Abstract

Background

It is critical to develop a reliable and cost-effective prognostic tool for colorectal cancer (CRC) stratification and treatment optimization. Tumor–stroma ratio (TSR) may be a promising indicator of poor prognosis in CRC patients. As a result, we conducted a systematic review on the predictive value of TSR in CRC.

Methods

This study was carried out according to Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) 2020 guideline. An electronic search was completed using commonly used databases PubMed, CENTRAL, Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials, and Google scholar till the last search up to May 30, 2021. STATA version 13 was used to analyze the data.

Results

A total of 13 studies [(12 for disease-free survival (DFS) and nine studies for overall survival (OS)] involving 4,857 patients met the inclusion criteria for the systematic review in the present study. In individuals with stage II CRC, stage III CRC, or mixed stage CRC, we observed a significantly higher pooled hazard ratio (HR) in those with a low TSR/greater stromal content (HR, 1.54; 95% CI: 1.20 to 1.88), (HR, 1.90; 95% CI: 1.35 to 2.45), and (HR, 1.70; 95% CI: 1.45 to 1.95), respectively, for predicting DFS. We found that a low TSR ratio had a statistically significant predictive relevance for stage II (HR, 1.43; 95% CI: 1.09 to 1.77) and mixed stages of CRC (HR, 1.65; 95% CI: 1.31 to 2.0) for outcome OS.

Conclusion

In patients with CRC, low TSR was found to be a prognostic factor for a worse prognosis (DFS and OS).

Keywords: tumor–stroma ratio, colorectal cancer, meta-analysis, stroma content, prognosis

Introduction

Colorectal cancer (CRC) is the third most common type of cancer worldwide and is associated with a high mortality rate (1). The TNM (T, size of the tumor and any spread into nearby tissue; N, the spread of cancer to nearby lymph nodes; and M, metastasis) provides prognostic information and aids in informed decision making in cancer patients, including patients with CRC. However, clinical outcomes in patients with colon cancer at the same TNM stage have been shown to vary dramatically. For example, approximately 5%–25% of stage II patients experienced a disease recurrence within 5 years. Additionally, patients with stage IIB colon cancer had a worse prognosis than those with stage IIIA colon cancer (2).

TNM classification is currently based on the anatomical evaluation. However, for predictive accuracy, further prognostic and/or predictive markers are required. It is critical to determine whether the early assessment of TSR and early stratification of treatment can enhance survival in selected patients. Additional biomarkers based on tumor cell features like shape, molecular pathways, genetic alterations, cell of origin and gene expression, and tumor cell immune response have been proposed. However, their disadvantage is the high cost associated with genetic and transcriptome data compared with conventional pathological examination using microscopy, which is quick, inexpensive, and reliable. Therefore, a pathological biomarker that is simple to assess is preferred. The tumor–stroma ratio (TSR) or a high percentage of stroma can be easily quantified on conventional H&E-stained paraffin sections at the invasive front of the tumor. TSR scoring is a reliable system that has the potential to be used in everyday practice. The procedure is highly replicable, with little intra-observer variation (3).

The TSR has recently been shown to be a promising outcome prediction tool in a variety of neoplasms, including breast cancer (4), colon cancer (5), hepatocellular carcinoma (6), and esophagus cell carcinoma (7). A study observed that TSR biopsy scoring in patients with esophageal adenocarcinoma was reproducible and concluded that the definitive TSR biopsy score was an independent prognostic factor for survival (8). The UNITED study (Uniform Noting for International Application of the Tumor-stroma Ratio as an Easy Diagnostic Tool) is an ongoing international multicentric prospective study to validate the TSR prognostic significance, with the goal of recruiting 1,500 patients with stage II and III colon carcinoma from 17 hospitals in 14 countries (9, 10). A recent study concluded that the use of e-learning to instruct pathologists and pathology residents seems to be an effective method. This study also showed that the consistency of scoring improved from the training to the test and demonstrated reproducibility of TSR scoring method (11).

Prognostic indicators could aid in the early identification of disease severity and stratification, as well as the planning of therapy strategies and the design of future research. The predictive value of TSR for digestive system malignancies was investigated in a meta-analysis by Zhang et al. (12). However, they were only able to include four articles on CRC in their analysis. There is a clear need for updated evidence on the association between TSR and prognosis in patients with CRC, given the publication of multiple papers following this study in recent years. The aim of present systematic review was to summarize the evidence supporting TSR as a predictor of disease-free survival (DFS) and overall survival (OS) in CRC patients.

Methods

This study was conducted following the guidelines for Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) 2020 guideline (13).

Eligibility Criteria

For analysis, both observational and interventional studies were considered. Studies were considered eligible if they met the following requirements: a) studies included patients with stage I or higher CRC, in association between TSR and OS or DFS; and b) studies were on human subjects with sufficient data to extract for predictive value of TSR in CRC patients and published in the English language. We excluded studies if a) TSR was provided for a number of cancers, but data for CRC could not be separated; b) studies were published as case reports, case series, reviews, or articles with no full text available, unpublished manuscripts, and conference abstracts; and c) studies lack information on TSR with CRC.

PICO Criteria

Participants

We included studies on CRC with stage I or higher.

Prognostic Tests

Studies provided TSR value as stroma rich (Low TSR) vs. stroma poor (High TSR). The prognostic factor could be examined as a categorical variable. The studies that reported and classified the cutoff value of stromal ratio of 50% or higher (high stromal content) were considered in the present systematic review. Studies that set the cutoff for the ratio of stroma less than 50% were excluded from the present systematic review to obtain the homogeneous results.

Comparator

Low TSR vs. High TSR.

Primary Outcomes

Primary outcomes assessed were DFS and OS. Survival was defined as survival till the last follow-up or censored at last follow-up.

OS was defined as the time between the date of primary surgery and the date of death from any cause or the date of last follow-up. DFS was defined as the time from date of primary surgery until date of death of any cause or the date of first loco-regional or distant recurrence.

Material and Methods

Study Design

Systematic review.

Ethical Clearance

Not required.

Search Strategy

This systematic literature search was performed following the PRISMA 2020 guidelines. An electronic search was completed using commonly used databases PubMed, CENTRAL, Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials, and Google scholar. The filter for the search was applied to the English language and human subjects. The last search was conducted up to May 30, 2021. The detailed search terms are given in Supplementary Text 1 . The reference lists of the identified studies and relevant reviews on the subject were also scanned for additional possible studies.

