Abstract

We have evaluated the diagnostic utility of eleven Toxoplasma gondii recombinant antigens (P22 [SAG2], P24 [GRA1], P25, P28 [GRA2], P29 [GRA7], P30 [SAG1], P35, P41 [GRA4], P54 [ROP2], P66 [ROP1], and P68) in immunoglobulin G (IgG) and IgM recombinant enzyme-linked immunosorbent assays (Rec-ELISAs). Following an initial evaluation, six recombinant antigens (P29, P30, P35, P54, P66, and P68) were tested in the IgG and IgM Rec-ELISAs with four groups of samples which span the toxoplasmosis disease spectrum (negative, chronic infection, acute infection, and recent seroconversion). Our results suggest that the combination of P29, P30, and P35 in an IgG Rec-ELISA and the combination of P29, P35, and P66 in an IgM Rec-ELISA can replace the tachyzoite antigen in IgG and IgM serologic tests, respectively. The relative sensitivity, specificity, and agreement for the IgG P29-P30-P35 Rec-ELISA were 98.4, 95.7, and 97.2%, respectively. The resolved sensitivity, specificity, and agreement for the IgM P29-P35-P66 Rec-ELISA were 93.1, 95.0, and 94.5%, respectively. Relative to the tachyzoite-based immunocapture IgM assay, the IgM P29-P35-P66 Rec-ELISA detects fewer samples that contain IgG antibodies with elevated avidity from individuals with an acute toxoplasmosis.

Toxoplasma gondii is a ubiquitous obligate intracellular parasite with a relatively broad host range infecting both mammals and birds (for reviews, see references 21, 32, 48, 54, and 60). Toxoplasmosis is generally asymptomatic in immunocompetent adults, whereas intrauterine transmission of the parasite from the mother to the fetus during gestation can result in severe fetal and neonatal complications (40). Toxoplasmosis is also a serious complication following organ transplantation (D. Aubert, F. Foudrinier, I. Villena, J. M. Pinon, M. F. Biava, and E. Renoult, Letter, J. Clin. Microbiol. 34:1347, 1996) and AIDS (1, 41).

Diagnosis of infection can be established by the isolation of T. gondii from blood or body fluids, demonstration of the parasite in tissues, detection of specific nucleic acid sequences with DNA probes, or detection of T. gondii-specific immunoglobulins synthesized by the host in response to infection using serologic tests (48). The enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) for the detection of immunoglobulins is one of the easiest tests to perform, and many manual and automated serologic tests for the detection of T. gondii-specific immunoglobulin G (IgG) and IgM are commercially available. The currently available tests for the detection of IgG and IgM antibodies in infected individuals vary in their ability to detect serum antibodies (14, 19, 28, 29, 53, 59). The differences observed between these serologic tests is probably due in part to the various preparations of antigen used to detect serum antibody. In fact, different preparations of the tachyzoite antigen (formalin versus acetone fixed) form the basis for the differential agglutination test that is used to discriminate between acute and chronic toxoplasmosis (6). Most commercial kits use prepared tachyzoites grown in mice and/or tissue culture and probably contain varying amounts of extraparasitic material. Due to the lack of a purified standardized antigen or standard method for preparing the antigen, it is not surprising that some interassay variability exists.

Due to the inherent limitations of the tachyzoite antigen in serologic tests, the advent of purified recombinant antigens obtained via molecular biology is an attractive alternative for the detection of serum antibodies. Western blot analysis of the human humoral immune response with the tachyzoite antigen has identified a number of immunoreactive proteins (7, 11, 15, 16, 30, 34, 42, 43, 52, 57, 58). The pattern of immunoreactivity observed by Western blotting with human sera varies with the immunoglobulin class and the stage of infection. Several genes have been cloned that encode T. gondii antigens, as follows: the surface antigens P22 (SAG2) (38, 46) and P30 (SAG1) (3, 12, 24); the dense granule antigens P24 (GRA1) (4), P28 (GRA2) (35, 45), P29 (GRA7) (2, 9, 17), P32 (GRA6) (27, 47), and P41 (GRA4) (33, 55); the rhoptry antigens P54 (ROP2) (31, 51, 56) and P66 (ROP1) (25, 37); and the B10 (36), P25 (22, 55), P35, and P68 antigens (25). These recombinant antigens expressed in bacteria have been used to detect antibodies to the parasite in the serum of humans and animals. In spite of the potential advantages of using recombinant antigens in an ELISA format, only limited studies have combined more than one antigen in an ELISA (18, 23). In this work we evaluate the diagnostic utility of eleven recombinant T. gondii antigens in IgG and IgM recombinant ELISAs (Rec-ELISAs) and describe a cocktail of recombinant antigens to replace the tachyzoite antigen in IgG and IgM serologic tests.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Cloning and expression of T. gondii genes.

The cloning and expression of the toxoplasma genes encoding the P22 (SAG2) (46), P24 (GRA1) (4), P25 (22), P28 (GRA2) (amino acids 107 to 252) (45), P29 (GRA7) (2, 9, 17), P30 (SAG1) (3), P35 (amino acids 1 to 135) (25), P41 (GRA4) (22, 33), P54 (ROP2) (amino acids 177 to 537) (51), P66 (ROP1) (25, 37), and P68 (25) proteins as fusions to the Escherichia coli CKS (CTP:CMP-3-deoxy-d-manno-octulosonate cytidylyl transferase) protein were described previously (2). Bacterial clones expressing the fusion proteins and the control bacterial strain expressing unfused CKS were grown in rich media, and the synthesis of the fusion proteins and CKS was induced as described previously (49). After induction the cells were harvested and the cell pellets were stored at −80°C until protein purification.

Purification of recombinant fusion proteins.

Recombinant antigens produced in E. coli as insoluble inclusion bodies (rp22, rp25, rp29, rp30, rp35, rp41, rp54, and rp66) were purified from cell lysates by a combination of detergent washes followed by solubilization in 8 M urea (49). After solubilization was complete, these soluble proteins were filtered through a 0.2-μm filter and stored at 2 to 8°C, or dialyzed and stored at 2 to 8°C. Recombinant antigens produced in E. coli as soluble proteins (rp24, rp28, and rp68) were purified from cell lysates by ammonium sulfate precipitation followed by DEAE chromatography. The appropriate column fractions were pooled, dialyzed, and stored at 2 to 8°C. The purity of these antigens ranged from 80 to 95%.

