Abstract

Background

Allogeneic hematopoietic cell transplantation (HCT) is a widely used treatment for hematologic cancers, with survival rates ranging from 25% to 78%. Known risk factors for chronic graft-versus-host disease (cGVHD), a serious and common long-term complication, disease relapse, and mortality following HCT have been identified, but much of the variability in HCT outcomes is unexplained. Biobehavioral symptoms including depression, sleep disruption, and fatigue are some of the most prevalent and distressing for patients; yet research on biobehavioral risk factors for HCT outcomes is limited. This study evaluated patient-reported depression, sleep disruption, and fatigue as risk factors for cGVHD, disease relapse, and mortality.

Methods

Adults receiving allogeneic HCT for a hematologic malignancy (N = 241) completed self-report measures of depression symptoms, sleep quality, and fatigue (severity, interference) pre-HCT and 100 days post-HCT. Clinical outcomes were monitored for up to 6 years.

Results

Cox proportional hazard models (2-tailed) adjusting for patient demographic and medical characteristics revealed that high pre-HCT sleep disruption (Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index >9; hazard ratio [HR] = 2.74, 95% confidence interval [CI] = 1.27 to 5.92) and greater post-HCT fatigue interference (HR = 1.32, 95% CI = 1.05 to 1.66) uniquely predicted increased risk of mortality. Moderate pre-HCT sleep disruption (Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index 6-9) predicted increased risk of relapse (HR = 1.99, 95% CI = 1.02 to 3.87). Biobehavioral symptoms did not predict cGVHD incidence.

Conclusions

Biobehavioral symptoms, particularly sleep disruption and fatigue interference, predicted an increased risk for 6-year relapse and mortality after HCT. Because these symptoms are amenable to treatment, they offer specific targets for intervention to improve HCT outcomes.

Allogeneic hematopoietic cell transplantation (HCT) is a widely used treatment for hematologic cancers, with survival rates ranging from 25% to 78% (1). HCT involves intensive chemotherapy and/or radiation followed by infusion of hematopoietic cells to restore hematopoietic and immune function (2). In allogeneic transplantation, donor immune cells typically have a therapeutic effect for residual disease but carry substantial risk of complications, morbidity, and mortality (3). Following early recovery, a serious and common long-term complication is chronic graft-versus-host disease (cGVHD) in which alloreactive donor lymphocytes target recipient tissues (4,5). cGVHD occurs in 40%-70% of recipients and is a leading cause of functional limitations, morbidity, and nonrelapse mortality (1,3,6-12).

Known risk factors for adverse clinical outcomes following HCT include several patient- and transplant-related factors, although much of the variability in outcomes remains unexplained. Research suggests that depressive symptoms (7%-68%) (2,13,14), sleep disruption (32%-56%) (2,15-18), and fatigue (25%-81%) (2,19) are among the most prevalent and distressing symptoms for allogeneic HCT recipients. These symptoms tend to co-occur (2,20) and predict poor outcomes in other cancer populations (21-23), but research on biobehavioral risk factors in HCT is more limited. Several studies suggested that depression symptoms predict increased risk for mortality up to 5 years post-HCT (24-27). Only 1 study has examined sleep quality, finding that it did not predict risk for cGVHD, relapse, or mortality 1 year post-HCT (15). The influence of fatigue on HCT outcomes has not been evaluated. Because these symptoms are potentially responsive to treatment (28-31), research that carefully assesses depression, sleep disruption, and fatigue as risk factors may identify specific intervention targets to improve HCT outcomes.

The present study extends the literature on biobehavioral risk factors for HCT outcomes by investigating sleep disruption and fatigue, in addition to depression symptoms, as predictors of cGVHD, disease relapse, and overall survival (OS) in patients undergoing allogeneic HCT for hematologic malignancies. Whereas the majority of prior studies focused on a single biobehavioral symptom (eg, depression), this study examined 3 prevalent patient-reported symptoms using psychometrically robust measures. In addition, whereas most extant studies focused on pre-HCT symptoms, we evaluated symptoms pre-HCT and 100 days post-HCT. Because the 100-day post-HCT mark is considered an important recovery milestone when clinical outcomes are assessed and patients are beginning to resume more normal routines and typically experience symptom improvement (2,16,17), those who experience more persistent and severe symptoms at this time point may be at increased risk for poor outcomes (32-35). Finally, we monitored clinical outcomes for up to 6 years, one of the longest follow-up assessment periods in the published literature. Based on previous findings that depression predicts increased mortality risk post-HCT, we hypothesized that more severe pre-HCT and post-HCT depressive symptoms, sleep disruption, and fatigue would predict increased risk for cGVHD, relapse, and mortality.

Methods

Participants

Participants were 241 adults who received allogeneic HCT and follow-up care at the University of Wisconsin-Madison Carbone Cancer Center for the treatment of a hematologic malignancy (acute and chronic leukemias, lymphomas, myelodysplastic syndromes, multiple myeloma, aplastic anemia). All participants received their first allogeneic HCT, with a small number (n = 20) having undergone a previous autologous HCT. Participants were recruited for a larger longitudinal study investigating psychological, behavioral, and biological predictors of recovery and outcomes following HCT [see (17,36-38) for details]. Of the 254 allogeneic HCT participants enrolled, 241 completed measures of biobehavioral symptoms at either pre-HCT or post-HCT and were included in this analysis. Biobehavioral data were available for 224 participants at pre-HCT because of missing data and 186 participants at post-HCT because of missing data (n = 13), study attrition (n = 18), and death (n = 24).

Procedure

Participants completed questionnaires to assess biobehavioral symptoms at pre-HCT and 100 days post-HCT. Follow-up assessments were conducted at 6 months and at 1, 3, and 6 years post-HCT to monitor biobehavioral symptoms and clinical outcomes. Participants completed the questionnaires during a clinic visit or by mail. Clinical information was abstracted from medical records during each study visit. All participants provided written informed consent prior to study participation, and this investigation was approved by the University of Wisconsin-Madison institutional review board.

Measures

Depression Symptoms. The Inventory of Depression and Anxiety Symptoms (39,40) is a measure of specific symptom dimensions of major depression and related anxiety disorders that has been used in previous HCT studies (17,36,37). This study focused on the dysphoria subscale, which assesses the core emotional and cognitive symptoms of depression (eg, depressed mood, anhedonia, worry) over the prior 2 weeks, to minimize overlap with measures of sleep quality and fatigue. The subscale had high internal consistency at pre-HCT and post-HCT (Cronbach α = .89 and .86).

Sleep Quality. The Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index (PSQI) (41,42) is a well-validated measure of subjective sleep quality, latency, duration, sleep efficiency, nighttime disturbance, sleep medication use, and daytime dysfunction over the previous month. The PSQI global score is the sum of the domains. Research has shown that scores higher than 5 in healthy populations and scores above 9 in medical populations indicate meaningful sleep disruption (43,44). Thus, we used the PSQI of more than 5 cutoff as the primary measure and dummy variables to compare high (PSQI > 9) and moderate (PSQI 6-9) sleep disruption to low or no sleep disruption (PSQI ≤ 5; reference) as the secondary measure to test for evidence of a dose-response relationship between sleep disruption and risk for adverse outcomes (43).

