Abstract

Background

Pursuing the vision ‘for a good life in an attractive region,’ the Region Jönköping County (RJC) in Sweden oversees public health and health-care services for its 360 000 residents. For more than three decades, RJC has applied ‘quality as strategy,’ which has included increasing involvement of patients, family and friends and citizens. This practice has evolved, coinciding with the growing recognition of co-production as a fundamental feature in health-care services. This study views co-production as an umbrella term including different methods, initiatives and organizational levels. When learning about co-production in health-care services, it can be helpful to approach it as a dynamic and reflective process.

Objective

This study aims to describe the examples of key developmental steps toward co-production as a system property and to highlight ‘lessons learned’ from a Swedish health system’s journey.

Method

This qualitative descriptive study draws on interviews with key stakeholders and on documents, such as local policy documents, project reports, meeting protocols and presentations. Co-production initiatives were defined as strategies, projects, quality improvement (QI) programs or other efforts, which included persons with patient experience and/or their next of kin (PPE). We used directed manifest content analysis to identify initiatives, timelines and methods and inductive conventional content analysis to capture lessons learned over time.

Results

The directed content analyses identified 22 co-production initiatives from 1997 until today. Methods and approaches to facilitate co-production included development of personas, storytelling, person-centered care approaches, various co-design methods, QI interventions, harnessing of PPEs in different staff roles, and PPE-driven improvement and networks. The lessons learned included the following aspects of co-production: relations and structure; micro-, meso- and macro-level approaches; attitudes and roles; drivers for development; diversity; facilitating change; new perspectives on current work; consequences; uncertainties; theories and outcomes; and regulations and frames.

Conclusions

Co-production evolved as an increasingly significant aspect of services in the RJC health system. The initiatives examined in this study provide a broad overview and understanding of some of the RJC co-production journey, illustrating a health system’s approach to co-production within a context of long-standing application of QI and microsystem theories.

The main lessons include the constancy of direction, the strategy for improvement, engaged leaders, continuous learning and development from practical experience, and the importance of relationships with national and international experts in the pursuit of system-wide health-care co-production.

Keywords: co-production, co-design, health-care organization, patient involvement, quality improvement

Introduction

Region Jönköping County (RJC) in Sweden is responsible for public health and health-care services for its 360 000 residents and provides those services through a tax-financed, population-based, integrated health-care system. Pursuing the RJC vision ‘for a good life in an attractive region,’ the system has used ‘quality as strategy’ as a guiding principle for decades [1–3]. The strategy has included increasing involvement of, and co-production with, patients, next of kin and citizens. This strategy has evolved, mirroring and promoting the emergence of co-production as a fundamental feature in health-care services around the world, and reflects the reframing of health-care services as being driven more by service logic than product logic [4]. According to Osborne et al. [5], co-production refers to the contribution of users to the design and provision of services and can be defined as the voluntary or involuntary involvement of users in the design, management, delivery and/or evaluation of services. There is no definitive nomenclature; several terms and concepts associated with co-production include patient participation, patient collaboration, patient involvement, partnership, patient empowerment, person-centered care, co-creation and co-design [4, 6, 7]. In the diversity and variation, the meaning and scope of co-production can change in relation to services, performance, by whom and for which purpose [8].

In this study, we view co-production as an umbrella term that can include several methods, initiatives and organizational levels. We will refer to patients and their family and friends as ‘persons with patient experience’ (PPEs). Filipe et al. [8] describe the importance of relating challenges and stakes to what is being co-produced and implications for participants. Furthermore, they suggest ‘One way of going about the co-production of health care more meaningfully is to look at it as a dynamic, experimental, and reflective process sustained by different forms of engagement, interactions, and social relations’ ([8], p. 5). In that spirit, this study aims to describe developmental steps toward co-production and to highlight ‘lessons learned’ from a Swedish health system’s journey.

Methods

This qualitative descriptive study [9, 10] draws on interviews and documents, in three sequential steps (Table 1). We define co-production initiatives as strategies, projects, quality improvement (QI) programs or other continuous efforts involving PPE.

Table 1.

