Abstract

Magnesium stable isotope ratios and minor element abundances of five olivine particles from comet 81P/Wild 2 were examined by secondary ion mass spectrometry (SIMS). Wild 2 olivine particles exhibit only small variations in δ25Mg values from −1.0 +0.4/−0.5 ‰ to 0.6 +0.5/− 0.6 ‰ (2σ). This variation can be simply explained by mass-dependent fractionation from Mg isotopic compositions of the Earth and bulk meteorites, suggesting that Wild 2 olivine particles formed in the chondritic reservoir with respect to Mg isotope compositions. We also determined minor element abundances, and O and Mg isotope ratios of olivine grains in amoeboid olivine aggregates (AOAs) from Kaba (CV3.1) and DOM 08006 (CO3.01) carbonaceous chondrites. Our new SIMS minor element data reveal uniform, low FeO contents of ~0.05 wt% among AOA olivines from DOM 08006, suggesting that AOAs formed at more reducing environments in the solar nebula than previously thought. Furthermore, the SIMS-derived FeO contents of the AOA olivines are consistently lower than those obtained by electron microprobe analyses (~1 wt% FeO), indicating possible fluorescence from surrounding matrix materials and/or Fe,Ni-metals in AOAs during electron microprobe analyses. For Mg isotopes, AOA olivines show more negative mass-dependent fractionation (−3.8 ± 0.5‰ ≤ δ25Mg ≤ −0.2 ± 0.3‰; 2σ) relative to Wild 2 olivines. Further, these Mg isotope variations are correlated with their host AOA textures. Large negative Mg isotope fractionations in olivine are often observed in pore-rich AOAs, while those in compact AOAs tend to have near-chondritic Mg isotopic compositions. These observations indicate that pore-rich AOAs preserved their gas-solid condensation histories, while compact AOAs experienced thermal processing in the solar nebula after their condensation and aggregation. Importantly, one 16O-rich Wild 2 LIME olivine particle (T77/F50) shows negative Mg isotope fractionation (δ25Mg = −0.8 ± 0.4‰, δ26Mg = −1.4 ± 0.9‰; 2σ) relative to bulk chondrites. Minor element abundances of T77/F50 are in excellent agreement with those of olivines from pore-rich AOAs in DOM 08006. The observed similarity in O and Mg isotopes, and minor element abundances suggest that T77/F50 formed in an environment similar to AOAs, probably near the proto-Sun, and then was transported to the Kuiper belt, where comet 81P/Wild 2 likely accreted.

1. Introduction

Particles collected from the Jupiter family comet 81P/Wild 2 (NASA Stardust mission) have provided unique opportunities to study materials from the outer Solar System, likely within the Kuiper Belt (Brownlee et al., 2006; 2012; 2014). Wild 2 particles consist of a variety of materials, including presolar grains (McKeegan et al., 2006; Messenger et al., 2009; Leitner et al., 2010, 2012) and organic matter (Sandford et al., 2006; Sandford, 2008; Matrajt et al., 2008) as well as numerous high temperature materials such as Ca, Al-rich inclusions (CAIs; e.g., McKeegan et al., 2006; Zolensky et al., 2006; Chi et al., 2009; Simon et al., 2008; Joswiak et al., 2012; 2017) and ferromagnesian silicates (Nakamura et al., 2008; Bridges et al., 2012; Joswiak et al., 2012; Nakashima et al., 2012; Ogliore et al., 2012; Frank et al., 2014; Gainsforth et al., 2015; Defouilloy et al., 2017). Determining the origins of such particles can shed light on dynamic properties of the solar protoplanetary disk, including transport and processing of comet precursors. For example, the existence of high temperature minerals in Wild 2 suggests that materials originating from the hotter inner part of the solar protoplanetary disk were transported outward to the cooler Kuiper Belt region and eventually accreted to comets (e.g., McKeegan et al., 2006; Ciesla, 2007; Nakamura et al., 2008; Brownlee et al., 2012). In addition, Nakashima et al. (2012) suggested that at least a fraction of the ferromagnesian silicates in comet Wild 2 formed in the outer regions of the asteroid belt, based on the observed similarity of oxygen isotope systematics between Wild 2 particles and chondrules from CR chondrites. Furthermore, Bridges et al. (2012) hypothesize an outer Solar System origin for some Wild 2 silicate particles that have similar oxygen isotope and elemental characteristics when compared to Al-rich chondrules from carbonaceous chondrites. Therefore, at least some Wild 2 silicate particles may also hold information about the physicochemical conditions of the outer Solar System where comets accreted.

In the past decade, oxygen three-isotope ratios of forty-seven Wild 2 silicate particles larger than 2 μm have been acquired by secondary ion mass spectrometry (SIMS) (McKeegan et al., 2006; Nakamura et al., 2008; Nakamura-Messenger et al., 2011; Bridges et al., 2012; Nakashima et al., 2012; Ogliore et al., 2012, 2015; Joswiak et al., 2014; Gainsforth et al., 2015; Defouilloy et al., 2017; Chaumard et al., 2018), and they show a bimodal distribution on an oxygen three-isotope diagram (Fig. 1). The mass-independent fractionation of oxygen isotopes among Wild 2 particles are expressed as Δ17O (= δ17O − 0.52 × δ18O, where δ17,18O = [(17,18O/16O)sample/(17,18O/16O)VSMOW − 1] × 1000; VSMOW = Vienna Standard Mean Ocean Water; Baertschi, 1976), and range from −24‰ to +3‰ for all data with uncertainties smaller than 5‰. Among them, the Δ17O values of thirty-six Wild 2 particles (≥ 2 μm) range from −7‰ to +3‰ (McKeegan et al., 2006; Nakamura et al., 2008; Nakashima et al., 2012; Ogliore et al., 2012, 2015; Joswiak et al., 2014; Gainsforth et al., 2015; Defouilloy et al., 2017; Chaumard et al., 2018), similar to those of chondrules found in chondrites (Tenner et al., 2018a). In contrast, seven Wild 2 particles show more 16O-rich oxygen isotopic characteristics (Δ17O = −24‰ to −20‰). These seven particles are nearly pure forsterite or enstatite, some of which are low-iron, manganese-enriched (LIME) olivines and pyroxenes (Nakashima et al., 2012; Defouilloy et al., 2017; Chaumard et al., 2018). LIME olivines and pyroxenes (hereafter LIME silicates) have MnO/FeO (wt%) ratios much higher than 0.1 and low FeO contents (typically ≤ 1 wt%). As Mn is not stable as metal at solar nebula conditions, it likely condensed at ~1100 K, as Mn2SiO4 in solid solution with forsterite, and as MnSiO3 with enstatite (Larimer, 1967; Wai and Wasson, 1977; Lodders, 2003). In contrast, Fe co-condenses as metal with forsterite (if the oxidation state is below the Fe-FeO buffer), meaning that high MnO/FeO ratios observed in LIME silicates suggest a condensation origin from the solar nebula (Klöck et al., 1989; Weisberg et al., 1993; 2004; Ebel et al., 2012). LIME silicates have been found in chondritic interplanetary dust particles (IDPs) (Klöck et al., 1989) that are believed to have a cometary origin (e.g., Bradley, 2003 and references therein), implying that LIME silicates may have been abundant nebular condensates and they were present in comet accretion regions. Thus, Wild 2 LIME silicates contain important clues for understanding the formation and transportation of solids in the early Solar System.

