Abstract

The presence of Porphyromonas gingivalis has been shown to be a risk factor for periodontitis in adults, and Actinobacillus actinomycetemcomitans has been implicated as a pathogen in early-onset periodontitis. Both species have been shown to establish stable colonization in adults. In cross-sectional studies, both A. actinomycetemcomitans and P. gingivalis have been detected in over one-third of apparently healthy children. Information on the stability of colonization with these organisms in children could help to elucidate the natural history of the development of periodontitis. For this purpose, samples previously collected from a cohort of 222 children between the ages of 0 and 18 years and previously examined for the presence of P. gingivalis with a PCR-based assay were examined for the presence of A. actinomycetemcomitans. It was detected in 48% of subjects and, like P. gingivalis, was found at similar frequencies among children of all ages (P = 0.53), suggesting very early initial acquisition. One hundred one of the original subjects were recalled after 1 to 3 years to determine the continuing presence of both A. actinomycetemcomitans and P. gingivalis. The prevalence of both species remained unchanged at resampling. However, in most children both species appeared to colonize only transiently, with random concordance between the results of the first and second sampling. Stability of colonization was unrelated to age for A. actinomycetemcomitans, but P. gingivalis was more stable in the late teenage years.

The majority of adults suffer from some degree of periodontitis, with severe disease affecting 5 to 20% of the population (9). Measurable attachment loss has been observed among 22% of 14- to 17-year-olds in the United States (8), suggesting that periodontal destruction begins very early. One of the most consistent factors associated with signs of adult-onset periodontitis is the presence of Porphyromonas gingivalis. While over 300 species of bacteria have been identified in the oral cavity, P. gingivalis has been consistently associated with indicators of periodontal disease such as deeper pockets, alveolar bone loss, and attachment loss (3, 6, 14, 16, 24, 30). Distinct, early-onset forms of periodontitis affect approximately 0.2% of the population under 20 years of age (4). These cases of periodontitis have been most consistently associated with the presence of Actinobacillus actinomycetemcomitans as the predominant organism in affected sites (4). Little is known of the natural history of the acquisition and stability of either periodontal pathogen. Earlier studies which relied on cultivation for detection of P. gingivalis underestimated its prevalence in young subjects, seldom detecting it before puberty (5, 10, 12, 15, 20, 33, 34). Studies relying on DNA-based technology have demonstrated its presence in a large fraction of young subjects (1, 18, 22) and shown it to be equally common in children at all ages (22). The availability of selective media for A. actinomycetemcomitans has allowed more accurate determination of its prevalence in children by cultivation, and it has been demonstrated to occur in approximately one-quarter to one-half of children using either cultivation or DNA-based methods (1, 2, 10, 13, 18, 27), although investigators were unable to detect it in very young children (12, 19). More information on the acquisition and establishment of periodontal pathogens could help to elucidate the natural history of the development of chronic periodontitis and might provide information important for developing strategies for disease prevention. The purpose of this study was to determine the age at which A. actinomycetemcomitans is acquired and to determine the stability of infection with A. actinomycetemcomitans and P. gingivalis.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

One hundred one children were recalled from two previously sampled cohorts after 1 to 3 years to determine the continuing presence of A. actinomycetemcomitans and P. gingivalis. Seventy-seven children were recalled from a cross-sectional sample of 198 healthy children between the ages of 0 and 18 years from Columbus Children's Hospital (22). Twenty-four children recruited for a study of transmission within families from churches in Columbus, Ohio, were also recalled (31). Verbal consent was obtained from the parent or guardian of minor children for this institutionally approved protocol.

Subjects were examined, and samples were collected with endodontic paper points as previously described (22). The tongue, buccal mucosa, and mesial sulcus of all teeth present were sampled to maximize the likelihood of detection of bacteria if present at any site. Samples from each individual were pooled in a sterile 2-ml microcentrifuge tube and frozen for later analysis.

