ABSTRACT

In Canada, unhealthy diets are associated with several chronic conditions, such as type 2 diabetes, cardiovascular disease, and obesity, and thus negatively impact the health and well-being of Canadians. Consequently, unhealthy diets are associated with an increased risk of morbidity and mortality in Canada. Recently, plant-based diets have gained in popularity due to their ability to provide a diet that is nutritionally adequate and health-conscious in addition to supporting environmental sustainability. The adoption of plant-based diets may address the substantial need to improve the health and well-being of Canadians, while also having a positive global environmental impact such as reducing greenhouse gas emissions. The aim of this scoping review was to identify current knowledge on the nutritional adequacy of plant-based diets and their relation with chronic conditions to support improved health and well-being of Canadians while identifying gaps in knowledge. Canadian peer-reviewed literature on diet, nutritional quality, and chronic conditions published between the years 2010 and 2020 were systematically examined. Sixteen articles met the inclusion criteria, with the majority pertaining to the relation between animal- or plant-based nutrition and cancer. Epidemiological studies support the practice of plant-based diets, in comparison to omnivore diets, as a strategy to improve nutritional adequacy and reduce the development of chronic conditions such as obesity, type 2 diabetes, cardiovascular diseases, osteoporosis, and select cancers such as endometrial, colorectal, and breast cancers. Overall, plant-based diets offer an opportunity to improve the health and well-being of Canadians while simultaneously working to counteract climate change, which may have a global reach. Gaps in knowledge were identified and mainly pertained to the lack of valid Canadian quantitative assessments of the long-term health impacts of plant-based diets. Further research should be completed to quantify the long-term health effects of the practice of a plant-based diet across all demographics of the Canadian population.

Keywords: plant-based nutrition, plant-based diet, vegetarian, omnivore, chronic conditions, health, wellness, diet, diet quality, Canada

Statement of Significance: The scoping review identifies and compiles current knowledge in the field of public health nutrition concerning the role of plant-based diets and the occurrence of chronic conditions in Canada. This review also identifies demographic and cultural gaps in knowledge among the research field of diet–disease relations in Canada and recognizes the need for further longitudinal data analysis.

Introduction

Food systems and individual dietary patterns have the potential to nurture human health and support environmental sustainability; however, this is often not attained (1). The influential role of food systems and individual dietary patterns has widely been determined to have a significant impact on human health outcomes, as food systems and dietary patterns are directly linked to the overall health and well-being of individuals. For perspective, unhealthy diets pose greater risk for morbidity and mortality in Canada than the combined impact of unsafe sex and the use of alcohol, drugs, and tobacco (2). In Canada, an unhealthy diet was identified as 1 of the 3 leading risk factors for chronic disease burden, and also plays a highly influential role in obesity, another leading risk factor for chronic diseases (1, 2). There is some variability in how the general public defines an “unhealthy” or a “healthy” diet (3, 4). This may result in confusion about how the general public perceives a healthy diet, which is particularly troublesome in Canada due to the high degree of cultural diversity (3, 4). Within the scientific community, a comprehensive definition of a healthy diet is widely accepted and supported by numerous public health authorities, such as Health Canada and the WHO, and academic journals such as The Lancet (1–3, 5, 6). According to the EAT-Lancet commission, the broad definition of a healthy diet is a diet that has high intakes of vegetables, fruits, whole grains, legumes, nuts, and unsaturated oils; moderate to low intakes of poultry and seafood; and very low or completely restricted intakes of red or processed meats, added sugar, refined grains, and starchy vegetables (1). Healthy and unhealthy dietary patterns can be further specified by the inclusion or exclusion of various animal products. Vegetarian and omnivore dietary patterns can both support a healthy diet, but as indicated in The Lancet’s definition of a healthy diet, a healthy diet should have a significant focus on plant-based foods and lean proteins. However, it is important to note that a diet must be adequately planned to ensure appropriate intake of all required nutrients regardless of dietary pattern, although this is critical with restricted dietary patterns such as plant-based diets (7). A well-balanced and adequately planned plant-based diet has been shown to be superior in comparison to an omnivore diet in various health outcomes (1, 2, 6, 8–23). A plant-based diet is generally defined as a diet that is largely focused on vegetable and fruit consumption with very limited or no intake of foods sourced from animals (1–3, 6, 7, 10, 12–14, 23, 24). Under the heading of plant-based diets, there are multiple styles of vegetarian dietary patterns that are defined based on their inclusion of specific animal products (1–3, 6, 7, 10, 12–14, 23, 24). For example, the most restrictive plant-based diet is a vegan diet, which restricts all animal products and by-products (1, 3, 6, 14, 23, 24). Other vegetarian dietary patterns include the lacto-ovo-vegetarian diet, which permits dairy and egg products, and the pesco-vegetarian diet, which permits seafood and fish (1, 14, 23, 24). On the other hand, an omnivore diet is defined by the inclusion of all animal products, along with vegetables, fruits, and grains (1, 3, 6, 7).

A well-planned plant-based diet, including adequate amounts of all essential nutrients, is sufficient throughout all stages of life (6, 7). As with any dietary regimen, there is potential to over- or under-consume essential nutrients (7). Traditionally, plant-based diets have ample intakes of magnesium, potassium, thiamin, riboflavin, folate, fiber, vitamin A, and vitamin C (6, 7, 24). However, plant-based diets also traditionally have lower intakes of vitamin B-12, calcium, vitamin D, zinc, iron, and dietary fats, such as long-chain omega-3 (n–3) fatty acids, saturated fats, and cholesterol (6, 7, 24). Among the nutrients of concern in a plant-based diet, vitamin B-12 and iron deficiency figure prominently (7). Plant-based foods do not contain a direct source of vitamin B-12 and diets high in folate can mask the hematological symptoms of deficiency, leading to serious health consequences (7). Rather than being related to adequate intake, concerns related to iron usually center around the bioavailability of iron sourced from plant-based foods (6, 7). Iron found in plant-based foods is nonheme iron, which has reduced bioavailability compared with heme iron found in animal foods (6, 7). Nonheme iron is more susceptible to both absorption-inhibiting compounds, such as phytates or calcium, and absorption-enhancing compounds such as vitamin C or organic acids; thus, nonheme iron can be adequately consumed and absorbed when plant-based diets are well planned (6, 7). On the other hand, aside from the lower amounts of select vitamins and minerals in a plant-based diet regimen, a plant-based diet provides a myriad of health benefits due to increased consumption of a variety of vitamins, minerals, and phytonutrients (6, 7). For example, phytonutrients such as carotenoids, flavonoids, and polyphenols provide a wide range of antioxidant and anti-inflammatory regulatory properties leading to many positive health outcomes (6). The nutrient advantages and disadvantages of plant-based diets can also be viewed from the perspective of an omnivore diet, as some animal-sourced foods have higher quantities of heme iron, calcium, vitamin B-12, and cholesterol (2, 6, 24).

The relation between dietary patterns and health outcomes has long been studied; however, with the continual influx of new information on diet–disease associations and the environmental impact of food systems, dietary recommendations for Canadians should be thought of as a continuum. Currently, plant-based diets are the center of attention for supporting the health of humans, animals, and the environment (1, 2, 25). For example, in comparison to omnivore diets, plant-based diets have been determined to have greater positive environmental impacts such as reductions in greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions and reduced land use as well as providing a healthier diet with reduced mortality rates (5). In addition to ongoing prospective epidemiological studies, retrospective analysis of various populations has also emphasized the advantages of plant-based diets. For example, people residing in the Okinawan region of Japan traditionally consumed a low-calorie, low-fat, and nutrient-dense plant-based diet and had one of the longest-lived populations, with low risks of age-related diseases and chronic conditions; however, when the Okinawan population began shifting towards a Western-style diet, their diet-related health benefits were reduced and their life expectancy declined (6). The Okinawan experience exemplifies the role of diet in the diet–disease relation. Furthermore, plant-based diets have been associated with other positive health indicators for chronic conditions. For example, in comparison to an omnivore dietary pattern, the practice of a plant-based diet results in lower total cholesterol, lower LDL cholesterol, improved glycemic control, improved blood pressure levels, and healthier BMI (1, 2, 14, 20, 23, 24).

