Abstract

Coyne’s interpersonal theory of depression posits that those with depressive symptoms engage in maladaptive interpersonal behaviors that, although intended to assuage distress, push away social supports and increase depressive symptoms (Coyne, 1976). Excessive reassurance seeking, negative feedback seeking, and conversational self-focus are three behaviors implicated in Coyne’s theory, yet their correlates- apart from depressive symptoms- are poorly understood. The current study considered the potential role of intrapersonal emotion regulation deficits as an additional vulnerability factor for these behaviors. Mediation models further tested whether linkages between emotion regulation deficits and maladaptive interpersonal behaviors helped to explain short-term increases in depressive symptoms, as further suggested by theory. Older adolescents (N = 291, M age = 18.9) completed self-report measures of emotion regulation deficits, depressive symptoms, and the three maladaptive interpersonal behaviors during an initial lab visit and again four weeks later. A series of multiple regression models suggested that emotion regulation difficulties are uniquely associated with each of the behaviors over and above the impact of depressive symptoms. Mediation analyses suggested that only excessive reassurance seeking mediated the association between initial emotion regulation deficits and increased depressive symptoms over time. The clinical implications of these findings are discussed.

Keywords: emotion regulation, excessive reassurance seeking, negative feedback seeking, conversational self-focus, depressive symptoms

Depression is pervasive and associated with impaired functioning across domains. Nearly 20% of the population experiences a depressive disorder in their lifetime (Kessler & Bromet, 2013), and an even greater percentage are affected by subthreshold depressive symptoms (e.g., Cuijpers et al., 2004). Depressive symptoms are associated with multiple negative outcomes, including poor academic and work performance (DeRoma et al., 2009; Maurizi et al., 2013; Whooley et al., 2002), poor physical health (Fulkerson et al., 2004; Kandel & Davies, 1986; Marmorstein, 2009; Windle & Windle, 2001), as well as suicide and suicidal ideation (Chabrol et al., 2007; Goldston et al., 2006).

Importantly, depressive symptoms are associated with impaired social functioning (e.g., Kamper-DeMarco et al., 2020; Hirschfeld et al., 2000; Segrin, 2000), negative perceptions about one’s social skills (Lee et al., 2010; Steger & Kashdan, 2009), and diminished social support (Gotlib & Lee, 1989; Joiner & Timmons, 2009). One line of research has investigated specific interpersonal behaviors that are characteristic of depressed individuals, including excessive reassurance seeking (e.g., Evraire & Dozois, 2011; Joiner et al., 1999; Starr & Davila, 2008), negative feedback seeking (e.g., Borelli & Prinstein, 2006; Joiner & Metalsky, 1995), and conversational self-focus (e.g., Schwartz-Mette & Rose, 2009; 2016). Theory posits that these three interpersonal behaviors are enacted by depressed individuals to help reduce poorly regulated emotional distress (Coyne, 1976), yet their correlates, apart from depressive symptoms, are understudied. It is plausible that deficits in intrapersonal (i.e., internal) emotion regulation capabilities may also underlie these interpersonal behaviors, which may then lead to increased depressive symptoms.

The current project first investigates whether intrapersonal emotion regulation difficulties (either in conjunction with or over and above) depressive symptoms are associated with engagement in maladaptive interpersonal behaviors. Ineffectively recruiting close others for support with distress may reflect an inability to self-regulate. Further, we investigate whether short-term increases in depressive symptoms is an outcome of these initial associations. Both intrapersonal emotion regulation and the maladaptive interpersonal behaviors are associated with depressive symptoms, and the current project seeks to explain how these variables may be interrelated. Maladaptive interpersonal behaviors may be one mechanism that explains how internal emotion regulation deficits are associated with increased depressive symptoms.

Depressive Symptoms and Maladaptive Interpersonal Behaviors

Coyne’s interpersonal theory of depression posits that individuals with depressive symptoms recruit close others to provide assurances and to mitigate emotional distress (Coyne, 1976). To date, three depression-related interpersonal behaviors have been identified in the context of this theory: excessive reassurance seeking (e.g., Joiner et al., 1999), negative feedback seeking (e.g., Joiner & Metalsky, 1995; Swann et al., 1992), and conversational self-focus (e.g., Schwartz-Mette & Rose, 2009; 2016). These behaviors are similar in that they occur among those with depressive symptoms, involve trying to recruit others for support, and result in poor social and emotional outcomes.

Excessive reassurance seeking.

Excessive reassurance seeking, the first interpersonal behavior studied in the context of Coyne’s theory, is the tendency to repeatedly ask others for confirmation that they are cared for and liked (Joiner et al., 1992). A partner may at first provide such assurances, but the sincerity of these assurances is questioned by the depressed individual, who then continues to ask for support. Although the partner may initially comply with request for assurances, the repetitive behavior is perceived as aversive, and the partner may withdraw. Excessive reassurance seeking is associated with depressive symptoms both concurrently (Knobloch et al., 2001; Nesi & Prinstein, 2015; Prinstein et al., 2005) and over time (Evraire & Dozois, 2011; Joiner & Metalsky, 2001; Joiner & Schmidt, 1998; Nesi & Prinstein, 2015). What is more, the association between excessive reassurance seeking and depressive symptoms is bidirectional. Depressive symptoms give rise to later excessive reassurance seeking (Haeffel et al., 2007; Prinstein et al., 2005), and excessive reassurance seeking gives rise to later depressive symptoms (Davila, 2001; Haeffel et al., 2007). Social rejection and reduced social support are thought to be mechanisms that result in these longitudinal increases in depressive symptoms (Joiner & Metalsky, 1995; Prinstein et al., 2005; Starr & Davila, 2008).

Negative feedback seeking.

Negative feedback seeking is defined as recruiting others to confirm negative perceptions of oneself (Joiner & Metalsky, 1995). The construct is grounded in Swann’s self-verification theory, which suggests that individuals seek confirmation from others about their self-perceptions in order to maintain their self-image (Swann, 1983; 1987; 1990). Those with depressive symptoms, and presumably negative self-images, demonstrate a tendency to seek out negative feedback (Casbon et al., 2005; Joiner et al., 1997) and prefer the company of those who also view them negatively (Joiner et al., 1992; Swann et al., 1992). Like excessive reassurance seeking, negative feedback seeking is associated with concurrent depressive symptoms (Joiner, 1995; Joiner et al., 1997; Joiner & Metalsky, 1995). Additionally, Borelli and Prinstein (2006) report bidirectional associations between depressive symptoms and negative feedback seeking. Negative feedback seeking may help to maintain depressive symptoms due to negative social consequences of the behavior, including social rejection (Swann, Wenzlaff, Krull, et al., 1992) as well as lower social preference and perceived criticism by friends (Borelli & Prinstein, 2006).

Conversational self-focus.

Conversational self-focus, the most recent interpersonal behavior identified in the context of Coyne’s theory, is the tendency to redirect conversations to oneself (Schwartz-Mette & Rose, 2009). Schwartz-Mette and Rose (2009) characterize conversational self-focus as the behavioral manifestation of cognitive constructs such as self-focused attention (Mor & Winquist, 2002) and rumination (Nolen-Hoeksema, 1991), which are both related to depressive symptoms. To date, two studies support the concurrent association of conversational self-focus and depressive symptoms (Schwartz-Mette & Rose, 2009; 2016). Longitudinal associations of conversational self-focus with depressive symptoms have not yet been tested, but depressed individuals who engage in conversational self-focus do experience increased rejection by friends over time (Schwartz-Mette & Rose, 2016).