Fatigue. The Fatigue Symptom Inventory (45,46) is a well-validated measure of subjective fatigue. It was developed for use with cancer patients and assesses fatigue severity, frequency, and interference with daily functioning over the past week (47,48). This study focused on the severity and interference subscales.

Covariates. Patient demographic and medical characteristics were evaluated as covariates based on previous research, including age, sex, disease risk index (49), conditioning regimen (myeloablative, nonmyeloablative), donor type (sibling, unrelated donor), and graft source (bone marrow, peripheral blood, umbilical cord blood) (25,50-53). Because some patients did not have data available for Karnofsky performance status (KPS; n = 25) (54,55) and HCT Comorbidity Index (n = 40) (56), these variables were evaluated in secondary models.

Definition of Outcomes

Diagnosis of cGVHD was determined based on medical record review by a medical hematologist and oncologist (MBJ) according to the National Institutes of Health cGVHD consensus criteria (9,57). Cumulative incidence of cGVHD was defined as the time from the date of transplant to cGVHD diagnosis, with patients censored at the date of death or their last clinic visit in which cGVHD could be assessed. Relapse was defined as the time from the date of transplant to recurrence of the primary disease, with patients censored at the date of death or last contact. OS was defined as the time from the date of transplant to death, with survivors censored at the date of last contact.

Statistical Analysis

The probability of cGVHD, relapse, and OS were estimated using the Kaplan-Meier method. Cox proportional hazards regression models examined pre-HCT and post-HCT biobehavioral symptoms as separate predictors of clinical outcomes. Given that death was a censoring event—and hence a competing risk—for both cGVHD and relapse models, Cox proportional hazards regressions modeled the cause-specific hazard for cGVHD and relapse, in which being “at risk” was defined as not yet experiencing the event and still being alive. Primary models adjusted for age, sex, conditioning regimen, donor type, graft source, and disease risk index. Secondary models included KPS and comorbidities as additional covariates. Follow-up analyses included pre-HCT symptoms in a single statistical model and post-HCT symptoms in a separate model. Exploratory analyses examined interactions between each biobehavioral symptom and sex and race (White vs non-White) as separate predictors of clinical outcomes, adjusting for covariates as described above. All statistical significance tests were 2-sided using a P value of less than .05 threshold. The proportional hazards assumption was assessed using the weighted residual approach (58) as implemented in the cox.zph function in the R survival package. There was a deviation in proportionality for the covariate age in pre-HCT models and KPS in post-HCT models. However, sensitivity analyses that stratified by age and KPS yielded the same findings. Adjusted survival curves were estimated from the Cox proportional hazards regression models using the ggadjustedcurves function in the R survminer package.

Results

Participant Characteristics

Patient demographic and medical characteristics appear in Table 1. The mean age was 50.9 years, and a majority self-identified as male and White or non-Hispanic. Among those experiencing the event, median days to the event was 193 (range = 80-1145; n = 111) for cGVHD, 191 (range = 19-2159; n = 85) for relapse, and 252 (range = 1-1877; n = 105) for death. Descriptive statistics for biobehavioral symptoms are shown in Table 2. Symptoms were moderately correlated at pre-HCT and post-HCT (r = .18-.46), with larger correlations observed between depression symptoms and sleep disruption (r = .51) and fatigue interference (r = .53-.63; Supplementary Table 1, available online).

Table 1.

Participant demographic and medical characteristics (n = 241)a

| Characteristics | Descriptive statistics | No. missing |

|---|---|---|

| Mean age (SD), y | 50.85 (12.11) | 0 |

| Female sex, No. (%) | 95 (39.4) | 0 |

| Race/ethnicity, No. (%) | 14 | |

| White/Non-Hispanic | 220 (91.3) | |

| Native American | 3 (1.2) | |

| Other | 3 (1.2) | |

| African American | 1 (0.4) | |

| Relationship status, No. (%) | 13 | |

| Married | 181 (75.1) | |

| Single | 30 (12.4) | |

| Divorced | 14 (5.8) | |

| Widowed | 2 (0.8) | |

| Separated | 1 (0.4) | |

| Educational attainment, No. (%) | 15 | |

| Less than 12 years | 6 (2.5) | |

| High school diploma | 127 (52.7) | |

| Bachelor’s degree | 61 (25.3) | |

| Advanced degree | 32 (13.3) | |

| Employment status, No. (%) | 14 | |

| Full-time | 80 (33.2) | |

| Part-time | 13 (5.4) | |

| Disabled | 84 (34.9) | |

| Retired | 37 (15.4) | |

| Homemaker | 11 (4.6) | |

| Student | 2 (0.8) | |

| Diagnostic category, No. (%) | 0 | |

| Acute myeloid leukemia | 85 (35.3) | |

| Non-Hodgkin lymphoma | 45 (18.7) | |

| Myelodysplastic syndrome | 45 (18.6) | |

| Acute lymphocytic leukemia | 34 (14.1) | |

| Chronic lymphocytic leukemia | 13 (5.4) | |

| Chronic myeloid leukemia | 7 (2.9) | |

| Aplastic anemia | 5 (2.1) | |

| Hodgkin lymphoma | 4 (1.7) | |

| T-cell prolymphocytic leukemia | 1 (0.4) | |

| Multiple myeloma | 1 (0.4) | |

| Immunodeficiency | 1 (0.4) | |

| Disease risk index | 0 | |

| Low | 35 (14.5) | |

| Intermediate | 136 (56.4) | |

| High | 46 (19.1) | |

| Very high | 16 (6.6) | |

| Not available for diagnosis | 8 (3.3) | |

| Mean Karnofsky performance status (SD) | 74.91 (31.21) | 25 |

| Conditioning regimen, No. (%) | 0 | |

| Myeloablative | 164 (68.0) | |

| Nonmyeloablative | 77 (32.0) | |

| Mean HCT Comorbidity Index (SD) | 2.15 (1.92) | 40 |

| Donor type, No. (%) | 0 | |

| Matched unrelated | 127 (52.7) | |

| Matching sibling | 114 (47.3) | |

| Graft source, No. (%) | 0 | |

| Peripheral blood | 186 (77.2) | |

| Bone marrow | 42 (17.4) | |

| Umbilical cord blood | 13 (5.4) | |

| Diagnosed with acute GVHD, No. (%) | 114 (47.3) | 21 |

| Diagnosed with chronic GVHD, No. (%) | 111 (46.1) | 0 |

| Severity of chronic GVHD, No. (%) | 0 | |

| Mild | 25 (10.4) | |

| Moderate | 60 (24.9) | |

| Severe | 23 (9.5) | |

| Disease relapse during 6-year follow-up period, No. (%) | 85 (35.3) | 0 |

| Died during 6-year follow-up period, No. (%) | 105 (43.6) | 0 |

GVHD = graft-versus-host disease; HCT = hematopoietic cell transplantation.

Table 2.

