Abstract

The coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic and associated economic crisis have placed millions of US households at risk of eviction. Evictions may accelerate COVID-19 transmission by decreasing individuals’ ability to socially distance. We leveraged variation in the expiration of eviction moratoriums in US states to test for associations between evictions and COVID-19 incidence and mortality. The study included 44 US states that instituted eviction moratoriums, followed from March 13 to September 3, 2020. We modeled associations using a difference-in-difference approach with an event-study specification. Negative binomial regression models of cases and deaths included fixed effects for state and week and controlled for time-varying indicators of testing, stay-at-home orders, school closures, and mask mandates. COVID-19 incidence and mortality increased steadily in states after eviction moratoriums expired, and expiration was associated with a doubling of COVID-19 incidence (incidence rate ratio = 2.1; 95% confidence interval (CI): 1.1, 3.9) and a 5-fold increase in COVID-19 mortality (mortality rate ratio = 5.4; CI: 3.1, 9.3) 16 weeks after moratoriums lapsed. These results imply an estimated 433,700 excess cases (CI: 365,200, 502,200) and 10,700 excess deaths (CI: 8,900, 12,500) nationally by September 3, 2020. The expiration of eviction moratoriums was associated with increased COVID-19 incidence and mortality, supporting the public-health rationale for eviction prevention to limit COVID-19 cases and deaths.

Keywords: COVID-19, eviction, housing, social policy

Abbreviations:

- CDC

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention

- CI

confidence interval

- COVID-19

coronavirus disease 2019

The coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic and associated mass job and wage losses increased severe economic hardship for millions of US renter households, placing them at heightened risk of eviction due to nonpayment of rent (1). In response, many cities and states issued eviction moratoriums, and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) issued a federal moratorium, effective September 4, 2020, through August 26, 2021 (2). These state and federal orders were based on the premise that halting evictions could prevent the spread of COVID-19.

Eviction moratoriums may curb COVID-19 transmission through a number of mechanisms. Princeton University’s Eviction Lab tracked eviction filings in 25 cities and found that eviction notices and filings increased precipitously and immediately when state and local eviction moratoriums were allowed to expire (3, 4). These filings resulted in a wave of evictions 3–6 weeks later, varying in number and timing depending on the states’ court processes. Past research suggests that evictions lead to doubling up, transiency, crowded housing, and entry into homeless shelters (5–7), each of which can mean increased risk of exposure to COVID-19 (8–11). Increased risk of eviction may also have forced people to engage in work that exposed them to COVID-19 transmission. A recent simulation study predicted that evictions would increase COVID-19 infection risk not only for evicted households but for their entire communities, bending the shape of cities’ epidemic curves (12). However, little empirical evidence exists to gauge the real-world public-health implications of allowing evictions to proceed during the pandemic.

Leveraging variation in the expiration of state-based moratoriums during the summer of 2020 as a natural experiment, this study tested whether the lifting of eviction moratoriums was associated with COVID-19 incidence and mortality.

METHODS

Study population

The sample consisted of states that enacted eviction moratoriums over the study period (March 13, 2020, to September 3, 2020). States that never implemented a moratorium during this period were excluded from the study. States entered the study on the date they first implemented a moratorium blocking one or more stages of the eviction process (i.e., notice, filing, court hearing, court order, or enforcement of order), based on data drawn from the COVID-19 Eviction Moratoria and Housing Policy database (13). States were censored from the study when the CDC’s moratorium went into effect on September 4 or when they instituted a second state-level moratorium, whichever came first. Because all data used in our analyses were publicly available, the study was exempt from institutional review board review.

Outcomes

Outcome measures were daily, state-level counts of confirmed COVID-19 cases and deaths, drawn from the Johns Hopkins Center for Systems Science and Engineering COVID-19 time series data and as detailed in Web Appendix 1 (available at https://doi.org/10.1093/aje/kwab196) (14).

