Abstract

Purpose

Cancer patients have been shown to frequently suffer from financial burden before, during, and after treatment. However, the financial toxicity of patients with sarcoma has seldom been assessed. Therefore, the aim of this study was to evaluate whether financial toxicity is a problem for sarcoma patients in Germany and identify associated risk factors.

Methods

Patients for this analysis were obtained from a multicenter prospective cohort study conducted in Germany. Using the financial difficulties scale of the EORTC QLQ-C30, financial toxicity was considered to be present if the score exceeded a pre-defined threshold for clinical importance. Comparisons to an age- and sex-matched norm population were performed. A multivariate logistic regression using stepwise backward selection was used to identify factors associated with financial toxicity.

Results

We included 1103 sarcoma patients treated in 39 centers and clinics; 498 (44.7%) patients reported financial toxicity. Sarcoma patients had 2.5 times the odds of reporting financial difficulties compared to an age- and sex-matched norm population. Patient age < 40 and > 52.5 years, higher education status, higher income, and disease progression (compared to patients with complete remission) were associated with lower odds of reporting financial toxicity. Receiving a disability pension, being currently on sick leave, and having a disability pass were statistically significantly associated with higher odds of reporting financial toxicity.

Conclusion

Financial toxicity is present in about half of German sarcoma patients, making it a relevant quality of life topic for patients and decision-makers.

Keywords: Sarcoma, Financial toxicity, Burden, Cancer, Germany, Financial difficulties

Introduction

Sarcomas are a rare group of cancers of mesenchymal origin and are estimated to represent 1 to 2% of adult cancers worldwide [1]. The 5-year overall survival probability amounts to approximately 60% and depends on a variety of risk factors [2]. Quality of life impairments among sarcoma patients have been reported across all sarcoma subgroups and are present during diagnosis, treatment, and follow-up [3].

One important aspect of quality of life that has gained increasing awareness within the last years is the financial burden of cancer patients. The financial burden of cancer refers not only to out-of-pocket payments (OOPPs) and income losses, but also material consequences and psychological effects or behavioral changes that are then expressed as financial toxicity [4–7]. It has been shown that patients reporting financial difficulties may have an increased risk of distress, anxiety, and depression [8, 9], show impairments in quality of life [8–11], and may even have worse survival [12]. This problem is not only observed in countries with high OOPPs, like the USA, but also in countries with universal health coverage [13–16].

Financial toxicity studies are often conducted in general cancer populations or are performed for the most common cancers, such as lung, breast, or colon cancer [13–19]. To our knowledge, studies evaluating financial toxicity in sarcoma patients in detail have not been performed. It has, however, been shown that the financial impact of the disease and the resulting financial toxicity is an important and relevant topic for patients with sarcoma [17]. Additionally, patients can be diagnosed with sarcoma throughout the whole course of life [1, 2] and therefore also during their social, educational, and occupational development and this might also influence their financial abilities throughout the rest of their life.

Therefore, the aim of this study was to evaluate the extent of financial toxicity in German sarcoma patients and survivors in Germany and identify possible risk factors.

Methods

Design

Patients for this analysis were obtained from the PROSa study, which is a multicenter prospective cohort study conducted in Germany with two follow-ups at 6 and 12 months after baseline. Follow-up was defined as a visit to one of the participating study centers [18]. The baseline data used for this analysis were obtained between 09/2017 and 02/2019. Inclusion criteria for the PROSa study were a confirmed diagnosis of any type of sarcoma regardless of the current stage of the disease course (at diagnosis, in treatment, or in follow-up) and the ability to give written informed consent. Patients who were not able to fill out questionnaires due to linguistic reasons (restricted to German language) or cognitive impairment were excluded from the study. Ethical approval was obtained by the ethics committee of the Technical University of Dresden (AZ: EK 1,790,422,017) and the ethics committees of the participating centers. A more detailed description of the PROSa study can be found in [18].

Assessments

Clinical data of the participants were obtained using case report forms through the participating medical centers. Aftercare was defined as “yes” for patients with being in after care or for having completed their treatment. Sociodemographic data and patient reported outcomes (PROs) were directly obtained from the patient by letter or online questionnaires. The following socioeconomic and sociodemographic variables were used for the analysis: age, sex, education, occupation, employment status, income, sick leave status, and whether a patient had a disability pass. Education was defined by the highest educational certificate attained divided into the following categories: none to secondary (8/9 years), secondary school (10 years), vocational baccalaureate, high school/baccalaureate, and other/unknown. Occupation was assessed by the classification of labor type (e.g., blue-collar worker, civil servant) and employment status was determined by the employment setting (e.g., self-employed, retired, etc.). Income was assessed using the OECD equivalence scale [19] as a continuous variable but also categorized into income groups ≤ €1250, €1251 to €1750, €1751 to €2250, €2251 to €2750, > €2750, and unknown.

For the assessment of financial toxicity, the financial difficulties scale of the EORTC QLQ-C30 was used [20]. This 1-item scale measures whether the physical conditions or the medical treatment has caused any financial difficulties within the last week using a four-point Likert scale (“not at all,” “a little,” “quite a bit,” and “very much”). The answer is converted to a scale ranging from 0 to 100, with high values indicating a high financial burden perceived by the patient in accordance with the scoring manual of the EORTC [21]. Patients were considered to have financial toxicity if their score in the financial difficulties scale was above the threshold for clinical importance (17 points) identified by Giesinger et al. [22]. Patients with a score above 17 points at least report any financial difficulties (“a little,” “quite a bit,” or “very much”).

