Abstract

There have been a few case reports and one small series of low grade papillary sinonasal (Schneiderian) carcinomas (LGPSC) which mimic papillomas but have overtly invasive growth and which occasionally metastasize. We describe the morphologic, clinical, immunohistochemical, and molecular features of five patients with LGPSC compared with eight cases each of inverted papilloma (IP) and conventional nonkeratinizing squamous cell carcinoma (SCC) with papillary growth. All LGPSC were nested with predominantly pushing invasion, no stromal reaction, and frequent surface papillary growth. All consisted of one cell type only, with polygonal cells with round nuclei, no (or limited) cytologic atypia, low mitotic activity, and prominent neutrophilic infiltrate. One patient had slightly more infiltrative bone invasion, another lymphovascular, perineural, and skeletal muscle invasion, and a third nodal metastasis after 17 years. By comparison, IPs had bland cytology, neutrophilic microabscesses, mixed immature squamous, goblet cell, and respiratory epithelium, and extremely low mitotic activity. Nonkeratinizing SCCs had basaloid-appearing cells with nuclear pleomorphism, brisk mitotic activity, and apoptosis. All LGPSC were p63 positive. Mitotic activity and Ki67 indices were significantly higher for LGPSCs than IPs and significantly lower than NKSCCs, while p53 immunohistochemistry in LGPSC was identical to nonkeratinizing SCC and higher than for IP. Sequencing showed all five tumors to harbor a MUC6 mutation, one tumor to harbor CDKN2A and PIK3R1 mutations, and one tumor to harbor a NOTCH1 mutation. All LGPSC lacked EGFR and KRAS mutations and lacked copy number variations of any main cancer genes. At a median follow up of 12 months, two LGPSC recurred locally, and one patient died after massive local recurrences and nodal metastases. LGPSC is a distinct, de novo sinonasal carcinoma that can be differentiated from papillomas by morphology and selected immunohistochemistry.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1007/s12105-021-01335-3.

Keywords: Sinonasal, Nonkeratinizing squamous cell carcinoma, p16, Human papillomavirus, Papilloma, Low grade papillary sinonasal carcinoma

Introduction

The World Health Organization (WHO) classification of head and neck tumors groups the nasal cavity, paranasal sinuses, and skull base as anatomical sites with similar disease entities [1]. Carcinomas and papillomas are the most common lesions and numerous diverse carcinoma types occur, making sinonasal surgical pathology challenging. Amongst the carcinomas, squamous cell carcinoma (SCC) is the most common with many subtypes: keratinizing (conventional), non-keratinizing [2], basaloid, lymphoepithelial, papillary, and most of the other major SCC subtypes as well [3]. Papillomas are divided into inverted, oncocytic, and exophytic types [1, 4]. These two groups of lesions usually demonstrate distinct features that allow the practicing pathologist to render a clear diagnosis of benign or malignant from the hematoxylin and eosin-stained slides without need for immunohistochemistry or molecular studies. As expected, papillomas show no cytologic atypia, no frank stromal invasion, and only rare mitoses [5, 6] whereas SCCs, across all of the histologic subtypes, have frank cytologic atypia, significant and sometimes very abundant mitoses, and stromally-invasive growth. Some sinonasal SCCs, particularly nonkeratinizing ones, can grow as papillary lesions or with ribbons of tumor cells with pushing borders which, despite being invasive, can look as if they are not [2].

In 2015, however, we reported a low grade papillary sinonasal carcinoma (LGPSC) that blurred that distinction between benign and malignant [7]. The tumor showed thick, immature epithelium with oncocytoid cells, bland cytologic features, no mucous or ciliated cells, and abundant neutrophils. It lacked a classical invasive pattern and had only rare mitoses initially. As the tumor progressed, it manifested pushing invasion with round tumor nests deep into fibroadipose tissue and bone, eventually metastasizing to lymph nodes. We proposed this entity as a unique low grade sinonasal carcinoma type that can be easily mistaken for a benign papilloma. Here we gathered this case and an additional cohort of similar cases and compared them to typical inverted papillomas (IP) and nonkeratinizing SCCs for their clinical, morphologic and immunohistochemical features. We also performed next generation sequencing on the LGPSC cases to characterize their molecular features, particularly in comparison to published data on sinonasal papillomas and carcinomas.

Materials and Methods

Case Selection

After approval by the Human Research Protection Program of Vanderbilt University Medical Center (VUMC), three cases of sinonasal carcinoma mimicking IP were gathered from routine practice (authors’ experience over 3 years 2016–2018) at VUMC. One patient had been reported previously as a single case report [7], and one additional patient was gathered from Emory University from routine clinical practice. We proposed for these five index tumors the term low grade papillary sinonasal carcinoma (or LGPSC). For comparison, eight cases of IP were randomly selected from a prior reported series of patients at Vanderbilt University Medical Center between 2013 and 2014, and eight cases of nonkeratinizing SCC with papillary growth were also retrieved from the files of Vanderbilt University Medical Center from 2006 to 2016. LGPSC was diagnosed when encountering a homogeneous, papillary and nested tumor with pushing borders, one cell type, little or no cytologic atypia, neutrophilic infiltrate, and invasive growth (either by histology or by clinical examination/imaging). Sinonasal papillomas lack true invasion and/or malignant biologic behavior (recurrence or metastasis) and conventional nonkeratinizing SCC is a mass forming lesion which has no, or limited, maturing squamous differentiation, marked atypia, necrosis, and/or high mitotic activity with or without overtly invasive growth.

Clinical and demographic characteristics were gathered from the electronic medical records and included: age and gender, initial presentation details, smoking and drinking history, prior surgical history, radiological impression, treatment, and clinical follow up. The slides were reviewed by two pathologists (MWSC and JSL) for confirmation of diagnosis, noting the histopathologic features (atypia, architecture, inflammatory infiltrates), and mitotic rates.

Immunohistochemistry and In Situ Hybridization

Immunohistochemistry was performed for p16 on formalin-fixed, paraffin-embedded tissue sections using the E6H4 antibody (prediluted; Ventana Medical Systems, Inc.) on a Leica Bond automated instrument (Leica Biosystems, Inc.) with antigen retrieval consisting of 10 min in the ER1 proprietary antigen retrieval solution. Primary antibody solution was diluted using Leica’s BOND primary antibody diluent. The Bond Polymer Refine detection system was used for visualization. Slides were then dehydrated, cleared and coverslipped. Staining was interpreted by one study pathologist (MSC). Intensity was subjectively quantified as 1 + (weak), 2 + (moderate), and 3 + (strong). Scores were then reported as distribution plus intensity (ex. 3 + 1) but simplified into positive and negative using the CAP recommendation (positive = nuclear and cytoplasmic positivity in > 70% of tumor cells of at least moderate to strong intensity) [8].

