Supplemental Digital Content is available in the text.

Key Words: COVID-19, laparoscopic, surgery, MIS, recommendation, systematic review

Background:

The coronavirus 2019 pandemic and the hypothetical risk of virus transmission through aerosolized CO2 or surgical smoke produced during minimally invasive surgery (MIS) procedures have prompted societies to issue recommendations on measures to reduce this risk. The aim of this systematic review is to identify, summarize and critically appraise recommendations from surgical societies on intraoperative measures to reduce the risk of severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 transmission to the operative room (OR) staff during MIS.

Methods:

Medline, Embase, and Google Scholar databases were searched using a search strategy or free terms. The search was supplemented with searches of additional relevant records on coronavirus 2019 resource websites from Surgical Associations and Societies. Recommendations published by surgical societies that reported on the intraoperative methods to reduce the risk of severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 transmission to the OR staff during MIS were also reviewed for inclusion. Expert opinion articles were excluded. A preliminary synthesis was performed of the extracted data to categorize and itemize the different types of recommendations. The results were then summarized in a narrative synthesis.

Results:

Thirty-three recommendation were included in the study. Most recommendations were targeted to general surgery (13) and gynecology (8). Areas covered by the documents were recommendations on performance of laparoscopic/robotic surgery versus open approach (28 documents), selection of surgical staff (13), management of pneumoperitoneum (33), use of energy devices (20), and management of surgical smoke and pneumoperitoneum desufflation (33) with varying degree of consensus on the specific recommendations among the documents.

Conclusions:

While some of the early recommendations advised against the use of MIS, they were not strictly based on the available scientific evidence. After further consideration of the literature and of the well-known benefits of laparoscopy to the patient, later recommendations shifted to encouraging the use of MIS as long as adequate precautions could be taken to protect the safety of the OR staff. The release and implementation of recommendations should be based on evidence-based practices that allows health care systems to provide safe surgical and medical assistance.

Severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) is responsible for a worldwide epidemic, which was declared as a pandemic by the World Health Organization on March 11, 2020. The current evidence suggests the primary source of transmission of SARS-CoV-2 is through respiratory droplets (particles>5 to 10 μm in diameter)1 from infected people and through contact with contaminated surfaces.2 There is growing evidence that coronavirus 2019 (COVID-19) infection may also occur from airborne exposure to the virus under certain circumstances.3

Given that the transmission mechanism of this virus is still largely unknown, concerns have been raised regarding the possibility of virus transmission to the operative room (OR) staff during surgical procedures. In particular, Cahmpault et al4 questioned the potential creation of aerosols containing contaminated material from CO2 leakage, as well as the creation of surgical smoke from energy devices during laparoscopic procedures.

Although the risk of viral transmission in the OR was not unknown to experts, the use of measures to address it before the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic were either lacking or not widely adopted. The sudden spread of the disease put significant pressure on surgical societies to quickly address the safety issues related to performing surgical procedures in this environment. For this reason, initial recommendations were issued, in particular leveraging the initial experiences from China, to stop elective surgery and to avoid laparoscopic procedures, favoring an open approach. The Royal College of Surgeons and associated societies updated their recommendations, suggesting that proponents of laparoscopy during the COVID-19 pandemic understand the potential risks and the need for risk mitigation strategies. The recommendations included the use of technological protection and enhanced personal protective equipment (PPE). Societies continued to suggest that laparoscopy can be cautiously re-established when mitigation criteria were met, OR teams were satisfied with the safety measures and when the teams considered the benefits of laparoscopy outweigh the risks in their local OR set-up.5

Other recommendations, along with expert opinion articles on which measures to adopt to reduce the risk of viral transmission during laparoscopic and robotic procedures have been published since the beginning of the pandemic. Areas which were frequently discussed include the adoption of PPE, workflow and organizational protocols, procedure prioritization, pneumoperitoneum management (including CO2 leaks), and the use of energy devices, and smoke evacuation technologies.

Currently, there is no evidence of the presence of SARS-CoV-2 in surgical smoke or in the aerosolized CO2 from laparoscopic procedures, but for the sake of safety and in lieu of lacking evidence, recommendations were set assuming the presence of the virus in these mediums. Many recommendations were based on opinion or a thought process, rather than evidence.

Laparoscopy has been demonstrated to bring significant advantages over the open approach,6 even more so during a pandemic, since it may reduce hospital length of stay and, potentially, postoperative complications. For this reason, it is important to identify effective measures to reduce the risk of viral transmission to the OR staff, based on scientific evidence.

The aim of this systematic review is to identify, summarize and critically appraise recommendations from surgical societies focusing on intraoperative measures to reduce the risk of SARS-CoV-2 transmission to the OR staff.

METHODS

Search Strategy

A comprehensive literature search was performed according to the 2009 Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-analysis (PRISMA) guidelines.7 To identify published articles reporting recommendations on intraoperative measures to reduce the risk of SARS-CoV-2 transmission to the OR staff during MIS procedures, a combination of keywords (MeSH terms and free text words) including (“COVID-19” OR “SARS-CoV-2” OR “Coronavirus” OR “coronavirus infections”) AND (“laparoscopy” OR “laparoscopic surgery” OR “robotic surgery” OR “minimally invasive surgery” OR “MIS” OR “minimally invasive procedures”) AND (“recommendations” OR “guidelines” OR “position” OR “statement”) were used to search Medline, Embase, and Google Scholar databases (search strategies are provided in the Supplementary material, Supplemental Digital Content 1, http://links.lww.com/SLE/A293). The search was supplemented to include pertinent references from the retrieved articles as well as searches of additional relevant records on COVID-19 resource websites from Surgical Associations and Societies to identify recommendations which were not published in journals. The search included publications from October 1, 2019 through November 20, 2020.

Eligibility Criteria

Articles were eligible for inclusion if they contained societies’ guidelines or recommendations detailing measures to adopt during minimally invasive abdominal surgery (including laparoscopy and robotic abdominal surgery) to reduce the risk of SARS-CoV-2 transmission to the OR staff. The exclusion criteria were as follows: (1) not focused on laparoscopy or robotic abdominal surgery; (2) not containing official recommendations from a surgical society involving OR practices during the COVID-19 pandemic; (3) expert opinion articles; and (3) language other than English.

Information Sources

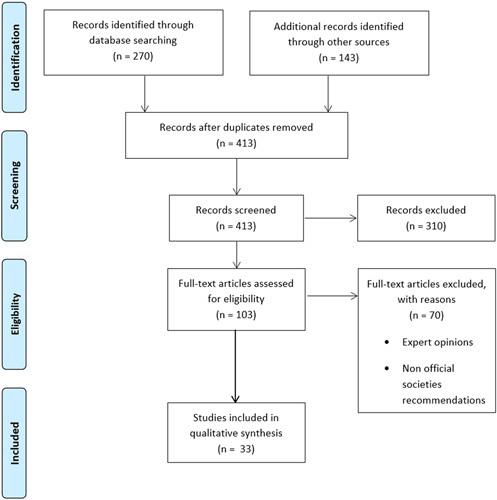

The search yielded 413 articles, after exclusion of duplicates. Two authors independently identified and reviewed the titles and abstracts. For an article to be excluded, both reviewers had to agree that the study was not relevant. One or more of the following areas or recommendations had to be present in the article to include it in the analysis: recommendation on whether to perform minimally invasive surgery (MIS), selection of surgeon to perform MIS, use of energy devices, use of smoke evacuation systems, recommendation on access and on creation and maintenance of pneumoperitoneum. After reviewing the titles and abstracts, 103 papers were identified as potentially eligible for inclusion. After a full-text review, 33 documents were deemed eligible and were included. The Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-analysis flow diagram is shown in Figure 1.

