Abstract

Background

When the vulnerabilities of the postnatal period are combined with the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic, psychosocial outcomes are likely to be affected. Specifically, we aim to: a) explore the psychosocial experiences of women in the early postnatal period; b) describe prevalence rates of clinically relevant maternal anxiety and depression; and c) explore whether psychosocial change occurring as a result of COVID-19 is predictive of clinically relevant maternal anxiety and depression.

Methods

A sample of UK mothers (N = 614) with infants aged between birth and twelve weeks were recruited via convenience sampling. A cross-sectional survey design was utilised which comprised demographics, COVID-19 specific questions, and a battery of validated psychosocial measures, including the EPDS and STAI-S which were used to collect prevalence rates of clinically relevant depression and anxiety respectively. Data collection coincided with the UK government's initial mandated “lockdown” restrictions and the introduction of social distancing measures in 2020.

Findings

Descriptive findings from the overall sample indicate that a high percentage of mothers self-reported psychological and social changes as a result of the introduction of social distancing measures. For women who reported the presence of psychosocial change, these changes were perceived negatively. Whilst seventy women (11.4%) reported a current clinical diagnosis of depression, two hundred and sixty-four women (43%) reported a score of ≥13 on the EPDS, indicating clinically relevant depression. Whilst one hundred and thirteen women (18.4%) reported a current clinical diagnosis of anxiety, three hundred and seventy-three women (61%) reported a score of ≥40 on STAI-S, indicating clinically relevant anxiety. After accounting for current clinical diagnoses of depression or anxiety, and demographic factors known to influence mental health, only perceived psychological change occurring as a result of the introduction of social distancing measures predicted unique variance in the risk of clinically relevant maternal depression (30%) and anxiety (33%).

Interpretation

To our knowledge, this is the first national study to examine the psychosocial experiences of postnatal women during the COVID-19 pandemic in the UK. Prevalence rates of clinically relevant maternal depression and anxiety were extremely high when compared to both self-reported current diagnoses of depression and anxiety, and pre-pandemic prevalence studies. Perceived psychological changes occurring as a result of the introduction of social distancing measures predicted unique variance in the risk for clinically relevant maternal depression and anxiety. This study provides vital information for clinicians, funders, policy makers, and researchers to inform the immediate next steps in perinatal care, policy, and research during COVID-19 and future health crises.

Keywords: Maternal mental health, Postpartum anxiety, Postpartum depression, Psycho-social experiences

1. Introduction

As of 23rd March 2020, UK government restrictions were introduced to reduce the spread of the Coronavirus (SARS-CoV-2) or COVID-19. Key measures included requiring people to stay at home, widespread closure of businesses and venues, and prohibition of all gatherings of more than two people in public (GOV.UK, 2020). The COVID-19 pandemic poses health risks to the whole population, but clinical risks for perinatal populations have so far only been classified in terms of the physical impact of getting the infection (Royal College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists, 2020). However, clinical risks are likely to extend beyond this given the effect of lockdown measures on psychological state and social interaction. Whilst most empirical studies are concerned with the impact of COVID-19 infection on direct pregnancy outcomes and vertical transmission(Lu et al., 2020), very few have considered the immediate risks of the pandemic on psychological and social experiences in the early postnatal period, and no published data from the UK is currently available.

The early postnatal period is already a period of heightened vulnerability to poor psychosocial outcomes. Emmanuel and St. John's concept analysis of 25 studies states that becoming a mother encompasses several psychosocial challenges which are consistent with other, more recent, empirical research (Emmanuel and St John, 2010). These include taking on a new maternal identity; body changes and functioning; increased demands and challenges; and navigating new social roles, including relationships with partners, healthcare professionals, and wider family (Clout and Brown, 2015; Feinberg et al., 2019). Maternal mental health is particularly important to consider, given that anxiety and depression are known to be more prevalent around childbearing age.(Baxter et al., 2014) It is estimated that as many as one in five women in a high-income country will develop a mental health related concern following the birth of their infant (Russell et al., 2017). Similarly, suicide is the leading cause of death in mothers of young infants (Knight et al., 2019; Rahman et al., 2013). The impact of poor maternal mental health is associated with short- and long-term risks for the affected mothers' overall health, functioning, quality of life, and social engagement. Maternal distress has also been consistently linked to a range of adverse developmental, somatic, and psychological outcomes in the infant (Thapa et al., 2020; Lonstein, 2007; Glasheen et al., 2009).

When the vulnerabilities of the postnatal period are combined with the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic, psychosocial outcomes are likely to be affected further (Matvienko-Sikar et al., 2020). Key psychosocial stressors include an inconsistent organisational response to COVID-19 in postnatal care and reduced in-person access to health and support services (Horsch et al., 2020); reduced social support from wider family and friends (McKinley, 2020); absence of birth partners and visitors after birth (Thapa et al., 2020); and restrictions to mother-infant contact and infant feeding care(Royal College of Paediatrics and Child Health, 2020). A recent review of the psychological impact of quarantine found adverse psychological effects including post-traumatic stress symptoms, confusion, and anger (Brooks et al., 2020). Furthermore, the COVID-19 pandemic is anticipated to decrease access to mental health services and psychological or pharmacological treatment, which is likely to impact further on mental health (Davenport et al., 2020).

To date, only two empirical studies have been published specifically examining the psychological impact of COVID-19 on mothers (Davenport et al., 2020; Zanardo et al., 2020). A non-concurrent case-control study of mothers who gave birth in a COVID-19 ‘hotspot’ area in North Eastern Italy found the COVID-19 study group (n = 91) had significantly higher mean postnatal depression scores compared with a control group outside of the pandemic (Zanardo et al., 2020). Another Canadian cross-sectional survey study of mothers of children from birth to eight years old (N = 642) found clinically relevant depression and anxiety was indicated in 44% and 30% of mothers during quarantine measures, respectively (Davenport et al., 2020). However, neither of these studies asked questions to examine whether, and how much, self-reported psychosocial outcomes have changed as a direct result of COVID-19. This means the psychological states reported by participants cannot be directly attributed to the pandemic.

This rapid-response cross-sectional online survey study aims to explore the psychosocial experiences of UK women in the early postnatal period (birth to twelve weeks postpartum) during initial government “lockdown” restrictions in the COVID-19 pandemic. Data was collected between 16th April and 15th May 2020 which coincided with the UK government's mandated guidance. Specifically, we aim to: a) describe prevalence rates of clinically relevant maternal anxiety and depression; and b) explore whether psychosocial change occurring as a result of COVID-19 is predictive of clinically relevant maternal anxiety and depression.

2. Method

2.1. Participants and recruitment

A sample of UK mothers with infants aged between birth and twelve weeks were recruited via convenience sampling to complete an on-line survey. Participants were recruited through social media platforms (e.g. Twitter, Facebook, Instagram) via an advertisement (not paid or targeted) providing a link to the Qualtrics survey platform. Participant inclusion criteria were: Over 18 years of age, UK-resident, English-speaking, and with a baby of 0–12 weeks. All data were collected from participants between 16th April and 15th May 2020 which coincided with the UK government's initial mandated “lockdown” restrictions and the introduction of social distancing measures (GOV.UK, 2020).

