Abstract

Aims and objectives:

Code-switching, the spontaneous switching from one language to another within a single speech event, is often performed by bilinguals who have mastered a communicative competence in two languages. It is also a social strategy – using linguistic cues as a means to index social categories and group solidarity. Code-switching is, therefore, linked to attitudes, seen as a reflection of the speaker and their values and identities. Traditionally perceived negatively, attitudes toward code-switching have been shown to be acceptable in certain cases, such as in multilingual contexts. However, it has yet to be determined empirically whether attitudes toward code-switching are associated with individual social characteristics, including cultural identity and identity negotiation. Adopting the bidimensional model of acculturation, the goal of the study was to investigate the relationships among cultural identity and code-switching attitudes. Specifically, we sought to examine whether the bidimensional framework can be used to characterize and distinguish biculturals and whether such distinctions result in differences in code-switching attitudes and other related factors.

Data and analysis:

Cantonese-English bilinguals (n = 67) reported their language background and completed questionnaires relating to identity and code-switching.

Findings:

The findings suggest the bidimensional model was successful in classifying biculturals versus non-biculturals and, additionally, that biculturals could be differentiated according to their strength of cultural identification, which we designated as strong biculturals, Canadian-oriented biculturals, Chinese-oriented biculturals, and weak biculturals. Findings also revealed significant group differences in code-switching attitudes and other factors, such as code-switching comfort and preference, among the bicultural subgroups.

Implications:

The study supports the hypothesis that code-switching is linked to bicultural identity. The results conclude that a more nuanced classification of biculturals is meaningful, as individual differences in cultural identification among biculturals are linked to significant differences in code-switching comfort, code-switching preference, code-switching attitudes, and multicultural attitudes.

Keywords: Bilingualism, code-switching, cultural identity, ethnic identity, biculturalism, acculturation, individual differences, language attitudes, attitudes

Introduction

Si tu eres Puertorriqueño [if you’re a Puerto Rican], your father’s a Puerto Rican, you should at least de vez en cuando [sometimes], you know, hablar español [speak Spanish]. (Poplack, 1980, p. 594)

Considering the above quote at face value, it is likely that everyone has experienced in one way or another some form of language switching in conversation. Bilingualism is widespread around the world (De Bot, 1992; Grosjean, 1982) and even for monolinguals, it can be commonplace to encounter and hear two languages mixed together in the same sentence or conversation. When bilinguals communicate in both of their languages and switch between them, they are code-switching. This is defined as the spontaneous alternation from one language to another or mixing elements from two languages within a single speech event (Appel & Muysken, 1987).

Despite it being a common way of speaking for many bilinguals (Grosjean, 1982), it has been traditionally and typically linked to negative perceptions of the speaker, and such negative attitudes stem from the community as well as the speakers themselves (Low & Lu, 2006). This may, however, no longer be the case because languages (and hence code-switching) co-exist differently in each speech community. It is, therefore, possible that some language communities consider code-switching to be acceptable, and perhaps even an asset. While much research has documented the negative perception and stigma attached to code-switching, few studies have reported on its attitudinal dimensions (Lawson & Sachdev, 2000). The present study, therefore, seeks to examine attitudes toward code-switching as it pertains to individual characteristics in a multilingual Canadian context. Furthermore, referring to the content of Poplack’s quote above, we specifically investigate the relationships among existing code-switching attitudes and individual differences in cultural identification.

Code-switching

There is no consensus as to what criteria determine that someone is bilingual. Psycholinguists have defined bilinguals as individuals who can operate in each language and alternately use both languages (i.e. distinct from language learners; Grosjean, 1998; Weinreich, 1953). Those who code-switch are able to manipulate their languages and use them together because they have developed a communicative competence in both their languages, in contrast to the language interference experienced by language learners (Woolard, 1998). As mentioned above, they are, however, also often viewed as having an incomplete knowledge of either of their languages. This view stems from the misconception that code-switching is a compensatory strategy, derived from the speaker not having adequate language proficiency or a lack of solidarity with the language group. Citing Cantonese-English in Hong Kong as an example, Gibbons (1987) suggested that there are many bilingual “communities in which mixed languages are both disliked and widely used” (p. 145). Similarly, Chana and Romaine (1984) found prominent negative attitudes toward Punjabi-English code-switching in England, despite its frequent use as a speech mode. Attitudes toward code-switching have historically been linked to negative perceptions and, at times, strong negative stigma in certain contexts. Traditionally, switching languages has, therefore, been viewed as a sign of weakness, a lack of full language proficiency by the bilingual speaker, hindered by interference (Weinreich, 1953).

Code-switching cannot, however, simply be regarded as the bilingual’s insufficient control or ability in using one of the languages. One of the pioneering researchers to bring forth a reconsideration of code-switching as a sign of competence was Poplack (1980), who suggested code-switching to be a linguistic skill requiring a strong competence in more than one language, as opposed to a lack thereof. Poplack (1980) also noted that bilinguals who tend to code-switch without effort also tend to be fairly proficient; in fact, bilinguals who exhibited greater language proficiency preferred intrasentential switches, which are more difficult than intersentential code-switching because linguistic boundaries are not overtly apparent. A “reassessment” of code-switching was furthered by Woolard (1998), who described code-switching as “honoured in sociolinguistic analysis as a skilled and strategic performance that respects the discreteness of languages and their hard-edged boundaries, in contradistinction to the messy and aberrant chaos of interference and other interlingual phenomena” (p. 6). The presence of code-switching in the speech of a bilingual can, therefore, be a marker for the individual’s competence in both languages, and evidence for their understanding of the grammatical structures of their respective languages and their communicative effect (Gardner-Chloros, 2009).

Code-switching is not without social correlates. As bilinguals, individuals have garnered a wealth of unique and specific experiences that distinguish them from their monolingual peers. At the very least, bilinguals have had the opportunity to communicate and interact using another language, likely with a distinct ethnolinguistic group, and become exposed and possibly included in another culture. The significance of these experiences is that they have a direct impact on their thoughts, behaviors, and attitudes.

Attitudes correspond to the tendency to evaluate something as favorable or unfavorable (Allport, 1935; Banaji & Heiphetz, 2010); specifically with language attitudes, this evaluation is based on a linguistic feature, such as how individuals speak (Dragojevic, 2017; Garrett, 2010). Attitudes toward code-switching may, however, need to be considered separately from attitudes toward individual languages. Firstly, code-switching attitudes are distinct in that they are based on an appreciation of the languages when brought together and not on the simple combination of the individual appraisal of each of the languages. For example, in the Hong Kong context, both Cantonese and English have high linguistic value and social status, but only if the distinction between them is maintained; when Cantonese-English code-switching occurs, the code-switched speech garners an overall negative impression (Gibbons, 1987). Secondly, code-switching has been postulated to be a phenomenon that warrants its own distinct linguistic practice in theory (e.g. Auer, 1999; Muysken, 2000). As such, rather than comparing the evaluations between two (or more) language varieties, the focus is on a bilingual speech community’s evaluations toward a specific way of speaking that happens to include two different languages. Finally, code-switching acts differently – structurally and functionally – in different contexts (Heller, 1988; Poplack, 1987), and for that reason, attitudes toward code-switching are variable across time and space.

There have been relatively few studies on code-switching attitudes compared to the bulk of the literature on attitudes toward accents, dialects, and languages. Attitudes toward code-switching are recognized to be complex, with inter-individual and intra-individual variations among speakers; yet, there has been little attention on the topic in recent decades and it has seldom directly studied (Dewaele & Wei, 2014a). The early work on code-switching focused mostly on describing and establishing its stigmatized and negative associations, which we discussed briefly above. However, with globalization, immigration, and shifts in language ideologies, the recent literature on code-switching attitudes has focused on re-examining the phenomenon of code-switching in multilingual contexts. For example, Lawson and Sachdev (2000) studied Tunisian Arabic-French code-switching using experimental and field methods and found that although it remained associated with negative attitudes, it was also an unmarked ingroup practice in the community when two languages are conventionally used together without language switches being salient or noteworthy (Myers-Scotton, 1988). This suggests that despite its negative perception by the community, it can, as well, be a linguistic variety unique to that community.