Descriptive statistics for biobehavioral symptom variablesa

| Variables | Pre-HCT (n = 241) | Day 100 post-HCT (n = 186) |

|---|---|---|

| IDAS depression symptoms (0-40), mean (SD) | 16.48 (6.47) | 16.55 (6.04) |

| PSQI sleep disruption, >5, No. (%) | 116 (48.1) | 104 (43.2) |

| PSQI sleep disruption, No. (%) | ||

| Low/none, ≤5 | 101 (41.9) | 81 (33.6) |

| Moderate, 6-9 | 63 (26.1) | 60 (24.9) |

| High, >9 | 53 (22.0) | 44 (18.3) |

| FSI fatigue severity, 0-10, mean (SD) | 3.52 (1.95) | 3.69 (1.92) |

| FSI fatigue interference, 0-10, mean (SD) | 2.49 (2.44) | 2.75 (2.36) |

FSI = Fatigue Symptom Inventory; HCT = hematopoietic cell transplantation; IDAS = Inventory of Depression and Anxiety Symptoms; PSQI = Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index.

Biobehavioral Symptoms and cGVHD

Biobehavioral symptoms did not predict cGVHD risk (Supplementary Table 2, available online). There were no interactions between the symptoms and sex or race.

Biobehavioral Symptoms and Relapse

Pre-HCT moderate sleep disruption (PSQI 6-9) predicted increased risk of relapse only when adjusting for KPS and comorbidities (hazard ratio [HR] = 1.99, 95% confidence interval [CI] = 1.02 to 3.87), whereas high sleep disruption (PSQI > 9), depression symptoms, and fatigue did not (Table 3). Post-HCT symptoms did not predict relapse risk.

Table 3.

Cox proportional hazard models with biobehavioral predictors of disease relapse up to 6 years after allogeneic HCT (n = 241)

| Primary predictor | Pre-HCT |

Day 100 post-HCT |

||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Model 1a |

Model 2b |

Model 1a |

Model 2b |

|||||||||

| No. | HR (95% CI) | P | No. | HR (95% CI) | P | No. | HR (95% CI) | P | No. | HR (95% CI) | P | |

| Depression symptoms | 221 | 1.01 (0.97 to 1.05) | .63 | 167 | 1.02 (0.98 to 1.07) | .29 | 183 | 1.03 (0.99 to 1.07) | .12 | 139 | 1.04 (0.99 to 1.09) | .15 |

| Sleep disruption, >5 | 217 | 1.18 (0.74 to 1.89) | .49 | 165 | 1.72 (0.95 to 3.12) | .08 | 185 | 1.26 (0.77 to 2.07) | .37 | 141 | 1.24 (0.68 to 2.27) | .48 |

| Sleep disruption | 217 | 165 | 185 | 141 | ||||||||

| Low/none, ≤5 | (Referent) | (Referent) | (Referent) | (Referent) | ||||||||

| Moderate, 6-9 | 1.41 (0.82 to 2.43) | .21 | 1.99 (1.02 to 3.87) | .04 | 1.27 (0.72 to 2.24) | .41 | 1.35 (0.66 to 2.78) | .41 | ||||

| High, >9 | 0.95 (0.52 to 1.74) | .88 | 1.45 (0.71 to 2.98) | .31 | 1.24 (0.67 to 2.30) | .49 | 1.15 (0.56 to 2.36) | .71 | ||||

| Fatigue severity | 216 | 1.12 (0.99 to 1.26) | .07 | 165 | 1.14 (0.98 to 1.31) | .08 | 185 | 0.99 (0.87 to 1.13) | .89 | 142 | 1.09 (0.92 to 1.29) | .33 |

| Fatigue interference | 216 | 1.03 (0.94 to 1.14) | .52 | 165 | 1.04 (0.93 to 1.16) | .50 | 185 | 1.10 (0.99 to 1.23) | .07 | 142 | 1.14 (0.99 to 1.32) | .08 |

Model 1 adjusts for age, sex, disease risk index, conditioning regimen, donor type, and graft source. CI = confidence interval; HCT = hematopoietic cell transplantation; HR = hazard ratio.

Model 2 adjusts for model 1 covariates as well as Karnofsky performance status and comorbidities.

There was an interaction between pre-HCT fatigue severity and sex, such that the association between fatigue severity and increased relapse risk was stronger for men than women (Supplementary Table 3, available online). Similarly, there was an interaction between pre-HCT fatigue interference and sex, with the association between fatigue interference and increased relapse risk stronger in men than women.

Biobehavioral Symptoms and OS

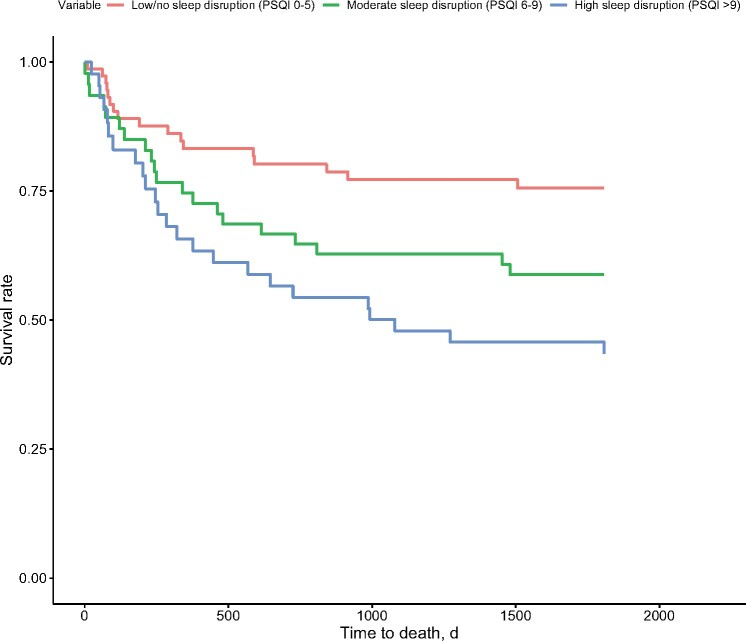

Pre-HCT sleep disruption (PSQI > 5) predicted increased risk for mortality (Table 4), and this risk was particularly pronounced for participants with high sleep disruption (PSQI > 9; Figure 1). Higher pre-HCT fatigue severity and fatigue interference also predicted increased mortality risk. Pre-HCT depression symptoms predicted increased mortality risk only when adjusting for KPS and comorbidities. In a follow-up analysis that included pre-HCT depression symptoms, high (PSQI > 9) and moderate (PSQI 6-9) sleep disruption, fatigue severity, fatigue interference, and primary covariates in a single statistical model, only high sleep disruption predicted increased risk for mortality (HR = 1.86, 95% CI = 0.99 to 3.52; P = .05). The magnitude of this association increased after also adjusting for KPS and comorbidities (HR = 2.74, 95% CI = 1.27 to 5.92; P = .01).

Table 4.

