Abstract

The road to universal health coverage depends on resources committed to the health sector. In many cases, the political structure and strength of advocacy play an important role in setting budgets for health. However, this has, until recently, not been of interest to health system researchers and policymakers. In this study, we document the political path to the establishment of the Ghana National Health Insurance Scheme (NHIS) as well as continuous political interest in the scheme. To achieve our objectives, we used qualitative data from interviews with key stakeholders. These include stakeholders instrumental in the design and establishment of the NHIS. We also reviewed party manifestoes from the two main political parties in the country. Promises relating to the NHIS were extracted from the various manifestos and analysed. Other documents that account for the design and implementation of the scheme were reviewed. We found that the establishment of the NHIS was down to political commitment and effective engagement with relevant stakeholders. It was considered a solution to the political promise to remove user fees and make healthcare accessible to all. A review of the manifestos shows that in almost every election year after the NHIS was established, there has been some promise related to improving the scheme. There were several policy propositions repeated in different election years. The findings imply that advocacy to get health financing on the political agenda is crucial. This should start from the development of party manifestos. It is important to also ensure that proposed party policies are consistent with national priorities in the medium to long term.

Keywords: Health insurance, political economy, health financing, Ghana, universal health coverage

Key messages.

Political power and position played an important role in the design and establishment of the Ghana National Health Insurance Scheme (NHIS).

We find that engaging key political actors at early stages of the scheme’s design and implementation was critical for its establishment.

The implementation of the NHIS also highlights how policy reforms that ensure collaboration across all relevant government ministries and agencies are more likely to succeed.

To ensure sustainability of health financing reforms, continuous political interest is important.

Introduction

Universal health coverage (UHC) has become an important public health priority in recent years. The World Health Organization (WHO) defines UHC as ‘ensuring that all people have access to needed health services (including prevention, promotion, treatment, rehabilitation and palliation) of sufficient quality to be effective while also ensuring that the use of these services does not expose the user to financial hardship’ (WHO, 2020). The relevance of this global health priority was reiterated by its inclusion in the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs). The good health and well-being target under goal three of the SDGs seeks to ‘Achieve universal health coverage, including financial risk protection, access to quality essential health-care services and access to safe, effective, quality and affordable essential medicines and vaccines for all’ (UNDP, 2020). This target has received global support with majority of countries signing up to the SDGs and UN resolution on UHC.

The need for financial protection for health and UHC is even more pressing in developing countries. Available estimates from Wagstaff et al. (2018) suggest that at 10% threshold, Africa has the third highest (∼10.3%) incidence of catastrophic health spending after Asia (at 12.2%), Latin America and the Caribbean (at 17.5%). Moreover, health outcomes are also relatively poor in Africa, with relatively high mortality and morbidity rates. For instance, in sub-Saharan Africa, under-five mortality was estimated to be 78 per 1000 live births in 2019, relative to a global average of 38.8 per 1000 live births (World Bank, 2019). Similarly, life expectancy at birth was relatively lower in the region (61 years) compared to the global average of 72.38 years in the same year (World Bank, 2019). Health infrastructure and workforce is also reported to be deficient in the region compared to other regions of the world.

Over the years, different policies have been implemented in different countries across Sub-Sahara Africa (SSA) to improve financial protection for health and UHC. These include policies that allow people to pay into a pool while healthy and access healthcare when sick. These pooled funds come from taxes or health insurance contributions with many countries mixing the two (WHO, 2008). For instance, in countries like Ghana and Rwanda, health insurance schemes have been established to ensure that registered individuals do not face financial risk when they seek healthcare. In other countries like Kenya, Zambia and Malawi, social protection programmes (such as cash transfers) have been used to support vulnerable and poor individuals to improve their livelihoods as well as access to and utilization of healthcare. However, these are still insufficient as a significant proportion of the populations remain vulnerable to catastrophic out-of-pocket (OOP) spending on health (Wagstaff et al., 2018).

Moreover, the success of any programme directed towards financial protection and UHC hinges on sufficient and sustainable financing. In practice, however, government budgets across these countries face large competing interests from other equally important social and economic interventions aside health. Given that resources are typically limited, the decision to channel these resources to particular sectors is important. The role of political actors in this decision process cannot be overemphasized. Indeed, resource allocation to UHC and financial protection for health has been described as an important political process (Chemouni, 2018).

