Abstract

The early diagnosis and the accurate separation of COVID-19 from non-COVID-19 cases based on pulmonary diffuse airspace opacities is one of the challenges facing researchers. Recently, researchers try to exploit the Deep Learning (DL) method’s capability to assist clinicians and radiologists in diagnosing positive COVID-19 cases from chest X-ray images. In this approach, DL models, especially Deep Convolutional Neural Networks (DCNN), propose real-time, automated effective models to detect COVID-19 cases. However, conventional DCNNs usually use Gradient Descent-based approaches for training fully connected layers. Although GD-based Training (GBT) methods are easy to implement and fast in the process, they demand numerous manual parameter tuning to make them optimal. Besides, the GBT’s procedure is inherently sequential, thereby parallelizing them with Graphics Processing Units is very difficult. Therefore, for the sake of having a real-time COVID-19 detector with parallel implementation capability, this paper proposes the use of the Whale Optimization Algorithm for training fully connected layers. The designed detector is then benchmarked on a verified dataset called COVID-Xray-5k, and the results are verified by a comparative study with classic DCNN, DUICM, and Matched Subspace classifier with Adaptive Dictionaries. The results show that the proposed model with an average accuracy of 99.06% provides 1.87% better performance than the best comparison model. The paper also considers the concept of Class Activation Map to detect the regions potentially infected by the virus. This was found to correlate with clinical results, as confirmed by experts. Although results are auspicious, further investigation is needed on a larger dataset of COVID-19 images to have a more comprehensive evaluation of accuracy rates.

Keywords: COVID-19, Whale optimization algorithm, Deep convolutional neural networks, Chest X-rays

Introduction

Due to the lack of access to treatment and vaccines for coronavirus, its early detection has become a challenge for scientists [1–3]. The polymerase Chain Reaction (PCR) test has been introduced as one of the primary methods for detecting COVID-19 [4–6]. However, PCR test is a laborious [7], very time-consuming, and complicated process with kits currently in short supply [8, 9]. On the other hand, X-ray images are extensively accessible [10, 11], and scans are comparatively low cost [12–14].

The necessity of designing an accurate [15, 16], real-time detector has become more prominent [17–20]. Considering DL’s outstanding capability in these cases [21–24], we propose to employ DCNN as a COVID-19 detector. A few research studies have been carried out since the beginning of the year 2020 that attempt to develop methods to identify patients affected by the epidemic by DCNN [25–27]. Although DL’s salient features enable it to solve various learning tasks [28–31], training is difficult [32–34]. Some examples of successful methods for training DL are GD [35, 36], Conjugate Gradient (CG) [37, 38], Arbitrary Lagrangian–Eulerian [39, 40], Hessian-Free Optimization (HFO) algorithm [41, 42], and Krylov Subspace Descent (KSD) [42].

Although GD-based Training (GBT) methods are easy to implement and fast in the process [43, 44], they demand numerous manual parameter tuning to make them optimal [45, 46]. Besides, the GBT’s procedure is inherently sequential, thereby parallelizing them with Graphics Processing Units (GPU) is very difficult [47, 48]. On the other hand, although GBT is stable for training, it is almost slow [49]; thereby, it needs multiple CPUs and a vast number of RAMs resource [50, 51].

The Deep auto-encoders have used HFO to train the weights [41], which is more efficient in pre-training and fine-tuning deep auto-encoders than the model proposed by Hinton and Salakhutdinov [52]. On the other side, KSD is simpler and more robust than HFO; besides, it is proven that KSD presents better classification performance and optimization speed than HFO. However, KSD requires more memory than HFO [53].

Heuristic or metaheuristic methods have recently been considered to optimize various parameters and problems [54–56]. Nevertheless, the research study on metaheuristics to optimize DL approaches is rarely carried out [57, 58]. The fusion of the Genetic Algorithm (GA) and DCNN, proposed in [59], was the first study that initiates this optimization model using metaheuristic algorithms. Their approach chooses the DCNN characteristic by the process of recombination and mutation on GA, in which the model of DCNN is considered as a chromosome in GA. In addition, in the recombination phase, just the threshold and weight values of C1 (first convolution layer) and C3 (third convolution layer) are modified in the DCNN model. Tuning a DCNN using GA and bezier curve for robot path optimization in dynamic environments is another research work, which suffers from high computational complexity [60].

Fine-tuning DCNN parameters using harmony search (HS) and some of its modifications in handwritten digit and fingerprint recognition was proposed by Rosa et al. [61].

Reference [62] proposed a Progressive Unsupervised Learning (PUL) approach to transfer pre-trained deep DCNN. This method is easy to implement and can be viewed as an effective baseline for unsupervised feature learning. Since the clustering results can be very noisy, this method adds a selection operation between the clustering and fine-tuning phases.

An automatic DCNN architecture design method using genetic algorithms is proposed in [63] to optimize the image classification problems. The proposed algorithm’s main feature is related to its automatic characteristic: users do not need any knowledge about DCNN’s structure. However, this method’s main drawback is that the GA’s chromosomes become too large in large DCNNs, which slows down the algorithm.

The Social-spider optimization algorithm has optimized a deep ANFIS network to predict the biochar yield; however, this combination confronts the ill-conditioning problem [64].

It is worth mentioning that there are other algorithms and techniques tried to improve the performance of deep networks in different fields of study, including the multi-objective transportation [65], Improved feature selection technique [66], a firefly-based algorithm with Levy distribution [67], discrete transforms with selective coefficients [68], signcryption technique [69], equivalent transfer function [70], the enhanced whale optimization algorithm [71]. However, all mentioned methods suffer from high computational complexity and unreliability dealing with image processing problems with high-dimension search space.

Considering the aforementioned limitations and shortcomings, our proposed approach includes training a DCNN network from a draft on the COVIDetectioNet dataset [72] to learn to classify infected and normal X-ray images. Subsequently, the last fully-connected layer of the pre-trained DCNN will be replaced by a new fully-connected layer, which is fine-tuned with WOA [73]. In this regard, a particular network representation will be introduced by searching agents. However, in the residual layers of the pre-trained DCNN, the other weights are preserved, which causes training a linear model with the features produced in the prior layer. The proposed scheme is as follows:

Exert the COVIDetectioNet dataset to the convolutional DCNN and load its pre-trained weights.

Substitute the final fully-connected layer of the pre-trained DCNN with the WOA-trained fully-connected layer.

Preserve the remaining layers’ weights.

Finally, retrain the whole model using WOA

For the rest of this research paper, the organization is as follows. In Sect. 2, we review some background materials. Section 3 introduces the proposed scheme. Section 4 presents the simulation and discussion results, and finally, conclusions are presented in Sect. 5.

Background and Materials

The background knowledge, including the WOA algorithm, the DCCN, and the COVID-X-ray dataset, will be represented in this section.