Cox proportional hazard models with biobehavioral predictors of mortality up to 6 years after allogeneic HCT (n = 241)

| Primary predictor | Pre-HCT |

Day 100 post-HCT |

||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Model 1a |

Model 2b |

Model 1a |

Model 2b |

|||||||||

| No. | HR (95% CI) | P | No. | HR (95% CI) | P | No. | HR (95% CI) | P | No. | HR (95% CI) | P | |

| Depression symptoms | 221 | 1.02 (0.99 to 1.06) | .20 | 167 | 1.05 (1.01 to 1.09) | .02 | 183 | 1.06 (1.02 to 1.10) | .006 | 139 | 1.08 (1.03 to 1.13) | .003 |

| Sleep disruption, >5 | 217 | 1.81 (1.16 to 2.80) | .008 | 165 | 2.46 (1.38 to 4.39) | .002 | 185 | 1.43 (0.86 to 2.38) | .16 | 141 | 1.79 (0.96 to 3.36) | .07 |

| Sleep disruption | 217 | 165 | 185 | 141 | ||||||||

| Low/none, ≤5 | (Referent) | (Referent) | (Referent) | (Referent) | ||||||||

| Moderate, 6-9 | 1.62 (0.98 to 2.70) | .06 | 1.97 (1.01 to 3.83) | .047 | 1.40 (0.79 to 2.49) | .24 | 1.93 (0.93 to 4.00) | .08 | ||||

| High, >9 | 2.06 (1.22 to 3.48) | .007 | 3.10 (1.63 to 5.91) | <.001 | 1.48 (0.79 to 2.76) | .22 | 1.67 (0.80 to 3.47) | .17 | ||||

| Fatigue severity | 216 | 1.14 (1.03 to 1.26) | .01 | 165 | 1.19 (1.05 to 1.34) | .006 | 185 | 1.04 (0.91 to 1.19) | .58 | 142 | 1.17 (0.99 to 1.38) | .07 |

| Fatigue interference | 216 | 1.09 (1.01 to 1.18) | .03 | 165 | 1.09 (0.99 to 1.19) | .07 | 185 | 1.21 (1.08 to 1.34) | <.001 | 142 | 1.30 (1.13 to 1.50) | <.001 |

Model 1 adjusts for age, sex, disease risk index, conditioning regimen, donor type, and graft source. CI = confidence interval; HCT = hematopoietic cell transplantation; HR = hazard ratio.

Model 2 adjusts for model 1 covariates as well as Karnofsky performance status and comorbidities.

Figure 1.

Adjusted survival time in days for patients as a function of prehematopoietic cell transplantation sleep disruption (low or none, moderate, high), covarying for patient demographic and medical characteristics. Cox regression models indicated that patients with high sleep disruption (Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index [PSQI] >9) before hematopoietic cell transplantation had shorter survival times than patients with low or no sleep disruption (PSQI ≤5).

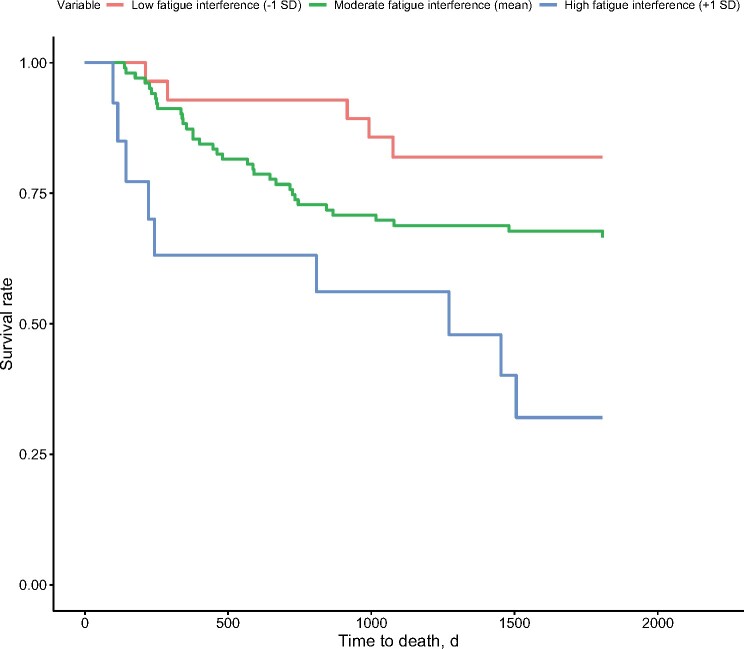

Post-HCT depression symptoms and fatigue interference predicted increased risk for mortality (Table 4; Figure 2), whereas sleep disruption did not. In a follow-up analysis that included post-HCT depression symptoms, sleep disruption (PSQI > 5), fatigue severity, fatigue interference, and primary covariates in a single statistical model, greater fatigue interference independently predicted increased risk for mortality (HR = 1.28, 95% CI = 1.10 to 1.48; P = .001). The magnitude of this association increased when adjusting for KPS and comorbidities (HR = 1.32, 95% CI = 1.05 to 1.66; P = .02).

Figure 2.

Adjusted survival time in days for patients as a function of posthematopoietic cell transplantation fatigue interference (-1 standard deviation, mean, +1 standard deviation), covarying for patient demographic and medical characteristics. Cox regression models indicated that patients with higher fatigue interference at 100 days after hematopoietic cell transplantation had shorter survival times than patients with lower fatigue interference.

There was an interaction between pre-HCT fatigue interference and sex only after adjusting for KPS and comorbidities, such that the association between fatigue interference and increased mortality risk was stronger for men than women (Supplementary Table 3, available online). There was also an interaction between post-HCT fatigue interference and sex only when adjusting for KPS and comorbidities, with the association between fatigue interference and increased mortality risk stronger in women than men.

Discussion

This study investigated 3 of the most prevalent and distressing biobehavioral symptoms experienced by HCT recipients—depression symptoms, sleep disruption, and fatigue—as predictors of cGVHD, relapse, and OS up to 6 years after HCT. As hypothesized, pre-HCT sleep disruption—particularly high sleep disruption (PSQI > 9)—predicted increased risk for mortality. Pre-HCT depression symptoms, fatigue severity, and fatigue interference also predicted increased mortality risk, although with smaller effect sizes. In a follow-up analysis that included pre-HCT symptoms in a single statistical model, only high sleep disruption (PSQI > 9) uniquely predicted mortality risk. As hypothesized, post-HCT depression symptoms and fatigue interference also predicted increased mortality risk. In a follow-up analysis that included post-HCT symptoms in a single statistical model, only fatigue interference with daily functioning uniquely predicted mortality risk.

Most previous research has focused on pre-HCT depression as a predictor of mortality following transplant, with inconsistent findings. Whereas early studies were limited by small samples and/or retrospective designs and/or did not account for relevant covariates in the analyses (24,59-66), more recent investigations have typically addressed these methodological limitations (67,68). Three out of 5 recent studies found that pre-HCT depression symptoms predicted increased mortality risk up to 5 years post-HCT (25-27, 51,69). Our findings are consistent with this research, with pre-HCT and post-HCT depression symptoms predicting mortality risk; however, in the present analyses, depression symptoms did not uniquely contribute to outcomes after accounting for sleep disruption and fatigue. It is possible that neurovegetative depression symptoms confer more risk than cognitive and affective symptoms, but this has not been specifically tested.