Samples were analyzed for the presence of A. actinomycetemcomitans or P. gingivalis as previously described with a PCR-based assay (21). Briefly, the samples were eluted from the paper points and the DNA was isolated. The intergenic spacer region (ISR) located between the 16S and 23S ribosomal genes was first amplified by using the universal prokaryotic primers 785 and 422 (22). This was followed by a second nested PCR using either the P. gingivalis-specific primer PG13 (CATCGGTAGTTGCTAACAGTTTTC) or the A. actinomycetemcomitans-specific primer AS2 (GGTAACCAACCAGCGATGGG) and a universal prokaryotic primer, 241 (22). DNA fragments were analyzed by agarose gel electrophoresis (Fig. 1). All amplifications were repeated and scored at least twice.

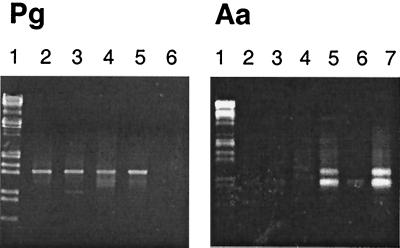

FIG. 1.

DNA fragments amplified directly from plaque. The markers in lane 1 of both panels are EcoRI and HindIII digestion products of bacteriophage lambda DNA. In the left panel, P. gingivalis was detected in the samples shown in lanes 2 to 5 as a band running at approximately 1.4 kb. The sample in lane 6 was negative for P. gingivalis. In the right panel, A. actinomycetemcomitans was detected in the samples shown in lanes 5 and 7 as two bands running at approximately 900 and 1,050 bp. The remaining lanes contain samples that were negative.

Strains from subjects positive for P. gingivalis at both the first and second samplings were compared by heteroduplex analysis of the ribosomal ISR (21a). Briefly, heteroduplexes were formed by mixing amplified ribosomal ISR DNA from two samples, heating the sample to melt the strands, and then cooling to reanneal. Resulting products were analyzed by polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis. A mismatch in the ISR, resulting from mixing fragments from different strains, caused heteroduplex fragments to migrate more slowly and resulted in the appearance of additional bands. ISR fragments from clinical samples were hybridized to a panel of DNA fragments generated from laboratory strains and matched to previously identified migration patterns, allowing strains to be identified (21a).

Chi-square analysis was used to determine the relationship between race or sex and colonization, to compare the observed colonization concordance for the first and second samplings, to examine the colonization concordance by 5-year increments of age, and to examine concurrent colonization with both P. gingivalis and A. actinomycetemcomitans.

Logistic regression was performed to examine both the relationship between age and colonization status and the persistence of colonization and age.

RESULTS

In order to determine the stability of A. actinomycetemcomitans and P. gingivalis, samples from two cohorts of children previously examined for the presence of P. gingivalis were analyzed for the presence of A. actinomycetemcomitans, and these subjects were recalled for follow-up sampling to determine the continuing presence of both organisms. One hundred one subjects were recalled after 1 to 3 years (mean, 2.7; standard deviation [SD], 0.6). The demographics of the original cohort of 198 subjects sampled at Columbus Children's Hospital were previously reported (22). An additional 24 subjects were recalled from a cohort of 564 children examined for another study (31). The combined group of 222 subjects was 45% female and 68% white, 29% African-American, and 3% other races. At the first sampling, subjects ranged in age from 0 to 18 years, with at least 10 subjects for each year of age, with a mean age of 9.0 years (SD, 5.3). Of the 101 subjects who were recalled, 51 were male and 50 were female. The racial distribution was 70 white, 28 African American, and 3 of other races. At resampling, subjects ranged in age from 2 to 20 years, with a mean age of 10.3 years (SD, 4.5).

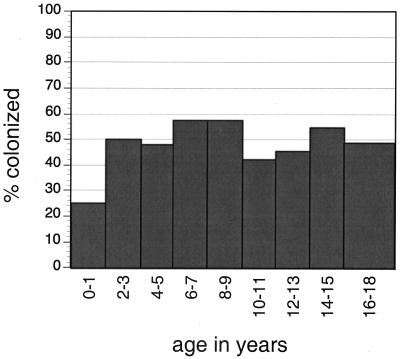

A. actinomycetemcomitans was detected in 107 of 222 subjects (48%) at the first sampling and in 51 of 101 subjects (51%) at the second sampling. P. gingivalis was detected in 80 of 222 subjects (36%) at the first sampling and in 43 of 101 subjects (43%) at the second sampling. Logistic regression analysis showed no relationship between age and colonization with either P. gingivalis (22) or A. actinomycetemcomitans (Fig. 2). No relationship was observed by chi-square analysis between race or sex and colonization with either A. actinomycetemcomitans or P. gingivalis at either the first or second sampling.