Whale Optimization Algorithm

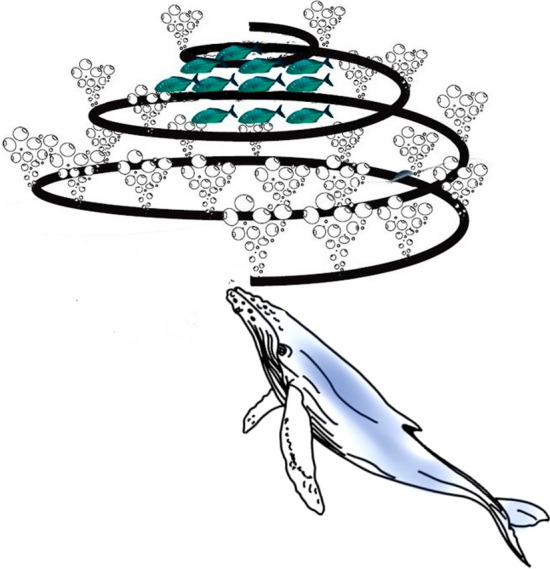

Generally, WOA is a novel Swarm Intelligence (SI) optimization algorithm that mathematically formulates humpback whales’ hunting manner [73]. The distinct difference between WOA and other benchmark optimization algorithms is the updating model to improve the candidate solutions. This mathematical model contains searching and attacking prey called bubble-net feeding. The bubble-net feeding behavior is shown in Fig. 1.

Fig. 1.

The bubble-net feeding mechanism of hunting.

This figure shows that intelligent hunting is carried out by generating a trap by moving in a spiral “9-shape” way around the prey and generating bubbles along the spiral path. The encircling is another hunting mechanism of humpback whales. Firstly, WOA initiates the hunting process by encircling the prey using the bubble-net feeding mechanism. The mathematical model of WOA is as follows [73]:

| 1 |

| 2 |

| 3 |

| 4 |

| 5 |

| 6 |

where X is a vector presenting the positions of whales during iterations and X* is a vector indicating locations of the prey, r represents a random number inside [0,1], indicating the distance of the ith searching agent and the prey, k is a constant number determining the bubble-net spiral shape, l is a random number inside [-1, 1], t indicating the current iteration, Q is a vector which linearly decreases from two to zero during iterations, and R is a random vector inside [0, 1]. While r < 0.5, Eq. (1) simulates the encircling behavior; otherwise, the equation intends to model the bubble-net feeding mechanism. Therefore, r randomly exchanges the model behavior between these two main phases.

Convolution Neural Network

Generally, DCNN is a conventional Multi-Layer Perceptron (MLP) based on three concepts: connection weights sharing, local receive fields, and temporal/spatial sub-sampling. These concepts can be arranged into two classes of layers, including subsampling layers and convolution layers. As shown in Fig. 2, the processing layers include three convolution layers C1, C3, and C5, which are located one between layers S2 and S4, and final output layer F6. These sub-sampling and convolution layers are organized as feature maps.

Fig. 2.

The architecture of LeNet-5 DCNN

Neurons in the convolution layer are linked to a local receptive field in the prior layer. Consequently, neurons with identical feature maps (FMs) receive data from various input regions until the input is completely skimmed. However, the same weights are shared.

In the sub-sampling layer, the FMs are spatially down-sampled by a factor of 2. As an illustration, in layer C3, the FM of size 10 × 10 is sub-sampled to conforming FM of size 5 × 5 in the next layer, S4. The classification process is the final layer (F6).

Each FMs are the outcome of a convolution from the previous layer’s maps by their corresponding kernel and a linear filter in this structure. The weights and adding bias bk generate the kth (FM) using the tanh function as Eq. (7).

| 7 |

By reducing the resolution of FMs, the sub-sampling layer lead to spatial invariance, in which each pooled FM refers to one FM of the prior layer. The sub-sampling function is defined as Eq. (8).

| 8 |

where are the inputs, and b are trainable scalar and bias, respectively. After a diverse convolution and sub-sampling layer, the last layer is a fully connected structure that carries out the classification task. There is one neuron for each output class. Thereby, in the case of the Covid-19 dataset, this layer contains two neurons for their classes.

COVID-X-Ray Dataset

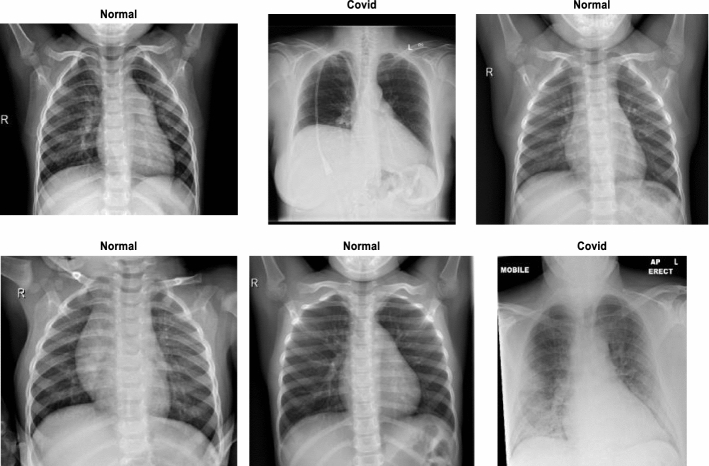

In this paper, a dataset named COVID X-ray-5 k dataset, including 2084 training and 3100 test images, was utilized [74]. In this dataset, considering radiologist advice, only anterior–posterior Covid-19 X-ray images are utilized because the lateral images are not applicable for detection purposes. Expert radiologists evaluated those images, and those that did not have clear signs of COVID-19 were removed. In this way, 19 images out of the 203 images were removed, and 184 images remained, indicating clear signs of COVID-19. With this method, the community a more clearly labeled dataset was introduced. Of these 184 photos, 100 images are considered for the test set, and 84 images are intended for the training set. For the sake of increasing the number of COVID-19 samples to 420, data augmentation is applied. Since the number of non-COVID images was minimal in the covid-chestxray-dataset [75], the supplementary ChexPert dataset [76] was employed. This dataset includes 224,316 chest X-ray images of 65,240 patients. In this dataset, 2000 and 3000 non-COVID images were chosen for the training set and test set, respectively. The final number of images related to various classes is reported in Table 1. Figure 3 indicates six stochastic sample images from the COVID-X-ray-5k dataset, including two COVID-19 and four standard samples.

Table 1.

The categories of images per class in the COVID dataset

| Category | COVID-19 | Normal |

|---|---|---|

| Training set | 84 (420 after augmentation) | 2000 |

| Test set | 100 | 3000 |

Fig. 3.

Six stochastic sample images from the COVID-X-ray-5 k dataset

Methodology

Presentation of Searching Agent

Generally, there are two main issues in tuning a deep network using a meta-heuristic optimization algorithm. First, the structure’s parameters must be represented by the meta-heuristic algorithm’s searching agents (candid solution). Next, the fitness function must be defined based on the interest of the considered problem [77].

The presentation of network parameters is a distinct phase in tuning a DCNN using the WOA algorithm. Thereby, important parameters of the DCNN, i.e., weights and biases of the fully connected layer, should be determined to provide the best detection accuracy [78].

To sum up, the WOA algorithm optimizes the last layer’s values of weights and bias used to calculate the loss function as a fitness function. The weight and bias values in the last layer are used as searching agents in the WOA algorithm.

