Abstract

Background

Cervical cancer is the second most common cancer and the leading cause of cancer‐related death in Ethiopian women. About 77.6% of women died of 6294 new cases reported in 2019. Early screening for cervical cancer has substantially reduced morbidity and mortality attributed to it. In Ethiopia, most of the women visit the health facilities at the late stage of the disease in which the offered intervention is not promising. Therefore, we aimed to assess the level of cervical cancer screening uptake and its determinant among women of Ambo town, Ethiopia.

Methods

Community‐based cross‐sectional study was conducted among 422 women aged 20–65 years. An interviewer‐administered questionnaire was used to collect the data. Data were analyzed using SPSS version 25. Estimates were presented using an odds ratio (OR) with 95% CI. Statistical significance was declared at a p value of <0.05.

Results

In the present study, 392 women were participated giving a response rate of 93%. Only 8.7% (34) of the study participants were received cervical cancer screening in their lifetime. Being in the age group of 30–39 years (AOR = 3.2, 95% CI: 1.22, 8.36), having cervical cancer‐related discussions with a healthcare provider (AOR = 3.5; 95% CI: 1.17, 10.7), and knowing the availability of cervical cancer screening service (AOR = 2.8; 95% CI: 1.03, 7.87) were significantly associated with uptake of cervical cancer screening.

Conclusion

In this study, cervical cancer screening uptake is very low. Our study identifies clues for determinants of cervical cancer screening uptake. Thus, further studies using a better study design might be helpful to explore determinants of low utilization of CC screening services and suggest an appropriate intervention that increases CC screening uptake in the study area.

Keywords: developing countries, early detection of cervical cancer, Ethiopia, uterine cervical neoplasms

CC screening Uptake, Ambo, Ethiopia.

1. INTRODUCTION

Cervical cancer (CC) is cancer that arises from the cervix of the uterus. It is the fourth most prevalent cause of cancer deaths among women worldwide, accounting for 311,000 women's deaths annually. 1 , 2 More than 99% of cervical cancer cases result due to infection with high‐risk human papillomaviruses (HPV subtypes 16 and 18), which is transmitted through sexual contact. 3 , 4 Cervical cancer‐related mortality is reducing in affluent countries as the launch of the formal screening program. 5 In contrast, the burden and mortality as a result of CC are increasing in low‐ and middle‐income countries (LMICs) due to the absence of well‐organized screening and HPV vaccination services. 4 , 6 , 7 According to a 2015 report, of 270,000 cervical cancer deaths, 243,000 deaths were occurred in LMICs. 4

Cervical cancer is the leading cause of cancer‐related mortality in African women. The prevalence of HPV infection in women with normal cytology was 24% in sub‐Saharan African (SSA) countries, followed by Eastern Europe (21%), and Latin America (16%). 8 The disease is steadily increasing and result in more than 75,000 new cases and 50,000 deaths per year in SSA. 9 , 10 Of a total 443,000 women deaths predicted in 2030, about 90% of deaths will occur in SSA. 1 , 11 Ethiopia also shares a higher incidence of cervical cancer and mortality attributed to it. In 2010, it was estimated that 20.9 million women were at risk of developing cervical cancer with an estimated 4,648 and 3235 new cases and deaths, respectively. 12 As to 2019 report of the country HPV information center, about 4,884 Ethiopian women died of 6294 new cases. 13 Cervical cancer is the second most common cancer and the principal cause of cancer‐related death among Ethiopian women. 12 , 14

Unlike other reproductive organ cancers, cervical cancer is potentially preventable. Effective screening programs can lead to a significant reduction in the morbidity and mortality associated with CC. 5 , 15 , 16 In high‐income countries, regular screening with cytology has been shown to lower the risk for developing invasive cervical cancer, through detecting precancerous changes. 6 However, in LMICs, only about 5% of eligible women undergo cytology‐based screening in a 5‐year period. 6 , 17 , 18 In almost all LMICs, cytology‐based services are limited to an advanced and higher level of health facilities or private laboratories in urban areas that are only accessed by the limited number of women. 6 , 12

In Ethiopia, due to lack of trained and skilled professionals, shortage of supplies, and well‐organized surveillance, scaling‐up and implementation of cytology‐based cervical cancer screening program is ineffective. 12 However, visual inspection with acetic acid (VIA) is the commonest cervical cancer screening method that offered in most public health facilities of Ethiopia. 12 It is an evidence‐based and affordable alternative approach for cervical cancer screening in low‐resource settings including Ethiopia. 6 , 19 , 20 Studies have shown though it requires fewer resources and is feasible to carry out in low‐level health facilities, VIA is comparable sensitive to detect precancerous lesions to that of cervical cytology. 21 A single round screening for CC by the VIA method reduced its incidence and mortality by 25% and 35%, respectively. 21 In addition, VIA provides immediate results, consequently, promoting the linkage of screening with treatment. 19 This “see and treat” method or single visit approach (SVA) ensures adherence to treatment soon after diagnosis and reduces the risk that women will get lost in the referral system. 19

Although, WHO recommended CC screening at the age of 30–49 years 22 and its screening at 21–65 years substantially reduces its incidence, 23 advanced stage, 24 and mortality 21 , 23 , 24 , 25 ; still, there are different barriers that hinder the utilization of the screening services. Socio‐economic status, 26 , 27 , 28 public awareness, 28 , 29 fear of cancer and outcomes of screening, 28 , 29 , 30 and healthcare access 27 , 28 , 30 were barriers of cervical cancer screening uptake mainly in LMICs. Conversely, awareness of cervical cancer, family history of the disease, and experiencing the signs and symptoms of the disease were facilitators of its utilization. 28

In the study area, most of the women visit health facilities at the later stage of the disease after it gets worsen than get screened at the earlier stage and prevents its consequence. Besides, the number of health facilities that offered the CC screening service is very limited. To date, there is no community‐based study yet conducted that assesses the level of CC screening utilization and its determinants in women of Ambo town. Thus, we aimed to investigate the level of screening service and its determinants in women of Ambo town, western Oromia, Ethiopia.

