Summary

Leaf angle is one of the key factors that determines rice plant architecture. However, the improvement of leaf angle erectness is often accompanied by unfavourable changes in other traits, especially grain size reduction. In this study, we identified the pow1 ( put on weight 1 ) mutant that leads to increased grain size and leaf angle, typical brassinosteroid (BR)‐related phenotypes caused by excessive cell proliferation and cell expansion. We show that modulation of the BR biosynthesis genes OsDWARF4 (D4) and D11 and the BR signalling gene D61 could rescue the phenotype of leaf angle but not grain size in the pow1 mutant. We further demonstrated that POW1 functions in grain size regulation by repressing the transactivation activity of the interacting protein TAF2, a highly conserved member of the TFIID transcription initiation complex. Down‐regulation of TAF2 rescued the enlarged grain size of pow1 but had little effect on the increased leaf angle phenotype of the mutant. The separable functions of the POW1‐TAF2 and POW1‐BR modules in grain size and leaf angle control provide a promising strategy for designing varieties with compact plant architecture and increased grain size, thus promoting high‐yield breeding in rice.

Keywords: rice, POW1, TAF2, grain size, leaf angle, brassinosteroid.

Introduction

Rice is one of the most important food crops worldwide, and increasing grain yield remains the major challenge for most rice growing areas. The grain yield of rice is determined by three major factors: number of panicles per unit area, number of filled grains per panicle, and grain weight. To date, extensive attention has been given to grain size because it is a major trait that determines grain weight and thus final yield in cereal crops, and it is one of the major targets to be selected during domestication and breeding. Grain size is specified by three components, including length, width and thickness, and many genes or QTLs have recently been identified for their function in grain size regulation (Li et al., 2018). These regulators could be classified into multiple pathways, including mitogen‐activated protein kinase signalling, ubiquitin‐mediated degradation, G protein signalling, phytohormone signalling and transcriptional regulation, and all these pathways control grain size by ultimately affecting the same cellular processes, namely, cell proliferation and/or cell expansion in the spikelet hull (Li et al., 2018). Undoubtedly, the identification of favourable alleles related to grain size provides valuable gene resources for the rational design of high‐yield rice varieties.

As another key determinant of rice grain yield, the number of panicles per unit area is affected by the plant tillering ability and planting density, and the latter largely depends on the plant architecture. Plant architecture is determined by multiple factors, including the leaf angle, an important agronomic trait mainly affected by BR (Tong and Chu, 2018). An erect leaf angle is beneficial for a higher plant density and more light capture for photosynthesis, which would thus result in a grain yield increase (Sakamoto et al., 2006). To date, studies on BR have exposed the double‐faced function of the phytohormone in plant development, that is, a compact stature caused by BR deficiency is always accompanied by a small grain size, such as in d11, d2, brd1, dlt, and d61 mutants (Hong et al., 2002,2003; Mori et al., 2002; Tanabe et al., 2005; Tong et al., 2009; Yamamuro et al., 2000), while an enlarged grain size resulting from an excessive amount of BR often develops along with a loose stature, such as that observed for OsBZR1‐OE, GSK2‐RNAi and D11‐OE transgenic plants (Tong et al., 2012; Zhu et al., 2015). Fortunately, exceptions have been observed for several cases. For example, mutation of D4 results in plants with erect leaves without grain size change because D4 only contributes additional levels of bioactive BR synthesis required for normal leaf inclination and not for reproductive development (Sakamoto et al., 2006), and transgenic plants with a slightly decreased OsBRI1 expression level exhibit a reduced leaf angle and unchanged grain size (Morinaka et al., 2006). Although grain size reduction was avoided successfully in these studies during plant architecture modification, the question arises as to whether we could raise rice plants in which both a reduced leaf angle and an increased grain size favourably developed.

Plant organs all achieve their final size and shape via common paths of cell division and cell expansion. Therefore, numerous reports have focused on identifying the ultimate regulation of the genes related to these cellular processes. TAFs (TATA‐box binding protein‐associated factors), as components of the TFIID complex critical for eukaryotic gene transcription (Gupta et al., 2016; Nogales et al., 2017), are reported to be essential for cell cycle progression. A TS mutation in CCG1/TAF1 in hamster cells provoked G1/S arrest (Sekiguchi et al., 1991), and TAF9 inactivation in chicken DT40 cells could cause cell cycle arrest and apoptosis (Chen and Manley, 2000). Mouse cells that lacked TAF10 were found to be blocked in the G1/G0 phase and underwent apoptosis (Metzger et al., 1999), and a subset of TAF4b‐target genes were preferentially expressed in embryonic stem cells and involved in cell cycle control (Bahat et al., 2013). Studies have also indicated that TAFs can interact with specific transcription factors (Reeves and Hahn, 2005; Garbett et al., 2007), transcription activators (Asahara et al., 2001; Rojo Niersbach et al., 1999) and components involved in epigenetic modification (Jacobson et al., 2000; Lindner et al., 2013). Although TAFs are categorized as general transcription factors, studies in Arabidopsis have revealed their functions in specific plant developmental processes, such as light signalling (Bertrand et al., 2005), flowering time (Eom et al., 2018), pollen tube growth (Lago et al., 2005), meristem activity and leaf development (Tamada et al., 2007). Nevertheless, more studies are required to fully expand our knowledge on the function of TAFs in rice.

In this study, we characterized the rice mutant pow1, which has increased grain size and leaf angle. Our results indicate that POW1 functions in grain size regulation by repressing the transactivation activity of the interacting protein TAF2, a highly conserved member of the TFIID complex. Loss of POW1 function also results in transcriptional suppression of BR biosynthesis genes, and POW1 appears to regulate leaf angle formation by affecting BR homeostasis. The separable functions of POW1 in grain size and leaf angle control provide a novel strategy for designing rice plants in which both traits could be favourably developed.

Results

Rice mutant pow1 shows increased grain size and leaf angle

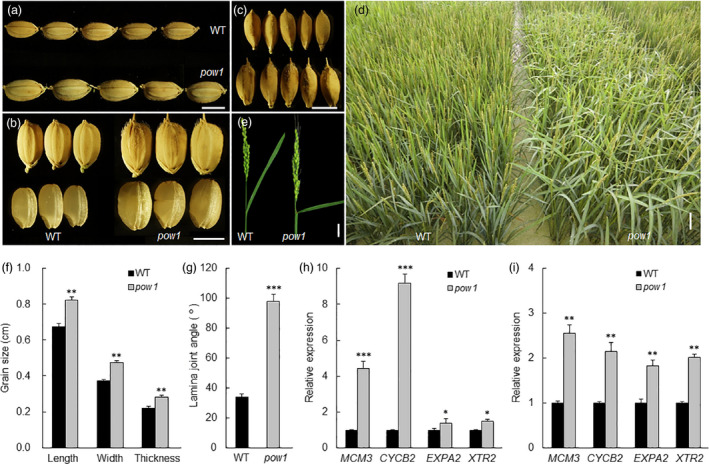

By screening the NaN3‐mutagenized M2 library in the background of the japonica rice cultivar KY131, we isolated a mutant with markedly increased grain length, width and thickness compared to that of the wild type (WT, Figure 1a–c). The increase could reach approximately 20.0% for grain length, 23.2% for grain width and 23.7% for grain thickness (Figure 1f), and the mutant was then designated pow1 ( put on weight 1 ). Planting of the M3 population indicated that pow1 displayed a loose plant architecture (Figure 1d), as featured by the nearly evenly extended flag leaf (Figure 1e). Detailed observations indicated that the leaf angle of pow1 was approximately 98°, whereas that of the WT was approximately 34° (Figure 1e,g). In addition, pow1 also showed an overall expanded size of plant organs, including the panicle, culm, leaf and all reproductive tissues (Figure S1), thus indicating the fundamental role of POW1 during rice development.

Figure 1.

Phenotypic analysis of the pow1 mutant. (a–c) Grain size comparison between pow1 and WT. Bars = 5 mm. (d) Population morphology of pow1 and WT. Indicating randomly extended leaves of the mutant population. Bar = 10 cm. (e) Leaf angle phenotype of the main panicle of pow1 and WT. Bar = 3 cm. (f,g) Comparison of grain size (f) and leaf angle (g) between pow1 and WT. Data are means ± SE (n = 30). **: p < 0.01 and ***: p < 0.001 (Student’s t test). (h,i) Expression analysis of cell division markers MCM3 and CYCB2 and cell expansion makers EXPA2 and XTR2 in young inflorescences of about 2 mm long (h) and lamina joints of flag leaves of 2‐month‐old field grown plants (i) of pow1 and WT. The transcript levels were normalized against WT, which was set to 1. Data are means ± SE (n = 3). *: p < 0.05 and ***: p < 0.001 (Student’s t test).

Scanning electron microscopy (SEM) observations indicated that the outer epidermal cells in the central region of the lemma in pow1 were longer and wider than those in the WT (Figure S2a), and the increased size in the two dimensions was also confirmed by the comparison of the inner epidermal cells between pow1 and WT plants (Figure S2b,c). The increases cell size in terms of length (17.9%) and width (18.8%) was less than those of the grain size (Figure 1f), suggesting that POW1 affects cell expansion as well as cell division during grain development.

The effects of POW1 on the cellular processes of cell division and cell expansion were further observed for the enlarged leaf angle of the mutant. We found that before the leaf angle formed, no size difference could be observed for cells in the adaxial side of the lamina joint between pow1 and WT plants, whereas the number of cell layers from the vascular bundle of xylem to the margin was clearly greater in the pow1 (6 ˜ 7) plants than the WT (3 ˜ 4) (Figure S3a,c), indicating the involvement of POW1 in cell division. During the formation of the leaf angle, the number of cell layers on the adaxial side of the lamina joint increased in both the pow1 (8 ˜ 10) and WT (6 ˜ 7) plants (Figure S3b,d). Although cell growth was observed for both the WT and pow1 during this stage, the increase in cell size was much more obvious in pow1 than in the WT (Figure S3), suggesting that POW1 also functions in cell expansion.

An investigation of the expression of genes involved in basic cellular processes indicated that in both young inflorescences and lamina joints, pow1 exhibited much higher expression levels of the cell division marker genes MCM3 and CYCB2 and the cell expansion marker genes EXPA2 and XTR2 (Duan et al., 2012; Jiang et al., 2012; Figure 1h–i). The increase in expression level was more significant for cell division genes in the young inflorescence and cell expansion genes in the lamina joint (Figure 1h–i). These results are consistent with the phenotypic observations that POW1 functions in grain size and leaf angle development by ultimately affecting both cell division and cell expansion.

