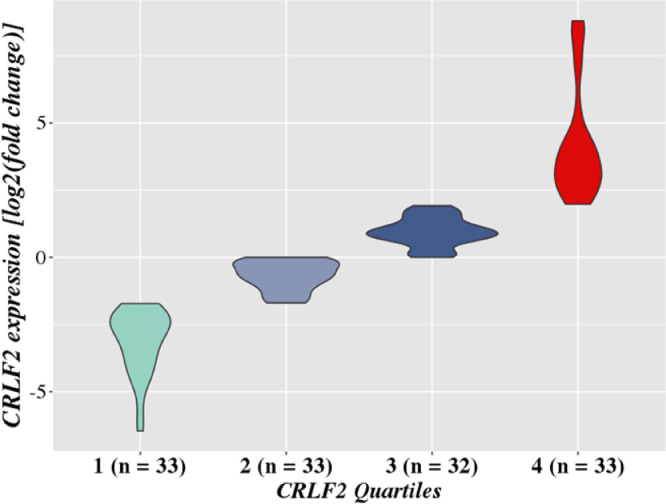

CRLF2 transcript levels were analysed by reverse transcription quantitative real-time PCR (RT-qPCR). The commercial TaqMan gene expression assays Hs00845692_m1 and Hs00939627_m1 (Applied Bio-systems, Foster City, CA) were used to target CRLF2 and the reference gene GUSB, respectively. cDNA samples were tested in duplicates using TaqMan Fast Advanced Master Mix protocol (Applied Bio-systems, Foster City, CA). All experiments were performed in the 7500 Real-Time PCR System (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, California/USA). We tested the efficacy of three different housekeeping genes (B2M, GAPDH and GUSB) and GUSB was the most suitable reference gene for our expression analysis. The threshold cycle (Ct) value was determined by the average between duplicates for both CRLF2 and GUSB. Subsequently, we calculated the ΔCt (CTCRLF2 - CTGUSB) value. Relative gene expression was defined as fold change quantified by the 2−ΔΔCt method referred to the median ΔCt of all samples [14]. All samples were categorised into quartiles according to the fold change value (quartile 1 to 4), and the samples located in the 4th quartile were categorised as CRLF2-high (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

CRLF2 gene expression data. Patients were categorised according to the quartiles of CRLF2 expression value. Samples located in the fourth quartile showed higher levels of CRLF2 expression and were considered CRLF2-high. CRLF2 expression was measured by 2-ΔΔCt and represented by the log2 (fond change).

Detection of IKZF1 transcripts using semi-quantitative reverse transcription PCR

We evaluated cDNA sequences from IKZF1 exons 1-8 by semi-quantitative reverse transcription PCR (RT‐PCR) following previously described procedures [15], [16], [17]. In summary, samples were denatured at 94 °C for 3 min, followed by 35 cycles of 30 s at 94 °C, 60 s at 63 °C, and 60 s at 72 °C, with a final extension at 72 °C for 10 min.

PCR products obtained were separated by electrophoresis using a 2% agarose gel stained with GelRed (Uniscience, Osasco, SP, Brazil) and semi-quantified with ChemiDoc XRS+ System (BioRad, Hercules, California, USA). IKZF1 relative expression was determined by gel band densitometry using ImageJ software (ImageJ, US National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, MD, USA, https://imagej.nih.gov/ij/) with GAPDH as the reference gene expression using the same primer sequence listed in the “Nucleic acids extraction and cDNA synthesis” section. Band intensity was represented as relatively arbitrary units established by the software. Samples were categorised as low load expression and high load expression based on amplicons’ patterns as shown in Fig. S2A. The presence of the expected isoforms was confirmed by Sanger sequencing (Fig. S2B). IKZF1 isoforms expression level was categorised into three groups: absent/undetectable, bands not seen in the electrophoresis; low load, bands showing low intensity; high load, bands presenting high strength in the electrophoresis. Additionally, to separate patients between low and high load, we used the median value of the expression obtained in the semi-quantitative RT-PCRs.

Mutational screening of CRLF2 and JAK2

CRLF2 and JAK2 mutations were evaluated by PCR and direct sequencing of the mutational hotspot regions of these genes, i.e. exons 6 (CRLF2) and 16 (JAK2), according to previously published methods [18,19]. PCR products were purified with Illustra GFX PCR DNA and Gel Band Purification Kit (GE Healthcare, Chicago, Illinois, USA) and sequenced on both strands using the BigDye Terminator Cycle Sequencing kit v. 3.1 (Life Technologies, Carlsbad, California, USA). Sequencing was performed in the 3130 Genetic Analyzer (Life Technologies, California, USA) and analysed with BioEdit 7.0.9 and Mutation Surveyor. The following reference sequences were used for mutational analyses: NG_034237.1 (CRLF2) and NG_009904.1 (JAK2).