2. METHODS

2.1. Study area, period, and participants

A community‐based cross‐sectional study was conducted from December 01, 2017 to January 30, 2017, in Ambo town capital of west Shewa zone, western Ethiopia. The town is located 114 km to the west of Addis Ababa the capital of Ethiopia. According to the health planning, monitoring, and evaluation department report, the town has a total of 97,317 population, of which 18.6% of them were women of reproductive age group. In Ambo town, there are six subdistricts, one general and referral teaching hospital, two health centers, one Maternal and child health (MCH) clinic, and 20 private clinics that were providing different reproductive health services in the town. Currently, it is only the government hospital that provides cervical cancer screening services. All women aged between 20 and 65 years who are residing in Ambo town were the source population. Consequently, randomly selected women aged 20–65 years 23 and who reside in the town during the data collection period were the sample population.

2.2. Sample size and sampling procedure

The sample size was calculated by using the single population proportion formula with the assumption of 95% CI, 50% proportion of women who uptake cervical cancer screening services, and 5% margin of error was used to obtain a sample size of 384, with adjustment of 10% nonresponse, the final sample size was 422.

From six subdistricts of Ambo town, three subdistricts, namely subdistricts 01, 02, and 06, were selected by a simple random sampling technique. A total of 6705, 3513, and 3306 eligible women were found in subdistricts 01, 02, and 06, respectively. From those respective subdistricts, the sample size for this study was proportionally allocated; accordingly, 209, 109, and 103 women were selected from subdistricts 01, 02, and 06, respectively. Study participants were selected by systematic random sampling technique. The first household with the eligible subject was selected by the lottery method and then every 36th household with the eligible subject was included in the study. Women aged 20–65 years were interviewed from the selected households and if there were more than one woman in the household, the lottery method was used to select one.

2.3. Data collection tools and data collectors

The questionnaire was adapted from similar studies conducted in Gonder town, 31 Jimma, 32 and India. 33 It was first prepared in English and then translated to the local language (Afan Oromo) and back‐translated into English by language experts to ensure its consistency. An interviewer‐administered pretested questionnaire was used for data collection. A pretest was done on 5% of women who live in different subdistricts to avoid contamination of information. The data were collected by six BSc Nurses and supervised by two MSc Nurses. Data collectors and supervisors were trained for 2 days before data collection. Personal identifiers were not included in the questionnaires to ensure the participants’ confidentiality. Supervisors and principal investigators checked the completeness of the questionnaires daily.

The tool covers variables such as sociodemographic characteristics, reproductive and sexual history, cervical cancer and screening knowledge, and cervical cancer screening uptake.

2.4. Operational definitions

2.4.1. Cervical cancer screening uptake

The proportion of women who have ever been screened for cervical cancer at least once in their lifetime. 34

2.5. Data processing and analysis

Data were coded, entered, and cleaned using Epi info version 3.5.1 and exported to SPSS version 25 statistical package for analyses. Descriptive statistics were computed and presented using tables and figures. The outcome variable is dichotomous coded as “1” when the respondents were screened for CC, otherwise “0.” Frequencies and proportions were calculated for a description related to socio‐demographic and other variables. Relationships between dependent and independent variables were investigated using the Binary logistic regression model. Those variables with p‐value below 0.25 in bivariate logistic regression were included in a multivariate logistic regression model for controlling potential confounding effects. The independent predictors for cervical cancer screening uptake are presented using an adjusted odds ratio (AOR) with its 95% CI. A statistical significance was established as p < 0.05.

3. RESULTS

3.1. Sociodemographic characteristics

A total of 392 women aged 20–65 years old were interviewed making a 92.9% response rate. The mean age of the study participants was 30.1 years (±9.1 SD). The majority (96.4%) of the respondents were from the Oromo ethnic group. About two‐thirds of the women were married, and 117 (29.8%) of them completed college and above. Nearly, half (48%) of the women were housewives in their occupation (Table 1).

TABLE 1.

Sociodemographic characteristics of study participants in Ambo town western Oromia, Ethiopia, December–January 2017

| Variable (n = 392) | Category | Frequency | Percentage |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | 20–29 | 228 | 58.2 |

| 30–39 | 109 | 27.8 | |

| 40–49 | 34 | 8.7 | |

| >49 | 21 | 5.4 | |

| Ethnicity | Oromo | 378 | 96.4 |

| Others a | 14 | 3.6 | |

| Religion | Orthodox | 151 | 38.5 |

| Protestant | 228 | 58.2 | |

| Others b | 13 | 3.3 | |

| Marital status | Single | 97 | 24.7 |

| Married | 254 | 64.8 | |

| Divorced | 17 | 4.3 | |

| Widowed | 24 | 6.2 | |

| Educational status | Illiterate | 67 | 17.1 |

| Attend primary | 103 | 26.3 | |

| Attend secondary | 105 | 26.8 | |

| College and above | 117 | 29.8 | |

| Occupation | House wife | 88 | 48 |

| Private employee | 42 | 10.7 | |

| Governmental employee | 80 | 20.4 | |

| Daily laborer | 38 | 9.7 | |

| Student | 44 | 11.2 | |

| Income | No income | 37 | 9.4 |

| 100–1000 ET birr | 157 | 40.1 | |

| >1000 ET birr | 198 | 50.5 |

Amhara and Gurage.