In Ghana, significant progress has been made towards improving financial protection and UHC. The country is considered one of the first to implement a tax-funded health insurance scheme aimed at improving medical care utilization and reducing OOP health spending. The National Health Insurance Scheme (NHIS) is estimated to currently cover ∼40% of the population and is touted as the largest single reform in the health sector of Ghana. It is worth noting that majority of the population remain uncovered under the scheme even though it is largely publicly funded. Empirical studies have shown some gains for those who are covered, including increased utilization (Blanchet et al., 2012; Sekyi and Domanban, 2012; Wang et al., 2017; Abrokwah et al., 2019), equity in health financing (Jehu-Appiah et al., 2011; Odeyemi and Nixon, 2013) and reduced OOP payments (Okoroh et al., 2018; Dalaba et al., 2014). However, the political process towards the establishment of the scheme has been missing in the literature. In this paper, we seek to highlight the political paths towards the establishment of the NHIS in Ghana. We also assess continuous political interest in the scheme. The relevance of this lies in the fact that while the NHIS is at the heart of the healthcare system in Ghana, different political interests by different parties can affect the scheme in achieving the desired outcome.

Understanding the political economy of health policy reforms will help policymakers circumvent challenges in the reform process. Importantly, engaging these actors early ensures commitment at all stages of the reform and smoothens the process. We provide evidence from Ghana on how key political actors facilitated Ghana’s most important health financing reform and highlight lessons for future reforms in Ghana and across the developing world. We also highlight how political interest in the scheme has been sustained over the years.

Health financing and NHIS in Ghana

Attempts to reform health financing in Ghana dates back to post-independence. Public health financing was mostly designed for expatriate civil servants during the pre-independence era. The first attempt at UHC was between 1957 and 1969 where a universal access to comprehensive health services was tried. The approach was to tax-fund public health services at the point of use as well as rapidly expanding public health infrastructure and human resources. With the country’s relatively stable economic and political situation post-independence, this policy was considered feasible and sustainable. However, after depleting the country’s economic surplus and incidence of political instability, the policy became unsustainable and was abandoned. The poor economic outlook of the country resulted in the implementation of the structural adjustment programme (SAP) in the 1970s that limited public expenditure prospects.

In line with the SAP and concerns about the sustainability of tax-financed public health system, user fees were introduced in 1985 (Agyepong and Adjei, 2008). This was popularly known as the ‘cash and carry’ system where patients were required to pay upfront for health services before they were treated. This resulted in a large proportion of the population being denied their basic healthcare needs. Coupled with the high poverty and inequality levels, paying for healthcare out of pocket before receiving service was a major concern for the government and population at large. To ameliorate this, community-based mutual health insurance schemes were introduced in the 1990s with financial and technical support from development partners (Agyepong and Adjei, 2008; Blanchet and Acheampong, 2013). This was designed to reduce the financial burden from seeking healthcare and to improve utilization. However, OOP payments for health persisted in the early 2000s, and utilization of health services was low.

In 2003, the NHIS was established and operationalized in 2004. The NHIS, operated by the National Health Insurance Authority (NHIA), was designed with three key objectives: (1) increase population coverage, (2) reduce user fees and cost sharing and (3) increase access to service, coverage and utilization. The scheme was established by an Act of parliament (ACT 650, Amended ACT 852). The scheme was originally designed to amalgamate district mutual health insurance schemes operating in the country at the time. The district schemes limited health access in the sense that healthcare could only be accessed within the district of operation. The NHIS was not initially designed as a mandatory scheme until 2012 when ACT 852 required that enrolment be made mandatory. However, this provision has not been strictly implemented as majority of the population are still not enrolled on the scheme, due to the large informal base of the economy. As at 2019, the scheme covered ∼12 million people, which is ∼40% of the national population (NHIA, 2020).

A key feature of the scheme is its financing structure. The scheme is largely tax-funded through the National Health Insurance Levy (NHIL). The NHIL forms 2.5% of all value-added tax (VAT) revenue received. This is the largest source of revenue to the NHIA. Other sources of revenue include 2.5% of Social Security and National Insurance Trust (SSNIT) contributions, interest on investments and premium payments. Parliamentary allocations, grants, donations, gifts/voluntary contributions also serve as revenue sources to the scheme.1 While the scheme does not cover all health conditions, it is reported that ∼95% of disease conditions reported at health facilities are covered in the benefit package.2

All residents of Ghana, including non-citizens, are eligible to enrol on the NHIS scheme, even though not all of them are required to pay premiums and/or processing fees. Contributors to SSNIT do not pay premiums. Exemptions of the scheme include pregnant women, beneficiaries of the Livelihood Empowerment Against Poverty programme and indigents. These are completely exempted from paying premiums and processing fees. They, however, need to register and hold a valid NHIS card. Besides, children below the age of 18 years and the elderly above 70 years are only required to pay processing fees and not premiums (NHIA, 2012). The informal sector constitutes the only fee-paying membership category and, as at 2019, they make up ∼34% of the membership (NHIA, 2020).

