Abstract

Retroviruses, such as human immunodeficiency virus, that infect nondividing cells generate integration precursors that must cross the nuclear envelope to reach the host genome. As a model for retroviruses, we investigated the nuclear entry of Tf1, a long-terminal-repeat-containing retrotransposon of the fission yeast Schizosaccharomyces pombe. Because the nuclear envelope of yeasts remains intact throughout the cell cycle, components of Tf1 must be transported through the envelope before integration can occur. The nuclear localization of the Gag protein of Tf1 is different from that of other proteins tested in that it has a specific requirement for the FXFG nuclear pore factor, Nup124p. Using extensive mutagenesis, we found that Gag contained three nuclear localization signals (NLSs) which, when included individually in a heterologous protein, were sufficient to direct nuclear import. In the context of the intact transposon, mutations in the NLS that mapped to the first 10 amino acid residues of Gag significantly impaired Tf1 retrotransposition and abolished nuclear localization of Gag. Interestingly, this NLS activity in the heterologous protein was specifically dependent upon the presence of Nup124p. Deletion analysis of heterologous proteins revealed the surprising result that the residues in Gag with the NLS activity were independent from the residues that conveyed the requirement for Nup124p. In fact, a fragment of Gag that lacked NLS activity, residues 10 to 30, when fused to a heterologous protein, was sufficient to cause the classical NLS of simian virus 40 to require Nup124p for nuclear import. Within the context of the current understanding of nuclear import, these results represent the novel case of a short amino acid sequence that specifies the need for a particular nuclear pore complex protein.

Many viruses depend on components of the nucleus to complete replication, and thus, at some stage, most viral genomes must enter the nucleus. Although several viruses are known to access the nucleus through the nuclear pores, little is known about the mechanisms responsible for viral transport. The nuclear pore complex (NPC) is an ∼125-MDa structure, and in Saccharomyces cerevisiae, it has been estimated to contain approximately 30 different polypeptides (41, 44, 52). Several possible mechanisms for nuclear entry have been proposed. Viral particles could enter the nucleus intact, as is thought to be true of simian virus 40 (SV40) virions (37, 51). However, the sizes of virion or capsid particles are estimated to range from 26 to 125 nm and thus seem too large for most to be transported through the NPC (25). Maximal pore size estimates range from 9 to 26 nm (for reviews, see references 18 and 46). Alternatively, viral particles might enter the nucleus by means of a conformational change allowing the passage through nuclear pores. Another formal possibility is that virions dock at the nuclear pores and inject their contents into the nucleus, similar to what has been proposed for adenovirus (19). A more likely possibility for long-terminal-repeat (LTR)-containing retroelements is that a subassembly of the particle, which is called the preintegration complex (PIC), is transported into the nucleus by host cell machinery.

We study the nuclear entry of Tf1, an LTR-containing retrotransposon that propagates within the fission yeast Schizosaccharomyces pombe. The propagation of Tf1 requires many of the same processes used by retroviruses. Tf1 has coding sequences for Gag, protease (PR), reverse transcriptase (RT), and integrase (IN) proteins (30, 32). Once a full-length transcript of an LTR retroelement is produced and translated, the Gag, PR, RT, and IN proteins assemble with copies of the RNA to form virus or virus-like particles. RT converts the RNA into full-length double-stranded cDNA that is subsequently transported into the nucleus with IN. The cDNA is then inserted by IN into target sites in the host genome (4). The principal difference between retroviruses and LTR retrotransposons is that the viruses can escape the host cell and infect new cells.

In vivo assays for transposition demonstrate that Tf1 is highly active and generates transposition frequencies varying from 2 to 20% (31). Results of sucrose gradient sedimentation revealed that Tf1 Gag, IN, Tf1 mRNA, and reverse transcription products all assemble into virus-like particles (VLPs) that contain a 26-fold molar excess of Gag relative to IN (2, 28, 31).

The question of how Tf1 enters the nucleus is especially interesting because in yeasts the nuclear envelope (NE) does not break down during mitosis (26). For the integration of Tf1 to occur, the VLP or a PIC containing IN and cDNA must be transported across the nuclear membrane and into the nucleus. In higher eukaryotic cells, the nuclear envelope can also act as an obstacle of virus import that must be overcome. Lentiviruses, such as human immunodeficiency virus type 1 (HIV-1) and visna virus, are able to infect cells that have an intact NE by transporting large PICs through nuclear pores (7, 20, 33, 38, 50). In the case of other retroviruses, such as murine leukemia virus, the breakdown of the NE during cell division allows the PIC to interact with the host genome (42). However, avian sarcoma virus (ASV) does require nuclear import for efficient propagation (27).

Our previous studies of Tf1 showed that the Gag protein is localized in the nucleus (3, 8). As the result of a genetic screen, we identified Nup124p as a protein that is required for transposition and that a mutation in Nup124p caused a substantial defect in the nuclear import of Gag (3). Our studies of immunofluorescence and immunoelectron microscopies demonstrated that the Nup124p protein is a component of the NPC (3). We also showed that Nup124p possesses a specialized activity that is specifically required for the nuclear localization of transposon material and not the other cargos that were tested (3). It is indeed surprising that a strain containing a deletion of nup124 is defective for Tf1 transposition but nevertheless grows with wild-type rates (3).

In this report, we demonstrated that the Gag protein of Tf1 possessed sequences that were sufficient to cause the nuclear localization of fusion proteins. Mutations in a nuclear localization signal (NLS) in the N terminus of Gag caused a significant defect in transposition as well as the nuclear import of Gag and the Tf1 cDNA. Interestingly, the NLS activity that we identified in the N-terminal domain of Gag was sufficient when fused to GFP-LacZ to cause import into the nucleus that depended on the nuclear pore factor Nup124p. In addition, the NLS in this domain could be separated from another sequence element that specified the requirement for Nup124p. When this independent element was inserted next to the NLS of SV40, it was sufficient to cause nuclear import to become dependent on Nup124p.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Yeast strains, media, and genetic procedures.

Yeast strains used in this study are listed in Table 1. Yeast transformation and the preparation of S. pombe minimal liquid and plate media were done as described previously (36). Selective plates contained Edinburgh minimal media (EMM) and 2 g of “dropout” mixture/ml, a powder with adenine, uracil, and all amino acids except for nutrients that are absent as required for selection (43). A concentration of 10 μM vitamin B1 (thiamine) was added to minimal medium to repress the nmt1 promoter. 5-Fluoroorotic acid (5-FOA) (U.S. Biologicals, Swampscott, Mass.) was used at 1 mg/ml in EMM. YES 5-FOA/G418 plates were made from YES medium containing 1 mg of 5-FOA/ml and 500 μg (corrected for purity) of geneticin (Gibco) per ml.

TABLE 1.

Description of yeast strains and plasmids used

| Plasmid | Yeast strain

|

Plasmid description | Source or reference | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Wild type | nup124-1 | |||

| None | YHL912a | YHL5750a | ||

| pHL449-1 | YHL1282 | Wild-type Tf1-neoAI assay plasmid | 28 | |

| pHL476-3 | YHL1554 | Tf1-neoAI with frameshift in IN | 28 | |

| pHL490-80 | YHL1836 | Tf1-neoAI with frameshift in PR | 28 | |

| pHL891-19 | YHL4093 | Wild-type Tf1-neo assay plasmid (neo lacks XhoI site) | 34 | |

| pHL1277 | YHL5896 | pHL449-1 with a FLAG epitope inserted at the C-terminal end of Gag | 8 | |

| pHL1757 | YHL6773 | NLS-less version of pHL449-1 with the first 10 aa of Gag replaced by a FLAG epitopec | This study | |

| pSGP501b | YHL6779 | YHL6807 | SV40-NLS-GFP-LacZ fusion, expressed under control of inducible nmt1 promoter | This study |

| pSGP502b | YHL7171 | An ATG+ version of the GFP-LacZ fusion, expressed under control of inducible nmt1 promoter | This study | |

| pHL1822 | YHL7002 | YHL7030 | First 50 aa of Tf1 Gag (from 1 to 50) fused upstream to GFP-LacZ reporter carried on the pSGP502 vector | This study |

| pHL1775 | YHL6877 | YHL6891 | 50 aa of Tf1 Gag (from 51 to 100) fused upstream to GFP-LacZ reporter carried on the pSGP502 vector | This study |

| pHL1777 | YHL7012 | YHL7040 | 50 aa of Tf1 Gag (from 101 to 150) fused upstream to GFP-LacZ reporter carried on the pSGP502 vector | This study |

| pHL1779 | YHL7008 | YHL7036 | 50 aa of Tf1 Gag (from 151 to 200) fused upstream to the GFP-LacZ reporter carried on the pSGP502 vector | This study |

| pHL1781 | YHL7004 | YHL7032 | 50 aa of Tf1 Gag (from 200 to 251) fused upstream to GFP-LacZ reporter carried on the pSGP502 vector | This study |

| pHL1830 | YHL7022 | YHL7050 | First 40 aa of Tf1 Gag (from 1 to 40) fused upstream to GFP-LacZ reporter carried on the pSGP502 vector | This study |

| pHL1828 | YHL7020 | YHL7048 | First 30 aa of Tf1 Gag (from 1 to 30) fused upstream to GFP-LacZ reporter carried on the pSGP502 vector | This study |

| pHL1832 | YHL7026 | YHL7054 | First 20 aa of Tf1 Gag (from 1 to 20) fused upstream to GFP-LacZ reporter carried on the pSGP502 vector | This study |

| pHL2004 | First 10 aa of Tf1 Gag (from 1 to 10) fused upstream to GFP-LacZ reporter carried on the pSGP502 vector | This study | ||

| pHL1824 | 40 aa of Tf1 Gag (from 10 to 50) fused upstream to GFP-LacZ reporter carried on the pSGP502 vector | This study | ||

| pHL1826 | YHL7018 | YHL7046 | 30 aa of Tf1 Gag (from 20 to 50) fused upstream to GFP-LacZ reporter carried on the pSGP502 vector | This study |

| pHL1814 | YHL6913 | YHL6923 | 39 aa of Tf1 Gag (from 201 to 239) fused upstream to GFP-LacZ reporter carried on the pSGP502 vector | This study |

| pHL1906 | YHL7233 | Plasmid pHL1822 with a double mutation (K7A and R8A) present in the N-terminal NLS of Gag | This study | |

| pHL1908 | YHL7235 | Plasmid pHL1822 with a triple mutation (K7A, R8A, and R10A) present in the N-terminal NLS of Gag | This study | |