FIGURE 1.

Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-analysis flow diagram of the study.

Data Extraction

Two independent reviewers extracted relevant recommendations from each guideline. Disagreements concerning data extraction were resolved by discussion and consensus. Thereafter, a recommendation matrix was constructed. The following variables were extracted from the articles: list of authors, title of the article, name of the society, publication date, country, type of surgery, recommendation on the surgeon(s) to involve in MIS procedures, the choice between MIS or open approach, the use of energy devices, the use of smoke evacuation systems, on any measure to limit CO2 escape from trocars, and on creation and maintenance of pneumoperitoneum.

Data Synthesis and Analysis

A preliminary synthesis was performed of the extracted data to categorize and itemize the different types of recommendations. The results were then summarized in a narrative synthesis.

RESULTS

The initial search in Medline, Embase and Google Scholar returned 413 records. After eligibility assessment, a total of 33 recommendation/guidelines/guidance/positions were included in the study.8–40

General Information

Regarding country, 14 items were issued by European societies12,13,15,16,18,21–24,28,31–33,38 and 3 from the United States.8,19,27 One of the recommendations was issued jointly by 1 European and 1 American society.20 The remaining 15 recommendations were issued by Asian (6),9,25,26,35–37 South American (3),14,29,30 African (2),11,34 Australian/New Zealand (1),40 and International (3)10,17,39 societies.

Most recommendations were targeted to general surgery (13)8,12,17,20,25,26,29–31,33,35,37,38 and gynecology (8).10,11,18,19,21,22,34,39 Other specialties involved were urology (4),23,28,32,40 pediatric surgery (3),15,28,36 bariatric surgery (3),9,14,16 oncologic surgery,16 endocrine surgery,13 and various specialties,27 with 1 document each.

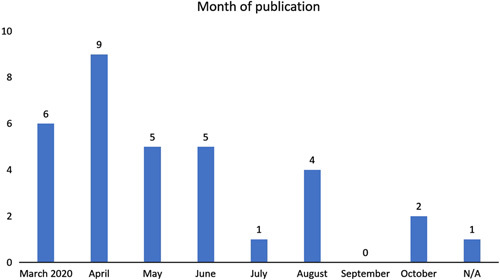

As it may be expected, most recommendations were published between the months of March (6)8,15,17,18,21,31 and April (9),12,20,22,26,28,30,32,34,40 as well as the immediately following months, May11,33,35,37,38 and June,13,19,24,25,29 with 5 documents for each of those 2 months (Fig. 2). Four recommendations were published in August,9,14,27,39 2 in October,16,36 and 1 in July.10 No document was issued in September, while no publication date was possible to retrieve for the recommendations from EAU Robotic Urology Section.23

FIGURE 2.

Month of publication of the recommendations. N/A indicates not available.

Laparoscopic/Robotic Approach Versus Open Approach

Twenty-eight documents discuss the opportunity of performing minimally invasive procedures, including laparoscopy or robotic surgery during COVID-19 pandemic.8,10–21,23–25,27–35,38–40 Fourteen did not recommend adopting an open approach over MIS,10,12–14,18–20,29,32,34,35,38–40 claiming that there is very limited evidence regarding the relative risks of MIS versus the open approach specific to COVID-19 and some stated that MIS might be beneficial for the health system18,34 and that open surgery should not be considered to be safer than MIS.14,19 These documents called out specific measures to reduce residual risks correlated with MIS procedures. Seven recommendations indicate that a risk/benefit evaluation be performed before deciding to use an MIS approach, because of the risk of viral aerosol dissemination.15,16,24,25,28,30,33 Seven recommendations,8,11,21,23,26,31,36 on the other hand, suggested limiting the MIS approach due to the unknown risk of viral transmission through aerosolized CO2 and surgical smoke produced. Documents that did not specify if MIS procedures can be performed using specific measures, were considered MIS feasible (Table 1).9,17,22,26,36

TABLE 1.

Recommendations of National and International Societies Regarding Adoption of Laparoscopy and Surgeon Performing Laparoscopic Procedures

| Society/References | Surgeon | Laparoscopic Approach |

|---|---|---|

| ACS8 | — | Consider avoiding laparoscopy |

| Aggarwal et al9 | Develop procedure-specific “time out” checklists 2 trained surgeons pairing up | — |

| Joint Gyn10 | — | No evidence to suggest that respiratory viruses are transmitted through abdominal route from patients to health care providers in OR |

| Alabi et al11 | Very experienced endo surgeon | Use open surgery over laparoscopic surgery. Emergencies: open surgery where there is no experienced laparoscopy surgeon available |

| ALSGBI12 | Laparoscopic procedures should be carried out by senior, trained laparoscopic surgeons | Laparoscopy should still be employed in treating both elective and emergency patients |

| Aygun et al13 | The surgical procedure should preferably be performed by an experienced surgeon | Endoscopic procedures can be applied with precautions |

| BAPES15 | — | A decision needs to be made whether the risk to staff is outweighed by the benefit to the patient of laparoscopy over an open approach |

| Cavaliere et al16 | MIS acceptable if surgeon is confident with the technique | Decision is left to surgeons, who must carefully consider the aspects and risks of their choice |

| Chiu et al17 | — | — |

| ESGE18 | — | Laparoscopy for gynecological emergencies and cancer would be beneficial for the health system by reducing hospital stay. This should be weighed against possible disadvantages of laparoscopic surgery during the outbreak |

| Fader et al19 | — | Open surgery should not be considered safer than MIS |

| Francis et al20 | — | There is very little evidence regarding the relative risks of MIS vs. the open approach specific to COVID-19 |

| RCOG/BSGE21 | — | Operations that carry a risk of bowel involvement should be performed by laparotomy Elective gynecological operations with risk of bowel involvement should be deferred |

| Kimmig et al22 | — | — |

| Mottrie et al23 | — | Any laparoscopic or robotic surgery should only be performed when needed |

| Navarra et al24 | — | Insufficient data to recommend for/against an open versus laparoscopy approach |

| Nugroho et al25 | Laparoscopic procedures should be undertaken by the most experienced surgeon. Choose only easy laparoscopic cases | In the absence of convincing data, the safest approach may be the one that is most familiar to the surgeon and reduces the operative time. If the recommended standard cannot be fulfilled, it is best not to perform laparoscopic procedure |

| PALES26 | Limit laparoscopic procedure to the most proficient surgeon | — |

| Porter et al27 | — | MIS procedures should be limited to planned urgent or emergency procedures |

| Quaedackers28 | Surgery should be performed by experienced surgeons | No conclusive evidence regarding the differences in risks of open vs laparoscopic surgery for the surgical team. However, laparoscopic surgery may be associated with a higher amount of smoke particles than open surgery. |

| Quaranta et al29 | Surgeries should be performed by an expert surgeon | Do not modify preferred surgical approach and technique, it is safer to the patient and the team. Should be based on medical criterion, including patients with surgical emergencies and severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 infection. |

| Ramos et al30 | — | Evaluated case by case. The benefit of the laparoscopic approach should outweigh the risk of viral aerosol dissemination |

| UK Intercoll31 | — | Considerable caution is advised. Consider laparoscopy only in selected individual cases where clinical benefit to the patient substantially exceeds the risk of potential viral transmission |

| Ribal et al32 | All MIS procedures should preferably be performed by experienced surgeons | No specific data demonstrating an aerosol presence of the COVID-19 virus released during minimally invasive abdominal surgery |

| Softiou et al33 | Laparoscopy will be performed based on the degree of competence of the operating team, institutional protocols, as well as the availability of specific equipment | If laparoscopic procedures involve an extended surgical time, in the context of prolonged wearing of high protection equipment with unfavorable ergonomic impact, breaks or conversion to open technique will be considered |