Risk of Bias Assessment

The methodological quality was evaluated by QUIPS (14, 15) modified for our review. In the “study participation” domain, the moderate risk of bias resulted from the inadequate description of study participants’ selection and inappropriate exclusion. In the “study attrition” domain, moderate or high risk of bias resulted from a low proportion of baseline population analyzed or inadequate reporting with unclear risk. In the “prognostic factor measurement” domain, moderate risk of bias was most often a result of inadequate reporting and no information for blinding.

Data Collection and Analysis

Two reviewers retrieved all eligible studies separately based on the inclusion criteria given above. The screening of the potentially eligible articles began with the title and abstract and then progressed to the full text. Any disagreements were worked out with the help of a third reviewer. The following data were extracted in the Excel file by two independent authors: details of participants, the country from the study reported, duration of the study, stage of the tumor, the cutoff value of the TSR, and outcome measurements.

Statistical Analysis

STATA software version 13 was used to analyze the data. A random-effects model was used to calculate the pooled hazard ratio (HR) with a 95% CI. The HR of more than 1 represents poor prognosis for OS or DFS. Pooled sensitivity and pooled specificity with 95% CI were also computed using a random-effects model. The sensitivity analysis was done to check if any study significantly dominates for computing pooled effect size. Publication bias was assessed by funnel plot, Begg’s test, and Egger’s test. The I 2 statistic was used to determine heterogeneity. This test determines whether the extent of the variation is explained beyond the chance or sampling error. I 2 of less than 50% is considered unimportant, while that of more than 50% is viewed as moderate-to-considerable heterogeneity.

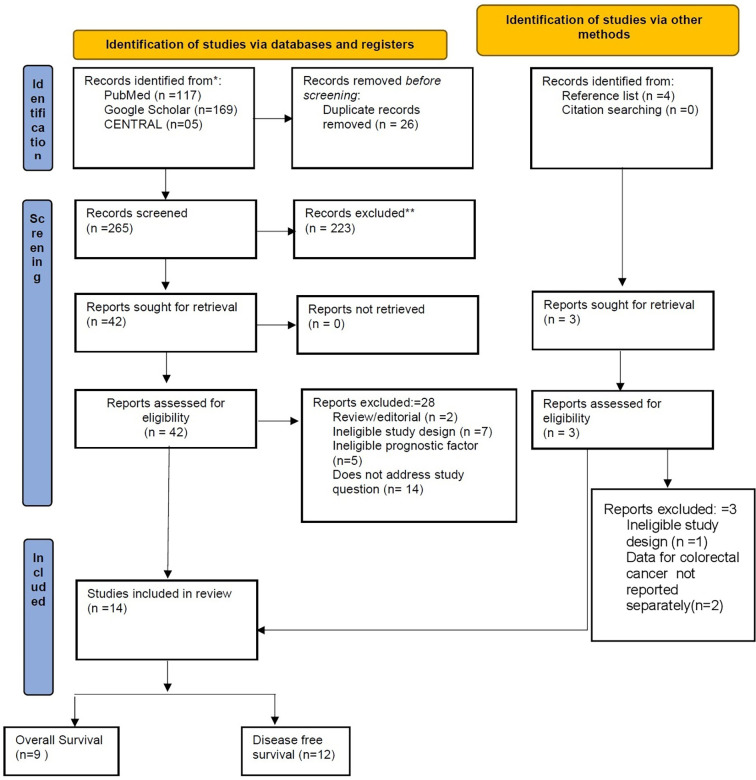

Study Characteristics

A total of 13 studies involving 4,857 patients met the inclusion criteria for the quantitative synthesis of the present study. A study flow diagram representing the selection process of relevant studies is shown in Figure 1 . The reason for the exclusion of the studies assessed for full text and not eligible for meta-analysis is given in Supplementary Table 1 . The median follow-up time varied from 2.5 to 16.1 years. The mean/median age of patients ranged from 62.2 to 75 years. All the studies we included had reported the data using a cutoff value of 0.5 (50%) or more for classifying the high stroma or low TSR value. One study was reported from China (16), one from Turkey (17), three from the United Kingdom (5, 18, 19), seven from the Netherlands (20–26), one from Poland (27), and two from Denmark (28). Five studies used the retrospective study design for their study ( Table 1 ). The percentage of stroma-rich cells in the included studies ranged from 12% to 65%. Two studies by the same author included the same patient group (29); therefore, the study with the higher sample size (21) was included. One study (25) did not report DFS analysis. Geessink et al. evaluated the tumor stroma ratio using both visual and automated approaches (20). Zengin et al. characterized rich-stroma as stroma more than 68% (17), while the remaining investigations used a threshold of 50%. Despite the aforementioned difficulties, sensitivity analysis revealed that no single study had a statistically significant effect on the aggregated results. For stage I CRC, only one study reported the data for association between TSR and DFS (24).

Figure 1.

Study flow diagram representing selection process of studies.

Table 1.

Study characteristics of studies included in the systematic review.

| Study no. | Author | Year | Country | Study design | Study period | Region | Cutoff | High stroma | Low stroma | CRC clinical stage | Stroma rich (%) | Median age | Follow-up | Survival | Tumor site | Treatment |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Yang L (16) | 2020 | China | Retrospective | 2009 to 2015 | Asia | 50% | 35 | 153 | II | 19% | 62.2 | 5.9 | DFS + OS | Colon | Chemotherapy |

| 2 | Eriksen AC (28) | 2018 | Denmark | Retrospective | 2002 | Europe | 50% | 169 | 404 | II | 29.50% | 73 | 6.9 | DFS + OS | Colon | Adjuvant chemotherapy |

| 3 | Huijbers A (5) | 2012 | UK | Retrospective | 2002 to 2004 | Europe | 50% | 83 | 285 | II | 22.50% | 75 | 4.3 | DFS + OS | Colon | Chemotherapy and Rofecoxib |

| 3a | Huijbers A (5) | 2012 | UK | Retrospective | 2002 To 2004 | Europe | 50% | 124 | 218 | III | 36.20% | 75 | 4.3 | DFS + OS | Colon | Chemotherapy and Rofecoxib |

