Abstract

Background:

Females with cystic fibrosis (CF) have been shown to have worse pulmonary exacerbation (PEx) related outcomes compared to males. However, it is unknown if sex differences in treatment patterns are contributing to these outcomes. Thus, we sought to explore sex differences in treatment patterns in the Standardized Treatment of Pulmonary Exacerbations (STOP) cohort.

Methods:

Data for 220 participants from the STOP cohort were analyzed. Multivariable regression models were used to assess if female sex was associated with duration of treatment with IV antibiotics and inpatient length of stay. Secondary outcomes included antibiotic selection, adjunctive therapies, mean FEV1pp and CFRSD-CRISS respiratory symptom scores at the four study assessments.

Results:

In our adjusted model, the average number of IV antibiotic treatment days was 13% higher in females compared to males (IRR 1.13, 95% CI=1.02,1.25; p=0.02). We found no sex differences in inpatient length of stay, number of IV antibiotics, antibiotic selection or initiation of adjunctive therapies. Overall, females had higher CFRSD-CRISS scores at the end of IV therapy indicating worse symptom severity (23.6 for females vs. 18.5 for males, p=0.03).

Conclusions:

Despite females having a longer treatment duration, our findings demonstrate that males and females are receiving similar treatments which suggest that the outcome disparities in females with CF may not be due to failure to provide the same level of care. Further research dedicated to sex differences in CF is necessary to understand why clinical outcomes differ between males and females.

1. Introduction

Pulmonary exacerbations (PEx), manifested by acute worsening of pulmonary symptoms and/or a decrease in lung function warranting acute antibiotic treatment, are common occurrences in people with cystic fibrosis (CF) and are associated with increased morbidity and mortality.1–6 Numerous epidemiologic studies have demonstrated significant sex differences related to PEx outcomes. Females have more PEx per year7, are less likely to recover to baseline lung function following treatment for a PEx8, and have a significantly higher rate of PEx post-puberty compared to males9.

While researchers have focused on innate sex differences including airway anatomy, pathogen acquisition, and sex-hormone mediated effects as biologic mechanisms leading to poor outcomes seen in females with CF,10–16 significant knowledge gaps remain. Wide variability exists in treatment of PEx given lack of standardized guidelines regarding antibiotic duration, adjunctive therapies as well as preferred treatment setting.17–19 Sex differences in treatment for PEx have yet to be evaluated in people with CF, and understanding if there are potential sex differences in treatment that may be contributing to the disproportionate outcomes seen in females with CF could result in future therapeutic interventions. Thus, we utilized the Standardized Treatment of Pulmonary Exacerbations (STOP) study, a national multicenter cohort study with detailed treatment and clinical information on people with CF ≥ 12 years of age admitted to the hospital and treated with intravenous (IV) antibiotics 20–21 to evaluate whether antibiotic duration and inpatient length of stay differed between males and females. We also looked at sex differences in antibiotic selection, initiation of adjunctive therapies, and health outcomes including mean forced expiratory volume in one second percent predicted (FEV1pp) and CF Respiratory Symptom Diary and Chronic Respiratory Infection Symptom Scores (CFRSD-CRISS).22–23

2. Methods

2.1. Study population

The STOP study was a prospective cohort designed to identify clinical endpoints for future PEx studies and was conducted at 11 U.S. CF centers from January 2014 to January 2015 (clinicaltrials.gov: NCT02109822). Complete description of the study design, including inclusion criteria and procedures have been previously described.20–21 Briefly, a total of 220 participants ≥ 12 years of age hospitalized for a PEx and treated with IV antibiotics were enrolled in the study. Given the observational nature of the study, there was no intervention with regards to clinical care, and treatment was left to the discretion of the provider. The parent STOP study was approved by each of the participating center’s Institutional Review Board, and all participants or guardians provided informed consent at the time of enrollment. This current study was deemed exempt by the Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine Institutional Review Board (IRB00164692).

2.2. Study Variables

Baseline demographic and clinical characteristics were collected at enrollment in the parent STOP study. The highest FEV1pp within six months prior to study enrollment was collected from the Cystic Fibrosis Foundation Patient Registry (CFFPR) and was defined as baseline lung function for this study.