Currently, Canada is experiencing the health, economic, and societal impact of chronic conditions in epidemic proportions. For example, according to the 2017 Canadian Community Health Survey, 34% of Canadians are overweight and 27% are obese and, according to the 2015/2016 Canadian Chronic Disease Indicator framework, ∼2.4 million Canadians had ischemic heart disease, 3.1 million had diabetes, and 2.2 million had been diagnosed with cancer (26, 27). The number of Canadians affected by these chronic conditions will continue to rise due to our aging population, sedentary lifestyles, and unhealthy dietary patterns (2, 26). Recently, increasing amounts of scientific evidence have classified plant-based diets as superior for supporting human health and wellness, as well as for limiting chronic diseases in comparison to an omnivore dietary pattern (1, 2, 6, 8–24, 28). This is seen in the recent publication of the 2019 Canadian Food Guide, as it recommends plant-based food options should be chosen more frequently to improve nutrient intakes and health (2). The support for plant-based nutrition stems from a variety of avenues, including not only human health but also animal and environmental health, thus supporting a holistic planetary health approach to human, animal, and environmental well-being (1, 2, 5). Although agriculture and environmental considerations differ between geographical locations, plant-based dietary patterns are associated with improvements in water use, GHG emissions, cropland use, nitrogen application, and phosphorus application compared with omnivore diets (1). Furthermore, the support for plant-based diets aligns with the third goal of the UN Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) for 2030, to “ensure healthy lives and promote wellbeing for all ages” (25). Due to the lack of a comprehensive review on available Canadian literature on this topic, a scoping review was conducted to systematically assess the available research completed in the area of plant-based nutrition focusing on the influential role of plant-based diets in Canada and their contribution to chronic conditions and nutritional adequacy to improve the health and wellness of Canadians. Additionally, the scoping review was conducted to identify existing knowledge gaps in the literature. The objective of this scoping review was to identify current knowledge on the nutritional adequacy of plant-based diets and their relation with chronic conditions to support improved health and well-being of Canadians while identifying gaps in knowledge and research.

Methods

The Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses extension for Scoping Reviews (PRISMA-ScR) was chosen as the review protocol (29). Necessary revisions were made to the protocol by the authors to ensure relevance to the project. The PRISMA-ScR guidelines can be accessed via webpage (URL: http://www.prisma-statement.org/Extensions/ScopingReviews) and additional understanding of the scoping review protocol was gained from the article written by Tricco et al. (29).

For sources to be included in the scoping review, they needed to include specific information with regard to plant- or animal-based nutrition and their contribution to diet quality and association with chronic conditions. A set of inclusion criteria was developed to guide the investigation and derive evidence (Table 1). Peer-reviewed journal articles were included if they met all inclusion criteria, were published between January 2010 and September 2020, and were written in English. Sources were excluded if they did not fit the inclusion criteria of the scoping review, such as sources that commented on perceptions, attitudes, or opinions of plant-based diets as well as review-style articles.

TABLE 1.

Inclusion criteria for the scoping review on plant-based diets in Canada and their role in optimal health and well-being

| Characteristic | Source inclusion criteria |

|---|---|

| Date published | Publication date that falls within the period of January 2010 to September 2020 |

| Publication status | Published literature including observational, experimental, and epidemiological studies; excluded review-style articles such as meta-analysis, systematic reviews, or scoping reviews |

| Language | Published in English |

| Study population | Research was conducted in adult humans or is in reference to adult humans |

| Research context—diet | Reports on plant-based diets, vegetarianism, veganism, and/or meat-based-diets |

| Research context—nutritional quality | Reports on nutritional density and the value of specific diets with a specific focus on the excess or lack of specific nutrients |

| Research context—disease outcomes | Reports on chronic condition outcomes including obesity, prediabetes or type 2 diabetes, osteoporosis or bone loss, elevated blood pressure, and/or cancer |

| Research context—location | Reports on research in Canada, on Canadians, or in a Canadian context |

| Access | Available as full-text online |

To ensure a comprehensive review of the literature, identification of all potentially relevant sources was achieved through a search of the following scientific literature databases using stated date parameters: Ovid MEDLINE, EMBASE, Web of Science, and Cochrane Library. The final search strategy used for Ovid MEDLINE can be found in Supplemental Appendix A. After finalizing the list of keywords and MeSH (Medical Subject Heading) descriptors, searches conducted on the remaining scientific literature databases were completed in a comparable manner. The search strategy was developed with assistance from Kevin Read, the University of Saskatchewan Health Sciences librarian, an expert in scoping and systematic reviews, and further refined through discussion with the authors. The final search results were exported into EndNote and duplicate sources were removed. Results from scientific literature databases were supplemented by searching key terms in Google while screening for relevance and eligibility. All searches were completed by ZLB and peer-reviewed by PK, GLL, and HV.

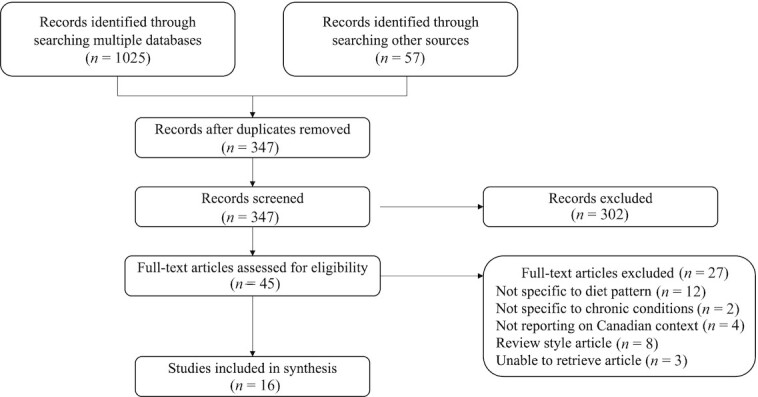

The screening process identified 1025 records via scientific databases and 57 records via the Google search engine. After removing duplicates, 347 records remained. In order to ensure consistency, comprehension, and independence of the scoping review, 2 reviewers (ZLB and PK) independently screened the 347 publications and discussed the relevance of each potentially eligible source. The 2 reviewers evaluated titles and abstracts of sources according to the inclusion criteria as the initial screening method. The initial screening resulted in the exclusion of 302 records, due to their inability to meet the inclusion criteria with regard to study population, research location, or the context of the research in reference to diet, nutritional quality, or disease outcomes. Subsequently, 45 records remained and underwent secondary screening where the 2 reviewers independently assessed the full-text articles according to eligibility criteria. The secondary screening resulted in the exclusion of 27 records due to publication status, research context, research location that did not meet inclusion criteria, or the inability to retrieve the article. At the end of the source selection process, 16 records were identified as relevant and eligible to be used in synthesis. If at any point during the selection process the 2 reviewers disagreed on source selection, a third (GLL) and fourth (HV) reviewer was introduced to resolve the disagreement. Figure 1 depicts the pathway taken to derive the final list of eligible sources included, as well as reasons for exclusion.

FIGURE 1.

Selection of sources of evidence.

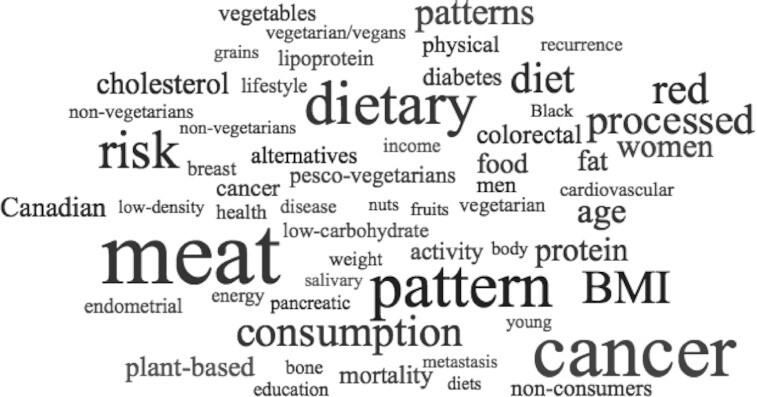

Thematic analysis was used to identify predominant themes and keywords from all eligible articles. A word cloud was created based on the most frequent terms appearing in the titles and result sections of the 16 eligible sources (Figure 2). Terms that did not add value to the image, such as conjunctions, prepositions, and collective nouns, were removed at the first author's discretion. The word cloud emphasizes the major themes of this scoping review by accentuating terms such as meat consumption, processed meat, dietary patterns, cancer, and BMI.

