Abstract

Background:

Medicare hospital core process measures have improved over time, but little is known about how the distribution of performance across hospitals has changed, particularly among the lowest performing hospitals.

Methods:

We studied all United States hospitals reporting performance measure data on process measures for acute myocardial infarction, heart failure, and pneumonia to the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) from 2006–2011. We assessed changes in performance across hospital ranks, variability in the distribution of performance rates, and linear trends in the 10th percentile (lowest) of performance over time for both individual measures and a created composite measure for each condition.

Results:

More than 4,000 hospitals submitted measure data each year. There were marked improvements in hospital performance measures (median performance for composite measures: acute myocardial infarction: 96% to 99%, heart failure: 85% to 98%, pneumonia: 83% to 97%). A greater number of hospitals reached the 100% performance level over time for all individual and composite measures. For the composite measures, the 10th percentile significantly improved (acute myocardial infarction: 90% to 98%, P<0.0001 for trend; heart failure: 70% to 92%, P=0.0002; pneumonia: 71% to 92%, P=0.0003); the variation (90th percentile rate minus 10th percentile rate) decreased from 9% in 2006 to 2% in 2011 for acute myocardial infarction, 25% to 8% for heart failure, and 20% to 7% for pneumonia.

Conclusions:

From 2006–2011, not only did the median performance improve but the distribution of performance narrowed. Focus needs to shift away from processes measures to new measures of quality.

Keywords: Quality Improvement, Myocardial Infarction, Heart Failure, Pneumonia, Quality of Care

INTRODUCTION

In 2002, Medicare introduced publicly reported process quality measures to characterize care, facilitate quality improvement, and ultimately improve health outcomes.1 These measures were developed as part of the evolution of Medicare’s quality programs away from a focus on implicit review of individual cases to the evaluation of performance using explicit, nationally uniform criteria applied to populations of patients.2 Focusing on high-impact conditions, including heart failure (HF), acute myocardial infarction (AMI), and pneumonia (PN), these measures were initially provided back to individual hospitals and subsequently publicly reported. The Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) has continued to modify and publicly report these measures, and several national initiatives have focused on strategies to improve adherence.3–5

Initial studies and reports, particularly two in 2005, revealed marked gaps in performance with substantial variation across institutions.1,6–14 Subsequently, steady improvements in the performance on the process measures have been documented on Hospital Compare, the CMS website.15–20 However, while CMS publicly reports the average and top 10% performance rates, it does not provide information on the distribution of performance among the full range of the nation’s hospitals or trends in the variability in performance. The initial intent of the quality improvement program was to not only improve average performance but also decrease variation, i.e. to both shift the performance curve upward and narrow the difference between the high- and low- performing hospitals. Without information on how the distribution of performance across all the nation’s hospitals has changed over time, it is not possible to assess the extent to which performance by the “lagging” hospitals (the lowest 10%) has improved. Improvement across the spectrum of hospitals would be a strong indicator of the success of quality improvement efforts.

Accordingly, we describe national trends in the Medicare core process measures for AMI, HF, and PN from 2006 to 2011, characterizing the changes in the performance of all hospitals that reported. In addition to overall performance rates, we assessed performance variability among hospitals, with particular attention to the lowest performing hospitals. To do so, we examined the weighted distribution of the measure performance among hospitals by plotting the 10th, 50th, and 90th percentiles of performance, and examined the linear trend for the 10th percentile rate of the composite measure for the 3 conditions.

METHODS

Data Source

We used the process measure data from 2006 to 2011 from CMS Hospital Compare,15 a consumer-oriented website that presents information on how well hospitals provide recommended care. We included all the hospitals with the performance rate for each measure in each condition in our analysis.

Measures and Data Collection

Core process measures for AMI included aspirin at arrival, aspirin at discharge, angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitor (ACEI) or angiotensin receptor blocker (ARB) for left ventricular systolic dysfunction, smoking cessation advice/counseling, beta-blocker at discharge, and percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI) within 90 minutes of arrival. We excluded the fibrinolytic therapy measure because of small sample sizes in the later years. Core process measures for HF included discharge instructions, evaluation of left ventricular systolic function, ACEI or ARB for left ventricular systolic dysfunction, and smoking cessation advice/counseling. Core process measures for PN included initial emergency room blood culture performed before administration of the first hospital dose of antibiotics, pneumococcal vaccination, smoking cessation advice/counseling, most appropriate initial antibiotic(s), influenza vaccination, and initial antibiotic(s) within 6 hours after arrival. Notably, for the PN measure for initial antibiotic(s) within 6 hours after arrival, there was a change in the measure specification from providing antibiotics within 4 hours after arrival in 2006 to within 6 hours after arrival from 2007 thereafter. Also, these measures are constructed to include only patients without contraindication to the process or a documented reason for non-completion of the process.