Copy number alterations analyses

The presence of CNAs in IKZF1, CDKN2A/B, PAX5, EBF1, ETV6, BTG1, RB1, and the pseudoautosomal region 1 (PAR1) was evaluated by multiplex ligation-dependent probe amplification (MLPA) using SALSA MLPA P335-C1 kit (MRC Holland, Amsterdam, The Netherlands) according to the manufacturer's recommendations. The different types of IKZF1 deletions were confirmed by long-distance multiplex-PCR or the SALSA MLPA P202 B1-2 kit, as previously described [20,21]. ERG deletion was detected by SALSA MLPA P327-C1 and/or digital MLPA D007 ALL kit following manufacturer's instructions (Benard-Slagter A et al, 2017). Conventional MLPA data were analysed using Gene Marker 2.2.0 software (Soft Genetics LLC, State College, PA). Relative peak ratios between 0.8 and 1.2 were considered normal, while values below or above indicated losses or gains, respectively. Deletion of the PAR1 region was defined as the presence of a deletion in at least CSF2RA and IL3RA genes. IKZF1 deletions that co-occurred with CDKN2A/B, PAX5 or PAR1 deletion in the absence of ERG deletion were classified as IKZF1 plus. CSFRA and IL3RA deletions and retention of the CRLF2 probe were considered as P2RY8-CRLF2 fusion [22].

Detection of CRLF2 rearrangements using fluorescence in situ hybridization

Fluorescence in situ hybridization was performed in fixed cells (methanol and acetic acid solution, 3:1) using the commercial probe CRLF2 Breakapart LPH 085-S (Cytocell, Cambridge, UK). A total of 12 samples previously identified by RT-qPCR as CRLF2-high were analysed. The experiments were performed according to the manufacturer's instructions (Cytocell, Cambridge, UK). Cases were designated as CRLF2-rearranged (CRLF2-r) when one red (R), one green (G) and one fusion (F) pattern (1R1G1F) were observed in less than or equal to 5% of interphase nuclei, considering a total of 100 nuclei.

Statistical analysis

Differences in the distribution of patients’ subsets were analysed using the Chi-square or Fisher's exact test for categorical variables and the Kruskal-Wallis and Mann-Whitney test for continuous variables. The statistical tests were performed in the RStudio software version 1.2 with the package Ggpubr version 0.1.6 (CRAN-R) and p-values less than 0.05 were considered statistically significant. Ggplot2 version 3.5.1 was used to generate the graphs.

Overall survival (OS) was defined as the time in months from diagnosis to outcome (survival, last follow-up, or death). OS was estimated using the Kaplan-Meier method and differences found between tested variables were compared with the log-rank test. The variables tested were sex, white blood cell count (WBC), glucocorticoid response, common B-ALL abnormalities, IKZF1 status, CRLF2 expression, and IKZF1 isoforms. Multivariate Cox analysis was performed with variables associated with p-values of less than 0.10 in univariate analysis. OS analyses were performed using SPSS Statistics version 18.0 software (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, USA). For the survival analyses, patients were grouped according to age and treatment strategy used. Adult patients were treated with similar therapeutic protocols and called “Adult cohort”. On the other hand, paediatric patients were separated in “RELLA05 cohort” - patients homogeneously treated with RELLA05 protocol - and “Paediatric cohort” - remaining patients treated with other paediatric protocols. RELLA05 is a reduced-intensity treatment scheme developed to decrease treatment-related mortality in children diagnosed with B-ALL at very low risk of relapse. This classification is based on favourable features such as age (age greater than or equal to 1 and less than 10 years), white blood cell count less than 50 × 109/L, lack of extramedullary leukaemia, and minimal residual disease levels less than 0.01% on day 19 of induction [23,24].

Results

A total of 131 samples, 91 children and 40 adults, obtained from patients diagnosed with B-ALL were evaluated in this study. The main demographic and laboratory characterisation of these samples are described in Table 1.

To define the CRLF2-high group, patients were separated into quartiles according to CRLF2 expression data obtained from the B-ALL samples. Those located in the upper quartile were considered CRLF2-high cases (Fig. 1).

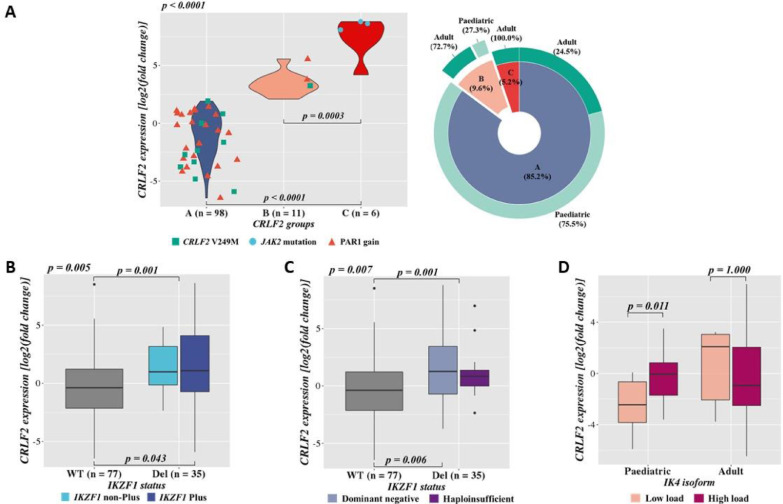

Thirty-three patients showed CRLF2-high, of which 18% presented either CRLF2-r or CRLF2 F232C mutation as the mechanisms leading to this gene deregulation. We have also assessed potential associations among different CRLF2 expression groups, CRLF2-low cases (Group A, blue), CRLF2-high wild-type (wt, Group B, light pink) and CRLF2-high with CRLF2-r and/or F232C mutation (Group C, dark pink) (Fig. 2A). Interestingly, CRLF2 expression differed significantly in these groups, even when comparing groups B and C (p < 0.001). As expected, patients in Group C had a significantly higher expression when compared to Group B (p = 0.003). Intriguingly, all patients allocated in group C were adults (greater than or equal to 18 years). In addition, we observed that only three patients harboured JAK2 mutations (R683G/R683T, grey dots). They presented CRLF2-r and were all part of Group C, accounting for 50% of this group. We also detected other molecular alterations in the CRLF2 region, such as V249M mutation and PAR1 gain (a green square and an orange triangle, respectively), both occurring in Group A and B (Fig. 2A).