Overview of study focus, process, method, sampling and analyses

| Study focus | Examples of co-production initiatives identified | Time frame and methods used | Development and lessons learnt |

|---|---|---|---|

| Process | Step 1: identification of initiatives with PPE | Step 2: connections of initiatives to methods and time period | Step 3: descriptions of development and changes over time in the initiatives |

| Method and analysis | Qualitative-directed manifest: searching for initiatives with PPE | Qualitative-directed manifest: searching the text for time and methods (explicit or implicit) related to the initiatives identified in Step 1 | Qualitative inductive conventional content analyses |

| Sampling | - Interviews (n = 2) - Business plans (2014–2019) - Presentations of the development of person-centered care and co-production made in RJC |

Snowball sampling of program documents and reports related to the findings in Step 1 Additional purposeful sampling, interviews (n= 3) |

Business plans 2014–2019 and interviews from Steps 1 and 2 (n = 5) |

The interviews in Step 1 with two key stakeholders at macro- and meso-levels were previously recorded in an evaluation of co-production initiatives and were re-analyzed for this study. One of those informants has played a key role in the RJC co-production journey and contributes as co-author (A.K.) of this paper to help guide the research and validate findings. The business plan sampling was limited to plans available on web pages within RJC at the time of the search (fall 2020).

In Step 2, we searched (fall 2020) for documents based on title and/or keywords related to the identified initiatives on internal and external RJC web pages. When documents on known initiatives were unavailable or did not answer the study questions, we performed additional interviews (n = 3) with key stakeholders identified through purposeful sampling [11] made by research team members familiar with the context. The informants gave oral informed consent to participate voluntarily. The interviews concerned descriptions of the initiatives and their relation to co-production, development and lessons learned.

We combined two complementary approaches to content analyses: deductive directed content analysis and inductive conventional content analysis [12]. The directed content analysis is suitable when using predetermined categories; in this case, ‘initiatives,’ ‘timelines’ and methods. The conventional content analysis, on the other hand, concerned ‘lessons learned’ and/or ‘development’ over time, since this approach is suitable for gaining new insights into a phenomenon. For the inductive conventional content analysis, we identified key concepts in the documents and interview data (both transcripts and sound files) and then sorted them into groups with related content. Key concepts were coded according to the method (one code consists of at least two key concepts). Codes were then sorted into categories and organized into clusters [12]. The document and interview analyses were primarily performed by an inside RJC researcher (S.P.), but they were discussed and overseen closely by one of the researchers (A.C.A.) not employed by the RJC and with well-documented and broad experience of qualitative analyses.

Results

Co-production initiatives, methods and time frames

The deductive analyses resulted in 22 co-production initiatives. Through subsequent data analyses, we ordered the initiatives chronologically and identified their approaches/methods (Table 2). The co-production methods were not explicit in all of the documents, so we interpreted the content and connected to tools or methods aimed at facilitating involvement and/or include co-production in the initiatives.

Table 2.

Co-production initiatives, timeline and methods

| Co-production initiatives | Timeline | Description and stated or inferred method |

|---|---|---|

| Esther | 1997 to ongoing | A person-centered approach that started from the guiding question: What is best for Esther? Focusing on the needs of the elderly population with complex and multifaceted needs. Development of personas and storytelling aiming at facilitating person-centered care together with quality improvement methods and tools. The work relates to a variety of different co-production/co-design methods that have been developed over time |

| The child dialogue | 2001 to ongoing | Development of an integrated health system for child health with the needs of the child and family in focus. QI principles and complex adaptive system theory guided the efforts. A wide range of stakeholders, schools, public health, health care, oral health, social care and many more are engaged. Patients, family members or citizens have guided directions and sometimes led activities. A similar approach has later been developed for the elder population in Senior Dialogue. Relates to co-design methods |

| Pharmaceuticals project | 2004, 2007, 2011 | Invitation of users to participate in dialogues on pharmaceutical use in three different programs. The idea was that involvement of end users can improve process and documentation of action plans in improving drug handling. Relates to co-evaluation |

| Passion for life | 2005 to ongoing | A program aiming to create conditions for a healthy life of high quality for the older people using QI tools and a group/network approach with facilitators. The concept also was developed for a younger population named ‘more to life’ (2008). Relates to co-design and collaborative QI methodology |