We defined the composite measure for each condition as the total number of cases receiving the care processes for that condition over the total number of eligible cases for those processes. For example, there were 4 measures (M1, M2, M3, and M4) for HF; for a specific hospital, the eligible cases of these 4 measures were V1, V2, V3, and V4; the number of patients with the 4 therapies among the eligible cases in the 4 measures were N1, N2, N3, and N4; therefore the composite score for this hospital would be 100*(N1+N2+N3+N4)/(V1+V2+V3+V4). The data were publicly available and Institutional Review Board approval through Yale University was not required.

Hospital Characteristics

Hospital characteristics were derived from the American Hospital Association Survey in the corresponding year and linked with the performance measures data.21 We assessed the number of total staffed beds (<300, 300 to 600, >600), ownership type (government-owned, private not-for-profit, private for-profit), region (associated area, New England, Middle Atlantic, South Atlantic, East North Central, East South Central, West North Central, West South Central, Mountain, Pacific), teaching status (Council of Teaching Hospitals, teaching, non-teaching), cardiac facilities (catheterization laboratory but no open heart surgery – cardiac catheterization laboratory only, open heart surgery – coronary artery bypass grafting surgery, other), core-based statistical area (Division, Metropolitan, Micropolitan, Rural), and safety-net hospital status (no, yes).

Statistical Analysis

We examined hospital characteristics over time. We also examined the number of eligible cases each year for each individual measure and composite measure in each condition. We plotted the performance in each of these measures in the ranked order of hospitals (bottom to top) each year over time. We also examined the weighted distribution of the measure performance among hospitals (weighted by the number of eligible cases in each measure) each year for all individual measures and composites in each condition and plotted the 10th, 50th, and 90th percentiles of the distribution in each year. Linear trend was examined for the 10th percentile rate of the composite measure for the 3 conditions. A secondary analysis was done in which we restricted the analysis to the hospitals that appeared in all study years for each measure in each condition.

All analyses were conducted using SAS, version 9.3 (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC, USA) and Stata, version 12.0, (Stata Corp Inc., College Station, TX, USA).

RESULTS

Hospital Characteristics

Hospital characteristics among those with core process measures reported on Hospital Compare did not vary significantly over time (Table 1). The total number of participating hospitals ranged from 4194 to 4348. The majority had <300 beds. Ownership was largely non-for-profit and most were non-teaching. Hospitals were concentrated in the South Atlantic, East North Central, and West South Central regions. Approximately one-third had a capacity for coronary artery bypass grafting surgery and >10% had only cardiac catheterization laboratories. The core-based statistical area was largely metropolitan and approximately 30% of hospitals were safety-net hospitals.

Table 1.

Hospital Characteristics.

| Description | # (%) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2006 | 2007 | 2008 | 2009 | 2010 | 2011 | |

| Number of hospitals | 4194 (100) | 4251 (100) | 4231 (100) | 4330 (100) | 4348 (100) | 4227 (100) |

| Number of beds | ||||||

| < 300 | 3362 (80.2) | 3402 (80.0) | 3344 (79.0) | 3386 (78.2) | 3396 (78.1) | 3302 (78.1) |

| 300 to 600 | 624 (14.9) | 631 (14.8) | 628 (14.8) | 616 (14.2) | 620 (14.3) | 614 (14.5) |

| > 600 | 153 (3.7) | 157 (3.7) | 158 (3.7) | 169 (3.9) | 173 (4.0) | 171 (4.1) |

| Ownership | ||||||

| Government | 910 (21.7) | 940 (22.1) | 932 (22.0) | 914 (21.1) | 910 (20.9) | 848 (20.1) |

| Not-for-profit | 2539 (60.5) | 2567 (60.4) | 2540 (60.0) | 2580 (59.6) | 2587 (59.5) | 2548 (60.3) |

| For profit | 690 (16.5) | 683 (16.1) | 658 (15.6) | 677 (15.6) | 692 (15.9) | 691 (16.4) |

| Region | ||||||

| Associated area | 48 (1.1) | 45 (1.1) | 43 (1.0) | 43 (1.0) | 45 (1.0) | 48 (1.1) |

| New England | 180 (4.3) | 180 (4.2) | 180 (4.3) | 179 (4.1) | 180 (4.1) | 178 (4.2) |

| Middle Atlantic | 406 (9.7) | 398 (9.4) | 388 (9.2) | 381 (8.8) | 382 (8.8) | 378 (8.9) |

| South Atlantic | 650 (15.5) | 646 (15.2) | 635 (15.0) | 640 (14.8) | 637 (14.7) | 639 (15.1) |

| East North Central | 631 (15.1) | 651 (15.3) | 647 (15.3) | 656 (15.2) | 664 (15.3) | 658 (15.6) |

