Abstract

Study Objectives:

Patients with congestive heart failure (CHF) frequently exhibit an elevated ratio of minute ventilation over CO2 output (VE/VCO2 slope) while undergoing exercise tests. One of the factors contributing to this elevated slope is an increased chemosensitivity to CO2 in that this slope significantly correlates with the slope of the ventilatory response to CO2 rebreathing at rest. A previous study in patients with CHF and central sleep apnea showed that the highest VE/VCO2 slope during exercise was associated with the most severe central sleep apnea. In the current study, we tested the hypothesis that in patients with CHF and obstructive sleep apnea (OSA), the highest VE/VCO2 slope is also associated with the most severe OSA. If the hypothesis is correct, then it implies that in CHF, augmented instability in the negative feedback system controlling breathing predisposes to both OSA and central sleep apnea.

Methods:

This preliminary study involved 70 patients with stable CHF and a spectrum of OSA severity who underwent full-night polysomnography, echocardiography, and cardiopulmonary exercise testing. Peak oxygen consumption and the VE/VCO2 slope were calculated.

Results:

There was significant positive correlation between the apnea-hypopnea index and the VE/VCO2 slope (r = .359; P = .002). In the regression model, involving the relevant variables of age, body mass index, sex, VE/VCO2 slope, peak oxygen consumption, and left ventricular ejection fraction, the apnea-hypopnea index retained significance with VE/VCO2.

Conclusions:

In patients with CHF, the VE/VCO2 slope obtained during exercise correlates significantly to the severity of OSA, suggesting that an elevated CO2 response should increase suspicion for the presence of severe OSA, a treatable disorder that is potentially associated with excess mortality.

Clinical Trial Registration:

Registry: ClinicalTrials.gov; Name: Comparison Between Exercise Training and CPAP Treatment for Patients With Heart Failure and Sleep Apnea; URL: https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/record/NCT01538069; Identifier: NCT01538069.

Citation:

Bittencourt L, Javaheri S, Servantes DM, Pelissari Kravchychyn AC, Almeida DR, Tufik S. In patients with heart failure, enhanced ventilatory response to exercise is associated with severe obstructive sleep apnea. J Clin Sleep Med. 2021;17(X):1875–1880.

Keywords: obstructive sleep apnea, heart failure, enhanced ventilatory response, exercise

BRIEF SUMMARY

Current Knowledge/Study Rationale: In CHF, augmented instability in the negative feedback system controlling breathing predisposes to both OSA and central sleep apnea.

Study Impact: Elevated CO2 response during exercise should increase suspicion for the presence of severe OSA, a treatable disorder that is potentially associated with excess mortality.

INTRODUCTION

It is well known that some patients with heart failure and reduced ejection fraction (HFrEF) experience moderate to severe obstructive sleep apnea (OSA).1–3 The disorder is characterized by recurrent episodes of complete or partial upper airway occlusion (apnea or hypopnea, respectively; hitherto referred to as OSA). Repeated episodes of hypoxia-reoxygenation, large negative swings in intrathoracic/juxta-cardiac pressure, and arousals adversely affect the already impaired left ventricular function.3–5 With continued exposure over time, OSA leads to increased sympathetic activity,6 excess hospital readmissions,7,8 and mortality.7,9–11 Treatment of severe OSA with continuous positive airway pressure devices reduces myocardial sympathetic activity,12 improves myocardial energy,12 and increases the left ventricular ejection fraction (LVEF).13 Further, observational studies have shown that treatment of OSA with positive airway pressure devices decreases hospital readmission,7,14,15 health care costs,7 and mortality.7,10,11 Therefore, the diagnosis and treatment of OSA, particularly when severe, could have important clinical implications.

