Abstract

Proteins contribute to cell biology by forming dynamic, regulated interactions, and measuring these interactions is a foundational approach in biochemistry. We present a rapid, quantitative in vivo assay for protein-protein interactions, based on optical cell lysis followed by time-resolved single-molecule analysis of protein complex binding to an antibody-coated substrate. We show that our approach has better reproducibility, higher dynamic range, and lower background than previous single-molecule pull-down assays. Furthermore, we demonstrate that by monitoring cellular protein complexes over time after cell lysis, we can measure the dissociation rate constant of a cellular protein complex, providing information about binding affinity and kinetics. Our dynamic single-cell, single-molecule pull-down method thus approaches the biochemical precision that is often sought from in vitro assays while being applicable to native protein complexes isolated from single cells in vivo.

Significance

Protein-protein interactions are of fundamental importance in biology. We report the development of an assay that can interrogate the abundance, dynamics, and stability of native protein complexes extracted from single cells. We show that this approach can be applied to Caenorhabditis elegans embryos, enabling measurement of the changes in protein complex dynamics in vivo during development. We have developed open-source software enabling application of this approach to any protein pair of interest that can be labeled and detected via single-molecule Total Internal Reflection Fluorescence (TIRF) microscopy.

Introduction

Protein-protein interactions are fundamental determinants of protein function. By interacting and forming complexes, proteins assemble macromolecular machines that carry out a myriad of activities within cells. A major goal of experimental biology is to observe, measure, and characterize these interactions and to understand how they are controlled and contribute to cell behavior.

For protein-protein interaction assays to be maximally informative, they should ideally be performed in vivo—that is, using natively expressed proteins engaged in their normal cellular functions. Unfortunately, traditional assays such as coimmunoprecipitation usually rely on protein overexpression and do not typically yield quantitative information about protein complex abundance or binding affinity. Therefore, investigators interested measuring quantitative binding parameters such as the dissociation constant (KD) or binding and unbinding rate constants (kon and koff) generally turn to in vitro approaches with purified proteins (1,2). Although such approaches provide an unparalleled degree of experimental control and can yield quantitative descriptions of protein-protein interactions, they may not always recapitulate the physiological state of the proteins under study.

In the past decade, technical advancements from our group (3) and others (4, 5, 6, 7) have begun to improve the potential of cell-based assays to yield quantitative information about protein complexes. A pioneering study from Jain and colleagues (4) showed that protein-protein interactions could be assayed in cell lysates by immunoprecipitating fluorescently tagged proteins onto microscope coverslips and imaging the resulting immunocomplexes using single-molecule TIRF microscopy, an approach termed single-molecule pull-down (SiMPull). Because SiMPull counts individual protein complexes, it can provide a digital, quantitative measurement of the fraction of proteins in complex in a given sample. Subsequent work from the Yoon lab (6,7) further developed this approach by pulling down a tagged protein and then adding a second cell lysate carrying a tagged binding partner; by monitoring these reactions over time, they were able to extract kinetic parameters describing the binding. However, the protein complexes studied in this approach were formed on the coverslip surface and thus did not represent native cellular interactions (6).

Building on this earlier work, we developed a method termed single-cell, single-molecule pull-down (sc-SiMPull) (3) for studying near-in vivo protein interactions from single-cell embryos. To develop this approach, we made three key changes to previous SiMPull approaches. First, we miniaturized SiMPull by lysing single cells inside nanoliter-volume microfluidic channels. Microfluidic lysis reduced the amount of input material required, enabling single-cell analysis. The microfluidic approach also allowed faster sample processing; samples were analyzed minutes instead of hours after lysis. Second, we developed and used genome editing technology (8,9) to insert fluorescent tags directly into the native genes encoding the proteins under study, eliminating the need for overexpression and ensuring that any protein complexes we detected were formed by endogenous proteins. Third, we developed freely available, user-friendly image analysis software that eliminates the need for manual counting of molecular complexes and enables a user to obtain data from hundreds to thousands of molecules per cell (3). Together, these improvements enabled us to detect changes in native protein complex abundance that occurred over the span of a few minutes during development of the Caenorhabditis elegans zygote (3). We showed that the PAR-3 protein, which is critical for embryonic cell polarization, is found in oligomers that dynamically assemble and disassemble during the first cell cycle. PAR-3 oligomerization cooperatively promotes its association with the key kinase aPKC and thereby enables aPKC transport to the anterior side of the cell to establish the anterior-posterior axis (3). Despite enabling these important molecular insights, our initial sc-SiMPull approach still had significant limitations. It relied on a manual mechanical method to lyse cells, hindering reproducibility and precise embryo staging. In addition, the time from cell lysis to data collection was still several minutes, which obscures kinetic information and precludes detecting weak or transient complexes that may dissociate within seconds after cell lysis.

Here, we further improve upon the sc-SiMPull approach by incorporating near-instantaneous, on-chip cell lysis by a pulsed infrared laser. We demonstrate that laser lysis is compatible with sc-SiMPull; it does not photobleach the fluorescent labels that are required for single-molecule imaging, nor does it detectably damage cellular protein complexes. We further show that by imaging captured protein complexes over time and monitoring their dissociation, we can measure the kinetics of protein complex dissociation and obtain important information about the stability of protein-protein interactions.

Materials and methods

Contact for reagent and resource sharing

Requests for resources and further information should be directed to and will be fulfilled by the lead contact, Daniel J. Dickinson (daniel.dickinson@austin.utexas.edu).

Experimental model and subject details

C. elegans strains were fed Escherichia coli strain OP50 and maintained on nematode growth medium (NGM) at 20°C. The HaloTag-only control strain used in Fig. S3 was constructed using Cas9-triggered homologous recombination with drug selection, as previously described (9). For a complete list of strains and their genotypes, see Data S1.

Method details

Microfluidic device fabrication

The microfluidic device design used here was the same as in our previous work (3). Device molds were made using SU-8 photolithography, following standard procedures. A 10:1 ratio of polydimethylsiloxane (PDMS)/curing agent (Sylgard 184 silicone elastomer kit; Dow Corning, Midland, MI) was mixed, poured onto the molds, and degassed for 2 min. The molds were then spin coated with the PDMS at 300 rotations per minute for 30 s. The PDMS was cured at 85°C for 20 min before peeling off the molds. A 2 mm biopsy punch was used to create the inlet and outlet holes for each of the 12 channels per PDMS device.

24 × 60 mm glass coverslips were cleaned of visible dust using compressed nitrogen gas and placed in ultraviolet/ozone cleaner for 20 min. Meanwhile, PDMS devices were prepared for glass bonding by air plasma treatment for 30 s. Plasma-treated PDMS devices were placed onto cleaned glass coverslips to create a permanent bond. Devices were immediately passivated by placing 2 μL of poyethylene glycol (PEG) solution (monomethyl-PEG-silane with 2% HPLC water and 0.02% biotin-PEG-silane) into the inlets. Once the PEG solution flowed to the ends of the channels, 0.5 μL of PEG solution was placed into the outlets. After a 30–60 min incubation period at room temperature, the PEG solution was aspirated from the devices using a vacuum. The devices were rinsed twice by placing 2 μL of HPLC into both wells of each channel and vacuuming either the outlets or the inlets. The channels were dried thoroughly using a vacuum and placed into an airtight container containing desiccant. Devices were used within 1–2 months after PEG passivation.

Immediately before an experiment, devices were functionalized with anti-mNeonGreen (mNG) nanobodies. The channels of the devices were rehydrated by placing 1.5 μL of SiMPull buffer (10 mM Tris (pH 8.0), 50 mM NaCl, 0.1% Triton X-100, and 0.1 mg/mL bovine serum albumin) into each well and vacuuming the inlets to remove most of the liquid while leaving buffer in the channels. A solution of 0.2 mg/mL Neutravidin in SiMPull buffer was prepared, and 1.5 μL of the solution was placed into each outlet. The Neutravidin solution was allowed to flow through the channel for a 10 min incubation period at room temperature and washed with SiMPull buffer four times. A solution of 100 μM anti-mNG nanobody in SiMPull buffer was prepared, and 1.5 μL of the solution was placed into each outlet. The nanobody solution was allowed to flow through the channel for a 10 min incubation period at room temperature and washed with SiMPull buffer four times. Any lane that was not immediately used was hydrated with 0.5 μL SiMPull buffer in each well and sealed with clear tape. When an embryo was ready to be placed into a channel, the tape was cut off using a scalpel. Occasionally, devices were functionalized and stored at 4°C overnight before an experiment.

Monovalent nanobody preparation

Monovalent nanobodies recognizing mNG were biotinylated via incubation with 100-fold molar excess of EZ-Link N-hydroxysuccinimide-PEG4-biotin for 1 h at room temperature. The reactions were quenched with Tris base and dialyzed to remove excess biotin. To determine the concentration of final biotinylated mNG nanobody, ultraviolet absorbance at 280 nm was used.