Fig. 2.

CRLF2 gene expression data. A.CRLF2 expression according to different CRLF2 groups and the presence of aberrations associated with CRLF2-high. CRLF2 groups are Group A, cases with CRLF2-low (blue); Group B, cases with CRLF2-high in absence of CRLF2 genomic aberrations (CRLF2-r and/or mutation, light pink); and Group C, cases with CRLF2-high and harbouring CRLF2-r and/or F232C (dark pink). Patients with CRLF2 V249M mutation are represented by green squares and those presenting JAK2 mutations and PAR1 gain by a blue dot and orange triangle, respectively. On the right side, the multilevel doughnut chart represents the distribution of these CRLF2 groups in the age cohorts (light green for paediatric patients and dark green for adults). B. and C.CRLF2 gene expression according to IKZF1 copy number alterations. IKZF1 wt is represented in a grey box. The top p-value inside the chart (p = 0.001) represents the comparison of CRLF2 overexpression in IKZF1 wild type vs deleted samples, and the p-value outside the Kruskal Wallis test comparing the three groups demonstrated. B.CRLF2 expression according to the presence of IKZF1 plus. IKZF1 wt, deleted (IKZF1 non-Plus, light blue) and IKZF1 plus (IKZF1 Plus, dark blue), defined as IKZF1 deletions with CDKN2A/B, PAX5 or PAR1 deletion and ERG wt [22]. C. Association between CRLF2 expression and IKZF1 status according to the functional consequence of IKZF1 deletions. Deletions involving the following exons 2-7, 4-7, 4-8 and 5-6 were considered as dominant-negative (light purple) and those in 1-7, 1-8 and 2-8 exons as haploinsufficient (dark purple). D.CRLF2 expression according to IK4 isoform. Patients are categorised by age in paediatric and adult cohorts. The status of the IKZF1 short isoform, IK4, is represented in light pink, low load, and dark pink, high load. A-D.CRLF2 expression was measured by 2−ΔΔCt. Statistical analyses were performed using Kruskal Wallis and Mann-Whitney tests (For interpretation of the references to colour in this figure legend, the reader is referred to the web version of this article.).

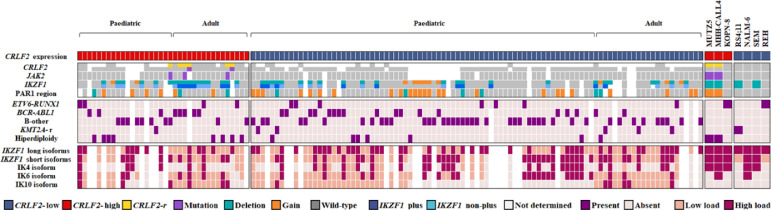

We investigated possible associations between CRLF2 gene expression and demographic-clinical variables, such as central nervous system (CNS) involvement and glucocorticoid response, but no significant results were observed (Table S1). Nevertheless, when comparing children and adults, we showed that paediatric patients had significantly higher CRLF2 expression levels (Fig. S3A; p = 0.049). Aiming to integrate the most relevant genomic investigations performed herein, we assembled an OncoPrint (Fig. 3) displaying both B-ALL patients and cell lines grouped according to their CRLF2 gene expression profile (high versus low). Additionally, patients were classified as paediatric or adult. For the CRLF2-high patients, 65.4% were classified as B-other, 30.8% as BCR-ABL1 and only one as hypodiploid. For the cell lines analyses, we had different molecular groups of B-ALL represented (B-other, KMT2A-r, ETV6-RUNX1, etc) with two out of three presenting CRLF2-high and CRLF2-r. On the other hand, none of them, regardless of the CRLF2 expression group, exhibited an IKZF1 plus profile. All cell lines expressed IKZF1 long isoforms and five out of six expressed the short ones (particularly IK4) with a high load profile.

Fig. 3.

OncoPrint showing the molecular characterisation of B-ALL samples — paediatric and adult patients and cell lines — according to CRLF2 gene expression status. Each column represents a patient or a cell line included in the study. CRLF2-r, CRLF2 rearrangement; PAR1 deletion, deletion in at least CSF2RA and IL3RA genes; IKZF1 plus, patients with IKZF1 deletions co-occurring with CDKN2A/B, PAX5 or PAR1 deletion in the absence of ERG deletion. CRLF2-r, JAK2, IKZF1 and PAR1 molecular features of cell lines were obtained from the Cancer Cell Line Encyclopedia (CCLE) database.