| 4 | Mesker WE (21) | 2009 | The Netherlands | Retrospective | 1980 o 2001 | Europe | 50% | 34 | 101 | I–II | 27% | 68.2 | – | DFS + OS | Colon | Surgery |

| 5 | Roseweir AK (19) | 2020 | UK | Retrospective | 1997 to 2007 | Europe | 50% | NA | NA | II | 14.40% | 65 | 5 | DFS | Colorectal | Adjuvant chemotherapy |

| 5a | Roseweir AK (19) | 2020 | UK | Retrospective | 1997 to 2007 | Europe | 50% | NA | NA | III | 24.90% | 65 | 5 | DFS | Colorectal | Adjuvant chemotherapy |

| 6 | Geessink OGF (20) | 2019 | The Netherlands | Retrospective | 1996 to 2006 | Europe | 50% | 42 | 87 | I–III | 50.30% | 67 | 5.6 | DFS | Rectal | Radiotherapy and chemoradiotherapy |

| 7. | F. J. Vogelaar (25) | 2016 | The Netherlands | Prospective study | 2001 to 2007 | Europe | 50% | 124 | 208 | I–III | 37.3% | 56 | 12 | OF | Colorectal | Adjuvant chemotherapy |

| 8 | Park JH (18) | 2013 | UK | Retrospective | 1997 to 2008 | Europe | 50% | 67 | 179 | I–III | 24.40% | 65 | 5 | DFS | Colorectal | Adjuvant chemotherapy |

| 9 | Sandberg TP (22) | 2018 | The Netherlands | Retrospective cohort | 1991 to 2005 | Europe | 50% | 20 | 51 | I–III | 28.10% | 67.25 | 5 | DFS + OS | Colorectal | Surgery |

| 10 | Zunder SM (23) | 2018 | The Netherlands | Retrospective cohort | 2004 to 2007 | Europe | 50% | 339 | 824 | II–III | 12% | 5 | DFS + OS | Colon | Adjuvant chemotherapy | |

| 11 | Zengin and Benek (17) | 2020 | Turkey | Retrospective | 2004–2014 | Europe | 68% | 78 | 94 | III–IV | 45% | 76.27 | 8 | DFS + OS | Colon | Surgery and Chemotherapy |

| 12 | Zunder SM (20) | 2020 | The Netherlands | Retrospective | 1993–2003 | Europe | 50% | 36 | 138 | II | 20% | 64.4 | 15 | DFS + OS | Colon | Surgery plus chemotherapy |

| 13 | Dang H (24) | 2020 | The Netherlands | Retrospective case cohort | 2000–2014 | Europe | 50% | 63 | 156 | I | 40% | 70 | 3.5 | DFS | Colorectal | Neo-adjuvant radiotherapy |

CRC, colorectal cancer; DFS, disease-free survival; NA, Not Available; OS, overall survival.

Nine studies reported on the use of chemotherapy for treatment, with five (18, 19, 25, 28, 30) describing adjuvant chemotherapy, two (17, 26) describing surgery combined with chemotherapy, one describing chemotherapy and rofecoxib (5), and one describing only chemotherapy (16). One study (20) documented radiotherapy in conjunction with chemoradiotherapy (27), while another study (24) recommended neo-adjuvant radiotherapy in conjunction with radiotherapy as a treatment option. Only surgery was used as a treatment option in two studies (21, 22).

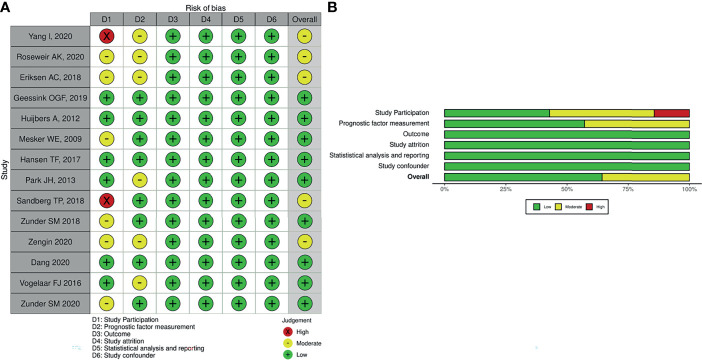

Risk of Bias in Included Studies

The majority of studies were of good quality, and some concern in the study participation domains was noted in the methodological quality assessment. The methodological quality of included studies is summarized in Figures 2A, B . Two studies had a high risk of bias in the “study participation domain”, as they did not mention the inclusion and exclusion criteria for the study participants. These studies (16, 22) had a high risk of bias, as they did not adequately account for study participant selection, and six studies were rated as having a moderate risk of bias in study participation due to incomplete information regarding inclusion criteria of study (17, 19, 21, 23, 26, 28). Overall, we judged five studies (16, 17, 19, 22, 28) to have a moderate risk of bias. This was commonly due to study participant selection.

Figure 2.

Methodological quality assessment of included studies in the present study. (A) Individual. (B) Overall.