The underlying mechanisms of OSA are complex and multifactorial. There are multiple phenotypes.16–18 In addition to anatomical upper airway pharyngeal mechanisms, there are also nonanatomical causes of OSA.16–18 Among the latter is an exaggerated ventilatory control contributing to pharyngeal collapse.5,16–18 The most important component of the unstable ventilatory control system is increased chemosensitivity of the respiratory system to changes in partial pressures of CO2 and O2, which increases the controller gain.5,16–18 In this sense, during sleep, augmented chemosensitivity to CO2 promotes breathing instability because of an overshoot in ventilation in response to a small reduction in breathing. The inappropriate excess ventilation causes hypocapnia with a reduction in the inspiratory drive, promoting pharyngeal collapse. In addition, a large negative inspiratory pharyngeal pressure associated with ventilatory overshoot can suction the upper airway in, causing closure.

Patients with HFrEF exhibit both augmented hypercapnic and hypoxic ventilatory responses,19–22 and these ventilatory responses obtained at rest significantly and closely correlate with the ventilatory response to exercise, the slope of the ratio of minute ventilation over CO2 output (VE/VCO2 ratio).23–25 It must be emphasized, however, that multiple factors contribute to ventilatory efficiency during exercise, including ventilation perfusion mismatch and a number of components of ventilatory control (central chemoreceptors, peripheral chemoreceptors, or skeletal muscle receptors).

Using a similar methodology, Arzt and colleagues23 showed that in patients with HFrEF, ventilatory response to exercise correlated significantly with central sleep apnea. The current study is the first to show that in patients with HFrEF and OSA, the slope of VE/VCO2 also correlates with the apnea-hypopnea index (AHI). However, the most important finding is that the augmented response is specific to those with severe OSA, a common treatable disorder in heart failure (HF) that has been shown to contribute to the morbidity and mortality of these patients. The findings of this preliminary study have important diagnostic and therapeutic implications.

METHODS

Study population

The Joint Research Ethics Board of the Universidade Federal de São Paulo approved this protocol (CEP 1226/11), and the protocol is registered with ClinicalTrials.gov (ClinicalTrials.gov identifier: NCT 01538069). Informed consent was obtained from all patients.

We prospectively enrolled consecutive patients who were followed regularly at a specialist HF medical center of the Federal University of São Paulo, Brazil. All patients were evaluated by the same medical staff, and the diagnosis was based on the presence of symptoms and signs of HF in combination with objective evidence of left ventricular systolic dysfunction (ejection fraction < 40%).

Aside from a history of congestive heart failure, other inclusion criteria were as follows: aged 30–70 years, New York Heart Association Class II–III, ejection fraction < 40%, and clinically stable for 3 months on optimized medical therapy. The study criterion for OSA was AHI ≥ 5 events/h with symptoms or AHI ≥ 15 events/h regardless of the presence of symptoms. The exclusion criteria were as follows: New York Heart Association Class IV, history of acute myocardial infarction, cardiac surgery, percutaneous coronary intervention, automatic implantable cardiac defibrillator or cardiac resynchronization therapy within the past 4 months, unstable angina, complex or symptomatic ventricular arrhythmias, mitral or aortic stenosis, hypertrophic cardiomyopathy, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, musculoskeletal disorders, or psychiatric diseases that prevented the patient from understanding and following the intervention procedure.

Polysomnography

Full-night attended polysomnography was performed with the supervision of trained professionals using a digital system (EMBLA S7000, Embla Systems, Inc, Broomfield, CO) in the sleep laboratory during the patient’s habitual sleep time. We monitored electroencephalogram (3 channels), electrooculogram (left and right eye), electromyogram (submental and anterior tibialis muscles), electrocardiogram, oronasal airflow (pressure transducer and a thermistor), thoracoabdominal excursions (inductance plethysmography), snoring, body position sensor, oxyhemoglobin saturation (pulse oximetry), and pulse rate. Polysomnograms were scored blindly by an experienced sleep technician and reviewed by a sleep medicine physician. Apneas were defined as a ≥ 90% reduction in airflow lasting ≥ 10 seconds. Apneas were central in the absence of thoracoabdominal excursions. Hypopneas were defined as a ≥ 30% reduction airflow lasting ≥ 10 seconds, associated with a ≥ 4% desaturation.26 Hypopneas were classified as obstructive if there was snoring, airflow limitation on the nasal pressure tracing, or out-of-phase thoracoabdominal motion.26

