Abstract

BACKGROUND/OBJECTIVES

Considering the high number of deaths from coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) in Latin American countries, together with multiple factors that increase the prevalence of vitamin D deficiency, we aimed to determine 25-hydroxyvitamin D (25[OH]D) levels and its association with mortality in patients with critical COVID-19.

SUBJECTS/METHODS

This was a prospective observational study including adult patients with critical COVID-19. Data, including clinical characteristics and 25(OH)D levels measured at the time of intensive care unit admission, were collected. All patients were followed until hospital discharge or in-hospital death. The patients were divided into those surviving and deceased patient groups, and univariate and multivariate logistic regression analyses were performed to determine independent predictors of in hospital mortality.

RESULTS

The entire cohort comprised 94 patients with critical COVID-19 (males, 59.6%; median age, 61.5 years). The median 25(OH)D level was 12.7 ng/mL, and 15 (16%) and 79 (84%) patients had vitamin D insufficiency and vitamin D deficiency, respectively. The median serum 25(OH)D level was significantly lower in deceased patients compared with surviving (12.1 vs. 18.7 ng/mL, P < 0.001). Vitamin D deficiency was present in 100% of the deceased patients. Multivariate logistic regression analysis revealed that age, body mass index, other risk factors, and 25(OH)D level were independent predictors of mortality.

CONCLUSIONS

Vitamin D deficiency was present in 84% of critical COVID-19 patients. Serum 25(OH)D was independently associated with mortality in critical patients with COVID-19.

Keywords: Vitamin D, COVID-19, SARS-CoV-2 virus, mortality, critical illness

INTRODUCTION

The coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic, which has led to 2,610,925 deaths globally since its emergence at the end of 2019, has a reported mortality of 2.2% [1]. As of March 2021, COVID-19 has been responsible for 213,020 deaths, with a mortality of 9.9%, in Mexico, which is among the top 10 countries with high COVID-19 mortality rates [1,2]. On the other hand, COVID-19 mortality is between 6% and 10% in patients with cardiovascular and chronic respiratory tract diseases, diabetes mellitus (DM), and hypertension [3].

Serum vitamin D level has been identified as a poor prognostic factor in COVID-19. An observational study from Europe which analyzed the vitamin D status in older adults with COVID-19 reported that countries with greater exposure to sunlight such as Spain and Italy, which have the highest rates of COVID-19 and mortality, had high rates of vitamin D deficiency [4]. In contrast, high-latitude countries of Norway, Finland, and Sweden, which receive less ultraviolet-B sunlight than southern Europe, had low rates of vitamin D deficiency and, specifically in Norway and Finland, lower rates of COVID-19 and associated mortality. The study also showed a significant correlation between 25-hydroxyvitamin D (25[OH]D) and mortality rate (P = 0.046) [4]. This counterintuitive finding, i.e., the higher vitamin D deficiency in European countries with greater sun exposure compared with the lower vitamin D deficiency in high-latitude European countries with less sun exposure, may be explained by the consistently higher consumption of fatty fish, vitamin D fortification of food, and vitamin D supplementation in countries with low sun exposure [5]. In the Americas, high rates (up to 77%) of vitamin D deficiency have been reported [6], and, specifically in Mexico, as a country, the prevalence of vitamin D low levels has been reported to be 30%, being higher in Mexico City (43.1%) [7].

It is known that vitamin D is involved in innate and adaptive immunity; one mechanism is by boosting the defenses of the mucous membranes and attenuating excessive inflammation, which may explain the role of vitamin D in acute infections [8]. Vitamin D induces the gene encoding the antimicrobial peptide LL-37 [9]; this peptide has antiviral capacity against a number of viruses, including influenza-virus [10].