Catholic, and waqefata, Musilim.

3.2. Reproductive characteristics of the respondents

Around 256 (65.3%) of the participants had a single sexual partner, whereas the rest (34.7%) had multiple sexual partners in their lifetime. Two hundred and forty‐three (62.0%) of the participants had two and above pregnancies (Table 2).

TABLE 2.

Reproductive characteristics of the study participants in Ambo town, western Oromia, Ethiopia, December–January 2017

| Variable (n = 392) | Category | Frequency | Percent |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age at first intercourse | <18 years | 159 | 40.6 |

| ≥18 years | 233 | 59.4 | |

| Have you been pregnant | Yes | 324 | 82.7 |

| No | 68 | 17.3 | |

| Number of pregnancy | <2 | 149 | 38.0 |

| ≥2 | 243 | 62.0 | |

| Have you give birth | Yes | 300 | 76.5 |

| No | 92 | 23.5 | |

| Number of children | <2 | 156 | 39.8 |

| ≥2 | 236 | 60.2 | |

| Lifetime number of sexual partner | Single partner | 256 | 65.3 |

| Multiple partner | 136 | 34.7 | |

| History of abortion | Yes | 47 | 12.0 |

| No | 345 | 88.0 | |

| History of contraceptive use | Yes | 208 | 53.1 |

| No | 184 | 46.9 |

3.3. Knowledge of cervical cancer

Three hundred and eight (78.6%) subjects have ever heard of cervical cancer; mass media was the most source of information reported by study subjects (Figure 1). Of the study participants, only 180 (45.9%) of them know of cervical cancer, whereas more than half (54.1%) of the women did not know cancer of the cervix. Most (68.3%) of the women reported unusual vaginal bleeding as the symptom of CC, whereas the rest reported vaginal discharge mixed with blood (42.2%), dyspareunia (32.2%), pelvic pain (12.8%), and the least reported back pain (2.2%) as the symptom of CC. Regarding the preventive mechanisms of cervical cancer, only 45 (11.5%) and 15 (3.8%) of the women knew HPV vaccination and screening for cervical cancer prevent CC, respectively.

FIGURE 1.

Sources of information of cervical cancer reported by the study subjects (multiple responses were considered; thus the sum might be more than sample size)

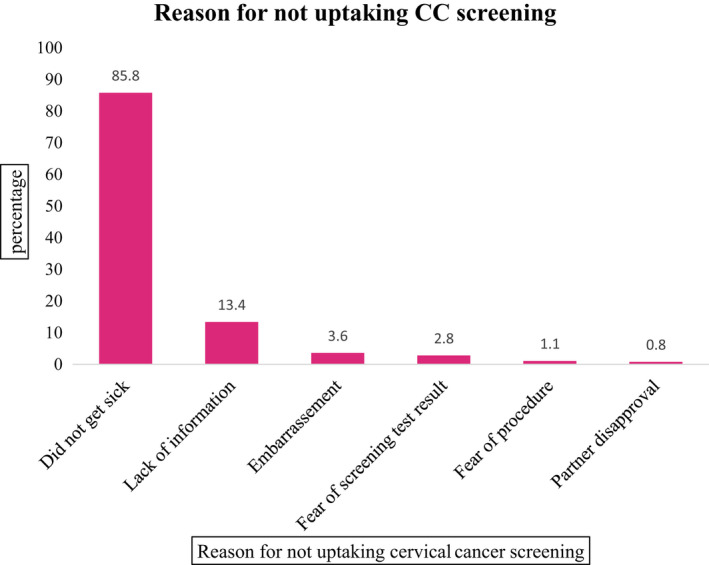

3.4. Cervical cancer screening uptake and reason for not getting screened

Only 34 (8.7%) of the women had ever screened for cervical cancer in their lifetime. However, 247(63.0%) of the women had knowledge about cervical cancer screening. Visual inspection with acetic acid (VIA) (44.1%) was the most screening type reported by respondents who had ever screened for cervical cancer, followed by a blood test (35.3%), and papanicolaou (Pap) test (20.6%). Not getting sick of CC is the main reason for the nonutilization of CC screening services (Figure 2).

FIGURE 2.

Main reason for not uptaking cervical cancer screening by women of Ambo town, western Oromia, Ethiopia, December–January 2017

3.5. Factors associated with uptake of cervical cancer screening

In bivariate logistic regression analysis, age, knowing the availability of the screening service in the public hospital, history of early sexual initiation, know the consequence of advanced cervical cancer (metastasis and bleeding), knowledge of CC screening, and discussion on cervical cancer with healthcare providers were statistically significant with the uptake of cervical cancer screening. However, in multivariable logistic regression analysis, age, knowledge on the consequence of advanced cervical cancer (metastasis and bleeding), knowledge of CC screening, and discussion with healthcare providers on CC screening were remained significantly associated with cervical cancer screening uptake (Table 3).