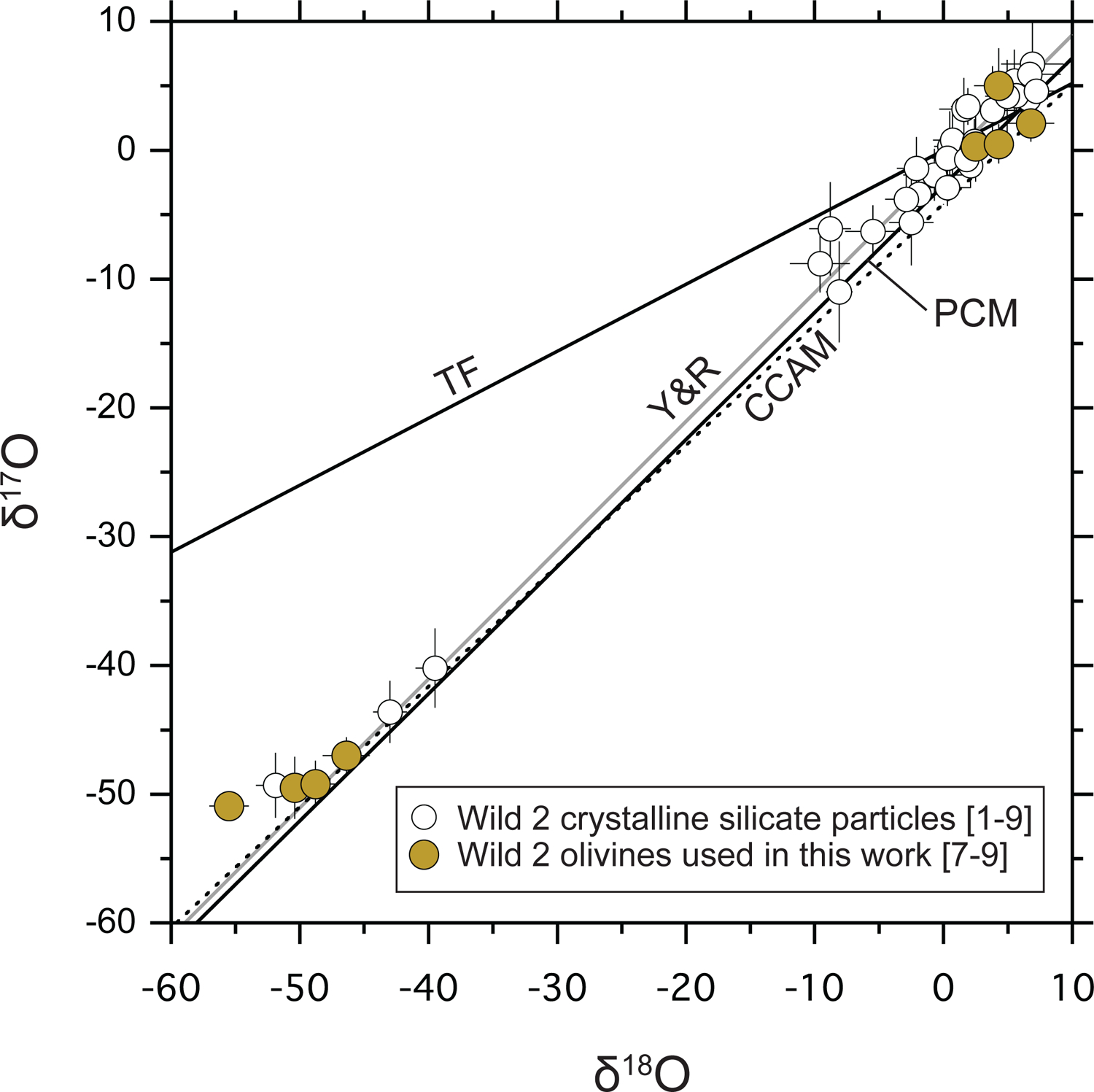

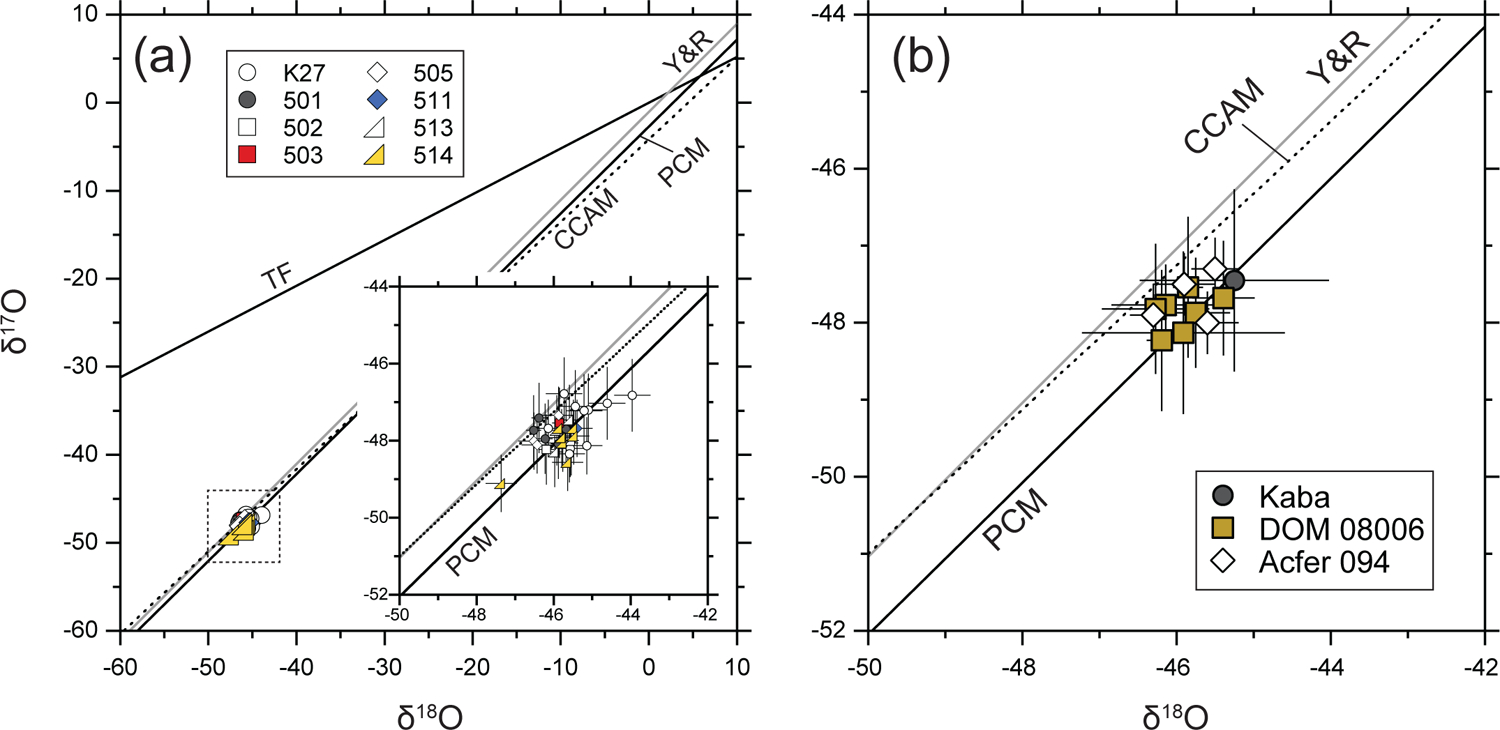

Fig. 1.

Oxygen three-isotope ratios of Wild 2 crystalline silicate particles larger than 2 μm with uncertainties of Δ17O smaller than 5‰. TF, Y&R, CCAM, and PCM represent terrestrial fractionation (Clayton et al., 1991), the Young and Russell (Young and Russell, 1998), the carbonaceous chondrite anhydrous mineral (Clayton et al., 1977), and primitive chondrule mineral (Ushikubo et al., 2012; 2017) lines, respectively. Average values for each particle are shown. Data from [1] McKeegan et al. (2006), [2] Nakamura et al. (2008), [3] Ogliore et al. (2012, 2015), [4] Bridges et al. (2012), [5] Joswiak et al. (2014), [6] Gainsforth et al. (2015), [7] Nakashima et al. (2012), [8] Defouilloy et al. (2017), [9] Chaumard et al. (2018). Two particles, Torajiro and Gozen-sama, that show heterogeneous O isotope ratios within a single particle (Nakamura et al., 2008) are not shown.

LIME silicates are also observed in amoeboid olivine aggregates (AOAs; e.g., Weisberg et al., 2004; Komatsu et al., 2015) that are the most common type of refractory inclusions in carbonaceous chondrites (e.g., Krot et al., 2004a and references therein; Sugiura et al., 2009; Ruzicka et al., 2012; Krot et al., 2014). Based on their irregularly-shaped, porous, and fine-grained textures, AOAs are thought to be aggregates of solids condensed from the solar nebula and appear to have avoided significant melting after aggregation (e.g., Grossman and Steele, 1976; Komatsu et al., 2001, 2009; Krot et al., 2004a and references therein; Weisberg et al., 2004; Sugiura et al., 2009; Han and Brearley, 2015). In addition, Mg stable isotope ratios of AOAs are indicative of a condensation origin. δ25Mg values of bulk AOAs (where δ25Mg = [(25Mg/24Mg)sample/(25Mg/24Mg)DSM-3 − 1] × 1000; per-mil deviation from Mg reference material DSM-3; Galy et al., 2003) range from −2.47‰ to −0.03‰ (Larsen et al., 2011; Olsen et al., 2011), some of which are negatively fractionated from those of bulk chondrites (δ25Mg = −0.15 ± 0.04‰; Teng et al., 2010). In situ SIMS Mg isotope analyses of AOA olivines also show similar variations in δ25Mg values, as low as ~ −2.8‰ (MacPherson et al., 2012; Ushikubo et al., 2017; Marrocchi et al., 2019a). The light isotope enrichments observed in AOAs may be the result of disequilibrium condensation from solar nebula gas due to kinetic isotope fractionation (Richter, 2004). Note that AOAs from the least metamorphosed chondrites are 16O-rich (Δ17O < −20‰; Aléon et al., 2002; Fagan et al., 2004; Krot et al., 2004a; Itoh et al., 2007; Yurimoto et al., 2008 and references therein; Ushikubo et al., 2017; Komatsu et al., 2018). The similarities in oxygen isotope ratios and mineral chemistry (i.e., 16O-rich oxygen isotope signatures and the occurrence of LIME silicates) suggest a genetic link between Wild 2 LIME silicates and AOAs (Nakashima et al., 2012; Defouilloy et al., 2017). However, unlike AOAs, the petrological context of 16O-rich Wild 2 particles is not well understood because most particles have been found as single mineral grains. If these particles formed by disequilibrium condensation, their Mg isotope ratios could be enriched in lighter isotopes (Richter, 2004), which could be used to trace condensation processes. Due to small particle sizes (< 10 μm), Mg isotope data from Wild 2 particles at sub-‰ precision are currently lacking, but would nonetheless be valuable for testing condensation hypotheses for 16O-rich Wild 2 particles.

Here, we report Mg three-isotope ratios and minor element concentrations of eight Wild 2 olivine particles (four that are 16O-rich and four that are 16O-depleted) in order to better understand their formation processes. To obtain high spatial resolution ( ≤ 2 μm) SIMS Mg isotope analyses, we upgraded the WiscSIMS Cameca IMS 1280 with a radio frequency (RF) plasma oxygen ion source (Hertwig et al., 2019) and applied an instrumental bias correction method that combines forsterite endmember values (= Mg/[Mg + Fe] molar %) and secondary ion Mg+/Si+ ratios (Fukuda et al., 2020). We also conducted SIMS O and Mg isotope analyses, and SIMS minor element analyses of olivine grains in AOAs from Kaba (CV3.1; Bonal et al., 2006) and the least metamorphosed CO chondrite DOM 08006 (classified as CO3.00 from Davidson et al., 2019, while we adopt CO3.01 from Fe,Ni-metal analyses of Tenner et al., 2018b), in order to compare their formation histories with those of Wild 2 particles.