Building on code-switching having a distinct role in a speech community, Gardner-Chloros et al. (2005) studied the Greek Cypriot community in London using questionnaires. They found that code-switching was a common ingroup practice and the use of Standard Modern Greek and the Greek-Cypriot dialect were both supported by the community. In particular, code-switching attitudes were not evaluated unfavorably; in fact, the younger generation valued code-switching as a part of their cultural identity. Code-switching may, therefore, show and possibly be employed as a marker of group membership by the younger members of the community who value it.

Code-switching not only contributes to the expression of social group and membership but also to assigning social categories, such as group membership and ethnicity (Cashman, 2005; Gafaranga, 2005; Poplack, 2018; Su, 2009). For example, language mixing legitimizes a hybrid identity, as reported by Atkinson and Kelly-Holmes (2011) in their analysis of Irish radio comedy. However, directly measuring code-switching attitudes and cultural identity is the exception rather than the norm in this discipline. Furthermore, research assessing code-switching attitudes has employed direct data collection methods, such as surveys and questionnaires (e.g. Dewaele & Wei, 2014b), with indirect methods measuring covert attitudes, such as the matched-guise technique, being rarely applied (e.g. Chana & Romaine, 1984; Guzzardo Tamargo et al., 2019; Yim & Clément, in-press).

In recent years, Dewaele and his colleagues aimed to study the variations between and within speakers in code-switching attitudes and to quantify the relationships among code-switching characteristics and various sociodemographic variables. In a comprehensive online questionnaire study of over 2000 multilinguals, Dewaele and Wei (2014b) found that more positive attitudes toward code-switching were linked to gender and educational level. In addition, they found that self-reported code-switching frequency was linked to many individual differences. For example, more frequent code-switchers tended to be female, extroverted, and also multilingual. Dewaele and Wei (2014a) further investigated the attitudes toward code-switching and individual differences, such as personality traits. They found that more positive attitudes toward code-switching to be significantly linked to lower levels of neuroticism and higher levels of tolerance of ambiguity and cognitive empathy, but code-switching attitudes were only weakly related to being multilingual and having a high level of extraversion. These findings suggest that although self-reported code-switching frequency and code-switching attitudes are closely related, they are indeed discrete concepts that, when examined in greater detail, each show distinct relationships with sociodemographic variables. Extending Dewaele’s research on personality traits, we postulate that openness to diversity and attitudes toward multiculturalism may be worthy of an investigation with code-switching. Miville et al. (1999) proposed the distinct psychological construct of Universal-Diverse Orientation, which corresponds to individuals with “an attitude of awareness and acceptance of both the similarities and differences among people” (p. 291). Given that more positive code-switching attitudes are reported by individuals who have been exposed to linguistically and culturally diverse environments (Dewale & Wei, 2014a), it is especially meaningful to explore bilinguals’ attitudes toward multiculturalism and diversity.

To summarize, code-switching is a communicative and social strategy used by bilinguals, consciously or subconsciously. They are using these linguistic cues as a means to index social categories and group solidarity. Thus, code-switching is linked to attitudes, seen as a reflection of the speaker and their values and identities (Myers-Scotton, 1993). As discussed above, if code-switched speech can be a linguistic variety unique to a community, it can also show group membership and be used as a marker of group membership. In addition, if code-switching can be symbolic of membership and solidarity, it can also represent individual group members’ identities.

Although there is copious research on the association between language and identity (Bucholtz & Hall, 2004; Edwards, 2009; Fishman, 1999; Ting-Toomey & Dorjee, 2014), there have been few studies focused on examining the link with code-switching (Yim & Clément, 2019). One such study, conducted by Dewaele and Nakano (2013), found that multilinguals reported feeling differently when switching between their languages, suggesting that shifts in identity were linked to language use. Moreover, a previous qualitative investigation found that the act of code-switching elicited both positive and negative reactions for bilinguals, producing conflicting feelings despite how they viewed their own bicultural identity (Yim & Clément, 2019). It is possible, then, that individual differences in identification would be linked to variations in code-switching attitudes and perceptions.

An Acculturation Framework for Cultural Identity

Social identity is “part of an individual’s self-concept which derives from their knowledge of their membership of a social group (or groups) together with the value and emotional significance attached to that membership” (Tajfel, 1981, p. 255). Moreover, Bucholtz and Hall (2004) underscore the importance of individuals’ own understanding and recognition of their identities: individuals organize themselves into groups because they “are driven not by some pre-existing and recognizable similarity but by agency and power” (p. 371). One of the strongest social categories in which individuals can define themselves is their cultural identity. Cultural identity can be considered an individual’s affiliation to and internalization of a particular culture, where one can access a set of shared norms that guide their behaviors (Giguère et al., 2010). The shared norms that influence the degree to which individuals identify with a particular culture arise from shared values, attitudes, and behaviors (cf. ethnic identity; Phinney, 1992), creating a sense of belonging and commitment to the ethnocultural group.

Cultural identity is dynamic, susceptible to change over time and space (Kuo & Roysircar, 2004; Toomey et al., 2013). Those who immigrate to a new setting and embrace a new way of life may, therefore, develop a sense of belonging and affiliation with the new dominant culture, particularly a new cultural identity through acculturation, but it is not necessarily at the expense of losing their heritage and ethnic culture (Berry, 1980; Berry et al., 1989). In such cases, then, cultural identity is the connection an individual may develop to both the mainstream and ethnic culture.

The idea that immigrants would favor maintaining their ethnic culture while developing an attachment to a new culture has been of relevance to cross-cultural psychology for many years because it has been central to understanding the well-being and adjustment of immigrants, refugees, newcomers, and the like. In fact, John Berry and his colleagues proposed in their bidimensional model of acculturation the concept of acculturation strategies to describe the variations in how individuals engage in the acculturation process, distinguishing between the orientations toward one’s own group versus the orientation toward the other group (Berry, 1980; Berry et al., 1989). Recognizing the existence of an interplay between the maintenance of one’s ethnic group culture and the need to create contact with the new culture, Berry et al. (1989) identified two continuums that individuals navigate through: the degree to which they wish to identify with their new culture (cultural contact) and the degree to which they wish to identify with their original culture (cultural maintenance). As a result, these two independent dimensions, a preference for maintaining the heritage culture and identity and a preference for engaging and participating in the dominant culture, creates four distinct acculturation strategies: integration (high sense of belonging to both the heritage and dominant cultures); assimilation (high for new culture and low for heritage culture); separation (low for new culture and high for heritage culture); and marginalization (low for both; Berry, 1980, 2007).

The bidimensional model has been tested in numerous studies examining psychological topics such as personality traits, social cognition, and mental health and well-being. Research suggests integration, seeking to participate in both cultures, as the most optimal strategy; individuals with an integration acculturation strategy were the most well-adapted group in many facets, showing more positive outcomes in personal well-being, greater psychosocial and socio-cultural adjustment, and the least acculturative stress, such as anxiety and uncertainty (Berry, 2006). Individuals adopting an integration strategy have been established to be associated with more positive psychological and socio-cultural adaptation (Berry, 2006); that is, people who prefer integration, had positive links to both cultural groups, and were able to speak both languages were simply better adapted.