Methods

Conceptual framework

The study follows a framework proposed by Sparkes et al. (2019) on the political economy of health financing reforms. The authors argue that successful health financing reforms require a clear understanding of the power and position of key political actors. The framework highlights key stakeholders that could influence the implementation of financing reforms. The framework identifies six important stakeholders that are considered to be key actors in health financing reforms. Engaging these actors can guide policymakers in identifying and effectively addressing challenges that may arise in the reform process. These six actors are (1) interest group politics, (2) bureaucratic politics, (3) budget politics, (4) leadership politics, (5) beneficiary politics and (6) external actor politics. Interest group politics is defined to include stakeholders with shared interests and power to influence political authorities as well as the policy process. In the context of the NHIS, these groups would include the Ghana Medical Association, Christian Health Association of Ghana, Nurses and Midwives Council as well as Trade Union Congress (TUC). These associations typically influence the health policy in Ghana. Bureaucratic politics on the other hand highlights the need to ensure proper coordination across various government agencies to ensure that proposed policies are acceptable. For instance, in many cases, health financing reforms require commitments from ministries of finance to ensure that budgetary allocations for the new reform are feasible and sustainable.

Budget politics is closely related to bureaucratic politics and emphasizes the need to recognize that budgetary allocations are important political processes. Decisions on what gets onto the budget and what share of the budget is allocated to what sector are influenced by political power. Hindriks and Myles (2013) also demonstrated that policies that are high on the political agenda will most often receive a higher preference in the budgetary process.

Leadership politics represents the commitment of political leaders. A typical feature in public policy is the acceptability of the head of state. If the political leader considers the reform important, its chances of success are usually very high. Aside the head of government, other leaders in the various arms of the government (Legislature and Judiciary) are also crucial to the success of the policy.

Beneficiary politics concerns the people and they cannot be overlooked. In some cases, if the will of the people is very strong, policies are forced onto the political agenda and become priorities. Political leaders know their mandate is determined by the people and therefore are committed to ensuring their needs are met, even if partially. Therefore, health financing reforms are likely to benefit from public mobilization that demonstrates that a particular reform is a priority to the population at large.

External actor politics is also an important part of the political process to consider. While external actors such as donors and development partners may not be obvious stakeholders in health financing reforms, their power and position make them very relevant. Sparkes et al. (2019) noted that external actors influence reform processes through their financial condition, intellectual influences and incentives. The authors also note that the extent of influence depends on the political environment of the country.

In Figure 1, we present the framework discussed above. In addition to the discussion so far, the framework also highlights the fact that these actors also interact among themselves to finally influence public policy. That is, while it is possible for the individual actors to separately influence public policy, a more practical approach allows partners to negotiate, resolve conflicts, form alliances and build consensus that jointly influences policy. This is depicted in the figure with arrows that connect the various actors.

Figure 1.

Analytical framework of interaction across political actors.

Source: Authors’ construct.

Analytical approach

To answer our research questions, we relied on qualitative research techniques and used a combination of stakeholder interviews as well as a desk review of relevant documents. We began by identifying stakeholders that were instrumental in the design and initial implementation stages of the NHIA in Ghana. A total of 10 stakeholders were interviewed. The interview covered relevant topics including a historical recollection of the establishment of the scheme, how the idea of having a publicly funded insurance scheme started and which stakeholders were instrumental in this process. Also, the interviewed stakeholders were asked to highlight challenges encountered during the design and implementation of the scheme. Interviews were recorded with the consent of respondents. Responses were transcribed and aggregated to ensure anonymity. Table 1 shows institutions from which individual stakeholders were sampled for interviews. We also reviewed various documents to highlight the contribution of various organizations to the design and implementation of the scheme. This was particularly relevant where such information was not available from the stakeholder interviews. For instance, to understand the role of the World Bank in the design of the scheme, we reviewed various historical reports on their activities during the commencement of the scheme.

Table 1.