Intrapersonal Emotion Regulation Deficits as a Potential Correlate of Maladaptive Interpersonal Behaviors

The three interpersonal behaviors described above have been primarily studied in the context of depressive symptoms. There is some research, however, to suggest other correlates of these behaviors. Excessive reassurance seeking may be related to individual characteristics like attachment style, low levels of insight, sociotropy, and intolerance of uncertainty (Davila, 2001; Evraire & Dozois, 2011). Conversational self-focus shares some overlap with rumination (Schwartz-Mette & Rose, 2016). The current study explores whether deficits in an individual’s internal (i.e., intrapersonal) emotion regulation abilities may also be a correlate of each of the three maladaptive interpersonal behaviors addressed in this project.

Intrapersonal emotion regulation deficits are a likely correlate candidate for the three interpersonal behaviors associated with depression. Depression has been described as a disorder of emotion dysregulation (Joormann & Gotlib, 2010), and emotion regulation deficits are characteristic of both concurrent depressive symptoms (Campbell-Sills et al., 2006; Garnefski & Kraaij, 2006) as well as increases in depressive symptoms (Berking et al., 2014). It is therefore plausible that emotion regulation deficits are associated with depression-linked behaviors. There is an extensive literature investigating associations between poor emotion regulation and depressive behaviors. To date, self-injury (Gratz, 2003; Linehan, 1993), disengagement from activities (Hawkley et al., 2009), dysregulated sleep (Kahn et al., 2013; Palmer et al., 2018), and changes in eating behaviors (Evers et al., 2010; Svaldi et al., 2012) have been described as behavioral manifestations of poor emotion regulation among those with depressive symptoms. As emotion regulation deficits are associated with maladaptive solitary depression-linked behaviors (e.g., self-injury), it is plausible emotion regulation deficits are likewise linked with maladaptive interpersonal depression-linked behaviors. There is precedence for separating internal processes from their behavioral manifestations, including comparing co-rumination (Rose, 2002) to rumination (Nolen-Hoeksema, 1991) and conversational self-focus (Schwartz-Mette & Rose, 2009) to self-focused attention (Mor & Winquist, 2002).

Further, the maladaptive interpersonal behaviors, themselves, may reflect interpersonal attempts to manage poorly regulated distress. There is a growing literature to support that we turn to close others for assistance managing our emotional states (Barthel et al., 2018), a process that has been called interpersonal emotion regulation. Interpersonal emotion regulation describes interpersonal exchanges that function to influence one’s emotional state (Hofmann, 2014; Williams et al., 2018; Zaki & Williams, 2013). Zaki and Williams (2013) distinguish between processes that originate within oneself (intrinsic) and those initiated by a partner (extrinsic) as well as processes that are response-dependent and response-independent. Hofmann et al. (2016) identified enhancing positive affect (e.g., seeking out others to increase happiness/ joy), perspective taking (e.g., involving others to decrease worry), soothing (e.g., receiving comfort from others), and social modeling (e.g., seeking out others to understand how they cope) as four interpersonal emotion regulation goals. Some behavioral attempts to regulate emotion interpersonally may be adaptive, but individuals with significant difficulty regulating their emotions on their own may enact more maladaptive behaviors. Specifically, Dixon-Gordon et al. (2015) hypothesized that excessive reassurance seeking and co-rumination are intrinsic response-dependent forms of interpersonal emotion regulation behaviors linked to depressive symptoms. Marroquín (2011) identifies negative feedback seeking as an interpersonal support behavior associated with depressive symptoms. Conversational self-focus may also be an interpersonal emotion regulation strategy associated with depressive symptoms.

The idea that an individual with less developed intrapersonal emotion regulation abilities may turn to others has roots in the developmental literature. For example, research suggests that young children, with nascent intrapersonal emotion regulation abilities, rely more heavily on adults for emotion regulation support in comparison to adolescents who have more developed emotion regulation abilities (Martin & Ochsner, 2016). As such, older adolescents with emotion regulation difficulties may be more likely to reach out for support than those with better developed emotion regulation abilities. Further, those with emotion regulation difficulties may be prone to elicit regulation support in ways that are ineffective (i.e., employ maladaptive interpersonal emotion regulation strategies).

The first aim of the current study is to examine the unique contributions of both depressive symptoms and intrapersonal emotion regulation deficits to each of the three interpersonal behaviors. Whether interpersonal attempts to regulate negative affect, such as excessive reassurance seeking, negative feedback seeking, and conversational self-focus, are primarily associated with depressive symptoms or intrapersonal emotion regulation deficits is an important empirical question. These behaviors may indeed be primarily reflective of an interpersonal manifestation of the negative and self-focused nature of depressive symptoms. On the other hand, it is plausible that the behaviors reflect intrapersonal emotion regulation difficulties and may thus be characteristic of individuals with a variety of psychopathology symptoms, not just those with depressive symptoms. A third possibility is that both depressive symptoms and intrapersonal emotion regulation deficits each have significant, unique associations with engagement in excessive reassurance seeking, negative feedback seeking, and conversational self-focus. To date, no empirical studies have investigated the associations between depressive symptoms, deficits in intrapersonal emotion regulation, and the three maladaptive conversational behaviors. A recent study of middle adolescents demonstrated that each of the three behaviors is linked with intrapersonal emotion regulation difficulties (Schwartz-Mette et al., 2021), but did not examine the role of depressive symptoms. The current study examines the relative contributions of emotion regulation difficulties and depressive symptoms and their associations with these three maladaptive interpersonal behaviors.

Emotion Regulation Deficits, Maladaptive Interpersonal Behaviors, and Depressive Symptoms Over Time

As a second step, the current study also considers the associations of intrapersonal emotion regulation deficits, maladaptive interpersonal behaviors, and depressive symptoms over time. Coyne’s original theory clearly posits that poorly managed distress leads to engagement in maladaptive interpersonal behavior, which then leads to increased depressive symptoms. To date, however, most studies of the interpersonal theory of depression have either tested whether depressive symptoms predict interpersonal behaviors (e.g., Borelli & Prinstein, 2006; Haeffel et al., 2007) or whether interpersonal behaviors predict depressive symptoms (e.g., Joiner & Metalsky, 2001). Thus, the mediation model described by Coyne is understudied (Schwartz-Mette & Rose, 2016). The current study tests this mediation proposal in the context of the possibility that both intrapersonal emotion regulation deficits and depressive symptoms are associated with maladaptive interpersonal behaviors, which are then associated with increased depressive symptoms over time. Specifically, as an initial test of this proposal, a series of mediation models were tested in which each of the three behaviors mediated associations between initial depressive symptoms and emotion regulation deficits and later depressive symptoms over a short-term interval of four weeks. In addition to providing empirical support for the mediation model proposed by Coyne, this aim speaks to whether maladaptive interpersonal behaviors help explain the association between emotion regulation difficulties and increased depressive symptoms.