2. Wild 2 Samples

Eight Wild 2 olivine particles were analyzed from four Stardust tracks (Track 57, 77, 149, and 175) including one particle from track 57 (T57/F10), four particles from track 77 (T77/F4, T77/F6, T77/F7, and T77/F50), two particles from track 149 (T149/F1 and T149/F11a), and one particle from track 175 (T175/F1). Secondary electron images of the eight Wild 2 olivine particles are shown in Fig. 2. Mineral chemistry and oxygen isotope ratios of these particles have been previously reported (Joswiak et al., 2012; Nakashima et al., 2012; Defouilloy et al., 2017; Chaumard et al., 2018). Oxygen isotope ratios of the eight Wild 2 particles (Nakashima et al., 2012; Defouilloy et al., 2017; Chaumard et al., 2018) are shown in Fig. 1. Four of eight particles are 16O-rich (T57/F10, T77/F6, T77/F50, and T175/F1) while the other four particles are 16O-depleted (T77/F4, T77/F7, T149/F1, and T149/F11a). Fo contents (Fo = Mg/[Mg + Fe] molar %) of the 16O-rich particles range from 98.0 to 99.8, while 16O-depleted particles are more FeO-rich (Fo60–85) (Joswiak et al., 2012; Defouilloy et al., 2017; Chaumard et al., 2018). Among the 16O-rich particles, T77/F6 and T77/F50 were found in the same bulbous track identified as T77 (type B track; Hörz et al., 2006; Burchell et al., 2008; Joswiak et al., 2012). It was suggested that the original projectile was a loose aggregate and that the two 16O-rich particles as well as the other 16O-rich particle in the same track (T77/F104) which are co-linearly aligned were derived from a single grain that fragmented during capture (Joswiak et al., 2012).

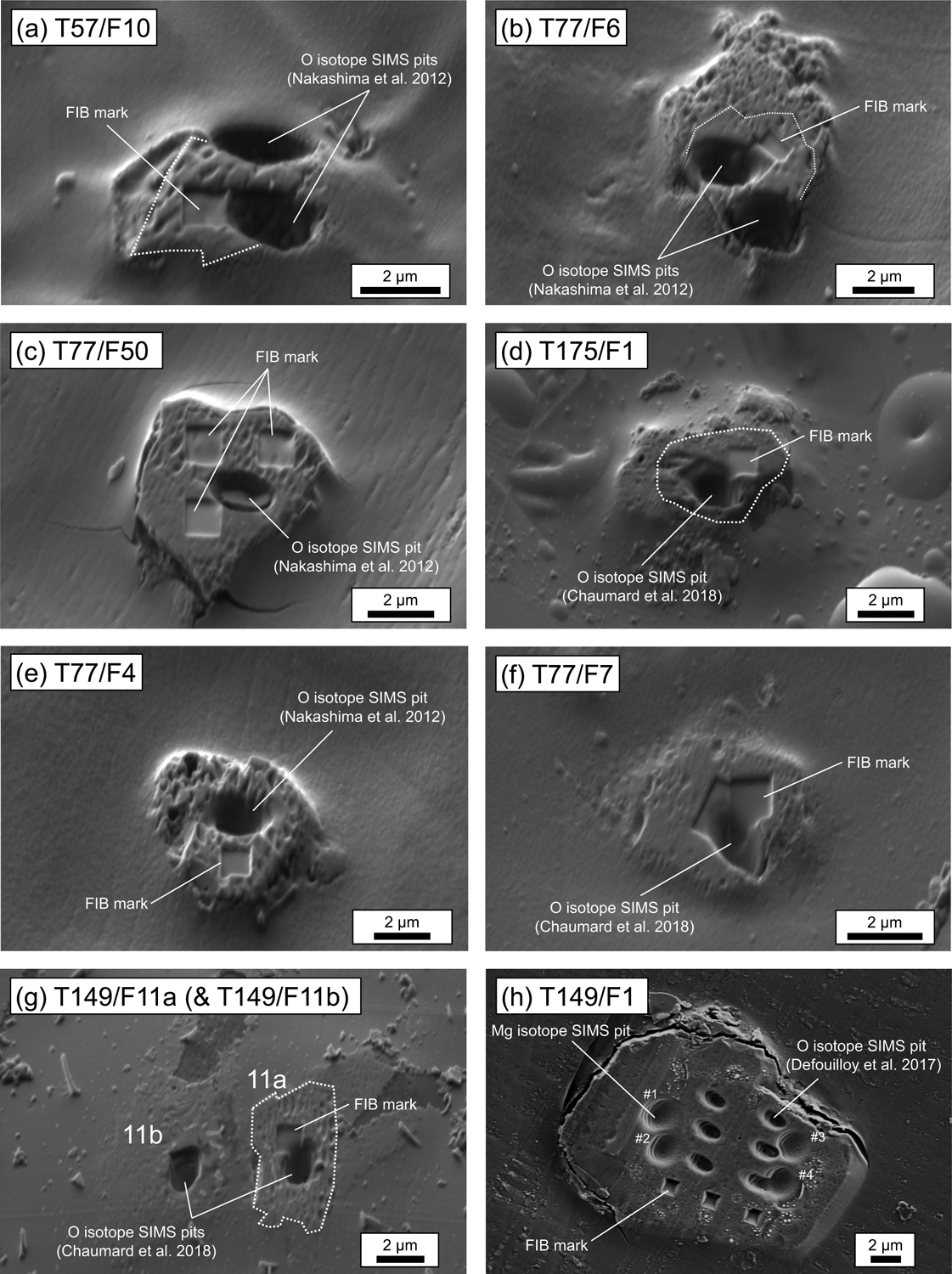

Fig. 2.

SE images of the eight comet 81P/Wild 2 olivine particles before (a-g) and after (h) SIMS Mg isotope analyses. (a-d) 16O-rich olivine particles (a) T57/F10, (b) T77/F6, (c) T77/F50, (d) T175/F1. (e-h) 16O-depleted olivine particles (e) T77/F4, (f) T77/F7, (g) T149/F11a (and T149/F11b; not used in this study), (h) T149/F1. For all images, SIMS pits of previous oxygen isotope analyses are visible (Nakashima et al., 2012; Defouilloy et al., 2017; Chaumard et al., 2018). FIB marks for Mg isotope analyses can be seen as squares at the surface of the grains (a-g). For T149/F1, SIMS pits for 6 oxygen isotope analyses (Defouilloy et al., 2017) and four Mg isotope analyses (this study; #1–4) are visible. Additional images can be found in Electronic Annex EA1.

3. Analytical procedures

3.1. Electron microscopy

Two thin sections, Kaba USNM 1052–1 and DOM 08006, 50, were allocated from the Smithsonian Institution and NASA JSC, respectively. Backscattered electron (BSE) and secondary electron (SE) images of individual AOAs were obtained with a Hitachi S-3400 scanning electron microscope (SEM) at the University of Wisconsin-Madison (UW-Madison). Major and minor elements (Na2O, MgO, Al2O3, SiO2, K2O, CaO, TiO2, Cr2O3, MnO, and FeO) of minerals in AOAs were obtained with a Cameca SXFive FE electron-probe microanalyzer (EPMA) at UW-Madison. EPMA analyses were performed with an accelerating voltage of 15 kV and a beam current of 20 nA, with a 3 micron diameter beam. Off peak backgrounds were acquired, with 10 second counts on the background and 10 seconds on the peaks. The following reference materials (RMs) were used for olivine analyses: Burma jadeite (Na), synthetic forsterite (Mg, Si), Grass Valley anorthite (Al), NMNH 122142 Kakanui augite (Ca), microcline (K), TiO2 oxide (Ti), synthetic Cr2O3 (Cr), synthetic Mn2SiO4 (Mn), and synthetic FeO (Fe). For high-Ca pyroxene analyses, the same suite of RMs were used except for Mg and Si, which were calibrated using NMNH 122142 Kakanui augite. Probe for EPMA™ (PFE) software was used for data reduction. Calculated detection limits (99% confidence) for the measured oxides in wt% were Na2O-0.02, MgO-0.02, Al2O3-0.03, SiO2-0.03, K2O-0.02, CaO-0.02, TiO2-0.05, Cr2O3-0.07, MnO-0.05, and FeO-0.06 wt%.

Endmembers of olivine and pyroxene are expressed as Fo (= Mg/[Mg + Fe] molar %) and En (= Mg/[Mg + Fe + Ca] molar %), respectively. We also report Wo (= Ca/[Mg + Fe + Ca] molar %) as the Ca endmember for pyroxene. The Fo, En, and Wo contents were calculated by considering total iron as ferrous iron.

3.2. FIB marking

All Wild 2 particles studied here have been previously analyzed by SIMS for oxygen isotope ratios (Nakashima et al., 2012; Defouilloy et al., 2017; Chaumard et al., 2018) such that remaining areas for Mg isotope analyses were limited (typically 3 × 3 μm). In order to aim the primary ion beam precisely, we employed focused ion beam (FIB) marking to target areas prior to SIMS analyses (Nakashima et al., 2012; Defouilloy et al., 2017). FIB marking was performed with a field emission (FE) SEM equipped with a FIB system (Zeiss Auriga, UW-Madison), following procedures described in Defouilloy et al. (2017). After FIB marking, high-resolution SE images of all Wild 2 particles (Fig. 2 and Electronic Annex EA1) were obtained using the same instrument and were used for precise aiming of the primary ion beam.

