Abstract

Hidradenitis suppurativa and steatocystoma multiplex may coexist in the same patient. The overlap of these 2 conditions could be suggestive of an unrecognized defect in follicular proliferation mutual in the pathogenesis of both conditions. Here we present 5 patients with both hidradenitis suppurativa and steatocystoma multiplex. Recognizing the overlap between these 2 conditions is important for accurate diagnosis, management, and identification of potential surgical candidates, as well as future basic science research.

Keywords: dermatology, inflammatory dermatoses

Introduction

Hidradenitis suppurative (HS) is a chronic, inflammatory, recurrent disease affecting the folliculopilosebaceous unit in the apocrine gland-bearing areas. This leads to comedones, nodules, abscesses, sinus tracts, and scarring. 1 HS usually presents in a sporadic or familial fashion, but rare syndromic forms recognizable for their unique symptomatology have been described in the literature. 2 Syndromic forms of HS are linked to a spectrum of conditions, ranging from keratin mutations to autoinflammatory syndromes.

Steatocystoma multiplex (SM) is an uncommon autosomal dominant or sporadic disorder affecting the pilosebaceous unit, presenting as multiple skin-colored to yellowish firm or cystic papules or nodules. Cysts range in size from a few millimeters to several centimeters and predominantly occur in the axilla, trunk, and limbs. 3 -6 SM rarely affects the face or scalp, but variants in these areas do exist. 6 The onset of SM is centered around puberty, coinciding with the associated increase in pilosebaceous gland activity. 7

The term steatocystoma multiplex suppurativa (SMS) and steatocystoma multiplex conglobatum are terms used as synonymously to describe a rare form of SM where cysts frequently become inflamed and rupture, leading to scarring. 7 Secondary bacterial infection is possible, leading to malodourous discharge and possible abscess formation. 8,9 SM can rarely transform into SMS at any point in its natural history, mimicking both hidradenitis suppurativa and acne conglobata. 4,10

The overlap of HS and SM, or SMS, could be suggestive of an unrecognized defect in follicular proliferation common to both diseases or a mutual genetic link. Recognizing this overlap is important for an accurate diagnosis, management and identification of potential surgical candidates, as well as future basic science research. In this paper we present five patients with concurrent hidradenitis suppurativa and steatocystoma multiplex.

Case Reports

We present five cases of individuals with overlap of hidradenitis suppurativa and steatocystoma multiplex. Four patients were female, and one was male, and ages ranged from 20 to 40-years-old. All were diagnosed with HS between 14 and 20-years-old prior to onset of SM. Clinical characteristics are summarized in Table 1.

Table 1.

Clinical Characteristics of 5 Patients Presenting With Hidradenitis Suppurativa and Steatocystoma Multiplex. (Normal BMI 18.5-24.9).

| Age/Sex | PMH/FH Smoking status |

HS—Age at onset—Hurley stage | Previous treatments a | Elements of follicular tetrad | Cyst location— Onset | BMI | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Case 1 | 20/F | No relevant Non smoker |

15 yo – Stage I | Oral antibiotics | None | Axillae, pubic 19yo |

Normal |

| Case 2 | 31/F | No relevant Non smoker |

15 yo – Stage I | OCPs, I&D, homeopathic therapy, OTC oils | None | Axillae, left

suprapubic 26yo |

Normal |

| Case 3 | 40/F | No relevant Non smoker |

20 yo – Stage I | Topical dapsone, BPO wash, topical antibiotic | None | Axillae 39yo |

Normal |

| Case 4 | 35/F | No relevant Non smoker |

16 yo – Stage I | None | None | Axillae 30yo |

Normal |

| Case 5 | 20/M | No relevant Non smoker |

14 yo – Stage I | Unknown | Unknown | Generalized 15yo |

Normal |

Abbreviations: BMI, body mass index; BPO, benzoyl peroxide; F, female; FH, Family History; I&D, incision and drainage; M, male; OCP, oral contraceptive pill; OTC, over the counter; PMH, Past Medical History; YO, years old.

aTreatments done in primary care settings.