Stakeholders interviewed and their relevance

| S. no. | Key stakeholders | Relevance |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Individual consultants | Involved in design of the scheme |

| 2 | NHIA head office | Scheme administrators |

| 3 | Ghana Revenue Authority (GRA) head office | Revenue collection for NHIF |

| 4 | Ministry of Finance (MoF) | Revenue collection for NHIF |

| 5 | Ministry of Health (MoH) | Parent ministry of NHIA |

To answer the second research question, we reviewed manifestos of the two largest political parties in Ghana. These political parties are the only parties to have ruled the country since 1992. Manifestos over three elections (2008, 2012 and 2016) were reviewed. The idea was to identify promises made on the NHIS in these manifestos. The presence of promises on the scheme suggests political interest in the scheme. Indeed, as mentioned earlier, political parties are likely to pursue policies aligned with their manifestos. The manifestos are also considered social contracts between the people and the parties and may be the basis for seeking re-election. It is important to note that the presence of NHIS-related promises in manifestos does not necessarily translate into implementation. Our approach therefore only attempts to measure political interest and not implementation.

Results

Leadership politics

Leadership politics, as mentioned earlier, highlights the role of policy acceptability by political leaders. Policies that are considered crucial by political leaders, in general, have better chances of implementation. In the case of Ghana, the evidence suggests that commitment to establishing the NHIS started even before an election was won by the government that eventually established the scheme. The message to start NHIS was carried in the party’s manifesto. The political leaders identified an important social need that would be popular among voters. At this time, health financing was largely out of pocket, and patients were required to make payments before care was provided. With high levels of poverty at the time, a significant proportion of the population was deprived of basic healthcare, and there was a desperate need for this trend to be reversed. A publicly funded insurance scheme was therefore going to be very timely. This point was clearly noted by the stakeholders interviewed.

The idea of a National Health Insurance Scheme started with political elections. Political manifestos carried the idea (respondent, NHIA).

Another aspect of the establishment of the scheme that benefited from political leadership was the need to identify sustainable sources of funding for the scheme. It was revealed during the stakeholder interviews that the new government at the time faced an International Monetary Fund (IMF) obligation that required that taxes be increased. The objective of this requirement was to raise additional revenues to shore up the country’s growing debt levels. The move to increase tax had, however, been vehemently opposed in the past. Indeed, the new government, that was in opposition at the time, also opposed the policy and led various demonstrations to this effect. It was therefore difficult for the same government that opposed a tax increase to turn around and increase taxes when it got into power. The NHIS, therefore, was a good way to introduce the tax. Once the revenue from the tax increase was tied to a policy that was considered to be timely, the tax increase could not be resisted. Typically, the then government that suffered initial resistance would have resisted the tax increase now, at least, for political equalization. However, even they could not resist the new tax increase only because it was going to be used to fund the NHIS.

…The new government decided that one way to both meet IMF obligations and achieve a political goal is by using the money for a very popular measure like the NHIS and a manifesto promise instead of adding it to the general VAT which would have been opposed again. This was a politically safer way to introduce the VAT and it turned out to be so as no one opposed it (respondent, consultant).

Bureaucratic politics

The establishment of the NHIS also benefited from some bureaucratic politics. This was related to the need to engage with internal and external actors that could influence the outcome of the policy. One of such actors was the IMF. It is expected that a social intervention of this magnitude supported by public funding was going to have a significant economic consequence. Coupled with the fact that the country was transitioning as a highly indebted poor country and the resource limitations, it was easy to understand this would not be easily sanctioned by external actors like the World Bank (WB) and IMF. It was feared that the policy would add to the already fragile economic landscape at the time and create rigidities. It was, therefore, important that negotiations were made to get the support of these actors.

Development partners did not oppose the tax. Their problem was rather with the design of the scheme and the straight forward abolishment of the user fees (on IMF and WB) (respondent, NHIA).

The role of the development partners also transcends their concerns about the fiscal sustainability of the scheme. Effective engagement and negotiation with external actors resulted in significant support in the form of technical and financial assistance. Development partners that supported the NHIS in diverse ways include the International Labour Organization (ILO), The World Bank, the IMF, German Agency for International Cooperation (GIZ), Royal Netherlands Embassy, United States Agency for International Development (USAID), Danish International Development Agency (DANIDA), European Union (EU) and the WHO, among others.

A review of existing literature suggests that the ILO for instance provided assistance in testing methodologies that will enable extending health insurance coverage to the poor through the Ghana Social Trust Pre-Pilot Project (ILO, 2005). It was also reported that the ILO provided significant assistance in the actuarial analysis of the NHIS budget and also strengthened the capacity of the National Health Insurance Council in the actuarial analysis (World Bank, 2007). Similarly, the World Bank through various interventions provided technical and financial support to strengthen the capacity of staff at the NHIA as well as ensure fiscal sustainability. Specifically, components of the scheme that were supported by the world bank include policy analysis and design, governance and accountability mechanisms, management and administrative capacity as well as purchasing of priority health services (World Bank, 2007).