HaloTag labeling

HaloTag ligands Janelia Fluor (JF)646, JFX646, and JFX650 yielded indistinguishable results and were used interchangeably in our experiments. Dyes were dissolved in acetonitrile and dispensed into 2 nmol aliquots. A speedvac was used to evaporate the solvent. The dried aliquots were stored at −20°C in dark, foil-wrapped containers. Immediately before labeling whole worms with HaloTag ligand, a dried aliquot was brought to a concentration of 1 mM with 2 μL dimethylsulfoxide (DMSO). An E. coli OP50 culture was spun down and resuspended in 0.2 volume of S medium (150 mM NaCl, 1 g/L K2HPO4, 6 g/L KH2PO4, 5 μg/L cholesterol, 10 mM potassium citrate (pH 6.0), 3 mM CaCl2, 3 mM MgCl2, 65 μM EDTA, 25 μM FeSO4, 10 μM MnCl2, 10 μM ZnSO4, 1 μM CuSO4). To obtain a final concentration of 10–15 μM HaloTag ligand, 1–1.5 μL of the DMSO aliquot was added to 100 μL of the bacterial suspension. 30 μL of the solution were placed into one well of a 96-well plate. About 30 worms at larval stage L4 were placed into the 30 μL of solution and incubated at 20°C overnight, shaking at 250 rotations per minute. The day after, gravid adults were picked to be dissected in egg buffer (5 mM HEPES (pH 7.4), 118 mM NaCl, 40 mM KCl, 3.4 mM MgCl2, 3.4 mM CaCl2).

sc-SiMPull from staged embryos

Gravid adults were dissected in egg buffer, and embryos were washed twice by sequentially transferring into two 40–100 μL drops of egg buffer using a mouth pipette. A zygote was then transferred to a 40–100 μL drop of SiMPull buffer. Next, 0.5–1 μL of SiMPull buffer was placed into the inlet well of a functionalized device. The zygote was transferred into the inlet well and either gently pushed into the channel using a clean 26G needle or gently pulled into the channel via vacuum. Channel flow was equilibrated to ∼0.5 μL of buffer in each inlet by placing or removing buffer from the wells using a mouth pipette. Once the zygote was immobile and secure in the channel, two small pieces of clear tape were placed over the outlet and inlet wells, in that order, to prevent buffer evaporation and flow in the channel. The device with the live zygote was transferred to the TIRF microscope for data collection. Importantly, the embryo was not suffocated and was able to continue developing up until the moment of laser lysis, as PDMS is oxygen permeable and the non-oxygen-permeable tape was confined to covering the wells.

TIRF microscope construction

The custom-built microscope used for our experiments was built around an RM21 Advanced microscope platform (MadCity Labs, Madison, WI). The instrument is equipped with a piezo-Z stage for focusing; a 60×, 1.49 NA Olympus APON TIRF objective lens (Olympus, Tokyo, Japan); and micromirrors positioned below the objective for dichroic-free, multiwavelength TIRF illumination (10,11). Illumination light was provided by 488 and 638 nm LaserBoxx diode lasers (Oxxius, Lannion, France) which were focused through a 25 μm precision pinhole (Edmund Optics, Barrington, NJ) as a spatial filter, collimated, and focused again at the back aperture of the objective lens. The fluorescence signal, collected by the objective lens, was focused using a tube lens with a focal length of 250 mm, resulting in an initial magnification of 83.33×. The image was split into green and far-red channels with a T565lpxr dichroic mirror (Chroma, Bellows Falls, VT), and the two images were collected side by side on the chip of a Prime95B camera (Teledyne Photometrics, Tucson, AZ). A set of relay lenses in the dual-view system introduced an additional 1.2× magnification, resulting in a total system magnification of 100×.

We made two modifications to the RM21 setup to enable dynamic sc-SiMPull experiments. First, we added a triggered 1064 nm pulsed laser (STP-40K; Teem photonics, Grenoble, France), which was installed on a separate optical path to focus at the sample plane rather than the back-focal plane. The triggering pulses were provided by an Arduino Uno (Arduino, Somerville, MA). The infrared laser was delivered to the objective via a short-pass dichroic mirror placed below the objective and the TIRF micromirrors (Fig. 1 B); this did not interfere with TIRF imaging and allowed us to perform laser lysis and TIRF in rapid succession without any moving parts in the optical path. Second, we modified the MadCity Labs TIRF-lock system to enable continuous focusing even when the TIRF lasers were off. We installed a low-power (4.5 mW), 850 nm diode laser whose output was made co-linear with the TIRF lasers. After the beam exited the objective, the 850 nm light was separated from the TIRF excitation light via a dichroic mirror and focused onto a quadrant photodiode detector (MadCity Labs). The detector was linked directly to the piezo-Z stage to maintain focus via software provided by MadCity Labs. The entire hardware setup was controlled by Micro-Manager 2.0-gamma (https://micro-manager.org/).

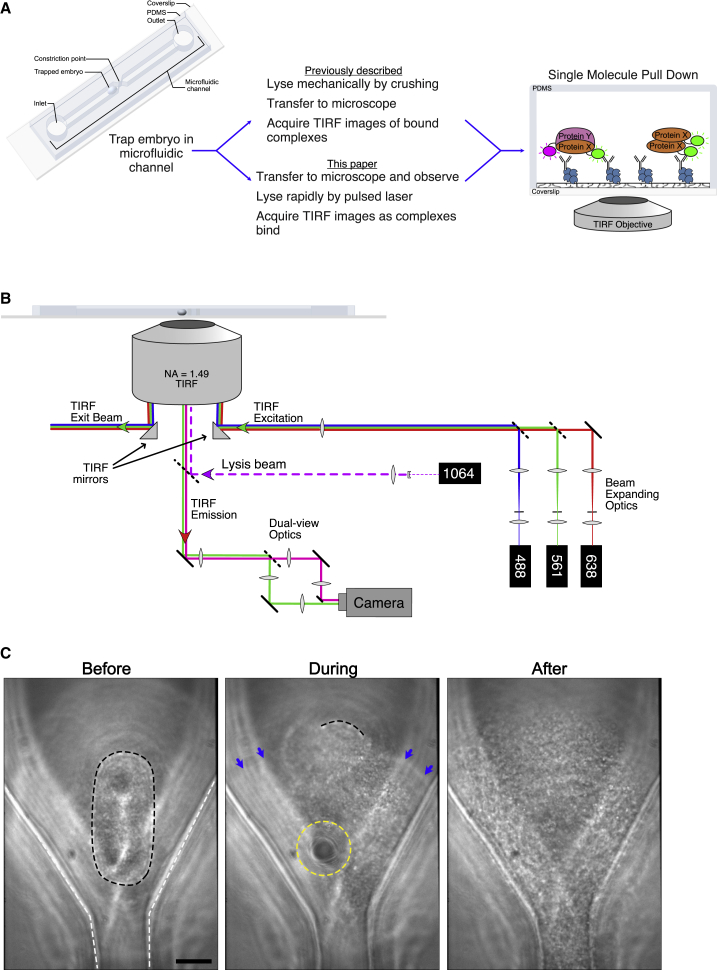

Figure 1.

Laser-induced lysis for single-cell, single-molecule pull down. (A) Overview of sc-SiMPull using mechanical versus laser-induced cell lysis. In both cases, the workflow begins by trapping an embryo in a PDMS microfluidic device with a volume of a few nanoliters (left). After cell lysis, proteins are captured by antibodies immobilized on the coverslip surface and are detected using single-molecule TIRF imaging (right). In the conventional workflow (center top), the cell is lysed before being transferred to the TIRF microscope (3); our new, to our knowledge, workflow (center bottom) uses a laser to perform lysis directly at the imaging microscope, allowing more rapid and reproducible data collection (see below). (B) Schematic of the microscope used to perform these experiments. TIRF illumination is performed using micromirrors located below the objective, allowing multiwavelength, dichroic-free single-molecule imaging (10,11). Fluorescence emission is detected with a dual-view emission path design for simultaneous multicolor imaging. We added a pulsed 1064 nm laser to this setup, focused at the sample plane, to induce cell lysis via formation of a localized plasma. (C) Brightfield images of a C. elegans zygote before, during, and after laser-induced lysis. The black dotted line outlines the cell membrane of the single-cell embryo. The white dotted line outlines the edges of the microfluidic channel. The yellow dotted line outlines the edges of the cavitation bubble. Blue arrows point to the edges of the shock wave as it moves through the channel. Scale bars, 10 μm. See also Video S1. To see this figure in color, go online.

Embryo lysis and TIRF microscopy

The channel in use was centered on the objective, and the embryo was located using transmitted light. Transmitted light was used to record a snapshot of the embryo for staging purposes. The stage was moved 120–200 μm away from the embryo to focus in TIRF. TIRF focus was determined using a 15 mW, 488 nm laser and a 50 mW, 638 nm laser, and TIRF lock was engaged. The TIRF lasers were turned off, and the stage was moved to center the embryo using transmitted light. The embryo was lysed using a 1064 nm Q-switched neodymium-doped yttrium aluminum garnet (Nd:YAG) pulsed laser. The stage was quickly moved 60–420 μm away from the point of lysis; the transmitted light was turned off, and continuous time-lapse acquisition using TIRF excitation was performed for 10–15 min. A stopwatch was used to record the elapsed time between laser lysis and the start of TIRF acquisition. mNG was excited using a 15 mW, 488 nm laser; HaloTag ligands JF646, JFX646, and JFX650 were excited using a 50 mW, 638 nm laser for all experiments except the lower laser power experiments, for which 5 mW were used.