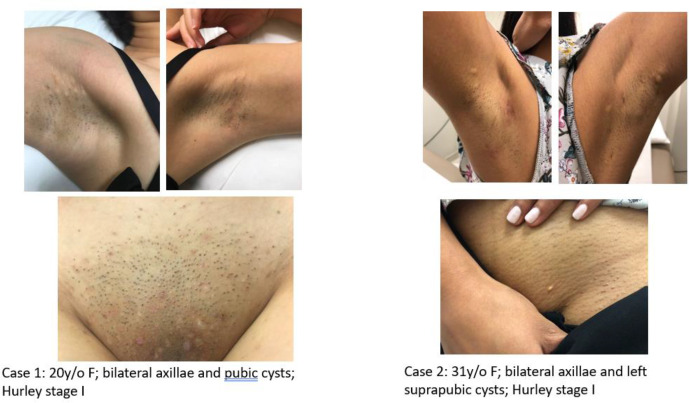

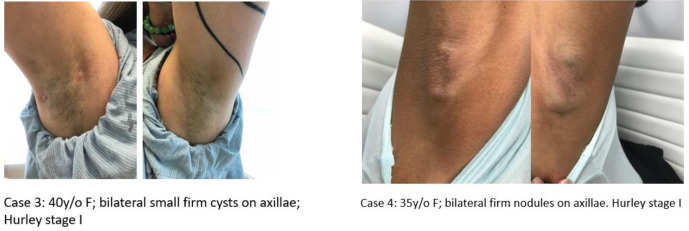

The cases presented with persistent cystic lesions in bilateral axillae with intermittent episodes of red inflamed nodules and drainage. On physical exam, one patient had multiple pubic cysts, while another patient had only a small white cyst on the left pubic area (Figure 1). The male case with the condition had widespread white papules of SM and also cystic acne in addition to HS. All 4 patients had firm whitish cysts in both axillae with evidence of inflammatory nodules, tracts, and scarring (Figure 2). The HS lesions showed different degrees of inflammation.

Figure 1.

Cases 1 and 2 presenting with bilateral axillary and pubic whitish papules and cysts, both Hurley stage 1.

Figure 2.

Cases 3 and 4 presenting with multiple bilateral axillary firm whitish cysts, both Hurley stage 1. Cysts were larger in case 4.

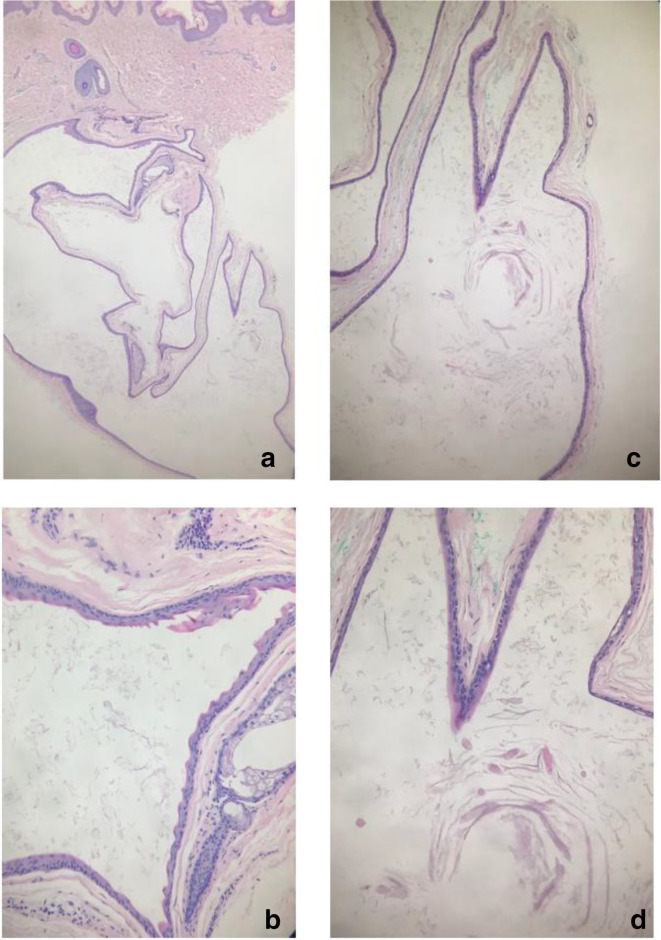

Histopathology from case 1 is presented here and showed a thin stratified squamous epithelium, with no granular layer and surrounded by a thin irregular corrugated eosinophilic cuticle (Figure 3). Treatment offered included oral and topical antibiotics for inflammatory lesions. Surgical treatment of cystic lesions was offered to patients for cosmetic purposes.

Figure 3.