2.2. Design and procedure

A cross-sectional survey design was used. Prior to participation, an electronic information sheet and consent form were provided with a tick-box to confirm consent. At the end of the survey, participants were provided with a full electronic debrief with signposting to relevant support information, and were entered into a £25 prize draw.

2.3. The survey

A screening question was first asked to ascertain whether the participant was mother to a baby aged between birth and twelve weeks. Maternal-related demographic questions were asked at the beginning of the survey and specific questions were also asked on the incidence of COVID-19 in the mother and any family members (Table 1 ). This was followed by infant-related demographic questions (Table 2 ).

Table 1.

Maternal and COVID-19 characteristics (N = 614).

| Maternal Characteristic | Value | Current Diagnosis of Depression (N/%) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Maternal age (mean years ± SD) | 30.9 (5.1) | Yes | 70 (11.4) |

| Ethnicity (N/%) | No | 542 (88.3) | |

| White | 589 (95.9) | Prefer not to say | 2 (0.3) |

| Pakistani | 2 (0.3) | Current Diagnosis of PTSD (N/%) | |

| Black African | 2 (0.3) | Yes | 24 (3.9) |

| Chinese | 1 (0.2) | No | 586 (95.4) |

| Indian | 5 (0.8) | Prefer not to say | 4 (0.7) |

| Other | 13 (2.1) | ||

| Prefer not to say | 2 (0.3) | ||

| Marital Status (N/%) | COVID-19 Characteristic |

Value |

|

| Married | 350 (57.0) | Suspected COVID (N%) | |

| Co-habiting | 231 (37.6) | Yes | 42 (2.4) |

| Single | 30 (4.9) | No | 572 (97.6) |

| Separated/Divorced/Widowed | 3 (0.6) | Tested for COVID (N%) | |

| Occupation (N/%) | Yes | 1 (2.4) | |

| Managers, Directors and Senior Officials | 55 (9.0) | No | 41 (97.6) |

| Professionals | 258 (42.0) | Family member suspected COVID (N%) | |

| Associate Professionals and Technical | 16 (2.6) | Yes | 107 (17.4) |

| Administrative and Secretarial | 62 (10.1) | No | 507 (82.6) |

| Skilled Trade | 18 (2.9) | Family member tested for COVID (N%) | |

| Caring, Leisure and Other Service | 78 (12.7) | Yes | 10 (9.3) |

| Sales and Customer Service | 57 (9.3) | No | 97 (90.7) |

| Process, Plant and Machine Operatives | 1 (0.2) | Birth experience affected by COVID (N%) | |

| Elementary | 7 (1.1) | Yes | 200 (32.6) |

| Not in Paid Occupation | 62 (10.1) | No | 489 (67.4) |

| Education Attainment (N/%) | |||

| Postgraduate education | 150 (24.4) | ||

| Undergraduate education | 248 (40.4) | ||

| A-Levels or college equivalent | 132 (21.5) | ||

| GCSEs or secondary school equivalent | 66 (10.7) | ||

| No qualifications | 5 (0.8) | ||

| Other qualification | 13 (2.1) | ||

| Living Status (N/%) | |||

| Own property | 397 (64.7) | ||

| Rent privately | 130 (21.2) | ||

| Rent from local authority | 53 (8.6) | ||

| Live with parents | 28 (4.6) | ||

| Other | 6 (1.0) | ||

| Household Size (inc. participant) (N/%) | |||

| 2 people | 29 (4.7) | ||

| 3 people | 262 (42.7) | ||

| 4 people | 225 (36.6) | ||

| 5 people | 67 (10.9) | ||

| 6 or more people | 31 (5.0) | ||

| Current Diagnosis of Anxiety (N/%) | |||

| Yes | 113 (18.4) | ||

| No | 499 (81.3) | ||

| Prefer not to say | 2 (0.3) | ||

Table 2.

Infant characteristics (N = 614).

| Infant Characteristic | Value |

|---|---|

| Infant age (mean weeks ± SD) | 7.0 (3.6) |

| Birth order (N/%) | |

| 1st | 299 (38.6) |

| 2nd | 237 (8.5) |

| 3rd | 52 (2.4) |

| 4th | 15 (2.5) |

| 5th and after | 2 (0.3) |

| Timing of birth (N/%) | |

| Premature (<37 weeks) | 45 (7.4) |

| Early Term (>37 < 39 weeks) | 119 (19.4) |

| Full Term (>39 < 41 weeks) | 320 (52.1) |

| Late Term (>41 < 42 weeks) | 127 (20.7) |

| Post Term (>42 weeks) | 3 (0.5) |

| Multiple birth (N/%) | |

| Yes | 7 (1.1) |

| No | 607 (98.9) |

| Mode of delivery (N/%) | |

| Vaginal (without medical intervention) | 316 (51.5) |

| Elective caesarean section | 113 (18.4) |

| Emergency caesarean section | 112 (18.2) |

| Vaginal birth (assisted delivery) | 73 (11.9) |

| Feeding initiation after birth (N/%) | |

| Exclusively breastfeeding (100%) | 424 (69.1) |

| Predominantly breastmilk (over 80%) with a little formula milk (20%) | 56 (9.1) |

| Mainly breastmilk (50–80%) with some formula milk | 10 (1.6) |

| A combination of both breastmilk (50%) and formula milk (50%) | 30 (4.9) |

| Mainly formula milk (50–80%) with some breastmilk | 9 (1.5) |

| Predominantly formula milk (over 80%) with a little breastmilk (20%) | 17 (2.9) |

| Exclusively formula feeding (100%) | 68 (11.1) |

| Current feeding method (N/%) | |

| Exclusively breastfeeding (100%) | 340 (55.4) |

| Predominantly breastmilk (over 80%) with a little formula milk (20%) | 61 (9.9) |

| Mainly breastmilk (50–80%) with some formula milk | 19 (3.81) |

| A combination of both breastmilk (50%) and formula milk (50%) | 15 (2.4) |

| Mainly formula milk (50–80%) with some breastmilk | 20 (3.3) |

| Predominantly formula milk (over 80%) with a little breastmilk (20%) | 12 (2.0) |

| Exclusively formula feeding (100%) | 147 (23.9) |

2.4. Validated psychological measures

2.4.1. Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale (EPDS) (Cox et al., 1987)

The EPDS is a 10-item self-report questionnaire administered to screen for depressive symptoms in the postnatal period. It is the most widely used screening scale for postnatal depression. Higher scores indicate higher levels of depression. A clinical cut-off score of ≥13 identifies scores consistent with major depressive disorder, although the self-report measure does not replace a clinical diagnosis (Cox et al., 1987). In the current study, the scale had excellent reliability (McDonald's ω = 0.90).