POW1 encodes a protein of unknown function

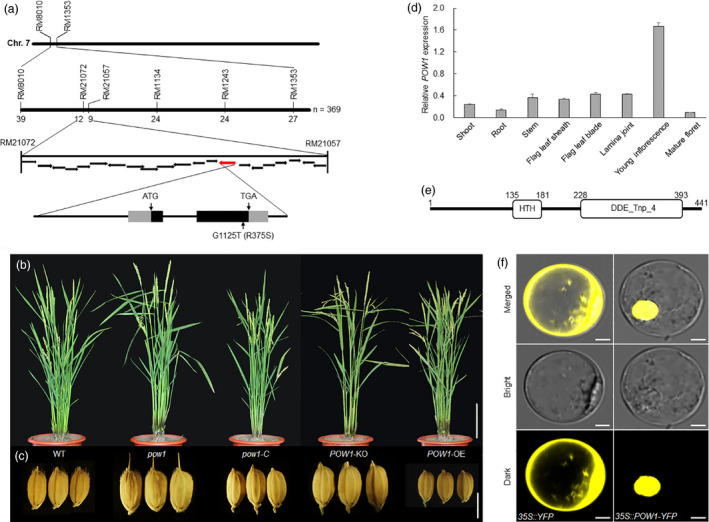

To understand the molecular function of POW1, we performed map‐based cloning to isolate the causal gene. Crossing of pow1 with the WT yielded an F2 population, in which the segregation ratio of the WT and large grain phenotype was 3:1 (355:125; χ2 = 0.278 < χ2 0.05,1 = 3.841; 0.5 > p > 0.1). This result suggests that the pow1 mutant phenotype is caused by the recessive mutation of a single locus. By using 20 bulked WT and mutant plants from the F2 population between pow1 and Kasalath (indica), the candidate locus was directly mapped to the short arm of chromosome 7 between markers RM8010 and RM1353 (Figure 2a). Further analysis of 369 F2 individuals with a mutant phenotype narrowed down the target gene to within a 181‐kb region between markers RM21072 and RM21057 (Figure 2a). After sequencing the fine‐mapped region, we found that a single mutation from G to T occurred in pow1 in the annotated gene LOC_Os07g07880 (http://rice.plantbiology.msu.edu/), which caused an amino acid change from arginine to serine (Figure 2a).

Figure 2.

Map‐based Cloning of POW1. (a) Identification of the POW1 candidate. Indicating one G–T point mutation occurred in LOC_Os07g07880 in the mutant, which results in an amino acid change from Arg to Ser. (b,c) Phenotypes of whole plant and grain size of pow1, WT, complemented T0 line (pow1‐C), POW1 knockout (POW1‐KO), and POW1 overexpression (POW1‐OE). Bars = 20 cm (b) and 5 mm (c). (d) Expression analysis of POW1 in various plant tissues. Actin was used as the internal control. Data are means ± SD (n = 3). (e) Protein structure of POW1. (f) Subcellular localization of POW1. Bars = 10 μm.

To verify that LOC_Os07g07880 is actually POW1, genomic DNA 2.2 kb upstream of ATG and 948 bp downstream of TGA were amplified from the WT and transformed into pow1. We found the overall phenotypes of all 38 T0 transgenic plants, including the grain size and leaf angle, resembled that of the WT (Figure 2b,c and Figure S4). In addition, we tried to knock out the LOC_Os07g07880 locus in the KY131 background using the CRISPR/Cas9 plant genome editing system. By specifically editing the target site near the start codon, we obtained a series of transgenic plants with diverse insertions or deletions in the coding region and selected one representative line for phenotypic analysis (Figure S4a). We found that the POW1‐KO plants displayed enlarged grain sizes and leaf angles that were completely consistent with those of the WT plants (Figure 2b,c and Figure S4c,d). Taken together, these results clearly demonstrate that the pow1 phenotypes are caused by the point mutation in LOC_Os07g07880.

To further evaluate the function of POW1 in grain size and leaf angle development, we created POW1‐overexpressing (POW1‐OE) transgenic plants in the KY131 background (Figure S4b). Compared with the comprehensively expanded plant organs of the pow1 mutant, we found that the overall appearance of the POW1‐OE plant, including plant height, heading date and leaf angle, was similar to that of the WT (Figure 2b and Figure S4d). The only exception was that the grain size of POW1‐OE was significantly reduced (Figure 2c), with the grain length and grain width only approximately 70% of that of the WT (Figure S4c). Taken together, these results indicate that POW1 is a negative grain size regulator.

POW1 is ubiquitously expressed in all tissues, including the embryo, root, stem, inflorescence, flag leaf and lamina joint (Figure 2d), which fits well with the expanded size of all organs in the mutant (Figure 1a–e and Figure S1). The highest expression of POW1 was observed in young inflorescences, and the expression level of the gene decreased sharply in mature florets (Figure 2d). This result suggests that POW1 plays a critical role in early inflorescence development.

POW1 is predicted to encode a homeodomain‐like protein with a putative helix‐turn‐helix DNA binding structure and a DDE domain (Figure 2e; Yuan and Wessler, 2011). The rice genome contains 35 putative PIF/Harbinger class transposases, with POW1 being the closest rice homolog of Arabidopsis ALP1 (Figure S5). Although POW1 appeared to belong to the superfamily of Harbinger DNA transposons that possess nuclease activity (Kapitonov and Jurka, 1999), the typical catalytic DDE domain was disturbed in POW1 (Figure S6). This observation suggests that POW1 might lose its activity as a transposase and obtain a new function during evolution, which is similar to that reported for the Arabidopsis homolog ALP1 (Kapitonov and Jurka, 2004).

In most of the cells, POW1 was exclusively observed in the nucleus (Figure 2f). Although POW1 contains a putative helix‐turn‐helix DNA binding domain and is mostly localized in the nucleus, we did not detect obvious transcriptional activation or repressive activity of this protein in either yeast or rice protoplasts (Figure S7).

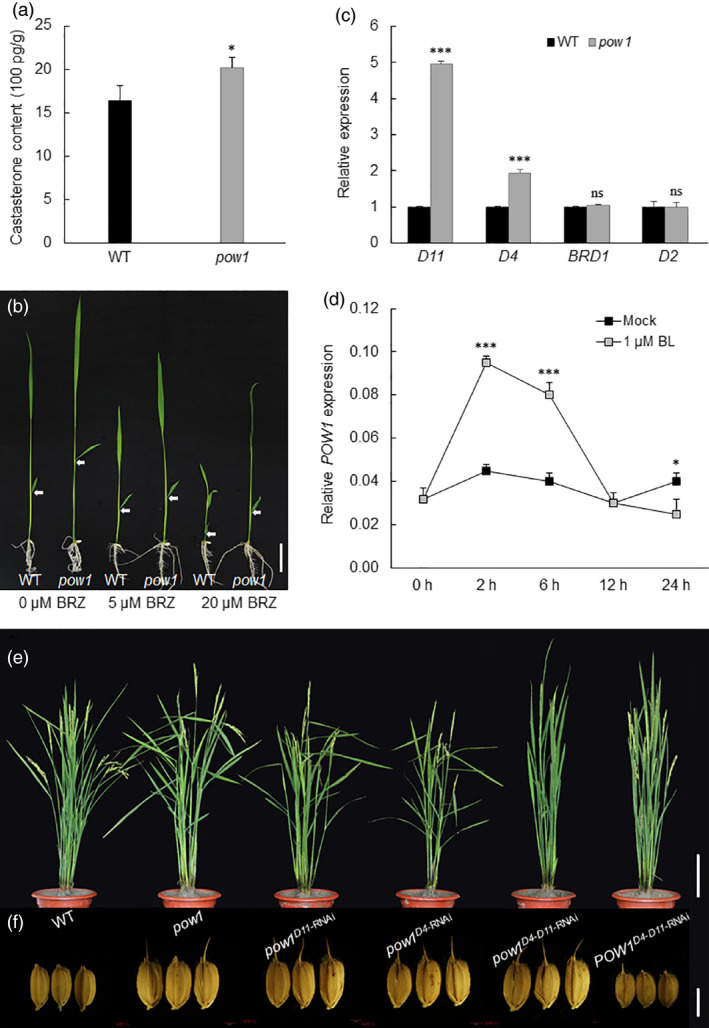

POW1 controls leaf angle formation via the BR pathway

The increase in leaf angle is the typical phenotype displayed by plants with an excessive amount of BR. In particular, the loose population structure of pow1 highly resembled plants that ectopically express At‐CYP90B1 or Zm‐CYP (Wu et al., 2008), which are homologs of rice D4 and D11, respectively. Therefore, we first quantified the endogenous BR content in the mutant. We found that the content of castasterone, a likely end product of the BR biosynthetic pathway in rice (Kim et al., 2008), was obviously higher in pow1 than in the WT (Figure 3a). The elevated endogenous BR level in the mutant was further confirmed by seedling treatment with brassinazole (BRZ), a BR biosynthesis inhibitor that specifically blocks BR biosynthesis by inhibiting the cytochrome P450 steroid C‐22 hydroxylase encoded by DWF4 (Asami et al., 2001). We found that the position of the second lamina joint in pow1 was obviously higher than that in the WT under the control conditions, and the phenotype of pow1 seedlings treated with 5 μM BRZ highly mimicked that of the WT without BRZ treatment (Figure 3b and Figure S8). Consistent with the higher endogenous BR content in pow1, we found that the expression level of the BR biosynthesis genes D4 and D11 was significantly increased in the mutant while the transcription of BRD1 and D2 did not change obviously between the pow1 and WT plants (Figure 3c). Furthermore, we found that application of exogenous BL could induce the expression of POW1 (Figure 3d). Taken together, these results indicate that POW1 is a novel regulator of BR homeostasis.

Figure 3.

POW1 controls leaf angle formation via BR biosynthesis pathway. (a) Endogenous BR quantification. Lamina joints of flag leaves of 2‐month‐old field grown plants were sampled. Data are means ± SE (n = 3). *: p < 0.05 (Student’s t test). (b) BRZ treatment assay. Sterilized seeds were sowed on half strength MS medium containing different concentrations of BRZ and grew for 1 week after germination. The white arrows indicate the second lamina joint. Bar = 1 cm. (c) Expression analysis of BR biosynthesis genes. Lamina joints of flag leaves of 2‐month‐old field grown plants was sampled. The transcript levels were normalized against WT, which was set to 1. Data are means ± SE (n = 3). ***: p < 0.001 (Student’s t‐test). (d) BR induction assay. The whole shoots of 2‐week‐old seedlings under 1 μM epiBL treatment were collected at the indicated time points after treatment. Actin was used as the internal control. Data are means ± SD (n = 3). *: p < 0.05 and ***: p < 0.001 (student’s t‐test). (e,f) Comparison of leaf angle and grain size among the D4‐RNAi, D11‐RNAi and D4‐D11‐RNAi plants under the background of pow1 and WT, respectively. Bars = 20 cm (e) and 5 mm (f).