FIGURE 2.

Word cloud showing the most frequent words appearing in the titles and results of eligible articles. Word cloud was created using worditout.com.

Results

Characteristics of studies

The characteristics and methodological quality of the included studies are presented in Table 2. Of the eligible sources, there were 7 longitudinal studies, 5 case-control studies, 3 cross-sectional studies, and 1 randomized parallel study. The majority of studies focused on both genders, with the exception of 3 studies, which focused only on the male population. In addition, the majority of studies focused on an adult population, except for 1 study which focused on an adolescent population concerning health outcomes later in life. Dietary patterns were typically assessed by food-frequency questionnaires and specified plant- or animal-based food intakes and/or dietary patterns. The majority of trends of the eligible articles indicate a gap in research, such that research is not comprehensive or inclusive across all demographics of the population, not to mention the lack of studies focused on assessing cultural diversity within diet–disease relations.

TABLE 2.

Characteristics of eligible studies included in manuscript synthesis to define the role of plant-based diets in supporting the health and well-being of Canadians1

| Authors, year (reference) | Study design (sample size) | Target population | Study aim | Dietary pattern assessment | Study outcomes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Jenkins et al., 2014 (14) | Randomized parallel study, stratified by sex (n = 39) | Ontario overweight hyperlipidemic men and postmenopausal women | To determine the long-term effect of a plant-based diet low in carbohydrates on weight loss and LDL cholesterol | Test diet was a low-carbohydrate vegan diet containing 26% of calories from carbohydrates, 31% from vegetable proteins, and 43% from fats. Control diet was a high-carbohydrate lacto-ovo-vegetarian diet containing 58% of calories from carbohydrates, 6% from proteins, and 25% from fats | Statistically significant differences were found between the test and control groups. The LC-VD resulted in greater reductions in BMI, weight loss, LDL cholesterol, HDL cholesterol, total cholesterol, triglycerides, apoB, and apoB to apo-A1 ratio compared with the HC-LOD |

| Tharrey et al., 2018 (18) | Longitudinal study (n = 81,337) | Canadian/American Seventh-day Adventists aged >25 y who self-reported cardiovascular events | To evaluate the association between specific patterns of protein intake with cardiovascular mortality | Food-frequency questionnaire assessed diet for the previous year and allowed groupings for animal and plant proteins | Statistically significant associations were found for the highest consumption patterns of the meat/dairy protein group and the nut/seed protein group. The highest quintile consumption of the nut/seed protein group reduced CVD mortality risk. The highest quintile consumption of meat/dairy protein group increased CVD mortality risk |

| Movassagh et al., 2018 (22) | Longitudinal study (n = 251) | Saskatchewan population aged 8 to 15 y | To determine if a healthy dietary pattern (with an emphasis on long-term higher intakes of fruits and vegetables) would be beneficial from childhood to young adulthood bone health | 24-h Dietary recalls assessed dietary intake 2 to 4 times during adolescents and once in young adults and allowed for grouping into vegetarian, Western, high-fat/high-protein, and mixed dietary patterns | The practice of a vegetarian-style dietary pattern during adolescence is a positive independent predictor of improved bone health |

| Sharma et al., 2018 (17) | Longitudinal study (n = 532) | Newfoundland and Labrador population aged 20 to 75 y | To estimate the risk of mortality, reoccurrence, metastasis of colorectal cancer using different dietary and consumption patterns | 169-Item food-frequency questionnaire assessed diet from 7 to 11 years after cancer diagnosis | Statistically significant increased risk for colorectal cancer mortality, reoccurrence, and metastasis was associated with high intakes of meat and dairy compared with high intakes of fruits, vegetables, and whole grains |

| Catsburg et al., 2015 (12) | Longitudinal study (CSDLH cohort: cases = 1097, controls = 3320; NBSS cohort: cases = 3659, controls = 45,751) | CSDLH cohort: Canadian alumni from Universities of Alberta, Toronto, and Western; NBSS cohort: Canadian citizens | To perform 2 cohort studies to identify and confirm associations between dietary patterns and breast cancer risk | CSDLH cohort: 166-item food-frequency questionnaire assessed diet over a 1-y period (assessment at baseline and at the end of the study) as well as three 24-h dietary recalls provided throughout the study period, which allowed for grouping into healthy and meat/potatoes dietary patterns.NBSS cohort: 86-item food-frequency questionnaire assessed diet upon enrollment in the cohort and allowed for grouping into healthy and meat/potatoes dietary patterns | Statistically significant associations were found for the highest consumption patterns of the healthy dietary pattern and the meat/potatoes dietary pattern with breast cancer. The highest quintile consumption of the healthy pattern decreased disease risk and the highest consumption of the meat/potatoes pattern increased disease risk |

| Japas et al., 2014 (9) | Retrospective longitudinal study (n = 9864) | Canadian/American male Seventh-day Adventists aged 30 to 112 y | To estimate associations of weight gain in men based on lifestyle habits (diet, sedentary behavior, physical activity, sleep) | 130-Item food-frequency questionnaire assessed diet 1 y before the interview date and allowed for grouping into vegan, lacto-ovo-vegetarian, semi-vegetarian, and nonvegetarian | The odds of being nonvegetarian were higher among men with a BMI change greater than the median BMI change |

| Tonstad et al., 2013 (21) | Longitudinal study (n = 41,387) | Canadian/American maleSeventh-dayAdventists aged >30 y | To evaluate the relation of diet to incident diabetes among Black and non-Black participants | 130-Item food-frequency questionnaire assessed diet for the past year and allowed for grouping into vegan, lacto-ovo-vegetarian, pesco-vegetarian, semi-vegetarian, and nonvegetarian groups | The incidence rate of type 2 diabetes increased incrementally among vegans, semi-vegetarians, lacto-ovo-vegetarians, pesco-vegetarians, and nonvegetarians, such that the most restrictive vegetarian diet had a protective effect |

| Lonkhuijzen et al., 2011 (15) | Longitudinal study (n = 1937) | Canadian alumni from Universities of Alberta, Toronto, and Western (CSDLH cohort) | To examine the relation between risk of endometrial cancer and consumption of red meat and other meat products | 166-Item food-frequency questionnaire assessed diet over a 1-y period | No statistically significant associations were found between meat consumption and endometrial cancer risk |

| Pan et al., 2017 (8) | Case-control study (cases = 132, controls = 3076) | Canadian citizens aged 20 to 76 y | To evaluate the etiological role of environmental factors for salivary gland cancer | 69-Item food-frequency questionnaire assessed diet 2 y before the interview date | The only food item with a statistically significant association with salivary gland cancer was processed meat, which represented an increase in odds of disease with an increase in consumption |

| Chen et al., 2015 (13) | Case-control study (cases = 506, controls = 673) | Newfoundland and Labrador population aged 20 to 74 y | To assess if dietary patterns are associated with colorectal cancer risk in Newfoundland and Labrador | 169-Item food-frequency questionnaire assessed diet 1 to 2 y before diagnosis and allowed for grouping into meat and plant dietary patterns | Statistically significant associations were found for the highest consumption patterns of the meat and plant dietary patterns with colorectal cancers. The highest consumption of the plant pattern decreased the risk for colorectal cancer and rectum cancer. The highest consumption of the meat pattern increased the risk for colorectal cancer, distal colon cancer, and rectal cancer |

| Biel et al., 2011 (10) | Case-control study (cases = 549, controls = 1036) | Albertian women aged 30 to 79 y | To determine if a diet pattern mostly consisting of vegetables and fruits would meaningfully reduce the risk of endometrial cancer | 124-Item food-frequency questionnaire assessed diet 1 y before the interview date and allowed for grouping into plant and meat dietary patterns | Only the plant dietary pattern had a statistically significant association with endometrial cancer, which represented a decrease in odds of disease with the highest quintile consumption pattern. This trend remained true and significant when stratified based on BMI |

| Squires et al., 2010 (19) | Case-control study (cases = 518, controls = 686) | Newfoundland and Labrador population aged 20 to 74 y | To assess whether an association exists between intake of total red meat and pickled red meat and the risk of colorectal cancer | 169-Item food-frequency questionnaire assessed diet 1 y before diagnosis | A statistically significant increased odds for colorectal cancer was associated with the highest consumption pattern of pickled meat |