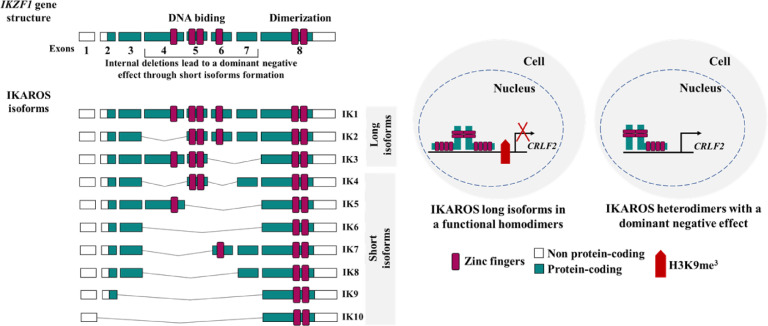

Although IKZF1 deletions were found in all three groups (A, B and C), patients with these alterations showed higher CRLF2 expression compared to the IKZF1 wt (p = 0.001) (Fig. 2B and C). Moreover, IKZF1 plus patients had a higher CRLF2 expression compared to IKZF1 wild-type cases (Fig. 2B, p = 0.043). Regarding the previous results demonstrating IKZF1 regulation in CRLF2 expression [9], we postulated that IKZF1 deletions or its unbalanced short isoforms expression would be associated with CRLF2 expression (Fig. 4). We then analysed if the different types of IKZF1 deletions were associated with CRLF2 overexpression, and we observed that the occurrence of IKZF1 deletions leading to a dominant-negative phenotype was associated with higher CRLF2 expression (Fig. 2C, p = 0.006).

Fig. 4.

Schematic representation of IKZF1 isoforms and the proposed model for dominant-negative isoforms participating in CRLF2 overexpression. Overview of the human family of IKAROS Family Zinc Finger 1 (IKZF1) gene and its isoforms (IK1 to IK10). IKZF1 isoforms that retain at least three DNA binding zinc fingers (ZF, represented by the pink bar), maintain their functional effect and are called “long isoforms” (IK1 to IK3). On the other hand, the isoforms that lose two or more of these ZFs, are unable to bind DNA, but they retain their capability to form heterodimers with IKZF1 long isoforms leading to a dominant-negative effect. Physiologically, IKZF1 directly binds to the CRLF2 promoter and suppresses its expression through enrichment of H3K9me3 (represented by the red cross in the figure) [9,10,26].

Considering our hypothesis (Fig. 4), we then evaluated if CRLF2 expression was associated with different IKZF1 isoforms. Upon categorization of patients in different age groups, paediatric patients exhibited a significantly higher CRLF2 expression in the presence of the IK4 isoform, but not of the other short isoforms (p = 0.011) (Fig. 2D and Fig. S3B-E).

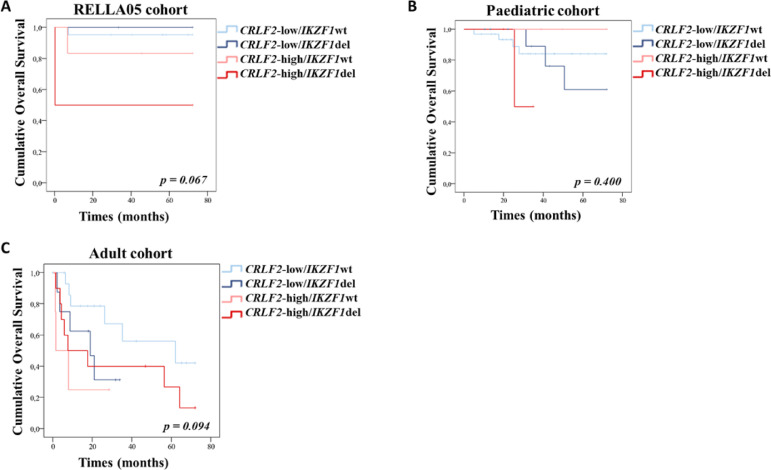

Finally, we performed overall survival (OS) analyses by grouping patients according to age and treatment protocol. The paediatric patients that uniformly received the RELLA05 protocol (n = 32) were analysed separately from the remaining paediatric cases (n = 53) (Tables S2 and S3). The 6-year OS for adults, RELLA05 and paediatric patients was 17.5 months, 72.0 months, and 36.2 months, respectively. Clinical and molecular features, such as high WBC count (p < 0.001, 42.3 months, 95%CI 25.6–59.0), presence of BCR-ABL1 fusion (p = 0.065, 45.8 months, 95%CI 36.4–55.3) and poor glucocorticoid response (p = 0.015,53.0 months, 95%CI 41.1–64.9) were associated with dismal prognosis in the paediatric cohort. KMT2A-r and CRLF2-high were also associated with poorer outcomes in RELLA05 (p = 0.064, 39.6 months, 95%CI 0.0-84.5, and p = 0.067, 54.9 months, 95%CI 34.3–75.5, respectively) and adult cohorts (p = 0.007, 4.2 months, 95%CI 0.0-8.5, and p = 0.072, 26.5 months, 95%CI 11.5–41.6, respectively). The occurrence of IKZF1 deletions was associated with an inferior outcome in adults, but not in paediatric patients (p = 0.042, 29.6 months, 95%CI 16.4-42.7). IKZF1 deletions had a negative impact on the prognosis of the adult cohort regardless of the treatment received (either BFM or any other adult protocol; p = 0.813, 27.5 months vs 31.5 months). A combined analysis of CRLF2/IKZF1 status revealed that CRLF2-high/IKZF1 deleted patients had worse prognosis in RELLA05 (p = 0.067, 36.1 months, 95%CI 0.0-85.9) and adult cohorts (p = 0.094, 29.7 months, 95%CI 11.8–47.5) (Fig. 5). No significant difference in OS was observed for the expression of IK4, IK6, IK10 and IKZF1 long isoforms. Nonetheless, the combination of low loading short isoforms with CRLF2-high profile had a negative impact in OS of RELLA05 paediatric and adult cohorts (p < 0.001 and p = 0.006, respectively). Furthermore, the inferior outcome observed in adults with CRLF2-high is maintained even when patients with CRLF2-r or F232C mutations are excluded (p = 0.041). A multivariate Cox analysis including the variables significantly associated with survival was performed to evaluate possible independent prognostic factors. We observed that KMT2A-r and IKZF1 deletions impact the prognosis of adult patients independently of other variables (p = 0.017, HR = 61.3, 95%CI 2.1–1778.8 and p = 0.022, HR = 34.6, 95%CI 1.7–724.6, respectively), whereas for paediatric patients, only high WBC count remained significant in the multivariate analysis (p = 0.017, HR = 2.7, 95%CI 1.2–6.2).

