Abstract

Primary neuroendocrine carcinomas of the salivary glands are very rare neoplasms that present light microscopic, ultrastructural, and immunohistochemical features of neuroendocrine differentiation. Twelve cases have been published in the English language literature. We describe the pathologic features of a case of primary large cell neuroendocrine carcinoma of the parotid gland in a 91-year old male and summarize the immunophenotype of previously reported LCNECs of the major salivary glands. It is concluded that primary LCNEC of the salivary glands presents as a high-grade undifferentiated carcinoma, whose diagnosis may be hindered by its rarity and non-specific light microscopic features. A high level of awareness, immunohistochemical staining for neuroendocrine markers synaptophysin and CD56, and a thorough diagnostic work-up in order to exclude metastasis from a primary neuroendocrine carcinoma will allow its diagnosis.

Keywords: Salivary gland diseases, Parotid neoplasms, Carcinoma, Neuroendocrine, Carcinoma, Large cell

Introduction

Neuroendocrine carcinomas of the salivary glands (sgNECs) are rare neoplasms that present light microscopic, ultrastructural, and immunohistochemical features of neuroendocrine differentiation [1, 2]. They are mostly high-grade neoplasms; well- and moderately-differentiated neuroendocrine lesions, so-called carcinoids and atypical carcinoid tumors, respectively, are unusual [3–5]. sgNECs may be primary or metastatic; a primary tumor may develop de novo or, rarely, as a high-grade transformation in a lower grade salivary neoplasm [5, 6]. Metastatic tumors usually originate from the skin, gastrointestinal tract or lungs [5, 7, 8]. Primary sgNECs account for 1–3% of all major salivary gland malignancies [5]. However, as the true number of sgNECs may be both underestimated due to the diagnosis of some cases as undifferentiated carcinomas [2, 9–11], or overestimated as metastatic tumors may be considered as primary [12] their exact prevalence is unknown.

sgNECs are more common in males, with a male to female ratio of 3:1, and mainly present in the 60 to 80 years age group [5]. They involve predominantly the parotid gland and rarely the submandibular gland, while the presence of primary sgNECs of the sublingual gland and the minor salivary glands is questionable [5, 7]. They manifest as large, rapidly growing tumors that may be asymptomatic or associated with neurological signs, such as pain or facial palsy, invade the skin and adjacent soft tissues, and metastasize to the cervical lymph nodes [5, 11, 13].

At the light microscopic level, sgNECs are typical neuroendocrine neoplasms, composed of “blue”, basaloid, round, oval, or spindle shaped cells [1, 5]. They are arranged in an organoid or trabecular growth pattern, and they may form rossetes or show peripheral palisading [1, 5]. The cells may be small, i.e. less than two times the size of a lymphocyte (small cell carcinoma, SmCC) or medium sized to large, i.e. more than three times the size of a lymphocyte (large cell neuroendocrine carcinoma, LCNEC); the ratio of salivary SmCC to LCNEC is 5:1 [1, 2, 5]. SmCC cells have scant eosinophilic cytoplasm with indiscrete borders, and a hyperchromatic, finely granular nucleus with inconspicuous nucleoli. LCNEC cells have polygonal shape, abundant eosinophilic cytoplasm with discrete borders, and a large nucleus with vesicular chromatin that may acquire a speckled or “salt-and-pepper” appearance, and a prominent nucleolus. They may present punctuate coagulative necrosis (comedonecrosis), single cell necrosis, perineural and vascular invasion, and a high mitotic rate, with > 10 mitoses per 2 mm2 or 10 high-power fields [1, 5]. Electron microscopy reveals membrane-bound, electron-dense, neuroendocrine intracellular granules measuring 100–275 nm [1, 7, 9, 14]. Diagnosis is established by positive immunoreaction with at least one of the conventional neuroendocrine markers, i.e. synaptophysin, chromogranin, neuron specific enolase (NSE), or neural cell adhesion molecule CD56 (NCAM) [1, 2].

We describe the pathologic features of a case of primary LCNEC of the parotid gland and summarize the immunophenotype of previously reported LCNECs of the major salivary glands.

Case Report

A 91 year-old male was referred by his doctor for diagnosis and management of a mass in the left preauricular area, following a positive for malignancy FNA. His past medical history was non-relevant, and the patient did not report a head and neck malignancy or previous irradiation in the area.