3.3. Secondary ion mass spectrometry (SIMS)

Oxygen three-isotopes, Mg three-isotopes, and minor element analyses were performed with the WiscSIMS Cameca IMS 1280 equipped with the RF plasma ion source at UW-Madison. Five separate sessions (one for O isotopes, three for Mg isotopes, and one for minor elements) were conducted and analytical conditions were optimized for each session described below. Following analytical sessions, SIMS pits were investigated by SEM (S3400 at UW-Madison) or FE-SEM (LEO 1530 at UW-Madison), of which images are shown in Electronic Annex EA1–3.

3.3.1. SIMS oxygen isotope analyses

For oxygen three-isotope analyses of olivine from Kaba and DOM 08006 AOAs, the primary 133Cs+ ion beam was focused to a ~8 μm diameter spot at 0.7 nA. Secondary oxygen ions (16O−, 17O−, and 18O−) were detected simultaneously using multi-collector Faraday cups (FCs) (Kita et al., 2010). To improve precision of δ17O analyses, the FC for 17O− employed a high gain feedback resistor (1012 ohm) that can reduce thermal noise (Electronic Annex EA4–1). The other FCs for 16O− and 18O− employed 1010 ohm and 1011 ohm resistors, respectively. The mass resolving power (MRP) was set to ~2200 for 16O− and 18O−, and 5000 for 17O−. A single analysis took ~7 min, including 100 s of presputtering and baseline measurement, ~80 s for automated centering of secondary ion deflectors (DTFA-X, DTFA-Y), 200 s of integration (10 s × 20 cycles) of the secondary ion signals. At the end of each analysis, 16O1H− was measured automatically to estimate the contribution of the tailing of 16O1H− to the 17O− peak, which was always insignificant (<0.05‰ on δ17O; Electronic Annex EA4–1). A synthetic pure forsterite RM, HN-Ol (δ18O = 8.90‰: Kita et al., 2010), was used as the bracketing standard. The typical secondary 16O− ion intensity when measuring the HN-Ol was 7.5 × 108 counts per second (cps). Ten to fifteen unknown analyses were bracketed by 8 analyses of the HN-Ol standard (4 before and 4 after the unknowns). The external reproducibility of the HN-Ol standard was typically 0.4‰, 0.9‰, and 0.9‰ (2SD) for δ18O, δ17O, and Δ17O, respectively. The external reproducibilities (2SD) for each bracket are assigned as the uncertainties of bracketed unknown analyses. Instrumental biases in δ18O were calibrated based on the bracket HN-Ol analyses. Since all olivine grains in AOAs analyzed are near-pure forsterite (>Fo99), no additional correction depending on Fo contents was applied.

3.3.2. SIMS magnesium isotope analyses

We conducted three sessions for Mg three-isotope analysis of olivine. For each session, the primary O2− ion beam was accelerated by 23 kV (−13 kV at the ion source and +10 kV at the sample surface) to the sample surface and secondary 24Mg+, 25Mg+, and 26Mg+ ions were detected simultaneously using multi-collector FCs (L′2, C, and H1). Secondary ion optics are similar to those described in Kita et al. (2012) and Ushikubo et al. (2013). The MRP at 10% peak height was set to ~2500 and contributions of 48Ca+ and 24Mg1H+ to 24Mg+ and 25Mg+ peaks, respectively, were negligibly small (EA2 in Fukuda et al., 2020). As described below, the primary beam intensity (and size) was optimized depending on the size of unknown samples, which led to different secondary Mg+ ion intensities. Therefore, the combinations of resistors for the multi-collector FCs were optimized for each session. Each analysis duration was ~8–12 min, including 100 s of presputtering, ~100 s for automated centering of the secondary ion deflectors, and ~300–500 s of integration (10 s × 30 cycles for AOA analyses and 10 s × 50 cycles for Wild 2 analyses) of secondary ion signals. The baselines of the three FC detectors were monitored during each presputtering step, and their values were averaged over eight analyses.

Data reduction procedures follow those from Ushikubo et al. (2017). Terrestrial reference 25Mg/24Mg and 26Mg/24Mg values (0.12663 and 0.13932, respectively; Catanzaro et al., 1966) were used to convert raw-measured, background-corrected ratios to delta notation (δ25Mgm and δ26Mgm). The δ25Mg and δ26Mg matrix effects were calibrated based on analyses of ~13 olivine reference materials (RMs), of which Mg isotope ratios in DSM-3 scale (Galy et al., 2003) have been determined by solution nebulization multi-collector inductively coupled plasma mass spectrometry (SN-MC-ICP-MS) or laser ablation MC-ICP-MS (Fukuda et al., 2020). Recently, we found complex matrix effects related to SIMS Mg isotope analyses of olivine, leading to instrumental biases on δ25Mg that could not be fit by a simple regression to Fo contents. Instead, we apply a calibration that uses a combination of Mg+/Si+ signal ratios and Fo contents of olivine (Fukuda et al., 2020). Specifically, instrumental biases are estimated as a function of X = (24Mg+/28Si+)/Fo, where (24Mg+/28Si+) is the secondary ion 24Mg+/28Si+ ratio obtained from SIMS minor element analysis (see section 3.3.3) and where Fo contents of unknown samples were obtained with TEM-EDX (Wild 2 olivine; Joswiak et al., 2012; Nakashima et al., 2012; Defouilloy et al., 2017; Chaumard et al., 2018) or FE-EPMA (AOA olivine; this study).

Magnesium isotope ratios of unknowns are reported as δ25Mg and δ26Mg values in DSM-3 scale. The bias corrected δ25Mg and δ26Mg values are calculated as follows:

where i = 25 or 26 and δiMgbias is the instrumental bias determined from the calibration curve (Electronic Annex EA5). Uncertainties in δ25Mg and δ26Mg are estimated by combining the analytical uncertainties and error of the fit to the instrumental bias correction. More details for the estimation of uncertainties are summarized in Electronic Annex EA5.

The mass-independent raw-measured Δ26Mgm is defined as Δ26Mgm = [(1 + δ26Mgm/1000)/(1 + δ25Mgm/1000)1/ β − 1] × 1000. We assume that natural and instrumental mass-dependent fractionations follow a power law function, where an applied β value of 0.5128 was determined by vacuum evaporation experiments on melts of a Type B CAI bulk composition (Davis et al., 2015). Δ26Mgm values of olivine RMs obtained in the same analysis session were used to correct the non-mass dependent instrumental bias (see more details in Electronic Annex EA5). The mass-independent, bias-corrected Δ26Mg of unknowns is defined as follows:

where Δ26Mgm (unknown) and Δ26Mgm (RM) are Δ26Mgm of unknowns and Δ26Mgm of olivine RMs, respectively. Finally, δ26Mg* of unknowns are estimated as: δ26Mg* = Δ26Mg × (1 + δ25Mg/1000)1/ β (Ushikubo et al., 2017). We note that natural mass-dependent fractionations in Wild 2 and AOA olivines may not follow this power law β value, but that any potential δ26Mg* inaccuracy this causes is likely to be minimal. For example, if assuming kinetic Mg isotope fractionation (β = 0.511; Young and Galy, 2004), the δ26Mg* of Wild 2 and AOA olivines only change by a maximum of 0.03‰ within δ25Mg values ranging from −3.8 to 0.6‰. This small offset is well within our analytical uncertainties (~0.05–0.47‰, 2SD).

The Wild 2 olivine particles were analyzed in session 1 (S1; 2018 Oct). The primary O2− beam was focused to 2 μm at 24 pA. All three FCs employed 1012 ohm resistors for detection of 24, 25, 26Mg+ ions. Prior to each analysis, secondary 25Mg+ ion images of the Wild 2 olivine particles were obtained by rastering the primary ion beam (24pA) over a 10 μm × 10 μm area in order to identify the location of FIB marks. For this mode of operation, the secondary 25Mg+ ions were detected with a multi-collector electron multiplier (EM; L1) by applying X-deflection after the secondary magnet (DSP2X), which is similar to previous techniques for oxygen and magnesium isotope analyses of Wild 2 particles (Nakashima et al., 2012, 2015; Defouilloy et al., 2017). One to four analyses were performed for each Wild 2 particle, bracketed by eight analyses of the San Carlos olivine (hereafter SC-Ol) grains mounted in the same disks. In addition, twelve other olivine RMs were measured for instrumental bias corrections (Electronic Annex EA4–2–1). The typical 24Mg+ count rate during measurement of SC-Ol was 4.6 × 106 cps. The standard deviations of FC baselines over eight analyses were typically 120 cps for L′2, 90 cps for C, and 110 cps for H1, corresponding to 3 × 10−5 relative to 24Mg+ and 1.6 × 10−4 relative to 25Mg+ and 26Mg+ ion intensities. In this session, we estimated the time constant of each 1012 ohm feedback resistor by monitoring the decay of secondary 24, 25, 26Mg+ signals (i.e., after turning off the primary beam) from SC-Ol (Electronic Annex EA4–5). The time constants of the three 1012 ohm feedback resistors range from 0.49 to 0.74 seconds, which are similar to each other. Thus we did not apply any tau corrections (e.g., Pettke et al., 2011). The external reproducibilities (2SD) of δ25Mgm, δ26Mgm, and Δ26Mgm for the SC-Ol bracket standard were 0.25‰, 0.26‰ and 0.47‰, respectively. The final uncertainties including error of the fit to the instrumental bias correction were typically 0.58‰ 1.05‰, and 0.54‰ for δ25Mg, δ26Mg, and δ26Mg*, respectively.