| Ghadirian and Nkondjock, 2010 (11) | Case-control study (cases = 179, controls = 239) | Greater Montreal population aged 35 to 79 y | To investigate if the consumption of specific food groups predicts the risk of pancreatic cancer | 200-Item food-frequency questionnaire assessed diet for 1 y and 10 y before cancer diagnosis | Statistically significant associations were found for the highest consumption of vegetables/vegetable products, and lamb/veal/game meats with pancreatic cancer, such that high vegetable consumption reduced disease risk and high meat consumption increased disease risk |

| Vatanparast et al., 2020 (24) | Cross-sectional survey (n = 32,005,286) | Canadian citizens aged >1 y of age (Canadian Community Health Survey, 2015) | To determine the percent contribution of red/processed meat and plant-based meat alternatives to daily energy intake and nutrient intake among respective consumers | Food-frequency questionnaire and 24-h dietary recalls assessed diet and allowed for grouping into meat and plant-based meat consumers | Simulating a population that doubles their plant-based meat alternatives and halves the consumption of red and processed meat resulted in improved nutritional adequacy. For example, the simulated diet had significant decreases in cholesterol, zinc, vitamin B-12, and protein with increases in dietary fiber, PUFAs, magnesium, and dietary folate |

| Ruan et al., 2019 (16) | Cross-sectional survey (n = 7503) | Canadian citizens | To estimate the current attributable and future avoidable burden of cancer related to both red and processed meat consumption in Canada | Dietary meat exposure was obtained from the Canadian Health Measures Survey and was assessed based on frequency and portion size | Red and processed meat consumption was attributable to cancer and cancer incidence would decrease if the Canadian population reduced their meat consumption |

| Fraser, 2015 (23) | Cross-sectional analysis (n = 592) | Canadian/American maleSeventh-dayAdventists aged >30 y | To compare cardiovascular risk factors between vegetarians and nonvegetarians in Black individuals | Food-frequency questionnaire assessed diet 2–3 y before clinic visit and 2–3 mo before clinic visit and allowed grouping into vegan/lacto-ovo-vegetarian, pesco-vegetarian, and nonvegetarian diet groups | Significantly reduced odds for hypertension, high total cholesterol, high LDL cholesterol, type 2 diabetes, and abdominal obesity among individuals practicing a vegan/lacto-ovo-vegetarian diet compared with those practicing a nonvegetarian diet |

Ordered based on study design. CSDLH, Canadian Study of Diet, Lifestyle, and Health; CVD, cardiovascular disease; HC-LOD, high-carbohydrate, lacto-ovo vegetarian diet; LC-VD, low-carbohydrate vegan diet; NBSS, National Breast Screening Study.

Prevalence of plant-based diets in Canada

In the Canadian population, both the prevalence and frequency of meat consumption are higher than that of plant-based meat alternatives (16, 24). Based on a self-reporting nationally representative 2015 Canadian cross-sectional survey, it was determined that 41.7% of Canadians consume meat products, whereas only 14.5% of Canadians consume plant-based meat alternatives (24). The consumption patterns among the Canadian population differ based on sociodemographic factors such as age and sex (16, 24). For example, 52.3% of Canadian females consume plant-based meat alternatives, whereas only 37.5% of Canadian men consume these products (24). Alternatively, of the Canadian population who do consume meat products, a national health survey determined the average person consumed red meat ∼3.2 times/wk and processed meat 1.2 times/wk (16). Canadian men, and more specifically men aged 18 to 39 y of age, are among the highest consumers of meat products (16, 24). On average, 56.5% of Canadian men consume meat products and consume them at a greater weekly frequency than the average Canadian (16, 24).

Nutritional quality of plant-based diets

Of the included sources, only one discussed overall diet quality and the specific nutrient contributions from animal products and plant-based meat alternatives (24). Vatanparast et al. (24) determined that plant-based meat alternatives contribute considerably (≥20%) to one's daily intake of dietary fiber, magnesium, MUFAs, PUFAs, and total fat, whereas red/processed meats contribute considerably (≥20%) to one's daily intake of protein, MUFAs, vitamin B-12, zinc, SFAs, and cholesterol (24). The most considerable differences (≥14%) among the nutrient contributions from plant-based meat alternatives and meat products were in daily intakes of protein, PUFAs, cholesterol, dietary fiber, vitamin B-12, and zinc (24). While both plant- and animal-based diets can be healthy, high consumption of fat, SFAs, and cholesterol, typical of an omnivore diet, has negative health implications (24).

To assess the potential nutritional impact of consuming increased plant-based meat alternatives in place of red/processed meats, Vatanparast et al. (24) transformed Canadian consumption averages to simulate a diet with improved daily nutritional intakes. The simulated diet was derived by doubling the intake of plant-based proteins, such as legumes, nuts, and seeds, and reducing the intake of red meat proteins such as beef, pork, veal, lamb, processed meats, and game by half (24). In comparison to the average Canadian diet, the simulated diet yielded significant increases in dietary fiber, PUFAs, magnesium, and folate, as well as significant decreases in protein, cholesterol, zinc, and vitamin B-12 (24). Furthermore, the simulated diet resulted in an overall significant improvement in the Nutrient Rich Food (NRF) index score, an index representing nutrient density based on nutrients to encourage (i.e., fiber, protein, calcium, vitamin D, iron, magnesium, potassium, vitamin A, and vitamin C) and nutrients to limit (i.e., SFAs, sugar, and sodium) (24). Consequently, Vatanparast et al. (24) determined that a diet with higher intakes of plant-based alternatives and decreased intakes of animal products provides a significant benefit to the nutrient density of one's diet and their nutrient intakes, such as increasing intakes of dietary fiber, magnesium, folate, and PUFAs as well as decreasing intakes of cholesterol, SFAs, and sodium.

Diet and obesity

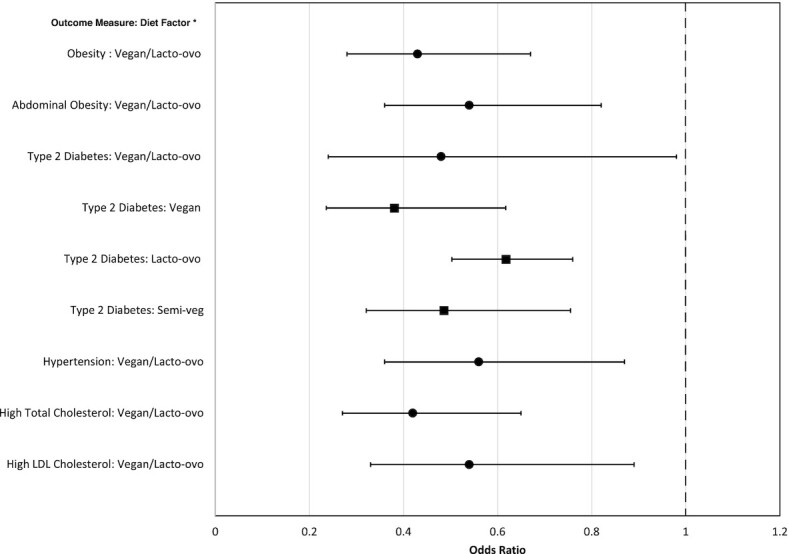

Multiple sources supported the association between plant-based diets and reduced prevalence of obesity or improvements in weight-loss endeavors (9, 14, 20). A cross-sectional study completed with Black members of the Seventh-day Adventist church, residing in both Canada and the United States, discovered an association between vegetarian-style diets and a lower risk of obesity (20). Figure 3 depicts the ORs for obesity and abdominal obesity among Black members of the church. Black female members of the church who followed either a vegan or lacto-ovo-vegetarian diet were found to have significantly reduced odds of developing obesity and abdominal obesity, as well as a significantly lower mean BMI and mean waist circumference compared with their nonvegetarian counterparts (20). Similar patterns were also found among the male Black members of the church with regard to mean BMI and mean waist circumference (20). A second study in only male members of the Seventh-day Adventist church retrospectively followed participants to determine their relationship between dietary patterns and weight gain over 20 y (9). Japas et al. (9) determined that male members who practiced a vegetarian-style diet were significantly less likely to have experienced weight gain over the 20 y.

FIGURE 3.