| SASREG34 | Laparoscopy still holds numerous advantages over open surgery, especially during this pandemic. Steps should be taken to mitigate any potential risk of viral transmission | |

| Shabbir et al35 | The most appropriate skilled person as chosen by the team lead should perform the surgery | No evidence to suggest for or against laparoscopic surgery versus open surgery. Provide a safe, optimal, efficient care that is proportionate with the available manpower and infrastructure resources |

| Sharma and Saha36 | — | Resume laparoscopy when the guidelines and pandemic conditions allow |

| Srivastava et al37 | — | — |

| Stabilini et al38 | — | No evidence for contraindication of the laparoscopic approach. Laparoscopy allows better control of surgical smoke/plume than laparotomy |

| Thomas et al39 | The most experienced, proficient and knowledgeable surgeon available should perform the procedure | No robust evidence of increased risk of viral transmission during laparoscopy. All precautions must be taken during this time until more evidence becomes available |

| USANZ40 | — | USANZ supports continued use of laparoscopy in urology where appropriate. Limited evidence at this time suggests that the benefits of MIS outweigh the risk and benefits of open surgery |

ACS indicates American College of Surgeons; AGESN, Association of Gynecological Endoscopy Surgeons of Nigeria; ALSGBI, Association of Laparoscopic Surgeons Great Britain and Ireland; ARCE, Asociaţia Română de Chirurgie Endoscopică; BAPES, British Association of Pediatric Endoscopic Surgeons; BSGE, Bristih Sociey for Gynaecological Endoscopy; CBC, Colégio Brasileiro de Cirurgiões; COVID, coronavirus; EAES, European Association for Endoscopic Surgery; EAU, European Association of Urology; EHS, European Hernia Society; ELSA, Endoscopic and Laparoscopic Surgeons of Asia; ESGE, European Society for Gynecological Endscopy; IAPS, Indian Association of Pediatric Surgeons; Indian intersoc., Indian inter-society directives; ISDE, International Society for Diseases of the Esophagus; ISDS, Indonesian Society of Digestive Surgeons; ISGE, International Society for Gynecologic Endoscopy; Joint Gyn, Joint Gyn, Joint Gynecologic Societies Statement; MIS, minimally invasive surgery; OSSI, Obesity and Metabolic Surgery Society of India; PALES, Philippine Association of Laparoscopic and Endoscopic Surgeons; RCOG, Royal College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists; SACL, Sociedad Argentina de Cirugía Laparoscópica; SAGES, Society of American Gastrointestinal and Endoscopic Surgeons; SASREG, Southern African Sociey for Reproductive Medicine and Gynaecological Endoscopy; SERGS, Society of European Robotic Gynaecological Surgery; SGO, Society of Gynecologic Oncology; SICO, Società Italiana di Chirurgia Oncologica; SICOB, Società Italiana di Chirurgia dell’Obesità; SRED, Societatea Română de Endoscopie Digestivă; SRS, Society of Robotic Surgery; TAES, Turkish Association of Endocrine Surgery; UK Intercoll., Intercollegiate General Surgery Guidance; USANZ, Urological Society of Australia and New Zealand.

Selection of Surgical Staff

Thirteen recommendations suggested that the selection of the surgeon performing MIS procedures is critical.9,11–13,16,25,26,28,29,32,33,35,39 All 13 also recommended that senior, trained laparoscopic surgeons should perform the procedures. OSSI suggested that a procedure-specific “time out” checklists be developed and that 2 trained surgeons pair up to perform the procedures.9 ISDS proposed that only easy laparoscopic cases should be performed,25 while SRED/ARCE recommended that laparoscopy should be performed based on the degree of competence of the operating team, institutional protocols, and the availability of specific equipment (Table 1).33

Management of Peritoneum

All documents provided recommendations on the safe evacuation and management of the pneumoperitoneum. The references suggested not to evacuate the pneumoperitoneum for specimen extraction, for trocar re-insertion and at the end of the procedure without suction (entirely aspiration) or a filtered system. The Joint Statement of Gynecologic Societies recommends avoiding rapid desufflation or loss of pneumoperitoneum (Table 2).10

TABLE 2.

Recommendations of National and International Societies for Intraoperative Measures to Reduce Transmission Risk of COVID-1 Virus

| Recommendation | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Society/References | PP With Most Familiar Technique | Low CO2 Insufflation Pressure | Minimal Use Electrocautery | Low Power Setting of Electrocautery | Avoid or Limit Advanced Devices (US/ABP)* | Avoid Long Desiccation Times | Ultra-filtration of Smoke | Safe evacuation of Pneumoperitoneum Via Suction or Filtration System | Avoid 2-Way Insufflators/Use Intelligent Insufflators | Reduce or Avoid Trendelenburg | Avoid Open Technique |

| ACS8 | √ | √ | |||||||||

| Aggarwal et al9 | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | |||||

| Joint Gyn stat10 | √ (10-12 mm Hg) | √ | √ | ULPA | √ | ||||||

| Alabi et al11 | √ | √ | √ | ||||||||

| ALSGBI12 | √ (≤12 mm Hg) | √ | ULPA | √ | |||||||

| Aygun et al13 | √ (avoid) | √ | ULPA | √ | |||||||

| Behrens et al14 | √ (10-15 mm Hg) | √ | √ | ||||||||

| BAPES15 | √ | √ | |||||||||

| Cavaliere et al16 | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | ||||||

| Chiu et al17 | √ | √ | |||||||||

| ESGE18 | √ | √ | √ | √ | |||||||

| Fader et al19 | √ | √ | √ | ULPA/HEPA | √ | ||||||

| Francis et al20 | √ | √ | √ | ULPA | √ | ||||||

| RCOG/BSGE21 | √ | √ | |||||||||

| Kimmig et al22 | √ | √ | √ | ULPA | √ | ||||||

| Mottrie et al23 | √ | √ | √ | ULPA | √ | √ | |||||

| Navarra et al24 | √ (<10 mm Hg) | √ | √ | √ | ULPA | √ | √ | ||||

| Nugroho et al25 | √ | √ | ULPA | √ | |||||||

| PALES26 | √ (8-10 mm Hg) | √ | √ | √ | √ | ||||||

| Porter et al27 | √ | √ | √ | √ | ULPA | √ | |||||

| Quaedackers28 | √ | √ | √ | - | √ | √ | |||||

| Quaranta et al29 | √ (<12 mm Hg) | √ | √ | √ | √ | ||||||

| Ramos et al30 | √ (10-12 mm Hg) | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | |||||

| UK Intercoll31 | √ | √ | |||||||||

| Ribal et al32 | √ | √ | √ | √ | |||||||

| Softiou et al33 | √ | √ | √ | ||||||||

| SASREG34 | √ (10-12 mm Hg) | √ | √ | √ | |||||||

| Shabbir et al35 | √ (10-12 mm Hg) | √ | √ | √ | ULPA | √ | √ | ||||

| Sharma and Saha36 | √ | √ | √ | ULPA | √ | √ | |||||

| Srivastava et al37 | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | |||||

| Stabilini et al38 | √ | √ | √ | ||||||||

| Thomas et al39 | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | |||||

| USANZ40 | √ | √ | HEPA | √ | |||||||

Including statements suggesting that smoke from ultrasonic devices may be more dangerous that basic electrocautery.