FIG. 2.

Percentage of subjects in whom A. actinomycetemcomitans was detected at the first sampling by 2-year age groupings. Logistic regression analysis showed no relationship between age and colonization (P = 0.53).

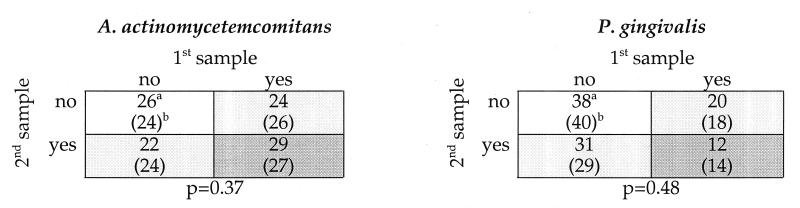

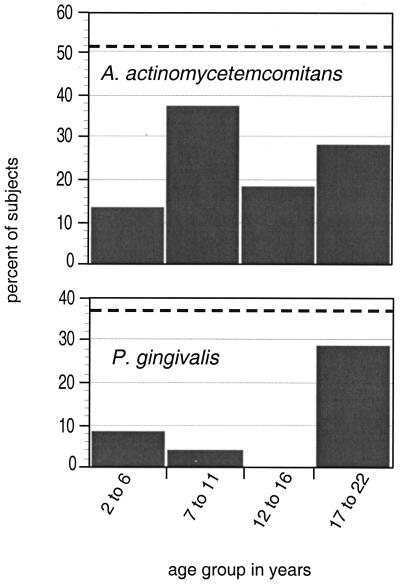

The concordance for the presence of A. actinomycetemcomitans and P. gingivalis at the first and second samplings is shown in Fig. 3. Chi-square analysis revealed no significant association between detection of either organism at the first and second samplings. Logistic regression analysis showed a positive relationship between increasing age and persistent colonization with P. gingivalis. This difference approached statistical significance (P = 0.08). When subjects were stratified by 5-year age increments, significantly more subjects were found to have persistent colonization in the oldest age quartile (P = 0.008 [Fig. 4]). In contrast, no relationship to age was observed for persistent colonization with A. actinomycetemcomitans either by logistic regression or by age stratification and chi-square analysis (Fig. 4). For 11 of the 12 subjects positive for P. gingivalis at both the first and second samplings, matching of strains at the two sampling times was determined by heteroduplex analysis (Table 1). Repeated detection of the same strain was observed only in the oldest quartile.

FIG. 3.

Matrix of concordance of colonization between the first and second samplings for A. actinomycetemcomitans and P. gingivalis. Samples were taken an average of 2.7 (SD, 0.6) years apart for 101 subjects. No significant association between colonization at the first and second sampling times was seen for either species. Light gray shading indicates colonization with a single species, and dark gray shading indicates colonization with both species. a, observed number of subjects; b (values in parentheses), expected number of subjects calculated by chi-square analysis.

FIG. 4.

Percentage of subjects in whom A. actinomycetemcomitans or P. gingivalis was detected at both sampling times by 5-year age groupings. The dashed line indicates the average prevalence of each species for both sampling times. Subjects in the oldest group were more likely to be consistently colonized with P. gingivalis (chi-square, P = 0.008). No other significant relationships were found.

TABLE 1.

Strain comparison in subjects positive for P. gingivalis at both the first and second samplings

| Age of subject (yr) | Strain match |

|---|---|

| 2 | No |

| 6 | No |

| 7 | No |

| 9 | No |

| 9 | No |

| 12 | No |

| 12 | No |

| 17 | Yes |

| 17 | Yes |

| 18 | No |

| 20 | Yes |

A significant positive association for concurrent detection of A. actinomycetemcomitans and P. gingivalis was observed at the first sampling. Both species were detected in 47 of 222 subjects (21%), and chi-square analysis showed an expected value of 39 of 222 subjects (17%). This difference was significant (P = 0.02). At the second sampling, although the number of subjects in whom both species was detected was greater than the expected value, the difference was not significant (P = 0.08).