Although up to 56% of HCT recipients report sleep difficulties and 81% report moderate to severe fatigue (2,13,70), few studies have evaluated these symptoms in relation to clinical outcomes. To our knowledge, only 1 study investigated sleep quality as a risk factor for HCT outcomes, finding that responses to the item “I am sleeping well” did not predict relapse or survival 1 year post-HCT (53). The present study is the first to evaluate sleep disruption and fatigue in addition to depression symptoms. We found that high pre-HCT sleep disruption (PSQI > 9) and post-HCT fatigue interference with daily functioning were the most robust predictors of mortality risk. In addition, the finding for pre-HCT sleep disruption suggests a dose-response effect, with high sleep disruption (PSQI > 9) predicting greater risk than moderate sleep disruption (PSQI 6-9), relative to low or no disruption (PSQI ≤ 5). The hazard ratio for pre-HCT high sleep disturbance was also comparable in size to other commonly assessed risk factors such as smoking (51). Interestingly, associations between pre-HCT and post-HCT fatigue and increased risk of both relapse and mortality were moderated by the patients’ sex, with stronger associations for men at pre-HCT and for women at post-HCT. Because these were exploratory analyses without a priori predictions, these potential sex differences warrant investigation in future research. In addition, this analysis is the first to suggest that moderate pre-HCT sleep disruption (PSQI 6-9) is a biobehavioral risk factor for disease relapse. It was somewhat surprising that other biobehavioral symptoms were not associated with relapse risk, although there were fewer relapse (n = 85) than mortality (n = 105) events during the follow-up period, which may have limited the power to detect statistically significant associations.

The biobehavioral symptoms observed in this study may influence clinical outcomes through both behavioral and physiological pathways. For instance, prior research has indicated that depression is associated with reduced adherence to medical regimens following HCT, which could negatively impact outcomes (13). With respect to biological mediators, biobehavioral symptoms have been proposed to modulate both cellular immune recovery and inflammatory pathways known to be involved in the pathophysiology of GVHD (67). Several studies suggested that depression and sleep disruption are associated with slower leukocyte recovery and elevated circulating levels of inflammatory cytokines in HCT recipients (17,71-73); yet research that specifically examines the physiological correlates of fatigue is lacking. A growing literature also suggests that inflammatory pathways may contribute to the development of biobehavioral symptoms in HCT and other cancer populations (74-77). Therefore, the co-occurrence of symptoms observed in this study, which research has described as a symptom cluster (2,20), may be a manifestation of a common biological process such as increased inflammation. It is also possible that 1 symptom (eg, sleep disruption) could contribute to increased occurrence of the other symptoms through similar pathways and that interventions targeting 1 symptom may improve the others (21,78). In our analyses, the hazard ratio for high pre-HCT sleep disruption (PSQI < 9) was larger than the ratios for pre-HCT fatigue severity and interference, and high sleep disruption was moderately correlated with pre-HCT and post-HCT fatigue. These findings are consistent with one of the diagnostic criteria for insomnia—that sleep disruptions impair daytime functioning—and raise the question of whether pre-HCT sleep disruption plays a role in the emergence or worsening of other biobehavioral symptoms including depression and fatigue (79-81). Given the limited research on sleep in the context of HCT, the biological and behavioral sequelae of sleep disruptions are important directions for future research.

Contrary to expectations, biobehavioral symptoms did not predict the likelihood of cGVHD. These findings concur with previous studies in which depression and poor sleep did not predict cGVHD (25,53). Because cGVHD involves alloreactive donor lymphocytes that target recipient tissues, it is possible that genetic and cellular factors during the early recovery period (first 100 days) may be more predictive of cGVHD incidence, whereas biobehavioral factors may have a greater influence on the severity and/or course of cGVHD after it becomes manifest. It is also possible that biobehavioral symptoms influence cGVHD indirectly through biological mediators, such as inflammatory cytokines, which this study did not evaluate. Future research will benefit from repeated and simultaneous tracking of biobehavioral symptoms and biological mediators prior to and after clinical presentation of cGVHD.

Despite the scale of this evaluation in terms of the number of patients, several limitations should be acknowledged, including the low racial and ethnic diversity. Although representative of the patients treated in our clinic and the demographic makeup of the surrounding community, this study should be complemented by a similar evaluation in a more diverse setting. Another limitation includes the reliance on self-report measures of sleep quality. Although the PSQI is a valid and reliable measure of sleep quality that is convenient to administer in a clinical setting, it cannot be used to clinically diagnose insomnia and sleep apnea, which may underlie the observed effects. If either are chronic and untreated, they could place patients at particular risk for poor outcomes (82,83). Future research incorporating more objective sleep measures such as actigraphy and/or polysomnography will further enhance our understanding of associations between sleep quality and HCT outcomes.

Despite these limitations, this study is the first to systematically assess sleep disruption and fatigue, in addition to depression symptoms, as behavioral risk factors for HCT outcomes for up to 6 years after transplantation. These findings affirm the value of implementing more standardized assessments of patient-reported biobehavioral symptoms into routine care of HCT recipients to identify those at risk for poor outcomes. Importantly, findings also suggest potential targets for intervention to improve HCT outcomes, because these symptoms are responsive to behavioral and pharmacologic interventions in cancer populations. Cognitive Behavioral Therapy for Insomnia is the gold standard for the treatment of insomnia (Cohen d = 0.53 and 0.77) (31). Behavioral interventions, including cognitive-behavioral (84,85), mindfulness-based (86), energy conservation (87), and physical activity (d = 0.53) (88,89) approaches, show promise for fatigue. Erythropoietin (d = -0.52) and methylphenidate (d = -0.36) also reduce fatigue in cancer populations, including HCT, but safety concerns might limit their usefulness (90). Behavioral interventions, including cognitive-behavioral (d = -1.11) (28,91) and mindfulness-based approaches (d = -0.77 and -0.93) (92-94), are effective for treating depression. Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors and tetracyclic antidepressants also improve depressive symptoms (relative risk = 1.56) (95). Randomized controlled trials have also demonstrated that mind-body interventions (eg, tai chi, yoga) can improve these symptoms and decrease inflammatory signaling in cancer populations (96,97). Many of these interventions are being adapted for digital platforms for patients who cannot access professional treatment (eg, www.va.gov). These behavioral interventions may also be effective for HCT recipients, may help patients avoid additional medications and associated side effects, and can be readily incorporated into future clinical care and investigations.

Funding

This work was supported by the National Institutes of Health (K07CA136966, R21CA133343, and K01AG065485); Forward Lymphoma Foundation; UW Carbone Cancer Center; Don Anderson Fund for GVHD Research; American Cancer Society; and UCLA Cousins Center for Psychoneuroimmunology.

Notes

Role of the funders: Funding sources had no involvement in the study design, collection, analysis, or interpretation, or the decision to submit the manuscript.

Disclosures: The authors report no conflicts of interest.

Author contributions: KER: conceptualization, data curation, formal analysis, visualization, writing. JEC: conceptualization, writing. CLC: conceptualization, writing. MBJ: investigation, data curation, writing. ATB: data curation, formal analysis, writing. PJR: formal analysis, visualization, writing. PH: conceptualization, writing. ESC: conceptualization, funding acquisition, investigation, data curation, writing.