| pHL2062 | YHL7473 | Plasmid pHL1781 with a double mutation (K224A and K226A) present in the C-terminal NLS C1 of Gag | This study | |

| pHL2063 | YHL7474 | Plasmid pHL1781 with all four residues of C-terminal NLS C1 replaced by four alanine residues | This study | |

| pHL2064 | YHL7475 | Plasmid pHL1781 with a double mutation (K244A and K245A) present in the C-terminal NLS C2 of Gag | This study | |

| pHL1904 | YHL7231 | pHL1781 with the combination of a quadruple mutation in NLS C1 and a double mutation in NLS C2 of Gag | This study | |

| pHL2170 | The SV40 NLS was followed by Gag residues 11 to 30 fused upstream of GFP-LacZ in pSG502 | This study | ||

| pHL2172 | The FLAG epitope was followed by Gag residues 11 to 30 fused upstream of GFP-LacZ in pSG502 | This study | ||

| pHL1891 | YHL7227 | Tf1-neo assay plasmid pHL891-19 with a double mutation (K7A and R8A) present in the N-terminal NLS of Gag | This study | |

| pHL1893 | YHL7229 | Tf1-neo assay plasmid pHL891-19 with a triple mutation (K7A, R8A, and R10A) in the N-terminal NLS of Gag | This study | |

| pHL1724 | Tf1-neo assay plasmid pHL449-1 with all four residues of the C-terminal NLS C1 replaced by four alanine residues | This study | ||

| pHL1726 | Tf1-neo assay plasmid pHL449-1 with a double mutation (K224A and K226A) in the C-terminal NLS C1 of Gag | This study | ||

| pHL1728 | Tf1-neo assay plasmid pHL449-1 with a double mutation (K244A and K245A) in the C-terminal NLS C2 of Gag | This study | ||

| pHL1837 | YHL6996 | pHL449-1 with the combination of a quadruple mutation in NLS C1 and a double mutation in NLS C2 of Gag | This study | |

| pHL1895 | Tf1-neo assay plasmid pHL891-19 with a double mutation in the N-terminal NLS of Gag, quadruple mutation in the NLS C1, and a double mutation in NLS C2 of Gag | This study | ||

| pHL2012 | YHL7775 | YHL7779 | Tf1-neo assay plasmid pHL891-19 with the SV40 NLS in place of the N-terminal NLS of Gag | This study |

| pHL1897 | Tf1-neo assay plasmid pHL891-19 with a triple mutation in the N-terminal NLS of Gag, quadruple mutation in the NLS C1, and a double mutation in NLS C2 of Gag | This study | ||

Plasmid construction.

Many plasmids used for this study were constructed using PCR cloning techniques. To avoid problems related to inadvertent mutations created during PCR, the plasmids were made in duplicate from independent PCRs, and the properties of each plasmid were studied in parallel. The high-fidelity enzyme Pfu or Turbo Pfu (Stratagene) was used for all PCRs. Plasmids used in this study are also listed in Table 1.

Mutations in the transposon.

Point mutations have been created within the sequences of the three NLSs of Gag by using the fusion PCR technique described previously (28). Starting from the Tf1-neo assay plasmid pHL891-19, the sequence for the N-terminal NLS of Gag, KRIR, was converted into either AAIR (double mutation) or AAIA (triple mutation). The two restriction sites XhoI and AvrII that were unique in the plasmid pHL891-19 were used for the cloning of the fusion-PCR products. Resulting plasmids that contain these new mutant versions of Tf1 were named pHL1891 and pHL1893, respectively. The fusion PCR technique was also exploited to generate point mutations within the two putative C-terminal NLSs of Gag, using the two unique restriction sites AvrII and BsrGI of the Tf1-neoAI assay plasmid pHL449-1. The two plasmids pHL1724 and pHL1726 were the Tf1-neoAI assay plasmid pHL449-1 with the sequence for the C-terminal NLS C1 (RKPKK) converted into either RAPAK or AAAAK, respectively. A sequence encoding a two-alanine replacement of the NLS C2 (KKRR converted into AARR) was also created within the Tf1-neoAI assay plasmid to generate the plasmid pHL1728. The plasmid pHL1837 contained the pHL449-1 backbone and the combination of sequences encoding a quadruple mutation of the NLS C1 (as in pHL1726) and a double mutation of the NLS C2 (as in pHL1728). The NLS-less version of Tf1 was generated as follows. The two unique restriction sites XhoI and AvrII in the plasmid pHL891-19 were used to insert a fusion PCR product in which the first 10 amino acids of Gag were replaced by an NgoMI restriction site. Two complementary oligonucleotides encoding a FLAG epitope were cloned into the NgoMI site. The resulting plasmid, pHL1757, encoded a FLAG epitope with the sequence ADYKDDDDKG.

In the context of the transposon, fusion PCR was used to replace the first 10 amino acids of Gag with a 10-amino-acid sequence of an SV40 NLS (MAPKKKRKVV) that had been expressed in S. pombe previously (39). The four oligonucleotides used in this fusion PCR were HL38, HL39, HL671, and HL672. The two restriction sites XhoI and AvrII were unique in pHL891-19 and were used for the cloning of the fusion PCR products. Two equivalent plasmids resulting from this construction were pHL2011 and pHL2012. The sequences of the junctions between Gag and SV40-NLS were verified by sequencing.

Construction of chimeric proteins.

All of the green fluorescent protein (GFP) fusion constructs that were needed for the microscopy study were derived from the vector pSGP502 (39). To examine the ability of different portions of Gag to localize in the nucleus, different sections of Gag were PCR amplified and then fused in frame to the green fluorescence reporter gene GFP-LacZ that was carried on the vector pSGP502. For this purpose, the wild-type sequence of Tf1 that was carried on the plasmid pHL449-1 was used as a PCR template. The oligonucleotides that were used for PCR amplifications all contained a KpnI restriction site, so that the PCR products could be then digested with KpnI and subsequently cloned into the unique KpnI site that is located upstream of the GFP-LacZ sequence of the vector pSGP502. The sequences of the junctions between Gag and GFP were verified by sequencing. The Gag-GFP fusions that contained different mutant versions of the amino- and carboxyl-termini of Gag were constructed in the same manner, except that the template plasmids that were used for PCR amplification were either pHL1891, pHL1893, pHL1724, pHL1726, pHL1728, or pHL1837. The detailed information about the Gag sequences contained in each individual construct is given in Table 1. The expression of the Gag-GFP-LacZ constructs was driven by the ATG codon of Gag and an inducible nmt1 promoter.

To examine the ability of the SV40 NLS to localize Gag in the nucleus, the sequence corresponding to the NLS of SV40 followed by Gag residues 11 to 30 was PCR amplified using pHL2012 as template and then fused in frame to the GFP-LacZ reporter on the vector pSG502. Two independent isolates of this plasmid were pHL2170 and pHL2171. The two oligonucleotides used for the PCR were HL771 and HL627. Two equivalent plasmids, pHL2172 and pHL2173, that had the FLAG epitope in place of the SV40 NLS were made. Here, the oligonucleotides used for the PCR were HL772 and HL627.

Transposition and homologous recombination assays.

Tf1 transposition frequencies were determined as described previously (29). Briefly, Tf1 transposition was monitored by placing a neo-marked Tf1 element under the control of the inducible nmt1 promoter. The neo gene allowed cells to grow in the presence of 500 μg of G418/ml; thus, Tf1 transposition activity could be correlated with the ability of cells to grow on G418-containing medium. S. pombe strains that contained a Tf1-neo plasmid were grown as patches on EMM-ura dropout agar plates in the absence of thiamine to induce transcription of the nmt1-Tf1-neo fusion. After 4 days of 32°C incubation, these plates were then replica printed to medium containing 5-FOA to eliminate the URA3-Tf1-neo plasmid (5). Finally, 5-FOAr patches were printed to medium containing both 5-FOA and G418 and incubated at 32°C for 2 days to detect strains that became resistant to G418 as the result of insertions of the neo-marked Tf1 element into the genome (30, 31).

The presence of Tf1 cDNA in the nucleus was examined by cDNA recombination assays, which were conducted according to the method of Atwood et al. (1). This protocol is similar to that of the transposition assay in that strains with the neoAI-marked Tf1 plasmid were first grown as patches on agar plates that contained EMM (plus 10 μM thiamine and dropout powder) and then replica printed to similar EMM plates that lacked thiamine. After 4 days of 32°C incubation, the plates were replica printed directly to YES medium that contained 500 μg of G418/ml. Recombination between cDNA and cellular transposon sequences was scored on the G418 plates after 48 h of growth at 32°C.

Isolation of Tf1 cDNA from whole-cell extracts.

Total cDNA content was extracted from stationary-phase cells grown under inducing conditions (absence of thiamine). Approximately 109 cells (100 optical density at 600 nm [OD600] units) were used for each preparation. These preparations, as described previously (29), were used to generate materials for cDNA blot analysis of BstXI digests (2). To examine the accumulation of cDNA in the cells, the filters were hybridized with a 1.0-kb neo probe derived from a BamHI digest of pGH54 (24).

Protein extraction and immunoblot detection of Tf1 Gag and IN.

Total proteins were extracted from cells grown under inducing conditions (absence of thiamine) by using a previously published protocol (2). Protein extracts were collected, and an equal volume of 2× sample buffer (2) was added. The mixture was boiled for 3 min, and 25 μg of total protein from each sample was loaded onto sodium dodecyl sulfate–10% polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS–10% PAGE) gels for immunoblot analysis. Standard electrotransfer techniques were used (47) with Immobilon-P membranes (Millipore). The detection method used was the ECL system as described by the manufacturer (Amersham), except that the secondary antibody, horseradish peroxidase-conjugated donkey anti-rabbit immunoglobulin, was used at a 1:10,000 dilution. The primary polyclonal antisera used for each filter were from production bleeds 660 (anti-Gag) and 657 (anti-IN) (31).

The preparation of large-scale yeast extracts and the subsequent analysis on sucrose gradients were based on previously published protocols (2, 31), with minor modifications. Total proteins were extracted from approximately 5 × 108 cells that were grown under inducing conditions (absence of thiamine). Five milliliters of supernatant recovered from a 3,000-rpm spin of an SS34 rotor (5 min) of the cell extract was loaded onto a 20 to 70% linear gradient of sucrose in extraction buffer. The gradients were spun for 16 h at 25,000 rpm in a Beckman SW28 rotor. Samples of 1.2-ml fractions were collected, and 100 μl from each was precipitated in 10% trichloroacetic acid. The pellets were washed in cold acetone, resuspended in sample buffer, and loaded onto SDS-polyacrylamide gels for immunoblot analysis.