It is important to note that these development partners had also been involved in the development of community health insurance (CHI) schemes (also known as Mutual Health Organizations) before the start of the national scheme. For instance, EU, WHO-AFRO, DANIDA and USAID (through the Partnership for Health Reform Plus) were key in the start and sustainability of these CHI schemes (Agyepong and Adjei, 2008; Blanchet and Acheampong, 2013).

Aside the external actors, there were also internal actors that needed to be consulted. One of such actors is Trades Union Congress (TUC). As mentioned earlier, contributions of members of SSNIT were part of the sources of funding for the scheme. By design it was required that 2.5% of SSNIT contributions are earmarked for the NHIS. This was to allow for SSNIT contributors to be automatic members of the scheme. However, this attracted some resistance from the union of workers. Their main concern was the fact that the contributions from the SSNIT fund would jeopardize their sustainability. Some of the interviewed stakeholders noted that there was a need for the government to reach a compromise with the leadership of the union. Indeed, some respondents considered this compromise to be ‘fatal’. The compromise was for the government to guarantee that it was ready to absorb any revenue shortfalls that SSNIT would face due to their contributions to the NHIS. While this may suggest desperation on the part of the government, it also shows the strong commitment towards UHC.

Sustainability of the pension’s fund. This was so because there was an actuarial study to show that despite the transfer of the 2.5%, the fund will remain stable until 2035 (on TUC opposition) (respondent, NHIA).

… the government made that fatal commitment to guarantee the pension fund in its entirety against any short fall as a result of the 2.5% transfer from SSNIT contributions. The guarantee was on the basis that if there exists a sustainability problem as a result of the transfer, government will absorb it. So the guarantee was for after 2035 if the shortfall occurs according to the actuarial study (respondent, consultant).

Budget politics

Budget politics, as described in the framework, also manifested in the establishment of the NHIS. From the beginning, there was a need to ensure that responsible financial agencies were on board the policy process. While this was largely a policy under the purview of the Ministry of Health (MoH), the Ministry of Finance (MoF) was an important actor and could not be left out at any point. The need to ensure understanding and commitment across the ministries was important. Typically, public policies are only sector-specific and do not consider collaborative efforts from related sectors. Indeed, this problem was succinctly highlighted by one of the respondents who made reference to the case of Kenya. It was noted that while Kenya’s MoH managed to get a health financing reform law passed by parliament, the MoF did not consider the policy to be feasible and did not support it. It was obvious that in the case of Kenya, there was not enough inter-ministerial engagement. In the case of the NHIS, however, the MoF was on board from the very beginning. The Ghana Revenue Authority (GRA), which is also an agency under the MoF, was also involved. These institutions are central to the collection and allocation of tax revenues earmarked for the scheme.

…Having the MOF on board from the word go was key in getting the financing issues sorted out. In contrast to Kenya when a similar process was initiated in 2009 by the MoH without the MoF. The law was passed by parliament of Kenya but was rejected by the President and the MoF denounced the law publicly. This emphasizes the need for inter-ministerial approach to dealing with a policy such as this (respondent, consultant).

For instance, one of the respondents from GRA noted that earmarking revenues for the NHIS may have created rigidities in the budget. Typically, the MoF would prefer revenues collected in a common pool for allocation. However, the MoF also acknowledges the importance of the scheme and was involved in its design from the beginning. There was therefore no room for agitations and reluctance to earmark funds for the scheme. Also, given that the NHIS was a national programme with significant interest, resources will be allocated whether through earmark or general revenues. This illustrates the importance of budget politics in the implementation of policies and programmes.

It has performed well as per its purpose. But lately there has been rigidities in government expenditure and as such the MOF has been agitating for revenues to be collected and put in a pool for spending rather than the earmarks (respondent, GRA)

…there is no difference between earmarked and general revenue once the earmarked revenue is considered a priority by the government (respondent, GRA).