√ indicates present in the recommendation; ACS, American College of Surgeons; AGESN, Association of Gynecological Endoscopy Surgeons of Nigeria; ALSGBI, Association of Laparoscopic Surgeons Great Britain and Ireland; ARCE, Asociaţia Română de Chirurgie Endoscopică; BAPES, British Association of Paediatric Endoscopic Surgeons; BSGE, Bristih Sociey for Gynaecological Endoscopy; CBC, Colégio Brasileiro de Cirurgiões; EAES, European Association for Endoscopic Surgery; EAU, European Association of Urology; EHS, European Hernia Society; ELSA, Endoscopic and Laparoscopic Surgeons of Asia; ESGE, European Society for Gynecological Endscopy; HEPA, high-efficiency particulate air; IAPS, Indian Association of Pediatric Surgeons; Indian intersoc., Indian inter-society directives; ISDE, International Society for Diseases of the Esophagus; ISDS, Indonesian Society of Digestive Surgeons; ISGE, International Society for Gynecologic Endoscopy; Joint Gyn, Joint Gyn, Joint Gynecologic Societies Statement; OSSI, Obesity and Metabolic Surgery Society of India; PALES, Philippine Association of Laparoscopic and Endoscopic Surgeons; PP, pneumoperitoneum; RCOG, Royal College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists; SACL, Sociedad Argentina de Cirugía Laparoscópica; SAGES, Society of American Gastrointestinal and Endoscopic Surgeons; SASREG, Southern African Sociey for Reproductive Medicine and Gynaecological Endoscopy; SERGS, Society of European Robotic Gynaecological Surgery; SGO, Society of Gynecologic Oncology; SICO, Società Italiana di Chirurgia Oncologica; SICOB, Società Italiana di Chirurgia dell’Obesità; SRED, Societatea Română de Endoscopie Digestivă; SRS, Society of Robotic Surgery; TAES, Turkish Association of Endocrine Surgery; UK Intercoll., Intercollegiate General Surgery Guidance; ULPA, ultra-low particulate air; USANZ, Urological Society of Australia and New Zealand.

Twenty-one societies also recommend using the lowest intra-abdominal pressure without compromising surgical exposure or patient safety.9,10,12,14,16,19,20,22–30,32–35,39 Four societies recommend an intra-abdominal pressure of 10 to 12 mm Hg,10,30,34,35 2 societies a pressure ≤12 mm Hg,12,29 the Italian Society of Bariatric Surgery24 suggests a pressure of <10 mm Hg, the International Federation for the Surgery of Obesity and Metabolic Disorders—Latin American Chapter14 indicates pressures from 10 to 15 mm Hg, while the Philippine Association of Laparoscopic and Endoscopic Surgeons26 suggests a pressure of 8 to 10 mm Hg. Three societies recommend avoiding the use of 2-way insufflators,23,28,35 while one of the societies suggested the use of intelligent integrated flow systems.23

Seven documents indicated that Trendelenburg position be reduced or avoided which would reduce blood return to the pulmonary area.16,24,26,29,30,36,37 The Obesity and Metabolic Surgery Society of India recommends using the most familiar technique for pneumoperitoneum creation, but to avoid open techniques.9

Access and Trocar Use

Twenty-three societies gave recommendations on how to manage CO2 leaks from trocars.9,10,12–14,16,18–22,24–27,30,32–36,38,39 Fourteen societies provided recommendations regarding methods to reduce CO2 leaks around trocars, such as minimizing the size of skin incisions for ports to allow for the passage of ports but not allow for leakage around ports,12,14,16,20,24–27,33,35,38,39 avoid unnecessary incisions,13 and reduce the amount and size of trocars.24,30,39 Eleven documents provided other recommendations regarding methods to reduce CO2 leaks through the trocars. The suggestions included that the trocars be removed after complete evacuation of pneumoperitoneum,9,25,30 close taps of ports before insertion or reposition,14,18,22,34,39 do not open taps of ports13,26 unless attached to a CO2 filter or being used to deliver the gas,22,37 do not insert trocars while on pneumoperitoneum25 and avoiding sudden release of trocar valves and nonairtight exchange of instruments (Table 3).24

TABLE 3.

Recommendations of National and International Societies for Intraoperative Measures to Reduce Transmission Risk of COVID-1 Virus. Continued

| Recommendations | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Society/References | Optical Trocar | Fixation | Careful Handling | Valve Closed or Not Remove if PP | Check Seals | Disposable Trocars | Smallest Incision/Reduce Ports | Minimize Instruments Exchange | Veress Needle | Port Positioning and Instrument Choice According to Standard | No 8 mm Instruments in 12 mm Port w/o Adapter, No 5 mm in 12 mm Port |

| ACS8 | |||||||||||

| Aggarwal et al9 | √ | Balloon trocar | √ | √ | |||||||

| Joint Gyn stat10 | √ | √ | |||||||||

| Alabi et al11 | |||||||||||

| ALSGBI12 | √ | √ | √ | ||||||||

| Aygun et al13 | Balloon trocars | √ | √ | ||||||||

| Behrens et al14 | √ | √ | |||||||||

| BAPES15 | |||||||||||

| Cavaliere et al 16 | Balloon trocars | √ | |||||||||

| Chiu et al17 | |||||||||||

| ESGE18 | √ | √ | |||||||||

| Fader et al19 | √ | ||||||||||

| Francis et al20 | √ | ||||||||||

| RCOG/BSGE21 | √ | ||||||||||

| Kimmig et al22 | √ | √ | |||||||||

| Mottrie et al23 | |||||||||||

| Navarra et al24 | Balloon trocars/purse string suture | √ | √ | √ | |||||||

| Nugroho et al25 | √ | √ | |||||||||

| PALES26 | √ | √ | √ | √ | |||||||

| Porter et al27 | √ | √ | |||||||||

| Quaedackers28 | |||||||||||

| Quaranta et al29 | |||||||||||

| Ramos et al30 | Balloon trocars/purse string suture | √ | √ | √ | √ | ||||||

| UK Intercoll31 | |||||||||||

| Ribal et al32 | √ | ||||||||||

| Softiou et al33 | √ | ||||||||||

| SASREG34 | √ | √ | √ | √ | |||||||

| Shabbir et al35 | √ | Balloon trocars/purse string suture | √ | √ | |||||||

| Sharma and Saha36 | √ | ||||||||||

| Srivastava et al37 | |||||||||||

| Stabilini et al38 | Balloon trocars | √ | |||||||||

| Thomas et al39 | √ | √ | |||||||||

| USANZ40 | |||||||||||

√ indicates present in the recommendation; ACS, American College of Surgeons; AGESN, Association of Gynecological Endoscopy Surgeons of Nigeria; ALSGBI, Association of Laparoscopic Surgeons Great Britain and Ireland; ARCE, Asociaţia Română de Chirurgie Endoscopică; BAPES, British Association of Paediatric Endoscopic Surgeons; BSGE, Bristih Sociey for Gynaecological Endoscopy; CBC, Colégio Brasileiro de Cirurgiões; EAES, European Association for Endoscopic Surgery; EAU, European Association of Urology; EHS, European Hernia Society; ELSA, Endoscopic and Laparoscopic Surgeons of Asia; ESGE, European Society for Gynecological Endscopy; IAPS, Indian Association of Pediatric Surgeons; Indian intersoc., Indian inter-society directives; ISDE, International Society for Diseases of the Esophagus; ISDS, Indonesian Society of Digestive Surgeons; ISGE, International Society for Gynecologic Endoscopy; Joint Gyn, Joint Gyn, Joint Gynecologic Societies Statement; OSSI, Obesity and Metabolic Surgery Society of India; PALES, Philippine Association of Laparoscopic and Endoscopic Surgeons; PP, pneumoperitoneum; RCOG, Royal College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists; SACL, Sociedad Argentina de Cirugía Laparoscópica; SAGES, Society of American Gastrointestinal and Endoscopic Surgeons; SASREG, Southern African Sociey for Reproductive Medicine and Gynaecological Endoscopy; SERGS, Society of European Robotic Gynaecological Surgery; SGO, Society of Gynecologic Oncology; SICO, Società Italiana di Chirurgia Oncologica; SICOB, Società Italiana di Chirurgia dell’Obesità; SRED, Societatea Română de Endoscopie Digestivă; SRS, Society of Robotic Surgery; TAES, Turkish Association of Endocrine Surgery; UK Intercoll., Intercollegiate General Surgery Guidance; USANZ, Urological Society of Australia and New Zealand.