| East South Central | 372 (8.9) | 380 (8.9) | 374 (8.8) | 375 (8.7) | 371 (8.5) | 368 (8.7) |

| West North Central | 527 (12.6) | 546 (12.8) | 546 (12.9) | 575 (13.3) | 577 (13.3) | 527 (12.5) |

| West South Central | 564 (13.5) | 567 (13.3) | 559 (13.2) | 562 (13.0) | 558 (12.8) | 545 (12.9) |

| Mountain | 294 (7.0) | 306 (7.2) | 300 (7.1) | 305 (7.0) | 311 (7.2) | 297 (7.0) |

| Pacific | 467 (11.1) | 471 (11.1) | 458 (10.8) | 455 (10.5) | 464 (10.7) | 449 (10.6) |

| Teaching status | ||||||

| COTH | 276 (6.6) | 279 (6.6) | 271 (6.4) | 273 (6.3) | 274 (6.3) | 270 (6.4) |

| Teaching | 618 (14.7) | 507 (11.9) | 511 (12.1) | 498 (11.5) | 535 (12.3) | 530 (12.5) |

| Non-Teaching | 3245 (77.4) | 3404 (80.1) | 3348 (79.1) | 3400 (78.5) | 3380 (77.7) | 3287 (77.8) |

| Cardiac facility | ||||||

| CABG surgery | 1404 (33.5) | 1429 (33.6) | 1458 (34.5) | 1492 (34.5) | 1494 (34.4) | 1554 (36.8) |

| Catheterization lab | 551 (13.1) | 547 (12.9) | 575 (13.6) | 513 (11.9) | 504 (11.6) | 504 (11.9) |

| Other | 2184 (52.1) | 2214 (52.1) | 2097 (49.6) | 2166 (50.0) | 2191 (50.4) | 2029 (48.0) |

| Core-based statistical area | ||||||

| Division | 642 (15.3) | 629 (14.8) | 623 (14.7) | 618 (14.3) | 618 (14.2) | 609 (14.4) |

| Metro | 1846 (44.0) | 1861 (43.8) | 1831 (43.3) | 1850 (42.7) | 1850 (42.6) | 1832 (43.3) |

| Micro | 777 (18.5) | 788 (18.5) | 773 (18.3) | 781 (18.0) | 780 (17.9) | 776 (18.4) |

| Rural | 874 (20.8) | 912 (21.5) | 903 (21.3) | 922 (21.3) | 941 (21.6) | 870 (20.6) |

| Safety-net hospital* | ||||||

| No | 2887 (68.8) | 2931 (69.0) | 2887 (68.2) | 2941 (67.9) | 2951 (67.9) | 2917 (69.0) |

| Yes | 1251 (29.8) | 1259 (29.6) | 1243 (29.4) | 1230 (28.4) | 1238 (28.5) | 1170 (27.7) |

Defined as government hospitals or non-government hospitals with high Medicaid caseload.

COTH: Council of Teaching Hospitals, CABG: coronary artery bypass grafting

Note: The total % is not 100% due to missing data.

Patient Sample

The distribution of eligible cases each year for each measure per hospital is shown in eTable 1, Supplemental Digital Content 1. On average, volumes for all AMI measures increased over time. Mean volumes for all HF measures decreased over time except for the volume of HF patients eligible for smoking cessation advice/counseling, which increased. The mean volume of eligible patients for the PN measures of patients assessed and given pneumococcal vaccination, patients given smoking cessation advice/counseling, patients assessed, and given influenza vaccination increased from 2006 to 2011, while the others decreased over time.