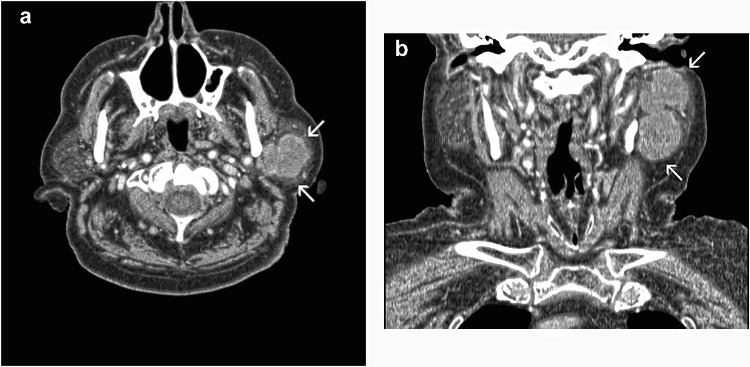

Upon examination, a 9 × 6 cm firm, fixed mass, was observed in the left preauricular area (Fig. 1), while enlarged, non-painful lymph nodes were palpated in the neck. Function of the facial nerve was slightly affected; however, the patient could close his eye and handle liquids while feeding. Imaging of the lesion revealed an extensive mass completely infiltrating the parotid gland and encroaching on the surrounding soft tissues (Fig. 2a and b). The clinical and radiographic work-up, including a chest radiograph, excluded the presence of a tumor elsewhere. The patient was staged as T3N2M0.

Fig. 1.

Mass in the left preauricular area

Fig. 2.

CT imaging. a Axial and b coronal view shows an extensive mass completely infiltrating the parotid gland and encroaching on the surrounding soft tissues (arrows)

Following a discussion with the patient a combined approach was decided with surgical removal of the mass and further complimentary chemo/radiotherapy. The patient underwent a radical parotidectomy, with an ipsilateral modified radical neck dissection. The parotid was resected, along with all the surrounding macroscopically infiltrated soft tissues, reaching to the mastoid bone and the ramous of the maxilla. Grossly, the facial nerve did not appear to be infiltrated. Furthermore, the sternocledomastoid muscle, the spinal accessory nerve and the fibroadipose tissue of lymph node levels II to V were removed.

The patient was referred for chemo/radio therapy, but he succumbed to complications related to this treatment two months following operation.

Two surgical specimens were received. The first consisted of a mass measuring 9 × 6 × 4 cm. The parotid gland was not identified grossly. On sectioning, the cut surface showed a firm tumor with a grayish-white glistening surface. The second specimen measuring 7 × 7 × 3 cm, consisted mostly of fibroadipose tissue with lymph nodes.

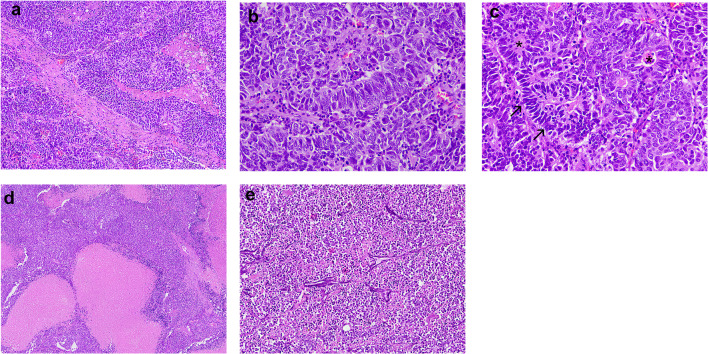

Formalin-fixed and paraffin-embedded (FFPE) tissues sections stained with hematoxylin and eosin showed sheets and lobules of neoplastic cells arranged in an organoid pattern (Fig. 3a) that infiltrated and destructed the parotid gland, as well as the surrounding fibroadipose tissue and the surgical margins. The tumor cells had a moderate amount of eosinophilic, granular cytoplasm, large round to oval nuclei with stippled chromatin and conspicuous nucleoli (Fig. 3b). Peripheral palisading and rosette-like structures (Fig. 3c), as well as numerous mitotic figures were observed, but there was no glandular or epidermoid differentiation. In addition, extensive comedo-like necrosis (Fig. 3d), perineural and perivascular infiltrations, basophilic incrustation of blood vessels’ wall with nuclear material (Azzopardi effect) (Fig. 3e), and nuclear molding and crush artifact were seen. Inflammatory infiltration was scant. Three of the excised lymph nodes were found to be positive for metastases.

