ABSTRACT

Acinetobacter baumannii is a successful nosocomial pathogen due to its genomic plasticity. Homologous recombination allows genetic exchange and allelic variation among different clonal lineages and is one of the mechanisms associated with horizontal gene transfer (HGT) of resistance determinants. The main mechanism of colistin resistance in A. baumannii is mediated through mutations in the pmrCAB operon. Here, we describe two A. baumannii clinical isolates belonging to International Clone 7 (IC7) that have undergone recombination in the pmrCAB operon and evaluate the contribution of mobile genetic elements (MGE) to this phenomenon. Isolates 67569 and 72554 were colistin susceptible and resistant, respectively, and were submitted for short- and long-read genome sequencing using Illumina MiSeq and MinION platforms. Hybrid assemblies were built with Unicycler, and the assembled genomes were compared to reference genomes using NUCmer, Cortex, and SplitsTree. Genomes were annotated using Prokka, and MGEs were identified with ISfinder and repeat match. Both isolates presented a 21.5-kb recombining region encompassing pmrCAB. In isolate 67659, this region originated from IC5, while in isolate 72554 multiple recombination events might have happened, with the 5-kb recombining region encompassing pmrCAB associated with an isolate representing IC4. We could not identify MGEs involved in the mobilization of pmrCAB in these isolates. In summary, A. baumannii belonging to IC7 can present additional sequence divergence due to homologous recombination across clonal lineages. Such variation does not seem to be driven by antibiotic pressure but could contribute to HGT mediating colistin resistance.

IMPORTANCE Colistin resistance rates among Acinetobacter baumannii clinical isolates have increased over the last 20 years. Despite reports of the spread of plasmid-mediated colistin resistance among Enterobacterales, the presence of mcr-type genes in Acinetobacter spp. remains rare, and reduced colistin susceptibility is mainly associated with the acquisition of nonsynonymous mutations in pmrCAB. We have recently demonstrated that distinct pmrCAB sequences are associated with different A. baumannii International Clones (IC). In this study, we identified the presence of homologous recombination as an additional cause of genetic variation in this operon, which, to the best of our knowledge, was not mediated by mobile genetic elements. Even though this phenomenon was observed in both colistin-susceptible and -resistant isolates, it has the potential to contribute to the spread of resistance-conferring alleles, leading to reduced susceptibility to this last-resort antimicrobial agent.

KEYWORDS: polymyxins, colistin resistance, mobile genetic elements, insertion sequences, Gram-negative bacilli

INTRODUCTION

Acinetobacter baumannii is an opportunistic pathogen causing a variety of difficult-to-treat infections owing to their high incidence of antimicrobial resistance. One of the reasons for this is its high genomic plasticity and its ability to acquire resistance determinants (1, 2). The A. baumannii population can be grouped into nine international clonal lineages (3), which differ from each other in at least 1,800 alleles, as shown by core genome multilocus sequence typing (cgMLST) (4). Furthermore, each lineage has distinct alleles associated with them, such as the intrinsic blaOXA-51-like (5).

Homologous recombination allows foreign DNA to be integrated into the chromosome, and in A. baumannii it has already been associated with the acquisition of resistance determinants to aminoglycosides (6, 7). Additionally, other studies have shown that homologous recombination contributes to the allelic variation of intrinsic resistance determinants, such as the outer membrane protein CarO (8) and the chromosome-encoded Acinetobacter-derived cephalosporinase (ADC) (9).

Mutations in the pmrCAB operon are the main mechanism causing reduced susceptibility to colistin among A. baumannii strains (10). We have recently demonstrated the allelic variation of pmrCAB between distinct International Clones (ICs) and that colistin-susceptible isolates belonging to the same clonal lineage should be used as reference strains when investigating point mutations potentially associated with colistin resistance (11, 12). Interestingly, some of the IC2 isolates described in the study by Gerson and colleagues (11) presented pmrCAB sequences that are associated with IC4, suggesting homologous recombination between these clonal lineages. Kim and Ko (13) have also suggested that pmrCAB genetic variation between distinct species belonging to the A. baumannii-A. calcoaceticus complex was due to recombination.

Here, we describe two A. baumannii clinical isolates belonging to IC7 with distinct colistin susceptibility profiles and presenting recombined pmrCAB operons and evaluate the contribution of mobile genetic elements (MGE) to this phenomenon.