| The Ryhov hospital self-dialysis unit | 2005 to ongoing | A concept development that started from a single patient’s initiative, with patients and health-care professionals collaboratively developing self-dialysis whereby patients learn to master all aspects of their hemodialysis. Relates to co-design, person-centered care and co-production of health-care services |

| Patient safety program | 2006–2012 | Storytelling was used and developed in relation to how patients can co-produce safety in health care. This was applied in both leadership meetings, mesosystem-level development programs and microsystem-level everyday work. Method of storytelling and person-centered care |

| Learning cafés | 2007 to ongoing | A meeting place based on a health pedagogy model where patients and their loved ones learn about their disease from their own perspective, questions and situation (a shift from diagnosis-oriented schools starting from the professionals’ perspectives). Developed with inspiration of health pedagogy model by Landtblom, Vifladt and Hopen [13]. Relates to co-design |

| PEERs (people with lived experience of a mental illness) | 2010 to ongoing | A network of persons with patient experience in psychiatric care with skills to participate in education and development efforts in different ways. Started with co-production work designing training in recovery-oriented approaches in psychiatry. All peers have some training in recovery orientation and peer education. Relates to co-design |

| Colon cancer—improvement work | 2010–2012 | A demonstration improvement collaborative, supported by RJC, to pursue promises on person-centered care involving health-care professionals, patients and their families, researchers, payers (leaders), planners and educators spanning multiple organizational boundaries across RJC and two adjacent regions QI methods including patient representation in the team relate to co-production in QI initiatives |

| Together part I | 2010 | A collaborative QI improvement approach aiming at actively include patients ‘and relatives’ experiences and knowledge in health-care QI work and patient safety. The aim also was to develop methods and learnings on coproduction to facilitate reaching the overall aim, which was, by December 2010, patient/user participation will be a natural part in the County Council’s development work. Relates to co-production in QI initiatives |

| Together part II | 2011 | An improvement work in the psychiatric care with an improvement group consisting of patient and professional representatives working together through a quality improvement process with QI facilitators. Co-design approach in QI initiatives |

| Patient supporters | 2012 to ongoing | A person with own patient experience identified the need of and facilitated the development of the patient supporter role in RJC. A patient supporter is a staff member with the role of supporting other patients. It can regard information about a process, treatment or operation from a patient perspective. They have a broad experience of many patients’ different experiences (in addition to their own). Staff can also benefit from patient supporters asking for their knowledge and perspectives. Relates to persons with patient experience as staff resources |

| Breakthrough collaboratives on heart failure and quality of care | 2013–2014 2015 |

A national breakthrough collaborative with patient participation in the team. RJL teams participated with patients. In addition, improvement advisors from RJC also participated and facilitated the national initiative overall. RJC participated in two collaboratives. A co-design and collaboration approach in QI initiatives |

| Dialogue meetings with patient organizations and RJC politicians | 2015 to ongoing | Development of regular and structured dialogues between politicians and patient organization A facilitated macrosystem-level dialogue initiative creating shared meeting places |

| Together for best possible health and equal care | 2016 to ongoing | A systems approach to move most health care closer to the inhabitants. An overall approach with initially 23 subprojects. Persons with patient experiences are involved in the strategic meeting places. A variety of co-production tools and methods are developed and used. Personas from different population segments were developed on a strategic level to illustrate the needs from different perspectives. Relates to various co-production methods |

| The Living Library | 2016 to ongoing | The development unit’s response to increased demands for patient representatives to participate in QI initiatives from around the RJC, prompted the creation of a ‘Living Library’ of persons with patient experience. The Living Library consists of persons with own patient experience. They are trained to provide patient perspectives in improvement efforts, give lectures, support other patients, participate in educations, contribute with storytelling and driving development projects. Qulturum, RJC’s development and innovation center, coordinates the Living Library |

| The House of Hearts— meeting place for persons and loved ones living with cancer | 2016 to ongoing | A meeting place for persons living with cancer and/or their family and friends. Designed and developed by a former cancer patient with support from RJC initially; later further developed with additional external funding. This is an example of persons with patient experience driving own initiatives |