Fig. 3.

Microscopic features. a Sheets and lobules of neoplastic cells arranged in an organoid pattern. b The tumor cells have a moderate amount of eosinophilic, granular cytoplasm, large round to oval nuclei with stippled chromatin and conspicuous nucleoli. c Peripheral palisading (arrows) and rosette-like structures (asterisks). d Extensive comedo-like necrosis. (E) Basophilic incrustation of blood vessels’ wall with nuclear material (Azzopardi effect) (hematoxylin and eosin stain, original magnifications A: × 100, B, C: × 400, D: × 200, E: × 100)

Immunostaining was performed with a standard avidin-biotin-peroxidase technique, in the presence of appropriate positive and negative controls. The details of antibodies used are summarized in Table 1. Τhe cells were positive for synaptophysin (Fig. 4a) and CD56 (Fig. 4b), and focally positive for chromogranin-A, EMA/MUC-1 and AE1/AE3 pancytokeratin. They did not react for CK20, TTF-1, S100, CK5/6, and p63. The Ki67 labeling index was > 70%. Some CD3/CD20 positive lymphocytes were present. The final diagnosis was large cell neuroendocrine carcinoma.

Table 1.

Antibodies used in immunohistochemistry

| Antibody | Working dilution | Manufacturer |

|---|---|---|

| Chromogranin-A (monoclonal, clone SP12) | 1:100 | Thermo Fisher Scientific, Fremont, CA, US |

| Synaptophysin (monoclonal, clone SP11) | 1:200 | Thermo Fisher Scientific, Fremont, CA, US |

| CD56 (monoclonal, clone 56C04) | 1:100 | Thermo Fisher Scientific, Fremont, CA, US |

| MUC-1 (monoclonal, clone E29) | 1:400 | Thermo Fisher Scientific, Fremont, CA, US |

| Pancytokeratin (polyclonal, clone AE1/AE3) | 1:100 | Zytomed Systems, GmbH, Berlin, Germany |

| Cytokeratin 20 (monoclonal, clone Ks20.8) | 1:50 | Thermo Fisher Scientific, Fremont, CA, US |

| Thyroid transcription factor (TTF1, monoclonal, clone ICH414) | 1:100 | GenomeMe, Richmond, BC, Canada |

| S-100 protein (monoclonal, clone IHC100) | 1:100 | GenomeMe, Richmond, BC, Canada |

| Cytokeratin 5/6 (monoclonal, clone D5 + 16B4) | 1:50 | Cell Marque, Rocklin, CA, USA |

| P63 (monoclonal, clone IHC063-100) | 1:50 | GenomeMe, Richmond, BC, Canada |

| Ki67 (monoclonal, clone IHC067) | 1:50 | GenomeMe, Richmond, BC, Canada |

| CD3 (monoclonal, clone Sp7) | 1:150 | Thermo Fisher Scientific, Fremont, CA, US |

| CD20 (monoclonal, clone L26) | 1:200 | Thermo Fisher Scientific, Fremont, CA, US |

Fig. 4.

Τhe tumor cells are positive for a synaptophysin and b CD56 (avidin–biotin-peroxidase, original magnification × 100)

Discussion

The light microscopic features, positive immunohistochemical reaction for three conventional neuroendocrine markers, and absence of another NEC support the diagnosis of primary LCNEC of the parotid gland. Poor differentiation and mitotic index > 20% classify this tumor as a NEC according to the staging criteria for pancreatic neuroendocrine tumors that have been applied to head and neck tumors [4, 7]. Mib-1/Ki-67 proliferation index was > 70%, comparable to 30–95% in 4 cases previously tested [7, 10, 15].