Embryo lysis and confocal microscopy

Embryos were prepared as described in the sc-SiMPull from staged embryos subsection with the minor alterations of washing embryos with egg buffer once instead of twice before transferring to SiMPull buffer and mounting in the microfluidic chip. Samples were imaged using a Nikon Ti2 inverted microscope equipped with a 100×, 1.49 NA TIRF objective (Nikon Instruments, Melville, NY); an iSIM super-resolution confocal scan head (Visitech, Sunderland, UK); and a PrimeBSI scMOS camera (Teledyne Photometrics). We installed a lysis laser onto the back port of this instrument, as described in detail in the Supporting materials and methods. The channel in use was centered on the objective, and the embryo was located using transmitted light. Time-lapse imaging was preformed using a 488 nm laser to capture the fluorescent images, followed by using a brightfield view to capture optical cell lysis. Immediately after lysis, a new acquisition was initiated to capture simultaneous brightfield and fluorescent images after the cell lysis event. Images were acquired at a rate of one frame per second for up to 10 min or until the fluorescent signal dissipated.

Quantification and statistical analysis

Analysis of static SiMPull data

The analysis presented in Fig. 2 was done exactly as in our previous work (3) using our open-source SiMPull analysis software. Briefly, the first 50 frames of images from each stage position (along the length of the microfluidic channel) were averaged to produce high-contrast images for segmentation. Molecules in each frame were then detected using probabilistic segmentation (5) applied to both imaging channels. The left and right sides of the dual-view image were registered automatically using the built-in imregcorr function in MATLAB (The MathWorks, Natick, MA). The software then checks for colocalization; signals that were within one point-spread function of each other were considered colocalized. The software automatically ignores images that have a density of spots greater than 0.3 per μm2, which we previously found is the maximal density below which <5% of spots colocalize by chance (3). For the remaining images, colocalization was measured and summed across each sample by counting the number of colocalized molecules and dividing by the total number of molecules detected in each fluorescence channel. Data are presented as individual data points (one data point per embryo), with a weighted mean and 95% confidence interval calculated across the entire data set. 95% confidence intervals were calculated using the formula

where xi is the measured value from one single-embryo experiment, is the weighted mean, wi is the weight (defined as the number of molecules counted in experiment i divided by the total number of molecules counted in all experiments), n is the number of experiments performed, and the sums are over all experiments.

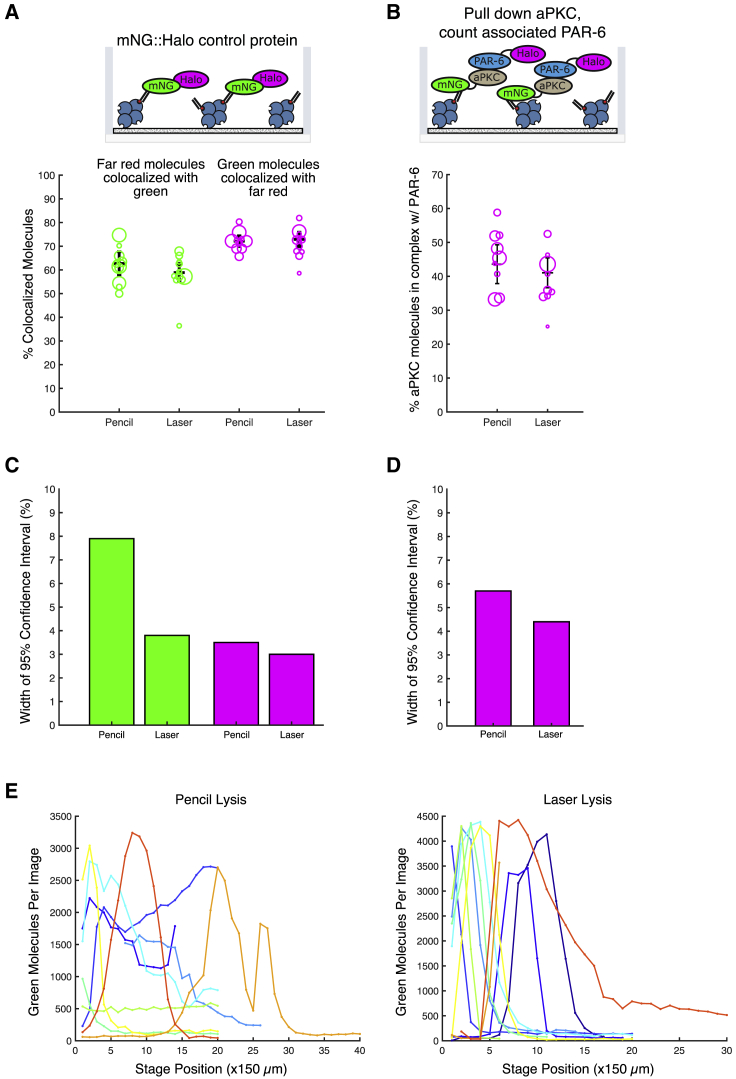

Figure 2.

Laser lysis is compatible with SiMPull and improves reproducibility. (A) Comparison of laser-induced and mechanical (“pencil”) lysis using an mNG::HaloTag control protein, in which the two tags are covalently fused as illustrated at the top. In the chart at the bottom, each circle represents a measurement from a single cell, and the size of each circle represents the number of molecules counted in that experiment. Regardless of the lysis method, we detect ∼60% of mNG molecules and ∼75% of HaloTag molecules in a typical positive control experiment. Npencil = 10; Nlaser = 11. (B) Comparison of laser-induced and mechanical lysis for analysis of the aPKC/PAR-6 interaction (top). Each circle represents a measurement from a single cell, and the size of each circle represents the number of molecules counted in that experiment (bottom). Npencil = 9; Nlaser = 9. (C and D) Widths of the 95% confidence intervals of the weighted means for each data set presented in (A) and (B). (E) Distribution of mNG::HaloTag molecules along the length of the microfluidic channel, measured by acquiring images at several stage positions. Each curve shows the results from a single experiment. Stage positions are 150 μm apart. To see this figure in color, go online.

Automated processing of dynamic SiMPull data

We added additional functionality for processing dynamic SiMPull data to our open-source SiMPull analysis software package and then used these new tools to extract the relevant information about each observed molecule in our dynamic experiments. The algorithm is illustrated in Fig. 3 B. The user chooses the bait channel, which is the fluorescent protein that has been pulled down in the experiment (in this work, this was always the green channel, as we exclusively used antibodies against mNG; however, this is flexible and other antibodies could be used if needed). The user also provides a reference image of either control proteins or beads, which is used to perform automated image registration of the left and right dual-view channels. Once registration is complete, the software bins each long TIRF video into “windows” (typically 50 frames in length) that are averaged to produce high-contrast images for segmentation. Consecutive windows are subtracted to generate difference images, which are then subjected to probabilistic segmentation (5) to identify the locations of newly appearing signals. Segmentation is only done on the bait protein channel, as our goal is to detect appearing bait proteins and ask whether they co-appear with prey proteins. Once the locations of appearing bait molecules are identified, the software returns to the raw (nonbinned) images and extracts the fluorescence intensity as a function of time, at each bait spot location, for both the bait and prey channels. Because our data sets can be as long at 16,000 image frames, analyzing the entire intensity trace for each molecule would be excessively costly (and is unnecessary). Instead, the software extracts and saves the 50 frames before a spot is expected to appear and the 450 frames afterwards (500 frames total). The intensity traces are analyzed using a Bayesian changepoint detection algorithm (12), with a log-odds ratio cutoff of 2 (corresponding to 99% confidence in each reported step) to find the time points when changes in intensity occur. The first increase in bait channel intensity is considered the time of spot appearance; traces in which no change in intensity occurs within the first 100 frames are not analyzed further. Once the time of bait protein appearance is found, the prey channel is checked for a corresponding intensity increase at the same time. Prey spots that appear at the same location and within four frames (200 ms) of the bait protein are considered co-appearing. The software saves a data file that contains the location, time of appearance, and intensity trace for every detected molecule, along with whether it was called as co-appearing. This data file can then be queried further to extract the key information from each experiment.

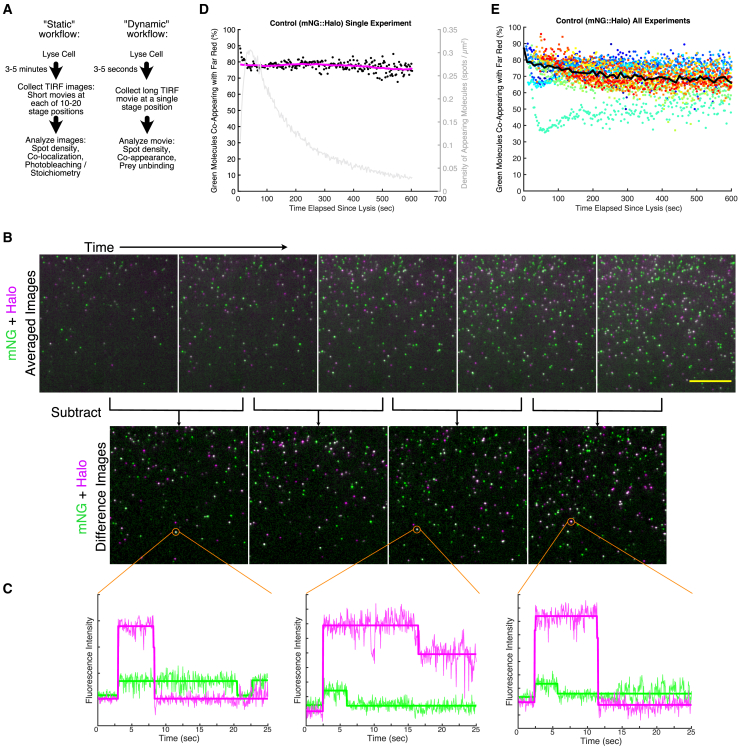

Figure 3.