Immunohistochemistry for p53, smooth muscle actin, and Ki-67 were also performed on a Leica Bond Max IHC stainer. All steps besides dehydration, clearing and coverslipping were performed on the Bond Max. Slides were deparaffinized. Heat induced antigen retrieval was performed on the Bond Max using their Epitope Retrieval 2 solution for 30 min and 20 min for p53 and Ki-67/smooth muscle actin, respectively. The sections were incubated with Ready-to-Use anti-p53 (Ref# PA0057, Leica Biosystems, Newcastle, United Kingdom) for thirty minutes or with ready to use anti-Ki67 (PA0230, Leica, Buffalo Grove, IL) for 60 min. The Bond Refine Polymer detection system was used for visualization of all slides, which were then dehydrated, cleared and coverslipped. Nuclear staining for p53 and Ki-67 was estimated by visual review by a single pathologist (MSC) for the overall percent of tumor cells positive, regardless of intensity (in increments of 5%). All LGPSC patients had previously had p63 immunohistochemistry performed in routine clinical practice.

In situ hybridization for high risk HPV E6/E7 mRNA was performed using the RNAscope HPV kit (Advanced Cell Diagnostics, Inc., Hayward, CA) according to the manufacturer’s instructions on a Leica Bond automated instrument (Leica Biosystems, Inc.) Probes cover HPV types 16, 18, 26, 31, 33, 35, 39, 45, 51, 52, 53, 56, 58, 59, 66, 68, 73, and 82. Positive staining was identified as brown, punctate dots present in the nucleus and/or cytoplasm. Control probes for the housekeeping gene ubiquitin C (positive control evidence of adequate RNA) were also included on each case. Cases were read by a single study pathologist (JSL) and classified in a binary manner as either positive or negative.

In situ hybridization for low risk HPV E6/E7 mRNA was performed on just the LGPSC cases by Propath Laboratories (Dallas, TX) using the RNAscope® 2.5 HD—BROWN Manual Assay (Advanced Cell Diagnostics, Inc., Hayward, CA) targeting HPV-associated RNA in the nucleus and cytoplasm of the target cells. Tissue samples that previously stained positive for High-Risk HPV, as well as some that were negative, were used as batch control tissues and reacted appropriately. Probes cover HPV type 6, 11, 42, 43, 44. Cases were read by a single study pathologist (JSL) and classified in a binary manner as either positive or negative.

Next Generation Sequencing

Whole exome sequencing was performed on all five of the LGPSC cases. First, unstained slides were cut at 5 microns, all material scraped from the slides, and DNA harvested using the truXTRAC FFPE total NA kit—Magnetic Bead (Covaris, Inc.; Woburn, MA, USA). A Quality Control analysis was performed on the whole genomic DNA samples utilizing the Agilent TapeStation for integrity evaluation and a BR DNA Qubit assay for quantitation performed utilizing the Twist Exome library prep and capture kit (RefSeq capture probes). Sequencing was performed at Paired-End 150 bp on the Illumina NovaSeq 6000, targeting an average of 100 M reads/sample (~ 500 × coverage). RTA (version 2.4.11; Illumina) was used for base calling and analysis was completed using the Dragen Enrichment pipeline and generate a VCF file for each sample. QC reports for the sequencing quality and the per sample yield were provided. Only a variant with the ‘PASS’ tag from the VCF file was remained for the downstream analysis. To minimize the germline artifacts, we applied a stringent germline filtering strategy, as followed by the Genomics Evidence Neoplasia Information Exchange (GENIE) project. We removed mutations with the frequency > 0.01% in the European populations from the 1000 Genomes project, the Exome Sequencing Project (ESP) database, and both whole exome (release 2.1.1) and whole genome data (release 3.1) from the Genome Aggregation Database (gnomAD). The mutation data were annotated with the ANNOVAR tool [9]. Non-silent mutations including missense, frameshift/non-frameshift, splicing, and nonsense mutations were characterized, following our previous work [10]. Non-silent mutations in well-known cancer-driver gene including CDKN2A, FAT1, TP53, CASP8, AJUBA, PIK3CA, NOTCH1, KMT2D, NSD1, HLA-A, TGFBR2, HRAS, FBXW7, RB1, PIK3R1, TRAF3, NFE2L2, CUL3, and PTEN were investigated. Tumor mutational burden per sample was calculated by the sum of non-silent mutations that passed the sequencing depth > 300 × in order to meet the target average sequence depth in a sample (500 ×). Gene fusion events by mapped whole exome sequencing reads to the regions of chromosome 6: 18223860-18264530 (DEK gene) and chromosome X: 148546878-148547397 (AFF2 gene) were investigated as well.

Results

We were able to gather five patients with LGPSC from our clinical practices across three institutions. Basic demographics for all the patients are provided in Table 1. The patients had an average age of 68 years (range 48–72). Patients frequently had ominous initial clinical presentation with three of the five (60%) demonstrating neurological symptoms (sensory or auditory neuropathies) or significant facial swelling, signs of invasive growth. The other two patients had just mild symptoms of nasal obstruction and drainage. By contrast, IP patients were younger, with an average age of 52 years (range 33–75). Patients with IP usually presented just with nasal congestion, obstruction, or non-specific chronic sinusitis. The nonkeratinizing SCC patients presented at an average age of 61 years (range 51–88) and frequently had more concerning symptoms at presentation including epistaxis in one patient and vision complaints in another. Smoking and/or drinking rates were higher for nonkeratinizing SCC patients but not clearly different between IP and LGPSC patients.

Table 1.

Clinical features of the patient cohort

| LGPSC | IP | NKSCC | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (range; average) | 68.0 (47–82) | 52.1 (33–75) | 61.1 (51–88) |

| Sex (M:F) | 2:3 | 4:4 | 6:2 |

| Smoking (Y/N) | 1/5 (20) | 2/8 (25) | 5/8 (63) |

| Drinking (Y/N) | 1/5 (20) | 2/8 (25) | 5/8 (63) |

| Tumor location | |||

| Nasal cavity | 3/5 (60) | 5/8 (63) | 8/8 (100%) |

| Paranasal sinuses | 1/5 (20) | 3/8 (38) | 0 |

| Ear | 1/5 (20) | 0 | 0 |

| Nasal vs non-nasal | 3/5 (60) | 5/8 (63) | 8/8 (100) |

For the LGPSC patients who had cross sectional CT scans at presentation (Table 2), three had bone involvement, two with destructive features and one described as “thinning and mild dehiscence” of adjacent bone. A fourth patient (#5) had tumor, on surgical exploration, invading through the nasal bone. This was compared to bone involvement in 3 of 8 NKSCC patients and only 1 of 8 IP patients. All patients with IP and nonkeratinizing SCC had correct initial pathologic diagnoses while three of the five LGPSC patients had an initial benign or ambiguous pathologic diagnosis (one diagnosed as an “inverted papilloma”, one as “fungiform Schneiderian papilloma” [7], and one as “carcinoma” initially but then amended based on clinical characteristics to “atypical squamous proliferation with papillary features”). The other two were diagnosed as low-grade nonkeratinizing SCC and SCC in situ arising in an inverted papilloma, respectively. The three cases diagnosed as benign initially did not show classical histologic signs of invasion in the initial resection specimens whereas the latter two did (Figs. 1 and 2).