Since its initial description in the lungs, LCNEC has been recognized in many other sites [1, 10], however, very rarely in the major salivary glands. Nagao et al. [10] found 2 cases among 1,675 primary parotid tumors accessioned over a 26-year period, and Said-al-Naief et al. [3] reported that they represent < 1% of salivary carcinomas. Mascitti et al. [7] in a review up to 2019 tabulated 8 parotid tumors among 15 cases of salivary gland LCNECs; however, from these reviewed cases, the one described by Petrone et al. [16] is an intermediate-grade NEC or atypical carcinoid tumor [1, 4, 7], while case no. 1 of Chernock et al. [11] was latter re-diagnosed as a metastasis from occult primary MCC [12]. Furthermore, that review did not include a case of LCNEC of the parotid gland reported by Eusebi et al. [17], where the past history of pulmonary NEC and synchronous occurrence of a skin NEC are more suggestive of a metastatic origin. In another case LCNEC was the prevailing carcinoma type in a carcinosarcoma, combined with adenocarcinoma non-otherwise specified (NOS), keratinizing squamous cell carcinoma, spindle cell sarcoma NOS, myxosarcoma and rhabdomyosarcoma [14]. Therefore, the total number of LCNECs of the major salivary glands with adequate clinical, microscopic and immunohistochemical data published in the English language literature is 13 (Table 2). The age of the patients ranges from 21 and 91 years (average age 68 ± 18.3 years), 9/13 patients are in the 6th to 8th decade of life, the male to female ratio is 10:3 and the parotid to submandibular gland ratio is 8:5.

Table 2.

Main clinical and immunohistochemical findings in 12 cases of sgNECs and the present one

| Reference | [18] | [10] | [10] | [13] | [14] | [19] | [11] | [15] | [20] | [21] | [22] | [7] | Present | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | 88 | 72 | 73 | 74 | 72 | 81 | 73 | 69 | 68 | 58 | 45 | 21 | 91 | |

| Gender | F* | M | M | M | M | F | M | F | M | M | M | M | M | |

| Salivary gland | P** | P | P | P | P | S | P | S | S | S | P | S | P | |

| Antibody | Total ( +) | |||||||||||||

| synaptophysin | + | f + *** | − | + | + | + | − | + | + | + | – | + | + | 10/13 |

| chromogranin | − | − | +/− | + | + | − | + | − | − | − | f + | 5/11 | ||

| NSE | + | + | + | + | 4/4 | |||||||||

| CD57/Leu7 | f + | f + | + | 3/3 | ||||||||||

| NCAM (CD56) | f + | f + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | 9/9 | ||||

| PGP9.5 | + | + | 2/2 | |||||||||||

| TTF-1 | − | 5% | − | − | − | 0/5 | ||||||||

| EMA/MUC1 | + | f + | 2/2 | |||||||||||

| wide spectrum keratin | + | − | + | 2/3 | ||||||||||

| AE1/AE3 | + | + | + | + | f + | 5/5 | ||||||||

| CAM5.2 | + | + | + | + | 4/4 | |||||||||

| CK7 | − | − | − | 0/3 | ||||||||||

| CK20 | − | − | + | − | − | − | 1/6 | |||||||

| Bcl-2 | + | + | 2/2 | |||||||||||

| p53 (DO7) | + | + | 2/2 | |||||||||||

| pRB | + | + | 2/2 | |||||||||||

| p16 | + | + | − | 2/2 | ||||||||||

| p21Waf1 | − | f + | 1/2 | |||||||||||

| p27Kip1 | − | f + | 1/2 | |||||||||||

| cyclin D1 | + | + | 2/2 | |||||||||||

| Ki-67 (Mib-1) | 57.1% | 53.4% | 95% | 30–35% | > 70% | |||||||||

| LCA | − | − | − | 0/3 | ||||||||||

| S100 | + | f + | f + | − | − | − | 3/6 | |||||||

| vimentin | f + | f + | − | 2/3 | ||||||||||

| p63 | + | − | − | + | − | 2/5 | ||||||||

| aSMA | − | − | − | 0/3 | ||||||||||

| HMB45 | − | − | − | 0/3 | ||||||||||

| EGFR | + | + | 2/2 |

The following antibodies were tested negative in ≤ 2 cases: MCPyV large T antibody [11], 34bE12 [14], CEA [14], napsin [15], actin [15], desmin [15], calponin [15], CD117 [15], NUT [15], CD99 [15], FLI-1 [15], surfactan apoprotein [21], estrogen receptors [21], androgen receptors [21], CD30 [22], CD138 [22]