A dynamic sc-SiMPull workflow. (A) Comparison of our previous “static” workflow (left) and the new “dynamic” workflow (right) enabled by laser lysis. (B) Illustration of a typical dynamic data set and our data processing approach. Top row: average intensity projections of consecutive 50-frame windows near the beginning of a dynamic data set. Molecules appear at the coverslip over time after cell lysis. Each image corresponds to 2.5 s worth of data. Scale bars, 10 μm. Second row: difference images obtained by subtracting each average intensity projection from the one that follows. Difference images are segmented to identify appearing molecules. (C) Example intensity versus time traces for co-appearing signals. The three indicated molecules were all classified as co-appearing based on the simultaneous increase in signal in both channels around 3 s after the start of the trace. (D) Results of one dynamic sc-SiMPull experiment with the mNG:HaloTag control protein. Black points show individual measurements of the fraction of molecules that co-appeared; each point corresponds to one 50-frame (2.5 s) window of the data. The magenta curve is a moving average of these data. The gray curve shows the density of appearing spots as a function of time, plotted on the right y axis. (E) Results of a complete set of experiments with the mNG::HaloTag control protein. Each color represents individual measurements for one sample, and the black curve is a moving average across all the data. Circles represent data that were acquired at 50 mW laser power, and squares represent data that were acquired at 5 mW laser power. The sea-green data set shows anomalously low co-appearance but was included here for completeness. N = 14. To see this figure in color, go online.

Postprocessing of dynamic SiMPull data

We created a set of tools within our software package to view the raw images, intensity versus time traces, co-appearance measurements, and kinetic properties of our data. These scripts allow the user to inspect and evaluate the data quality, retrieve co-appearance information from the data file, apply filters for molecular density and blinking, and generate plots. All plots shown in this work were generated using these open-source tools.

A typical workflow was to 1) inspect the images and ensure high-quality data; we excluded images with excessive background fluorescence (caused by poor coverslip cleaning) or for which no, or very few, fluorescent molecules appeared (this was sometimes caused by flow within the microfluidic channel because of poor sealing); 2) check images to ensure that the automated analysis delivered results that were reasonable; 3) correct image registration, if needed; and 4) perform downstream analyses of co-appearance versus time, dwell time distributions, and density, depending on the experiment. We intentionally automated as much of the analysis pipeline as possible, to reduce user interventions that might introduce bias.

Kinetic analysis: extracting koff from co-appearance versus time traces

To estimate protein complex dissociation kinetics from plots of co-appearance versus time, we fitted the raw data from each experiment to an exponential decay curve. We made two assumptions in our analysis. First, we assumed that PAR-6 and aPKC form a one-to-one heterodimer, which is supported by in vitro biochemical and crystallographic studies (13). Second, we assumed that the solution concentration of the bait protein (aPKC in our experiments) is small relative to the concentration of the prey protein. This assumption is common in receptor-ligand binding studies (14) and is justified in this particular case because the bait protein is rapidly depleted from solution by binding to immobilized antibodies within the microfluidic device (light gray curves in Figs. 3 D and 4 A), whereas the prey protein remains free to participate in biochemical reactions in solution. This second assumption allows an analytical solution of the rate equation and has, at most, a minor effect on our estimates of koff, as explained below. With these assumptions, the relaxation of this protein-protein binding reaction to equilibrium will be described by the equation

| (1) |

where aPKC•PAR6 denotes the aPKC/PAR-6 complex (we drop the hyphen from “PAR-6” for clarity), the “0” subscript denotes the initial concentration, the “eq” subscript denotes the concentration at equilibrium, and kdecay = koff + kon[PAR6] (14). If we do not assume that the concentration of the bait protein, aPKC, can be neglected (assumption 2 above), then kdecay = koff + kon[PAR6][aPKC]. We show below that the kon term makes only a small contribution to kdecay, so our estimates of koff would be only slightly affected if assumption 2 were invalid.

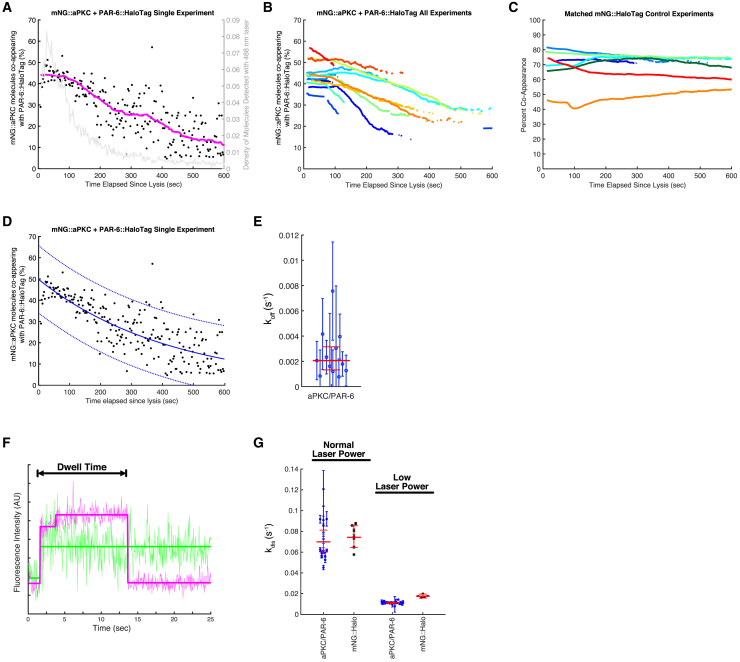

Figure 4.

Kinetic analysis of the aPKC/PAR-6 complex released from cells. (A) Results of one dynamic sc-SiMPull experiment with mNG::aPKC as the bait protein and PAR-6:HaloTag as the prey protein. Black points show individual measurements of the fraction of molecules that co-appeared; each point corresponds to one 50-frame (2.5 s) window of the data. The magenta curve is a moving average of these data. The gray curve shows the density of appearing spots as a function of time, plotted on the right y axis. (B) Co-appearance versus time for the full set of aPKC/PAR-6 experiments. For clarity, only the trendlines (equivalent to the magenta trace in A) are shown. N = 13. (C) Co-appearance versus time for a matched set of mNG::HaloTag control experiments. These samples were collected and imaged on the same days and with identical laser power to the aPKC/PAR-6 samples in (B). N = 7. (D) The same data as in (A) fitted to an exponential decay function (blue solid curve). Blue dashed curves show the 95% confidence intervals of the fit. (E) Estimates of the dissociation rate constant koff from exponential fits to each individual data sets (as in D). Each point shows the result of one experiment with its 95% confidence interval. The horizontal red line and error bars represent the geometric mean across all samples, with its 95% confidence interval. N = 12. (F) Intensity versus time trace for a representative mNG::aPKC molecule that co-appeared with PAR-6:HaloTag, illustrating the dwell time that was measured to determine the disappearance rate constant kdisappear from dwell time distribution analysis. (G) Measurements of kdisappear for aPKC/PAR-6 samples and control mNG:HaloTag samples at two different laser powers. Each point shows the results of one experiment, with the error bars indicating the 95% credible interval from the Bayesian dwell time distribution analysis (15). The horizontal red line and error bars represent the geometric mean across all samples, with its 95% confidence interval. NaPKC/PAR-6 = 15; NmNG::Halo = 7; NaPKC/PAR-6 Low Laser = 19; NmNG::Halo Low Laser = 5. To see this figure in color, go online.

Because aPKC was the bait protein in our experiments, what we measured was the fraction of aPKC molecules bound to PAR-6—that is, the ratio of [aPKC•PAR6] to the total (bound + unbound) aPKC concentration [aPKC]tot. We denote the fraction bound as F. Dividing through by [aPKC]tot, Eq. 1 becomes

| (2) |

We fitted each data set to the equation y = Ae−Bt + C to extract the parameters A = (F0 − Feq), B = kdecay, and C = Feq using the built-in fit function in MATLAB to perform a nonlinear least-squares fit. Fits with R2 < 0.2 were excluded from our analysis.

To estimate koff for the complex, we derived an expression for koff in terms of kdecay and Feq, which we obtained from our curve fits as follows. Beginning with the expression for the equilibrium dissociation constant KD,

we rearrange to obtain

| (3) |

From the expression for kdecay, we also have

| (4) |

Substituting Eq. 4 into Eq. 3 and rearranging, we obtain our final expression for koff:

| (5) |

Equation 5 allows us to calculate koff from our experimental co-appearance versus time data. Note that under conditions in which protein complexes that dissociate do not rebind (for example, because of dilution), Feq = 0 and Eq. 5 reduces to koff = kdecay, as expected. Our experimental fits yielded Feq < 20% for all samples and Feq < 5% for 10 out of 12 samples, indicating that under our conditions, the contribution of rebinding to equilibration is minor, and thus, koff will always be close to kdecay.

One final complication is that our experimental estimates of Feq, and thus koff, will be affected by incomplete labeling of HaloTag with fluorescent dyes. Because Feq was small in our experiments, the magnitude of the resulting error will also be small, but we corrected for it nonetheless. Based on an estimated labeling efficiency of ∼75% (Fig. 3 E), we divided Feq by 0.75 before calculating koff.

