Abstract

Cobalt is a transition metal located in the fourth row of the periodic table and is a neighbor of iron and nickel. It has been considered an essential element for prokaryotes, human beings, and other mammals, but its essentiality for plants remains obscure. In this article, we proposed that cobalt (Co) is a potentially essential micronutrient of plants. Co is essential for the growth of many lower plants, such as marine algal species including diatoms, chrysophytes, and dinoflagellates, as well as for higher plants in the family Fabaceae or Leguminosae. The essentiality to leguminous plants is attributed to its role in nitrogen (N) fixation by symbiotic microbes, primarily rhizobia. Co is an integral component of cobalamin or vitamin B12, which is required by several enzymes involved in N2 fixation. In addition to symbiosis, a group of N2 fixing bacteria known as diazotrophs is able to situate in plant tissue as endophytes or closely associated with roots of plants including economically important crops, such as barley, corn, rice, sugarcane, and wheat. Their action in N2 fixation provides crops with the macronutrient of N. Co is a component of several enzymes and proteins, participating in plant metabolism. Plants may exhibit Co deficiency if there is a severe limitation in Co supply. Conversely, Co is toxic to plants at higher concentrations. High levels of Co result in pale-colored leaves, discolored veins, and the loss of leaves and can also cause iron deficiency in plants. It is anticipated that with the advance of omics, Co as a constitute of enzymes and proteins and its specific role in plant metabolism will be exclusively revealed. The confirmation of Co as an essential micronutrient will enrich our understanding of plant mineral nutrition and improve our practice in crop production.

Keywords: cobalamin, cobalt, endophytes, essential nutrients, micronutrients, symbiosis, vitamin B12, transporter

Introduction

Cobalt is an essential nutrient for prokaryotes, human beings, and other mammals but has not been considered an essential micronutrient for plants. Instead, this element, along with other elements, such as aluminum (Al), selenium (Se), silicon (Si), sodium (Na), and titanium (Ti), has been considered as a beneficial element for plant growth (Pilon-Smits et al., 2009; Lyu et al., 2017). An element that can improve plant health status at low concentrations but has toxic effects at high concentrations is known as a beneficial element (Pais, 1992). For an element to be considered essential, it must be required by plants to complete its life cycle, must not be replaceable by other elements, and must directly participate in plant metabolism (Arnon and Stout, 1939). It has been well-documented that there are 92 naturally occurring elements on the earth, wherein 82 of which have been found in plants (Reimann et al., 2001). Plants are able to absorb elements from soils either actively or passively due to their sessile nature. The occurrence of an element in plants, particularly in shoots, must have a purpose. Active transport of an element from roots to shoots may indicate a certain role it plays in plants. As stated in the study by Bertrand (1912), potentially, every element has a biological function that can be assessed properly against a background of a deficiency state, and every element is toxic when present at high enough concentrations, which is known as Bertrand's rule of metal necessity.

Significant progress has been made in plant mineral nutrition since the publication of Bertrand's rule (Bertrand, 1912) and the essentiality concept (Arnon and Stout, 1939). Among the beneficial elements, cobalt (Co) could potentially be an essential plant micronutrient. Co is a core element of cobalamin (vitamin B12 and its derivatives) and a cofactor of a wider range of enzymes and a component of different proteins in prokaryotes and animals (Maret and Vallee, 1993; Kobayashi and Shimizu, 1999; Harrop and Mascharak, 2013; Odaka and Kobayashi, 2013). Co-containing enzymes and proteins in plants require further investigation and clarification. Rhizobia and other nitrogen (N)-fixation bacteria require Co and cobalamin for fixing atmosphere dinitrogen (N2) into ammonia (NH3), providing plants with the essential macronutrient of N. Co plays a vital role in interaction with iron (Fe), nickel (Ni), and zinc (Zn) in maintaining cellular homeostasis. Similar to other essential micronutrients, plants respond to Co concentrations in soil: at low concentrations, it promotes plant growth but causes phytotoxicity at higher concentrations. However, it is different from other beneficial elements, as plants do exhibit Co deficiency when grown in soils with limited supply.

The objective of this article was to concisely review the importance of Co as a plant micronutrient including its role in N fixation, the occurrence of coenzyme or proteins, and its effects on plant growth as well as Co deficiency and toxicity. We intended that this review could raise an awareness that Co is a potentially essential micronutrient of plants, and further research is needed to confirm this proposition.

Cobalt and Nitrogen-Fixation in Plants

Cobalt was isolated by Brandt in 1735 and recognized as a new element by Bergman in 1780 (Lindsay and Kerr, 2011). The importance of Co to living things was realized in the 1930s during the investigation of ruminant livestock nutrition in Australia (Underwood and Filmer, 1935). Co was discovered to be essential for animals as it is a component of cobalamin. Five scientists were awarded Nobel Prizes for the investigation of cobalamin (Carpenter, 2004).

Cobalt Is a Core Element of Cobalamin

Cobalamin is a large molecule (C63H88O14N14PCo) comprised of a modified tetrapyrrole ring known as corrin with Co3+ in the center (Osman et al., 2021). Co is not inter-exchangeable with other metals in the cobalamin and cannot be released from the ring unless the ring is broken (Yamada, 2013), implying the significance of Co to cobalamin. There are two biologically active forms of cobalamin, namely, methylcobalamin and adenosylcobalamin in ruminants (Gonzalez-Montana et al., 2020). In human beings, Co is a cofactor of two enzymes, namely, ethylmalonyl-CoA mutase (MCM) and methionine synthase. MCM catalyzes the reversible isomerisation of l-methylmalonyl-CoA to succinyl-CoA. A deficiency of MCM causes an inherited metabolism disorder commonly known as methylmalonic aciduria. Methionine synthase utilizes cobalamin as a cofactor to produce methionine from homocysteine (Table 1). Reduced activity of this enzyme leads to megaloblastic anemia (Tjong et al., 2020). Ruminant animals produce vitamin B12 if there is an appropriate supply of Co in their diet. It was reported that 3 to 13% of the Co was incorporated into cobalamin by bacteria in the ruminant animals (Huwait et al., 2015).

Table 1.

Cobalt-containing enzymes, proteins, and transporter relevant or potentially relevant to plant metabolisms.

| Type | Name | Role | Organism | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Corrin Co enzymes | Ethylmalonyl-CoA mutase (MCM) | Catalysis of reversible isomerisation of l-methylmalonyl-CoA to succinyl-CoA | Mammals and bacteria | Odaka and Kobayashi, 2013; Gonzalez-Montana et al., 2020 |

| Methionine synthase | Synthesis of methionine from homocysteine | Mammals and bacteria | Odaka and Kobayashi, 2013; Gonzalez-Montana et al., 2020 | |

| Methylcobalamin-dependent methyltransferase | Transfer of a methyl group from different methyl donors to acceptor molecules | Mammals | Bridwell-Rabb and Drennan, 2017 | |

| Adenosylcobalamin-dependent isomerases | Catalysis of a variety of chemically difficult 1,2-rearrangements that proceed through a mechanism involving free radical intermediates | Mammals and bacteria | Marsh and Drennan, 2001 | |

| Ethanolamine ammonia-lyase | Conversion of ethanolamine to acetaldehyde and ammonia | Listeria monocytogenes and Escherichia coli | Harrop and Mascharak, 2013 | |

| Ribonucleotide reductase | Catalysis of the production of deoxyribonucleotides needed for DNA synthesis | Bacteria, mammals, yeast, and plants | Elledge et al., 1992; Yoo et al., 2009 | |

| Non-corrin Co enzymes | Nitrile hydratase (NHase) | Hydration of aromatic and small aliphatic nitriles into the corresponding amides | Rhodococcus rhodochrous and Pseudonocardia thermophila | Harrop and Mascharak, 2013; Odaka and Kobayashi, 2013 |

| Thiocyanate hydrolase (THase) | Hydration and subsequent Hydration of thiocyanate to produce carbonyl sulfide and ammonia | Thiobacillus thioparus (a Gram-negative betaproteobacterium) | Harrop and Mascharak, 2013 | |

| Methionine aminopeptidase (MA) | Cleavage of the N-terminal methionine from newly translated polypeptide chains | Bacteria, mammals, and yeast, plants | Giglione et al., 2000; Odaka and Kobayashi, 2013 | |

| Prolidase | Cleavage of a peptide bond adjacent to a proline residue | Archaea (Pyrococcus furiosus), bacteria, fungi, and plants | Harrop and Mascharak, 2013; Odaka and Kobayashi, 2013 | |

| D-xylose isomerase | Conversion of D-xylose and D-glucose into D-xylulose and D-fructose, respectively | Streptomyces diastaticus (an alkaliphilic and thermophillic bacterium) | Bhosale et al., 1996 | |

| Methylmalonyl-CoA carboxytransferase | Catalysis of carboxyl transfer between two organic molecules, using two separate carboxyltransferase domains. | Propionibacterium shermanii (Gram-positive bacterium) | Odaka and Kobayashi, 2013 | |

| Carbonic anhydrase or carbonate dehydratase | Catalysis of the conversion of CO2 to reversibly | Bacteria, fungi, algae, and plants | Jensen et al., 2020 | |

| Carboxypeptidases | Hydrolyzation of the C-terminal residues of peptides and proteins and release free amino acids individually | Animals, bacteria, fungi, and plants | Maret and Vallee, 1993 | |

| Urease | Catalysis of the seemingly simple hydrolysis of urea into ammonia and carbamic acid | Archaea, algae, bacteria, fungi, and plants | Carter et al., 2009 | |

| Aldehyde decarboxylase | Decarboxylation of aldehyde | Botryococcus braunii (green algae) | Odaka and Kobayashi, 2013 | |

| Bromoperoxidase | Bromination | Bacteria | Odaka and Kobayashi, 2013 | |

| Co transporters | NiCoT | Transport of Co2+ and Ni2+ | Rhodococcus rhodochrous | Odaka and Kobayashi, 2013 |

| HupE/UreJ | Mediation of uptake of Ni2+ and Co2+ | Collimonas fungivorans | Eitinger, 2013 | |

| CbiMNQO | An energy-coupling factor (ECF) transporter for Ni2+ and Co2+ | Salmonella enterica | Eitinger, 2013 | |

| CorA | Transport system for Mg2+ and Co2+ | Thermotoga maritima | Eitinger, 2013 | |

| IRT1 | Absorption of Fe2+ and Co2+ | Plants | Korshunova et al., 1999; Conte and Walker, 2011 | |

| FPN1 | Transport of Fe2+ and Co2+ to xylem | Plants | Korshunova et al., 1999; Conte and Walker, 2011 | |

| FPN2 | Transport of Fe2+ and Co2+ to vacuole | Plants | Korshunova et al., 1999; Conte and Walker, 2011 | |

| ARG1 | An ABC transporter to transporting Ni2+ and Co2+ in chloroplast | Plants | Li et al., 2020 |

Cobalamin Biosynthesis in Bacteria and Archaea

The natural forms of vitamin B12 are 1,5-deoxyadenosylcobalamin, hydroxycobalamin, and methylcobalamin (Nohwar et al., 2020). They are synthesized by a selected subset of bacteria and archaea (Heal et al., 2017; Guo and Chen, 2018), which include Bacillus, Escherichia, Fervidobacterium, Kosmotoga, Lactobacillus, Mesotoga, Nitrosopumilus, Petrotoga, Propionibacterium, Proteobacteria, Pseudomonas, Rhodobacter, Rhizobium, Salmonella, Sinorhizobium, Thermosipho, and Thermotoga (Doxey et al., 2015; Fang et al., 2017). Cyanocobalamin is not a natural form but commercially synthesized B12. The production of vitamin B12 by these microbes involves about 30 enzymatic steps through either aerobic or anaerobic pathways. In addition to being essential for fat and carbohydrate metabolism and synthesis of DNA, vitamin B12 is a cofactor of many enzymes. There are more than 20 cobalamin-dependent enzymes in those prokaryotes including diol dehydratase, ethanolamine ammonia-lyase, glutamate, and methylmalonyl-CoA mutase, methionine synthase, and ribonucleotide reductase (Marsh, 1999) (Table 1). These enzymes catalyze a series of transmethylation and rearrangement reactions (Rodionov et al., 2003). Thus, Co is essential for those archaea and bacteria.