Pooled Analysis

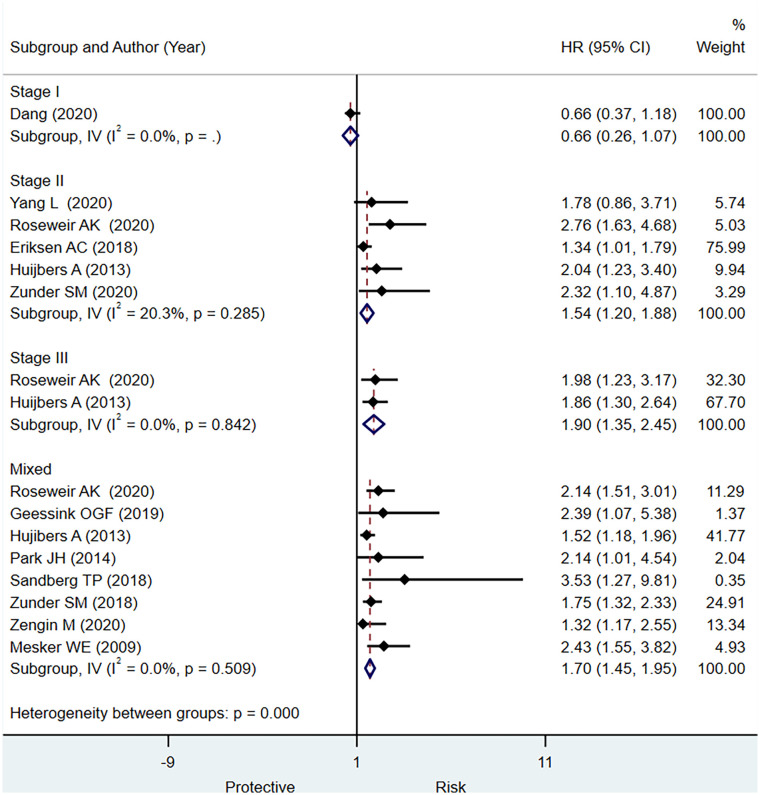

Disease-Free Survival

Twelve studies reported the data regarding prognostic significance of TSR for DFS. In terms of the HR, we observed a statistically significantly increased risk for DFS with higher stromal content in stage II CRC, stage III, and mixed CRC patients (HR, 1.54; 95% CI: 1.20 to 1.88), (HR, 1.90; 95% CI: 1.35 to 2.45), and (HR, 1.70; 95% CI: 1.45 to 1.95), respectively ( Figure 3 ). For stage I CRC, only one study did not report the statistically significant association between TSR and DFS. We did not notice a statistically significant increase in the HR for DFS in stage III CRC compared with stage II CRC (p = 0.27). These findings may be affected by type II error due to insufficient number of studies that reported data separately for stage III CRC, leading to underpowered test to examine this association. It is imperative to conduct well-designed studies to obtain precise evidence regarding the prognostic significance of TSR for predicting OS in different stages of CRC.

Figure 3.

Pooled hazard ratio for different stages of colorectal cancer (CRC) for predicting disease-free survival.

In terms of diagnostic test accuracy, we observed evidence of good prognostic value of low TSR for predicting worse outcome for DFS in stage II CRC with promising specificity (0.82; 95% CI: 0.76 to 0.87) but lower sensitivity (0.29; 95% CI: 0.22 to 0.37) ( Supplementary Figure 1 ). The discriminative power was moderate, as assessed by pooled summary area under the curve, 0.57, 95% CI: 0.53 to 0.61 ( Supplementary Figure 2 ). In case of studies including overall stages of CRC, we observed pooled sensitivity of 0.49, 95% CI: 0.30 to 0.69; a pooled specificity of 0.67, 95% CI: 0.51 to 0.79 ( Supplementary Figure 3 ); and summary area under the curve of 0.62, 95% CI: 0.58 to 0.67 ( Supplementary Figure 4 )

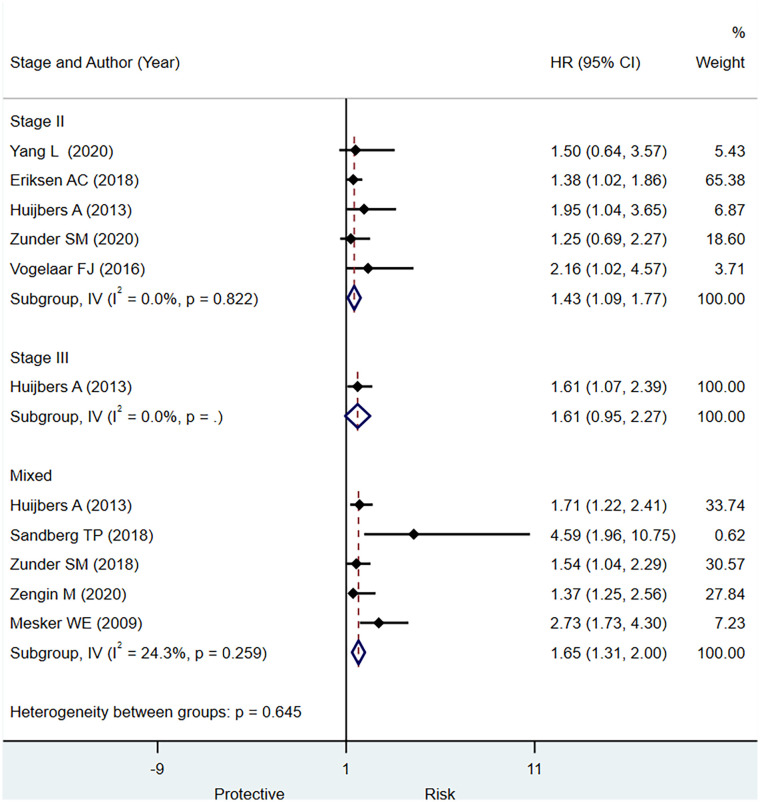

Overall Survival

In stage II CRC, a low TSR had a statistically significant prognostic value for OS (HR, 1.43; 95% CI: 1.09 to 1.77) based on five studies ( Figure 4 ). In stage III CRC, only one study published data indicating that a higher stromal content was associated with a worse prognosis (HR, 1.61; 95% CI: 1.07 to 2.39) ( Figure 4 ). Based on the pooled analysis including all stages of CRC, we observed that low TSR was significantly associated with OS (HR, 1.65; 95% CI: 1.31 to 2.00) ( Figure 4 ). Five studies had sufficient data to determine the prognostic significance of TSR for OS in terms of sensitivity and specificity. We observe evidence for the good prognostic value of low TSR for predicting OS including all stages of CRC specificity (0.78; 95% CI: 0.61 to 0.89) but low sensitivity (0.49; 95% CI: 0.34 to 0.65) ( Supplementary Figure 5 ) and summary area under the curve of 0.67, 95% CI: 0.63 to 0.71 ( Supplementary Figure 6 )

Figure 4.

Pooled hazard ratio for different stages of colorectal cancer (CRC) for predicting overall survival.