2.4.2. State-Trait Anxiety Inventory – State scale (STAI-S) (Spielberger et al., 1970)

The STAI-S is a self-report measure designed to capture levels of general anxiety. It contains 20 items to measure situational (state) anxiety. Higher scores indicate higher levels of anxiety. A cut-off score of ≥40 on the STAI administered early in the postpartum period is recommended to detect clinically relevant symptoms of anxiety (Dennis et al., 2013). Reliability for the measure was excellent (McDonald's ω = 0.96).

2.4.3. Postpartum Specific Anxiety Scale - Research Short Form - for global Crises (PSAS-RSF-C)(Silverio et al., 2021)

The PSAS (Fallon et al., 2016) is a 51-item validated measure of postpartum specific anxiety designed to capture the frequency of maternal and infant focused anxieties experienced during the past week. Higher scores indicate higher levels of anxiety. For the purposes of this study, the top three factor loading items from each factor of the original measure were used as a 12-item short form to minimise participant burden (Silverio et al., 2021). The scale had good reliability (McDonald's ω = 0.83).

2.4.4. Parenting Sense of Competence scale (PSOC) (Gibaud-Wallston and Wandersmann, 1978)

The PSOC is a commonly used measure of parental self‐efficacy, with 7-items and 2-subscales. Each item is rated on a 6-point Likert scale scored as 1 = “Strongly Disagree” and 6 = “Strongly Agree”. A higher score indicates a higher parenting sense of competency. Reliability in the current study was good (McDonald's ω = 0.89).

2.5. Validated social measures

2.5.1. Relationship Questionnaire (RQ) (Figueiredo et al., 2008)

The RQ is comprised of 12-items on a four-point Likert scale, ranging from 1 (“Never”) to 4 (“Always”). This questionnaire assesses both the positive and negative dimensions of partner relationships. The higher the RQ total score, the better the couple relationship, as assessed by the participant. The scale had good reliability (McDonald's ω = 0.89).

2.5.2. Multidimensional Scale of Perceived Social Support (MSPSS) (Zimet et al., 1988)

The MSPSS is a brief questionnaire designed to measure perceptions of informal support from three sources: family, friends, and a significant other. The scale is comprised of a total of 12-items, with 4-items for each subscale. Higher scores indicate higher levels of social support. Reliability in the current study was excellent (McDonald's ω = 0.93).

2.5.3. The Short Assessment of Patient Satisfaction (SAPS) (Hawthorne et al., 2014)

The SAPS is a short, reliable, and valid 7-item scale which can be used to assess patient satisfaction with their care. It assesses the core domains of patient satisfaction which include provision of care, explanation of treatment results, clinician engagement and care, participation in medical decision making, and satisfaction with hospital/clinic care. Reliability in the current study was good (McDonald's ω = 0.88).

2.5.4. Mother-to-Infant Bonding Scale (MIBS) (Taylor et al., 2005)

The MIBS was designed with the intention of screening the general postpartum population. It is a brief, 8-item measure of mother-infant bond with established criterion and construct validity. Higher scores indicate worse mother-infant bonding. Reliability in the current study was good (McDonald's ω = 0.79).

2.6. COVID-19 specific items

At the end of each validated measure, two COVID-19-specific items were asked. The first asked “Have your feelings of [psychological or social variable] changed since the introduction of social distancing measures?” with “Yes”, “No”, and “Prefer Not To Say” response options. For those that indicated “Yes” to the first question, a second question was displayed which asked: “Please state how much this has changed since the introduction of social distancing measures” on a 10-point Likert-Scale with zero as neutral from “I feel much less” [psychological or social variable] “I feel much more” [psychological or social variable]”.

2.7. Statistical analyses

Descriptive analyses for the demographic, psychological, social, and COVID-19-specific measures were conducted (Table 1, Table 2, Table 3 ). Means were then compared to data published by members of the authorship team from research conducted before the COVID-19 pandemic, which used matched recruitment methods and had similar sample characteristics (Fallon et al., 2019). The study selected was conducted in 2016, recruited postpartum mothers of infants between birth and six months (N = 800) online and administered the EPDS and STAI-S alongside a battery of measures (Fallon et al., 2019). Independent two-sample t-tests were conducted to examine whether the current sample had significantly different depression (EPDS) and anxiety (STAI-S) means to the selected pre-pandemic study (Fallon et al., 2019). Descriptive analyses were then conducted to identify prevalence rates of depression (EPDS) and anxiety (STAI-S). Depressive and anxious symptoms above and below cut-off scores on each measure were recoded into dichotomous measures indicating clinically relevant levels. The prevalence of clinically relevant depression and anxiety was then compared to meta-analytic prevalence reviews of postpartum depression and anxiety (Hahn-Holbrook et al., 2018; Dennis et al., 2017). Bivariate correlations were conducted to identify relationships between variables to inform inferential analyses. Binomial hierarchical logistic regression models were then built to examine whether a change (yes/no) in psychosocial experiences as a result of the introduction of social distancing measures affected risk for clinically relevant, maternal depression and anxiety. Self-reported, current, clinical diagnoses of anxiety and depression were controlled for in Block 1 of the regression; socio-demographic predictors were included in Block 2; and psychosocial changes occurring as a result of the introduction of social distancing measures were added in Block 3.

Table 3.

Descriptive statistics, statistical comparisons of means with pre-pandemic studies, and COVID-19 specific change.

| Psychological Variable | Current Study Mean (SD) | Study comparison mean/SD | Independent two sample t-test and p value |

|---|---|---|---|

| EPDS | 11.56 (5.90) | 9.13 (5.72) Fallon et al. (2019) |

7.77; p < .001 |

| STAI-S | 45.26 (13.69) | 37.70 (±13.45) Fallon et al. (2019) |

10.04, p < .001 |

| PSAS-S | 24.79 (6.19) | ||

| PSOC | 69.72 (12.13) | ||

| Social Variable | |||

| RQ | 36.07 (5.81) | ||

| MSPSS | 67.91 (13.36) | ||

| MIBS | 3.52 (3.77) | ||

| SAPS | 19.44 (5.71) | ||

| COVID-19 specific change | (N/% change occurred = (yes) | How was change experienced (mean/SD; −5 positive change to +5 negative change) | |

| EPDS | 376 (62) | 2.67 (1.79) | |

| STAI | 535 (87) | 2.31 (1.97) | |

| PSAS | 388 (63) | 2.88 (1.78) | |

| PSOC | 297 (49) | 2.05 (1.90) | |

| RQ | 262 (45) | 1.13 (2.36) | |

| MSPSS | 341 (56) | 3.36 (2.06) | |

| MIBS | 118 (19) | 1.70 (2.31) | |

| SAPS | 229 (37) | 2.17 (2.48) |

3. Results

3.1. Participants

Mothers with infants aged between birth and twelve weeks (N = 614) consented to take part in the survey, with a 100% of those who consented, completing the survey. Maternal age ranged between 18 and 46 years (M = 30.88, SD = 5.06) and infant age ranged between birth and twelve weeks (M = 7.00, SD = 3.64). Women were predominantly white (96%), married (57%), university educated (61%), and professionals (42%). Forty-two women believed they had COVID-19 symptoms (7%), with one of these women having been tested. Additionally, 107 women believed a family member had COVID-19 (17%), with ten of these women reporting their family member had been tested. Finally, 200 women reported their birth experience had been affected by the introduction of social distancing measures (33%).