Several studies reported that between 59% and 74% of patients hospitalized with COVID-19 had vitamin D deficiency and that the rate of vitamin D deficiency was higher in those with torpid evolution [11,12,13]. Considering the high mortality rates of COVID-19 in Latin American countries, together with multiple factors that increase the prevalence of vitamin D deficiency, it is critical to determine the role of vitamin D deficiency in the prognosis of patients with COVID-19. Therefore, the present study aimed to determine the vitamin D status and evaluate the association of 25(OH)D levels with mortality in patients with critical COVID-19.

SUBJECTS AND METHODS

Study design

This prospective, observational study included adult patients treated for critical COVID-19 between May 1, 2020 to November 30, 2020 in Hospital #48 of the Instituto Mexicano del Seguro Social in Mexico City. Critical COVID-19 was defined as the presence of respiratory failure and the need for mechanical ventilation, shock, or other organ failure requiring admission to intensive care unit (ICU). Patients without available 25(OH)D or albumin values and those with a clinical presentation compatible with COVID-19 who did not have a positive real-time polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR)-based test for severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) were excluded from the study. All patients were followed until hospital discharge or in-hospital death.

For all patients, data on the following clinical characteristics and risk factors were obtained from the clinical records: body mass index (BMI), obesity (BMI ≥ 30), hypertension, diabetes mellitus type 2 (DM2), chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, chronic kidney disease, congestive heart failure, peripheral venous insufficiency, and smoking.

In all patients, blood samples were collected at the time of ICU admission to measure 25(OH)D and albumin levels. Serum albumin levels < 3.5 g/dL were defined as hypoalbuminemia. Serum 25(OH)D levels of < 20 and 20–29.99 ng/mL were defined as vitamin D deficiency and vitamin D insufficiency, respectively, whereas a serum 25(OH)D level > 30 ng/mL was defined as normal vitamin D status [14].

Laboratory assays

In the present study, 25(OH)D levels were determined using chemiluminescence on the Architect i1000 platform (Abbott Diagnostics, Abbott Park, IL, USA) and albumin levels were determined by colorimetric enzymatic methods (Dimension Integrated Chemistry System, Erlangen, Germany) in the clinical laboratory of the Hospital Infantil de México Federico Gómez.

The presence of SARS-CoV2 was determined by RT-PCR in accordance with the standardized guidelines for Laboratory Epidemiological Surveillance of COVID-19 (Supplementary Material 1) (Dirección General de Epidemiología, 2020).

Statistical analysis

For quantitative variables, the Kolmogorov-Smirnov test was performed to evaluate the normality of the distribution of data, and data with non-normal distribution were presented as medians with 95% confidence intervals (CIs). Qualitative variables were presented as proportions and frequencies. The patients were divided into surviving and deceased patient groups. Comparisons between the 2 groups were performed using the Mann-Whitney U test for quantitative variables and the χ2 or Fisher's exact test for qualitative variables. Multiple logistic regression analysis was performed to assess the association between 25(OH)D levels, albumin levels and death after adjustment for age, sex and BMI. It should be noted that chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, chronic kidney disease, congestive heart failure, peripheral venous insufficiency, and smoking were grouped into “risk factors,” given the low frequency of cases with these conditions. STATA v.12.0 (Stata Corp., College Station, TX, USA) was used for all statistical analyses.

Ethical consideration

According to the Declaration of Helsinki, the protocol was evaluated and approved by the National Research and Health Ethics Committee of the Mexican Social Security Institute (registry number, R-2020-785-090) and the Research and Health Ethics Committee of the Hospital Infantil de Mexico Federico Gómez (registry number, HIM-2020-045). Written informed consent was obtained from all patients or their legal guardians.

RESULTS

Among a total of 104 patients with critical COVID-19 who were admitted during the study period, serum 25(OH)D levels were not determined at the time of admission in 10 patients; therefore, the study cohort comprised 94 patients (Table 1). The median age was 61.5 years, with a male predominance (59.6%). There was a high frequency of obesity (63.8%), DM2 (61.7%) and hypertension (37.2%). Only 8 patients (8.5%) did not have any risk factors.

