Abstract

During a 1-year study we observed that both aerobic and anaerobic blood culture bottles from patients were negative by the BacT/Alert system during a 7-day incubation period. However, upon subcultivation of negative bottles, growth of Pseudomonas aeruginosa was detectable. In an attempt to explain this observation, aerobic BacT/Alert Fan bottles were seeded with a defined inoculum (0.5 McFarland standard; 1 ml) of Escherichia coli, Klebsiella pneumoniae, Serratia marcescens, P. aeruginosa, Stenotrophomonas maltophilia, or Acinetobacter baumannii. Half of the inoculated bottles were loaded into the BacT/Alert system immediately, and the remainder were preincubated for 4, 8, 16, and 24 h at 36°C. With preincubation all bottles seeded with the Enterobacteriaceae signaled positive during the next 1.5 h. Organisms in bottles seeded with the nonfermentative species P. aeruginosa and A. baumannii remained undetected by the BacT/Alert system for 7 days. S. maltophilia was detected if the preincubation time was equal or less than 8 h. Without preincubation all bottles seeded with the Enterobacteriaceae or nonfermentative species signaled positive. Since nonfermentative species seem to enter a state of bacteriostasis within the preincubation period, we reasoned that an unknown factor is consumed. Accordingly, a smaller inoculum should allow the detection of nonfermentative species, even after preincubation, and serial dilutions of P. aeruginosa were detected in preincubated bottles. In this case preincubated bottles signaled positive faster than bottles without preincubation. We conclude that all bottles from clinical settings should be subcultured prior to loading to avoid false negatives. An alternative may be preincubation at room temperature.

Detection of bacteremia is one of the most important functions of clinical microbiology laboratories. Due to the high morbidity and mortality associated with this disease process, rapid detection and identification of clinically relevant microorganisms in blood cultures remain most important (1).

In response to these demands, the development of continuously monitoring blood culture systems took place. The BacT/Alert system (Organon Teknika, Eppelheim, Germany) is one of the fully automated blood culture systems (8). The BacT/Alert software examines the readings from each bottle to determine if there is evidence for bacterial growth. The detection system accomplishes this by using three types of measurements of the CO2 level: (i) the present CO2 level in the bottle, (ii) the rate of CO2 production, and (iii) the acceleration of this rate. The combination of the three measurements allows the system a high degree of accuracy and specificity (8).

Ideally, blood culture bottles should be entered into a continuously monitoring blood culture system as soon as possible. Delays in entry of blood culture bottles may be due to collection from outlying hospitals, limited instrument capacity, or collection of blood samples during the night. Under these circumstances, it is recommended that the blood culture bottles should be stored at 36°C until arrival in the laboratory. However, this treatment of blood culture bottles prior to loading into the BacT/Alert raises the question of whether the system is still able to detect positive blood culture bottles.

During a 1-year study involving 8,107 blood culture bottles, we observed that aerobic and anaerobic blood culture bottles from patients were negative by the BacT/Alert system during a 7-day incubation period but that subcultivation on blood agar plates resulted in growth of Pseudomonas aeruginosa in 15 cases. In an attempt to find an explanation for this observation, we speculated that the delayed entry and preincubation at 36°C is responsible for the failure of the BacT/Alert computer algorithm to detect certain positive cultures.

Therefore, we investigated the effect of delayed entry and how preincubation at 36°C influences the sensitivity of the BacT/Alert blood culture system.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Study design.

We used aerobic BacT/Alert Fan bottles (Organon Teknika) throughout the experimental study. The bottles contain brain heart infusion (2.8% wt/vol), sodium polyethanolsulfonate (0.05%), pyridoxine-HCl (0.001%, wt/vol), menadione (0.00005%, wt/vol), hemin (0.0005%, wt/vol), activated charcoal (8.5%), l-cysteine and other complex amino acids, and carbohydrate substrates in purified water. Bottles were labeled in duplicate with incubation time, temperature, and delayed-entry time. A suspension (equivalent to a 0.5 McFarland standard [referred to hereafter as McFarland 0.5]) of the organism to be tested (Escherichia coli, Klebsiella pneumoniae, Serratia marcescens, P. aeruginosa, Stenotrophomonas maltophilia, or Acinetobacter baumannii) was prepared, and 1 ml of each organism suspension was added to the specific bottles. One hundred microliters per bottle was removed and plated on 5% Columbia blood agar plates (Becton Dickinson, Heidelberg, Germany) to determine the number of CFU per bottle. After overnight incubation at 36°C, colony counts were performed. Half of the bottles were loaded into the BacT/Alert immediately, and the other half were incubated at 36°C for 4, 8, 16, and 24 h (this was recommended by the manufacturer for delayed-entry bottles). All bottles were vented just prior to inoculation. Bottles remained on the BacT/Alert until they signaled positive or until 7 days elapsed, and the time from loading to detection was determined for each bottle. Bottles that failed to signal were subcultured on blood agar plates after being unloaded.