Olivine grains from Kaba AOA (K27) were analyzed in session 2 (S2; 2018 Oct). The primary O2− beam was focused to 10 μm at 2 nA. The FC for 24Mg+ (L′2) employed a 1010 ohm resistor, and the other two FCs for 25Mg+ and 26Mg+ (C and H1) employed 1011 ohm resistors. SC-Ol grains were used as a bracketing standard. In addition, five Mg-rich olivine RMs (>Fo94) listed in Electronic Annex EA4–2–2 were measured for instrumental bias corrections. The typical 24Mg+ count rate for SC-Ol was 4.4 × 108 cps. The external reproducibilities (2SD) of δ25Mgm, δ26Mgm, and Δ26Mgm for the SC-Ol bracket standard were 0.08‰, 0.15‰ and 0.05‰, respectively. The final uncertainties including error of the fit to the instrumental bias correction were typically 0.31‰, 0.60‰, and 0.06‰ for δ25Mg, δ26Mg, and δ26Mg*, respectively.

Olivine grains from DOM 08006 AOAs were analyzed in session 3 (S3; 2018 Dec). The primary O2− beam was focused to ~5 μm at 160 pA. As for Wild 2 analyses, all three FCs employed 1012 ohm resistors for detection of 24,25,26Mg+ ions. SC-Ol grains were used as a bracketing standard. An additional 11 olivine RMs, listed in Electronic Annex EA4–2–3, were measured for instrumental bias corrections. The typical 24Mg+ count rate when measuring SC-Ol was 3.0 × 107 cps. External reproducibilities (2SD) of δ25Mgm, δ26Mgm, and Δ26Mgm for the SC-Ol bracket standard were 0.13‰, 0.22‰ and 0.19‰, respectively. The final uncertainties including error of the fit to the instrumental bias correction were typically 0.44‰ 0.88‰, and 0.23‰ for δ25Mg, δ26Mg, and δ26Mg*, respectively.

3.3.3. SIMS Mg+/Si+ ratios and minor element analyses

Mg+/Si+ ratios and minor element (Ca, Cr, Mn, and Fe) concentrations were obtained using the same analytical conditions reported in Fukuda et al. (2020). Secondary 24Mg+ ions were detected by an axial FC (FC2) with a 1011 ohm resistor. The other secondary ions (23Na+, 27Al+, 28Si+, 40Ca+, 52Cr+, 55Mn+, 56Fe+, and 60Ni+), as well as mass 22.7 (used for stabilizing the magnetic field for 23Na+), were detected by an axial EM that operated in magnetic peak jumping mode. Due to consumption of sample area from prior O and Mg isotope analyses of the Wild 2 olivine particles, we focused the primary O2− beam down to 1.5 μm in diameter (6 pA) and aimed it inside the previous SIMS pits (~2 μm in diameter) from Mg isotope analyses. For AOAs from DOM 08006, the primary ion beam was also aimed inside previous SIMS pits (~5 μm in diameter) from Mg isotope analyses. Prior to each analysis, a secondary 24Mg+ ion image of the targeted SIMS pit was obtained by rastering the primary ion beam (6 pA) over a 10 × 10 μm area in order to aim the primary ion beam inside the SIMS pit. The AOA (K27) from Kaba had abundant areas for minor element analyses so that flat surface areas near the previous SIMS pits from Mg isotope analyses were analyzed. SC-Ol grains were used as a running standard. An additional 12 olivine standards (Electronic Annex EA4–3) were also measured to obtain 24Mg+/28Si+ ratios and to determine relative sensitivity factors (RSFs) of minor elements (Ca, Cr, Mn, and Fe). The typical 24Mg+ count rate for SC-Ol was ~7.6 × 105 cps. We also conducted multiple analyses of olivine RMs in order to compare the instrumental bias within previously generated SIMS pits and flat surface areas (see more details in Electronic Annex EA5). A single analysis was ~6 min in duration, including 100 s of presputtering, ~80 s for automated centering of secondary ion deflectors, and 160 s of integration (32 s × 5 cycles) of secondary ion signals. Detection limits were evaluated based on the measurement of synthetic pure forsterite RM (HN-Ol), which is expected not to contain Ca, Cr, Mn, and Fe. The detection limits of CaO, Cr2O3, MnO, and FeO were 0.002, 0.0001, 0.001, and 0.003 wt%, respectively.

4. RESULTS

4.1. AOA petrography and mineral chemistry

One AOA (K27) from Kaba and eight AOAs (501, 502, 503, 505, 511, 512, 513, and 514) from DOM 08006 were studied by SEM-EDS and FE-EPMA. All nine AOAs are composed of forsteritic olivine, opaque minerals (Fe,Ni-metal and/or weathering products), and Ca-, Al-rich portions (±spinel, ±anorthite, and Al-(Ti)-diopside). Low-Ca pyroxene is rare and was identified in two out of nine AOAs (502 and 503). The mineralogical characteristics of the nine AOAs are summarized in Table 1. The AOAs studied here are less than ~400 μm, except for K27 from Kaba (~1.7 mm). Average elemental compositions (wt%) and Fo, En, and Wo contents of AOA minerals are summarized in Table 2. Individual EPMA data and their analysis locations are summarized in Electronic Annex EA4–4 and EA6, respectively. Olivine grains from the nine AOAs have a narrow range of Fo content (Fo99–100). CaO, Cr2O3, MnO, and FeO contents of olivine grains vary by ~0.4, ~0.5, ~0.5, and ~1.1 wt%, respectively. As we discuss later, FeO contents obtained with EPMA analyses might be overestimated due to secondary fluorescence effects (e.g., Fournelle et al., 2005; Buse et al., 2018) from surrounding FeO enhanced phases. En components of diopside in K27, 505, 511, and 513 range from 44.0 to 50.2. Al2O3 and TiO2 contents of these diopside grains range from 3.4 to 11.9 wt% and 0.2 to 2.9 wt%, respectively.

Table 1.

Mineralogy of AOAs from Kaba (CV3.1) and DOM 08006 (CO3.01) carbonaceous chondrites

| Chondrite | AOA name | AOA texture | fo | FeNi | Ca-, A1-rich portions | LIME o1b | 1px | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| A1-(Ti)-di | an | sp | haloa | |||||||

| Kaba | K27 | compact | + | + | + | + | + | − | − | − |

| DOM 08006 | 501 | pore-rich | + | + | + | + | − | + | + | − |

| DOM 08006 | 502 | pore-rich | + | + | + | + | − | + | + | + |

| DOM 08006 | 503 | pore-rich | + | + | + | + | − | + | + | + |

| DOM 08006 | 505 | compact | + | + | + | − | + | − | + | − |

| DOM 08006 | 511 | pore-rich | + | + | + | + | − | + | + | − |

| DOM 08006 | 512 | pore-rich | + | + | + | + | − | + | + | − |

| DOM 08006 | 513 | compact | + | + | + | + | + | − | − | − |

| DOM 08006 | 514 | pore-rich | + | + | + | + | − | + | − | − |

Diffuse area that appears to be brighter in BSE images than surrounding forsterite. See section 4.1.

Olivine grains with MnO/FeO (wt%) ≥ 1. The MnO/FeO ratios are calculated from SIMS data in Table 4, except for AOA 514.

The MnO/FeO ratios of olivine grains from AOA 514 are calculated from FE-EPMA data due to an absence of SIMS minor element data.

fo = forsterite, FeNi = Fe,Ni-metal and/or weathering products, Al-(Ti)-di = Al-(Ti) diopside, an = anorthite, sp = spinel, LIME ol = LIME olivine, lpx = low-Ca pyroxene

Table 2.

Fo, En, and Wo contents and average elemental compositions (wt%) of minerals in Kaba and DOM 08006 AOAs obtained with electron microprobe.

| Chondrite | AOA name | Minerala | Fob | 1SD | Enb | 1SD | Wob | 1SD | No. of analyses | Na2O | MgO | A12O3 | SiO2 | K2O | CaO | TiO2 | Cr2O3 | MnO | FeO | Total |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Kaba | K27 | fo | 99.9 | 0.1 | 15 | b.d | 57.17 | 0.06 | 42.31 | b.d | 0.15 | 0.06 | 0.20 | 0.10 | 0.19 | 100.23 | ||||

| Kaba | K27 | hpx | 48.9 | 1.4 | 51.1 | 1.4 | 2 | b.d | 17.15 | 5.32 | 50.88 | b.d | 24.88 | 1.94 | 0.11 | b.d | b.d | 100.29 | ||

| DOM 08006 | 501 | fo | 99.5 | 0.3 | 12 | b.d | 57.04 | 0.06 | 42.24 | b.d | 0.19 | 0.05 | 0.16 | 0.11 | 0.49 | 100.34 | ||||

| DOM 08006 | 502 | fo | 99.5 | 0.2 | 7 | b.d | 57.14 | 0.05 | 42.35 | b.d | 0.07 | 0.10 | 0.34 | 0.27 | 0.48 | 100.81 | ||||

| DOM 08006 | 503 | fo | 99.7 | 0.1 | 7 | b.d | 57.61 | 0.05 | 42.50 | b.d | 0.09 | 0.06 | 0.22 | 0.10 | 0.34 | 100.96 | ||||

| DOM 08006 | 505 | fo | 99.8 | 0.1 | 7 | b.d | 57.56 | 0.04 | 42.15 | b.d | 0.11 | 0.06 | 0.20 | 0.12 | 0.18 | 100.41 | ||||

| DOM 08006 | 505 | hpx | 50.1 | 0.1 | 49.6 | 0.2 | 3 | b.d | 18.12 | 3.87 | 53.00 | b.d | 24.92 | 0.28 | 0.09 | b.d | 0.20 | 100.48 | ||

| DOM 08006 | 511 | fo | 99.5 | 0.1 | 7 | b.d | 57.36 | 0.04 | 42.17 | b.d | 0.12 | 0.05 | 0.13 | 0.16 | 0.54 | 100.56 | ||||

| DOM 08006 | 511 | hpx | 45.1 | 1.6 | 54.3 | 1.4 | 2 | b.d | 14.90 | 10.17 | 47.95 | b.d | 24.90 | 2.07 | 0.10 | b.d | 0.35 | 100.44 | ||