The use of balloon trocars was recommended by 7 societies,9,13,16,24,30,35,38 with 3 of the societies suggesting a purse string suture around the trocars as an alternative.24,30,35 Two documents suggested fixating the trocars.19,36

Seven recommendations suggest minimizing instrument exchanges,12,18,22,24,26,30,34 4 to check trocar valve integrity10,27,30,34 and to use disposable trocars,10,26,34,35 2 to carefully handle trocars,9,12 2 to use optical trocars,9,35 1 to use Veress needle13 or to avoid inserting 8 mm instruments in 12 mm trocars without an adapter or 5 mm instruments in 12 mm trocars even with an adapter.32 The Royal College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists and British Society for Gynaecological Endoscopy jointly recommend positioning ports and choosing instruments according to the surgeon and hospitals usual practice to minimize time in theater and the risk of operative complications.21

Use of Energy Devices

Twelve articles advise to minimize11,12,18,20,24,29,35–37,39,40 or avoid13 the use of electrocautery and energy devices due to the risk of the potential presence of viral particles in the smoke plume. Five of these recommendations,20,35,37,39,40 together with 8 other recommendations9,10,19,22,23,26–28 additionally suggest lowering the power setting on electrocautery and ultrasonic devices for the same reason. Minimization of desiccation times is also recommended by 8 documents (Table 2).10,19,24,27,30,35–37

Several articles also differentiate among alternative types of energy devices, claiming that 1 type of energy might be safer than others with respect to the creation of surgical smoke, and some also suggest specifically not to use ultrasonic or advanced bipolar devices. The Turkish Association of Endocrine Surgeons13 suggests that the use of bipolar electrocautery can produce less smoke than monopolar cautery or ultrasonic devices, the Society of European Robotic Gynaecological Surgery advises to avoid the use of ultrasonic sealing and if possible, to use electrothermal bipolar vessel sealing.22 The EAU recommendations23,28,32 indicate that the low-temperature aerosol from ultrasonic scalpels or scissors cannot effectively deactivate the cellular components of virus in patients compared with conventional diathermy. The Indonesian Society of Digestive Surgeons recommends that ultrasonic dissectors and advanced bipolar devices should be minimized, as they can lead to particle aerosolization,25 while the Society for Robotic Surgery27 also claims that ultrasonic devices create significant aerosol without desiccation of tissue, and potentially viral release and suggest they should be used judiciously. For the Indian Association of Pediatric Surgeons,36 the various energy sources lead to different sizes of particles, electrocautery, and LASER having the smallest, hottest particles and ultrasonic devices larger, cooler particles, suggesting that the former are less dangerous. The European Hernia Society38 advises to avoid energy devices which produce more particles (eg, ultrasonic devices) and, finally, the International Society for Gynecologic Endoscopy39 emphasizes that the theoretical risk of increased smoke and particle dispersion is associated with the high frequency oscillating mechanism of ultrasonic devices.

Management of Surgical Smoke and Pneumoperitoneum Desufflation

All documents reported recommendations regarding measures to evacuate surgical smoke and on how to desufflate the pneumoperitoneum. All the societies, except the EAU Pediatric suggest the use of a closed smoke evacuation system connected to a filter to evacuate smoke and/or pneumoperitoneum before port exchange or specimen retrieval or at the end of the procedure (Table 2).

DISCUSSION

The spread of the COVID-19 pandemic has exerted significant pressure on the health care systems worldwide. It also has impacted both elective and emergent surgical activities—which were either halted or substantially reduced. Surgical activities were affected due to the lack of information around the possibility of viral transmission to patients, surgeons and OR staff during surgical procedures.

MIS procedures such as laparoscopy and abdominal robotic surgery are aerosol-generating procedures due to the creation and maintenance of pneumoperitoneum through insufflation of the abdominal cavity with CO2. For this reason, some societies were pressed to release recommendations during the first phase of the pandemic and suggested stopping MIS approaches in favor of open. In the following weeks and months, several recommendations were issued suggesting, instead, to consider using MIS approaches while adopting additional methods to minimize aerosolization of CO2, reducing or evacuating surgical smoke and enhancing PPE measures. Even if most of these methods had already been flagged during previous viral outbreaks, mainly for human immunodeficiency virus (HIV),41 they were either underestimated or adopted by only a few.

Considering the urgency to ensure the health and safety of the OR staff, most of these recommendations were based in part on scientific evidence and relied mostly on a theoretical basis. Some recommendations to use certain devices over others were only based on either personal beliefs of the authors or a misinterpretation of available evidence. This systematic review highlighted that societies are in agreement with most of the recommendations.

MIS/Laparoscopic/Robotic Approaches Versus Open Approach

During the very first phase of the pandemic, some medical societies recommended not performing MIS procedures in favor of an open approach regardless of traditional deciding factors for determining surgical approach.5 This recommendation was based the potential transmission of SARS-CoV-2 to the OR staff. As the pandemic continued, almost all societies made the recommendation to adopt a series of measures to reduce the potential risk of viral transmission to the OR staff in support of performing MIS procedures.20 These later recommendations shifted to consider both the safety of the OR staff, as well as the patient. It is therefore acceptable to utilize MIS approaches whenever they are indicated, provided additional safety measures are implemented.

Selection of Surgical Staff

Different recommendations advised allowing only senior staff to perform MIS procedures. This rationale is based on the notion that experienced surgeons are able to complete demanding laparoscopic and robotic surgeries in significantly less time. Wang et al,42 found, however, that the level of seniority does not have a substantial impact on operative times for postgraduate surgeons. The opposite was observed by Kauvar et al,43 where junior residents experienced slower operative times. Other techniques, such as mental training, digital simulators and robotic technologies are becoming helpful for relatively inexperienced surgeons.44–47

Management of Peritoneum

A common recommendation is to reduce the pressure in the pneumoperitoneum to a minimum which will lessen CO2 leakage from trocars. Most of the recommendations suggest pressure levels which are regularly used in laparoscopic procedures (ie, 10 to 15 mm Hg). Rohloff et al,48 showed that a lower insufflation pressure with CO2 at 8 mm Hg may reduce postoperative ileus without any other negative outcome. This finding was further supported and supplemented in several other studies which showed better postoperative recovery (decreased ileus rates),49 reduced pain and hospital stay.50

Trocars

The COVID-19 pandemic has added a new dimension to the debate on trocar safety, injecting fear of contamination from gas leakage into the OR staff on the frontline. Rather than identifying a new risk, the COVID crisis highlighted how the risk of staff contamination during laparoscopy has been dealt with.51 Practically, SARS-CoV-2 is not the only infectious agent which should be considered and there is no reason to distinguish this new virus from prior recommendations which were established pre-COVID-19 pandemic.