Importantly, though, there is a presupposition here that individuals are freely able to choose how they wish to acculturate, but this is not always the case. The linguistic policies and cultural ideologies of the society-at-large may, however, impose restrictions on how individuals navigate between the two dimensions (Berry et al., 1977; Bourhis et al., 1997). As argued by Clément et al. (2001), an individual’s acculturation strategy may not necessarily correspond to their actual cultural identification. An individual’s own cultural identification can, however, be similarly conceptualized using a bidimensional framework (Phinney, 1990); that is, one’s identification with the heritage culture being independent from one’s identification with the dominant culture. Camilleri and Malewska-Peyre (1997) labeled these orientations as identity strategies and differentiate between an individual’s ideal identity versus their actual identity, which may be similar or vastly different. We acknowledge that it is possible for an individual’s ideal identity, or the identity strategy they wish to be, to be different from their “real” identity, but it is beyond the scope of this paper to discuss this important differentiation here. Following Clément and Noels (1992; see also Clément et al., 1993; Damji et al., 1996), our focus in the present paper is the actual cultural identity of the individual, according to how they see themselves, in the context of Berry’s bidimensional model.

As individuals with integrated strategies are linked to more positive outcomes, it can be surmised that a similar relationship may possibly exist between identity and code-switching. It is, therefore, expected that individuals with integrated identities, such as biculturals (those who have internalized two cultures through long-term and intense exposure, guiding their thoughts and feelings; Hong et al., 2000; LaFromboise et al., 1993; Phinney & Devich-Navarro, 1997), will be better adapted “linguistically,” that is, be able to freely speak both languages and hold more positive attitudes in using both languages, as in code-switching. Although the bidimensional model of acculturation has been widely accepted and tested by many empirical research studies, it remains uncertain whether those with different cultural identities, as classified by the model, would demonstrate differences in the area of code-switching, namely in attitudes and perceptions.

The Present Study

The present study, therefore, focuses primarily on the relationships between cultural identity and attitudes toward code-switching. Secondarily, we extend our questioning to attitudes toward multiculturalism. As discussed, it is possible that some communities perceive code-switching positively because it marks an association with integrated identities for its members. However, it has yet to be determined empirically whether attitudes toward code-switching are associated with individual variables, such as cultural identification, and individual differences within such variables, such as cultural identity strength, despite the established links between language and identity.

We adopt the framework of the bidimensional model previously used in the study of acculturation and identity strategies and apply it to our bilingual sample. Our research questions include examining the attitudes toward Cantonese-English code-switching in a multilingual Canadian context and investigating the relationships between such attitudes and cultural identification among groups classified along the bidimensional framework. That is, are existing code-switching attitudes associated with distinct cultural identities? We hypothesize that individuals with the most integrated identities (i.e. biculturals) will exhibit more positive attitudes toward code-switching as well as multiculturalism. Finally, we seek to examine the influence of cultural identity on various code-switching factors, such as its perceived frequency of use and its perceived contribution/disruption in conversation, and hypothesize that bicultural individuals will demonstrate a greater preference toward code-switching.

Cantonese-English Bilingualism in Canada

We ground the present research in Canada, where its multiculturalism ideologies promote equal status among cultural groups (Bourhis et al., 1997). Yet, English has status as an official language in Canada, while Cantonese does not. Three percent of the Canadian population indicated a Chinese language as their mother tongue (i.e. Cantonese, Mandarin, and other Chinese dialects, as defined by Statistics Canada, 2006). Cantonese is one of the top heritage languages spoken in many Chinese communities across Canada, and the Chinese community is the second-largest ethnic group in Canada. In Toronto alone, Cantonese is reported to be the heritage language most often spoken in its households (Statistics Canada, 2011) and is the top immigrant mother tongue, accounting for 9.5% of the 2.7 million people speaking an immigrant language (Statistics Canada, 2016). On a national level, Cantonese is the second most prevalent immigrant mother tongue with over 594,000 speakers, and consistently remains one of the most prevalent immigrant mother tongues across Canadian metropolitan cities (Toronto, Vancouver, Calgary, Edmonton, and Ottawa; Statistics Canada, 2011, 2016).

Although individuals within the Chinese community come from different regions, Cantonese is the main spoken language. Many first- and second-generation Cantonese speakers living in Canada originate from Hong Kong and the nearby southeastern region of China. For example, Hong Kong was the largest contributor to the immigrant population in Toronto from the period of 1991–1995; that is, at that time, 9.1% of new immigrants to Toronto were born in Hong Kong, the immigration rate peaking during those years as a consequence of political change (in contrast to the steady immigration rate of 4.3–4.5% during the years before and after; Statistics Canada, 2006). Of relevance here, Hong Kong has historically been a site of language contact. With its colonial history, English is prevalent from spoken discourse to written text. English is socially valued in Hong Kong, and approximately 43% of residents are communicatively competent in that language (2001 Hong Kong Census, as cited in Chen, 2005), resulting in circumstances promoting code-switching being a common social practice. Cantonese-English bilinguals who have emigrated from this environment and are living in Canada may, therefore, likely have similar linguistic practices.

Method

Participants

Sixty-seven Cantonese-English bilinguals (24 males, 43 females) participated in the study. Participants had a mean age of 23.41 years (SD = 7.81), ranging from 17 to 49 years old. Most of the sample was born in Canada versus being born elsewhere (n = 42 and n = 25, respectively). Those born elsewhere were born in Hong Kong (n = 17), China (n = 5), Denmark (n = 2), and Malaysia (n = 1). For the participants who were born overseas, 80% had lived in Canada for longer than 5 years and the mean length of residence was M = 13.38 (SD = 9.95). The participants in our sample were mostly one-and-a-half- and second-generation immigrants; they were from immigrant families, as their parents (mothers: n = 67, 100%; fathers: n = 65, 97%) were not born in Canada. A five-point Likert scale asking about parental education was used as a proxy for socioeconomic status, and the participants’ parents were typically high school graduates with a college diploma or some college experience (mothers: M = 2.70, SD = 13; fathers: M = 3.01, SD = 1.25), suggesting that they also had a modest socioeconomic status as middle-class families.

Participants were recruited in one of two ways. Firstly, the study was posted on the Integrated System for Research Participation at the University of Ottawa. Undergraduate students taking an introductory course were awarded one credit in exchange for participating in the study. Secondly, via snowball sampling, recruitment emails were sent to participants to share with their contacts and social networks. The inclusion criteria for the study were that participants must be able to speak and understand Cantonese.

Materials

Background and Language

Sociodemographic variables were assessed using a demographic and language questionnaire, which included questions on socioeconomic status and language learning history. Participants self-reported their language proficiency in speaking, comprehension, reading, and writing for Cantonese and English using a scale from 0 to 100, representing no proficiency to native-like proficiency. There was also a question regarding the participants’ bilingualism. They self-rated their bilingualism level on a five-point Likert scale, ranging from non-fluent bilingual to fluent bilingual.

Identity

Participants were presented with a question to self-identify themselves; they were given a list of responses to select from or allowed to input an ethnic self-label to describe themselves.

Cultural identity was also measured using the Vancouver Index of Acculturation (VIA; Ryder et al., 2000). The questionnaire included 20 questions relating to lifestyle, behaviors, and participation in cultural activities for each culture, allowing for a bidimensional measure of acculturation by generating separate subscores for the heritage culture and mainstream culture. For example, “I would be willing to marry a person from my native culture” and “I would be willing to marry a Canadian person.” The questions were presented randomly and responses were on a seven-point Likert scale. Reliability was measured using Cronbach’s alpha and was strong for both Canadian items, α = .81, and Chinese items, α = .87.

Code-switching

Attitudes toward code-switching were measured in two ways. The first was derived from a single question, “In my opinion, it is okay to switch between Cantonese and English,” which was indexed as personal code-switching attitudes, as it was self-referential and personal in nature. Secondly, five questions developed by Dewaele and Wei (2014a) were included to assess broader code-switching attitudes. The nature of the questions was theoretical and global in nature, often referring to individual values and beliefs. The responses were recorded on a five-point Likert scale and the reliability for the set of questions was moderate at α = .51. The score derived from this set of questions was labeled as general code-switching attitudes.