(This work was presented in part at the 12th International Symposium on the Biology of Acinetobacter in Frankfurt, Germany, 2019)

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

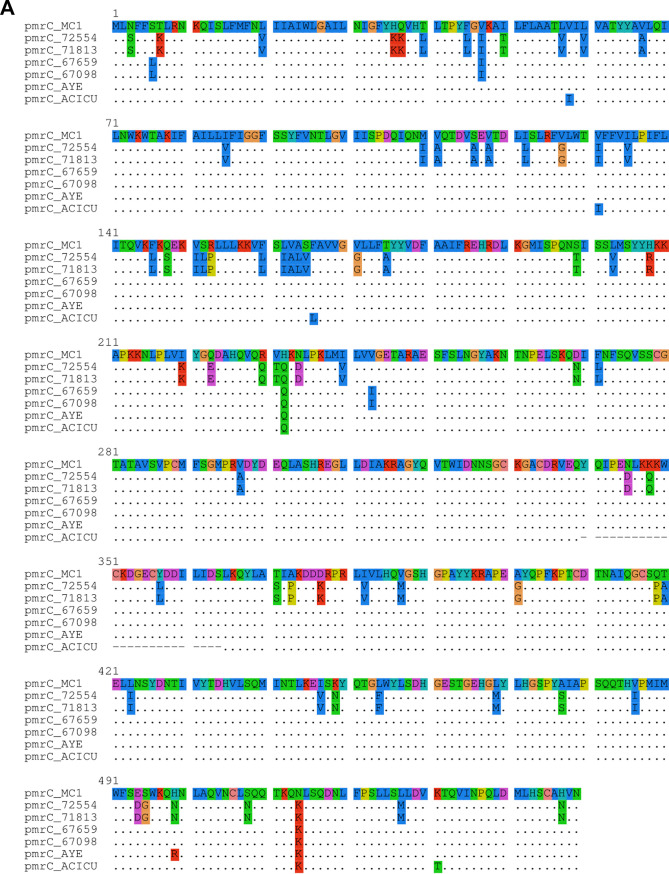

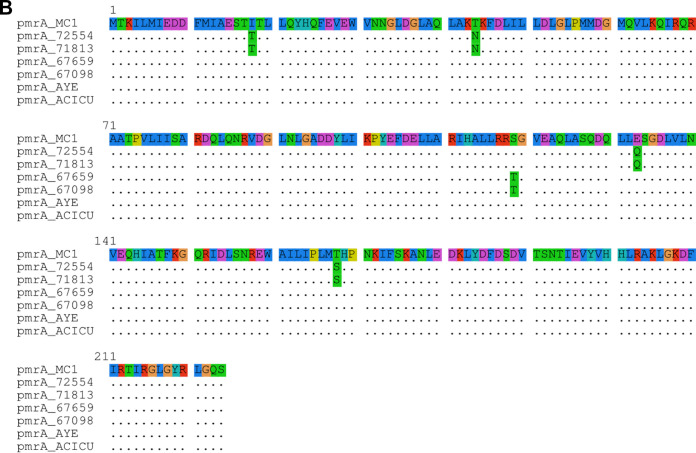

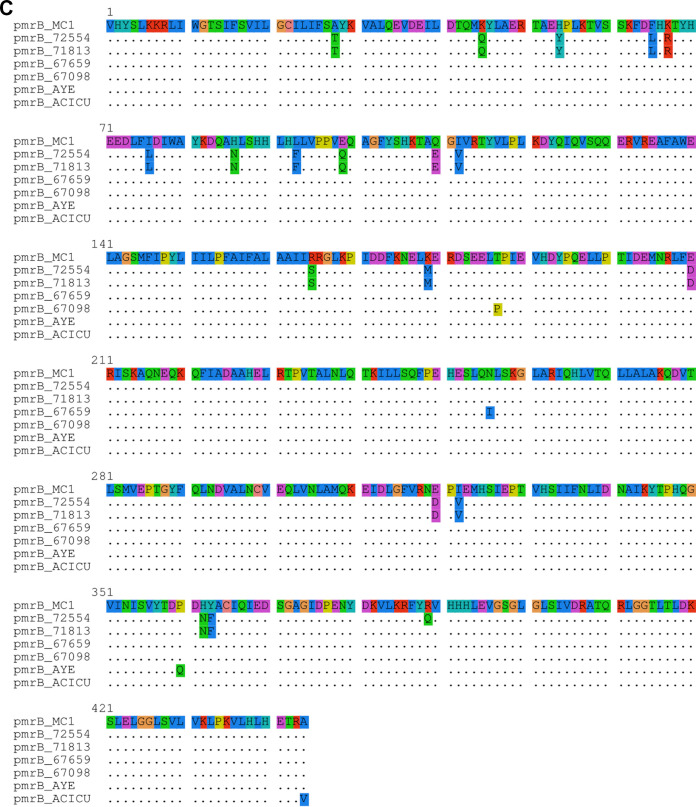

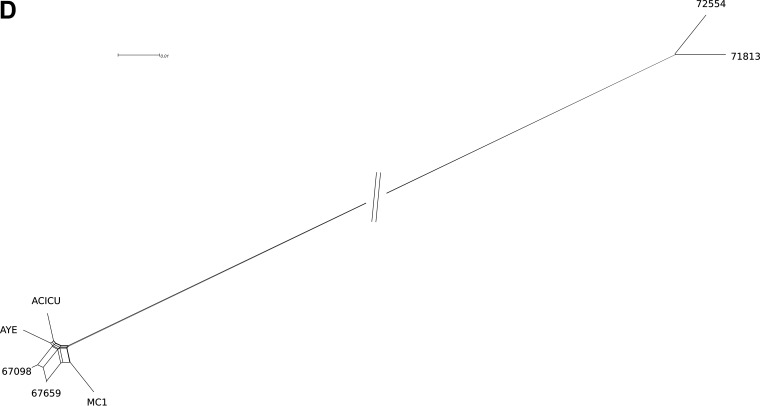

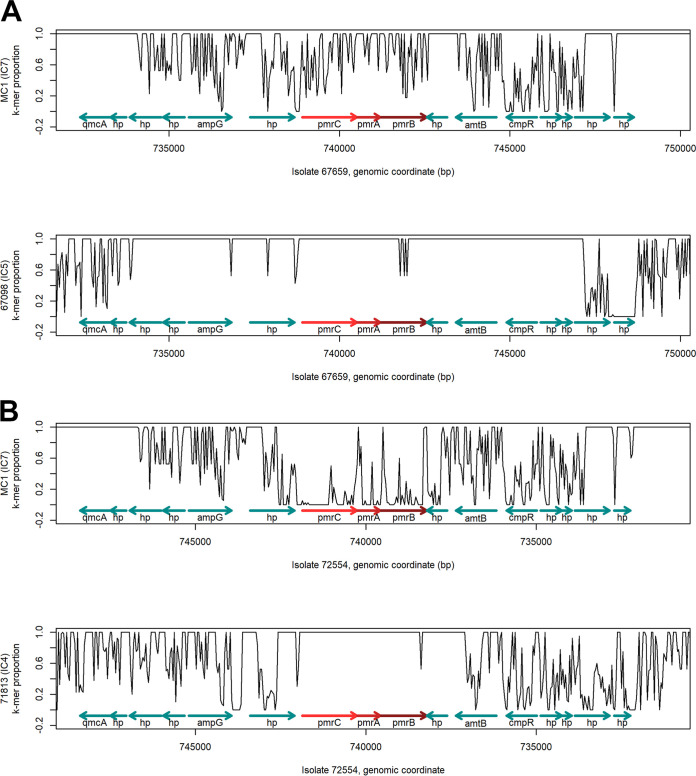

Some divergence was observed when the PmrCAB protein sequences of the IC7 isolates 67659 and 72554 were aligned against MC1 (IC7 reference genome). The colistin-susceptible isolate 67659 showed one amino acid substitution in both PmrA and PmrB as well as five in PmrC. In contrast, isolate 72554 presented 4, 18, and 71 amino acid substitutions in PmrA, PmrB, and PmrC, respectively (Fig. 1A to C). The k-mer sharing analysis of pmrCAB and its flanking regions demonstrated that sequence similarities were increased when isolates 67659 and 72554 were compared to those belonging to IC5 and IC4, respectively (Fig. 2). Furthermore, no amino acid substitutions were observed in PmrC or PmrA when isolates 67659 and 72554 were compared against isolate 67098 (IC5) and isolate 71813 (IC4), respectively. Higher sequence similarity was also observed in PmrB, with only a single substitution (Arg389Gln) identified when isolates 71813 and 72554 were compared, as well as two substitutions (Pro187Thr and Asn256Ile) in