Forest plot outlining the practice of various plant-based dietary patterns in comparison to omnivore dietary patterns and the odds of chronic conditions and health indicators. Black circles represent the Black population of the Seventh-day Adventist Church (20). Black squares represent the population of the Seventh-day Adventist Church (21). *Diet factor represents the specific plant-based diet tested in comparison with a nonvegetarian diet. Lacto-ovo, lacto-ovo-vegetarian dietary pattern; Semi-veg, semi-vegetarian dietary pattern.

A third study related to obesity outcomes was a randomized parallel study completed in a group of overweight individuals in Ontario who followed either a low-carbohydrate vegan diet (LC-VD) or a high-carbohydrate lacto-ovo-vegetarian diet (HC-LOD) and were encouraged to restrict their daily caloric intake to 60% of their required caloric consumption to support weight loss, although both diets allowed ad libitum consumption (14). The LC-VD was a diet with 26% of calories sourced from carbohydrates, 31% from plant-based proteins, and 43% from fats while restricting the consumption of all animal products (14). The HC-LOD was a diet with 58% of calories sourced from carbohydrates, 16% from plant-based proteins, dairy, or eggs, and 25% from fats while restricting their diet to a lacto-ovo-vegetarian dietary pattern (14). At the end of the 6-mo study period, participants following the LC-VD had a higher mean weight loss and a greater BMI reduction compared with participants following the HC-LOD (14). No significant differences were found between the 2 diet types in terms of body fat, waist circumference, satiety, glycated hemoglobin concentrations, fasting blood glucose, insulin, or blood pressure outcomes (14). Since the diets differed by both carbohydrate intake and style of vegetarian diet, it is difficult to draw conclusions as to the effect of plant-based diets on obesity outcomes (14).

Diet and type 2 diabetes

Of the eligible sources, 2 articles reported on the practice of vegetarian-style diets and the outcome of type 2 diabetes (T2D) among members of the Seventh-day Adventist church. Among this population, the incidence rate of T2D increased incrementally among vegans, semi-vegetarians, lacto-ovo-vegetarians, pesco-vegetarians, and nonvegetarians as indicated in Figure 3 (21). This trend indicates that the most restrictive vegetarian-style diet, a vegan diet, provides the greatest benefit to reduce the risk of T2D (21). This trend remained true and statistically significant, with the exception of the relation between T2D and a pesco-vegetarian diet, where Tonstad et al. (21) adjusted for confounding factors such as age, BMI, gender, ethnicity, income, and education. For example, when the model was adjusted for all of the confounding factors, the odds of developing T2D were reduced by 61.9% among vegan members, 51.4% among semi-vegetarian members, and 38.2% among lacto-ovo-vegetarian members in comparison to nonvegetarian members, as indicated in Figure 3 (21). Of the members practicing a vegan diet versus a nonvegetarian diet, Black members had greater reductions in odds of developing T2D compared with non-Black members (20, 21). Furthermore, Fraser et al. (20) determined that Black members not taking antidiabetic medication and practicing a vegan or lacto-ovo-vegetarian diet had an average significant reduction in fasting blood glucose of 7.3 mg/dL compared with their nonvegetarian counterparts. These trends emphasize the beneficial role of strict vegetarian diets in the incidence of T2D by highlighting the increased influence of a plant-based diet among higher-risk populations (20, 21).

Diet and cardiovascular diseases

Two of the 3 eligible sources on cardiovascular disease (CVD) outcomes again focused on the population of Seventh-day Adventist church members. The role of diet and exposure to animal products was determined to have a substantial effect on CVD outcome measures, as well as on CVD mortality (18, 20). For example, Black members of the church who practiced vegetarian-style diets had a significantly reduced risk of high total cholesterol, high LDL cholesterol, and hypertension compared with their nonvegetarian counterparts (20). Furthermore, the beneficial role of vegetarian-style diets is further emphasized by the finding that vegan or lacto-ovo-vegetarian Black members not taking cholesterol-lowering medication had a lower average adjusted fasting total cholesterol and mean LDL-cholesterol concentrations compared with their nonvegetarian counterparts, as indicated in Figure 3 (20). With regard to CVD mortality, plant-based diets remain superior compared with omnivore dietary patterns (18). With adjustments made for numerous lifestyle confounders, members who placed in the highest quintile of protein consumption from meat had a 61% increased risk of CVD mortality compared with members in the lowest quintile (18). Alternatively, members who placed in the highest quintile of protein consumption from nuts/seeds had a 40% decreased risk of CVD mortality compared with members in the lowest quintile (18).

The final eligible source concerning CVD outcomes was the randomized parallel study completed by Jenkins et al. (14), described above, which tested the effect of practicing an LC-VD on body weight and cardiovascular risk factors. Participants following the LC-VD experienced numerous improvements in CVD risk factor measures, including significant reductions in total cholesterol, LDL cholesterol, HDL cholesterol, triglycerides, apoB, and the apoB to apoA1 ratio, compared with those following the HC-LOD (14). Furthermore, the LC-VD also resulted in a 2% reduction in calculated 10-y ischemic heart disease risk relative to the HC-LOD (14). However, since the study diets differed in both carbohydrate intake and style of vegetarian diet, it is difficult to draw conclusions as to the singular effect of plant-based diets on CVD outcomes (14).

Diet and osteoporosis

Only one of the eligible sources discussed osteoporosis and bone health in reference to dietary patterns (22). The study identified 4 dietary patterns, which included the “vegetarian style dietary pattern,” defined by a diet rich in dark-green vegetables, eggs, nonrefined grains, 100% fruit juice, legumes, nuts, seeds, added fats, fruits, and low-fat milk/milk alternatives (22). The practice of the “vegetarian style dietary pattern” during adolescence was found to have a substantial benefit in relation to multiple measures of bone health in adulthood such as bone mineral content (BMC) and bone mineral density (BMD) (22). When controlling for potential covariates, the practice of a “vegetarian style dietary pattern” in adolescence was a positive independent predictor for total body BMC and total body areal BMD in young adulthood (22). Furthermore, in comparison to the lowest quartile of the “vegetarian style dietary pattern,” young adults in the highest quartile had an 8.5% higher total body BMC, 6% higher total body areal BMD, 10.6% higher femoral neck BMC, and 9% higher femoral neck areal BMD (22). Therefore, the practice of a plant-based diet from a young age and throughout the life course provides benefits to bone health later in life (22).

Diet and cancer

Current evidence indicates the burden of cancer in Canada is partially attributable to poor dietary patterns, specifically the consumption of both red and processed meats (8, 11–13, 16, 17, 19). In Canada, red meat consumption is linked to ∼5.9% of all associated cancers (pancreas, stomach, colorectal) and 5.3% of all probable cancers (16). More specifically, in 2015, red meat consumption was estimated to contribute to 12.8% of male pancreatic cancer cases, 5.4% of stomach cancer cases, and 5.3% of colorectal cancer cases (16). Similar trends emerge with processed meat consumption, as it is estimated to contribute to 4.5% of all associated cancers (esophagus, pancreas, colorectal, stomach) and 4.3% of all probable cancers in Canada (16). Evidently, a reduction in the consumption of both red and processed meats and movement towards plant-based eating would result in a reduced burden of cancer (16). For example, based on statistical estimates and various assumptions, Ruan et al. (16) determined that a nationwide reduction of 0.5 servings of processed meat/wk (37.5 g/wk) could result in a proportional reduction of 3.1% of esophageal squamous cell carcinomas, 2.0% of pancreatic cancer, 1.8% of colorectal cancer, and 1.8% of stomach cancer by 2042.

Endometrial cancer

Of the eligible sources, 2 articles analyzed the relation between endometrial cancer risk and dietary patterns. Both beneficial and detrimental relations were found between plant-based diets and omnivore diets, respectively; however, only the relation with plant-based diets was statistically significant (10, 15). For instance, both Biel et al. (10) and Lonkhuijzen et al. (15) found increased odds for endometrial cancer in the highest meat consumption patterns of omnivore diets compared with the lowest consumption pattern, although not all relations were statistically significant. Lonkhuijzen et al. (15) discovered that red meat consumption >52.15 g/d and overall meat consumption >132.89 g/d resulted in a significantly increased risk of endometrial cancer. With regard to plant-based diets, Biel et al. (10) found a significant relation between a “plant dietary pattern,” defined as a diet with higher intakes of dietary fiber, vitamin A, vitamin C, carotene, B-carotene, and folate and with lower intakes of total fats, SFAs, MUFAs, total trans fats, and cholesterol, and endometrial cancer risk. Individuals who placed in the highest consumption of the “plant dietary pattern” quintile were found to have a 30% reduced risk for endometrial cancer compared with those in the lowest consumption quintile (10). The beneficial effects of a plant-based diet appear to extend to the overweight or obese population, as overweight or obese individuals in the highest consumption of the “plant dietary pattern” quintile had a 33% reduced risk for endometrial cancer compared with those in the lowest quintile with a normal BMI classification (10).