A 14-item questionnaire developed by Yim (2010) was also included to directly assess the code-switching practices of Cantonese-English bilinguals, as there is not yet a published systematic and comprehensive measure of code-switching available in the literature. The questionnaire surveyed topics such as code-switching frequency and functions attributed to code-switching, and drew on the participants’ own experiences, being specific and concrete in nature. Participants responded by indicating their responses using a sliding scale from 0 to 100, representing the percentage of time the statement applied to them. The numeric responses became the participants’ score for the corresponding question.

Multicultural Attitudes

The Miville-Guzman Universality-Diversity Scale – Short Form (Fuertes et al., 2000) was used to assess positive multicultural attitudes and openness to diversity. The 15-item questionnaire consisted of three dimensions: Diversity of Contact (five items); Relativistic Appreciation (five items); and Comfort with Differences (five items). Responses were measured on a six-point Likert-type scale from strongly disagree to strongly agree, with higher scores denoting greater openness to diversity (α = .77).

Procedure

The study was conducted in English using the Qualtrics online survey platform. Participants first provided informed consent before completing the set of questionnaires described above. Each participant was given the same questionnaire order, but within each questionnaire, the questions were randomly presented. To finish, participants were provided with a debriefing form.

Results

In the following section, we first present a description of the sample, followed by the mean results of each respective questionnaire, and finally the group comparisons on the dependent variables.

Descriptives

Participants were highly proficient in oral Cantonese and English (see Table 1) and they self-rated themselves as having a high level of bilingualism, M = 4.21 (SD = .82). Cantonese was the first language of most of the participants (n = 52). Other first languages include English (n = 10) and other Chinese dialects (n = 5). In a related question, 20 participants also indicated that they had learned Cantonese and English at the same time. Participants reported to be fluent in other languages as well, with French (n = 28) and Mandarin (n = 19) being the most common. It was important for the participants (or their families) to maintain their Cantonese language proficiency, as many were enrolled in Cantonese heritage language classes at a young age (n = 45) and continued these classes for many years (M = 7.54, SD = 4.33). Most participants indicated English as their dominant language (n = 51). English was the language they used most often and most regularly (n = 42), but some participants also indicated they used both Cantonese and English most often and regularly (n = 17).

Table 1.

Mean scores (and standard deviations) for Cantonese and English proficiency on a scale of 0–100 (no proficiency to native-like proficiency).

| Cantonese | English | |

|---|---|---|

| Speaking | 79.13 (22.84) | 93.66 (10.30) |

| Comprehension | 85.73 (16.81) | 95.98 (7.70) |

| Reading | 55.31 (37.42) | 94.80 (8.94) |

| Writing | 48.60 (35.31) | 91.80 (12.70) |

Most participants considered themselves part of or belonging to the Chinese community (n = 48; 71.6%). Identity was assessed using the VIA scale and participants exhibited high acculturation to both Canadian culture, M = 5.77 (SD = .68), and Chinese culture, M = 5.59 (SD = .81). When given the opportunity to self-select or input an ethnic self-label to describe themselves, the most frequently used terms were Canadian-born Chinese (n = 20), Chinese Canadian (n = 15), and Hong Kong Chinese (n = 9). In the participants’ self-identification, participants preferred two-term labels, which incorporated their dual Canadian and Chinese identities (68.7%), compared to a Chinese-only label (26.9%) and a Canadian-only label (1.5%). In contrast to their report of their parents’ ethnicities, the labels most frequently used by the participants for their mothers and fathers were Hong Kong Chinese (n = 28 and n = 24, respectively) and Chinese (n = 24 and n = 25, respectively).

Means Analyses

Code-switching Attitudes and Factors

The participants’ personal code-switching attitudes score was high (M = 81.42, SD = 26.69), as well as their general code-switching attitudes score (M = 3.59, SD = .56). The two scores were significantly correlated with each other (see Table 2).

Table 2.

Mean scores and Spearman’s rho correlation matrix for code-switching factors and attitudes.

| Mean (SD) | Code-switching factors | Code-switching attitudes | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Behaviors | Comfort | Preference | Personal | General | ||

| Behaviors | 54.76 (29.26) | – | .478*** | .530*** | .215 † | .316** |

| Comfort | 72.62 (23.47) | – | .388** | .580*** | .444*** | |

| Preference | 59.96 (25.89) | – | .269* | .229 † | ||

| Personal | 81.42 (26.69) | – | .396** | |||

| General | 3.59 (.56) | – | ||||

p < .05; **p < .01; ***p < .001; †p < .10.

A principal components analysis with Oblimin rotation was conducted on the 14-item code-switching questionnaire surveying various perceptions of the participants’ code-switching (see Table 3). Three components were identified, which accounted for 65.82% of the total variance: behaviors (four items; α = .86); comfort (six items; α = .83); and preference (three items; α = .78). One item did not directly map onto any of the factors without reducing internal reliability and was removed from analyses since it was a reverse-phrased item of another item (“I prefer to use one language when communicating with other bilinguals”). The above three code-switching components, therefore, served as the code-switching factors used in subsequent analyses.

Table 3.

Rotated factor matrix from principal components analysis with Oblimin rotation of 14 code-switching questions.

| Component | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Behaviors | Comfort | Preference | |

| Generally, I switch between Cantonese and English | .690 | ||

| I switch between Cantonese and English when I’m speaking | .861 | ||

| I switch between Cantonese and English in the same sentence | .883 | ||

| I switch between Cantonese and English between sentences (e.g. one sentence in one language, then the next one is in the other language) | .890 | ||

| I use Cantonese and English everyday | .664 | ||

| I switch between Cantonese and English easily | .879 | ||

| It takes effort for me to switch between Cantonese and English a | .910 | ||

| I am comfortable switching between Cantonese and English in public (e.g. in front of strangers) | .447 | ||

| I am comfortable switching between Cantonese and English in private (e.g. in front of people I know well) | .482 | ||

| Overall, I am comfortable switching between Cantonese and English | .528 | ||

| I like to switch between Cantonese and English | .833 | ||

| I like it when other people speak to me using both Cantonese and English | .952 | ||

| I prefer to switch between Cantonese and English | .677 | ||

| I prefer to use one language when communicating with other bilingualsa,b | |||

| Total variance (%) | 42.77 | 13.23 | 9.82 |

| Reliability (α) | .86 | .83 | .78 |

Reverse-scored item.

Removed item.

Participants were moderate in their code-switching behaviors (M = 54.76, SD = 29.26), suggesting that, on average, they code-switched only half of the time in their daily lives. Behaviors was significantly correlated with the other two factors, comfort and preferences (see Table 2). The code-switching behaviors index was also significantly correlated with the participants’ general code-switching attitudes score, but only as a trend with their personal code-switching attitudes score.

Participants found code-switching to be an effortless task and felt at ease code-switching in private as well as in public settings, as their code-switching comfort score was high (M = 72.62, SD = 23.47). It was also significantly correlated with their code-switching preferences, personal code-switching attitudes score, and general code-switching attitudes score.

Participants moderately liked or preferred using code-switching in their discourse, especially when others use code-switching (M = 59.95, SD = 25.89). Preference was also significantly correlated with personal code-switching attitudes, but was only a trend with general code-switching attitudes.

Multicultural Attitudes

Participants exhibited favorable attitudes toward multiculturalism and were open to diversity, with a mean score of 4.57 (SD = .53). However, the score was not correlated with any of the code-switching attitudes scores or factors.

Group Comparisons

Participants were asked to self-label their cultural identity, as we consider self-labeling to be an important reflection of cultural identity using the participants’ own words. In a point-biserial correlation, the participants’ self-labeling was significantly correlated to their Canadian VIA scores only, r = .34, p < .01, confirming that their cultural identity scores (as measured by the VIA, focusing on concrete behaviors and experiences) closely paralleled their self-labels and were a reliable proxy for cultural identification. There was no significant correlation between Canadian and Chinese identity, rho = −.17, ns.