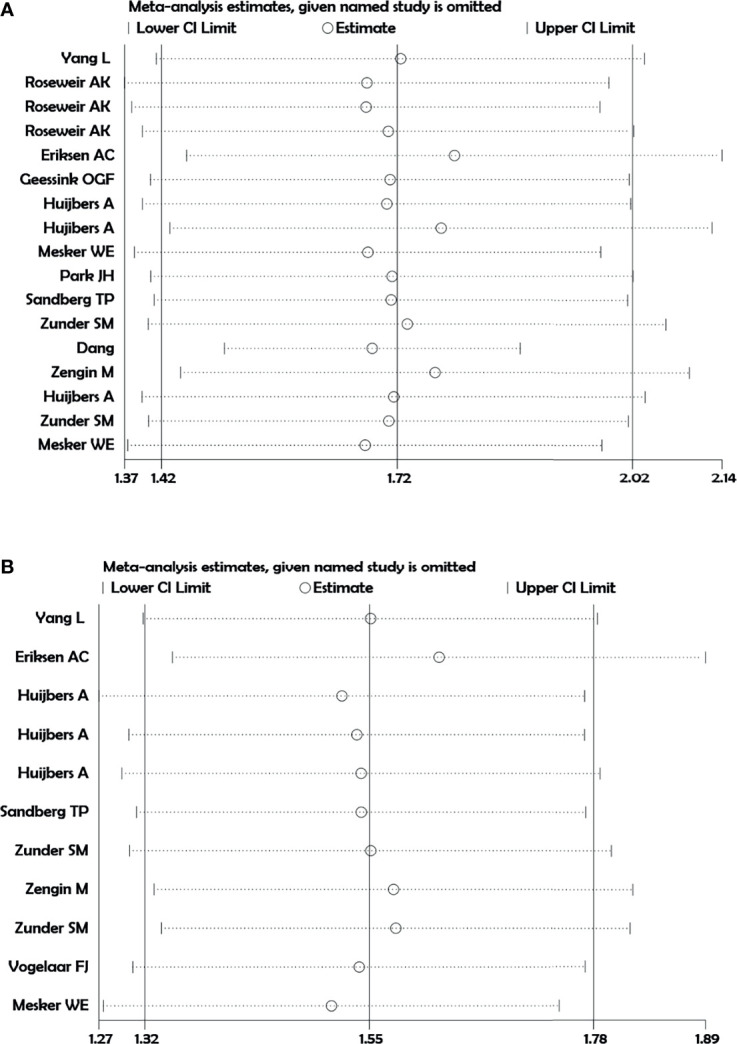

Sensitivity Analysis

We did not observe a point estimate of individual studies crossing the 95% CI of the pooled effect size of DFS and OS ( Figure 5 ). This finding suggests that pooled effect size is not dominated by any individual study, indicating the homogeneity and accuracy of study results.

Figure 5.

Sensitivity analysis. (A) Disease-free survival. (B) Overall survival.

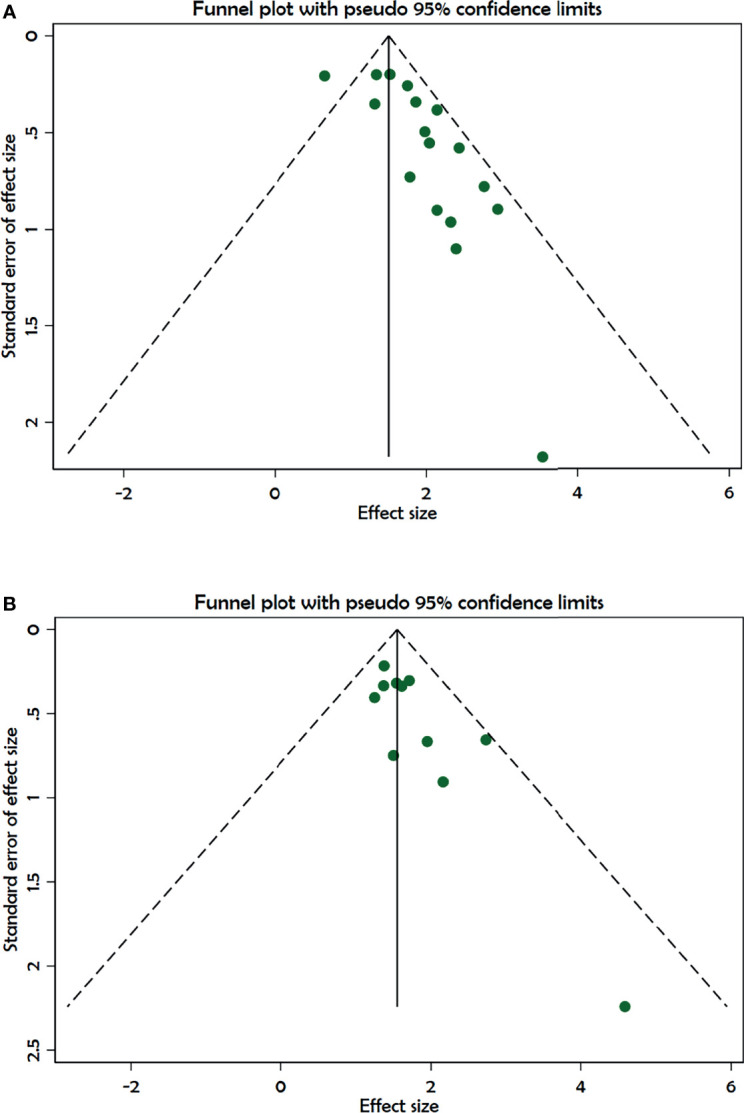

Publication Bias

We observed significant publication bias for outcome DFS shown in the funnel plot and Egger’s test (p < 0.001) and Begg’s test (p = 0.32), and also for the outcome OS in Egger’s test (p < 0.001) and Begg’s test (p = 0.07); see Figure 6 .

Figure 6.

Funnel plot showing publication bias. (A) Disease-free survival. (B) Overall survival.

Discussion

The present systematic review was conducted to summarize the evidence-based information regarding the prognostic significance of low TSR for predicting DFS and OS in patients with CRC.

There is a pressing need for an accurate, reliable, and effective approach for predicting the outcomes in patients with CRC, given the disease’s complexity in diagnosis and progression. In 2007, the carcinoma-stromal composition was discovered as the first predictive indicator for outcome in patients with CRC (29). It is simple to examine, cost-effective, and practical to use in a regular pathological laboratory. The most accepted and often utilized cutoff value for TSR is 50%, which has the highest predictive value for digestive system malignancies. A comprehensive review and meta-analysis of eight studies (four on colon or CRC) including 1,959 individuals demonstrated that a lower TSR was associated with a worse prognosis in patients with digestive system malignancies. The subgroup analysis of this meta-analysis (12) also revealed a poor prognosis for patients with low TSR in colon cancer (HR, 1.90; 95% CI: 1.51 to 2.39), which is consistent with the present meta-analysis findings; however, an association between low TSR and various stages of CRC was not presented in the same article.