Table 2.

Radiographic features of each patient at presentation

| Case | Origin/Location | Bone involvement? (Y/N) | Pattern of bone involvement |

|---|---|---|---|

| NK-1 | Right nasal wall, lateral | No | N/A |

| NK-2 | Right nasal cavity, crossing septum | No | N/A |

| NK-3 | Right maxillary sinus | Yes | Osteitis and periosteal reaction |

| NK-4 | Right nasal mass, anterior | No | N/A |

| NK-5 | Left nasal cavity and maxillary sinus | No | N/A |

| NK-6 | Left nasal cavity and ethmoid air cells | Yes | Invasion into left orbit and dehiscence of fovea ethmoidalis (possible intracranial invasion) |

| NK-7 | Right inferior nasal cavity, medial | No | N/A |

| NK-8 | Left nasal passage | Yes | Remodeling |

| IP-1 | Left sinus mass and ethmoid air cells | Yes | Erosion |

| IP-2 | Right nasal cavity and maxillary sinus | No | N/A |

| IP-3 | Bilateral maxillary sinuses | No | N/A |

| IP-4 | Right maxillary sinus, inferior | No | N/A |

| IP-5 | Left nasal cavity and ethmoid air cells | No | N/A |

| IP-6 | Bilateral maxillary sinuses, sphenoid sinuses and right maxillary sinus | No | N/A |

| IP-7 | Bilateral maxillary sinuses, left nasal lateral wall and left sphenoid sinus | No | N/A |

| IP-8 | Left nasal cavity, posterior | No | N/A |

| LGPSC-1 | Not available | N/A | N/A |

| LGPSC-2 | Right nasal cavity, antero-superior | Yes | Thin and mildly dehiscent bone |

| LGPSC-3 | Right maxillary sinus, anterior wall | Yes |

Into floor of right orbit, expansion of right infraorbital canal Floor of orbit demineralized and eroded |

| LGPSC-4 | Left mastoid air cells, middle ear cavity | Yes | Destruction of inner table of skull |

| LGPSC-5 | Left nasal cavity, anterior | Yes | Invasion through the nasal bone |

N/A not applicable

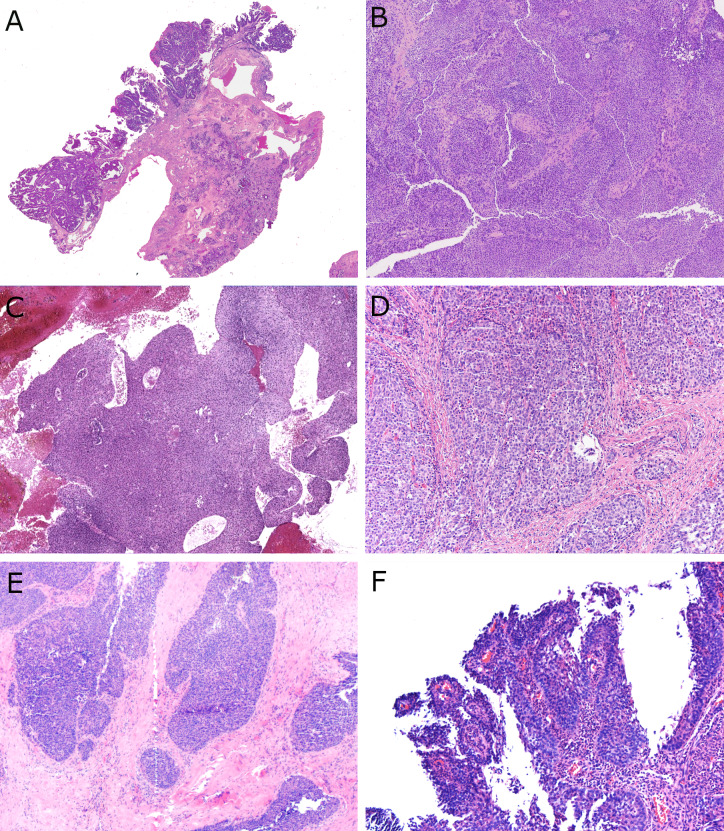

Fig. 1.

Low power histologic features of LGPSC with a mixture of papillary, surface ribbony, and solid nested tumor. A LGPSC #1 at first presentation showing papillary, exophytic growth pattern of stratified epithelium (× 2 magnification) B LGPSC #1 at recurrence with nearly solid central growth with rounded nests pushing together (× 10 magnification) C LGPSC #3 with large, inter-anastomosing solid ribbons of surface tumor with smooth edges (× 2 magnification) D LGPSC #2 with solid, rounded nests of cells in a fibrous stroma (× 10 magnification) E LGPSC #4 with solid, rounded nests of cells in a fibrous stroma with occasional open spaces (× 4 magnification) F LGPSC #5 with surface involvement with papillary, exophytic fronds of discohesive tumor cells (× 10 magnification)

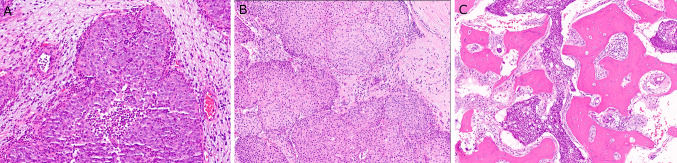

Fig. 2.