Cobalt Plays an Important Role in Biological Nitrogen Fixation

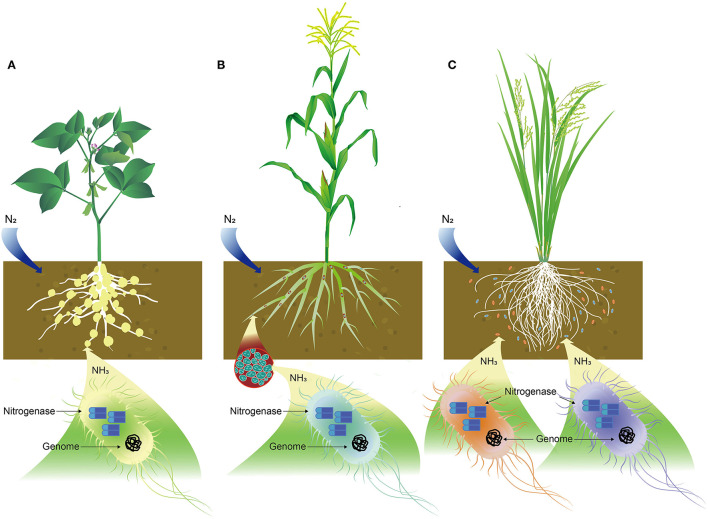

Biological N fixation is a process of converting N2 from the atmosphere into plant-usable form, primarily NH3. Biological N fixation (BNF) is carried out by a group of prokaryotes known as diazotrophs, which are listed in Table 2, including bacteria, mainly Rhizobium, Frankia, Azotobacter, Mycobaterium, Azospirillum, and Bacillus; Archaea, such as Methanococcales, Methanobacteriatles, and Methanomicrobiales, and cyanobacteria, like Anabaena, Nostoc, Toypothrix, and Anabaenopsis (Soumare et al., 2020). N2-fixing organisms are also classified into three categories: symbiotic, endophytic, and associated groups (Figure 1). Such classifications may not be accurate as some of them, such as those from Acetobacter and Azospirillum, could be associated, as well as endophytic bacteria.

Table 2.

Representative nitrogen fixing bacteria.

| Type of association | Bacteria | Plants | References |

|---|---|---|---|

| Symbiosis | Cyanobacteria | Bryophyte symbiosisNostoc-Gunnera symbiosisAzolla symbiosisCycad symbiosisLichen symbiosis | Adams et al., 2013 |

| Rhizobia (Bradyrhizobium, Burkholderia, Ensifer, and Mesorhizobium) | Legume-Rhizobia symbiosis | Andrews and Andrews, 2017 | |

| Frankia | Non-legume-Frankia symbiosis: Actinorhizal plants | Wall, 2000 | |

| Endophyte | Azospirillum amazomense; Bacillus spp.; Burkhoderia spp.; Gluconacetobacter diazotrophicus; Paenibacillus polymyxa; and Pseudomonas aeruginosa | RiceMaizeRiceSugarcaneMaizeWheat | Puri et al., 2018; Rana et al., 2020 |

| Association | Acetobacter nitrocaptans; Azospirillum spp.; Bacillus azotofixans; and Pseudomonas spp. | Sugarcane associationGrasses and cereals (maize, sorghum, wheat)Grasses, sugarcane, wheatWetland rice | Boddey and Dobereiner, 1988; Rosenblueth et al., 2018 |

| Cyanobacteria; Acetobacter diazotrophicus; Azoarcus spp.; Azospirillum spp.; and Azotobacter spp. | SugarcaneGrassesMaize, wheatSugarcane | Steenhoudt and Vanderleyden, 2000 |

Figure 1.

Schematic illustration of nitrogen (N) fixation in bacteria. (A) Symbiotic relationship of Rhizobium with soybean in N fixation, (B) endophytic bacteria, like Azospirillum lipoferum in corn plant root for N fixation, and (C) N-fixing bacteria, such as Azotobacter and Azospirillum associated with rice plant roots where cobalt or cobalamin plays important role in N fixation.

Cobalt Is Essential for Symbiotic Bacteria in N Fixation

There are two major symbioses between N2-fixing bacteria and higher plants, one is rhizobia with leguminous plants and the other is Frankia with actinorhizal plants (Wall, 2000). The former involves more than 1,700 plant species in the family Fabaceae, which includes some economically important crops, such as alfalfa, beans, peas, and soybeans. More than 220 species are actinorhizal plants, which are mainly trees and shrubs forming symbiotic relationships with Frankia.

Rhizobia are gram-negative bacteria encompassing Rhizobium, Azorhizobium, Sinorhizobium, Bradyrhizobium, and Mesorhizobium (Table 2, Figure 1A). Co was identified to be essential for Rhizobium in the 1950s and 1960s (Ahmed and Evans, 1960; Reisenauer, 1960). Rhizobium uses nitrogenase to catalyze the conversion of N2 to NH3, which can be readily absorbed and assimilated by plants. Three enzymes, namely, methionine synthase, methyl malonyl-CoA mutase, and ribonucleotide reductase in Rhizobium and Bradyrhizobium species, are known to be cobalamin-dependent and significantly affect nodulation and N fixation. Early studies showed that four soybean seedlings inoculated with rhizobia supplemented with 1 μg/L Co were healthy and produced 25.3 g of dry weight. On the contrary, four rhizobia-inoculated seedlings devoid of Co encountered N-deficiency symptoms and produced 16.6 g of dry weight, a 34.4% reduction in biomass due to the absence of Co (Ahmed and Evans, 1959). A close relationship was established amongst Co supply, cobalamin content in Rhizobium, leghemoglobin formation, N fixation, and plant growth (Kliewer and Evans, 1963a,b). The deficiency in Co significantly affects methionine synthase by reducing methionine synthesis, which subsequently decreases protein synthesis and produces smaller-sized bacteroids (bacteria in the nodules capable of N fixation) (Marschner, 2011). Methyl malonyl-CoA mutase catalyzes the production of leghemoglobin. If Co becomes limited, leghemoglobin synthesis is directly affected, resulting in reduced N fixation and ultimately a shortage of N supply. This is because leghemoglobin can protect nitrogenase from oxygen by limiting its supply (Hopkins, 1995). Ribonucleotide reductase is a cobalamin-dependent enzyme that catalyzes the reduction of ribonucleotides to deoxyribonucleotides, which is a rate-limiting step in DNA synthesis (Kolberg et al., 2004).

The genus Frankia is composed of gram-positive and gram-variable actinomycetes (Wall, 2000). It infects plants through root hairs and produces nodules in the pericycle. Frankia in nodules develops vesicles in which nitrogenase is suited (Huss-Danell, 1997). Co is needed for the synthesis of cobalamin which is in turn needed for N fixation. Actinomyceters are known as active producers of cobalamin (Hewitt and Bond, 1966). N fixation by actinorhizal plants appears to be comparable to the magnitude as that of the legumes (Wall, 2000).

Other symbioses occur in cyanobacteria with Gunnera and cycads. The genus Nostoc infected specialized gland organs located on the stems of Gunnera, such as G. chilensis and G. magellanica (Johansson and Bergman, 1994). Cyanobacteria also form symbiotic relationships with cycads in a special type of root system called coralloid roots (Chang et al., 2019). It has been well-documented that cyanobacteria require Co for the biosynthesis of cobalamin (Cavet et al., 2003).

Cobalt and Endophytic Bacteria in N Fixation

A group of N2-fixing bacteria can form an endophytic relationship with many crop plants (Table 2, Figure 1B). By definition, any bacterium could be considered to be an endophytic diazotroph if (1) it can be isolated from surface-disinfected plant tissue or extracted inside the plants, (2) it proves to be located inside the plant, either intra- or inter-cellularly by in-situ identification, and (3) it fixes N2, as demonstrated by acetylene reduction and/or 15N-enrichment (Hartmann et al., 2000; Gupta et al., 2012). Common N2-fixing endophytic bacteria include Azoarcus spp. BH72 and Pseudomonas stutzeri A1501 in rice (Wang et al., 2016; Pham et al., 2017), Achromobacter spp. EMC1936 in tomato (Abdel-Rahman et al., 2017), Azospirillum lipoferum 4B in maize (Garcia et al., 2017), Burkholderia phytofirmans PsJN in grape plants (Compant et al., 2008), Enterobacter cloacae ENHKU01 in pepper (Santoyo et al., 2016), Gluconoacetobacter diazotrophicus PaI5 in sugarcane (James et al., 2001). Other bacteria, such as Herbaspirillum, Klebsiella, and Serratia also are implicated in N2 fixation (Rothballer et al., 2008; Franche et al., 2009). These bacteria possess either iron or vanadium nitrogenase that fixes N2 into NH3.

The complete genome of Azoarcus sp. BH72 (Krause et al., 2006), G. diazotrophicus PAl 5 (Bertalan et al., 2009), Herbaspirillum seropedicae SmR1 (Pedrosa et al., 2011), and S. marcesens RSC-14 (Khan et al., 2017) were sequenced. Among them, genomic and proteomic profiles of Azoarcus sp., Gluconoacetobacter diazotrophicus, Herbaspirillum seropedicae, and Serratia marcesens have been studied (Krause et al., 2006; Gupta et al., 2012). These bacteria have co-transport systems for Co2+, Zn2+, and Cd2+ or Ca2+, Co2+, Zn2+, and Cd2+ as well as putative receptors for vitamin B12. Comparative genomic analyses of Ni, Co, and vitamin B12 utilization showed that both metals are widely used by the bacteria and archaea, with the most common prokaryotic transporter being Cbi/NikMNQO. Ni-Fe hydrogenase, Ni-dependent urease, B12-dependent ribonucleotide reductase, methionine synthase, and methymalonly-CoA mutase are the most widespread metalloproteins for Ni and Co (Zhang et al., 2009). Thus, Co is needed by these bacteria.