| PEER—supporters in psychiatric care | 2018- ongoing | An addition to the PEER network described earlier, a new role with extended education and professionalization was developed. The peer supporter is part of the staff group at a clinic and participates in the ongoing work, mainly working with PEER patient support and participates in the everyday development work in the organization. In RJL, the peer supporter is a person with own patient experience who has a specific education in recovery- oriented approach in psychiatric care. Relates to co-design and further development of persons with patient experience as staff |

| Patient contract | 2018 to ongoing | Patient contract started as a national initiative that RJC adopted as a central component in developing health-care co-production. The patient contract concept has four parts: (1) shared agreement between patient and professional(s), (2) shared understanding of the suitable time for a next contact, (3) a jointly agreed comprehensive, coordinated care plan and (4) care continuity through a named person to contact. The RJC approach to patient contracts is co-designed by persons with patient experience, improvement advisors and health-care professionals |

| International collaboration and communities of practice | 2018 to ongoing | International benchmarking and development of co-production knowledge with two cases in a learning network. Patient contract (2018–2019) and a clinical case regarding value creation for and with persons with multiple sclerosis (2019). Patient participation in different ways involving different methods. Interactive research programs are connected to both initiatives. Relates to several approaches: co-design, collaborative QI, storytelling and personas |

| Integration of co-production in leadership and professional training | 2018 to ongoing | Evolution of how to convey understanding of co-production and its value more systematically in professional and leadership development programs in RJC. Continuous small-scale testing, with expert support from Professor Paul Batalden, at the Dartmouth Institute and Jönköping Academy, includes exploring the lived realities of patients and professionals. Relates to patients as ‘learning partners’ in exploring co-production of health-care services |

| Short-term self-managed hospitalization | 2018 to ongoing | Ongoing person-centered care program in mental health with short-term self-managed hospitalization, in RJC for persons with self-harming behavior. The self-managed hospitalization gives increased autonomy and an opportunity to retain personal responsibility for health and control over interventions. Relates to person-centered care and co-production of health-care services |

The initiatives varied regarding size, spread, organizational levels and duration. Some initiatives were system-wide, engaged all organizational levels (i.e. micro-, meso-, and macrosystem levels) and included many sub-interventions over several years. Other initiatives were local, limited to a specific care setting and time frame, engaging only one organizational level. Some initiatives evolved, going from one setting and/or organizational level to several and/or from using one method to using many.

Development and lessons learned

The analysis of the five stakeholder interviews and RJC business plans from 2014 to 2019 resulted in 10 clusters (Table 3), further explained below.

Table 3.

Categories and clusters captured by the conventional content analyses of changes, lessons learned and development in co-production initiatives

| Categories | Clusters |

|---|---|

| Preparations and expectations Structure and tools Facilitate conversations and relations |

1. Relations and structure |

| Macrolevel, consistency, support and personas Microsystem person-centered care Mesosystem-level approaches with PPE participants in QI work |

2. Micro-, meso- and macrolevel approaches |

| Challenging views on roles Reciprocity in relations Assumptions on patients’ competences and skills |

3. Attitudes and roles |

| Increased demand/request PPE initiates and leads Methods and theory development (local, national and international) |

4. Drivers for development |

| From one patient story to many Variety of methods, settings and context Numbers and roles of persons with patient experience |

5. Diversity |

| Shared purpose Meeting places and training Support through dialogues and good examples |

6. Facilitating leadership |

| View on context, inequities and lived experiences Recognition of the assets of all Microsystem from health care to patients |

7. New perspectives on current work |

| Professional roles Responsibilities (for patient safety and clinical outcomes) What works for whom and when? |

8. Uncertainties and risks |

| Better health and health care Reduced need for health-care services and increased autonomy Value creation—service development |

9. Theories and outcomes |

| Legislation—the Patient Act National agreements and fundings Continuity and changes in business plans |

10. Regulations and frames |

Relations and structure

Interviews revealed the importance for both professionals and PPEs of being prepared for co-production. A clear intention with the initiative and expectations articulated beforehand facilitated co-production. Over time, more standardized preparation processes were developed in some initiatives. For example, the Living Library developed a standardized process and preparation documents with information about context and expectations. The importance of both structured approaches and relationship-building efforts such as engaging with people in meeting places for informal conversations, facilitating dialogues between PPEs and professionals and follow-up dialogues were described.