Fig. 5.

Impact of CRLF2 expression/IKZF1 status in for on outcome of B-ALL patients. Overall survival according to the combination of CRLF2 expression and IKZF1 status in A. RELLA05 B. paediatric and C. adult cohorts. Wt, wild-type; del, deleted.

Discussion

CRLF2 was overexpressed in 25.2% of cases included in our study and the majority of them were classified as either BCR-ABL1 or B-other, in agreement with literature reports [3,4]. Surprisingly, molecular alterations previously associated with CRLF2 overexpression, such as V249M mutation and PAR1 gain, were identified in patients with CRLF2 low expression. This indicates that these alterations might not necessarily lead to CRLF2 overexpression in B-ALL. Subsequently, characterising the type of IKZF1 deletions, we demonstrated that those resulting in dominant-negative phenotypes were associated with higher expression of CRLF2. Aware that dominant-negative proteins sequester IKZF1 long isoforms, this result supports the assumption that the presence of these types of deletions would lead to a decreased IKZF1 binding to a CRLF2 promoter, culminating in CRLF2 overexpression (Fig. 4). However, functional experiments are necessary to confirm this hypothesis. The finding that CRLF2 expression was higher in the IKZF1 plus when compared to the IKZF1 wt subgroup goes along with the idea of both being poor prognostic markers and more frequently found within the ‘B-other’ subgroup [2,9,10,13].

We then investigated the impact of different IKZF1 isoforms on CRLF2 expression. Here, we observed a positive association between the presence of IK4 short isoform and CRLF2-high in paediatric patients only, reinforcing our hypothesis pictured in Fig. 4. However, we did not find any association between IK6 and IK10 with CRLF2 expression. Interestingly, we also identified a high load of IK4 in the B-ALL cell lines that harbour CRLF2 overexpression, corroborating with the results obtained from the patients' samples. Nonetheless, we cannot completely rule out the role of the other IKZF1 short isoforms, since CNA analyses revealed an association of IKZF1 deletions that lead to the formation of dominant-negative isoforms, specifically IK6 and IK10. Moreover, our data resulted from a single experimental approach, which may present some intrinsic limitations. On the other hand, this semi-quantitative method was validated as a feasible test to detect IKZF1 alterations as well as a practical risk prognostic tool [16,17]. Additionally, former studies have also shown a biological link between IKZF1 and CRLF2 in both B- and T-ALL [8,9,18,25].

Herein, we demonstrated for the first time the prognostic impact of the cooccurrence of CRLF2-high/IKZF1del in the RELLA05 Brazilian protocol. The RELLA05 Brazilian protocol for the treatment of children diagnosed with B-ALL was developed for patients with a low risk of relapse and managed to reduce the toxic effects of the therapy [24]. Therefore, our findings may contribute to further benefit the risk stratification of this therapeutic protocol.

Of note, we found that the low load of IKZF1 short isoforms combined with CRLF2 overexpression conferred a poorer prognosis. This effect seems to mainly reflect the impact of CRLF2 high transcript levels, because of the small number of cases with a low load of IKZF1 short isoforms. In addition, previous studies demonstrated the prognostic impact of IKZF1del/CRLF2-high in other series of cases, mainly in paediatric patients with high-risk B-ALL [6], [7], [8]. Our data revealed that the co-occurrence of these alterations culminates in a poor prognosis regardless of age, even in patients with a very low risk of relapse. Raca et al. [27] recently demonstrated that the occurrence of IGH-CRLF2 and IKZF1 deletions is more frequent in paediatric Hispanic and Latin populations with B-ALL, providing a biological rationale for the higher death rate in these patients. Following these results, the authors highlighted the importance of testing Hispanic/Latino children for these alterations as a strategy to improve the prognosis of B-ALL, as well as reducing social inequalities [27]. Indeed, in our study, we identified a higher frequency of IKZF1 deletions in paediatric Brazilian patients than what is commonly found in other populations (25 vs 15%, respectively) [19]. We also demonstrated that the higher CRLF2 transcript levels, independent of CRLF2-r or mutations, in concomitance with IKZF1 deletions were associated with a worse outcome. Therefore, our data aligns with the proposal that the detection of these molecular abnormalities is important to improve the prognosis of these populations. Altogether, these data reinforce the need to develop and test therapeutic strategies which restore IKAROS function while targeting CRLF2 signalling pathways, as a means to improve the prognosis of B-ALL in Brazilian patients with B-ALL.