Statistical analysis

The analysis was performed on a cross-sectional basis. Patient characteristics are expressed as mean values or percentages according to the data. Univariate comparisons between patients with financial toxicity and patients without were conducted using Chi-square tests. Financial difficulty scores of all sarcoma patients, curative sarcoma patients, and palliative sarcoma patients were compared to a norm population [23]. Multivariate logistic regression with backward stepwise selection with p > 0.1 as the exclusion criterion was performed with reporting financial difficulties (yes/no) as the dependent variable and clinical and socioeconomic characteristics as independent variables (Table 1). Variables were included in regression after being tested for non-multicollinearity (correlation < 0.8). All statistical analyses were performed using IBM SPSS Statistics version 25.0 (Armonk, NY).

Table 1.

Description of baseline characteristics

| Variable | Value | All N = 1103 (column%) |

Financial toxicity—yes N = 498 (44.7%) |

Financial toxicity—no N = 605 (54.9%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Socioeconomic factors | ||||

| Sex | Female | 537 (48.7) | 243 (48.8) | 294 (48.7) |

| Male | 565 (51.3) | 255 (51.2) | 310 (51.3) | |

| Age at study inclusion*,** | Mean | 56.6 (SD 15.8) | 54.5 (SD 14.5) | 58.4 (SD 16.6) |

| Median IQR | 58.4 (47.6; 68.5) | 55.4 (46.6; 63.6) | 61.6 (49.8; 70.6) | |

| Age at study inclusion—group* | 18– < 27.5 years | 78 (7.1) | 33 (6.7) | 45 (7.4) |

| 27.5– < 40 year | 104 (9.4) | 44 (8.9) | 60 (9.9) | |

| 40– < 52.5 years | 194 (17.6) | 121 (24.4) | 73 (12.1) | |

| 52.5– < 65 years | 366 (33.2) | 194 (39.1) | 172 (28.4) | |

| 65– < 77.5 years | 277 (25.2) | 81 (16.3) | 196 (32.4) | |

| > 77.5 years | 82 (7.4) | 23 (4.6) | 59 (9.8) | |

| Household size (living alone)# | No | 887 (80.4) | 400 (80.3) | 487 (80.5) |

| Yes | 206 (18.7) | 93 (18.7) | 113 (18.7) | |

| Unknown | 10 (0.9) | 5 (1.0) | 5 (0.8) | |

| Children in household# | No | 884 (80.1) | 392 (78.7) | 492 (81.3) |

| Yes | 151 (13.7) | 73 (14.7) | 78 (12.9) | |

| Unknown | 68 (6.2) | 33 (6.6) | 35 (5.8) | |

| School leaving certificate*,# | None to secondary school (8/9 years) | 264 (23.9) | 143 (28.7) | 121 (20.0) |

| Secondary school (10 years) | 376 (34.1) | 177 (35.5) | 199 (32.9) | |

| Vocational baccalaureate | 120 (10.9) | 51 (10.2) | 69 (11.4) | |

| High school/baccalaureate | 317 (28.7) | 115 (23.1) | 202 (33.4) | |

| Something else/unknown | 26 (2.4) | 12 (2.4) | 14 (2.3) | |

| Occupational status*,# | Blue-collar worker | 208 (18.9) | 118 (23.7) | 90 (14.9) |

| Civil servant (1) | 81 (7.3) | 23 (4.6) | 58 (9.6) | |

| White collar worker (2) | 611 (55.4) | 266 (53.4) | 345 (57.0) | |

| Self-employed (3) | 104 (9.4) | 49 (9.8) | 55 (9.1) | |

| Unknown/not applicable (4) | 99 (9.0) | 42 (8.4) | 57 (9.4) | |

| Equivalent income*,** | Mean (standard deviation) | 2047€ (1105€) | 1800€ (1010€) | 2251€ (1138€) |

| Equivalized income*,# | ≤ 1250 | 231 (20.9) | 135 (27.1) | 96 (15.9) |

| 1250.1–1750 | 213 (19.3) | 115 (23.1) | 98 (16.2) | |

| 1750.1–2250 | 247 (22.4) | 103 (20.7) | 144 (23.8) | |

| 2250.1–2750 | 89 (8.1) | 26 (5.2) | 63 (10.4) | |

| ≥ 2750.1 | 184 (16.7) | 58 (11.6) | 126 (20.8) | |

| Unknown | 139 (12.6) | 61 (12.2) | 78 (12.9) | |

| Employment status*,# | Employed/self-employed | 490 (44.4) | 226 (45.4) | 264 (43.6) |

| Unemployed | 45 (4.1) | 31 (6.2) | 14 (2.3) | |

| Disability pension | 138 (12.5) | 103 (20.7) | 35 (5.8) | |

| Early retirement/retirement pension/partial retirement | 376 (34.1) | 114 (22.9) | 262 (43.3) | |

| Housewife/houseman | 26 (2.4) | 11 (2.2) | 15 (2.5) | |

| School, apprenticeship, study | 17 (1.5) | 8 (1.6) | 9 (1.5) | |

| Unknown | 11 (1.0) | 5 (1.0) | 6 (1.0) | |

| Sick leave*,# | No | 822 (74.5) | 327 (65.7) | 495 (81.8) |

| Yes | 257 (23.3) | 163 (32.7) | 94 (15.5) | |

| Unknown | 24 (2.2) | 8 (1.6) | 16 (2.6) | |

| Disabled person pass*,# | No | 405 (36.7) | 131 (26.3) | 274 (45.3) |

| Yes | 689 (62.5) | 364 (73.1) | 325 (53.7) | |

| Unknown | 9 (0.8) | 3 (0.6) | 6 (1.0) | |

| Clinical factors | ||||

| Time since diagnosis# | 0– < 0.5 years | 209 (19.0) | 95 (19.1) | 114 (18.9) |

| 0.5– < 1 year | 126 (11.4) | 67 (13.5) | 59 (9.8) | |

| 1– < 2 years | 165 (15.0) | 79 (15.9) | 86 (14.2) | |

| 2– < 5 years | 290 (26.3) | 131 (26.4) | 159 (26.3) | |

| More than 5 years | 311 (28.2) | 125 (25.2) | 186 (30.8) | |

| Sarcoma type—detail§ | Liposarcoma | 210 (19.1) | 94 (19.0) | 116 (19.2) |

| Unclassified sarcoma (1) | 163 (14.8) | 68 (13.7) | 95 (15.7) | |

| Fibroblastic, myofibroblastic, fibrohistiocytic sarcoma (2) | 130 (11.8) | 52 (10.5) | 78 (12.9) | |