Table 1. Demographic and clinical characteristics and serum 25(OH)D levels of all patients.

| Characteristic | All patients (n = 94) | |

|---|---|---|

| Sex | ||

| Female | 38 (40.4) | |

| Male | 56 (59.6) | |

| Age (yrs) | 61.5 (57.0–63.0) | |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 31.9 (30.8–32.6) | |

| Obesity | 60 (63.8) | |

| Hypertension | 35 (37.2) | |

| Diabetes type 2 | 58 (61.7) | |

| Other risk factors | 17 (18.1) | |

| Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease | 3 (3.2) | |

| Chronic kidney disease | 7 (7.4) | |

| Congestive heart failure | 3 (3.2) | |

| Peripheral venous insufficiency | 2 (2.1) | |

| Smoking | 2 (2.1) | |

| Albumin (g/dL) | 2.48 (2.36–2.82) | |

| < 3.5 | 76 (80.9) | |

| 25(OH)D (ng/mL) | 12.7 (12.0–14.0) | |

| < 20 | 79 (84.0) | |

| 20–29.9 | 14 (14.9) | |

| ≥ 30 | 1 (1.1) | |

Values are presented as number of patients (%) or median (95% confidence interval).

BMI, body mass index; 25(OH)D, 25-hydroxyvitamin D.

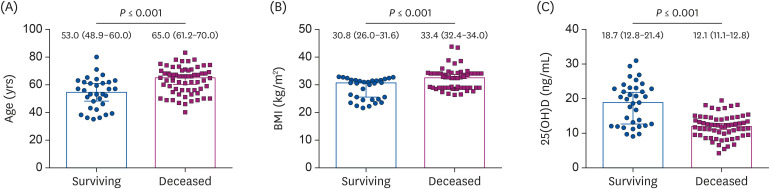

In total, 63 patients (67%) died during the study period. The deceased patients were significantly older than the surviving patients (65 vs. 53 years, P > 0.001). The deceased patients with critical COVID-19 had significantly higher BMI compared to the surviving patients with critical COVID-19 (33.4 vs. 30.8 kg/m2, P > 0.001; Fig. 1, Table 2).

Fig. 1. Comparison of age, BMI, and 25(OH)D level between the deceased and surviving patients with coronavirus disease 2019. (A) Age, (B) BMI, and (C) 25(OH)D.

Values are presented as median (95% confidence interval).

BMI, body mass index; 25(OH)D, 25-hydroxyvitamin D.

Table 2. Demographic and clinical characteristics between the deceased and surviving patients with COVID-19.

| Characteristic | Surviving patients (n = 31) | Deceased patients (n = 63) | P-value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sex | 0.812 | |||

| Female | 12 (38.7) | 26 (41.3) | ||

| Male | 19 (61.3) | 37 (58.7) | ||

| Obesity | 19 (61.3) | 41 (65.1) | 0.719 | |

| Hypertension | 9 (29.0) | 26 (41.3) | 0.249 | |

| Diabetes type 2 | 20 (64.5) | 38 (60.3) | 0.694 | |

| Other risk factors | 1 (3.2) | 16 (25.4) | 0.006 | |

| Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease | 0 (0) | 3 (4.8) | 0.296 | |

| Chronic kidney disease | 1 (3.2) | 6 (9.5) | 0.260 | |

| Congestive heart failure | 0 (0) | 3 (4.8) | 0.296 | |

| Peripheral venous insufficiency | 0 (0) | 2 (3.2) | 0.447 | |

| Smoking | 0 (0) | 2 (3.2) | 0.447 | |

| Albumin (g/dL) | 2.95 (2.6–3.4) | 2.36 (2.16–2.48) | 0.008 | |

| < 3.5 | 21 (67.7) | 55 (87.3) | 0.023 | |

| 25(OH)D (ng/dL) | 18.7 (12.8–21.4) | 12.1 (11.1–12.8) | < 0.001 | |

| < 20 | 16 (51.6) | 63 (100.0) | < 0.001 | |

| 20–29.9 | 14 (45.2) | 0 (0.0) | ||

| ≥ 30 | 1 (3.2) | 0 (0.0) | ||

Values are presented as number of patients (%) or median (95% confidence interval). Comparisons between the 2 groups were performed using the Mann-Whitney U test for quantitative variables and the χ2 or Fisher's exact test for qualitative variables.