Prior presentations: The findings were previously presented at the Annual Scientific Meeting of the American Psychosomatic Society in Louisville, Kentucky on March 8, 2018, and the Transplantation and Cellular Therapy (TCT) Meetings of ASTCT and CIBMTR Digital Experience on February 4, 2021.

Data Availability

Data that support the findings of this study are available upon request from the corresponding author but are not publicly available due to privacy or ethical restrictions.

Supplementary Material

References

- 1. D’Souza A, Fretham C.. Current Use and Outcome of Hematopoietic Stem Cell Transplantation: CIBMTR Summary Slides. 2017. http://www.cibmtr.org.

- 2. Bevans MF, Mitchell SA, Marden S.. The symptom experience in the first 100 days following allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplantation (HSCT). Support Care Cancer. 2008;16(11):1243–1254. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Pidala J, Anasetti C, Jim H.. Quality of life after allogeneic hematopoietic cell transplantation. Blood. 2009;114(1):7–19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Copelan EA. Hematopoietic stem-cell transplantation. N Engl J Med. 2006;354(17):1813–1826. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Syrjala KL, Martin PJ, Lee SJ.. Delivering care to long-term adult survivors of hematopoietic cell transplantation. J Clin Oncol. 2012;30(30):3746–3751. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Baker KS, Gurney JG, Ness KK, et al. Late effects in survivors of chronic myeloid leukemia treated with hematopoietic cell transplantation: results from the Bone Marrow Transplant Survivor Study. Blood. 2004;104(6):1898–1906. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Duell T, Van Lint MT, Ljungman P, et al. Health and functional status of long-term survivors of bone marrow transplantation. Ann Intern Med. 1997;126(3):184–192. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Ferrara JLM, Reddy P.. Pathophysiology of graft-versus-host disease. Semin Hematol. 2006;43(1):3–10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Jagasia MH, Greinix HT, Arora M, et al. National Institutes of Health Consensus Development Project on criteria for clinical trials in chronic graft-versus-host disease: I. The 2014 Diagnosis and Staging Working Group Report. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant. 2015;21(3):389–401.e1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Socié G, Stone JV, Wingard JR, et al. Long-term survival and late deaths after allogeneic bone marrow transplant. 1999;341(1):14–21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Syrjala KL, Chapko MK, Vitaliano PP, Cummings C, Sullivan KM.. Recovery after allogeneic marrow transplantation: prospective study of predictors of long-term physical and psychosocial functioning. Bone Marrow Transplant. 1993;11(4):319–327. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Arai S, Arora M, Wang T, et al. Increasing incidence of chronic graft-versus-host disease in allogeneic transplantation: a report from the center for international blood and marrow transplant research. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant. 2015;21(2):266–274. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Artherholt SB, Hong F, Berry DL, Fann JR.. Risk factors for depression in patients undergoing hematopoietic cell transplantation. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant. 2014;20(7):946–950. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. El-Jawahri AR, Traeger LN, Kuzmuk K, et al. Quality of life and mood of patients and family caregivers during hospitalization for hematopoietic stem cell transplantation. Cancer. 2015;121(6):951–959. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. D’Souza A, Millard H, Knight J, et al. Prevalence of self-reported sleep dysfunction before allogeneic hematopoietic cell transplantation. Bone Marrow Transplant. 2018;53(8):1079–1082. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Jim HSL, Evans B, Jeong JM, et al. Sleep disruption in hematopoietic cell transplantation recipients: prevalence, severity, and clinical management. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant. 2014;20(10):1465–1484. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Nelson AM, Coe CL, Juckett MB, et al. Sleep quality following hematopoietic stem cell transplantation: longitudinal trajectories and biobehavioral correlates. Bone Marrow Transplant. 2014;49(11):1405–1411. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Rischer J, Scherwath A, Zander AR, Koch U, Schulz-Kindermann F.. Sleep disturbances and emotional distress in the acute course of hematopoietic stem cell transplantation. Bone Marrow Transplant. 2009;44(2):121–128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Hacker ED, Ferrans C, Verlen E, et al. Fatigue and physical activity in patients undergoing hematopoietic stem cell transplant. Oncol Nurs Forum. 2006;33(3):614–624. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lynch Kelly D, Dickinson K, Hsiao C, et al. Biological basis for the clustering of symptoms. Semin Oncol Nurs. 2016;32(4):351–360. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Bower JE. Behavioral symptoms in patients with breast cancer and survivors. J Clin Oncol. 2008;26(5):768–777. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Groenvold M, Petersen MA, Idler E, Bjorner JB, Fayers PM, Mouridsen HT.. Psychological distress and fatigue predicted recurrence and survival in primary breast cancer patients. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2007;105(2):209–219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Jacobsen PB, Hann DM, Azzarello LM, Horton J, Balducci L, Lyman GH.. Fatigue in women receiving adjuvant chemotherapy for breast cancer: characteristics, course, and correlates. J Pain Symptom Manage. 1999;18(4):233–242. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Colón EA, Callies AL, Popkin MK, McGlave PB.. Depressed mood and other variables related to bone marrow transplantation survival in acute leukemia. Psychosomatics. 1991;32(4):420–425. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. El-Jawahri A, Chen Y, Bin Brazauskas R, et al. Impact of pre-transplant depression on outcomes of allogeneic and autologous hematopoietic stem cell transplantation. Cancer. 2017;123(10):1828–1838. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Grulke N, Larbig W, Kächele H, Bailer H.. Pre-transplant depression as risk factor for survival of patients undergoing allogeneic haematopoietic stem cell transplantation. Psychooncology. 2008;17(5):480–487. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Sorror ML, Maris MB, Storb R, et al. Hematopoietic cell transplantation (HCT)-specific comorbidity index: a new tool for risk assessment before allogeneic HCT. Blood. 2005;106(8):2912–2919. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Peoples AR, Garland SN, Pigeon WR, et al. Cognitive behavioral therapy for insomnia reduces depression in cancer survivors. J Clin Sleep Med. 2019;15(01):129–137. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Irwin MR, Olmstead R, Carrillo C, et al. Tai Chi Chih compared with cognitive behavioral therapy for the treatment of insomnia in survivors of breast cancer: a randomized, partially blinded, noninferiority trial. J Clin Oncol. 2017;35(23):2656–2665. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Garland SN, Carlson LE, Stephens AJ, Antle MC, Samuels C, Campbell TS.. Mindfulness-based stress reduction compared with cognitive behavioral therapy for the treatment of insomnia comorbid with cancer: a randomized, partially blinded, noninferiority trial. J Clin Oncol. 2014;32(5):449–457. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Johnson JA, Rash JA, Campbell TS, et al. A systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials of cognitive behavior therapy for insomnia (CBT-I) in cancer survivors. Sleep Med Rev. 2016;27:20–28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Bishop MM, Beaumont JL, Hahn EA, et al. Late effects of cancer and hematopoietic stem-cell transplantation on spouses or partners compared with survivors and survivor-matched controls. J Clin Oncol. 2007;25(11):1403–1411. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Hjermstad MJ, Knobel H, Brinch L, et al. Quality of life: a prospective study of health-related quality of life, fatigue, anxiety and depression 3-5 years after stem cell transplantation. Bone Marrow Transplant. 2004;34(3):257–266. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Mosher CE, Redd WH, Rini CM, Burkhalter JE, Duhamel KN.. Physical, psychological, and social sequelae following hematopoietic stem cell transplantation: a review of the literature. Psychooncology. 2009;18(2):113–127. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Syrjala KL, Langer SL, Abrams JR, Storer BE, Martin PJ.. Late effects of hematopoietic cell transplantation among 10-year adult survivors compared with case-matched controls. J Clin Oncol. 2005;23(27):6596–6606. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Larson AG, Morris KJ, Juckett MB, Coe CL, Broman AT, Costanzo ES.. Mindfulness, experiential avoidance, and recovery from hematopoietic stem cell transplantation. Ann Behav Med. 2019;53(10):886–895. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Leeson LA, Nelson AM, Rathouz PJ, et al. Spirituality and the recovery of quality of life following hematopoietic stem cell transplantation HHS public access author manuscript. Health Psychol. 2015;34(9):920–928. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Nelson AM, Juckett MB, Coe CL, Costanzo ES.. Illness perceptions predict health practices and mental health following hematopoietic stem cell transplantation. Psychooncology. 2019;28(6):1252–1260. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Watson D, O’Hara MW, Simms LJ, et al. Development and validation of the Inventory of Depression and Anxiety Symptoms (IDAS). Psychol Assess. 2007;19(3):253–268. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Watson D, O’Hara MW, Chmielewski M, et al. Further validation of the IDAS: evidence of convergent, discriminant, criterion, and incremental validity. Psychol Assess. 2008;20(3):248–259. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Carpenter JS, Andrykowski MA.. Psychometric evaluation of the Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index. J Psychosom Res. 1998;45(1):5–13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Buysse DJ, Reynolds CF, Monk TH, Berman SR, Kupfer DJ.. The Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index: a new instrument for psychiatric practice and research. Psychiatry Res. 1989;28(2):193–213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Carroll JE, Rentscher KE, Cole SW, et al. Sleep disturbances and inflammatory gene expression among pregnant women: differential responses by race. Brain Behav Immun. 2020;88:654–660. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Sedov ID, Cameron EE, Madigan S, Tomfohr-Madsen LM.. Sleep quality during pregnancy: a meta-analysis. Sleep Med Rev. 2018;38:168–176. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Hann DM, Jacobsen PB, Azzarello LM, et al. Measurement of fatigue in cancer patients: development and validation of the Fatigue Symptom Inventory. Qual Life Res. 1998;7(4):301–310. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Hann DM, Denniston MM, Baker F.. Measurement of fatigue in cancer patients: further validation of the fatigue symptom inventory. Qual Life Res. 2000;9(7):847–854. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Donovan KA, Jacobsen PB, Andrykowski MA, et al. Course of fatigue in women receiving chemotherapy and/or radiotherapy for early stage breast cancer. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2004;28(4):373–380. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Donovan KA, Jacobsen PB.. The Fatigue Symptom Inventory: a systematic review of its psychometric properties. Support Care Cancer. 2010;19(2):169–185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Armand P, Kim HT, Logan BR, et al. Validation and refinement of the Disease Risk Index for allogeneic stem cell transplantation. Blood. 2014;123(23):3664–3671. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Brown JR, Kim HT, Li S, et al. Predictors of improved progression-free survival after nonmyeloablative allogeneic stem cell transplantation for advanced chronic lymphocytic leukemia. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant. 2006;12(10):1056–1064. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Chang G, Orav EJ, Tong MY, Antin JH.. Predictors of 1-year survival assessed at the time of bone marrow transplantation. Psychosomatics. 2004;45(5):378–385. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Arora M, Nagaraj S, Wagner JE, et al. Chronic graft-versus-host disease (cGVHD) following unrelated donor hematopoietic stem cell transplantation (HSCT): higher response rate in recipients of unrelated donor (URD) umbilical cord blood (UCB). Biol Blood Marrow Transplant. 2007;13(10):1145–1152. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. D’Souza A, Millard HR, Knight J, et al. Patient-reported sleep quality at baseline correlates with 1-year survival after allogeneic hematopoietic cell transplantation in adults. Blood. 2017;130(suppl 1):3447–3447. [Google Scholar]