The Role of Gender

Finally, the current project investigated the potential that gender may impact the primary associations of interest. Beginning in adolescence and continuing across the life course, females are affected by depressive symptoms at approximately twice the rate as males (Nolen-Hoeksema & Jackson, 2001). In part, this increased vulnerability is thought to be related to interpersonal concerns including stronger orientation to and care for maintaining interpersonal relationships (Rudolph & Conley, 2005). Gender differences are likewise reported in the emotion regulation literature. In a meta-analysis investigating emotion regulation strategies, Tamres and colleagues (2002) describe that females report engaging in more types of regulation strategies than males. Nolen-Hoeksema and Aldao (2011) clarify that females are more likely to engage in both adaptive (e.g., reappraisal) and maladaptive emotion regulation strategies (e.g., rumination). However, little is understood about how gender impacts the interpersonal behaviors included in the current project. Excessive reassurance seeking seems to be more common among females (Prinstein et al., 2005), but there are no reported gender differences for negative feedback seeking (Borelli & Prinstein, 2006). Research investigating conversational self-focus has found either no gender differences (Schwartz-Mette & Rose, 2009), or gender differences favoring females (Schwartz-Mette & Rose, 2016). Moreover, gender differences in the proposed associations among depressive symptoms, emotion regulation deficits, and maladaptive interpersonal behaviors have not been examined. The current project investigates both mean-level gender differences in study variables as well as the role of gender in associations between emotion regulation, depressive symptoms, and each of the interpersonal behaviors. Considering mean-level gender differences favoring females for both depressive symptoms and emotion regulation, it is plausible that the strength of the associations between these two variables and each of the interpersonal behaviors is stronger for females.

The Current Study

Coyne’s interpersonal theory of depression (1976) describes the cyclical nature of depressive symptoms and maladaptive interpersonal behaviors. Prior research has investigated concurrent and longitudinal associations between depressive symptoms and excessive reassurance seeking, negative feedback seeking, and conversational self-focus. However, besides depressive symptoms, there is little research investigating vulnerability factors for the three behaviors. In the current study, we investigated the relative contributions of depressive symptoms and emotion regulation deficits. We hypothesized that emotion regulation difficulties would be associated with each of the maladaptive interpersonal behaviors over and above the effect of depressive symptoms. Additionally, in line with Coyne’s theory, we tested whether the maladaptive interpersonal behaviors mediated the association(s) between initial depressive symptoms and/or intrapersonal emotion regulation deficits and increased depressive symptoms over a short-term interval of four weeks. Finally, we investigated the potential role of gender in each of these associations.

Method

Participants

Participants were 291 (M age = 18.9 years, SD = 2.09; 60% female) undergraduate students enrolled in introductory psychology courses at a mid-sized public university in New England. Racial identity was reported by participants as: 93.8% White, 3.8% Asian, 2.7% Black or African American, 1.7% American Indian/ Alaskan Native, and <1% Native Hawaiian or Other Pacific Islander. Ethnic identity was reported as 95.5% Not Hispanic/ Latino and 4.5% Hispanic/ Latino, reflecting the general population from which the sample was drawn.

Procedure

Data for the current project were drawn from a larger study investigating friendship formation and emotional adjustment among older adolescents. Participants were recruited from a university undergraduate student subject pool. All participants were at least 18 years of age and provided written consent to participate. Participants were scheduled to attend an initial laboratory session (Time 1 assessment) in which they completed a battery of self-report measures and other laboratory tasks not relevant to the current study. Approximately four weeks later, participants completed another battery of online questionnaires via Qualtrics © (Time 2 assessment). All participants were compensated with academic course credit.

Measures

Demographics.

Participants reported basic demographic data including age, gender identity, ethnicity identity, and racial identity at Time 1.

Emotion regulation deficits.

Difficulties in emotion regulation were assessed at Time 1 using the Difficulties in Emotion Regulation Scale (DERS; Gratz & Roemer, 2004). The DERS includes 36 items that assess deficits in six areas including nonacceptance of emotional responses, difficulties engaging in goal directed behavior, impulse control difficulties, lack of emotional awareness, limited access to emotion regulation strategies, and lack of emotional clarity. Participants rated each item using a Likert-type scale ranging from 1 (almost never) to 5 (almost always). Scores were the sum of participants’ responses to all items. The measure showed excellent internal consistency at Time 1 (α = .95).

Depressive symptoms.

Depressive symptoms were assessed at Time 1 and Time 2 using the Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale (CES-D; Radloff, 1977). The CES-D includes 20 items and assesses affective, behavioral, cognitive, interpersonal, and somatic symptoms of depression. Participants reported the frequency of experiencing each symptom over the past week using a 4-point Likert scale ranging from 0 (Rarely or none of the time) to 3 (Most or all of the time). Participants’ overall scores were determined by summing responses to all items. The overall measures showed excellent internal consistency at Time 1 (α = .93) and Time 2 (α = .93).

Excessive reassurance seeking.

Excessive reassurance seeking was assessed at Time 1 using four items adapted from the Depressive Interpersonal Relationships Inventory (DIRI, Joiner & Metalsky, 2001). Participants indicated how often they repeatedly seek assurances from others on a Likert scale ranging from 1(Not at all) to 7 (Extremely often). Excessive reassurance seeking scores were the mean of participants’ responses to the four items. Internal consistency of items at Time 1 was good (α = .88).

Negative feedback seeking.

Negative feedback seeking was assessed at Time 1 using the Joiner and colleagues (1997) adaptation of the Feedback Seeking Questionnaire (FSQ; Swann, Wenzlaff, Krull, et al., 1992). The measure includes six questions in each of five domains (e.g., social competence, academic competence, athletic skills, physical attractiveness, artistic/musical competence). Participants are instructed to select as many of the questions from each domain as they would like to have a friend answer about them. Three of the questions for each section are positively worded (e.g., “What is some evidence you have seen that I have good social skills?”), and three are negatively worded (e.g., “What is some evidence you have seen that I do not have good social skills?”). Participants’ scores were created by summing the number of negatively-worded questions they selected across all five domains.

Conversational self-focus.

Conversational self-focus was assessed at Time 1 using six self-report items that measure participants’ tendency to turn conversations to themselves when speaking with a friend (Schwartz-Mette & Rose, 2009). Participants responded to each item using a 5-point Likert scale ranging from 1 (Not at all true) to 5 (Really true). Conversational self-focus scores were the mean of participants’ responses to all six items. The measure showed acceptable internal consistency at Time 1 (α = .76).

Missing Data

Some participants in the study had missing data. Specifically, at Time 1 < 1% of participants did not report on excessive reassurance seeking or conversational self-focus, and 6.5% of participants did not complete the Time 2 assessment and so were missing Time 2 depressive symptoms data. Little’s test indicated that these data were missing completely at random (MCAR) X2(39) = 46.66, p = .19. As such, missing data were imputed using an expectation maximum likelihood estimation procedure, and the full sample was retained for analyses.