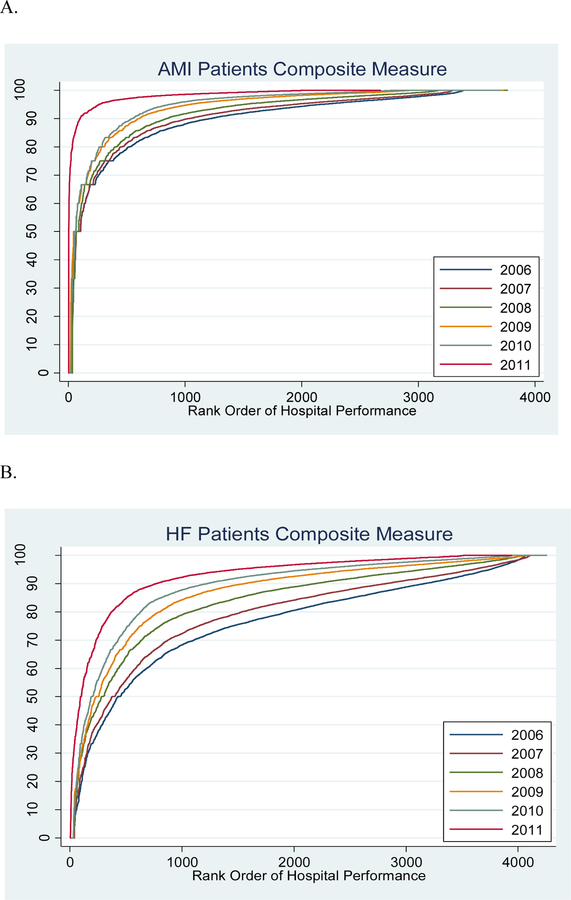

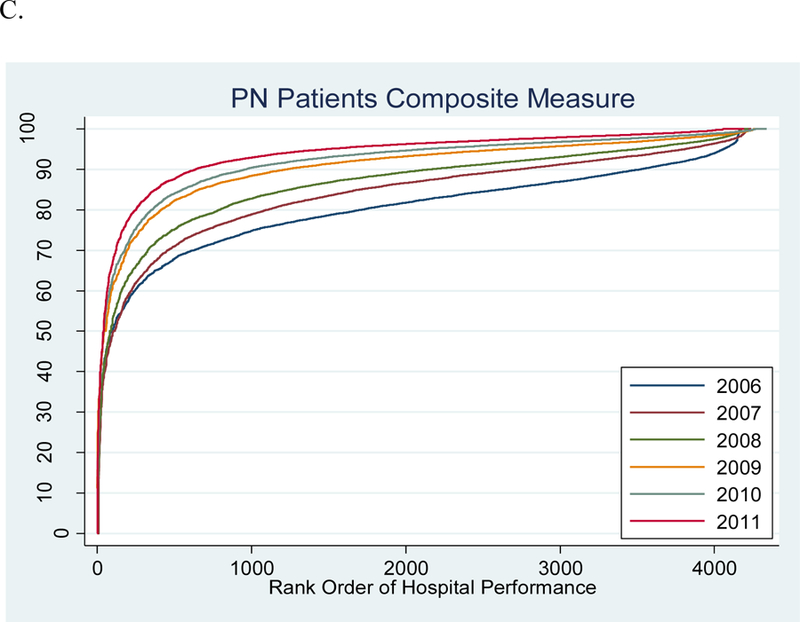

Performance by Hospital Rank

Hospital performance for all of the individual and composite measures for all 3 conditions improved over time. Figure 1 shows a greater number of hospitals reaching the highest performance level (i.e. more low-ranking hospitals at the 100% performance plateau in later years). For all of the measures, there was a progressive improvement in the distribution and a greater number at the 100% performance plateau over time. Ideal performance would be depicted by all hospitals at all rankings achieving top performance. By 2011, the performance improvement moved closest to ideal for the composite AMI measure, as well as individual measures such as AMI patients given aspirin at arrival, AMI patients given beta-blocker at discharge, and AMI, HF, and PN patients given smoking cessation advice/counseling (eFigure 1 in Supplemental Digital Content 2). For the composite HF and PN measures, and many of the individual measures for each condition, performance was not as high as for the AMI measures.

Figure 1. Trends in National Performance for the Acute Myocardial Infarction (AMI), Heart Failure (HF), and Pneumonia (PN) Composite Measures, 2006–2011.

On the x-axis is the rank order of hospitals by performance, and on the y-axis is performance level by percentage on the composite process measure for a given condition.