Antibiotic selection, duration of IV antibiotic therapy, and inpatient length of stay was determined by each participant’s treating provider. Adjunctive therapy defined as inhaled or oral antibiotics, as well as corticosteroids was also reported. Four assessments were conducted during the parent study, timed at study enrollment, day 7 of IV therapy, end of IV therapy, and 28 days after the start of IV therapy. Spirometry and respiratory symptoms were measured at each assessment. The Global Lung Initiative equations were utilized to calculate FEV1pp.24–25 Respiratory symptoms were ascertained using the CFRSD-CRISS, which is a validated patient reported outcome tool in people with CF ≥ 12 years of age. Scores range from 0–100 with higher scores indicating worse symptom severity, and a change in score of 11 units is the reported minimal clinically important difference (MCID).22–23

The primary exposure for our study was sex. The primary outcomes of interest were duration of IV antibiotic treatment and inpatient length of stay. Secondary outcomes included antibiotic selection, initiation of adjunctive therapies, mean FEV1pp and CFRSD-CRISS scores obtained during the four study assessments.

2.3. Statistical Analysis

Demographic and clinical characteristics were compared between males and females using chi-squared or Fisher’s exact tests and Student t-tests or Wilcoxon rank-sum tests for categorical and continuous variables, respectively. Distributions of IV antibiotic type, number of IV antibiotics, adjunctive therapies and distributions of FEV1pp were compared in a similar fashion. CFRSD-CRISS scores were analyzed as continuous variable as well as above or below the MCID. Unadjusted and multivariable negative binomial regression models were used to evaluate the association between sex and duration of IV antibiotic treatment and duration of hospitalization for the entire cohort. Multivariable models contained factors identified a priori and included age at enrollment, BMI, CFRD, F508del mutation category, pancreatic enzyme use, Pseudomonas aeruginosa infection and baseline lung function. Results of regression models are presented as incidence rate ratios (IRR) with corresponding 95% confidence intervals (CI). Subgroup analyses were performed to evaluate each outcome separately in pediatric (<18 years) and adult (≥18 years of age) participants using the previously described methods. All analyses were performed using Stata Version 15 (StataCorp, College Station, TX) with statistical significance for all tests defined as a p value < 0.05.

3. Results

3.1. Participant Characteristics

A total of 220 individuals were enrolled in the STOP study, of which 124 (56.4%) were female and 96 (43.6%) were male. There were 42 (19.1%) pediatric participants in the cohort. Demographic and clinical characteristics at study entry were similar between females and males, with no significant sex differences noted for a range of variables as presented in Table 1. P. aeruginosa was the most common respiratory pathogen isolated from 71.3% of participants in the six months prior to enrollment. Mean baseline FEV1pp was 60.2% predicted (SD=22.8).

Table 1.

Participant Demographic and Clinical Characteristics

| N | Overall (n=220) | Females (n=124) | Males (n=96) | p Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||