Rec-ELISA.

Purified recombinant antigens were individually diluted to the optimized concentration of 5.0 μg per ml in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS), and 0.1 ml of each antigen was added to separate wells of microtiter Maxisorp plates (Nunc, Inc., Naperville, Ill.). When three antigens were coated together in the same well, they were mixed together prior to coating. Control wells for each sera were coated with E. coli lysate at a concentration of 5.0 μg per ml. Coated plates were incubated at 37°C for 1 h, stored overnight at 4°C, washed three times with PBS-Tween 20, washed three times with distilled water, blocked for 2 h at 37°C with blocking solution (3% fish gelatin, 10% fetal calf serum in PBS) and washed three times with distilled water prior to incubation with serum samples. Duplicate serum samples were diluted with a 1:200 dilution into a calf serum buffer containing 2% E. coli lysate. After adding 0.1 ml of diluted sample to each well, the plates were incubated for 1 h at 37°C and then washed three times with PBS-Tween 20 and three times with distilled water. Bound human IgG and IgM were detected by using goat anti-human IgG and IgM horseradish peroxidase-labeled conjugates (Kirkegaard & Perry Laboratories, Inc., Gaithersburg, Md.), respectively. After addition of the appropriate conjugate, the plates were incubated for 1 h at 37°C and then washed three times with PBS-Tween 20 and three times with distilled water. The o-phenylenediamine dihydrochloride color development reagent (Abbott Laboratories, Abbott Park, Ill.), prepared per the manufacturer's directions, was added to each well. After 3 min, the color development reaction was stopped by adding 0.1 ml of 1 N sulfuric acid and the color intensity was read in a microtiter plate reader at 490 nm. The net optical density (OD) was obtained by subtracting the OD for the E. coli lysate control from that of the test with each recombinant antigen. This control procedure ensured that the net OD values obtained were due to the presence or absence of T. gondii-specific IgM or IgG and not due to binding of E. coli antibodies or nonspecific binding. The cutoff for these assays ranged between 2 and 3 standard deviations from the mean of the negative population for each antigen or antigen group.

Toxoplasma serology. (i) Detection of Toxoplasma-specific IgM.

The Abbott IMx Toxo IgM assay was used per manufacturer's directions and an immunocapture IgM assay (IC-M) was used as previously described (44).

(ii) Detection of Toxoplasma-specific IgG.

The Abbott IMx Toxo IgG assay was used per manufacturer's directions and a high sensitivity direct agglutination assay (HSDA) was used as previously described (8). The determination of Toxoplasma IgG avidity was carried out using the BEIA Toxo IgG avidity assay (Bouty, Milan, Italy). Elevated avidity, defined per manufacturer's directions, was greater than 25%, which excludes a primary T. gondii infection within the last three months.

(iii) Detection of Toxoplasma-specific IgA.

An immunocapture IgA assay (IC-A) was used for the detection of Toxoplasma-specific IgA as previously described (41).

Human serum samples. (i) Initial evaluation of Rec-ELISAs.

The Abbott IMx Toxo IgM and IgG assays were used to select three groups of samples for the T. gondii IgM and IgG Rec-ELISA performance evaluation. The Abbott IMx assays discriminate between samples negative or positive for T. gondii-specific IgM and IgG through the use of an assay-specific cutoff which was established in a clinical study. One group of samples was negative for T. gondii IgM and IgG antibody (n = 19), one group was positive for T. gondii IgM antibody (n = 18), and the last group was positive for T. gondii IgG antibody (n = 24).

(ii) Expanded evaluation of Rec-ELISAs.

Four groups of serum samples were used to evaluate the performance of the T. gondii IgM and IgG Rec-ELISAs using the individually coated or multiply coated recombinant antigens. These sera were grouped according to results from T. gondii-specific serologic tests as shown for each group. Group I (n = 200) was composed of samples negative for T. gondii-specific IgM and IgG as measured by the Abbott IMx Toxo IgM and IgG assays. Group II (n = 105) was composed of samples with a serologic profile consistent with a chronic infection (presence of T. gondii-specific IgG and absence of T. gondii-specific IgM as measured by the Abbott IMx Toxo IgG and IgM assays, respectively, and absence of T. gondii IgA as measured by the IC-A assay). Group III (n = 99) was composed of samples with a serologic profile consistent with an acute T. gondii infection (presence of T. gondii IgG as measured by the HSDA assay and presence of T. gondii IgM and IgA as measured by the IC-M and IC-A assays). Group IV (n = 66) was composed of samples from individuals with a recent seroconversion and with a known date of the previous negative IgM and IgG result (absence or low levels of T. gondii IgG (≤10 U/ml) as measured by the HSDA assay and presence of T. gondii IgM and IgA as measured by the IC-M and IC-A assays). Some of the samples in this group were drawn serially from the same individual. Relative sensitivity and specificity were calculated as described by Griner et al. (10). Relative agreement was calculated as follows:

|

where TP, TN, FP, and FN represent the number of true positive, true negative, false positive, and false negative results, respectively.