Indirect immunofluorescence.

The anti-FLAG M2 monoclonal antibody (Eastman Kodak, New Haven, Conn.) and FITC-Oregon green 488 goat anti-mouse immunoglobulin G IgG antibody (Molecular Probes) were used for immunofluorescence experiments essentially as previously described (8). To visualize nuclear DNA, cells were stained with 1 μg of DAPI (4′,6′-diamidino-2-phenylindole)/ml. Detection of FLAG-tagged Gag in intact cells was achieved by incubating mutant and wild-type cells containing the FLAG-tagged Gag under inducing conditions. Cells were mounted on glass slides with mounting solution (1 mg of p-phenylenediamine [catalog no. P-1519; Sigma], 1 μg of DAPI/ml in 50% glycerol). The cells were examined by using fluorescence microscopy with a Zeiss Axioscope equipped with UV and fluorescein isothiocyanate optics. Images were collected and imported into Adobe Photoshop 4.0.1 for figure presentation.

GFP microscopy.

To visualize the cellular localization of GFP-LacZ fusion proteins, cells expressing GFP fusions were grown in selective media under inducing conditions (absence of thiamine) to an OD600 of 0.3. Cells were then washed once with 1× PBS and resuspended in a 1× PBS solution that contained 2.5 μg of Hoechst dye/ml before being transferred to microscope slides. Cells were mounted onto the microscope slides using Vectashield (Vector Laboratories Inc., Burlingame, Calif.). GFP images were collected and imported into Adobe Photoshop 5.0.1 for figure presentation.

RESULTS

The Tf1 Gag protein contains two distinct karyophilic domains.

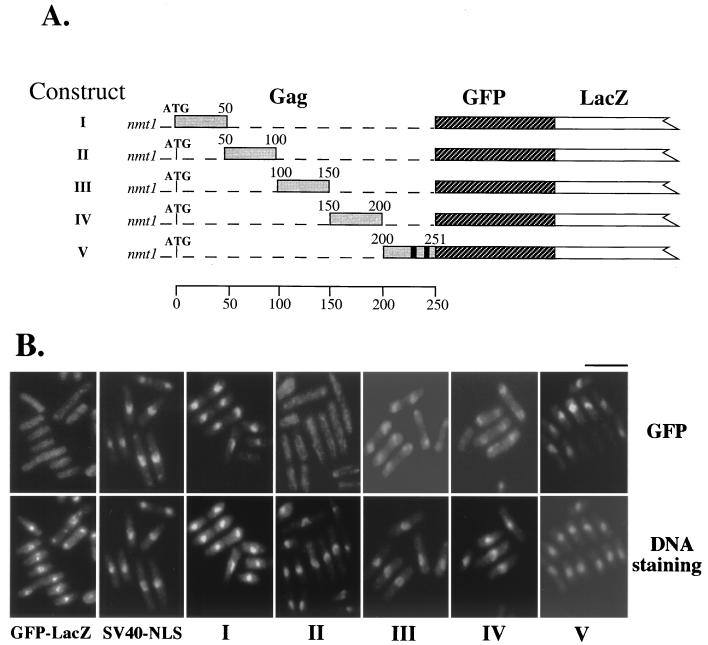

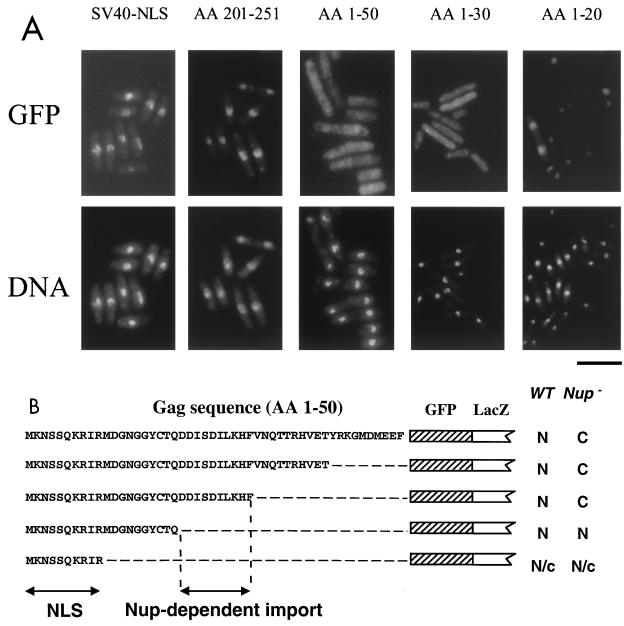

Our previous studies showed that the Gag protein of Tf1 is localized in the nucleus of cells in stationary phase (3, 8). In this study, we first investigated the question of whether Gag contains any amino acid sequences with a karyophilic property. For this purpose, we examined the ability of domains of Gag to direct the GFP into the yeast nucleus. Gag was divided into five sections that were fused to the N terminus of a chimeric coding sequence that included GFP and LacZ (Fig. 1A). The molecular masses of these fusion proteins were approximately 140 kDa, and thus they were unlikely to enter the nucleus by passive diffusion. Their expression in yeast cells was under the control of the inducible nmt1 promoter. Immunoblot analysis using antiserum against LacZ showed that each fusion protein possessed its predicted molecular weight and was accumulated to similar levels in the cells (data not shown). Examination of the localization of GFP signals in live cells was performed with cells that were grown under inducing conditions and harvested at an OD600 of 0.3. We found that two of the five domains of Gag contained the ability to cause nuclear localization (Fig. 1B). Fusions of residues 1 to 50 and residues 200 to 251 were found to possess nuclear localizing activity (Fig. 1B). As a control, cells expressing the GFP-LacZ reporter protein alone displayed GFP signals that distributed evenly throughout the cytoplasm. It is interesting to note that the LacZ fusion protein was not occluded from the nucleus. This suggests that small amounts of LacZ did enter the nucleus without the addition of an NLS. However, a significant concentration of LacZ fusion protein was localized in the nucleus when fused to the classical NLS from SV40 large antigen (Fig. 1B).

FIG. 1.

Gag contains two distinct karyophilic domains. (A) Construction of Gag-GFP-LacZ chimeric proteins. Shown is a schematic representation of the five domains of Tf1 Gag that were fused to the GFP-LacZ reporter. Roman numerals used to name the constructs correspond to the numbers used in panel B. The five domains of Gag with the location of their ATG codons are indicated as dark shaded boxes. The numbers above the shaded boxes indicated the residues of Gag that were contained in the corresponding fusion proteins. The GFP and LacZ sequences are represented by the hatched and white boxes, respectively. The two putative NLSs that were identified by a computer-based search are indicated by two vertical black boxes within the Gag sequence. The expression of the fusion proteins was under the control the inducible nmt1 promoter. (B) Ability of the five domains of Gag to direct the GFP-LacZ reporter proteins into the nucleus. The localization of GFP fusion proteins was then examined to determine the ability of the corresponding Gag residues to direct the protein into the nucleus (top panels). In the control strains, we included GFP-LacZ with or without the NLS of SV40. DNA was counterstained using Hoechst dye (bottom panels). Bar, 10 μm.

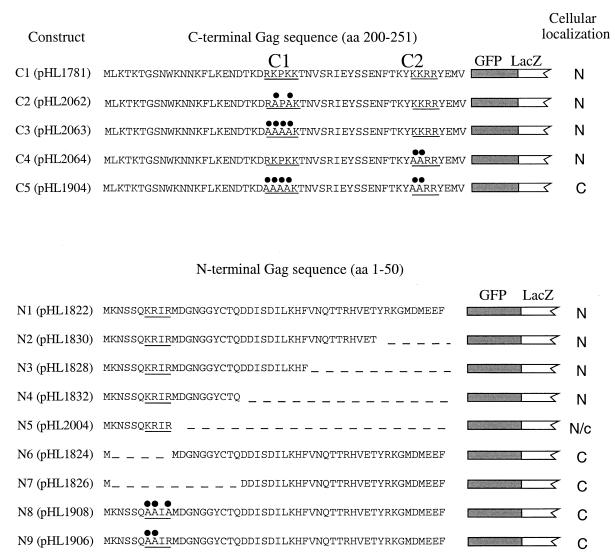

A computer-based search (PSORT program; GenomeNet, Tokyo, Japan) for NLSs present in the sequence of Gag identified two putative NLSs within the last 50 amino acids of Gag (C terminus) at amino acid residues 224 to 227 (C1, KPKK) and 244 to 247 (C2, KKRR) (22) relative to the ATG codon of Gag (Fig. 2, top). However, the computer search found no obvious NLS in the karyophilic domain (amino acids 1 to 50) that we identified at the N terminus of Gag.

FIG. 2.

Mutational analysis of the NLS activity identified in the C-terminal and the N-terminal domains of Gag. The sequences of the last 50 residues (top panel) and the first 50 residues (bottom panel) of Gag were fused to GFP-LacZ. The hatched and white boxes represent the GFP and LacZ sequences, respectively. The two putative NLSs that have been identified by a computer-based search are named C1 and C2. Their corresponding amino acid sequences are also underlined (RKPKK and KKRR, respectively). The NLS in the N-terminal domain of Gag, KRIR, is underlined. The black circles denote the positions of alanine substitution mutations that were created within the NLS sequences. The cellular localization of the corresponding GFP fusion proteins are indicated by either N (nuclear) or C (cytoplasmic). The first 10 residues of Gag contained karyophilic activity, but this was somewhat less efficient than that of the full-length 50 amino acids of the Gag N terminus. Its cellular localization is therefore indicated as N/c. aa, amino acid.

The NLS activity of the C terminus of Gag is due to two distinct amino acid sequences that were dispensable for Tf1 transposition.

To determine whether the two NLSs predicted to be in the C terminus of Gag played a role in nuclear localization, we generated amino acid substitutions in the protein that consisted of residues 200 to 251 of Gag fused to the N terminus of GFP-LacZ. The original amino acid sequence of NLS C1, RKPKK, was converted to either RAPAK or AAAAK (Fig. 2, top). In a similar manner, the original sequence of NLS C2, KKRR, was converted to AARR. Results of fluorescence microscopy showed that the karyophilic property of this C-terminal fragment of Gag was not altered when either one of the two putative NLSs was mutated. Interestingly, the nuclear localization of the GFP-LacZ fusion was totally disrupted when both NLS C1 and C2 were simultaneously mutated (Fig. 2, top). Images of cells with the intact C-terminal domain and the version with substitutions in both C1 and C2 are shown in Fig. 3. The expression level of the Gag-GFP-LacZ fusions was measured by immunoblot analysis using LacZ antibodies and was found to be unaffected by the presence of the point mutations (data not shown).