| GIST (3) | 130 (11.8) | 51 (10.3) | 79 (13.0) | |

| Leiomyosarcoma (4) | 131 (11.9) | 66 (13.3) | 65 (10.8) | |

| Osteosarcoma (5) | 71 (6.5) | 30 (6.0) | 41 (6.8) | |

| Chondrosarcoma (6) | 63 (5.7) | 32 (6.5) | 31 (5.1) | |

| Ewing sarcoma (7) | 43 (3.9) | 28 (5.6) | 15 (2.5) | |

| Synovial sarcoma (8) | 47 (4.3) | 24 (4.8) | 23 (3.8) | |

| Other (9) | 112 (10.2) | 51 (10.3) | 61 (10.1) | |

| Site§ | Trunk | 518 (47.1) | 231 (44.6) | 287 (47.5) |

| Limbs | 522 (47.5) | 234 (47.1) | 288 (47.7) | |

| Somewhere else | 60 (5.5) | 31 (6.3) | 29 (4.8) | |

| Grading§ | Low grade | 137 (12.4) | 52 (10.4) | 85 (14.0) |

| High grade | 598 (54.2) | 283 (56.8) | 315 (52.1) | |

| Not applicable/unknown | 368 (33.4) | 163 (32.7) | 205 (33.9) | |

| T-Stage§ | T1 | 171 (15.5) | 76 (15.3) | 95 (15.7) |

| T2–T4 | 516 (46.8) | 232 (46.6) | 284 (46.9) | |

| Other/unknown | 416 (37.7) | 190 (38.2) | 226 (37.4) | |

| Malignancy of tumor*,§ | Locally aggressive + rarely metastatic | 86 (7.8) | 28 (5.6) | 58 (9.6) |

| Malignant | 1014 (92.2) | 468 (94.4) | 546 (90.4) | |

| Metastasis until time of study inclusion* | No metastasis | 604 (54.8) | 252 (50.6) | 352 (58.2) |

| Metastasis | 365 (33.1) | 180 (36.1) | 185 (30.6) | |

| Unknown | 134 (12.1) | 66 (13.3) | 68 (11.2) | |

| Tumor recurrence***,# | No recurrence | 794 (72.0) | 355 (71.3) | 439 (72.6) |

| Recurrence | 278 (25.2) | 127 (25.5) | 151 (25.0) | |

| Suspicion | 12 (1.1) | 7 (1.4) | 5 (0.8) | |

| Unknown | 19 (1.7) | 9 (1.8) | 10 (1.7) | |

| Treatment intention**,# | Curative | 820 (74.6) | 359 (72.5) | 461 (76.3) |

| Palliative | 258 (49.6) | 128 (25.9) | 130 (21.5) | |

| Unknown | 21 (1.9) | 8 (4.2) | 13 (2.2) | |

| Disease status# | Complete remission | 491 (44.5) | 219 (44.0) | 272 (45.0) |

| Partial remission/stable disease | 326 (29.6) | 148 (29.7) | 178 (29.4) | |

| Progressive | 160 (14.5) | 68 (13.7) | 92 (15.2) | |

| Unknown | 126 (11.4) | 63 (12.7) | 63 (10.4) | |

| Aftercare status*,# | Not in aftercare | 468 (42.4) | 231 (46.4) | 237 (39.2) |

| In aftercare | 620 (56.2) | 262 (52.6) | 358 (59.2) | |

| Unknown | 15 (1.2) | 5 (1.0) | 10 (1.7) | |

| Surgery***,# | No | 126 (11.4) | 59 (11.8) | 67 (11.1) |

| Yes | 969 (87.9) | 435 (87.3) | 534 (88.3) | |

| Unknown | 8 (0.7) | 4 (0.8) | 4 (0.7) | |

| Chemotherapy*,***,# | No | 568 (51,5) | 228 (45.8) | 340 (56.2) |

| Yes | 523 (47.4) | 264 (53.1) | 259 (42.8) | |

| Unknown | 12 (1.1) | 6 (1.2) | 6 (1.0) | |

| Radiotherapy***,# | No | 646 (58.6) | 285 (57.2) | 361 (59.7) |

| Yes | 430 (39.0) | 201 (40.4) | 229 (37.9) | |

| Unknown | 27 (2.4) | 12 (2.4) | 15 (2.5) | |

| Treatment lines# | No treatment yet (1) | 26 (2.4) | 9 (1.8) | 17 (2.8) |

| One treatment line | 491 (44.5) | 216 (43.4) | 275 (45.5) | |

| More than one treatment line (2) | 547 (49.6) | 257 (51.6) | 290 (47.9) | |

| Unknown (3) | 39 (3.5) | 16 (3.2) | 23 (3.8) | |

*Chi-square p < 0.05

**Variable not in the multivariate model

***Model variable adapted

#At/until time of study inclusion

§At time of diagnosis

Results

Sample and patient characteristics

In total, 1309 sarcoma patients from 39 sarcoma centers and clinics participated in the study, of whom 1103 (84.3%) provided data regarding financial toxicity. The mean age of the study population at recruitment was 52.6 years, and 48.7% of the participants were female. Further sociodemographic and clinical characteristics can be found in Table 1.