DISCUSSION

In an earlier study, it was shown that P. gingivalis is often detected in the oral cavities of even very young children and that its presence is unrelated to the age of the child. The overall prevalence of P. gingivalis is similar to that found in adults (14), but it was not known if bacteria acquired during childhood are transient. The relationship of persistent colonization with P. gingivalis to age was examined in the current study. Although the prevalence in the population did not change over 2 years, colonization was not maintained within most individual subjects until the late teenage years, when repeated detection became more common. Strain identification for subjects positive for P. gingivalis at both sampling times showed that strains were stable only in the older subjects (Table 1), although the sample size was too small to permit statistical analysis. The results of this study indicate that colonization is transient in young children but that it may stabilize in the later teenage years. In a previous study, the detection of P. gingivalis in children was shown to be highly dependent upon its presence in other family members (31). Available data indicate that colonization is stable in adults with periodontitis, even with therapy designed to eradicate it (11, 29, 32). In addition, its presence has been shown to be related to deeper probing depths (14, 16). It is likely that contact with an infected individual may allow the transient presence of this anaerobe in the oral cavities of children, but without a permanent niche such as a deep pocket, it does not survive. This raises the interesting possibility that other bacterial species may play a larger role in the incipient stages of periodontitis. Further studies tracking children longitudinally through their development with measurement of probing depth and colonization status with multiple species are needed to test this hypothesis.

A. actinomycetemcomitans was found in 48% of the subjects in the first sample, and like P. gingivalis, its presence was unrelated to the age of the individual. Both species were detected in predentate subjects as young as 20 days old, indicating very early initial acquisition. The prevalence had not changed when subjects were resampled after 2 years, but again, colonization was not maintained within individual subjects. Unlike P. gingivalis, A. actinomycetemcomitans did not stabilize with increasing age. This is consistent with findings that A. actinomycetemcomitans is not related to probing depth in young adults (26), although it does appear to be stable in adults with periodontitis (11, 23, 25, 29, 32).

At the first sampling time, A. actinomycetemcomitans and P. gingivalis were more likely to be found together than would be expected based on a random distribution with respect to each other. The relationship was statistically significant with a sample size of 222 (P = 0.02) but not at the second time point with a smaller sample size of 101 (P = 0.08). This suggests that the relationship, if real, is not strong and could be detected only with the larger sample size. The actual difference was small and probably clinically unimportant. It may perhaps be explained by local environmental factors which favor the growth of subgingival inhabitants, such as poor oral hygiene. Detection of A. actinomycetemcomitans and P. gingivalis has been found to be independent in adults (7).

The specificity of the PCR assays for P. gingivalis and A. actinomycetemcomitans has been previously demonstrated (21, 22), and a search of GenBank demonstrated homology of the primers only to the intended species. The target sequence is located in the ribosomal ISR, which varies in size even among closely related species. PCR products were analyzed by agarose gel electrophoresis, and no size variants were observed, providing additional confirmation of the specificity of the assay.

Since bacterial counts may be low in children in whom an infection has not become well established, the sensitivity of the detection method is important. The PCR assay employed for this study has been shown to detect as few as 10 cells in the presence of 108 cells of another species (21) and is the most sensitive method available. In addition, since subgingival species have not been found to be uniformly distributed throughout the oral cavity and vary in the number of sites colonized in different individuals, sampling strategy can affect detection rates. In order to detect P. gingivalis with 95% confidence, it has been reported that over half of available teeth must be sampled (17). Thus, an intensive sampling strategy including the mesial sulcus of every tooth present plus the tongue and buccal mucosa was employed for this study to maximize the probability of detection. Sterile paper points were used for collection of plaque samples, since they have been shown to recover more CFU than the curette method (28).

In summary, P. gingivalis and A. actinomycetemcomitans are common inhabitants of the oral cavity of child subjects of any age and usually colonize only transiently. P. gingivalis appears to become more stable in the late teenage years, possibly as deeper pockets develop.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We gratefully acknowledge Lucia Gross and Rebecca Robinson for recruiting subjects.

This study was supported by NIH grant DE10467.

