Abstract

Telomeres are complexes of repetitive DNA sequences and proteins constituting the ends of linear eukaryotic chromosomes. While these structures are thought to be associated with the nuclear matrix, they appear to be released from this matrix at the time when the cells exit from G2 and enter M phase. Checkpoints maintain the order and fidelity of the eukaryotic cell cycle, and defects in checkpoints contribute to genetic instability and cancer. The 14-3-3ς gene has been reported to be a checkpoint control gene, since it promotes G2 arrest following DNA damage. Here we demonstrate that inactivation of this gene influences genome integrity and cell survival. Analyses of chromosomes at metaphase showed frequent losses of telomeric repeat sequences, enhanced frequencies of chromosome end-to-end associations, and terminal nonreciprocal translocations in 14-3-3ς−/− cells. These phenotypes correlated with a reduction in the amount of G-strand overhangs at the telomeres and an altered nuclear matrix association of telomeres in these cells. Since the p53-mediated G1 checkpoint is operative in these cells, the chromosomal aberrations observed occurred preferentially in G2 after irradiation with gamma rays, corroborating the role of the 14-3-3ς protein in G2/M progression. The results also indicate that even in untreated cycling cells, occasional chromosomal breaks or telomere-telomere fusions trigger a G2 checkpoint arrest followed by repair of these aberrant chromosome structures before entering M phase. Since 14-3-3ς−/− cells are defective in maintaining G2 arrest, they enter M phase without repair of the aberrant chromosome structures and undergo cell death during mitosis. Thus, our studies provide evidence for the correlation among a dysfunctional G2/M checkpoint control, genomic instability, and loss of telomeres in mammalian cells.

A significant evolutionary conservation is apparent for 14-3-3 proteins in many eukaryotes, ranging from plants to mammals. The 14-3-3 proteins appear to modulate the activity of a large variety of functional proteins and enzymes, many of which are involved in control of cell cycle, cell death, and mitogenesis (1, 45). The 14-3-3 proteins are thought to function as adaptor proteins that allow interaction between signaling proteins that do not associate directly with each other (1). The 14-3-3ς gene was originally identified as an epithelium-specific marker, HME1, which was downregulated in a few breast cancer cell lines but not in cancer cell lines derived from other tissue types (31). Recent data indicate that the expression of 14-3-3ς is lost in 94% of breast tumors (7). At the functional level, the 14-3-3ς protein has been implicated in the G2 checkpoint (13, 30). For instance, its association with different kinases in the cytosol and on the nuclear membrane may contribute to kinase activation during intracellular signaling (44), and the protein appears to sequester the mitotic initiation complex, cdc2-cyclin B1, in the cytoplasm after DNA damage (3). The latter prevents cdc2-cyclin B1 from entering the nucleus, where the protein complex could normally initiate mitosis. Thus, 14-3-3ς has been implicated in maintaining a post-DNA-damage G2 arrest, thereby allowing for DNA repair (3, 13). Such cell-cycle checkpoints are considered to be the guardians of genome integrity, with their abrogation contributing to reduce genomic stability.

Genome stability is also maintained by the telomeres, as these chromosome terminal structures protect the chromosomes from fusions or degradation, as originally reported by Muller (23) and McClintock (19, 20). Human telomeres contain long stretches of a tandemly arranged hexameric sequence, TTAGGG, bound by specific proteins (32). Shortening or loss of telomeric repeats is correlated with chromosome end-to-end associations that could lead to genomic instability and gene amplification (4, 16, 25, 27, 28). Increased chromosome end-to-end associations, or telomeric associations, seen at metaphase, have been reported in cells derived from tumor tissues, senescent cells, the Thiberge Weissenbach syndrome, and ataxia telangiectasia individuals and following viral infections (6, 28, 29). They have been linked to genomic instability and carcinogenicity (4, 28, 29). More recently it was found that telomeric end-to-end fusions were enhanced in cells expressing dominant negative alleles of the human telomeric protein TRF2 (40), and these fusion events also correlated with a loss of telomeric G-strand overhangs.

We were interested to determine whether a normal G2 checkpoint is necessary for chromosome stability in mammalian cells. For this purpose, we studied the link between the 14-3-3ς gene and chromosome behavior, as it relates to a gene involved in the G2 checkpoint after DNA damage. We used isogenic human colorectal cancer cells in which both 14-3-3ς alleles were inactivated and were generated by a somatic-cell knockout approach (3). We found that, indeed, the frequencies of chromosomal aberrations such as telomere-telomere fusions, unbalanced translocations, and chromosomal breaks are higher in 14-3-3ς−/− cells than in the parental 14-3-3ς+/+ cells. These chromosomal aberrations appear mostly to involve losses of telomeric repeats, as a significant number of telomeres fail to hybridize in situ to telomere-specific probes, and signals for telomeric G-strand overhangs are diminished in these cells. Thus, these results are consistent with the idea that abrogating the maintenance of a G2 checkpoint in the 14-3-3ς−/− cells leads to an accumulation of unrepaired chromosomal aberrations, such as losses and subsequent fusion of telomeres, which may be part of the reason for the mitotic catastrophes observed in these cells.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Cells.

Human colorectal cells (HCT116) in which 14-3-3ς alleles are inactivated were obtained from Bert Vogelstein, The Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine, Baltimore, Md. The parental cell line is designated 14-3-3ς+/+, and the derivatives are designated 14-3-3ς+/− and 14-3-3ς−/−. The cells were maintained according to the procedure described recently (3). Three 14-3-3ς−/− derivative clones were analyzed for subsequent experiments. GM02052 was maintained according to the procedure described recently (37).

Clonogenic assays.

Cells in plateau phase growth were plated as single cells into 60-mm dishes in 5.0 ml of medium, incubated for 6 h, and subsequently exposed to ionizing radiation. The number of cells per dish was chosen to ensure that about 50 colonies would survive a particular radiation dose treatment. Cells were exposed to ionizing radiation in the dose range of 0 to 8 Gy at room temperature using a 137Cs γ ray at a dose rate of 1.1 Gy/min. Cells were incubated for 12 or more days and were fixed in methanol-acetic acid (3:1) prior to staining with crystal violet. Only colonies containing >50 cells were counted. The mean plating efficiencies for 14-3-3ς+/+, 14-3-3ς+/−, and 14-3-3ς−/− were 55, 54, and 39%, respectively.

Chromosome studies.

Metaphase chromosomes were prepared by a procedure described earlier (28). Giemsa-stained chromosomes from metaphases were analyzed for chromosome end-to-end associations.

Detection of telomeres and terminal restriction fragment analysis.

Detection of telomeres on metaphases was done by fluorescent in situ hybridization (FISH) using a telomere-specific probe (28). For terminal restriction fragment (TRF) analysis, DNA was isolated from exponentially growing cells by a procedure described earlier (28). This DNA was digested with the restriction enzymes RsaI and HinfI, which do not cut TTAGGG sequences, was processed for fractionation, and was hybridized with a 32P-labeled (TTAGGG)5 probe. Detection and measurement of TRF lengths were performed as described earlier using ImageQuant version 1.2, build 039 (Molecular Dynamics) (37, 38). The nondenaturing in-gel hybridization to determine relative amounts of telomeric single-stranded DNA (G tails) was performed as described previously (21).