Independent variables

Eviction moratorium start and expiration dates were defined as the first and last dates with effective protections, respectively. To arrive at these dates, a team of lawyers and law students independently reviewed orders issued by governors, legislatures, and courts. Civil court closures, even in the absence of specific language regarding eviction proceedings, were counted as moratoriums (13). Because expiring eviction moratoriums do not immediately lead to evictions and, subsequently, COVID-19 risk, we expected a lag in effects. To reflect this, we coded the exposure to reflect weeks since moratoriums expired.

Covariates to control for confounding included time-varying, state-level factors likely associated with states’ COVID-19 response (including eviction moratoriums) as well as ascertainment or population rates of disease and deaths. These included COVID-19 test counts (derived from the COVID Tracking Project (15) and lagged by 1 week) as well as major public-health interventions, including lifting of stay-at-home orders, school closures, and mask mandates derived from the COVID-19 US State Policy Database (16). Public-health interventions were coded according to time since implementation: 0, 1, 2, 3, 4, or >4 weeks. Web Appendix 1 provides further details on model specification.

Statistical analysis

We modeled associations using a difference-in-difference approach with an event-study specification (17, 18). In the event study, lifting of eviction moratoriums was coded using a set of binary indicators representing leads and lags of eviction moratoriums lifting (i.e., weeks since a state’s moratorium was lifted). For states that never lifted moratoriums, all binary indicators for leads and lags were set to zero. As with a standard difference-in-difference analysis, event studies aim to identify the effect of a policy change using within-state variation in outcomes between pre- and posttreatment periods, comparing with outcomes in nontreated states to account for secular trends. Unlike a standard difference-in-difference model, however, event studies use a nonparametric specification of the policy effect, which allows the predicted outcome to vary across leads and lags relative to policy implementation (17). Examining trends in pretreatment event study coefficients allows researchers to assess potential violations of the parallel trends assumption underlying difference-in-difference analyses (18). To obtain effect estimates, we fitted population-averaged negative binomial regression models, with state-day as the unit of analysis, state population included in the model as an offset, a first-order autoregressive correlation structure, and conventionally derived (asymptotic) standard errors. Models included the above control variables as well as fixed effects for state and calendar week to account for underlying characteristics of states, time trends, and national policies such as the Coronavirus Aid, Relief, and Economic Security (CARES) Act eviction moratorium.

We used the models to calculate cases and deaths associated with the lifting of eviction moratoriums as a difference between predicted counts under observed moratorium conditions versus predicted counts under a counterfactual scenario in which no state lifted its moratorium during the study period. We then calculated cumulative counts associated with eviction moratoriums lifting by day, within states (provided in Web Tables 1 and 2). To generate national estimates of cumulative cases and deaths over time, we summed daily estimates across states. Analyses were performed using Stata/SE, version 15.1 (StataCorp LLC, College Station, Texas).

Additional analyses

We performed a number of analyses to test the sensitivity of our results to alternative model specifications. We applied a standard difference-in-difference specification, used different lags and coding schemes for the covariates, controlled for bars and restaurants reopening, and restricted the analysis to only states that lifted their moratoriums.

Web Tables 3 and 4 detail these alternate specifications. Additionally, we tested the sensitivity of our results to outliers, dropping 1 state at a time from regression models (Web Figure 1). Secondary analyses included interaction models to test for effect modification by 2 factors we expected to be associated with the timing and magnitude of effects: moratorium strength (i.e., moratoriums preventing eviction notices and filings vs. moratoriums that only blocked later stages of the eviction process) and state-level COVID-19 epidemic severity at the time moratoriums were lifted (Web Figures 2 and 3).