A. Acute Myocardial Infarction

B. Heart Failure

C. Pneumonia

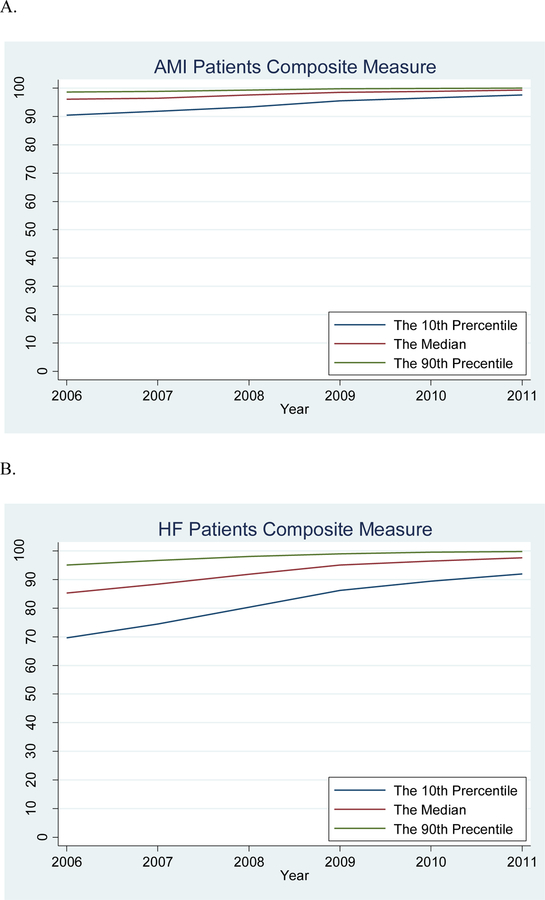

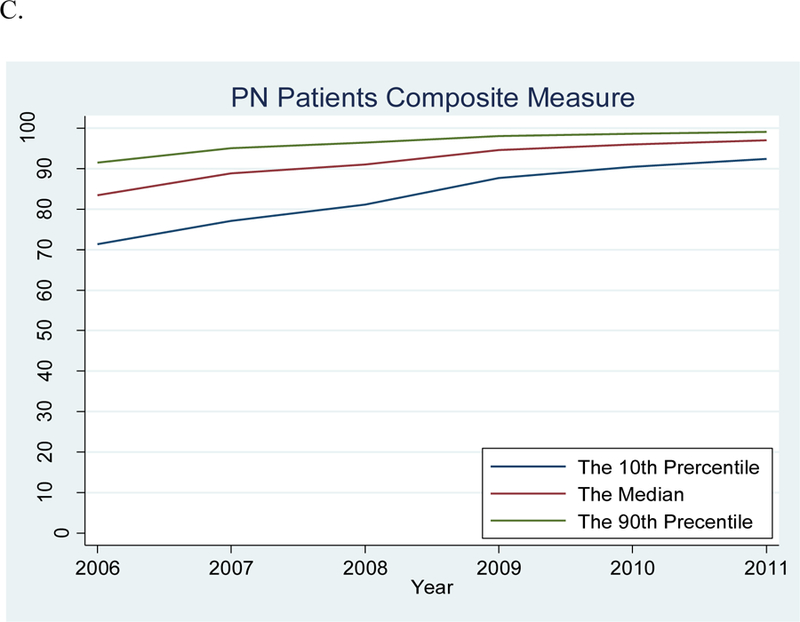

Change in Performance Variation over Time

Overall, there was a decreasing difference between the 90th and 10th percentile performance rates over time. For the composite measures, the variation decreased from a 9% to 2% absolute difference for AMI, a 25% to 8% difference for HF, and a 20% to 7% difference for PN in 2006 and 2011, respectively (eTable 2 in Supplemental Digital Content 3).

With respect to the distribution of performance, there were large improvements in the 10th percentile rate of performance for the individual and composite measures for all 3 conditions, which contributed to the improvements in the overall measures (Figure 2). For AMI, the scores for each measure, and therefore the composite measure, were uniformly high and overall the highest of the 3 conditions, with the median performance rate increasing from 96% in 2006 to 99% in 2011 for the composite measure (eFigure 2 in Supplemental Digital Content 2). Nevertheless, there was a significant improvement in the 10th percentile rate of performance for the composite AMI measure, from 90% to 98% (P<0.001). For HF and PN, the scores for each measure and the composite measure were also high, with an improvement in the median performance of the composite measure from 85% to 98% for HF and 83% to 97% for PN from 2006 to 2011 (Figure 2a). While the 90th percentile had scores above 90% over the entire time period, the 10th percentile rates for the HF (70% to 92%) and PN (71% to 92%) composite measures significantly improved (P<0.005 for both). Full performance information could be found in eTable2, Supplementary Data Content 3, which shows detailed information on the distribution of performance.

Figure 2. Trends for the 10th, 50th, and 90th Percentiles for the Acute Myocardial Infarction (AMI), Heart Failure (HF), and Pneumonia (PN) Composite Measures, 2006–2011.

There were significant improvements in the 10th percentile rates for all the composite measures from 2006 to 2011 (AMI: 90% to 98%, P<0.0001 for trend; HF: 70% to 92%, P=0.0002; PN: 71% to 92%, P=0.0003).

A. Acute Myocardial Infarction

B. Heart Failure

C. Pneumonia

These patterns in improvements were consistent with the secondary analysis that was limited to the hospitals appearing in all the years for each measure in each condition (see eTables 3, 4, and 5 in Supplemental Digital Content 4, and eFigures 3 and 4 in Supplemental Digital Content 5, which show similar improvements in the overall and distribution of performance in this sample).

DISCUSSION

There was substantial improvement among all hospitals, reflected by the selected performance measures for AMI, HF, and PN from 2006 to 2011. The improvement was not a result of a portion of the hospitals moving upward, but a shift in the entire distribution. While there was consistently high overall performance, the 10th percentile performance rates significantly improved, exceeding 80% for all composite process measures by 2011, with the ultimate consequence of markedly reduced hospital-level variability in performance. The decrease in variation and generally high performance represents a major achievement and raises questions about the utility of these measures as targets for further improvement and as a means of distinguishing higher- and lower-quality hospitals, and demonstrates the need for new areas of focus to improve the quality of care.