REFERENCES

- 1.Abraham J, Stiles H M, Kammerman L A, Forrester D. Assessing periodontal pathogens in children with varying levels of oral hygiene. J Dent Child. 1990;57:189–193. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Alaluusua S, Asikainen S. Detection and distribution of Actinobacillus actinomycetemcomitans in the primary dentition. J Periodontol. 1988;59:504–507. doi: 10.1902/jop.1988.59.8.504. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Alpagot T, Wolff L F, Smith Q T, Tran S D. Risk indicators for periodontal disease in a racially diverse urban population. J Clin Periodontol. 1996;23:982–988. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-051x.1996.tb00524.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.American Academy of Periodontology. Position paper: periodontal diseases of children and adolescents. J Periodontol. 1996;67:57–62. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ashley F P, Gallagher J, Wilson R F. The occurrence of Actinobacillus actinomycetemcomitans, Bacteroides gingivalis, Bacteroides intermedius and spirochaetes in the subgingival microflora of adolescents and their relationship with the amount of supragingival plaque and gingivitis. Oral Microbiol Immunol. 1988;3:77–82. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-302x.1988.tb00086.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Beck J D. Methods of assessing risk for periodontitis and developing multifactorial models. J Periodontol. 1994;65:468–478. doi: 10.1902/jop.1994.65.5s.468. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Becker M R, Griffen A L, Lyons S R, Hazard K R, Leys E J. Prevalence of Actinobacillus actinomycetemcomitans in periodontal health and disease. J Dent Res. 1998;77:228. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bhat M. Periodontal health of 14-17-year-old US schoolchildren. J Public Health Dent. 1991;51:5–11. doi: 10.1111/j.1752-7325.1991.tb02168.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Brown L J, Brunelle J A, Kingman A. Periodontal status in the United States, 1988–1991: prevalence, extent, and demographic variation. J Dent Res. 1996;75:672–683. doi: 10.1177/002203459607502S07. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Delaney J E, Ratzan S K, Kornman K S. Subgingival microbiota associated with puberty: studies of pre-, circum-, and postpubertal human females. Pediatr Dent. 1986;8:268–275. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Flemming T F, Milian E, Kopp C, Karch H, Klaiber B. Differential effects of systemic metronidazole and amoxicillin on Actinobacillus actinomycetemcomitans and Porphyromonas gingivalis in intraoral habitats. J Clin Periodontol. 1998;25:1–10. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-051x.1998.tb02356.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Frisken K W, Higgins T, Palmer J M. The incidence of periodontopathic microorganisms in young children. Oral Microbiol Immunol. 1990;5:43–45. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-302x.1990.tb00225.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Frisken K W, Tagg J R, Laws A J, Orr M B. Suspected periodontopathic microorganisms and their oral habitats in young children. Oral Microbiol Immunol. 1987;2:60–64. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-302x.1987.tb00291.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Griffen A L, Becker M R, Lyons S R, Moeschberger M L, Leys E J. Prevalence of Porphyromonas gingivalis and periodontal health status. J Clin Microbiol. 1998;36:3239–3242. doi: 10.1128/jcm.36.11.3239-3242.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gusberti F A, Mombelli A, Lang N P, Minder C E. Changes in subgingival microbiota during puberty. A 4-year longitudinal study. J Clin Periodontol. 1990;17:685–692. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-051x.1990.tb01054.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Haffajee A D, Cugini M A, Tanner A, Pollack R P, Smith C, Kent R L, Jr, Socransky S S. Subgingival microbiota in healthy, well-maintained elder and periodontitis subjects. J Clin Periodontol. 1998;25:346–353. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-051x.1998.tb02454.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Haffajee A D, Socransky S S. Effect of sampling strategy on the false-negative rate for detection of selected subgingival species. Oral Microbiol Immunol. 1992;7:57–59. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-302x.1992.tb00022.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kisby L E, Savitt E D, French C K, Peros W J. DNA probe detection of key periodontal pathogens in juveniles. J Pedod. 1989;13:222–229. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kononen E, Asikainen S, Jousimies-Somer H. The early colonization of gram-negative anaerobic bacteria in edentulous infants. Oral Microbiol Immunol. 