Cobalt and Plant Associated N2 Fixing Bacteria

Associated N2-fixing bacteria include Azotobacter, Azospirillum, Beijerinckia, Burkholderia, Clostridium, Herbaspirillum, Gluconacetobacter, Methanosarcina, and Paenibacillus (Table 2, Figure 1C). These bacteria are associated with the roots of a wide range of plants, including corn, rice, sugarcane, and wheat (Aasfar et al., 2021). Among them, the genus Azotobacter was first reported in 1901 and has been used as a biofertilizer thereafter (Gerlach and Vogel, 1902). Notable species found in soils are A. chroococcum, A. vinelandii, A. beigerinckii, A. armeniacus, A. nigricans, and A. paspali (Das, 2019). The genome of A. vinelandii DJ has been sequenced (Setubal et al., 2009). N fixation in these species is under aerobic conditions, and two-component proteins of Mo-dependent nitrogenase catalyze N2 into NH3. Co and vitamin B12 were found to be required by A. vinelandii OP. Additionally, 5,6-dimethylbenzimidazolylcobamide coenzyme was identified in this species, which might play an important role in N fixation (Nicholas et al., 1962). Furthermore, higher concentrations of Co were needed for A. vinelandii to fix N2 than was needed for the utilization of ammonium compounds (Evans and Kliewer, 1964). Co at a concentration of 0.1 mg/L was reported to increase N fixation in A. chroococcum in Jensen's medium (Iswaran and Rao Sundara, 1964). Culture of A. chroococcum in half-strength N-free Jensen's broth showed that N fixation was enhanced after supplemented with Co at 12.5 mg/L or 25 mg/L (Orji et al., 2018). Azotobacters were able to biosynthesize a series of vitamins, including B12 in chemically-defined media and dialyzed soil media (Gonzalez-Lopez et al., 1983; El-Essawy et al., 1984). In addition to A. vinelandii and A. chroococcum, Pseudomonas fluorescens, Bacillus megaterium, Bacillus firmus, and Sinorhizobium meliloti also produce cobalamin (Palacios et al., 2014), and the synthesized cobalamin may implicate the enhanced N fixation in these bacteria.

Azosprillum is another important genus of plant-associated N2-fixing bacteria. A. brasilense cultured on medium supplemented with 0.2 mM Co was able to accumulate Co up to 0.1 to 0.6 mg per gram of dry biomass (Kamnev et al., 2001). 57Co emission Mössbauer spectroscopy (EMS) studies of Co in Azospirillum brasilense Sp245 showed that Co activated glutamine synthetase to have two different Co forms at its active sites. In vitro, biochemical and spectroscopic analyses showed that Co2+ is among the divalent cations, along with Mg2+ and Mn2+, most effective in supporting the activity of glutamine synthetase at different adenylylation states, a key enzyme of N metabolism (Antonyuk et al., 2001).

Nitrogen Fixing Bacteria and Crop Productivity

Nitrogen is an essential macronutrient for plants. The application of synthetic N fertilizers has greatly enhanced crop production but also has caused serious environmental problems, such as groundwater contamination and surface water eutrophication (Hansen et al., 2017). As a result, exploring the potential of BNF becomes increasingly important. The symbiotic relationship between rhizobia and legume crops was considered the most important BNF system and estimated to contribute to 227 to 300 kg N/ha/year (Roughley et al., 1995; Herridge et al., 2008). N2 fixation by actinorhizal plants was estimated to be 240-350 kg N/ha/year (Wall, 2000).

Nitrogen fixation by plant-associated diazotrophs has been estimated to be 60 kg N/ha/year (Gupta et al., 2006; Reed et al., 2011). Moreover, the abundance of associated diazotrophs, such as Azotobacter species in the soil provides not only N (Din et al., 2019) but also phosphorus and plant growth regulators, which resulted in a yield increase of up to 40% in cereals and pulse crops (Yanni and El-Fattah, 1999; Choudhury and Kennedy, 2004; Kannan and Ponmurugan, 2010; Ritika and Dey, 2014; Wani et al., 2016; Velmourougane et al., 2019). Such beneficial effects have been harnessed ecologically in the engineering of Azotobacter species for fixing plant needed N, while reducing the reliance on synthetic N fertilizers for crop production in an environmentally friendly manner (Wani et al., 2016; Bageshwar et al., 2017; Ke et al., 2021).

Endophytic bacteria also contribute significantly to N input. Azoarcus is an endophytic N2-fixing diazotroph, and its action in roots of kallar grass increased hay yield up to 20–40 t/ha/year without N fertilizer application in saline-sodic, alkaline soils (Hurek and Reinhold-Hurek, 2003). Gluconoacetobacter diazotrophicus (Acetobacter diazotrophicus) is the main contributor in sugarcane and can fix up to 150 kg N/ha/year (Dobereiner et al., 1993; Muthukumarasamy et al., 2005). Many C-4 energy plants, such as Miscanthus sacchariflorus, Spartina pectinate, and Penisettum purpureum can harbor endophytic bacteria, which support the N requirement of these plants (Kirchhof et al., 1997). Gupta et al. (2012) reported that N derived from the air by endophytic bacteria for rice ranged from 9.2 to 47% depending on bacterial species. These results indicate that endophytic diazotrophs have a great potential to enhance the productivity of non-leguminous crops.

The aforementioned bacteria essentially act as the same as gut bacteria in mammals by living between plant cells as endophytes, close association with roots, or symbiotically and become indispensable for plant growth and development. Microorganisms are associated with all plant organs (Wei et al., 2017), but roots have the largest number and greatest range of microbes. Thus, a plant growing under field conditions is a community, not an individual. Such associations are collectively termed “phytomicrobiome.” The phytomicrobiome is integral for plant growth and function. Microbes play important roles in plant nutrient acquisition, biotic and abiotic stress management, physiology regulation through microbe-to-plant signals, and growth regulation via the production of phytohormones. The foregoing discussion documents the role of Co plays in N2 fixing rhizosphere bacteria. If we accept that coevolution exists between microbes and plants and the phytomicrobione in general, Co should be considered as an essential element to plants as it is required by symbiotic, endophytic, and associated bacteria.

Cobalt Coenzymes and Proteins

Cobalamin is a cofactor of adenosylcobalamin-dependent isomerases, ethanolamine ammonia-lyase, methylcobalamin-dependent methyltransferase, and ribonucleotide reductase in animals and bacteria (Table 1). Co is also a cofactor of non-corrin coenzymes or metalloproteins including aldehyde decarboxylase, bromoperoxidase-esterase, D-xylose isomerase, methionine aminopeptidase (MA), methylmalonyl-CoA carboxytransferase, nitrile hydratase (NHase), prolidase, and thiocyanate hydrolase (THase) in animals, bacteria, and yeasts. However, cobalamin-dependent enzymes or Co-proteins in plants remain obscure.

Cobalt Proteins in Plants

There are several lines of evidence suggesting that plants may have cobalamin-dependent enzymes and Co-containing proteins: (1) The ancestor of the chloroplast is cyanobacteria (Falcón et al., 2010), and Co is required by this group of bacteria. The speculation is that Co may be needed by plants. (2) Plants have been documented to utilize cobalamin produced by symbiotic, endophytic, and associated N2 fixing bacteria. Cobalamin concentrations of 37, 26, and 11 μg/100 g dry weight were detected in Hippophae rhammoides, Elymus, and Inula helenium, respectively (Nakos et al., 2017). There is a possibility that cobalamin-dependent enzymes may occur in plants. Poston (1977) reported the identification of leucine 2,3-aminomutase in extracts of bean seedlings. Its activity was stimulated by coenzyme B12 but inhibited by unknown factors. The inhibition was removed by the addition of B12, suggesting the presence of a cobalamin-dependent enzyme in higher plants. Subsequently, two coenzyme B12-dependent enzymes: leucine 2,3-aminomutase and methylmalonyl-CoA mutase were reported in potato tubers (Poston, 1978), but methylmalonyl-CoA mutase was found to be a phosphatase (Paizs et al., 2008). (3) Co is required by lower plants, which is to be discussed in the following section. (4) Plants can take up and transport cobalamin (Mozafar, 1994; Sato et al., 2004). A recent study using fluorescent analogs to follow the uptake and transport of cobalamin showed that Lepidium sativum can absorb cobalamin (Lawrence et al., 2018). Seed priming with cobalamin provided significant protection against the salt stress of common beans (Keshavarz and Moghadam, 2017). The incorporation of Co in plant tissue culture media significantly improves plantlet production (Bartolo and Macey, 1989). (5) Co as a metal cofactor of some additional enzymes and proteins are briefly discussed below (Table 1).

Carbonic anhydrase or carbonate dehydratase (CA, EC: 4.2.1.1) is a metalloenzyme catalyzing the conversion of CO2 to reversibly in many organisms including plants, particularly C4 and CAM plants. Eight different CA classes have been described as α-, β-, γ-, δ-, ζ-, η-, θ-, and a recently described ι-CA in microalgae. The metalloenzymes commonly use Zn2+ as a metal cofactor. However, Zn2+ in γ class can be replaced by Co2+ and Fe2+ in prokaryotes, fungi, algae, and plants, but in δ class is only can be replaced by Co2+ in marine phytoplankton (Jensen et al., 2020).

Carboxypeptidases (CPSs, EC: 3.4.16–3.4.18) are proteases hydrolyzing the C-terminal residues of peptides and proteins and release free amino acids individually. CPSs are divided into serine (EC: 3.4.16), metal (EC: 3.4.17), and cysteine (EC: 3.4.18) and occur in animals, bacteria, fungi, and plants. One Zn atom is essential to the catalytic activity of native carboxypeptidase A. Zn can be removed by dialysis at low pH or with chelating agents at neutral pH, which results in the inactivation of the enzyme. The re-addition of the metal restores the dual activities of carboxypeptidase toward peptides and esters. Co was found to be more active than Zn in the enzyme toward peptides and has nearly the same activity toward esters, indicating that Co in the active site is virtually identical to that of Zn in the native enzyme (Maret and Vallee, 1993).