Results

Descriptive Statistics and Correlations

Power analyses were conducted using G*Power software and suggested that our sample was suitable to detect a medium effect (power. 95) for our analyses. All analyses were conducted using SPSS 26.0. Means, standard deviations, and correlations among study variables are presented in Table 1. Depressive symptoms were stable over four weeks and were correlated with emotion regulation deficits at both time points. Overall and as expected, both Time 1 depressive symptoms and deficits in emotion regulation were positively and significantly correlated with each of the three interpersonal behaviors, but only excessive reassurance seeking and conversational self-focus were correlated with Time 2 depressive symptoms. In terms of associations among interpersonal behaviors, excessive reassurance seeking was significantly and positively correlated with negative feedback seeking, but conversational self-focus was not significantly related to either.

Table 1.

Descriptive Statistics and Correlations among Study Variables

| M | SD | 1. | 2. | 3. | 4. | 5. | 6. | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. T1 CES-D | 12.22 | 10.44 | -- | .78**** | .44**** | .15** | .19*** | .60**** |

| 2. T1 DERS | 77.37 | 23.62 | -- | .51**** | .20*** | .29**** | .62**** | |

| 3. T1 ERS | 1.70 | 1.10 | -- | .17** | .10 | .45**** | ||

| 4. T1 NFS | 5.97 | 3.93 | -- | .03 | .11 | |||

| 5. T1 CSF | 1.27 | 0.36 | -- | .19*** | ||||

| 6. T2 CES-D | 9.79 | 9.84 | -- |

Notes.

p < .05.

p ≤ .01.

p ≤ .001.

p < .0001.

CES-D = depressive symptoms. DERS = difficulties in emotion regulation. ERS = excessive reassurance seeking. NFS = negative feedback seeking. CSF = conversational self-focus.

Mean-Level Gender Differences

Mean-level gender differences were tested for each study variable by conducting independent samples t-tests. Females did not differ from males with regard to Time 1 depressive symptoms, emotion regulation deficits, conversational self-focus, or negative feedback seeking. Significant mean-level gender differences were observed for excessive reassurance seeking (t = 2.71, df = 288; p = .007) and Time 2 depressive symptoms (t = 2.33, df = 288; p = .02). Specifically, females reported higher levels of excessive reassurance seeking [females M (SD) = 1.82 (1.22); males M (SD) = 1.49 (0.83)] and higher levels of Time 2 depressive symptoms [females M (SD) = 10.72 (10.59); males M (SD) = 8.15 (8.11)] than did males.

Associations of Emotion Regulation Deficits and Depressive Symptoms with Interpersonal Behaviors

A series of multiple regression models were tested to examine whether emotion regulation deficits and depressive symptoms independently were associated with each of the three interpersonal behaviors of interest. Separate models were tested for excessive reassurance seeking, negative feedback seeking, and conversational self-focus. In each model, Time 1 depressive symptoms and Time 1 emotion regulation deficits were entered as simultaneous independent variables, and the Time 1 interpersonal behavior was the dependent variable. Due to the correlation between emotion regulation deficits and depressive symptoms, the potential for multicollinearity and its impact on regression models was assessed in each model using the variance inflation factor (VIF). The calculated VIF for all models was equal to 1, suggesting that multicollinearity was not an issue.

Subsequent analyses were conducted to determine if any of the relations of interest were further moderated by gender. In each case, the gender model was identical to the original model except that the main effect of gender, the interaction of emotion regulation deficits and gender, and the interaction of depressive symptoms and gender were added.

First, a model for excessive reassurance seeking was tested. The main effect of depressive symptoms was not significant in this model (ß = 0.11, p = .17). However, for the main effect of Time 1 emotion regulation deficits was significant (ß = 0.43, p < .001). Analyses next tested whether the effects of depressive symptoms or emotion regulation deficits were further moderated by gender. Neither of the two-way interactions with gender were significant.

Similarly, in the negative feedback seeking model, there was a significant positive main effect of Time 1 emotion regulation deficits (ß = .20, p = .03), but the effect of Time 1 depressive symptoms was not significant (ß = −.01, p = .95). In the model testing gender differences, none of the two-way interactions with gender were significant.

In the conversational self-focus model, the main effect of Time 1 emotion regulation deficits was significant (ß = 0.38, p <.001) over and above the main effect of depressive symptoms, which was not significant (ß = −0.11, p = .23). Finally, in the model testing potential gender differences, none of the two-way interactions with gender were significant.

Taken together, results indicate that emotion regulation deficits were associated with each of the maladaptive interpersonal behaviors over and above the effect of depressive symptoms. Moreover, the impact of depressive symptoms on each interpersonal behavior was not significant when emotion regulation deficits were included in each model. Gender did not further moderate any of these associations, suggesting that the associations were similar for those participants identifying as male and female.

Interpersonal Behavior as a Mediator of the Emotion Regulation-Depression Association

Analyses next tested whether each interpersonal behavior significantly mediated the association of Time 1 emotion regulation deficits with Time 2 depressive symptoms over four weeks. Separate mediation models were tested for excessive reassurance seeking, conversational self-focus, and negative feedback seeking. Building on the analyses above, in each model, Time 1 depressive symptoms and Time 1 emotion regulation deficits were included as predictor variables, the Time 1 interpersonal behavior was included as the mediator, and Time 2 depressive symptoms was the outcome variable. By effectively controlling for Time 1 depressive symptoms in each mediation model, results could speak to short-term changes in depressive symptoms over four weeks. Additional analyses were conducted to determine whether gender significantly moderated each potential mediated effect.

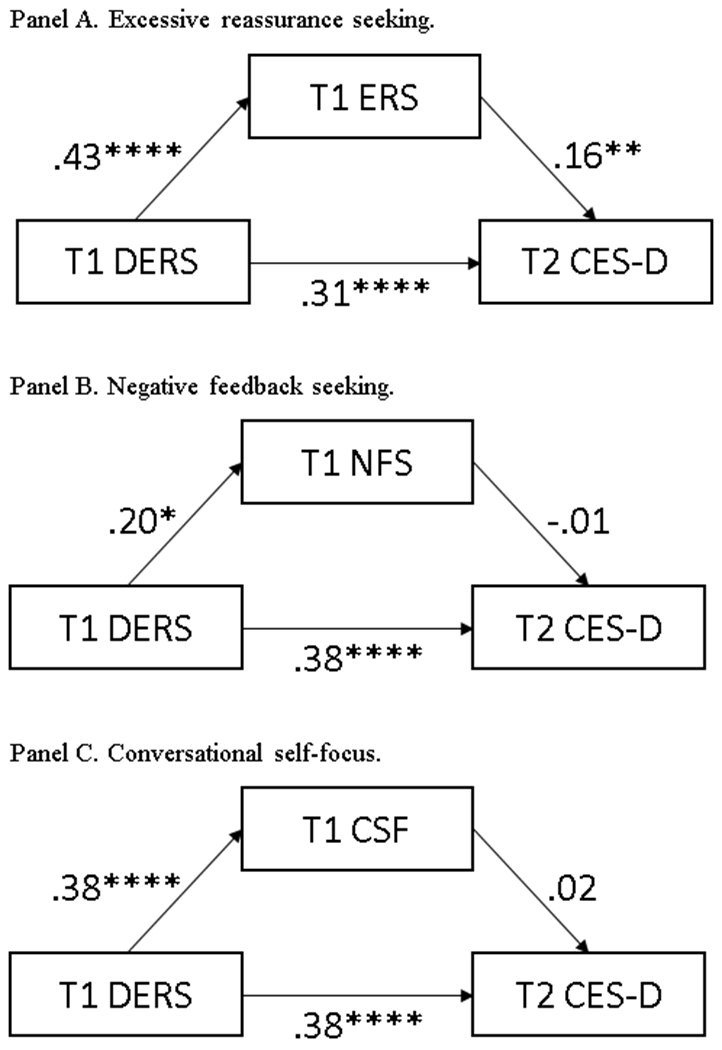

The first mediation model tested included excessive reassurance (see Figure 1, Panel A). Time 1 emotion regulation deficits were associated with Time 1 excessive reassurance seeking, over and above the impact of Time 1 depressive symptoms, which was not significant (ß = .11, p = .17). Excessive reassurance was then associated with increased depressive symptoms over four weeks. The indirect effect (IE) of excessive reassurance seeking was significant (standardized IE = .07; 95% CI: .004, .153), indicating that excessive reassurance seeking significantly mediated the association between initial emotion regulation deficits and increased depressive symptoms over time.