RESULTS

We cloned and expressed eleven T. gondii recombinant proteins (rp22, rp24, rp25, rp28, rp29, rp30, rp35, rp41, rp54, rp66, and rp68) which previously had been shown to contain epitopes reactive with T. gondii-specific IgG and/or IgM. Each of the antigens was coated separately in the IgG and IgM Rec-ELISAs and tested with 19 serum samples negative for Toxoplasma IgG and IgM antibodies in order to set an assay cutoff. The assay cutoffs were 2 to 3 standard deviations (SD) from the mean of the negative population. Then each IgG and IgM Rec-ELISA was tested with 24 T. gondii IgG-positive samples and 19 T. gondii IgM-positive samples, respectively. The P35 IgG and IgM Rec-ELISAs reacted with the largest total number of IgG-plus-IgM-positive samples, whereas the P68 IgG Rec-ELISA and the P66 IgM Rec-ELISA reacted with the largest number of IgG- and IgM-positive samples, respectively. After this preliminary evaluation and examining the reactivities of the ELISAs with individual samples, we decided to further evaluate the P29, P30, P35, P54, P66, and P68 Rec-ELISAs in a more expanded study. We performed this expanded evaluation of the P29, P30, P35, P54, P66, and P68 Rec-ELISAs in a two-part study using four groups of serum samples. There was overlap of samples from these four groups in both studies. In the first part of the expanded study, we coated each of the antigens separately in individual microtiter wells and established assay cutoffs for the IgG and IgM Rec-ELISAs by testing 200 Toxoplasma IgG- and IgM-negative samples (group I). The assay cutoffs were 2 to 3 SD from the mean of the negative population. The performance of the IgG and IgM Rec-ELISAs was then evaluated by testing the remaining three groups of samples (group II [n = 105], group III [n = 89], group IV [n = 53]). In Table 1 the performance of the six IgG Rec-ELISAs was ranked by the total number of IgG-positive samples that could be detected. As can be seen in Table 1, the P29 IgG Rec-ELISA detected the largest total number of positive samples and the largest number of positive samples in group IV (recent seroconversion). The P30 and P35 IgG Rec-ELISAs detected the next largest number of positive samples. Furthermore, the P30 and P35 IgG Rec-ELISAs detected the largest number of positive samples in group II (chronic infection) and group III (acute infection), respectively. The combination of the P29, P30, and P35 IgG ELISAs yielded a reactivity of 93.1% (230 of 247), which was similar to the reactivity of all six Rec-ELISAs taken together (95.1% [235 of 247]). In Table 2 the performance of the six IgM Rec-ELISAs was ranked by the total number of IgM-positive samples that could be detected. Only results from samples from groups III and IV are shown in Table 2, as the samples in group II were, by definition, IgM negative. Virtually all samples in group II were negative in the IgM Rec-ELISAs (data not shown). As can be seen in Table 2, the P66 IgM Rec-ELISA detected the largest total number of positive samples and the largest number of positive samples in group IV (recent seroconversion). The P35 and P29 IgM Rec-ELISAs detected the next largest number of positive samples. Furthermore, the P29 IgM Rec-ELISA detected the largest number of positive samples in group III (acute infection). The combination of P29, P35, and P66 IgM ELISAs yielded a reactivity of 74.6% (106 of 142) which was similar to the reactivity of all six Rec-ELISAs taken together (76.1% [108 of 142]). The combination of Rec-ELISAs that detected the largest number of IgG-positive samples (P29 plus P30 plus P35) was different from the combination of Rec-ELISAs that detected the largest number of IgM-positive samples (P29 plus P35 plus P66). The reactivity of the combination of the three IgG Rec-ELISAs (93.1%) was higher than the combination of the three IgM Rec-ELISAs (74.6%).

TABLE 1.

Relative rank of T. gondii IgG Rec-ELISA performance

| IgG Rec-ELISA | No. of serum samples positive from group(s):

|

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| II, III, and IV (n = 247) | II (n = 105) | IIIa (n = 89) | IVa (n = 53) | |

| P29 | 206 | 71 | 87 | 48 |

| P30 | 183 | 79 | 78 | 26 |

| P35 | 173 | 39 | 88 | 46 |

| P68 | 171 | 51 | 82 | 38 |

| P66 | 146 | 23 | 78 | 45 |

| P54 | 144 | 51 | 70 | 23 |

| P29-P30-P35 | 230 | 92 | 88 | 50 |

| All | 235 | 95 | 89 | 51 |

Not all group III and IV samples were tested.

TABLE 2.

Relative rank of T. gondii IgM Rec-ELISA performance

| IgM Rec-ELISA | No. of serum samples positive from group(s):

|

||

|---|---|---|---|

| III and IV (n = 142) | IIIa(n = 89) | IVa(n = 53) | |

| P66 | 83 | 44 | 39 |

| P35 | 78 | 41 | 37 |

| P29 | 72 | 49 | 23 |

| P68 | 26 | 12 | 14 |

| P54 | 18 | 13 | 5 |

| P30 | 15 | 7 | 8 |

| P29-P35-P66 | 106 | 64 | 42 |

| All | 108 | 66 | 42 |

Not all group III and IV samples were tested.

We further explored the diagnostic utility of IgG and IgM Rec-ELISAs containing recombinant antigens coated together in the same microtiter well in the second part of the expanded study. In this study the optimal combination of antigens for detection of each immunoglobulin identified in the first part of the expanded study were coated together in the same microtiter wells. The rp29, rp30, and rp35 antigens were coated together in the same microtiter wells for the IgG P29-P30-P35 Rec-ELISA and the rp29, rp35, and rp66 antigens were coated together for the IgM P29-P35-P66 Rec-ELISA. The cutoff for each assay was established by running 200 Toxoplasma IgG- and IgM-negative samples from group I and corresponded to the mean of the negative population plus 2 to 3 SD (IgG assay mean, 0.31; SD, 0.16, cutoff [mean plus 2 SD], 0.63; IgM assay mean, 0.21; SD, 0.10; cutoff (mean plus 3 SD), 0.51). The samples from groups II (n = 100), III (n = 99), and IV (n = 66) were then run in both assays. The results from the IgG P29-P30-P35 Rec-ELISA are shown in Table 3. The reference T. gondii IgG assays, were, for group I and II samples, the IMx Toxo IgG assay, and, for group III and IV samples, the HSDA assay. The relative sensitivity, specificity, and agreement for the Toxo IgG P29-P30-P35 Rec-ELISA were 98.4, 95.7, and 97.2%, respectively. There were a total of 13 samples with discordant results between the Rec-ELISA and the reference assays distributed across three of the four groups of samples, as follows: group I (n = 8); group II (n = 3); and group IV (n = 2).

TABLE 3.

Evaluation of the T. gondii IgG P29-P30-P35 Rec-ELISAa

| Serum groups tested and result by Rec-ELISA (n) | No. of samples with the following result by alternative assayb:

|

|

|---|---|---|

| Pos | Neg | |

| I and II | ||

| Pos (105) | 97 | 8 |

| Neg (195) | 3 | 192 |

| III and IV | ||

| Pos (154) | 153 | 1 |

| Neg (11) | 1 | 10 |

Relative sensitivity, 98.4% (250 of 254). Relative specificity, 95.7% (202 of 211). Relative agreement, 97.2% (452 of 465). Pos, Positive; Neg, Negative.

Groups I and II were tested by the IMx Toxo IgG assay, and groups III and IV were tested by the HSDA IgG assay.