*F female, M male

**P parotid gland, S submandibular gland

***f + = focal positivity, counted as positive

The light microscopic examination of a salivary LCNEC shows an undifferentiated high grade carcinoma. Diagnosis is difficult mostly due to the rarity of this entity and the variable positivity for neuroendocrine markers, which are, however, considered as the diagnostic hallmark for the tumor [5]. Table 2 summarizes the results of immunohistochemistry in 12 previously reported salivary gland LCNECs [7, 10, 13–15, 18–22] and the present one. Considering common neuroendocrine markers, positive reaction was seen for synaptophysin in 10 of 13 cases tested [7, 13–15, 18, 20, 21], in one of them focally [10], CD56 in 9 of 9 cases [7, 14, 15, 20–22], in two of them focally [10], NSE in 4 of 4 cases [10, 14, 18], chromogranin in 4 of 11 cases [11, 13, 14], one of them focally, while in another case was equivocal [10], and PGP9.5 in 2 of two cases [10]. In addition, 3 cases showed positivity with CD57/Leu7, mostly focal [10, 14]. Our case was widely positive for synaptophysin and CD56, and focally positive for chromogranin. It was, also, positive for AE1/AE3, in accordance with previous reports that show positivity for pancytokeratin antibodies [7, 10, 14, 18]. However, the cytokeratin profile of the tumor has not been specifically investigated.

Although the major salivary glands are an uncommon site for systemic metastasis [8], the main consideration in the differential diagnosis of a parotid gland NEC is metastasis from a cutaneous Merkel cell carcinoma (MCC) or a pulmonary NEC [2, 3, 5, 8, 13]. In the absence of a relevant clinical history a thorough metastatic work-up is necessary as the primary tumor may have remained unnoticed, while the possibility of spontaneous regression of the primary lesion should, also, be considered [3, 5, 12]. MCC is a high-grade malignancy common in sun-exposed areas of the head and neck of older patients that may metastasize to the intra-parotid lymph nodes [12]. The overlap in light microscopic and immunohistochemical features between metastatic MCC and SmCC may be complete [2, 11, 12]. In particular, CK20 positivity that is found in up to 95% of MCCs [11] has been reported in some SmCC [5, 11, 23] and in 1 of 6 [13] cases of salivary gland LCNECs tested, although the characteristic perinuclear dot-like pattern seen in MCC was not present. Merkel cell polyomavirus (MCPyV) large T-antigen is detected by immunohistochemistry in up to 80% of MCCs [11, 12], while UV signature mutations, indicative of a sun damage-induced phenotype, were found by next-generation whole exome DNA sequencing to be highly prevalent in MCPyV-negative cutaneous MCCs and are not expected in sgNECs [12]. Although MCPyV has been found in some cases of SmCCs tested [11, 23, 24], it has been suggested that the presence of MCPyV or UV signature mutations in a salivary gland high-grade NEC would strongly favor an occult metastatic MCC [12]. In fact, a CK20-positive and MCPyV-negative salivary gland tumor previously reported as LCNEC [11] was reclassified as MCC due to the presence of UV signature mutations [12]. This case highlights the diagnostic difficulties for primary sgNECs, as the detection of UV signature mutations requires advanced molecular techniques that are not routinely utilized and have not been applied in most previously described cases of CK20-positive sgNECs. Pulmonary NECs are usually CK20-negative and CK7-positive [13], and express TTF-1 in 80–100% of cases [4]. Focal (5%) TTF-1 positivity was described in 1 of 4 case of salivary gland LCNECs tested [15], while CK7 was negative in all cases tested [13, 15, 22]. Our case was negative both for CK20 and TTF-1, excluding metastasis from a MCC or a pulmonary LCNEC.

The differential diagnosis should, also, include the newly recognized adamantinoma-like Ewing sarcoma (ALES) [25]. This is an extremely rare tumor, with 23 of 31 molecularly-confirmed cases located in the head and neck area, including 8 cases in the parotid gland and 2 in the submandibular gland [25]. Salivary gland ALESs were found in six male and four female patients, with a mean age of 52 years [25]. ALES and NEC share many light microscopic features, such as cytologic uniformity, rosette formation, peripheral nuclear palisading, extensive necrosis, and high mitotic rate [25]. They, also, have in common staining for synaptophysin and chromogranin, reported in salivary gland ALESs in 8/10 and 3/10 of cases, respectively [25]. Therefore, one salivary gland case each was initially diagnosed as high-grade neuroendocrine carcinoma and Merkel cell carcinoma. Squamous differentiation, demonstrated by keratin pearl formation and concomitant immunohistochemical positivity for high molecular weight cytokeratins, p40, synaptophysin, and CD99 are highly suggestive of ALES [25]. Definitive documentation of ALES depends on the characteristic for Ewing sarcoma immunopositivity for CD99 and NKX2.2, as well as t(11;22) EWSR1-FLI1 translocation revealed by molecular testing [25]. Previously reported cases of salivary gland LCNECs did not express CD99 [15] or high molecular weight cytokeratins [14]. Negative staining for 34βE12, CK5/6 and CD99 are not consistent with a diagnosis of ALES in the present case.