Cardiopulmonary exercise testing

All patients underwent a symptom-limited treadmill test with respiratory gas exchange analysis, according to the Weber protocol.27 The protocol was 3.5 mph/hour every 2 minutes. All tests were performed under the supervision of an experienced sports physician. The gas exchange data were collected in a breath-by-breath manner and averaged into 30-second time periods (Cosmed, Chicago, IL). Blood pressure was determined using a mercury sphygmomanometer (Oxygel, São Paulo, Brazil) at rest and at the end of each stage. The participants were encouraged to exercise until exhaustion. The self-perceived level of exertion (15-point Borg scale)28 was assessed at peak effort. The peak oxygen consumption (peak VO2) was calculated as the highest 30-second time. VO2 anaerobic threshold was measured using the V-slope method.29 The slope relating ventilation to carbon dioxide production (the VE/VCO2 slope) was calculated by linear regression, excluding the nonlinear part of the data after the onset of ventilatory compensation for metabolic acidosis.

Echocardiographic assessment

Echocardiography was performed using standard techniques. M‐mode and 2‐dimensional images were obtained from the standard parasternal and apical windows. The biplane Simpson’s method was used to measure left ventricular end‐diastolic and end‐systolic volumes from which the LVEF was derived.

Statistical analysis

We used an analysis of variance with a Bonferroni correction factor for multiple comparisons. Multivariate linear regression analyses were used to determine the association of AHI (dependent variable) with age, body mass index (BMI), sex, VE/VCO2 slope, VO2, and LVEF. Mean ± standard deviation and 95% confidence intervals are reported. Statistical analyses were performed using SPSS 19.0 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL), and a P value < .05 was considered statistically significant.

RESULTS

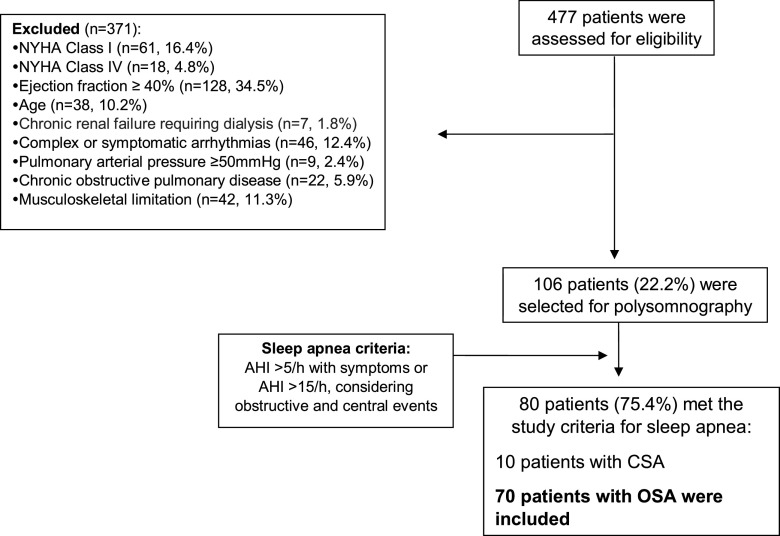

Figure 1 shows the flow chart of the patients. Seventy patients met the study criteria. There were 43 men and 27 women, aged 54 ± 9 years (mean ± 1 standard deviation), with a BMI of 30 ± 3 kg/m2. The LVEF varied from 16%–39% (mean ± standard deviation, 31% ± 6%). All patients were on a beta-blocker, and most were obese (Table 1). Several patients had Chagas disease, an infectious disease common in South America, as the cause of HF. One patient with breast cancer had chemotherapy with liposomal doxorubicin-induced HF and was clinically stable for 6 months (Table 1).

Figure 1. The selection and inclusion of the patients.

AHI = apnea-hypopnea index, CSA = central sleep apnea, NYHA = New York Heart Association, OSA = obstructive sleep apnea.