To verify whether the pow1 phenotype was caused by ectopic expression of the BR biosynthesis genes D4 and D11, we constructed RNAi transgenic plants of the two genes under the mutant background. We did not observe phenotypic recovery in the D4 or D11 single RNAi transgenic plants (Figure 3e,f and Figure S9), which might be due to the higher expression level of the other gene (Figure S9a). When simultaneously knocking down these two genes (Figure S9a), we found that the pow1D4 ‐ D11 ‐RNAi plant exhibited a leaf angle much smaller than that of pow1 and was comparable to that of D4‐D11 double RNAi transgenic plants under the background of the WT (POW1D4 ‐ D11 ‐RNAi; Figure 3e and Figure S9b). This result suggests that POW1 controls leaf angle formation by regulating the transcription of D4 and D11. Unexpectedly, we did not observe obvious changes in grain size in any of the 47 independent pow1D4 ‐ D11 ‐RNAi lines, although the grain size of the POW1D4 ‐ D11 ‐RNAi plant was sharply reduced compared with that of the WT (Figure 3f and Figure S9c,d).

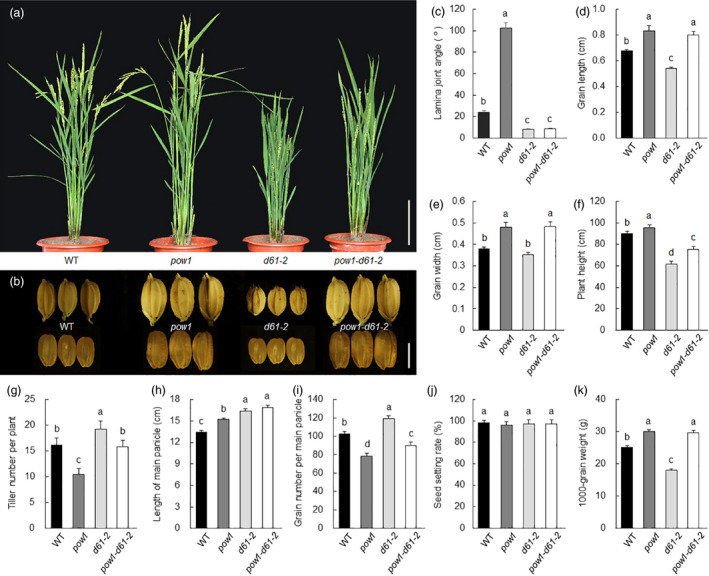

The involvement of POW1 in BR homeostasis was further confirmed by crossing pow1 with d61‐2, a strong allelic mutation of the BR receptor gene OsBRI1 (Yamamuro et al., 2000). To exclude background noise, we selected the pow1‐d61‐2 double mutant and the d61‐2 single mutant from the same genetic population for phenotypic comparison. We found that the leaf angle of the pow1‐d61‐2 double mutant was similar to that of the d61‐2 single mutant and significantly smaller than that of the WT (Figure 4a,c). Again, we did not observe any difference in grain size between pow1 and pow1‐d61‐2 (Figure 4b,d,e).

Figure 4.

POW1 controls leaf angle formation via BR signalling pathway. (a,b) Comparison of plant architecture (a) and grain appearance (b) among WT, pow1, d61‐2 and pow1‐d61‐2 double mutant. Bars == 20 cm (a) and 5 mm (b). (c–l) Stasistical analysis of leaf angle (c), grain length (d), grain width (e), plant height (f), tiller number (g), length of main panicle (h), spikelet number per main panicle (i), seed setting rate (j) and 1000‐grain weight (k) in WT, pow1, d61‐2 and pow1‐d61‐2 double mutant. Data are means ± SD (n = 20). Bars followed by the different letters represent significant difference at 5%.

An investigation of overall agronomic traits revealed that in addition to the decreased leaf angle and increased grain size, the pow1‐d61 double mutant also displayed reduced plant height (Figure 4f). Although the grain size of pow1 increased approximately 20.0% in length, 23.2% in width, and 23.7% in thickness compared with those of WT (Figure 1f), the 1000‐grain weight of the mutant increased about 20% (Figure 4k) but not 80% (Theoretically 1.20 × 1.23 × 1.24 ≈ 1.83). This should be due to the rapid grain filling of pow1 at the milk stage (Figure S10a), resulting in the loose distribution of starch granules in the endosperm (Figure S10b,c). The tiller number and seed fertility of the double mutant were similar to those of the WT (Figure 4g,j). Although panicle length was greatly increased in pow1‐d61‐2 plants (Figure 4h), grain number per panicle obviously decreased in the double mutant (Figure 4i), which is likely associated with the overly increased grain size (Figure 4b). These observations suggest that if the grain size could be reduced properly under the background of the pow1‐d61 double mutant, the POW1‐D61 module would have great potential in high‐yield rice breeding.

POW1 interacts with TAF2, a positive grain size regulator

To explore how POW1 affects the transcription of D4 and D11, we focused on OsBZR1, a central transcription factor reported to mediate the transcription of BR biosynthesis genes by binding directly to the promoters of D4 and D11 (Bai et al., 2007; Qiao et al., 2017). However, no direct interaction was detected between POW1 and OsBZR1 in yeast or rice protoplasts (Figure S11). This result suggests that factors other than OsBZR1 might be involved in POW1‐mediated inhibition of BR biosynthesis.

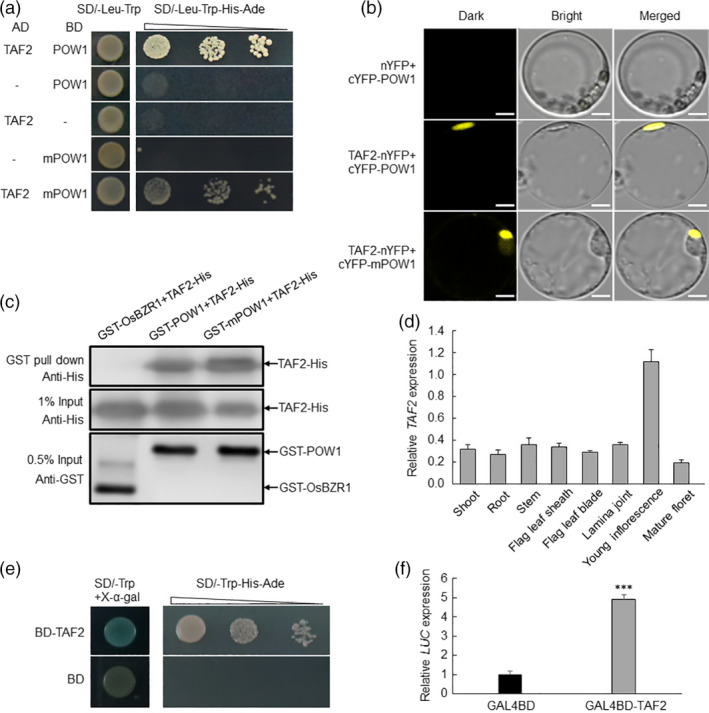

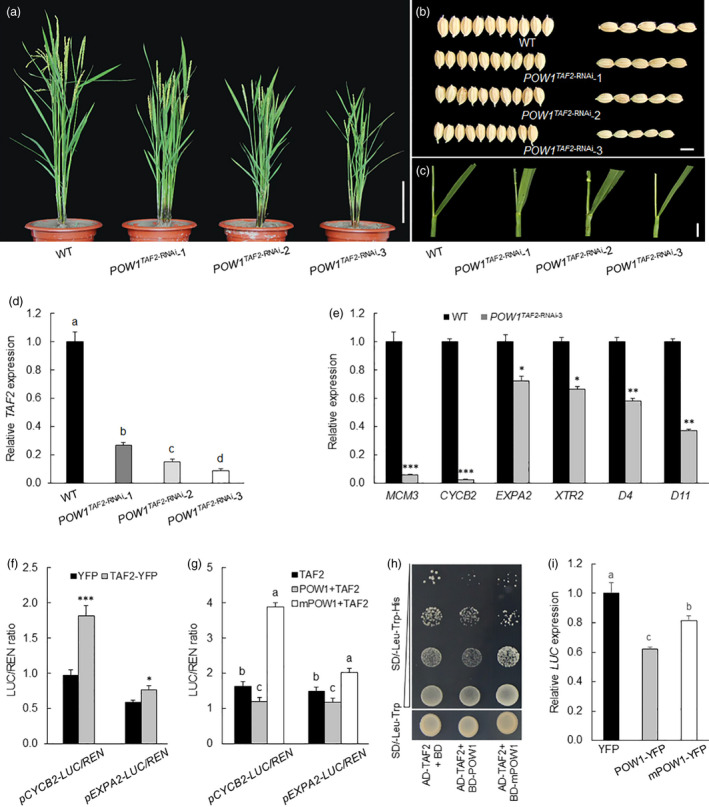

POW1 is the closest rice homolog of Arabidopsis ALP1 (Figure S3), a component of the PRC2 complex involved in H3K27me3 catalysis and affecting organ size development (Gu et al., 2014; Hartwig et al., 2012; Liang et al., 2015; Liu et al., 2015). Because the BR biosynthesis genes D4 and D11 show altered transcription under the pow1 background (Figure 3c), we therefore queried whether POW1 acts on the transcription of downstream genes via epigenetic pathways. However, we observed no significant alteration in the H3K27me3 level within either the D4 or D11 gene locus (Figure S12). This result is consistent with previous studies showing that the regulation of grain size by the core components of the PRC2 complex seems to be independent of BR biosynthesis (Folsom et al., 2014; Liu et al., 2016; Zhang et al., 2012). Therefore, we speculated that POW1 carries out transcriptional regulation by associating with other factors. To this end, we screened its potential interactors using a cDNA library with the yeast two‐hybrid system. Among the 274 sequenced positive colonies, we were highly interested in one POW1‐interacting insert (Figure 5a–c), which is the C‐terminus of LOC_Os09g24440 (http://rice.plantbiology.msu.edu/) predicted to encode the transcription initiation factor TFIID subunit 2 (TAF2, https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/nucleotide/XM_015756386.2). This subunit is a highly conserved member, and its important role in cell cycle progression is highly similar to that of POW1 (Lago et al., 2004; Figure 1h). TAF2 is strongly expressed in young inflorescences (Figure 5d) and possesses intense transactivation activity (Figure 5e,f). Therefore, we inferred that POW1 and TAF2 might function together to mediate rice development. Because TAF2 has no paralogs in the rice genome (https://blast.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/Blast) and knockout of the core components, such as TAF1 or TAF6, typically causes a lethal phenotype (Lago et al., 2005; Waterworth et al., 2015), we constructed TAF2‐RNAi transgenic plants under the background of KY131 to study its function. Among the 52 independent transgenic lines, we selected three lines that showed differentially suppressed expression of TAF2 for phenotypic analysis (Figure 6a,d). We found that both grain size and grain width in the three lines were reduced along with down‐regulated TAF2 transcription levels (Figure 6b,d and Figure S13a–c). Cytological observation revealed that in the glume of the POW1TAF2 ‐RNAi plants, the cell number significantly decreased (10.9% in the longitudinal direction and 10.2% in the transverse direction; Figure S14a), while the cell size was only moderately reduced (2.5% in length and 2.2% in width; Figure S14b) compared with that of the WT. Consistently, we found that the expression of the cell division markers MCM3 and CYCB2 was significantly repressed along with the down‐regulation of TAF2, while the expression levels of EXPA2 and XTR2 only moderately decreased in the TAF2‐RNAi plants (Figure 6e). These results indicate that TAF2 controls grain size mainly by affecting cell division.