Generally speaking, three schemes are used to present weights and biases of a DCNN as candid solutions of the meta-heuristic algorithm: vector-based, matrix-based, and binary state. Considering the fact that the WOA needs the parameters in a vector-based model, in this paper, the candid solution is shown as Eq. 9 and Fig. 4.

| 9 |

where n is the number of the input nodes, Wij indicates the connection weight between the ith input node and the jth hidden neuron, bj is the jth hidden neuron’s bias, and Mjo shows the connection weight from the jth hidden neuron to the oth output neuron. As previously stated, the proposed architecture is a simple LeNet-5 structure. In this section, two structures, namely i-6c-2 s-12c-2 s and i-8c-2 s-16c-2 s, are used where C and S are convolution and sub-sampling layers, respectively [79, 80]. The kernel size of all convolution layers is 5 × 5, and the scale of sub-sampling is down-sampled by a factor of 2.

Fig. 4.

Assigning the DCNN’s parameters as the candid solution (searching agents) of WOA

Loss Function

The WOA algorithm trains DCNN (DCNN-WOA) to obtain the best accuracy and minimize evaluated classification error and network complexity in the proposed meta-heuristic method. This objective can be computed by the loss function of the metaheuristic searching agent or the Mean Square Error (MSE) classification procedure. However, the loss function used in this method is as follows:

| 10 |

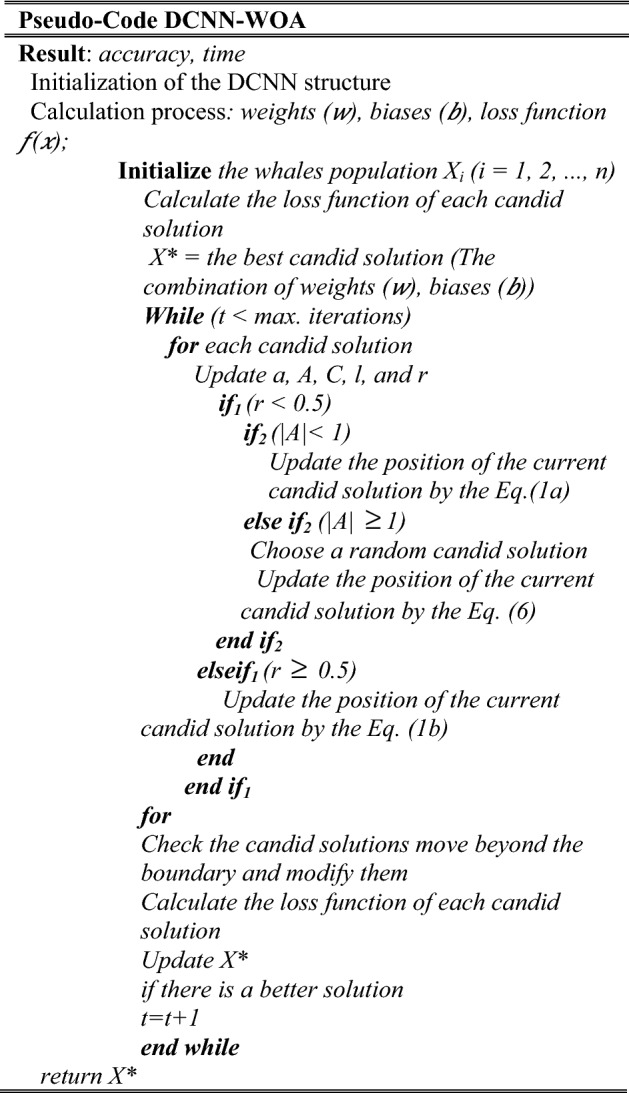

where o shows the supposed output, u indicates the desired output, and N shows the number of training samples. Two termination criteria: reaching maximum iteration or predefined loss function, are utilized by the proposed WOA algorithm. Consequently, the pseudo-code of DCNN-WOA is shown in Fig. 5.

Fig. 5.

The Pseudo-code for DCNN-WOA model

Simulation Results and Discussion

As stated before, the principal goal is to improve the classification accuracy of classic DCNN by using the WOA algorithm. According to references [25, 73] and also in order to have a fair comparison, the population is set to 10, and the maximum iteration is set to 10. The parameter of DCNN, i.e., the learning rate α and the batch size, are equal to 1 and 100, respectively. Also, the number of epochs is considered between 1 and 10 for every evaluation. The evaluation was carried out in MATLAB-R2019a, on a PC with processor Intel Core i7-4500u, 16 GB RAM running memory, in Windows 10, with five separate runtimes.

As proven in the literature [81, 82], the accuracy rate does not represent enough information about the detector’s performance. Thereby, Receiver Operating Characteristic (ROC) curves were used to exploit the classifier on all the samples in the test datasets, devoting an evaluated probability of images PT for each sample. Next, a threshold value was introduced, and for each threshold value, the detection rate was calculated. Thereby, the computed values were plotted as a ROC curve. Generally speaking, the area under the ROC curve (AUC) shows the probability of correct detection.

Figure 6 indicates the calculated ROC curves for the detection of COVID-19 samples using DCNN-WOA and conventional DCNN. This comparison was carried out because the test dataset, the initial conditions, and the primary convolutional network (LeNet-5 DCNN) are entirely identical. Therefore, the effectiveness of the WOA algorithm on classic LeNet-5 DCNN can be fairly compared. The ROC curves show that DCNN-WOA significantly outperforms LeNet-5 DCNN on the test dataset.

Fig. 6.

ROC curves for DCNN-WOA and classic DCNN

The training was carried out ten times so that the training times varied between 5 and 10 min, and the designed DCNN-WOA had the detection accuracy of between 98.11% and 99.38% on the COVID-19 validation set.

Because of the extensive range of different results, the ten trained DCNN-WOA are ensemble by weighted averaging, using the validation accuracy as the weights. The combined ensemble DCNN-WOA achieves a validation accuracy of 98.74%, while LeNet-5 DCNN acquires the detection accuracy of between 84.58% and 93.31%, and the resulting ensemble obtained the detection accuracy of 88.94% on the COVID-19 validation dataset.

To further evaluate the performance of DCNN-WOA in the detection of COVID-19 samples from uninfected ones, newly proposed benchmark models include conventional DCNN [83], DUICM [84], and matched subspace classifier with adaptive dictionaries [85] are utilized. Figures 7 and 8 show the outcome ROC and precision-recall curve for i-6c-2s-12c-2s and i-8c-2s-16c-2s structures, respectively.

Fig. 7.

ROC and Precision-recall curves for i-6c-2s-12c-2s models

Fig. 8.

ROC and Precision-recall curves for i-8c-2s-16c-2s models

As can be seen from these figures, the DCNN-WOA detector indicates outstanding COVID-19 detection results compared with other benchmark models. For the sake of comparison, the proposed DCNN-WOA provides over 98.25% correct COVID-19 sample detection for less than a 1.75% false alarm detection rate, which shows the WOA algorithm’s capability to increase the performance of the DCNN model.

Generally, the precision-recall plot shows the tradeoff between recall and precision for various threshold levels [86]. A high area under the precision-recall curve represents both high precision and recall, where high precision indicates a low false-positive rate, and high recall indicates a low false-negative rate [86, 87]. As can be observed from the curves in Figs. 7 and 8, DCNN-WOA has a higher area under the precision-recall curves. Therefore, it indicates a lower false positive and false negative rate than other benchmark detectors.