COVID-19, coronavirus disease 2019; 25(OH)D, 25-hydroxyvitamin D.

The median 25(OH)D level was 12.7 ng/mL in the overall cohort. There were 15 (16%) and 79 (84%) patients with vitamin D insufficiency and vitamin D deficiency, respectively, and none of the patients in the entire study cohort had serum 25(OH)D levels within the normal limits (Table 1).

The median serum 25(OH)D and albumin level were significantly lower in the deceased patients than in the surviving patients (median 25[OH]D, 12.1 vs. 18.7 ng/mL, P < 0.001 and median albumin, 2.36 vs 2.95 g/dL, P = 0.008, respectively; Fig. 1, Table 2). Additionally, the rate of vitamin D deficiency was significantly higher in the deceased patients than in the surviving patients (100% vs. 51.6%, P < 0.001; Table 2).

The multivariate logistic regression analysis revealed that older age, higher BMI and the presence of other risk factors were associated with mortality, while higher levels of 25(OH)D were a protective factor for mortality in patients with critical COVID-19 (Table 3). As also shown in Table 3, hypertension, diabetes, and albumin levels were not identified as prognostic factors.

Table 3. Multivariate logistic regression analysis for independent predictors of in-hospital mortality (n = 94).

| Characteristic | OR | 95% confidence interval | P-value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (yrs) | 1.12 | 1.03–1.21 | 0.004 |

| Body mass index (kg/m2) | 1.45 | 1.13–1.86 | 0.003 |

| Other risk factors | 22.83 | 1.14–454.9 | 0.040 |

| 25(OH)D (ng/mL) | 0.81 | 0.70–0.93 | 0.005 |

| Sex (male) | 2.51 | 0.60–10.50 | 0.205 |

| Hypertension | 0.85 | 0.19–3.67 | 0.834 |

| Diabetes mellitus | 0.46 | 0.09–2.35 | 0.358 |

| Albumin (g/dL) | 0.50 | 0.18–1.39 | 0.189 |

Other included chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, chronic kidney disease, congestive heart failure, peripheral venous insufficiency and smoking.

OR, odds ratio; 25(OH)D, 25-hydroxyvitamin D.

DISCUSSION

In this prospective study conducted in a single institution in Mexico City, we found that the rate of vitamin D deficiency was high in patients with critical COVID-19 and that none of the 94 patients included in the study had normal vitamin D levels. Importantly, we found that a significantly higher rate of the deceased patients had vitamin D deficiency compared with the surviving patients (100% vs. 51.6%).

Vitamin D is associated with reduced risk of respiratory tract infections through several pathways. First, vitamin D plays a role in the maintenance of tight cell junctions by acting as a physical barrier. In addition, vitamin D is involved in innate cellular response by eliminating viruses through the production of β2-defensin and cathelicidin by macrophages, monocyte and keratinocytes, which increases their antimicrobial activity [15]. Furthermore, in the respiratory tract, CYP27B1 (via 1-alpha hydroxylase, the final activation of vitamin D) [16] is expressed in bronchial epithelial cells and induced by inflammatory stimuli, producing the LL37 peptide. This antimicrobial peptide may be activated locally upon infection, which further suggests a role for vitamin D in host defense [17]. Thus, it is not surprising that vitamin D insufficiency, not necessarily deficiency, increases susceptibility to bacterial and viral infections [18,19,20].