Figure 1.

Effects of emotion regulation deficits on later depressive symptoms via maladaptive interpersonal behavior.

Notes. *p < .05. **p < .01. ****p < .0001. DERS = difficulties in emotion regulation. CES-D = depressive symptoms. ERS = excessive reassurance seeking. NFS = negative feedback seeking. CSF = conversational self-focus.

In the mediation model including negative feedback seeking, Time 1 emotion regulation deficits were associated with Time 1 negative feedback seeking over and above the impact of Time 1 depressive symptoms, which was not significant (ß = −.01, p = .95). Negative feedback seeking was not significantly associated with increases in depressive symptoms, and the indirect effect of negative feedback seeking in the association of initial emotion regulation deficits and later depressive symptoms was not significant (standardized IE = .00; 95% CI: −.02, .02).

In the mediation model including conversational self-focus, emotion regulation deficits, but not Time 1 depressive symptoms (ß = −.11, p = .23), were associated with Time 1 conversational self-focus. Conversational self-focus was not significantly associated with increases in depressive symptoms over time. The indirect effect of conversational self-focus in the association between initial emotion regulation deficits and later depressive symptoms also was not significant (standardized IE = .01; 95% CI: −.02, .05).

Finally, analyses tested whether gender moderated any aspect of the mediation models. Specifically, gender was tested as a moderator of the path from Time 1 depressive symptoms to each interpersonal behavior (mediator), from Time 1 emotion regulation deficits to the mediator, from the mediator to Time 2 depressive symptoms, and from Time 1 emotion regulation deficits to Time 2 depressive symptoms. Gender did not significantly moderate any paths tested in any of the three mediation models.

Discussion

Coyne’s interpersonal theory of depression describes that those with depressive symptoms engage close others in maladaptive interpersonal efforts to assuage distress (Coyne, 1976). Excessive reassurance seeking (e.g., Evraire & Dozois, 2011), negative feedback seeking (e.g., Borelli & Prinstein, 2006; Joiner & Metalsky, 1995), and conversational self-focus (e.g., Schwartz-Mette & Rose, 2009; 2016) are three interpersonal behaviors characteristic of those with depressive symptoms. Apart from occurring among some with depressive symptoms, little is understood about correlates of these behaviors. The current project explored the role of intrapersonal emotion regulation deficits on these maladaptive interpersonal behaviors. Moreover, in line with the cyclical pattern described by Coyne (1976), research supports bidirectional associations between depressive symptoms and maladaptive interpersonal emotion regulation (e.g., Borelli & Prinstein, 2006; Haeffel et al., 2007). Considering the ‘chicken-or-the-egg’ nature of these associations, the current project further considered the role of deficits in intrapersonal emotion regulation as a possible catalyst for these bidirectional associations.

The first aim of the study was to examine the unique impacts of depressive symptoms and emotion regulation deficits on each of the maladaptive interpersonal behaviors. Although initial depressive symptoms and emotion regulation deficits were each positively correlated with one another and with excessive reassurance seeking, negative feedback seeking, and conversational self-focus, only emotion regulation deficits were uniquely associated with each behavior. That is, when both depressive symptoms and deficits in emotion regulation were entered into the same regression model as independent variables, only the effect of emotion regulation deficits was significant. These effects did not significantly differ according to participants’ gender identity. The regression model results underscore the importance of investigating underlying correlates of excessive reassurance seeking, negative feedback seeking, and conversational self-focus beyond depressive symptoms. This study was the first to examine the influence of intrapersonal emotion regulation deficits in the context of excessive reassurance seeking, negative feedback seeking, and conversational self-focus in older adolescents and supports initial findings from middle adolescence (Schwartz-Mette et al., 2021) that underlying intrapersonal emotion regulation deficits may be associated with interpersonal attempts to regulate distress.

As excessive reassurance seeking, negative feedback seeking, and conversational self-focus appear to be linked more strongly to emotion regulation deficits than with depressive symptoms, future research may explore these three behaviors as possible transdiagnostic factors. Emerging evidence may support this notion. Dixon-Gordon and colleagues (2018) have investigated excessive reassurance seeking as a potential transdiagnostic factor of personality and anxiety disorders. Interestingly, reassurance seeking was positively associated with borderline personality disorder and anxiety and was inversely associated with depressive symptoms. To date, associations of negative feedback seeking and conversational self-focus with regard to non-depressive disorders are understudied. Future research could investigate whether excessive reassurance seeking, negative feedback seeking, and conversational self-focus are indeed characteristic of multiple forms of distress and, perhaps, particularly those forms of psychopathology for which emotion regulation deficits are central.

In addition to exploring the relative contributions of deficits in emotion regulation and depressive symptoms to each of the interpersonal behaviors, we explored whether initial associations between emotion regulation deficits and the maladaptive interpersonal behaviors then led to short-term changes in depressive symptoms over a four-week interval. Prior research supports that depressive symptoms give rise to the maladaptive interpersonal behaviors (e.g., Prinstein et al., 2005) and that the maladaptive interpersonal behaviors give rise to increased depressive symptoms (e.g., Davila, 2001). Our data builds on these findings to suggest that emotion regulation deficits are associated with the maladaptive interpersonal behaviors over and above depressive symptoms. Thus, it was important to then investigate how this association may impact depressive symptoms over time. Interestingly, excessive reassurance seeking mediated the association between initial deficits in emotion regulation and increased depressive symptoms over time, and this was the case for both males and females. This finding supports and extends Coyne’s assertions that distressed individuals may turn to close others for repeated assurances that they are truly liked and cared for and this then leads to increased depressive symptoms. The current data cannot speak to why excessive reassurance seeking leads to increased depressive symptoms, but the interpersonal emotion regulation literature, as well as research informed by interpersonal theories of depression, may hold some clues.

In particular, Dixon-Gordon and colleagues (2015) described that maladaptive behaviors like excessive reassurance seeking are potential attempts at interpersonal emotion regulation with consequences for psychopathology. This fits with existing research demonstrating that excessive reassurance seeking does predict depressive symptoms over time (Davila, 2001; Evraire & Dozois, 2011). This result also helps to contextualize the findings related to contributions of emotion regulation deficits to excessive reassurance seeking in the broader context of interpersonal theories of depression. That is, although regulation deficits were more predictive of excessive reassurance seeking than were depressive symptoms, reassurance seeking did in fact contribute to increased depressive symptoms over time. Future research should evaluate whether excessive reassurance seeking predicts increased difficulties in intrapersonal emotion regulation. It may be that the behavior leads to depressive symptoms because it is ineffective in regulating distress and may even contribute to greater intrapersonal regulation problems over time.