Financial toxicity in German sarcoma patients

A total of 498 (44.7%) of the sarcoma patients reported suffering from financial difficulties above the threshold for clinical importance. Differences between patients with and without financial toxicity are presented in Table 1. Statistically significant differences between the two groups were seen for age, education, occupation, income, employment, disability pass, biological behavior of the tumor, metastasis at baseline, aftercare status, and chemotherapy.

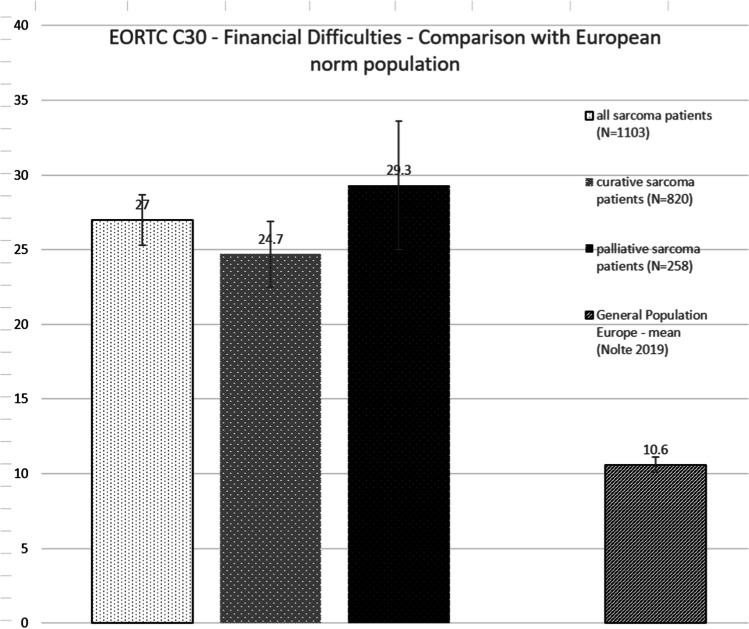

Compared to the German norm population [23], sarcoma patients in the study had statistically higher scores, indicating more problems in the financial difficulties scale; this difference also persisted after stratification into curative and palliative sarcoma patients (Fig. 1). All sarcoma patients had 2.5 times the odds of reporting financial difficulties compared to the age- and sex-matched norm population.

Fig. 1.

Comparison of financial difficulties scale to an age- and sex-adjusted norm population

Variables associated with financial toxicity in German sarcoma patients

The final variable selection of the multivariate logistic regression with backward stepwise selection and the respective results can be found in Table 2. Compared to the age group from 40 to < 52.5 years, younger (18 to < 27.5 years (OR: 0.45; 95% CI [0.23;0.88]), 27.5 to < 40 years (OR: 0.54; 95% CI [0.31;0.94])) and older (52.5 to < 65 years (OR: 0.66; 95% CI [0.44;0.99]), 65 to < 77.5 years (OR: 0.25; 95% CI [0.12;0.49]), and > 77.5 years (OR: 0.27; 95% CI [0.12;0.62])) age groups had statistically lower odds of reporting financial toxicity. Higher education (compared to none to secondary school; secondary school (OR: 0.57; 95% CI [0.39;0.84]), vocational baccalaureate (OR: 0.67; 95% CI [0.39;1.15]), high school/baccalaureate (OR: 0.51; 95% CI [0.33;0.79])) and higher income (compared to ≤ €1250; €1250.1 to €1750 (OR: 0.93; 95% CI [0.60;1.43]), €1750.1 to €2250 (OR: 0.47; 95% CI [0.30;0.72]), €2250.1 to €2750 (OR: 0.24; 95% CI [0.13;0.45]), ≥ €2750.1 (OR0.33; 95% CI [0.12;0.53])) were also associated with having lower chances of reporting financial toxicity. Receiving a disability pension (OR: 3.29; 95% CI [1.95;5.54], compared to employed/self-employed), being currently on sick leave (OR: 2.40; 95% CI [1.60;3.62]), compared to not being currently on sick leave), and having a disability pass (OR: 2.52; 95% CI [1.81;3.49]) were statistically significantly associated with higher odds of reporting financial toxicity. Patients more than 5 years post diagnosis (compared to 0 to < 0.5 years since diagnosis) reported statistically significant lower odds (OR: 0.58; 95% CI [0.35;0.94]) of reporting financial toxicity. Compared to patients with complete remission, patients with progressive disease had statistically significant lower odds (OR: 0.48; 95% CI [0.30;0.77]) of reporting financial toxicity, while for patients with partial remission/stable disease no differences in odds (OR: 0.96; 95% CI [0.67;1.37]) were observed.

Table 2.

Results of the multivariate logistic regression using stepwise backward selection with having financial difficulties as the dependent variable (final model)