Methionine aminopeptidase (MAP, EC 3.4.11.18) is widely documented in animals, bacteria, yeast, and plants. It is a Co-dependent enzyme responsible for the cleavage of the N-terminal methionine from newly translated polypeptide chains. Two classes of MAPs (MAP1 and MAP2) were reported in bacteria, and at least one MAP1 and one MAP2 occur in eukaryotes (Giglione and Meinnel, 2001). In Arabidopsis, there are four MAP1s (MAP1A, MAP1B, MAP1C, and MAP1D) and two MAP2s (MAP2A and MAP2B), along with two class 1 peptide deformylases (PDF1A and PDF1B). The plant MAP proteins show significant similarity to the eubacterial counterparts except for MAP1A and two MAP2s. It has been documented that the substrate specificity of PDFs and both organellar and cytosolic MAPs in plants are similar to that of their bacterial counterparts (Giglione et al., 2000). The MAP from Salmonella typhimurium is stimulated only by Co2+, not by Mg2+, Mn2+, or Zn2+ and is inhibited by metal ion chelator EDTA. E. coli MAP is a monomeric protein of 29 kDa consisting of 263 residues that possess two Co2+ ions in its active site (Permyakov, 2021).

Prolidase (PEPD, EC 3.4.13.9) hydrolyze peptide bonds of imidodipeptides with C-terminal proline or hydroxyproline, thus liberating proline. PEPD has been identified in fungi, plants (Kubota et al., 1977), archaea, and bacteria. The preferable substrate requires metal ions Mn2+, Zn2+, or Co2+.

Peroxidases are isoenzymes present in all organisms, which catalyze redox reactions that cleave peroxides; specifically, it breaks down hydrogen peroxide. The study of Han et al. (2008) found that Co2+ at a concentration below 0.1 mM increased horseradish peroxidase activity because Co2+ binds with some amino acids near or in the active site of the enzyme.

Urease is an enzyme occurring in selected archaea, algae, bacteria, fungi, and plants. It catalyzes the hydrolysis of urea into ammonia and carbamic acid. The active site of urease contains two Ni2+ atoms that are bridged by a carbamylated lysine residue and a water molecule (Carter et al., 2009). The study of Watanabe et al. (1994) reported that urease activity of cucumber leaves was markedly reduced when Ni concentration became <100 ng/L, but supplementing Co restored urase activity. Additionally, urease was also activated by both Co and manganese (Mn) through in vitro assay (Carter et al., 2009).

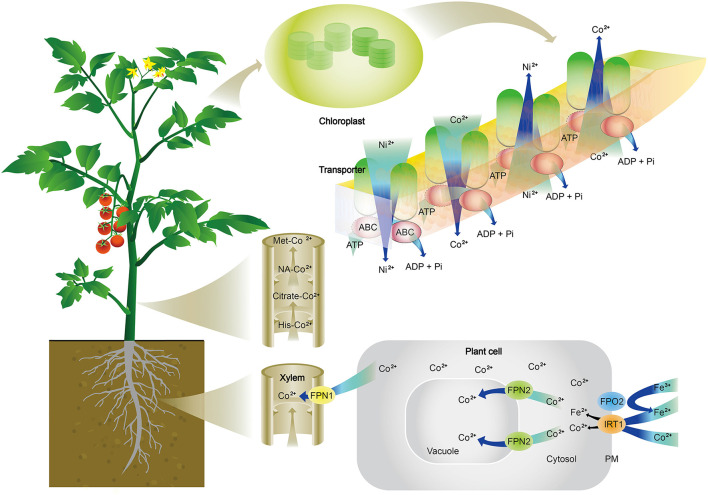

Cobalt transporters. Transporters specifically for Co have not been reported. The current understanding is that Co can be transported through Fe transporters (Figure 2). In Arabidopsis thaliana, Co is taken up from the soil into epidermal cells of roots by IRON-REGULATED TRANSPORTER 1 (IRT1), which is commonly known for absorption of Fe (Korshunova et al., 1999). Once Co is absorbed inside cells, Ferroportins, FPN1, and FPN2 are responsible for its further movement. IREG1/FPN1 is localized to the plasma membrane and expressed in the steel, indicating it is responsible for the loading of Fe to xylem, and FPN2 is situated the in vacuolar membrane and involved in buffering Fe concentration in the cytosol (Morrissey et al., 2009). Truncated FPN2 causes an elevated level of Co in shoots, while the loss of FPN1 abolishes Co accumulation in shoots. A double mutant of fpn1 fpn2 is unable to sequester Co in root vacuole and cannot transport Co to shoots. These results suggest that Co is likely absorbed and transported in the same way as Fe in plants (Figure 2). Additionally, an ATP-binding cassette (ABC) transporter from Arabidopsis has also been reported to transport Co, Ni, and Pb (Morel et al., 2009). Co movement in leaves is also associated with Ni, and Ni and Co movement in or out of chloroplasts are through an ABC transporter in the mediation of ionic homeostasis in the chloroplast of rice (Li et al., 2020).

Figure 2.

Schematic illustration of cobalt (Co2+) absorption, transport, and distribution in plants. Co2+ is absorbed from the soil into epidermal cells of roots by an iron transporter (IRT1). Once Co2+ is absorbed inside cells, Ferroportins (FPN1 and FPN2) are responsible for its further movement. FPN2 transports Co2+ into vacuoles, resulting in the sequestration of Co in root cells. FPN1 is to load Co2+ into the xylem. In the xylem, Co2+ is complexed with citrate, histidine (His), methionine (Met), or nicotianamine (NA) to be translocated to shoots. Co2+ is released in leaves and participate in metabolisms, which are often associated with nickel (Ni) and iron (Fe). It is shown here the Ni and Co movement in or out of chloroplasts through ATP-binding cassette (ABC) transporter in the mediation of ionic homeostasis in the chloroplast.

Cobalt Substitution of Other Metals

A characteristic of Co is its ability to substitute for other transition metals in a large number of enzymes. Maret and Vallee (1993) listed 37 Co-substituted metalloproteins, of which 24 are native to Zn, nine to copper (Cu), and four to Fe. These enzymes mainly occur in animals, bacteria, and yeast, while a few are in plants. Such a characteristic is closely related to the properties of Co with other metals. The ionic radius of Co2+ is 0.76 Å, which is similar to 0.74 Å of Zn2+, 0.69 Å for Cu2+, and 0.76 Å for Fe2+. Additionally, based on the available Protein Data Bank structures with Co2+, the study Khrustalev et al. (2019) found that Co2+ is commonly bound by cation traps. The traps are formed by relatively negatively charged regions of random coil between a β stand and α helix and between two β strands in which His, Asp, and Glu residues are situated. On the other hand, these sites are also occupied by other metals ions, such as Cu2+, Mg2+, Mn2+, and Zn2+, which play significant roles as catalysts. As a result, Co2+ could rather readily substitute for these ions in the active sites of enzymes. Additionally, based on the FIND-SITE-metal, a program for the prediction of the metal-binding site, the study of Brylinski and Skolnick (2011) found that Zn, due to a lower coordination number preference, is typically chelated with Cys and His, and His residues have a strong preference for Co, Cu, Fe, Ni, and Zn atoms. Thus, Co is able to replace Cu, Fe, Ni, and Zn in the active sites of enzymes. For example, Co addition alleviated Zn limitation in production of Thalassiosira weissflogii, which was due to Co substitution of Zn in the main isoform of carbonic anhydrase (Yee and Morel, 1996). Co substitution of Zn was also reported in two northeast Pacific isolates of diatoms Pseudo-nitzschia delicatissima UNC1205 and Thalassiosira spp. UNC1203 (Kellogg et al., 2020). Co2+ has been used as a spectroscopically active substitute for Zn2+ in enzymes (Bennett, 2010). Substitution of tetrahedral Zn2+ by higher-coordinate Co2+ often results in a catalytically active species, sometimes with catalytic properties perhaps unexpectedly similar to those of the native enzyme. In the vast majority of cases, no other transition ion than Co2+ provides a better substitute for Zn2+ (Maret and Vallee, 1993; Bennett, 2010). Due to these reasons, Co specific enzymes or proteins have not been conclusively identified. With the advance of omics, functions of a large number of gene sequences have not been assigned. Using the FIND-SITE-metal, a program developed for prediction of the metal-binding site, Brylinski and Skolnick (2011) predicted that about 10,953 putative metal-binding proteins in human proteome were bound with Ca, 10,534 bound with Mg, 8,681 with Zn, 1,863 with Fe, 1,246 with Mn, 652 with Co, 476 with Cu, and 403 with Ni. The predicted binding proteins with Co are greater than Cu and Ni in humans. Based on this assignment in the human proteome, it could be extremely difficult to believe that there are no Co-containing enzymes and proteins in plants.

Cobalt Is Essential for Lower Plants

Lower plants are commonly known as non-vascular plants because they do not have xylem and phloem vascular systems. Non-vascular plants are generally divided into bryophytes and algae.

Bryophytes

Bryophytes are seedless plants including Anthocerotophyta (hornworts), Bryophyta (mosses), and Marchantiophyta (liverworts) (Davies et al., 2020). This group of plants is able to absorb Co from air, soil, and water. In an early geochemical survey performed in Wisconsin and adjacent states and Missouri and Kentucky in the US, the study of Shacklette (1965) documented that the mean concentration of Co in 38 samples of liverworts and mosses was 32 mg/kg, and the concentration in the lower plants was closely related to the amount of the element in the soil, suggesting they act as a bioindicator of Co concentration in the environment (Baker, 1981). Mosses sampled from streams of the Idaho Cobalt Belt (U.S.) showed that Co concentrations in the plants almost perfectly correlated with those in the sediments, and the maximum content of Co (2,000 mg/kg) in moss ash corresponded to the maximum concentration of 320 mg/kg in the sediment (Erdman and Modreski, 1984). Mosses, such as Bryum argenteum and Hypnum cupressiforme were also considered to be bioindicators for monitoring heavy metal contamination in the air (Andić et al., 2015). Interestingly, the accumulation of Co did not cause any physiological damages to plants, but their growth was further enhanced.

The ability to take up Co could be related to the non-vascular nature and unidentified transporter. A radiolabel study showed that the total amount of 60Co accumulated in P. commune and D. scoparium under given conditions were 7.1 and 6.1 mg/kg, respectively. More than 95% of 60Co in D. scoparium was localized extracellular, while 70% of 60Co in P. commune was localized extracellular and about 20% localized intracellularly. These results showed that Co was largely adsorbed extracellularly, and there were unidentified transporters regulating the transport of Co into intracellular sites.

The enhanced growth could be in part attributed to the symbiotic relationship with cyanobacteria. Some bryophytes, primarily liverworts, and hornworts can form a symbiosis with cyanobacteria, such as Nostoc spp. After infection, Nostoc underwent some morphological and physiological changes by reducing growth rate and CO2 fixation but enhancing the fixation of N2 as well as releasing fixed N compounds to the plants. Cyanobacteria, like rhizobia, require cobalamin as a cofactor for nitrogenase complex to fix N2 (Böhme, 1998). Thus, cyanobacteria-bryophyte symbioses require Co.