Of note, neither negative feedback seeking nor conversational self-focus contributed to increased depressive symptoms in this way. Additional studies are needed to replicate these results and to further our understanding of why this might be the case. One possibility for further inquiry is to examine the utility of the assessment measures typically used to quantify these constructs. The measure used to assess negative feedback seeking (Joiner et al., 1997) prompts participants to indicate which positive questions (e.g., What is my best asset?) and/or which negative questions (e.g. What is my worst asset?) in six different domains (e.g., social competence, academic competence, physical attractiveness) they would like a friend to answer about them. It is possible that the measure captures only some relevant domains for negative feedback seeking and misses others. It also could be that the measure captures more of the cognitive aspects of negative feedback seeking (i.e., what one wants to know), as opposed to the behavioral components (i.e., what one actually asks about).

With respect to conversational self-focus, the self-report measure has been used in only two other published studies (Dueweke & Schwartz-Mette, 2018; Schwartz-Mette et al., 2021), and additional validity data is needed. The measure asks participants to indicate how they think they behave when speaking with friends about problems, but does not capture the degree of distress associated with the problems. Additionally, this level of perspective-taking may be difficult for those who engage in the behavior, precluding accurate self-reports. For each of the maladaptive interpersonal behaviors assessed in the current study, observational methodologies and peer report may be helpful in obtaining objective measures of these behaviors in future research. Prior research investigating conversational self-focus, for example, has used observational data to measure the construct (e.g., Schwartz-Mette & Rose, 2016).

The current project is an initial investigation into the associations between emotion regulation deficits, maladaptive interpersonal behaviors, and depressive symptoms and has several limitations and associated directions for future research. With respect to study design, the sample reflected the racial and ethnic identities of the population from which it was drawn and, as such, included a relatively racially homogeneous group of older adolescents. Future research including greater diversity of racial, ethnic, and other underrepresented identities will shed important light on whether these findings are generalizable. Additionally, data were examined at two timepoints over a four-week interval. Although the present project helps to clarify the relative associations of depressive symptoms and emotion dysregulation for each of the three interpersonal behaviors, the four-week interval may not fully capture increases in depressive symptoms. Future research could measure each variable at multiple timepoints over an expanded interval to investigate more complex models and extended longitudinal effects.

Additionally, although there exists emerging theoretical support to suggest these behaviors are attempts at interpersonal emotion regulation (Dixon-Gordon et al., 2015; Marroquín, 2011), there is scant empirical support for this association. Future research that more directly tests the motivations for engaging in these behaviors and the impacts of these behaviors on adolescents’ emotion regulation capabilities is needed. Relatedly, the current study only examined linkages with general emotion regulation deficits; future studies could examine associations with specific emotion regulation strategies (e.g., reappraisal, acceptance, distraction, rumination, etc.) to further clarify our understanding.

Moreover, although a range of depressive symptoms was observed in the current sample, this was not a clinical study. The level of depressive symptomology may have important implications for study results. At very low levels of depressive symptoms, individuals may not be motivated to engage in these more maladaptive attempts and may instead engage in other, less aversive depression-related conversational processes such as co-rumination (Rose, 2002). As depression levels increase, individuals may have fewer social supports (Coyne, 1976), and thus fewer opportunities to engage in these behaviors with close others. It is not known what role the level of symptoms may play in these associations, and future research is needed to elucidate this.

Finally, only self-report measures were used in this study. Future studies employing multiple methods of assessment, such as observations, are needed. Observations of maladaptive interpersonal behavior could address at least two potential issues. First, observations of problematic behavior may be more objective than self-reports. Studies that incorporate both self-report and observations of behavior could help to clarify any discrepancies between these sources of information and provide important direction for researchers designing new studies of these constructs. Second, the self-report measures of interpersonal behavior pertain to general (and perhaps stable) behavioral tendencies. Again, using more objective indices (e.g., observations, ecological momentary assessment) when testing these associations in future studies would enhance confidence in these initial results.

Clinical Implications

Despite the need for future research, the current study offers some potential clinical implications for individuals struggling with emotion regulation deficits. Results suggest that attending to underlying intrapersonal emotion regulation deficits, as opposed to depressive symptoms, may help to prevent some of the negative consequences of maladaptive interpersonal behaviors. That is, individuals with regulation problems could be offered more adaptive regulation strategies to be enacted in the interpersonal context. What is more, this type of intervention may have downstream consequences for preventing increased depressive symptoms over time.

Funding details:

During the preparation of this manuscript, Dr. Schwartz-Mette was partially supported by NIMH award R15 MH11634.

Footnotes

Disclosure statement: The authors have no conflicts of interest to disclose.

References

- Barthel AL, Hay A, Doan SN, & Hofmann SG (2018). Interpersonal emotion regulation: A review of social and developmental components. Behaviour Change, 35(4), 203–216. 10.1017/bec.2018.19 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Berking M, Wirtz CM, Svaldi J, & Hofmann SG (2014). Emotion regulation predicts symptoms of depression over five years. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 57, 13–20. 10.1016/j.brat.2014.03.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Borelli JL & Prinstein MJ (2006). Reciprocal, longitudinal associations among adolescents’ negative feedback-seeking, depressive symptoms, and peer relations. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology, 34(2), 159–169. 10.1007/s10802-005-9010-y [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Campbell-Sills L, Barlow DH, Brown TA, & Hofmann SG (2006). Effects of suppression and acceptance on emotional responses of individuals with anxiety and mood disorders. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 44(9), 1251–1263. 10.1016/j.brat.2005.10.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Casbon TS, Burns AB, Bradbury TN, & Joiner TE (2005). Receipt of negative feedback is related to increased negative feedback seeking among individuals with depressive symptoms. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 43(4), 485–504. 10.1016/j.brat.2004.03.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chabrol H, Rodgers R, & Rousseau A (2007). Relations between suicidal ideation and dimensions of depressive symptoms in high-school students. Journal of Adolescence, 30(4), 587–600. 10.1016/j.adolescence.2006.07.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coyne JC (1976). Depression and the response of others. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 85(2), 186–193. 10.1037/0021-843x.85.2.186 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cuijpers P, De Graaf R, & Van Dorsselaer S (2004). Minor depression: Risk profiles, functional disability, health care use and risk of developing major depression. Journal of Affective Disorders, 79(1-3), 71–79. 10.1016/s0165-0327(02)00348-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davila J (2001). Refining the association between excessive reassurance seeking and depressive symptoms: The role of related interpersonal constructs. Journal of Social and Clinical Psychology, 20(4), 538–559. 10.1521/jscp.20.4.538.22394 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- DeRoma VM, Leach JB, & Leverett JP (2009). The relationship between depression and college academic performance. College Student Journal, 43(2), 325–334. [Google Scholar]