Our study is the first comprehensive analysis of how hospital performance on the national process of care measures for 3 major conditions has changed in recent times. A 2005 report on the Hospital Quality Alliance program demonstrated variation among hospitals in performance across all the measures.1 Another study of process quality indicators from 2002 to 2004 found improvement across all the measures over time, particularly among the low-performing hospitals.6 However, since 2005, while there was evidence of improvement for the average or median performance for single conditions,17–20 there has not been a comprehensive evaluation of the standardized measures focusing on the overall performance distribution of all US hospitals. Given the inherent relationship between means and the variation of percentages scores, with variation necessarily decreasing for the mean scores to increase, this is the first study, to our knowledge, to characterize the change in variation over time, particularly focusing on the lowest performing hospitals for all three major conditions and providing a comprehensive picture of quality improvement among all of the nation’s hospitals.

These results reflect a great success in improving quality even as the precise cause of this improvement is hard to identify. Our finding is similar to a study showing that the absolute improvement in quality of care was greater in states where the performance was low at baseline.13 Furthermore, during this time, there have been numerous national initiatives to improve performance.3–5,22 For AMI and HF in particular, there have been many government- and industry-sponsored efforts focused on improving hospital performance on the process measures, especially by the Quality Improvement Organization Program funded by CMS.22–26 Overall, given the continuing national focus on quality improvement beyond processes of care and the incentives associated with better performance, improvement in hospitals’ quality of care may continue. Nevertheless, there is a theoretical risk for an erosion in the uniformly high levels adherence to the specific processes in the core process measures due to the lack of pressure that collecting and reporting these measures provides.

The creation of the process measures and the improvement over time are the culmination of numerous national efforts over a period of intense attention to quality. Initial efforts at performance measurement were by the National Committee for Quality Assurance’s Health Plan Employer Data and Information Set;27 however, this was mainly focused on preventive and primary care services for defined populations of managed care plan enrollees. Measurement of hospital quality for high-impact conditions at a national level began with the Health Care Financing Administration’s (now CMS) Health Care Quality Improvement initiative,2 the first component of which was the Cooperative Cardiovascular Project.8,28 The Cooperative Cardiovascular Project marked a fundamental shift in the focus of performance measurement from individual physician treatment errors to institutional practice patterns, and sought to improve the overall quality of care and not just the performance of outliers. While CMS expanded its focus beyond AMI to other high-impact conditions, including HF and PN, several other stakeholders became engaged in quality measurement and improvement, including The Joint Commission,29 Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality,30 American Medical Association,31 and Veterans Health Administration.32 Other groups, such as the American College of Cardiology and the American Heart Association, also played key roles.33,34 In 2004, a consortium of organizations including the American Hospital Association, Federation of American Hospitals, American Association of Retired Persons, and National Quality Foundation, along with The Joint Commission and CMS, founded the Hospital Quality Alliance, under which hospitals nationwide reported data to CMS on indicators of the quality of care for AMI, congestive HF, and PN.1 Since then, CMS has continued to add to, modify, and publicly report these measures.3

Many of these process measures are now starting to be phased out because their performance is very high with limited room for improvement. While The Joint Commission is still collecting some of these measures, CMS has recently retired or suspended numerous process measures due to being either topped out or recommended for removal by the Measure Application Partnership.3,35–38 This retirement of measures is recognition of their success – that they have meaningfully changed practice to the degree that their utility is marginal, particularly in light of the resources needed to collect them; however, others may still find these modest differences meaningful and the measures to be useful. Nevertheless, moving forward, focus may be better to shift from these processes of care measures to outcomes measures and the construction of novel measures of the quality of care. Moreover, we need to also introduce composite measures, with new measures as components; report the distribution of performance and study outliers; and study the accuracy and reliability of the measures and the factors related to measure performance.

Our study has several limitations. First, we used the public Hospital Compare dataset that does not have patient-level identifiers, so we were unable to study patient characteristics. Furthermore, there have been changes to the measure specifications over time. Finally, we were unable to control for low-volume hospitals that chose to not report measure data under the 25-case rule. While this may have produced a lower number of hospitals reporting in later years, we conducted a secondary analysis of only hospitals that have reported measure data for each year and observed no major differences in our conclusions.

CONCLUSION

In our study, we document the success of process improvement among the nation’s hospitals in the CMS core process measures for AMI, HF, and PN from 2006 to 2011. We found marked improvements in the performance of hospitals. In particular, there were significant gains in the hospitals with the lowest levels of performance, resulting in a compression of the distribution and a greater uniformity of performance for these processes. While this should be considered an importance success, focus is needed on new areas for quality improvement to further elevate care for patients with these 3 conditions.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Financial Disclosure

Dr. Krumholz chairs a cardiac scientific advisory board for UnitedHealth, and is a recipient of research grants from Medtronic and from Johnson & Johnson, through Yale University, to develop methods of clinical trial data sharing; he also works under contract to the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services to develop and maintain performance measures that are used for public reporting. Dr. Masoudi has contracts with the American College of Cardiology, Oklahoma Foundation for Medical Quality (prior), and Health Services Advisory Group, Inc.