Some pitfalls must be considered, such as the absence of event-free survival information and the limited number of patients after stratifications, which precluded us from performing more detailed prognosis analyses.

In summary, our findings demonstrate that CRLF2-high is associated with the occurrence of dominant-negative IKZF1 deletions in B-ALL patients and confers a poor outcome in these patients. Ours and other data support the need for further exploring a functional regulation between those genes, as well as including these molecular biomarkers in protocols designed for these populations with known increased frequency.

CRediT authorship contribution statement

Ana Luiza Tardem Maciel: Conceptualization, Methodology, Validation, Formal analysis, Investigation, Writing – original draft, Visualization. Thayana da Conceição Barbosa: Conceptualization, Methodology, Validation, Formal analysis, Investigation, Writing – original draft, Visualization. Caroline Barbieri Blunck: Methodology, Formal analysis, Investigation, Writing – original draft. Karolyne Wolch: Methodology, Formal analysis, Investigation, Writing – original draft. Amanda de Albuquerque Lopes Machado: Methodology, Formal analysis, Investigation, Writing – original draft. Elaine Sobral da Costa: Resources, Writing – review & editing. Lavínia Lustosa Bergier: Resources, Writing – review & editing. Márcia Trindade Schramm: Resources, Writing – review & editing. Maura Rosane Valério Ikoma-Coltutato: Resources, Writing – review & editing. Mecneide Mendes Lins: Resources, Writing – review & editing. Thais Ferraz Aguiar: Resources, Writing – review & editing. Marcela Braga Mansur: Conceptualization, Methodology, Investigation, Resources, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing, Project administration, Funding acquisition. Mariana Emerenciano: Conceptualization, Methodology, Investigation, Resources, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing, Project administration, Funding acquisition.

CRediT authorship contribution statement

Ana Luiza Tardem Maciel: Conceptualization, Methodology, Validation, Formal analysis, Investigation, Writing – original draft, Visualization. Thayana da Conceição Barbosa: Conceptualization, Methodology, Validation, Formal analysis, Investigation, Writing – original draft, Visualization. Caroline Barbieri Blunck: Methodology, Formal analysis, Investigation, Writing – original draft. Karolyne Wolch: Methodology, Formal analysis, Investigation, Writing – original draft. Amanda de Albuquerque Lopes Machado: Methodology, Formal analysis, Investigation, Writing – original draft. Elaine Sobral da Costa: Resources, Writing – review & editing. Lavínia Lustosa Bergier: Resources, Writing – review & editing. Márcia Trindade Schramm: Resources, Writing – review & editing. Maura Rosane Valério Ikoma-Coltutato: Resources, Writing – review & editing. Mecneide Mendes Lins: Resources, Writing – review & editing. Thais Ferraz Aguiar: Resources, Writing – review & editing. Marcela Braga Mansur: Conceptualization, Methodology, Investigation, Resources, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing, Project administration, Funding acquisition. Mariana Emerenciano: Conceptualization, Methodology, Investigation, Resources, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing, Project administration, Funding acquisition.

Declaration of Competing Interest

The authors have no competing interests.

Acknowledgments

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank the patients and their families who agreed to be involved in the study. ALTM has been supported by CAPES Foundation. TCB is supported by the Ministry of Health (INCA-Brazil). ME is supported by Brazilian National Counsel of Technological and Scientific Development-CNPq (PQ-311220/2020-7) and Fundação Carlos Chagas Filho de Amparo à Pesquisa do Estado do Rio de Janeiro-FAPERJ (E_26/203.214-2017; E-26-010.101072-2018; and E-26/010.002187-2019) research grants. MBM was supported by the Ministry of Health (INCA-Brazil) and is currently funded by a John Goldman Fellowship from leukaemia UK (University of Oxford-UK).

Data availability statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available upon reasonable request to the corresponding authors.

Footnotes

Supplementary material associated with this article can be found, in the online version, at doi:10.1016/j.tranon.2021.101291.

Contributor Information

Marcela Braga Mansur, Email: mmansur@inca.gov.br.

Mariana Emerenciano, Email: memerenciano@inca.gov.br.