Kinetic analysis: extracting kdisappear from dwell time distribution analysis

To measure the dwell times of individual prey proteins, we wrote a simple postprocessing script that calculates the interval between co-appearance of a complex and the time when the prey intensity returns to its initial (background) value. We deliberately neglected fluctuations in the prey protein intensity (as long as intensity remained above background) because we have observed that single HaloTag molecules labeled with Janelia Fluor dyes can fluctuate in intensity over time (D.J.D., unpublished data). Our dwell time distribution analysis followed the template given in (15). We calculated a prey disappearance probability (per image frame) using the equation

where Pdisappear is the probability that the prey protein disappears (angular brackets denote the mean), ndisappear is the number of disappearance events observed, and nnondisappear is the number of frames a prey molecule was observed to remain bound and not disappear. The disappearance probability is related to the disappearance rate constant by

where τ is the measurement interval (15), typically 50 ms in our experiments. 95% confidence intervals around kdisappear were calculated from the β distribution using the MATLAB function betaincinv. We report the confidence interval calculated in this way for each experiment, and a geometric mean and 95% confidence interval for kdisappear across each data set. The geometric mean was chosen because normality tests indicated that our estimates of kdisappear were most likely to be log-normally distributed; normality testing and calculation of confidence intervals were done using GraphPad Prism software.

Results

Incorporating laser-induced cell lysis into an sc-SiMPull assay

We use C. elegans zygotes as model cells throughout this work because they are easy to isolate and image, develop via a stereotyped series of morphologically distinct stages (16), and can be easily manipulated via CRISPR/Cas9-mediated genome editing to carry fluorescent tags on endogenous proteins (9,17,18). In the standard sc-SiMPull assays we previously described (3), an individual zygote is first selected and trapped in a funnel-shaped microfluidic device made of PDMS (Fig. 1 A, left). The cell is staged via manual observation on a stereomicroscope and then lysed mechanically, by pushing down on the PDMS surface (Fig. 1 A, top). Upon lysis, cellular proteins diffuse within the microfluidic channel and bind to antibodies, which are immobilized on a coverslip that forms the floor of the device (Fig. 1 A, right center). After cell lysis, the device is transferred to a TIRF microscope, and single-molecule images are acquired. Transferring the device to the TIRF microscope is the rate-limiting step in this assay; moving the device, focusing, configuring, and starting data acquisition take a minimum of 2–3 min. During this time, protein complexes can rearrange, so the results represent the pre-lysis state only in the case of stable protein complexes. Moreover, the manual nature of the staging and mechanical lysis introduces unwanted variability between experiments and experimenters.

To overcome these limitations, we turned to cell lysis induced by a passively Q-switched Nd:YAG pulsed laser. These lasers are compact, relatively inexpensive, and produce pulses of laser light lasting several hundred picoseconds. When focused to a diffraction-limited spot by a high numerical aperture objective lens, these lasers produce a localized plasma, which in turn generates a shock wave and a cavitation bubble in aqueous medium (19, 20, 21). Lysis occurs within a few microseconds after irradiation and is thought to occur as a result of mechanical disruption of the cell membrane by the shock wave and cavitation bubble and not by the laser light per se (19, 20, 21). Because formation of a shock wave and cavitation bubble is relatively independent of laser wavelength (22), we chose to use an infrared 1064 nm laser for cell lysis to avoid interference with subsequent fluorescence-based assays.

We installed and configured the lysis laser on a multiwavelength TIRF microscope based on a micromirror geometry (10,11). In a micromirror TIRF instrument, a small mirror (“micromirror”) is positioned directly below the back aperture of the objective lens to deliver TIRF excitation light to the sample, and a second micromirror collects the reflected TIRF beam and delivers it to a beam dump (Fig. 1 B). The fluorescence emission passes between the two micromirrors to a multiwavelength imaging system (dual-view optics in Fig. 1 B). Micromirror TIRF enables straightforward single-molecule imaging using multiple wavelengths simultaneously, which in turn enables kinetic measurements of protein complex formation and dissociation (10,11). We added a short-pass dichroic mirror below the micromirrors to reflect the infrared lysis beam toward the sample without interfering with fluorescence detection in visible wavelengths (Fig. 1 B). The lysis beam was expanded and collimated to fill the back aperture of the objective, thereby focusing to a diffraction-limited spot in the sample plane. A single shot from the laser produced a shock wave and cavitation bubble, which was sufficient to lyse a C. elegans zygote (Fig. 1 C and Video S1).

. The movie plays at actual speed.

To investigate the efficiency and completeness of laser lysis, we built a second laser lysis system on a commercial microscope equipped for confocal imaging (see Supporting materials and methods for details of this instrument construction), allowing us to perform high-resolution time-lapse imaging of embryos carrying various organelle markers (23, 24, 25, 26) before, during, and after lysis. We found that the cytoplasm, nuclear envelope, endoplasmic reticulum, and plasma membrane were rapidly solubilized with our optical lysis approach (Fig. S1, A–D; Video S2. Optical lysis of a C. elegans zygote expressing a cytoplasmic protein, Video S3. Optical lysis of a C. elegans zygote expressing a nuclear pore protein, Video S4. Optical lysis of a two-cell C. elegans embryo expressing an endoplasmic reticulum marker, Video S5. Optical lysis of a four-cell C. elegans embryo expressing a transmembrane protein). We also observed that when the laser was aimed at a single cell in a multicelled embryo, the target cell was rapidly solubilized, whereas the nontarget cells underwent delayed solubilization (Fig. S1 E; Video S6). Interestingly, mitochondria remained largely intact for at least 8 min after optical lysis, the longest time interval we observed (Fig. S1 F; Video S7). We concluded that our optical lysis approach is effective at solubilizing most cellular organelles, although different buffer conditions may be needed to solubilize mitochondria.

Fluorescent images of a C. elegans zygote cytosolically expressing mNG::Halo followed by a brightfield view of the zygote being lysed with a single shot from the pulsed infrared laser. Fluorescent signal is monitored as the cytoplasm solubilizes and diffuses in the SiMPull buffer. Brightfield at the end of the movie demonstrates the cell lysate that remains in the field of view. The movie plays at 7 frames per second. Scale bar represents 10 μm.

Fluorescent images of a C. elegans zygote during pronuclear meeting expressing mNG::NPP-10 in the nuclear envelope followed by a brightfield view of the zygote being lysed with a single shot from the pulsed infrared laser. Fluorescent signal is monitored as the nuclear envelope solubilizes and diffuses in the SiMPull buffer. Brightfield at the end of the movie demonstrates the cell lysate that remains in the field of view. The movie plays at 7 frames per second. Scale bar represents 10 μm.

Fluorescent images of a C. elegans embryo expressing GFP::C34B2.10 in the endoplasmic reticulum (ER) by a brightfield view of the embryo being lysed with a single shot from the pulsed infrared laser. Fluorescent signal is monitored as the ER solubilizes and diffuses in the SiMPull buffer. Brightfield at the end of the movie demonstrates the cell lysate that remains in the field of view. The movie plays at 7 frames per second. Scale bar represents 10 μm.

Fluorescent images of a C. elegans embryo expressing transmembrane protein MOM-5::mNG in the plasma membrane followed by a brightfield view of the embryo being lysed with a single shot from the pulsed infrared laser. Fluorescent signal is monitored as the plasma membrane solubilizes and diffuses in the SiMPull buffer. Brightfield at the end of the movie demonstrates the cell lysate that remains in the field of view. The movie plays at 7 frames per second. Scale bar represents 10 μm.

Fluorescent images of a C. elegans embryo expressing transmembrane protein MOM-5::mNG in the plasma membrane followed by a brightfield view as the middle-top cell of the embryo is lysed with a single shot from the pulsed infrared laser. Fluorescent signal is monitored as the plasma membrane solubilizes and diffuses in the SiMPull buffer. Brightfield at the end of the movie demonstrates the cell lysate that remains in the field of view. The movie plays at 7 frames per second. Scale bar represents 10 μm.

Fluorescent images of a C. elegans embryo expressing outer mitochondrial membrane marker tomm- 20::GFP followed by a brightfield view of the embryo being lysed with a single shot from the pulsed infrared laser. Fluorescent signal is monitored as the mitochondria somewhat solubilizes and diffuses in the SiMPull buffer. Brightfield at the end of the movie demonstrates the cell lysate that remains in the field of view. The movie plays at 7 frames per second. Scale bar represents 10 μm.

Laser lysis is compatible with SiMPull and improves reproducibility

We performed control experiments to determine whether laser lysis was compatible with single-molecule fluorescence assays such as sc-SiMPull. First, we checked whether the lysis laser induced photobleaching of mNG or JF646, which are the two fluorophores we use most commonly in sc-SiMPull assays. To check for photobleaching, we lysed zygotes expressing an mNG::HaloTag fusion protein that was labeled with Halo-JF646, captured the fusion protein with anti-mNG nanobodies, and analyzed the colocalization between green (mNG) and far-red (JF646) signals (Fig. 2 A, top). Because mNG and HaloTag are covalently attached to one another in this experiment, 100% of the green and far-red signals should colocalize in principle. In practice, as we demonstrated in our previous experiments, less than 100% colocalization is observed because of incomplete maturation of mNG fluorescent protein and incomplete labeling of the HaloTag with its ligand dye (3). The actual extent of colocalization is a measurement of the efficiency with which each fluorescent tag is detected. Photobleaching would appear as a reduced detection efficiency for the bleached dye. Using our previous method of lysing zyogtes mechanically by pressing on the microfluidic device with the tip of a pencil, we detected 63 ± 8% (mean ± 95% confidence interval) of mNG molecules and 72 ± 4% of JF646 molecules (Fig. 2 A, bottom), consistent with our previous results (3). We detected 59 ± 4% of mNG molecules and 73 ± 3% of JF646 molecules when we lysed cells with the laser, which is indistinguishable from the results of mechanical lysis (Fig. 2 A). We conclude that laser lysis does not detectably photobleach mNG or JF646 fluorescent labels (3).