Algae

Algae constitute a polyphyletic group ranging from unicellular microalgae, like chlorella and diatoms to multicellular forms, such as the giant kelp, seaweeds, and charophytes (Barsanti and Gualtieri, 2006). Co is essential to some marine algal species, including charophyte, diatoms, and dinoflagellates (Nagpal, 2004). Green alga Chlorella salina exhibited two phases of uptake of Co2+ (Garnham et al., 1992). The initial phase was rapid and independent of metabolism, and the second phase was slow and dependent on metabolism. Competition studies showed that the Co2+ uptake system was different from that for Mg2+, Mn2+, and Zn2+. The greatest amount of Co was associated with the cell wall. Co concentrations in the cytosol were 0.17 mM but 2.89 mM in the vacuole, suggesting that Co transport was well-controlled in C. salina. In the work of Czerpak et al. (1994), they studied the responses of a freshwater green alga Chlorella pyrenoidosa to different levels of Co and found that Co in a range from 5 to 50 mM significantly enhanced the growth of Chlorella pyrenoidosa, including 150–160 and 50–60% increase in fresh and dry weights, respectively. Such increase was related to the increase of chlorophylls a and b by 45–65%, water-soluble proteins by 19–20%, total carotenoids 55–65%, and monosaccharides content 55–60%, when compared with the culture devoid of Co. Although mechanisms behind the stimulating effects have not been elucidated, it is likely due to the biosynthesis of cobalamin that enhanced alga growth. Two cobalamin coenzyme 5′-deoxyadenosylcobalamin and methylcobalamin occurred in green alga C. vulgaris, and the addition of cobalamin significantly stimulated green alga growth (Watanabe et al., 1997). Moreover, C. vulgaris grown in Bold's basal medium supplemented with 2 and 2.5 μM CoCl2 produced 166.23 and 173.32 μg vitamin B12 per 100 g dry weight (Jalilian et al., 2019). Additionally, many algal species require different combinations of cobalamin, vitamin B1, and B7 (Croft et al., 2005) as they do not have pathways to synthesize cobalamin or may use alternative cobalamin-independent routes bypassing the need for the vitamin (Cruz-Lopez and Maske, 2016; Yao et al., 2018). As Co is a constituent of cobalamin, Co is required by those algae.

Some algal species, such as those in the genera Coccomyxa and Elliptochloris as well as diatoms form symbiotic relationships with cyanobacteria (Grube et al., 2017). Co is required for the growth of cyanobacteria, such as Anabaenza cylindrica Lemm (Holm-Hansen et al., 1954) and Prochlorococcus (Hawco et al., 2020) as they need it for N fixation in specialized cells called heterocysts. Thus, algal species symbiotic with cyanobacteria require Co for N-fixation.

Cobalt Improves the Growth of Higher Plants

Cobalt content in the crust of the earth ranges from 15 to 30 mg/kg (Roberts and Gunn, 2014). Co in soils is closely related to the weathering of parental minerals, such as cobaltite, smaltite, and erythrite (Bakkaus et al., 2005) as well as Co pollution (Mahey et al., 2020). Co in the surface soils of the world varies from 4.5 to 12 mg/kg with the highest level occurring in heavy loamy soils and the lowest in organic and light sandy soils (Kabata-Pendias and Mukherjee, 2007). However, Co in reference soil samples was found to differ from 5.5 to 29.9 mg/kg in the United States (U.S.) and 5.5 to 97 mg/kg in Chinese soils (Govindaraju, 1994). Pilon-Smits et al. (2009) suggested that soil Co concentrations generally range from 15 to 25 mg/kg.

Cobalt in Higher Plants

Plants absorb Co. Table 3 lists Co concentrations in over 140 non-hyperaccumulating species ranging from 0.04 to 274 mg/kg. Average concentrations of Co in grasses vary from 60 to 270 μg/kg and in clover differ from 100 to 570 μg/kg across Australia, Finland, Germany, Great Britain, Japan, New Zealand, Poland, Sweden, and the US (Kabata-Pendias and Mukherjee, 2007). Legumes absorb more Co than grasses. Plants that accumulate metals to a level 100-fold higher than those typically recorded in common plants are known as hyperaccumulators (Brooks, 1998).

Table 3.

The concentration of cobalt in higher plants with the exclusion of cobalt hyperaccumulators.

| Family | Species | Common name | Plant organ | Content (mg/kg) | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Acanthaceae | Lophostachys villosa Pohl | Lophostachys | Leaves | 31.00 | Van der Ent and Reeves, 2015 |

| Adiantaceae | Taenitis blechnoides (Willd.) Sw. | Ribbon fern | Leaves | 22.00 | Van der Ent and Reeves, 2015 |

| Amaranthaceae | Aerva lanata (L.) Juss. | Gorakhdi | Whole plants | 12.70 | Rajakaruna and Bohm, 2002 |

| Amaranthaceae | Pfaffia sarcophylla Pedersen | Pfaffia | Leaves | 13.00 | Van der Ent and Reeves, 2015 |

| Anacardiaceae | Gluta wallichii (Hook.f.) Ding Hou | Gluta | Leaves | 5.00 | Van der Ent and Reeves, 2015 |

| Anisophylleaceae | Anisophyllea disticha (Jack) Baill. | Mousedeer plant | Leaves | 4.00 | Van der Ent and Reeves, 2015 |

| Apocynaceae | Calotropis gigantea L.R.Br. | Yercum fiber | Whole plants | 0.84 | Rajakaruna and Bohm, 2002 |

| Apocynaceae | Carissa spinarum L. | Bush plum | Stems, leaves and flowers | 1.60 | Rajakaruna and Bohm, 2002 |

| Arecaceae | Phoenix farinifera Roxb. | Ceylon date palm | Whole plants | 0.04 | Rajakaruna and Bohm, 2002 |

| Aristolochiaceae | Thottea triserialis Ding Hou | Thottea | Leaves | 5.00 | Van der Ent and Reeves, 2015 |

| Asparagaceae | Asparagus zeylanicus Hook.f. | Asparagus | Whole plants | 0.90 | Rajakaruna and Bohm, 2002 |

| Asteraceae | Anthemis cretica L. | Mountain dog-daisy specie | Shoots | 8.90 | Koleli et al., 2015 |

| Asteraceae | Eupatorium odoratum L. | Siam weed | Whole plants | 0.50–3.10 | Rajakaruna and Bohm, 2002 |

| Asteraceae | Blumea balsamifera (L.) DC. | Bukadkad | Leaves | 2.00 | Van der Ent and Reeves, 2015 |

| Asteraceae | Vernonia holosericea Mart. ex DC. | Ironweed | Leaves | 21.00 | Van der Ent and Reeves, 2015 |

| Berberidaceae | Podophyllum peltatum L. | May-apple | Shoots | 0.60 | Koleli et al., 2015 |

| Betulaceae | Betula pubescens Ehrh. | Birch | Leaves | 0.36 | Reimann et al., 2001 |

| Bignoniaceae | Zeyheria digitalis (Vell.) Hoehne and Kuhlm | Zeyheria | Leaves | 2.00 | Van der Ent and Reeves, 2015 |

| Blechnaceae | Blechnum borneense C.Chr. | Hard fern | Leaves | 10.00 | Van der Ent and Reeves, 2015 |

| Boraginaceae | Anchusa granatensis Boiss. | Anchusa | Shoots | 0.90 | Koleli et al., 2015 |

| Boraginaceae | Onosma bracteosum Hausskn. and Bornm. | Onosma | Shoots | 6.60 | Koleli et al., 2015 |

| Brassicaceae | Alyssum minus (L.) Rothm. | Wild Alyssum | Shoots | 1.20 | Koleli et al., 2015 |

| Brassicaceae | Alyssum murale Waldst. and Kit. | Yellowtuft | Shoots | 7.70 | Koleli et al., 2015 |

| Brassicaceae | Aurinia saxatilis (L.) Desv. | Basket of gold | Roots | 37.00 | Homer, 1991 |

| Brassicaceae | Aurinia saxatilis (L.) Desv. | Basket of gold | Leaves | 117.00 | Homer, 1991 |

| Brassicaceae | Brassica juncea (L.) Czern | Brown-mustard | Stems, leaves, and flowers | 25.50 | Malik et al., 2000 |

| Brassicaceae | Thlaspi elegans Boiss. | Thlaspi | Shoots | 6.40 | Koleli et al., 2015 |

| Campanulaceae | Campanula rapunculoides L. | Creeping bellflower | Shoots | 0.70 | Koleli et al., 2015 |

| Caryophyllaceae | Dianthus arpadianus Ade and Born. | Dianthus | Shoots | 0.30 | Koleli et al., 2015 |

| Caryophyllaceae | Silene burchelli var. angustifolia Sond. | Gunpowder plant | Shoots | 250.00 | Baker et al., 1983 |

| Chrysobalanaceae | Parinari elmeri Merri. | Parinari | Leaves | 138.00 | Van der Ent and Reeves, 2015 |

| Clusiaceae | Mesua paniculate (L.) Jack | Chinese box | Leaves | 77.00 | Van der Ent and Reeves, 2015 |

| Compositae | Epaltes divaricate (L.) Cass. | Narrow-Leaf epaltes | Whole plants | 15.60 | Rajakaruna and Bohm, 2002 |

| Convolvulaceae | Evolvulus alsinoides L. | Little glory | Whole plants | 17.10 | Rajakaruna and Bohm, 2002 |

| Convolvulaceae | Jacquemontia sp. | Clustervine | Leaves | 16.00 | Van der Ent and Reeves, 2015 |

| Cornaceae | Nyssa aquatica L. | Water tupelo | Leaves | 156.00 | McLeod and Ciravolo, 2007 |

| Cornaceae | Nyssa aquatica L. | Water tupelo | Leaves | 24.50 | Wallace et al., 1982 |

| Cornaceae | Nyssa sylvatica Marsh. | Black gum | Mature foliage | 27.20 | Thomas, 1975 |

| Cornaceae | Nyssa sylvatica var. biflora (Walt.) Sarg. | Black gum | Leaves | 267.00 | McLeod and Ciravolo, 2007 |

| Cyperaceae | Fimbristylis falcata (Vahl) Kunth | Fimbristylis | Whole plants | 16.30 | Rajakaruna and Bohm, 2002 |

| Dennstaedtiaceae | Lindsaea gueriniana (Gaudich.) Desv. | Goldenbush | Leaves | 5.00 | Van der Ent and Reeves, 2015 |

| Dennstaedtiaceae | Tapeinidium acuminatum K.U. Kramer | Tapeinidium ferns | Leaves | 22.00 | Van der Ent and Reeves, 2015 |

| Droseraceae | Drosera montana A.St.-Hil. | Sundews | Leaves | 34.00 | Van der Ent and Reeves, 2015 |