In the present systematic review, we observed that a low TSR was associated with a poor prognosis in stage II CRC, and stage III CRC for OS as well as DFS. The pooled analysis revealed no evidence of substantial heterogeneity, supporting the study’s validity. Our systematic review noted that a high TSR ratio is strongly associated with a worse outcome for DFS and OS in stage III CRC as compared with stage II CRC. However, there were limited numbers of studies to draw precise conclusion for the differences in the strength of association among different stages of CRC. The study published by Yang et al. (16) consisting of low TSR proportion in 19% of study population of stage II CRC, did not observe the statistically significantly higher worse prognosis for DFS compared with high TSR subjects. On the other hand, a study published by Roseweir et al., which had a total of 14% low TSR in study population, noted statistically significantly worse outcome for DFS among low TSR subjects. The other three studies (5, 26, 28) have showed significant association of low TSR with worse prognosis for outcome DFS in stage II CRC. In the stage III CRC, two studies (5, 19) showed that low TSR is associated with worse outcome for DFS and OS.

In stage II colon cancer, four studies recruited subjects with malignancies at colon site. A study by Hujibers A et al. observed that low TSR is significantly associated with worse prognosis for DFS (HR 2.04; 95% CI: 1.23 to 3.4). The study reported by Eriksen et al. (28) and Zunder et al. (26) did not observe significant association of low TSR values with worse DFS in the stage II colon cancer subjects, whereas study by Yang et al. (16) did not observe the significant role of low TSR with worse prognosis in subjects with stage II colon cancer (HR, 1.78; 95% CI: 0.86 to 3.71). A study by Roseweir et al. (19), which recruited subjects with tumor location at colorectal site, noted that low TSR was significantly associated with worse prognosis for both stage II and stage II CRC (19). The study reported by Huijbers et al. (5) showed significant association of low TSR with both state II and stage III colon cancer patients.

We explored the effects of important clinical variables that could influence the prognostic significance of low TSR in patients with CRC, using meta-regression analysis. We observed the linear trend for different stages of CRC for higher prognostic efficiency of low TSR for predicting DFS ( Supplementary Figure 7 ) but not for OS ( Supplementary Figure 8 ). We cannot exclude the type II error in these findings, suggesting the power failure to detect the precise prognostic significance of low TSR value in the advance stage of CRC. Inclusion of the future studies may provide more precise information regarding the effect size of association of low TSR with different stages of CRC. Future studies should report the prognostic significance of low TSR according to the different stages of CRC to confirm these associations.

Majority of studies (9/13) used chemotherapy for the treatment. Among them, five studies (18, 19, 25, 28, 30) reported adjuvant chemotherapy. Two studies used only surgery as a treatment option (21, 22). Due to the limited number of studies in the homogeneous group, an analysis of the differences in the association of low TSR with type of therapy administered could not be conducted.

In order to investigate the relationship between clinicopathological characteristics and TSR, a meta-analysis was performed, and we found that low TSR was significantly associated with venous invasion (negative vs. positive OR: 0.72; 95% CI: 0.57 to 0.92, p = 0.009). However, other variables such as differentiation (moderate + well/or poor), lymph node status (positive/negative), and tumor invasion (T1 + T2/T3 + T4) were not significantly associated with TSR (31). Mesker et al. in their multivariable Cox regression analysis showed that carcinoma percentage (CP), as a derivative from the carcinoma–stroma ratio, remained an independent predictor when adjusted for either tumor stage or lymph-node status (p < 0.001 for OS). In comparison with low tumor proportion (TP) tumors, patients with high TP in colon cancer exhibited fewer tumor budding (p = 0.012), lymphovascular invasion (p = 0.049), and less harvested lymph nodes (p = 0.042) (32).

Low TSR value was substantially associated with poor survival, serious clinical stage, advanced depth of invasion, and positive lymph node metastasis, according to another meta-analysis that comprised 14 trials involving 4,238 solid tumor patients (33). A meta-analysis that included seven studies involving 1,779 patients with gastric adenocarcinoma also observed that low TSR ratio was substantially linked to 5-year rise in mortality (HR 2.19; 95% CI: 1.69 to 2.85) (34).

The underlying mechanisms of promoting the effect of low TSR on tumors are not still fully understood. According to a study, tumor-activated stroma induces epithelial cell interference, tumor invasion, and immune evasion of malignant cells (35). Tumorigenesis can be delayed or prevented by normal stroma, whereas abnormal stromal components can promote tumor growth (36). The extracellular matrix contents in the stroma promote the change in the microenvironment of the tumor that could increase the rate of tumor expansion and metastasis by overexpression of matrix metalloproteinases (37), which promotes tumorigenesis. On the other hand, the studies have shown that several growth factors and chemokines, e.g., tumor necrosis factor-alpha and nuclear factor-kB, are produced into the stroma, causing non-malignant cells to chemo-attract them. The clear-cut mechanism on the role of stromal cells for the progression of tumors has not been understood completely; however, our study showed that low TSR is associated with the progression of high-grade tumors and, thereby, poor prognosis (38).

Limitation

Although our systematic review showed a significant role of low TSR content in poor prognosis in CRC, it does have many limitations. Few studies included in the present study had a high risk of bias in the study selection. Information for blinding of baseline characteristics to pathologists has not been provided in the many studies. Therefore, it is necessary to develop a thorough approach for evaluation. The sample size in many studies was too low for a reliable conclusion. Subgroup data on the association of gender, tumor size, tumor invasion, and lymph node metastasis was not provided in the included studies to determine the subgroup effect of prognostic significance of low TSR between these subgroups. We were unable to analyze the heterogeneity caused by differences in TNM stages, tumor sides, and cancer treatments in depth; consequently, there is an obligatory necessity to conduct studies in homogenous groups to provide credible data.