Figure 5.

Transactivation assay of TAF2 and its interaction with POW1. (a–c) Interaction assay between POW1/mPOW1 and TAF2. For pull‐down assay (c), the OsBZR1‐TAF2 combination was used as the negative control. Bars = 10 μm (b). (d) Expression analysis of TAF2 in various plant tissues. Actin was used as the internal control. Data are means ± SD (n = 3). (e,f) Transactivation assay. The transactivation activity of TAF2 was observed in yeast (e) and rice protoplast (f). ***: p < 0.001 (Student’s t‐test).

Figure 6.

TAF2 controls grain size by affecting mainly cell division. (a‐c) Phenotypes of whole plant, grain size and leaf angle of the TAF2‐RNAi transgenic plants. Bars = 20 cm (a), 5 mm (b) and 1 cm (c). (d,e) Expression analysis of TAF2, MCM3, CYCB2, EXPA2, XTR2, D4 and D11 in the TAF2‐RNAi transgenic plants. Young inflorescences of about 2 mm long were sampled for detecting TAF2, MCM3, CYCB2, EXPA2 and XTR2, and lamina joints of flag leaves of 2‐month‐old field grown plants were sampled for detecting D4 and D11. The transcript levels were normalized against WT, which was set to 1. Data are means ± SE (n = 3). *: p < 0.05, **: p < 0.01, and ***: p < 0.001 (Student’s t‐test). Bars followed by different letters indicate significant difference at 5%. (f) Transcriptional activation of OsTAF2 on CYCB2 and EXPA2. Data are means ± SD (n = 3). *: p < 0.05 and ***: p < 0.001 (student’s t‐test). (g) Analysis of the effect of POW1 and mPOW1 on the transactivation activity of OsTAF2. Data are means ± SD (n = 3). Bars followed by different letters represent significant difference at 5%. (h,i) Inhibitory effects of POW1 on the transactivation activity of TAF2 in yeast (h) and rice protoplast (i). Bars followed by different letters indicate significant difference at 5%. Indicating that the inhibitory effect of mPOW1 on TAF2 was significantly weakened compared with that of the functional POW1.

Among the TAF2 knockdown transgenic lines, TAF2‐RNAi‐1 displayed a decrease in not only grain size but also leaf angle compared with the WT (Figure 6a–c and Figure S13b–d). However, we did not observe a linear relationship between the change in leaf angle and the decrease in TAF2 expression level in these transgenic plants (Figure 6c,d and Figure S13a,d), suggesting that the decrease in leaf angle observed in TAF2‐RNAi‐1 is due to the positional effect of the T‐DNA. Because POW1 participates in BR homeostasis (Figures 3,4) and BR is known to affect grain development (Li et al., 2018), we queried whether POW1‐interacting TAF2 regulates grain size through the BR pathway. Therefore, we determined the expression levels of D4 and D11 in TAF2‐RNAi transgenic plants. We found that the expression of the BR biosynthesis genes D4 and D11 was repressed along with the down‐regulation of TAF2 (Figure 6e), which is in sharp contrast to the up‐regulation of these genes under the pow1 background (Figure 3c). These results suggest that POW1 and TAF2 act antagonistically in BR homeostasis. However, our further studies revealed that TAF2 regulates grain development independent of the BR pathway (see below).

POW1 regulates grain size mainly through TAF2

Although POW1 showed a physical interaction with TAF2 (Figure 5a–c), these two factors showed contrasting effects on the expression of downstream genes involved in basic cellular processes (Figures 1h,6e), suggesting that POW1 plays an antagonistic role to TAF2 in regulating related biological traits. Consistent with this deduction, we found that TAF2 could effectively activate the expression of downstream cellular process genes (Figure 6f) while the activation activity was substantially suppressed by the POW1 protein (Figure 6g). Mutated POW1 (mPOW1) interacted well with TAF2 (Figure 5a–c); however, the suppressive effect of mPOW1 on TAF2 was largely reduced compared with that of POW1 (Figure 6h–i). These results suggest that POW1 antagonizes TAF2 in regulating downstream gene transcription.

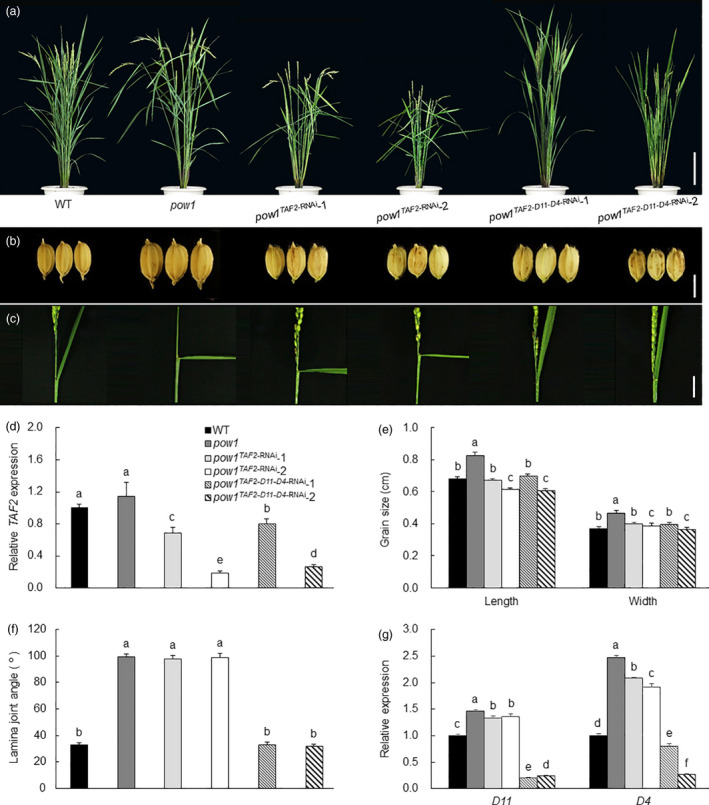

To understand whether POW1 regulates grain size through TAF2, we constructed TAF2‐RNAi transgenic plants under the pow1 background (Figure 7a,d). We found that knockdown of TAF2 could largely recover the grain size of pow1 to that of the WT (Figure 7b,e) while the grain size of pow1TAF2 ‐RNAi plants was obviously larger than that of POW1TAF2 ‐RNAi plants (Figure S15). Compared with the grain size recovery of the pow1 mutant, the enlarged leaf angle phenotype remained unchanged in the pow1TAF2 ‐RNAi plants (Figure 7c,f). Therefore, we analysed the expression levels of the BR biosynthesis genes D4 and D11 in these transgenic plants. We found that transcription of D4 and D11 was moderately suppressed in the pow1TAF2 ‐RNAi plants, although the expression level of these two genes was significantly higher than that in the WT (Figure 7g). This observation is consistent with the antagonistic effect of POW1 and TAF2 on the transcription of BR biosynthesis genes (Figures 3c,6e).

Figure 7.

Separable regulation of POW1 in grain size and leaf angle development. (a–c) Phenotypes of whole plant, grain size and leaf angle of TAF2‐RNAi and TAF2‐D4‐D11‐RNAi transgenic plants under the pow1 mutant background. Bars = 20 cm (a), 5 mm (b), and 2 cm (c). (d) Expression analysis of TAF2 in pow1, WT, TAF2‐RNAi and TAF2‐D4‐D11‐RNAi transgenic plants. Young inflorescences of about 2 mm long were sampled. The transcript levels were normalized against WT, which was set to 1. Data are means ± SE (n = 3). Bars followed by different letters represent significant difference at 5%. (e,f) Statistical analysis of grain size and leaf angle in pow1, WT, TAF2‐RNAi and TAF2‐D4‐D11‐RNAi transgenic plants. Data are means ± SE (n = 30). Bars followed by different letters represent significant difference at 5%. (g) Expression analysis of D4 and D11 in pow1, WT, TAF2‐RNAi and TAF2‐D4‐D11‐RNAi transgenic plants. Lamina joints of flag leaves of 2‐month‐old field grown plants were sampled. The transcript levels were normalized against WT, which was set to 1. Data are means ± SE (n = 3). Bars followed by different letters represent significant difference at 5%.

To observe the combined effect of modulating TAF2 and BR pathways under the pow1 mutant background, we constructed transgenic plants with simultaneously down‐regulated expression of TAF2, D4 and D11 (pow1TAF2‐D4‐D11‐ RNAi). We found that the triple TAF2‐D4‐D11‐RNAi transgenic plants displayed largely rescued phenotypes of pow1 similar to that of the WT, that is decreased grain size and erect leaf angle (Figure 7). Taken together, these results demonstrate that POW1 controls leaf angle formation via the BR pathway and regulates grain size development under the assistance of TAF2.

Discussion

POW1 is a novel regulator of BR‐mediated leaf angle formation

Loss of function of POW1 enhanced the expression of BR biosynthesis genes D4 and D11 (Figure 3c), resulting in a higher BR content that could induce the expression of POW1 (Figure 3a,d). These results suggest that POW1 plays a critical role in the feedback regulation of BR homeostasis. As a well‐studied phytohormone, BR has been shown to have multiple biological functions, including leaf angle formation and grain size regulation (Tong and Chu, 2018). Consistently, we found that down‐regulation of D4 and D11 could effectively modify grain development under the WT background (Figure 3 and Figure S9). Although dysfunction of genes involved in BR biosynthesis rescued the enlarged leaf angle phenotype of the pow1 mutant, the grain size of pow1D4‐D11 ‐RNAi and pow1‐d61 double mutant plants remained unchanged compared with that of pow1 (Figures 3,4 and Figure S9). This observation might be explained by BR showing differential roles in certain tissues (Tong and Chu, 2018), and the lamina joint is one of the most sensitive tissues responding to BR fluctuation (Morinaka et al., 2006). Therefore, the effect caused by a reduction or increase in endogenous BR levels would be more prominent for the development of leaf angle than that of grain size. Moreover, a previous report showed that adaxial cell expansion is mainly responsible for BR‐induced leaf angle formation (Cao and Chen, 1995). Accordingly, the enlarged leaf angle phenotype of pow1 could be readily rescued by manipulation of the BR pathway components.