Macro-, meso- and microsystem-level perspectives

Different approaches to co-production at micro-, meso- and macrosystem levels were described. In the macrosystem-level dialogues, participation in meetings and systematic use of personas and narratives aimed at connecting strategies to lived experiences of inhabitants were identified. Over time, increased number of personas were used. In a microsystem perspective, storytelling and complementary approaches, e.g., co-design, service design and agreements, were used, often aimed at facilitating person-centered care in everyday work. In the mesosystem perspective, storytelling, training, interviews, simulation and development of co-production and co-design in QI were identified.

Attitudes and roles

This concerns the professional’s view of a patient’s capacity and resources in relation to their own health, treatment and disease and the view of PPEs’ role and contribution in QI. All informants highlighted attitudes in some way. Attitudes often shifted over time toward recognizing the PPE competences and skills. Resistance related to PPEs’ involvement existed in some of the initiatives. Interventions that could facilitate egalitarian relations included going on a field trip together, receiving support from leaders and from facilitators. Sometimes, financial compensation was important for the PPEs, while at other times, it was of less or of no importance. Payment could contribute to the PPEs’ sense of reciprocity in relations.

Drivers for development

Positive experiences in early initiatives generated increased interest in, and requests for, inclusion of PPEs in subsequent organizational development efforts. The increased requests for PPE inclusion prompted development of the Living Library, which eventually became a driver for co-production work itself. Another example included the introduction of co-production and support with PPEs for training in recovery-oriented approaches in psychiatry (a method that included co-production). Such drivers spurred development of the PEER (people with lived experience of a mental illness) network and later of PEER supporters. Engaged PPEs promoting their own initiatives were given platforms and opportunities to develop meeting places such PPE professional roles. The competencies and number of persons in these initiatives increased over time. Increased interest in co-production in health care internationally and nationally also served to boost the local co-production efforts.

Diversity

The informants described PPE engagement in different settings and contexts. Initially, one or two PPEs and their stories became ‘the patient’ in improvement initiatives, but, over time, it became clear that that this approach was too limited and not sustainable. Some informants highlighted that using too few or the same PPE in ‘all’ situations introduced a risk that stories/experiences might not be equally relevant over time and/or that the group might become too ‘homogenous,’ thereby excluding others. Instead, they highlighted the importance of diversity of experiences, skills, views and perspectives for co-production. A growing number of PPEs engaged over time, and the expansion from one persona (Esther) to a whole network of personas—Esther and her daughter Britt-Marie, surrounded by their family and network of 10 diverse personas representing different needs in the RJC population—illustrates this. Both individual engagements between PPEs and professionals developing their own co-production approaches as well as using more established co-production theories and methods existed.

Facilitating leadership

The role of senior leadership in facilitating change toward more co-production involved creating shared purpose, providing meeting places and training opportunities for leaders, staff and PPEs alike. Leadership training programs included PPE participation, e.g. interviews of patients, PPEs in leadership meetings, storytelling and small-scale testing with co-production theories in education. Leaders’ interest in co-production, expressed by asking questions on how co-production initiatives were developing, was important. Questions related to shifting the perspective from ‘doing for’ to ‘doing with’ patients. This could be challenging for both professionals and patients who were used to the ‘doing for’ perspective; the doing ‘with’ always had to start from the patient’s needs and resources. Additional facilitating leadership strategies included benchmarking and sharing good examples.

New perspectives on current work

The integration of co-production with the tradition of QI and microsystem thinking in RJC grew from practical experiences of including PPEs in initiatives toward thinking more of the patient’s microsystem than of the health-care organization’s microsystem including the patient. Patient’s microsystem involved more focus on individual needs and resources in designing health-care services. There were a shift from asking how patients experience health-care processes to curiosity about the patients’ lived experiences. Not only merely of healthcare encounters but from life in general, with their particular set of health conditions and treatments. Efforts to understand more about the PPEs resources as a complement to needs were described. Development of new ways of working was based on practical experiences in different contexts, methods and theories.