On the basis of the perceived gas containment, balloon tip trocars have become more popular. Surgical society guidelines and recommendations have mentioned this property of the balloon trocar, but have not included support for their recommendations.52,53

As suggested by several recommendations, CO2 leakage at the insertion point can be minimized with attention focused on a precise size of the incision. Port placement is often left to junior level surgeons who use varying techniques ranging from a simple eye-ball approach to a meticulous marking of an incision on the skin. High end ports propose a feature ensuring adequate skin incision size: the 45-degree shape of the cannula end allows for printing an oval mark on the skin, the long diameter of which represents the optimal size for low gas leak, low force insertion and high retention force. As mentioned previously, balloon tip trocars can produce better containment of CO2, but can rupture54 which can cause a sudden desufflation.51

Ensuring all ports not in use are closed prior insertion or insufflation, a measure which is present in a number of societies’ recommendations, are easy to miss. A simple “check-list” approach could certainly help prevent these types of events related to trocars. Digital workflow, an emerging OR technology, includes dynamic checklists and reduced variability in the OR.55

Use of Energy Devices

Most recommendations on the use of energy devices focused on reducing use, as well as lowering the power setting when using. Some suggested avoiding the use of ultrasonic devices, claiming they produce a low-temperature plume which may not inactivate the virus and thus contain potentially viable virions. These recommendations were based on evidence on other viruses (such as human papilloma virus, hepatitis B virus, and HIV) or a thought process.

Different studies reported the presence of viruses in the surgical smoke produced by energy devices, in particular human papilloma virus,56 hepatitis B virus,57 and HIV.58,59 While some of these studies demonstrated the presence of a virus in an in vitro setting,58,59 others did demonstrate the presence of a virus in the surgical smoke produced in an OR.56,57 The only reported viral transmission to the OR staff was from surgeons operating on genital warts using a laser beam in an open setting, resulting in several OR staff cases of laryngeal papilloma.60,61 There are no reports to date of viral infection from the use of energy modality to the OR team performing laparoscopic or robotic procedures. In addition, there have not been reports nor evidence of transmission to the OR staff during outbreaks of similar airborne viruses.62

Some recommendations during the pandemic suggested surgeons use bipolar energy instead of ultrasonic devices, based on the hypothesis that the latter may produce a cooler plume which is unable to deactivate the virus and thus will contain more viable virions. Ultrasonic shears do produce a cooler, vapor-like plume but its temperature at the site of action is significantly higher than radiofrequency devices.63 There are contrasting results on the presence of viable cells in the plume of ultrasonic devices. A study by Nduka et al64 demonstrated, in an experimental setting, that large quantities of cellular debris were trapped in the plume from both ultrasonic hook and monopolar with a needle probe after ablation of tumors, but no viable cells were isolated from the smoke of either device. However, In et al65 captured and injected into mice the smoke generated from an ultrasonic device activated on cancer cells in a petri dish. Of the 40 injection sites, 16 (40%) grew cancer cells identical to those on the petri dish. On the other hand, no other studies have evaluated the content of infectious material found in the plume from ultrasonic devices.

A recent study by Hayami et al63 evaluated the temperature of the steam from an ultrasonic shear and compared it to an advanced bipolar device. The authors performed an ex vivo animal study and tested the devices in 4 different combinations of device and muscle conditions, including dry-dry, dry-wet, wet-dry, and wet-wet. In this study, bipolar devices produced cooler surgical smoke which is also theoretically incapable of inactivating a virus.

Emam and Cuschieri66 reported opposite results when they compared 2 ultrasonic devices at power levels 3, 4, and 5 in a random fashion in preclinical porcine model. After continuous ultrasonic dissection for 10 to 15 seconds at power level 5, the authors observed that the zone around the jaws which exceeded 60°C was measured at 25.3 and 25.7 mm for the 2 different ultrasonic devices tested. At this power setting with an activation time of 15 seconds, the temperature 1.0 cm away from the tips of the instrument exceeded 140°C. It was observed that temperatures 1 cm away from the jaws of both instruments were all above 80°C for power settings level 4 and level 5.

A recent study from Dalli et al67 evaluated gas leaks from the handles of an advanced bipolar device, a robotic energy device and an ultrasonic device. A video produced by these authors demonstrated significant gas leaks though the handles of the advanced bipolar and the robotic devices, however there was only a small amount of leakage through the handle of the ultrasonic device.

Management of Surgical Smoke and Pneumoperitoneum Desufflation

All documents from surgical societies suggest the use of a closed smoke evacuation system connected to a filter to evacuate smoke and/or pneumoperitoneum before port exchange or specimen retrieval or at the end of the procedure. Considering that only a limited number of health care facilities have smoke evacuation systems with an ultra-low particulate air (or high-efficiency particulate air) filter, some recommendations indicate using suction to evacuate smoke or CO2, either through a normal aspiration system or through a filter. A limited number of recommendations call out the use of specific systems such as Airseal27,40 or PneumoClear.40 The AirSeal system (SurgiQuest Inc., Milford, CT) is a novel class of valve-free insufflation system that enables a stable pneumoperitoneum with continuous smoke evacuation and CO2 recirculation during surgery.68 Even though different studies demonstrated some advantages of this system on operative time and stability of pneumoperitoneum,69 there were also contrasting results.70

CONCLUSIONS

The COVID-19 pandemic has significantly impacted the health care system globally. While in the first phases of the viral outbreak the lack of information on the epidemiology of the SARS-CoV-2 virus justified the rapid action of surgical societies in releasing recommendations based mainly on theoretical considerations. It is now imperative to conduct investigations which produce evidence to guide us in either adjusting past recommendations or to develop new ones. To accurately determine the risk of SARS-CoV-2 transmission during surgery, and in particular during MIS procedures, a careful and scientifically sound evaluation of the presence of the virus in surgical smoke contained in the CO2 dispersed in the OR should be performed. Very often some of the measures called out to reduce the risk of potential viral exposure to the OR team were issued without considering a patients’ health or the impact a recommendation would have on surgical outcomes. The recommendations included several regions covering the globe and in general did not differ across the globe. The recommendations were generally simple to implement; the only recommendation a region may have difficulty addressing for financial reasons is using a smoke evacuator during electrosurgery.

Unfortunately, compliance with recommendation is always an issue and even the strongest, data-based recommendations regarding behavior need to be fully implemented to be effective. The best practices model continues to evolve as literature concerning the coronavirus develops. The surgical staff needs to keep abreast of the latest literature concerning the safety measures to be taken during surgical procedures.

The COVID-19 has been a burden since the beginning of 2020, and notwithstanding the ongoing vaccination strategy, it is believed the SARS-CoV-2 virus will not disappear quickly. No health care system can withstand the restrictive measures which were adopted in the first phase of the pandemic, such as suspending elective surgeries and surgical consultations. Protocols and practical measures should be implemented to sustain a safe surgical environment for both the OR teams and their patients. The development, release and implementation of evidence-based recommendations and guidelines should be the foundation during this and future pandemics to ensure the health care system provides the best surgical and medical care globally.

Supplementary Material

Supplemental Digital Content is available for this article. Direct URL citations appear in the printed text and are provided in the HTML and PDF versions of this article on the journal's website, www.surgical-laparoscopy.com.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The authors thank John Mennone for arranging sponsorship of the study and for reviewing the manuscript.

Footnotes

G.A.T., P.G., C.D.R., J.W.C., and R.S.F. II., are employees of Ethicon Inc., a Johnson & Johnson company.

Contributor Information

Giovanni A. Tommaselli, Email: gtommase@its.jnj.com.

Philippe Grange, Email: pgrange@its.jnj.com.

Crystal D. Ricketts, Email: cricket9@its.jnj.com.

Jeffrey W. Clymer, Email: jclymer@its.jnj.com.

Raymond S. Fryrear, II, Email: rfryrear@its.jnj.com.