| Independent variables | OR [95% CI] |

|---|---|

| Age at study inclusion (p = 0.002) | |

| 18 to < 27.5 years | 0.45 [0.23;0.88] |

| 27.5 to < 40 years | 0.54 [0.31;0.94] |

| 40 to < 52.5 years (reference category) | 1 |

| 52.5 to < 65 years | 0.66 [0.44;0.99] |

| 65 to < 77.5 years | 0.25 [0.12;0.49] |

| > 77.5 years | 0.27 [0.12;0.62] |

| Education (p = 0.023) | |

| None to secondary school (8/9 years) (ref.) | 1 |

| Secondary school (10 years) | 0.57 [0.39;0.84] |

| Vocational baccalaureate | 0.67 [0.39;1.15] |

| High school/baccalaureate | 0.51 [0.33;0.79] |

| Something else/unknown | 0.98 [0.37;2.60] |

| Occupational status (p = 0.081) | |

| Blue-collar worker (ref.) | 1 |

| Civil servant | 1.01 [0.52;1.98] |

| White collar worker | 0.95 [0.64;1.41] |

| Self-employed | 1.85 [1.04;3.27] |

| Unknown/not applicable | 0.76 [0.41;1.41] |

| Equivalent income (p < 0.001) | |

| ≤ €1250 (ref.) | 1 |

| €1250.1 to €1750 | 0.93 [0.60;1.43] |

| €1750.1 to €2250 | 0.47 [0.30;0.72] |

| €2250.1 to €2750 | 0.24 [0.13;0.45] |

| ≥ €2750.1 | 0.33 [0.12;0.53] |

| Unknown | 0.58 [0.35;0.94] |

| Employment status (p = 0.002) | |

| Employed/self-employed (ref.) | 1 |

| Unemployed | 1.58 [0.75;3.31] |

| Disability pension | 3.29 [1.95;5.54] |

| Early retirement/retirement pension/partial retirement | 1.13 [0.61;2.11] |

| Housewife/houseman | 1.40 [0.54;3.62] |

| School, apprenticeship, study | 1.24 [0.38;4.10] |

| Unknown | 1.34 [0.30;6.02] |

| Sick leave (p < 0.001) | |

| No (ref.) | 1 |

| Yes | 2.40 [1.60;3.62] |

| Unknown | 1.12 [0.37;3.39] |

| Disabled person pass (p < 0.001) | |

| No (ref.) | 1 |

| Yes | 2.52 [1.81;3.49] |

| Unknown | 1.30 [0.21;8.03] |

| Time since diagnosis (0 to < 0.5 years) (p = 0.024) | |

| 0 to < 0.5 years (ref.) | 1 |

| 0.5 to < 1 year | 1.31 [0.77;2.22] |

| 1 to < 2 years | 0.87 [0.52;1.47] |

| 2 to < 5 years | 0.83 [0.51;1.36] |

| More than 5 years | 0.58 [0.35;0.94] |

| Metastasis until baseline (p = 0.054) | |

| No metastasis (ref.) | 1 |

| Metastasis | 1.38 [0.97;1.97] |

| Unknown | 1.56 [1.01;2.41] |

| Disease status (p = 0.010) | |

| Complete remission (ref.) | 1 |

| Partial remission/stable disease | 0.96 [0.67;1.37] |

| Progressive | 0.48 [0.30;0.77] |

| Unknown | 1.11 [0.68;1.82] |

Variables included in the full model before backward selection: sex, age at study inclusion, household size, children in household, school leaving certificate, occupational status, equivalized income, employment status, sick leave, disabled person pass, time since diagnosis, sarcoma type, site, grading, T-Stage, malignancy of tumor, metastasis until baseline, tumor recurrence, disease status, aftercare status, treatment lines, and treatment received

Discussion

Our analysis showed that sarcoma patients suffer from financial difficulties in a universal health coverage system like Germany’s. 44.7% of the patients reported financial difficulties measured by the EORTC QLQ-C30, and 2.5 times the odds of reporting financial toxicity compared to an age- and sex matched norm population was observed.

These impairments regarding financial difficulties are in line with other studies using the financial difficulties scale of the QLQ-C30 in sarcoma patients [24–28]. Hudgens et al. [24] reported a financial difficulties score of 25.0 (SD: 29.5) at baseline and 29.5 (SD: 34.2) at progression in a study consisting of 452 sarcoma patients with advanced, progressing disease. A longitudinal study by Paredes et al. [25] with 36 sarcoma patients found higher financial difficulties scores compared to a norm population in the diagnostic phase and 4 months after initiation of treatment.

Financial difficulties are not restricted to sarcoma patients and have been observed in other cancer populations across different health care settings [13–16]. Financial toxicity often results from OOPPs, paid by the patient for the treatment of the disease and related care and from income changes. OOPPs in sarcoma patients alone have not been evaluated and were not assessed in our study. For other cancer entities and mixed cancer populations, it has been reported that OOPPs occur at a high level in countries with higher self-payments [29] but are also present at a moderate level in countries with universal health insurance [14, 30, 31]. For a German mixed cancer population, Büttner et al. [14] found average 3-month OOPPs of €205 at the end of hospital stay, and €180 and €148 at 3 and 15 months after their hospital stay.

Income losses may also have an impact on financial difficulties in cancer patients. In our study, regression analysis showed that higher income was significantly associated with lower chances of reporting financial toxicity. This is also in line with previous studies in other cancer populations [32]. Changes in income are often related to changes in one’s ability to work. Approximately 60–70% of all cancer patients return to work [15, 33], with the rest going into retirement or applying for disability pensions. Patients with sarcoma show the lowest return to work rates [34] and are considered to have a higher risk of not returning to work [35, 36]. A study by Laros et al. [37] showed that sarcoma patients in Germany had an average unemployment rate of 8.8 months and that for 67% of the sarcoma patients, the work situation changed after the unemployment phase. Patients in Germany are allowed up to 72 weeks of sick leave before returning to work or applying for a pension. In our study, 23.3% of the patients were currently on sick leave, and sick leave was associated with a higher chance for reporting financial difficulties. Hazell et al. [38] found a similar association of sick leave and financial toxicity in lung cancer patients in the USA. Patients on sick leave in Germany receive 70% of their gross salary from their health insurance [39]. This income reduction in combination with after treatment OOPPs [14] might lead to financial problems or financial insecurity.

Another possible factor for financial difficulties during sick leave might be the reduction of income due to high surcharges not covered by the insurance [40]. If patients are not able to return to work after sick leave, it is mandatory to apply for a disability pension in Germany. The average full disability pension, which applies if you are not able to work more than 3 h a day, was €850 in 2019 [41], indicating a severe income decline for patients who were fully working before their disease. Laros et al. [37] found an income loss of 62% on average for sarcoma patients in Germany who applied for a pension or partial or total unemployment benefits. The effect of this income decline is expressed in a statistically significantly increased chance of financial toxicity for patients receiving disability pension in our analysis, where having a disability pass was associated with higher odds of reporting financial toxicity. This might seem controversial because a disability pass may lead to deductions in certain services or payments (e.g., entrance fees, transportation tickets) [40]. On the other hand, patients with a disability pass might have higher OOPPs due to a need for additional services or medical aids which are not fully covered by their insurance.