In a second experiment a suspension (McFarland 0.5) of the organisms to be tested (E. coli, P. aeruginosa, S. maltophilia, or A. baumannii) was prepared, and serial dilutions (1:100, 1:1,000, and 1:10,000) were performed. BacT/Alert Fan bottles were inoculated with 1 ml of each dilution, and 100 μl of suspension from each bottle was removed and subcultured on blood agar plates to determine the number of CFU. Half of the inoculated bottles were loaded into the BacT/Alert immediately, and the remainder were preincubated for 8 h at 36°C. The rest of the procedure was the same as described for the first experiment.

In a third experiment a suspension (McFarland 0.5) of P. aeruginosa was prepared, and dilutions of 1:1,000, 1:10,000, and 1:100,000 plus 10 ml of blood from normal human volunteers were inoculated in each blood culture bottle. One hundred microliters of suspension from each bottle was removed and subcultured on blood agar plates to determine the number of CFU. Half of the inoculated bottles were loaded into the BacT/Alert immediately, and the remainder were preincubated for 8 h at 36°C. The rest of the procedure was the same as described for the first experiment.

Evaluation of specimens.

This study was conducted from May 1998 until April 1999 at the University Hospital “Klinikum rechts der Isar,” Technical University of Munich. Aerobic and anaerobic BacT/Alert Fan bottles were used on all wards of the hospital. We included anaerobic bottles in the clinical study to obtain the whole spectrum of clinically relevant bacteria. The composition of the anaerobic medium is identical to that of the aerobic medium described above. The difference between aerobic and anaerobic bottles is that aerobic bottles are enriched with O2, whereas anaerobic bottles are enriched with CO2 and N2. The time needed for the blood culture bottles to arrive in the laboratory ranged from 30 min to 12 h. It is common within the clinic to incubate the blood culture bottles at 36°C in case they cannot be immediately delivered to the laboratory. On arrival in the laboratory, aliquots were taken from each blood culture bottle (aerobic and anaerobic bottles) obtained from the medical and surgical care wards and subcultured onto adequate medium (blood agar incubated at 36°C) prior to loading into the BacT/Alert system. Bottles remained on the BacT/Alert until they signaled positive or until 7 days elapsed. Bottles that failed to signal were subcultured on blood agar plates after being unloaded. For all positive bottles the bacterial species and time from loading to detection were determined. In parallel, the presence of antibiotics in clinical blood culture bottles was analyzed by adding a drop of the blood culture medium to agar holes of Mueller-Hinton plates inoculated with Bacillus subtilis. After incubation overnight, the plates were checked for growth inhibition of the indicator bacteria.

RESULTS

Clinical study.

A total of 8,107 blood culture bottles were obtained during the study period. Of these, 1,078 blood culture bottles (aerobic or anaerobic bottles) were positive as determined by the instrument in combination with subcultures, and 605 bottles were considered clinically relevant. Accordingly, cases where both bottles for a patient were positive were counted only once, and bottles growing microorganisms like propionibacteria or lactobacilli were not counted. Of the 605 clinically relevant species detected, most of them (62.9%) were gram-positive bacteria; 35.2% were gram-negative bacteria, and only 1.8% were Candida spp. (Table 1). All gram-positive bacteria and species that belong to the Enterobacteriaceae (26.9%) could be detected by the BacT/Alert system. In contrast, 27.3% of the Candida spp. and 40.5% of all nonfermentative species remained undetected by the system. A total of 46.9% of all P. aeruginosa-positive blood culture bottles were not detected by the BacT/Alert system, but all clinical samples with these bacterial species were positive on initial or terminal subculture. The false negatives enumerated in Table 1 were instrument negative for both aerobic and anaerobic blood culture bottles. Evaluation of these patients showed that all of them were critically ill due to cancer, sepsis, or large operations like hemicolectomy or total gastrectomy. All patients suffered from fever, with a body temperature of between 38.5 and 40.5°C, several of them received antibiotics like piperacillin-combactam, mezlocillin-combactam, gentamicin, vancomycin, and others, which was documented for 10 of the 15 false-negative P. aeruginosa cases. Evaluation of the false-negative blood culture bottles for the presence of antibiotics revealed that three out of nine tested cases contained antibiotics. In the other six false-negative cases, the presence of antibiotics could not be demonstrated. However, in 4 of 14 tested and true-positive cases, we could also demonstrate the presence of antibiotics. In conclusion, the instrument is unable to detect more than 46% of cases of clinically relevant bacteremias due to P. aeruginosa.