Medium power histologic features of LGPSC. A LGPSC #5 showing ribbons and rounded nests of bland cells with brisk neutrophil-rich inflammation and lacking stromal desmoplastic reaction (× 10 magnification) B LGPSC #3 with large, rounded nests of bland cells lacking stromal desmoplastic reaction despite the invasive growth. (× 10 magnification) C LGPSC #2 showing extensive bone invasion (× 8 magnification)

Histologically, LGPSC had variable architecture with slightly different features superficially than in the deeper aspects. The superficial portions of tumor consisted of papillae, ribbons, and variably-sized, rounded or angular nests. While some of the downward pushing nests appeared similar to inverted papilloma, most had more angular shapes and irregularity rather than being consistently rounded (Fig. 1E). They also were predominantly solid (Fig. 1D and 1E). Some tumors had more coalescing solid areas (Fig. 1B). Four of the five patients showed papillary surface growth with fibrovascular cores mimicking a papilloma, at least focally (Fig. 1A, C, and F). All tumors involving the surface epithelium showed true stratification with multiple cell layers (Fig. 1A, B, and F). The nests and ribbons had smooth, relatively pushing borders (Fig. 2A and B) without stromal desmoplasia although an overtly invasive growth pattern was present in three of the five patients consisting of angular nests infiltrating fibrous stroma (Fig. 1E), around blood vessels, into seromucinous glands, muscle, and sometimes bone (Fig. 2B). Tumor #3 showed both lymphovascular invasion and perineural invasion. None of the LGPSC, for which all H&E slides were reviewed and on multiple specimens when recurring, showed a pre-existing component of benign sinonasal papilloma.

Cytologically, all tumors consisted of a single population of polygonal cells that tended to vary from case to case from more squamoid to oncocytoid. Specifically, tumors #2, 3, 4, and 5 were more squamoid appearing with dense cytoplasm, round to ovoid nuclei, variably degrees of cytoplasmic clearing, and open chromatin, sometimes with small visible nucleoli (Fig. 3). Cells were more cohesive. Alternatively, tumor #1 was more oncocytoid (almost plasmacytoid), with cells with eosinophilic cytoplasm and both tumors #1 and #5 had somewhat poor cohesion on the surface with cells falling apart from each other (Fig. 3). Nuclei were round or slightly oval with small, but inconspicuous, nucleoli present in all cases. The four tumors that had a surface papillary component also showed abundant acute inflammation (Fig. 1E), either in the epithelium or in the superficial submucosa. However, unlike typical IP, there were no neutrophilic microabscesses. None of the tumors had mucous cells or ciliated cells, and none of the tumors had the very loose, edematous, inflammatory-polyp-like stroma that is typically seen around IPs. At presentation, the tumor cells lacked significant atypia. Mitotic rates averaged 9.2 per 10 high power fields, compared to 1.1 for IPs and 76.4 for NKSCC. None of the LGPSC had necrosis.

Fig. 3.

High power features of LGPSC demonstrating the cytomorphology. A LGPSC #1 with surface involvement with discohesive, polygonal cells with eosinophilic cytoplasm, monomorphic, round to irregular nuclei, and prominent neutrophil infiltrate (× 40 magnification) B LGPSC #3 with solid nests of polygonal cells with moderate to abundant, eosinophilic cytoplasm, well-defined cell borders, and monomorphic, round to irregular nuclei (× 40 magnification) C LGPSC #5 with surface papillary growth, discohesive, polygonal cells with round nuclei, small but prominent nucleoli, and a brisk neutrophil infiltrate (× 20 magnification)

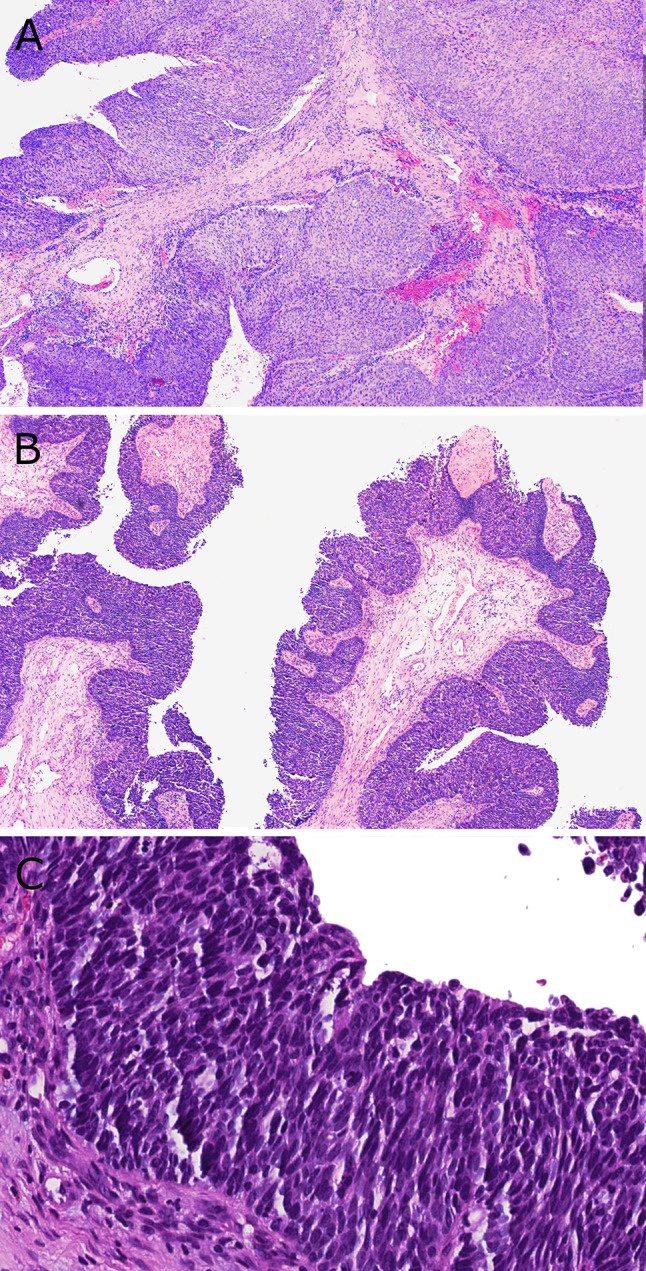

The IPs all showed typical papilloma histology with papillary architecture, inverted growth, and lack of destructive or irregular, infiltrative growth. They had bland cytology and a mixture of immature squamous, ciliated, mucous, and focally, more maturing squamous, cells (Fig. 4). All cases of NKSCC were basaloid tumors with cells with high nuclear to cytoplasmic ratios, moderate to severe cytologic atypia, and a range of architectural patterns including papillary, ribbony, large nested, and classically infiltrative. Where they involved the surface with papillary growth, cells were obviously malignant with hyperchromasia, angulation, pleomorphism and mitoses. Necrosis was present in 4 of the 8 cases (50%) (Fig. 5).

Fig. 4.

Histologic features of inverted papilloma. A Low power view showing large, rounded nests of cells, some solid and some with luminal spaces, pushing into the loose underlying submucosa (× 4 magnification). B Thickened lining epithelium with immature squamoid cells with round, bland nuclei and mixed surface ciliated respiratory cells (× 20 magnification)

Fig. 5.