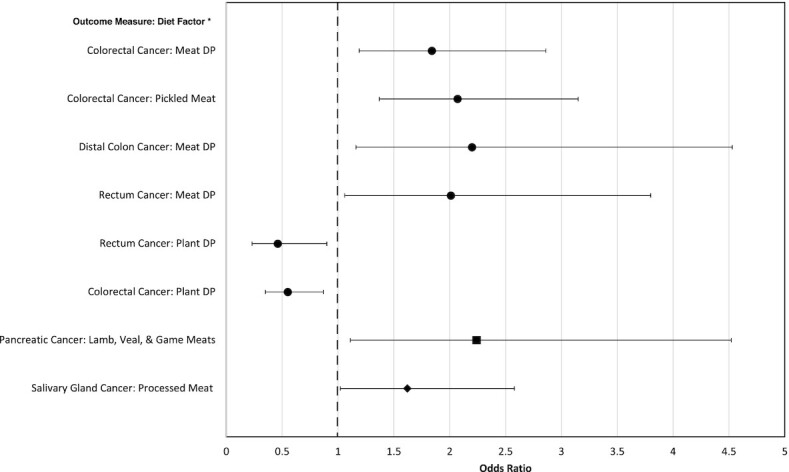

Colorectal cancer

Of the included sources, 3 articles analyzed the relation between colorectal cancer and dietary patterns. All 3 studies were completed in a population in Newfoundland and Labrador; however, diet was assessed differently. The first case-control study completed by Chen et al. (13) assessed various dietary patterns and found significant relations between both a plant dietary pattern and a meat dietary pattern and risk of colorectal cancer. Chen et al. (13) determined that individuals in the highest meat consumption group of a “meat dietary pattern” had a significantly increased risk for colorectal cancer compared with the lowest meat consumption group, as indicated in Figure 4. In contrast, individuals consuming the highest amounts of plant-based foods congruent with the “plant dietary pattern” had a significantly reduced risk for colorectal cancer compared with the lowest quintile, as indicated in Figure 4 (13). Chen et al. (13) also determined that these dietary patterns remain indicative of the specific types of colon cancer, such that the highest meat consumption increased risk for both distal colon cancer and rectum cancer and the highest plant consumption reduced risk for rectum cancer, as indicated in Figure 4. Sharma et al. (17) also found similar results; individuals who consumed diets characterized by high intakes of animal products had a significantly increased risk for colorectal cancer mortality, reoccurrence, and metastasis compared with individuals with diets characterized by high intakes of fruits, vegetables, and whole grains. However, when Squires et al. (19) specifically assessed the individual intake of red meat or vegetables, there were no statistically significant associations between the food items and colorectal cancer. Squires et al. postulated the nonsignificant result to be due to a variety of factors, including interactions between genetic and environmental factors of colorectal cancer and dietary patterns as well as how study parameters were defined such as the umbrella term of “red meat” and how the red meat consumption frequency patterns of the Newfoundland population differ from other Canadian provinces. Nonetheless, Squires et al. (19) discovered a statistically significant relation between pickled meat consumption and colorectal cancer, such that the highest pickled meat consumption more than doubled the odds for colorectal cancer compared with the lowest consumption. However, Squires et al. noted the potential for bias in the relation due to the differing daily nutrient intakes of saturated fat, folic acid, and total kilocalories between cases and controls, which may have influenced the nutritional quality of each respective diet. Overall, scientific evidence demonstrates that higher consumption of animal products results in an increased risk for colorectal cancers compared with higher consumption of plant-based foods (13, 17, 19).

FIGURE 4.

Forest plot outlining the highest consumption patterns of plant- or animal-based foods in comparison to the lowest consumption pattern of indicated plant- or animal-based foods and the odds of select cancers. Black circles represent the Newfoundland population (13, 19). The black square represents the Greater Montreal area population (11). The black diamond represents the Canadian population (8). *Diet factor represents the highest consumption pattern of the indicated plant- or animal-based food in comparison to the lowest consumption pattern of the indicated plant- or animal-based food. Meat DP, meat dietary pattern represented by high consumption of red meat, cured/processed red meat, fish, and processed fish; Plant DP, plant dietary pattern represented by high consumption of root vegetables, tomato sauce, total cereals and grains, berries, dried fruits, and other fruits, other green vegetables, and other vegetables.

Pancreatic cancer

One article, by Ghadirian and Nkondjock (11), assessed plant and animal consumption patterns on the odds of pancreatic cancer via a case-control study in the Greater Montreal area. It was determined that only the highest consumption of lamb, veal, and game meats significantly increased the odds for pancreatic cancer in comparison to the lowest consumption, as indicated in Figure 4. The remaining plant and animal consumption patterns showed similar trends of increased pancreatic cancer odds for various types of animal products and decreased odds for plant-based foods; however, the associations were not significant (11).

Breast cancer

One article, by Catsburg et al. (12), assessed a “meat and potatoes” (large intakes of red meat and potatoes) dietary pattern and a “healthy” (large intakes of vegetables and legumes) dietary pattern in both the Canadian Study of Diet, Lifestyle, and Health (CSDLH) cohort and the National Breast Screening Study (NBSS) cohort for the risk of breast cancer. It was determined that the highest quintile of the “healthy” dietary pattern reduced the risk of breast cancer compared with those in the lowest consumption quintile; however, this association was only statistically significant in the CSDLH cohort (12). Similarly, the highest quintile of the “meat and potatoes” dietary pattern showed a trend for increased breast cancer risk compared with those in the lowest consumption quintile; however, this association was not statistically significant in either cohort (12).

Salivary gland cancer

One article, by Pan et al. (8), assessed consumption patterns of food items such as dairy, various types of vegetables, fruits, grains, meats, and plant-based protein alternatives, as well as weekly nutrient intakes of carbohydrates, fiber, and various types of fats on the risk of salivary gland cancer via a national case-control study. Of all the food items, only consumption of processed meat resulted in a significant relation, where the consumption of >4 servings/wk increased the odds of salivary gland cancer compared with those consuming <1.4 servings/wk, as indicated in Figure 4 (8).

Discussion

In this study, current evidence on the association between plant- or animal-based dietary patterns and chronic conditions was reviewed from 16 longitudinal, case-control, cross-sectional, and randomized parallel studies. Substantial evidence was found to support an association between the practice of plant-based dietary patterns and improved health and well-being of Canadians as seen through reduced odds of chronic conditions (1, 2, 9, 12, 14, 18, 20–23). Various gaps in knowledge and research were also found, such that future research should focus on quantifying the relation between plant-based diets and chronic conditions over the life course while considering different demographic and cultural factors.

Summary of evidence

Quality of plant-based diets

The differential nutrient intake from plant-based diets and omnivore diets yields distinctive nutritional and health outcomes (1, 2, 8–24, 28, 30). As indicated in the articles reviewed, the nutritional and health superiority of plant-based diets has been confirmed by various observational and experimental studies (8–22, 24). However, consumers following a plant-based diet must adequately plan to ensure sufficient intakes of vitamin B-12, iron, vitamin D, calcium, zinc, and dietary fats (6, 7, 24, 28). Nevertheless, plant-based diets contribute considerably to daily intakes of MUFAs, PUFAs, total fats, magnesium, and dietary fiber, which leads to improved nutritional quality and health outcomes (6, 7, 24, 28). As indicated in the modeling study by Vatanparast et al. (24), an increase in plant-based meat alternatives paired with a decrease in animal products can result in improved intakes of required nutrients and a better overall diet as indicated by an improved NRF index score. To conclude, the nutritional and health benefits of a well-planned, plant-based diet are substantial, such as fewer chronic disease risk factors and lower incidence of chronic conditions in those practicing a plant-based diet (1, 2, 5, 6, 8–22, 24).