We next asked whether protein-protein interactions are preserved after laser lysis. Laser lysis has been proposed to be nondamaging to cellular proteins (27,28). Indeed, protein damage is not expected in our setup because the laser focus (where plasma formation occurs) is located at the glass-water interface, which is outside the cell, and lysis occurs because of the mechanical effects of cavitation bubble formation. Nevertheless, we wanted to directly test whether a known protein complex was stable through the laser lysis process. We therefore examined the interaction between aPKC and PAR-6, two proteins that are known to form a complex in C. elegans zygotes (3,29,30). We lysed zygotes from a strain carrying mNG::aPKC and PAR-6::Halo tagged at their endogenous genomic loci (3), captured mNG::aPKC with an anti-mNG nanobody, and measured the fraction of mNG::aPKC molecules associated with PAR-6::Halo (Fig. 2 B, top). We observed an equivalent fraction of molecules in complex regardless of the lysis method (Fig. 2 B, bottom), and the results again agree with our previous report (3). We conclude that laser lysis does not disrupt the aPKC/PAR-6 interaction. Although these data do not rule out that some protein complexes might be affected by laser lysis, they argue against a large-scale disruption of protein-protein interactions by our laser setup (19,20).

Interestingly, when analyzing these control experiments, we observed a small but consistent trend toward lower cell-to-cell variability in our SiMPull data when cells were lysed by the pulsed laser (Fig. 2, C and D). We also found that when we analyzed the distribution of captured molecules along the length of the microfluidic channel, cells lysed by the laser produced a narrower and more consistent peak of signal near the site of lysis than cells lysed manually (Fig. 2 E). Together, these observations suggest that laser lysis improves the reproducibility of sc-SiMPull experiments. We also note that when performing laser lysis experiments, we routinely acquire an image of the cell immediately before lysis, which will lend additional confidence to experiments that require precise staging (e.g., (3)). We conclude that laser lysis improves the speed, precision, and reproducibility of sc-SiMPull experiments without otherwise affecting the results.

Dynamic analysis of cellular protein complexes after single-cell lysis

We next considered whether rapid lysis might enable us to gain kinetic information that would not be available using other methods. In the typical workflow that we have used up to this point, we lyse a cell, incubate the lysate for several minutes, and then analyze molecules that are bound to the coverslip surface. We refer to this approach as a “static” workflow (Fig. 3 A, left). Static sc-SiMPull experiments can provide information about the abundance and stoichiometry of protein complexes that are stable enough to survive several minutes of incubation after cell lysis, but static experiments do not provide any kinetic information and are not applicable to transient complexes. We envisioned an alternative “dynamic” workflow in which we would begin acquiring data immediately (within seconds) after lysis and observe the progression of the binding reaction between immobilized antibodies and a protein complex of interest (Fig. 3 A, right). We show below how dynamic experiments provide kinetic information about the stability and dynamics of protein complexes retrieved directly from cells.

To realize this approach, we first studied the control mNG::HaloTag fusion protein. We lysed embryos carrying this protein, immediately moved to an adjacent stage position, and observed the coverslip surface over time using TIRF. Acquisition typically started 5–10 s after cell lysis. In the resulting videos, fluorescent molecules began to appear over time in a region of the device that initially had been empty (Fig. 3 B, top row, and Video S8). As expected, many of these molecules were fluorescent in both the green (mNG) and far-red (HaloTag) channels. We refer to the simultaneous appearance of a fluorescent signal in both channels as “co-appearance.” Co-appearance is the dynamic analog of the colocalization between labels that we measure in a static experiment. When two fluorescently tagged molecules co-appear, we infer that they are in a complex. Co-appearance is a more stringent metric for protein-protein interaction than colocalization because it requires that signals occur together not only in the two-dimensional space of the image but also in time.

Time-lapse of mNG::HaloTag molecules appearing at the coverslip. Magenta is Halo ligand JFX646; Green is mNeonGreen. TIRF acquisition begins 11 seconds after cell lysis. The movie plays at 10 frames per second, and each frame is an average of 50 frames (1s) of actual data. Thus, each 1s of the movie represent 10s of actual data acquisition. Scale bar represents 10 μm.

We developed an open-source MATLAB package to extract, quantify, and visualize co-appearance data from time-lapse TIRF videos of single-molecule appearances (see Materials and methods for details). In brief, our analysis pipeline consists of two steps: molecule detection and co-appearance analysis. First, for molecule detection, each video is divided into windows of 20–50 frames, and images in each window are averaged to increase signal/noise (Fig. 3 B, top row). To identify newly appearing spots, pairs of adjacent averaged images are subtracted, producing difference images such that visible signals are spots that appeared in that window (Fig. 3 B, bottom row). The difference images are segmented to identify the locations of newly appearing spots. Second, for co-appearance analysis, an intensity versus time trace is extracted for each spot (from the raw, not averaged, data) (Fig. 3 C). The software processes each trace using a Bayesian framework to detect changes in signal intensity (12) and calculates a mean intensity for each segment of each trace (Fig. 3 C, bold lines). Traces in which both channels show a simultaneous increase in intensity (as in Fig. 3 C) are considered co-appearing. A gallery of traces, showing examples of different behaviors, is presented in Fig. S2. While developing this analysis platform, we identified missed or erroneous co-appearance events caused by photoblinking (Fig. S3 A) and by molecule densities that were too low (Fig. S3 B) or too high (Fig. S3 C), and our software incorporates optional settings to filter out these artifacts automatically.

Because co-appearance is a new, to our knowledge, metric for protein-protein interactions, we benchmarked our analysis pipeline using the control mNG::HaloTag protein. We observed that 70–80% of mNG molecules co-appeared with HaloTag (Fig. 3, D and E), in agreement with our static data using the same construct and fluorophores (Fig. 2 B), confirming that our co-appearance analysis successfully detected proteins that are associated with one another. We also found two other notable features of the co-appearance metric. First, co-appearance was less sensitive to molecular density than static colocalization: We could accurately measure co-appearance at densities up to at least 0.8 molecules present per μm2 (Fig. S3, C and D), whereas colocalization measurements are reliable only up to densities of ∼0.3 molecules per μm2 (3). Our ability to detect co-appearance did suffer at extremely high densities (>0.8 molecules per μm2), likely because of the difficulty of extracting accurate intensity versus time traces from crowded images (Fig. S3, C and D). Second, co-appearance measurements had lower background; a pair of proteins that were not expected to interact co-appeared less than 2% of the time (Fig. S3 E), whereas static data sets can exhibit nonspecific colocalization of 5–10% of spots depending on the density of molecules on the coverslip (3). We conclude that co-appearance of molecules in a single-molecule pull-down assay is a robust, accurate, and specific metric of protein-protein interactions.

Dynamic analysis provides information about protein-protein interaction kinetics

We predicted that dynamic, time-resolved measurements of protein-protein interactions in fresh cell lysates could provide a wealth of information about the kinetics and strength of these interactions. To explore this idea, we studied the aPKC/PAR-6 complex. When we lysed a zygote and captured mNG::aPKC molecules with an anti-mNG nanobody, we observed co-appearing PAR-6::HaloTag molecules, indicating that aPKC and PAR-6 are in complex, as expected (Video S9). The initial fraction of co-appearing signals was 40–50%, consistent with our results from static data (compare Fig. 4 B to Fig. 2 B). Interestingly, however, we found that the fraction of co-appearing spots declined over time (Fig. 4, A and B). This decline was not due to photobleaching because control mNG::HaloTag samples imaged on the same days and under identical conditions did not show a similar decline in co-appearance over time (compare Fig. 4 B to C). We therefore deduce that the decline in co-appearance is due to dissociation of the aPKC/PAR-6 complex in solution over time after cell lysis. This interpretation is consistent with the prediction that cellular protein complexes should dissociate in solution after cell lysis because dilution of the cell contents into a larger volume will shift the system toward a new equilibrium.

Time-lapse of mNG::aPKC molecules binding to the coverslip and forming complexes with PAR- 6::HaloTag molecules. Magenta is endogenous PAR-6::HaloTag bound to Halo ligand JFX650; Green is endogenous mNeonGreen::aPKC. TIRF acquisition begins 5 seconds after cell lysis. The movie plays at 10 frames per second, and each frame is an average of 50 frames (1s) of actual data. Thus, each 1s of the movie represent 10s of actual data acquisition. Scale bar represents 10 μm.

To quantify the stability of the aPKC/PAR-6 complex, we fitted the co-appearance data from each sample to an exponential decay (Fig. 4 D shows an example fit) to extract the apparent decay rate constant kdecay. We derived a relationship between kdecay and the dissociation rate constant koff (see Materials and methods) and used this relationship to estimate koff for each sample. We obtained an estimated koff = 2.0 × 10−3 s−1 (geometric mean; 95% confidence interval from 1.3 × 10−3 s−1 to 3.2 × 10−3 s−1) from these measurements (Fig. 4 E). The equilibrium dissociation constant KD is related to koff by the equation . Because kon-values for protein-protein association reactions are typically 106–107 M−1 s−1 (1), our results imply that the aPKC/PAR-6 interaction most likely has a KD in the range of 0.2–2 nM. This affinity indicates very tight binding, comparable to typical high-affinity antibody-antigen interactions. This result is consistent with the known robust association between aPKC and PAR-6 demonstrated by previous studies (3,13,29, 30, 31, 32, 33).