3.2. Psychosocial experiences during COVID-19

Descriptive statistics for the psychological measures (EPDS; STAI-S; PSAS-RSF-C; PSOC) and social measures (RQ; MSSPS; SAPS; MIBS) can be found in Table 3. There was a significant difference in the EPDS scores in the current study (M = 11.56, SD = 5.90) compared to the EPDS scores in the pre-pandemic study selected (M = 9.13, SD = 5.72); t(1393) = 7.77 p<..001. There was also a significant difference in the STAI-S scores in the current study (M = 45.26, SD = 13.69) compared to the STAI-S scores in the pre-pandemic study selected (M = 37.69, SD = 13.45); t(1296) = 10.04, p<.001.

3.3. COVID-19 specific changes in psychosocial experiences

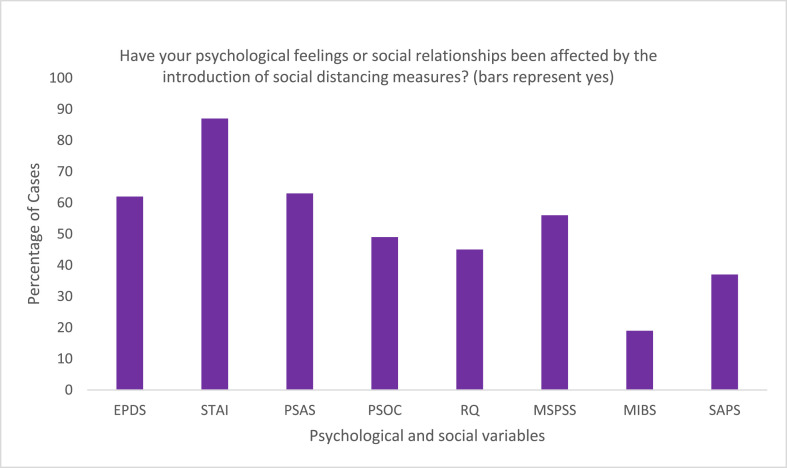

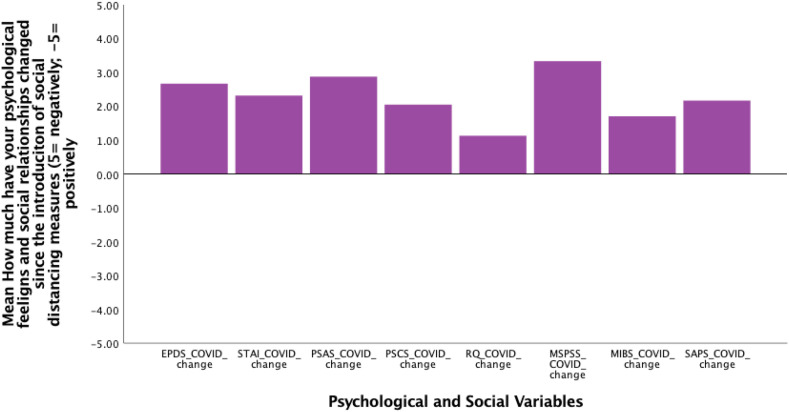

Participants reported whether a change in psychological state had occurred as a direct result of social distancing measures; 376 (62%) of women indicated their feelings of depression had changed; 535 (87%) of women reported their feelings of anxiety had changed; 388 (63%) of women indicated their feelings of motherhood-related anxiety had changed; and 297 (48%) of women felt their feelings towards parenting competence had changed. Of those who indicated change occurred, it was felt their levels of depression (M = 2.67; SD = 1.79), anxiety (M = 2.31; SD = 1.97), and motherhood-related anxiety (M = 2.88; SD = 1.78) had increased; whilst reporting feeling less confident in their parenting skills (M = 2.05; 1.90). Women then reported whether a change in their social environment had occurred as a direct result of ‘social distancing’: 262 (45%) reported a change in their relationship with their partner; 341 (56%) reported a change in social support; 229 (38%) reported a change in satisfaction towards healthcare; and 118 (19%) reported a change in how they felt towards their baby. Of those who indicated change occurred, it was reported their relationship with their partner (M = 1.13; SD = 2.36); levels of social support (M = 3.36; SD = 2.06); satisfaction towards their healthcare (M = 2.17; SD = 2.48), and feelings towards their baby (M = 1.70; SD = 2.31), had all changed negatively as a result of social distancing measures (see Fig. 1, Fig. 2 ).

Fig. 1.

Percentage of women who felt their psychological state and social relationships had been affected by the introduction of social distancing measures.

Fig. 2.

Level of psychological and social change occurring as a result of the introduction of social distancing measures.

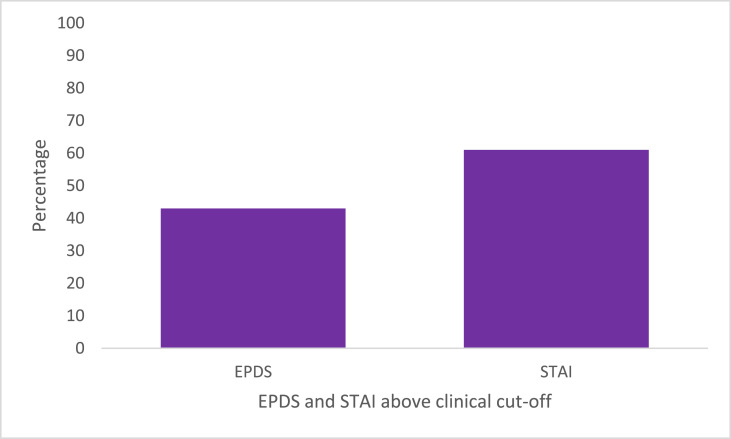

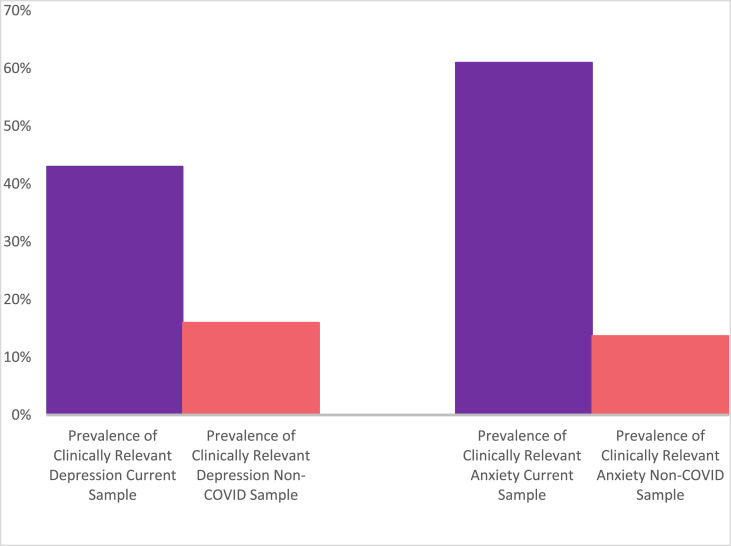

3.4. Prevalence of maternal depression

Seventy women (11.4%) reported a current clinical diagnosis of depression, although two hundred and sixty-four women (43%) reported a score of ≥13 on the EPDS which indicates clinically relevant depression (see Fig. 3 ). Mean EPDS scores for those who reported a score of ≥13 were M = 17.15 (SD = 3.45). Mean scores for those who did not meet the clinical cut-off were M = 7.33 (SD = 3.25). Prevalence of clinically relevant maternal depression in the current study compared to pre-pandemic population prevalence rates can be seen in Fig. 4 (Hahn-Holbrook et al., 2018).