Higher education was associated with lower chances of financial toxicity in our study, which is in line with findings for other cancer populations [32]. Our analysis has shown that, compared to the age group 40 to < 52.5 years, younger and older age groups reported lower chances for reporting financial toxicity. We can only speculate as to possible reasons for this finding. Older patients may have acquired higher financial reserves during their lifetime, while our reference age group might be at a disadvantage due to financial investments, such as loans or substantial purchases. Additionally, older patients are already retired, and the income losses due to the disease may not have as great an impact because they have a stable income from their pension fund. Younger patients, on the other hand, may not yet have substantial financial investments, which might explain the lower financial toxicity reported. Furthermore, their baseline income might be lower, so that the resulting difference to the disability pension sum might be less pronounced compared to older patients. Nevertheless, studies in other cancer patients have reported that younger age is more often associated with financial toxicity [32].

Another surprising finding of our study was that patients with progressive disease had lower odds of reporting financial toxicity compared to patients with complete remission. The association of disease status and financial toxicity has been rarely assessed in the literature. Zafar et al. [42] found no statistically significant association between patients with recurrent or progressive cancer and financial distress. On the other hand, Walker et al. [43] reported more financial difficulties in patients with disease progression for advanced non-squamous NSCLC. A Finish study examining the OOPPs of breast, prostate, and colorectal cancer patients reported the lowest 6-month OOPPs for patients in remission (€224) compared to palliative patients (€603), patients with metastatic disease (€383), in rehabilitation (€264), and in primary treatment (€263) [44]. Future studies should address this issue in sarcoma patients and further evaluate possible reasons, provided that our findings can be validated in other sarcoma patient cohorts.

Patients with more than 5 years past diagnosis had lower chances of reporting financial toxicity compared to patients with 0– < 0.5 years past diagnosis. Sarcoma patients currently receiving treatment have been shown to report financial toxicity [25, 28]. Being currently under treatment might be related to more uncertainties regarding the future where financial aspects might play an important role. Also, high OOPPs might be related to financial toxicity during treatment. Although Germany has a universal health coverage, OOPPs during treatment and in aftercare cannot be neglected [14].

A limitation of our analysis is the cross-sectional design which does not allow causal pathways to be established. Additionally, financial difficulties were assessed using a single question scale, which might not cover all aspects related to financial toxicity in cancer patients [7]. Nevertheless, the scale used is part of an internationally validated and accepted questionnaire for measuring quality of life in cancer patients. Changes in the societal financial situation might also impact financial toxicity in patients. Since data was obtained in a relatively short time frame (09/2017 to 02/2019), no significant changes in the societal financial situation occurred during that time frame which could affect the results. Finally, it is also possible that the study population is not fully representative of all sarcoma patients in Germany since participants were mostly recruited from university hospitals or specialized centers. On the other hand, we did evaluate the question of financial toxicity in one of the largest sarcoma cohorts reported in the literature, covering all relevant histological subtypes and treatment groups. With a broad set of sociodemographic and clinical variables available, we were able to identify factors which might have an impact on the chance of reporting financial difficulties that were not addressed in other studies.

Conclusion

A high proportion of sarcoma patients in Germany report financial difficulties, compared to a general norm population. This impairment appears to be relevant and needs to be addressed by the involved stakeholders, especially since many of the factors associated with financial difficulties in our study were related to income and ability to work. Both treating physicians and patients should be aware of the involved risks and the options regarding the return to a working environment should be discussed with the patients at an early stage. Additional support and consulting opportunities, taking the experience of previous patients into consideration, should be readily available. Furthermore, we believe that policy changes regarding sick leave and the disability pension in Germany should be considered for reducing financial inequality among sarcoma patients.

Author contribution

M.Bu. wrote the article. M.E. analyzed the data. M.E., M.K.S., and L.H. developed questionnaires and study design. J.S. and M.K.S. developed the conception of the study and supervised with M.Bo. the work throughout the whole study. K.A. supervised the study from a patient’s perspective. K.T. edited language. M.E., M.Bu., K.T., and S.S. developed the statistical analysis plan for this paper. S.R., P.H., B.K., D.A., and M.K.S. were responsible for the recruitment of patients or recruited patients directly. All authors have revised the manuscript critically and approved the published version. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

Open Access funding enabled and organized by Projekt DEAL. The PROSa study was funded by the German Cancer Aid (No. 111713).

Data Availability

The data is not to be deposited but is available on request.

Code availability

Code is available upon request.

Declarations

Ethics approval

Ethics approval was obtained by the ethics committee of Technical University of Dresden (AZ: EK 1790422017) and the ethics committees of the participating centers.

Consent to participate

Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study.

Consent for publication

N/A.

Conflict of interest

M.Bu. reports personal fees from Lilly and Takeda outside the submitted work.

S.S. received lecture fees from Lilly, BMS, Boehringer-Ingelheim, and Pfizer, all outside of this work.

J.S. received consulting fees from Novartis, Sanofi, A.L.K, and Lilly, all outside of this work. D.A received lecture fees from Lilly and Implantcast, all outside of this work.

M.K.S. received research funding from PharmaMar and Novartis, all outside of this work. L.H. received fees from SERVIER, outside of this work.

M.E., B.K., K.A., M.Bo., P.H., K.T., and S.R. declare that no conflicts of interest exist.