Table 1.

Baseline clinical data of 70 patients with HF according to severity of OSA.

| Total | Mild OSA (n = 22) | Moderate OSA (n = 23) | Severe OSA (n = 25) | P | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age, y | 54 ± 9 | 51 ± 8 | 54 ± 10 | 57 ± 9 | .134 |

| BMI, kg/m2 | 30 ± 3 | 30 ± 3 | 31 ± 4 | 30 ± 3 | .393 |

| Ejection fraction, % | 31 ± 6 | 32 ± 6 | 31 ± 5 | 30 ± 6 | .455 |

| Heart failure etiology, n/% | |||||

| Ischemic | 16/23 | 3/14 | 5/22 | 8/32 | .376 |

| Chagas disease | 14/20 | 5/22 | 5/22 | 4/16 | |

| Alcoholic | 6/9 | 3/14 | 1/4 | 2/8 | |

| Idiopathic | 10/14 | 5/22 | 4/17 | 1/4 | |

| Hypertensive | 23/33 | 6/27 | 7/30 | 10/40 | |

| Chemotherapy | 1/1 | 0/0 | 1/4 | 0/0 | |

| NYHA class, n/% | |||||

| II | 45/64 | 16/73 | 17/74 | 12/48 | .456 |

| III, IV | 25/36 | 6/7 | 6/6 | 13/52 | |

| Medications, n/% | |||||

| Beta-blocker | 70/100 | 22/100 | 23/100 | 25/100 | .567 |

| ACEI | 64/91 | 21/95 | 22/95 | 21/84 | |

| Aldosterone antagonist | 70/100 | 22/100 | 23/100 | 25/100 | |

| Diuretics | 70/100 | 22/100 | 23/100 | 25/100 | |

| Calcium-channel blockers | 3/4 | 0/0 | 0/0 | 3/12 | |

| Angiotensin receptor blocker | 10/14 | 1/4 | 2/9 | 7/28 | |

| Digitalis | 13/18 | 5/22 | 3/13 | 5/20 | |

| Glycemic control | 26/37 | 7/32 | 8/35 | 11/44 | |

| Lipid-lowering therapy | 33/47 | 11/50 | 9/26 | 13/52 | |

| Platelet antiaggregant | 28/40 | 8/36 | 9/39 | 11/44 | |

| Oral anticoagulant | 10/14 | 2/9 | 4/17 | 4/16 | |

| Smoking | 6/8% | 1/4% | 3/13% | 2/8% | |

| Diabetes | 27/38% | 7/32% | 9/39% | 11/44% | .341 |

| Dyslipidemia | 37/52% | 12/54% | 11/48% | 14/56% | |

| Hypertension | 58/83% | 17/77% | 17/74% | 24/96% |

An analysis of variance and a chi-square test were used. ACEI = angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitor, BMI = body mass index, HF = heart failure, NYHA = New York Heart Association, OSA = obstructive sleep apnea.

There were 25 patients with severe OSA (AHI ≥ 30 events/h; mean AHI, 48 ± 14 events/h), 23 with moderate OSA (AHI ≥ 15 events/h but < 30 events/h; mean AHI, 22 ± 5 events/h), and 22 with mild OSA (defined as AHI ≥ 5 events/h but < 15 events/h; mean AHI, 11 ± 2 events/h). Among the 3 groups, there were no significant differences in sex, age, BMI, LVEF, heart failure etiology, New York Heart Association class, or medications (Table 1).

Polysomnographic parameters are in Table 2. AHI varied from 7–82 events/h. As expected, some of the polysomnographic parameters were worse in the group with the most severe OSA, particularly in comparison with the group with mild OSA (Table 2). In comparison, stage N1 sleep/total sleep time and arousal index were significantly higher, rapid eye movement sleep/total sleep time were significantly lower, and as expected desaturation was the most severe.

Table 2.