RESULTS

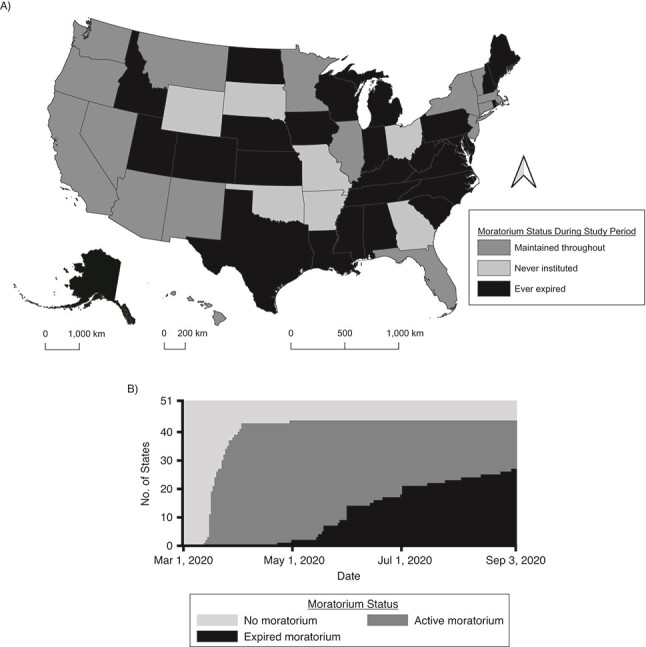

Forty-three states and the District of Columbia (henceforth referred to as a state) instituted a moratorium as early as March 13 and as late as April 30, 2020 (13). These 44 states contributed a total of 7,208 state-day observations, on average 176 days per state. Twenty-seven of these states (63%) lifted the moratorium during the study period (Figure 1A). Among the states that lifted their moratoriums, the median moratorium duration was 9.9 weeks (interquartile range, 8.3–15.1), with a median of 12 weeks (interquartile range, 7–14) with no moratorium protection (Figure 1B).

Figure 1.

Eviction moratoriums in US states, March 13 to September 3, 2020. A) Map of US states indicating eviction moratorium status over the study period; B) change in state eviction moratorium status over time. Data from the COVID-19 Eviction Moratoria and Housing Policy database (13).