| Demographics | ||||

|

| ||||

| Age (years), n(%) | 26.3 (9.5) | 25.6 (9.4) | 27.1 (9.6) | 0.29 |

| 12 to < 18 years of age | 42 (19.1) | 26 (21.0) | 16 (16.7) | 0.42 |

| ≥ 18 years of age | 178 (80.9) | 98 (79.0) | 80 (83.3) | |

| Race, n(%) | ||||

| Caucasian | 198 (90.0) | 111 (89.5) | 87 (90.6) | 0.66 |

| F508del mutation category, n(%) | 0.19 | |||

| F508del homozygous | 121 (55.0) | 73 (58.9) | 48 (50.0) | |

| F508del heterozygous | 82 (37.3) | 45 (36.3) | 37 (38.5) | |

| Other | 17 (6.6) | 6 (4.8) | 11 (11.5) | |

| Body mass index kg/m2 | 20.6 (17.7) | 20.7 (3.64) | 20.6(3.98) | 0.90 |

| Pancreatic enzyme use, n(%) | 196 (89.5) | 109 (87.9) | 87 (91.6) | 0.38 |

| CFRD, n(%)† | 86 (39.2) | 43 (34.7) | 43 (45.3) | 0.11 |

|

| ||||

| Respiratory Microbiology, n(%) | ||||

|

| ||||

| P. aeruginosa | 154 (71.3) | 88 (70.1) | 66 (71.7) | 0.90 |

| P. aeruginosa (mucoid) | 121 (56.0) | 73 (58.7) | 48 (52.2) | 0.33 |

| MSSA | 78 (36.1) | 41 (33.1) | 37 (40.2) | 0.28 |

| MRSA | 84 (38.9) | 52 (41.9) | 32 (34.8) | 0.29 |

| Stenotrophomonas maltophilia | 31 (14.4) | 18 (14.5) | 13 (14.1) | 0.94 |

| Achromobacter xylosoxidans | 20 (9.3) | 13 (10.5) | 7 (7.61) | 0.47 |

| Burkholderia species | 6 (2.8) | 5 (4.3) | 1 (1.1) | 0.24 |

| Aspergillus | 47 (21.8) | 27(21.8) | 20 (21.7) | 0.99 |

|

| ||||

| Lung Function | ||||

|

| ||||

| FEV1pp (baseline) † | 60.2 (22.8) | 61.8 (22.3) | 59.0 (23.7) | 0.40 |

| 12 to <18 years of age | 78.7 (3.18) | 77.7 (4.3) | 80.3 (4.6) | 0.69 |

| ≥18 years of age | 55.8 (1.7) | 57.2 (2.1) | 53.9 (2.7) | 0.33 |

Values presented as mean (S.D) unless indicated otherwise

Includes values for 200 of the study participants obtained at baseline (highest FEV1pp 6 months prior to hospital admission)

CFTR: cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator; CFRD: cystic fibrosis related diabetes; P. aeruginosa: Pseudomonas aeruginosa; MSSA: Methicillin-sensitive Staphylococcus aureus; MRSA: Methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus

3.2. Treatment Duration and Inpatient Length of Stay

Table 2 presents the mean duration of IV antibiotic therapy and inpatient length of stay by sex and by age groups. The overall mean duration of IV antibiotic therapy was 15.9 days (SD=6.0); the mean duration of IV therapy being highest amongst adult females at 16.6 days (SD=6.5) compared to 14.9 days (SD=5.1) for adult males (p=0.05). There were no significant differences for mean inpatient length of stay between sex for the overall cohort or between age groups.

Table 2.

Treatment Duration and Inpatient Length of Stay by Sex and Age

| Overall | Females | Males | p Value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||

| IV Antibiotic Duration (days) | ||||

|

| ||||

| Overall (n=189) | 15.9 (6.0) | 16.6 (6.5) | 14.9 (5.1) | 0.05 |

| 12 to < 18 years of age (n=36) | 14.5 (4.8) | 15.4 (5.4) | 13.1 (3.5) | 0.14 |

| ≥ 18 years of age (n=153) | 16.2 (6.2) | 16.9 (6.8) | 15.3 (5.3) | 0.10 |

|

| ||||

| Inpatient Length of Stay (days) | ||||

|

| ||||

| Overall (n=216) | 11.4 (5.7) | 11.5 (6.3) | 11.2 (4.8) | 0.69 |

| 12 to < 18 years of age (n=41) | 13.0 (5.9) | 12.7 (6.3) | 13.5 (5.5) | 0.70 |

| ≥ 18 years of age (n=175) | 10.9 (5.5) | 11.1 (6.3) | 10.7 (4.5) | 0.63 |

Values presented as mean (S.D) unless indicated otherwise

Table 3 presents the results of unadjusted and adjusted negative binomial regression models evaluating the association of sex with number of treatment days with IV antibiotics and hospitalization duration. After adjustment for individual-level clinical characteristics, the average number of IV antibiotic treatment days was 13% higher in females compared to males (IRR 1.13, 95% CI=1.02, 1.25; p=0.02). By subgroups, the average number of IV antibiotic treatment days was 15% higher in adult females compared to adult males (IRR 1.15, 95% CI= 1.02, 1.29; p=0.02), and was 26% higher in pediatric females compared to pediatric males, although this association did not reach statistical significance (IRR 1.26, 95% CI= 1.00, 1.58; p=0.05). Female sex was not significantly associated with a longer inpatient length of stay (IRR 1.03, 95% CI= 0.89, 1.18; p=0.70) overall or within the adult and pediatric subgroups.