Appendix. Supplementary materials

References

- 1.Chen I.M., Harvey R.C., Mullighan C.G., Gastier-Foster J., Wharton W., Kang H., Borowitz M.J., Camitta B.M., Carroll A.J., Devidas M., Pullen D.J., Payne-Turner D., Tasian S.K., Reshmi S., Cottrell C.E., Reaman G.H., Bowman W.P., Carroll W.L., Loh M.L., Winick N.J., Willman C.L. Outcome modeling with CRLF2, IKZF1, JAK, and minimal residual disease in pediatric acute lymphoblastic leukemia: a Children's Oncology Group study. Blood. 2012;119:3512–3522. doi: 10.1182/blood-2011-11-394221. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Palmi C., Savino A.M., Silvestri D., Bronzini I., Cario G., Paganin M., Buldini B., Galbiati M., Muckenthaler M.U., Bugarin C., Mina P.Della, Nagel S., Barisone E., Casale F., Locatelli F., Lo Nigro L., Micalizzi C., Parasole R., Pession A., Putti M.C., Cazzaniga G. CRLF2 over-expression is a poor prognostic marker in children with high risk T-cell acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Oncotarget. 2016;7:59260–59272. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.10610. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Moorman A.V. New and emerging prognostic and predictive genetic biomarkers in B-cell precursor acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Haematologica. 2016;101:407–416. doi: 10.3324/haematol.2015.141101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Russell L.J., Capasso M., Vater I., Akasaka T., Bernard O.A., Calasanz M.J., Chandrasekaran T., Chapiro E., Gesk S., Griffiths M., Guttery D.S., Haferlach C., Harder L., Heidenreich O., Irving J., Kearney L., Nguyen-Khac F., Machado L., Minto L., Majid A., Harrison C.J. Deregulated expression of cytokine receptor gene, CRLF2, is involved in lymphoid transformation in B-cell precursor acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Blood. 2009;114:2688–2698. doi: 10.1182/blood-2009-03-208397. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Roberts K.G., Mullighan C.G. Genomics in acute lymphoblastic leukaemia: insights and treatment implications. Nat. Rev. Clin. Oncol. 2015;12:344–357. doi: 10.1038/nrclinonc.2015.38. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.van der Veer A., Waanders E., Pieters R., Willemse M.E., Van Reijmersdal S.V., Russell L.J., Harrison C.J., Evans W.E., van der Velden V.H.J., Hoogerbrugge P.M., Van Leeuwen F., Escherich G., Horstmann M.A., Mohammadi Khankahdani L., Rizopoulos D., De Groot-Kruseman H.A., Sonneveld E., Kuiper R.P., Den Boer M.L. Independent prognostic value of BCR-ABL1-like signature and IKZF1 deletion, but not high CRLF2 expression, in children with B-cell precursor ALL. Blood. 2013;122:2622–2629. doi: 10.1182/blood-2012-10-462358. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Yamashita Y., Shimada A., Yamada T., Yamaji K., Hori T., Tsurusawa M., Watanabe A., Kikuta A., Asami K., Saito A.M., Horibe K. IKZF1 and CRLF2 gene alterations correlate with poor prognosis in Japanese BCR-ABL1-negative high-risk B-cell precursor acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Pediatr. Blood Cancer. 2013;60:1587–1592. doi: 10.1002/pbc.24571. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cui L., Gao C., Wang C.J., Zhao X.X., Li W.J., Li Z.G., Zheng H.Y., Wang T.Y., Zhang R.D. Combined analysis of IKZF1 deletions and CRLF2 expression on prognostic impact in pediatric B-cell precursor acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Leuk. Lymphoma. 2021;62:410–418. doi: 10.1080/10428194.2020.1832668. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ge Z., Gu Y., Zhao G., Li J., Chen B., Han Q., Guo X., Liu J., Li H., Yu M.D., Olson J., Steffens S., Payne K.J., Song C., Dovat S. High CRLF2 expression associates with IKZF1 dysfunction in adult acute lymphoblastic leukemia without CRLF2 rearrangement. Oncotarget. 2016;7:49722–49732. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.10437. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Vshyukova V., Valochnik A., Meleshko A. Expression of aberrantly spliced oncogenic Ikaros isoforms coupled with clonal IKZF1 deletions and chimeric oncogenes in acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Blood Cells Mol. Dis. 2018;71:29–38. doi: 10.1016/j.bcmd.2018.02.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kuiper R.P., Schoenmakers E.F.P.M., van Reijmersdal S.V., Hehir-Kwa J.Y., van Kessel A.G., van Leeuwen F.N., Hoogerbrugge P.M. High-resolution genomic profiling of childhood ALL reveals novel recurrent genetic lesions affecting pathways involved in lymphocyte differentiation and cell cycle progression. Leukemia. 2007;21:1258–1266. doi: 10.1038/sj.leu.2404691. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Mullighan C.G., Su X., Zhang J., Radtke I., Phillips L.A.A., Miller C.B., Ma J., Liu W., Cheng C., Schulman B.A., Harvey R.C., Chen I.-M., Clifford R.J., Carroll W.L., Reaman G., Bowman W.P., Devidas M., Gerhard D.S., Yang W., Relling M.V. Children's Oncology Group, deletion of IKZF1 and prognosis in acute lymphoblastic leukemia. N. Engl. J. Med. 2009;360:470–480. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0808253. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.van Dongen J.J.M., Macintyre E.A., Gabert J.A., Delabesse E., Rossi V., Saglio G., Gottardi E., Rambaldi A., Dotti G., Griesinger F., Parreira A., Gameiro P., Diáz M.G., Malec M., Langerak A.W., San Miguel J.F., Biondi A. Standardized RT-PCR analysis of fusion gene transcripts from chromosome aberrations in acute leukemia for detection of minimal residual disease. Leukemia. 