Solid adenoid cystic carcinoma, basal cell adenocarcinoma, and myoepithelial carcinoma are included in the differential diagnosis of basaloid salivary gland tumors [25], and adenoid cystic carcinoma may occasionally express neuroendocrine markers [3, 26]. The present case was p63-negative, excluding a myoepithelial phenotype, while extensive sampling did not reveal areas with diagnostic morphology for the specific adenocarcinoma. It is noticed that in 2 of 4 previously tested cases [15, 20, 22] p63 positivity was reported [7, 15], but another myoepithelial marker, aSMA was negative in all 3 cases evaluated [10, 20].

S100, HMB45 and Mart-1 help to rule-out a melanoma that may mimic a NEC [3]. HMB45 was negative in 3 of 3 cases [10, 22], but in 1 of 6 cases S100 was reported as positive [18]. Lymphoid markers, such as leukocyte common antigen (LCA), CD3, CD5, CD20 and CD79a, among others, help distinguish sgNEC from a malignant lymphoma, in particular when cells are dyscohesive and show a diffuse growth pattern [3]. The case presented herein was negative for S100 and CD3/CD20, excluding those diagnoses, while in previous reports [10, 22] LCA, CD30 and CD138 were also negative. Finally, combined LCNECs that present an epithelial component, ductal or squamous [15], pose an additional diagnostic problem [3]. EMA/MUC1 expression previously reported in the LCNEC component of a carcinosarcoma [14] was focal in our case, although there was no evidence of glandular or ductal differentiation.

Molecular studies of LCNEC are sparse. One study reported in a single case loss of heterozygosity (LOH) for TP53 with point mutations in the gene, and in two cases LOH at IFNA flanking the p16 (CDKN2A) locus [7]. In another case of combined LCNEC and squamous cell carcinoma of the submandibular gland, high resolution array comparative genomic hybridization reported a hypodiploid genome with losses involving chromosomes 3p, 4, 7q, 10, 11, 13, 16q, gains of 3q and 16p, a gain in 9p23-p22.3, including the NFIB, and a breakpoint in 10q26.2, in DOCK1 [15]. Some of those genomic features are, also, seen in pulmonary LCNECs [15]. In the most recent study, next generation sequencing in 4 MCPyV-negative sgNECs, one of them a LCNEC, showed inactivation of retinoblastoma (RB1) tumor suppressor gene with loss of pRB and overexpression of p16; activation of the mTOR pathway through mutations of phosphatase and tensin homolog (PTEN) gene; and TP53 mutations [5]. RB1 inactivation is, also, involved in the pathogenesis of high-grade NECs in various anatomic site [5]. p53 overexpression was confirmed in two cases [10].

The origin of primary sgNECs is obscure [7]. It has been hypothesized that intercalated cells [27] or stem cells [28] of the salivary ducts’ system can undergo neuroendocrine differentiation, but in studies of normal salivary glands only neural elements in the stroma, not parenchymal cells, react for neuroendocrine markers [16, 29].

There is no established staging system for sgNECs and both the systems for pulmonary tumors [3] and pancreatic tumors [3, 7] have been applied. The small number of cases reported up to date and the short follow-up in most of them does not allow accurate evaluation of treatment schemes. Approximately 70% of patients with sgNECs present with advanced disease, and the 5-year survival rate is 5–20%. Surgical excision was performed in most cases, in combination with radiotherapy and, in small number of cases, chemotherapy [7]. Four of 11 LCNECs of the salivary glands with relevant information recurred 1 month to 41 months after excision [7, 10, 14], while five patients, including the present case, succumbed to their disease 1 to 24 months following treatment [10, 14, 19, 20].

In conclusion, primary LCNEC of the salivary glands presents as a high-grade undifferentiated carcinoma, whose diagnosis may be hindered by its rarity and non-specific light microscopic features. A high level of awareness, immunohistochemical staining for neuroendocrine markers synaptophysin and CD56, and a thorough diagnostic work-up in order to exclude metastasis from a primary neuroendocrine carcinoma will allow its diagnosis.