The results from the IgM P29-P35-P66 Rec-ELISA are shown in Table 4. The reference T. gondii IgM assay for group I and group II samples was the IMx Toxo IgM assay and for group III and group IV samples was the IC-M assay. The relative sensitivity, specificity, and agreement for the T. gondii IgM P29-P35-P66 Rec-ELISA were 79.2, 94.9, and 89.7%, respectively. There were a total of 48 samples with discordant results between the Rec-ELISA and the reference assays distributed across the four groups of samples as follows: group I (n = 7), group II (n = 8); group III (n = 30) and group IV (n = 3). The relative sensitivities of the IgM Rec-ELISA were 69.7% (69 of 99) and 96.4% (53 of 55) for group III and group IV samples, respectively. The apparent low sensitivity of the IgM P29-P35-P66 Rec-ELISA was due to the lack of detection of IgM-positive samples in group III (acute infection). We proceeded to further evaluate the 30 group III samples that were positive in the IC-M assay but negative in the IgM P29-P35-P66 Rec-ELISA. Upon resolution testing of these 30 samples with the IMx Toxo IgM assay, 11 were resolved to be negative and 19 were resolved to be positive. All 11 samples resolved negative by the IMx assay contained T. gondii IgG antibodies with elevated avidity. In addition, one sample was from a patient with recrudescence of a previous infection (an IC-M and IMx Toxo IgM false-positive result). Therefore, after resolution testing with the IMx Toxo IgM assay followed by consideration of the patient clinical history, 12 of the 30 group III discordant samples were resolved to be negative. Of the remaining 18 group III samples that were false negative by the IgM P29-P35-P66 Rec-ELISA, 11 samples contained T. gondii IgG antibodies with elevated avidity. These 11 samples with discordant results were excluded from the calculation of resolved sensitivity, specificity, and agreement, as they contained T. gondii IgG antibodies with elevated avidity indicative of a past infection. The resolved data are shown in Table 5. Following resolution of group III false-negative samples and excluding the elevated IgG avidity samples from the calculations, the resolved sensitivity, specificity, and agreement for the T. gondii IgM P29-P35-P66 Rec-ELISA were 93.1, 95.0, and 94.5%, respectively.

TABLE 4.

Evaluation of the T. gondii IgM P29-P35-P66 Rec-ELISAa

| Serum groups tested and result by Rec-ELISA (n) | No. of samples with the following result by alternative assayb:

|

|

|---|---|---|

| Pos | Neg | |

| I and II | ||

| Pos (15) | 0 | 15 |

| Neg (285) | 0 | 285 |

| III and IV | ||

| Pos (123) | 122 | 1 |

| Neg (42) | 32c | 10 |

Relative sensitivity, 79.2% (122 of 154). Relative specificity, 94.9% (295 of 311). Relative agreement, 89.7% (417 of 465). Pos, Positive; Neg, Negative.

Groups I and II were tested by the IMx Toxo IgM assay. Groups III and IV were tested by the IC-M assay.

The 32 samples with false-negative results by the IgM P29-P35-P66 Rec-ELISA came from group III (n = 30) and group IV (n = 2).

TABLE 5.

Evaluation of the T. gondii IgM P29-P35-P66 Rec-ELISA following additional testing

| Result of Rec-ELISA test (n) | No. of samples with the following result after resolution testinga

|

|

|---|---|---|

| Pos | Neg | |

| Pos (138) | 122 | 16 |

| Neg (327) | 20b | 307 |

Only group III false-negative samples were resolved with the IMx Toxo IgM assay. Pos, Positive; Neg, Negative. Resolved sensitivity, 93.1% (122 of 131). Resolved specificity, 95.0% (307 of 323). Resolved agreement, 94.5% (429 of 454).

This number includes two group IV specimens that were false negative. Eleven of the 18 group III samples with false-negative results by the IgM P29-P35-P66 Rec-ELISA contained T. gondii IgG antibodies with elevated avidity and were excluded from the calculation of resolved sensitivity, specificity, and agreement.

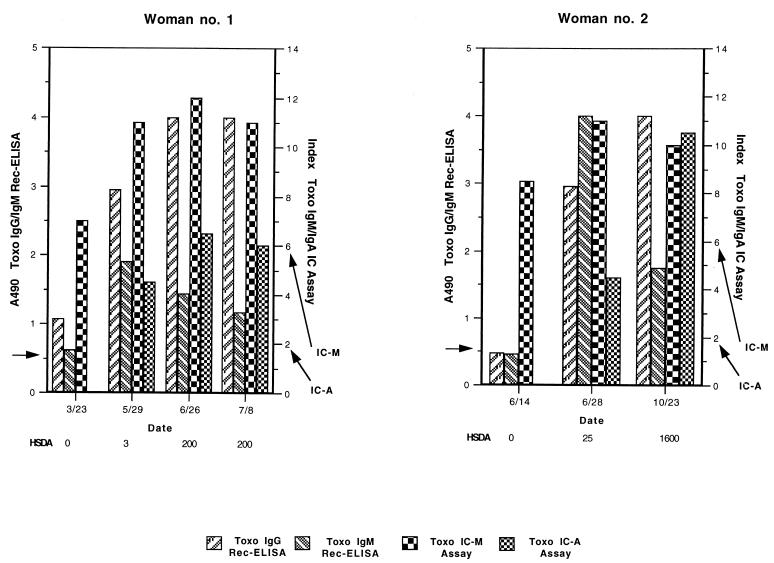

Representative longitudinal profiles of T. gondii IgG (IgG P29-P30-P35 Rec-ELISA and HSDA), T. gondii IgM (IgM P29-P35-P66 Rec-ELISA and IC-M), and T. gondii IgA (IC-A) antibody levels from two women in group IV who experienced a recent seroconversion are shown in Fig. 1. The first serial sample from Woman no. 1 was positive for T. gondii-specific IgG by the IgG P29-P30-P35 Rec-ELISA and positive for Toxo IgM by both the IgM P29-P35-P66 Rec-ELISA and IC-M assay. During the next 4 months as measured across three subsequent serial samples, the IgG and IgA titers became positive by the HSDA and IC-A assays, respectively. The IgM titers began to decline after reaching a peak (at 2 months for the IgM P29-P35-P66 Rec-ELISA [5/29], 3 months for IC-M [6/26]) with the IgM titer declining more rapidly as measured by the IgM P29-P35-P66 Rec-ELISA. Following the first serial sample that was IgA positive, the IgM titer as measured by the IgM P29-P35-P66 Rec-ELISA declined, while the IgA and IgM titers, as measured by the IC-A and IC-M assays, continued to rise. The first serial sample from Woman no. 2 was positive only by the IC-M assay. The IgG and IgM titers, as measured by the respective Rec-ELISAs, were just below the cutoff for both of these assays. Two weeks later at the second serial sample, the IgG, IgM, and IgA titers were positive by all respective assays. Approximately 4 months later, at the third serial sample, the IgG and IgA titers rose while the IgM titer declined.