Conclusion

The current systematic review showed that low TSR could be a prognostic factor for the prediction of worse prognosis (OS and DFS) in patients with CRC. Well-designed adequately prospective multicentric studies are required for validating the findings and for reliable conclusions on prognostic accuracy of low TSR in patients with CRC. Future research may include reporting data on the prognostic significance of TSR for each clinically relevant subgroup in order to achieve homogeneous results.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/ Supplementary Material . Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Author Contributions

JG and ZS conceived and designed the study. JG and ZD were involved in literature search and data collection. ZS and LM analyzed the data. JG and ZS wrote the paper. ZD and LM reviewed and edited the manuscript. All authors contributed to the article and approved the submitted version.

Funding

The current study is funded by Huzhou Science and Technology Plan (Grant number: 2020GYT09).

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher’s Note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Supplementary Material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fonc.2021.738080/full#supplementary-material

References

- 1. Torre LA, Bray F, Siegel RL, Ferlay J, Lortet-Tieulent J, Jemal A. Global Cancer Statistics, 2012. CA Cancer J Clin (2015) 65:87–108. doi: 10.3322/caac.21262 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Chu QD, Zhou M, Medeiros KL, Peddi P, Kavanaugh M, Wu X-C. Poor Survival in Stage IIB/C (T4N0) Compared to Stage IIIA (T1-2 N1, T1N2a) Colon Cancer Persists Even After Adjusting for Adequate Lymph Nodes Retrieved and Receipt of Adjuvant Chemotherapy. BMC Cancer (2016) 16:460. doi: 10.1186/s12885-016-2446-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. van Pelt GW, Kjær-Frifeldt S, van Krieken JHJM, Al Dieri R, Morreau H, Tollenaar RAEM, et al. Scoring the Tumor-Stroma Ratio in Colon Cancer: Procedure and Recommendations. Virchows Arch (2018) 473:405–12. doi: 10.1007/s00428-018-2408-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. de Kruijf EM, NesJGH v, van de Velde CJH, Putter H, Smit VTHBM, Liefers GJ, et al. Tumor-Stroma Ratio in the Primary Tumor Is a Prognostic Factor in Early Breast Cancer Patients, Especially in Triple-Negative Carcinoma Patients. Breast Cancer Res Treat (2011) 125:687–96. doi: 10.1007/s10549-010-0855-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Huijbers A, Tollenaar RAEM, v Pelt GW, Zeestraten ECM, Dutton S, McConkey CC, et al. The Proportion of Tumor-Stroma as a Strong Prognosticator for Stage II and III Colon Cancer Patients: Validation in the VICTOR Trial. Ann Oncol (2013) 24:179–85. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mds246 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Kairaluoma V, Kemi N, Pohjanen V-M, Saarnio J, Helminen O. Tumour Budding and Tumour-Stroma Ratio in Hepatocellular Carcinoma. Br J Cancer (2020) 123:38–45. doi: 10.1038/s41416-020-0847-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. He R, Li D, Liu B, Rao J, Meng H, Lin W, et al. The Prognostic Value of Tumor-Stromal Ratio Combined With TNM Staging System in Esophagus Squamous Cell Carcinoma. J Cancer (2021) 12:1105–14. doi: 10.7150/jca.50439 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. CourrechStaal EFW, Smit VTHBM, van Velthuysen M-LF, Spitzer-Naaykens JMJ, Wouters MWJM, Mesker WE, et al. Reproducibility and Validation of Tumour Stroma Ratio Scoring on Oesophageal Adenocarcinoma Biopsies. Eur J Cancer OxfEngl 1990 (2011) 47:375–82. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2010.09.043 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. UNITED – Watch Stroma . Available at: http://watchstroma.com/the-stroma-research/ (Accessed October 3, 2021).