- Dixon-Gordon KL, Bernecker SL, & Christensen K (2015). Recent innovations in the field of interpersonal emotion regulation. Current Opinion in Psychology, 3, 36–42. 10.1016/j.copsyc.2015.02.001 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Dixon-Gordon KL, Haliczer LA, Conkey LC, & Whalen DJ (2018). Difficulties in interpersonal emotion regulation: Initial development and validation of a self-report measure. Journal of Psychopathology and Behavioral Assessment, 40(3), 528–549. 10.1007/s10862-018-9647-9 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Dueweke AR, & Schwartz-Mette RA (2017). Social-cognitive and social-behavioral correlates of suicide risk in college students: Contributions from interpersonal theories of suicide and depression. Archives of Suicide Research, 22(2), 224–240. 10.1080/13811118.2017.1319310 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Evers C, Stok FM, & Ridder DT (2010). Feeding your feelings: Emotion regulation strategies and emotional eating. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 36(6), 792–804. 10.1177/0146167210371383 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Evraire LE, & Dozois DJ (2011). An integrative model of excessive reassurance seeking and negative feedback seeking in the development and maintenance of depression. Clinical Psychology Review, 31(8), 1291–1303. 10.1016/j.cpr.2011.07.014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fulkerson JA, Sherwood NE, Perry CL, Neumark-Sztainer D, & Story M (2004). Depressive symptoms and adolescent eating and health behaviors: A multifaceted view in a population-based sample. Preventive Medicine, 38(6), 865–875. 10.1016/j.ypmed.2003.12.028 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garnefski N, & Kraaij V (2006). Relationships between cognitive emotion regulation strategies and depressive symptoms: A comparative study of five specific samples. Personality and Individual Differences, 40(8), 1659–1669. 10.1016/j.paid.2005.12.009 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Goldston DB, Reboussin BA, & Daniel SS (2006). Predictors of suicide attempts: State and trait components. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 115(4), 842–849. 10.1037/0021-843x.115.4.842 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gotlib IH, & Lee CM (1989). The social functioning of depressed patients: A longitudinal assessment. Journal of Social and Clinical Psychology, 8(3), 223–237. 10.1521/jscp.1989.8.3.223 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Gratz KL (2003). Risk factors for and functions of deliberate self-harm: An empirical and conceptual review. Clinical Psychology: Science and Practice, 10(2), 192–205. 10.1093/clipsy.bpg022 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Gratz KL, & Roemer L (2004). Multidimensional assessment of emotion regulation and dysregulation: Development, factor structure, and initial validation of the difficulties in emotion regulation scale. Journal of Psychopathology and Behavioral Assessment, 26(1), 41–54. 10.1023/b:joba.0000007455.08539.94 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Haeffel GJ, Voelz ZR, & Joiner JT (2007). Vulnerability to depressive symptoms: Clarifying the role of excessive reassurance seeking and perceived social support in an interpersonal model of depression. Cognition & Emotion, 21(3), 681–688. 10.1080/02699930600684922 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hankin BL, & Abela JR (2011). Nonsuicidal self-injury in adolescence: Prospective rates and risk factors in a 2 ½year longitudinal study. Psychiatry Research, 186(1), 65–70. 10.1016/j.psychres.2010.07.056 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hawkley LC, Thisted RA, & Cacioppo JT (2009). Loneliness predicts reduced physical activity: Cross-sectional & longitudinal analyses. Health Psychology, 28(3), 354–363. 10.1037/a0014400 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hirschfeld RMA, Montgomery SA, Keller MB, Kasper S, Schatzberg AF, Möller HJ, Healy D, Baldwin D, Humble M, Versiani M, Montenegro R, & Bourgeois M (2000). Social functioning in depression: A review. The Journal of Clinical Psychiatry, 61(4), 268–275. 10.4088/JCP.v61n0405 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hofmann SG (2014). Interpersonal emotion regulation model of mood and anxiety disorders. Cognitive Therapy and Research, 38(5), 483–492. 10.1007/s10608-014-9620-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hofmann SG, Carpenter JK, & Curtiss J (2016). Interpersonal emotion regulation questionnaire (IERQ): Scale development and psychometric characteristics. Cognitive Therapy and Research, 40(3), 341–356. 10.1007/s10608-016-9756-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Joiner TE (1995). The price of soliciting and receiving negative feedback: Self-verification theory as a vulnerability to depression theory. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 104(2), 364–372. 10.1037/0021-843x.104.2.364 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Joiner TE, Alfano MS, & Metalsky GI (1992). When depression breeds contempt: Reassurance seeking, self-esteem, and rejection of depressed college students by their roommates. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 101(1), 165–173. 10.1037/0021-843x.101.1.165 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Joiner TE, Katz J, & Lew AS (1997). Self-verification and depression among youth psychiatric inpatients. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 106(4), 608–618. 10.1037/0021-843x.106.4.608 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Joiner TE, & Metalsky GI (1995). A prospective test of an integrative interpersonal theory of depression: A naturalistic study of college roommates. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 69(4), 778–788. 10.1037/0022-3514.69.4.778 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Joiner TE, & Metalsky GI (2001). Excessive reassurance seeking: Delineating a risk factor involved in the development of depressive symptoms. Psychological Science, 12(5), 371–378. 10.1111/1467-9280.00369 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Joiner TE, Metalsky GI, Gencoz F, & Gencoz T (2001). The relative specificity of excessive reassurance-seeking to depressive symptoms and diagnoses among clinical samples of adults and youth. Journal of Psychopathology and Behavioral Assessment, 23(1), 35–41. 10.1023/a:1011039406970 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Joiner TE, Metalsky GI, Katz J, & Beach SR (1999). Depression and excessive reassurance-seeking. Psychological Inquiry, 10(3), 269–278. 10.1207/s15327965pli1004_1 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Joiner TE, & Schmidt NB (1998). Excessive reassurance-seeking predicts depressive but not anxious reactions to acute stress. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 107(3), 533–537. 10.1037/0021-843x.107.3.533 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Joiner TE, & Timmons KA (2009). Depression in its interpersonal context. In Gotlib IH & Hammen CL (Eds.), Handbook of depression (pp. 322–339). Guilford Press. [Google Scholar]

- Joormann J, & Gotlib IH (2010). Emotion regulation in depression: Relation to cognitive inhibition. Cognition & Emotion, 24(2), 281–298. 10.1080/02699930903407948 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kahn M, Sheppes G, & Sadeh A (2013). Sleep and emotions: Bidirectional links and underlying mechanisms. International Journal of Psychophysiology, 89(2), 218–228. 10.1016/j.ijpsycho.2013.05.010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kamper-DeMarco KE, Shankman J, Fearey E, Lawrence HR, & Schwartz-Mette RA (2020). Linking social skills and adjustment. In Nangle DW, Erdley CA, & Schwartz-Mette RA (Eds.), Social skills across the life span (pp. 47–66). Academic Press. [Google Scholar]