the comparison between isolates 67098 and 67659 (Fig. 1A to C). The representativeness of the included reference genomes was also explored in an additional set of isolates as well as in a larger genomic region (see Fig. S1 to S5 in the supplemental material).

FIG 1.

(A to D) Protein sequence alignment of PmrC (A), PmrA (B), and PmrB (C) and SplitsTree-based neighbor-net of a 23.6-kb genomic region encompassing pmrCAB (D) between isolates MC1 (IC7), 72554 (IC7), 71813 (IC4), 67659 (IC7), 67098 (IC5), AYE (IC1), and ACICU (IC2). Sequences belonging to isolate MC1 were used as references for sequence alignment. Amino acid differences are highlighted in colors (panels A to C).

FIG 2.

(A and B) Spatial k-mer sharing plots of a 23.6-kb genomic region encompassing pmrCAB and flanking genes of isolate 67659 against isolates MC1 (IC7, top) and 67098 (IC5, bottom) (A) and 72554 against MC1 (IC7, top) and 71813 (IC4, bottom) (B). The plots show spatial variations in the proportion of k-mers present in the genomes described on the x axis also present in the genome of the different references described on the y axis, calculated in sliding windows of 40 bases along the genome of the first isolate and for k = 19. Plots are based on k-mer counts computed with Cortex and a custom R visualization script. pmrCAB coding regions are highlighted in red, and flanking genes are indicated in green.