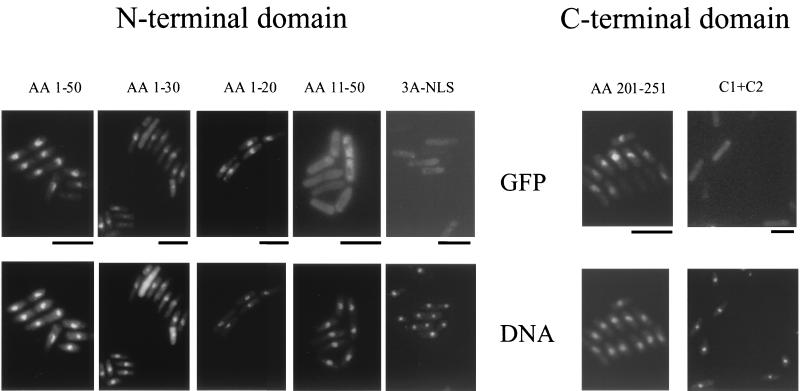

FIG. 3.

Analysis of the NLS activity identified in the N-terminal and C-terminal domains of Gag. Shown is localization in wild-type cells of fusion proteins that contained GFP-LacZ and residues from the N-terminal and C-terminal domains of Gag. These are representative images for the proteins described in Fig. 2. The localization of the reporter was detected by green GFP signals. The headings indicate the amino acid (AA) residues of Gag that were fused to GFP-LacZ or the type of mutations that were made in the NLSs of the 50-amino-acid domains. The positions of nuclei were indicated by staining of DNA with Hoechst dye. Bars, 10 μm.

To investigate whether the NLS activity in the C-terminal domain of Gag played a role in the process of Tf1 retrotransposition, we introduced the same alanine substitution mutations into the sequence of an intact Tf1-neoAI transposon and assayed the transposition activity of these newly created elements. Tf1 activity was monitored using an assay that detected the resistance to G418 caused by the insertion of a neo-marked Tf1 element into the genome of S. pombe cells (31). Mutations in either one of these two NLSs, C1 to AAAA or C2 to AA, did not affect Tf1 transposition activity. An element that contained these mutations in both NLSs was found to be reduced for Tf1 transposition by no more than twofold compared to the levels of the wild type (data not shown). This transposition defect was not associated with a reduction in Tf1 protein or cDNA (data not shown).

The NLS in the N terminus of Gag is in the first 10 residues, and it is absolutely required for Tf1 transposition.

Since a computer-based search for NLSs present within the N-terminal domain of Gag revealed no obvious candidates, we investigated whether this fragment truly contained an NLS element. For this purpose, we conducted an extensive search for a minimal sequence required for nuclear localization. Various fragments of the N terminus of Gag were fused to the N terminus of GFP-LacZ (Fig. 2, bottom). As mentioned earlier, the first 50 amino acids of Gag were able to direct the Gag-GFP-LacZ protein into the nucleus. Progressive deletions of Gag sequence that originated at residue 50 and extended to residue 21 did not inhibit the nuclear localization of the fusion proteins. A GFP-LacZ protein that contained only the first 10 amino acid residues of Gag was concentrated in the nucleus but with somewhat less efficiency than proteins with the first 20 amino acids of Gag. This result indicated that important information for the nuclear localization was contained within the first 10 amino acids of Gag. The importance of these 10 amino acid residues for nuclear localization was further confirmed by two additional deletions in the protein with amino acids 1 through 50 of Gag. We found that the two Gag-GFP-LacZ fusions that lacked the first 10 or 20 residues of Gag were distributed evenly throughout the cytoplasm (Fig. 2, bottom). Figure 3 contains images of a representative set of the strains listed in Fig. 2.

Interestingly, examination of the first 10 amino acids of Gag identified a stretch of four residues (KRIR; starting at residue 7) with similarity to the pattern 4 type of NLS as detected by the PSORT algorithm (http://psort.nibb.ac.jp/). PSORT uses the following two rules to detect pattern 4 NLSs: four residues composed of four basic amino acids (K or R) or composed of three basic amino acids (K or R) and either H or P. To determine whether these basic residues were truly critical for nuclear localization, we replaced the basic amino acids of this putative NLS by alanine residues and tested these newly created GFP fusion proteins for their ability to be localized in the nucleus. The nuclear localization activity of the N-terminal NLS of Gag was totally disrupted when two or three basic residues were replaced by alanine (KRIR was converted to either AAIA or AAIR, respectively) (Fig. 2 and 3).

The NLS in the N terminus of Gag was required for transposition but not particle assembly.

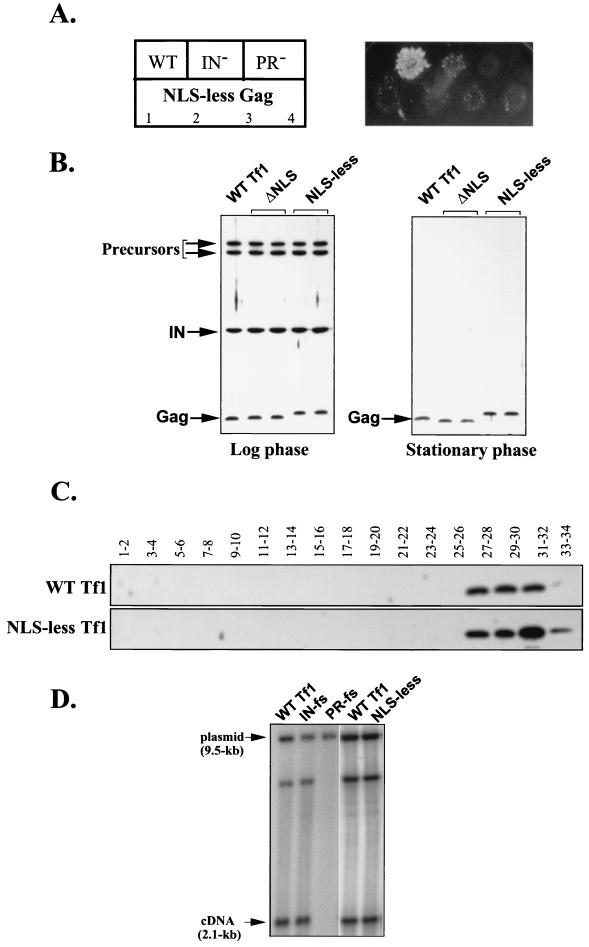

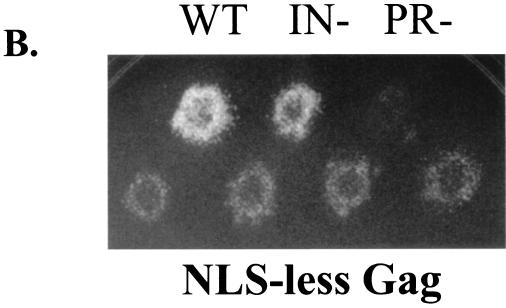

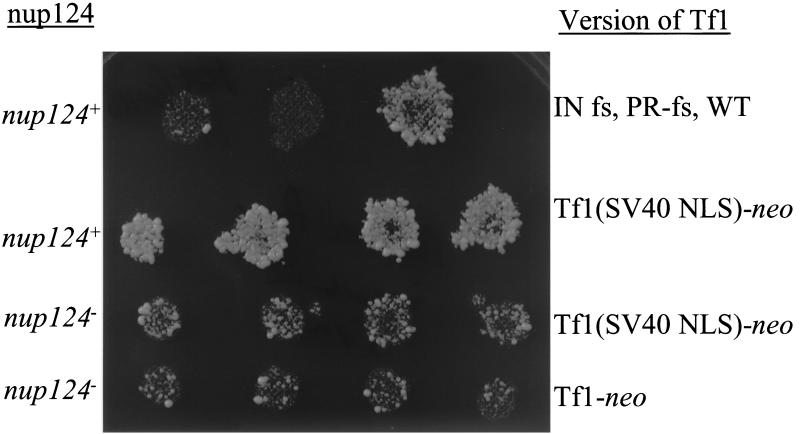

We next investigated whether the NLS activity of the first 10 amino acid residues of Gag was required for Tf1 transposition. Here too Tf1 activity was monitored using the assay that detected the resistance to G418 caused by the insertion of a neo-marked Tf1 element into the genome of S. pombe cells (31). A brief description of the assay follows. The assay plasmid (pHL449-1) carried a copy of Tf1 (Tf1-neoAI) that was placed under the control of the inducible nmt1 promoter. Patches of cells harboring the plasmid with Tf1-neoAI were induced for transposition by activating the expression of the nmt1 promoter. Before the induced patches were tested for resistance to G418, the plasmid with Tf1-neoAI was subjected to counterselection by replica-printing cells to medium that contained 5-FOA. Thus, only cells that received a transposition event (conferring a G418r phenotype) and subsequently lost the assay plasmid (conferring a 5-FOAr phenotype) grew on medium that contained G418 and 5-FOA (3, 8). Figure 4A presents the results of a transposition assay and shows that a patch of cells that contained wild-type Tf1-neoAI produced confluent growth on a G418–5-FOA plate. A frameshift mutation in the N terminus of IN caused a significant drop in transposition (1). In addition, a frameshift mutation in PR blocked the expression of RT and IN and produced no resistance to G418. In the context of Tf1-neoAI, we engineered the N terminus of Gag such that the first 10 amino acids were replaced by the 10-amino-acid FLAG epitope. This newly created version of Tf1-neoAI was named NLS-less Tf1-neoAI. The transposition assay was performed to determine whether the absence of the NLS affected Tf1 activity. Indeed, as presented in Fig. 4A, the NLS-less version of Tf1 exhibited a significant defect in transposition compared to that of the wild-type Tf1.

FIG. 4.