Importantly, the present study also revealed that none of the patients had vitamin D levels within the normal limits. Studies have previously reported high prevalence rates of vitamin D deficiency in Latin American countries [21], including Mexico [22]. Additionally, studies have suggested additional factors other than high-latitude might predispose individuals in tropical countries to vitamin D deficiency despite sufficient sunlight [23]. For example, dark skin, use of sunscreen, and pollution affect the synthesis of vitamin D3 in the skin [24,25] whereas low vitamin D intake, obesity, and advanced age reduce the bioavailability of 25(OH)D [26,27]. A recent study in Mexico City demonstrated a positive relationship between pollution and COVID-19 mortality, which was significantly increased with age and appeared to be primarily driven by long- rather than short-term exposure [28]. This finding might be related to the high frequency of vitamin D deficiency observed in the present study, in addition to the chronic diseases, such as DM, obesity and hypertension, which are closely related to vitamin D deficiency, also observed in the present study [29]. Likewise, we also found that the COVID-19 mortality rate increased with increasing patient age. This finding, consistent with previous studies [30,31], might be related to the increasing incidence of chronic diseases with age, which can worsen COVID-19 complications. Additionally, chronic diseases and advanced age both contribute to reduced 25(OH)D bioavailability [32].

It has already been described that hypoalbuminemia is a risk factor for mortality in patients with critical COVID-19 [33], which was also observed in this study (Table 2) (67.7% vs. 87.3% P = 0.023); however, in the multivariate analysis it was not demonstrated, this may be due to the sample size.

In addition to clinical evidence showing the potential detrimental effect of vitamin D deficiency on upper respiratory tract viral infections, experimental evidence supports the antiviral and immunity-boosting roles of vitamin D, with studies evaluating the association of vitamin D with mortality in patients with COVID-19 [34]. In the present study, vitamin D deficiency was present in 84% of all patients and 100% of deceased patients, consistent with previous studies [12,35,36]. For example, in their study of 30 patients with COVID-19 who required ICU admission, Vassiliou et al. [35] reported that 80% of the patients had vitamin D deficiency and that none of the cohort patients had normal vitamin D levels, in agreement with our findings; the authors found that the rate of deceased patients was higher among those with vitamin D levels < 15.2 ng/mL. De Smet et al. [12] analyzed 186 patients hospitalized for COVID-19 with unknown disease severity and found that 59% of the patients had vitamin D deficiency at the time of admission; the authors also reported that vitamin D deficiency at the time of admission was associated with increased COVID-19 mortality (odds ratio, 3.87). Finally, in a retrospective study of 149 patients hospitalized for COVID-19, including 102 patients with severe COVID-19, Karahan and Katkat [11] found that 93.1% of the patients had vitamin D deficiency and that serum 25(OH)D levels were independently associated with increased mortality.

Vitamin D interacts with the renin-angiotensin system, a route utilized for entry by SARS-CoV-2, which interacts with angiotensin converting enzyme receptors [37]. Likewise, increased renin activity, higher angiotensin II concentrations, and higher renin-angiotensin system activity has been shown to result from low vitamin D concentrations [38].

There is not enough evidence to show that vitamin D supplementation improves the evolution of respiratory tract viral infections; however, several studies have shown that vitamin D supplementation prevents respiratory tract viral infections in populations with vitamin D deficiency [39]. Therefore, randomized controlled clinical trials should be considered to evaluate whether vitamin D supplementation in populations at risk for vitamin D deficiency prevents the development of severe disease and death in patients with COVID-19.

In the present study, one major limitation was the inclusion of only patients with critical COVID-19, which might explain the higher mortality and greater vitamin D deficiency rates observed in the study, compared to other studies. In addition, the sample size was relatively small.

In conclusion, vitamin D deficiency was present in 84% of patients with critical COVID-19 and 100% of deceased patients with COVID-19 and vitamin D deficiency. Older age, high BMI, presence of other risk factors were associated with increased mortality and, higher 25(OH)D level were associated with decreased mortality in patients with critical COVID-19.