TABLE 1.

Evaluation of clinically relevant microorganisms in BacT/Alert Fan bottles (aerobic and anaerobic)

| Microorganism(s) | Total

|

Detected

|

Not detected

|

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No. of cases | % | No. of cases | % | No. of cases | % | |

| Gram-positive bacteria | 381 | 62.9 | 381 | 100 | 0 | 0 |

| S. aureus | 54 | 8.9 | 54 | 100 | 0 | 0 |

| Coagulase-negative staphylococci | 216 | 35.7 | 216 | 100 | 0 | 0 |

| Viridans group streptococci | 37 | 6.1 | 37 | 100 | 0 | 0 |

| Streptococcus pneumoniae | 9 | 1.5 | 9 | 100 | 0 | 0 |

| Beta-hemolytic streptococci | 9 | 1.5 | 9 | 100 | 0 | 0 |

| Enterococcus spp. | 45 | 7.4 | 45 | 100 | 0 | 0 |

| Clostridium spp. | 11 | 1.8 | 11 | 100 | 0 | 0 |

| Gram-negative bacteria | 213 | 35.2 | 198 | 93.0 | 15 | 7.0 |

| Enterobacteriaceae | 163 | 26.9 | 163 | 100 | 0 | 0 |

| E. coli | 83 | 13.7 | 83 | 100 | 0 | 0 |

| Klebsiella spp. | 45 | 7.4 | 45 | 100 | 0 | 0 |

| Proteus and Morganella spp. | 9 | 1.5 | 9 | 100 | 0 | 0 |

| Enterobacter and Citrobacter spp. | 19 | 3.1 | 19 | 100 | 0 | 0 |

| Salmonella spp. | 2 | 0.3 | 2 | 100 | 0 | 0 |

| Serratia and Hafnia spp. | 5 | 0.8 | 5 | 100 | 0 | 0 |

| Bacteroides spp. | 10 | 1.7 | 10 | 100 | 0 | 0 |

| Nonfermentative species | 37 | 6.1 | 22 | 59.5 | 15 | 40.5 |

| P. aeruginosa | 32 | 5.3 | 17 | 53.1 | 15 | 46.9 |

| Acinetobater spp. | 5 | 0.8 | 5 | 100 | 0 | 0 |

| Other | 3 | 0.5 | 3 | 100 | 0 | 0 |

| Candida spp. | 11 | 1.8 | 8 | 72.7 | 3 | 27.3 |

| All microorganisms | 605 | 100 | 587 | 97.0 | 18 | 3.0 |

Effect of delayed-entry time on detection of gram-negative bacterial strains.

With preincubation times of 4 h (done only with E. coli and nonfermentative bacteria) and of 8, 16, and 24 h at 36°C, all bottles seeded with E. coli, K. pneumoniae, and S. marcescens signaled positive during the next 1.5 h after loading into the BacT/Alert system (Table 2). The average detection times for E. coli were 1.0 h (4-h preincubation), 1.2 h (8- and 16-h preincubations), and 1.5 h (24-h preincubation); those for K. pneumoniae were 1.2 h (8- and 16-h preincubations) and 1.1 h (24-h preincubation); and those for S. marcescens were 1.2 h (8- and 16-h preincubations) and 1.0 h (24-h preincubation). For all three Enterobacteriaceae the average detection time after 8, 16, and 24 h of preincubation was 1.2 h. In contrast, organisms in bottles seeded with P. aeruginosa and A. baumannii were not detected by the BacT/Alert system. Even with shorter preincubation times, down to 4 h, bottles failed to signal positive for these species. Organisms in bottles seeded with S. maltophilia were undetected with preincubation times of longer than 8 h. After preincubation times of 8 and 4 h, the bottles signaled positive but the time to detection was significantly longer than that for the tested Enterobacteriaceae described above. In each case, however, the specimen in the bottle was viable as determined by subculture of an aliquot on blood agar plates.