Telomerase assay.

Telomerase activity was determined using the telomerase PCR enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) kit (Boehringer Mannheim) as described before (35). Telomerase activity was determined in triplicate, and a negative and a positive control were run with each experiment. As a negative control, an aliquot of each extract was heat inactivated for 10 min at 95°C.

Chromosome-specific changes assessed by SKY.

Spectral karyotyping (SKY) analysis was carried out on chromosomal spreads on freshly dropped slides that were less than 2 months in age. The assay was carried out using the SKY paints according to the manufacturer's instructions (ASI, Carlsbad, Calif.) (36). Briefly, slides were formalin fixed and denatured in 70% formamide–2× SSC (1× SSC is 0.15 M NaCl plus 0.015 M sodium citrate) at 75°C for 2 min. The SKY paints were denatured, preannealed, and hybridized to the denatured slides for 48 h at 37°C. Posthybridization washes and detections were carried out according to the manufacturer's instructions. Spectral images were acquired and analyzed with an SD 200 spectral bioimaging system (ASI, Ltd., Migdal Haemek, Israel) attached to a Zeiss microscope (Axioplan 2; Carl Zeiss Canada). The generation of a spectral image is achieved by acquiring ∼100 frames of the same image that differ from each other only in the optical path difference. The images were stored in a computer for further analysis using the SKYVIEW (version 1.2) (ASI) software. For every chromosomal region, the identity was determined by measuring the spectral emission at that point. Regions where sites for rearrangement or translocation between different chromosomes occurred were visualized by a change in the display color at the point of transition. Pseudocolor classifications were made to aid in the delineation of specific structural aberrations where the display color of different chromosomes might appear quite similar.

Determination of telomere-nuclear matrix association.

Cells in exponential phase were used to prepare the nuclear matrix halos, which were isolated by removing histones and other loosely bound proteins. Nuclear halos are morphologically defined as nuclear structures that remain after the selective removal of perinuclear components with ionic detergent. The halos are thought to represent relaxed loops of DNA with periodical attachment to the nuclear matrix, which is a residual framework of nucleoskeletal proteins. The procedure used for the isolation of lithium diiodosalicylate (LIS)-generated halo structures is a modification of the LIS technique described recently (37). Cells were trypsinized, washed twice with cold phosphate-buffered saline and twice with 25 ml of cold cell wash buffer (CWB; 50 mM KCl, 0.5 mM EDTA, 0.05 mM spermidine, 0.05 mM spermine, 0.25 mM phenylmethylsolfonyl fluoride [PMSF], 0.5% thiodiglycol, 5 mM Tris-HCl [pH 7.4]), pelleted at 1,000 × g for 5 min, and then suspended in 12 ml of CWB containing 0.1% digitonin (Boehringer Mannheim). The cells were passed through a 20-gauge needle, and lysis was monitored by phase-contrast microscopy. The 2-ml suspension was loaded on 3 ml of 10% glycerol cushion in CWB and was spun for 10 min at 800 × g. The nuclei were washed with CWB containing 0.1% digitonin, suspended in CWB and with 0.1% digitonin and 0.5 mM CuSO4 but without EDTA, and incubated for 20 min at 37°C. About 19 volumes of LIS solution (10 mM LIS, 100 mM lithium acetate, 0.1% digitonin, 0.05 mM spermine, 0.125 mM spermidine, 0.25 mM PMSF, 20 mM HEPES-KOH [pH 7.4]) was added, and the mixture was incubated for 10 min at room temperature. Halos were collected by centrifugation for 10 min at 2,800 rpm in a benchtop centrifuge and were washed three times with matrix wash buffer (MWB; 20 mM KCl, 70 mM NaCl, 10 mM MgCl2, 10 mM Tris HCl [pH 7.4]) with 0.1% digitonin. The resulting halo structures contained naked chromosomal DNA and the nuclear matrix. The nuclear halos were then washed with a restriction enzyme buffer, 6 × 106 halos were cleaved in a volume of 0.5 ml containing 1,000 U of the restriction enzyme StyI for 3 h at 37°C, and the nuclear matrices were pelleted by centrifugation. To purify released DNA fragments that were attached to the nuclear matrix, both fractions were treated with proteinase K in a solution containing 10 mM EDTA, 0.5% sodium dodecyl sulfate, and 10 mM Tris-HCl (pH 7.4) and were incubated overnight at 37°C. DNA was purified as described previously (28, 37). Agarose gel electrophoresis was performed for the fractionation of DNA (28, 37). For Southern blot analysis, equal volumes from about 106 halos were fractionated on 0.8% agarose gels. Prior to DNA loading, RNase was added to a final concentration of 10 μg/ml. Fractionation of DNA, transfer to a Hybond-N membrane, or slot blotting of DNA, hybridization with a 32P-labeled (TTAGGG)5 probe, and detection were done as described previously (28, 37). Quantitation and comparison of the telomeric DNA among total (T), released (S), and (P) telomeric DNA fragments attached to the nuclear matrix were achieved by phosphorimaging.

Assay for G1 and G2 checkpoints by examining chromosomal aberrations.

G1-type chromosomal aberrations were assessed as described previously (26). Briefly, cells in plateau phase were irradiated with 3 Gy of gamma rays, allowed to incubate for 24 h, and subcultured, and metaphases were collected. Chromosome spreads were prepared by the procedure described earlier (24). All categories of G1-type asymmetrical chromosome aberrations were scored: dicentrics, centric rings, interstitial deletions/acentric rings, and terminal deletions.

The efficiency of G2 checkpoint control was evaluated by comparing mitotic indices and chromatid-type aberrations at metaphase between the cell types after irradiation. Chromosomal aberrations were assessed by counting chromatid breaks and gaps per metaphase as described previously (22). Cells in exponential phase were irradiated with 1 Gy of gamma ray, and metaphases were collected at 45 and 90 min following irradiation and were examined for chromatid breaks and gaps. Fifty metaphases were scored for each postirradiation time point.

RESULTS

Inactivation of 14-3-3ς influences cell growth and survival after irradiation with gamma rays.

14-3-3ς+/+ and derivatives 14-3-3ς+/− and 14-3-3ς−/− are human colorectal cancer cells that were derived from cell line HCT116 as described recently (3). The parental cells, which express wild-type p53 and 14-3-3ς, have intact DNA damage checkpoints (41). Since the 14-3-3ς protein is involved in G2 checkpoint control, we determined whether inactivation of the 14-3-3ς gene in HCT116 cells influences cell growth by standard growth curve assays. The population doubling time of the 14-3-3ς−/− cells was longer by ∼6 h than that of 14-3-3ς+/− and 14-3-3ς+/+ cells (data not shown). Cells with both alleles of 14-3-3ς inactivated also showed lower cell viability, as monitored by the trypan blue exclusion test, with about 11% nonviable cells (data not shown). This is consistent with the reduced plating efficiency of these cells (∼39% for 14-3-3ς−/− cells, compared to ∼59% for 14-3-3ς+/+ cells).