| DOM 08006 | 511 | an | 1 | 0.03 | 0.55 | 35.94 | 42.55 | b.d | 19.84 | 0.07 | 0.08 | b.d | 0.37 | 99.43 | ||||||

| DOM 08006 | 512 | fo | 99.7 | 0.1 | 7 | b.d | 57.35 | 0.08 | 42.32 | b.d | 0.09 | 0.08 | 0.27 | 0.15 | 0.27 | 100.61 | ||||

| DOM 08006 | 513 | fo | 99.6 | 0.1 | 7 | b.d | 57.32 | 0.04 | 42.44 | b.d | 0.33 | 0.05 | 0.10 | b.d | 0.40 | 100.69 | ||||

| DOM 08006 | 513 | hpx | 47.9 | 1.1 | 51.4 | 1.2 | 4 | b.d | 16.63 | 6.85 | 50.15 | b.d | 24.83 | 1.38 | 0.10 | b.d | 0.46 | 100.40 | ||

| DOM 08006 | 514 | fo | 99.7 | 0.2 | 7 | b.d | 57.40 | 0.07 | 42.36 | b.d | 0.35 | 0.07 | 0.07 | b.d | 0.33 | 100.65 |

fo = forsterite, hpx = high-Ca pyroxene, an = anorthite

Fo = Mg/(Mg + Fe) molar %, En = Mg/(Mg + Fe + Ca) molar %, Wo = Ca/(Mg + Fe + Ca) molar %.

The AOAs investigated show variations in abundances of pores, shapes of external margins and ratios of minor minerals to olivine (Figs. 3–5). Three (K27, 505 and 513) show a compact texture with little porosity in the forsterite-rich regions (Fig. 3). The other AOAs (e.g., 502 and 503) are more porous and are irregularly shaped (Figs. 4–5). Detailed information for each inclusion is summarized below.

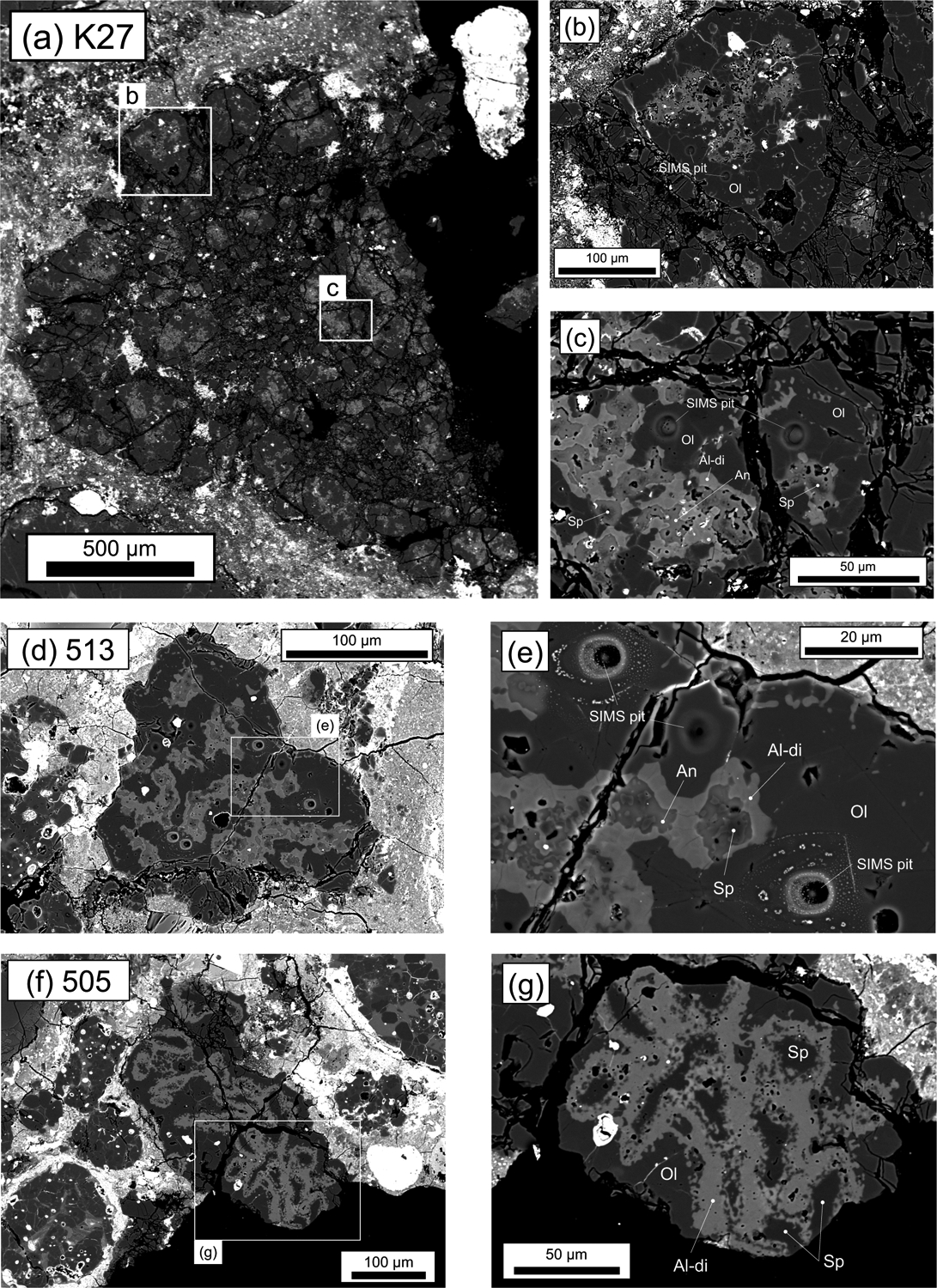

Fig. 3.

BSE images of compact AOAs from Kaba and DOM 08006. (a-c) K27 from Kaba, (d-e) 513 from DOM 08006, (f-g) 505 from DOM 08006. Mineral phases shown are olivine (Ol), anorthite (An), spinel (Sp) and Al diopside (Al-di).