Spatial k-mer sharing plots of pmrCAB and flanking regions of isolates belonging to IC7 against MC1. The plots show spatial variations in the proportion of k-mers present in MC1 also observed in the genome of the different isolates described in the y axis, calculated in sliding windows of 40 bases along the genome of the MC1 and for k = 19. Plots are based on k-mer counts computed with Cortex and a custom R visualization script. pmrCAB coding regions are highlighted in red, and flanking genes are indicated in green. Download FIG S1, PDF file, 0.9 MB (927.3KB, pdf) .

Copyright © 2021 Nodari et al.

This content is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International license.

Spatial k-mer sharing plots of pmrCAB and flanking regions of isolates belonging to IC4 against 71813. The plots show spatial variations in the proportion of k-mers present in 71813 also observed in the genome of the different isolates described on the y axis, calculated in sliding windows of 40 bases along the genome of the 71813 and for k = 19. Plots are based on k-mer counts computed with Cortex and a custom R visualization script. pmrCAB coding regions are highlighted in red, and flanking genes are indicated in green. Download FIG S2, PDF file, 0.5 MB (500.1KB, pdf) .

Copyright © 2021 Nodari et al.

This content is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International license.

Spatial k-mer sharing plots of pmrCAB and flanking regions of isolates belonging to IC5 against 67098. The plots show spatial variations in the proportion of k-mers present in 67098 also observed in the genome of the different isolates described on the y axis, calculated in sliding windows of 40 bases along the genome of the 67098 and for k = 19. Plots are based on k-mer counts computed with Cortex and a custom R visualization script. pmrCAB coding regions are highlighted in red, and flanking genes are indicated in green. Download FIG S3, PDF file, 0.9 MB (938.7KB, pdf) .

Copyright © 2021 Nodari et al.

This content is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International license.

Spatial k-mer sharing plots of a 500-kb genomic region encompassing pmrCAB and flanking genes of isolate 67659 against isolates MC1 (IC7, top) and 67098 (IC5, bottom). The plots show spatial variations in the proportion of k-mers present in the genomes described on the x axis also present in the genome of the different references described on the y axis, calculated in sliding windows of 40 bases along the genome of the first isolate and for k = 19. Plots are based on k-mer counts computed with Cortex and a custom R visualization script. pmrCAB coding regions are highlighted in red. The shaded grey area highlights the genomic region depicted in Fig. 1A. Download FIG S4, PDF file, 0.1 MB (117KB, pdf) .

Copyright © 2021 Nodari et al.

This content is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International license.

Spatial k-mer sharing plots of a 500-kb genomic region encompassing pmrCAB and flanking genes of isolate 72554 against isolates MC1 (IC7, top) and 71813 (IC4, bottom). The plots show spatial variations in the proportion of k-mers present in the genomes described on the x axis also present in the genome of the different references described in the y axis, calculated in sliding windows of 40 bases along the genome of the first isolate and for k = 19. Plots are based on k-mer counts computed with Cortex and a custom R visualization script. pmrCAB coding regions are highlighted in red. The shaded grey areas highlight the genomic region depicted in Fig. 1B. Download FIG S5, PDF file, 0.08 MB (81KB, pdf) .

Copyright © 2021 Nodari et al.

This content is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International license.

The presence of regions with such high polymorphism rates suggests that horizontal transfer through recombination, rather than the accumulation of multiple point mutations over time, is involved in the variability of these specific DNA fragments. This is particularly important and more frequent in naturally transformable species, such as A. baumannii (1, 2). Based on the large number of nonsynonymous mutations observed in pmrCAB, with PmrC protein sequences presenting up to 13% divergence from what is expected for their lineage, we can infer that this operon has been transferred across clonal lineages through homologous recombination. The likely presence of recombination around the pmrCAB operon was confirmed by a SplitsTree analysis, also including reference genomes for IC1 and IC2 (Fig. 1D; phi test for recombination, P = 0.0). Considering that IC4 and IC5, together with IC7, are the most frequent lineages observed in South America (3) and were already described in the same hospital (12, 14), it comes as no surprise that horizontal gene transfer occurred among those lineages.

Using a k-mer-based analysis, it was noticed that the length of the region presenting high sequence divergence surrounding pmrCAB was similar between the two evaluated isolates and extended to at least 8 kb up- and downstream of pmrCAB (Fig. 2A and B, top). However, when using the same approach to compare those isolates to the reference genomes belonging to IC4 and IC5, which presumably acted as donors of the recombining regions, some differences were observed. While k-mer sharing proportion between isolates 67659 and 67098 was close to 1 through the whole extension of the recombining region (Fig. 2A, bottom), the similarities between isolates 72554 and 71813 were restricted to only 700 bp upstream of pmrC as well as 1,000 bp downstream of pmrB (Fig. 2B, bottom). This finding suggests that additional recombination events have taken place and that the pmrCAB allele belonging to IC4 went through some other intermediary host before making it into 72554, consistent with SplitsTree results. Boinett and colleagues (15) have previously suggested that a 700-kb genomic region that included pmrCAB had undergone homologous recombination in laboratory-induced colistin-resistant isolates. Those isolates, however, belonged to IC2, suggesting that recombining regions vary depending on their genetic background. This observation would be in agreement to the phenomenon described by Kim and Ko (13), where the authors reported that recombination could happen within pmrC, generating mosaic alleles. Such variation, however, was not observed in either of the two isolates evaluated in this study.