The obtain accuracy and computational time results for the i-6c-2s-12c-2s structure are summarized in Tables 2 and 3 in order. Also, the obtain accuracy and computational time results for the i-8c-2s-16c-2s network are summarized in Tables 4 and 5, in order. The original DCNN is evaluated only once for each epoch because the accuracy is not changed if the evaluation is repeated with the same experimental condition. In general, the tests conducted showed that the higher the epoch value, the better is the accuracy. For example, in the first epoch, compared to DCNN (84.11), the accuracy increased to 4.01 for MSAD (88.12), 5.18 to DCNN-WOA (89.29), and 2.04 for DUICM (86.15). While in the fifth epoch, compared to DCNN (93.47), the increase of accuracy is 1.94 for MSAD (95.41), 4.09 for DCNN-WOA (97.56), and 0.50 for DUICM (93.97). In the case of 10 epochs, as reported in Table 2, the increase in accuracy compared to DCNN (97.18) is only 0.04 for MSAD (97.22), 2.67 for DCNN-WOA (99.85), and 0.28 for DUICM (97.46).

Table 2.

Accuracy and STD for i-2s-6c-2s-12c structure

| Epoch | DCNNWOA | MSAD | DUICM | DCNN | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Accuracy (%) | STD | Accuracy (%) | STD | Accuracy (%) | STD | Accuracy (%) | STD | |

| 1 | 89.99 | N/A | 88.12 | 0.41 | 86.15 | 0.33 | 84.11 | 0.75 |

| 2 | 93.14 | N/A | 92.11 | 0.37 | 90.22 | 0.21 | 89.22 | 0.31 |

| 3 | 96.22 | N/A | 93.12 | 0.31 | 92.01 | 0.32 | 91.11 | 0.38 |

| 4 | 97.45 | N/A | 94.62 | 0.24 | 92.99 | 0.38 | 92.47 | 0.11 |

| 5 | 97.56 | N/A | 95.41 | 0.18 | 93.97 | 0.14 | 93.47 | 0.29 |

| 6 | 98.88 | N/A | 95.92 | 0.17 | 95.11 | 0.22 | 94.02 | 0.39 |

| 7 | 98.95 | N/A | 96.11 | 0.16 | 96.01 | 0.21 | 95.17 | 0.19 |

| 8 | 98.97 | N/A | 96.77 | 0.12 | 97.11 | 0.13 | 96.58 | 0.21 |

| 9 | 99.37 | N/A | 96.99 | 0.09 | 97.44 | 0.14 | 96.76 | 0.09 |

| 10 | 99.85 | N/A | 97.22 | 0.15 | 97.46 | 0.11 | 97.18 | 0.11 |

Table 3.

Computation time and STD for i-2s-6c-2s-12c structure

| Epoch | DCNNWOA | MSAD | DUICM | DCNN | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Time (s) | STD | Time (s) | STD | Time (s) | STD | Time (s) | STD | |

| 1 | 99.11 | N/A | 102.23 | 1.01 | 112.08 | 0.89 | 102.11 | 0.77 |

| 2 | 202.14 | N/A | 236.03 | 8.54 | 267.11 | 1.54 | 268.47 | 4.33 |

| 3 | 307.68 | N/A | 347.41 | 2.32 | 399.96 | 2.25 | 299.17 | 0.53 |

| 4 | 362.22 | N/A | 421.45 | 2.01 | 547.27 | 2.16 | 443.49 | 0.65 |

| 5 | 461.11 | N/A | 582.47 | 3.96 | 521.27 | 1.37 | 601.77 | 3.09 |

| 6 | 586.31 | N/A | 692.75 | 1.23 | 636.75 | 5.96 | 721.22 | 2.01 |

| 7 | 657.42 | N/A | 797.02 | 1.02 | 739.67 | 4.01 | 836.75 | 2.25 |

| 8 | 754.11 | N/A | 854.43 | 1.74 | 828.73 | 4.36 | 1007.9 | 1.53 |

| 9 | 849.57 | N/A | 964.12 | 2.01 | 998.89 | 6.02 | 1125.57 | 5.07 |

| 10 | 934.54 | N/A | 1112.36 | 1.97 | 1223.35 | 1.47 | 1133.44 | 4.25 |

Table 4.

Accuracy and STD for i-2s-8c-2s-16c structure

| Epoch | DCNNWOA | MSAD | DUICM | DCNN | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Accuracy (%) | STD | Accuracy (%) | STD | Accuracy (%) | STD | Accuracy (%) | STD | |

| 1 | 89.32 | N/A | 88.17 | 0.32 | 87.25 | 0.31 | 86.22 | 0.65 |

| 2 | 92.56 | N/A | 91.99 | 0.33 | 87.99 | 0.14 | 87.12 | 0.32 |

| 3 | 93.22 | N/A | 94.12 | 0.15 | 90.22 | 0.22 | 90.56 | 0.39 |

| 4 | 95.11 | N/A | 94.52 | 0.25 | 92.25 | 0.41 | 92.72 | 0.11 |

| 5 | 95.75 | N/A | 95.33 | 0.21 | 94.11 | 0.14 | 93.59 | 0.29 |

| 6 | 95.73 | N/A | 96.01 | 0.11 | 95.05 | 0.22 | 94.18 | 0.39 |

| 7 | 96.50 | N/A | 96.57 | 0.11 | 96.32 | 0.21 | 95.15 | 0.19 |

| 8 | 96.86 | N/A | 96.89 | 0.12 | 96.48 | 0.12 | 95.78 | 0.22 |

| 9 | 97.86 | N/A | 97.01 | 0.05 | 96.78 | 0.16 | 96.53 | 0.09 |

| 10 | 98.27 | N/A | 97.27 | 0.12 | 96.92 | 0.11 | 96.89 | 0.05 |

Table 5.

Computation time and STD for i-2s-8c-2s-16c structure

| Epoch | DCNNWOA | MSAD | DUICM | DCNN | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Time (s) | STD | Time (s) | STD | Time (s) | STD | Time (s) | STD | |

| 1 | 95.33 | N/A | 99.48 | 1.17 | 122.28 | 0.89 | 171.54 | 0.78 |

| 2 | 247.14 | N/A | 187.41 | 9.78 | 262.18 | 1.47 | 362.15 | 6.01 |

| 3 | 300.04 | N/A | 342.19 | 2.01 | 399.63 | 2.22 | 399.10 | 0.54 |

| 4 | 352.04 | N/A | 425.81 | 2.00 | 524.35 | 2.14 | 532.12 | 0.62 |

| 5 | 422.33 | N/A | 523.15 | 3.98 | 517.23 | 1.36 | 701.91 | 3.01 |

| 6 | 545.87 | N/A | 699.41 | 1.33 | 680.31 | 5.86 | 811.56 | 2.01 |

| 7 | 625.07 | N/A | 795.15 | 1.12 | 764.19 | 4.01 | 968.18 | 2.02 |

| 8 | 687.01 | N/A | 900.61 | 1.67 | 874.74 | 4.48 | 1105.2 | 1.22 |

| 9 | 799.12 | N/A | 1002.11 | 2.34 | 972.87 | 5.78 | 1245.54 | 5.02 |

| 10 | 932.35 | N/A | 1112.56 | 1.97 | 1223.44 | 1.47 | 1473.99 | 4.74 |

The simulation results indicate that DCNN-WOA represents the best accuracy for all epochs. Accuracy improvement of DCNN-WOA, compared to the original DCNN, varies for each epoch, with a range of values between 2.67 (the tenth epoch) up to 5.88 (the first epoch). Considering the stochastic nature of WOA and stochastically choosing the connection weight of the fully connected layer, the computation time for the DCNN-WOA, compared to the classic DCNN, is in the range of 0.9706 times (for the first epoch: 99.11/102.11) up to 0.8245 times (for the tenth epoch: 934.54/1133.44). It is evident that as the number of epochs increases, the time efficiency of the WOA is more prominent because the stochastic nature of the WOA algorithm leads to decreasing the complexity of the search space. It should be pointed out that the results of the i-8c-2s-16c-2s structure indicated in Tables 4 and 5 approve the prior conclusion for the i-8c-2s-16c-2s network. Consequently, WOA can improve the performance of DCNN with the i-8c-2s-16c-2s structure as well as the i-6c-2s-12c-2s structure.