REFERENCES

- 1.World Health Organization. Guidelines. Infection prevention and control of epidemic- and pandemic-prone acute respiratory infections in health care [WHO website]. 2014. Available at: https://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/handle/10665/112656/9789241507134_eng.pdf?. Accessed November 20, 2020. [PubMed]

- 2.Li Q, Guan X, Wu P, et al. Early transmission dynamics in Wuhan, China, of novel coronavirus–infected pneumonia. N Engl J Med. 2020;382:1199–1207. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.The Lancet Respiratory Medicine. COVID-19 transmission—up in the air. Lancet. 2020;8:159. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cahmpault G, Taffinder N, Ziol M, et al. Cells are present in the smoke created during laparoscopic surgery. Br J Surg. 1997;84:993–995. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Updated General Surgery Guidance on COVID-1 [Royal College of Surgeon webize]. 2020. Available at: www.rcseng.ac.uk/coronavirus/joint-guidance-for-surgeons-v2/. Accessed December 7, 2020.

- 6.Velanovich V. Laparoscopic vs. open surgery. Surg Endosc. 2000;14:16–21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, et al. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. PLoS Med. 2009;6:e1000097. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.American College of Surgeons. COVID-19: Considerations for Optimum Surgeon Protection Before, During, and After Operation [American College of Sugeons website]. 2020. Available at: www.facs.org/covid-19/clinical-guidance/surgeon-protection. Accessed November 20, 2020.

- 9.Aggarwal S, Mahawar K, Khaitan M, et al. Obesity and Metabolic Surgery Society of India (OSSI) Recommendations for Bariatric and Metabolic Surgery Practice During the COVID-19 Pandemic. Obes Surg. 2020;22:1–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Joint statement on minimally invasive gynecologic surgery during the COVID-19 pandemic. J Minim Invasive Gynecol. 2020;27:1027–1029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Alabi OC, Okohue JE, Adewole AA, et al. Association of gynecological endoscopy surgeons of Nigeria (AGES) advisory on laparoscopic and hysteroscopic procedures during the COVID-19 Pandemic. Niger J Clin Pract. 2020;23:747–749. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Association of the Laparoscopic Surgeons Great Britain and Ireland. Laparoscopy in The Covid-19 Environment – ALSGBI Position Statement [ALSGBI website]. 2020. Available at: www.alsgbi.org/2020/04/22/laparoscopy-in-the-covid-19-environment-alsgbi-positionstatement/. Accessed November 20, 2020.

- 13.Aygun N, Iscan Y, Ozdemir M, et al. Endocrine Surgery during the COVID-19 Pandemic: Recommendations from the Turkish Association of Endocrine Surgery. Sisli Etfal Hastan Tip Bul. 2020;54:117–131. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Behrens E, Poggi L, Aparicio S, et al. COVID-19: IFSO LAC Recommendations for the Resumption of Elective Bariatric Surgery. Obes Surg. 2020;30:4519–4528. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.British Association of Paediatric Endoscopic Surgeons. BAPES Statement: Coronavirus (COVID-19) and endoscopic surgery [BAPES website]. 2020. Available at: www.bapes.org.uk/covid. Accessed November 20, 2020.

- 16.Cavaliere D, Parini D, Marano L, et al. Surgical management of oncologic patient during and after the COVID-19 outbreak: practical recommendations from the Italian society of Surgical Oncology. Updates Surg. 2021;73:321–329. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Chiu PWY, Hassan C, Yip HC, et al. ISDE Guidance Statement: Management of upper-GI Endoscopy and Surgery in COVID-19 outbreak. Dis Esophagus. 2020;33:1–4. [Google Scholar]

- 18.European Society for Gynaecologic Endoscopy. ESGE Recommendations on Gynaecological Laparoscopic Surgery during Covid-19 Outbreak [ESGE website]. 2020. Available at: https://esge.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/03/Covid19StatementESGE.pdf. Accessed November 20, 2020.

- 19.Fader AN, Huh WK, Kesterson J, et al. When to Operate, Hesitate and Reintegrate: Society of Gynecologic Oncology Surgical Considerations during the COVID-19 Pandemic. Gynecol Oncol. 2020;158:236–243. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Francis NA, Dort J, Cho E, et al. SAGES and EAES recommendations for minimally invasive surgery during COVID-19 pandemic. Surg Endosc. 2020;34:2327–2331. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Joint RCOG/BSGE Statement on gynaecological laparoscopic procedures and COVID-19 [Royal College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists website]. 2020. Available at: https://mk0britishsociep8d9m.kinstacdn.com/wp-content/uploads/2020/03/Joint-RCOG-BSGE-Statement-on-gynaecological-laparoscopic-procedures-and-COVID-19.pdf. Accessed November 20, 2020.

- 22.Kimmig R, Verheijen RHM, Rudnicki M. For SERGS Council. Robot assisted surgery during the COVID-19 pandemic, especially for gynecological cancer: a statement of the Society of European Robotic Gynaecological Surgery (SERGS). J Gynecol Oncol. 2020;31:e59. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Mottrie A. ERUS (EAU Robotic Urology Section) guidelines during COVID-19 emergency. EAU Robotic Urology Section [EAU website]. 2020. Available at: https://uroweb.org/eau-robotic-urology-section-erus-guidelines-during-covid-19-emergency/. Accessed November 20, 2020.

- 24.Navarra G, Komaei I, Currò G, et al. Bariatric surgery and the COVID-19 pandemic: SICOB recommendations on how to perform surgery during the outbreak and when to resume the activities in phase 2 of lockdown. Updates Surg. 2020;72:259–268. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Nugroho A, Arifin F, Widianto P, et al. Digestive Surgery Services in COVID-19 Pandemic Period: Indonesian Society of Digestive Surgeons Position Statement. J Indones Med Assoc. 2020;70:132–141. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Philippine Association of Laparoscopic and Endoscopic Surgeons. PALES Position Statement on Laparoscopic Surgery in COVID-19 Pandemic [PALES website]. 2020. Available at: www.pales.ph/pales-position-statement. Accessed November 20, 2020.

- 27.Porter J, Blau E, Gharagozloo F, et al. Society of Robotic Surgery review: recommendations regarding the risk of COVID-19 transmission during minimally invasive surgery. BJU Int. 2020;126:225–234. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Quaedackers JSLT, Stein R, Bhatt N, et al. Clinical and surgical consequences of the COVID-19 pandemic for patients with pediatric urological problems: Statement of the EAU guidelines panel for paediatric urology, March 30 2020. J Pediatr Urol. 2020;16:284–287. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Quaranta M, Dionisi H, Bonin M. The Argentine Society of Laparoscopic Surgery letter on COVID-19. J Minim Invasive Gynecol. 2020;27:1214–1215. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ramos RF, Lima DL, Benevenuto DS. Recommendations of the Brazilian College of Surgeons for laparoscopic surgery during the COVID-19 pandemic. Rev Col Bras Cir. 2020;47:e20202570. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Intercollegiate General Surgery Guidance on COVID-19 UPDATE [Royal College of Surgeons of Edinburgh website]. 2020. Available at: www.rcsed.ac.uk/news-public-affairs/news/2020/march/intercollegiate-general-surgery-guidance-on-covid-19-update. Accessed November 20, 2020.

- 32.Ribal MJ, Cornford P, Briganti A, et al. On behalf of the EAU Section Offices and the EAU Guidelines Panels European Association of Urology Guidelines Office Rapid Reaction Group. An Organisation-wide Collaborative Effort to Adapt the European Association of Urology Guidelines Recommendations to the Coronavirus Disease 2019 Era. Eur Urol. 2020;78:21–28. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Saftoiu A, Tomulescu V, Tanåãu M, et al. SRED-ARCE Recommendations for Minimally Invasive Interventions During the COVID-19 Pandemic in Romania. Chirurgia (Bucur). 2020;115:289–306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Southern African Society of Reproductive Medicine and Gynecologic Ensdoscopy. SASREG Guidance for Endoscopic Surgery during COVID-19 [SASREG website]. 2020. Available at: https://sasreg.co.za/guidance-for-endoscopic-surgery-during-covid-19-6-april-2020/. Accessed November 20, 2020.