TABLE 2.

Time to detection of gram-negative bacterial strains after preincubation of aerobic bottles

| Microorganism | Time to detection with a preincubation time of:

|

|||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 h

|

4 h

|

8 h

|

16 h

|

24 h

|

||||||

| Meana | SD | Bottle:

|

Bottle:

|

Bottle:

|

Bottle:

|

|||||

| 1 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 2 | |||

| P. aeruginosa | 7.6 h | 0.4 h | >7 days | >7 days | >7 days | >7 days | >7 days | >7 days | >7 days | >7 days |

| A. baumannii | 8.9 h | 0.8 h | >7 days | >7 days | >7 days | >7 days | >7 days | >7 days | >7 days | >7 days |

| S. maltophilia | 9.1 h | 0.6 h | 7.3 h | 7.8 h | 6.2 h | 6.5 h | >7 days | >7 days | >7 days | >7 days |

| E. coli | 5.3 h | 0.3 h | 1.0 h | 1.0 h | 1.2 h | 1.2 h | 1.2 h | 1.2 h | 1.2 h | 1.7 h |

| K. pneumoniae | 6.2 h | 0.4 h | NDb | ND | 1.2 h | 1.2 h | 1.2 h | 1.2 h | 1.2 h | 1.0 h |

| S. marcescens | 6.2 h | 0.5 h | ND | ND | 1.2 h | 1.2 h | 1.2 h | 1.2 h | 1.0 h | 1.0 h |

For six bottles.

ND, not determined.

Without preincubation, all bottles seeded with one of the bacterial strains to be tested were positive. The time needed for the instrument to detect each of the Enterobacteriaceae was significantly longer than that for the preincubated bottle (Table 2). Bottles seeded with E. coli signaled positive after 5.3 h, and those seeded with K. pneumoniae or with S. marcescens signaled positive after 6.2 h. For all three Enterobacteriaceae the average detection time was 5.9 h. Although organisms in bottles inoculated with the nonfermentative species were detected, the detection time was significantly longer than that for the Enterobacteriaceae. Bottles seeded with P. aeruginosa were positive after 7.6 h, those seeded with A. baumannii were positive after 8.9 h, and those seeded with S. maltophilia were positive after 9.1 h. For all three nonfermentative species the average detection time was 8.5 h.

Effect of different colony numbers on the detection of gram-negative bacterial strains.

To determine whether smaller inocula would influence the detection capacity of the BacT/Alert blood culture system, serial dilutions from each bacterial strain (McFarland 0.5) were performed. With a preincubation time of 8 h at 36°C, the bottles seeded with the Enterobacteriaceae species E. coli and the nonfermentative species S. maltophilia signaled positive at each colony number tested (Table 3). Growth of E. coli was detected in bottles inoculated with 3.0 × 103 CFU/ml (1:100 dilution), 275 CFU/ml (1:1,000 dilution), and less than 10 CFU/ml (1:10,000 dilution) after 1.2, 1.0, and 2.8 h, respectively. Although the same McFarland density was used to generate the dilutions of S. maltophilia, only 10 CFU/ml (1:100 dilution) and less than 10 CFU/ml (1:1,000 and 1:10,000 dilutions) were inoculated as determined by culture on blood agar plates. Therefore, the times to detection, i.e., 19.4 h, 21.3, and 24.1 h, were on average more than 1 order of magnitude longer than those for E. coli. In contrast, organisms in bottles inoculated with 1.4 × 104 CFU/ml (1:100 dilution) and 5.5 × 103 CFU/ml (1:1,000 dilution) of A. baumannii remained undetected by the BacT/Alert system. A 1:10,000 dilution (150 CFU/ml), however, allowed detection on average after 9.2 h. The same dilutions of P. aeruginosa showed bacterial counts of 900 CFU/ml (1:100 dilution), 300 CFU/ml (1:1,000 dilution), and 30 CFU/ml (1:10,000 dilution). An inoculum of 9.0 × 102 CFU of P. aeruginosa per ml could not be detected by the BacT/Alert system; smaller colony numbers resulted on average in detection times of 7.4 and 9.1 h, respectively.

TABLE 3.