Table 3:

Association of Female Sex with IV Antibiotic Duration and Inpatient Length of Stay

| Unadjusted IRR (95% CI) | Adjusted IRR (95% CI)‡ | |

|---|---|---|

| IV Antibiotic Duration | ||

| Female (Overall cohort) | 1.12 (1.01 – 1.23) * | 1.13 (1.02 – 1.25) * |

| Female (< 18 years) | 1.17 (0.95 – 1.45) | 1.26 (1.00 – 1.58) |

| Female (≥ 18 years) | 1.10 (0.99 –1.23) | 1.15 (1.02 – 1.29) * |

| Inpatient Length of Stay | ||

| Female (Overall cohort) | 1.03 (0.90 – 1.17) | 1.03 (0.89 – 1.18) |

| Female (< 18 years) | 0.95 (0.72 – 1.24) | 1.14 (0.91 – 1.43) |

| Female (≥ 18 years) | 1.04 (0.89 – 1.20) | 1.07 (0.91 – 1.27) |

Models were adjusted for age, BMI, F508del mutation category (F508del heterozygous, F508del homozygous, or other/unknown), CF related diabetes, pancreatic insufficiency, Pseudomonas aeruginosa culture, and highest FEV1% predicted in the six months prior to enrollment.

Indicates a statistically significant finding (p< 0.05)

3.3. Treatment Selection

The most commonly prescribed antibiotics for PEx are presented in the supplement (Table S1). Tobramycin (63.2%) and Meropenem (29.6%) were the two most commonly used antibiotics. There were no significant differences in prescribed antibiotics between sex overall or in either age group. Similarly, there were no differences in the number of IV antibiotics prescribed (Table S2); 51.4% of individuals were treated with 2 IV antibiotics and an additional 33.2% received treatment with 3 or more IV antibiotics. Table S3 presents the distribution of prescribed adjunctive therapies which were similar between males and females. In addition to IV antibiotics, 9.1% of participants were started on at least one inhaled antibiotic and 24.5% were started on at least one oral antibiotic.

3.4. Health Outcomes

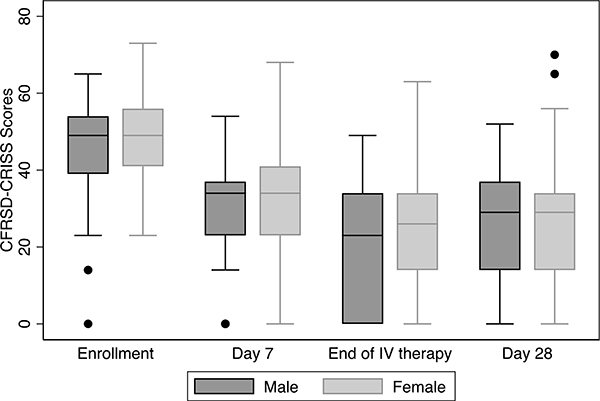

Spirometry was obtained at enrollment for 203 individuals (92.2%) within three days of hospitalization and mean FEV1pp was similar for females (52.7%; SD=20.9) and males (49.0%; SD=22.4). Although females had a higher FEV1pp at each study visit (Figure 1), there were no significant differences in FEV1pp between males and females, overall or by age group, at each visit (Table S4). While males had a larger decline in FEV1pp from baseline to study enrollment compared to females, this magnitude of difference was not sustained over study assessments. The mean CFRSD-CRISS scores were similar for males and females at study enrollment (Table S5). However, females had a statistically significant higher CFRSD-CRISS score at the end of IV therapy compared to males indicating worse symptom severity (23.6 for females vs 18.5 for males, p=0.03), and these differences were more pronounced in the pediatric cohort (21.3 for females vs. 9.9 for males, p=0.04) although the differences were not sustained at the final study assessment (Figure 2). We further looked at the proportion of males and females meeting the MCID for CFRSD-CRISS across the study assessments. Among the cohort, 80.6% of females and 84.6% of males met the MCID at the end of IV treatment, and there was no significant difference overall or by age groups (Table S6).