FIG. 1.

Two representative examples of follow-up of women who experienced an acute toxoplasmosis. These women were followed by the T. gondii IgG P29-P30-P35 Rec-ELISA and IgM P29-P35-P66 Rec-ELISA (vertical bars, first y-axis), the HSDA (9) (indicated below the abscissa of each graph), and by the IC-M and IC-A assays (vertical bars, second y-axis). The cutoffs for the IgG P29-P30-P35 (A490, ≥0.65) and IgM P29-P35-P66 (A490, ≥0.51) Rec-ELISAs are indicated by the left arrow on the first y-axis. The cutoffs for the IC-M (index ≥6) and IC-A (index, ≥2) assays are indicated by the right arrows on the second y-axis as shown. The cutoff for the HSDA assay was 10 IU/ml (not indicated on graph). Toxo, T. gondii. IC, immunocapture.

DISCUSSION

Western blot analysis of the humoral immune response has indicated that antibodies to several T. gondii proteins are produced during infection (7, 11, 15, 16, 30, 34, 42, 43, 52, 57, 58). Many recombinant antigens have been produced and characterized for their ability to bind T. gondii-specific antibodies (2–4, 9, 12, 17, 22, 24, 25, 27, 31, 33, 35–38, 45–47, 51, 55, 56). Previous evaluation of Rec-ELISAs employing different recombinant antigens with patient sera has confirmed the Western blot analysis. However, the exact composition of a recombinant antigen cocktail representative of the entire complex of T. gondii antigens to be used to detect IgG and IgM antibodies in an immunoassay remains an open question. Qualitative and quantitative immunolocalization studies have shown that some T. gondii antigens are located either on the surface membrane (SAG1 and SAG2) (3, 46) or compartmentalized within specific internal organelles, i.e., the rhoptries (ROP1 and ROP2) (13, 37) and dense granules (GRA1, GRA2, GRA4, GRA6, and GRA7) (2, 4, 9, 17, 27, 33, 35). Since a number of the serological targets for the detection of T. gondii antibodies are sequestered within internal organelles, the method of preparation of the tachyzoite antigen has a significant effect on assay performance, as shown by the differential agglutination assay (6). Hence, it is not surprising that commercial tests that employ the tachyzoite antigen to detect serum antibodies exhibit interassay variation (14, 19, 28, 29, 53, 59).

In this work we evaluated the diagnostic utility of IgG and IgM Rec-ELISAs employing 11 recombinant antigens previously described in the literature in order to develop a cocktail of recombinant antigens that could replace the tachyzoite antigen in IgG and IgM serologic tests. In the first part of our study, we screened 11 recombinant antigens for their ability to detect T. gondii-specific IgG and IgM in a Rec-ELISA. After our initial evaluation, we chose to further evaluate the Rec-ELISAs with six candidate antigens (rp29, rp30, rp35, rp54, rp66, and rp68) coated separately. Four groups of samples, which span the toxoplasmosis disease spectrum, were tested: group I (negative), group II (chronic), group III (acute), and group IV (recent seroconversion) (Tables 1 and 2). No single Rec-ELISA containing each antigen was able to detect all IgG- or IgM-positive samples when testing samples across the different disease stages. There are at least two explanations for this result. First, as has been shown by Western blot analysis, the humoral immune response varies with the stage of infection (15, 16, 34, 42, 43, 57). Hence, some antibodies present at one stage of infection may be absent in other stages and vice versa. This requires that multiple epitopes from different antigens be present in an immunoassay to detect the antibodies present in the different disease states. Secondly, it has been our experience that the ability to reconstitute native epitopes in recombinant proteins produced in E. coli is very dependent on the expression vector and protein purification employed (data not shown). Nevertheless, a combination of three IgG Rec-ELISAs (P29 plus P30 plus P35) and three IgM Rec-ELISAs (P29 plus P35 plus P66) was able to detect almost as many IgG- and IgM-positive specimens, respectively, as all six IgG and IgM Rec-ELISAs considered together. From these results we observed that the optimal cocktail of antigens required the inclusion of antigens that were highly reactive across the disease spectrum. For example, in the IgG Rec-ELISA, the rp29, rp30, and rp35 proteins were reactive with the largest number of IgG-positive samples from seroconversion, chronic, and acute infection, respectively (Table 1). Likewise in the IgM Rec-ELISA, the rp29 and rp66 proteins were reactive with the largest number of IgM-positive samples from acute infection and seroconversion, respectively (Table 2). In order to further optimize the IgG and IgM Rec-ELISAs, we coated the appropriate antigens together in the same microtiter well and tested the sera from groups I through IV again. The relative sensitivity of the IgG and IgM Rec-ELISAs improved from 93.1 to 98.4% and from 74.6 to 79.2%, respectively. The sensitivity of the IgM P29-P35-P66 Rec-ELISA, however, remained unacceptably low, and further analysis revealed that the lack of sensitivity was due to failure to detect samples from patients with an acute infection (group III). Since we suspected that the lack of sensitivity of the IgM P29-P35-P66 Rec-ELISA was due to the lack of detection of T. gondii-specific IgM from an older infection, we further characterized the 30 samples in group III that were false negative by the IgM P29-P35-P66 Rec-ELISA by testing them with the IMx Toxo IgM assay and with a commercial IgG avidity assay. The determination of IgG avidity has become a useful tool to exclude an acute toxoplasmosis and is helpful in identifying the approximate stage of infection (5, 20, 26, 39, 50). We found that 22 of the 30 group III samples contained IgG antibodies with elevated avidity, 11 of which were also negative by the IMx Toxo IgM assay. Following this analysis and considering the patient clinical history, the resolved sensitivity of the IgM P29-P35-P66 Rec-ELISA increased from 79.2 to 93.1%. These results were further corroborated by longitudinal analysis of antibody levels from Woman no. 1, where the IgM levels, as measured by the IgM P29-P35-P66 Rec-ELISA declined earlier than those of the IC-M assay (Fig. 1). Thus, relative to the IC-M assay, the IgM P29-P35-P66 Rec-ELISA detects fewer samples that contain IgG antibodies with elevated avidity from individuals with an acute toxoplasmosis.