Funding

No funding obtained.

Compliance with Ethical Standards

Conflict of interest

All of authors have indicated they have no potential conflict of interest and no financial relationships relevant to this article to disclose.

Ethical Approval

This study was carried out following the Helsinki Declaration for studies involving human subjects.

Informed Consent

The authors have informed consent from the individual.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Kusafuka K, Ferlito A, Lewis JS, Jr, Woolgar JA, Rinaldo A, Slootweg PJ, et al. Large cell neuroendocrine carcinoma of the head and neck. Oral Oncol. 2012;48(3):211–215. doi: 10.1016/j.oraloncology.2011.09.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Chiosea S, Gnepp D, Perez-Ordonez B, Weinreb I. Poorly differentiated carcinoma. In: EI-Naggar AK, Chan JKC, Grandis JR, Takata T, Slootweg PJ, editors. WHO Classification of Head and Neck Tumours, 4th edition Lyon: WHO; 2017. p. 180–1.

- 3.Said-Al-Naief N, Sciandra K, Gnepp DR. Moderately differentiated neuroendocrine carcinoma (atypical carcinoid) of the parotid gland: report of three cases with contemporary review of salivary neuroendocrine carcinomas. Head Neck Pathol. 2013;7(3):295–303. doi: 10.1007/s12105-013-0431-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Martinez-Saez O, Molina-Cerrillo J, RealBarbera Durban CMGDR, Diez JJ, Alonso-Gordoa T, et al. Primary neuroendocrine tumor of the parotid gland: a case report and a comprehensive review of a rare entity. Case Rep Otolaryngol. 2016;2016:6971491. doi: 10.1155/2016/6971491. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chernock RD, Duncavage EJ. Proceedings of the NASHNP companion meeting, March 18th, 2018, Vancouver, BC, Canada: salivary neuroendocrine carcinoma-an overview of a rare disease with an emphasis on determining tumor origin. Head Neck Pathol. 2018;12(1):13–21. doi: 10.1007/s12105-018-0896-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cimino-Mathews A, Lin BM, Chang SS, Boahene KD, Bishop JA. Small cell carcinoma ex-pleomorphic adenoma of the parotid gland. Head Neck Pathol. 2012;6(4):502–506. doi: 10.1007/s12105-012-0376-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Mascitti M, Luconi E, Togni L, Rubini C. Large cell neuroendocrine carcinoma of the submandibular gland: a case report and literature review. Pathologica. 2019;111(2):70–75. doi: 10.32074/1591-951X-13-19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Salama AR, Jham BC, Papadimitriou JC, Scheper MA. Metastatic neuroendocrine carcinomas to the head and neck: report of 4 cases and review of the literature. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod. 2009;108(2):242–247. doi: 10.1016/j.tripleo.2009.03.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hui KK, Luna MA, Batsakis JG, Ordonez NG, Weber R. Undifferentiated carcinomas of the major salivary glands. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol. 1990;69(1):76–83. doi: 10.1016/0030-4220(90)90271-S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Nagao T, Sugano I, Ishida Y, Tajima Y, Munakata S, Asoh A, et al. Primary large-cell neuroendocrine carcinoma of the parotid gland: immunohistochemical and molecular analysis of two cases. Mod Pathol. 2000;13(5):554–561. doi: 10.1038/modpathol.3880096. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Chernock RD, Duncavage EJ, Gnepp DR, El-Mofty SK, Lewis JS., Jr Absence of Merkel cell polyomavirus in primary parotid high-grade neuroendocrine carcinomas regardless of cytokeratin 20 immunophenotype. Am J Surg Pathol. 2011;35(12):1806–1811. doi: 10.1097/PAS.0b013e318236a9b0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sun L, Cliften PF, Duncavage EJ, Lewis JS, Jr, Chernock RD. UV signature mutations reclassify salivary high-grade neuroendocrine carcinomas as occult metastatic cutaneous merkel cell carcinomas. Am J Surg Pathol. 2019;43(5):682–687. doi: 10.1097/PAS.0000000000001231. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Casas P, Bernaldez R, Patron M, Lopez-Ferrer P, Garcia-Cabezas MA. Large cell neuroendocrine carcinoma of the parotid gland: case report and literature review. Auris Nasus Larynx. 2005;32(1):89–93. doi: 10.1016/j.anl.2004.11.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ueo T, Kaku N, Kashima K, Daa T, Kondo Y, Yoshida K, et al. Carcinosarcoma of the parotid gland: an unusual case with large-cell neuroendocrine carcinoma and rhabdomyosarcoma. APMIS. 