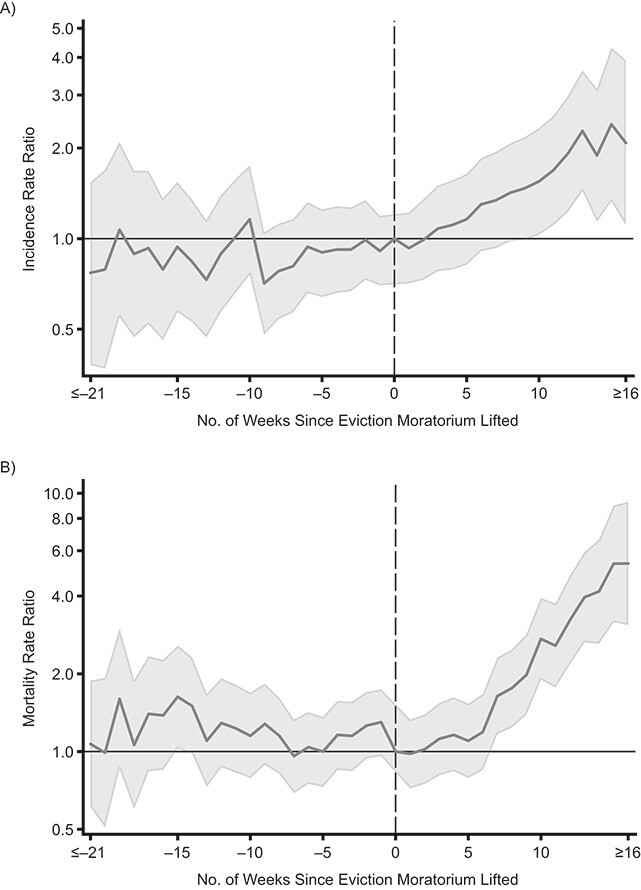

Figure 2 plots coefficients and confidence intervals (CIs) from event study models: incidence rate ratios (Figure 2A) and mortality rate ratios (Figure 2B) that estimate effects of moratorium expiration on incidence and mortality, respectively, for a given time period relative to the week that moratoriums expired. The reference group for these ratios includes observations from the week moratoriums expired as well as observations from states where moratoriums were maintained continuously. Before moratoriums were lifted, incidence rate ratios and mortality rate ratios were relatively stable with confidence intervals including 1 (Figure 2, Web Tables 3 and 4), suggesting little evidence of preexisting trends in states that went on to lift their moratoriums. Based on this result, we conclude that the assumptions of the event-study model are plausible in our data. After moratorium expiration, we saw incidence rate ratios greater than 1, indicating increased COVID-19 incidence associated with moratorium expiration. These incidence rate ratios increased steadily starting 2 weeks after states lifted their moratoriums (Figure 2A). Mortality rate ratios also indicated increased mortality associated with moratorium expiration, with the magnitude of mortality rate ratios increasing rapidly beginning 5 weeks after moratoriums expired (Figure 2B). Sixteen or more weeks after lifting their moratoriums, states had, on average, 2.1 times higher incidence (CI: 1.1, 3.9) and 5.4 times higher mortality (CI: 3.1, 9.3) than states that maintained their moratoriums.

Figure 2.

Adjusted rate ratios measuring the time-varying associations between US eviction moratorium expiration and daily COVID-19 incidence (new cases per population) (A) and mortality (deaths per population) (B), 2020. Rate ratios were modeled using negative binomial regression with fixed effects for state and calendar week, adjusting for testing rate, stay-at-home orders, school closures, and mask mandates. Event study coefficients estimate effects only in states with expiring moratoriums. States that maintained their moratoriums are included in models to control for secular trends. Data from the COVID-19 Eviction Moratoria and Housing Policy database, the Johns Hopkins Center for Systems Science and Engineering COVID-19 time series, and the COVID Tracking Project (13–15).

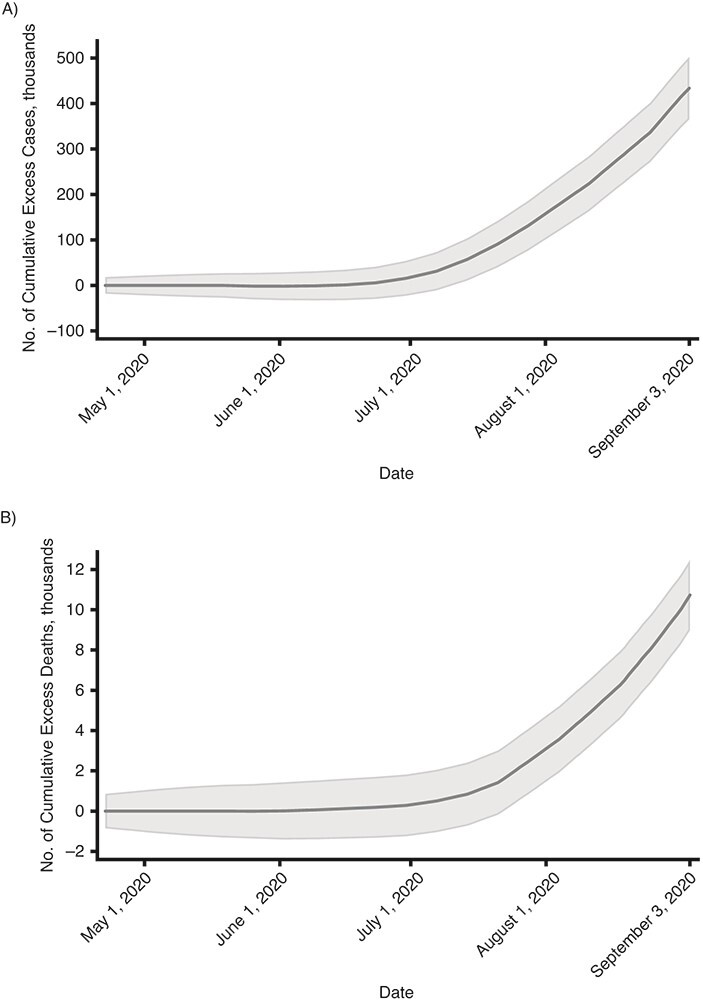

Nationally, the results translated to a total of 433,700 excess cases (CI: 365,200, 502,200, Figure 3A) and 10,700 excess deaths (CI: 8,900, 12,500; Figure 3B) associated with eviction moratoriums lifting over the course of the study period, with excess cases and deaths reaching statistical significance in July 2020. Trends are visualized in Figure 3; state-level estimates are provided in Web Tables 1 and 2.