POW1 is the closest rice homolog of Arabidopsis ALP1 (Figure S5), a component of the PRC2 complex mainly associated with gene silencing (Liang et al., 2015). Although POW1 is also predicted to function as a negative regulator of chromatin silencing (https://www.uniprot.org/uniprot/Q0D898), we did not detect any alteration in the H3K27me3 level within either the D4 or D11 gene locus (Figure S12), suggesting that POW1 does not regulate BR biosynthesis through epigenetic pathways. In Arabidopsis, the master transcription factor AtHY5 does not show any transactivation activity in yeast cells (Ang et al., 1998), although it can act both as an activator and a repressor of a large number of downstream targets (Gangappa and Botto, 2016). Therefore, although POW1 shows no obvious transactivation or repression activity (Figure S7), the putative helix‐turn‐helix DNA binding domain (Figure 2e) makes it possible to bind directly to the promoters of downstream genes, including D4 and D11. Moreover, the initiation of gene transcription is known to depend not only on specific transcription factors but also on the transcription initiation complex, which consists of TFIIA, TFIIB, TFIID, TFIIE, TFIIF, TFIIH and RNA polymerase II (Gupta et al., 2016). TFIID plays a key role in transcription initiation because it first binds the core promoter and then recruits other components to form a mature transcription initiation complex. Although TAFs are categorized as general transcription factors, studies in Arabidopsis have revealed their functions in specific plant developmental processes, such as light signalling (Bertrand et al., 2005), flowering time (Eom et al., 2018), pollen tube growth (Lago et al., 2005) and leaf development (Tamada et al., 2007). To date, knowledge on the function of TAFs during rice development remains lacking, and our findings show that TAF2 affects the expression of cell division and cell expansion genes as well as BR biosynthesis genes (Figure 6e). As the core TFIID component, TAF2 is always recruited first to the transcription initiation region (Nogales et al., 2017). Therefore, it is quite possible that POW1 is recruited to the promoters of the BR biosynthesis genes D4 and D11 through its interaction with TAF2 (Figure 5a–c), a regulatory manner widely adopted by other non‐DNA‐binding proteins, such as MODD (Tang et al., 2016) and OsTrx1 (Jiang et al., 2018).

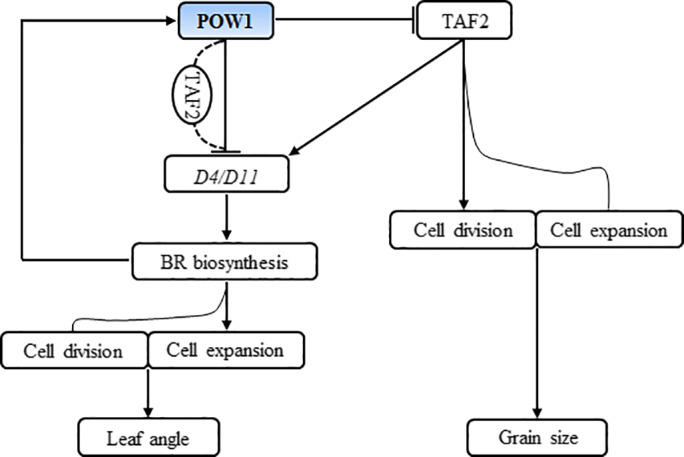

Although POW1 and TAF2 show similar expression patterns in lamina joints and young inflorescences (Figures 2d,5d), the POW1‐TAF2 module functions only in grain size but not in leaf angle (Figure 7). We present a model of how POW1 regulates BR biosynthesis to influence leaf angle development (Figure 8). In WT plants, the expression of the BR biosynthesis genes D4 and D11 was repressed by POW1. The repression of POW1 on the BR pathway in turn reduces the expression of POW1 and weakens its inhibition of D4/D11 transcription to maintain in vivo BR homeostasis and thus the normal development of leaf angle. Although the BR pathway is positively regulated by TAF2, TAF2‐activated BR biosynthesis induces the expression of POW1, which in turn suppresses the transactivation activity of TAF2, thus maintaining endogenous BR at a proper level. Therefore, although TAF2 might play a role in endogenous BR homeostasis, its antagonistic relationship with POW1 makes it unable to influence BR‐mediated leaf angle formation. Mutation of POW1 reduced the repression of D4/D11 expression and TAF2 transactivation activity, and the resultant increase in endogenous BR levels enhanced the accumulation of the mPOW1 protein, which still possessed partial repression activity (Figure 6h–i). Therefore, the endogenous BR content in the pow1 mutant could be maintained at a higher level, resulting in the enlarged leaf angle phenotype. Although we still do not know how POW1 functions as a repressor, our findings strongly suggest that the POW1‐BR module plays a key role in regulating rice leaf angle formation.

Figure 8.

A working model of POW1 regulating leaf angle and grain size. POW1 and BR are feedback regulated. POW1 negatively regulates the expression of BR biosynthesis genes directly or by associating with TAF2. As a general transcription initiation factor, TAF2 functions not only in cell division and cell expansion but also in BR homeostasis. Because TAF2‐activated BR biosynthesis induces the expression of POW1, which in turn represses the transactivation activity of TAF2, genetic manipulation of TAF2 thus could not increase the endogenous BR content to a level high enough to affect leaf angle formation. Mutation of POW1 reduces the repression on D4/D11 expression and TAF2 transactivation activity, and the resultant increase of endogenous BR level enhances the accumulation of the mPOW1 protein. Because mPOW1 still has some repression activity, the basic cellular processes mediated by BR and TAF2 in the mutant are activated to a certain extent, resulting in the increase of leaf angle and grain size.

POW1 controls grain size by antagonizing TAF2

Many studies have revealed the essential functions of TAFs in cell cycle progression (Bahat et al., 2013; Chen and Manley, 2000; Metzger et al., 1999; Sekiguchi et al., 1991), and our results also indicated that rice TAF2 plays an important role in grain size control by affecting the expression of cell division‐related genes (Figure 6 and Figure S14). One intriguing question would be how TAF2 maintains cell division at a proper intensity to define grain size development. We provided several lines of evidence that the antagonistic POW1‐TAF2 pathway might be critical for this maintenance. First, both POW1 and TAF2 showed the highest expression in the young inflorescence (Figures 2d,5d), at which time cell division was highly active. Second, the expression of cell cycle‐related genes was negatively regulated by POW1 but positively controlled by TAF2 (Figures 1h,6e). Third, POW1 physically interacts with TAF2 and displays a repressive function on the transactivation activity of TAF2 (Figures 5a–c, 6h–i). Fourth, the POW1‐OE transgenic plants showed a grain size reduction similar to that of TAF2‐RNAi lines (Figure 2c and Figure S4). Fifth, knockdown of TAF2 largely recovered the grain phenotype of pow1 to that of the WT; however, the grain size in the pow1TAF2 ‐RNAi plants could not be rescued to the same level as that in the POW1TAF2 ‐RNAi plants (Figures 6,7 and Figure S15). Although we could not exclude the possibility that POW1 might also regulate grain development through other genetic pathways, these observations strongly suggest that the suppressive function of POW1 on TAF2 at the protein level is critical for grain size regulation (Figure 8). The essential function of TAFs in the cell cycle makes them the basic downstream regulatory factors (Gupta et al., 2016; Nogales et al., 2017), suggesting that TAF2‐interacting POW1 is also a downstream regulator. Therefore, the POW1‐TAF2 module acts at the bottom of the gene regulatory network to coordinate cellular processes during grain development.

POW1 shows great potential in high‐yield breeding

The erect‐leaf trait is considered to be the ideotype for photosynthesis, growth and grain production (Sakamoto et al., 2006) and has attracted wide attention, especially in the molecular design of crop varieties with high yield potential. In rice, genetic analysis has revealed that overexpression of OsAGO7 could decrease leaf angle by inducing upward leaf curling. However, this gene also shows adverse effects on other traits, such as chlorophyll content (Shi et al., 2007). Loss of function of OsILA1 could increase the leaf angle by altering the formation of the vascular bundle and composition of the cell wall. However, evidence has not shown that genetic manipulation of this gene could make the leaf erect (Ning et al., 2011). Many studies have shown that leaf angle development is closely related to plant hormones, including auxin (Liu et al., 2018; Song et al., 2009; Zhang et al., 2009; Zhang et al., 2016), BR (Tong and Chu, 2018) and gibberellin (Shimada et al., 2006; Wang et al., 2009; Zhao et al., 2010), and these findings have provided valuable information for understanding the molecular mechanism that controls leaf angle formation. Genetic manipulation of the related genes could effectively decrease the leaf angle; however, many other traits, such as plant height and fertility, would be adversely modified. In particular, the development of the leaf angle in most cases us directly or indirectly related to BR (Liu et al., 2018; Shimada et al., 2006; Wang et al., 2009; Zhao et al., 2010), which also affects the development of grain size, another key yield determinant. Although the decrease in leaf angle caused by modifying the BR pathway is often accompanied by a reduction in grain size, Morinaka et al. (2006) found that moderate suppression of OsBRI1 expression could yield plants with an erect‐leaf phenotype without grain changes. In addition, a loss‐of‐function mutant of D4 displayed slight dwarfism and erect leaves without undesirable phenotypes, such as a reduction in grain size (Sakamoto et al., 2006). With standard fertilizer application, the grain yield of the d4 mutant under dense planting increased substantially compared to that of its WT under conventional conditions. In this study, we show that pow1 shows typical BR‐related phenotypes of increased grain size and leaf angle (Figure 1). However, compared with the traits regulated by BR pathway genes, these two traits in pow1 could be separately controlled by modulating the expression of TAF2 (Figure 7 and Figure S9) and BR pathway genes (Figures 3,4 and Figure S9), respectively. The separable regulation of POW1 in grain size and leaf angle development thus provides a promising strategy to design high‐yielding varieties with a compact plant architecture and an increased grain size, as observed in the pow1‐d61 double mutant plant (Figure 4). In other words, by suppressing the expression of TAF2 under the pow1‐d61 background, the grain size could be freely modified without altering the erect‐leaf phenotype, and other favourably developed agronomic traits, such as plant height, tiller number and 1000‐grain weight, could be maintained or even improved (Figure 4). At present, we are using a genome editing approach to modify the TAF2 promoter to obtain an ideal allele with moderate down‐regulation of TAF2 expression and finally apply the pow1‐d61‐taf2 module in rice production.

In summary, we report the identification of POW1 as a novel regulator of BR‐mediated leaf angle formation and TAF2‐mediated grain size development. The separable function of POW1 in grain size and leaf angle regulation implies that POW1 occupies a critical position for combining these two important biological processes. Compared with previous findings (Morinaka et al., 2006; Sakamoto et al., 2006), our results described here suggest that utilization of the POW1‐TAF2‐BR module could simultaneously improve the leaf angle and grain size, thus promoting high‐yield breeding in rice.

Methods

Plant materials and growth conditions

The pow1 mutant was isolated from the M2 population of the japonica cultivar KY131 treated with sodium azide. The mapping population was generated by crossing pow1 with the indica cultivar Kasalath, and SSR markers were modified from the Gramene database (http://www.gramene.org/). To create the double mutant between pow1 and d61‐2, pow1 was used as the female to cross with the d61‐2 mutant, and the resulting F1 plants were backcrossed with pow1 three times. The self‐fertilized BC3F2 plants were genotyped with gene‐specific markers to select the double mutant plant. To exclude background noise, we also selected the pow1 and d61‐2 single mutants from the same genetic population for phenotypic comparison. For the BRZ treatment, the sterilized seeds were sown on half‐strength MS medium that contained 0, 5 and 20 μM BRZ and then grown for 1 week after germination in a phytotron (SANYO) with 14 h light (28 °C)/10 h dark (25 °C), 65–70% relative humidity and 150 µM/m2/s photon flux density. All materials used in this study were cultivated in the experimental fields in Beijing and Qingan (Heilongjiang Province) during the summer season or in Lingshui (Hainan Province) during the winter season.