Time to detection of different colony numbers of gram-negative bacterial strains after 8 h of preincubation of aerobic bottles

| Microorganism | 1:100 dilution

|

1:1,000 dilution

|

1:10,000 dilution

|

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CFU/ml | Time to detection for bottle:

|

CFU/ml | Time to detection for bottle:

|

CFU/ml | Time to detection for bottle:

|

||||

| 1 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 2 | ||||

| P. aeruginosa | 900 | >7 days | >7 days | 300 | 6.8 h | 8.0 h | 30 | 8.8 h | 9.3 h |

| A. baumannii | 1.4 × 104 | >7 days | >7 days | 5.5 × 103 | >7 days | >7 days | 150 | 9.8 h | 8.5 h |

| S. maltophilia | 10 | 19.2 h | 19.5 h | <10 | 21.3 h | 21.2 h | <10 | 25.3 h | 22.8 h |

| E. coli | 3.0 × 103 | 1.2 h | 1.2 h | 275 | 1.0 h | 1.0 h | 10 | 2.8 h | 2.8 h |

Without preincubation, all bottles seeded with the different bacteria listed in Table 4 signaled positive and the time to detection was in reverse proportion to the number of colonies inoculated. Although the absolute number of colonies differs from one strain to another, the Enterobacteriaceae species E. coli needed a shorter time to detection throughout the experiment (on average 7.8, 9.0, and 10.3 h). Bottles seeded with S. maltophilia needed approximately one-quarter more time until detection compared to the preincubated ones (on average 23.9, 25.8, and 30.0 h). The detection times for A. baumannii were on average 11.4 and 16.5 h, at inocula where the system failed to detect the bacterial strain after preincubation. The smallest colony number tested resulted in a detection time of on average 17.7 h, nearly twice as long as the time with preincubation. Bottles seeded with P. aeruginosa at the highest colony number tested signaled positive after on average 10.6 h; at this inoculum, the BacT/Alert system could not detect any bacterial growth in the case of preincubation. Smaller colony numbers tested resulted in clearly longer detection times (on average 12.7 and 14.3 h) than for the preincubated bottles.

TABLE 4.

Time to detection of different colony numbers of gram-negative bacterial strains without preincubation of aerobic bottles

| Microorganism | 1:100 dilution

|

1:1,000 dilution

|

1:10,000 dilution

|

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CFU/ml | Time to detection (h) for bottle:

|

CFU/ml | Time to detection (h) for bottle:

|

CFU/ml | Time to detection (h) for bottle:

|

||||

| 1 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 2 | ||||

| P. aeruginosa | 900 | 10.5 | 10.7 | 300 | 12.7 | 12.7 | 30 | 14.3 | 14.3 |

| A. baumannii | 1.4 × 104 | 11.8 | 11.0 | 5.5 × 103 | 18.2 | 14.7 | 150 | 18.0 | 17.3 |

| S. maltophilia | 10 | 24.0 | 23.8 | <10 | 26.8 | 24.8 | <10 | 29.3 | 30.7 |

| E. coli | 3.0 × 103 | 7.8 | 7.8 | 275 | 9.0 | 9.0 | 10 | 10.3 | 10.2 |

Effect of different colony numbers of P. aeruginosa in the presence of blood on detection.

To determine whether blood would influence the detection capacity of the BacT/Alert system, serial dilutions of P. aeruginosa (McFarland 0.5) were performed. With a preincubation time of 8 h, bottles inoculated with 340 CFU/ml (1:1,000 dilution) signaled positive after 5.7 days. A dilution of 1:10,000 (20 CFU/ml) resulted in a detection time of 6 h in one bottle; in the other one, the same number of CFU remained undetected by the system. A final dilution of 1:100,000 (5 CFU/ml) was detected after 7.1 h.

Without preincubation organisms in all bottles were detected, although the time to detection increased as the colony number got smaller. The dilutions of 1:1,000 (340 CFU/ml) and 1:100,000 (5 CFU/ml) were detected after 12.1 and 15.9 h, respectively. Organisms in one bottle inoculated with 20 CFU/ml (1:10,000 dilution) were detected after 2.8 days; those in the other one were detected after 13.7 h.

Analysis of growth curves.