Histologic features of conventional nonkeratinizing SCC. A Low power view showing large, solid, ribbony and pushing nests of basaloid tumor cells (× 2 magnification). B An extensively papillary nonkeratinizing SCC showing papillae lined by basaloid tumor cells (× 4 magnification). C High power view of nonkeratinizing SCC consisting of full thickness surface involvement by basaloid tumor cells with minimal cytoplasm, angulated hyperchromatic nuclei, and prominent mitotic activity and apoptosis (× 20 magnification)

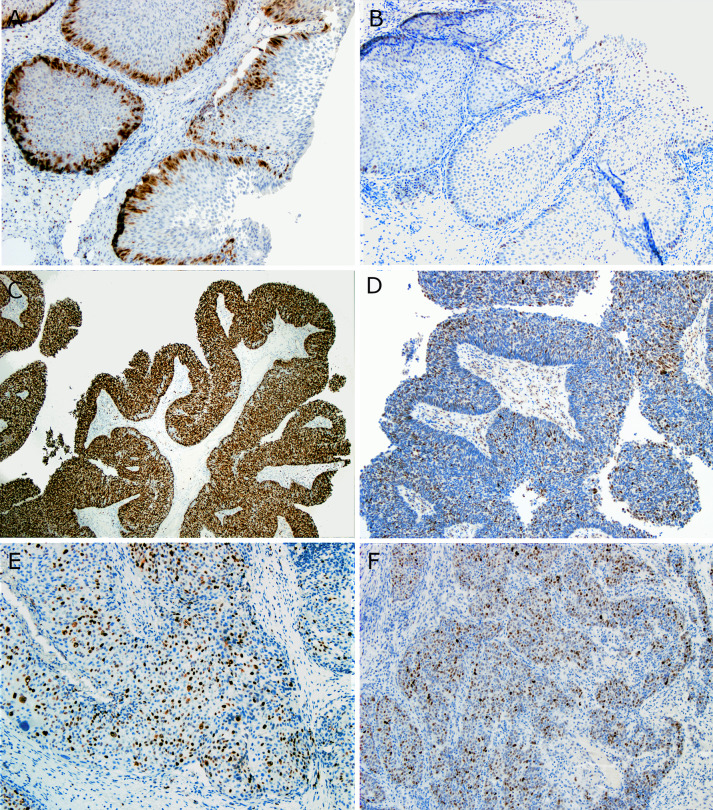

Immunohistochemically, all LGPSC were strongly and diffusely positive for p63 and negative for p16 (all with patchy staining but none more than 70% nuclear and cytoplasmic staining), as were all IPs. Six of the eight (75%) nonkeratinizing SCC were p16 positive. RNA in situ hybridization for high and low risk HPV was negative in all five LGPSC cases (the IPs and nonkeratinizing SCCs were not tested for this study). Ki-67 proliferation rates were modest in LGPSC (average 27%, range 5–50), and p53 expression was relatively high (average 43%, range 15–70). However, none of the LGPSC had strong, diffuse (> 95%) expression or complete absence which might indicate a true TP53 mutation [11, 12]. This compares to 63.5% (range 30–98) and 39% (range 1–98) in the nonkeratinizing SCCs, and 13.7% (range 10–15) and 9% (range 1–20) in IPs, respectively (Table 3 and Fig. 6). Based on these findings, LGPSC seems to lie on a spectrum for proliferation rates between IP and nonkeratinizing SCC, and, despite lacking expression patterns such as diffuse, strong positivity or complete absence that would indicate p53 mutation [11, 12], has nuclear p53 expression rates similar to nonkeratinizing SCC.

Table 3.

Proliferative activity and p53 and p16 immunohistochemical results

| Mitotic count/10 HPF average (range) | Ki-67 % (range) |

p53 % (range) |

p16 | p63 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| IP | 1.1 (0–4) | 13.7% (10–15) | 9.0% (1–20) | 0/8 (0) | NA |

| LGPSC | 9.2 (3–25) | 27.0% (5–50) | 43.0% (15–70) | 0/5 (0) | 5/5 (100) |

| NKSCC | 76.4 (43–122) | 63.5% (30–98) | 39.0% (1–98) | 6/8 (75) | NA |

IP inverted papilloma, LGPSC low grade papillary sinonasal carcinoma, NKSCC nonkeratinizing squamous cell carcinoma, HPF high power fields, NA not applicable

Fig. 6.

Immunohistochemical stains for Ki-67 and p53. A Inverted papilloma showing low (15%) Ki-67 expression with a distinctly zonal (basal) distribution of staining (× 10 magnification) B Inverted papilloma showing low (10%) p53 expression (× 10 magnification). C Nonkeratinizing SCC showing diffuse Ki-67 expression (98%) (× 4 magnification). D Nonkeratinizing SCC showing prominent nuclear p53 expression (50%) (× 10 magnification). E LGPSC showing modest Ki-67 expression with no apparent zonal pattern even in areas of surface epithelial involvement (× 10 magnification). F LGPSC showing prominent (60%) nuclear p53 expression (× 10 magnification)

All LGPSC patients underwent primary surgical resection with adjuvant radiotherapy and chemotherapy given to two patients (LGPSC 2 and 3). Follow up was available for all patients with a median of 14 months. Our index patient’s tumor (LGPSC1) recurred ten times over 18 years, and the patient eventually died of disease. Another patient (LGPSC5) had a recurrence 10 months after resection and has since been managed with simple observation. At last follow up, she showed clinically stable intranasal papillomatous lesions (15 months post-surgery) suspicious for persistent local disease. The other three patients had no evidence of disease at last follow up intervals of 8, 12, and 23 months. Nonkeratinizing SCC treatment consisted of primary surgical resection in all 8 patients and adjuvant radiation in five. All but 1 of the 8 patients was disease free at last follow up, with that 1 patient having 2 recurrences over 3 years, managed with reoperation. All IP patients underwent primary surgical resection with no adjuvant treatment, none recurred, and all were without evidence of disease at last follow up.

Given a total sequenced region of 30 Mb, whole exome data showed mean and median tumor mutational burden for the 5 cases of 6.28 and 6.67 per Mb, respectively (Table 4). Based on the classifications proposed for tumor mutational burden, LGPSC #1 would be “low” and the rest more typical for carcinoma, with none of them being tumor mutational burden “ultralow” (i.e. < 1/Mb) [13, 14]. Six mutations were found in 3 of the LGPSC, one in the MUC6 (chr.11) gene was present in all 5 cases, one non-silent mutation in the cancer driver gene CDKN2A was present in one case (with sequencing depth ~ 800 ×), 3 in the cancer driver gene PIK3R1, all in one case (with sequencing depth ~ 300 ×), and one in the cancer driver gene NOTCH1 from one case (with sequencing depth ~ 100 ×). Detailed sequencing results are provided in Supplemental Tables R1 and R2. Notably, no mutations were detected in TP53, PIK3CA, KRAS, NRAS, or EGFR. In addition, no copy number variations were detected in the known cancer driver genes using the tool xHMM [15] (data not shown). Although whole exome sequencing is not the optimal method for gene fusion detection, mapped sequence investigation failed to detect any DEK-AFF2 sequences [16, 17].