Histological analysis

To prepare paraffin sections, the samples were fixed in FAA solution (50% ethanol, 5% acetic acid and 3.7% formaldehyde) overnight at 4 °C after 15 min vacuum treatment; the samples were subsequently dehydrated with a graded ethanol series and embedded in paraplast for 2 days at 60 °C. Sections (8 μm) were prepared with a microtome (RM2235, Leica), stained with 0.5% toluidine blue and observed with a microscope (BX53, Olympus).

For the SEM analysis, glumes were collected prior to grain filling and fixed in 1× PBS solution that contained 2.5% glutaraldehyde overnight at 4 °C. After dehydration with a series of ethanol solutions and substitution with ethyl acetate, the samples were critical‐point dried, sprayed with gold particles and observed with a scanning electron microscope (S‐3000N, Hitachi). Cells of the middle part of the lemma were observed for imaging. To observe the grain endosperm, selected grains were cut using the bladeless part, and the cut cross‐section surface was coated with gold in a vacuum using an ion sputtering device (JFC‐1100E, JEOL, Tokyo, Japan). The samples was observed with a scanning electron microscope (S‐3000N, Hitachi).

Quantification of endogenous BR content

Fresh leaves of 2‐month‐old pow1 and WT plants were frozen in liquid nitrogen and then ground to a fine powder. BR quantification was performed based on a previously described method (Xin et al., 2013).

Map‐based cloning

The mapping population was constructed by crossing pow1 with the indica cultivar Kasalath. Using 20 bulked F2 plants with WT and mutant phenotypes, the candidate gene was first mapped to the short arm of chromosome 7 between the SSR markers RM8010 and RM1353. Further analysis of the F2 mutant plants subsequently fine‐mapped the causal gene to the region between RM21072 and RM21057, and sequence comparisons were then performed between the pow1 and WT plants for all 21 annotated genes within this region.

qRT‐PCR assay

Total RNA was extracted using RNAios PLUS reagent (Takara), and 1 μg RNA was reverse‐transcribed by oligo (dT) primers using a reverse transcription kit (Promega) after digestion with RNase‐free DNaseI (Fermentas). The qRT‐PCR assay was performed in triplicate with SYBR Green I Master reagent and the Light Cycler Nano system (Roche). Actin was used as the internal control for normalization. The primers used in this study are listed in Table S1.

Vector construction and plant transformation

For the complementation test, a 4.6‐kb genomic fragment that contained the entire wild‐type POW1 genomic sequence, including the 2.2‐kb native promoter, was cloned into the pZH2B vector. For the overexpression construct, the full‐length coding sequence of POW1 was amplified from KY131 and ligated into pZH2Bi driven by the ubiquitin promoter. For the POW1 knockout assay, plasmid construction and plant transformation were all performed by BIOGLE GeneTech (Hangzhou, China). To create D4, D11 and TAF2 single RNAi plants, the hairpin sequence with two ˜300‐bp cDNA inverted repeats was inserted into pZH2Bi. For the D4‐D11 double RNAi construct, the cassette, including the ubiquitin promoter, hairpin sequence and Nos terminator, was cut from the D4‐pZH2Bi construct and inserted into the D11‐pZH2Bi construct. These vectors were transformed into the WT or pow1 with the Agrobacterium tumefaciens‐mediated transformation method. The primers used for vector construction are listed in Table S1.

Transient expression assay in rice protoplast

For subcellular localization, the full‐length coding sequence of POW1 was cloned into the pSAT6‐EYFP‐N1 vector to form the POW1‐EYFP (enhanced yellow fluorescent protein) construct. The empty vector was used as a negative control. For the BiFC assay, the coding sequences of POW1, OsBZR1 and TAF2 were PCR amplified, inserted into the pUC19‐VYNE (R) or pUC19‐VYCE (R) vector and fused with the N‐ or C‐terminus of the Venus YFP sequence, respectively. These vectors and the corresponding empty vectors were cotransformed in different combinations into rice protoplasts. The YFP signal was detected with a confocal laser scanning microscope (CLSM; FV1000, Olympus) after 16 h incubation at 28 °C in the dark.

For the transactivation assay, the coding sequences of POW1 and TAF2 were amplified and fused with the GAL4 DNA binding domain in the pRT‐BD vector, and the resulting constructs were used as the effectors. The LUC vector, which contains the GAL4 binding motif and luciferase coding region, was used as the reporter, and the vector that expressed Renilla luciferase (pTRL) was employed as the internal control. The effectors were then cotransformed into rice protoplasts with the reporter and the internal control.

To detect TAF2‐mediated activation of the expression of genes involved in basic cellular processes, the promoters (˜2.0 kb) of CYCB2 and EXPA2 were cloned into the LUC vector by replacing the 35S promoter, and the resulting constructs were used as reporters. To create the effector construct, the coding sequence of TAF2 was cloned into the pSAT6‐EYFP‐N1 vector. To diminish the background difference, the empty pSAT6‐EYFP‐N1 vector was used as the negative control to cotransform each reporter construct into the protoplasts of pow1 and WT plants. The pTRL vector was also cotransfected as an internal control (Figure S16).

To detect the repressive effects of POW1 on TAF2, the coding sequences of POW1, mPOW1 and TAF2 were PCR amplified and inserted into pRT‐BD for TAF2 and pSAT6‐EYFP‐N1 for POW1 and mPOW1. The LUC and pTRL vectors were then cotransformed with the resulting constructs into rice protoplasts. The empty pSAT6‐EYFP‐N1 vector was also cotransformed as a negative control (Figure S16). After 16 h incubation at 28 °C in the dark, the protoplast was centrifuged at 150 × g and the pellet was used for the dual‐luciferase assay as described in the Dual‐Luciferase® Reporter Assay System Manual (Promega). All transformations were performed via the PEG (polyethylene glycol)/CaCl2‐mediated method. The primers used for the transient assay are listed in Table S1.

Yeast two‐hybrid assay

The coding sequences of POW1, TAF2 and OsBZR1 were cloned into the pGBKT7 or pGADT7 vector (Clontech), and the resulting constructs and the corresponding empty vectors were then transformed into the yeast strain Golden Yeast with different combinations. Interactions were detected on SD/‐Leu‐Trp‐His‐Ade medium or SD/‐Leu‐Trp‐His medium. The transformation was performed as described in the Clontech Yeast Two‐Hybrid System User Manual. The primers used for the yeast two‐hybrid assay are listed in Table S1.

Protein sequence alignment and phylogenetic analysis

For the DDE domain comparison, the amino acid sequence of POW1 covering the putative DDE domain was aligned with the Arabidopsis homolog ALP1, the known DDE domain‐containing transposases of Hs Harbi1 from humans (Homo sapiens) and Dr Harbi1 and XP_009300611.1 from zebrafish (Danio rerio). Alignments were performed using ClustalW. For the phylogenetic analysis, POW1 and the 34 paralogs (http://plants.ensembl.org/Oryza_sativa/Info/Index) and Arabidopsis ALP1 were applied to produce a neighbour‐joining tree using Vector NTI suite 9.0.

ChIP assay

Formaldehyde cross‐linked chromatin DNA was isolated from the leaves of 2‐week‐old pow1 and WT seedlings. Immunoprecipitation was performed with an anti‐H3K27me3 antibody (Millipore 07‐449), and H3K27me3‐bound DNA was isolated with Protein A Dynabeads (Invitrogen, 10002D). ChIP DNA was then used as the template for the qRT‐PCR assay. The input DNA before immunoprecipitation was used as the control. Primers used for the ChIP assay are listed in Table S1.

Pull‐down assay

The full‐length coding sequences of POW1, mPOW1 and OsBZR1 were inserted into the pGEX‐6 vector and transformed into Rosetta through heat shock. GST‐tagged proteins were induced by 0.1 mM IPTG at 18°C and bound by glutathione beads (GE Healthcare). The full‐length coding sequence of TAF2 was inserted into the pET28a vector, and the resulting TAF2‐His fusion protein was then induced by 0.1 mM IPTG at 37°C and subsequently purified by Ni‐NTA His Bind Resin (Millipore 70666‐3). Approximately 0.2 μg of GST‐POW1, GST‐mPOW1 and GST‐OsBZR1 bound to GST beads were incubated with ˜0.3 μg TAF2‐His at 4 °C overnight, and then, the beads were collected by centrifugation and washed with 1 × PBS 5 times. The output protein was detected using an anti‐His antibody (Abmart M20020). The primers used for the pulldown assay are listed in Table S1.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Author contributions

S.Y. conceived and supervised the project. S.Y. and L.Z. designed the study and analysed the data. L.Z. performed the functional analyses. R.W. screened the pow1 mutants, created mapping population and double mutants, and carried out field management. Y.X. and D.X. contributed to plasmid construction and phenotyping. Y.W. contributed to the reagents and equipment management. Y.X. and L.Z. prepared the photographs. S.Y. wrote the manuscript. All authors have read and approved the final manuscript.

Supporting information

Figure S1. Organ size comparison between pow1 and WT. Bars = 2 cm for (a), 5 cm for (b), 2 cm for (c), 2 mm for (d) and (e), and 500 μm for (f).

Figure S2. Comparison of the inner epidermal cells of the lemma between pow1 and WT. Spikelets at the grain filling stage were sampled (n = 10). Bars = 50 μm. **: p < 0.01 (Student’s t test).

Figure S3. Histological analysis of lamina joint. (a) and (c) represent sections before the leaf angle forms, and (b) and (d) represent sections after the leaf angle forms. Red double‐headed arrows in (a) and (b) indicate the adaxial cell of lamina joint. In (c) and (d), left side of each section is the adaxial side of lamina joint. Bars = 100 μm.

Figure S4. Genetic certification of the cause gene of the pow1 mutant. (a) The target site designed for knocking out the POW1 gene by CRISPR/Cas9 system and amino acid sequence comparison between POW1‐KO and WT. (b) Expression analysis of POW1 in the POW1‐OE transgenic plant. Young inflorescences of 2 mm long were sampled. Actin was used as the internal control. The transcript level was normalized against WT, which was set to 1. Data are means ± SD (n = 3).***: p < 0.001. (c,d) Comparison of grain size (c) and leaf angle (d) among pow1, WT, pow1‐C, POW1‐KO and POW1‐OE plants. Three independent POW1‐OE transgenic lines with similar expression level were selected for phenotypic measurement. Data are means ± SE (n = 30). Bars followed by different letters represent significant difference at 5%.

Figure S5. Phylogenetic analysis of rice putative PIF/Harbinger class transposases. Bar indicates branch length.

Figure S6. DDE domain alignment. The DDE domain of POW1, ALP1 and HARBI1 from human and zebrafish was compared. *indicates conserved DDE triads. Indicating that the DDE domain structure is disrupted in both ALP1 and POW1.