From the viewpoint of data science experts, the best result could be indicated in terms of the confusion matrix, overall accuracy, precision, recall, ROC curve, etc. However, these optimal results might not be sufficient for medical specialists and radiologists if the results cannot be interpreted. Identifying the Region of Interest (ROI) leading to the network’s decision-making will enhance medical experts’ understanding [88].

In this section, the results provided by designed networks for the COVID X-ray-5k dataset were investigated. The Class Activation Mapping (CAM) results were displayed for the COVID X-ray-5k dataset to localize the areas suspicious of the Covid-19 virus. To emphasize the discriminative regions, the probability predicted by the DCNN model for each image class gets mapped back to the last convolutional layer of the corresponding model that is particular to each class. The CAM for a determined image class is the outcome of the activation map of the Rectified Linear Unit (ReLU) layer following the last convolutional layer. It is identified by how much each activation mapping contributes to the final grade of that particular class. The novelty of CAM is the total average pooling layer applied after the last convolutional layer based on the spatial location to produce the connection weights. Thereby, it permits identifying the desired regions within an X-ray image that differentiates the class specificity preceding the Softmax layer, which leads to better predictions.

Demonstration using CAM for DCNN models allows the medical specialists and radiology experts to localize the areas suspicious of the Covid-19 virus indicating in Figs. 9 and 10.

Fig. 9.

ROI for positive Covid-19 cases using ACM

Fig. 10.

ROI for Normal cases using ACM

Figures 9 and 10 indicate the results for Covid-19 detection in X-ray images. Figure 9 shows the outcomes for the case marked as ‘Covid-19’ by the radiologist, and the DCNN-WOA model predicts the same and indicates the discriminative area for its decision.

Figure 10 shows the outcomes for a ‘normal’ case in X-ray images, and different regions are emphasized by both comparing models for their prediction of the ‘normal’ subset. Now, medical specialists and radiology experts can choose the network architecture based on these decisions. This kind of CAD visualization would provide a useful second opinion to the medical specialists and radiology experts and also improve their understanding of deep learning models.

Conclusion

In this paper, the WOA was proposed to design an accurate DCNN model for positive Covid-19 X-ray detection. The designed detector was benchmarked on the COVID-Xray-5k dataset, and the results were evaluated by a comparative study with classic DCNN, DUICM, and MSAD. The results indicated that the designed detector could present very competitive results compared to these benchmark models. The concept of Class Activation Map (CAM) was also applied to detect the virus’s regions potentially infected. It was found to correlate with clinical results, as confirmed by experts. A few research directions can be proposed for future work with the DCNN-WOA, such as underwater sonar target detection and classification. Also, changing WOA to tackle multi-objective optimization problems can be recommended as a potential contribution. The investigation of the chaotic maps’ effectiveness to improve the performance of the DCNN-WOA can be another research direction. Although the results were promising, further investigation is needed on a larger dataset of COVID-19 images to have a more comprehensive evaluation of accuracy rates.

Biographies

Xusheng Wang

was born in Shanxi, P.R. China, in 1988. He received the PhD. degree from University of Paris Sud, France. Now, he works in Xi’an University of Technology. His research interest include computer network computational intelligence, and integrated circuit design.

Cunqi Gong

, male, 42, his research interest is clinical biochemistryDepartment of Clinical Laboratory, Jining No. 1 People's Hospital, 6 Jiankang Road, Jining, Shandong 272,000, P.R. China.

Mohammad Khishe

was born on 1985 in Nahavand, Iran. He received the B.Sc. degree in Maritime Electronic and Communication Engineering from Imam Khomeini Maritime Sciences University, Nowshahr, Iran in 2007 and also, M.Sc. and Ph. D. degrees in Electronic Engineering from Islamic Azad University, Qazvin branch and Iran University of Science and Technology, Tehran in 2012 and 2017, respectively. Since 2011, he is a faculty member of Maritime Electrical and Electronic Engineering at Imam Khomeini Maritime Sciences University, Nowshahr, Iran. His research interests are Digital Signal Processing, Artificial Neural Networks, Meta-heuristic Algorithms, Sonar and Radar Signal Processing, and FPGA design.

Mokhtar Mohammadi

received the B.S. degree in computer engineering from Shahed University, Tehran, Iran, in 2003, the M.S. degree in computer engineering from Shahid Beheshti University, Tehran, Iran, in 2012, and the Ph.D. degree in computer engineering from Shahrood University of Technology, Shahrood, Iran, in 2018. His current research interests include signal processing, time–frequency analysis, and machine learning. He is currently with the Department of Information Technology, Lebanese French University-Erbil, Iraq.

Professor Dr. Tarik A. Rashid

received his Ph.D. in Computer Science and Informatics from College of Engineering, Mathematical and Physical Sciences, University College Dublin (UCD) in 2001–2006. He pursued his Post-Doctoral Fellow at the Computer Science and Informatics School, College of Engineering, Mathematical and Physical Sciences, University College Dublin (UCD) from 2006–2007. He joined the University of Kurdistan Hewlêr (UKH) in 2017.

Funding

Not Applicable.

Availability of Data and Material

The resource images can be downloaded using the following link and references [72]. https://github.com/ieee8023/covid-chestxray-dataset, 2020.

Code Availability

The source code of the models can be available by request.

Declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that there is no conflict of interest regarding the publication of this paper.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Li X, Dong Z-Q, Yu P, Wang L-P, Niu X-D, Yamaguchi H, et al. Effect of self-assembly on fluorescence in magnetic multiphase flows and its application on the novel detection for COVID-19. Physics of Fluids. 2021;33:42004. doi: 10.1063/5.0048123. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Liu Y, Lv X, Tang Z. The impact of mortality salience on quantified self behavior during the COVID-19 pandemic. Personality and Individual Differences. 2021;180:110972. doi: 10.1016/j.paid.2021.110972. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Abdel-Basset M, Mohamed R, Elhoseny M, Chakrabortty RK, Ryan M. A hybrid COVID-19 detection model using an improved marine predators algorithm and a ranking-based diversity reduction strategy. IEEE Access. 2020;8:79521–79540. doi: 10.1109/ACCESS.2020.2990893. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Pang X, Gong K, Zhang X, Wu S, Cui Y, Qian B-Z. Osteopontin as a multifaceted driver of bone metastasis and drug resistance. Pharmacological Research. 2019;144:235–244. doi: 10.1016/j.phrs.2019.04.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Elhoseny M, Shankar K, Uthayakumar J. Intelligent diagnostic prediction and classification system for chronic kidney disease. Science and Reports. 2019;9:1–14. doi: 10.1038/s41598-019-46074-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Thakur S, Singh AK, Ghrera SP, Elhoseny M. Multi-layer security of medical data through watermarking and chaotic encryption for tele-health applications. Multimedia Tools and Applications. 2019;78:3457–3470. doi: 10.1007/s11042-018-6263-3. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Abdel-Basset M, El-Hoseny M, Gamal A, Smarandache F. A novel model for evaluation Hospital medical care systems based on plithogenic sets. Artificial Intelligence in Medicine. 2019;100:101710. doi: 10.1016/j.artmed.2019.101710. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Abdel-Basset M, Mohamed M, Elhoseny M, Chiclana F, Zaied AE-NH. Cosine similarity measures of bipolar neutrosophic set for diagnosis of bipolar disorder diseases. Artificial Intelligence in Medicine. 2019;101:101735. doi: 10.1016/j.artmed.2019.101735. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Libo Z, Tian H, Chunyun G, Elhoseny M. Real-time detection of cole diseases and insect pests in wireless sensor networks. Journal of Intelligent & Fuzzy Systems. 2019;37:3513–3524. doi: 10.3233/JIFS-179155. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Zuo C, Chen Q, Tian L, Waller L, Asundi A. Transport of intensity phase retrieval and computational imaging for partially coherent fields: The phase space perspective. Optics and Lasers in Engineering. 2015;71:20–32. doi: 10.1016/j.optlaseng.2015.03.006. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Zuo C, Sun J, Li J, Zhang J, Asundi A, Chen Q. High-resolution transport-of-intensity quantitative phase microscopy with annular illumination. Science and Reports. 2017;7:1–22. doi: 10.1038/s41598-017-06837-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Elhoseny M, Bian G-B, Lakshmanaprabu SK, Shankar K, Singh AK, Wu W. Effective features to classify ovarian cancer data in internet of medical things. Computer Networks. 2019;159:147–156. doi: 10.1016/j.comnet.2019.04.016. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Elhoseny M, Shankar K. Optimal bilateral filter and convolutional neural network based denoising method of medical image measurements. Measurement. 2019;143:125–135. doi: 10.1016/j.measurement.2019.04.072. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Geetha K, Anitha V, Elhoseny M, Kathiresan S, Shamsolmoali P, Selim MM. An evolutionary lion optimization algorithm-based image compression technique for biomedical applications. Expert Systems. 2021;38:e12508. doi: 10.1111/exsy.12508. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Uthayakumar J, Elhoseny M, Shankar K. Highly reliable and low-complexity image compression scheme using neighborhood correlation sequence algorithm in WSN. IEEE Transactions on Reliability. 2020;69:1398–1423. doi: 10.1109/TR.2020.2972567. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Pan D, Xia X-X, Zhou H, Jin S-Q, Lu Y-Y, Liu H, et al. COCO enhances the efficiency of photoreceptor precursor differentiation in early human embryonic stem cell-derived retinal organoids. Stem Cell Research & Therapy. 2020;11:1–12. doi: 10.1186/s13287-020-01883-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wu, C., Khishe, M., Mohammadi, M., Karim, S. H. T., Rashid, T. A. (2021). Evolving deep convolutional neutral network by hybrid sine–cosine and extreme learning machine for real-time COVID19 diagnosis from X-ray images. Soft Computing 1–20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 18.Elhoseny M. Multi-object detection and tracking (MODT) machine learning model for real-time video surveillance systems. Circuits, Systems, and Signal Processing. 2020;39:611–630. doi: 10.1007/s00034-019-01234-7. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Shankar, K., Elhoseny, M., Lakshmanaprabu, S.K., Ilayaraja, M., Vidhyavathi, R., Elsoud, M.A., & Alkhambashi, M. (2020). Optimal feature level fusion based ANFIS classifier for brain MRI image classification. Concurrency and Computation: Practice and Experience, 32.

- 20.Niu Z, Zhang B, Wang J, Liu K, Chen Z, Yang K, et al. The research on 220GHz multicarrier high-speed communication system. China Communications. 2020;17:131–139. doi: 10.23919/JCC.2020.03.011. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Qin C, Jin Y, Tao J, Xiao D, Yu H, Liu C, et al. DTCNNMI: A deep twin convolutional neural networks with multi-domain inputs for strongly noisy diesel engine misfire detection. Measurement. 2021;180:109548. doi: 10.1016/j.measurement.2021.109548. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Cai K, Chen H, Ai W, Miao X, Lin Q, Feng Q. Feedback convolutional network for intelligent data fusion based on near-infrared collaborative IoT technology. IEEE Transactions on Industrial Informatics. 2021;18:1200–1209. doi: 10.1109/TII.2021.3076513. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Mohanty SN, Lydia EL, Elhoseny M, Al Otaibi MMG, Shankar K. Deep learning with LSTM based distributed data mining model for energy efficient wireless sensor networks. Physical Communication. 2020;40:101097. doi: 10.1016/j.phycom.2020.101097. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Elhoseny H., Elhoseny, M., Riad A. M., Hassanien, A. E. (2018). A framework for big data analysis in smart cities. In The International Conference on Advanced Machine Learning Technologies and Applications, Springer; (pp. 405–14).

- 25.Khishe M, Caraffini F, Kuhn S. Evolving deep learning convolutional neural networks for early COVID-19 detection in chest X-ray images. Mathematics. 2021;9:1002. doi: 10.3390/math9091002. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hu T, Khishe M, Mohammadi M, Parvizi G-R, Karim SHT, Rashid TA. Real-time COVID-19 diagnosis from X-Ray images using deep CNN and extreme learning machines stabilized by chimp optimization algorithm. Biomedical Signal Processing and Control. 2021;68:102764. doi: 10.1016/j.bspc.2021.102764. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Krishnaraj N, Elhoseny M, Lydia EL, Shankar K, ALDabbas O. An efficient radix trie-based semantic visual indexing model for large-scale image retrieval in cloud environment. Software Practice and Experience. 2021;51:489–502. doi: 10.1002/spe.2834. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Xu X, Cao D, Zhou Y, Gao J. Application of neural network algorithm in fault diagnosis of mechanical intelligence. Mechanical Systems and Signal Processing. 2020;141:106625. doi: 10.1016/j.ymssp.2020.106625. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Saračević M, Adamović S, Maček N, Elhoseny M, Sarhan S. Cryptographic keys exchange model for smart city applications. IET Intelligent Transport Systems. 2020;14:1456–1464. doi: 10.1049/iet-its.2019.0855. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Krishnaraj N, Elhoseny M, Thenmozhi M, Selim MM, Shankar K. Deep learning model for real-time image compression in Internet of Underwater Things (IoUT) Journal of Real-Time Image Processing. 2020;17:2097–2111. doi: 10.1007/s11554-019-00879-6. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Tang Y, Elhoseny M. Computer network security evaluation simulation model based on neural network. J Intell Fuzzy Syst. 2019;37:3197–3204. doi: 10.3233/JIFS-179121. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Elhoseny, M., Yuan, X., El-Minir, H. K., Riad, A. M. (2014). Extending self-organizing network availability using genetic algorithm. In Fifth International Conference on Computing, Communications and Networking Technologies, IEEE, (pp. 1–6).