We classified participants into subgroups derived from the bidimensional model of acculturation using participants’ VIA scores and splitting each cultural dimension (i.e. their respective Canadian and Chinese VIA scores) by performing a median split. As a result, four identity subgroups (integration, assimilation, separation, and marginalization) were created. Although the method elicited groups of comparable sizes, the mean VIA scores did not necessarily reflect the identity orientations. For example, the marginalization group who was supposed to be low in Canadian and Chinese identification actually had mean VIA scores of 5.28 (SD = .52) and 5.35 (SD = .32) out of a possible maximum score of 7, respectively. The high scores were a little unexpected, as that group would be presumed to exhibit low scores on both identification scales. However, it is possible for responses on scales (e.g. racial identity; Fischer et al., 1998) to be negatively skewed due to self-presentation biases and socially desirable responding (Paulhus, 1991).

For these reasons, we then split the sample according to the scale midpoint (i.e. using 4 as the cut point in the seven-point Likert scale) in order to elicit a more accurate categorization of the subgroups. Using the midpoint split method, three different groups were created, integration/biculturals (n = 62), assimilation (n = 3), and separation (n = 2), according to their Canadian and Chinese VIA scores. No participants were classified in the marginalization category. Although the midpoint split elicited more accurate divisions for the subgroups, it did not produce subgroups of comparable sizes. Since the majority of the participants were classified as biculturals, we decided to only use the bicultural group in analyses and omit the five participants classified as non-biculturals.

To further take a closer look at our biculturals, a median split was applied to the bicultural group’s Canadian and Chinese VIA scores, resulting in four bicultural subgroups: integration (n = 14), assimilation (n = 17), separation (n = 16), and marginalization (n = 14). The terminology from the bidimensional classification was confusing, as these participants were all biculturals, and only differed in the strength of identification to the Canadian and Chinese cultures (see Table 4). We therefore labeled the four bicultural subgroupings as follows: (a) strong biculturals, participants who are the biculturals with the strongest identification to both cultures, n = 15; (b) Canadian-oriented biculturals, participants who are biculturals but show stronger identification toward Canadian culture, n = 17; (c) Chinese-oriented biculturals, participants who are biculturals but show stronger identification toward Chinese culture, n = 16; and (d) weak biculturals, participants who are biculturals but have do not have a strong affiliation to either culture, n = 14.

Table 4.

Mean scores (and standard deviations) of Canadian and Chinese identification by group.

| Participants | n | Canadian identity | Chinese identity |

|---|---|---|---|

| Biculturals | 62 | 5.81 (.56) | 5.71 (.55) |

| Strong biculturals | 15 | 6.21 (.29) | 6.18 (.27) |

| Canadian-oriented biculturals | 17 | 6.30 (.36) | 5.25 (.40) |

| Chinese-oriented biculturals | 16 | 5.37 (.28) | 6.13 (.31) |

| Weak biculturals | 14 | 5.31 (.39) | 5.29 (.31) |

| Assimilation | 3 | 6.29 (.53) | 2.83 (.21) |

| Separation | 2 | 3.65 (.35) | 6.00 (.71) |

Code-switching Attitudes

A 2 × 2 analysis of variance (ANOVA) was computed on both the personal and general attitudes indices using Canadian and Chinese identity as factors along the distinctions described above. There was no main effect of Canadian identification on either code-switching attitudes measure, but there was a main effect of Chinese identification on personal, F(1,56) = 7.26, p < .01, and general code-switching attitudes, F(1,58) = 6.43, p < .05. Biculturals who identified strongly with Chinese culture showed more positive personal code-switching attitudes (M = 90.07, SD = 16.85) and general code-switching attitudes (M = 3.73, SD = .49) compared to their counterparts who did not identify strongly with Chinese culture (M = 71.17, SD = 32.25 and M = 3.39, SD = .55, respectively). Bicultural participants who showed a high Chinese identification exhibit more positive attitudes toward code-switching, irrespective of the strength of their Canadian identification. There were no significant interactions between Canadian and Chinese identity on personal code-switching attitudes or general code-switching attitudes, Fs < 1, ns.

Code-switching Factors

A series of 2 × 2 ANOVAs following the same design were conducted to test whether there were significant differences in each of the code-switching factors: behaviors, comfort, and preferences.

For behaviors, no significant differences were obtained, Fs < 1, ns.

For code-switching comfort, there was a main effect of Chinese identity, F(1,58) = 7.87, p < .01, with those high in Chinese identification (M = 80.62, SD = 18.91) being more comfortable with code-switching than those low in Chinese identification (M = 64.64, SD = 24.43). There was also a main effect of Canadian identity, F(1,58) = 4.29, p < .05, but it was in the opposite direction, as those high in Canadian identification (M = 66.83, SD = 27.29) were less comfortable compared to those low in Chinese identification (M = 78.83, SD = 15.84). There was no significant interaction, F(1,58) = 3.00, p = .08.

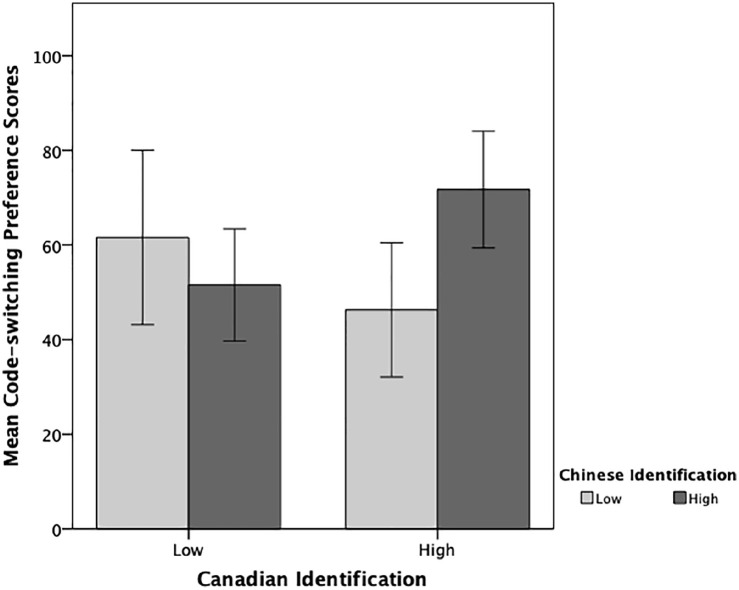

Lastly, for code-switching preference, there were no main effects of Canadian, F(1,52) = .14, ns, or Chinese identity, F(1,52) = 1.41, ns. However, there was a significant interaction between Canadian and Chinese identity, F(1,52) = 7.48, p < .01, with strong biculturals most preferring code-switching in communication (M = 71.72, SD = 22.25; see Figure 1). Tests of simple main effects showed that there were significant effects for Chinese and Canadian identities. Biculturals with a strong Chinese identity exhibited a significantly greater preference for code-switching than those with a weak Chinese identity at high Canadian identification (strong biculturals versus Canadian-oriented biculturals; p = .007), but no differences at low Canadian identification (Canadian-oriented biculturals versus weak biculturals; p = .281). The simple main effects analysis also showed that strong biculturals significantly preferred code-switching compared to Chinese-oriented biculturals (p = .024), but there were no differences between Canadian-oriented biculturals and weak biculturals (p = .119).

Figure 1.

Mean code-switching preference scores by Canadian and Chinese identification.

Multicultural Attitudes

In a 2 × 2 ANOVA to test the influence of Canadian identity and Chinese identity on multicultural attitudes among the biculturals, no significant interaction nor main effect of Chinese identity was found, Fs < 1, ns. There was a significant main effect for Canadian identity, F(1,56) = 4.47, p < .05, suggesting that irrespective of Chinese identity, biculturals who identify strongly with Canadians were more open to diversity and held more positive multicultural attitudes than those who identified less strongly.