Continuous political interest in NHIS: a review of party manifestos

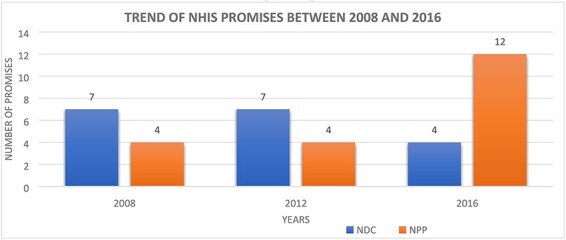

We now turn our focus to assess political interests in the NHIS over the years. As mentioned earlier, we achieved this objective by evaluating manifestos of the two main political parties in Ghana. Since the establishment of the scheme, these are the only political parties to have won power. Figure 2 plots the number of individual manifesto promises related to the NHIS. These statistics are plotted over 3 election years (2008, 2012 and 2016). The figure shows that in 2008, the National Democratic Congress (NDC) made at least seven promises related to the NHIS compared to four from the New Patriotic Party (NPP). A similar trend was observed in 2012. The trend was however reversed in 2016 where we identified 12 promises for the NPP compared to 4 from the NDC. While we do not intend to suggest any correlation, it is interesting to mention that for each of these elections, the party with the highest number of promises on NHIS emerged victorious.

Figure 2.

Trend of the NHIS promises between 2008 and 2016.

Source: Party manifestos for various years.

In Table 2, we present some of the specific promises identified in the manifestos. The examples provide some insights into the need for policy options to commence with mani festo promises. As mentioned earlier, it is important for the health sector to ensure that appropriate reforms are captured in party manifestos. It is also important to ensure that these promises are clear with specific targets stated. This makes it easier to assess whether targets were achieved and respective political parties can be held responsible. It can be observed from the table that for many of these promises, there are no clear targets against which achievements can be assessed. For instance, promises like ‘improve the NHIS to extend access to health services’ or ‘the NHIS will be enhanced and preventive medicine emphasized’ do not indicate exactly what policy targets will be pursued. Another observation from this table is the fact that there are similarities in promises across parties and over time.

Table 2.

Examples of specific party promises in manifestos

| Year | NPP | NDC |

|---|---|---|

| 2008 | The NHIS will be enhanced and preventive medicine emphasized (2008) | Improve the NHIS to extend access to health services (2008) |

| 2008 | The NPP government will continue to expand the parameters of the NHIS by identifying the poor and the destitute to provide them with NHIS cover, improving the administrative efficiency and efficacy of the scheme and moving systematically towards Universal Health Insurance (2008) | Review and streamline the system according to its mandate and core objectives to ensure a national health insurance scheme as opposed to district health insurance schemes (2008) |

| 2012 | We will revive and restore confidence in the NHIS and achieve universal coverage for all Ghanaians (2012) | Further strengthen the NHIS in terms of both coverage and effectiveness and administrative and operational efficiency in accordance with provisions of the new legislation currently before Parliament (2012) |

| 2016 | Utilizing the best in technology and health insurance management protocols to tackle waste, corruption and insurance claim fraud under the NHIS (2016) | Improve efficiency in the provider payment mechanisms and roll out capitation nationwide (2012) |

| 2016 | Revive the National Health Insurance Scheme to make it efficient, with capacity to finance health services on a timely basis in a bid to achieve universal health coverage for all Ghanaians (2016) | Improve access to quality healthcare by continuing to register vulnerable persons including indigents, ‘kayayei’, prisoners, persons in witches camp, aged persons and persons with disability on NHIS (2016) |

Discussion

In this study, we sought to document the political path to UHC in Ghana through the establishment of the NHIS. This is important for several reasons; first, health policymakers have over the years considered politics and political economy to be external to their activities (Campos and Reich, 2019). This paper highlights why early political engagements and securing political interest are crucial for any public policy (Campos and Reich, 2019a; Chemouni, 2018; Onoka et al., 2015). This study is also relevant in the sense that while several aspects of the process of establishing the NHIS have been well documented, there is no study that documents political economic aspects of the scheme. Moreover, given recent calls for countries across developing countries to follow the lead of their counterparts that have established insurance schemes, these lessons can be leveraged.

To achieve the research objectives, we pursue qualitative techniques. First, we looked at the political actors and powers that influenced the process of establishing the scheme. We identified some of the challenges encountered in the process and the need for engaging relevant stakeholders to resolve these challenges. This part of the objective was achieved through stakeholder interviews and desk reviews to reflect on events leading to the establishment of the scheme. Stakeholders who were directly involved in the design and establishment of the scheme were identified and interviewed. The second part of the study looked at the need to sustain the political momentum that started the design and implementation of the scheme. We considered this analysis to be important as policies that are not backed by political power may not be sustainable. Again, we pursued this objective by reviewing party manifestos and extracting promises on the NHIS over time.