Polysomnographic parameters of 70 patients with HF according to the severity of OSA.

| Total | Mild OSA (n = 22) | Moderate OSA (n = 23) | Severe OSA (n = 25) | P | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| TST (min) | 326 ± 69 | 324 ± 69 | 353 ± 7 | 301 ± 6* | .03 |

| Sleep efficiency (%) | 74 ± 1 | 74 ± 1 | 79 ± 1 | 69 ± 1 | .068 |

| N1 sleep, % TST | 13 ± 2 | 10 ± 7 | 10 ± 8 | 19 ± 1*,† | .009 |

| N2 sleep, % TST | 51 ± 1 | 49 ± 1 | 55 ± 1 | 49 ± 1 | .189 |

| N3 sleep, % TST | 17 ± 7 | 19 ± 7 | 16 ± 7 | 17 ± 7 | .210 |

| REM sleep, % TST | 18 ± 6 | 21 ± 6 | 19 ± 7 | 16 ± 6† | .013 |

| AHI, events/h | 28 ± 2 | 11 ± 2 | 22 ± 5‡ | 48 ± 1*,† | .000 |

| OAI, events/h | 9 ± 1 | 2 ± 3 | 4 ± 5 | 19 ± 2*,† | .000 |

| CAI, events/h | 3 ± 5 | 1 ± 1 | 1 ± 3 | 7 ± 7*,† | .000 |

| OH, events/h | 9 ± 1 | 2 ± 2 | 3 ± 4 | 17 ± 1*,† | .000 |

| CH, events/h | 3 ± 4 | 1 ± 1 | 2 ± 3 | 8 ± 7*,† | .000 |

| Arl, events/h | 19 ± 1 | 13 ± 5 | 18 ± 9 | 26 ± 12*,† | .012 |

| Supine awake SaO2 (%) | 94 ± 2 | 95 ± 1 | 94 ± 2 | 94 ± 2 | .091 |

| Lowest SaO2 (%) | 82 ± 5 | 84 ± 4 | 81 ± 5 | 81 ± 5† | .031 |

| SaO2 < 90%, % TST | 12 ± 2 | 4 ± 7 | 16 ± 2 | 16 ± 2 | .05 |

Analysis of variance/Bonferroni post hoc: *P < .05 (severe vs moderate), †P < .05 (severe vs mild), ‡P < .05 (moderate vs mild). AHI = apnea-hypopnea index, Arl = arousal index, CAI = central apnea index, CH = central hypopnea, HF = heart failure, OAI = obstructive apnea index, OH = obstructive hypopnea, OSA = obstructive sleep apnea, REM = rapid eye movement sleep, SaO2 = arterial oxygen saturation, TST = total sleep time.

The VE/VCO2 slope varied from 26 to 62 L/mL. The slope was significantly higher in patients with severe OSA compared to those with moderate OSA (40 ± 8 vs 34 ± 4; P = .003) or mild OSA (40 ± 8 vs 33 ± 5; P = .001; Table 3). There were no significant differences between the slopes of patients with moderate vs mild OSA (34 ± 4 vs 33 ± 5; P = .54)

Table 3.

Cardiopulmonary exercise tests of 70 patients with HF according to the severity of OSA.

| Total | Mild OSA (n = 22) | Moderate OSA (n = 23) | Severe OSA (n = 25) | P | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Test duration (min) | 7 ± 2 | 7.0 ± 2 | 7.5 ± 2 | 7.4 ± 3 | .783 |

| Peak VO2 (mL/kg/min) | 15 ± 2 | 14.8 ± 2 | 15.6 ± 2 | 14.7 ± 3 | .443 |

| VE/VCO2 slope (L/mL) | 36 ± 6 | 33.9 ± 5 | 34.3 ± 4 | 40.0 ± 8*,† | .00 |

Analysis of variance/Bonferroni post hoc: *P < .05 (severe vs mild); †P < .05 (severe vs moderate). HF = heart failure, OSA = obstructive sleep apnea, Peak VO2 = peak oxygen saturation, VE/VCO2, ratio of minute ventilation over CO2 input.