Figure 3.

National estimates of cumulative excess cases (A) and cumulative excess deaths (B) associated with lifting of state eviction moratoriums in the United States from March 13 to September 3, 2020.

Results were robust to a number of sensitivity analyses in which we varied lags, included additional state-level policies as covariates, applied alternate statistical models, and tested for model sensitivity to outliers (Web Table 3 and Web Figure 1). In a model testing for effect modification by moratorium strength, we saw a steeper increase in COVID-19 incidence and mortality associated with lifting moratoriums among states that blocked only later stages of the eviction process, compared with states that blocked landlords from notice and filing (Web Figure 2). In a model testing for effect modification by COVID-19 epidemic severity, we saw that states with higher incidence when moratoriums expired saw larger moratorium-associated increases in COVID-19 incidence and mortality in the weeks shortly after expiration, although this pattern was reversed in later weeks (Web Figure 3).

DISCUSSION

The expiration of eviction moratoriums was associated with increased COVID-19 incidence and mortality in US states, supporting the public-health rationale for use of eviction moratoriums to prevent the spread of COVID-19. Associations grew over time, perhaps due to mounting displacement, transiency, crowding, and/or homelessness, increasing COVID-19 risk in communities as evictions were allowed to proceed (19). Our findings are consistent with those from 2 recent studies: a simulation study that found evictions could lead to significant increases in community rates of COVID-19 (12) and a county-level econometric analysis that found strong associations between housing precarity policies (eviction and utility disconnection moratoria) and COVID-19 outcomes (20).

The finding of a stronger association with mortality than with incidence may relate to the fact that COVID-19 deaths are better ascertained than cases. Low COVID-19 testing rates in underresourced communities and communities of color (21) could mean that cases are systematically undercaptured and underreported in the communities most affected by evictions. As such, associations with incidence may underestimate true associations. The finding may also suggest that the cases associated with evictions were more severe than the average for the state’s population. This is plausible, given that poor health and costs associated with health care may drive eviction risk, such that those most protected by the eviction moratorium were also at higher risk of COVID-19 mortality following an infection (22, 23). Moreover, structural racism and poverty, fundamental causes of eviction risk (24), also manifest as comorbidities and poor access to care in Black and Latinx communities and low-income households, creating vulnerabilities to COVID-19 case fatality (25).

This study has a number of limitations. Because we do not measure policy implementation (i.e., executed evictions), the results represent intent-to-treat estimates. Princeton’s Eviction Lab has documented a strong correlation between state moratoriums and eviction filings, but eviction moratoriums were not always 100% effective (26). Evictions occurring in states with active moratoriums would lead to a conservative bias in our results. This study relies on public-health surveillance of confirmed COVID-19 cases and deaths, likely underestimating true incidence and mortality. Additionally, many counties and municipalities issued moratoriums, rent relief, and other protective policies. These policies and local interventions are not captured in our study. Moreover, we do not model potential spillovers of policies from bordering states. Although we control for 3 key public-health interventions, there may be other policies we did not control for that tended to be implemented at the same time as eviction moratoriums across states, or other time-varying features of states correlated with the timing of eviction moratorium expirations that contribute to the differences in trends we observed between states that lifted versus maintained their moratoriums. Finally, we expect expiring eviction moratoriums to exacerbate racial/ethnic disparities in COVID-19 outcomes due to disproportionately high rates of evictions in Black and Latinx communities, but we were not able to test this hypothesis in our analysis due to data availability. We hope that as data quality improves, future researchers will be able to explore this critically important question in depth, with an explicitly antiracist lens.

Increased risk of illness and death from COVID-19 is one of many ways in which pandemic-era evictions may harm health. Research from before the pandemic has found that when adults lose their homes, they are more likely to use emergency care (27), frequently have greater difficulty managing chronic physical (28) and mental illnesses (29), and have lower survival rates (30). When pregnant women are evicted, they are more likely to deliver low birth weight and preterm infants (31). When children are evicted, they are more likely to become food insecure (32), suffer from lead poisoning (33), and fall behind cognitively (34). Because Black and Latinx households are disproportionately targeted for evictions (35, 36), evictions have the strong potential to exacerbate underlying racial/ethnic health disparities.