Footnotes

Funding: This work was supported by a Mexican Federal Funds Grant (HIM 2020/131).

Conflict of Interest: The authors declare no potential conflicts of interests.

- Conceptualization: Parra-Ortega I, Zurita-Cruz JN.

- Formal analysis: Parra-Ortega I, Zurita-Cruz JN.

- Funding acquisition: Villasis-Keever MA, Zurita-Cruz JN.

- Investigation: Alcara-Ramírez DG, Elías-García F, Mata-Chapol JA, Cervantes-Cote AD.

- Methodology: Parra-Ortega I, Zurita-Cruz JN.

- Writing - review & editing: Villasis-Keever MA, Ronzon-Ronzon AA, López-Martínez B.

SUPPLEMENTARY MATERIAL

Diagnosis of coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19)

References

- 1.World Health Organization (WHO) COVID-19 [Internet] Geneva: World Health Organization; 2021. [cited 2021 November 3]. Available from: https://covid19.who.int/ [Google Scholar]

- 2.Gobierno de Mexico. Datos Abiertos Dirección General de Epidemiología [Internet] Mexico City: Gobierno de Mexico; 2021. [cited 2021 November 3]. Available from: https://datos.covid-19.conacyt.mx/ [Google Scholar]

- 3.Epidemiology Working Group for NCIP Epidemic Response, Chinese Center for Disease Control and Prevention. The epidemiological characteristics of an outbreak of 2019 novel coronavirus diseases (COVID-19) in China. Zhonghua Liu Xing Bing Xue Za Zhi. 2020;41:145–151. doi: 10.3760/cma.j.issn.0254-6450.2020.02.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Laird E, Rhodes J, Kenny RA. Vitamin D and inflammation: potential implications for severity of COVID-19. Ir Med J. 2020;113:81. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Palacios C, Gonzalez L. Is vitamin D deficiency a major global public health problem? J Steroid Biochem Mol Biol. 2014;144(Pt A):138–145. doi: 10.1016/j.jsbmb.2013.11.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Contreras-Manzano A, Villalpando S, Robledo-Pérez R. Vitamin D status by sociodemographic factors and body mass index in Mexican women at reproductive age. Salud Publica Mex. 2017;59:518–525. doi: 10.21149/8080. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Flores M, Sánchez-Romero LM, Macías N, Lozada A, Díaz E, Barquera SE. Concentraciones séricas de vitamina D en niños, adolescentes y adultos mexicanos. Resultados de la ENSANUT 2006 [Internet] Cuernavaca: Instituto Nacional de Salud Pública; 2011. [cited 2021 May 23]. Available from: https://www.insp.mx/images/stories/Centros/cinys/Docs/111202_ReporteVitaminaD.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Greiller CL, Martineau AR. Modulation of the immune response to respiratory viruses by vitamin D. Nutrients. 2015;7:4240–4270. doi: 10.3390/nu7064240. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sørensen OE, Follin P, Johnsen AH, Calafat J, Tjabringa GS, Hiemstra PS, Borregaard N. Human cathelicidin, hCAP-18, is processed to the antimicrobial peptide LL-37 by extracellular cleavage with proteinase 3. Blood. 2001;97:3951–3959. doi: 10.1182/blood.v97.12.3951. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Barlow PG, Svoboda P, Mackellar A, Nash AA, York IA, Pohl J, Davidson DJ, Donis RO. Antiviral activity and increased host defense against influenza infection elicited by the human cathelicidin LL-37. PLoS One. 2011;6:e25333. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0025333. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Karahan S, Katkat F. Impact of serum 25(OH) vitamin D level on mortality in patients with COVID-19 in Turkey. J Nutr Health Aging. 2021;25:189–196. doi: 10.1007/s12603-020-1479-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.De Smet D, De Smet K, Herroelen P, Gryspeerdt S, Martens GA. Serum 25(OH)D level on hospital admission associated with COVID-19 stage and mortality. Am J Clin Pathol. 