TABLE 3.

Determinants of cervical cancer screening uptake among women of Ambo town, western Oromia, Ethiopia, December–January 2017

| Variables | Total | Cervical cancer screening uptake | COR, 95%CI | AOR, 95% CI | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Yes | No | ||||

| Age (years) | |||||

| 20–29 | 228 | 10 (4.4) | 218 (95.6) | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| 30–39 | 109 | 14 (12.8) | 95 (87.2) | 3.2 (1.4,7.5)* | 3.2 (1.2,8.4)* |

| 40–49 | 34 | 6 (17.6) | 28 (82.4) | 4.7 (1.6,13.8)* | 4.8 (1.4,16.4)* |

| >49 | 21 | 4 (19.0) | 17 (81.0) | 5.1 (1.5,18.1)* | 4.3 (0.9,19.6) |

| Give birth to many children | |||||

| Yes | 80 | 15 (18.8) | 65 (81.3) | 3.6 (1.7,7.4)* | 2.7 (1.3,5.9)* |

| No | 312 | 19 (6.1) | 293 (93.9) | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| Screening service availability | |||||

| Yes | 48 | 8 (16.7) | 40 (83.3) | 2.5 (1.0,5.8)* | 1.9 (0.8,4.8) |

| No | 344 | 26 (7.6) | 318 (92.4) | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| Knew metastasis | |||||

| Yes | 53 | 11 (20.8) | 42 (79.2) | 3.6 (1.6,7.9)* | 2.9 (1.2,6.9)* |

| No | 339 | 23 (6.8) | 316 (93.2) | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| Knew bleeding | |||||

| Yes | 30 | 9 (30.0) | 21 (70.0) | 5.8 (2.4,13.9)* | 3.1 (1.2,8.3)* |

| No | 362 | 25 (6.9) | 337 (93.1) | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| Knowledge on CC screening | |||||

| Yes | 247 | 29 (11.7) | 218 (88.3) | 3.7 (1.4,9.9)* | 2.8 (1.0,7.9)* |

| No | 145 | 5 (3.4) | 140 (96.6) | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| Knowledge on CC | |||||

| Yes | 180 | 19 (10.6) | 161 (89.4) | 1.6 (0.8,3.2) | 1.0 (0.4,2.2) |

| No | 212 | 15 (7.1) | 197 (92.9) | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| Discussed CC with HCP | |||||

| Yes | 31 | 6 (19.4) | 25 (80.6) | 2.9 (1.1,7.5)* | 3.5 (1.2,10.7)* |

| No | 361 | 28 (7.8) | 333 (92.2) | 1.00 | 1.00 |

Abbreviations: CC, cervical cancer; HCP, healthcare provider.

p‐value <0.05.

This study indicated that those women who were in the age group of 30–39 years and 40–49 years were 3.2 times (AOR = 3.2; 95% CI [1.22,8.36]) and 4.8 times (AOR = 4.8;95% CI [1.42,16.41]) more likely to uptake cervical cancer screening compared with those women whose ages between 20 and 29 years, respectively. Those women who knew giving birth to many children as a risk factor for cervical cancer were 2.7 times (AOR = 2.7; 95% CI [1.26, 5.98]) more likely to utilize cervical cancer screening compared with their counterparts. Women who had knowledge about cervical cancer screening were 2.8 times (AOR = 2.8; 95% CI [1.03, 7.87]) more likely to uptake cervical cancer screening than their counterparts. Furthermore, the present study found that knowledge on the consequences of advanced cervical cancer increases the uptake of cervical cancer screening by the study subjects. Those women who knew metastasis and bleeding were the consequence of advanced cervical cancer were 2.9 times (AOR = 2.9; 95% CI [1.20, 6.95]) and 3.1times (AOR = 3.1; 95% CI [1.16, 8.29]) more likely to utilize the CC screening service than their counterparts, respectively.

4. DISCUSSION

A total of 392 women have participated in the present study gives a response rate of 92.9%. In this study, despite a relatively high level of respondents, having knowledge of cervical cancer (45.9%) and its screening (63.0%), only 8.7% of the women utilized cervical cancer screening services in their lifetime. The finding of the present study is lower than the former studies conducted in Hosanna town (10%), 35 Dessie town (11%), 36 Mekele town (20%), 37 and Debremarkos town (21%) of Ethiopia. 38 The low level of cervical cancer screening uptake in our study despite a relatively high level of knowledge of cervical cancer and its screening service might be attributed to an inadequate number of health facilities that provide cervical cancer screening service, health‐seeking behavior of the study participants, and knowledge of the women of the preventive measures of cervical cancer.

In the study area at the time of data collection, only one hospital provide the cervical cancer screening service. Though the women were knowledgeable about cervical cancer and its screening service, the service is not easily accessible by all eligible women due to an inadequate number of service provision centers in the study area. Besides, the health‐seeking behavior of women, particularly of preventive services is very low. In the present study, only 3.8% of the women knew as cervical cancer screening prevents cervical cancer, this indicates as there is a huge gap between knowledge of CC and its prevention methods. Likewise, our study also reveals that not getting sick is the main reason for the nonutilizing of cervical cancer screening. This highlighted if they perceive that they are healthy and did not seek the services as early as possible rather they seek it after they experienced the clinical feature of the diseases due to its advancement. Our study is in line with the studies conducted in Uganda 39 and Ethiopia 40 , 41 that point out most women present with cervical cancer at an advanced stage due to poor health‐seeking behavior.