Discussion

The present study investigated the linguistic outlook of Cantonese-English bilinguals, particularly their attitudes toward code-switching in relation to their cultural identification. Overall, there were positive attitudes toward Cantonese-English code-switching; in the Canadian context, it was far from being a stigmatized speech practice. Participants held neutral to favorable attitudes toward code-switching and variations in their attitudes were associated with their degree of cultural identification. Specifically, Chinese cultural identity showed a significant relationship with both personal and general code-switching attitudes: participants who identified more strongly as Chinese also showed more positive attitudes toward Cantonese-English code-switching.

It was hypothesized that individuals with integrated identities would exhibit more positive code-switching attitudes and more positive multicultural attitudes. This was confirmed, but more nuanced distinctions among individuals with integrated identities were found. The strong biculturals group, who identified most strongly with Canadian and Chinese cultures, indeed held strong positive attitudes toward code-switching, but additionally, the Chinese-oriented biculturals also demonstrated positive code-switching attitudes. Although unexpected, the fact that the Chinese-oriented bicultural participants demonstrated equally positive attitudes revealed that a significant correlate of holding favorable code-switching attitudes was Chinese identity strength. It appears that maintaining a strong Chinese cultural identity is linked with being more linguistically accepting, open to the different language practices of other members in the speech community. A bicultural who strongly identifies with their ethnic identity not only views their own code-switching as positive, but is also more accepting of code-switching in general. On the other hand, strong biculturals also held the most favorable multicultural attitudes and were most open to diversity, along with Canadian-oriented biculturals. This is not completely unexpected, as Canada’s ideologies encourage multicultural diversity and acceptance; however, our findings here indicate that, in the Canadian context, the strength of Canadian identification and strength of Chinese identification may be conducive to boosting different attitudes, that is, code-switching and multicultural. It is strikingly clear that the results demonstrate strong biculturals as the most open and accepting, holding the most favorable code-switching and multicultural attitudes. Moreover, these results with both the code-switching and multicultural attitudes suggest the same alignment for the effects of individual differences in identity, indicating that they are associated with more favorable linguistic and socio-cultural attitudes.

Situating our findings within the code-switching literature, it may be that previous studies of bilingual communities that have been shown to be favorable to code-switching and view it as a positive act, may actually reflect contexts that are both linguistically and culturally supportive. For example, Yim and Clément (2019) document the city of Toronto, Canada, as a receptive site of bilingualism and code-switching. Such communities likely allow their members to use and maintain their heritage languages in addition to being protective of their ethnic identity. Taking a holistic view, when biculturals are allowed and encouraged to preserve and reinforce their ethnic identity, the consequences are socio-cultural as well as linguistic. Certainly, the degree of cultural identification toward the broader, dominant culture remains important, as it is often the focus for immigrants as they adopt a different way of life and embrace the new mainstream culture. However, ethnic identity strength may operate to foster more favorable and constructive attitudes that, consequently, may enable more diverse cross-linguistic practices, such as code-switching. In order for environments to encourage bilingualism and linguistic diversity and acceptance, it is, therefore, essential for them to also promote ethnic identity maintenance and development.

In addition to code-switching attitudes, the present findings expanded to encompass three code-switching factors: behaviors, comfort, and preference. Code-switching behaviors was the only factor that did not exhibit any significant group differences. As the results showed, the participants had reported to code-switch about half of the time in their daily lives, and they were highly comfortable code-switchers who often preferred it in communications. However, despite these findings, the frequency of the bicultural groups’ code-switching use simply did not reflect this. A reason may be that there are not enough occasions in their daily lives for them to use code-switching, even in multilingual and multicultural contexts where code-switching would be commonplace. Thus, it is possible that due to the limited opportunities for using code-switching (especially Cantonese-English code-switching), we were unable to find any differences in code-switching behaviors among the bicultural subgroups. It is also probable that it is difficult for the effects of code-switching behaviors to become apparent because these are concrete actions that bilinguals must take, unlike attitudes and preferences.

Turning to the comfort and preference factors, results revealed that, overall, participants were very comfortable using code-switching: they reported that they used Cantonese and English every day most of the time, they were comfortable code-switching in private almost always, and were also comfortable code-switching in public. They simply did not find code-switching to be a difficult task. Code-switching was easy for them, and likely because of the ease of switching, they also liked to code-switch and preferred to code-switch about half of the time. They also reported to sometimes prefer code-switched speech, suggesting that code-switching added value to their communications. Importantly, there were significant differences in code-switching comfort among the biculturals. Participants who strongly identified with Chinese culture were more comfortable code-switchers who found code-switching to be easy, compared to those who identified less with the Chinese culture. The significant main effect of Canadian identity, however, demonstrated that the opposite was true for biculturals and their degree of Canadian identification. Bicultural participants with a strong Canadian identity were actually significantly less comfortable code-switching and viewed it as a more effortful task.

It was not entirely surprising that a stronger identification toward Canadian versus Chinese culture elicited different code-switching comfort results. It has been well-established that the two cultural dimensions that immigrants, or biculturals, negotiate in their identification are independent. This effect of Canadian identity was, however, interesting, as it suggested that there may be indirect disadvantages to developing and/or maintaining a high degree of identification toward the dominant, mainstream culture. Depending on the ideologies and policies of the society-at-large, perhaps additional bolsters may be needed to support immigrants’ ethnic culture(s), either implemented by formal institutions or informal community practices, in order for biculturals to become comfortable code-switchers who can use their heritage language with ease.

We also confirmed our hypothesis that strong biculturals would show a greater preference for code-switching, compared to all other bicultural subgroups. The significant interaction between Canadian and Chinese identity on code-switching preferences revealed that biculturals high in Chinese identification preferred code-switching more than biculturals low in Chinese identification, but only if they also had a strong Canadian identity. That is, strong biculturals most preferred code-switching in communication, followed by the weak biculturals, and the Chinese-oriented and Canadian-oriented biculturals preferred code-switching the least (approximately only 50% of the time). Unlike code-switching comfort, Chinese-oriented biculturals did not prefer code-switching in communication (despite them being comfortable doing so).

It is possible that Chinese-oriented (and Canadian-oriented) biculturals not preferring code-switching could be linked to them being uneven biculturals. We were able to identify these subgroups within a seemingly homogeneous bicultural group, suggesting that individual differences in cultural identity can reveal further differentiations among biculturals. Adopting the bidimensional framework, our classification does not focus on the extent to which the two cultures are integrated within the individual (cf. bicultural identity integration; Benet-Martínez & Haritatos, 2005); rather, we emphasize the manner in which the two cultures are negotiated and how even though an individual may be a bicultural, their strength of identification toward each culture is independent and can vary, which has yet to be carried out in previous studies. It is noteworthy as there has been little research examining the individual differences across bicultural individuals, aside from the work by Benet-Martínez and colleagues. Rather than focusing on the integration or compatibility of the biculturals’ relative cultural identities, however, we believe it is crucial to highlight the respective strength of the co-existing, yet independent, cultural identities as a means to differentiate and classify a group of biculturals. Moreover, we highlight the significance of the defined subgroups, within a seemingly homogeneous bicultural sample, consequently exhibiting differences in language attitudes.

One of the primary goals of the present study was to highlight the relationship between cultural identity and code-switching attitudes, specifically underlining the specific linguistic concept of code-switching and its association with social psychological variables. In addition, although all participants in our analyses were classified as biculturals, we understand that the label can encompass much variation in outlook (Cheng et al., 2014). Nonetheless, the results revealed our bicultural individuals to indeed be highly homogeneous – one-and-a-half- and second-generation immigrants who grew up modestly in a middle-class environment in Canada with parents whom they perceived to identify as primarily (Hong Kong) Chinese. We can argue that the sheer homogeneity of our sample makes our conclusions exceptionally striking; it was meaningful and plausible to assess cultural identity strength using a bidimensional framework as independent variables to produce distinct subgroups. As shown, this resulted in significant intergroup differences in code-switching attitudes and preferences.