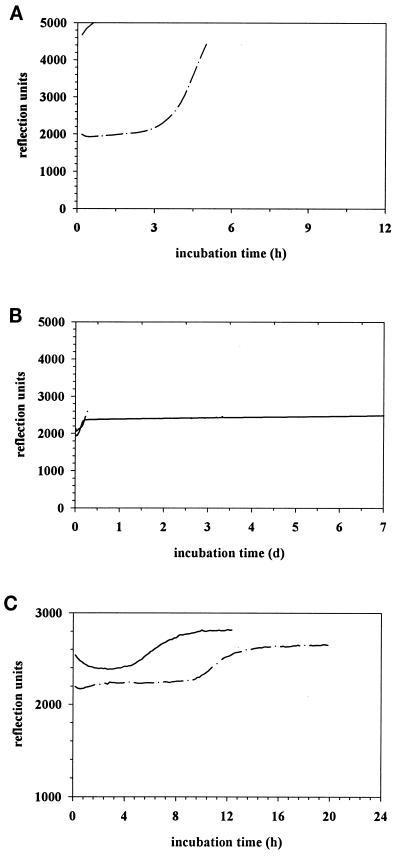

Growth curves for E. coli and P. aeruginosa (McFarland 0.5) with or without preincubation (8 h) were analyzed. Every 10 min the BacT/Alert system measured the absolute CO2 concentration and its acceleration during each time period in the bottle as determined by the color change of the lacmus paper at the bottom of the bottle. The reflection unit represents a combination of both determinations. A threshold exists for both (the absolute CO2 concentration at 3,300 reflection units and the acceleration of the concentration at 32 reflection units/10 min), and above these thresholds the computer system would determine the bottle as positive. Eight hours of preincubation of E. coli resulted in greater than 4,600 reflection units after 1.2 h until determination as positive (Fig. 1A). Without preincubation, 3,500 reflection units were reached after 5.2 h, which was enough for detection of bacterial growth (Fig. 1A). In contrast, 8 h of preincubation of P. aeruginosa resulted in less than 2,400 reflection units over 7 days, which was not enough for determination as positive (Fig. 1B). Without preincubation, 2,600 reflection units after 7.4 h caused the BacT/Alert system to signal positive for bacterial growth in the bottle (Fig. 1B).

FIG. 1.

Effect of delayed-entry time and different colony numbers on the detection of gram-negative bacterial strains. (A) Growth curves of E. coli (McFarland 0.5) preincubated for 8 h (——) or not preincubated (—·—). (B) Growth curves of P. aeruginosa (McFarland 0.5) preincubated for 8 h (——) or not preincubated (—·—) (C) Growth curves of P. aeruginosa (300 CFU/ml) preincubated for 8 h (——) or not preincubated (—·—).

The growth curve of P. aeruginosa, where bottles were inoculated with only 300 CFU/ml (McFarland 0.5 diluted 1:100), reached 2,650 reflection units at 7.4 after loading into the BacT/Alert computer (Fig. 1C). Approximately the same reflection units were measured, but reached after 12.7 h, for detection of the same inoculum without preincubation (Fig. 1C).

DISCUSSION

More than 200,000 cases of septicemia occur annually in the United States (4). The five most common isolates from blood cultures were Staphylococcus aureus, coagulase-negative staphylococci, E. coli, K. pneumoniae, and Enterococcus species (6). Microorganisms that almost always (>90% of isolates) represent true infection when isolated from the blood include S. aureus, E. coli and other Enterobacteriaceae, P. aeruginosa, S. pneumoniae, and Candida albicans (5). In our study 35.2% of all positive blood cultures were gram-negative bacteria and 6.1% belonged to the nonfermentative group, where 40.5% remained undetected by the BacT/Alert system. In each case these bacteria caused symptomatic bacteremia in critically ill patients. Without routine subculture of aliquots from each bottle set from these patients after arrival in the laboratory, none of the nonfermentative species would be detected. Another possibility to reduce false negatives with preincubated blood culture bottles might be to perform preincubation at room temperature instead of 36°C. As shown by others (Organon Teknika, unpublished communication) and by ourselves (unpublished observation), preincubation at room temperature does allow the detection of P. aeruginosa. This procedure offers the advantage that the workload caused by use of subcultivation could be avoided. On the other hand, there is no official recommendation for preincubation at room temperature for the automatic blood culture system, and whether fastidious organisms tolerate this procedure was not analyzed.

Although our facility is an on-site microbiology laboratory, blood culture bottles are not received within a few minutes. Since we have no automatic transportation system, the bottles are transported to the laboratory by service personnel. The service personnel collect the blood culture bottles from different wards and deliver them to the laboratory. The time period between drawing of the blood sample and arrival of the bottles in the laboratory ranges from 30 min to 12 h, and we think that this is not unusual for a hospital consisting of around 1,200 beds. Intensive care units usually place blood culture bottles in incubators until they are collected by service personnel. The situation is worse during the night, when blood culture bottles are incubated overnight within the clinic and are delivered to the laboratory the following day. We are convinced that this is not a unique situation and is encountered in many hospitals throughout the world.