Our findings suggest that federal, state, and local polices to prevent eviction may help avert illness and deaths due to COVID-19. As the delta variant surges, robust, vigorously enforced moratoriums are essential to protect against eviction-related spread of COVID-19. On August 26, 2021, the US Supreme Court ruled to end the CDC’s eviction moratorium. In light of this ruling, local and state governments should consider reinstating or extending eviction moratoriums as part of their pandemic response. At the same time, we need policies to stem the tide of evictions expected once moratoriums expire. Although congress allocated $46.5 billion in emergency rental assistance, state and local governments’ progress to distribute the funds has been slow (37). Governments need to distribute assistance quickly and equitably in order to ensure that renters and their communities can emerge from this pandemic healthy and housed. Moving beyond COVID-19, we must promote efforts to increase the supply of and access to affordable housing stock as foundational to pandemic preparedness and health equity.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

Author affiliations: Department of Health Policy and Management, Fielding School of Public Health, University of California, Los Angeles, Los Angeles, California, United States (Kathryn M. Leifheit, Frederick J. Zimmerman); Department of Mental Health, Johns Hopkins University School of Public Health, Baltimore, Maryland, United States (Sabriya L. Linton); Department of Health Law, Policy, and Management, Boston University School of Public Health, Boston, Massachusetts, United States (Julia Raifman); Philip R. Lee Institute for Health Policy Studies, University of California, San Francisco, San Francisco, California, United States (Gabriel L. Schwartz); Wake Forest University School of Law, Winston-Salem, North Carolina, United States (Emily A. Benfer); Eviction Lab, Princeton University, Princeton, New Jersey, United States (Emily A. Benfer); Department of Health Policy and Management, Johns Hopkins School of Public Health, Baltimore, Maryland, United States (Craig Evan Pollack); Department of Medicine, Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine, Baltimore, Maryland, United States (Craig Evan Pollack); and Johns Hopkins School of Nursing, Baltimore, Maryland, United States (Craig Evan Pollack).

K.M.L. was supported by a postdoctoral fellowship from the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (grant AHRQ 2T32HS000046). J.R. was supported by the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation Evidence for Action program and by the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences through the Boston University Clinical and Translational Science Institute (grant 1UL1TR001430). E.A.B. was supported by the Pew Charitable Trusts’ Civil Legal System Modernization Initiative.

Access to data: K.M.L. had full access to all the data in the study and takes responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis. E.A.B. reviewed eviction moratorium dates and takes responsibility for the integrity of these data.

Data sharing: All data used in our analysis are publicly available. The authors are willing to make compiled state-level data available with publication, either via an online repository (e.g., GitHub) or by request via e-mail.

We thank Usama Bilal, Lelia Chaisson, and the JHSPH Social Epidemiology Student Organization for methodological review. We thank the COVID-19 US State Policy Database team, including Kristen Nocka, Rachel A. Scheckman, Claire Sontheimer, and Alexandra Skinner. We also thank project leads Karna Adam, Anne Kat Alexander (Eviction Lab), and Robert Koehler, as well as the entire COVID-19 Eviction Moratoria and Housing Policy: Federal, State, Commonwealth, and Territory research team.

The funders had no role in study design, collection, analysis, and interpretation of data, writing this report, or the decision to submit the report for publication. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the funding agencies. C.E.P. works part time on a temporary assignment with the Department of Housing and Urban Development (HUD), assisting the department on housing and health issues; the findings and conclusions in this article are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of HUD or other government agencies.