Histopathological findings of a cyst from case 1. (a) H&E, 2 x. (b) Corrugated cuticular lining, 10 x . (c and d) Loose wispy keratin content with some vellus hairs, 2× and 10× respectively.

Discussion

There are a few reports presenting the coexistence of these 2 conditions. The first case report describing patients with both SM and HS was published in 1976. It was thought at the time that HS was likely a coincidental complication, but a possible inherited syndrome involving inflammation of steatocystoma was postulated. 11 Previous case reports have also demonstrated the coexistence of HS and SM within families. 3

The etiopathogenesis of HS is not yet fully understood, however follicular occlusion seems to be an essential event. Promoting factors include gamma (γ) secretase mutations, impaired Notch signaling, and abnormal cytokines among others. 2 It is believed that γ-secretase is a key regulator of the Notch signaling pathway, and mutations here are thought to lead to epidermal and follicular abnormalities, including formation of epidermal cysts. 12,13

The overlap of these 2 conditions could be suggestive of an unrecognized common defect in follicular proliferation. Mutations in keratin 17 (KRT17), a gene encoding the type 1 intermediate filament chain keratin 17 found in sebaceous glands, hair follicles, and other epidermal appendages, have been identified in patients with SM as well as patients with paronychia congenita type 2 (PC-2) 5,14 PC2 is an autosomal dominant disorder associated with nail dystrophy, palmoplantar keratoderma, follicular keratosis, and epidermal inclusion cysts. 4 The presence of the KRT17 mutation in both of these clinical entities is suggestive of different phenotypic expressions.

Genetic defects believed to be associated with epidermal and follicular abnormalities are also seen in Dowling-Degos disease (DDD), a rare autosomal dominant disorder characterized by reticular hyperpigmentation of the folds and occasionally associated with HS. 15 DDD is linked to mutations in keratin 5, as well as POFUT1 and POGLUT1 (both regulators of the Notch pathway). 12 Both DDD and HS are also associated with mutations in the PSENEN gene, which encodes a component of the γ-secretase complex. This supports the hypothesis that this defect is related to epithelial and follicular proliferation, ultimately leading to occlusion and inflammation. 12,13,15 -17

Given its similarity to HS both in location and presentation, a diagnosis of SM can often be overlooked and initially missed. Histopathologic examination is therefore crucial to determining the correct diagnosis. 9,18 Typical histological findings of SM include either round/oval or intricately folded cysts with a flattened squamous epithelium, the majority of which had sebaceous lobules within or adjacent to the cyst wall. In addition, wavy eosinophilic cuticles with the absence of a granular layer are present. 18 Ultrasonography with color doppler has also previously been reported as a non-invasive tool to help differentiate HS and SM. 5

Management strategies for SM and SMS include local destructive methods (cryotherapy, CO2 and Erbium YAG), oral medications (antibiotics, isotretinoin), and surgery of symptomatic lesions. 4,7,8 Isotretinoin was commonly used in the literature for SMS, helping to control the size of suppurative lesions, likely due to its anti-inflammatory effect. 4,7,8

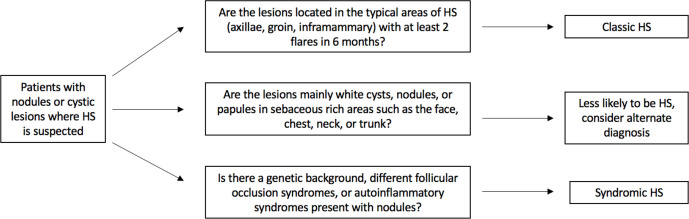

Given the possible similarities between these 2 conditions, we suggest the approach outlined in Figure 4 when suspecting a diagnosis of HS in patients with nodules or cystic lesions. When assessing a patient with nodules and suppurative lesions, the clinician should also examine for signs suggestive of a syndromic diagnosis, some of which are listed in Table 2. Examples of such signs include pigmented areas, hypertrichosis, atrophoderma, and other cutaneous tumors. Genetic and histopathologic analysis can also aid in diagnosis and help classify patients.

Figure 4.

Approach to patients with nodular or cystic lesions where hidradenitis suppurativa is suspected.

Table 2.