Two studies have shown that the combination of two T. gondii antigens can increase the sensitivity of Rec-ELISAs. The combination of H4 (P25) and H11 (P41) in an IgG Rec-ELISA have a combined reactivity of 81.3% (23) versus 54 and 61%, respectively, for H4 and H11 alone (55). Likewise, the combination of GRA7 (P29) and Tg34AR (ROP2) in an IgG Rec-ELISA have a combined reactivity of from 93 to 96% versus from 65 to 83% for GRA7 and from 76 to 91% for Tg34AR (18). Our results are consistent with the results of other investigators who have found that combining complementary recombinant T. gondii antigens together in the same immunoassay improves relative assay sensitivity.

In conclusion, we have examined the diagnostic utility of IgG and IgM Rec-ELISAs with several recombinant T. gondii antigens and have identified a cocktail of recombinant antigens that can replace the tachyzoite in serologic tests. These cocktails comprise antigens which previously had been localized to the surface membrane (rp30 [SAG1]), the rhoptry (rp66 [ROP1]) and dense granule organelles (rp29 [GRA7]). Purified recombinant antigens are now available for development of automated T. gondii IgG and IgM immunoassays.

REFERENCES

- 1.Araujo F G, Remington J S. Toxoplasmosis in immunocompromised patients. Eur J Clin Microbiol. 1987;6:1–12. doi: 10.1007/BF02097180. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bonhomme A, Maine G T, Beorchia A, Burlet H, Aubert D, Villena I, Hunt J, Chovan L, Howard L, Brojanac S, Sheu M, Tyner J, Pluot M, Pinon J M. Quantitative immunolocalization of a P29 protein (GRA7), a new antigen of Toxoplasma gondii. J Histochem Cytochem. 1998;46:1411–1421. doi: 10.1177/002215549804601210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Burg J L, Perelman D, Kasper L H, Ware P L, Boothroyd J C. Molecular analysis of the gene encoding the major surface antigen of Toxoplasma gondii. J Immunol. 1988;141:3584–3591. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cesbron-Delauw M F, Guy B, Torpier G, Pierce R J, Lenzen G, Cesbron J Y, Charif H, Lepage P, Darcy F, Lecocq J P, Capron A. Molecular characterization of a 23 kilodalton major antigen secreted by Toxoplasma gondii. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1989;86:7537–7541. doi: 10.1073/pnas.86.19.7537. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cozon G J N, Ferrandiz J, Nebhi H, Wallon M, Peyron F. Estimation of the avidity of immunoglobulin G for routine diagnosis of chronic Toxoplasma gondii infection in pregnant women. Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis. 1998;17:32–36. doi: 10.1007/BF01584360. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Dannemann B R, Vaughan W C, Thulliez P, Remington J S. Differential agglutination test for diagnosis of recently acquired infection with Toxoplasma gondii. J Clin Microbiol. 1990;28:1928–1933. doi: 10.1128/jcm.28.9.1928-1933.1990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Derouin F, Rabian-Herzog C, Sulahian A. Longitudinal study of the specific humoral and cellular response to Toxoplasma gondii in a patient with acquired toxoplasmosis. J Clin Lab Immunol. 1989;30:97–102. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Desmonts G, Remington J S. Direct agglutination test for the diagnosis of Toxoplasma infection: method for increasing sensitivity and specificity. J Clin Microbiol. 1980;11:562–568. doi: 10.1128/jcm.11.6.562-568.1980. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Fischer H G, Stachelhaus S, Sahm M, Meyer H M, Reichmann G. GRA7, an excretory 29 kDa Toxoplasma gondii dense granule protein released by infected host cells. Mol Biochem Parasitol. 1998;91:251–262. doi: 10.1016/s0166-6851(97)00227-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Griner P F, Mayewski R J, Mushlin A I, Greenland P. Selection and interpretation of diagnostic tests and procedures. Principles and applications. Ann Intern Med. 1981;94:557–592. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hafid J, Sung R T M, Akono Z Y, Pozetto B, Jaubert J, Raberin H, Jana M. Toxoplasma gondii antigens: analysis by SDS-PAGE and immunoblotting; relation with circulating antigens. Eur J Protistol. 1991;26:303–307. doi: 10.1016/S0932-4739(11)80151-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Harning D, Spenter J, Metsis A, Vuust J, Petersen E. Recombinant Toxoplasma gondii surface antigen 1 (P30) expressed in Escherichia coli is recognized by human Toxoplasma-specific immunoglobulin M (IgM) and IgG antibodies. Clin Diagn Lab Immunol. 1996;3:355–357. doi: 10.1128/cdli.3.3.355-357.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hérion P, Hernández-Pando R, Dubremetz J F, Saavedra R. Subcellular localization of the 54-kDa antigen of Toxoplasma gondii. J Parasitol. 1993;79:216–222. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hofgartner W T, Swanzy S R, Bacina R M, Condon J, Gupta M, Matlock P E, Bergeron D L, Plorde J J, Fritsche T R. Detection of immunoglobulin G (IgG) and IgM antibodies to Toxoplasma gondii: Evaluation of four commercial immunoassay systems. J Clin Microbiol. 1997;35:3313–3315. doi: 10.1128/jcm.35.12.3313-3315.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Huskinson J, Stepick-Biek P N, Araujo F G, Thulliez P, Suzuki Y, Remington J S. Toxoplasma antigens recognized by immunoglobulin G subclasses during acute and chronic infection. J Clin Microbiol. 1989;27:2031–2038. doi: 10.1128/jcm.27.9.2031-2038.1989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Huskinson J, Thulliez P, Remington J S. Toxoplasma antigens recognized by human immunoglobulin A antibodies. J Clin Microbiol. 1990;28:2632–2636. doi: 10.1128/jcm.28.12.2632-2636.1990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Jacobs D, Dubremetz J F, Loyens A, Bosman F, Saman E. Identification and heterologous expression of a new dense granule protein (GRA7) from Toxoplasma gondii. Mol Biochem Parasitol. 1998;91:237–249. doi: 10.1016/s0166-6851(97)00204-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Jacobs D, Vercammen M, Saman E. Evaluation of recombinant dense granule antigen 7 (GRA7) of Toxoplasma gondii for the detection of immunoglobulin G antibodies and analysis of a major antigenic domain. Clin Diagn Lab Immunol. 1999;6:24–29. doi: 10.1128/cdli.6.1.24-29.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Jenum P A, Stray-Pedersen B. Development of specific immunoglobulins G, M, and A following primary Toxoplasma gondii infection in pregnant women. J Clin Microbiol. 1998;36:2907–2913. doi: 10.1128/jcm.36.10.2907-2913.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Jenum P A, Stray-Pedersen B, Gundersen A G. Improved diagnosis of primary Toxoplasma gondii infection in early pregnancy by determination of antitoxoplasma immunoglobulin G avidity. J Clin Microbiol. 1997;35:1972–1977. doi: 10.1128/jcm.35.8.1972-1977.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Johnson A M. The antigenic structure of Toxoplasma gondii: a review. Pathology. 1985;17:9–19. doi: 10.3109/00313028509063716. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Johnson A M, Illana S. Cloning of Toxoplasma gondii gene fragments encoding diagnostic antigens. Gene. 1991;99:127–132. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(91)90044-c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Johnson A M, Roberts H, Tenter A M. Evaluation of a recombinant antigen ELISA for the diagnosis of acute toxoplasmosis and comparison with traditional ELISAs. J Med Microbiol. 1992;37:404–409. doi: 10.1099/00222615-37-6-404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kim K, Bülow R, Kampmeier J, Boothroyd J C. Conformationally appropriate expression of the Toxoplasma antigen SAG1 (p30) in CHO cells. Infect Immun. 1994;62:203–209. doi: 10.1128/iai.62.1.203-209.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Knapp, S., R. Zlegelmaler, and H. Küpper. 12 June 1991. Toxoplasma gondii antigens, their production and application. European Patent Application 0431541A2.