Figure 1. FEV1pp by sex at each study assessment.

FEV1pp at study enrollment, Day 7 of IV therapy, End of IV therapy and 28 days after IV therapy. The boxes represent the middle 50% of patients; the whiskers include all participants in each group. The horizontal line within the box represents the median FEV1pp. The x-axis represents the four study assessments.

Figure 2. CFRSD-CRISS scores by sex at each study assessment.

CFRSD-CRISS scores at study enrollment, Day 7 of IV therapy, End of IV therapy and 28 days after IV therapy. The boxes represent the middle 50% of patients; the whiskers include all participants in each group. The horizontal line within the box represents the median CFRSD-CRISS score. The x-axis represents the four study assessments. The black dots represent outliers.

4. Discussion

In this large, multicenter cohort of people with CF hospitalized and treated with IV antibiotics for a PEx, we found that female sex was associated with a statistically significant higher rate of treatment days with IV antibiotics. Although baseline demographic and clinical characteristics were similar between sexes, females were treated 1.6 days longer on average compared to males. Despite longer treatment duration, we found no sex differences in regards to inpatient length of stay, antibiotic selection, number of IV antibiotics used or initiation of adjunctive therapies. However, we found that females reported significantly higher respiratory symptom scores, indicating worse severity, at the end of IV therapy compared to males although these differences were not sustained at the 28-day evaluation.

While it is widely known that females with CF have worse outcomes compared to males, our study extends on previous observations by evaluating potential sex differences in the treatment of PEx, which has not been previously explored in CF. We demonstrate that males and females with CF are receiving similar treatments which suggest the outcome disparities observed in females with CF may not be due to failure to provide the same level of care. Providing clinical outcomes, while replicating previous research, provides context for interpreting the implications of the treatments males and females received which adds to our knowledge of PEX treatment between sexes.

Given the observational nature of the parent STOP study, providers were allowed to select antibiotic therapy and duration per their discretion. We realize that providers routinely alter therapy based on numerous factors including health outcomes, microbiology results and a patient’s prior response to PEx treatment which could have impacted our findings. Regarding health outcomes in this study, we looked at mean FEV1pp as well as mean CFRSD-CRISS scores across the four study assessments. While we found no significant differences in mean FEV1pp across the study assessments, we found that pediatric males had a statistically significant lower CFRSD-CRISS score at the end of IV therapy suggesting they had a better treatment response compared to pediatric females and adults although this difference was not sustained at the 28-day evaluation. It is not clear if this is a true clinical difference or measurement error. We further looked at the proportion of participants who met the MCID at the study visits after IV therapy was initiated. Given that there were similar proportions of females and males that met the MCID, we could infer that the longer treatment duration females received may have been clinically necessary. Thus, we propose future longitudinal studies continue to collect symptom data to determine if females take longer to reach symptomatic recovery or if they reach it at the same time but get more treatment. Additionally, we found no significant differences in baseline microbiology profile between sexes although microbiology susceptibility and resistance patterns were not known and would be important to compare. Furthermore, it is unknown whether the decision of when and how to treat PEx differs between male and female providers. While this factor is beyond the scope of this study, it is an interesting point for future investigation.

There are several limitations to our current study. There is no standard definition of PEx allowing for variability in clinician diagnosis.17,20–21 A common approach in clinical studies and the approach used in the parent STOP study was to define a PEx as a worsening of respiratory symptoms and/or lung function coupled with the decision to hospitalize and treat with IV antibiotics, suggesting that the study participants may represent a group of individuals with more severe PEx and/or more advanced lung disease. However, this definition does not capture those people with CF who may have had milder symptoms and/or who would be treated with oral antibiotics, and we recognize that our results may not be generalizable to all PEx. Furthermore, the parent STOP study was conducted at 11 U.S. CF care centers where the treating providers were aware of participant enrollment into the study. Thus, there may be a difference between the practice patterns at these sites who are interested in PEx outcomes, and providers may have changed practice patterns knowing that treatments were being observed. We were also limited by a small pediatric cohort, which appeared to account for some of findings, particularly the differences in mean CFRSD-CRISS scores. Lastly, researchers have demonstrated that female sex has been associated with lower general health perceptions in CF26 suggesting potential sex differences in how females and males perceive and report symptoms. Currently, it is not known how this impacts treatment decisions, but would be important to assess in future studies