MGEs are often involved in horizontal gene transfer and, in A. baumannii, are frequently related to insertion sequences (ISs) and/or composite transposons (7, 16). Despite multiple copies of distinct IS elements being identified in the genomes of isolates 67659 and 72554 (data not shown), none of them was observed within or flanking the recombining region encompassing pmrCAB. In fact, the nearest IS detected was a copy of ISAba125 that was ∼14 kb upstream of pmrC in both isolates, while in the other direction the closest IS element identified (a copy of IS17) was located >120 kb downstream of pmrB, suggesting that recombination was not mediated by DNA mobilization either through an IS or a composite transposon. Phage-related structures were also observed through the genome of both isolates. However, similar to the IS elements, none of them was found flanking the recombining regions, and the closest intact phage was observed >300 kb downstream of pmrB.

Considering that IS elements are self-transposable structures (17), we investigated the presence of inverted repeats flanking the recombining region, since they indicate that MGEs were lost postrecombination. A large number of repeats was observed within and flanking the recombining region in both isolates, with an average of 44 repeats per 1,000 bp. However, sequence analysis revealed that none of them were part of or constituted an insertion site for known IS elements. Moreover, they were also found at the same position in isolates 67098 and 71813, suggesting that they were translocated from IC5 and IC4 to IC7 during recombination, respectively, rather than being responsible for the DNA mobilization. Therefore, the mechanisms involved in the mobilization of pmrCAB into IC7 isolates remain to be elucidated.

Allelic variation in the pmrCAB operon is associated with natural polymorphisms within each A. baumannii IC. In our study, we demonstrated that IC7 isolates can present additional sequence divergence as a consequence of homologous recombination of regions with variable lengths across distinct clonal lineages. Interestingly, the recombination appears not to be driven by antibiotic pressure, since it was observed in both colistin-susceptible and -resistant isolates, and a variety of clonal lineages can act as donors of the recombining region. Additionally, we observed that MGEs were not required for the transfer of pmrCAB in our isolates, since neither IS elements nor other MGEs were detected flanking the recombining region. Further studies are required to determine the mechanisms driving the mobilization of pmrCAB and to evaluate the presence of this phenomenon in other ICs as well as its frequency in the A. baumannii population.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Bacterial isolates.

A. baumannii clinical isolates 67659 and 72554 were recovered from the same tertiary hospital in the city of São Paulo, Brazil, 2 years apart (2015 and 2017, respectively). Their antimicrobial susceptibility profile was previously determined (14), and they were found to be colistin susceptible (MIC, 1 mg/liter) and resistant (MIC, >128 mg/liter), respectively. Their genomes were previously sequenced using the Illumina MiSeq platform, and cgMLST analysis revealed that the isolates had 28 allele differences and were grouped under IC7 (14). Additionally, previously described colistin-susceptible isolates belonging to IC4 (71813), IC5 (67098), and IC7 (MC1) were included as reference genomes for each IC (14, 18).

Long-read WGS using MinION platform.

Genomic DNA of isolates 67659 and 72554 was extracted using the Genomic-Tips 100/G kit and genomic DNA buffers kit (Qiagen, Hilden, Germany). Libraries were prepared using the ligation sequencing kit (SQK-LSK109), combined with a native barcoding kit (EXP-NBD104) and the rapid barcoding kit (SQK-RBK004) (Oxford Nanopore Technologies, Oxford, United Kingdom), and were loaded onto an R9.4 flow cell (Oxford Nanopore Technologies). Genomes were assembled with a hybrid approach using Unicycler version 0.4.4 (19) with default parameters.

Genome alignment and identification of the recombining region including pmrCAB.