2021;155:381–388. doi: 10.1093/ajcp/aqaa252. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Alguwaihes AM, Al-Sofiani ME, Megdad M, Albader SS, Alsari MH, Alelayan A, Alzahrani SH, Sabico S, Al-Daghri NM, Jammah AA. Diabetes and COVID-19 among hospitalized patients in Saudi Arabia: a single-centre retrospective study. Cardiovasc Diabetol. 2020;19:205. doi: 10.1186/s12933-020-01184-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Amrein K, Scherkl M, Hoffmann M, Neuwersch-Sommeregger S, Köstenberger M, Tmava Berisha A, Martucci G, Pilz S, Malle O. Vitamin D deficiency 2.0: an update on the current status worldwide. Eur J Clin Nutr. 2020;74:1498–1513. doi: 10.1038/s41430-020-0558-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sassi F, Tamone C, D’Amelio P. Vitamin D: Nutrient, Hormone, and Immunomodulator. Nutrients. 2018;10:1656. doi: 10.3390/nu10111656. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hewison M. Antibacterial effects of vitamin D. Nat Rev Endocrinol. 2011;7:337–345. doi: 10.1038/nrendo.2010.226. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hansdottir S, Monick MM, Hinde SL, Lovan N, Look DC, Hunninghake GW. Respiratory epithelial cells convert inactive vitamin D to its active form: potential effects on host defense. J Immunol. 2008;181:7090–7099. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.181.10.7090. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Vanherwegen AS, Gysemans C, Mathieu C. Regulation of immune function by vitamin D and its use in diseases of immunity. Endocrinol Metab Clin North Am. 2017;46:1061–1094. doi: 10.1016/j.ecl.2017.07.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hewison M. Vitamin D and the immune system: new perspectives on an old theme. Endocrinol Metab Clin North Am. 2010;39:365–379. doi: 10.1016/j.ecl.2010.02.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Grant WB, Lahore H, McDonnell SL, Baggerly CA, French CB, Aliano JL, Bhattoa HP. Evidence that vitamin D supplementation could reduce risk of influenza and COVID-19 infections and deaths. Nutrients. 2020;12:988. doi: 10.3390/nu12040988. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Brito A, Cori H, Olivares M, Fernanda Mujica M, Cediel G, López de Romaña D. Less than adequate vitamin D status and intake in Latin America and the Caribbean: a problem of unknown magnitude. Food Nutr Bull. 2013;34:52–64. doi: 10.1177/156482651303400107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Carrillo-Vega MF, García-Peña C, Gutiérrez-Robledo LM, Pérez-Zepeda MU. Vitamin D deficiency in older adults and its associated factors: a cross-sectional analysis of the Mexican Health and Aging Study. Arch Osteoporos. 2017;12:8. doi: 10.1007/s11657-016-0297-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Mendes MM, Hart KH, Botelho PB, Lanham-New SA. Vitamin D status in the tropics: is sunlight exposure the main determinant? Nutr Bull. 2018;43:428–434. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Norval M, Wulf HC. Does chronic sunscreen use reduce vitamin D production to insufficient levels? Br J Dermatol. 2009;161:732–736. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2133.2009.09332.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Brenner M, Hearing VJ. The protective role of melanin against UV damage in human skin. Photochem Photobiol. 2008;84:539–549. doi: 10.1111/j.1751-1097.2007.00226.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Vranić L, Mikolašević I, Milić S. Vitamin D deficiency: consequence or cause of obesity? Medicina (Kaunas) 2019;55:541. doi: 10.3390/medicina55090541. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Chang SW, Lee HC. Vitamin D and health - The missing vitamin in humans. Pediatr Neonatol. 2019;60:237–244. doi: 10.1016/j.pedneo.2019.04.