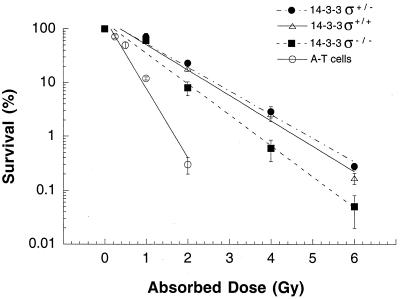

Since 14-3-3ς−/− cells grow more slowly, we examined whether inactivation of 14-3-3ς influences cell survival after irradiation with gamma rays, using colony-forming experiments. Cells with both copies of 14-3-3ς inactivated exhibited an approximately twofold enhancement in ionizing radiation sensitivity for reproductive cell death when compared to 14-3-3ς+/+ cells (Fig. 1). No difference in ionizing radiation sensitivity for reproductive cell death was found in 14-3-3ς+/− cells and 14-3-3ς+/+ cells (Fig. 1), suggesting that cells heterozygous for the 14-3-3ς gene have a phenotype similar to that of the parental cells.

FIG. 1.

Comparison of gamma-ray survival. Dose-response curves are shown for 14-3-3ς−/−, 14-3-3ς+/−, and 14-3-3ς+/+ cells treated with ionizing radiation while growing exponentially and asynchronously. The ataxia telangiectasia (A-T) cell line GM02052 was used as a positive control to indicate radiosensitivity in an exponentially growing asynchronous population.

Inactivation of 14-3-3ς leads to chromosome end-to-end associations and frequent losses of telomeric repeats.

Cells in which both alleles of 14-3-3ς are inactivated grow slowly and exhibit decreased cell survival after gamma ray treatment. It is thus possible that damaged DNA is not repaired appropriately in these cells. To determine whether inactivation of the 14-3-3ς gene influences chromosome behavior, we compared 14-3-3ς+/+, 14-3-3ς+/−, and 14-3-3ς−/− cells for frequencies of chromosome end-to-end associations by analyzing colcemid accumulated cells at metaphase. In human cells, the formation of dicentric chromosomes and other abnormalities created as a consequence of end-to-end fusions have been correlated with losses of telomere function and have been reported for senescent primary cells and in tumor cells (4, 6). In these cases, the chromosomal aberrations correlated with critically shortened telomeres (6). To determine the influence of inactivation of the 14-3-3ς gene on the frequency of chromosome end-to-end associations, 200 metaphases were examined. 14-3-3ς−/− cells had 1.9 chromosome end-to-end associations per metaphase, whereas their parental 14-3-3ς+/+ cells had 0.12 chromosome end-to-end associations per metaphase (Fig. 2 and Table 1). The differences in the frequency of chromosome end-to-end associations between 14-3-3ς−/− and 14-3-3ς+/+ cells are statistically significant. Since chromosome end-to-end associations may lead to anaphase bridge formation, cells without colcemid treatment were analyzed for anaphase bridges. Three hundred cells at anaphase were examined for bridges. 14-3-3ς−/− cells displayed an at least eightfold higher frequency of anaphase bridges than 14-3-3ς+/+ cells (Table 1).

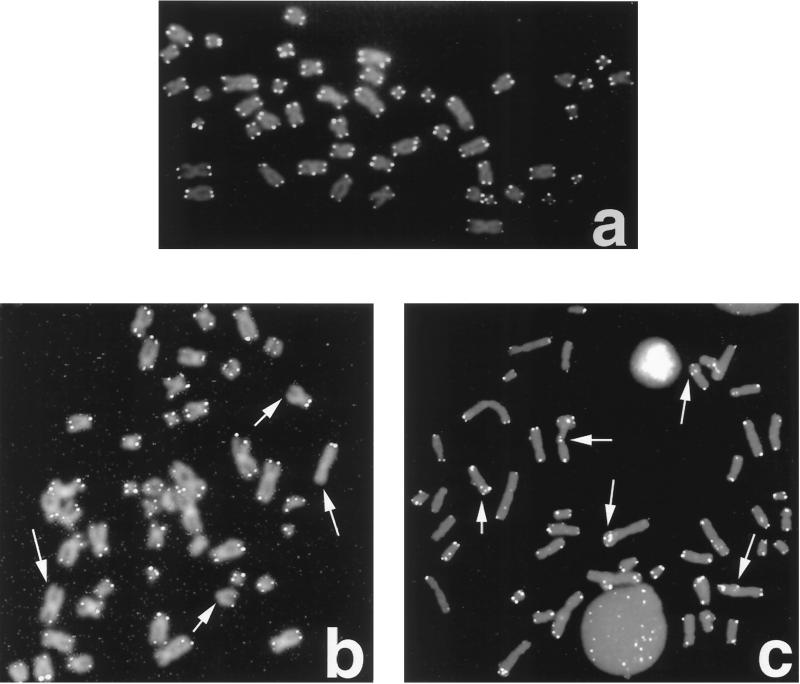

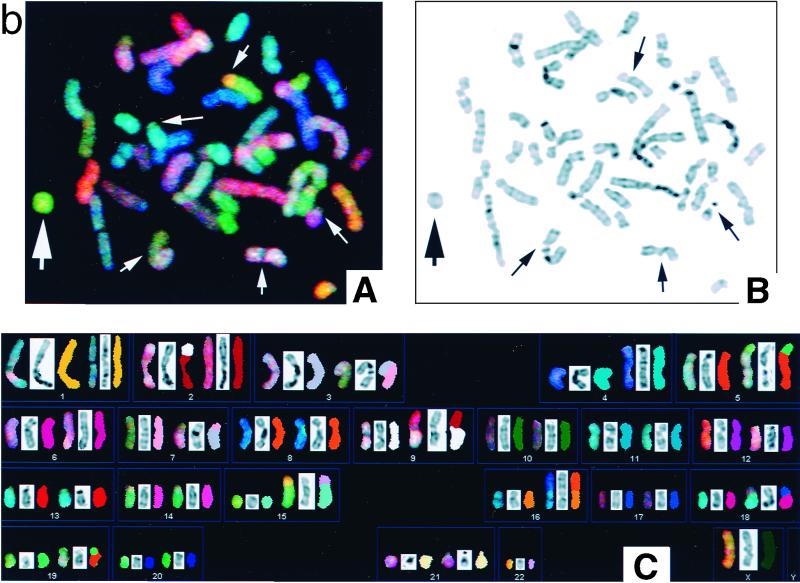

FIG. 2.

Telomere FISH analysis of metaphase chromosomal spreads. 14-3-3ς+/+ (a) and 14-3-3ς−/− (b) cells are shown. Note the absence of telomeric signals in 14-3-3ς−/− cells, as indicated by the arrows. (c) Telomeric signals are present at some telomere fusion sites in 14-3-3ς−/− cells (indicated by arrows).