- 10. Smit M, van Pelt G, Roodvoets A, Meershoek-Klein Kranenbarg E, Putter H, Tollenaar R, et al. Uniform Noting for International Application of the Tumor-Stroma Ratio as an Easy Diagnostic Tool: Protocol for a Multicenter Prospective Cohort Study. JMIR Res Protoc (2019) 8:e13464. doi: 10.2196/13464 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Smit MA, van Pelt GW, Dequeker EM, Al Dieri R, Tollenaar RA, van Krieken JHJ, et al. UNITED Group. E-Learning for Instruction and to Improve Reproducibility of Scoring Tumor-Stroma Ratio in Colon Carcinoma: Performance and Reproducibility Assessment in the UNITED Study. JMIR Form Res (2021) 5:e19408. doi: 10.2196/19408 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Zhang R, Song W, Wang K, Zou S. Tumor-Stroma Ratio(TSR) as a Potential Novel Predictor of Prognosis in Digestive System Cancers: A Meta-Analysis. Clin Chim Acta Int J Clin Chem (2017) 472:64–8. doi: 10.1016/j.cca.2017.07.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Page MJ, McKenzie JE, Bossuyt PM, Boutron I, Hoffmann TC, Mulrow CD, et al. The PRISMA 2020 Statement: An Updated Guideline for Reporting Systematic Reviews. BMJ (2021) 372:n71. doi: 10.1136/bmj.n71 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Hayden JA, van der Windt DA, Cartwright JL, Côté P, Bombardier C. Assessing Bias in Studies of Prognostic Factors. Ann Intern Med (2013) 158:280–6. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-158-4-201302190-00009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Grooten WJA, Tseli E, Äng BO, Boersma K, Stålnacke B-M, Gerdle B, et al. Elaborating on the Assessment of the Risk of Bias in Prognostic Studies in Pain Rehabilitation Using QUIPS—aspects of Interrater Agreement. Diagn Progn Res (2019) 3:5. doi: 10.1186/s41512-019-0050-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Yang L, Chen P, Zhang L, Wang L, Sun T, Zhou L, et al. Prognostic Value of Nucleotyping, DNA Ploidy and Stroma in High-Risk Stage II Colon Cancer. Br J Cancer (2020) 123:973–81. doi: 10.1038/s41416-020-0974-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Zengin M, Benek S. The Proportion of Tumour-Stroma in Metastatic Lymph Nodes is An Accurately Prognostic Indicator of Poor Survival for Advanced-Stage Colon Cancers. Pathol Oncol Res POR (2020) 26:2755–64. doi: 10.1007/s12253-020-00877-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Park JH, Richards CH, McMillan DC, Horgan PG, Roxburgh CSD. The Relationship Between Tumour Stroma Percentage, the Tumour Microenvironment and Survival in Patients With Primary Operable Colorectal Cancer. Ann Oncol (2014) 25:644–51. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdt593 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Roseweir AK, Park JH, Hoorn ST, Powell AG, Aherne S, Roxburgh CS, et al. Histological Phenotypic Subtypes Predict Recurrence Risk and Response to Adjuvant Chemotherapy in Patients With Stage III Colorectal Cancer. J Pathol Clin Res (2020) 6:283–96. doi: 10.1002/cjp2.171 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Geessink OGF, Baidoshvili A, Klaase JM, EhteshamiBejnordi B, Litjens GJS, van Pelt GW, et al. Computer Aided Quantification of Intratumoral Stroma Yields an Independent Prognosticator in Rectal Cancer. Cell Oncol Dordr (2019) 42:331–41. doi: 10.1007/s13402-019-00429-z [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Mesker WE, Liefers G-J, Junggeburt JMC, van Pelt GW, Alberici P, Kuppen PJK, et al. Presence of a High Amount of Stroma and Downregulation of SMAD4 Predict for Worse Survival for Stage I-II Colon Cancer Patients. Cell Oncol (2009) 31:169–78. doi: 10.3233/CLO-2009-0478 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Sandberg TP, Oosting J, van Pelt GW, Mesker WE, Tollenaar RAEM, Morreau H. Molecular Profiling of Colorectal Tumors Stratified by the Histological Tumor-Stroma Ratio - Increased Expression of Galectin-1 in Tumors With High Stromal Content. Oncotarget (2018) 9:31502–15. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.25845 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Zunder SM, van Pelt GW, Gelderblom HJ, Mancao C, Putter H, Tollenaar RA, et al. Predictive Potential of Tumour-Stroma Ratio on Benefit From Adjuvant Bevacizumab in High-Risk Stage II and Stage III Colon Cancer. Br J Cancer (2018) 119:164–9. doi: 10.1038/s41416-018-0083-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Dang H, van Pelt GW, Haasnoot KJ, Backes Y, Elias SG, Seerden TC, et al. Tumour-Stroma Ratio has Poor Prognostic Value in non-Pedunculated T1 Colorectal Cancer: A Multi-Centre Case-Cohort Study. United Eur Gastroenterol J (2020) 9:478–85. doi: 10.1177/2050640620975324 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Vogelaar FJ, van Pelt GW, van Leeuwen AM, Willems JM, Tollenaar RAEM, Liefers GJ, et al. Are Disseminated Tumor Cells in Bone Marrow and Tumor-Stroma Ratio Clinically Applicable for Patients Undergoing Surgical Resection of Primary Colorectal Cancer? The Leiden MRD Study. Cell Oncol Dordr (2016) 39:537–44. doi: 10.1007/s13402-016-0296-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Zunder SM, Gerger A, Schaberl-Moser R, Greil R, Bachleitner-Hofmann T, Bareck E, et al. Prognostic and Predictive Value of the Tumor-Stroma Ratio in STAGE II Colon Cancer. Clin Oncol (2020) 3:2–8. doi: 10.31487/j.COR.2020.04.12 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Jakubowska K, Kisielewski W, Kańczuga-Koda L, Koda M, Famulski W. Diagnostic Value of Inflammatory Cell Infiltrates, Tumor Stroma Percentage and Disease-Free Survival in Patients With Colorectal Cancer. Oncol Lett (2017) 14:3869–77. doi: 10.3892/ol.2017.6639 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Eriksen AC, Sørensen FB, Lindebjerg J, Hager H, dePont Christensen R, Kjær-Frifeldt S, et al. The Prognostic Value of Tumour Stroma Ratio and Tumour Budding in Stage II Colon Cancer. A Nationwide Population-Based Study. Int J Colorectal Dis (2018) 33:1115–24. doi: 10.1007/s00384-018-3076-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Mesker WE, Junggeburt JMC, Szuhai K, de Heer P, Morreau H, Tanke HJ, et al. The Carcinoma-Stromal Ratio of Colon Carcinoma is an Independent Factor for Survival Compared to Lymph Node Status and Tumor Stage. Cell Oncol (2007) 29:387–98. doi: 10.1155/2007/175276 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Zunder S, van der Wilk P, Gelderblom H, Dekker T, Mancao C, Kiialainen A, et al. Stromal Organization as Predictive Biomarker for the Treatment of Colon Cancer With Adjuvant Bevacizumab; a Post-Hoc Analysis of the AVANT Trial. Cell Oncol Dordr (2019) 42:717–25. doi: 10.1007/s13402-019-00449-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Frontiers | Prognostic Value of Tumor-Stroma Ratio in Rectal Cancer: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis | Oncology (Accessed October 6, 2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 32. Martin B, Banner BM, Schäfer E-M, Mayr P, Anthuber M, Schenkirsch G, et al. Tumor Proportion in Colon Cancer: Results From a Semiautomatic Image Analysis Approach. Virchows Arch (2020) 477:185–93. doi: 10.1007/s00428-020-02764-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Wu J, Liang C, Chen M, Su W. Association Between Tumor-Stroma Ratio and Prognosis in Solid Tumor Patients: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Oncotarget (2016) 7:68954–65. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.12135 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Kemi N, Eskuri M, Kauppila JH. Tumour-Stroma Ratio and 5-Year Mortality in Gastric Adenocarcinoma: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Sci Rep (2019) 9:16018. doi: 10.1038/s41598-019-52606-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Giatromanolaki A, Sivridis E, Koukourakis MI. The Pathology of Tumor Stromatogenesis. Cancer Biol Ther (2007) 6:639–45. doi: 10.4161/cbt.6.5.4198 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Bissell MJ, Radisky D. Putting Tumours in Context. Nat Rev Cancer (2001) 1:46–54. doi: 10.1038/35094059 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Luo H, Tu G, Liu Z, Liu M. Cancer-Associated Fibroblasts: A Multifaceted Driver of Breast Cancer Progression. Cancer Lett (2015) 361:155–63. doi: 10.1016/j.canlet.2015.02.018 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Shimoda M, Mellody KT, Orimo A. Carcinoma-Associated Fibroblasts are a Rate-Limiting Determinant for Tumour Progression. Semin Cell Dev Biol (2010) 21:19–25. doi: 10.1016/j.semcdb.2009.10.002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/ Supplementary Material . Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.