It is also important to note that the STOP study was conducted prior to widespread use of cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator (CFTR) modulator therapies. Recent phase 3 clinical trials of Elexacaftor-Tezacaftor-Ivacaftor demonstrated robust improvements in FEV1pp27–28 as well as a 63% lower rate of PEx over a 24-week study period.27 With FDA approval in 2019 for people with CF and a single allele of F508del mutation, approximately 90% of the CF population is now eligible for therapy. Given the significant improvements seen with this therapy, we anticipate that the PEx rates seen in people with CF will decrease. While we do not know if sex differences exist in regards to treatment response to Elexacaftor-Tezacaftor-Ivacaftor, a recent study demonstrated that females with at least one G551D mutation on Ivacaftor had a greater reduction in PEx rate suggesting sex differences in the differential response profile to CFTR modulator therapy.29

In summary, we found that female sex is associated with a higher rate of treatment days with IV antibiotics, yet females had less symptomatic recovery at the end of IV therapy despite receiving similar PEx treatment. While we found no evidence of a treatment disparity, our findings support the need for dedicated sex differences research in people with CF. As the CF community moves towards personalized medicine, we need to better understand why females with CF take longer to see improvement. Incorporating sex into the study design as well as analyses in future CF clinical studies is clearly warranted.

Supplementary Material

Highlights.

Females with CF have been reported to have worse pulmonary exacerbation (PEx) related outcomes compared to males.

Females were treated with IV antibiotics 1.6 days longer on average compared to males.

We found no sex differences in regards to inpatient length of stay, IV antibiotic selections or adjunctive therapies.

Females reported worse respiratory symptoms at the end of IV therapy despite receiving similar PEx treatment

Future sex differences research in people with CF is needed

Acknowledgements:

We thank the STOP program study investigators (Patrick Flume, Christopher Goss, Sonya Heltshe, Donald Sanders, Donald VanDevanter, and Natalie West) for their support of this study.

We thank the CF Therapeutics Development Network (Sonya Heltshe and Michelle Skalland) for their coordinated efforts with the request and transfer of STOP study data. We would like to thank the patients, families, care providers, and clinic coordinators at CF Centers in STOP and throughout the CFF Therapeutic Development Network for their contributions to the study. Finally, we would like to thank all the participating sites, investigators, and research coordinators.

Funding Statement: This work was supported by the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute under F32HL143833 (KM), and Cystic Fibrosis Foundation Therapeutics, Inc. MONTEM18A0-D3 (KM), WEST17Y5 (NEW), WEST15A0 (NEW) and MERLO18Y7 (CAM, NEW, KJP).

Funding:

This work was supported by the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute under F32HL143833 (KM) and Cystic Fibrosis Foundation MONTEM18A0-D3 (KM), WEST17Y5 (NEW), WEST15A0 (NEW) and MERLO18Y7 (CAM, NEW).

Abbreviations:

- BMI

Body-mass index

- CF

Cystic Fibrosis

- CFFPR

Cystic Fibrosis Foundation Patient Registry

- CFRD

Cystic Fibrosis Related Diabetes

- CFRSD-CRISS

CF Respiratory Symptom Diary and Chronic Respiratory Infection Symptom Score

- CFTR

Cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator

- FEV1

Forced expiratory volume at 1 second

- IV

Intravenous

- MCID

Minimal clinically important difference

- PEx

Pulmonary Exacerbation

- STOP

Standardized Treatment of Pulmonary Exacerbations

Footnotes

Declaration of interests

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

Financial/nonfinancial disclosures:

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this manuscript.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References:

- 1.de Boer K, Vandemheen KL, Tullis E, Doucette S, Fergusson D, Freitag A, Paterson N, Jackson M, Lougheed MD, Kumar V, Aaron SD. Exacerbation frequency and clinical outcomes in adult patients with cystic fibrosis. Thorax. 2011;66(8):680–685. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Konstan MW, Wagener JS, VanDevanter DR, Pasta DJ, Yegin A, Rasouliyan L, Morgan WJ. Risk factors for rate of decline in FEV1 in adults with cystic fibrosis. Journal of Cystic Fibrosis. 2012;11(5):405–411. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wagener JS, Rasouliyan L, VanDevanter DR, Pasta DJ, Regelmann WE, Morgan WJ, Konstan MW, Investigators and Coordinators of the Epidemiologic Study of Cystic Fibrosis. Oral, inhaled, and intravenous antibiotic choice for treating pulmonary exacerbations in cystic fibrosis. PediatrPulmonol. 2013;48(7):666–673. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sanders DB, Hoffman LR, Emerson J, Gibson RL, Rosenfeld M, Redding GJ, Goss CH. Return of FEV1 after pulmonary exacerbation in children with cystic fibrosis. PediatrPulmonol. 2010;45(2):127–134. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Liou TG, Adler FR, Fitzsimmons SC, Cahill BC, Hibbs JR, Marshall BC. Predictive 5-year survivorship model of cystic fibrosis. AmJEpidemiol. 2001;153(4):345–352. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Britto MT, Kotagal UR, Hornung RW, Atherton HD, Tsevat J, Wilmott RW. Impact of recent pulmonary exacerbations on quality of life in patients with cystic fibrosis. Chest. January 2002; 12(1):64–72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Harness-Brumley CL, Elliott AC, Rosenbluth DB, Raghavan D, Jain R. Gender differences in outcomes of patients with cystic fibrosis. J Womens Health. 2014;23(12):1012–1020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sanders DB, Bittner RCL, Rosenfeld M, Hoffman LR, Redding GJ, Goss CH. Failure to Recover to Baseline Pulmonary Function after Cystic Fibrosis Pulmonary Exacerbation. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2010; 182: 627–632. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sutton S, Rosenbluth D, Rahhavan D, Zheng J, Jain R. Effects of puberty on cystic fibrosis related pulmonary exacerbations in women versus men. Pediatric Pulmonol. 2014; 49(1):28–35. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Carey MA, Card JW, Voltz JW, et al. It’s all about sex: gender, lung development and lung disease. Trends Endocrinol Metab. 2007; 18: 308–313. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Liptzin DR, Landau LI, Taussig LM. Sex and the lung: Observations, hypotheses, and future directions. Pediatr Pulmonol. 2015. December;50(12):1159–69. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Li Z, Kosorok MR, Farrell PM, et al. Longitudinal Development of Mucoid Pseudomonas aeruginosa Infection and Lung Disease Progression in Children With Cystic Fibrosis. JAMA. 2005;293(5):581–588. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Demko CA, Byard PJ, Davis PB. Gender differences in cystic fibrosis: Pseudomonas aeruginosa infection. J Clin Epidemiol 1995;48:1041–1049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Chotirmall SH, Smith SG, Gunaratnam C, Cosgrove S, Dimitrov BD, O’Neill SJ, Harvey BJ, Greene CM, McElvaney NG. Effect of Estrogen on Pseudomonas Mucoidy and Exacerbations in Cystic Fibrosis. New England Journal of Medicine. 2012;366(21):1978–1986. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Coakley RD, Sun H, Clunes LA, Rasmussen JE, Stackhouse JR, Okada SF, Fricks I, Young SL, Tarran R. 17beta-Estradiol inhibits Ca2+-dependent homeostasis of airway surface liquid volume in human cystic fibrosis airway epithelia. J Clin Invest. 2008;118(12):4025–4035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Shaffer L, Abid S, Jain R. Evaluation of Dehydroepiandrosterone Sulfate (DHEAS) Levels in Cystic Fibrosis [Abstract]. American Thoracic Society International Conference 2019.