TABLE 1.

Comparison of frequency of chromosome end-to-end associations at metaphase and bridges at anaphase among three isogenic cell typesa

| Cell type | Chromosome end-to-end associations per 200 metaphases | Bridges per 300 anaphases |

|---|---|---|

| 14-3-3ς+/+ | 24 | 16 |

| 14-3-3ς+/− | 29 | 23 |

| 14-3-3ς−/− | 380 | 130 |

Chromosome end-to-end associations as well as anaphase bridges in 14-3-3ς−/− cells are significantly different from those in 14-3-3ς+/− and 14-3-3ς+/+ cells by chi-square analysis (P < 0.01).

These data suggest that due to occasional losses of telomere function, chromosome end associations are formed, and these associations are not resolved in 14-3-3ς−/− cells. To further examine how inactivation of 14-3-3ς is linked with the loss of telomere function, we examined the sizes of TRFs (see Materials and Methods). By Southern blotting, we found no significant differences in TRF sizes when comparing DNA derived from 14-3-3ς−/− cells with that from 14-3-3ς+/− and 14-3-3ς+/+ cells (Fig. 3). However, this analysis yields an appraisal only of the population of TRFs generated and does not monitor the ends of individual chromosomes. We therefore performed FISH for telomeric repeats on metaphase spreads by using a telomere-specific Cy3-labeled (CCCTAA)3 peptide nucleic acid probe. Fifty metaphase chromosome spreads (184 telomeres per metaphase) from 14-3-3ς+/+ and 14-3-3ς−/− cells were included and analyzed (Fig. 2). A significantly higher proportion of chromatid ends in 14-3-3ς−/− cells (about 11% of telomeres per metaphase) have fewer telomere-specific fluorescent signals than the 14-3-3ς+/+ cells. These observations suggest that the chromosome end-to-end fusions observed in 14-3-3ς−/− cells correlated with losses of telomeric repeats. However, telomere signals were seen in about 18% of the fusion sites, indicating that total loss of telomeres is not required for telomere fusions (Fig. 2).

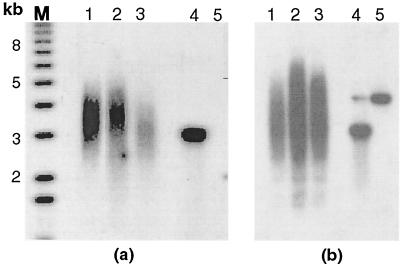

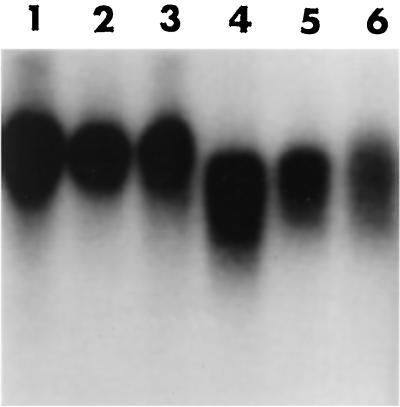

FIG. 3.

Detection of single-strand extension of the G-rich strand and sizes of terminal restriction fragments on DNA derived from 14-3-3ς−/−, 14-3-3ς+/−, and 14-3-3ς+/+ cells. Lane 1, DNA from 14-3-3ς+/− cells; lane 2, DNA from 14-3-3ς+/+ cells; lane 3, DNA from 14-3-3ς−/− cells; lane 4, denatured plasmid DNA (ssDNA) containing telomeric repeats (positive control); lane 5, ds plasmid DNA as a negative control (only lights up once the DNA is denatured, as seen only in Fig. 3b). (a) A nondenaturing hybridization to genomic DNA digested with restriction enzymes HinfI and RsaI. This method allows visualization of G-strand overhangs on telomeres. Signals were quantified by PhosphorImage analysis and were corrected for DNA loading using the rehybridized gel shown in Fig. 3b. Note the difference in the signal intensity in nondenatured gel between 14-3-3ς−/− and 14-3-3ς+/+ cells. (b) Denatured gel was used to compare the TRFs among 14-3-3ς−/−, 14-3-3ς+/−, and 14-3-3ς+/+ cells. Note that no difference in mean TRF is found between the three cell types. M, molecular weight markers.

Normally, mammalian telomeres end in a single-stranded G-tail overhang of about 100 to 200 bases (17, 21). Recently it was shown that these G tails can invade the double-stranded portion of telomeric repeats, forming a D loop (11). This telomeric DNA end structure may be conserved among higher eukaryotes and is required for the association of terminus-specific proteins forming the cap (10, 12). Clearly, if telomeres were fused by end-to-end associations or if telomeric repeats were not present, such as on broken chromosome ends, these G tails would disappear. Such a situation has already been observed to occur as a consequence of overexpressing dominant negative alleles of TRF2 (40). Thus, to assess whether the inactivation of 14-3-3ς also correlates with reduced signals for G tails, we examined the signals for G tails on TRFs of 14-3-3ς−/−, 14-3-3ς+/−, and 14-3-3ς+/+ cells by a nondenaturing in-gel hybridization (17, 21). The advantage of this method is that terminal fragments of any size can be analyzed by using an end-labeled d(CCCTAA)3 probe (Fig. 3). In DNA derived from 14-3-3ς−/− cells, the signal for G tails was significantly and reproducibly reduced, by about 35%, compared to DNA from 14-3-3ς+/+ cells.

A difference in the G tails of telomeres might also be due to alterations in telomerase activity. We examined telomerase activity in extracts of 14-3-3ς+/+ and 14-3-3ς−/− cells by a telomeric repeat amplification protocol-ELISA, which detects the in vitro synthesis of telomeric repeats by telomerase (35). Using this method, no significant differences in telomerase activity between 14-3-3ς−/− and 14-3-3ς+/+ cells were found, indicating that the overall activity of telomerase is not affected by the lack of the 14-3-3ς protein (data not shown). Further, when localization of hTERT was determined by immunostaining using anti-hTERT, no difference was observed between 14-3-3ς−/− and 14-3-3ς+/+ cells (data not shown).

Enhanced chromosome end fusions in cells with inactivated 14-3-3ς correlate with frequent terminal nonreciprocal translocations and ring formations.