Conclusion

By applying a bidimensional framework to these issues, we were able to expose novel and subtle differences between members of a group, which would otherwise be perceived as homogenously bilingual. Our findings show that among biculturals, differences in code-switching and multicultural attitudes, along with code-switching preferences, are a function of the strength of cultural identification. Furthermore, cultural identity strength showed a clear relationship with code-switching: strong biculturals exhibited more positive code-switching and greater code-switching preferences, as well as more positive multicultural attitudes and greater openness. The findings open the path to further examinations of the social correlates of biculturality for intergroup communication and ancillary phenomena, such as social harmony and cohesion in multicultural contexts.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank Victoria White, Grace Easton, and Naomie Joseph for their assistance with the study as well as all of our bilingual participants. We also appreciate the reviewers for their feedback on the manuscript.

Author biographies

Odilia Yim completed her PhD at the University of Ottawa and is currently a Post-doctoral Researcher at the University of Toronto. Her dissertation on attitudes towards code-switching has demonstrated that speech practices can invalidate individuals’ ethnic identities and influence social judgments, emphasizing the impact of language variation on intergroup relations and communication. Her research focuses on the consequences of bilingualism, specifically the effects on social evaluations and group solidarity among diverse populations such as immigrants and ethnic minorities.

Richard Clément is emeritus professor of Psychology at the University of Ottawa. His current research interests include issues related to bilingualism, second language acquisition and identity change and adjustment in the acculturative process, topics on which he has published extensively in both French and English, in America, Asia and Europe. He is an elected Fellow of both the Canadian and the American Psychological Associations and the Royal Society of Canada. As well, he has recently been made a Knight of the Order of the Academic Palms by the Republic of France.

Footnotes

Declaration of conflicting interests: The authors declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Funding: The authors disclosed receipt of the following financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: This work was supported by a Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council Doctoral Scholarship awarded to Odilia Yim and grant no. 435-2015-0359 from the Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council to Richard Clément.

ORCID iD: Odilia Yim  https://orcid.org/0000-0003-4053-9599

https://orcid.org/0000-0003-4053-9599

References

- Allport G. W. (1935). Attitudes. In Murchison C. A. (Ed.), A handbook of social psychology (pp. 798–844). Clark University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Appel R., Muysken P. (1987). Language contact and bilingualism. Edward Arnold (Publishers) Ltd. [Google Scholar]

- Atkinson D., Kelly-Holmes H. (2011). Codeswitching, identity and ownership in Irish radio comedy. Journal of Pragmatics, 43(1), 251–260. [Google Scholar]

- Auer P. (1999). From codeswitching via language mixing to fused lects: Toward a dynamic typology of bilingual speech. International Journal of Bilingualism, 3(4), 309–332. [Google Scholar]

- Banaji M. R., Heiphetz L. (2010). Attitudes. In Fiske S., Gilbert D., Lindzey G. (Eds.), Handbook of social psychology (5th ed., Vol. 1, pp. 348–388). John Wiley & Sons. [Google Scholar]

- Benet-Martínez V., Haritatos J. (2005). Bicultural identity integration (BII): Components and psychosocial antecedents. Journal of Personality, 73(4), 1015–1049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berry J. W. (1980). Acculturation as varieties of adaptation. In Padilla A. (Ed.), Acculturation: Theory, models and findings (pp. 9–25). Westview. [Google Scholar]

- Berry J. W. (2006). Stress perspectives on acculturation. In Sam D., Berry J. W. (Eds.), Cambridge handbook of acculturation psychology (pp. 43–57). Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Berry J. W. (2007). Acculturation and identity. In Bhugra D., Bhui K. S. (Eds.), Textbook of cultural psychiatry (pp. 169–178). Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Berry J. W., Kalin R., Taylor D. (1977). Multiculturalism and ethnic attitudes in Canada. Supply and Services. [Google Scholar]

- Berry J. W., Kim U., Power S., Young M., Bujaki M. (1989). Acculturation attitudes in plural societies. Applied Psychology: An International Review, 38(2), 185–206. [Google Scholar]

- Bourhis R., Moise C., Perreault S., Senécal S. (1997). Towards an interactive acculturation model: A social psychological approach. International Journal of Psychology, 32(6), 369–386. [Google Scholar]

- Bucholtz M., Hall K. (2004). Language and identity. In Duranti A. (Ed.), A companion to linguistic anthropology (pp. 369–394). Blackwell. [Google Scholar]

- Camilleri C., Malewska-Peyre H. (1997). Socialisation and identity strategies. In Berry J. W., Dasen P. R., Saraswathi T. S. (Eds.), Handbook of cross-cultural psychology, vol. 2, basic processes and human development (pp. 41–68). Allyn and Bacon. [Google Scholar]

- Cashman H. R. (2005). Identities at play: Language preference and group membership in bilingual talk in interaction. Journal of Pragmatics, 37(3), 301–315. [Google Scholar]

- Chana U., Romaine S. (1984). Evaluative reactions to Panjabi/English code-switching. Journal of Multilingual and Multicultural Development, 5(6), 447–473. [Google Scholar]

- Chen K. H. Y. (2005). The social distinctiveness of two code-switching styles in Hong Kong. In Cohen J., McAlister K., Rolstad K., MacSwan J. (Eds.), Proceedings of the 4th international symposium on bilingualism (pp. 527–541). Cascadilla Press. [Google Scholar]

- Cheng C.-Y., Lee F., Benet-Martínez V., Huynh Q.-L. (2014). Variations in multicultural experience: Influence of bicultural identity integration on socio-cognitive processes and outcomes. In Benet-Martínez V., Hong Y.-Y. (Eds.), Oxford handbook of multicultural identity (pp. 276–299). Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Clément R., Gauthier R., Noels K. (1993). Choix langagiers en milieu minoritaire: Attitudes et identité concomitantes. Revue canadienne des sciences du comportement, 25(2), 149–164. [Google Scholar]

- Clément R., Noels K. A. (1992). Towards a situated approach to ethnolinguistic identity: The effects of status on individuals and groups. Journal of Language and Social Psychology, 11(4), 203–232. [Google Scholar]

- Clément R., Noels K. A., Deneault B. (2001). Interethnic contact, identity and psychological adjustment: The mediating and moderating roles of communication. Journal of Social Issues, 57(3), 557–577. [Google Scholar]

- Damji T., Clément R., Noels K. A. (1996). Acculturation mode, identity variation, and psychosocial adjustment. The Journal of Social Psychology, 136(4), 493–500. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Bot K. (1992). A bilingual production model: Levelt’s ‘speaking’ model adapted. Applied Linguistics, 13(1), 1–24. [Google Scholar]

- Dewaele J., Nakano S. (2013). Multilinguals’ perceptions of feeling different when switching languages. Journal of Multilingual and Multicultural Development, 34(2), 107–120. [Google Scholar]

- Dewaele J.-M., Wei L. (2014. a). Attitudes towards code-switching among adult mono- and multilingual language users. Journal of Multilingual and Multicultural Development, 35(3), 235–251. [Google Scholar]

- Dewaele J.-M., Wei L. (2014. b). Intra-and inter-individual variation in self-reported code-switching patterns of adult multilinguals. International Journal of Multilingualism, 11(2), 225–246. [Google Scholar]

- Dragojevic M. (2017). Language attitudes. In Giles H., Harwood J. (Eds.), The Oxford encyclopedia of intergroup communication (Vol. 1, pp. 263–278). Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Edwards J. (2009). Language and identity. Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Fischer A. R., Tokar D. M., Serna G. S. (1998). Validity and construct contamination of the Racial Identity Attitude Scale-Long Form. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 45(2), 212–224. [Google Scholar]