Table 4.

Tumor mutational burden for each LGPSC case

| Sample | Non-silent mutations per exome (> 300 ×) | Tumor mutational burden |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | 53 | 1.77 |

| 2 | 193 | 6.43 |

| 3 | 200 | 6.67 |

| 4 | 289 | 9.63 |

| 5 | 207 | 6.90 |

| Average | 188.4 | 6.28 |

LGPSC low grade papillary sinonasal carcinoma

Discussion

Since our first description of a LGPSC, which we previously had termed “low grade papillary Schneiderian carcinoma”, four other case reports have been published [18–21]. In summary, all four additional cases showed destructive and/or multifocal sinonasal tumors, one with ear/temporal bone involvement, that consisted of bland, often papillary and pushing growth in the superficial aspects but invasive growth in the deeper aspects at presentation or upon recurrence. The surface involvement was multilayered with cells with lightly eosinophilic cytoplasm, round to oval nuclei with inconspicuous nucleoli. There has consistently been only one cell type, without mucus cells or cilia, and, at least initially, low mitotic activity, occasional necrosis, and often a neutrophilic infiltrate. None of the tumors has shown any obvious histologic differentiation, either squamous, glandular, or otherwise. In all reported cases, p16 was partial but always less than 70%, and, where assessed, no HPV detected. Carnevale et al. [19] performed direct Sanger sequencing of KRAS and EGFR genes and found no mutations to be present. A series of five patients was recently published also under the name “low grade papillary Schneiderian carcinoma” where they describe all having surface exophytic growth and “pushing”, inverted invasion with bland cytology [22]. They describe some palisading, some cell spindling, and rare mucus cells. Four had involvement beyond the sinonasal tract with spread to nasopharynx, skull base, middle ear, and temporal bone. Two of their patients developed nodal metastases, one distant metastases, and one died of progressive disease at 7 months. All cases were diffusely positive for p40. All cases lacked EGFR and KRAS mutations, but no additional molecular testing was performed.

These reported cases are consistent with the findings from our cohort of five LGPSC cases and would bring the total number of reported cases to 14. The authors of the reported cases reiterate the remarkably bland looking cytopathology of LGPSC and highlight the danger of misdiagnosing them as simple sinonasal papillomas. From the five case reports, all were initially diagnosed as benign with diagnoses of fungiform (exophytic) papilloma in Lewis Jr. et al., oncocytic papilloma in the case by Jeong HJ et al. [20], and IP in the patients from Brown et al. [18] and Williamson et al. [21]. The tumors were also diagnosed as IP in two of our four newly reported patients. That becomes even more of a pitfall when the diagnosis has to be rendered on a small biopsy that might show only the focal papillary architecture and bland cells without sampling the deeper tissues to show areas of overt invasion. Even if the biopsy was deep enough to be truly representative of the entire lesion, invasion might not manifest itself in the classical form, instead demonstrating pushing borders with nests as seen, at least partially, in all reported cases in the literature and in three of our five patients. This can be confused with the inverted nests seen in IP, but LGPSC nests tend to be more angulated and irregular with less consistently rounded contours seen in papillomas. Furthermore, the case reports reinforce our finding that the clinical presentation is frequently more ominous than for papillomas. We believe this to be an important clue to the diagnosis. The patient from Brown et al. [18] presented one year after her diagnosis of an “IP” with near complete left facial paralysis, the patient from Williamson et al. [21] presented with facial pain, and in our cohort, three of the five patients presented with sensory or auditory neuropathies or significant facial swelling [7]. Of the patients in the series by Zhai et al., two of the five had loss of smell, one tinnitus, and four epistaxis [22].

When faced with a papillary or inverted appearing tumor with bland cytology on biopsy of a sinonasal tumor with an aggressive presentation, there are many clues to the diagnosis and potential differentiating features from the mimicking lesions IP and typical nonkeratinizing SCC. These are listed in Table 5. It is worth carefully examining the histopathology on higher power as LGPSC show differences from a regular IP or oncocytic papilloma. Although the epithelium consists of stratified tumor cells that are 6–7 cells thick, the cells are uniformly round to polygonal without mucous cells or surface ciliated, respiratory epithelial cells. Intraepithelial neutrophils are typically present but usually not as prominent as in IPs, are more often present in the stroma rather than the epithelium, and do not often generate microabscesses. LGPSC, in its deeper aspects, may manifest more overt cytologic atypia which is never seen in papillomas. This supports it as frank carcinoma and also differs from dysplasia and carcinoma in situ in papillomas, where this is almost always associated with overt squamous differentiation. While LGPSC often grow like a benign sinonasal papilloma, they are distinguished morphologically from carcinoma ex sinonasal papilloma by the complete lack of benign papilloma foci. These would have mixed mucus and ciliated cells and neutrophilic infiltrates showing microabscesses. Mitotic rates and Ki67 and p53 staining patterns provide more objective evidence that LGPSC tumors are different from papillomas. LGPSC show intermediate mitotic rates and Ki-67 staining from those of IP and nonkeratinizing SCC (Table 2). p53 expression for LGPSC averaged 43% compared to only 9% in IPs (Table 2). The Ki-67 pattern is different as well, being consistently basal in IP but more jumbled and irregular in LGPSC.

Table 5.