| Ebenaceae | Diospyros lanceifolia Roxb. | Common Malayan ebony | Leaves | 2.00 | Van der Ent and Reeves, 2015 |

| Equisetaceae | Equisetum arvense L. | Bottlebrush | Shoots | 0.80 | Koleli et al., 2015 |

| Ericaceae | Empetrum nigrum L. | Crow-berry | Leaves | 0.05 | Reimann et al., 2001 |

| Ericaceae | Vaccinium myrtillus L. | Blue-berry | Leaves | 0.04 | Reimann et al., 2001 |

| Ericaceae | Vaccinium vitis-idaea L. | Cow-berry | Leaves | 0.04 | Reimann et al., 2001 |

| Euphorbiaceae | Croton bonplandianus Baill. | Bonpland's croton | Stems, leaves and flowers | 1.60 | Rajakaruna and Bohm, 2002 |

| Euphorbiaceae | Croton griffithii Hook.f. | Griffith's spurge | Leaves | 10.00 | Van der Ent and Reeves, 2015 |

| Euphorbiaceae | Drypetes caesia Airy Shaw | Drypetes | Leaves | 2.00 | Van der Ent and Reeves, 2015 |

| Euphorbiaceae | Euphorbia macrostegia Boiss. | Persian wood spurge | Shoots | 0.90 | Koleli et al., 2015 |

| Euphorbiaceae | Euphorbia rubicunda Blume | Chicken weed | Stems, leaves and flowers | 1.30 | Rajakaruna and Bohm, 2002 |

| Euphorbiaceae | Euphorbia selloi (Klotzsch and Garcke) Boiss. | Spurge | Leaves | 72.00 | Van der Ent and Reeves, 2015 |

| Euphorbiaceae | Phyllanthus sp. | Leaf-flower | Leaves | 85.00 | Van der Ent and Reeves, 2015 |

| Fabaceae | Mimosa pudica L. | Mimosa plant | Leaves | 0.04 | Van Tran and Teherani, 1989 |

| Fabaceae | Dalbergia beccarii Prain | Beccari's dalbergia | Leaves | 4.00 | Van der Ent and Reeves, 2015 |

| Iridaceae | Gladiolus italicus Miller | Field gladiolus | Shoots | 1.50 | Koleli et al., 2015 |

| Iridaceae | Sisyrinchium luzula Klotzsch ex Klatt | Blue-eyed grass | Leaves | 11.00 | Van der Ent and Reeves, 2015 |

| Labiatae | Mentha piperita L. | Mint | Shoots | 0.04–0.17 | Ciotea et al., 2021 |

| Labiatae | Ocimum basilicum L. | Basil | Shoots | 0.11–0.16 | Ciotea et al., 2021 |

| Labiatae | Rosmarinus officinalis L. | Rosemary | Shoots | 0.07- 0.14 | Ciotea et al., 2021 |

| Lamiaceae | Clerodendrum infortunatum L. | Hill glory bower | Stems, leaves and flowers | 0.60 | Rajakaruna and Bohm, 2002 |

| Lamiaceae | Crotalaria biflora L. | Two-flower rattlebox | Stems, leaves and flowers | 15.90 | Rajakaruna and Bohm, 2002 |

| Lamiaceae | Geniosporum tenuiflorum (L.) Merr. | Holy basil | Whole plants | 10.80 | Rajakaruna and Bohm, 2002 |

| Lamiaceae | Leucas zeylanica (L.) R.Br. | Ceylon leucas | Whole plants | 3.30 | Rajakaruna and Bohm, 2002 |

| Lamiaceae | Leucas zeylanica (L.) R.Br. | Ceylon leucas | Whole plants | 9.40 | Rajakaruna and Bohm, 2002 |

| Lamiaceae | Ajuga reptans L. | Bugleweed | Shoots | 0.90 | Koleli et al., 2015 |

| Lamiaceae | Haumaniastrum katangense (S. Moore) Duvign. Plancke | Copper flower | Leaves | 260.00 | Morrison, 1979 |

| Lamiaceae | Sideritis trojana Bornm. | Sideritis | Shoots | 0.90 | Koleli et al., 2015 |

| Lamiaceae | Thymus pulvinatus Celak | Common thyme | Shoots | 0.20 | Koleli et al., 2015 |

| Lamiaceae | Hypenia macrantha (A.St.-Hil. ex Benth.) Harley | Hypenia | Leaves | 10.00 | Van der Ent and Reeves, 2015 |

| Lamiaceae | Lippia aff. geminata | Lippia | Leaves | 11.00 | Van der Ent and Reeves, 2015 |

| Lamiaceae | Lippia sp. | Lippia | Leaves | 14.00 | Van der Ent and Reeves, 2015 |

| Leguminoseae | Tephrosia purpurea (L.) Pers. | Wild indigo | Stems, leaves and flowers | 5.20 | Rajakaruna and Bohm, 2002 |

| Leguminoseae | Baptisia australis (L.) R. Br. ex Ait. f. | Blue false indigo | Shoots | 0.50 | Koleli et al., 2015 |

| Leguminoseae | Vicia cassubica L. | Vicia | Shoots | 5.50 | Koleli et al., 2015 |

| Liliaceae | Allium cepa L. | Onion | Shoots | 3.50 | Koleli et al., 2015 |

| Liliaceae | Asphodelus aestivus Brot. | Summer asphodel | Shoots | 0.80 | Koleli et al., 2015 |

| Loganiaceae | Norrisia sp. 1 | Norrisia | Leaves | 8.00 | Van der Ent and Reeves, 2015 |

| Malvaceae | Abutilon indicum (L.) Sweet | Abutilon | Stems, leaves and flowers | 0.80 | Rajakaruna and Bohm, 2002 |

| Malvaceae | Hibiscus rhodanthus Gürke ex Schinz | Dwarf red hibiscus | Leaves | 21.00–1,971.00 | Faucon et al., 2007 |

| Malvaceae | Sida acuta Burm.f | Wire weed | Whole plants | 0.30 | Rajakaruna and Bohm, 2002 |

| Malvaceae | Waltheria indica L. | Sleepy morning | Whole plants | 1.33 | Rajakaruna and Bohm, 2002 |

| Melastomataceae | Pterolepis sp. nov. | Pterolepis | Leaves | 11.00 | Van der Ent and Reeves, 2015 |

| Myrtaceae | Syzygium cf. pterophera | Syzygium | Leaves | 7.00 | Van der Ent and Reeves, 2015 |

| Myrtaceae | Syzygium clavatum (Korth.) Merr. and L.M.Perry | Syzygium | Leaves | 3.00 | Van der Ent and Reeves, 2015 |

| Phyllanthaceae | Actephila sp. nov. | Actephila | Leaves | 65.00 | Van der Ent et al., 2015 |

| Phyllanthaceae | Antidesma coriaceum Tul. | Antidesma | Leaves | 2.00 | Van der Ent et al., 2015 |

| Phyllanthaceae | Aporosa benthamiana Hook.f. | Aporosa | Leaves | 6.00 | Van der Ent et al., 2015 |

| Phyllanthaceae | Aporosa falcifera Hook.f. | Aporosa | Leaves | 18.00 | Van der Ent et al., 2015 |

| Phyllanthaceae | Aporosa lucida (Miq.) Airy Shaw | Aporosa | Leaves | 18.00 | Van der Ent et al., 2015 |

| Phyllanthaceae | Baccaurea lanceolata (Miq.) Müll.Arg. | Baccaurea | Leaves | 179.00 | Van der Ent et al., 2015 |

| Phyllanthaceae | Breynia coronata Hook.f. | Breynia | Leaves | 4.00 | Van der Ent et al., 2015 |

| Phyllanthaceae | Cleistanthus ellipticus Hook.f. | Cleistanthus | Leaves | 6.00 | Van der Ent et al., 2015 |

| Phyllanthaceae | Cleistanthus gracilis Hook.f. | Cleistanthus | Leaves | 10 | Van der Ent et al., 2015 |

| Phyllanthaceae | Cleistanthus myrianthus (Hassk.) Kurz | Cleistanthus | Leaves | 2.00 | Van der Ent et al., 2015 |

| Phyllanthaceae | Cleistanthus gracilis Hook.f. | Cleistanthus | Leaves | 189.00 | Van der Ent and Reeves, 2015 |

| Phyllanthaceae | Glochidion angulatum C.B.Rob. | Glochidion | Leaves | 23.00 | Van der Ent et al., 2015 |

| Phyllanthaceae | Glochidion arborescens Blume | Glochidion | Leaves | 272.00 | Van der Ent et al., 2015 |

| Phyllanthaceae | Glochidion borneense (Müll.Arg.) Boerl. | Glochidion | Leaves | 21.00 | Van der Ent et al., 2015 |

| Phyllanthaceae | Glochidion brunneum Hook.f. | Glochidion | Leaves | 38.00 | Van der Ent et al., 2015 |

| Phyllanthaceae | Glochidion calospermum Airy Shaw | Glochidion | Leaves | 13.00 | Van der Ent et al., 2015 |

| Phyllanthaceae | Glochidion cf. lanceisepalum | Glochidion | Leaves | 9.00 | Van der Ent and Reeves, 2015 |

| Phyllanthaceae | Glochidion lanceilimbum Merr. | Glochidion | Leaves | 13.00 | Van der Ent et al., 2015 |

| Phyllanthaceae | Glochidion littorale Blume | Glochidion | Leaves | 8.00 | Van der Ent et al., 2015 |

| Phyllanthaceae | Glochidi on lutescens Blume | Glochidion | Leaves | 2.00 | Van der Ent et al., 2015 |

| Phyllanthaceae | Glochidion mindorense C.B.Rob. | Glochidion | Leaves | 16.00 | Van der Ent and Reeves, 2015 |

| Phyllanthaceae | Glochidion monostylum Airy Shaw | Glochidion | Leaves | 5.00 | Van der Ent et al., 2015 |

| Phyllanthaceae | Glochidion rubrum Blume | Glochidion | Leaves | 14.00 | Van der Ent et al., 2015 |

| Phyllanthaceae | Glochidion rubrum Blume | Glochidion | Leaves | 25.00 | Van der Ent and Reeves, 2015 |

| Phyllanthaceae | Glochidion singaporense Gage | Glochidion | Leaves | 120.00 | Van der Ent et al., 2015 |

| Phyllanthaceae | Glochidionobscurum (Roxb. ex Willd.) Blume | Glochidion | Leaves | 8.00 | Van der Ent et al., 2015 |

| Phyllanthaceae | Glochidionsuperbum Baill. ex Müll.Arg. | Great-leafed pin-flower Tree | Leaves | 22.00 | Van der Ent et al., 2015 |

| Phyllanthaceae | Phyllanthus amarus Schumach. and Thonn. | Sleeping plan | Leaves | 38.00 | Van der Ent et al., 2015 |