Uncertainties and risks

New ways of working with person-centered care and PPE generated concerns about potential unintended, undesired outcomes such as patient safety risks due to reduced professional oversight of care services. For example, stakeholders worried about adverse effects on clinical outcomes when patients take greater responsibility for treatment; they expressed needs for further knowledge on what works (or does not work) for whom and under what circumstances. This highlighted the related risks of overburdening PPEs when co-production responsibilities are added on top of their burden of illness. The informants described needs for evaluation and follow-up from different perspectives, and the system hosted and supported several research programs related to some of the initiatives.

Theories and outcomes

Outcomes related to co-produced health-care services were preliminarily described in terms of reduced need for health care, increased patient autonomy and strengthening of PPEs’ own resources. From a macrosystem perspective, the theory was that increased co-production can lead to better health and health care. The informants noted difficulties in measuring outcomes of co-production initiatives and the need for better evaluation capacity including both qualitative and quantitative data collection. Descriptions of increased well-being for PPEs when participating were identified in some initiatives.

Regulations and frames

Analysis identified national regulation, such as The Swedish Patient Act as supporting the patient’s position and rights. Some of the initiatives were developed with funding from the national government, supported by RJC and included explicitly in RJC annual business plans. This context of national support and funding and the local support facilitated the work at the mesosystem level. The initiatives included in the business plans could vary, but the direction was clear in the documents from 2014 to 2019, aiming at strengthening patients’ roles and helping patients participate in further development of co-production and co-evaluation of health-care services.

Discussion

Principal findings

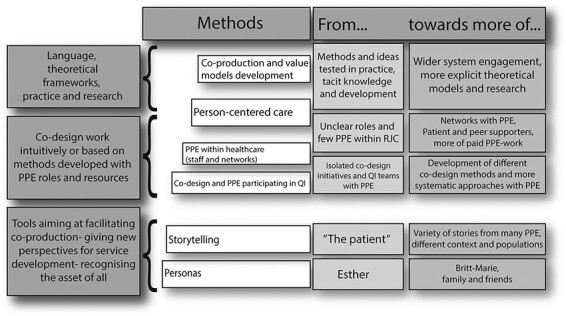

Co-production of RJC health-care services has evolved and grown over time. With hindsight, it becomes clear how co-production has become a more integral and fundamental part of the system’s work across all levels, from microsystems to the macrosystem. In previous studies of RJC [3], patient involvement initiatives were found to be developed within the ‘quality as strategy’ approach. We now further illuminate some of the methods and key development perspectives that we identified regarding co-production in RJC (Figure 1). Some of the examples (as the Esther network and the recovery-oriented initiatives) have generated a lot of learning and development regarding methods, competences and co-design approaches that influenced many parts of, and other initiatives in, the system over time. The development can be viewed as a continuous, dynamic, process with both system approaches and isolated ‘chunks,’ all serving to increase co-production over time.

Figure 1.

Visualization of key developmental steps, methods and process direction found over time in this study.

Strengths and limitations

This study has captured distinctive examples of co-production in the system and a range of lessons learned in a systematic way. The initiatives identified in this study do not give a complete picture of all the co-production work and related lessons learned within RJC. Using mostly preexisting documents can lead to capturing only a fraction of a complex reality [14]. In complex adaptive systems, some things will always remain unknowable [15]. The additional interviews performed for this study add important perspectives beyond the documents reviewed, which strengthens the study’s credibility [16]. Our definition of co-production initiatives was deliberately broad, to allow greater flexibility and avoid conflicting assumptions about what exactly co-production is or is not in the health-care context [8]. This broader definition also allowed us to study initiatives that did not explicitly involve co-production from the start but where valuable insights into co-production nevertheless emerged over time. There is a risk of overlooking important development steps toward co-production if narrowing the definition, since co-production can emerge and build on engagement and involvement even without a specific initial plan to orchestrate co-production [17]. The authors’ analyses of methods in the initiatives have limitations since the methods were not explicit in all initiatives, a framework on how to extract and define tacit theories/methods could have strengthened the transparency in the analysis of related methods. Related quantitative measures available in the system in relation to the co-production initiatives and findings could have added another perspective and strengthened the study.