There was a positive correlation between the AHI and the VE/VCO2 slope (n = 70; r = .359; P = .002) and age (r = .285; P = .017). There were no significant correlations between the AHI and peak VO2 (r = –.099; P = .41), LVEF (r = –.193; P = .10), or BMI (r = .036; P = .76). Age did not significantly correlate with the VE/VCO2 slope (r = .134; P = .27).

According to the multivariate regression analysis, with the AHI as the dependent variable and sex, age, BMI, VE/VCO2 slope, and LVEF as independent variables, the AHI significantly and positively correlated only with the VE/VCO2 slope (r = .34; P = .003) and age (r = .32; P = .006). The correlation of the log AHI with the VE/VCO2 slope was similar to the AHI correlation (r = .36; P = .002).

DISCUSSION

This is the first study to show that in patients with HFrEF, the VE/VCO2 slope is associated with severe OSA. When patients with HF perform exercise, an augmented ventilatory response could alert them to the presence of comorbid severe OSA, which if unrecognized could contribute to excess hospital readmissions7,8 and mortality.7,9–11 Notably, an increased VE/VCO2 slope has been shown to be associated with the mortality of patients with HF.24,30 We must emphasize that BMI, LVEF, and other parameters of exercise, specifically peak VO2, were not associated with severe OSA.

Our data showing the link between increased ventilatory response during exercise to severe OSA in patients with HF are consistent with those in patients without known HF in whom augmented ventilatory control is a predictor of severe OSA.21 Furthermore, similar to our results in OSA and HFrEF, in patients with central sleep apnea and HFrEF, an elevated ventilatory response to CO2 during exercise23 and at rest19 is associated with severe central sleep apnea. Collectively, these data signify the critical role of increased chemosensitivity in the pathogenesis of severe sleep apnea, both OSA and central sleep apnea, and both with and without HF.

Given the epidemic of HF, it is costly to perform sleep studies in all comers. The cardiopulmonary exercise test is routinely performed in patients with HF. The results of our study suggest that a high VE/VCO2 slope should increase the suspicion for the presence of severe OSA and lead to a sleep study. This finding is clinically important because many patients with HF who experience sleep apnea do not report daytime sleepiness and therefore are not tested for sleep apnea.3,6,9,10 Meanwhile, severe OSA has been associated with poor survival and cardiovascular mortality in both the general population3–5 and in those with cardiovascular disorders3,7,10 including HFrEF.9–11 In patients with HFrEF, the treatment of severe OSA using continuous positive airway pressure devices improves the LVEF,13 and observational studies suggest that continuous positive airway pressure treatment improves survival7,11 and decreases hospital readmission and health-related costs.7 We acknowledge, however, that randomized controlled trials in this population are missing.

CONCLUSIONS

A subset of patients with HFrEF experience severe OSA, which has been shown to be associated with low LVEF, excess hospital readmission, and mortality. We report that in patients with HFrEF, an elevated ratio of CO2 output over ventilation is associated with severe OSA, similar to the findings in the general population. An elevated CO2 response during exercise should increase the suspicion for the presence of comorbid severe OSA, a treatable disorder.

A limitation of our study is that the cohort included a number of patients with Chagas disease. The disorder is rarely reported as the cause of HF in the United States but is common in South America. However, the study enrolled consecutive eligible patients, and Chagas disease being a common disorder, we had no reason to exclude them. Meanwhile, only 14 out of 70 patients had Chagas disease and were equally distributed among the 3 OSA groups; all had stable HF and maximal medical tolerable therapy, with no significant differences between them and the rest of the patients (Table 1).