- 33.Tharwat A, Mahdi H, Elhoseny M, Hassanien AE. Recognizing human activity in mobile crowdsensing environment using optimized k-NN algorithm. Expert Systems with Applications. 2018;107:32–44. doi: 10.1016/j.eswa.2018.04.017. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Jiang D, Chen F-X, Zhou H, Lu Y-Y, Tan H, Yu S-J, et al. Bioenergetic crosstalk between mesenchymal stem cells and various ocular cells through the intercellular trafficking of mitochondria. Theranostics. 2020;10:7260. doi: 10.7150/thno.46332. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Ali M, Jung LT, Abdel-Aty A-H, Abubakar MY, Elhoseny M, Ali I. Semantic-k-NN algorithm: An enhanced version of traditional k-NN algorithm. Expert Systems with Applications. 2020;151:113374. doi: 10.1016/j.eswa.2020.113374. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Zhu L, Kong L, Zhang C. Numerical study on hysteretic behaviour of horizontal-connection and energy-dissipation structures developed for prefabricated shear walls. Applied Sciences. 2020;10:1240. doi: 10.3390/app10041240. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Le, Q. V., Ngiam, J., Coates, A., Lahiri, A., Prochnow, B., Ng, A. Y. (2011). On optimization methods for deep learning. In Proc. 28th Int. Conf. Mach. Learn. ICML 2011.

- 38.Zaher M, Shehab A, Elhoseny M, Farahat FF. Unsupervised model for detecting plagiarism in internet-based handwritten Arabic documents. Journal of Organizational and End User Computing. 2020;32:42–66. doi: 10.4018/JOEUC.2020040103. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Zhang C, Abedini M, Mehrmashhadi J. Development of pressure-impulse models and residual capacity assessment of RC columns using high fidelity Arbitrary Lagrangian-Eulerian simulation. Engineering Structures. 2020;224:111219. doi: 10.1016/j.engstruct.2020.111219. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Liu Y, Zhang B, Feng Y, Lv X, Ji D, Niu Z, et al. Development of 340-GHz Transceiver Front End Based on GaAs Monolithic Integration Technology for THz Active Imaging Array. Applied Sciences. 2020;10:7924. doi: 10.3390/app10217924. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Martens, J. (2010). Deep learning via Hessian-free optimization. In ICML 2010 - Proceedings, 27th Int. Conf. Mach. Learn.

- 42.Puri V, Jha S, Kumar R, Priyadarshini I, Abdel-Basset M, Elhoseny M, et al. A hybrid artificial intelligence and internet of things model for generation of renewable resource of energy. IEEE Access. 2019;7:111181–111191. doi: 10.1109/ACCESS.2019.2934228. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Cao B, Zhao J, Yang P, Yang P, Liu X, Qi J, et al. Multi-objective feature selection for microarray data via distributed parallel algorithms. Future Generation Computer Systems. 2019;100:952–981. doi: 10.1016/j.future.2019.02.030. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Dorri A, Kanhere SS, Jurdak R. MOF-BC: A memory optimized and flexible blockchain for large scale networks. Future Generation Computer Systems. 2019;92:357–373. doi: 10.1016/j.future.2018.10.002. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Yuan X, Li D, Mohapatra D, Elhoseny M. Automatic removal of complex shadows from indoor videos using transfer learning and dynamic thresholding. Computers & Electrical Engineering. 2018;70:813–825. doi: 10.1016/j.compeleceng.2017.12.026. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Alam Z, Sun L, Zhang C, Su Z, Samali B. Experimental and numerical investigation on the complex behaviour of the localised seismic response in a multi-storey plan-asymmetric structure. Structure and Infrastructure Engineering. 2021;17:86–102. doi: 10.1080/15732479.2020.1730914. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Hurrah NN, Parah SA, Loan NA, Sheikh JA, Elhoseny M, Muhammad K. Dual watermarking framework for privacy protection and content authentication of multimedia. Future Generation Computer Systems. 2019;94:654–673. doi: 10.1016/j.future.2018.12.036. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Shankar K, Elhoseny M. Trust based cluster head election of secure message transmission in MANET using multi secure protocol with TDES. JUCS Journal of Universal Computer Science. 2019;25:1221–1239. [Google Scholar]

- 49.Eassa AM, Elhoseny M, El-Bakry HM, Salama AS. NoSQL injection attack detection in web applications using RESTful service. Programming and Computer Software. 2018;44:435–444. doi: 10.1134/S036176881901002X. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Muhammad K, Khan S, Elhoseny M, Ahmed SH, Baik SW. Efficient fire detection for uncertain surveillance environment. IEEE Transactions on Industrial Informatics. 2019;15:3113–3122. doi: 10.1109/TII.2019.2897594. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Dutta AK, Elhoseny M, Dahiya V, Shankar K. An efficient hierarchical clustering protocol for multihop Internet of vehicles communication. Transactions on Emerging Telecommunications Technologies. 2020;31:e3690. doi: 10.1002/ett.3690. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Hinton GE, Osindero S, Teh Y-W. A fast learning algorithm for deep belief nets. Neural Computation. 2006;18:1527–1554. doi: 10.1162/neco.2006.18.7.1527. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Murugan BS, Elhoseny M, Shankar K, Uthayakumar J. Region-based scalable smart system for anomaly detection in pedestrian walkways. Computers & Electrical Engineering. 2019;75:146–160. doi: 10.1016/j.compeleceng.2019.02.017. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Khishe M, Mosavi MR. Chimp optimization algorithm. Expert Systems with Applications. 2020 doi: 10.1016/j.eswa.2020.113338. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Metawa, N., Elhoseny, M., Hassan, M. K., Hassanien, A. E. (2016). Loan portfolio optimization using genetic algorithm: a case of credit constraints. In 2016 12th International Computer Engineering Conference, IEEE; (pp. 59–64).

- 56.Devaraj AFS, Elhoseny M, Dhanasekaran S, Lydia EL, Shankar K. Hybridization of firefly and improved multi-objective particle swarm optimization algorithm for energy efficient load balancing in cloud computing environments. Journal of Parallel and Distributed Computing. 2020;142:36–45. doi: 10.1016/j.jpdc.2020.03.022. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Hosseinabadi AAR, Vahidi J, Saemi B, Sangaiah AK, Elhoseny M. Extended genetic algorithm for solving open-shop scheduling problem. Soft Computing. 2019;23:5099–5116. doi: 10.1007/s00500-018-3177-y. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Zhang B, Ji D, Fang D, Liang S, Fan Y, Chen X. A novel 220-GHz GaN diode on-chip tripler with high driven power. IEEE Electron Device Letters. 2019;40:780–783. doi: 10.1109/LED.2019.2903430. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 59.You Z, Pu Y. The genetic convolutional neural network model based on random sample. International Journal of u-and e-Service, Science and Technology. 2015 doi: 10.14257/ijunesst.2015.8.11.31. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Elhoseny M, Shehab A, Yuan X. Optimizing robot path in dynamic environments using genetic algorithm and bezier curve. Journal of Intelligent & Fuzzy Systems. 2017;33:2305–2316. doi: 10.3233/JIFS-17348. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Rosa, G., Papa, J., Marana, A., Scheirer, W., Cox, D. (2015). Fine-tuning convolutional neural networks using Harmony Search. Lect. Notes Comput. Sci. (including Subser. Lect. Notes Artif. Intell. Lect. Notes Bioinformatics). 10.1007/978-3-319-25751-8_82.