Funding Support

Dr. Krumholz is supported by grant No. U01 HL105270–05 (Center for Cardiovascular Outcomes Research at Yale University) from the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute. The funding source did not have a role in the design and conduct of the study; collection, management, analysis, and interpretation of the data; and preparation, review, or approval of the manuscript; and decision to submit the manuscript for publication.

Footnotes

Conflicts of Interest

The other authors report no potential conflicts of interest.

*All authors had access to the data and a role in writing the manuscript

Supplemental Digital Content

Supplemental Digital Content 1. Table that shows the distribution of eligible cases each year for each measure per hospital. Docx

Supplemental Digital Content 2. Figures that show the improvements in overall performance and the performance distribution for the individual measures. Docx

Supplemental Digital Content 3. Table that shows the full distribution of performance on each individual and composite measure for each condition, as well as the difference between the 90th and 10th percentile rates of performance. docx

Supplemental Digital Content 4. Tables that show the number of hospitals and the distribution of eligible cases and of performance for the secondary analysis that was limited to the hospitals appearing in all the years for each measure in each condition. Docx

Supplemental Digital Content 5. Figures that show the improvements in overall performance and the performance distribution for the secondary analysis that was limited to the hospitals appearing in all the years for each measure in each condition. docx

REFERENCES

- 1.Jha AK, Li Z, Orav EJ, Epstein AM. Care in U.S. hospitals--the Hospital Quality Alliance program. N Engl J Med 2005;353(3):265–274. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Jencks SF, Wilensky GR. The health care quality improvement initiative. A new approach to quality assurance in Medicare. JAMA 1992;268(7):900–903. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hospital Inpatient Quality Reporting (IQR) Program Overview 2014; https://qualitynet.org/dcs/ContentServer?c=Page&pagename=QnetPublic%2FPage%2FQnetTier2&cid=1138115987129. Accessed September 12, 2014.

- 4. Act DR. of 2005. PL 109e71. 2005.

- 5.Law P. Law 108–173. The Medicare Prescription Drug, Improvement, and Modernization Act of 2003 December 8, 2003. 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Williams SC, Schmaltz SP, Morton DJ, Koss RG, Loeb JM. Quality of care in U.S. hospitals as reflected by standardized measures, 2002–2004. N Engl J Med 2005;353(3):255–264. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Meehan TP, Fine MJ, Krumholz HM, et al. Quality of care, process, and outcomes in elderly patients with pneumonia. JAMA 1997;278(23):2080–2084. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ellerbeck EF, Jencks SF, Radford MJ, et al. Quality of care for Medicare patients with acute myocardial infarction. A four-state pilot study from the Cooperative Cardiovascular Project. JAMA 1995;273(19):1509–1514. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Krumholz HM, Wang Y, Parent EM, Mockalis J, Petrillo M, Radford MJ. Quality of care for elderly patients hospitalized with heart failure. Arch Intern Med 1997;157(19):2242–2247. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Nohria A, Chen YT, Morton DJ, Walsh R, Vlasses PH, Krumholz HM. Quality of care for patients hospitalized with heart failure at academic medical centers. Am Heart J 1999;137(6):1028–1034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Krumholz HM, Baker DW, Ashton CM, et al. Evaluating quality of care for patients with heart failure. Circulation 2000;101(12):E122–140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Luthi JC, McClellan WM, Fitzgerald D, et al. Variations among hospitals in the quality of care for heart failure. Eff Clin Pract 2000;3(2):69–77. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Jencks SF, Huff ED, Cuerdon T. Change in the quality of care delivered to Medicare beneficiaries, 1998–1999 to 2000–2001. JAMA 2003;289(3):305–312. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Landon BE, Normand SL, Lessler A, et al. Quality of care for the treatment of acute medical conditions in US hospitals. Arch Intern Med 2006;166(22):2511–2517. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.CMS. Hospital Compare 2013; http://www.cms.gov/Medicare/Quality-Initiatives-Patient-Assessment-Instruments/HospitalQualityInits/HospitalCompare.html. Accessed September 12, 2014.

- 16.CMS. Official Hospital Compare Data 2014; https://data.medicare.gov/data/hospital-compare. Accessed September 12, 2014.