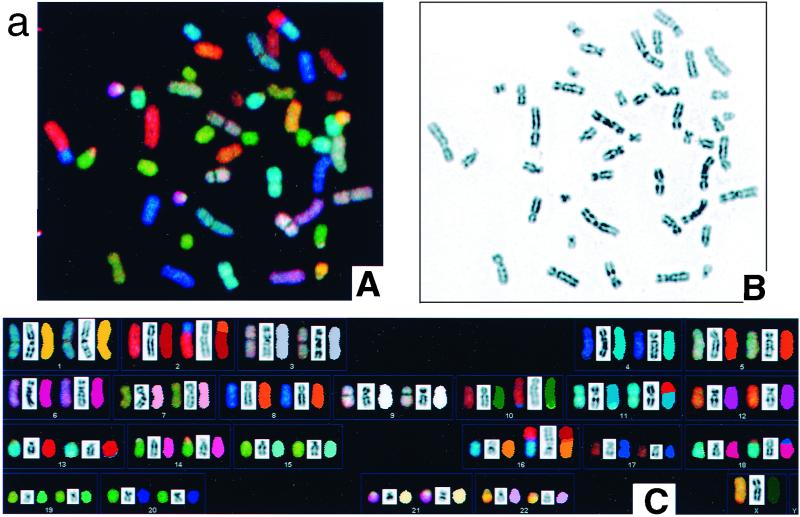

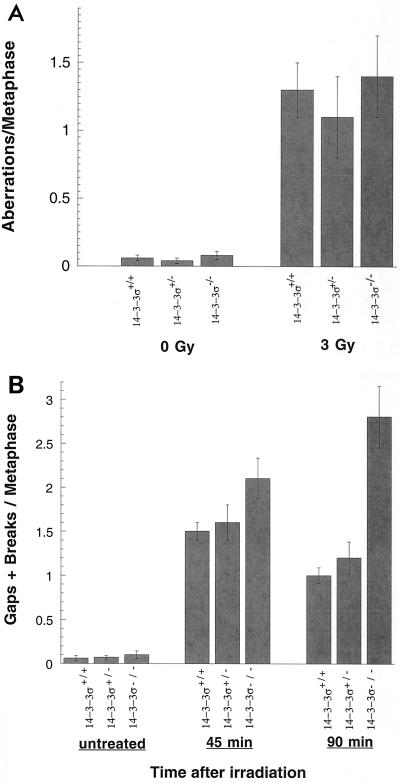

The results described above indicate that inactivation of the 14-3-3ς gene enhances the frequency of observable chromosome end-to-end associations. We next determined whether such chromosome end associations correlate with any other karyotypic changes (Table 1). For each cell type, 200 Giemsa-stained metaphases were examined for spontaneous chromosome breakage. Chromosomal breaks were detected at 2.4-fold-higher levels in the 14-3-3ς−/− cells than in the parental 14-3-3ς+/+ cells (Table 2). Furthermore, in order to assess whether 14-3-3ς−/− cells show specific chromosome fragility, karyotypic changes were determined by SKY. This analysis uses colored fluorescent chromosome-specific paints that provide a complete analysis of possible interchromosomal changes. We found that 14-3-3ς−/− cells had about threefold higher levels of terminal nonreciprocal translocations (Fig. 4). We also found ring chromosomes in 4% of 14-3-3ς−/− cells but not in 14-3-3ς+/+ cells (Fig. 4). The presence of ring structures in 14-3-3ς−/− cells suggests that telomere functions can be simultaneously lost at both ends of the same chromosome, allowing for fusion of the arms of the chromosome.

TABLE 2.

Metaphase chromosomal breaksa

| Cell type | Gaps + breaks per 100 cells

|

|

|---|---|---|

| Chromosome | Chromatid | |

| 14-3-3ς+/+ | 2 | 3 |

| 14-3-3ς+/− | 1 | 5 |

| 14-3-3ς−/− | 2 | 10b |

Two hundred metaphases were examined for each cell type.

Chromatid-type aberration frequencies in the 14-3-3ς−/− cell type are significantly greater by chi-square analysis (P < 0.05) than those of the other cell types.

FIG. 4.

DAPI (4′,6′-diamidino-2-phenylindole) banding and SKY analyses of metaphases in 14-3-3ς+/+ (a) and 14-3-3ς−/− (b) cells. The following descriptions of parts A, B, and C apply to both panels a and b. (A) RGB picture; (B) inverted DAPI staining; (C) SKY and DAPI banding of cells in panels A and B. (a) Karyotype in panel C: [der(2)t(2;8), der(10)dup(10)t(1:10), der(11)t(1;11), t(11;13)/der(11)dup(13), der(16)t(2;8), der(18)t(17;18),21pstk+]. (b) Karyotype in panel C: [t(2;9)(p10;q10), t(3;7)(p10;q110), t(5;19)(p10;p10), der(15;22)(q10;q10), der(16)t(8;160(q13;p13.3), der(18)t(17;18)(q21;p11.3)]. A SKY hybridization and detection kit (SD-200 Bio system; Applied Spectral Imaging Inc.) was used to visualize all human chromosomes in 23 to 24 colors. Chromosomes were analyzed by a combination of Fourier spectroscopy, charge-coupled device imaging, and computerization to excite and measure the emission spectra simultaneously for all dyes in the spectral range and from all points in the metaphase spreads. Images were analyzed by using SKYVIEW software. Note that 14-3-3ς−/− cells have rings and a higher frequency of terminal translocations, as indicated by arrows. In panel b, the large arrow indicates a ring and small arrows indicate translocations and fragments.

The higher frequency of chromosome end fusions could be due to altered chromatin structure in cells with inactivated 14-3-3ς.

To determine whether inactivation of the 14-3-3ς gene influences the telomere nuclear matrix associations, exponentially growing cells were processed by the LIS procedure, and the resulting nuclear matrix halos were cleaved with StyI (see Materials and Methods for details). The nuclear matrix halos are the insoluble nonchromatin scaffolding of the interphase nuclei. The nuclear remnant and associated DNA were separated by centrifugation and were suspended in MWB buffer. For genomic blotting analysis, equal volumes representing DNA from identical numbers of halos were fractionated side by side on 1.5% agarose gels. 14-3-3ς+/+ cells have 56% of the telomeric DNA associated with the nuclear matrix (attached) (P) fraction and 44% in the soluble (free) (S) fraction (Fig. 5). In contrast, 14-3-3ς−/− cells have 71% of the telomeric DNA associated with the nuclear matrix and 29% in the soluble fraction. In both instances, summation of the P and S values is equal to total telomeric DNA (T), suggesting that no telomeric DNA was lost during the extraction procedure. These results suggest that inactivation of 14-3-3ς influences the association of telomeres with the nuclear matrix.

FIG. 5.

Autoradiograph of telomeric DNA in 14-3-3ς+/+ (lanes 1 to 3) cells and 14-3-3ς−/− (lanes 4 to 6) cells. Halo preparation was digested with StyI and centrifuged to separate free (S) (lanes 2 and 5) and pelleted (P) (lanes 3 and 6) telomeric fractions. Note that the summation of P and S values is equal to total (lanes 1 and 3). P and S lanes of 14-3-3ς−/− and P and S lanes of 14-3-3ς+/+ cells represent telomeric DNA from a similar number of halos. Note the difference in the ratio of P versus S fractions of telomere DNA between 14-3-3ς−/− and 14-3-3ς+/+ cells. The results are representative of three separate experiments. Lanes 1 and 4, total telomeric DNA; lanes 2 and 5, soluble fraction; lanes 3 and 6, nuclear matrix fraction.

Observable chromosome aberrations in 14-3-3ς−/− cells correlate with a deficiency of a G2-type but not a G1-type checkpoint.