Syndromes Associated With Hidradenitis Suppurativa.

| Classification | Syndrome | Clinical presentation |

|---|---|---|

| Syndromes with a genetic background | Bazex-Dupre-Christol Syndrome | Follicular atrophoderma, congenital hypertrichosis, basal cell neoformations 19 |

| Dowling-Degos disease | Reticular hyperpigmentation of flexural surfaces, comedo-like lesions, perioral or facial scars, epidermoid cysts 20 | |

| Down’s Syndrome | HS over 5 times more likely in this population, HS diagnosed earlier in life 21 | |

| Keratitis-Ichthyosis-Deafness Syndrome | Erythrokeratoderma, follicular keratoses, palmoplantar hyperkeratosis, alopecia 22 | |

| Familial Mediterranean Fever | Fever, peritonitis, arthritis, amyloidosis 23 | |

| Syndromes with follicular plugging or structural disorders | Bazex-Dupre-Christol Syndrome | Follicular atrophoderma, congenital hypertrichosis, basal cell neoformations 19 |

| Dowling-Degos disease | Reticular hyperpigmentation of flexural surfaces, comedo-like lesions, perioral or facial scars, epidermoid cysts 20 | |

| Down’s Syndrome | HS over 5 times more likely in this population, HS diagnosed earlier in life 21 | |

| Keratitis-Ichthyosis-Deafness Syndrome | Erythrokeratoderma, follicular keratoses, palmoplantar hyperkeratosis, alopecia 22 | |

| Follicular Occlusion Syndrome | Acne conglobata, pilonidal disease, dissecting cellulitis, HS | |

| Syndromes with a possible autoinflammatory pathogenesis | PASH | Pyoderma Gangrenosum, Acne, Suppurative Hidradenitis |

| PASS | Pyoderma Gangrenosum, Acne, HS, Ankylosing Spondylitis | |

| PAPASH | Pyogenic Arthritis, Pyoderma Gangrenosum, Acne, HS | |

| SAPHO | Synovitis, Acne, Pustulosis, Hyperostosis, Osteitis | |

| Familial Mediterranean

Fever (FMF) |

Fever, peritonitis, arthritis, amyloidosis 23 |

Our case series further supports the growing body of literature demonstrating an overlap between hidradenitis suppurativa and steatocystoma multiplex. This is a new variant of HS, but further genetic studies are needed to identify if there is a genetic link. We also suggest an approach to patients presenting with nodules or cystic lesions when HS is suspected. Overall, further basic science and genetic research is needed in order to elucidate a possible follicular pathway between SM, HS, and other follicular occlusion syndromes.

Footnotes

Poster presentation at the World Congress of Dermatology.

Declaration of Conflicting Interests: The author(s) declared the following potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: AA has acted as a consultant, advisor, and/or received research funding from Abbvie, Galderma, Janssen, LEO Pharma, Novartis, Sanofi Aventis, Valeant, Boehringer-Ingelheim, DSBiopharma, Eli Lilly, Glenmark, Incyte, Ilkos, Merck Serono, Pfizer, Regeneron, Roche, Xenon, Kymea, Kyowa and Xoma.

Funding: The author(s) received no financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