Diet–disease relation

There is substantial evidence from observational and experimental studies supporting the practice of a well-planned plant-based diet to improve cholesterol concentrations, glycemic control, blood pressure, and weight management and to reduce the incidence of CVD, T2D, and obesity (1, 2, 7, 9, 12, 14, 18, 20–23). This relation between plant-based diets and T2D, obesity, and cardiovascular health has been well established; however, many Canadians still choose not to adapt to a more plant-based lifestyle due to perceived social hindrances, the feasibility of preparing plant-based meals, and their enjoyment of meat products (1–4, 9, 12, 14, 16, 18, 20–24).

In contrast, the relation between osteoporosis and plant-based diets is much less understood (1, 22). Although the study reviewed found an independent positive correlation between the practice of a “vegetarian-style diet” and bone health outcomes (22), there is no consensus among the scientific community. In a scoping review completed by Craig (7), it was determined that there was no significant difference in BMD between omnivores and lacto-ovo-vegetarians, although it should be noted that the lacto-ovo-vegetarian diet pattern is not among the most restrictive plant-based diets, and typically bone health concerns emerge with regard to vegan dietary patterns. Further research is needed to determine the effect of the diverse patterns of plant-based diets and their effect on bone health and osteoporosis risk.

The relation between cancer and plant-based diets has long been studied and varies drastically depending on the type of cancer under study. There are many elements of a plant-based diet that contribute to the reduced risk of select cancers, such as endometrial cancer or breast cancer (10, 12). For example, a well-planned plant-based diet can contribute high intakes of vitamins, minerals, and phytochemicals, which can provide antioxidant and anti-inflammatory regulatory properties benefiting many health outcomes (6). However, the majority of scientific evidence is in support of the adverse associations between animal products, specifically red and processed meats, and cancer (1, 2, 8, 10–13, 15–17, 19, 23, 30). Several possible mechanisms explain the association between increased cancer risk and animal product consumption, such as the high saturated fat and cholesterol intake typical of an omnivore diet, as well as the potential to produce carcinogens, notably heterocyclic amines or polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons, during the meat cooking process (16, 24, 30). The negative relation between animal products and cancer is supported by significant scientific evidence, leading the WHO to classify processed meats as a group 1 carcinogen and red meats as a group 2A carcinogen (1). This equates to the known and scientifically supported conclusion that processed meats are known to cause select cancers and red meats probably cause select cancers (1). Further research should be completed to assess the theoretical beneficial effects of a plant-based diet and cancer outcomes, while also considering potential confounders.

Motivators and limitations to the practice of plant-based diets in Canada

Regardless of the vast amount of evidence in support of the nutritional adequacy and health benefits of plant-based diets, the public perception of plant-based diets creates challenges to widespread implementation. A 2017 cross-sectional Canadian survey found that 41.0% of Canadians believed they would not enjoy the taste of plant-based protein alternatives; 38.3% believed they are too expensive in comparison to animal products; 37.6% believed they are “too processed”; 36.3% were worried about high sodium levels (3). Lacroix and Gifford (4) found that the most impactful hindrances to reducing animal product consumption were social conformity or low support for plant-based diets, lack of knowledge and/or time to prepare meat-free meals, the need for animal products to maintain an adequate “healthy” diet, and attachment to animal products due to taste, dependence, and entitlement. Alternatively, some Canadians respond to motivators to reduce their animal product consumption, such as improved health, ethical responsibility, environmental sustainability, and financial benefit (4). However, men and women appear to differ in how they perceive, and in their willingness to adopt, plant-based diets (16, 24). More Canadians consume animal-based foods than plant-based foods, and this consumption pattern is exaggerated among the male population (16, 24). In contrast, a higher proportion of the Canadian female population consume a plant-based diet (16, 24), and women are more willing to reduce animal product consumption in comparison to their male counterparts (3, 4). Dietary patterns appear to be an expression of perceptions, as Canadians following an omnivore diet perceive a disproportionate number of limitations, restricting their transition to a plant-based diet (3, 4). With the increasing evidence that plant-based diets support optimal health and well-being, the dissemination of accurate information to Canadians is an important step in supporting the widespread transition to a more plant-based diet.

Knowledge gap and research recommendations

Dietary guidelines and policies should be regularly reviewed to incorporate new scientific evidence in support of plant-based nutrition. The 2019 Canadian Food Guide supports the increased intake of plant-based foods and restricts the intake of animal-based foods (2); however, rapidly expanding scientific research should guide future evaluation and revisions. Nutritional epidemiology research and evidence remain incomplete, imperfect, and continually evolving; therefore, Canadian dietary recommendations need to be regularly updated to support optimal health and well-being.

Table 3 outlines future research recommendations while noting areas with substantial consensus. For instance, it is evident that plant-based diets are nutritionally adequate and will support the health and well-being of those who practice them, but valid Canadian metrics and quantitative assessments regarding potential long-term health impacts are lacking. Research should also focus on the long-term potential of plant-based diets to address planetary health and food security. Furthermore, effective means of knowledge translation and dissemination should be further studied to ensure that the general public is informed of the nutritional and health benefits of a plant-based diet. Nutritional knowledge translation research should also focus on how to address the motivators and limitations to the adoption of a plant-based diet to help support the transition to plant-based nutrition. Addressing these knowledge gaps will enhance the capacity of our public health system to support Canadians to achieve optimal health and well-being in alignment with the the UN SDGs. Moreover, systematic change will likely not occur from a single publication, policy, or recommendation; comprehensive, well-rounded policies and recommendations that are frequently repeated, socially popular, and touch many Canadians are needed to support the transition to a plant-focused diet and improve Canadian health outcomes.

TABLE 3.

Research recommendations outlining known information and knowledge gaps in defining the role of plant-based diets in supporting the health and well-being of Canadians

| Established knowledge | Knowledge gaps |

|---|---|

| Well-planned plant-based diets are nutritionally adequate and support improved health and well-being | How does the practice of a plant-based diet affect health long-term? Population-based longitudinal studies with quantitative assessment are needed to evaluate diet over a long period of time |

| Plant-based diets support a planetary health approach to health and well-being | Can the practice of plant-based diets address the global need to improve the health of humans, animals, and the environment? |

| Can the increased practice of plant-based diets address issues related to food security in Canada and internationally? | |

| Poor diet is a risk factor for many chronic conditions | Do dietary factors overpower other genetic and social risk factors for various chronic conditions? |

| There are many motivators and limitations for Canadians to adopt a plant-based diet | How can we address the limitations to the adoption of plant-based or plant-focused diets for the Canadian population? |

| Can we further enhance the motivators, such as ethical, environmental, social, and health factors, for adopting a plant-based diet in Canada? | |

| The Canadian Food Guide supports diets focused on plant-based foods | What other mediums or forms of communication can be used to inform and translate nutritional knowledge to the Canadian population? |

Strengths and limitations

This scoping review followed a systematic process using relevant and appropriate search terms and eligibility criteria to discover and evaluate the literature. A major strength of this scoping review was the systematic methodology behind the discovery and assessment of the eligible literature. Qualitative thematic analysis was used to identify predominant themes and keywords, which helped substantiate and guide the research process. Irrespective of the strengths, the limitations of this scoping review should be acknowledged. First, due to the strict eligibility criteria, 4 of the 16 selected sources reported on the Seventh-day Adventist population, which may not adequately represent the Canadian population. The Seventh-day Adventist population has core values reflective of optimal health and wellness and this may have resulted in the influence of confounding variables, such as physical activity or socioeconomic status. Second, due to the unregulated definition of a plant-based diet, there was variation in how authors of the reviewed sources defined a “plant-based diet” or “vegetarian diet,” which resulted in some interpretation to synthesize results into a comprehensive review.

Conclusions

Based on the information extracted from the studies reviewed, the beneficial relation between plant-based diets, nutritional health, and chronic conditions is unequivocal (1, 2, 6, 8–24, 28). Furthermore, the nutritional quality of well-planned plant-based diets is superior to that of diets centered around animal products. Plant-based diets produce a synergistic effect between the myriad combinations of beneficial macronutrients, micronutrients, phytochemicals, and dietary components supporting nutritional adequacy, which, in turn, supports optimal health and wellness. The scientific evidence reviewed highlights significant nutritional health benefits of plant-based diets and their role in curbing the burden of chronic conditions.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The authors’ responsibilities were as follows—ZLB: was the primary reviewer and author for this manuscript; PK: was the secondary reviewer and author for this manuscript; GLL and HV: were third and fourth reviewers and authors; and all authors: read and approved the final manuscript.