Characterization of an NLS-less version of Tf1 in which the first 10 amino acids of Gag were replaced by a FLAG epitope. (A) Transposition assay based on G418r due to the insertion of Tf1-neoAI. Top row, three control strains were the wild-type strain (WT) containing either the wild-type Tf1-neoAI assay plasmid (YHL1282) or Tf1-neoAI with a frameshift created either in IN (YHL1554) or in PR (YHL1836) of Tf1. Bottom row, two independent yeast transformants of each of the two strains (YHL6773 and YHL6774) were tested. These strains contained two independent clones of the NLS-less version of the Tf1-neoAI assay plasmid. (B) The levels of Tf1 Gag and IN in strains that were wild type (lane 1, YHL1282) or contained the NLS-less version of Tf1 (lanes 4 and 5, YHL6773). The levels of Tf1 Gag and IN were also tested for a Tf1 version in which the N-terminal NLS in Gag was deleted (lanes 2 and 3). These immunoblots of S. pombe extracts were made from cells harvested either at log phase (left) or at stationary phase (right). The filters were probed simultaneously with anti-Gag and anti-IN antisera. The positions of Tf1 precursors, Gag, and IN are indicated by arrows. (C) Sucrose gradient analysis. The top panel is an immunoblot of an SDS–10% PAGE with fractions from a sucrose gradient that contained an extract from a wild-type Tf1-expressing strain (YHL1282). The antibody probe was anti-Gag serum. The bottom panel was also probed with anti-Gag serum and is an immunoblot of pooled fractions from a strain that expressed the NLS-less version of Tf1 (YHL6773). (D) Effects of the lack of the N-terminal NLS in Gag on the accumulation of cDNA in the cell. This DNA blot was used to measure the levels of Tf1 cDNA produced in the strain with the NLS-less version of Tf1(YHL6773). Three control strains were the wild-type strain containing versions of Tf1 that either were wild type (YHL1282) or contained a frameshift (fs) mutation in IN (YHL1554) or a frameshift mutation in PR (YHL1836). The DNA was digested with BstXI and probed with a neo-specific sequence. The 2.1-kb band was generated by the linear cDNA while the 9.5-kb band was produced by a vector sequence.

We hypothesized that the transposition defect that was observed in the absence of the NLS was the result of a defect in the ability of the transposon to import its material into the nucleus. However, we first tested whether the NLS-less mutant of Tf1-neoAI altered the levels of Tf1 proteins that accumulated. Figure 4B presents the results of immunoblot analysis of IN and Gag produced in the cells that contained either the NLS-less mutant or a wild-type version of Tf1-neoAI. Whole-cell extracts were prepared from cells that were harvested at either log phase or stationary phase. Blots were then probed simultaneously with antisera against IN and Gag. We found that yeast cells harboring the NLS-less mutant produced the same amounts of IN and Gag as the cells containing a wild-type version of Tf1. We noticed that the replacement of the first 10 residues of Gag by a FLAG epitope caused an aberration in the migration of the resulting Gag protein on the SDS-PAGE gels. This aberrant migration was also observed when FLAG was inserted at different locations in the Gag sequences (not shown), and therefore, it is probably due to the presence of several highly charged residues within the sequence of the FLAG epitope. No IN was detected in stationary-phase cells because of a degradation mechanism that creates a significant molar excess of Gag relative to IN and RT (2). This finding indicated that the translation and protein processing occurred normally in the absence of the Gag NLS.

In the life cycle of retrotransposons, mRNA and retroelement proteins all assemble into VLPs, in which reverse transcription of RNA into cDNA takes place. To ask whether the absence of the NLS in the Gag of Tf1 altered the formation of VLPs, we compared the sedimentation properties on sucrose gradients of the NLS-less mutant of Tf1 with that of the wild type. Whole-cell extracts from stationary-phase cultures were subjected to sucrose gradient centrifugation, and the fractions were analyzed on immunoblots (Fig. 4C). Consistent with previous observations, wild-type Gag was detected at the bottom of the sucrose gradient, corresponding to the mature form of Tf1 VLPs (2, 28, 31) (Fig. 4C). Similarly, Gag produced by the cells expressing the NLS-less mutant of Tf1 showed velocity properties that were undistinguishable from those of wild-type Gag (Fig. 4C). This finding suggested that VLPs were formed normally in the NLS-less mutant of Tf1.

In another test of the function of VLPs produced by the NLS-less Tf1, we measured the levels of mature cDNA produced. We used a previously published method of blot analysis to measure the accumulated levels of Tf1 cDNA in cells that expressed the NLS-less Tf1-neoAI. Liquid cultures of cells induced for Tf1 expression were extracted for total DNA that was then digested with BstXI and subjected to DNA blot analysis. The results presented in Fig. 4D show that the wild-type Tf1 produced a 2.1-kb fragment of cDNA that was detected with a neo-specific probe. This BstXI fragment is derived from the terminal sequence of Tf1 that is the final region to be reverse transcribed and therefore represents the levels of full-length products. The DNA extracted from control strains showed that the frameshift in IN did not reduce the intensity of the 2.1-kb band, whereas the frameshift just upstream of RT (PR-fs) blocked the synthesis of cDNA. The strain with the NLS-less version of Tf1-neoAI generated normal levels of the 2.1-kb fragment of cDNA. A 9.5-kb band resulted from the BstXI digestion of the Tf1 plasmids, and this species served as an internal control for levels of material loaded in each lane. This finding further indicated that the defect in Tf1 transposition caused by the absence of the NLS in Gag was in a late step of transposition, i.e., after VLP formation and reverse transcription.

The NLS-less mutation in Tf1 inhibited the nuclear import of Gag.

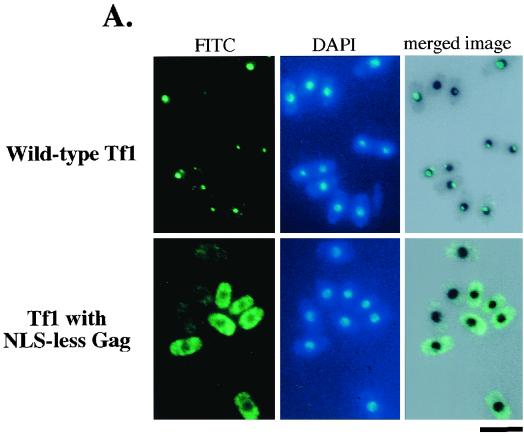

An indirect immunofluorescence study was conducted to determine whether the Gag protein produced by Tf1-neoAI with the NLS-less mutation was imported into the nucleus. As a control, we used a functional FLAG-tagged allele of wild-type Tf1 that contained a FLAG epitope inserted near the C terminus of Gag. We previously showed that this control version of Tf1, named Tf1(FLAG)-neoAI, expressed normal levels of Tf1 proteins and cDNA and possessed wild-type levels of transposition activity (3, 8). The nuclear import of Tf1 Gag was originally characterized with this strain (3, 8). Wild-type cells that were induced for expression of either NLS-less Tf1 or Tf1(FLAG)-neoAI were subjected to immunofluorescence staining with the use of the M2 anti-FLAG monoclonal antibody. Consistent with the data reported previously (3, 8), we found that the majority of cells with wild-type Tf1 produced a single primary focus of Gag signal (green) within the nucleus, as demonstrated by the colocalization of the FLAG-Gag signals and nuclear staining (black) (Fig. 5A). No FLAG signal was observed from cells that were not induced for Tf1 expression (data not shown). A totally different scenario was observed in the strain with the NLS-less version of Tf1-neoAI. FLAG-Gag signals were distributed evenly throughout the cytoplasm. In addition, positions corresponding to cell nuclei lacked FLAG-Gag signals, suggesting that the import of Gag protein was totally disrupted in these cells.

FIG. 5.

(A) Immunofluorescence analysis of Gag expressed by intact Tf1. Top, immunofluorescence of cells expressing wild-type Tf1. The wild-type strain YHL5896 contained a FLAG-Gag version of the Tf1-neoAI plasmid (pHL1277). In the top panels, the green fluorescein isothiocyanate (FITC) signals are specific for the FLAG-Gag protein and the blue signals indicate the locations of nuclei counterstained with DAPI. The panel in the upper right position is a merge of the FLAG-Gag signals produced by YHL5896 with an inverted black and white image of its DAPI stain. The merge was generated with Adobe Photoshop 4.0 with the screen function set at 65% opacity. Bottom, the same experiment was conducted except that the yeast strain (YHL6773) contained the NLS-less version of Tf1 (pHL1757). Bar, 10 μm. (B) Effects of the lack of the N-terminal NLS in Gag on cDNA homologous recombination. This cDNA recombination assay was used to detect the presence of cDNA in the nucleus. The same yeast strains that were used for the transposition assay presented in Fig. 4A were subjected to cDNA homologous recombination. These strains contained two independent clones of the NLS-less version of the Tf1-neoAI assay plasmid. Three control strains were the wild-type strain (WT) containing either the wild-type Tf1-neoAI assay plasmid (YHL1282) or Tf1-neoAI with a frameshift mutation created either in IN (YHL1554) or in PR (YHL1836) of Tf1.

The NLS activity of Gag is required for the uptake of Tf1 cDNA into the nucleus.

Our previous studies demonstrated that the Gag protein, together with cDNA and other Tf1 proteins, forms large macromolecular structures named VLPs (28, 31). We hypothesized that if the nuclear import of Tf1 Gag was defective in the absence of its N-terminal NLS, then the import of Tf1 cDNA may also be altered in this mutant. To investigate this possibility, we used a cDNA recombination assay that was previously developed to measure the presence of cDNA in the nucleus (1). This assay measures homologous recombination between copies of Tf1 cDNA and Tf1 plasmid sequences. The Tf1-neoAI in the transposition assay plasmid contained an artificial intron in the reading frame of neo. The intron was in the opposite orientation of neo and because it could not be spliced from the neo mRNA, it inactivated the neo gene. However, the intron can be spliced from the Tf1 mRNA. Once the intron is spliced from the Tf1 mRNA and reverse transcription is complete, the cDNA is carried into the nucleus, where it recombines with its homologous sequence in the assay plasmid. This generates cells that are resistant to G418. Wild-type levels of this recombination indicate that normal levels of Tf1 cDNA are produced and that this cDNA is transported into the nucleus. The results presented in Fig. 5B show that the NLS-less version of Tf1-neoAI displayed a reduction in the homologous recombination of Tf1 cDNA compared to that of the wild-type strain or the strain with a frameshift in IN that shows the normal level of homologous recombination in the absence of any transposition. Since we found that the NLS-less mutation did not reduce the amounts of cDNA produced, the homologous recombination assay indicated that the absence of the N-terminal NLS in Gag reduced the nuclear uptake of Tf1 cDNA.