The exact position of the pmrCAB operon was identified by aligning the pmrCAB sequence from A. baumannii ATCC 19606 (GenBank accession number NZ_CP045110.1) against the hybrid assemblies using the NUCmer tool of the MUMmer package, version 4.0.0beta2 (20), with default parameters. K-mer sharing plots were used for the robust identification of sequence homologies and recombination boundaries between lineages by visualizing spatial variation in the proportion of k-mers from one isolate (X) also present in another isolate (Y), calculated in sliding windows of 40 bases along the genome of X. In contrast to other alignment approaches, k-mer sharing plots do not require full assembly of genome Y but can be created based on short-read-derived k-mer counts. For a given region in isolate X, k-mer sharing values close to 1 indicate the likely presence of a homologous region in Y, whereas lower values indicate reduced similarity or the absence of the corresponding region from Y. The k-mer sharing plots were used to determine sequence homology patterns between different isolates around the pmrCAB operon and were created with a custom R script executed in RStudio (version 1.3.1093) (21). k-mer presence or absence was determined with Cortex (version 1.0.5.21; options “–mem_height 25,” “–mem_width 100,” and “–kmer_size 19”) (22), employing a minimum k-mer coverage threshold of 10 for the analysis of short-read data. A neighbor-net analysis of the pmrCAB region was carried out with SplitsTree (23) with default settings, based on a MUSCLE (24) multiple-sequence alignment of identified pmrCAB sequences plus 10 kb of adjacent sequence from either side of pmrCAB. The phi test implemented in SplitsTree (null hypothesis: no recombination) was used to test for recombination.

Characterization of the mobile structures involved in pmrCAB recombination.

To fully annotate the hybrid assemblies and to search for MGEs, Prokka version 1.14.5 (25) was used with default parameters. Putative IS elements and phage-related structures were further identified with the blast tools of IS-finder (https://isfinder.biotoul.fr/) and Phaster (https://phaster.ca/), respectively, using default parameters. Inverted repeats (IR) were identified using the repeat-match tool of the MUMmer package version 4.0.0beta2 (20) with a minimum repeat length of 10 bases.

Data availability.

Short and long raw reads generated for IC7 isolates 67659 and 72554, as well as the reference isolates 67098 and 71813, were submitted to the Sequence Read Archive (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/sra/) of the National Center for Biotechnology Information (NCBI) under BioProject number PRJNA632943. Genome data from isolate MC1 are available under GenBank accession number NZ_QXPV00000000.1. Additional isolates presented in the supplemental material had their short raw reads submitted to the European Nucleotide Archive (http://www.ebi.ac.uk/ena/) of EMBL European Bioinformatics Institute (EBI) under the study accession numbers PRJEB12082 and PRJEB27899.

Genome assembly statistics and inferred location of pmrCAB in A. baumannii clinical isolates included in the study. Download Table S1, PDF file, 0.02 MB (17.4KB, pdf) .

Copyright © 2021 Nodari et al.

This content is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International license.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

Computational support and infrastructure were provided by the Centre for Information and Media Technology (ZIM) at the University of Düsseldorf (Germany).

This work was supported by the Jürgen Manchot Foundation. C.S.N. received a grant from the Coordenação de Aperfeiçoamento de Pessoal de Nível Superior (CAPES-PDSE; process number 88881.187573/2018-01). K.X. was supported by the German Center for Infection Research (DZIF) and the Koeln Fortune Program/Faculty of Medicine, University of Cologne. A.C.G. received a research grant from the National Council for Science and Technological Development (CNPq-process number 312066/2019). P.G.H. was supported by the German Research Council (DFG)-FOR2251 (www.acinetobacter.de).

A.C.G. has recently received research funding and/or consultation fees from Eurofarma, InfectoPharm, MSD, Pfizer, and United Medical. Other authors have nothing to declare. This study was not financially supported by any diagnostic/pharmaceutical company.

A.D. and P.G.H. jointly supervised this work.

Contributor Information

Paul G. Higgins, Email: paul.higgins@uni-koeln.de.