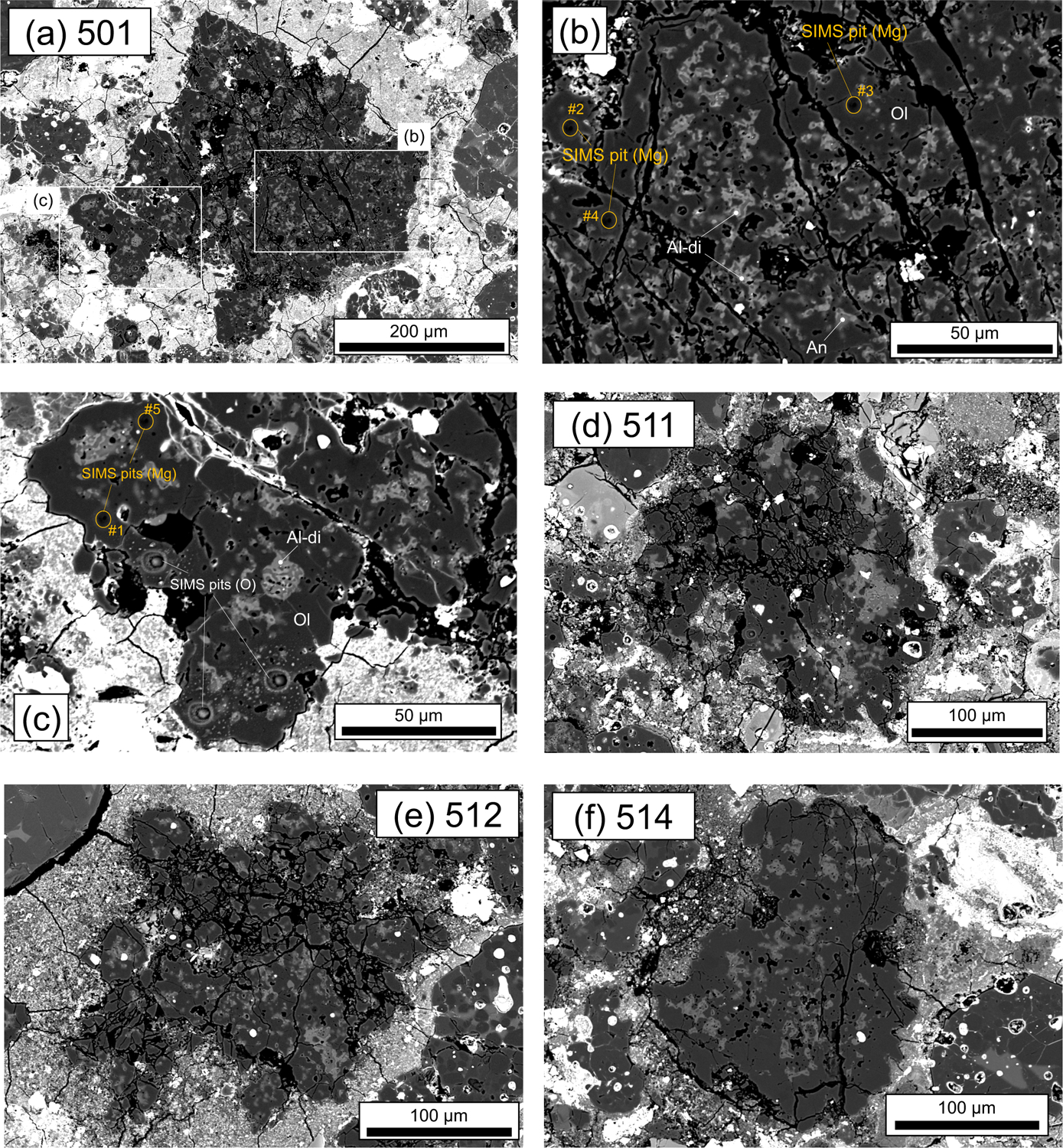

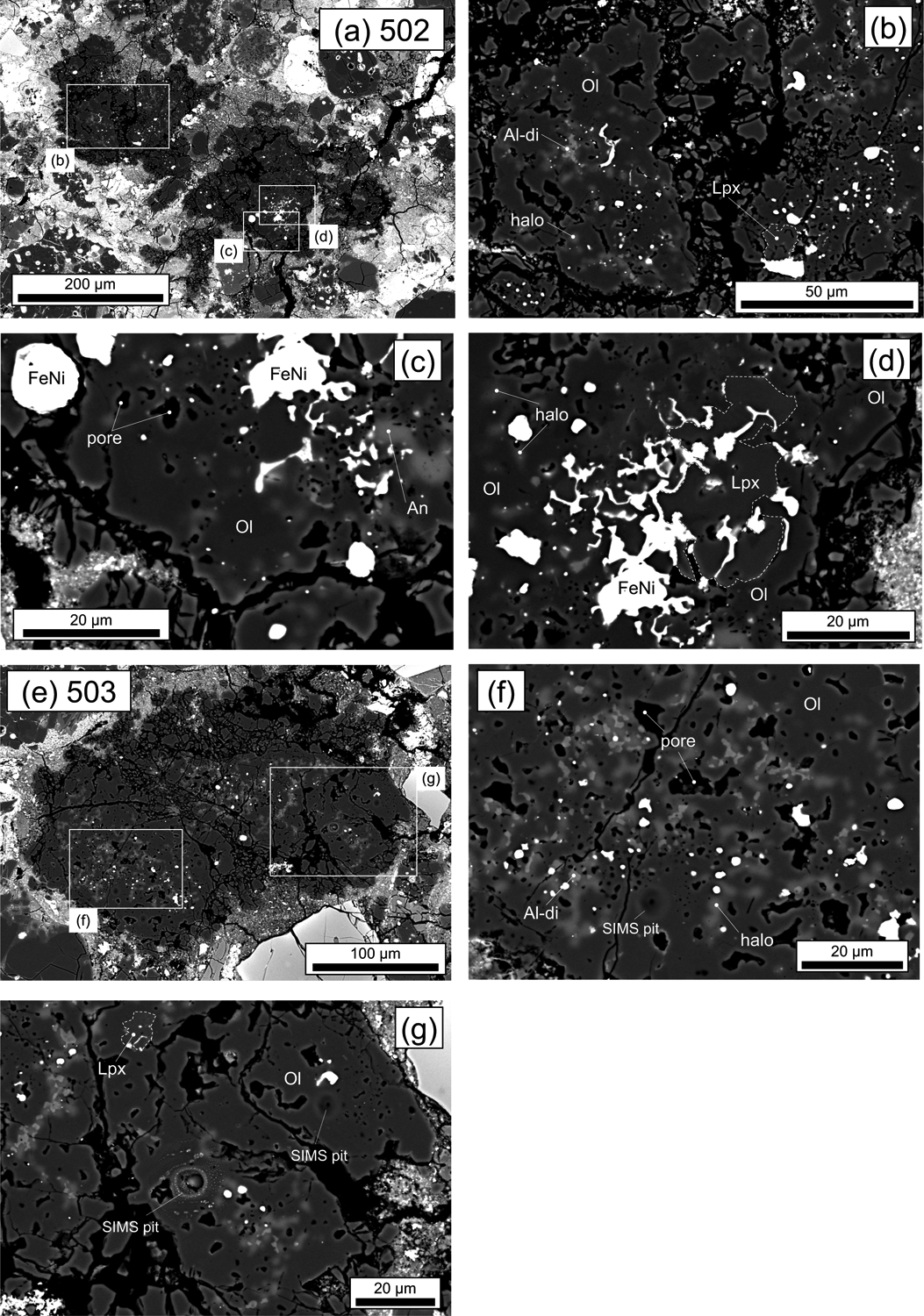

Fig. 5.

BSE images of pore-rich AOAs from DOM 08006. (a) 501, (b) pore-rich lithology in 501, (c) compact lithology in 501, (d) 511, (e) 512, (f) 514. The locations of Mg isotope analyses for pore-rich and compact lithologies in AOA 501 are indicated in (b-c). Mineral phases shown are olivine (Ol), Al-diopside (Al-di) and anorthite (An).

Fig. 4.

BSE images of pore-rich, low-Ca pyroxene-bearing AOAs from DOM 08006. (a-d) 502, (e-g) 503. Mineral phases shown are olivine (Ol), low-Ca pyroxene (Lpx), Al diopside (Al-di), anorthite (An) and Fe,Ni-metal (FeNi). Pores, and haloes that represent diffuse area consisting of mixtures of tiny Al-diopside grains and forsterite, are indicated.

AOA K27 from Kaba is the largest aggregate (~1.7 mm; Fig. 3a) studied here. It consists of multiple nodules, and each nodule is composed of Ca-, Al-rich domains enclosed by sinuous forsterite (Fo99.5–100) and opaque minerals (Fig. 3b). Forsterite regions display dense textures with little porosity between grain boundaries (Figs. 3b and c). Ca-, Al-rich domains have anorthite ± spinel cores rimmed by Al-diopside (Fig. 3c). Spinel grains are anhedral and appear corroded by the surrounding anorthite (Fig. 3c). Al-diopside occurs between anorthite and forsterite (Figs. 3b and c).

AOA 513 from DOM 08006 (Fig. 3d) consists of multiple Ca-, Al-rich portions enclosed by nearly pure forsterite grains (Fo99.5-99.7) and rare Fe,Ni-metal. This AOA has anorthite ± anhedral spinel cores rimmed by Al-diopside, which are enclosed by dense forsterite (Fig. 3e). Al-diopside occurs between anorthite and forsterite (Fig. 3e). The mineralogy and texture of this AOA are similar to those of Kaba AOA K27 (Figs. 3b and c).

AOA 505 from DOM 08006 (Fig. 3f) consists of spinel-diopside-rich nodules enclosed by dense forsterite (Fo99.7–99.9) with minor Fe,Ni-metal. This inclusion may also be classified as a CAI with a thick forsterite rim. Spinel is separated from forsterite by a layer of Al-diopside (Fig. 3g).

AOA 502 from DOM 08006 is irregularly shaped and porous (Fig. 4a), consisting mostly of forsterite (Fo99.3–99.7), with minor Fe,Ni-metal and numerous irregularly shaped diffuse areas (Figs. 4b–d). Rare low-Ca pyroxene is also observed (Figs. 4b and d), and forsterite regions of this AOA are porous (Figs. 4b and c). SEM-EDS analyses indicate that the diffuse areas are mixtures of tiny Al-diopside grains, and forsterite. Such diffuse areas are also observed in AOAs from ALHA77307 (CO3.03) as brighter areas in BSE images than surrounding forsterite, referred to as haloes by Sugiura et al. (2009). Forsterite grains within this AOA have the highest MnO abundances (~0.5 wt%) among the nine AOAs studied here.

AOA 503 from DOM 08006 is a fine-grained, porous object (Fig. 4e), consisting mostly of forsterite (Fo99.4–99.8), with minor Fe,Ni-metal and numerous irregularly shaped Ca-, Al-rich portions (tiny Al-diopside grains and an anorthitic halo; Fig. 4f). Rare low-Ca pyroxene is also observed (Fig. 4g). The mineralogy and texture of this AOA is similar to those of AOA 502, but MnO contents of forsterite grains are lower (~0.1 wt%).

AOA 501 from DOM 08006 (Fig. 5a) consists of forsterite (Fo99.0–99.9), Fe,Ni-metal, and numerous irregularly shaped, fine-grained Ca, Al-rich portions. Most of this AOA is composed of porous forsterite with numerous irregularly shaped, fine-grained Ca, Al-rich portions (Fig. 5b). However, a region shown in Fig. 5c is less porous, and has nodule-like (Ca-, Al-rich core and sinuous forsterite) textures, similar to characteristics observed in Kaba AOA K27 (e.g. Fig. 3b).

AOAs 511 and 512 from DOM 08006 are irregularly shaped objects (Figs. 5d and 5e, respectively), consisting of forsterite (Fo99.3–99.6), Ca-, Al-rich portions (Al-diopside and anorthite), and minor Fe,Ni-metal. Ca, Al-rich diffuse areas (haloes) are observed in each AOA.

AOA 514 from DOM 08006 is a sub-rounded object (Fig. 5f), consisting of forsterite (Fo99.2–99.9) and irregularly shaped Ca-, Al-rich portions (Al-diopside and anorthite) that are concentrated in the inner part of the AOA. Forsterite grains of the inner part of the AOA, along with Ca, Al-rich portions, are more porous relative to the outer regions of this AOA.

4.2. Oxygen isotope ratios of AOA olivines

We obtained 32 olivine oxygen isotope ratio data from eight of the nine AOAs studied here (the exception being AOA 512, due to small olivine grains). δ18O, δ17O, and Δ17O values are reported in Table 3. Raw-measured O isotope ratios of AOA olivines are reported in Electronic Annex EA4–1. As shown in Fig. 6a, oxygen isotope ratios of all measured AOA olivines are 16O-rich (Δ17O ≤ −23‰) and plot either on the Primitive Chondrule Mineral (PCM; Ushikubo et al., 2012; 2017) line or between the PCM and CCAM (Carbonaceous Chondrite Anhydrous Mineral; Clayton et al., 1977) lines. Individual olivine analyses from the eight AOAs have limited variations in δ18O and Δ17O values, ranging from −44.0‰ to −47.4‰ and −23.0‰ to −24.8‰, respectively. Subtle variations of oxygen isotope ratios are observed within each AOA (e.g., K27 and 514; Fig. 6a), but averaged oxygen isotope ratios of individual AOAs form a tight cluster on the PCM line (Fig. 6b), and are identical within uncertainties.