The nuclear pore factor Nup124p was specifically required for the NLS activity associated with the N-terminal domain of Gag.

We previously showed that Nup124p, an FXFG nuclear pore factor, possesses a specialized activity that is specifically required for the nuclear localization of transposon material and not other proteins tested (3). In this experiment, we investigated whether the nuclear import of the Gag-GFP-LacZ fusion proteins required Nup124p. For this purpose, we determined whether the nuclear localization of GFP-LacZ fusion proteins that contained the NLS activities in either the N-terminal or the C-terminal domains of Gag was affected by the truncation of Nup124p protein encoded by the nup124-1 allele. This allele, isolated by random mutagenesis, caused a severe defect in Tf1 transposition and the nuclear import of Gag (3). As a control in this experiment, we also used a GFP-LacZ fusion that contained the classical NLS from SV40 large T antigen (Fig. 1B). This nuclear localization activity was not affected by the truncation of nup124-1 (Fig. 6A). Similarly, the nuclear localization of the C terminus of Gag (amino acids 200 to 251) was unaffected in the strain with the mutation in nup124-1 (Fig. 6A). Interestingly, the NLS activity of the N terminus of Gag (residues 1 to 50) was disrupted in the strain with the nup124-1 mutation. The GFP signals spread randomly throughout the cytoplasm. This finding indicated that the nuclear pore factor Nup124p played an important and specific role in the activity of the NLS that we mapped in the N-terminal domain of Gag.

FIG. 6.

The requirement of Nup124p for the function of the NLSs in Gag. (A) Nuclear localization of the N- and C-terminal domains of Gag fused to GFP-LacZ expressed in cells with the nup124-1 mutation. These images are a representative sample of the proteins tested in panel B. The localization of the reporter was detected as green GFP signals. The positions of nuclei were indicated by staining of DNA with Hoechst dye. As a control, we used a GFP-LacZ fusion protein that contained the classical NLS from SV40 large T antigen. Bar, 10 μm. (B) Summary of the localizations of the proteins with residues from the N-terminal domain of Gag as expressed in cells with the nup124-1 mutation. The positions are indicated for the residues with NLS activity and the residues that impose Nup124p dependence on import. AA, amino acid; WT, wild type.

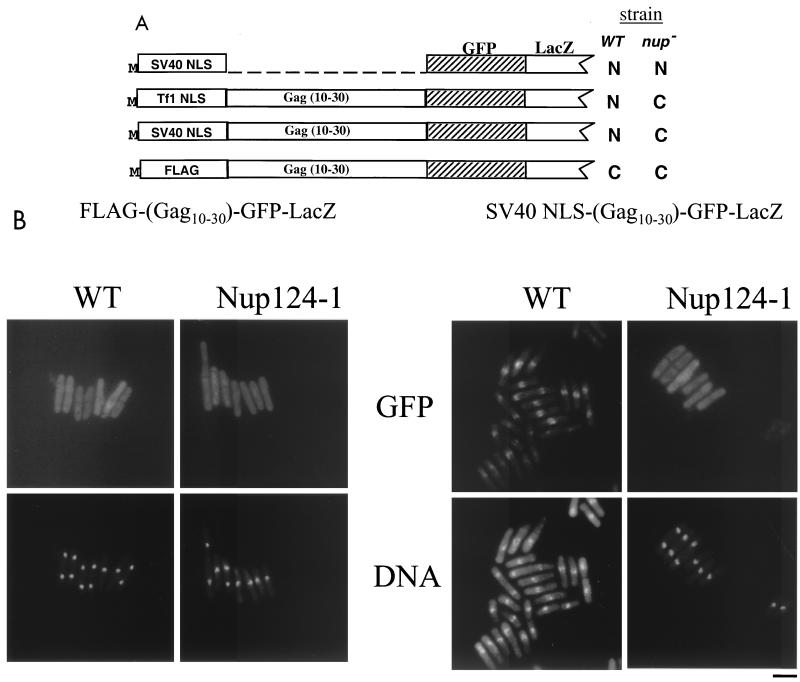

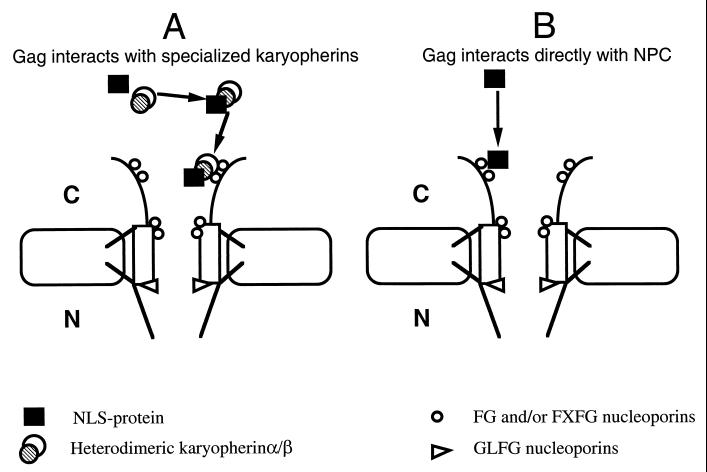

To determine which of the first 50 residues of Gag were responsible for the dependence on Nup124p, the localization of GFP-LacZ proteins with additional deletions was determined. Although the nuclear localization of Gag(1-30)-GFP-LacZ retained the requirement for Nup124p (compare Fig. 3 with 6A), Gag(1-20)-GFP-LacZ localized efficiently in the nuclei of cells with the nup124-1 mutation. The localizations of proteins with additional deletions are shown in Fig. 6B. These results suggested that residues 20 to 30 of Gag were sufficient to impose Nup124p dependence on the import of the NLS in residues 1 to 10. To test the possibility that the requirement of Nup124p for import was specified by residues independent of the NLS, amino acids 10 to 30 of Gag were fused downstream of the SV40 NLS in a protein with GFP-LacZ (Fig. 7A). Interestingly, residues 10 to 30 of Gag were sufficient to cause the import activity of the SV40 NLS to require Nup124p (Fig. 7B, right panels). That this import required the SV40 NLS was demonstrated by replacing it with the FLAG epitope. This protein remained in the cytoplasm regardless of whether Nup124p was functional (Fig. 7A and B, left panels).

FIG. 7.

Residues 10 to 30 of Gag confer the requirement of Nup124p on the nuclear import of a heterologous protein with the NLS of SV40. (A) Summary of localization data. Fusion proteins consisted of GFP-LacZ fused to the C termini of the SV40 NLS, the Tf1 NLS and Gag10–30, the SV40 NLS and Gag10–30, or the FLAG tag and Gag10–30. The localization of the GFP fluorescence is indicated for strains with wild-type nup124 (WT) and with nup124-1. (B) Localization of fusion proteins that contained Gag10–30. Strains that had wild-type nup124 or nup124-1 alleles expressed the fusion proteins FLAG-(Gag10–30)-GFP-LacZ or SV40 NLS-(Gag10–30)-GFP-LacZ. The localization of the reporter was detected as green GFP signals. The positions of nuclei were indicated by staining of DNA with Hoechst dye. Bar, 10 μm.

The ability of Gag residues 10 to 30 to function with a heterologous NLS was further tested in the context of the transposon by replacing the NLS in residues 1 to 10 of Gag with the SV40 NLS. The resulting version of Tf1 possessed wild-type levels of transposition activity, and this activity retained its dependence on Nup124p (Fig. 8). Taken together, these results indicate that residues 10 to 30 of Gag can modify the function of an adjacent NLS by imposing a requirement for Nup124p on nuclear import.

FIG. 8.

A version of Tf1 with the NLS of SV40 possessed high levels of transposition activity. The NLS of Tf1 Gag was replaced with the NLS of SV40, and the resulting transposon was tested for transposition activity. The level of growth of each strain on medium containing G418 corresponded to the transposition activity of each element. Top row, three control strains were the wild-type strain (WT) containing either the wild-type Tf1-neoAI assay plasmid (YHL1282) or Tf1-neoAI with a frameshift (fs) created either in IN (YHL1554) or in PR (YHL1836) of Tf1. Second row, four independent transformants of Tf1(SV40 NLS)-neo in a strain with nup124+. Third row, four independent transformants of Tf1(SV40 NLS)-neo in a strain with nup124-1. Bottom row, four independent transformants of wild-type Tf1-neo in a strain with nup124-1.

DISCUSSION

Identification of multiple NLSs within the Gag protein of Tf1.

The transport of retroelement material across the nuclear membrane is a critical step that precedes the integration of these elements into the host genome. The question of how Tf1 enters the nucleus is especially interesting because in yeasts the NE remains intact during mitosis (26). We reported previously that the Tf1 element imports its material into the nucleus by a unique mechanism that has a requirement for the nuclear pore factor Nup124p (3). In this report, we investigated the nuclear import of the Gag protein particularly because of our interest in understanding this unusual dependence on the nuclear pore factor Nup124p (3). The examination of different portions of Gag for their ability to localize GFP-LacZ in the nucleus identified two distinct domains with NLS activity. These two karyophilic regions consisted of 50 amino acid residues and were located at the amino and carboxyl termini of Gag. Furthermore, by conducting a computer-based search, we identified within the C-terminal karyophilic domain two putative NLSs with high similarity to the pattern 4 type of the classical NLS found in the T antigen of SV40. This type of NLS is composed of four basic amino acids (K or R) or composed of three basic amino acids (K or R) and either H or P. By making point mutations within these NLSs, we showed that the basic residues were critical for their NLS activity. However, we were surprised that the NLS activity in the C-terminal domain was dispensable for Tf1 transposition. One formal possibility is that the transposition assay we developed in the laboratory could in some way bypass the need for the NLSs that would ordinarily be required in nature. It is also possible that these C-terminal NLSs are folded into particle structures that are not accessible to transport factors.

An extensive analysis of mutagenized proteins demonstrated that the NLS activity of the N-terminal domain of Gag was contained within a short amino acid sequence in the first 10 residues. This sequence included a stretch of four residues (KRIR) with high similarity to the pattern 4 NLS. Further mutational analysis demonstrated that the basic residues of the N-terminal NLS of Gag were critical for NLS activity. Despite the high degree of similarity to pattern 4 NLSs, the PSORT program (GenomeNet) that we used to identify potential NLSs failed to recognize this NLS at the N terminus of Gag due to the presence of the isoleucine.