Footnotes

Publisher's note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.van der Graaf WTA, Orbach D, Judson IR, Ferrari A. Soft tissue sarcomas in adolescents and young adults: a comparison with their paediatric and adult counterparts. Lancet Oncol. 2017;18(3):e166–e175. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(17)30099-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Stiller CA, Trama A, Serraino D, Rossi S, Navarro C, Chirlaque MD, et al. Descriptive epidemiology of sarcomas in Europe: report from the RARECARE project. Eur J Cancer. 2013;49(3):684–695. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2012.09.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.McDonough J, Eliott J, Neuhaus S, Reid J, Butow P. Health-related quality of life, psychosocial functioning, and unmet health needs in patients with sarcoma: a systematic review. Psychooncology. 2019;28(4):653–664. doi: 10.1002/pon.5007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Altice CK, Banegas MP, Tucker-Seeley RD, Yabroff KR. Financial hardships experienced by cancer survivors: a systematic review. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2017;109(2):djw205. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djw205. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Azzani M, Roslani AC, Su TT. The perceived cancer-related financial hardship among patients and their families: a systematic review. Support Care Cancer. 2015;23(3):889–898. doi: 10.1007/s00520-014-2474-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gordon LG, Merollini KMD, Lowe A, Chan RJ. A systematic review of financial toxicity among cancer survivors: we can’t pay the co-pay. Patient. 2017;10(3):295–309. doi: 10.1007/s40271-016-0204-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Witte J, Mehlis K, Surmann B, Lingnau R, Damm O, Greiner W, Winkler EC. Methods for measuring financial toxicity after cancer diagnosis and treatment: a systematic review and its implications. Ann Oncol. 2019;30(7):1061–1070. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdz140. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Fenn KM, Evans SB, McCorkle R, DiGiovanna MP, Pusztai L, Sanft T, et al. Impact of financial burden of cancer on survivors’ quality of life. J Oncol Pract. 2014;10(5):332–338. doi: 10.1200/JOP.2013.001322. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kale HP, Carroll NV. Self-reported financial burden of cancer care and its effect on physical and mental health-related quality of life among US cancer survivors. Cancer. 2016;122(8):283–289. doi: 10.1002/cncr.29808. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lathan CS, Cronin A, Tucker-Seeley R, Zafar SY, Ayanian JZ, Schrag D. Association of financial strain with symptom burden and quality of life for patients with lung or colorectal cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2016;34(15):1732–1740. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2015.63.2232. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Zafar SY, Peppercorn JM, Schrag D, Taylor DH, Goetzinger AM, Zhong X, et al. The financial toxicity of cancer treatment: a pilot study assessing out-of-pocket expenses and the insured cancer patient’s experience. Oncologist. 2013;18(4):381–390. doi: 10.1634/theoncologist.2012-0279. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ramsey SD, Bansal A, Fedorenko CR, Blough DK, Overstreet KA, Shankaran V, et al. Financial insolvency as a risk factor for early mortality among patients with cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2016;34(9):980–986. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2015.64.6620. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Barbaret C, Brosse C, Rhondali W, Ruer M, Monsarrat L, Michaud P, et al. Financial distress in patients with advanced cancer. PLoS One. 2017;12(5):e0176470. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0176470. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Buttner M, Konig HH, Lobner M, Briest S, Konnopka A, Dietz A, et al. Out-of-pocket-payments and the financial burden of 502 cancer patients of working age in Germany: results from a longitudinal study. Support Care Cancer. 2019;27(6):2221–2228. doi: 10.1007/s00520-018-4498-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Pearce A, Tomalin B, Kaambwa B, Horevoorts N, Duijts S, Mols F, et al. Financial toxicity is more than costs of care: the relationship between employment and financial toxicity in long-term cancer survivors. J Cancer Surviv. 2019;13(1):10–20. doi: 10.1007/s11764-018-0723-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Perrone F, Jommi C, Di Maio M, Gimigliano A, Gridelli C, Pignata S, et al. The association of financial difficulties with clinical outcomes in cancer patients: secondary analysis of 16 academic prospective clinical trials conducted in Italy. Ann Oncol. 2016;27(12):2224–2229. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdw433. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Weaver R, O’Connor M, Sobhi S, Carey Smith R, Halkett G. The unmet needs of patients with sarcoma. Psychooncology. 2020;29(7):1209–1216. doi: 10.1002/pon.5411. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Eichler M, Hentschel L, Richter S, Hohenberger P, Kasper B, Andreou D, et al. The health-related quality of life of sarcoma patients and survivors in Germany—cross-sectional results of a nationwide observational study (PROSa) Cancers (Basel) 2020;12(12):3590. doi: 10.3390/cancers12123590. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hagenaars A, de Vos K, Zaidi MA. Poverty statistics in the late 1980s: research based on micro-data. Luxembourg: Office for Official Publications of the European Communities; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Aaronson NK, Ahmedzai S, Bergman B, Bullinger M, Cull A, Duez NJ, et al. The European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer QLQ-C30: a quality-of-life instrument for use in international clinical trials in oncology. J Natl Cancer Inst. 1993;85(5):365–376. doi: 10.1093/jnci/85.5.365. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Fayers PM, Aaronson NK, Bjordal K, Groenvold M, Curran D, Bottomley A, on behalf of the EORTC Quality of Life Group . The EORTC QLQ-C30 scoring manual. 3. Brussels: European Organisation for Research and Treatment of Cancer; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Giesinger JM, Loth FLC, Aaronson NK, Arraras JI, Caocci G, Efficace F, et al. Thresholds for clinical importance were established to improve interpretation of the EORTC QLQ-C30 in clinical practice and research. J Clin Epidemiol. 2020;118:1–8. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2019.10.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Nolte S, Liegl G, Petersen MA, Aaronson NK, Costantini A, Fayers PM, et al. General population normative data for the EORTC QLQ-C30 health-related quality of life questionnaire based on 15,386 persons across 13 European countries, Canada and the Unites States. Eur J Cancer. 2019;107:153–163. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2018.11.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hudgens S, Forsythe A, Kontoudis I, D’Adamo D, Bird A, Gelderblom H. Evaluation of quality of life at progression in patients with soft tissue sarcoma. Sarcoma. 2017;2017:2372135. doi: 10.1155/2017/2372135. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Paredes T, Pereira M, Moreira H, Simoes MR, Canavarro MC. Quality of life of sarcoma patients from diagnosis to treatments: predictors and longitudinal trajectories. Eur J Oncol Nurs. 2011;15(5):492–499. doi: 10.1016/j.ejon.2011.01.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Podleska LE, Kaya N, Farzaliyev F, Pottgen C, Bauer S, Taeger G. Lower limb function and quality of life after ILP for soft-tissue sarcoma. World J Surg Oncol. 2017;15(1):84. doi: 10.1186/s12957-017-1150-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Reichardt P, Leahy M, Garcia Del Muro X, Ferrari S, Martin J, Gelderblom H, et al. Quality of life and utility in patients with metastatic soft tissue and bone sarcoma: the sarcoma treatment and burden of illness in North America and Europe (SABINE) study. Sarcoma. 2012;2012:740279. doi: 10.1155/2012/740279. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Srivastava A, Vischioni B, Fiore MR, Vitolo V, Fossati P, Iannalfi A, et al. Quality of life in patients with chordomas/chondrosarcomas during treatment with proton beam therapy. J Radiat Res. 2013;54 Suppl 1:i43–i48. doi: 10.1093/jrr/rrt057. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Longo CJ, Bereza BG. A comparative analysis of monthly out-of-pocket costs for patients with breast cancer as compared with other common cancers in Ontario Canada. Curr Oncol. 2011;18(1):e1–8. doi: 10.3747/co.v18i1.681. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Baili P, Di Salvo F, de Lorenzo F, Maietta F, Pinto C, Rizzotto V, et al. Out-of-pocket costs for cancer survivors between 5 and 10 years from diagnosis: an Italian population-based study. Support Care Cancer. 2016;24(5):2225–2233. doi: 10.1007/s00520-015-3019-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Céilleacher AO, Hanly P, Skally M, O’Leary E, O’Neill C, Fitzpatrick P, et al. Counting the cost of cancer: out-of-pocket payments made by colorectal cancer survivors. Support Care Cancer. 2017;25(9):2733–2741. doi: 10.1007/s00520-017-3683-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Mols F, Tomalin B, Pearce A, Kaambwa B, Koczwara B. Financial toxicity and employment status in cancer survivors. A systematic literature review. Support Care Cancer. 2020;28(12):5693–708. doi: 10.1007/s00520-020-05719-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Spelten ER, Sprangers MA, Verbeek JH. Factors reported to influence the return to work of cancer survivors: a literature review. Psychooncology. 2002;11(2):124–131. doi: 10.1002/pon.585. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Leuteritz K, Friedrich M, Sender A, Richter D, Mehnert-Theuerkauf A, Sauter S, Geue K. Return to work and employment situation of young adult cancer survivors: results from the adolescent and young adult-Leipzig study. J Adolesc Young Adult Oncol. 2021;10(2):226–233. doi: 10.1089/jayao.2020.0055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Zambrano SC, Kollar A, Bernhard J. Experiences of return to work after treatment for extremital soft tissue or bone sarcoma: between distraction and leaving the disease behind. Psychooncology. 2020;29(4):781–787. doi: 10.1002/pon.5349. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kwong TN, Furtado S, Gerrand C. What do we know about survivorship after treatment for extremity sarcoma? A systematic review. Eur J Surg Oncol. 2014;40(9):1109–1124. doi: 10.1016/j.ejso.2014.03.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Laros N, Sungu-Winkler KT, Gutermuth S, Wartenberg M, Hohenberger P, Seifart U, et al. Career and financial situation of patients diagnosed with soft tissue sarcomas. Oncol Res Treat. 2020;43(10):539–548. doi: 10.1159/000509518. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Hazell SZ, Fu W, Hu C, Voong KR, Lee B, Peterson V, et al. Financial toxicity in lung cancer: an assessment of magnitude, perception, and impact on quality of life. Ann Oncol. 2020;31(1):96–102. doi: 10.1016/j.annonc.2019.10.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.https://www.bundesgesundheitsministerium.de/krankengeld.html. last Access 19.01.2021