An alternative way to estimate koff for a protein complex is to measure the lifetime of the bound state, taking advantage of the ability to directly observe binding and unbinding events in single-molecule TIRF experiments (10,11,15). Our automated analysis allowed us to readily measure dwell times—defined as the time from complex co-appearance to prey protein disappearance (Fig. 4 F)—from thousands of aPKC/PAR-6 complexes. From the distribution of dwell time measurements, it is straightforward to calculate a disappearance rate constant kdisappear and its confidence interval (15). This observed rate constant will be faster than the true koff because prey molecules can disappear because of photobleaching in addition to dissociation of the complex. The disappearance rate constant is the sum of the rate constants for complex dissociation and photobleaching: kdisappear = koff + kbleach. Fortunately, we can measure kbleach from parallel experiments with the covalent mNG::HaloTag fusion protein, for which koff = 0. We performed this analysis and found kdisappear = 7.0 × 10−2 s−1 (95% confidence interval from 6.0 × 10−2 s−1 to 8.1 × 10−2 s−1) for the aPKC/PAR-6 complex and kbleach = 7.4 × 10−2 s−1 (95% confidence interval from 6.5 × 10−2 s−1 to 8.5 × 10−2 s−1) for mNG::HaloTag samples imaged in parallel (Fig. 4 G). kbleach and kdisappear are equal within experimental error, indicating that the dwell times of aPKC/PAR-6 complexes are dominated by photobleaching rather than complex dissociation. This finding is consistent with the fact that kbleach is more than 30-fold faster than the koff measured from exponential curve fitting above; under such conditions, a large majority of prey molecules will photobleach before they dissociate. Next, we attempted to reduce kbleach by lowering the laser power used to image the PAR-6::HaloTag prey protein. Reducing the laser power strongly reduced the rate of molecule disappearance (Fig. 4 G), confirming that the disappearance of PAR-6::HaloTag in these experiments is dominated by photobleaching. Under lower laser power conditions, we found kdisappear = 1.11 × 10−2 s−1 (95% confidence interval from 1.05 × 10−2 s−1 to 1.18 × 10−2 s−1), which is reduced compared to our normal imaging conditions but still an order of magnitude greater than our estimate of koff from curve fitting above (Fig. 4, D and E). Even under low laser power conditions, kdisappear and kbleach were similar; we could not detect a faster kdisappear (which would indicate unbinding) for the aPKC/PAR-6 complex compared to the control protein (Fig. 4 G). This result validates our conclusion that the aPKC/PAR-6 complex dissociates very slowly because of high-affinity binding. Although the aPKC/PAR-6 complex has a koff that is too slow to be estimated from our dwell time measurements, the results still show that kdisappear can be readily measured from our data. We anticipate that dwell time distribution analysis will be useful for more transient complexes, which will undergo measurable dissociation on a timescale comparable to (or faster than) photobleaching. Conversely, we expect that it will be more difficult to measure koff from curve fitting for transient interactions because such interactions might not generate long enough co-appearance versus time traces to enable robust fitting. Therefore, the curve fitting and dwell time approaches to measure koff are complementary: the curve fitting approach is best suited to stable interactions such as aPKC/PAR-6, whereas the dwell time approach will be best for more transient interactions.

Discussion

Regulated assembly of protein complexes is a major mechanism by which cells process information for signal transduction and control of cell behavior. To study the regulation of protein-protein interactions, there is a need for new tools that can measure these interactions rapidly, quantitatively, and in vivo. Here, we have addressed this need by developing instrumentation and software for rapid single-cell, single-molecule pull-down assays. Our dynamic sc-SiMPull approach allows us to measure the strength of an interaction (in the form of a koff) using native protein complexes isolated directly from living cells. By using CRISPR to label endogenous proteins, we work exclusively with proteins at their native expression levels. Although our assays do not yet reach the degree of precision and control that is possible in vitro with purified proteins, our approach has the strength that it is applicable to proteins and protein complexes that are post-translationally modified, difficult to purify, or both.

We used dynamic sc-SiMPull to study the dynamics of the aPKC/PAR-6 complex from C. elegans zygotes and measured a koff in the range of 10−3 s−1, suggesting low-nanomolar binding affinity. The tight binding affinity we have estimated is consistent with the propensity of PAR-6 to aggregate when not bound to aPKC (34) and with the observation that in vivo, PAR-6 is degraded when aPKC is depleted by RNA interference (29). To our knowledge, this is the first direct estimate of the affinity of this interaction, likely because PAR-6 is challenging to purify as a full-length protein (it can be efficiently purified only as a complex with aPKC) (34). Many important cellular proteins are similarly challenging to purify because of obligate binding partners, unstructured regions, or a propensity to aggregate. Our success in quantitively studying the PAR-6/aPKC complex suggests that our approach will be applicable to a wide range of protein complexes that have been refractory to purification.

The dynamic sc-SiMPull approach poses a significant advantage in studying in vivo protein interactions, especially those involving proteins that are difficult to purify. However, this method still has some limitations that are important to acknowledge. First, the approach requires fluorescent tagging, which can perturb the functions of some proteins by sterically blocking important interactions. Working in C. elegans has allowed us to rapidly test different combinations of tag locations to identify those that do not cause deleterious phenotypes, but this will be more difficult in less genetically tractable systems. It is also possible that some proteins will remain difficult to study because of the conformational constraint that is created by antibody binding and immobilization on the coverslip. Second, there may be a need to optimize buffer conditions for specific proteins or cellular compartments, as illustrated by our inability to lyse mitochondria in our standard buffer (Fig. S1 F). Finally, we note that no protein-protein interaction assay is immune to false-negative results, and it remains possible that dynamic sc-SiMPull might fail to detect some interactions for unknown reasons.

Our focus here has been to establish and validate the dynamic sc-SiMPull approach through studying control samples and the well-characterized aPKC/PAR-6 interaction. There are several features of this assay that we have not explored here but that will be valuable when working with complexes that are less stable and well-characterized. First, because it is now possible to begin counting protein complexes within seconds after lysis, this assay should be applicable to weak or transient protein-protein interactions that might be difficult to detect with other cell-based approaches. Second, by imaging and then immediately lysing cells or embryos, it will be possible to precisely (and rigorously) stage samples before lysis. This will allow investigators to measure how protein complexes are regulated across development or changes in cell state, revealing features of signal transduction that in vitro assays cannot capture. Finally, our framework should be readily generalizable to more than two fluorescent colors, allowing multiprotein assemblies to be studied with this approach. These ideas will be explored in future work.

Author contributions

D.J.D. conceived of the project and built the laser lysis setup. S.S. and D.J.D. together designed the experiments, performed the experiments, developed the analysis software, and analyzed the data. D.J.D. wrote the first draft of the manuscript; both authors discussed and contributed to the final version.

Acknowledgments

We thank Luke Lavis for sharing Janelia Fluor dyes, Eric Drier and members of the Dickinson laboratory for helpful discussions and comments on the manuscript, and Robert J. Dickinson for assistance testing laser lysis equipment.

This work was supported by a research grant from the Mallinckrodt Foundation and by National Institutes of Health R00 GM115964 and R01 GM138443 (D.J.D.). D.J.D. is a CPRIT Scholar supported by the Cancer Prevention and Research Institute of Texas (RR170054). Some strains were provided by the Caenorhabditis Genetics Center, which is funded by the National Institutes of Health Office of Research Infrastructure Programs (P40 OD010440).

Editor: Amy Palmer.

Footnotes

Supporting material can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bpj.2021.10.011.