In 14-3-3ς−/− cells, there is an increased frequency of chromosome end fusions, nonreciprocal translocations, ring chromosome formations, and losses of G tails (see above), indicating frequent loss of telomere functions in these cells. However, it remained unclear whether a defective G2 checkpoint contributes to these losses or whether other changes in these cells could induce general chromosome instability. One way to address this question is to compare cell cycle stage-specific aberrations among 14-3-3ς+/+ and 14-3-3ς−/− cells. Another way to address the same question is to compare the mitotic index of 14-3-3ς−/− cells and 14-3-3ς+/+ cells after treatment with ionizing radiation. Therefore, we first set out to determine the frequencies of chromosome aberrations induced in G1 or in G2 in 14-3-3ς−/− and 14-3-3ς+/+ cells. To determine G1-type chromosome damage, plateau phase cells were treated with 3 Gy of gamma rays and replated 12 h after irradiation, and aberrations were scored at metaphase as described previously (26). We found no differences in residual G1-induced chromosomal aberrations seen at metaphase between 14-3-3ς−/− and 14-3-3ς+/+ cells (Fig. 6A). These results confirm that cells with an inactivated 14-3-3ς gene have a normal G1 checkpoint, evidenced by similar chromosomal repair resulting in similar aberration frequencies. This suggests that the loss of telomere function with subsequent enhanced chromosome aberrations does not occur during the G1-to-S-phase transition in cells with an inactivated 14-3-3ς gene.

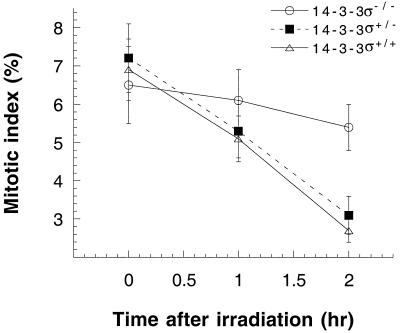

FIG. 6.

G1- and G2-type chromosomal aberrations. (A) Cells in plateau phase were irradiated with 3 Gy, incubated for 24 h postirradiation, and then subcultured, and metaphases were collected. G1-type aberrations were examined at metaphase. All categories of asymmetric chromosome aberrations were scored: dicentrics, centric rings, interstitial deletions/acentric rings, and terminal deletions. The frequency of chromosomal aberrations was low and was identical among 14-3-3ς+/− and 14-3-3ς+/+ cells, and the frequency of other types of aberrations was also identical between the 14-3-3ς−/− and 14-3-3ς+/+ cells, indicating the normal G1 cell-cycle checkpoint. (B) Cells in exponential phase were irradiated with 1 Gy. Metaphases were harvested following irradiation and were examined for chromatid breaks and gaps. Two cell types showed significant differences in the chromosomal aberrations, suggesting that 14-3-3ς−/− has a defective cell-cycle checkpoint.

Since 14-3-3ς has been shown to be involved in a G2 checkpoint after DNA damage, we evaluated the influence of inactivation of the 14-3-3ς gene on ionizing radiation-induced G2-type chromosome aberrations. Cells in exponential phase were irradiated with 1 Gy, and metaphases were examined for chromatid-type breaks and gaps. Cells with both alleles of 14-3-3ς inactivated exhibited a 1.5-fold-increased frequency of G2-type chromatid aberrations at 45 min postirradiation compared to 14-3-3ς+/+ cells, and this difference was increased to 2.8-fold at 90 min (Fig. 6B). In 14-3-3ς+/+ cells, the frequency of G2-type aberrations decreased with longer incubations after irradiation (compare the frequencies for 45 and 90 min postirradiation for these cells [Fig. 6B]), indicating a functional repair system in these cells. However, for 14-3-3ς−/− cells, no such decrease was found, reinforcing the idea that G2-type chromosomal aberrations are not repaired efficiently before onset of mitosis in these cells.

Further, when we examined the mitotic index of 14-3-3ς−/− and 14-3-3ς+/+ cells after 90 min of posttreatment with 2 Gy of gamma rays, we found that cells with an inactivated 14-3-3ς gene had only about a 17% decrease in mitotic index, whereas cells with the 14-3-3ς gene had about a 61% decrease in mitotic index (Fig. 7). These results suggest that a defective G2 checkpoint contributes to mitotic catastrophe.

FIG. 7.

Comparison of the mitotic index among 14-3-3ς−/−, 14-3-3ς+/−, and 14-3-3ς+/+ cells after treatment with 2 Gy of gamma rays. Cells were examined for the frequency of mitotic cells at different time points postirradiation. Note that the frequency of the mitotic index decreased dramatically in 14-3-3ς+/+ and 14-3-3ς+/− cells, whereas the decrease was less in 14-3-3ς−/− cells. Also note the differences in the mitotic index 2 h posttreatment between 14-3-3ς+/+ cells and 14-3-3ς−/− cells; such differences are statistically significant (P > 0.05).

These results suggest that although the 14-3-3ς−/− cells have a functional G1 cell-cycle checkpoint, genetic damage accumulates in G2 following irradiation, which is consistent with a failure to arrest and repair in G2 in response to DNA damage. The frequency of observable spontaneous as well as ionizing radiation-induced chromatid breaks was dramatically higher in 14-3-3ς−/− cells, suggesting that losses of telomere function occurred by breakage near telomeres, rather than by a telomerase-based mechanism.

DISCUSSION

The present studies reveal that in cells with both alleles of the 14-3-3ς gene inactivated, frequent chromosome breakage with complete loss of the telomeric repeats in some chromosomes, as well as chromosome end fusions, ring chromosomes, and reciprocal as well as unbalanced translocations, can be observed. It is important to note that these chromosomal aberrations occurred in cells with normal p53 function that were incubated in normal growth conditions without genotoxic challenges (Fig. 2, 3, and 4 and Table 1). The fact that the p53-mediated G1 checkpoint was operative in these cells is underscored by our findings that γ irradiation induced comparable frequencies of observable chromosome aberrations when 14-3-3ς−/−, 14-3-3ς+/−, or 14-3-3ς+/+ cells were irradiated while in G1 (Fig. 6A). However, there was a clear and significant difference in such aberrations if log-phase cells were irradiated, and mitoses occurring shortly thereafter were monitored; at 90 min after irradiation, there was a 2.8-fold difference in the frequencies of aberrations/metaphase between 14-3-3ς−/− and 14-3-3ς+/+ cells. Furthermore, when the G2-induced aberrations were monitored for the parental cells over time after irradiation, there was a decline in the frequency of aberrations, indicating successful repair of at least some of the induced damage. For 14-3-3ς−/− cells, on the other hand, the frequencies of aberrations increased in the same time span, indicating very inefficient repair (Fig. 6B). Consistent with these data, survival studies demonstrated that 14-3-3ς−/− cells were more sensitive to γ irradiation (Fig. 1).