- 40.Lueckmann SL, Schumann N, Hoffmann L, Roick J, Kowalski C, Dragano N, et al. ‘It was a big monetary cut’-a qualitative study on financial toxicity analysing patients’ experiences with cancer costs in Germany. Health Soc Care Community. 2020;28(3):771–780. doi: 10.1111/hsc.12907. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Deutsche Rentenversicherung (2020) Statistik der deutschen Rentenversicherung – Rentenversicherung in Zahlen 2020

- 42.Zafar SY, McNeil RB, Thomas CM, Lathan CS, Ayanian JZ, Provenzale D. Population-based assessment of cancer survivors’ financial burden and quality of life: a prospective cohort study. J Oncol Pract. 2015;11(2):145–150. doi: 10.1200/JOP.2014.001542. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Walker MS, Wong W, Ravelo A, Miller PJE, Schwartzberg LS. Effectiveness outcomes and health related quality of life impact of disease progression in patients with advanced nonsquamous NSCLC treated in real-world community oncology settings: results from a prospective medical record registry study. Health Qual Life Outcomes. 2017;15(1):160. doi: 10.1186/s12955-017-0735-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Koskinen JP, Farkkila N, Sintonen H, Saarto T, Taari K, Roine RP. The association of financial difficulties and out-of-pocket payments with health-related quality of life among breast, prostate and colorectal cancer patients. Acta Oncol. 2019;58(7):1062–1068. doi: 10.1080/0284186X.2019.1592218. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The data is not to be deposited but is available on request.

Code is available upon request.