| Phyllanthaceae | Phyllanthus balgooyi Petra Hoffm. and A.J.M.Baker | Phyllanthus | Leaves | 26.00 | Van der Ent et al., 2015 |

| Phyllanthaceae | Phyllanthus balgooyi Petra Hoffm. and A.J.M.Baker | Phyllanthus | Leaves | 11.00 | Van der Ent and Reeves, 2015 |

| Phyllanthaceae | Phyllanthus kinabaluicus Airy Shaw | Phyllanthus | Leaves | 109.00 | Van der Ent et al., 2015 |

| Phyllanthaceae | Phyllanthus lamprophyllus Müll.Arg. | Phyllanthus | Leaves | 11.00 | Van der Ent et al., 2015 |

| Phyllanthaceae | Phyllanthus myrtifolius (Wight) Müll.Arg. | Mousetail plant | Stems, leaves and flowers | 0.50 | Van der Ent et al., 2015 |

| Phyllanthaceae | Phyllanthus pulcher Wall. ex Müll.Arg. | Tropical leaf-flower | Leaves | 31.00 | Van der Ent et al., 2015 |

| Phyllanthaceae | Phyllanthus reticulatus Poir. | Black-honey shrub | Leaves | 5.00 | Van der Ent et al., 2015 |

| Phyllanthaceae | Phyllanthus sp. | Leaf-flower | Stems, leaves and flowers | 2.40 | Van der Ent et al., 2015 |

| Phyllanthaceae | Phyllanthus sp. nov. “serinsim” | Phyllanthus | Leaves | 158.00 | Van der Ent et al., 2015 |

| Phyllanthaceae | Phyllanthus urinaria L. | Chamber bitter | Leaves | 12.00 | Van der Ent et al., 2015 |

| Pinaceae | Picea abies (L.) H.Karst. | Spruce | Needles | 0.07 | Reimann et al., 2001 |

| Pinaceae | Pinus sylvestris L. | Pine | Needles | 0.07 | Reimann et al., 2001 |

| Piperaceae | Piper officinarum C.DC. | Piper | Leaves | 13.00 | Van der Ent and Reeves, 2015 |

| Poaceae | Cymbopogan flexuosus (Nees ex Steud.) Will.Watson | Lemongrass | Whole plants | 0.30 | Rajakaruna and Bohm, 2002 |

| Poaceae | Imperata cylindrica (L.) Raeusch. | Alang grass | Leaves | 0.03 | Van Tran and Teherani, 1989 |

| Poaceae | Oryza sativa L. | Rice | Seeds | 0.04 | Van Tran and Teherani, 1989 |

| Poaceae | Hordeum murinum L. | Mouse Barley | Shoots | 0.80 | Koleli et al., 2015 |

| Poaceae | Aristida setacea Retz. | Broom grass | Whole plants | 14.60 | Rajakaruna and Bohm, 2002 |

| Polygonaceae | Rumex obtusifolius L. | Bitter dock | Shoots | 0.80 | Koleli et al., 2015 |

| Rubiaceae | Agrostemma cf. hameliifolium | Corncockle | Leaves | 16.00 | Van der Ent and Reeves, 2015 |

| Rubiaceae | Canthium puberulum Thwaites ex Hook.f. | Canthium | Stems, leaves and flowers | 0.12 | Rajakaruna and Bohm, 2002 |

| Rubiaceae | Canthium sp. | Kidney-fruit Canthium | Stems, leaves and flowers | 5.10 | Rajakaruna and Bohm, 2002 |

| Rubiaceae | Morinda tinctoria Roxb | Noni | Stems, leaves and flowers | 0.70 | Rajakaruna and Bohm, 2002 |

| Rubiaceae | Tarenna asiatica (L.) Kuntze ex K.Schum | Tharana | Stems, leaves and flowers | 1.10 | Rajakaruna and Bohm, 2002 |

| Rubiaceae | Urophyllum cf. macrophyllum | Urophyllum | Leaves | 1.00 | Van der Ent and Reeves, 2015 |

| Salicaceae | Salix spp. | Willow | Leaves | 1.76 | Reimann et al., 2001 |

| Solanaceae | Physalis minima L. | Cut-leaved ground-Cherry | Stems, leaves and flowers | 3.90 | Rajakaruna and Bohm, 2002 |

| Taxodiaceae | Taxodium distichum (L.) Rich. | Bald cypress | leaves | 4.60 | McLeod and Ciravolo, 2007 |

| Turneraceae | Piriqueta duarteana Urb. | Stripeseed | Leaves | 11.00 | Van der Ent and Reeves, 2015 |

| Turneraceae | Piriqueta sp. | Stripeseed | Leaves | 149.00 | Van der Ent and Reeves, 2015 |

| Turneraceae | Turnera melochioides A.St.-Hil. and Cambess. | Turnera | Leaves | 143.00 | Van der Ent and Reeves, 2015 |

| Umbelliferae | Conium maculatum L. | Poison hemlock | Shoots | 1.10 | Koleli et al., 2015 |

| Umbelliferae | Sanicula europaea L. | Sanicle, Wood sanicle | Shoots | 5.40 | Koleli et al., 2015 |

| Violaceae | Hybanthus enneaspermus F.Muell. | Blue spade flower | Whole plants | 17.00 | Rajakaruna and Bohm, 2002 |

As discussed above, Co specific transporters have not been reported, and a schematic diagram for Co absorption and translocation is presented in Figure 2. After absorption by roots, Co is either sequestrated in the vacuole of root cells or transported to shoots. Co that is being transported to shoots is chelated with ligands. Co has little affinity with phytochelatins (Chen et al., 1997; Cheng et al., 2005), thus the ligands are not likely Co-S bonds. The study by Collins et al. (2010) reported that Co2+ was complexed with carboxylic acids, which were transported from roots to shoots in wheat or tomato plants. Other ligands are citrate or malate as well as non-proteinogenic amino acids, such as histidine and nicotianamine (Figure 2). Co has low mobility within the leaf tissue and is largely distributed in the vascular system of tomato and wheat leaves (Collins et al., 2010). Co transport from roots to shoots is well-controlled. Using radiolabeled 57Co, Page and Feller (2005) studied Co transport in wheat plants and found that 80% of 57Co remained in roots after 4 days of culture, and 50% was retained in the roots after 50 days; during which, some 57Co moved to the apical part of the main roots, suggesting that the loading of Co to the xylem is well-controlled, probably by FPN1 in wheat plants. In another study, Collins et al. (2010) reported that tomato and wheat plants grown in a nutrient solution containing 2.94 mg/L Co had 4,423 μg/kg and 9,319 μg/kg of Co in roots, respectively; but shoot concentrations of Co were 1,581 μg/kg and 395 μg/kg, respectively. This means that 35.7% of Co absorbed by tomato and 4.2% of Co absorbed wheat plants were transported from roots to shoots. Furthermore, for the 1,581 μg/kg Co in tomato shoots, 846 μg/kg was in the stem, 492 μg/kg in old leaves, only 243 μg/kg in young leaves, indicating that only 5.5% of absorbed Co is transported to actively growing shoots of tomato plants. These transport patterns are like those of titanium (Lyu et al., 2017) which are strictly controlled by plants. These findings imply that plants probably have unidentified transporters specifically for the transport of Co. Due to its toxicity at higher concentrations, the rigorous control of the transport and distribution would ensure that only an appropriate amount of Co could be transported to actively growing shoots. On the other hand, why was more Co transported to dicot tomato shoots than monocot wheat shoots? One explanation could be that different plants have different ligands for complexing Co, and Co complexed by ligands in tomato was more mobile than that in wheat. Another explanation could be that tomato plants need more Co to fulfill some unidentified roles in shoots. Further research is needed to verify these propositions.

To maintain ionic homeostasis in shoots, particularly in chloroplasts, plants develop mechanisms to mediate Co in chloroplasts. An ARG1 transporter, belonging to the ATP-binding cassette, was identified in rice (Li et al., 2020), which was able to modulate the levels of Co and Ni in chloroplasts to prevent excessive Co and Ni from competing with metal cofactors in chlorophyll and metal-binding proteins in photosynthesis (Figure 2).

Plant Growth Improvement

Cobalt at low concentrations can also promote the growth of non-leguminous crops (Table 4). Co applied to a sandy soil at 1 mg/kg enhanced shoot and root dry weights of wheat by 33.7 and 35.8%, respectively compared with the control (Aery and Jagetiy, 2000), and the same Co rate applied to a sandy loam soil increased shoot and root dry weights of wheat by 27.9 and 39.6%, respectively, compared with the control. The yield and essential oil contents of parsley (Petroselinum crispum) increased considerably after the application of Co at 25 mg/kg soil (Helmy and Gad, 2002). Plant height, branch numbers, and fruit numbers as well as anthocyanin and flavonoids contents of Hibiscus sabdariffa significantly increased after application of Co at 20 and 40 mg/kg (Aziz et al., 2007). Application of 50, 100, 150, 200, and 250 mg/kg Co to corn plants showed that the root length, shoot height, and the number of cobs and seeds per plant increased when plants were applied with 50 mg/kg Co, but these parameters decreased with 100 mg/kg Co and above (Jaleel et al., 2009). Co applied at 10 mg/kg significantly enhanced the growth of two onion cultivars, bulb yields, bulb length, and bulb quality, such as nutrient and essential oil contents. Bulb diameter and bulb weights were much higher than the control treatment (Attia et al., 2014), but Co concentrations higher than 10 mg/kg significantly reduced the promotive effects.

Table 4.