Figure S7. Analysis of POW1 transactivation activity. No significant transcriptional activation or repressive activity was observed for POW in yeast (a) or rice protoplast (b).

Figure S8. Comparison of the height of 2nd lamina joint between pow1 and WT under BRZ treatment. Sterilized seeds were sowed on half strength MS medium containing different concentrations of BRZ and grew for 1 week after germination. Data are means ± SD (n = 10). *: p < 0.05 and ***: p < 0.001.

Figure S9. POW1 regulates leaf angle but not grain size through BR pathway. (a) Expression analysis of D4 and D11 in the single and double RNAi transgenic plants. Lamina joints of flag leaves of 2‐month‐old field grown plants were sampled. Actin was used as the internal control. The transcript levels were normalized against WT, which was set to 1. Data are means ± SD (n = 3). Bars followed by different letters represent significant difference at 5%. (b–d) Comparison of leaf angle (b), grain length (c), and grain width (d) among the D4/D11 RNAi transgenic plants. Three independent transgenic lines with similar expression level were selected for each transgene. Data are means ± SD (n = 30). Bars followed by different letters represent significant difference at 5%.

Figure S10. Observation of grain filling and starch granule distribution in pow1 and WT. The grain filling rate was calculated by the ratio of grain weight to 30 DAP in each developmental stage (n = 20). Indicating that starch granules of pow1 shows disordered distribution and lower compactness compared to that of WT. Bars = 25 μm. ***: p < 0.001.

Figure S11. Interaction assay between POW1 and OsBZR1. No interaction was detected between POW1 and OsBZR1 in yeast (a) or rice protoplast (b). Bars = 10 μm.

Figure S12. DNA Methylation Assay. No obvious difference was observed for H3K27me3 levels within either D4 or D11 gene locus between pow1 and WT. Data are means ± SD (n = 3).

Figure S13. TAF2 is a positive grain size regulator. For TAF2 expression analysis (a), young inflorescences of about 2 mm long were sampled. Actin was used as the internal control. The transcript levels were normalized against WT, which was set to 1. Data are means ± SD (n = 3). Bars followed by different letters represent significant difference at 5%. Indicating that grain length (b) and grain width (c), but not leaf angle (d), are reduced along with the down‐regulation of TAF2 (a).

Figure S14. Comparison of the inner epidermal cells of the lemma between WT and TAF2‐RNAi transgenic plants. Spikelets at the grain filling stage were sampled (n = 10). ***: p < 0.001 and *: p < 0.05 (Student’s t test).

Figure S15. Grain size comparison of TAF2‐RNAi transgenic plants under pow1 and WT background, respectively. Data are means ± SD (n = 30).

Figure S16. Sketch of the constructs used for luciferase assay. (a) Constructs for detecting the transactivation activity of TAF2 on cell division genes. (b) Constructs for detecting the transactivation activity of TAF2 on cell division genes in the presence of POW1 and mPOW1.

Table S1. Primers used in this study.

Acknowledgements

We thank Professor Shouyi Chen (Institute of Genetics and Developmental Biology, Chinese Academy of Sciences) for providing the pRT‐BD and pTRL‐LUC vectors. The d61‐2 mutant was generously presented by Prof. Chengcai Chu (Institute of Genetics and Developmental Biology, Chinese Academy of Sciences). This work was supported by grants from the Strategic Priority Research Program of the Chinese Academy of Sciences (XDA24030201), and the National Key Research and Development Program of China (Grant: 2016YFD0101801).

Zhang, L. , Wang, R. , Xing, Y. , Xu, Y. , Xiong, D. , Wang, Y. and Yao, S. (2021) Separable regulation of POW1 in grain size and leaf angle development in rice. Plant Biotechnol. J., 10.1111/pbi.13677