- 17.Flume PA, Mogayzel PJ, Robinson KA, Goss CH, Rosenblatt RL, Kuhn RJ, et al. Cystic fibrosis pulmonary guidelines: treatment of pulmonary exacerbations. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2009. November 1;180(9):802–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Collaco JM, Green DM, Cutting GR, Naughton KM, Mogayzel PJ. Location and duration of treatment of cystic fibrosis respiratory exacerbations do not affect outcomes. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2010. November 1;182(9):1137–43. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kraynack NC, Gothard MD, Falletta LM, McBride JT. Approach to treating cystic fibrosis pulmonary exacerbations varies widely across US CF care centers. Pediatr Pulmonol. 2011. September;46(9):870–81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Sanders DB, Solomon GM, Beckett VV, West NE, Daines CL, Heltshe SL, VanDevanter DR, Spahr JE, Gibson RL, Nick JA, Marshall BC, Flume PA, Goss CH, STOP Study Group. Standardized Treatment of Pulmonary Exacerbations (STOP) study: Observations at the initiation of intravenous antibiotics for cystic fibrosis pulmonary exacerbations. J Cyst Fibros. 2017. September;16(5):592–599. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.West NE, Beckett VV, Jain R, Sanders DB, Nick JA, Heltshe SL, Dasenbrook EC, VanDevanter DR, Solomon GM, Goss CH, Flume PA, STOP investigators. Standardized Treatment of Pulmonary Exacerbations (STOP) study: Physician treatment practices and outcomes for individuals with cystic fibrosis with pulmonary Exacerbations. J Cyst Fibros. 2017. September;16(5):600–606. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Goss CH, Edwards TC, Ramsey BW, Aitken ML, Patrick DL. Patient-reported respiratory symptoms in cystic fibrosis. JCyst Fibros. 2009;8(4):245–252. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Goss CH, Caldwell E, Gries K, Leidy N, Edwards T, Flume PA, Marshall BC, Ramsey BW, Patrick DL. Validation of a novel patient-reported respiratory symptoms instrument in cystic fibrosis: CFRSD-CRISS. Pediatr Pulmonol; 2013:A251. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Miller MR, Hankinson J, Brusasco V, Burgos F, Casaburi R, Coates A, et al. Standaridsation of spirometry. Eur Respir J. 2005; 26(2):319–338. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Quanjer PH, Stanojevic S, Cole TJ, Baur X, Hall GL, Culver BH, et al. ERS Global Lung Initiative. Multi-ethnic reference values for spirometry for the 3–95-yr age range: the global lung function 2012 equations. Eur Respir J. 2012; 40(6):1324–1343. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Arrington-Sanders R, Yi MS, Tsevat J. et al. Gender differences in health-related quality of life of adolescents with cystic fibrosis. Health Qual Life Outcomes. 2006. January 24;4:5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Middleton PG, Mall MA, Dřevínek P, Lands LC, McKone EF, Polineni D, Ramsey BW, Taylor-Cousar JL, Tullis E, Vermeulen F, Marigowda G, McKee CM, Moskowitz SM, Nair N, Savage J, Simard C, Tian S, Waltz D, Xuan F, Rowe SM, Jain R, VX17–445-102 Study Group. Elexacaftor-Tezacaftor-Ivacaftor for Cystic Fibrosis with a Single Phe508del Allele. N Engl J Med. 2019;381(19):1809–1819. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Heijerman HGM, McKone EF, Downey DG, Van Braeckel E, Rowe SM, Tullis E, Mall MA, Welter JJ, Ramsey BW, McKee CM, Marigowda G, Moskowitz SM, Waltz D, Sosnay PR, Simard C, Ahluwalia N, Xuan F, Zhang Y, Taylor-Cousar JL, McCoy KS, VX17–445-103 Trial Group. Efficacy and safety of the elexacaftor plus tezacaftor plus ivacaftor combination regimen in people with cystic fibrosis homozygous for the F508del mutation: a double-blind, randomised, phase 3 trial. Lancet. 2019;394(10212):1940–1948. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Secunda KE, Guimbellot JS, Jovanovic B, Heltshe SL, Sagel SD, Rowe SM, Jain M. Females with Cystic Fibrosis Demonstrate a Differential Response Profile to Ivacaftor Compared with Males. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2020;201(8):996–998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.