C.E.P. owns stock in Gilead Pharmaceuticals. The work detailed here does not evaluate any specific drug or intervention produced by Gilead. C.E.P. is an unpaid member of Enterprise Community Partners’ Health Advisory Council and was a paid consultant to the Open Communities Alliance. Preliminary results from this research were cited in Amicus Curiae briefs in support of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s national moratorium on eviction as a public-health measure. K.M.L., S.L.L., J.R., G.L.S., E.A.B., and C.E.P. signed on to the briefs as amici, and E.A.B. was the lead author of the brief. E.A.B. and K.M.L. have provided expert testimony to legislative bodies regarding public-health implications of evictions during the pandemic.

REFERENCES

- 1. Pollack CE, Leifheit KM, Linton SL. When storms collide: evictions, COVID-19, and health equity. Heal Aff Blog . Published August 4, 2020. 10.1377/hblog20200730.190964/full. Accessed August 26, 2020. [DOI]

- 2. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention . Temporary halt in residential evictions to prevent the further spread of COVID-19. Atlanta, GA: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (Federal Register Document Citataion 86 FR 16731). https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/more/pdf/CDC-Eviction-Moratorium-03292021.pdf. Accessed March 31, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- 3. Hepburn P, Louis R. Preliminary analysis: eviction filings during and after local eviction moratoria. Eviction Lab. https://evictionlab.org/moratoria-and-filings/. Accessed March 31, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- 4. Hepburn P, Louis R, Fish J, et al. U.S. eviction filing patterns in 2020 [published online April 27, 2021]. Socius. (doi: 10.1177/23780231211009983). [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Desmond M. Eviction and the reproduction of urban poverty. Am J Sociol. 2012;118(1):88–133. [Google Scholar]

- 6. Desmond M, Gershenson C, Kiviat B. Forced relocation and residential instability among urban renters. Soc Serv Rev. 2015;89(2):227–262. [Google Scholar]

- 7. Desmond M, Shollenberger T. Forced displacement from rental housing: prevalence and neighborhood consequences. Demography. 2015;52(5):1751–1772. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Maxmen A. Coronavirus is spreading under the radar in US homeless shelters. Nature. 2020;581(7807):129–130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Culhane D, Treglia D, Steif K, et al. Estimated emergency and observational/quarantine capacity need for the US homeless population related to COVID-19 exposure by county; projected hospitalizations, intensive care units and mortality. Working paper. https://works.bepress.com/dennis_culhane/237/. Accessed March 31, 2021.

- 10. Baggett TP, Keyes H, Sporn N, et al. Prevalence of SARS-CoV-2 infection in residents of a large homeless shelter in Boston. JAMA. 2020. 323(21):2191–2192. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Hsu HE, Ashe EM, Silverstein M, et al. Race/ethnicity, underlying medical conditions, homelessness, and hospitalization status of adult patients with COVID-19 at an urban safety-net medical center—Boston, Massachusetts, 2020. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2020;69(27):864–869. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Nande A, Sheen J, Walters EL, et al. The effect of eviction moratoria on the transmission of SARS-CoV-2. Nat Commun. 2021;12(1):2274. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Benfer EA, Koehler R, Alexander AK. COVID-19 US state policies: housing. https://statepolicies.com/data/graphs/housing/. Accessed December 31, 2020.

- 14. Johns Hopkins Center for Systems Science and Engineering . COVID-19 time series data. 2020. https://github.com/CSSEGISandData/COVID-19/tree/master/csse_covid_19_data/csse_covid_19_time_series. Accessed November 4, 2020.

- 15.The COVID Tracking Project. 2020. https://covidtracking.com/data/download. Accessed November 3, 2020.

- 16. Raifman J, Nocka K, Jones D, et al. COVID-19 US state policies. https://statepolicies.com/data/library/. Accessed December 31, 2020.