1992;7:28–31. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-302x.1992.tb00016.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kononen E, Asikainen S, Saarela M, Karjalainen J, Jousimies-Somer H. The oral gram-negative anaerobic microflora in young children: longitudinal changes from edentulous to dentate mouth. Oral Microbiol Immunol. 1994;9:136–141. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-302x.1994.tb00049.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Leys E J, Griffen A L, Strong S J, Fuerst P A. Detection and strain identification of Actinobacillus actinomycetemcomitans by nested PCR. J Clin Microbiol. 1994;32:1288–1294. doi: 10.1128/jcm.32.5.1288-1294.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21a.Leys E J, Smith J H, Lyons S R, Griffen A L. Identification of Porphyromonas gingivalis strains by heteroduplex analysis and detection of multiple strains. J Clin Microbiol. 1999;37:3906–3911. doi: 10.1128/jcm.37.12.3906-3911.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.McClellan D L, Griffen A L, Leys E J. Age and prevalence of Porphyromonas gingivalis in children. J Clin Microbiol. 1995;34:2017–2019. doi: 10.1128/jcm.34.8.2017-2019.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Mombelli A, Gmur R, Gobbi C, Lang N P. Actinobacillus actinomycetemcomitans in adult periodontitis. II. Characterization of isolated strains and effect of mechanical periodontal treatment. J Periodontol. 1994;65:827–834. doi: 10.1902/jop.1994.65.9.827. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Moore W E, Moore L H, Ranney R R, Smibert R M, Burmeister J A, Schenkein H A. The microflora of periodontal sites showing active destructive progression. J Clin Periodontol. 1991;18:729–739. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-051x.1991.tb00064.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Muller H P, Heinecke A, Borneff M, Kiencke C, Knopf A, Pohl S. Eradication of Actinobacillus actinomycetemcomitans from the oral cavity in adult periodontitis. J Periodontal Res. 1998;33:49–58. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0765.1998.tb02291.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Muller H P, Zoller L, Eger T, Hoffmann S, Lobinsky D. Natural distribution of oral Actinobacillus actinomycetemcomitans in young men with minimal periodontal disease. J Periodontal Res. 1996;31:373–380. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0765.1996.tb00506.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Nakagawa S, Machida Y, Nakagawa T, Fujii H, Yamada S, Takazoe I, Okuda K. Infection by Porphyromonas gingivalis and Actinobacillus actinomycetemcomitans, and antibody responses at different ages in humans. J Periodontal Res. 1994;29:9–16. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0765.1994.tb01085.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Renvert S, Wikstrom M, Helmersson M, Dahlen G, Claffey N. Comparative study of subgingival microbiological sampling techniques. J Periodontol. 1992;63:797–801. doi: 10.1902/jop.1992.63.10.797. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Shiloah J, Patters M R, Dean J W, 3rd, Bland P, Toledo G. The survival rate of Actinobacillus actinomycetemcomitans, Porphyromonas gingivalis, and Bacteroides forsythus following 4 randomized treatment modalities. J Periodontol. 1997;68:720–728. doi: 10.1902/jop.1997.68.8.720. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Teanpaisan R, Douglas C W, Walsh T F. Characterisation of black-pigmented anaerobes isolated from diseased and healthy periodontal sites. J Periodontal Res. 1995;30:245–251. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0765.1995.tb02129.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Tuite-McDonnell M, Griffen A L, Moeschberger M L, Dalton R E, Fuerst P A, Leys E J. Concordance of Porphyromonas gingivalis colonization in families. J Clin Microbiol. 1997;35:455–461. doi: 10.1128/jcm.35.2.455-461.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.von Troil-Linden B, Saarela M, Matto J, Alaluusua S, Jousimies-Somer H, Asikainen S. Source of suspected periodontal pathogens re-emerging after periodontal treatment. J Clin Periodontol. 1996;23:601–607. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-051x.1996.tb01831.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Wojcicki C J, Harper D S, Robinson P J. Differences in periodontal disease-associated microorganisms of subgingival plaque in prepubertal, pubertal and postpubertal children. J Periodontol. 1987;58:219–223. doi: 10.1902/jop.1987.58.4.219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Yanover L, Ellen R P. A clinical and microbiologic examination of gingival disease in parapubescent females. J Periodontol. 1986;57:562–567. doi: 10.1902/jop.1986.57.9.562. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]