- 62.Fan H, Zheng L, Yan C, Yang Y. Unsupervised person re-identification: Clustering and fine-tuning. ACM Transactions on Multimedia Computing, Communications, and Applications. 2018 doi: 10.1145/3243316. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Sun Y, Xue B, Zhang M, Yen GG, Lv J. Automatically designing CNN architectures using the genetic algorithm for image classification. IEEE Transactions on Cybernetics. 2020 doi: 10.1109/TCYB.2020.2983860. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Ewees, A. A., Abd El Aziz, M., Elhoseny, M. (2017). Social-spider optimization algorithm for improving ANFIS to predict biochar yield. In 2017 8th International Conference on Computing, Communications and Networking Technologies, IEEE; (pp. 1–6).

- 65.Rizk-Allah RM, Hassanien AE, Elhoseny M. A multi-objective transportation model under neutrosophic environment. Computers & Electrical Engineering. 2018;69:705–719. doi: 10.1016/j.compeleceng.2018.02.024. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 66.El-Hasnony IM, Barakat SI, Elhoseny M, Mostafa RR. Improved feature selection model for big data analytics. IEEE Access. 2020;8:66989–67004. doi: 10.1109/ACCESS.2020.2986232. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Elhoseny M. Intelligent firefly-based algorithm with Levy distribution (FF-L) for multicast routing in vehicular communications. Expert Systems with Applications. 2020;140:112889. doi: 10.1016/j.eswa.2019.112889. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Lydia EL, Raj JS, Pandi Selvam R, Elhoseny M, Shankar K. Application of discrete transforms with selective coefficients for blind image watermarking. Transactions on Emerging Telecommunications Technologies. 2021;32:e3771. doi: 10.1002/ett.3771. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Elhoseny M, Shankar K. Reliable data transmission model for mobile ad hoc network using signcryption technique. IEEE Transactions on Reliability. 2019;69:1077–1086. doi: 10.1109/TR.2019.2915800. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Lakshmanaprabu SK, Elhoseny M, Shankar K. Optimal tuning of decentralized fractional order PID controllers for TITO process using equivalent transfer function. Cognitive Systems Research. 2019;58:292–303. doi: 10.1016/j.cogsys.2019.07.005. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Valayapalayam Kittusamy, S. R., Elhoseny, M., Kathiresan, S. (2019). An enhanced whale optimization algorithm for vehicular communication networks. International Journal of Communication Systems e3953.

- 72.Turkoglu M. COVIDetectioNet: COVID-19 diagnosis system based on X-ray images using features selected from pre-learned deep features ensemble. Applied Intelligence. 2021;51:1213–1226. doi: 10.1007/s10489-020-01888-w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Mirjalili S, Lewis A. The whale optimization algorithm. Advances in Engineering Software. 2016 doi: 10.1016/j.advengsoft.2016.01.008. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Minaee S, Kafieh R, Sonka M, Yazdani S, Jamalipour SG. Deep-COVID: Predicting COVID-19 from chest X-ray images using deep transfer learning. Medical Image Analysis. 2020 doi: 10.1016/j.media.2020.101794. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Cohen, J. P., Morrison, P., Dao, L., Roth, K., Duong, T. Q., Ghassemi, M. (2020). Covid-19 image data collection: Prospective predictions are the future. ArXiv Prepr ArXiv200611988.

- 76.Irvin, J., Rajpurkar, P., Ko, M., Yu, Y., Ciurea-Ilcus, S., Chute, C., et al. (2019). CheXpert: A large chest radiograph dataset with uncertainty labels and expert comparison. 33rd AAAI Conf. Artif. Intell. AAAI 2019, 31st Innov. Appl. Artif. Intell. Conf. IAAI 2019 9th AAAI Symp. Educ. Adv. Artif. Intell. EAAI 2019. 10.1609/aaai.v33i01.3301590.

- 77.Elsayed W, Elhoseny M, Sabbeh S, Riad A. Self-maintenance model for wireless sensor networks. Computers & Electrical Engineering. 2018;70:799–812. doi: 10.1016/j.compeleceng.2017.12.022. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Gaber T, Abdelwahab S, Elhoseny M, Hassanien AE. Trust-based secure clustering in WSN-based intelligent transportation systems. Computer Networks. 2018;146:151–158. doi: 10.1016/j.comnet.2018.09.015. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Zhang B, Niu Z, Wang J, Ji D, Zhou T, Liu Y, et al. Four-hundred gigahertz broadband multi-branch waveguide coupler. IET Microwaves, Antennas and Propagation. 2020;14:1175–1179. doi: 10.1049/iet-map.2020.0090. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Niu, Z. Q., Zhang, B., Li, D. T., Ji, D. F., Liu, Y., Feng, Y. N., et al. (2021). A mechanical reliability study of 3dB waveguide hybrid couplers in the submillimeter and terahertz band. Frontiers of Information Technology & Electronic Engineering, 22, 1104–1113. 10.1631/FITEE.2000229

- 81.Wang Y, Yuan LP, Khishe M, Moridi A, Mohammadzade F. Training RBF NN using sine-cosine algorithm for sonar target classification. Archives of Acoustics. 2020 doi: 10.24425/aoa.2020.135281. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Yang M, Li C, Zhang Y, Jia D, Zhang X, Hou Y, et al. Maximum undeformed equivalent chip thickness for ductile-brittle transition of zirconia ceramics under different lubrication conditions. International Journal of Machine Tools and Manufacture. 2017;122:55–65. doi: 10.1016/j.ijmachtools.2017.06.003. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Berg, H., Hjelmervik, K. T. (2019). Classification of anti-submarine warfare sonar targets using a deep neural network. Ocean. 2018 MTS/IEEE Charleston, Ocean 2018. 10.1109/OCEANS.2018.8604847.

- 84.Aridoss M, Dhasarathan C, Dumka A, Loganathan J. DUICM deep underwater image classification mobdel using convolutional neural networks. International Journal of Grid and High Performance Computing. 2020;12:88–100. doi: 10.4018/IJGHPC.2020070106. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Hall JJ, Azimi-Sadjadi MR, Kargl SG, Zhao Y, Williams KL. Underwater unexploded ordnance (UXO) classification using a matched subspace classifier with adaptive dictionaries. IEEE Journal of Oceanic Engineering. 2019 doi: 10.1109/JOE.2018.2835538. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Liu M, Li C, Cao C, Wang L, Li X, Che J, et al. Walnut fruit processing equipment: academic insights and perspectives. Food Engineering Reviews. 2021;13:1–36. doi: 10.1007/s12393-020-09273-6. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Wang Y, Li C, Zhang Y, Yang M, Li B, Jia D, et al. Experimental evaluation of the lubrication properties of the wheel/workpiece interface in minimum quantity lubrication (MQL) grinding using different types of vegetable oils. Journal of Cleaner Production. 2016;127:487–499. doi: 10.1016/j.jclepro.2016.03.121. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Mahmud T, Rahman MA, Fattah SA. CovXNet: A multi-dilation convolutional neural network for automatic COVID-19 and other pneumonia detection from chest X-ray images with transferable multi-receptive feature optimization. Computers in Biology and Medicine. 2020 doi: 10.1016/j.compbiomed.2020.103869. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The resource images can be downloaded using the following link and references [72]. https://github.com/ieee8023/covid-chestxray-dataset, 2020.

The source code of the models can be available by request.