- 17.Chassin MR, Loeb JM, Schmaltz SP, Wachter RM. Accountability measures--using measurement to promote quality improvement. N Engl J Med 2010;363(7):683–688. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kumbhani DJ, Fonarow GC, Cannon CP, et al. Predictors of adherence to performance measures in patients with acute myocardial infarction. Am J Med 2013;126(1):74 e71–79. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Blustein J, Borden WB, Valentine M. Hospital performance, the local economy, and the local workforce: findings from a US National Longitudinal Study. PLoS Med 2010;7(6):e1000297. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lee JS, Nsa W, Hausmann LM, et al. Quality of care for elderly patients hospitalized for pneumonia in the united states, 2006 to 2010. JAMA Intern Med 2014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.AHA Data and Directories. 2014; http://www.aha.org/research/rc/stat-studies/data-and-directories.shtml. Accessed September 12, 2014.

- 22.CMS. Quality Improvement Organizations 2013; http://www.cms.gov/Medicare/Quality-Initiatives-Patient-Assessment-Instruments/QualityImprovementOrgs/index.html?redirect=/QualityIMprovementOrgs/04_9thsow.asp-TopOfPage. Accessed September 12, 2014.

- 23.Fonarow GC, Abraham WT, Albert NM, et al. Organized Program to Initiate Lifesaving Treatment in Hospitalized Patients with Heart Failure (OPTIMIZE-HF): rationale and design. Am Heart J 2004;148(1):43–51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Fonarow GC, Committee ASA. The Acute Decompensated Heart Failure National Registry (ADHERE): opportunities to improve care of patients hospitalized with acute decompensated heart failure. Rev Cardiovasc Med 2003;4 Suppl 7:S21–30. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Fonarow GC, Yancy CW, Albert NM, et al. Improving the use of evidence-based heart failure therapies in the outpatient setting: The IMPROVE HF performance improvement registry. Am Heart J 2007;154(1):12–38. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hoekstra JW, Pollack CV Jr., Roe MT, et al. Improving the care of patients with non-ST-elevation acute coronary syndromes in the emergency department: the CRUSADE initiative. Acad Emerg Med 2002;9(11):1146–1155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Mainous AG 3rd, Talbert J. Assessing quality of care via HEDIS 3.0. Is there a better way? Arch Fam Med 1998;7(5):410–413. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Marciniak TA, Ellerbeck EF, Radford MJ, et al. Improving the quality of care for Medicare patients with acute myocardial infarction: results from the Cooperative Cardiovascular Project. JAMA 1998;279(17):1351–1357. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lee KY, Loeb JM, Nadzam DM, Hanold LS. Special Report: An Overview of the Joint Commission’s ORYX Initiative and Proposed Statistical Methods. Health Serv Outcome Res Meth 2000;1(1):63–73. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Larson JS, Muller A. Managing the quality of health care. J Health Hum Serv Admin 2002:261–280. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Costante PA. AMAP: toward standardized physician quality data. American Medical Accreditation Program. N Engl J Med 1999;96(10):47–48. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Sawin CT, Walder DJ, Bross DS, Pogach LM. Diabetes process and outcome measures in the Department of Veterans Affairs. Diabetes Care 2004;27 Suppl 2:B90–94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Krumholz HM, Anderson JL, Brooks NH, et al. ACC/AHA clinical performance measures for adults with ST-elevation and non-ST-elevation myocardial infarction: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Performance Measures (Writing Committee to Develop Performance Measures on ST-Elevation and Non-ST-Elevation Myocardial Infarction). Circulation 2006;113(5):732–761. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Spertus JA, Eagle KA, Krumholz HM, et al. American College of Cardiology and American Heart Association methodology for the selection and creation of performance measures for quantifying the quality of cardiovascular care. Circulation 2005;111(13):1703–1712. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.CMS. Medicare Program; Hospital Inpatient Prospective Payment Systems for Acute Care Hospitals and the Long-Term Care Hospital Prospective Payment System and Proposed Fiscal Year 2014 Rates; Quality Reporting Requirements for Specific Providers; Hospital Conditions of Participation 2014;:http://www.federalregister.gov/articles/2013/05/10/2013-10234/medicare-program-hospital-inpatient-prospective-payment-systems-for-acute-care-hospitals-and-the-h-411. Accessed September 12, 2014. [PubMed]

- 36.The Joint Commission. List of 2013 Accountability Measures 2014; http://www.jointcommission.org/accountability_measures.aspx. Accessed September 12, 2014.

- 37.CMS. Hospital Inpatient Quality Reporting (IQR) Program: Program Changes – Fiscal Year 2016 http://www.qualitynet.org/dcs/ContentServer?c=Page&pagename=QnetPublic%2FPage%2FQnetTier2&cid=11381159871292014. Accessed September 12, 2014.

- 38.The Joint Commission. National Hospital Inpatient Quality Reporting Measures: Specifications Manual http://www.jointcommission.org/specifications_manual_for_national_hospital_inpatient_quality_measures.aspx. Accessed September 12, 2014.

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.