In this report, we presented several lines of evidence that support a critical role for the NLS activity in the N terminus of Gag in the process of Tf1 retrotransposition. First, the amino acids containing the NLS activity of Gag(1-50)-GFP-LacZ were required for the nuclear localization of Gag as expressed by the intact transposon. We further showed that this mislocalization of Gag in the cytoplasm strictly correlated with a defect in Tf1 retrotransposition. Second, this NLS-less mutant of Tf1 produced mature proteins, underwent proteolytic processing, assembled virus-like particles, and completed reverse transcription. These results are consistent with a specific defect in a late step of the retrotransposition process, such as transport into the nucleus. Third, the absence of the N-terminal NLS of Gag was also found to impair the nuclear localization of Tf1 cDNA, as demonstrated by the cDNA recombination assay. This finding strongly suggests an important role for this NLS in the process of nuclear uptake of Tf1 cDNA. Furthermore, since our previous studies demonstrated that the Gag protein, together with cDNA and other Tf1 proteins, forms a large macromolecular structure or VLPs (28, 31), the absence of the NLS in the N terminus of Gag likely inhibited the import of the intact Tf1 VLPs or PICs. Taken together, these findings suggest a critical role for the NLS activity of the N terminus of Gag in the mechanism that governs the nuclear import of Tf1.

The importance of the NLS in the N terminus of Gag indicated that the NLS in the C terminus lacked the ability to support nuclear import of Gag or cDNA. This is consistent with the possibility that the NLS sequences in the C terminus are folded into the particle structure and are not accessible to transport factors. However, the contribution that Tf1 Gag makes to nuclear import was not surprising in that Gag protein is the major component of Tf1 VLPs (2, 28, 31). Because of its presumed location at the surface of VLPs, Gag proteins represent an accessible target for recognition by the import machinery of the host cell.

The presence of NLSs within capsid proteins is a feature of several viruses. One example is the localization of newly synthesized Gag proteins in the nucleus of cells infected with foamy virus. It was subsequently shown that the Gag protein of foamy virus contains an NLS and that this sequence results in localization of nascent Gag in the nucleus (45, 53). However, deletion of the NLS does not abrogate replication in vitro (53). As a result, the role of this NLS in the life cycle of foamy virus may be redundant with another NLS. The matrix protein (MA) of HIV-1 is another example of a Gag sequence that contains an NLS (6, 15, 21, 49). Together with HIV IN and Vpr, the matrix protein of HIV-1 has been identified as a potential mediator of the nuclear localization of the PIC (6, 15, 49). One possibility may be that the NLS present within the HIV-MA protein plays a role in transporting components of the PIC into the nucleus. However, the precise contribution of HIV-MA to the import of PICs remains unclear because others find that the NLS in MA is not required for the propagation of HIV (10–12, 21).

The requirement of Nup124p for nuclear localization of Tf1.

The FXFG repeats of the type present in Nup124p have been proposed to play a role in mediating the docking of the transport receptors known as importins or karyopherins to the NPCs. Nup124p is unique in that it has been shown to possess a specific activity that is required for the nuclear localization of Tf1 material and not other proteins tested (3). Interestingly, we found that an N-terminal domain of Gag was sufficient to reconstitute the requirement of Nup124p for nuclear import. Further analysis of peptides fused to GFP-LacZ revealed the surprising result that the residues of Gag with the NLS activity were independent from the residues that conveyed the requirement for Nup124p. The ability of residues 10 to 30 of Gag to impose Nup124p dependence on a heterologous NLS was demonstrated with a protein that had the SV40 NLS followed by Gag(10-30)-GFP-LacZ. The ability of residues in Gag to impose the requirement of Nup124p on a heterologous NLS was also demonstrated in the context of the intact transposon. A version of Tf1 with the SV40 NLS in place of the NLS in residues 1 to 10 had wild-type transposition activity that retained its requirement for Nup124p. Within the context of the current understanding of nuclear import, NLSs are known to serve as interaction sites for importins. Our results include the important and novel finding that an NLS and its associated residues can direct nuclear import through a specific pathway that is dependent on a particular factor of the nuclear pore.

The dependence on Nup124p for nuclear import of Gag is contained entirely within a short amino acid sequence. The critical question is, how does Nup124p contribute to the import of Gag in a specific manner? If FXFG repeats play an important role in docking the importins associated with substrates of nuclear transport, why did the truncation of the last seven FXFGs caused by the mutation in nup124-1 specifically block the nuclear import of Gag but not that of other proteins (3)? Two models for the specific requirement of Nup124p are schematically presented in Fig. 9. In general, NLS-containing cargo must be recognized by and bound to importins to be carried to the NPC (17, 46). Eukaryotic cells contain many classes of importins that are specific for different subclasses of substrates, and since Nup124p appears to be specifically required for the import of Gag, one possibility is that Gag has to interact with specific importins in order to be carried to the NPC (Fig. 9A). The interaction between this complex and a specific FXFG nuclear pore factor like Nup124p would be necessary to explain the specific role of Nup124p in the import of Gag. In addition, the residues of Gag that cause the requirement for Nup124p may be responsible for targeting Gag to specific importins. One example of a nuclear pore factor that serves as a docking site for a specific importin has been reported. Kap121p of S. cerevisiae serves as the only beta importin that binds Nup53p (35). It becomes obvious that one of the priorities in future experiments will be to identify the importins that are needed for the nuclear entry of Tf1 material.

FIG. 9.

Two possible mechanisms for the nuclear import of Gag. (A) In general, cargo to be imported interacts with the transport receptors, importins. Since Nup124p appears to be specifically required for the import of Gag, we propose that Gag interacts with specific importins to be carried to the nuclear pore. The interaction between this complex and a specific FXFG nuclear pore factor, Nup124p, could be required for translocation. (B) Alternatively, we propose that Gag may interact directly with Nup124p and that this interaction is required for the subsequent translocation. We have reported such an interaction and proposed that it is responsible for the specific function of Nup124p that is required for Tf1 import (3).

An alternative model is that Gag may interact directly with Nup124p, and this interaction is required for the subsequent translocation (Fig. 9B). This model is supported by the previous finding that Gag can interact directly with the N terminus of Nup124p as observed in our studies using yeast two-hybrid analysis and in vitro coprecipitation techniques (3). It is possible that Gag contributes to the import of the Tf1 PICs by causing a direct interaction with Nup124p that results in the specific requirement of Nup124p for transposition. Residues 10 to 30 of Gag may play an important role in the interaction between Gag and Nup124p. The import activity in Gag(1-20)-GFP-LacZ of Gag that was independent of Nup124p may reflect a conventional pathway of import that could serve as a backup when residues 20 to 30 of Gag are removed. Future experiments will be conducted to identify which residues are responsible for the interaction between Nup124p and Gag and whether these residues are necessary for transposition. It is, however, necessary to emphasize that the two models presented in Fig. 9 are not mutually exclusive. One could imagine that interactions of Gag with both importins and nuclear pore factors are required for its nuclear import. Gag may therefore play a key role in Tf1 import by mediating the interactions between the transport receptors and the nuclear pore factors.

The unusual role of Gag in the nuclear import of Tf1 is surprisingly similar to the function of the accessory protein Vpr of HIV-1 in the nuclear import of HIV PICs. Although the MA and IN proteins also carry conventional NLSs and probably utilize the importin pathway for nuclear import (13, 14), many recent studies strongly suggest that Vpr plays a unique role in the nuclear import of the HIV-1 proteins (9, 23, 40, 48). First, Vpr possesses karyophilic properties that contribute significantly to the infection of nondividing cells (14, 48). Second, Vpr has been observed to localize at the nuclear envelope of yeast and human cells, and this behavior is thought to lead to the import of PICs (9, 48). Evidence for this model includes the finding that Vpr is a component of the PIC and interacts with FXFG repeat nuclear pore proteins (16, 21, 48). Indeed, Vpr was recently found to interact directly with pom121, a nuclear pore factor that contains FXFG repeats (9). This result suggests that Vpr may contribute to the import of HIV PICs by causing a direct interaction between the PIC and FXFG-containing factors in the NPC. Consistent with this model is the finding that Vpr uses an import pathway distinct from classical NLS or M9 substrates that is independent of Ran-mediated GTP hydrolysis (23). The similarity between Tf1 Gag import and HIV Vpr nuclear uptake suggests that large viral complexes may require direct contacts with FXFG proteins in order to successfully navigate through the NPC. In addition, our result that the nuclear import of a virus-like protein can be inhibited without affecting the import of other proteins suggests that the reduction of nuclear import may prove to be an effective strategy for antiviral therapies.