Interpretation within the context of the wider literature

Research examining a health system’s approach to co-production—including interventions and interactions at macro-, meso- and microsystem levels—appears to be limited. Methods and tools for co-production and co-design in health care are more often described in microsystem settings than in large system perspectives. This study indicates the importance of a long-term strategic approach, combining QI opportunities and innovative ‘chunks’ to develop in microsystems with a strategic management approach such as the RJC’s ‘quality as strategy’ [1, 3].

In the cluster ‘relations and structure,’ the development of roles and expectations can relate to the models for inclusive co-production by Clarke et al. [18], who describe the importance of clear roles and expectations in co-production. The importance of payment for PPE participants resembles the findings by Filipe et al. [8] that payment can engender more equal relations and facilitate PPE inclusion, but that different persons vary in their view of its importance. While it is important to be aware of asymmetries in co-production relations, it is not always easy to manage them [19]. In the RJC co-production development journey, various efforts were made to facilitate balanced relations, including preparations, support by facilitators and leaders and field trips.

In some initiatives, the language and theories of co-production were not made explicit, perhaps because these ways of working developed gradually. However, our findings indicate increasing awareness of previously implicit program theories [20]. Moreover, resources to facilitate co-production increased over time, for example, the growing number of PPEs involved in the system and the addition of methods and systematic approaches to co-production. As Davidoff et al. [20] observe, informal theory is always at work in improvement, even if practitioners often are not aware of it or make it explicit. This applies also to co-production, i.e. some initiatives are developed sequentially in practice without any explicit theory a priori.

The challenge of measuring and evaluating the effects of co-production is not unique, and future studies on co-production should include and link to clinical outcomes, service outcomes and cost-effectiveness [21]. Another perspective is that ‘co-productive experiments are best seen as generative processes that are less about delivering predictable impacts and outputs and more about developing new communities, interactions, practices, and different modes of knowledge and value production’ ([8], p. 5). The co-production journey of RJC, illuminated in this study, is a unique example of such a generative process even as it has yielded lessons learned that may apply in other contexts, with appropriate adaptation.

Implications for policy, practice and research

Research has been, and continues to be, connected to some of the interventions described. To fully understand how to harness co-production as a strategy for improving care, more in-depth insights into mechanisms, and more longitudinal research close to practice development, will be crucial. Service development to meet different needs in the population, including digital services, is another area of interest for further studies in the context of co-production of health-care services and their value.

Conclusions

The RJC ‘quality as strategy’ orientation encouraged patient involvement early on, which, in turn, revealed the importance and value of co-producing services with persons meant to benefit from them. This gradual shift from merely designing ‘for’ patients to co-designing services ‘with’ them, and a range of co-production initiatives, evolved over time. The initiatives examined in this study provide a broad overview and understanding of some of the RJC co-production journey, illustrating a health system’s approach to co-production within a context of long-standing application of QI and microsystem theories. The main lessons include the constancy of direction, the strategy for improvement, engaged leaders, continuous learning and development from practical experience, and the importance of relationships with national and international experts in the pursuit of system-wide health-care co-production.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank all participants who contributed to the study, with special thanks to Mats Bojestig, Director of Health Care in Region Jönköping County, and Göran Henriks, Chief Executive of Learning and Innovation at Qulturum, Region Jönköping County.

Contributor Information

Sofia Persson, Jönköping Academy, Jönköping University, Box 1026, Jönköping 55111, Sweden; Region Jönköping, Box 1024, Jönköping 55111, Sweden.

Ann-Christine Andersson, Jönköping Academy, Jönköping University, Box 1026, Jönköping 55111, Sweden; Department of Care Science, Malmö University, box 50500, Malmö 20250, Sweden.

Annmargreth Kvarnefors, Region Jönköping, Box 1024, Jönköping 55111, Sweden.

Johan Thor, Jönköping Academy, Jönköping University, Box 1026, Jönköping 55111, Sweden.

Boel Andersson Gäre, Jönköping Academy, Jönköping University, Box 1026, Jönköping 55111, Sweden; Region Jönköping, Box 1024, Jönköping 55111, Sweden.