These data, taken together, reinforce the idea that in human cells, chromosomal damage that might occur during S or G2 phase is recognized by a G2/M checkpoint mechanism. In cells lacking the 14-3-3ς protein, initial G2 cell-cycle arrest after DNA damage is operative, but the cell-cycle arrest cannot be sustained, and the cells will enter mitosis prematurely (3). Our study now reveals that as a consequence of this inability to appropriately repair, such cells enter mitosis with frequent chromosomal aberrations. Thus, abrogation of a sustained G2 cell-cycle arrest after chromosomal damage will lead to genetic instability, a common and recognized prelude to cellular transformation (5). It is noteworthy that the 14-3-3ς−/− cells studied here appear not to adapt to the chromosomal damage, but rather to die in a process called “mitotic catastrophe” (3).

A similar situation has been described for yeast cells: when a single unrepairable double-strand (ds) DNA break is created, cells initially arrest the cell cycle in G2 but will eventually adapt and pass into mitosis with the damaged chromosome (34). However, if there is more than one unrepairable ds DNA break or increased DNA damage due to mutations in repair proteins, yeast cells will not adapt and will remain indefinitely in a poorly characterized G2 state (14). Thus, it is possible that there is too much chromosomal damage in the 14-3-3ς−/− cells, which simply does not allow adaptation to occur. Alternatively, some of the components of the mammalian G2 checkpoints, in particular the 14-3-3 genes, may be involved in regulating adaptation (3, 15, 39). Consistent with the latter, there is increasing evidence to suggest that in yeast and humans, initial arrest and maintenance of the G2 checkpoint are distinct mechanisms (3, 9).

About 18% of the chromosome end-to-end associations that we observed in 14-3-3ς−/− cells did contain telomeric sequences at the fusion points (Fig. 2). Furthermore, we documented alterations in telomere-nuclear matrix associations and a significant loss of G tails at the telomeres in these cells (Fig. 3 and 5). These results suggest that at least part of the accumulating damage in 14-3-3ς−/− cells is specific to telomeric regions.

The 14-3-3 proteins constitute a highly conserved isoform of hetero- and homodimeric molecules that are associated with signaling proteins. 14-3-3ς does not seem to be influencing telomerase activity, as we did not find a significant difference in telomerase activity when extracts derived from 14-3-3ς−/− cells were compared to those of parental cells (data not shown), suggesting that the effects observed (loss of telomeres) are not due merely to a telomerase defect. We speculate that the 14-3-3ς protein may, directly or indirectly, play a role in coordinating the specific chromatin remodeling events leading up to mitosis. Thus, even in cells without genotoxic challenges, the dynamic telomere-nuclear matrix associations may not be regulated appropriately in G2, leading to chromosome breaks with complete loss of telomeric sequences or nonfunctional telomeres that will induce telomere fusions.

For yeast, there is also evidence for dynamic changes in telomeric chromatin in late S/G2. First, telomeric regions are very late replicating, and dynamic changes of the terminal DNA structures have been documented to occur at the end of S phase (8, 18, 42, 43). Second, these changes in the terminal DNA structures roughly coincide in time with an altered accessibility of telomeric chromatin to set up a telomeric heterochromatin-like domain (2).

Telomere associations have been observed at G1, G2, and metaphase in different cell types (27, 28). Several reports suggest that chromosome end-fusions occur in cells with very short telomeres (4, 33). However, shortening of telomeres is not an absolute requirement for telomere end fusions, as 14-3-3ς−/− and 14-3-3ς+/+ cells have telomeres of similar size, and telomeric repeat signals were detected at some of the fusion sites (Fig. 2). Similar findings have been documented for cells with inactivated ATM function, with another gene involved in G2/M progression, and for cells expressing a dominant negative mutant form of TRF2 (37, 38, 40).

Our results are thus consistent with a model that predicts that telomere function in mammalian cells is exquisitely sensitive to perturbations of cell-cycle regulation and chromatin remodeling during G2. We speculate that it may be the functioning p53 checkpoint in the 14-3-3ς−/− cells that causes these cells to die rather than adapt to the genetic instabilities reported here. Since inactivation of the 14-3-3ς gene leads to radiosensitivity, genomic instability, and loss of telomeres, further experiments are needed to reveal the players in 14-3-3ς damage response.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This investigation was supported by NS34746 (T.K.P.). R.J.W. is a chercheur boursier sénior of the Fonds de la Recherche en Santé du Québec (FRSQ) and acknowledges support by the Canadian NCI (grant #010049).

Thanks are due to Bert Vogelstein for providing reagents and Raj Pandita for her advice and help.