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.López-Feldman A, Heres D, Marquez-Padilla F. Air pollution exposure and COVID-19: a look at mortality in Mexico City using individual-level data. Sci Total Environ. 2021;756:143929. doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2020.143929. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Wang H, Chen W, Li D, Yin X, Zhang X, Olsen N, Zheng SG. Vitamin D and chronic diseases. Aging Dis. 2017;8:346–353. doi: 10.14336/AD.2016.1021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Docherty AB, Harrison EM, Green CA, Hardwick HE, Pius R, Norman L, Holden KA, Read JM, Dondelinger F, Carson G, et al. Features of 20 133 UK patients in hospital with covid-19 using the ISARIC WHO Clinical Characterisation Protocol: prospective observational cohort study. BMJ. 2020;369:m1985. doi: 10.1136/bmj.m1985. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Rezende LF, Thome B, Schveitzer MC, Souza-Júnior PR, Szwarcwald CL. Adults at high-risk of severe coronavirus disease-2019 (Covid-19) in Brazil. Rev Saude Publica. 2020;54:50. doi: 10.11606/s1518-8787.2020054002596. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Martínez-Zavala N, López-Sánchez GN, Vergara-Lopez A, Chávez-Tapia NC, Uribe M, Nuño-Lámbarri N. Vitamin D deficiency in Mexicans have a high prevalence: a cross-sectional analysis of the patients from the Centro Médico Nacional 20 de Noviembre. Arch Osteoporos. 2020;15:88. doi: 10.1007/s11657-020-00765-w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Acharya R, Poudel D, Bowers R, Patel A, Schultz E, Bourgeois M, Paswan R, Stockholm S, Batten M, Kafle S, et al. Low serum albumin predicts severe outcomes in COVID-19 infection: a single-center retrospective case-control study. J Clin Med Res. 2021;13:258–267. doi: 10.14740/jocmr4507. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Munshi R, Hussein MH, Toraih EA, Elshazli RM, Jardak C, Sultana N, Youssef MR, Omar M, Attia AS, Fawzy MS, et al. Vitamin D insufficiency as a potential culprit in critical COVID-19 patients. J Med Virol. 2021;93:733–740. doi: 10.1002/jmv.26360. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Vassiliou AG, Jahaj E, Pratikaki M, Orfanos SE, Dimopoulou I, Kotanidou A. Low 25-hydroxyvitamin D levels on admission to the intensive care unit may predispose COVID-19 pneumonia patients to a higher 28-day mortality risk: a pilot study on a Greek ICU cohort. Nutrients. 2020;12:3773. doi: 10.3390/nu12123773. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Allegra A, Tonacci A, Pioggia G, Musolino C, Gangemi S. Vitamin deficiency as risk factor for SARS-CoV-2 infection: correlation with susceptibility and prognosis. Eur Rev Med Pharmacol Sci. 2020;24:9721–9738. doi: 10.26355/eurrev_202009_23064. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Cano F, Gajardo M, Freundlich M. Renin angiotensin axis, angiotensin converting enzyme 2 and coronavirus. Rev Chil Pediatr. 2020;91:330–338. doi: 10.32641/rchped.vi91i3.2548. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Catanzaro M, Fagiani F, Racchi M, Corsini E, Govoni S, Lanni C. Immune response in COVID-19: addressing a pharmacological challenge by targeting pathways triggered by SARS-CoV-2. Signal Transduct Target Ther. 2020;5:84. doi: 10.1038/s41392-020-0191-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Martineau AR, Jolliffe DA, Hooper RL, Greenberg L, Aloia JF, Bergman P, Dubnov-Raz G, Esposito S, Ganmaa D, Ginde AA, et al. Vitamin D supplementation to prevent acute respiratory tract infections: systematic review and meta-analysis of individual participant data. BMJ. 2017;356:i6583. doi: 10.1136/bmj.i6583. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Diagnosis of coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19)