DISCLOSURE STATEMENT

This study was supported by grants from the Associacao Fundo de Incentivo a Pesquisa, Sao Paulo Research Foundation (FAPESP) [Grant no. 11/51492-5 to D.M.S.]. S. T. and L. B. are National Council for Scientific and Technological Development (CNPq) fellowship recipients. The authors report no conflicts of interest.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

Author contributions: L.B. was responsible for the study concept and design, study supervision, study participation, drafting of the manuscript, analysis and interpretation of data, and critical revision of the manuscript for intellectual content. S.J. was responsible for the proposed hypothesis of the investigation, interpretation of the data, and writing of the manuscript. D.M.S. was responsible for the study concept and design, study participation, drafting of the manuscript, analysis and interpretation of data, and critical revision of the manuscript for intellectual content. A.C.P.K. and D.R.A. was responsible for the study concept and design and critical revision of the manuscript for intellectual content. S.T. was responsible for the study concept and design, study supervision, financial support, and critical revision of the manuscript for intellectual content.

ABBREVIATIONS

- AHI

apnea-hypopnea index

- BMI

body mass index

- CHF

congestive heart failure

- HF

heart failure

- HFrEF

heart failure and reduced ejection fraction

- LVEF

left ventricular ejection fraction

- OSA

obstructive sleep apnea

- peak VO2

peak oxygen consumption

- VE/VCO2

ratio of minute ventilation over CO2 output

REFERENCES

- 1. Javaheri S , Parker TJ , Liming JD , et al . Sleep apnea in 81 ambulatory male patients with stable heart failure. Types and their prevalences, consequences, and presentations . Circulation. 1998. ; 97 ( 21 ): 2154 – 2159 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Sin DD , Fitzgerald F , Parker JD , Newton G , Floras JS , Bradley TD . Risk factors for central and obstructive sleep apnea in 450 men and women with congestive heart failure . Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 1999. ; 160 ( 4 ): 1101 – 1106 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Javaheri S , Barbe F , Campos-Rodriguez F , et al . Sleep apnea: types, mechanisms, and clinical cardiovascular consequences . J Am Coll Cardiol. 2017. ; 69 ( 7 ): 841 – 858 . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Drager LF , Polotsky VY , O’Donnell CP , Cravo SL , Lorenzi-Filho G , Machado BH . Translational approaches to understanding metabolic dysfunction and cardiovascular consequences of obstructive sleep apnea . Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2015. ; 309 ( 7 ): H1101 – H1111 . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Dempsey JA , Veasey SC , Morgan BJ , O’Donnell CP . Pathophysiology of sleep apnea . Physiol Rev. 2010. ; 90 ( 1 ): 47 – 112 . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Usui K , Bradley TD , Spaak J , et al . Inhibition of awake sympathetic nerve activity of heart failure patients with obstructive sleep apnea by nocturnal continuous positive airway pressure . J Am Coll Cardiol. 2005. ; 45 ( 12 ): 2008 – 2011 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Javaheri S , Caref EB , Chen E , Tong KB , Abraham WT . Sleep apnea testing and outcomes in a large cohort of Medicare beneficiaries with newly diagnosed heart failure . Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2011. ; 183 ( 4 ): 539 – 546 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Khayat R , Abraham W , Patt B , et al . Central sleep apnea is a predictor of cardiac readmission in hospitalized patients with systolic heart failure . J Card Fail. 2012. ; 18 ( 7 ): 534 – 540 . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Khayat R , Jarjoura D , Porter K , et al . Sleep disordered breathing and post-discharge mortality in patients with acute heart failure . Eur Heart J. 2015. ; 36 ( 23 ): 1463 – 1469 . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Wang H , Parker JD , Newton GE , et al . Influence of obstructive sleep apnea on mortality in patients with heart failure . J Am Coll Cardiol. 2007. ; 49 ( 15 ): 1625 – 1631 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Kasai T , Narui K , Dohi T , et al . Prognosis of patients with heart failure and obstructive sleep apnea treated with continuous positive airway pressure . Chest. 2008. ; 133 ( 3 ): 690 – 696 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Hall AB , Ziadi MC , Leech JA , et al . Effects of short-term continuous positive airway pressure on myocardial sympathetic nerve function and energetics in patients with heart failure and obstructive sleep apnea: a randomized study . Circulation. 