Patricia A. Bradford, Antimicrobial Development Specialists, LLC

REFERENCES

- 1.Antunes LC, Visca P, Towner KJ. 2014. Acinetobacter baumannii: evolution of a global pathogen. Pathog Dis 71:292–301. doi: 10.1111/2049-632X.12125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Snitkin ES, Zelazny AM, Montero CI, Stock F, Mijares L, Murray PR, Segre JA, NISC Comparative Sequence Program . 2011. Genome-wide recombination drives diversification of epidemic strains of Acinetobacter baumannii. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 108:13758–13763. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1104404108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Müller C, Stefanik D, Wille J, Hackel M, Higgins PG, Seifert H. 2019. Molecular epidemiology of carbapenem-resistant Acinetobacter baumannii clinical isolates and identification of the novel international clone IC9: results from a worldwide surveillance study (2012–2016). 29th Eur Cong Clin Microbiol Infect Dis (ECCMID), Amsterdam, Netherlands. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Higgins PG, Prior K, Harmsen D, Seifert H. 2017. Development and evaluation of a core genome multilocus typing scheme for whole-genome sequence-based typing of Acinetobacter baumannii. PLoS One 12:e0179228. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0179228. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Zander E, Nemec A, Seifert H, Higgins PG. 2012. Association between β-lactamase-encoding bla(OXA-51) variants and DiversiLab rep-PCR-based typing of Acinetobacter baumannii isolates. J Clin Microbiol 50:1900–1904. doi: 10.1128/JCM.06462-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Furuya EY, Lowy FD. 2006. Antimicrobial-resistant bacteria in the community setting. Nat Rev Microbiol 4:36–45. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro1325. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Zhang G, Leclercq SO, Tian J, Wang C, Yahara K, Ai G, Liu S, Feng J. 2017. A new subclass of intrinsic aminoglycoside nucleotidyltransferases, ANT(3”)-II, is horizontally transferred among Acinetobacter spp. by homologous recombination. PLoS Genet 13:e1006602. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1006602. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Mussi MA, Limansky AS, Relling V, Ravasi P, Arakaki A, Actis LA, Viale AM. 2011. Horizontal gene transfer and assortative recombination within the Acinetobacter baumannii clinical population provide genetic diversity at the single carO gene, encoding a major outer membrane protein channel. J Bacteriol 193:4736–4748. doi: 10.1128/JB.01533-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hamidian M, Hancock DP, Hall RM. 2013. Horizontal transfer of an ISAba125-activated ampC gene between Acinetobacter baumannii strains leading to cephalosporin resistance. J Antimicrob Chemother 68:244–245. doi: 10.1093/jac/dks345. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Poirel L, Jayol A, Nordmann P. 2017. Polymyxins: antibacterial activity, susceptibility testing, and resistance mechanisms encoded by plasmids or chromosomes. Clin Microbiol Rev 30:557–596. doi: 10.1128/CMR.00064-16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gerson S, Lucaßen K, Wille J, Nodari CS, Stefanik D, Nowak J, Wille T, Betts JW, Roca I, Vila J, Cisneros JM, Seifert H, Higgins PG. 2020. Diversity of amino acid substitutions in PmrCAB associated with colistin resistance in clinical isolates of Acinetobacter baumannii. Int J Antimicrob Agents 55:105862. doi: 10.1016/j.ijantimicag.2019.105862. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Nodari CS, Cayô R, Streling AP, Lei F, Wille J, Almeida MS, de Paula AI, Pignatari ACC, Seifert H, Higgins PG, Gales AC. 2020. Genomic analysis of carbapenem-resistant Acinetobacter baumannii isolates belonging to major endemic clones in South America. Front Microbiol 11:584603. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2020.584603. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kim DH, Ko KS. 2015. A distinct alleles and genetic recombination of pmrCAB operon in species of Acinetobacter baumannii complex isolates. Diagn Microbiol Infect Dis 82:183–188. doi: 10.1016/j.diagmicrobio.2015.03.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Nodari CS, Higgins PG, Silva RC, Streling A, Lei F, Wille J, Seifert H, Gales A. 2019. Emergence of a pan-drug resistance phenotype among Acinetobacter baumannii isolates belonging to major epidemic clones in Brazil. 29th Eur Cong Clin Microbiol Infect Dis (ECCMID), Amsterdam, Netherlands. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Boinett CJ, Cain AK, Hawkey J, Do Hoang NT, Khanh NNT, Thanh DP, Dordel J, Campbell JI, Lan NPH, Mayho M, Langridge GC, Hadfield J, Chau NVV, Thwaites GE, Parkhill J, Thomson NR, Holt KE, Baker S. 2019. Clinical and laboratory-induced colistin-resistance mechanisms in Acinetobacter baumannii. Microb Genom 5:e000246. doi: 10.1099/mgen.0.000246. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hamidian M, Hall RM. 2014. Tn6168, a transposon carrying an ISAba1-activated ampC gene and conferring cephalosporin resistance in Acinetobacter baumannii. J Antimicrob Chemother 69:77–80. doi: 10.1093/jac/dkt312. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Vandecraen J, Chandler M, Aertsen A, Van Houdt R. 2017. The impact of insertion sequences on bacterial genome plasticity and adaptability. Crit Rev Microbiol 43:709–730. doi: 10.1080/1040841X.2017.1303661. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Cerezales M, Xanthopoulou K, Wille J, Krut O, Seifert H, Gallego L, Higgins PG. 2020. Mobile genetic elements harboring antibiotic resistance determinants in Acinetobacter baumannii isolates from Bolivia. Front Microbiol 11:919. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2020.00919. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wick RR, Judd LM, Gorrie CL, Holt KE. 2017. Unicycler: resolving bacterial genome assemblies from short and long sequencing reads. PLoS Comput Biol 13:e1005595. doi: 10.1371/journal.pcbi.1005595. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Marçais G, Delcher AL, Phillippy AM, Coston R, Salzberg SL, Zimin A. 2018. MUMmer4: a fast and versatile genome alignment system. PLoS Comput Biol 14:e1005944. doi: 10.1371/journal.pcbi.1005944. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.RStudio Team. 2020. RStudio: integrated development for R. RStudio, PBC, Boston, MA. http://www.rstudio.com/. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Iqbal Z, Caccamo M, Turner I, Flicek P, McVean G. 2012. De novo assembly and genotyping of variants using colored de Bruijn graphs. Nat Genet 44:226–232. doi: 10.1038/ng.1028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Huson DH, Bryant D. 2006. Application of phylogenetic networks in evolutionary studies. Mol Biol Evol 23:254–267. doi: 10.1093/molbev/msj030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Edgar RC. 2004. MUSCLE: a multiple sequence alignment method with reduced time and space complexity. BMC Bioinformatics 5:113. doi: 10.1186/1471-2105-5-113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Seemann T. 2014. Prokka: rapid prokaryotic genome annotation. Bioinformatics 30:2068–2069. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btu153. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Spatial k-mer sharing plots of pmrCAB and flanking regions of isolates belonging to IC7 against MC1. The plots show spatial variations in the proportion of k-mers present in MC1 also observed in the genome of the different isolates described in the y axis, calculated in sliding windows of 40 bases along the genome of the MC1 and for k = 19. Plots are based on k-mer counts computed with Cortex and a custom R visualization script. pmrCAB coding regions are highlighted in red, and flanking genes are indicated in green. Download FIG S1, PDF file, 0.9 MB (927.3KB, pdf) .