Supporting material

References

- 1.Pollard T.D. A guide to simple and informative binding assays. Mol. Biol. Cell. 2010;21:4061–4067. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E10-08-0683. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Jarmoskaite I., AlSadhan I., et al. Herschlag D. How to measure and evaluate binding affinities. eLife. 2020;9:e57264. doi: 10.7554/eLife.57264. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Dickinson D.J., Schwager F., et al. Goldstein B. A single-cell biochemistry approach reveals PAR complex dynamics during cell polarization. Dev. Cell. 2017;42:416–434.e11. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2017.07.024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Jain A., Liu R., et al. Ha T. Probing cellular protein complexes using single-molecule pull-down. Nature. 2011;473:484–488. doi: 10.1038/nature10016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Padeganeh A., Ryan J., et al. Maddox P.S. Octameric CENP-A nucleosomes are present at human centromeres throughout the cell cycle. Curr. Biol. 2013;23:764–769. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2013.03.037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lee H.-W., Kyung T., et al. Yoon T.-Y. Real-time single-molecule co-immunoprecipitation analyses reveal cancer-specific Ras signalling dynamics. Nat. Commun. 2013;4:1505. doi: 10.1038/ncomms2507. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Choi B., Cha M., et al. Yoon T.-Y. Single-molecule functional anatomy of endogenous HER2-HER3 heterodimers. eLife. 2020;9:e53934. doi: 10.7554/eLife.53934. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Dickinson D.J., Ward J.D., et al. Goldstein B. Engineering the Caenorhabditis elegans genome using Cas9-triggered homologous recombination. Nat. Methods. 2013;10:1028–1034. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.2641. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Dickinson D.J., Pani A.M., et al. Goldstein B. Streamlined genome engineering with a self-excising drug selection cassette. Genetics. 2015;200:1035–1049. doi: 10.1534/genetics.115.178335. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Friedman L.J., Chung J., Gelles J. Viewing dynamic assembly of molecular complexes by multi-wavelength single-molecule fluorescence. Biophys. J. 2006;91:1023–1031. doi: 10.1529/biophysj.106.084004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Friedman L.J., Gelles J. Multi-wavelength single-molecule fluorescence analysis of transcription mechanisms. Methods. 2015;86:27–36. doi: 10.1016/j.ymeth.2015.05.026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ensign D.L., Pande V.S. Bayesian detection of intensity changes in single molecule and molecular dynamics trajectories. J. Phys. Chem. B. 2010;114:280–292. doi: 10.1021/jp906786b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hirano Y., Yoshinaga S., et al. Inagaki F. Structure of a cell polarity regulator, a complex between atypical PKC and Par6 PB1 domains. J. Biol. Chem. 2005;280:9653–9661. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M409823200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hulme E.C., Trevethick M.A. Ligand binding assays at equilibrium: validation and interpretation. Br. J. Pharmacol. 2010;161:1219–1237. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.2009.00604.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kinz-Thompson C.D., Bailey N.A., Gonzalez R.L., Jr. Precisely and accurately inferring single-molecule rate constants. Methods Enzymol. 2016;581:187–225. doi: 10.1016/bs.mie.2016.08.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Cuenca A.A., Schetter A., et al. Seydoux G. Polarization of the C. elegans zygote proceeds via distinct establishment and maintenance phases. Development. 2003;130:1255–1265. doi: 10.1242/dev.00284. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Dickinson D.J., Goldstein B. CRISPR-based methods for Caenorhabditis elegans genome engineering. Genetics. 2016;202:885–901. doi: 10.1534/genetics.115.182162. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ghanta K.S., Mello C.C. Melting dsDNA donor molecules greatly improves precision genome editing in Caenorhabditis elegans. Genetics. 2020;216:643–650. doi: 10.1534/genetics.120.303564. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Rau K.R., Guerra A., et al. Venugopalan V. Investigation of laser-induced cell lysis using time-resolved imaging. Appl. Phys. Lett. 2004;84:2940–2942. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Rau K.R., Quinto-Su P.A., et al. Venugopalan V. Pulsed laser microbeam-induced cell lysis: time-resolved imaging and analysis of hydrodynamic effects. Biophys. J. 2006;91:317–329. doi: 10.1529/biophysj.105.079921. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Quinto-Su P.A., Lai H.-H., et al. Venugopalan V. Examination of laser microbeam cell lysis in a PDMS microfluidic channel using time-resolved imaging. Lab Chip. 2008;8:408–414. doi: 10.1039/b715708h. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Noack J., Vogel A. Laser-induced plasma formation in water at nanosecond to femtosecond time scales: calculation of thresholds, absorption coefficients, and energy density. IEEE J. Quantum Electron. 1999;35:1156–1167. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Huang G., de Jesus B., et al. Doonan R. Improved CRISPR/Cas9 knock-in efficiency via the self-excising cassette (SEC) selection method in C. elegans. MicroPubl. Biol. 2021;2021 doi: 10.17912/micropub.biology.000460. Published online September 16, 2021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Heppert J.K., Pani A.M., et al. Goldstein B. A CRISPR tagging-based screen reveals localized players in wnt-directed asymmetric cell division. Genetics. 2018;208:1147–1164. doi: 10.1534/genetics.117.300487. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Fan X., Henau S.D., et al. Griffin E.E. SapTrap assembly of Caenorhabditis elegans MosSCI transgene vectors. G3 (Bethesda) 2020;10:635–644. doi: 10.1534/g3.119.400822. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Poteryaev D., Squirrell J.M., et al. Spang A. Involvement of the actin cytoskeleton and homotypic membrane fusion in ER dynamics in Caenorhabditis elegans. Mol. Biol. Cell. 2005;16:2139–2153. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E04-08-0726. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Dhawan M.D., Wise F., Baeumner A.J. Development of a laser-induced cell lysis system. Anal. Bioanal. Chem. 2002;374:421–426. doi: 10.1007/s00216-002-1489-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Salehi-Reyhani A., Kaplinsky J., et al. Klug D. A first step towards practical single cell proteomics: a microfluidic antibody capture chip with TIRF detection. Lab Chip. 2011;11:1256–1261. doi: 10.1039/c0lc00613k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Rodriguez J., Peglion F., et al. Goehring N.W. aPKC cycles between functionally distinct PAR protein assemblies to drive cell polarity. Dev. Cell. 2017;42:400–415.e9. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2017.07.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Li J., Kim H., et al. Kemphues K.J. Binding to PKC-3, but not to PAR-3 or to a conventional PDZ domain ligand, is required for PAR-6 function in C. elegans. Dev. Biol. 2010;340:88–98. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2010.01.023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Joberty G., Petersen C., et al. Macara I.G. The cell-polarity protein Par6 links Par3 and atypical protein kinase C to Cdc42. Nat. Cell Biol. 2000;2:531–539. doi: 10.1038/35019573. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Lin D., Edwards A.S., et al. Pawson T. A mammalian PAR-3-PAR-6 complex implicated in Cdc42/Rac1 and aPKC signalling and cell polarity. Nat. Cell Biol. 2000;2:540–547. doi: 10.1038/35019582. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Qiu R.G., Abo A., Steven Martin G. A human homolog of the C. elegans polarity determinant Par-6 links Rac and Cdc42 to PKCzeta signaling and cell transformation. Curr. Biol. 2000;10:697–707. doi: 10.1016/s0960-9822(00)00535-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Graybill C., Wee B., et al. Prehoda K.E. Partitioning-defective protein 6 (Par-6) activates atypical protein kinase C (aPKC) by pseudosubstrate displacement. J. Biol. Chem. 2012;287:21003–21011. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M112.360495. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

. The movie plays at actual speed.

Fluorescent images of a C. elegans zygote cytosolically expressing mNG::Halo followed by a brightfield view of the zygote being lysed with a single shot from the pulsed infrared laser. Fluorescent signal is monitored as the cytoplasm solubilizes and diffuses in the SiMPull buffer. Brightfield at the end of the movie demonstrates the cell lysate that remains in the field of view. The movie plays at 7 frames per second. Scale bar represents 10 μm.

Fluorescent images of a C. elegans zygote during pronuclear meeting expressing mNG::NPP-10 in the nuclear envelope followed by a brightfield view of the zygote being lysed with a single shot from the pulsed infrared laser. Fluorescent signal is monitored as the nuclear envelope solubilizes and diffuses in the SiMPull buffer. Brightfield at the end of the movie demonstrates the cell lysate that remains in the field of view. The movie plays at 7 frames per second. Scale bar represents 10 μm.

Fluorescent images of a C. elegans embryo expressing GFP::C34B2.10 in the endoplasmic reticulum (ER) by a brightfield view of the embryo being lysed with a single shot from the pulsed infrared laser. Fluorescent signal is monitored as the ER solubilizes and diffuses in the SiMPull buffer. Brightfield at the end of the movie demonstrates the cell lysate that remains in the field of view. The movie plays at 7 frames per second. Scale bar represents 10 μm.

Fluorescent images of a C. elegans embryo expressing transmembrane protein MOM-5::mNG in the plasma membrane followed by a brightfield view of the embryo being lysed with a single shot from the pulsed infrared laser. Fluorescent signal is monitored as the plasma membrane solubilizes and diffuses in the SiMPull buffer. Brightfield at the end of the movie demonstrates the cell lysate that remains in the field of view. The movie plays at 7 frames per second. Scale bar represents 10 μm.

Fluorescent images of a C. elegans embryo expressing transmembrane protein MOM-5::mNG in the plasma membrane followed by a brightfield view as the middle-top cell of the embryo is lysed with a single shot from the pulsed infrared laser. Fluorescent signal is monitored as the plasma membrane solubilizes and diffuses in the SiMPull buffer. Brightfield at the end of the movie demonstrates the cell lysate that remains in the field of view. The movie plays at 7 frames per second. Scale bar represents 10 μm.

Fluorescent images of a C. elegans embryo expressing outer mitochondrial membrane marker tomm- 20::GFP followed by a brightfield view of the embryo being lysed with a single shot from the pulsed infrared laser. Fluorescent signal is monitored as the mitochondria somewhat solubilizes and diffuses in the SiMPull buffer. Brightfield at the end of the movie demonstrates the cell lysate that remains in the field of view. The movie plays at 7 frames per second. Scale bar represents 10 μm.

Time-lapse of mNG::HaloTag molecules appearing at the coverslip. Magenta is Halo ligand JFX646; Green is mNeonGreen. TIRF acquisition begins 11 seconds after cell lysis. The movie plays at 10 frames per second, and each frame is an average of 50 frames (1s) of actual data. Thus, each 1s of the movie represent 10s of actual data acquisition. Scale bar represents 10 μm.

Time-lapse of mNG::aPKC molecules binding to the coverslip and forming complexes with PAR- 6::HaloTag molecules. Magenta is endogenous PAR-6::HaloTag bound to Halo ligand JFX650; Green is endogenous mNeonGreen::aPKC. TIRF acquisition begins 5 seconds after cell lysis. The movie plays at 10 frames per second, and each frame is an average of 50 frames (1s) of actual data. Thus, each 1s of the movie represent 10s of actual data acquisition. Scale bar represents 10 μm.