A similar study was done at the Institute of Medical Microbiology and Hygiene, University of Regensburg, Regensburg, Germany. This analysis of the detection capacity of the BacT/Alert system showed that more than 10% of all nonfermentative species remained undetected (N. Lehn, personal communication). This hospital has the advantage of possessing an automated transportation system, and we consider this a reason why nonfermentative species were detected more often than in the study presented here (Lehn, personal communication).

Recently, in a comparative study between the BACTEC 9240 (Becton Dickinson, Heidelberg, Germany) and the BacT/Alert system, Ziegler et al. reported 9 versus 14 false-negative blood cultures, respectively (8). Although the overall false-negative rate for the BacT/Alert was only 0.32% in that study, more than 64% of the false-negative cultures were P. aeruginosa, Acinetobacter spp., and S. maltophilia. The false-negative rate for the BACTEC instrument was 0.20%, and only two Pseudomonas isolates were included (22.2%). Regarding the low false-negative rates, the authors concluded that blind terminal subculture may not be necessary for both systems. Other investigators showed high false-negative rates, up to 6%, and suggested that routine subculturing of negative BACTEC cultures may be necessary (2, 3).

Our study showed that delayed entry of nonfermentative species into the BacT/Alert system influences the detection capacity of the BacT/Alert system. P. aeruginosa and A. baumannii were viable at each preincubation time at 36°C tested but remained undetected. These findings are confirmed by our clinical results, where P. aeruginosa was undetected by the BacT/Alert system in 15 of 32 cases. However, the bacterial count of P. aeruginosa in all of these patients was high enough to cause symptomatic bacteremia; i.e., the patients had an elevated body temperature exceeding 38.5°C. Although without preincubation all Enterobacteriaceae as well as nonfermentative species tested were detected by the blood culture system, interestingly, the detection times without preincubation were approximately fivefold longer for the Enterobacteriaceae. In contrast, the BacT/Alert system was able to detect the nonfermentative species when preincubation was not done, but the time to detection was up to 9 h. These findings support the contention that preincubation of blood culture bottles, in terms of delay in entry into the BacT/Alert system, allows rapid detection of Enterobacteriaceae but impedes the detection of tested nonfermentative species, which of course are clinically relevant bacteria in bloodstream infections.

In the present study, we also demonstrated that smaller inocula allow the detection of nonfermentative species by the BacT/Alert system even when preincubation is done. Only a 1:10,000 dilution of A. baumannii (150 CFU/ml) and 300 CFU of P. aeruginosa per ml resulted in small enough colony numbers for detection. Without preincubation each colony number tested was detected, but the times to detection were significantly longer than those for the preincubated bottles throughout the experiment. Both experiments demonstrated that the preincubation time and the colony number of P. aeruginosa and A. baumannii in the blood culture bottle influence the detection capacity of the BacT/Alert system, although preincubation might influence the system more. However, the number of CFU per milliliter blood culture used was significantly higher than the number of CFU encountered during bacteremia or sepsis. Therefore, we evaluated the possibility that blood might influence the detection capacity of the BacT/Alert system, and we seeded low colony numbers of P. aeruginosa in the presence of 10 ml of blood per bottle. This experiment showed that there might be a threshold at 20 CFU/ml of blood culture, above which the detection of P. aeruginosa is impeded in the case of preincubation. This colony number would be equal to a bacteremia of 100 CFU/ml, which is a reasonable number of bacteria causing bloodstream infections (7). Although the number of bacteria causing bloodstream infections might be lower (down to 30 CFU/ml), the bactericidal properties of the blood and early treatment with antibiotics are two factors that can lower the actual bacterial number found. These results show that routine preincubation of blood cultures may not be the optimal maneuver for nonfermentative species, which are often responsible for symptomatic septicemia in critically ill patients.