2014. ; 130 ( 11 ): 892 – 901 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Kaneko Y , Floras JS , Usui K , et al . Cardiovascular effects of continuous positive airway pressure in patients with heart failure and obstructive sleep apnea . N Engl J Med. 2003. ; 348 ( 13 ): 1233 – 1241 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Kauta SR , Keenan BT , Goldberg L , Schwab RJ . Diagnosis and treatment of sleep disordered breathing in hospitalized cardiac patients: a reduction in 30-day hospital readmission rates . J Clin Sleep Med. 2014. ; 10 ( 10 ): 1051 – 1059 . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Sharma S , Mather P , Gupta A , et al . Effect of early intervention with positive airway pressure therapy for sleep disordered breathing on six-month readmission rates in hospitalized patients with heart failure . Am J Cardiol. 2016. ; 117 ( 6 ): 940 – 945 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Eckert DJ , White DP , Jordan AS , Malhotra A , Wellman A . Defining phenotypic causes of obstructive sleep apnea. Identification of novel therapeutic targets . Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2013. ; 188 ( 8 ): 996 – 1004 . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Jordan AS , McSharry DG , Malhotra A . Adult obstructive sleep apnoea . Lancet. 2014. ; 383 ( 9918 ): 736 – 747 . PubMed [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Javaheri S , Brown L , Abraham W , Khayat R . Apneas of heart failure and phenotype-guided treatments . Part one: OSA. Chest. 2020. ; 157 ( 2 ): 394 – 492 . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Javaheri S . A mechanism of central sleep apnea in patients with heart failure . N Engl J Med. 1999. ; 341 ( 13 ): 949 – 954 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Solin P , Roebuck T , Johns DP , Walters EH , Naughton MT . Peripheral and central ventilatory responses in central sleep apnea with and without congestive heart failure . Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2000. ; 162 ( 6 ): 2194 – 2200 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Younes M . Role of respiratory control mechanisms in the pathogenesis of obstructive sleep disorders . J Appl Physiol 1985 . 2008. ; 105 ( 5 ): 1389 – 1405 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Martin BJ , Weil JV , Sparks KE , McCullough RE , Grover RF . Exercise ventilation correlates positively with ventilatory chemoresponsiveness . J Appl Physiol. 1978. ; 45 ( 4 ): 557 – 564 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Arzt M , Harth M , Luchner A , et al . Enhanced ventilatory response exercise patients with chronic heart failure and central sleep apnea . Circulation. 2003. ; 107 ( 15 ): 1998 – 2003 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Ponikowski P , Francis DP , Piepoli MF , et al . Enhanced ventilatory response to exercise in patients with chronic heart failure and preserved exercise tolerance: marker of abnormal cardiorespiratory reflex control and predictor of poor prognosis . Circulation. 2001. ; 103 ( 7 ): 967 – 972 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Chua TP , Clark AL , Amadi AA , Coats AJ . Relation between chemosensitivity and the ventilatory response to exercise in chronic heart failure . J Am Coll Cardiol. 1996. ; 27 ( 3 ): 650 – 657 . PubMed [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Berry RB , Brooks R , Gamaldo CE , et al. ; American Academy of Sleep Medicine . The AASM Manual for the Scoring of Sleep and Associated Events: Rules, Terminology and Technical Specifications. Version 2.3. Darien, IL: : American Academy of Sleep Medicine; ; 2016. . [Google Scholar]

- 27. Weber KT , Janicki JS , McElroy PA , Reddy HK . Concepts and applications of cardiopulmonary exercise testing . Chest. 1988. ; 93 ( 4 ): 843 – 847 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Borg GA . Psychophysical bases of perceived exertion . Med Sci Sports Exerc. 1982. ; 14 ( 5 ): 377 – 381 . [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Beaver WL , Wasserman K , Whipp BJ . A new method for detecting anaerobic threshold by gas exchange . J Appl Physiol 1985 . 1986. ; 60 ( 6 ): 2020 – 2027 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Ingle L . Prognostic value and diagnostic potential of cardiopulmonary exercise testing in patients with chronic heart failure . Eur J Heart Fail. 2008. ; 10 ( 2 ): 112 – 118 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]