Fig. 3.

Percentage of mothers scoring above the clinical cut-off on the EPDS (13 and above) and the STAI (40 and above).

Fig. 4.

Prevalence of clinically relevant depression and anxiety compared to pre-pandemic prevalence meta-analytic reviews *†

*Depression prevalence (EPDS) compared to a meta-analytic review of 16 studies (N =

49,446) examining national postpartum depression prevalence in the UK (EPDS; prevalence estimate used =

16%, Hahn-Holbrook et al., 2018)

†Anxiety prevalence (predominately STAI-S) compared to a meta-analytic review of 34 studies from high-income countries (N = 143,134; 4 UK studies) (STAI-S; prevalence estimate used = 13.7% Dennis et al., 2017).

3.5. Prevalence of maternal anxiety

One hundred and thirteen women (18.4%) reported a current clinical diagnosis of anxiety, although three hundred and seventy-three women (61%) reported a score of ≥40 on STAI-S indicating clinically relevant anxiety (See Fig. 3). Mean STAI-S scores for those who reported a score of ≥40 were M = 54.25 (SD = 8.98). Mean scores for those who did not meet the clinical cut-off were M = 33.31 (SD = 5.80). Prevalence of clinically relevant maternal anxiety in the current study compared to pre-pandemic population prevalence rates can be seen in Fig. 4 (Dennis et al., 2017).

3.6. Hierarchical binary logistic regression examining sociodemographic factors and psychosocial change as a result of the introduction of social distancing measures as risk factors for clinically relevant maternal depression

The final regression model significantly predicted clinically relevant depression (EPDS scores ≥13), correctly identifying 76.1% of cases: Cox and Snell R2 = .32, Nagelkerke R2 = .43, p < .001. Presence of a current clinical diagnosis of depression and anxiety in step 1 explained approximately 8% (Cox and Snell) and 10% (Nagelkerke) of the variance in risk of clinically relevant depression. Socio-demographic predictors in step 2 (maternal age; occupation; education; and percentage of formula milk used) explained an additional 1% (Cox and Snell) and 3% (Nagelkerke) of the variance. Only increased use of formula milk was significantly associated with risk of clinically relevant depression (AOR: 1.08; 95% CI: 1.01–1.16). In step 3, the psychosocial change variables explained an additional 23% (Cox and Snell) and 30% (Nagelkerke) of the variance. Presence of change in feelings of depression (AOR: 0.15; 95% CI: 0.09–0.26), motherhood specific anxiety (AOR: 0.43; 95% CI: 0.25–0.73), and parenting competence (AOR: 0.51; 95% CI: 0.32–0.81) as a result of the introduction of social distancing measures, were all significantly associated with risk of clinically relevant depression (see Table 4 ).

Table 4.

Hierarchical Logistic Regression examining sociodemographic factors and psychosocial change as a result of the introduction of social distancing measures as risk factors for clinically relevant maternal depression and anxiety.

| Clinically relevant depressiona | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variables | Step 1 |

Step 2 |

Step 3 |

||||||

| B(SE) | OR | 95% CI | B(SE) | OR | 95% CI | B(SE) | OR | 95% CI | |

| Step 1 | |||||||||

| Current diagnosis of depression (yes/no) | −1.24 (.37) | 0.29 | 0.14–0.60 | −1.19 (.38) | 0.30 | 0.15–0.63 | −1.04 (.44) | 0.35 | 0.15–0.83 |

| Current diagnosis of anxiety (yes/no) | -.82 (.27) | 0.44 | 0.26–0.75 | -.73 (.28) | 0.48 | 0.28–0.84 | -.45 (.33) | 0.63 | 0.33–1.22 |

| Step 2 | |||||||||

| Maternal age | .00 (.02) | 1.00 | 0.96–1.04 | -.01 (.02) | 0.99 | 0.95–1.04 | |||

| Occupation | .03 (.04) | 1.03 | 0.95–1.11 | .04 (.05) | 1.04 | 0.95–1.14 | |||

| Education | .11(.10) | 1.16 | 0.92–1.35 | .07 (.11) | 1.08 | 0.86–1.33 | |||

| % of formula milk used | .08 (.04) | 1.08 | 1.01–1.16 | .11 (.04) | 1.12 | 1.03–1.21 | |||

| Step 3* | |||||||||

| Change in depression (absent/present) | −1.87 (.26) | 0.15 | 0.09–0.26 | ||||||

| Change in anxiety (absent/present) | .20 (.42) | 1.22 | 0.53–2.82 | ||||||

| Change in postpartum specific anxiety (absent/present) | -.84 (.27) | 0.43 | 0.25–0.73 | ||||||

| Change in parenting competence (absent/present) | -.67 (.23) | 0.51 | 0.32–0.81 | ||||||

| Change in relationship quality (absent/present) | -.36 (.22) | 0.70 | 0.45–1.08 | ||||||

| Change in social support (absent/present) | -.11 (.24) | 0.90 | 0.56–1.43 | ||||||

| Change in satisfaction with care (absent/present) | -.23 (.23) | 0.70 | 0.46–1.08 | ||||||

| Change in mother to infant bonding (absent/present) |

-.30 (.28) |

0.74 |

0.43–1.28 |

||||||

|

Clinically relevant anxietyb | |||||||||

| Step 1 | |||||||||

| Current diagnosis of anxiety (yes/no) | −1.17 (.32) | 0.31 | 0.14–0.60 | -.11 (.33) | 0.34 | 0.18–0.64 | -.84 (.39) | 0.43 | 0.20–0.93 |

| Current diagnosis of depression (yes/no) | -.87 (.44) | 0.41 | 0.17–0.97 | -.80 (.45) | 0.45 | 0.19–1.07 | -.64 (.54) | 0.53 | 0.18–1.52 |

| Step 2 | |||||||||

| Maternal age (years) | -.01 (.02) | 0.99 | 0.95–1.03 | -.02 (.02) | 0.98 | 0.93–1.03 | |||

| Occupation | .02 (.04) | 1.02 | 0.95–1.10 | .05 (.05) | 1.05 | 0.96–1.16 | |||

| Education | .12 (.10) | 1.13 | 0.93–1.36 | .09 (.12) | 1.09 | 0.87–1.37 | |||

| Infant age (in weeks) | .05 (.03) | 1.05 | 1.00–1.10 | .04 (.03) | 1.04 | 0.98–1.11 | |||

| Step 3* | |||||||||

| Change in anxiety (absent/present) | −1.16 (.39) | 0.32 | 0.15–0.68 | ||||||

| Change in depression (absent/present) | −1.74 (.23) | 0.18 | 0.11–0.27 | ||||||

| Change in postpartum specific anxiety (absent/present) | -.70 (.25) | 0.49 | 0.30–0.81 | ||||||

| Change in parenting competence (absent/present) | -.52 (.24) | 0.59 | 0.37–0.95 | ||||||

| Change in relationship quality (absent/present) | -.13 (.23) | 0.88 | 0.56–1.39 | ||||||

| Change in social support (absent/present) | -.04 (.24) | 0.96 | 0.60–1.52 | ||||||

| Change in satisfaction with care (absent/present) | -.38 (.24) | 0.69 | 0.43–1.09 | ||||||

| Change in mother to infant bonding (absent/present) | .13 (.31) | 1.14 | 0.62–2.08 | ||||||