- 35.Shabbir A, Menon RK, Somani J, et al. ELSA recommendations for minimally invasive surgery during a community spread pandemic: a centered approach in Asia from widespread to recovery phases. Surg Endosc. 2020;34:3292–3297. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Sharma S, Saha S. Pediatric surgery in India amidst the Covid-19 pandemic-best practice guidelines from Indian association of pediatric surgeons. J Indian Assoc Pediatr Surg. 2020;25:343–348. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Srivastava A, Nasta AM, Pathania BS, et al. Surgical practice recommendations for minimal access surgeons during COVID 19 pandemic - Indian inter-society directives. J Minim Access Surg. 2020;16:195–200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Stabilini C, East B, Fortelny R, et al. European Hernia Society (EHS) guidance for the management of adult patients with a hernia during the COVID 19 pandemic. Hernia. 2020;24:977–983. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Thomas V, Maillarda C, Barnarda A, et al. International Society for Gynecologic Endoscopy (ISGE) guidelines and recommendations on gynecological endoscopy during the evolutionary phases of the SARS-CoV-2 pandemic. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 2020;253:133–140. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Urological Society of Australia and New Zealand. Case Deferral, Laparoscopy and virtual meetings during COVID19 pandemic [USANZ website]. 2020. Available at: https://usanz.org.au/publicassets/f251dec1-9b82-ea11-90fb-0050568796d8/Pol-023-Guidelines---Laparoscopy-Case-Deferral-During-COVID--Final.pdf. Accessed November 20, 2020.

- 41.Eubanks S, Newman L, Lucas G. Reduction of HIV transmission during laparoscopic procedures. Surg Laparosc Endosc. 1993;3:2–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Wang WN, Melkonian MG, Marshall R, et al. Postgraduate year does not influence operating time in laparoscopic cholecystectomy. J Surg Res. 2001;101:1–3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Kauvar DS, Braswell A, Brown BD, et al. Influence of resident and attending surgeon seniority on operative performance in laparoscopic cholecystectomy. J Surg Res. 2006;15:159–163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Kaulfuss JC, Kluth LA, Marks P, et al. Long-term effects of mental training on manual and cognitive skills in surgical education—a prospective study. J Surg Educ. 2021;78:1216–1226. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Van Ginkel MPH, Schijven MP, van Grevenstein WMU, et al. Bimanual fundamentals: validation of a new curriculum for virtual reality training of laparoscopic skills. Surg Innov. 2020;27:523–533. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Köckerling F. Robotic vs. standard laparoscopic technique – what is better? Front Surg. 2014;1:15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Roh CK, Choi S, Seo WJ, et al. Comparison of surgical outcomes between integrated robotic and conventional laparoscopic surgery for distal gastrectomy: a propensity score matching analysis. Sci Rep. 2020;10:485. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Rohloff M, Peifer G, Shakuri-Rad J, et al. The impact of low pressure pneumoperitoneum in robotic assisted radical prostatectomy: a prospective, randomized, double blinded trial. World J Urol. 2020. doi: 10.1007/s00345-020-03486-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Matsuzaki S, Bonnin M, Fournet-Fayard A, et al. Effects of low intraperitoneal pressure on quality of postoperative recovery after laparoscopic surgery for genital prolapse in elderly patients aged 75 years or older. J Minim Invasive Gynecol. 2021;28:1072–1078.e3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Raval AD, Deshpande S, Koufopoulou M, et al. The impact of intra-abdominal pressure on perioperative outcomes in laparoscopic cholecystectomy: a systematic review and network meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Surg Endosc. 2020;3:2878–2890. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Rao AR. Re: Strategy for the practice of digestive and oncological surgery during the Covid-19 epidemic. J Visc Surg. 2020;157:363. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Tuech JJ. Strategy for the practice of digestive and oncological surgery during the Covid-19 epidemic. J Visc Surg. 2020;157(suppl 1):S7–S12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.La Chapelle CF, Bemelman WA, Rademaker BM, et al. A multidisciplinary evidence-based guideline for minimally invasive surgery: Part 1: entry techniques and the pneumoperitoneum. Gynecol Surg. 2012;9:271–282. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Feng Z, Feng DP, Solórzano CC. Useful modifications to the robotic posterior retroperitoneoscopic approach to adrenalectomy in severely obese patients. Ann Endosc Surg. 2017;2:145. [Google Scholar]

- 55.Grange P, Meyer C, Lauscher J, et al. Mitigating the impact of COVID on surgical skills—clinical service journal. 2021. [Epub ahead of print].

- 56.Sawchuk WS, Weber PJ, Lowy DR, et al. Infectious papillomavirus in the vapor of warts treated with carbon dioxide laser or electrocoagulation: detection and protection. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1989;21:41–49. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Kwak HD, Kim SH, Seo YS, et al. Detecting hepatitis B virus in surgical smoke emitted during laparoscopic surgery. Occup Environ Med. 2016;73:857–863. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Baggish MS, Poiesz BJ, Joret D, et al. Presence of human immunodeficiency virus DNA in laser smoke. Lasers Surg Med. 1991;11:197–203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Johnson GK, Robinson WS. Human immunodeficiency virus-1 (HIV-1) in the vapors of surgical power instruments. J Med Virol. 1991;33:47–50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Calero L, Brusis T. Laryngeal papillomatosis - first recognition in Germany as an occupational disease in an operating room nurse. Laryngorhinootologie. 2003;82:790–793. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Hallmo P, Naess O. Laryngeal papillomatosis with human papillomavirus DNA contracted by a laser surgeon. Eur Arch Otorhinolaryngol. 1991;248:425–442. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Morris SN, Nickles Fader A, et al. Understanding the “scope” of the problem: why laparoscopy is considered safe during the COVID-19 pandemic. J Minim Invasive Gynecol. 2020;27:789–791. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Hayami M, Watanabe M, Mine S, et al. Steam induced by the activation of energy devices under a wet condition may cause thermal injury. Surg Endosc. 2020;34:2295–2302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Nduka CC, Poland N, Kennedy M, et al. Is the ultrasonically activated scalpel release viable airborne cancer cells? Surg Endosc. 1998;12:1031–1034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.In SM, Park D-Y, Sohn IK, et al. Experimental study of the potential hazards of surgical smoke from powered instruments. Br J Surg. 2014;102:1581–1586. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Emam TA, Cuschieri A. How safe is high-power ultrasonic dissection? Ann Surg. 2003;237:186–191. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Dalli J, Khan MF, Nolan K, et al. Gas leaks through laparoscopic energy devices and robotic instrumentation - a video vignette. Colorectal Dis. 2020;22:2339–2340. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Nepple KG, Kallogjeri D, Bhayani SB. Benchtop evaluation of pressure barrier insufflator and standard insufflator systems. Surg Endosc. 2013;27:333–338. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Balayssac D, Selvy M, Martelin A, et al. Clinical and organizational impact of the AIRSEAL insufflation system during laparoscopic surgery: a systematic review. World J Surg. 2021;45:705–718. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Abaza R, Martinez O, Murphy C. Randomized controlled comparison of valveless trocar (AirSeal) vs standard insufflator with ultralow pneumoperitoneum during robotic prostatectomy. J Endourol. 2021;35:1020–1024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplemental Digital Content is available for this article. Direct URL citations appear in the printed text and are provided in the HTML and PDF versions of this article on the journal's website, www.surgical-laparoscopy.com.