Notes

The authors reported no funding received for this study.

Author disclosures: The authors report no conflicts of interest.

Supplemental Appendix A is available from the “Supplementary data” link in the online posting of the article and from the same link in the online table of contents at https://academic.oup.com/advances.

Abbreviations used: CSDLH, Canadian Study of Diet, Lifestyle, and Health; CVD, cardiovascular disease; BMC, bone mineral content; BMD, bone mineral density; GHG, greenhouse gas; HC-LOD, high carbohydrate lacto-ovo vegetarian diet; LC-VD, low-carbohydrate vegan diet; NRF, Nutrient Rich Food; PRISMA-ScR, Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analysis extension for Scoping Reviews; SDG, Sustainable Development Goal; T2D, type 2 diabetes.

Contributor Information

Zoe L Bye, School of Public Health, University of Saskatchewan, Saskatoon, Canada.

Pardis Keshavarz, College of Pharmacy and Nutrition, University of Saskatchewan, Saskatoon, Canada.

Ginny L Lane, School of Public Health, University of Saskatchewan, Saskatoon, Canada.

Hassan Vatanparast, School of Public Health, University of Saskatchewan, Saskatoon, Canada; College of Pharmacy and Nutrition, University of Saskatchewan, Saskatoon, Canada.

References

- 1. Willett W, Rockström J, Loken B, Springmann M, Lang T, Vermeulen S, Garnett T, Tilman D, DeClerck F, Wood A. Food in the Anthropocene: the EAT–Lancet Commission on healthy diets from sustainable food systems. Lancet North Am Ed. 2019;393(10170):447–92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Health Canada . Canada's dietary guidelines. Ottawa (Canada): Ministry of Health; 2019. [Google Scholar]

- 3. Clark LF, Bogdan AM. Plant-based foods in Canada: information, trust and closing the commercialization gap. Br Food J. 2019;121(10):2535–50. [Google Scholar]

- 4. Lacroix K, Gifford R. Reducing meat consumption: identifying group-specific inhibitors using latent profile analysis. Appetite. 2019;138:233–41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Nelson ME, Hamm MW, Hu FB, Abrams SA, Griffin TS. Alignment of healthy dietary patterns and environmental sustainability: a systematic review. Adv Nutr. 2016;7(6):1005–25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Hever J, Cronise RJ. Plant-based nutrition for healthcare professionals: implementing diet as a primary modality in the prevention and treatment of chronic disease. J Geriatr Cardiol. 2017;14(5):355–68. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Craig WJ. Nutrition concerns and health effects of vegetarian diets. Nutr Clin Pract. 2010;25(6):613–20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Pan SY, de Groh M, Morrison H. A case-control study of risk factors for salivary gland cancer in Canada. J Cancer Epidemiol. 2017;2017:4909214. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Japas C, Knutsen S, Dehom S, Dos Santos H, Tonstad S. Body mass index gain between ages 20 and 40 years and lifestyle characteristics of men at ages 40–60 years: the Adventist Health Study-2. Obesity Res Clin Pract. 2014;8(6):e549–57. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Biel RK, Friedenreich CM, Csizmadi I, Robson PJ, McLaren L, Faris P, Courneya KS, Magliocco AM, Cook LS. Case-control study of dietary patterns and endometrial cancer risk. Nutr Cancer. 2011;63(5):673–86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Ghadirian P, Nkondjock A. Consumption of food groups and the risk of pancreatic cancer: a case-control study. J Gastrointest Cancer. 2010;41(2):121–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Catsburg C, Kim RS, Kirsh VA, Soskolne CL, Kreiger N, Rohan TE. Dietary patterns and breast cancer risk: a study in 2 cohorts. Am J Clin Nutr. 2015;101(4):817–23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Chen Z, Wang PP, Woodrow J, Zhu Y, Roebothan B, McLaughlin JR, Parfrey PS. Dietary patterns and colorectal cancer: results from a Canadian population-based study. Nutr J. 2015;14:1–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Jenkins DJA, Wong JMW, Kendall CWC, Esfahani A, Ng VWY, Leong TCK, Faulkner DA, Vidgen E, Paul G, Mukherjea Ret al. Effect of a 6-month vegan low-carbohydrate (‘Eco-Atkins’) diet on cardiovascular risk factors and body weight in hyperlipidaemic adults: a randomized controlled trial. BMJ Open. 2014;4(2):e003505. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Lonkhuijzen LV, Kirsh VA, Kreiger N, Rohan TE. Endometrial cancer and meat consumption: a case-cohort study. Eur J Cancer Prev. 2011;20(4):334–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Ruan YB, Poirier AE, Hebert LA, Grevers X, Walter SD, Villeneuve PJ, Brenner DR, Friedenreich CM. Estimates of the current and future burden of cancer attributable to red and processed meat consumption in Canada. Prev Med. 2019;122:31–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Sharma I, Roebothan B, Zhu Y, Woodrow J, Parfrey PS, McLaughlin JR, Wang PP. Hypothesis and data-driven dietary patterns and colorectal cancer survival: findings from Newfoundland and Labrador Colorectal Cancer cohort. Nutr J. 2018;17(1):55. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Tharrey M, Mariotti F, Mashchak A, Barbillon P, Delattre M, Fraser GE. Patterns of plant and animal protein intake are strongly associated with cardiovascular mortality: the Adventist Health Study-2 cohort. Int J Epidemiol. 2018;47(5):1603–12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Squires J, Roebothan B, Buehler S, Sun Z, Cotterchio M, Younghusband B, Dicks E, Mclaughlin JR, Parfrey PS, Want PP. Pickled meat consumption and colorectal cancer (CRC): a case-control study in Newfoundland and Labrador, Canada. Cancer Causes Control. 2010;21(9):1513–21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Fraser G, Katuli S, Anousheh R, Knutsen S, Herring P, Fan J. Vegetarian diets and cardiovascular risk factors in black members of the Adventist Health Study-2. Public Health Nutr. 2015;18(3):537–45. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Tonstad S, Stewart K, Oda K, Batech M, Herring RP, Fraser GE. Vegetarian diets and incidence of diabetes in the Adventist Health Study-2. Nutr Metab Cardiovasc Dis. 2013;23(4):292–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Movassagh EZ, Baxter-Jones ADG, Kontulainen S, Whiting S, Szafron M, Vatanparast H. Vegetarian-style dietary pattern during adolescence has long-term positive impact on bone from adolescence to young adulthood: a longitudinal study. Nutr J. 2018;17(1):36. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Fraser GE. Vegetarian diets: what do we know of their effects on common chronic diseases?. Am J Clin Nutr. 2009;89(5):1607S–12S. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Vatanparast H, Islam N, Shafiee M, Ramdath DD. Increasing plant-based meat alternatives and decreasing red and processed meat in the diet differentially affect the diet quality and nutrient intakes of Canadians. Nutrients. 2020;12(7):2034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. United Nations . Sustainable Development Goals. New York: Department of Economic and Social Affairs; 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 26. Branchard B, Deb-Rinker P, Dubois A, Lapointe P, O'Donnell S, Pelletier L, Williams G. At-a-glance—how healthy are Canadians? A brief update. Health Promot Chronic Dis Prev Can. 2018;38(10):385–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Statistics Canada . Canadian Community Health Survey. Ottawa (Canada): Statistics Canada; 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 28. Camilleri GM, Verger EO, Huneau JF, Carpentier F, Dubuisson C, Mariotti F. Plant and animal protein intakes are differently associated with nutrient adequacy of the diet of French adults. J Nutr. 2013;143(9):1466–73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Tricco AC, Lillie E, Zarin W, O'Brien KK, Colquhoun H, Levac D, Moher D, Peters MDJ, Horsley T, Weeks L. PRISMA extension for scoping reviews (PRISMA-ScR): checklist and explanation. Ann Intern Med. 2018;169(7):467–73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Ferguson LR. Meat and cancer. Meat Sci. 2010;84:308–13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.