Note for depression analyses. R2 (block 3) = .32 (Cox & Snell); .43 (Nagelkerke). Step 1 block χ2 = 44.80, df = 2, p < .001. Step 2 block χ2 = 9.33, df = 4, p = .05. Step 3 block χ2 = 159.78, df = 8, p=<.001. SE = Standard Error. CI = confidence interval. Significant (p < .05) odds ratios (OR) are indicated in bold. Current diagnosis coded as 1 = yes and 2 = no; Presence of change coded as 0 = absent and 1 = present.

Note for anxiety analyses. R2 (block 3) = .33 (Cox & Snell); .43 (Nagelkerke). Step 1 block χ2 = 38.66, df = 2, p < .001. Step 2 block χ2 = 8.31, df = 4, p = .08. Step 3 block χ2 = 174.64, df = 8, p=<.001. SE = Standard Error. CI = confidence interval. Significant (p < .05) odds ratios (OR) are indicated in bold. Current diagnosis coded as 1 = yes and 2 = no; Presence of change coded as 0 = absent and 1 = present.

3.7. Hierarchical binary logistic regression examining sociodemographic factors and psychosocial change as a result of COVID-19 ‘lockdown’ as risk factors for clinically relevant maternal anxiety

The final regression model significantly predicted clinically relevant anxiety (STAI scores ≥ 40), correctly identifying 77.7% of cases: Cox and Snell R2 = .33, Nagelkerke R2 = .44, p < .001. Presence of a current clinical diagnosis of depression and anxiety in step 1 explained approximately 7% (Cox and Snell) and 9% (Nagelkerke) of the variance in risk of clinically relevant anxiety. Sociodemographic predictors in step 2 (maternal age; occupation; education; and infant age) explained an additional 2% (Cox and Snell) and 2% (Nagelkerke) of the variance. Only older infant age was significantly associated with risk of clinically relevant anxiety (AOR: 1.05; 95% CI: 1.01–1.11). In step 3, the psychosocial change variables explained an additional 24% (Cox and Snell) and 33% (Nagelkerke) of the variance. Presence of change in feelings of depression (AOR: 0.18; 95% CI: 0.11–0.27), anxiety (AOR: 0.32 95% CI: 0.15–0.68), motherhood specific anxiety (AOR: 0.49; 95% CI: 0.30–0.81), and parenting competence (AOR: 0.59; 95% CI: 0.37–0.95) as a result of the introduction of social distancing measures were all significantly associated with risk of clinically relevant anxiety (see Table 4).

4. Discussion

This study first aimed to explore the psychosocial experiences of UK women in the early postnatal period (birth to twelve weeks postpartum) during initial government ‘lockdown’ restrictions in the COVID-19 pandemic. Descriptive findings from the overall sample indicated a high percentage of mothers self-reported psychological and social changes as a result of the introduction of social distancing measures. Notably, the proportion of change in state anxiety was particularly high (87%) which likely reflects widespread situational concern about the immediate COVID-19 pandemic and associated social distancing measures. A recent editorial by WHO Director General, Tedros Adhanom Ghebreyesus stated: “fear from the virus is spreading even faster than the virus itself” (p129) (Adhanom Ghebreyesus, 2020). Common state anxieties specific to early motherhood may be around increased fear of the potential risk of infection or vertical transmission, restrictions in access to routine reproductive and maternity care, or separation from families and caregivers and wider networks of support (Adhanom Ghebreyesus, 2020; Diamond et al., 2020).

For women who reported presence of psychosocial change, these changes were perceived negatively. In particular, women felt much less socially supported. Informal support from partner, family, and friends is highly influential to women's experiences of early motherhood (Leigh-Hunt et al., 2017). During the pandemic, social support was severely limited due to the restrictions that have been put into place to reduce the risk of transmission of COVID-19 (The Lancet Psychiatry. Is, 2020). A recent review of reviews demonstrated significant associations between social isolation, loneliness and poorer mental health outcomes, such as depression (Leigh-Hunt et al., 2017).

The second aim of this study was to describe prevalence rates of clinically relevant maternal depression and anxiety. In this study, 43% of participants exceeded the cut-off for clinically relevant depression and 61% exceeded the cut-off for clinically relevant anxiety. When compared to those who disclosed a current, clinical diagnosis of depression (11.4%) or anxiety (18.4%), there is a large proportion of women who meet clinically relevant criteria but who have not received a formal diagnosis indicating a large prevalence-diagnosis gap. Similarly, when compared to the prevalence of clinically relevant depression and anxiety using the same measures in pre-pandemic cohorts (16% (Hahn-Holbrook et al., 2018) and 14.6% (Dennis et al., 2017) respectively), the rates within our study during the pandemic were far higher. Furthermore, decreased access to diagnosis and psychological or pharmacological treatment during the pandemic is likely to further exacerbate poor mental health (Davenport et al., 2020). It is well established that poor maternal mental health is associated with numerous detrimental outcomes for mother and infant (Knight et al., 2019; Rahman et al., 2013; Thapa et al., 2020; Lonstein, 2007; Glasheen et al., 2009). Together, these findings indicate an acute public health issue which requires urgent attention and intervention to improve the mental health of this population and associated outcomes. This reinforces the requirement for continued, comprehensive long-term monitoring of maternal mental health and maternal and infant psychosocial outcomes following the pandemic (Caparros-Gonzalez and Alderdice, 2020).

The final aim of this study was to explore whether psychosocial change occurring as a result of the introduction of social distancing measures was predictive of clinically relevant maternal depression and anxiety. After accounting for current clinical diagnoses of depression or anxiety, and demographic factors known to influence mental health, only perceived psychological change occurring as a result of the introduction of social distancing measures predicted unique variance in the risk of clinically relevant maternal depression (30%) and anxiety (33%). Interestingly, perceived social changes occurring as a result of the introduction of social distancing measures were not associated with increased risk. This suggests that it is perceived psychological changes occurring as a result of the pandemic which have acted as major stressors on maternal mental health and corroborates global work in this area (Davenport et al., 2020; Zanardo et al., 2020). We should therefore focus efforts on improving and maintaining access to perinatal mental health care services during this, and similar crises (Caparros-Gonzalez and Alderdice, 2020).