ORCID iDs

Joshua Fletcher https://orcid.org/0000-0002-1501-8401

Afsaneh Alavi https://orcid.org/0000-0003-1171-4917

References

- 1. Zouboulis CC., Desai N., Emtestam L. et al. European S1 guideline for the treatment of hidradenitis suppurativa/acne inversa. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2015;29(4):619-644. 10.1111/jdv.12966 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Gasparic J., Theut Riis P., Jemec GB. Recognizing syndromic hidradenitis suppurativa: a review of the literature. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2017;31(11):1809-1816. 10.1111/jdv.14464 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Hollmig T., Menter A. Familial coincidence of hidradenitis suppurativa and steatocystoma multiplex. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2010;35(4):e151-e152. 10.1111/j.1365-2230.2009.03742.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Santana CN., Pereira DD., Lisboa AP., Leal JM., Obadia DL., Silva RS. Steatocystoma multiplex suppurativa: case report of a rare condition. An Bras Dermatol. 2016;91(5 suppl 1):51-53. 10.1590/abd1806-4841.20164539 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Zussino M., Nazzaro G., Moltrasio C., Marzano AV., Marzano AV. Coexistence of steatocystoma multiplex and hidradenitis suppurativa: assessment of this unique association by means of ultrasonography and color Doppler. Skin Res Technol. 2019;25(6):1-4. 10.1111/srt.12751 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Alotaibi L., Alsaif M., Alhumidi A., Turkmani M., Alsaif F. Steatocystoma multiplex suppurativa: a case with unusual giant cysts over the scalp and neck. Case Rep Dermatol. 2019;11(1):71-76. 10.1159/000498882 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Adams B., Shwayder T. Steatocystoma multiplex suppurativum. Int J Dermatol. 2008;47(11):1155-1156. 10.1111/j.1365-4632.2008.03698.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Apaydin R., Bilen N., Bayramgürler D., Başdaş F., Harova G., Dökmeci S. Steatocystoma multiplex suppurativum: oral isotretinoin treatment combined with cryotherapy. Australas J Dermatol. 2000;41(2):98-100. 10.1046/j.1440-0960.2000.00403.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Monteiro A., Rato M., Tavares E. Inherited steatocystoma multiplex suppurativa. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2018;6550. 10.1016/j.jaad.2018.05.689 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Scheinfeld N. Diseases associated with hidranitis suppurativa: Part 2 of a series on hidradenitis. Dermatol Online J. 2013;19(6): [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. McDonald RM., Reed WB. Natal teeth and steatocystoma multiplex complicated by hidradenitis suppurativa. A new syndrome. Arch Dermatol. 1976;112(8):1132-1139. 10.1001/archderm.1976.01630320038010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Pavlovsky M., Sarig O., Eskin-Schwartz M. et al. A phenotype combining hidradenitis suppurativa with Dowling-Degos disease caused by a founder mutation in PSENEN . Br J Dermatol. 2018;178(2):502-508. 10.1111/bjd.16000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. McGarth J. Concurrent hidradenitis suppurativa and dowling–degos disease taken down a ‘Notch’. Br J Dermatol. 2018;74: 10.1111/bjd.16068 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Covello S., Smith F., Sillevis Smitt J. et al. Keratin 17 mutations cause either steatocystoma multiplex or pachyonychia congenita type 2. Br J Dermatol. 1998;1:475-480. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Agut-Busquet E., de Gabriel J., Pibernat M., Gonzalez A., Moreno J. Dowling-Degos syndrome and hidradenitis suppurativa: An uncommon association with linked pathogenesis? Report of nien cases and review of the literature. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2017;4929 10.1016/j.jaad.2017.04.416 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Bedlow AJ., Mortimer PS., George S., Road B. Dowling-Degos disease associated with hidradenitis suppurativa. Clin Exp Dermatol. 1996;21(4):305-306. 10.1111/j.1365-2230.1996.tb00103.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Loo WJ., Rytina E., Todd PM. Hidradenitis suppurativa, Dowling-Degos and multiple epidermal cysts: a new follicular occlusion triad. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2004;29(6):622-624. 10.1111/j.1365-2230.2004.01631.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Cho S., Chang S-E., Choi J-H., Sung K-J., Moon K-C., Koh J-K. Clinical and histologic features of 64 cases of steatocystoma multiplex. J Dermatol. 2002;29(3):152-156. 10.1111/j.1346-8138.2002.tb00238.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Goeteyn M., Geerts ML., Kint A., De Weert J., De WJ. The Bazex-Dupré-Christol syndrome. Arch Dermatol. 1994;130(3):337-342. 10.1001/archderm.1994.01690030069011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Kim YC., Davis MD., Schanbacher CF., Su WP., disease D-D. Dowling-Degos disease (reticulate pigmented anomaly of the flexures): a clinical and histopathologic study of 6 cases. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1999;40(3):462-467. 10.1016/S0190-9622(99)70498-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Garg A., Strunk A., Midura M., Papagermanos V., Pomerantz H. Prevalence of hidradenitis suppurativa among patients with Down syndrome: a population-based cross-sectional analysis. Br J Dermatol. 2018;178(3):697-703. 10.1111/bjd.15770 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Caceres-Rios H., Tamayo-Sanchez L., Duran-Mckinster C., de la Luz Orozco M., Ruiz-Maldonado R., Keratitis R-MR. Keratitis, ichthyosis, and deafness (kid syndrome): review of the literature and proposal of a new terminology. Pediatr Dermatol. 1996;13(2):105-113. 10.1111/j.1525-1470.1996.tb01414.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Vural S., Gundogdu M., Kundakci N., Ruzicka T. Familial Mediterranean fever patients with hidradenitis suppurativa. Int J Dermatol. 2017;56(6):660-663. 10.1111/ijd.13503 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]