Funding

Funding for dedicated research time for S.P. was provided by Futurum (The Academy of Health and Care, Region Jönköping) and the Center for Co-production, School of Health Sciences, Jönköping University.

Data availability

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author (S.P.) upon reasonable request.

Ethics

Three of the researchers are employed by the RJC where the study was conducted, which could create a risk for bias. On the other hand, being familiar with the RJC context from ‘within’ over time is probably irreplaceably helpful when performing this kind of study. Their pre-understanding and connection to local practice can strengthen the accuracy in identifying and interpreting the data. To minimize the risk of bias from partisan views, the inside-RJC researchers and outside researchers continuously discussed data sampling and analysis to prevent selective or unbalanced reporting.

References

- 1. Andersson-Gäre B, Neuhauser D. The health care quality journey of Jönköping County Council, Sweden. Qual Manag Health Care 2007;16:2–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Bodenheimer T, Bojestig M, Henriks G. Making systemwide improvements in health care: lessons from Jönköping County, Sweden. Qual Manag Health Care 2007;16:10–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Staines A, Thor J, Robert G. Sustaining improvement? The 20-year Jönköping quality improvement program revisited. Qual Manag Health Care 2015;24:21–37. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Batalden M, Batalden P, Margolis P. et al. Coproduction of healthcare service. BMJ Qual Saf 2015;25:509–17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Osborne SP, Radnor Z, Strokosch K. Co-production and the co-creation of value in public services: a suitable case for treatment? Public Manag Rev 2016;18:639–53. [Google Scholar]

- 6. Longtin Y, Sax H, Leape LL. et al. Patient participation: current knowledge and applicability to patient safety. Mayo Clin Proc 2010;85:53–62. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Bergerum C, Thor J, Josefsson K. et al. How might patient involvement in healthcare quality improvement efforts work—a realist literature review. Health Expect 2019;22:952–64. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Filipe A, Renedo A, Marston C. The co-production of what? Knowledge, values, and social relations in health care. PLoS Biol 2017;15:e2001403. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Creswell J. Qualitative Inquiry and Research Design. Choosing among Five Approaches. Thousand Oaks: Sage, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 10. Willis DG, Sullivan-Bolyai S, Knafl K. et al. Distinguishing features and similarities between descriptive phenomenological and qualitative description research. West J Nurs Res 2016;38:1185–204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Emmel N. Sampling and Choosing Cases in Qualitative Research: A Realist Approach. London: Sage, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 12. Hsieh HF, Shannon SE. Three approaches to qualitative content analysis. Qual Health Res 2005;15:1277–88. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Landtblom A-M. Hälsopedagogik för vårdare och brukare i samarbete: en introduktion till bemästrande. Vifladt EH, Hopen L (eds). Stockholm: Bilda förlag, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 14. Flick U. The SAGE Handbook of Qualitative Data Analysis. London: Sage Publications, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 15. Plsek PE, Greenhalgh T. The challenge of complexity in health care. BMJ 2001;323:625–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Lincoln YS. Naturalistic Inquiry. Lincoln YS, Guba EG (eds). Beverly Hills: Sage Publications, 1985. [Google Scholar]

- 17. Bovaird T. Beyond engagement participation: user and community coproduction of public services. Public Adm Rev 2007;67:846–60. [Google Scholar]

- 18. Clarke J, Waring J, Timmons S. The challenge of inclusive coproduction: the importance of situated rituals and emotional inclusivity in the coproduction of health research projects. Soc Policy Adm 2019;53:233–48. [Google Scholar]

- 19. Ärleskog C, Vackerberg N, Andersson A-C. Balancing power in co-production: introducing a reflection model. Unpublished manuscript, Jönköping University.

- 20. Davidoff F, Dixon-Woods M, Leviton L. et al. Demystifying theory and its use in improvement. BMJ Qual Saf 2015;24:228. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Clarke D, Jones F, Harris R. et al. What outcomes are associated with developing and implementing co-produced interventions in acute healthcare settings? A rapid evidence synthesis. BMJ Open 2017;7:e014650. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author (S.P.) upon reasonable request.