Due to the rapid development of COVID-19, this study was cross-sectional in nature and all comparisons to pre-pandemic data were obtained using already published cohorts, therefore precluding causality. Longitudinal research is essential in understanding the longer-term impact of the pandemic on maternal mental health and how this may affect maternal and infant outcomes. Another limitation of this study is its usage of an online convenience sample which, although adequately powered, lacked sampling control. As such, women were predominantly white, married, primiparous, educated to a tertiary level, and in a professional occupation. This may affect comparability of prevalence with the pre-pandemic meta-analytic reviews selected. With the SARS-CoV-2 coronavirus having a disproportionate effect on Black, Asian, and Minority Ethnic [BAME] communities, as well as those living with social complexity and/or deprivation (El-Khatib et al., 2020), it is vital to replicate this study in ethnically and socio-economically diverse populations. Finally, it is acknowledged that a proportion of data (14%) were collected very shortly after birth (i.e. zero – two weeks postpartum). As a consequence, some of these data may be influenced by factors such as transitory ‘baby blues’, negative/challenging birth experiences, or natural adaption to the challenges of new motherhood.

5. Conclusions and implications

This study provides a nationwide snapshot of psychosocial experiences in early motherhood during the COVID-19 pandemic in the UK and offers valuable, first insights into how psychosocial experiences have changed in relation to the introduction of social distancing measures. To date, this study is the only one to report the prevalence rates of clinically relevant maternal depression and anxiety in the UK during the pandemic. Furthermore, we offer unique insight into the predictors of clinically relevant maternal mental health, whilst accounting for pre-existing mental health diagnoses and sociodemographic confounders. This study provides vital information for clinicians, funders, policy makers, and researchers, to inform the immediate next steps in perinatal research, policy, and care during this, and future health crises. For policy makers and clinicians tasked with the provision and delivery of postnatal care, we echo previous calls for “proactive, multidisciplinary, integrated” (p817) (Thapa et al., 2020) approaches. For funders and researchers, there is a need for longitudinal research to address the acute and longer-term consequences of the pandemic on maternal mental health. From there, development and evaluation of psychosocial interventions to target poor mental health outcomes at different stages of the pandemic are required (Holmes et al., 2020). These must be developed with in-built flexibility to enhance applicability to future health crises. With consideration to our results we recommend that during the COVID-19 pandemic and future health crises, mental and physical health in postnatal populations is provided parity of esteem.

Author contribution

Conceptualization: Victoria Fallon.

Study Design: All authors.

Data Collection: Leanne Jackson, Siân M. Davies.

Data Analysis: Victoria Fallon, Siân M. Davies, Leonardo de Pascalis, Leanne Jackson.

Data Interpretation: All authors.

Writing: Victoria Fallon (lead).

All authors critically revised the manuscript and agreed to its publication.

Ethics

Ethical approvals were sought and granted from the University of Liverpool Research Ethics Committee [ref:- IPHS/7630].

Funding

This study received no funding.

Availability of data

All data is part of the common dataset for The PRegnancy And Motherhood during COVID-19 Study [The PRAM Study]. Applications to use these data in research are to be made formally by writing to the study's Chief Investigator: Dr. V. Fallon, University of Liverpool, V.Fallon@liverpool.ac.uk. All subsequent publications must state affiliation to The PRAM Study.

Declaration of competing interest

No conflicts of interest or competing interests have been declared by any author.

Acknowledgements

Sergio A. Silverio (King's College London) is supported by the National Institute for Health Research Applied Research Collaboration South London [NIHR ARC South London] at King's College Hospital NHS Foundation Trust. The views expressed are those of the authors and not necessarily those of the NIHR or the Department of Health and Social Care.

References

- Adhanom Ghebreyesus T. Addressing mental health needs: an integral part of COVID‐19 response. World Psychiatr. 2020;19(2):129–130. doi: 10.1002/wps.20768. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baxter A., Vos T., Scott K., Ferrari A., Whiteford H. The global burden of anxiety disorders in 2010. Psychol. Med. 2014;44(11):2363–2374. doi: 10.1017/s0033291713003243. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brooks S., Webster R., Smith L., et al. The psychological impact of quarantine and how to reduce it: rapid review of the evidence. Lancet. 2020;395(10227):912–920. doi: 10.2139/ssrn.3532534. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caparros-Gonzalez R., Alderdice F. The COVID-19 pandemic and perinatal mental health. J. Reprod. Infant Psychol. 2020;38(3):223–225. doi: 10.1080/02646838.2020.1786910. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clout D., Brown R. Sociodemographic, pregnancy, obstetric, and postnatal predictors of postpartum stress, anxiety and depression in new mothers. J. Affect. Disord. 2015;188:60–67. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2015.08.054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cox J.L., Holden J.M., Sagovsky R. Detection of postnatal depression: development of the 10-item Edinburgh postnatal depression scale. Br. J. Psychiatr. 1987;150(6):782–786. doi: 10.1192/bjp.150.6.782. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davenport M., Meyer S., Meah V., Strynadka M., Khurana R. Moms are not OK: COVID-19 and maternal mental health. Frontiers in Global Women’s Health. 2020;1(1):1–6. doi: 10.3389/fgwh.2020.00001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dennis C., Coghlan M., Vigod S. Can we identify mothers at-risk for postpartum anxiety in the immediate postpartum period using the State-Trait Anxiety Inventory? J. Affect. Disord. 2013;150(3):1217–1220. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2013.05.04. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dennis C.L., Falah-Hassani K., Shiri R. Prevalence of antenatal and postnatal anxiety: systematic review and meta-analysis. Br. J. Psychiatr. 2017;210(5):315–323. doi: 10.1192/bjp.bp.116.187179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Diamond R., Brown K., Miranda J. Impact of COVID-19 on the perinatal period through a biopsychosocial systemic framework. Contemp. Fam. Ther. 2020;42(3):205–216. doi: 10.1007/s10591-020-09544-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- El-Khatib Z., Jacobs G.B., Ikomey G.M., Neogi U. The disproportionate effect of COVID-19 mortality on ethnic minorities: genetics or health inequalities? EClinicalMedicine. 2020;23(100430):1–2. doi: 10.1016/j.eclinm.2020.100430. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Emmanuel E., St John W. Maternal distress: concept analysis. J. Adv. Nurs. 2010;66(9):2104–2115. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2648.2010.05371.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fallon V., Halford J., Bennett K., Harrold J. The postpartum specific anxiety scale: development and preliminary validation. Arch. Wom. Ment. Health. 2016;19(6):1079–1090. doi: 10.1007/s00737-016-0658-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fallon V., Silverio S.A., Halford J., Bennett K., Harrold J. Postpartum-specific anxiety and maternal bonding: further evidence to support the use of childbearing specific mood tools. J. Reprod. Infant Psychol. 2019:1–11. doi: 10.1080/02646838.2019.1680960. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feinberg M.E., Jones D.E., McDaniel B.T., Liu S., Almeida D. New fathers' and mothers' daily stressors and resources influence parent adjustment and family relationships. Monogr. Soc. Res. Child Dev. 2019;84(1):18–34. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Figueiredo B., Field T., Diego M., Hernandez‐Reif M., Deeds O., Ascencio A. Partner relationships during the transition to parenthood. J. Reprod. Infant Psychol. 2008;26(2):99–107. doi: 10.1080/02646830701873057. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Gibaud-Wallston J., Wandersmann L.P. Paper presented at the annual meeting of the American Psychological Association, Toronto, Canada. John F. Kennedy Center for Research on Education and Human Development; 1978. Development and utility of the Parenting Sense of Competence Scale. [Google Scholar]