Copyright © 2021 Nodari et al.

This content is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International license.

Spatial k-mer sharing plots of pmrCAB and flanking regions of isolates belonging to IC4 against 71813. The plots show spatial variations in the proportion of k-mers present in 71813 also observed in the genome of the different isolates described on the y axis, calculated in sliding windows of 40 bases along the genome of the 71813 and for k = 19. Plots are based on k-mer counts computed with Cortex and a custom R visualization script. pmrCAB coding regions are highlighted in red, and flanking genes are indicated in green. Download FIG S2, PDF file, 0.5 MB (500.1KB, pdf) .

Copyright © 2021 Nodari et al.

This content is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International license.

Spatial k-mer sharing plots of pmrCAB and flanking regions of isolates belonging to IC5 against 67098. The plots show spatial variations in the proportion of k-mers present in 67098 also observed in the genome of the different isolates described on the y axis, calculated in sliding windows of 40 bases along the genome of the 67098 and for k = 19. Plots are based on k-mer counts computed with Cortex and a custom R visualization script. pmrCAB coding regions are highlighted in red, and flanking genes are indicated in green. Download FIG S3, PDF file, 0.9 MB (938.7KB, pdf) .

Copyright © 2021 Nodari et al.

This content is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International license.

Spatial k-mer sharing plots of a 500-kb genomic region encompassing pmrCAB and flanking genes of isolate 67659 against isolates MC1 (IC7, top) and 67098 (IC5, bottom). The plots show spatial variations in the proportion of k-mers present in the genomes described on the x axis also present in the genome of the different references described on the y axis, calculated in sliding windows of 40 bases along the genome of the first isolate and for k = 19. Plots are based on k-mer counts computed with Cortex and a custom R visualization script. pmrCAB coding regions are highlighted in red. The shaded grey area highlights the genomic region depicted in Fig. 1A. Download FIG S4, PDF file, 0.1 MB (117KB, pdf) .

Copyright © 2021 Nodari et al.

This content is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International license.

Spatial k-mer sharing plots of a 500-kb genomic region encompassing pmrCAB and flanking genes of isolate 72554 against isolates MC1 (IC7, top) and 71813 (IC4, bottom). The plots show spatial variations in the proportion of k-mers present in the genomes described on the x axis also present in the genome of the different references described in the y axis, calculated in sliding windows of 40 bases along the genome of the first isolate and for k = 19. Plots are based on k-mer counts computed with Cortex and a custom R visualization script. pmrCAB coding regions are highlighted in red. The shaded grey areas highlight the genomic region depicted in Fig. 1B. Download FIG S5, PDF file, 0.08 MB (81KB, pdf) .

Copyright © 2021 Nodari et al.

This content is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International license.

Genome assembly statistics and inferred location of pmrCAB in A. baumannii clinical isolates included in the study. Download Table S1, PDF file, 0.02 MB (17.4KB, pdf) .

Copyright © 2021 Nodari et al.

This content is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International license.

Data Availability Statement

Short and long raw reads generated for IC7 isolates 67659 and 72554, as well as the reference isolates 67098 and 71813, were submitted to the Sequence Read Archive (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/sra/) of the National Center for Biotechnology Information (NCBI) under BioProject number PRJNA632943. Genome data from isolate MC1 are available under GenBank accession number NZ_QXPV00000000.1. Additional isolates presented in the supplemental material had their short raw reads submitted to the European Nucleotide Archive (http://www.ebi.ac.uk/ena/) of EMBL European Bioinformatics Institute (EBI) under the study accession numbers PRJEB12082 and PRJEB27899.

Genome assembly statistics and inferred location of pmrCAB in A. baumannii clinical isolates included in the study. Download Table S1, PDF file, 0.02 MB (17.4KB, pdf) .

Copyright © 2021 Nodari et al.

This content is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International license.