- 54. Karnofsky DA, Burchenal JH. The clinical evaluation of chemotherapeutic agents in cancer. In: MacCleod CM, ed. Evaluation of Chemotherapeutic Agents. New York: Columbia University Press; 1949:191–205. [Google Scholar]

- 55. Sorror M, Storer B, Sandmaier BM, et al. Hematopoietic cell transplantation-comorbidity index and Karnofsky performance status are independent predictors of morbidity and mortality after allogeneic nonmyeloablative hematopoietic cell transplantation. Cancer. 2008;112(9):1992–2001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Sorror ML. How I assess comorbidities before hematopoietic cell transplantation. Blood. 2013;121(15):2854–2863. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Filipovich AH, Weisdorf D, Pavletic S, et al. National Institutes of Health Consensus Development Project on criteria for clinical trials in chronic graft-versus-host disease: I. Diagnosis and Staging Working Group Report. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant. 2005;11(12):945–956. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Grambsch PM, Therneau TM.. Proportional hazards tests and diagnostics based on weighted residuals. Biometrika. 1994;81(3):515–526. [Google Scholar]

- 59. Andrykowski MA, Brady MJ, Henslee-Downey PJ.. Psychosocial factors predictive of survival after allogeneic bone marrow transplantation for leukemia. Psychosom Med. 1994;56(5):432–439. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Broers S, Hengeveld MW, Kaptein AA, Le Cessie S, Van De Loo F, De Vries T.. Are pretransplant psychological variables related to survival after bone marrow transplantation? A prospective study of 123 consecutive patients. J Psychosom Res. 1998;45(4):341–351. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Hoodin F, Kalbfleisch KR, Thornton J, Ratanatharathorn V.. Psychosocial influences on 305 adults’ survival after bone marrow transplantation: depression, smoking, and behavioral self-regulation. J Psychosom Res. 2004;57(2):145–154. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Jenkins PL, Lester H, Alexander J, Whittaker JA.. Prospective study of psychosocial morbidity in adult bone marrow transplant recipients. Psychosomatics. 1994;35(4):361–367. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63. Loberiza FR, Rizzo JD, Bredeson CN, et al. Association of depressive syndrome and early deaths among patients after stem-cell transplantation for malignant diseases. J Clin Oncol. 2002;20(8):2118–2126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64. Murphy KC, Jenkins PL, Whittaker JA.. Psychosocial morbidity and survival in adult bone marrow transplant recipients-a follow-up study. Bone Marrow Transplant. 1996;18(1):199–201. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/8832015. Accessed April 3, 2020. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65. Pereira DB, Christian LM, Patidar S, et al. Spiritual absence and 1-year mortality after hematopoietic stem cell transplant. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant. 2010;16(8):1171–1179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66. Prieto JM, Atala J, Blanch J, et al. Role of depression as a predictor of mortality among cancer patients after stem-cell transplantation. J Clin Oncol. 2005;23(25):6063–6071. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67. Costanzo ES, Juckett MB, Coe CL.. Biobehavioral influences on recovery following hematopoietic stem cell transplantation. Brain Behav Immun. 2013;30(suppl):S68–74. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68. Hoodin F, Uberti JP, Lynch TJ, Steele P, Ratanatharathorn V.. Do negative or positive emotions differentially impact mortality after adult stem cell transplant? Bone Marrow Transplant. 2006;38(4):255–264. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69. Pillay B, Lee SJ, Katona L, Burney S, Avery S.. Psychosocial factors predicting survival after allogeneic stem cell transplant. Support Care Cancer. 2014;22(9):2547–2555. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70. Nelson AM, Jim HSL, Small BJ, et al. Sleep disruption among cancer patients following autologous hematopoietic cell transplantation. Bone Marrow Transplant. 2018;53(3):307–314. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71. McGregor BA, Syrjala KL, Dolan ED, Langer SL, Redman M.. The effect of pre-transplant distress on immune reconstitution among adult autologous hematopoietic cell transplantation patients. Brain Behav Immun. 2013;30(suppl):S142-S148. doi:10.1016/j.bbi.2012.07.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72. Tavakoli-Ardakani M, Mehrpooya M, Mehdizadeh M, Hajifathali A, Abdolahi A.. Association between interlukin-6 (il-6), interlukin-10 (IL-10) and depression in patients undergoing hematopoietic stem cell transplantation. Int J Hematol Stem Cell Res. 2015;9(2):80–87. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73. Boland E, Eiser C, Ezaydi Y, Greenfield DM, Ahmedzai SH, Snowden JA.. Living with advanced but stable multiple myeloma: a study of the symptom burden and cumulative effects of disease and intensive (hematopoietic stem cell transplant-based) treatment on health-related quality of life. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2013;46(5):671–680. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74. Wang XS, Shi Q, Williams LA, et al. Serum interleukin-6 predicts the development of multiple symptoms at nadir of allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplantation. Cancer. 2008;113(8):2102–2109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75. Bower JE, Ganz PA, Irwin MR, Kwan L, Breen EC, Cole SW.. Inflammation and behavioral symptoms after breast cancer treatment: do fatigue, depression, and sleep disturbance share a common underlying mechanism? J Clin Oncol. 2011;29(26):3517–3522. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76. Miller AH, Ancoli-Israel S, Bower JE, Capuron L, Irwin MR.. Neuroendocrine-immune mechanisms of behavioral comorbidities in patients with cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2008;26(6):971–982. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77. Lee BN, Dantzer R, Langley KE, et al. A cytokine-based neuroimmunologic mechanism of cancer-related symptoms. Neuroimmunomodulation. 2004;11(5):279–292. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78. Miaskowski C, Dodd M, Lee K.. Symptom clusters: the new frontier in symptom management research. J Natl Cancer Inst Monographs. 2004;2004(32):17–21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79. Garland SN, Mahon K, Irwin MR.. Integrative approaches for sleep health in cancer survivors. Cancer J. 2019;25(5):337–342. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80. Irwin MR. Depression and insomnia in cancer: prevalence, risk factors, and effects on cancer outcomes. Curr Psychiatry Rep. 2013;15(11):404. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81. Irwin MR, Olmstead RE, Ganz PA, Haque R.. Sleep disturbance, inflammation and depression risk in cancer survivors. Brain Behav Immun. 2013;30(suppl):S58-S67. doi :10.1016/j.bbi.2012.05.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82. Palesh O, Aldridge-Gerry A, Zeitzer JM, et al. Actigraphy-measured sleep disruption as a predictor of survival among women with advanced breast cancer. Sleep. 2014;37(5):837–842. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83. Huang HY, Lin SW, Chuang LP, et al. Severe OSA associated with higher risk of mortality in stage III and IV lung cancer. J Clin Sleep Med. 2020;16(7):1091–1098. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84. Poort H, Peters MEWJ, van der Graaf WTA, et al. Cognitive behavioral therapy or graded exercise therapy compared with usual care for severe fatigue in patients with advanced cancer during treatment: a randomized controlled trial. Ann Oncol. 2020;31(1):115–122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85. Abrahams HJG, Gielissen MFM, Donders RRT, et al. The efficacy of internet-based cognitive behavioral therapy for severely fatigued survivors of breast cancer compared with care as usual: a randomized controlled trial. Cancer. 2017;123(19):3825–3834. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86. Lengacher CA, Reich RR, Post-White J, et al. Mindfulness based stress reduction in post-treatment breast cancer patients: an examination of symptoms and symptom clusters. J Behav Med. 2012;35(1):86–94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87. Barsevick AM, Dudley W, Beck S, Sweeney C, Whitmer K, Nail L.. A randomized clinical trial of energy conservation for patients with cancer-related fatigue. Cancer. 2004;100(6):1302–1310. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88. van Haren IEPM, Timmerman H, Potting CM, Blijlevens NMA, Staal JB, Nijhuis-van der Sanden MWG.. Physical exercise for patients undergoing hematopoietic stem cell transplantation: systematic review and meta-analyses of randomized controlled trials. Phys Ther. 2013;93(4):514–528. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89. Mishra SI, Scherer RW, Snyder C, Geigle PM, Berlanstein DR, Topaloglu O.. Exercise interventions on health-related quality of life for people with cancer during active treatment. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2012;(8):CD008465. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90. Tomlinson D, Robinson PD, Oberoi S, et al. Pharmacologic interventions for fatigue in cancer and transplantation: a meta-analysis. Curr Oncol. 2018;25(2):e152–e167. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91. Ye M, Du K, Zhou J, et al. A meta-analysis of the efficacy of cognitive behavior therapy on quality of life and psychological health of breast cancer survivors and patients. Psychooncology. 2018;27(7):1695–1703. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92. Li H, Wu J, Ni Q, Zhang J, Wang Y, He G.. Systematic review and meta-analysis of effectiveness of acceptance and commitment therapy in patients with breast cancer. Nurs Res. 2021. doi:10.1097/NNR.0000000000000499. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93. Li Z, Li Y, Guo L, Li M, Yang K.. Effectiveness of acceptance and commitment therapy for mental illness in cancer patients: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomised controlled trials. Int J Clin Pract. 2021;00(e13982):1-10. doi:10.1111/ijcp.13982. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94. Zhao C, Lai L, Zhang L, et al. The effects of acceptance and commitment therapy on the psychological and physical outcomes among cancer patients: a meta-analysis with trial sequential analysis. J Psychosom Res. 2021;140(110304):1-10. doi:10.1016/j.jpsychores.2020.110304 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95. Laoutidis ZG, Mathiak K.. Antidepressants in the treatment of depression/depressive symptoms in cancer patients: a systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Psychiatry. 2013;13(1):140. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96. Carlson LE, Zelinski E, Toivonen K, et al. Mind-body therapies in cancer: what is the latest evidence? Curr Oncol Rep. 2017;19(10):1–11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97. Bower JE, Irwin MR.. Mind-body therapies and control of inflammatory biology: a descriptive review. Brain Behav Immun. 2016;51:1–11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

Data that support the findings of this study are available upon request from the corresponding author but are not publicly available due to privacy or ethical restrictions.