- Glasheen C., Richardson G., Fabio A. A systematic review of the effects of postnatal maternal anxiety on children. Arch. Wom. Ment. Health. 2009;13(1):61–74. doi: 10.1007/s00737-009-0109-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- GOV.UK Staying at home and away from others (social distancing) 2020. https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/full-guidance-on-staying-at-home-and-away-from-others Published March 23, 2020. Accessed July 5.

- Hahn-Holbrook J., Cornwell-Hinrichs T., Anaya I. Economic and health predictors of national postpartum depression prevalence: a systematic review, meta-analysis, and meta-regression of 291 studies from 56 countries. Front. Psychiatr. 2018;8(248):1–23. doi: 10.3389/fpsyt.2017.00248. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hawthorne G., Sansoni J., Hayes L., Marosszeky N., Sansoni E. Measuring patient satisfaction with health care treatment using the Short Assessment of Patient Satisfaction measure delivered superior and robust satisfaction estimates. J. Clin. Epidemiol. 2014;67(5):527–537. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2013.12.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holmes E.A., O'Connor R.C., Perry V.H., et al. Multidisciplinary research priorities for the COVID-19 pandemic: a call for action for mental health science. Lancet Psychiatr. 2020;7(6):547–560. doi: 10.1016/S2215-0366(20)30168-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Horsch A., Lalor J., Downe S. Moral and mental health challenges faced by maternity staff during the COVID-19 pandemic. Psychological Trauma: Theory, Research, Practice, and Policy. 2020;12(S1):S141–S142. doi: 10.1037/tra0000629. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Knight M., Bunch K., Tuffnell D., Shakespeare J., Kotnis R., Kenyon S., Kurinczuk J.J., editors. Saving Lives, Improving Mothers' Care - Lessons Learned to Inform Maternity Care from the UK and Ireland Confidential Enquiries into Maternal Deaths and Morbidity 2015-17. National Perinatal Epidemiology Unit, University of Oxford; Oxford: 2019. On behalf of MBRRACE-UK. [Google Scholar]

- Leigh-Hunt N., Bagguley D., Bash K., et al. An overview of systematic reviews on the public health consequences of social isolation and loneliness. Publ. Health. 2017;152:157–171. doi: 10.1016/j.puhe.2017.07.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lonstein J. Regulation of anxiety during the postpartum period. Front. Neuroendocrinol. 2007;28(2–3):115–141. doi: 10.1016/j.yfrne.2007.05.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lu D., Sang L., Du S., Li T., Chang Y., Yang X.A. Asymptomatic COVID-19 infection in late pregnancy indicated no vertical transmission. J. Med. Virol. 2020;92(9):1660–1664. doi: 10.1002/jmv.25927. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matvienko-Sikar K., Meedya S., Ravaldi C. Perinatal mental health during the COVID-19 pandemic. Women Birth. 2020;33(4):309–310. doi: 10.1016/j.wombi.2020.04.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McKinley G. We need each other: social supports during COVID 19. Soc. Anthropol. 2020;28(2):319–320. doi: 10.1111/1469-8676.12828. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rahman A., Surkan P., Cayetano C., Rwagatare P., Dickson K. Grand challenges: integrating maternal mental health into maternal and child health programmes. PLoS Med. 2013;10(5):1–7. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1001442. e1001442. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Royal College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists Coronavirus (COVID-19) infection in pregnancy. https://www.rcog.org.uk/globalassets/documents/guidelines/2020-07-24-coronavirus-covid-19-infection-in-pregnancy.pdf Updated Friday 24 July, 2020. Accessed, August 10, 2020.

- Royal College of Paediatrics and Child Health . RCPCH; 2020. https://www.rcpch.ac.uk/sites/default/files/2020-06/optimising_mother_baby_contact_and_infant_feeding_in_a_pandemic_version_2_final_24th_june_2020.pdf [online] Available at. Accessed 13 August 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Russell K., Ashley A., Chan G., Gibson S., Jones R. Maternal mental health—women’s voices. 2017. https://www.rcog.org.uk/globalassets/documents/patients/information/maternalmental-healthwomens-voices.pdf Rcog.org.uk. Published 2020. Accessed July 23, 2020.

- Silverio S.A., Davies S.M., Christiansen P., Aparicio-García M.E., Bramante A., Chen P., Costas-Ramón N., de Weerth C., Della Vedova A.M., Infante Gil L., Lustermans H., Wendland J., Xu J., Halford J.C.G., Harrold J.A., Fallon V. A validation of the Postpartum Specific Anxiety Scale 12-item research short-form for use during global crises with five translations. BMC Pregnancy and Childbirth. 2021;21(112):1–12. doi: 10.1186/s12884-021-03597-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spielberger C.D., Gorsuch R.L., Lushene R.E., et al. Manual for the State-Trait Anxiety Inventory. Consulting Psychologists Press; Palo Alto: 1970. [Google Scholar]

- Taylor A., Atkins R., Kumar R., Adams D., Glover V. A new Mother-to-Infant Bonding Scale: links with early maternal mood. Arch. Wom. Ment. Health. 2005;8(1):45–51. doi: 10.1007/s00737-005-0074-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thapa S.B., Mainali A., Schwank S.E., Acharya G. Maternal mental health in the time of the COVID‐19 pandemic. Acta Obstet. Gynecol. Scand. 2020;99(7):817–818. doi: 10.1111/aogs.13894. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- The Lancet Psychiatry Isolation and inclusion. Lancet Psychiatr. 2020;7(5):371. doi: 10.1016/S2215-0366(20)30156-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zanardo V., Manghina V., Giliberti L., Vettore M., Severino L., Straface G. Psychological impact of COVID‐19 quarantine measures in northeastern Italy on mothers in the immediate postpartum period. Int. J. Gynecol. Obstet. 2020;150(2):184–188. doi: 10.1002/ijgo.13249. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zimet G.D., Dahlem N.W., Zimet S.G., Farley G.K. The multidimensional scale of perceived social support. J. Pers. Assess. 1988;52(1):30–41. doi: 10.1207/s15327752jpa5201_2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

All data is part of the common dataset for The PRegnancy And Motherhood during COVID-19 Study [The PRAM Study]. Applications to use these data in research are to be made formally by writing to the study's Chief Investigator: Dr. V. Fallon, University of Liverpool, V.Fallon@liverpool.ac.uk. All subsequent publications must state affiliation to The PRAM Study.