REFERENCES

- 1.Aitkin A. 14-3-3 proteins on the MAP. Trends Cell Biol. 1996;6:341–347. doi: 10.1016/0962-8924(96)10029-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Aparicio O M, Gottschling D E. Overcoming telomeric silencing: a trans-activator competes to establish gene expression in a cell cycle-dependent way. Genes Dev. 1994;18:1133–1146. doi: 10.1101/gad.8.10.1133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Chan T A, Hermakin H, Lengauer C, Kinzler K W, Vogelstein B. 14-3-3ς is required to prevent mitotic catastrophe after DNA damage. Nature. 1999;401:616–620. doi: 10.1038/44188. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Counter C M, Avilion A A, LeFeuvre C E, Stewart N G, Greider C W, Harley C B, Bacchetti S. Telomere shortening associated with chromosome instability is arrested in immortal cells which express telomerase activity. EMBO J. 1992;11:1921–1929. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1992.tb05245.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Dasika G K, Lin S C, Zhao S, Sung P, Tomkinson A, Lee E Y. DNA damage-induced cell cycle checkpoints and DNA strand break repair in development and tumorigenesis. Oncogene. 1999;18:7883–7899. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1203283. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.de Lange T. Telomere dynamics and genome instability in human cancer. In: Blackburn E H, Greider C W, editors. Telomeres. Cold Spring Harbor, N.Y: Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press; 1995. pp. 265–297. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ferguson A T, Evron E, Umbricht C, Pandita T K, Hermeking H, Marks J, Futreal A, Stampfer M R, Sukumar S. High frequency of hypermethylation at the 14-3-3ς locus leads to gene silencing in breast cancer. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2000;97:6049–6054. doi: 10.1073/pnas.100566997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ferguson B M, Brewer B J, Reynolds A E, Fangman W L. A yeast origin of replication is activated late in S phase. Cell. 1991;65:507–515. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(91)90468-e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gardner R, Putnam C W, Weinert T. RAD53, DUN1 and PDS1 define two parallel G2/M checkpoint pathways in budding yeast. EMBO J. 1999;18:3173–3185. doi: 10.1093/emboj/18.11.3173. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Greider C W. Telomeres do D-loop-T-loop. Cell. 1999;97:419–422. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80750-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Griffith J D, Comeau L, Rosenfield S, Stansel R M, Bianchi A, Moss H, de Lange T. Mammalian telomeres end in a large duplex loop. Cell. 1999;97:503–514. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80760-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Henderson E R, Blackburn E H. An overhanging 3′ terminus is a conserved feature of telomeres. Mol Cell Biol. 1989;9:345–348. doi: 10.1128/mcb.9.1.345. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hermeking H, Lengauer C, Polyak K, He T-C, Zhang L, Thiagalingam S, Kinzler K W, Vogelstein B. 14-3-3ς is a p53-regulated inhibitor of G2/M progression. Mol Cell. 1997;1:3–11. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(00)80002-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lee S E, Moore J K, Holmes A, Umezu K, Kolodner R D, Haber J E. Saccharomyces Ku70, mre11/rad50 and RPA proteins regulate adaptation to G2/M arrest after DNA damage. Cell. 1998;94:399–409. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81482-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lopez-Girona A, Furnari B, Mondesert O, Russell P. Nuclear localization of Cdc25 is regulated by DNA damage and a 14-3-3 protein. Nature. 1999;397:172–175. doi: 10.1038/16488. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ma C, Martin S, Trask B, Hamlin J L. Sister chromatid fusion initiates amplification of the dihydrofolate reductase gene in Chinese hamster cells. Genes Dev. 1993;7:605–620. doi: 10.1101/gad.7.4.605. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Makarov V, Hirose Y, Langmore J P. Long G tails at both ends of human chromosomes suggest a C strand degradation mechanism for telomere shortening. Cell. 1997;88:657–666. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81908-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.McCarroll R M, Fangman W L. Time of replication of yeast centromeres and telomeres. Cell. 1988;54:505–513. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(88)90072-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.McClintock B. The stability of broken ends of chromosomes in Zea mays. Genetics. 1941;26:234–282. doi: 10.1093/genetics/26.2.234. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.McClintock B. The fusion of broken ends of chromosomes following nuclear fusion. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1942;28:458–463. doi: 10.1073/pnas.28.11.458. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.McElligott R, Wellinger R J. The terminal DNA structure of mammalian chromosomes. EMBO J. 1997;16:3705–3714. doi: 10.1093/emboj/16.12.3705. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Morgan S E, Lovly C, Pandita T K, Shiloh Y, Kastan M B. Fragments of ATM which have dominant-negative or complementing activity. Mol Cell Biol. 1997;17:2020–2029. doi: 10.1128/mcb.17.4.2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Muller H J. The remaking of chromosomes. Collecting Net. 1938;13:181–195. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Pandita T K. Effect of temperature variation on sister chromatid exchange frequency in cultured human lymphocytes. Hum Genet. 1983;63:189–190. doi: 10.1007/BF00291543. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Pandita T K, DeRubeis D. Spontaneous amplification of interstitial telomeric bands in Chinese hamster ovary cells. Cytogenet Cell Genet. 1995;68:95–101. doi: 10.1159/000133899. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Pandita T K, Geard C R. Chromosome aberrations in human fibroblasts induced by monoenergetic neutrons. I. Relative biological effectiveness. Radiat Res. 1996;145:730–739. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Pandita T K, Hall E J, Hei T K, Piatyszek M A, Wright W E, Piao C Q, Pandita R K, Willey J C, Geard C R, Kastan M B, Shay J W. Chromosome end-to-end associations and telomerase activity during cancer progression in human cells after treatment with alpha-particles simulating radon progeny. Oncogene. 1996;13:1423–1430. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Pandita T K, Pathak S, Geard C R. Chromosome end associations, telomeres and telomerase activity in ataxia telangiectasia cells. Cytogenet Cell Genet. 1995;71:86–93. doi: 10.1159/000134069. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Pathak S, Wang Z, Dhaliwal M K, Sacks P C. Telomeric association; another characteristic of cancer chromosomes. Cytogenet Cell Genet. 1988;47:227–229. doi: 10.1159/000132555. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Piwnica-Worms H. Cell cycle. Fools rush in. Nature. 1999;401:535–536. doi: 10.1038/44029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Prasad G L, Valverius E M, McDuffie E, Cooper H L. Complementary DNA cloning of a novel epithelial cell marker protein, HMEI, that may be down-regulated in neoplastic mammary cells. Cell Growth Differ. 1992;3:507–513. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Price C M. Telomeres and telomerase: broad effects on cell growth. Curr Opin Genet Dev. 1999;9:218–224. doi: 10.1016/S0959-437X(99)80032-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Saltman D, Morgan R, Cleary M L, de Lange T. Telomeric structure in cells with chromosome end associations. Chromosoma. 1993;102:121–128. doi: 10.1007/BF00356029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Sandell L L, Zakian V A. Loss of a yeast telomere: arrest, recovery, and chromosome loss. Cell. 1993;75:729–739. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(93)90493-a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Sawant S G, Gregoire V, Dhar S, Umbricht C B, Cvilic S, Sukumar S, Pandita T K. Telomerase activity as a measure for monitoring radiocurability of tumor cells. FASEB J. 1999;13:1047–1054. doi: 10.1096/fasebj.13.9.1047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Schrock E, du Manoir S, Veldman T, Schoell B, Wienberg J, Ferguson-Smith M A, Ning Y, Ledbetter D H, Bar-Am I, Soenksen D, Garini Y, Ried T. Multicolor spectral karyotyping of human chromosomes. Science. 1996;273:494–497. doi: 10.1126/science.273.5274.494. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Smilenov L B, Dhar S, Pandita T K. Altered telomere nuclear matrix interactions and nucleosomal periodicity in cells derived from individuals with ataxia telangiectasia before and after ionizing radiation treatment. Mol Cell Biol. 1999;19:6963–6971. doi: 10.1128/mcb.19.10.6963. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Smilenov L B, Morgan S E, Mellado W, Sawant S G, Kastan M B, Pandita T K. Influence of ATM function on telomere metabolism. Oncogene. 1997;15:2659–2665. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1201449. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Toczyski D P, Galgoczy D J, Hartwell L H. CDC5 and CKII control adaptation to the yeast DNA damage checkpoint. Cell. 1997;90:1097–10106. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80375-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.van Steensel B, Smogorzewska A, de Lange T. TRF2 protects human telomeres from end-to-end fusions. Cell. 1998;92:401–413. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80932-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Waldman T, Kinzler K W, Vogelstain B. p21 is necessary for the p53 mediated G1 arrest in human cancer cells. Cancer Res. 1995;55:5187–5190. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Wellinger R J, Wolf A J, Zakian V A. Origin activation and formation of single-strand TG1–3 tails occur sequentially in late S phase on a yeast linear plasmid. Mol Cell Biol. 1993;13:4057–4065. doi: 10.1128/mcb.13.7.4057. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Wellinger R J, Wolf A J, Zakian V A. Saccharomyces telomeres acquire single-strand TG1–3 tails late in S phase. Cell. 1993;72:51–60. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(93)90049-v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Xing H, Kornfield K, Muslin A J. The protein kinase KSR interacts with 14-3-3 protein and Raf. Curr Biol. 1997;7:294–300. doi: 10.1016/s0960-9822(06)00152-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Zha J, Harada H, Yang E, Jockel J, Korsmeyer S J. Serine phosphorylation of death agonist BAD in response to survival factor results in binding to 14-3-3 not BCL-X. Cell. 1996;87:619–628. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81382-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]