Features which can differentiate LGPSC, IP, and NKSCC

| Clinical presentation | Morphology | Invasion pattern | Bone, perineural, or lymphovascular invasion | Mucus and/or ciliated cells | Nuclear atypia |

Mitotic rate/10 HPF | Nuclear Ki67% | Nuclear p53 % |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| IP | Congestion, sinusitis, obstruction, slow growing, painless mass |

Papillary and inverted architecture; “Transitional epithelium” with no atypia; Edematous stroma |

No invasion | Consistently absent | Present | Absent | Very low | Low with basal distribution | Low |

| LGPSC | Obstruction, congestion, and ominous features with neurological symptoms such as pain, numbness, or tingling, facial swelling |

Papillary, nested and solid architecture; No to minimal cytologic atypia; Monomorphous low-grade population of cells; |

Pushing border of inverted nests with no or minimal stromal reaction; Deeper areas may have more classical, infiltrative pattern | Common | Absent | Predominantly or completely absent to mild with patchy atypia in deeper aspects | Low | Moderate with less basal and more “jumbled” distribution | Moderate to high |

| NKSCC | Obstruction, congestion, sinus fullness, epistaxis, painless mass |

Papillary, nested or solid architecture; Moderate to severe cytologic atypia; Necrosis may be present |

Broad pushing border OR classical, infiltrative pattern | Common | Ciliated cells absent; mucus cells rare | Marked | High | High with no apparent pattern | Moderate to high |

IP inverted papilloma, LGPSC low grade papillary sinonasal carcinoma, NKSCC nonkeratinizing squamous cell carcinoma, HPF high power field

Our whole exome sequencing results, although admittedly suboptimal given the lack of sequencing of matched normal tissues and lack of assays for structural rearrangements such as translocations, are nonetheless helpful to support these tumors as malignant and as de novo. The tumor mutational burden of LGPSC was 6.28 per Mb which falls in line with carcinomas in general, with none of the cases being “ultralow” as would be expected for a benign lesion [13, 14]. Brown et al. showed that by next generation sequencing of 11 inverted or oncocytic papillomas with associated carcinomas, tumor mutational burden in the benign papilloma components was ultralow (< 1/Mb), none had copy number alterations, all had EGFR or KRAS mutations, and only one harbored a single additional mutation (a PIK3R1 frameshift mutation) [4]. These molecular results strongly support our five unusual tumors to be carcinomas and not just atypical papillomas. A mutation in MUC6 was found in all five cases. MUC6 is a gene on chromosome 11 that codes for a glycoprotein that contributes to the normal functioning of the gastrointestinal tract, being most heavily expressed in gastric glands. MUC6 is thought to inhibit tumor cell invasion, and its decreased expression plays a potential a role in the invasiveness of gastric and pancreatic carcinomas [23]. MUC6 can also be aberrantly upregulated in carcinomas of organs that do not physiologically express MUC6 like breast tissue, and hence can be a marker of malignancy [24]. In the sinonasal tract, the mucins produced physiologically are the secreted MUC5AC and MUC5B and the membrane tethered MUC1, MUC4 and MUC16 [25]. MUC6, then, is not normally expressed in the sinonasal tract. The impact of the MUC6 mutations we detected on its expression in LGPSC is not clear and, to the authors’ knowledge, no mutation-phenotype data exists in the literature that might explain it. The location of the mutations directly in the coding regions of the gene and not in regulatory elements suggests that they are very unlikely to increase expression. Other than MUC6, it was revealed that two of the LGPSC had mutations in the known cancer driver genes CDKN2A, PIK3R1, and/or NOTCH1. These mutations can be seen in up to 20–25% of head and neck SCC [4, 26–28]. Of note, activating EGFR mutations were not found in any LGPSC in our cohort providing further evidence that LGPSC do not represent “invasive” or “metastasizing” IP, nor carcinomas arising from IP as both of these entities have high rates of activating EGFR mutation [4, 29, 30] while oncocytic papillomas and carcinomas arising from them almost all show KRAS mutation. Furthermore, most mutations typical of HPV-negative and HPV-related head and neck SCCs were absent, such as TP53, PIK3CA, TRAF, and E2F1 [26, 28]. Some recent studies have identified an apparently distinct form of skull base, temporal bone, and upper sinonasal tract nonkeratinizing SCC with a DEK-AFF2 translocation. The reported tumors are more basaloid and overtly malignant than LGPSC, with pleomorphism and apoptosis/mitosis [16, 17]. The relationship of LGPSC to these tumors is not clear.

LGPSC can cause significant morbidity and even mortality, as evidenced by at least one case in our cohort (the index case) where the patient died 18 years after diagnosis with 10 recurrences [7] and even nodal metastases. If we include the cases reviewed from the literature, it seems that a total of 9 out of the 14 patients had recurrences, 7 of which experienced multiple recurrences. Several of the patients received post-operative radiation, for example in Jeong et al. [20] and Brown et al. [18] without subsequent recurrences. This suggests that postoperative radiation may be useful for achieving cure.

In conclusion, LGPSC appears to be a distinct, de novo, low grade sinonasal carcinoma of likely squamous differentiation that has, due to its bland cytology and papillary/nested architecture, the potential to be misdiagnosed as a benign papilloma. When faced with a bland sinonasal epithelial neoplasm lacking the typical histopathologic features of exophytic, inverted, or oncocytic papilloma, one should have a strong suspicion for LGPSC. A correct diagnosis can be rendered by recognizing the homogeneous cytomorphology without mucus cells, the frequent discohesion when there is surface involvement, the more prominent mitotic activity overall than papillomas, and potentially by the use of immunostaining for p53 and Ki-67. Larger, multi-institutional studies are needed to better characterize the clinical behavior, molecular features, and morphologic spectrum of these rare tumors.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to acknowledge Samir K. El-Mofty DMD, PhD, for pointing out the original tumor and for his mentoring, humor, and fruitful discussions around its classification and behavior. We would also like to thank Angela L. Jones, MS, Scientific Core Facility Research Manager for the Vanderbilt University Medical Center Technologies for Advanced Genomics (VANTAGE) facility, for her help with the tumor sequencing.

Funding

No external funding was obtained for this study.

Declarations

Conflict of interest

Dr. Chernock is a member of the Precision Oncology Alliance of Caris Life Sciences, Inc., which is an unpaid role where she provides research guidance. She has no other potential conflicts of interest, financial or otherwise, to report, and neither do any of the remaining authors.

Ethical approval

This study was performed with approval of the respective institutional review boards and complies with required ethical standards. Given the retrospective nature of the study, patients were never contacted, and we did not require informed consent.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Contributor Information

Mario W. Saab-Chalhoub, Email: mario.w.saab.chalhoub@vumc.org

Xingyi Guo, Email: Xingyi.guo@vumc.org.

Qiuying Shi, Email: lq0958@gmail.com.

Rebecca D. Chernock, Email: rchernock@wustl.edu

James S. Lewis, Jr., Email: james.lewis@vumc.org

References

- 1.El-Naggar A, Grandis JR, Chan JK, et al., editors. WHO classification of head and neck tumours. 4th ed. Lyon: IARC Press; 2017.