- 17. Goodman-Bacon A. Difference-in-differences with variation in treatment timing. NBER Working Papers. 2018. https://ideas.repec.org/p/nbr/nberwo/25018.html. Accessed December 31, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 18. Goodman-Bacon A, Marcus J. Using difference-in-differences to identify causal effects of COVID-19 policies [published May 18, 2020]. SSRN. https://ssrn.com/abstract=3603970. Accessed December 31, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 19. Benfer EA, Vlahov D, Long MY, et al. Eviction, health inequity, and the spread of COVID-19: housing policy as a primary pandemic mitigation strategy. J Urban Heal. 2021;98(1):1–12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Jowers K, Timmins C, Bhavsar N, et al. Housing precarity & the Covid-19 pandemic: impacts of utility disconnection and eviction moratoria on infections and deaths across US counties. NBER Working Papers. https://www.nber.org/papers/w28394. Accessed March 31, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- 21. Lieberman-Cribbin W, Tuminello S, Flores RM, et al. Disparities in COVID-19 testing and positivity in New York City. Am J Prev Med. 2020;59(3):326–332. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Allen HL, Eliason E, Zewde N, et al. Can Medicaid expansion prevent housing evictions? Health Aff. 2019;38(9):1451–1457. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Schwartz GL, Leifheit KM, Berkman LF, et al. Health selection into eviction: adverse birth outcomes and children’s risk of eviction through age 5 years. Am J Epidemiol. 2020;190(7):1260–1269. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Threet D. Household pulse survey shows continuing struggle among lowest-income renters. National Low Income Housing Coalition. 2020. https://hfront.org/2020/09/17/household-pulse-survey-shows-continuing-struggle-among-lowest-income-renters/. Accessed November 13, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 25. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention . Assessing risk factors for severe COVID-19 illness. https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/covid-data/investigations-discovery/assessing-risk-factors.html. Updated November 30, 2020. Accessed March 31, 2021. [PubMed]

- 26. The Eviction Lab, Benfer E. COVID-19 Eviction Tracking System. 2020. https://evictionlab.org/eviction-tracking/. Accessed November 23, 2020.

- 27. Collinson R, Reed D. The Effects of Evictions on Low-Income Households. Working Paper. Published October 2018. https://economics.nd.edu/assets/303258/jmp_rcollinson_1_.pdf. Accessed March 31, 2021.

- 28. Keene DE, Guo M, Murillo S. “That wasn’t really a place to worry about diabetes”: housing access and diabetes self-management among low-income adults. Soc Sci Med. 2018;197:71–77. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Desmond M, Kimbro RT. Eviction’s fallout: housing, hardship, and health. Soc Forces. 2015;94(1):295–324. [Google Scholar]

- 30. Rojas Y. Evictions and short-term all-cause mortality: a 3-year follow-up study of a middle-aged Swedish population. Int J Public Health. 2017;62(3):343–351. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Leifheit KM, Schwartz GL, Pollack CE, et al. Severe housing insecurity during pregnancy: association with adverse birth and infant outcomes. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2020;17(22):1–12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Leifheit KM, Schwartz GL, Pollack CE, et al. Eviction in early childhood and neighborhood poverty, food security, and obesity in later childhood and adolescence: evidence from a longitudinal birth cohort. SSM - Popul Heal. 2020;11:100575. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Richter FGC, Urban AH, Coulton C. Households Experiencing Eviction in Cleveland: A Mixed Methods Study of Cases in Cleveland Housing Court. Case Western Reserve University Center on Urban Poverty and Development. https://case.edu/socialwork/povertycenter/sites/case.edu.povertycenter/files/2019-11/BrieflyStated_11122019_accessible.pdf. Updated November 2019. Accessed March 31, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- 34. Schwartz GL. Cycles of Disadvantage: Eviction & Children’s Health in the United States[dissertation]. https://dash.harvard.edu/handle/1/37365869. 2020. Accessed March 31, 2021.

- 35. Desmond M, Gershenson C. Who gets evicted? Assessing individual, neighborhood, and network factors. Soc Sci Res. 2017;62:362–377. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Greenberg D, Gershenson C, Desmond M. Discrimination in evictions: empirical evidence and legal challenges. Harv Civ Rights-Civil Lib Law Rev. 2016;51:115. [Google Scholar]

- 37. Garrison J. 89% of federal rental assistance remains unspent as potential evictions crisis looms. USA Today. https://www.usatoday.com/story/news/politics/2021/08/25/89-federal-rental-assistance-unspent-evictions-crisis-looms/5584441001/. Accessed September 10, 2021. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.