2005;113(6):456–464. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0463.2005.apm_231.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Andreasen S, Persson M, Kiss K, Homoe P, Heegaard S, Stenman G. Genomic profiling of a combined large cell neuroendocrine carcinoma of the submandibular gland. Oncol Rep. 2016;35(4):2177–2182. doi: 10.3892/or.2016.4621. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Petrone G, Santoro A, Angrisani B, Novello M, Scarano E, Rindi G, et al. Neuroendocrine tumors of the submandibular gland: literature review and report of a case. Int J Surg Pathol. 2013;21(1):85–88. doi: 10.1177/1066896912446747. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Eusebi V, Pileri S, Usellini L, Grassigli A, Capella C. Primary endocrine carcinoma of the parotid salivary gland associated with a lung carcinoid: a possible new association. J Clin Pathol. 1982;35(6):611–616. doi: 10.1136/jcp.35.6.611. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Larsson LG, Donner LR. Large cell neuroendocrine carcinoma of the parotid gland: fine needle aspiration, and light microscopic and ultrastructural study. Acta Cytol. 1999;43(3):534–536. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Sowerby LJ, Matthews TW, Khalil M, Lau H. Primary large cell neuroendocrine carcinoma of the submandibular gland: unique presentation and surprising treatment response. J Otolaryngol. 2007;36(4):E65–E69. doi: 10.2310/7070.2007.E007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kawaratani H, Tsujimoto T, Yoshikawa M, Kawanami F, Shirai Y, Yoshiji H, et al. Large cell neuroendocrine carcinoma presenting with neck swelling in the submandibular gland: a case report. J Med Case Rep. 2013;7:81. doi: 10.1186/1752-1947-7-81. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Yamamoto N, Minami S, Kidoguchi M, Shindo A, Tokumaru Y, Fujii M. Large cell neuroendocrine carcinoma of the submandibular gland: case report and literature review. Auris Nasus Larynx. 2014;41(1):105–108. doi: 10.1016/j.anl.2013.07.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Faisal M, Haider I, Waqas O, Taqi M, Hussain S, Jamshed A. Large cell neuroendocrine carcinoma of parotid gland: a diagnostic dilemma among high grade carcinomas of parotid gland - case report. J Rare Dis Diagn Ther. 2016;2(3):4. doi: 10.21767/2380-7245.100045. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 23.de Biase D, Ragazzi M, Asioli S, Eusebi V. Extracutaneous merkel cell carcinomas harbor polyomavirus DNA. Hum Pathol. 2012;43(7):980–985. doi: 10.1016/j.humpath.2011.08.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lombardi D, Accorona R, Ungari M, Melocchi L, Bell D, Nicolai P. Primary merkel cell carcinoma of the submandibular gland: when CK20 status complicates the diagnosis. Head Neck Pathol. 2015;9(2):309–314. doi: 10.1007/s12105-014-0573-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Rooper LM, Bishop JA. Soft tissue special issue adamantinoma like ewing sarcoma of the head and neck a practical review of a challenging emerging entity. Head Neck Pathol. 2020;14(1):59–69. doi: 10.1007/s12105-019-01098-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hayashi Y, Deguchi H, Nakahata A, Kurashima C, Hirokawa K. Immunopathological study of neuropeptide expression in human salivary gland neoplasms. Pathobiology. 1990;58(4):212–220. doi: 10.1159/000163587. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Gnepp DR, Corio RL, Brannon RB. Small cell carcinoma of the major salivary glands. Cancer. 1986;58(3):705–714. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(19860801)58:3<705::AID-CNCR2820580318>3.0.CO;2-T. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kraemer BB, Mackay B, Batsakis JG. Small cell carcinomas of the parotid gland. A clinicopathologic study of three cases. Cancer. 1983;52(11):2115–2121. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(19831201)52:11<2115::AID-CNCR2820521124>3.0.CO;2-Z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Tosios KI, Nikolakis M, Prigkos AC, Diamanti S, Sklavounou A. Nerve cell bodies and small ganglia in the connective tissue stroma of human submandibular glands. Neurosci Lett. 2010;475(1):53–55. doi: 10.1016/j.neulet.2010.03.045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]