- 26.Lappalainen M, Koskela P, Koskiniemi M, Ämmälä P, Hiilesmaa V, Teramo K, Raivio K O, Remington J S, Hedman K. Toxoplasmosis acquired during pregnancy: improved serodiagnosis based on avidity of IgG. J Infect Dis. 1993;167:691–697. doi: 10.1093/infdis/167.3.691. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lecordier L, Moleon-Borodowsky I, Dubremetz J F, Tourvieille B, Mercier C, Deslée D, Capron A, Cesbron-Delauw M F. Characterization of a dense granule antigen of Toxoplasma gondii (GRA6) associated to the network of the parasitophorous vacuole. Mol Biochem Parasitol. 1995;70:85–94. doi: 10.1016/0166-6851(95)00010-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Liesenfeld O, Press C, Flanders R, Ramirez R, Remington J S. Study of Abbott IMx system for detection of immunoglobulin G and immunoglobulin M toxoplasma antibodies: value of confirmatory testing for diagnosis of acute toxoplasmosis. J Clin Microbiol. 1996;34:2526–2530. doi: 10.1128/jcm.34.10.2526-2530.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Liesenfeld O, Press C, Montoya J G, Gill R, Isaac-Renton J L, Hedman K, Remington J S. False-positive results in immunoglobulin M (IgM) toxoplasma antibody tests and importance of confirmatory testing: the platelia toxo IgM test. J Clin Microbiol. 1997;35:174–178. doi: 10.1128/jcm.35.1.174-178.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lindenschmidt E G. Demonstration of immunoglobulin M class antibodies to Toxoplasma gondii antigenic component p35000 by enzyme-linked antigen immunosorbent assay. J Clin Microbiol. 1986;24:1045–1049. doi: 10.1128/jcm.24.6.1045-1049.1986. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Martin V, Arcavi M, Santillan G, Amendoeira M R R, De Souza Neves E, Griemberg G, Guarnera E, Garberi J C, Angel S O. Detection of human Toxoplasma-specific immunoglobulins A, M, and G with a recombinant Toxoplasma gondii ROP2 protein. Clin Diagn Lab Immunol. 1998;5:627–631. doi: 10.1128/cdli.5.5.627-631.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.McLeod R, Mack D, Brown C. Toxoplasma gondii: new advances in cellular and molecular biology. Exp Parasitol. 1991;72:109–121. doi: 10.1016/0014-4894(91)90129-k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Mevelec M N, Chardes T, Mercereau-Puijalon O, Bourguin I, Achbarou A, Dubremetz J F, Bout D. Molecular cloning of GRA4, a Toxoplasma gondii dense granule protein recognized by mucosal IgA antibodies. Mol Biochem Parasitol. 1992;56:227–238. doi: 10.1016/0166-6851(92)90172-g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Moir I L, Davidson M M, Ho-Yen D O. Comparison of IgG antibody profiles by immunoblotting in patients with acute and previous Toxoplasma gondii infection. J Clin Pathol. 1991;44:569–572. doi: 10.1136/jcp.44.7.569. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Murray A, Mercier C, Decoster A, Lecordier L, Capron A, Cesbron-Delauw M F. Multiple B-cell epitopes in a recombinant GRA2 secreted antigen of Toxoplasma gondii. Appl Parasitol. 1993;34:235–244. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Nockemann S, Dlugonska H, Henrich B, Kitzerow A, Däubener W. Expression, characterization and serological reactivity of a 41 kDa excreted-secreted antigen (ESA) from Toxoplasma gondii. Mol Biochem Parasitol. 1998;97:109–121. doi: 10.1016/s0166-6851(98)00138-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Ossorio P N, Schwartzman J D, Boothroyd J C. A Toxoplasma gondii rhoptry protein associated with host cell penetration has unusual charge asymmetry. Mol Biochem Parasitol. 1992;50:1–16. doi: 10.1016/0166-6851(92)90239-g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Parmley S F, Sgarlato G D, Mark J, Prince J B, Remington J S. Expression, characterization, and serologic reactivity of recombinant surface antigen P22 of Toxoplasma gondii. J Clin Microbiol. 1992;30:1127–1133. doi: 10.1128/jcm.30.5.1127-1133.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Pelloux H, Brun E, Vernet G, Marcillat S, Jolivet M, Guergour D, Fricker-Hidalgo H, Goullier-Fleuret A, Ambroise-Thomas P. Determination of anti-Toxoplasma gondii immunoglobulin G avidity: adaptation to the Vidas system (bioMérieux) Diagn Microbiol Infect Dis. 1998;32:69–73. doi: 10.1016/s0732-8893(98)00077-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Pinon J M, Chemla C, Villena I, Foudrinier F, Aubert D, Puygauthier-Toubas D, Leroux B, Dupouy D, Quereux C, Talmud M, Trenque T, Potron G, Pluot M, Remy G, Bonhomme A. Early neonatal diagnosis of congenital toxoplasmosis: value of comparative enzyme-linked immunofiltration assay immunological profiles and anti-Toxoplasma gondii immunoglobulin M (IgM) or IgA immunocapture and implications for postnatal therapeutic strategies. J Clin Microbiol. 1996;34:579–583. doi: 10.1128/jcm.34.3.579-583.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Pinon J M, Foudrinier F, Mougeot G, Marx C, Aubert D, Toupance O, Niel G, Danis M, Camerlynck P, Remy G, Frottier J, Jolly D, Bessieres M H, Richard-Lenoble D, Bonhomme A. Evaluation of risk and diagnostic value of quantitative assays for anti-Toxoplasma gondii immunoglobulin A (IgA), IgE, and IgM and analytical study of specific IgG immunodeficient patients. J Clin Microbiol. 1995;33:878–884. doi: 10.1128/jcm.33.4.878-884.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Potasman I, Araujo F G, Desmonts G, Remington J S. Analysis of Toxoplasma gondii antigens recognized by human sera obtained before and after acute infection. J Infect Dis. 1986;154:650–657. doi: 10.1093/infdis/154.4.650. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Potasman I, Araujo F G, Thulliez P, Desmonts G, Remington J S. Toxoplasma gondii antigens recognized by sequential samples of serum obtained from congenitally infected infants. J Clin Microbiol. 1987;25:1926–1931. doi: 10.1128/jcm.25.10.1926-1931.1987. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Pouletty P, Kadouche J, Garcia-Gonzalez M, Mihaesco E, Desmonts G, Thulliez P, Thoannes H, Pinon J M. An anti-human μ chain monoclonal antibody: use for detection of IgM antibodies to Toxoplasma gondii by reverse immunosorbent assay. J Immunol Methods. 1985;76:289–298. doi: 10.1016/0022-1759(85)90306-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Prince J B, Araujo F G, Remington J S, Burg J L, Boothroyd J C, Sharma S D. Cloning of cDNAs encoding a 28 kDa antigen of Toxoplasma gondii. Mol Biochem Parasitol. 1989;34:3–14. doi: 10.1016/0166-6851(89)90014-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Prince J B, Auer K L, Huskinson J, Parmley S F, Araujo F G, Remington J S. Cloning, expression, and cDNA sequence of surface antigen P22 from Toxoplasma gondii. Mol Biochem Parasitol. 1990;43:97–106. doi: 10.1016/0166-6851(90)90134-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Redlich A, Müller W A. Serodiagnosis of acute toxoplasmosis using a recombinant form of the dense granule antigen GRA6 in an enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay. Parasitol Res. 1998;84:700–706. doi: 10.1007/s004360050473. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Remington J S, McLeod R, Desmonts G. Toxoplasmosis. In: Remington J S, Klein J O, editors. Infectious diseases of the fetus and newborn infant. W. B. Philadelphia, Pa: Saunders; 1995. pp. 140–267. [Google Scholar]