The findings highlight the need to broaden the scope of stakeholders to be engaged in the process of policy reforms of this nature. The popular approach of designing reforms only within the host ministries/agencies may not be effective. Such one-sided policies are difficult to implement as agencies that are ignored at the design stage do not feel obliged to commit to the reform. In the case of the NHIS, all relevant stakeholders were engaged at the design stage. This allowed for all misunderstandings and disagreements to be resolved at the initial stages. In some cases, there was the need for compromise across stakeholders. Indeed, this is another important lesson for policy reforms in the public sector: the need for compromise. In practice, it is difficult to keep all stakeholders happy in any policy reform process. Where compromises are possible, it is important to explore this option.

The study also highlighted the need for continuous political interest in health financing reforms Particularly for reforms that have a significant impact on the population, the urge to sustain it is important. The fact that the NHIS has appeared in almost every manifesto of the key political parties is a positive indication of interest from political powers. Indeed, in some of these election years, the performance of the NHIS has been instrumental to the success or failure of political parties in presidential elections.

However, merely mentioning the scheme in a manifesto may not be sufficient. It is important to ensure that these promises are precise and measurable. Political parties should be held responsible for the promises they make. To achieve this, there must be clarity on the specific promises and whether they are achievable. It is also important for political parties to engage the appropriate stakeholders in the process of deciding what enters the manifestos. In this case, it would be appropriate for manifestos to reflect development strategies of the NHIA. It will be more helpful if the promises are in line with the specific targets of the NHIA.

In a more general sense, the findings of this study provide important lessons for health policymakers. It highlights the strong connection between political powers and the success of policy efforts. It is inevitable to ignore political economic aspects of policies and the potential influence on the success of these policies. Policymakers in the health sector need to recognize these dynamics and take advantage of the same. Another lesson that emerges is the need to consult widely across political actors. While policymakers sometimes wait until elections are won, it sometimes pays to start consultations even before elections. Both political actors in power and in opposition should be consulted and reform options discussed. In the case of the NHIS, it was important that the discussion started even before power was won.

There are a few limitations of the study that are worth mentioning. First, the study was limited in the number of actors interviewed. For instance, in assessing the role of developing partners (including the IMF and WB), we only relied on desk reviews. There are also some civil society organizations (CSOs), labour unions and individuals whose contributions are not explicitly captured in our study. Second, the study was limited in attempting to assess the political commitment to the sustainability of the scheme. An ideal approach would have been to assess whether manifesto messages were actually implemented. This was however difficult as some of these messages were rather vague without clear indicators for assessment. In this study, we therefore only assess continuous political interest in the scheme and not the actual implementation of these promises. Based on these, we recommend that future studies consider extending interviews to include development partners, individuals, labour unions and CSOs who were influential in the establishment of the scheme. Future studies can also focus on assessing the actual implementation of party manifestos related to the NHIS.

Conclusion

The study highlights the political economic path towards the establishment of health financing reforms. Using the NHIS in Ghana as a case study, we interviewed selected stakeholders to understand how various actors engaged in the design and implementation of the scheme. We also reviewed manifestos of the two main political parties in the country to appreciate the level of political interest in the scheme. The findings generally point to the fact that political power and position influence the design and implementation of public policy. The establishment of the NHIS was primarily determined by the commitment of political leaders. Broad engagement of both external and internal actors was also critical. Where there are disagreements across stakeholders, it is important to ensure acceptable compromise. Moreover, political momentum or interest must be sustained. In sum, policymakers in the health sector should ensure strong collaboration with political actors at all levels. This will be useful for more robust policy design and implementation.

Acknowledgements

We are grateful to staff and students of the Department of Economics, KNUST, for comments on an earlier version of the paper.

Endnotes

See http://www.nhis.gov.gh/about.aspx (accessed on 26 November 2020).

See http://www.nhis.gov.gh/benefits.aspx (accessed on 26 November 2020).

Contributor Information

Jacob Novignon, Department of Economics, Kwame Nkrumah University of Science and Technology, Kumasi, Ghana.

Charles Lanko, Department of Economics, Kwame Nkrumah University of Science and Technology, Kumasi, Ghana.

Eric Arthur, Department of Economics, Kwame Nkrumah University of Science and Technology, Kumasi, Ghana.

Data availability statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author, JN, upon reasonable request.

Funding

This study did not receive any funding. This paper was published as part of a supplement financially supported by International Development Research Centre.

Ethical approval

Ethical approval for this type of study is not required by our institute.