References

- Ang, L.H. , Chattopadhyay, S. , Wei, N. , Oyama, T. , Okada, K. , Batschauer, A. and Deng, X.W. (1998) Molecular interaction between COP1 and HY5 defines a regulatory switch for light control of Arabidopsis development. Mol. Cell, 1, 213–222. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Asahara, H. , Santoso, B. , Guzman, E. , Du, K. , Cole, P.A. , Davidson, I. and Montminy, M. (2001) Chromatin‐dependent cooperativity between constitutive and inducible activation domains in CREB. Mol. Cell. Biol. 21, 7892–7900. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Asami, T. , Mizutani, M. , Fujioka, S. , Goda, H. , Min, Y.K. , Shimada, Y. , Nakano, T. et al. (2001) Selective interaction of triazole derivatives with DWF4, a cytochrome P450 monooxygenase of the brassinosteroid biosynthetic pathway, correlates with brassinosteroid deficiency in Planta. J. Biol. Chem. 276, 25687–25691. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bahat, A. , Kedmi, R. , Gazit, K. , Richardo‐Lax, I. , Ainbinder, E. and Dikstein, R. (2013) TAF4b and TAF4 differentially regulate mouse embryonic stem cells maintenance and proliferation. Genes Cells, 18, 225–237. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bai, M.Y. , Zhang, L.Y. , Gampala, S.S. , Zhu, S.W. , Song, W.Y. , Chong, K. and Wang, Z.Y. (2007) Functions of OsBZR1 and 14‐3‐3 proteins in brassinosteroid signaling in rice. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA, 104, 13839–13844. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bertrand, C. , Benhamed, M. , Li, Y.F. , Ayadi, M. , Lemonnier, G. , Renou, J.P. , Delarue, M. et al. (2005) Arabidopsis HAF2 gene encoding TATA‐binding protein (TBP)‐associated factor TAF1, is required to integrate light signals to regulate gene expression and growth. J. Biol. Chem. 280, 1465–1473. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cao, H. and Chen, S. (1995) Brassinosteroid‐induced rice lamina joint inclination and its relation to indole‐3‐acetic acid and ethylene. Plant Growth Regul. 16, 189–196. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, Z. and Manley, J.L. (2000) Robust mRNA transcription in chicken DT40 cells depleted of TAFII31 suggests both functional degeneracy and evolutionary divergence. Mol. Cell. Biol. 20, 5064–5076. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duan, Y. , Li, S. , Chen, Z. , Zheng, L. , Diao, Z. , Zhou, Y. , Lan, T. et al. (2012) Dwarf and deformed flower 1, encoding an F‐box protein, is critical for vegetative and floral development in rice (Oryza sativa L.). Plant J. 72, 829–842. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eom, H. , Park, S.J. , Kim, M.K. , Kim, H. , Kang, H. and Lee, I. (2018) TAF15b, involved in the autonomous pathway for flowering, represses transcription of FLOWERING LOCUS C . Plant J. 93, 79–91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Folsom, J.J. , Begcy, K. , Hao, X. , Wang, D. and Walia, H. (2014) Rice Fertilization‐Independent Endosperm1 regulates seed size under heat stress by controlling early endosperm development. Plant Physiol. 165, 238–248. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gangappa, S.N. and Botto, J.F. (2016) The multifaceted roles of HY5 in plant growth and development. Mol. Plant, 9, 1353–1365. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garbett, K.A. , Tripathi, M.K. , Cencki, B. , Layer, J.H. and Weil, P.A. (2007) Yeast TFIID serves as a coactivator for Rap1p by direct protein‐protein interaction. Mol. Cell. Biol. 27, 297–311. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gu, X. , Xu, T. and He, Y. (2014) A Histone H3 Lysine‐27 methyltransferase complex represses lateral root formation in Arabidopsis thaliana . Mol. Plant, 7, 977–988. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gupta, K. , Sari‐Ak, D. , Haffke, M. , Trowitzsch, S. and Berger, I. (2016) Zooming in on transcription preinitiation. J. Mol. Biol. 428, 2581–2591. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hartwig, B. , James, G.V. , Konrad, K. , Schneeberger, K. and Turck, F. (2012) Fast isogenic mapping‐by‐sequencing of ethyl methanesulfonate‐induced mutant bulks. Plant Physiol. 160, 591–600. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hong, Z. , Ueguchi Tanaka, M. , Shimizu‐Sato, S. , Inukai, Y. , Fujioka, S. , Shimada, Y. , Takatsuto, S. et al. (2002) Loss of function of a rice brassinosteroid biosynthetic enzyme, C‐6 oxidase, prevents the organized arrangement and polar elongation of cells in the leaves and stem. Plant J. 32, 495–508. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hong, Z. , Ueguchi Tanaka, M. , Umemura, K. , Uozu, S. , Fujioka, S. , Takatsuto, S. , Yoshida, S. et al. (2003) A rice brassinosteroid‐deficient mutant, ebisu dwarf (d2), is caused by a loss of function of a new member of cytochrome P450. Plant Cell 15, 2900–2910. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jacobson, R.H. , Ladurner, A.G. , King, D.S. and Tjian, R. (2000) Structure and function of a Human TAFII250 double bromodomain module. Science, 288, 1422–1425. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jiang, P. , Wang, S. , Zheng, H. , Li, H. , Zhang, F. , Su, Y. , Xu, Z. et al. (2018) SIP1 participates in regulation of flowering time in rice by recruiting OsTrx1 to Ehd1 . New Phytol. 219, 422–435. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jiang, Y. , Bao, L. , Jeong, S.Y. , Kim, S.K. , Xu, C. , Li, X. and Zhang, Q. (2012) XIAO is involved in the control of organ size by contributing to the regulation of signaling and homeostasis of brassinosteroids and cell cycling in rice. Plant J. 70, 398–408. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kapitonov, V.V. and Jurka, J. (1999) Molecular paleontology of transposable elements from Arabidopsis thaliana . Genetica, 107, 27–37. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kapitonov, V.V. and Jurka, J. (2004) Harbinger transposons and an ancient HARBI1 gene derived from a transposase. DNA Cell Biol. 23, 311–324. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim, B.K. , Fujioka, S. , Takatsuto, S. , Tsujimoto, M. and Choe, S. (2008) Castasterone is a likely end product of brassinosteroid biosynthetic pathway in rice. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 374, 614–619. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lago, C. , Clerici, E. , Mizzi, L. , Colombo, L. and Kater, M.M. (2004) TBP‐associated factors in Arabidopsis . Gene, 342, 231–241. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lago, C. , Clerici, E. , Dreni, L. , Horlow, C. , Caporali, E. , Colombo, L. and Kater, M.M. (2005) The Arabidopsis TFIID factor AtTAF6 controls pollen tube growth. Dev. Biol. 285, 91–100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li, N. , Xu, R. , Duan, P. and Li, Y. (2018) Control of grain size in rice. Plant Reprod. 31(3), 237–251. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liang, S.C. , Hartwig, B. , Perera, P. , Mora‐García, S. , de Leau, E. , Thornton, H. , de Alves, F.L. et al. (2015) Kicking against the PRCs‐A domesticated transposase antagonises silencing mediated by Polycomb Group Proteins and is an accessory component of polycomb repressive complex 2. PLoS Genet. 11, e1005660. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lindner, M. , Simonini, S. , Kooiker, M. , Gagliardini, V. , Somssich, M. , Hohenstatt, M. , Simon, R. et al. (2013) TAF13 interacts with PRC2 members and is essential for Arabidopsis seed development. Dev. Biol. 379, 28–37. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu, X. , Wei, X. , Sheng, Z. , Jiao, G. , Tang, S. , Luo, J. and Hu, P. (2016) Polycomb protein OsFIE2 affects plant height and grain yield in rice. PLoS One, 11, e0164748. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu, X. , Yang, C.Y. , Miao, R. , Zhou, C.L. , Cao, P.H. , Lan, J. , Zhu, X.J. et al. (2018) DS1/OsEMF1 interacts with OsARF11 to control rice architecture by regulation of brassinosteroid signaling. Rice (N Y). 11, 46. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu, X. , Zhou, S. , Wang, W. , Ye, Y. , Zhao, Y. , Xu, Q. , Zhou, C. et al. (2015) Regulation of histone methylation and reprogramming of gene expression in the rice inflorescence meristem. Plant Cell, 27, 1428–1444. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Metzger, D. , Scheer, E. , Soldatov, A. and Tora, L. (1999) Mammalian TAF(II)30 is required for cell cycle progression and specific cellular differentiation programmes. EMBO J. 18, 4823–4834. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mori, M. , Nomura, T. , Ooka, H. , Ishizaka, M. , Yokota, T. , Sugimoto, K. , Okabe, K. et al. (2002) Isolation and characterization of a rice dwarf mutant with a defect in brassinosteroid biosynthesis. Plant Physiol. 130, 1152–1161. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morinaka, Y. , Sakamoto, T. , Inukai, Y. , Agetsuma, M. , Kitano, H. , Ashikari, M. and Matsuoka, M. (2006) Morphological alteration caused by brassinosteroid insensitivity increases the biomass and grain production of rice. Plant Physiol., 141, 924–931. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ning, J. , Zhang, B. , Wang, N. , Zhou, Y. and Xiong, L. (2011) Increased Leaf Angle1, a Raf‐Like MAPKKK that interacts with a nuclear protein family, regulates mechanical tissue formation in the lamina joint of rice. Plant Cell, 23, 4334–4347. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nogales, E. , Louder, R.K. and He, Y. (2017) Structural insights into the eukaryotic transcription initiation machinery. Annu. Rev. Biophys. 46, 59–83. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qiao, S.L. , Sun, S.Y. , Wang, L.L. , Wu, Z.H. , Li, C.X. , Li, X.M. , Wang, T. et al. (2017) The RLA1/SMOS1 transcription factor functions with OsBZR1 to regulate brassinosteroid signaling and rice architecture. Plant Cell, 29, 292–309. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reeves, W.M. and Hahn, S. (2005) Targets of the Gal4 transcription activator in functional transcription complexes. Mol. Cell. Biol. 25, 9092–9102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rojo Niersbach, E. , Furukawa, T. and Tanese, N. (1999) Genetic dissection of hTAFII130 defines a hydrophobic surface required for interaction with glutamine‐rich activators. J. Biol. Chem. 274, 33778–33784. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sakamoto, T. , Morinaka, Y. , Ohnishi, T. , Sunohara, H. , Fujioka, S. , Ueguchi Tanaka, M. , Mizutani, M. et al. (2006) Erect leaves caused by brassinosteroid deficiency increase biomass production and grain yield in rice. Nat. Biotech. 24, 105–109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sekiguchi, T. , Nohiro, Y. , Nakamura, Y. , Hisamoto, N. and Nishimoto, T. (1991) The human CCG1 gene, essential for progression of the G1 phase, encodes a 210‐kilodalton nuclear DNA‐binding protein. Mol. Cell. Biol. 11, 3317–3325. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shi, Z. , Wang, J. , Wan, X. , Shen, G. , Wang, X. and Zhang, J. (2007) Over‐expression of rice OsAGO7 gene induces upward curling of the leaf blade that enhanced erect‐leaf habit. Planta, 226, 99–108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shimada, A. , Ueguchi‐Tanaka, M. , Sakamoto, T. , Fujioka, S. , Takatsuto, S. , Yoshida, S. , Sazuka, T. et al. (2006) The rice SPINDLY gene functions as a negative regulator of gibberellin signaling by controlling the suppressive function of the DELLA protein, SLR1, and modulating brassinosteroid synthesis. Plant J. 48, 390–402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Song, Y. , You, J. and Xiong, L. (2009) Characterization of OsIAA1 gene, a member of rice Aux/IAA family involved in auxin and brassinosteroid hormone responses and plant morphogenesis. Plant Mol. Biol. 70, 297–309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tamada, Y. , Nakamori, K. , Nakatani, H. , Matsuda, K. , Hata, S. , Furumoto, T. and Izui, K. (2007) Temporary expression of the TAF10 gene and its requirement for normal development of Arabidopsis thaliana . Plant Cell Physiol. 48, 134–146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tanabe, S. , Ashikari, M. , Fujioka, S. , Takatsuto, S. , Yoshida, S. , Yano, M. , Yoshimura, A. et al. (2005) A novel cytochrome P450 is implicated in brassinosteroid biosynthesis via the characterization of a rice dwarf mutant, dwarf11, with reduced seed length. Plant Cell, 17, 776–790. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tang, N. , Ma, S. , Zong, W. , Yang, N. , Lv, Y. , Yan, C. , Guo, Z. et al. (2016) MODD mediates deactivation and degradation of OsbZIP46 to negatively regulate ABA signaling and drought resistance in rice. Plant Cell, 28, 2161–2177. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tong, H. and Chu, C. (2018) Functional specificities of brassinosteroid and potential utilization for crop improvement. Trends Plant Sci. 23, 1016–1028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tong, H. , Jin, Y. , Liu, W. , Li, F. , Fang, J. , Yin, Y. , Qian, Q. et al. (2009) DWARF AND LOW‐TILLERING, a new member of the GRAS family, plays positive roles in brassinosteroid signaling in rice. Plant J. 58, 803–816. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tong, H. , Liu, L. , Jin, Y. , Du, L. , Yin, Y. , Qian, Q. , Zhu, L. et al. (2012) DWARF AND LOW‐TILLERING acts as a direct downstream target of a GSK3/SHAGGY‐Like kinase to mediate brassinosteroid responses in rice. Plant Cell, 24, 2562–2577. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang, L. , Wang, Z. , Xu, Y. , Joo, S.‐H. , Kim, S.‐K. , Xue, Z. , Xu, Z. et al. (2009) OsGSR1 is involved in crosstalk between gibberellins and brassinosteroids in rice. Plant J. 57, 498–510. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Waterworth, W.M. , Drury, G.E. , Hunter, G.B. and West, C.E. (2015) Arabidopsis TAF1 is an MRE11‐interacting protein required for resistance to genotoxic stress and viability of the male gametophyte. Plant J. 84, 545–557. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu, C.Y. , Trieu, A. , Radhakrishnan, P. , Kwok, S.F. , Harris, S. , Zhang, K. , Wang, J.L. et al. (2008) Brassinosteroids regulate grain filling in rice. Plant Cell, 20, 2130–2145. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xin, P. , Yan, J. , Fan, J. , Chu, J. and Yan, C. (2013) An improved simplified high‐sensitivity quantification method for determining brassinosteroids in different tissues of rice and Arabidopsis . Plant Physiol. 162, 2056–2066. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamamuro, C. , Ihara, Y. , Wu, X. , Noguchi, T. , Fujioka, S. , Takatsuto, S. , Ashikari, M. et al. (2000) Loss of function of a rice brassinosteroid insensitive1 homolog prevents internode elongation and bending of the lamina joint. Plant Cell, 12, 1591–1606. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yuan, Y.W. and Wessler, S.R. (2011) The catalytic domain of all eukaryotic cut‐and‐paste transposase superfamilies. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA, 108, 7884–7889. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, L. , Cheng, Z. , Qin, R. , Qiu, Y. , Wang, J.L. , Cui, X. , Gu, L. et al. (2012) Identification and characterization of an epi‐allele of FIE1 reveals a regulatory linkage between two epigenetic marks in rice. Plant Cell, 24, 4407–4421. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, S.W. , Li, C.H. , Cao, J. , Zhang, Y.C. , Zhang, S.Q. , Xia, Y.F. , Sun, D.Y. et al. (2009) Altered architecture and enhanced drought tolerance in rice via the down‐regulation of Indole‐3‐Acetic Acid by TLD1/OsGH3.13 activation. Plant Physiol. 151, 1889–1901. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, S. , Wu, T. , Liu, S. , Liu, X. , Jiang, L. and Wan, J. (2016) Disruption of OsARF19 is critical for floral organ development and plant architecture in rice (Oryza sativa L.). Plant Mol. Biol. Rep. 34, 748–760. [Google Scholar]

- Zhao, S.Q. , Hu, J. , Guo, L.B. , Qian, Q. and Xue, H.W. (2010) Rice leaf inclination2, a VIN3‐like protein, regulates leaf angle through modulating cell division of the collar. Cell Res. 20, 935. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhu, X. , Liang, W. , Cui, X. , Chen, M. , Yin, C. , Luo, Z. , Zhu, J. et al. (2015) Brassinosteroids promote development of rice pollen grains and seeds by triggering expression of Carbon Starved Anther, a MYB domain protein. Plant J. 82, 570–581. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Figure S1. Organ size comparison between pow1 and WT. Bars = 2 cm for (a), 5 cm for (b), 2 cm for (c), 2 mm for (d) and (e), and 500 μm for (f).

Figure S2. Comparison of the inner epidermal cells of the lemma between pow1 and WT. Spikelets at the grain filling stage were sampled (n = 10). Bars = 50 μm. **: p < 0.01 (Student’s t test).

Figure S3. Histological analysis of lamina joint. (a) and (c) represent sections before the leaf angle forms, and (b) and (d) represent sections after the leaf angle forms. Red double‐headed arrows in (a) and (b) indicate the adaxial cell of lamina joint. In (c) and (d), left side of each section is the adaxial side of lamina joint. Bars = 100 μm.

Figure S4. Genetic certification of the cause gene of the pow1 mutant. (a) The target site designed for knocking out the POW1 gene by CRISPR/Cas9 system and amino acid sequence comparison between POW1‐KO and WT. (b) Expression analysis of POW1 in the POW1‐OE transgenic plant. Young inflorescences of 2 mm long were sampled. Actin was used as the internal control. The transcript level was normalized against WT, which was set to 1. Data are means ± SD (n = 3).***: p < 0.001. (c,d) Comparison of grain size (c) and leaf angle (d) among pow1, WT, pow1‐C, POW1‐KO and POW1‐OE plants. Three independent POW1‐OE transgenic lines with similar expression level were selected for phenotypic measurement. Data are means ± SE (n = 30). Bars followed by different letters represent significant difference at 5%.

Figure S5. Phylogenetic analysis of rice putative PIF/Harbinger class transposases. Bar indicates branch length.