Despite its mechanism of action being ill defined, incubation of blood culture bottles at 36°C, in case they cannot be entered into the blood culture system right away, is recommended and frequently used. We interpreted our data to indicate that nonfermentative species, when preincubated in a clinically relevant colony number, were viable but remained undetected by the BacT/Alert system. The possibility that insufficient O2 concentrations in the preincubated blood culture bottles, which were vented at the time of inoculation, were responsible for this phenomenon was not proven. A separate experiment showed that repeating ventilation of the bottles prior to loading did not influence the detection capacity of the BacT/Alert system (data not shown). Analysis of the growth curves showed that bacterial growth occurs to a certain extent, but the detection system of the BacT/Alert computer, which is based on three types of measurements of the CO2 level in the bottle, was not sensitive enough. The threshold of 3,300 reflection units and the acceleration rate of 32 reflection units/10 min were not reached; therefore, no bacterial growth was determined. We posit that nonfermentative species after preincubation of clinically relevant bacterial numbers—especially P. aeruginosa and A. baumannii—may grow only weakly and reach a steady-state concentration where CO2 acceleration occurs at a relatively low basis. Alternatively, nonfermentative species might enter stationary-phase growth after the phase of logarithmic expansion during preincubation and therefore can not be detected in the laboratory. Although it is not ruled out, we consider this unlikely, at least for the clinical specimens, since much higher inocula of P. aeruginosa can be detected by the automatic blood culture system. Even if clinical specimens are preincubated for several hours, they do not match the bacterial numbers corresponding to 1 ml of a McFarland 0.5 solution, but these numbers are detected by the blood culture system. Although the studies presented here did not investigate the exact mechanism, the results provide indirect support for the hypothesis that an unknown factor in the medium of the blood culture bottles is consumed during preincubation and therefore nonfermentative bacteria do not grow. Further examinations of the growth of the nonfermentative species and its interaction with the medium should allow better definition of the mechanism by which nonfermentative species remained undetected by the BacT/Alert system.

In summary, we have shown that the BacT/Alert system failed to detect three nonfermentative species in clinically relevant bacterial counts. These bacteria, in particular P. aeruginosa, are well known to cause septicemia, especially in critically ill patients. Although the exact mechanism of the failure to detect these microorganisms remains to be elucidated, we show that preincubation of blood culture bottles after inoculation with these species plays an important role. These findings emphasize the importance of the rapid transportation of blood cultures to the laboratory, especially in cases where P. aeruginosa is expected. In the laboratory the bottles have to be loaded in the BacT/Alert as soon as possible. Samples collected during the night or from outlying hospitals may be held at room temperature until they are loaded into the BacT/Alert (Organon Teknika, unpublished communication). Bottles which have been preincubated for 4 h or longer should be subcultured prior to loading to avoid false negatives.

REFERENCES

- 1.Pittet D, Li N, Woolson R F, Wenzel R P. Microbiological factors influencing the outcome of nosocomial bloodstream infections: a 6-year validated, population-based model. Clin Infect Dis. 1997;24:1068–1078. doi: 10.1086/513640. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Shigei J T, Shimabukuro J A, Pezzlo M T, de la Maza L M, Peterson E M. Value of terminal subcultures for blood cultures monitored by BACTEC 9240. J Clin Microbiol. 1995;33:1385–1388. doi: 10.1128/jcm.33.5.1385-1388.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Smith J A, Bryce E A, Ngui-Yen J H, Roberts F J. Comparison of BACTEC 9240 and BacT/Alert blood culture systems in an adult hospital. J Clin Microbiol. 1995;33:1905–1908. doi: 10.1128/jcm.33.7.1905-1908.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Washington J A, II, Ilstrup D M. Blood cultures: issues and controversies. Rev Infect Dis. 1986;8:792–802. doi: 10.1093/clinids/8.5.792. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Weinstein M P. Current blood culture methods and systems: clinical concepts, technology, and interpretation of results. Clin Infect Dis. 1996;23:40–46. doi: 10.1093/clinids/23.1.40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Weinstein M P, Towns M L, Quartey S M, Mirrett S, Reimer L G, Parmigiani G, Reller L B. The clinical significance of positive blood cultures in the 1990s: a prospective comprehensive evaluation of the microbiology, epidemiology, and outcome of bacteremia and fungemia in adults. Clin Infect Dis. 1997;24:584–602. doi: 10.1093/clind/24.4.584. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Whimbey E, Wong B, Kiehn T E, Armstrong D. Clinical correlations of serial quantitative blood cultures determined by lysis-centrifugation in patients with persistent septicemia. J Clin Microbiol. 1984;19:766–771. doi: 10.1128/jcm.19.6.766-771.1984. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ziegler R, Johnscher I, Martus P, Lenhardt D, Just H-M. Controlled clinical laboratory comparison of two supplemented aerobic and anaerobic media used in automated blood culture systems to detect bloodstream infections. J Clin Microbiol. 1998;36:657–661. doi: 10.1128/jcm.36.3.657-661.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]