Another study 42 also indicated that 17% of undergraduate female University students underwent cervical cancer screening in their lifetime. The level of screening from this study was also higher than that of the present study; the reason might be due to the variation of awareness level among the University students and women in the general community. Studies showed that women who had a higher level of education 41 , 43 , 44 and knowledge on cervical cancer, 35 , 36 , 37 and its screening 37 , 44 were more utilized the screening services than their counterparts. Conversely, the cervical cancer screening level of the present study was higher than the community‐based studies conducted among women in Finote‐Selam city (7.3%), northwest Ethiopia, 45 in Butajira district, (2.3%), southern Ethiopia, 41 and in Debre Markos town (5.4%), northwest Ethiopia. 44 The inconsistencies might be due to the difference in study settings and age groups included in the studies.

The current study revealed that age (being within the age group of 30–39 years and 40–49 years), knew metastasis and bleeding are the consequences of advanced CC, and knowledge on CC screening, discussion with healthcare providers on CC screening, and give birth to many children were predictors of cervical cancer screening uptake. Women in the age group of 30–39 years (3.2 times) and 40–49 years (4.8 times) are more likely to be screened for cervical cancer compared with those aged between 20 and 29 years. The finding was in line with studies conducted in public hospitals found in the Tigray region 46 and Mekele town 37 that reported being aged between 30 and 39 years were two times more likely to utilize screening services than those who were 21–29 years old. Moreover, the likelihood of cervical cancer screening uptake is increasing as age increased. Those women whose age ranges 40–49 years were 4 times, 46 3.1 times, 44 and 2.4 times 47 more likely to utilize the screening services compared with 21–29 years old. Also studies conducted in Dessie town, 36 Debre Markos town, 38 and Finote Selam city 45 revealed that women aged between 34 and 49 years were 6.0 times, 3.2 times, and 2.8 times more likely to be screened for CC than the younger age group, respectively.

Furthermore, discussing with healthcare providers about cervical cancer screening is also increasing its utilization; those women who had ever discussed with the healthcare providers about CC screening were 3.5 times more likely to be screened than their counterparts. This finding is also supported by studies conducted in Debre‐Markos town and Bahir‐Dar city, 38 , 48 which revealed that being informed about CC screening by health professionals increases its utilization by 6.8 folds.

Former studies also indicated that knowledge on cervical cancer screening was increased CC screening uptake by 2.36 fold 37 and 4.02 fold. 44 The present study also in accordance with those studies; women who had knowledgeable of cervical cancer screening were 2.8 times more likely to uptake cervical screening than those who did not know the screening. Our study also reveals knowledge of metastasis and bleeding due to advanced CC increases cervical cancer screening utilization. Those women who knew metastasis (2.2 times) and bleeding (3.1 times) are occurred due to advanced CC were more likely to utilize CC screening than those who did not know the advanced cervical cancer consequence.

Our study identifies the main reason for not up‐taking cervical cancer screening. Self‐perceived health (85.8%), lack of information (13.4%), and fear of screening test results (2.8%) were the frequently reported reason for the nonutilization of CC screening by the study participants. This result is also in harmony with studies conducted in Hossana, southern Ethiopia, 49 and Addis Ababa 50 that indicated a lack of information and awareness were barriers to CC screening uptake. A cluster‐randomized trial study conducted in Butajira district also revealed self‐assertion of being healthy and fear of screening were the main reason for nonutilizing screening services. 51

Altogether, the knowledge level of study participants regarding the preventive measures of cervical cancer is low; only 3.8% and 11.5% of women reported screening for cervical cancer and HPV vaccine prevents cervical cancer, respectively. A Mukama T et al. found a higher level of CC preventive measures, early screening (46%), and vaccination for HPV (33.3%) 52 than the present study. The inconsistencies might be attributed to sample size and study setting. In Ethiopia, the HPV vaccine was launched for the first time in 2018 with the support of the Global Alliance for vaccine and immunization (GAVI) for girls who are 14 years old. 53 Currently, the vaccine was delivered through a school‐based approach to access all eligible girls of Ethiopia. 53 Due to the vaccination against HPV being launched 1 year later after the current study, the women who participated in the present study were not get vaccinated.

Though Ethiopian women are willing to vaccinate their children for HPV 54 , 55 still there are challenges that affect its effective utilization. Ineffectiveness of the recently provided vaccine (HPV2 and HPV4) for other prevalent strains of HPV (HPV‐52, 56 , 57 HPV‐56, 57 , 58 HPV‐58, 57 and HPV‐31 57 ) in Ethiopia, high vaccine costs, inadequate delivery system, and lack of community involvement to create awareness about CC and early screening tools are challenges that hinder effective utilization HPV vaccination in Ethiopia. 31 , 40 , 59 , 60 , 61 Therefore, targeting the common barriers of HPV vaccination for its effective utilization and increasing the accessibility of CC screening through mainstreaming the cervical cancer screening service in all units of the health facility to reach more eligible women and increase their awareness level, decentralization of cervical cancer screening services at all levels of health facilities, and offering the CC screening for free at all health facilities are of paramount importance for reducing morbidity and mortality attributed to cervical cancer in Ethiopian women.

4.1. Limitation of the study

The descriptive nature of the study design might not be strong as other analytic or experimental study designs to reach on sound conclusion and valid recommendations that intervene to increase CC screening uptake.