- 49.Robinson J M, Pilot-Matias T J, Pratt S D, Patel C B, Bevirt T S, Hunt J C. Analysis of the humoral response to the flagellin protein of Borrelia burgdorferi: cloning of regions capable of differentiating Lyme disease from syphilis. J Clin Microbiol. 1993;31:629–635. doi: 10.1128/jcm.31.3.629-635.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Rossi C L. A simple, rapid enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay for evaluating immunoglobulin G antibody avidity in toxoplasmosis. Diagn Microbiol Infect Dis. 1998;30:25–30. doi: 10.1016/s0732-8893(97)00194-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Saavedra R, De Meuter F, Decourt J L, Hérion P. Human T cell clone identified a potentially protective 54 kDa protein antigen of Toxoplasma gondii cloned and expressed in Escherichia coli. J Immunol. 1991;147:1975–1982. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Sharma S D, Mullenax J, Araujo F G, Erlich H A, Remington J S. Western blot analysis of the antigens of Toxoplasma gondii recognized by human IgM and IgG antibodies. J Immunol. 1983;131:977–983. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Singh S, Singh N, Dwivedi S N. Evaluation of seven commercially available ELISA kits for serodiagnosis of acute toxoplasmosis. Indian J Med Res. 1997;105:103–107. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Smith J. A ubiquitous intracellular parasite: the cellular biology of Toxoplasma gondii. Int J Parasitol. 1995;25:1301–1309. doi: 10.1016/0020-7519(95)00067-c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Tenter A M, Johnson A M. Recognition of recombinant Toxoplasma gondii antigens by human sera in an ELISA. Parasitol Res. 1991;77:197–203. doi: 10.1007/BF00930858. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Van Gelder V, Bosman F, De Meuter F, Van Heuverswyn H, Hérion P. Serodiagnosis of toxoplasmosis by using a recombinant form of the 54-kilodalton rhoptry antigen expressed in Escherichia coli. J Clin Microbiol. 1993;31:9–15. doi: 10.1128/jcm.31.1.9-15.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Verhofstede C, Van Gelder P, Rabaey M. The infection-stage-related IgG response to Toxoplasma gondii studied by immunoblotting. Parasitol Res. 1988;74:516–520. doi: 10.1007/BF00531628. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Weiss L M, Udem S A, Tanowitz H, Wittner M. Western blot analysis of the antibody response of patients with AIDS and Toxoplasma encephalitis: antigenic diversity among Toxoplasma strains. J Infect Dis. 1988;157:7–13. doi: 10.1093/infdis/157.1.7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Wilson M, Remington J S, Clavet C, Varney G, Press C, Ware D. Evaluation of six commercial kits for the detection of human immunoglobulin M antibodies to Toxoplasma gondii. The FDA toxoplasmosis ad hoc working group. J Clin Microbiol. 1997;35:3112–3115. doi: 10.1128/jcm.35.12.3112-3115.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Wong S Y, Remington J S. Biology of Toxoplasma gondii. AIDS. 1993;7:299–316. doi: 10.1097/00002030-199303000-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]