REFERENCES

- 1.Atwood A, Choi J, Levin H L. The application of a homologous recombination assay revealed amino acid residues in an LTR-retrotransposon that were critical for integration. J Virol. 1998;72:1324–1333. doi: 10.1128/jvi.72.2.1324-1333.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Atwood A, Lin J, Levin H. The retrotransposon Tf1 assembles virus-like particles with excess Gag relative to integrase because of a regulated degradation process. Mol Cell Biol. 1996;16:338–346. doi: 10.1128/mcb.16.1.338. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Balasundaram D, Benedik M J, Morphew M, Dang V D, Levin H L. Nup124p is a nuclear pore factor of Schizosaccharomyces pombe that is important for nuclear import and activity of retrotransposon Tf1. Mol Cell Biol. 1999;19:5768–5784. doi: 10.1128/mcb.19.8.5768. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Boeke J D, Stoye J P. Retrotransposons, endogenous retroviruses, and the evolution of retroelements. Plainview, N.Y: Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press; 1997. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Boeke J D, Trueheart J, Natsoulis G, Fink G R. 5-Fluoro-orotic acid as a selective agent in yeast molecular genetics. Methods Enzymol. 1987;154:164–175. doi: 10.1016/0076-6879(87)54076-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bukrinsky M I, Haggerty S, Dempsey M P, Sharova N, Adzhubel A, Spitz L, Lewis P, Goldfarb D, Emerman M, Stevenson M. A nuclear localization signal within HIV-1 matrix protein that governs infection of non-dividing cells. Nature. 1993;365:666–669. doi: 10.1038/365666a0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bukrinsky M I, Sharova N, Dempsey M P, Stanwick T L, Bukrinskaya A G, Haggerty S, Stevenson M. Active nuclear import of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 preintegration complexes. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1992;89:6580–6584. doi: 10.1073/pnas.89.14.6580. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Dang V D, Benedik M J, Ekwall K, Choi J, Allshire R C, Levin H L. A new member of the sin3 family of corepressors is essential for cell viability and required for retroelement propagation in fission yeast. Mol Cell Biol. 1999;19:2351–2365. doi: 10.1128/mcb.19.3.2351. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Fouchier R, Meyer B, Simon J, Fischer U, Albright A, González-Scarano F, Malim M. Interaction of the human immunodeficiency virus type 1 Vpr protein with the nuclear pore complex. J Virol. 1998;72:6004–6013. doi: 10.1128/jvi.72.7.6004-6013.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Fouchier R A, Meyer B E, Simon J H, Fischer U, Malim M H. HIV-1 infection of non-dividing cells: evidence that the amino-terminal basic region of the viral matrix protein is important for Gag processing but not for post-entry nuclear import. EMBO J. 1997;16:4531–4539. doi: 10.1093/emboj/16.15.4531. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Freed E O, Englund G, Maldarelli F, Martin M A. Phosphorylation of residue 131 of HIV-1 matrix is not required for macrophage infection. Cell. 1997;88:171–174. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81836-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Freed E O, Englund G, Martin M A. Role of the basic domain of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 matrix in macrophage infection. J Virol. 1995;69:3949–3954. doi: 10.1128/jvi.69.6.3949-3954.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gallay P, Hope T, Chin D, Trono D. HIV-1 infection of nondividing cells through the recognition of integrase by the importin/karyopherin pathway. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1997;94:9825–9830. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.18.9825. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gallay P, Stitt V, Mundy C, Oettinger M, Trono D. Role of the karyopherin pathway in human immunodeficiency virus type 1 nuclear import. J Virol. 1996;70:1027–1032. doi: 10.1128/jvi.70.2.1027-1032.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gallay P, Swingler S, Aiken C, Trono D. HIV-1 infection of nondividing cells: C-terminal tyrosine phosphorylation of the viral matrix protein is a key regulator. Cell. 1995;80:379–388. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(95)90488-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gallay P, Swingler S, Song J, Bushman F, Trono D. HIV nuclear import is governed by the phosphotyrosine-mediated binding of matrix to the core domain of integrase. Cell. 1995;83:569–576. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(95)90097-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gorlich D, Kutay U. Transport between the cell nucleus and the cytoplasm. Annu Rev Cell Dev Biol. 1999;15:607–660. doi: 10.1146/annurev.cellbio.15.1.607. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gorlich D, Mattaj I W. Nucleocytoplasmic transport. Science. 1996;271:1513–1518. doi: 10.1126/science.271.5255.1513. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Greber U F, Suomalainen M, Stidwell R P, Boucke K, Ebersold M W, Helenius A. The role of the nuclear pore complex in adenovirus DNA entry. EMBO J. 1997;16:5998–6007. doi: 10.1093/emboj/16.19.5998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Haase A T. Pathogenesis of lentivirus infections. Nature. 1986;322:130–136. doi: 10.1038/322130a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Heinzinger N K, Bukinsky M I, Haggerty S A, Ragland A M, Kewalramani V, Lee M A, Gendelman H E, Ratner L, Stevenson M, Emerman M. The Vpr protein of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 influences nuclear localization of viral nucleic acids in nondividing host cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1994;91:7311–7315. doi: 10.1073/pnas.91.15.7311. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hicks G R, Raikhel N V. Protein import into the nucleus: an integrated view. Annu Rev Cell Dev Biol. 1995;11:155–188. doi: 10.1146/annurev.cb.11.110195.001103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Jenkins Y, McEntee M, Weis K, Greene W C. Characterization of HIV-1 vpr nuclear import: analysis of signals and pathways. J Cell Biol. 1998;143:875–885. doi: 10.1083/jcb.143.4.875. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Joyce C M, Grindley N. Method for determining whether a gene of Escherichia coli is essential: application to the polA gene. J Bacteriol. 1984;158:636–643. doi: 10.1128/jb.158.2.636-643.1984. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kasamatsu H, Nakanishi A. How do animal DNA viruses get to the nucleus? Annu Rev Microbiol. 1998;52:627–686. doi: 10.1146/annurev.micro.52.1.627. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kubai D F. The evolution of the mitotic spindle. Int Rev Cytol. 1975;43:167–227. doi: 10.1016/s0074-7696(08)60069-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kukolj G, Katz R A, Skalka A M. Characterization of the nuclear localization signal in the avian sarcoma virus integrase. Gene. 1998;223:157–163. doi: 10.1016/s0378-1119(98)00169-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Levin H L. A novel mechanism of self-primed reverse transcription defines a new family of retroelements. Mol Cell Biol. 1995;15:3310–3317. doi: 10.1128/mcb.15.6.3310. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Levin H L. An unusual mechanism of self-primed reverse transcription requires the RNase H domain of reverse transcriptase to cleave an RNA duplex. Mol Cell Biol. 1996;16:5645–5654. doi: 10.1128/mcb.16.10.5645. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Levin H L, Boeke J D. Demonstration of retrotransposition of the Tf1 element in fission yeast. EMBO J. 1992;11:1145–1153. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1992.tb05155.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Levin H L, Weaver D C, Boeke J D. Novel gene expression mechanism in a fission yeast retroelement: Tf1 proteins are derived from a single primary translation product. EMBO J. 1993;12:4885–4895. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1993.tb06178.x. . (Erratum, 13:1494, 1994.) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Levin H L, Weaver D C, Boeke J D. Two related families of retrotransposons from Schizosaccharomyces pombe. Mol Cell Biol. 1990;10:6791–6798. doi: 10.1128/mcb.10.12.6791. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Lewis P, Hensel M, Emerman M. Human immunodeficiency virus infection of cells arrested in the cell cycle. EMBO J. 1992;11:3053–3058. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1992.tb05376.x. . (Erratum, 11:4249.) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Lin J H, Levin H L. A complex structure in the mRNA of Tf1 is recognized and cleaved to generate the primer of reverse transcription. Genes Dev. 1997;11:270–285. doi: 10.1101/gad.11.2.270. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Marelli M, Aitchison J D, Wozniak R W. Specific binding of the karyopherin Kap121p to a subunit of the nuclear pore complex containing Nup53p, Nup59p, and Nup170p. J Cell Biol. 1998;143:1813–1830. doi: 10.1083/jcb.143.7.1813. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Moreno S, Klar A, Nurse P. Molecular genetic analysis of fission yeast Schizosaccharomyces pombe. Methods Enzymol. 1991;194:795–823. doi: 10.1016/0076-6879(91)94059-l. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Nakanishi A, Clever J, Yamada M, Li P P, Kasamatsu H. Association with capsid proteins promotes nuclear targeting of simian virus 40 DNA. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1996;93:96–100. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.1.96. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Narayan O, Clements J E. Biology and pathogenesis of lentiviruses. J Gen Virol. 1989;70:1617–1639. doi: 10.1099/0022-1317-70-7-1617. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Passion S G, Forsburg S L. Nuclear localization of S. pombe Mcm2/Cdc19p requires MCM complex assembly. Mol Biol Cell. 1999;10:4043–4057. doi: 10.1091/mbc.10.12.4043. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Popov S, Rexach M, Zybarth G, Reiling N, Lee M A, Ratner L, Lane C M, Moore M S, Blobel G, Bukrinsky M. Viral protein R regulates nuclear import of the HIV-1 pre-integration complex. EMBO J. 1998;17:909–917. doi: 10.1093/emboj/17.4.909. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Reichelt R, Holzenburg A, Buhle E L, Jr, Jarnik M, Engel A, Aebi U. Correlation between structure and mass distribution of the nuclear pore complex and of distinct pore complex components. J Cell Biol. 1990;110:883–894. doi: 10.1083/jcb.110.4.883. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Roe T, Reynolds T C, Yu G, Brown P O. Integration of murine leukemia virus DNA depends on mitosis. EMBO J. 1993;12:2099–2108. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1993.tb05858.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Rose M D, Winston F, Hieter P. Methods in yeast genetics: a laboratory course manual. Cold Spring Harbor, N.Y: Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory; 1990. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Rout M P, Aitchison J D, Suprapto A, Hjertaas K, Zhao Y M, Chait B T. The yeast nuclear pore complex: composition, architecture, and transport mechanism. Cell Biol. 2000;148:635–651. doi: 10.1083/jcb.148.4.635. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Schliephake A W, Rethwilm A. Nuclear localization of foamy virus Gag precursor protein. J Virol. 1994;68:4946–4954. doi: 10.1128/jvi.68.8.4946-4954.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Stoffler D, Fahrenkrog B, Aebi U. The nuclear pore complex: from molecular architecture to functional dynamics. Curr Opin Cell Biol. 1999;11:391–401. doi: 10.1016/S0955-0674(99)80055-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Towbin H, Staehelin T, Gordon J. Electrophoretic transfer of proteins from polyacrylamide gels to nitrocellulose sheets: procedure and some applications. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1979;76:4350–4354. doi: 10.1073/pnas.76.9.4350. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Vodicka M A, Koepp D M, Silver P A, Emerman M. HIV-1 Vpr interacts with the nuclear transport pathway to promote macrophage infection. Genes Dev. 1998;12:175–185. doi: 10.1101/gad.12.2.175. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.von Schwedler U, Kornbluth R S, Trono D. The nuclear localization signal of the matrix protein of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 allows the establishment of infection in macrophages and quiescent T lymphocytes. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1994;91:6992–6996. doi: 10.1073/pnas.91.15.6992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Weinberg J B, Matthews T J, Cullen B R, Malim M H. Productive human immunodeficiency virus type 1 (HIV-1) infection of nonproliferating human monocytes. J Exp Med. 1991;174:1477–1482. doi: 10.1084/jem.174.6.1477. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Yamada M, Kasamatsu H. Role of nuclear pore complex in simian virus 40 nuclear targeting. J Virol. 1993;67:119–130. doi: 10.1128/jvi.67.1.119-130.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Yang Q, Rout M P, Akey C W. Three-dimensional architecture of the isolated yeast nuclear pore complex: functional and evolutionary implications. Mol Cell. 1998;1:223–234. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(00)80023-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Yu S F, Edelmann K, Strong R K, Moebes A, Rethwilm A, Linial M L. The carboxyl terminus of the human foamy virus Gag protein contains separable nucleic acid binding and nuclear transport domains. J Virol. 1996;70:8255–8262. doi: 10.1128/jvi.70.12.8255-8262.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]