5. CONCLUSION

In this study, cervical cancer screening uptake is very low. Our study identifies clues for determinants of cervical cancer screening uptake. Thus, further studies using a better study design might be helpful to explore determinants of low utilization of CC screening services and suggest an appropriate intervention that increases CC screening uptake in the study area.

CONFLICT OF INTERESTS

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

Shewaye Fituma Natae: conceptualization, analysis, and write up and manuscript preparation. Digafe Tsegaye Nigatu: analysis, interpretation of the data, and review the manuscript. Wakeshe Willi Mengesha: involves in the preparations of the manuscript and reviewing the paper. Mulu kitaba Negawo: involves in the preparations of the manuscript and reviewing the paper. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

ETHICS APPROVAL AND CONSENT TO PARTICIPATE

The study was approved by the ethical Review committee of the College of Medicine and Health Sciences (CMHS‐ERC) of Ambo University, Ethiopia and all performed procedures were in accordance with the 1964 Helsinki declaration and its later amendments. Written informed consent was sought from all participants after the aim of the study was introduced. Confidentiality of the gathered information was assured to the interviewee.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We are grateful to Ambo University for supporting this research. Additionally, the authors would like to thank the study participants, data collectors, and supervisors.

Natae SF, Nigatu DT, Negawo MK, Mengesha WW. Cervical cancer screening uptake and determinant factors among women in Ambo town, Western Oromia, Ethiopia: Community‐based cross‐sectional study. Cancer Med. 2021;10:8651–8661. doi: 10.1002/cam4.4369

Funding information

No funding was obtained for this study.

DATA AVAILABILITY STATEMENT

The data sets used and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

REFERENCES

- 1. Bray F, Ferlay J, Soerjomataram I, Siegel RL, Torre LA, Jemal A. Global cancer statistics 2018: GLOBOCAN estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for 36 cancers in 185 countries. CA Cancer J Clin. 2018;68(6):394‐424. doi: 10.3322/caac.21492 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. WHO . Cervical Cancer. 2018. http://www.who.int/cancer/prevention/diagnosis‐screening/cervical‐cancer/en/

- 3. Crosbie EJ, Einstein MH, Franceschi S, Kitchener HC. Human papillomavirus and cervical cancer. Lancet. 2013;382:889‐899. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(13)60022-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Arbyn M, Weiderpass E, Bruni L, et al. Estimates of incidence and mortality of cervical cancer in 2018: a worldwide analysis. Lancet Glob Heal. 2019;8(2):e191‐e203. doi: 10.1016/S2214-109X(19)30482-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Cohen PA, Jhingran A, Oaknin A, Denny L. Cervical cancer. Lancet. 2019;393(10167):169‐182. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(18)32470-X [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Pimple S, Mishra G, Shastri S. Global strategies for cervical cancer prevention. Curr Opin Obstet Gynecol. 2016;28(1):4‐10. doi: 10.1097/GCO.0000000000000241 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Vu M, Yu J, Awolude OA, Chuang L. Cervical cancer worldwide. Curr Probl Cancer. 2018;42(5):457‐465. doi: 10.1016/j.currproblcancer.2018.06.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Bosch FX, Broker TR, Forman D, et al. Comprehensive control of human papillomavirus infections and related diseases. Vaccine. 2013;31S:F1‐F31. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2013.10.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. De Vuyst H, Alemany L, Lacey C, et al. The burden of human papillomavirus infections and related diseases in sub‐saharan Africa. Vaccine. 2013;31S:F32‐F46. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2012.07.092 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Ferlay J, Shin HR, Bray F, Forman D, Mathers C, Parkin DM. Estimates of worldwide burden of cancer in 2008: GLOBOCAN 2008. Int J Cancer. 2010;127(12):2893‐2917. doi: 10.1002/ijc.25516 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Mboumba Bouassa RS, Prazuck T, Lethu T, Jenabian MA, Meye JF, Bélec L. Cervical cancer in sub‐Saharan Africa: a preventable noncommunicable disease. Expert Rev Anti Infect Ther. 2017;15(6):613‐627. doi: 10.1080/14787210.2017.1322902 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. FDRE M . Guideline for Cervical Cancer Prevention and Control in Ethiopia; 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 13. ICO . Human Papillomavirus and Related Diseases Report. 2016. www.hpvcentre.com [Google Scholar]

- 14. WHO . Human Papillomavirus and Related Cancers. 2010. https://www.unav.edu/documents/ [Google Scholar]

- 15. Ronco G, Dillner J, Elfström KM, et al. Efficacy of HPV‐based screening for prevention of invasive cervical cancer: follow‐up of four European randomised controlled trials. Lancet. 2014;383(9916):524‐532. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(13)62218-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Ogilvie GS, van Niekerk D, Krajden M, et al. Effect of screening with primary cervical HPV testing vs cytology testing on high‐grade cervical intraepithelial neoplasia at 48 months: the HPV FOCAL randomized clinical trial. Obstet Gynecol Surv. 2018;73(11):632‐634. doi: 10.1097/OGX.0000000000000608 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Millar AB. Cervical cancer screening: managerial guidelines. Published Online. 1992;1‐50. http://whqlibdoc.who.int/publications/1992/9241544473.pdf

- 18. Research WA for HP and S, Kwefie, Path , et al. Prevention of cervical cancer through screening using visual inspection with acetic acid (VIA) and treatment with cryotherapy. Outlook. 2003;II(1):33. http://www.who.int/reproductivehealth/publications/cancers/9789241503860/en/ [Google Scholar]