- 2.Bishop JA, Brandwein-Gensler M, Nicolai P, et al. et al. Nonkeratinizing squamous cell carcinoma. In: El-Naggar A, Grandis JR, Chan JK, et al.et al., editors. WHO classification of head and neck tumors. Lyon: IARC Press; 2017. pp. 15–17. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ansa B, Goodman M, Ward K, et al. Paranasal sinus squamous cell carcinoma incidence and survival based on Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results data, 1973 to 2009. Cancer. 2013;119:2602–2610. doi: 10.1002/cncr.28108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Brown NA, Plouffe KR, Yilmaz O, et al. TP53 mutations and CDKN2A mutations/deletions are highly recurrent molecular alterations in the malignant progression of sinonasal papillomas. Mod Pathol. 2020 (online ahead of print). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 5.Kaufman MR, Brandwein MS, Lawson W. Sinonasal papillomas: clinicopathologic review of 40 patients with inverted and oncocytic schneiderian papillomas. Laryngoscope. 2002;112:1372–1377. doi: 10.1097/00005537-200208000-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lawson W, Ho BT, Shaari CM, et al. Inverted papilloma: a report of 112 cases. Laryngoscope. 1995;105:282–288. doi: 10.1288/00005537-199503000-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lewis JS, Jr, Chernock RD, Haynes W, et al. Low-grade papillary schneiderian carcinoma, a unique and deceptively bland malignant neoplasm: report of a case. Am J Surg Pathol. 2015;39:714–721. doi: 10.1097/PAS.0000000000000390. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lewis JS, Jr, Beadle B, Bishop JA, et al. Human papillomavirus testing in head and neck carcinomas: guideline from the College of American Pathologists. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2018;142:559–597. doi: 10.5858/arpa.2017-0286-CP. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wang K, Li M, Hakonarson H. ANNOVAR: functional annotation of genetic variants from high-throughput sequencing data. Nucleic Acids Res. 2010;38:e164. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkq603. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Chen Z, Wen W, Beeghly-Fadiel A, et al. Identifying putative susceptibility genes and evaluating their associations with somatic mutations in human cancers. Am J Hum Genet. 2019;105:477–492. doi: 10.1016/j.ajhg.2019.07.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.McCluggage WG, Soslow RA, Gilks CB. Patterns of p53 immunoreactivity in endometrial carcinomas: 'all or nothing' staining is of importance. Histopathology. 2011;59:786–788. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2559.2011.03907.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Yemelyanova A, Vang R, Kshirsagar M, et al. Immunohistochemical staining patterns of p53 can serve as a surrogate marker for TP53 mutations in ovarian carcinoma: an immunohistochemical and nucleotide sequencing analysis. Mod Pathol. 2011;24:1248–1253. doi: 10.1038/modpathol.2011.85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.McNamara MG, Jacobs T, Lamarca A, et al. Impact of high tumor mutational burden in solid tumors and challenges for biomarker application. Cancer Treat Rev. 2020;89:102084. doi: 10.1016/j.ctrv.2020.102084. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hatakeyama K, Nagashima T, Ohshima K, et al. Characterization of tumors with ultralow tumor mutational burden in Japanese cancer patients. Cancer Sci. 2020;111:3893–3901. doi: 10.1111/cas.14572. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Fromer M, Moran JL, Chambert K, et al. Discovery and statistical genotyping of copy-number variation from whole-exome sequencing depth. Am J Hum Genet. 2012;91:597–607. doi: 10.1016/j.ajhg.2012.08.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bishop JA, Gagan J, Paterson C, et al. Nonkeratinizing squamous cell carcinoma of the sinonasal tract with DEK-AFF2: further solidifying an emerging entity. Am J Surg Pathol. 2020;45:718–720. doi: 10.1097/PAS.0000000000001596. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Todorovic E, Truong T, Eskander A, et al. Middle ear and temporal bone nonkeratinizing squamous cell carcinomas with DEK-AFF2 fusion: an emerging entity. Am J Surg Pathol. 2020;44:1244–1250. doi: 10.1097/PAS.0000000000001498. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Brown CS, Abi Hachem R, Pendse A, et al. Low-grade papillary schneiderian carcinoma of the sinonasal cavity and temporal bone. Ann Otol Rhinol Laryngol. 2018;127:974–977. doi: 10.1177/0003489418803391. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Carnevale S, Ferrario G, Sovardi F, et al. Low-grade papillary schneiderian carcinoma: report of a case with molecular characterization. Head Neck Pathol. 2020;14:799–802. doi: 10.1007/s12105-019-01067-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Jeong HJ, Roh J, Lee BJ, et al. Low-grade papillary schneiderian carcinoma: a case report. Head Neck Pathol. 2018;12:131–135. doi: 10.1007/s12105-017-0832-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Williamson A, Sharma R, Cooper L, et al. Low-grade papillary schneiderian carcinoma; rare or under-recognised? Otolaryngol Case Rep. 2019;11:100107. doi: 10.1016/j.xocr.2019.02.001. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Zhai C, Wang H, Li S, et al. Clinicopathological analysis of low-grade papillary Schneiderian carcinoma: report of five new cases and review of the literature. Histopathology. 2021 (online ahead of print). [DOI] [PubMed]

- 23.King RJ, Yu F, Singh PK. Genomic alterations in mucins across cancers. Oncotarget. 2017;8:67152–67168. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.17934. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Mukhopadhyay P, Chakraborty S, Ponnusamy MP, et al. Mucins in the pathogenesis of breast cancer: implications in diagnosis, prognosis and therapy. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2011;1815:224–240. doi: 10.1016/j.bbcan.2011.01.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ali MS, Pearson JP. Upper airway mucin gene expression: a review. Laryngoscope. 2007;117:932–938. doi: 10.1097/MLG.0b013e3180383651. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Mountzios G, Rampias T, Psyrri A. The mutational spectrum of squamous-cell carcinoma of the head and neck: targetable genetic events and clinical impact. Ann Oncol. 2014;25:1889–1900. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdu143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Perez Sayans M, Chamorro Petronacci CM, Lorenzo Pouso AI, et al. Comprehensive genomic review of TCGA head and neck squamous cell carcinomas (HNSCC) J Clin Med. 2019;8:1896. doi: 10.3390/jcm8111896. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Stransky N, Egloff AM, Tward AD, et al. The mutational landscape of head and neck squamous cell carcinoma. Science. 2011;333:1157–1160. doi: 10.1126/science.1208130. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Udager AM, McHugh JB, Goudsmit CM, et al. Human papillomavirus (HPV) and somatic EGFR mutations are essential, mutually exclusive oncogenic mechanisms for inverted sinonasal papillomas and associated sinonasal squamous cell carcinomas. Ann Oncol. 2018;29:466–471. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdx736. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Udager AM, Rolland DCM, McHugh JB, et al. High-frequency targetable EGFR mutations in sinonasal squamous cell carcinomas arising from inverted sinonasal papilloma. Can Res. 2015;75:2600–2606. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-15-0340. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.