Conflicts of interest statement

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

References

- Abrokwah SO, Callison K, Meyer DJ. 2019. Social health insurance and the use of formal and informal care in developing countries: evidence from Ghana’s National Health Insurance Scheme. The Journal of Development Studies 55: 1477–91. [Google Scholar]

- Agyepong IA, Adjei S. 2008. Public social policy development and implementation: a case study of the Ghana National Health Insurance Scheme. Health Policy and Planning 23: 150–60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blanchet NJ, Acheampong OB. 2013. Building on Community-Based Health Insurance to Expand National Coverage: The Case of Ghana. Bethesda: Abt Associates Inc. https://www.hfgproject.org/building-on-community-based-health-insurance-to-expand-national-coverage-the-case-of-ghana/, accessed 1 June 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Blanchet NJ, Fink G, Osei-Akoto I. 2012. The effect of Ghana’s National Health Insurance Scheme on health care utilisation. Ghana Medical Journal 46: 76–84. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Campos PA, Reich MR. 2019. Political analysis for health policy implementation. Health Systems & Reform 5: 224–35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chemouni B. 2018. The political path to universal health coverage: power, ideas and community-based health insurance in Rwanda. World Development 106: 87–98. [Google Scholar]

- Dalaba MA, Akweongo P, Aborigo R. et al. 2014. Does the National Health Insurance Scheme in Ghana reduce household cost of treating malaria in the Kassena-Nankana districts? Global Health Action 7: 23848. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hindriks J, Myles GD. 2013. Intermediate Public Economics. Cambridge: MIT Press. [Google Scholar]

- ILO . 2005. Imrpoving Social Protection for the Poor: Health Insurance in Ghana. The Ghana Social Trust Pre-Pilot Project Final Report. ILO. [Google Scholar]

- Jehu-Appiah C, Aryeetey G, Spaan E. et al. 2011. Equity aspects of the National Health Insurance Scheme in Ghana: who is enrolling, who is not and why? Social Science & Medicine 72: 157–65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- NHIA (National Health Insurance Authority) . 2012. 2012 Annual Report. Accra: National Health Insurance Authority. [Google Scholar]

- NHIA (National Health Insurance Authority) . 2020. NHIS Active Membership Soars. Accra: National Health Insurance Authority. http://www.nhis.gov.gh/News/nhis-active-membership-soars-5282#:∼:text=Ghana’s%20National%20Health%20Insurance%20Scheme,over%2012%20million%20in%202019.&text=Ending%202019%2C%20the%20Informal%20sector,31.5%25%20in%20the%20previous%20year, accessed 20 March 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Odeyemi I, Nixon J. 2013. Assessing equity in health care through the national health insurance schemes of Nigeria and Ghana: a review-based comparative analysis. International Journal for Equity in Health 12: 1–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Okoroh J, Essoun S, Seddoh A. et al. 2018. Evaluating the impact of the national health insurance scheme of Ghana on out of pocket expenditures: a systematic review. BMC Health Services Research 18: 1–14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Onoka CA, Hanson K, Hanefeld J. 2015. Towards universal coverage: a policy analysis of the development of the National Health Insurance Scheme in Nigeria. Health Policy and Planning 30: 1105–17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sekyi S, Domanban PB. 2012. The effects of health insurance on outpatient utilization and healthcare expenditure in Ghana. International Journal of Humanities and Social Science 2: 40–9. [Google Scholar]

- Sparkes SP, Bump JB, Özçelik EA, Kutzin J, Reich MR. 2019. Political economy analysis for health financing reform. Health Systems & Reform 5: 183–94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- UNDP . 2020. Sustainable Development Goals. New York: United Nations Development Programme. https://www.undp.org/content/undp/en/home/sustainable-development-goals.html, accessed 20 March 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Wagstaff A, Flores G, Hsu J. et al. 2018. Progress on catastrophic health spending in 133 countries: a retrospective observational study. The Lancet Global Health 6: e169–79. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang W, Temsah G, Mallick L. 2017. The impact of health insurance on maternal health care utilization: evidence from Ghana, Indonesia and Rwanda. Health Policy and Planning 32: 366–75. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- WHO (World Health Organisation) . 2008. Toolkit on Monitoring Health Systems Strengthening: Health Systems Financing. Geneva: World Health organization. [Google Scholar]

- WHO (World Health Organisation) . 2020. Universal Health Coverage. Geneva: World Health Organisation. https://www.who.int/health-topics/universal-health-coverage#tab=tab_3, accessed 20 March 2021. [Google Scholar]

- World Bank . 2007. Ghana Health Insurance Project Appraisal Report. Washington, DC: World Bank. [Google Scholar]

- World Bank . 2019. World Development Indicators. Washington, DC: World Bank. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author, JN, upon reasonable request.