- 19. Toliman PJ, Kaldor JM, Tabrizi SN, Vallely AJ. Innovative approaches to cervical cancer screening in low‐ and middle‐income countries. Climacteric. 2018;21(3):235‐238. doi: 10.1080/13697137.2018.1439917 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Sankaranarayanan R. Screening for cancer in low‐ and middle‐income countries. Ann Glob Heal. 2014;80(5):412‐417. doi: 10.1016/j.aogh.2014.09.014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Sankaranarayanan R, Esmy PO, Rajkumar R, et al. Effect of visual screening on cervical cancer incidence and mortality in Tamil Nadu, India: a cluster‐randomised trial. Lancet. 2007;370(9585):398‐406. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(07)61195-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. WHO . Guidelines for screening and treatment of precancerous lesions for cervical cancer prevention. WHO Guidel. Published Online 2013;60. http://www.who.int/reproductivehealth/publications/cancers/screening_and_treatment_of_precancerous_lesions/en/index.html [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Curry SJ, Krist AH, Owens DK, et al. Screening for cervical cancer us preventive services task force recommendation statement. JAMA. 2018;320(7):674‐686. doi: 10.1001/jama.2018.10897 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Schaapveld M, Aleman BM, van Eggermond AM, et al. HPV Screening for Cervical Cancer in Rural India. N Engl J Med. Published online 2015:687‐696. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1505949 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Landy R, Pesola F, Castañón A, Sasieni P. Impact of cervical screening on cervical cancer mortality: estimation using stage‐specific results from a nested case‐control study. Br J Cancer. 2016;115(9):1140‐1146. doi: 10.1038/bjc.2016.290 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Lea CS, Perez‐Heydrich C, Des Marais AC, et al. Predictors of cervical cancer screening among infrequently screened women completing human papillomavirus self‐collection: my body my test‐1. J Women’s Heal. 2019;28(8):1095‐1104. doi: 10.1089/jwh.2018.7141 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Denny L. Control of cancer of the cervix in low‐ and middle‐income countries. Ann Surg Oncol. 2015;22(3):728‐733. doi: 10.1245/s10434-014-4344-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Ndejjo R, Mukama T, Kiguli J, Musoke D. Knowledge, facilitators and barriers to cervical cancer screening among women in Uganda: a qualitative study. BMJ Open. 2017;7(6):1‐8. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2017-016282 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Yang H, Li SP, Chen Q, Morgan C. Barriers to cervical cancer screening among rural women in eastern China: a qualitative study. BMJ Open. 2019;9(3):1‐8. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2018-026413 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Lim JNW, Ojo AA. Barriers to utilisation of cervical cancer screening in Sub Sahara Africa: a systematic review. Eur J Cancer Care (Engl). 2017;26(1):1‐9. doi: 10.1111/ecc.12444 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Getahun F, Mazengia F, Abuhay M, Birhanu Z. Comprehensive knowledge about cervical cancer is low among women in Northwest Ethiopia. BMC Cancer. 2013;13(2): doi: 10.1186/1471-2407-13-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Bezabih M, Tessema F, Sengi H, Deribew A. Risk factors associated with invasive cervical carcinoma among women attending Jimma university specialized hospital, Southwest Ethiopia: a case control study. Ethiop J Health Sci. 2015;25(4):345‐352. doi: 10.4314/ejhs.v25i4.8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Kokane AM, Bansal AB, Pakhare AP, Kapoor N, Mehrotra R. Knowledge, attitude, and practices related to cervical cancer among adult women: a hospital‐based cross‐sectional study. J Nat Sci Biol Med. 2015;6(2):324‐328. doi: 10.4103/0976-9668.159993 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Fitzmaurice C, Allen C, Barber RM, et al. Global, regional, and national cancer incidence, mortality, years of life lost, years lived with disability, and disability‐adjusted life‐years for 32 cancer groups, 1990 to 2015: a systematic analysis for the global burden of disease study. JAMA Oncol. 2017;3(4):524‐548. doi: 10.1001/jamaoncol.2016.5688 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Aweke YH, Ayanto SY, Ersado TL. Knowledge, attitude and practice for cervical cancer prevention and control among women of childbearing age in Hossana Town, Hadiya zone, Southern Ethiopia: community‐based cross‐sectional study. Published Online. 2017;1‐18. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0181415 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 36. Tefera F, Mitiku I. Uptake of cervical cancer screening and associated factors among 15–49‐year‐old women in dessie town, Northeast Ethiopia. J Cancer Educ. 2017;901‐907. doi: 10.1007/s13187-016-1021-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Bayu H, Berhe Y, Mulat A, Alemu A. Cervical cancer screening service uptake and associated factors among age eligible women in mekelle zone, Northern Ethiopia, 2015: a community based study using health belief model. Published Online. 2016:1‐13. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0149908 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 38. Bante SA, Getie SA, Getu AA, Mulatu K, Fenta SL. Uptake of pre‐cervical cancer screening and associated factors among reproductive age women in Debre Markos town, Northwest Ethiopia. BMC Public Health. 2017;2019:1‐9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Hasahya OT, Berggren V, Sematimba D, Nabirye RC, Kumakech E. Beliefs, perceptions and health‐seeking behaviours in relation to cervical cancer: a qualitative study among women in Uganda following completion of an HPV vaccination campaign. Glob Health Action. 