- Kandel DB, & Davies M (1986). Adult sequelae of adolescent depressive symptoms. Archives of General Psychiatry, 43(3), 255–262. 10.1001/archpsyc.1986.01800030073007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kessler RC, & Bromet EJ (2013). The epidemiology of depression across cultures. Annual Review of Public Health, 34(1), 119–138. 10.1146/annurev-publhealth-031912-114409 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Knobloch LK, Knobloch-Fedders LM, & Durbin CE (2011). Depressive symptoms and relational uncertainty as predictors of reassurance-seeking and negative feedback-seeking in conversation. Communication Monographs, 78(4), 437–462. 10.1080/03637751.2011.618137 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lee A, Hankin LB, & Mermelstein RJ (2010). Perceived social competence, negative social interactions, and negative cognitive style predict depressive symptoms during Adolescence. Journal of Clinical Child & Adolescent Psychology, 39(5), 603–615. 10.1080/15374416.2010.501284 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Linehan MM (1993). Skills training manual for treating personality disorder. Guilford Press. [Google Scholar]

- Marmorstein NR (2009). Longitudinal associations between alcohol problems and depressive symptoms: Early adolescence through early adulthood. Alcoholism: Clinical and Experimental Research, 33(1), 49–59. 10.1111/j.1530-0277.2008.00810.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marroquín B (2011). Interpersonal emotion regulation as a mechanism of social support in depression. Clinical Psychology Review, 31(8), 1276–1290. 10.1016/j.cpr.2011.09.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martin RE, & Ochsner KN (2016). The neuroscience of emotion regulation development: Implications for education. Current Opinion in Behavioral Sciences, 10, 142–148. 10.1016/j.cobeha.2016.06.006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maurizi LK, Grogan-Kaylor A, Granillo MT, & Delva J (2013). The role of social relationships in the association between adolescents’ depressive symptoms and academic achievement. Children and Youth Services Review, 35(4), 618–625. 10.1016/j.childyouth.2013.01.006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mor N, & Winquist J (2002). Self-focused attention and negative affect: A meta-analysis. Psychological Bulletin, 128(4), 638–662. 10.1037/0033-2909.128.4.638 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nesi J, & Prinstein MJ (2015). Using social media for social comparison and feedback-seeking: Gender and popularity moderate associations with depressive symptoms. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology, 43(8), 1427–1438. 10.1007/s10802-015-0020-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nolen-Hoeksema S (1991). Responses to depression and their effects on the duration of depressive episodes. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 100(4), 569–582. 10.1037/0021-843x.100.4.569 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nolen-Hoeksema S, & Aldao A (2011). Gender and age differences in emotion regulation strategies and their relationship to depressive symptoms. Personality and Individual Differences, 51(6), 704–708. 10.1016/j.paid.2011.06.012 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Nolen-Hoeksema S, & Jackson B (2001). Mediators of the gender difference in rumination. Psychology of Women Quarterly, 25(1), 37–47. 10.1111/1471-6402.00005 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Palmer CA, Oosterhoff B, Bower JL, Kaplow JB, & Alfano CA (2018). Associations among adolescent sleep problems, emotion regulation, and affective disorders: Findings from a nationally representative sample. Journal of Psychiatric Research, 96, 1–8. 10.1016/j.jpsychires.2017.09.015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prinstein MJ, Borelli JL, Cheah CSL, Simon VA, & Aikins JW (2005). Adolescent girls’ interpersonal vulnerability to depressive symptoms: A longitudinal examination of reassurance-seeking and peer relationships. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 114(4), 676–688. 10.1037/0021-843X.114.4.676 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Radloff LS (1977). The CES-D scale. Applied Psychological Measurement, 1(3), 385–401. 10.1177/014662167700100306 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Rose A (2002). Co-rumination in the friendships of girls and boys. Child Development, 73(6), 1830–1843. 10.1111/1467-8624.00509 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rudolph KD, & Conley CS (2005). The socioemotional costs and benefits of social evaluative concerns: Do girls care too much? Journal of Personality, 73(1), 115–138. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schwartz-Mette RA, Lawrence HR, Shankman J, Fearey E, & Harrington R (2021). Intrapersonal emotion regulation difficulties and maladaptive interpersonal behavior in adolescence. Research on Child and Adolescent Psychopathology, 1–13. 10.1007/s10802-020-00739-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schwartz-Mette RA, & Rose AJ (2009). Conversational self-focus in adolescent friendships: Observational assessment of an interpersonal process and relations with internalizing symptoms and friendship quality. Journal of Social and Clinical Psychology, 28(10), 1263–1297. 10.1521/jscp.2009.28.10.1263 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schwartz-Mette RA, & Rose AJ (2016). Depressive symptoms and conversational self-focus in adolescents’ Friendships. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology, 44 (1), 87–100. 10.1007/s10802-015-9980-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Segrin C (2000). Social skills deficits associated with depression. Clinical Psychology Review, 20(3), 379–403. 10.1016/s0272-7358(98)00104-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Starr LR, & Davila J (2008). Excessive reassurance seeking, depression, and interpersonal rejection: A meta-analytic review. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 117(4), 762–775. 10.1037/a0013866 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steger MF, & Kashdan TB (2009). Depression and everyday social activity, belonging, and well-being. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 56(2), 289–300. 10.1037/a0015416 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Svaldi J, Griepenstroh J, Tuschen-Caffier B, & Ehring T (2012). Emotion regulation deficits in eating disorders: A marker of eating pathology or general psychopathology? Psychiatry Research, 197(1-2), 103–111. 10.1016/j.psychres.2011.11.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Swann WB (1983). Self-verification: Bringing social reality into harmony with the self. Social Psychological Perspectives on the Self, 2, 33–66. [Google Scholar]

- Swann WB (1987). Identity negotiation: Where two roads meet. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 53, 1038–1051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Swann WB (1990). To be known or to be adored: The interplay of self-enhancement and self-verification. In Higgins ET & Sorrentino RM (Eds.), Handbook of motivation and cognition (Vol. 2., pp. 408–448). Guilford Press. [Google Scholar]

- Swann WB, Wenzlaff RM, Krull DS, & Pelham BW (1992). Allure of negative feedback: Self-verification strivings among depressed persons. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 101, 293–306. 10.1037/0021-843X.101.2.293 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Swann WB, Wenzlaff RM, & Tafarodi RW (1992). Depression and the search for negative evaluations: More evidence of the role of self-verification strivings. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 101(2), 314–317. 10.1037/0021-843x.101.2.314 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tamres LK, Janicki D, & Helgeson VS (2002). Sex differences in coping behavior: A meta-analytic review and an examination of relative coping. Personality and Social Psychology Review, 6(1), 2–30. 10.1207/s15327957pspr0601_1 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Whooley MA, Kiefe CI, Chesney MA, Markovitz JH, Matthews K, & Hulley SB (2002). Depressive symptoms, unemployment, and loss of income. Archives of Internal Medicine, 162(22), 2614–2620. 10.1001/archinte.162.22.2614 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williams WC, Morelli SA, Ong DC, & Zaki J (2018). Interpersonal emotion regulation: Implications for affiliation, perceived support, relationships, and well-being. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 115(2), 224. 10.1037/pspi0000132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Windle M, & Windle RC (2001). Depressive symptoms and cigarette smoking among middle adolescents: Prospective associations and intrapersonal and interpersonal influences. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 69(2), 215–226. 10.1037/0022-006X.69.2.215 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zaki J, & Williams WC (2013). Interpersonal emotion regulation. Emotion, 13(5), 803–810. 10.1037/a0033839 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]