1999;13:1901–1928. doi: 10.1038/sj.leu.2401592. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Livak K.J., Schmittgen T.D. Analysis of relative gene expression data using real-time quantitative PCR and the 2(-Delta Delta C(T)) Method. Methods. 2001;25:402–408. doi: 10.1006/meth.2001.1262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Mirza M., Shaughnessy E., Hurley J.K., Vanpatten K.A., Pestano G.A., He B., Weber G.F. Osteopontin-c is a selective marker of breast cancer. Int. J. Cancer. 2008;122:889–897. doi: 10.1002/ijc.23204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Tokunaga K., Yamaguchi S., Iwanaga E., Nanri T., Shimomura T., Suzushima H., Mitsuya H., Asou N. High frequency of IKZF1 genetic alterations in adult patients with B-cell acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Eur. J. Haematol. 2013;91:201–208. doi: 10.1111/ejh.12155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Moreira L.B.P., de P. Queiróz R., Suazo V.K., Perna E., Brandalise S.R., Yunes J.A., Tone L.G., Scrideli C.A. Detection by a simple and cheaper methodology of Ik6 and Ik10 isoforms of the IKZF1 gene is highly associated with a poor prognosis in B-lineage paediatric acute lymphoblastic leukaemia. Br. J. Haematol. 2019;187:e58–e61. doi: 10.1111/bjh.16172. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Pastorczak A., Sedek L., Braun M., Madzio J., Sonsala A., Twardoch M., Fendler W., Nebral K., Taha J., Bielska M., Gorniak P., Romiszewska M., Matysiak M., Derwich K., Lejman M., Kowalczyk J., Badowska W., Niedzwiecki M., Kazanowska B., Muszynska-Roslan K., Młynarski W. Surface expression of cytokine receptor-like factor 2 increases risk of relapse in pediatric acute lymphoblastic leukemia patients harboring IKZF1 deletions. Oncotarget. 2018;9:25971–25982. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.25411. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Steeghs E.M.P., Jerchel I.S., de Goffau-Nobel W., Hoogkamer A.Q., Boer J.M., Boeree A., van de Ven C., Koudijs M.J., Besselink N.J.M., de Groot-Kruseman H.A., Zwaan C.M., Horstmann M.A., Pieters R., den Boer M.L. JAK2 aberrations in childhood B-cell precursor acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Oncotarget. 2017;8:89923–89938. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.21027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Meyer C., Zur Stadt U., Escherich G., Hofmann J., Binato R., Barbosa T.C., Emerenciano M., Pombo-de-Oliveira M.S., Horstmann M., Marschalek R. Refinement of IKZF1 recombination hotspots in pediatric BCP-ALL patients. Am. J. Blood Res. 2013;3:165–173. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Barbosa T.C., Terra-Granado E., Quezado Magalhães I.M., Neves G.R., Gadelha A., Guedes Filho G.E., Souza M.S., Melaragno R., Emerenciano M., Pombo-de-Oliveira M.S. Frequency of copy number abnormalities in common genes associated with B-cell precursor acute lymphoblastic leukemia cytogenetic subtypes in Brazilian children. Cancer Genet. 2015;208:492–501. doi: 10.1016/j.cancergen.2015.06.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Stanulla M., Dagdan E., Zaliova M., Möricke A., Palmi C., Cazzaniga G., Eckert C., Te Kronnie G., Bourquin J.P., Bornhauser B., Koehler R., Bartram C.R., Ludwig W.-D., Bleckmann K., Groeneveld-Krentz S., Schewe D., Junk S.V., Hinze L., Klein N., Kratz C.P., International BFM Study Group IKZF1plus defines a new minimal residual disease-dependent very-poor prognostic profile in pediatric B-cell precursor acute lymphoblastic leukemia. J. Clin. Oncol. 2018;36:1240–1249. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2017.74.3617. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Howard S.C., Pedrosa M., Lins M., Pedrosa A., Pui C.H., Ribeiro R.C., Pedrosa F. Establishment of a pediatric oncology program and outcomes of childhood acute lymphoblastic leukemia in a resource-poor area. JAMA. 2004;291:2471–2475. doi: 10.1001/jama.291.20.2471. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Pedrosa F., Coustan-Smith E., Zhou Y., Cheng C., Pedrosa A., Lins M.M., Pedrosa M., Lucena-Silva N., de L. Ramos A.M., Vinhas E., Rivera G.K., Campana D., Ribeiro R.C. Reduced-dose intensity therapy for pediatric lymphoblastic leukemia: long-term results of the Recife RELLA05 pilot study. Blood. 2020;135:1458–1466. doi: 10.1182/blood.2019004215. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Schmäh J., Fedders B., Panzer-Grümayer R., Fischer S., Zimmermann M., Dagdan E., Bens S., Schewe D., Moericke A., Alten J., Bleckmann K., Siebert R., Schrappe M., Stanulla M., Cario G. Molecular characterization of acute lymphoblastic leukemia with high CRLF2 gene expression in childhood. Pediatr. Blood Cancer. 2017:64. doi: 10.1002/pbc.26539. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Marke R., van Leeuwen F.N., Scheijen B. The many faces of IKZF1 in B-cell precursor acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Haematologica. 2018;103:565–574. doi: 10.3324/haematol.2017.185603. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Raca G., Abdel-Azim H., Yue F., Broach J., Payne J.L., Reeves M.E., Gowda C., Schramm J., Desai D., Dovat E., Hu T., Berg A.S., Bhojwani D., Payne K.J., Dovat S. Increased Incidence of IKZF1 deletions and IGH-CRLF2 translocations in B-ALL of Hispanic/Latino children-a novel health disparity. Leukemia. 2021 doi: 10.1038/s41375-021-01133-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available upon reasonable request to the corresponding authors.