2016;9(1):1‐9. doi: 10.3402/gha.v9.29336 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Birhanu Z, Abdissa A, Belachew T, et al. Health seeking behavior for cervical cancer in Ethiopia: a qualitative study. Int J Equity Health. 2012;11(1):1‐8. doi: 10.1186/1475-9276-11-83 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Ruddies F, Gizaw M, Teka B, et al. Cervical cancer screening in rural Ethiopia: a cross‐ sectional knowledge, attitude and practice study. Published Online 2020;1‐10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 42. Gebregziabher D, Berhanie E, Birhanu T, Tesfamariam K. Correlates of cervical cancer screening uptake among female under graduate students of Aksum University, College of Health Sciences, BMC Res Notes. Published Online. 2019;1‐6. doi: 10.1186/s13104-019-4570-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 43. Agide FD, Garmaroudi G, Sadeghi R, et al. A systematic review of the effectiveness of health education interventions to increase cervical cancer screening uptake. Eur J Pub Health. 2018;1‐7. doi: 10.1093/eurpub/cky197 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Yeserah B, Id A, Anteneh KT, Enyew MM. Utilization of cervical cancer screening and associated factors among women in Debremarkos town, Amhara Region, Northwest Ethiopia: community based cross‐ sectional study. 2020;578:1‐13. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0231307 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Kasa AS, Tesfaye TD, Temesgen WA. Knowledge, attitude and practice towards cervical cancer among women in Finote Selam. Afr Health Sci. 2018;18(3):623‐636. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Id HT, Gebremariam L, Kahsay T, Berhe K. Factors affecting utilization of cervical cancer screening services among women attending public hospitals in tigray region, Ethiopia, 2018; case control study. Published Online. 2018;2019:1‐11. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0213546 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Teame H, Addissie A, Ayele W, et al. Factors associated with cervical precancerous lesions among women screened for cervical cancer in Addis Ababa, Ethiopia: a case control study. 2018;39:1‐13. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0191506 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Muluneh BA, Atnafu DD. Predictors of cervical cancer screening service utilization among commercial sex workers in Northwest Ethiopia: a case‐ control study. Published Online. 2019;1‐9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 49. Habtu Y, Yohannes S, Laelago T. Health seeking behavior and its determinants for cervical cancer among women of childbearing age in Hossana Town, Hadiya zone, Southern Ethiopia: community based cross sectional study. Published Online. 2018;1‐9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 50. Ababa A, Fentie AM, Tadesse TB, Gebretekle GB. Factors affecting cervical cancer screening uptake, visual inspection with acetic acid positivity and its predictors among women attending cervical cancer screening service. Published Online. 2020;1‐10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 51. Gizaw M, Teka B, Ruddies F, et al. Reasons for not attending cervical cancer screening and associated factors in rural Ethiopia. Cancer Prev Res. 2020;13(7):593‐600. doi: 10.1158/1940-6207.CAPR-19-0485 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Mukama T, Ndejjo R, Musabyimana A, Halage AA, Musoke D. Women’s knowledge and attitudes towards cervical cancer prevention: a cross sectional study in Eastern Uganda. BMC Womens Health. 2017;17(1):1‐8. doi: 10.1186/s12905-017-0365-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. WHO . Ethiopia Launches Human Papillomavirus Vaccine for 14 Year Old Girls; 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 54. Destaw A, Yosef T, Bogale B. Parents willingness to vaccinate their daughter against human papilloma virus and its associated factors in Bench‐Sheko zone, southwest Ethiopia. Heliyon. 2021;7(5):e07051. doi: 10.1016/j.heliyon.2021.e07051 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Alene T, Atnafu A, Mekonnen ZA, Minyihun A. Acceptance of human papillomavirus vaccination and associated factors among parents of daughters in gondar town, northwest Ethiopia. Cancer Manag Res. 2020;12:8519‐8526. doi: 10.2147/CMAR.S275038 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Bartholomeusz A, Locarnini S. Associated with antiviral therapy. Antivir Ther. 2006;55:52‐55. doi: 10.1002/jmv [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Leyh‐Bannurah SR, Prugger C, De Koning MNC, Goette H, Lellé RJ. Cervical human papillomavirus prevalence and genotype distribution among hybrid capture 2 positive women 15 to 64 years of age in the Gurage zone, rural Ethiopia. Infect Agent Cancer. 2014;9(1):1‐9. doi: 10.1186/1750-9378-9-33 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Bekele A, Baay M, Mekonnen Z, Suleman S, Chatterjee S. Human papillomavirus type distribution among women with cervical pathology ‐ a study over 4 years at Jimma Hospital, southwest Ethiopia. Trop Med Int Heal. 2010;15(8):890‐893. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-3156.2010.02552.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Gedefaw A, Astatkie A, Tessema GA. The prevalence of precancerous cervical cancer lesion among HIV‐infected women in Southern Ethiopia: a cross‐sectional study. PLoS One. 2013;8(12):1‐8. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0084519 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Wondimu YT adess . Cervical cancer: assessment of diagnosis and treatment facilities in public health institutions in Addis Ababa, Ethiopia. Ethiop Med J. 2015;53(2):65‐74. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Gebremariam T. Human papillomavirus related cervical cancer and anticipated vaccination challenges in Ethiopia. Int J Heal Sci. 2016;10(1):137‐143. doi: 10.12816/0031220 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The data sets used and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.