- Fishman J. A. (1999). Handbook of language and ethnic identity. Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Fuertes J. N., Miville M. L., Mohr J. J., Sedlacek W. E., Gretchen D. (2000). Factor structure and short form of the Miville-Guzman Universality-Diversity Scale. Measurement and Evaluation in Counseling and Development, 33(3), 157–169. [Google Scholar]

- Gafaranga J. (2005). Demythologising language alternation studies: Conversational structure vs. social structure in bilingual interaction. Journal of Pragmatics, 37(3), 281–300. [Google Scholar]

- Gardner-Chloros P. (2009). Sociolinguistic factors in code-switching. In Bullock B., Toribio A. J. (Eds.), Cambridge handbook of linguistic code-switching (pp. 97–113). Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Gardner-Chloros P., McEntee-Atalianis L., Finnis K. (2005). Language attitudes and use in a transplanted setting: Greek Cypriots in London. International Journal of Multilingualism, 2(1), 52–80. [Google Scholar]

- Garrett P. (2010). Attitudes to language. Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Gibbons J. (1987). Code-mixing and code choice: A Hong Kong case study. Multilingual Matters. [Google Scholar]

- Giguère B., Lalonde R., Lou E. (2010). Living at the crossroads of cultural worlds: The experience of normative conflicts by second generation immigrant youth. Social and Personality Psychology Compass, 4(1), 14–29. [Google Scholar]

- Grosjean F. (1982). Life with two languages: An introduction to bilingualism. Harvard University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Grosjean F. (1998). Studying bilinguals: Methodological and conceptual issues. Bilingualism: Language and Cognition, 1(2), 131–149. [Google Scholar]

- Guzzardo Tamargo R. E., Loureiro-Rodríguez V., Fidan Acar E., Vélez Avilés J. (2019). Attitudes in progress: Puerto Rican youth’s opinions on monolingual and code-switched language varieties. Journal of Multilingual and Multicultural Development, 40(4), 304–321. [Google Scholar]

- Heller M. (Ed.). (1988). Codeswitching: Anthropological and sociolinguistic perspectives. Mouton de Gruyter. [Google Scholar]

- Hong Y. Y., Morris M. W., Chiu C. Y., Benet-Martínez V. (2000). Multicultural minds: A dynamic constructivist approach to culture and cognition. American Psychologist, 55(7), 709–720. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuo B. C. H., Roysircar G. (2004). Predictors of acculturation for Chinese adolescents in Canada: Age of arrival, length of stay, social class, and English reading ability. Journal of Multicultural Counseling and Development, 32(3), 143–154. [Google Scholar]

- LaFromboise T., Coleman H., Gerton J. (1993). Psychological impact of biculturalism: Evidence and theory. Psychological Bulletin, 114(3), 395–412. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lawson S., Sachdev I. (2000). Codeswitching in Tunisia: Attitudinal and behavioural dimensions. Journal of Pragmatics, 32(9), 1343–1361. [Google Scholar]

- Low W. W. M., Lu D. (2006). Persistent use of mixed code: An exploration of its functions in Hong Kong schools. International Journal of Bilingual Education and Bilingualism, 9(2), 181–204. [Google Scholar]

- Miville M. L., Gelso C. J., Pannu R., Liu W., Touradji P., Fuertes J. N. (1999). Appreciating similarities and valuing differences: The Miville–Guzman Universality–Diversity scale. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 46(3), 291–307. [Google Scholar]

- Muysken P. (2000). Bilingual speech: A typology of code-mixing. Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Myers-Scotton C. (1988). Codeswitching as indexical of social negotiations. In Wei L. (Ed.), The bilingualism reader (pp. 127–153). Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Myers-Scotton C. (1993). Social motivations for code-switching. Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Paulhus D. L. (1991). Measurement and control of response bias. In Robinson J. P., Shaver P. R., Wrightsman L. S. (Eds.), Measures of social psychological attitudes, volume 1: Measures of personality and social psychological attitudes (pp. 17–59). Academic Press. [Google Scholar]

- Phinney J. S. (1990). Ethnic identity in adolescents and adults: Review of research. Psychological Bulletin, 108(3), 499–514. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Phinney J. S. (1992). The multigroup ethnic identity measure: A new scale for use with diverse groups. Journal of Adolescent Research, 7(2), 156–176. [Google Scholar]

- Phinney J. S., Devich-Navarro M. (1997). Variations in bicultural identification among African American and Mexican American adolescents. Journal of Research on Adolescence, 7(1), 3–32. [Google Scholar]

- Poplack S. (1980). Sometimes I’ll start a sentence in Spanish y termino en Español: Toward a typology of code-switching. Linguistics, 18, 581–618. [Google Scholar]

- Poplack S. (1987). Contrasting patterns of code-switching in two communities. In Wande E., Anward J., Nordberg B., Steensland L., Thelander M. (Eds.), Aspects of multilingualism (pp. 51–77). Borgströms. [Google Scholar]

- Poplack S. (2018). Borrowing: Loanwords in the speech community and in the grammar. Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Ryder A., Alden L., Paulhus D. (2000). Is acculturation unidimensional or bidimensional? Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 79(1), 49–65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Statistics Canada. (2006). Ethnocultural portrait of Canada highlight tables, 2006 census. “Ethnic origin and visible minorities, 2006 census.” Census, Statistics Canada Catalogue No. 97-562-XWE2006002, Ottawa, Ontario, April 2, 2008. Retrieved October 16, 2014, from http://www12.statcan.ca/census-recensement/2006/rt-td/index-eng.cfm

- Statistics Canada. (2011). Linguistic characteristics of Canadians, 2011 census. Census, Statistics Canada Catalogue No. 98-314-X-2011001, Ottawa, Ontario, October 2012. http://www12.statcan.ca/census-recensement/2011/as-sa/98-314-x/98-314-x2011001-eng.cfm

- Statistics Canada. (2016). Linguistic diversity and multilingualism in Canadian homes, 2016 census. Census in Brief, Statistics Canada Catalogue No. 98-200-X2016010, Ottawa, Ontario, Canada. https://www12.statcan.gc.ca/census-recensement/2016/as-sa/98-200-x/2016010/98-200-x2016010-eng.cfm

- Su H.-Y. (2009). Code-switching in managing a face-threatening communicative task: Footing and ambiguity in conversational interaction in Taiwan. Journal of Pragmatics, 41(2), 372–393. [Google Scholar]

- Tajfel H. (1981). Human group and social categories: Studies in social psychology. Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Ting-Toomey S., Dorjee T. (2014). Language, identity, and culture: Multiple identity-based perspectives. In Holtgraves T. M. (Ed.), The Oxford handbook of language and social psychology (pp. 27–45). Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Toomey A., Dorjee T., Ting-Toomey S. (2013). Bicultural identity negotiation, conflicts, and intergroup communication strategies. Journal of Intercultural Communication Research, 42(2), 112–134. [Google Scholar]

- Weinreich U. (1953). Languages in contact: Findings and problems. Mouton de Gruyter. [Google Scholar]

- Woolard K. A. (1998). Simultaneity and bivalency as strategies in bilingualism. Journal of Linguistic Anthropology, 8(1), 3–29. [Google Scholar]

- Yim O. (2010). The relationship between code-switching and task switching in Cantonese-English bilinguals [Unpublished master’s thesis, York University, Toronto: ]. [Google Scholar]

- Yim O., Clément R. (2019). “You’re a juksing ”: Examining Cantonese–English code-switching as an index of identity. Journal of Language and Social Psychology, 38(4), 479–495. [Google Scholar]

- Yim O., Clément R. ( in-press). Evaluational Reactions to Degrees of Code-switching among Cantonese-English Bilinguals. (submitted). [Google Scholar]