Effects of cobalt application on plant performance.

| Species (common name) | Co application | Effects on plants | References |

|---|---|---|---|

| Actinidia chinensis Planch. cv. Hayward) (Kiwi) | Fruit was treated with 1 mM Co2+ solution | Inhibited ACC activity in ethylene biosynthesis | Hyodo and Fukasawa, 1985 |

| Adiantum raddianum C. Presl (Delta maidenhair fern) | Cut green (frond) was treated with 1 mM Co(NO3)2 solution | Prolonged vase life of frond from 3 to 8.2 days | Fujino and Reid, 1983 |

| Arachis hypogaea L. (Peanut) | Seeds were treated with Co(NO3)2 at 500 mg/kg seed and followed by two foliar sprays of cobalt nitrate at 500 mg/L before and after flowering | Significantly increased plant height, leaf number, pod yield, shelling percentage, harvest index, and total dry matter | Raj, 1987 |

| Arachis hypogaea L. (Peanut) | CoSO4 was mixed with soil at 0.21 kg/ha | Resulted in 10% higher kernel yield compared with control (without Co application) | Basu and Bhadoria, 2008 |

| Arachis hypogaea L. (Peanut) | Seedlings of groundnut at the third true leaf stage were irrigated once with CoSO4 at 2, 4, 6, and 8 mg/L, respectively | Increased plant height, number of branches and leaf number, leaf area index, root length, shoot and root biomass as well as pods numbers, pods weight, oil yield, total proteins, total carbohydrates, total soluble sugars, and total soluble solids | Gad, 2012a |

| Argyranthemum sp. (Argyranthemum) | Cut flowers preserved in a solution containing 2 mM Co | Increased flower longevity by more than 5 days compared with control (treated with distilled water) | Kazemi, 2012 |

| Avena sativa L. var. 'Condor' (Common oat) | Seeds were treated with 0.001% CoSO4 solution for 24 h, dried at room temperature for 3 days, then sown | Increased grain yields | Saric and Saciragic, 1969 |

| Beta vulgaris L. (Red beet) | CoSO4 was mixed with soil at 2.5, 5.0, 7.5, 10.0 and 12.5 mg/kg, respectively | Increased plant growth, root yield, mineral elements as well as protein, carbohydrate, vitamin C, sucrose, and glucose contents | Gad and Kandil, 2009 |

| Cajanus cajan (L.) Millsp. (Pigeon pea) | Seeds were treated with Co(NO3)2 at 500 mg/kg seed | Increased chlorophyll content, crop growth rate, relative growth rate, and net assimilation rate, resulting in increased plant height, number of branches, leaves, total dry matter, and yield | Raj, 1987 |

| Cariandrum sativum L. (Coriander) | Irrigated in the form of CoSO4 12.5 mg/L once | Increased coriander herb yield, mineral composition (except Fe), chemical constituents as well as essential oil components | Gad, 2012b |

| Cicer arietinum L. cv GG2 (Chickpea) | Chickpea seedlings at the three-leaf stage were fertigated with CoCl2 at 100 g/ha | Increased protein content and yield by 5.08 and 22.36%, respectively | Rod et al., 2019 |

| Cucumis sativus L. cv. (Cucumber) | Plants were treated with Co(NO3)2 solutions ranging from 1 to 500 ?M | Promoted hypocotyl elongation | Grover and Purves, 1976 |

| Cucurbita pepo cv. Eskandarany (summer squash) | Seeds in continuously aerated solutions of 0.25, 0.50, and 1.00 mg/L Co2+ for 48 h before sowing | Strongly increased plant growth, femaleness, and fruit yield compared with those of water- (control) or 0.5 mM AOA (aminooxyacetic acid)-soaked seed | Atta-Aly, 1998 |

| Allium cepa L.) cv. Giza 6 Mohassan (Onion) | Co mixed with sand and petmoss in 10.0 mg/kg soil | Significantly promote nutrients and essential oils content along with bulb length, bulb diameter and weight | Attia et al., 2014 |

| Dianthus caryophyllus L. cv. “Harlem” (Carnation) | Cut flowers were preserved in CoCl2 solutions at 50, 75, and 100 mg/L, respectively | Suppressed ethylene production and prolonged vase life | Jamali and Rahemi, 2011 |

| Gladiolus grandiflorus Hort. cv. Borrega Roja (Gladiolus) | Plants were treated with solution containing 0.3 mM CoCl2 | Increased stem and leaf N content, chlorophyll concentrations, leaf and stem dry weights, and improved stem absorption of water | Trejo-Téllez et al., 2014 |

| Glycine max (L.) Merr. (Soybean) | Plants were grown in nutrient solutions containing 1 and 5 μg/L cobaltous chloride, inoculated with rhizobia in the absence of nitrogen | No N deficiency symptoms, and increased dry weight by 52% compared with the control treatments | Ahmed and Evans, 1959 |

| Glycine max (L.) Merr. (Soybean) | Plants were grown in soil mixed with finely powdered (CoCl2) at the concentration of 50 mg/kg | Increased root and shoot length, leaf area, dry weight, yield, and yield components | Jayakumar et al., 2009 |

| Glycine max (L.) Merr. (Soybean) | Seeds were sown in soil mixed with finely powdered (CoCl2) at 50 mg/kg | Increased yield parameters, leaf area, shoot length, total dry weight as well as total phenol percentage | Vijayarengan et al., 2009 |

| Hevea brasiliensis (Willd. ex A.Juss.) Müll.Arg. (Rubber) | Plants were grown in Co free sand supplemented with 0.005 mg/kg Co | Increased plant height, stem diameter, and plant dry weight | Bolle-Jones and Mallikarjuneswara, 1957 |

| Hibiscus sabdariffa L. (Roselle) | Seedlings irrigated once with Co at concentrations of 20 and 40 mg/L | Increased plant height, branch numbers, and fruit numbers as well as anthocyanin and flavonoids contents | Aziz et al., 2007 |

| Ipomoea batatas L. (Sweet potato) | Seedlings were irrigated with CoSO4 once at concentrations of 5.0, 7.5, 10.0 mg/L | Increased growth and yield parameters, nutrient elements (except for Fe) and the chemical contents | Gad and Kandil, 2008 |

| Lilium spp. cv. Star Gazer Lily | Cut flowers were preserved in a solution containing 0.1 mM Co and 4% sucrose with a pH of 3.5 | Extended vase life | Mandujano-Piña et al., 2012 |

| Lilium spp. cv. Prato (Lily) | Cut flowers were treated with 2 mM CoCl2 | Increased vase life from seven to 9 days | Kazemi and Ameri, 2012 |

| Lilium spp. cv. Star Fighter (Lily) | Cut flowers were preserved in solutions containing 0.1, 0.2 mM Co and 4% sucrose with a pH of 3.5 | Extended the lifespan of flowers | Mandujano-Piña et al., 2012 |

| Lupinus angustifolius cv. Uniharvest (Blue lupin) | Supplemented 0.9 mg CoSO4.7H2O to each pot containing 6 kg soil | Increased plant growth and N content | Robson et al., 1979 |

| Lycopersicon esculantum Mill. (Tomato) | Ten seeds were sown in a pot containing 3 kg air-dried soil mixed with CoCl2 at 50 mg/kg, seedlings were thinned to 3 | Increased the content of phosphorus, potassium, copper, iron, manganese, and zinc in plants | Jayakumar et al., 2013 |

| Lycopersicon esculentum Mill. (Tomato) | Treated with simple solutions (1 mM CoCl2) plus wetting agent | Delayed gravitropic responses of treated plants | Wheeler and Salisbury, 1981 |

| Malus domestica Borkh. (Apple) | Apple fruit was immersed in a solution containing 1 mM CoCl2 for 1 min | Enhanced activity of protein inhibitor of polygalacturonase (PIPG) and provided better conservation of apple fruit consistency during storage | Bulantseva et al., 2001 |

| Mangifera indica L) cv. Langra (Mango) | Foliar spray with CoSO4 at 1,000 mg/L prior to flower bud differentiation in the first week of October | Reduced floral malformation by 65% and increased the fruit yield by 35% | Singh et al., 1994 |

| Matteuccia struthiopteris (L.) Todaro | Supplemented with various concentrations Co2+ ranging from 0.1 to 1 mM | Inhibited IAA-induced ethylene production in sporophytes | Tittle, 1987 |

| Phaseolus aureus Roxb. cv. T-44 (Mung bean) | Plants were treated with 50 μM Co in sand culture | Improved plant growth by increasing leaf, stem, and total dry weight compared with the controls | Tewari et al., 2002 |

| Phaseolus vulgaris L. Cv. “Burpees Stringless” (Common bean) | Two cycles of pre-sowing soaking and drying treatments by a 1 mg/L of Co(NO3)2 solution | Increased yield and N content over untreated and distilled water-soaked seeds by 48 and 150%, respectively | Mohandas, 1985 |

| Pisum sativum L. (Garden pea) | Seeds sowed in pot containing 10 kg soil mixed with CoSO4 at 8 mg/kg | Enhanced N2 fixation process, increased plant N content, and reduced inorganic and organic N fertilizer application by 75 and 33.3%, respectively | Gad, 2006 |

| Pisum sativum L. (garden pea) | Pots filled with 10 kg soil with Co at 2 mg/kg | Increased grain yield by 48.4% | Singh et al., 2012 |

| Polianthes tuberosa L. (Tuberose) | Flower stems were preserved in a solution containing 300 mg/L cobalt chloride | Extended the vase life and enhanced water uptake in cut tuberose flowers | Mehrafarin et al., 2021 |

| Pteridium aquilinum (L.) Kuhn var. latiusculum (Desv.) Underw. ex Heller (Western bracken fern) | Stems of cut green were preserved in solutions containing 0.1 to 1.0 mM Co | Inhibited IAA-induced ethylene production and prolonged vase life | Tittle, 1987 |

| Ricinus communis L. (Castor bean) | Plants treated with a 1 mM CoCl2 solution supplemented with a wetting agent | Delayed gravitropic responses of treated plants | Wheeler and Salisbury, 1981 |

| Rosa hybrida “Samantha” (Rose) | Cut flowers were preserved in solutions containing 0.5, 1.0, 1.5, and 2.0 mM CoCl2, respectively | Increased leaf diffusive resistance, inhibited xylem blockage, maintained water flow and uptake, and increased the vase life | Reddy, 1988 |

| Rosa hybrida “Samantha” (Rose) | Cut flowers were preserved in solutions containing 0.5, 1.0, 1.5, and 2.0 mM Co(NO3)2, respectively | Highly delayed or prevented the development of bent-neck and increased water uptake of cut flower | Murr et al., 1979 |

| Rosa spp.cv. Red one (Rose) | Cut flowers treated with 100 and 200 mg/L Co solutions | Inhibited vascular blockage in the stem of rose and maintained a high-water flow rate, leading to significantly water uptake by cut flowers | Aslmoshtaghi, 2014 |

| Triticum aestivum L. (Wheat) | Seeds were sowed in polythene-lined pots containing 4 kg of soil mixed with 1 mg/kg CoSO4 | Enhanced plant growth after 45 days of application | Aery and Jagetiy, 2000 |

| Vicia faba L. (Fava bean) | Seedlings at six-leaf stage were planted in pot containing soil mixed cobalt at 20 and 40 mg/kg, respectively | Improved photosynthesis and plant growth | Wang et al., 2015 |

| Vigna anguiculata subsp. alba (G. Don) Pasquet (Cowpea) | Seedlings were applied with Co at 4, 6, and 8 mg/kg | Enhanced plant growth and yield and induced nodulation | Gad and Hassan, 2013 |

| Xanthium strumarium L. (Cocklebur) | Plants treated with a 1 mM CoCl2 solution supplemented with a wetting agent | Delayed gravitropic responses of treated plants | Wheeler and Salisbury, 1981 |

| Zea mays L. (Maize) | Seeds sowed in pots containing 13 kg soil mixed with Co at 50 mg/kg | Increased seedling growth, photosynthetic pigments, and leaf chlorophyll contents | Jaleel et al., 2009 |