Table 3.

Oxygen isotope ratios of AOA olivines from Kaba and DOM 08006

| Sample/Location #a | δ18O (‰) | Unc. (2σ) | δ17O (‰) | Unc. (2σ) | Δ17O (‰) | Unc. (2σ) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Kaba(CV3.1) | |||||||

| K27 | |||||||

| #1 | −44.6 | 0.5 | −47.0 | 0.9 | −23.8 | 1.0 | |

| #2 | −45.1 | 0.5 | −47.2 | 0.9 | −23.7 | 1.0 | |

| #3 | −44.0 | 0.5 | −46.8 | 0.9 | −24.0 | 1.0 | |

| #4 | −45.2 | 0.5 | −47.2 | 0.9 | −23.7 | 1.0 | |

| #5 | −45.7 | 0.5 | −46.8 | 0.9 | −23.0 | 1.0 | |

| #6 | −45.4 | 0.5 | −47.1 | 0.9 | −23.5 | 1.0 | |

| #7 | −45.6 | 0.4 | −48.2 | 0.7 | −24.5 | 0.7 | |

| #8 | −45.1 | 0.4 | −48.1 | 0.7 | −24.7 | 0.7 | |

| #9 | −45.6 | 0.4 | −48.3 | 0.7 | −24.6 | 0.7 | |

| #10 | −46.1 | 0.4 | −47.7 | 0.7 | −23.7 | 0.7 | |

| Average & 2SD | −45.2 | 1.2 | −47.5 | 1.2 | −23.9 | 1.1 | |

| DOM 08006 (CO3.01) | |||||||

| 501 | |||||||

| #1 | −46.4 | 0.2 | −47.4 | 0.9 | −23.3 | 0.8 | |

| #2 | −45.7 | 0.2 | −47.7 | 0.9 | −23.9 | 0.8 | |

| #3 | −46.2 | 0.2 | −47.9 | 0.9 | −23.9 | 0.8 | |

| #4 | −45.9 | 0.2 | −48.1 | 0.9 | −24.2 | 0.8 | |

| #5 | −46.5 | 0.2 | −47.7 | 0.9 | −23.5 | 0.8 | |

| Average & 2SD | −46.1 | 0.7 | −47.8 | 0.5 | −23.8 | 0.7 | |

| 502 | |||||||

| #1 | −46.2 | 0.2 | −48.2 | 0.9 | −24.2 | 0.8 | |

| 503 | |||||||

| #1 | −45.9 | 0.2 | −47.5 | 0.9 | −23.7 | 0.8 | |

| 505 | |||||||

| #1 | −46.5 | 0.4 | −48.0 | 0.7 | −23.8 | 0.7 | |

| #2 | −45.9 | 0.4 | −47.3 | 0.7 | −23.5 | 0.7 | |

| #3 | −46.4 | 0.4 | −48.1 | 0.7 | −24.0 | 0.7 | |

| Average & 2SD | −46.3 | 0.7 | −47.8 | 0.8 | −23.8 | 0.5 | |

| 511 | |||||||

| #1 | −45.4 | 0.4 | −47.7 | 0.7 | −24.1 | 0.7 | |

| 513 | |||||||

| #1 | −45.5 | 0.2 | −48.0 | 0.9 | −24.3 | 0.8 | |

| #2 | −46.0 | 0.2 | −48.3 | 0.9 | −24.4 | 0.8 | |

| #3 | −45.9 | 0.2 | −47.7 | 0.9 | −23.9 | 0.8 | |

| #4 | −45.6 | 0.2 | −47.5 | 0.9 | −23.8 | 0.8 | |

| Average & 2SD | −45.8 | 0.4 | −47.9 | 0.7 | −24.1 | 0.6 | |

| 514 | |||||||

| #1 | −45.5 | 0.4 | −47.7 | 0.7 | −24.0 | 0.7 | |

| #2 | −45.9 | 0.4 | −47.7 | 0.7 | −23.8 | 0.7 | |

| #3 | −45.8 | 0.4 | −48.1 | 0.7 | −24.3 | 0.7 | |

| #4 | −47.4 | 0.4 | −49.1 | 0.7 | −24.5 | 0.7 | |

| #5 | −45.5 | 0.4 | −47.9 | 0.7 | −24.2 | 0.7 | |

| #6 | −45.6 | 0.4 | −48.6 | 0.7 | −24.8 | 0.7 | |

| #7 | −45.8 | 0.4 | −47.9 | 0.7 | −24.1 | 0.7 | |

| Average & 2SD | −45.9 | 1.3 | −48.1 | 1.1 | −24.3 | 0.7 | |

Analysis points are shown in Electronic Annex EA2.

Fig. 6.

Oxygen three-isotope ratios of the eight AOA olivines from Kaba (K27) and DOM 08006 (501, 502, 503, 505, 511, 513, 514). All measured data (= individual olivine analyses) are shown in (a). The insert in (a) shows detail of the analyses highlighted by the dotted box. Average δ17, 18O values of each AOA are shown in (b), though for three AOAs (502, 503, 511) only a single analysis was collected. For comparison, data for AOAs from Acfer 094 (Ushikubo et al., 2017) are also shown in (b). Reference lines are the terrestrial fractionation (TF), the carbonaceous chondrite anhydrous mineral (CCAM), the Young and Russell (Y&R), and the primitive chondrule mineral (PCM) lines. Errors are 2SD for data obtained in this study. Errors for Acfer 094 data are propagated, as described in Ushikubo et al. (2017).

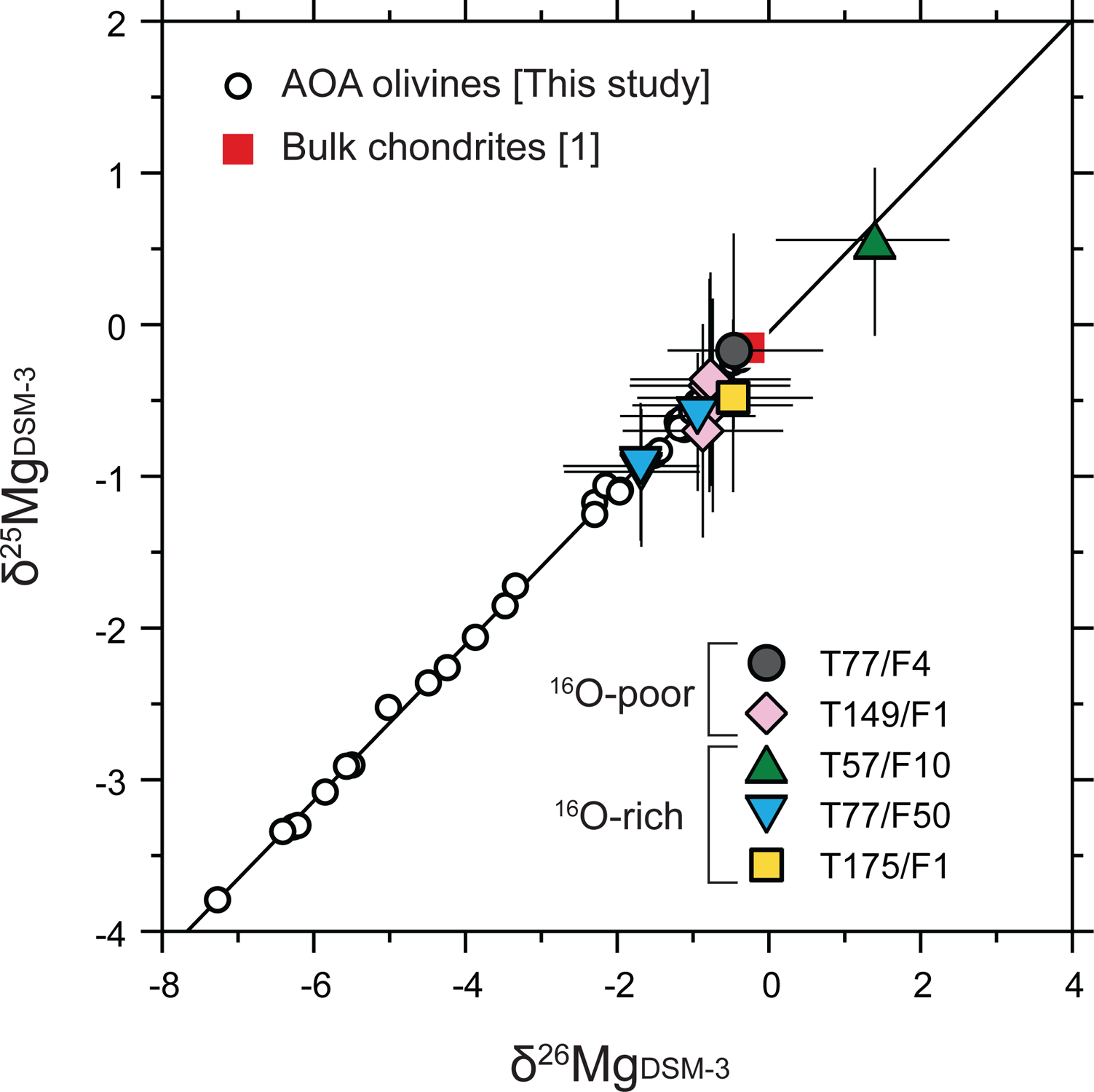

4.3. Magnesium isotope ratios of AOA and Wild 2 olivines

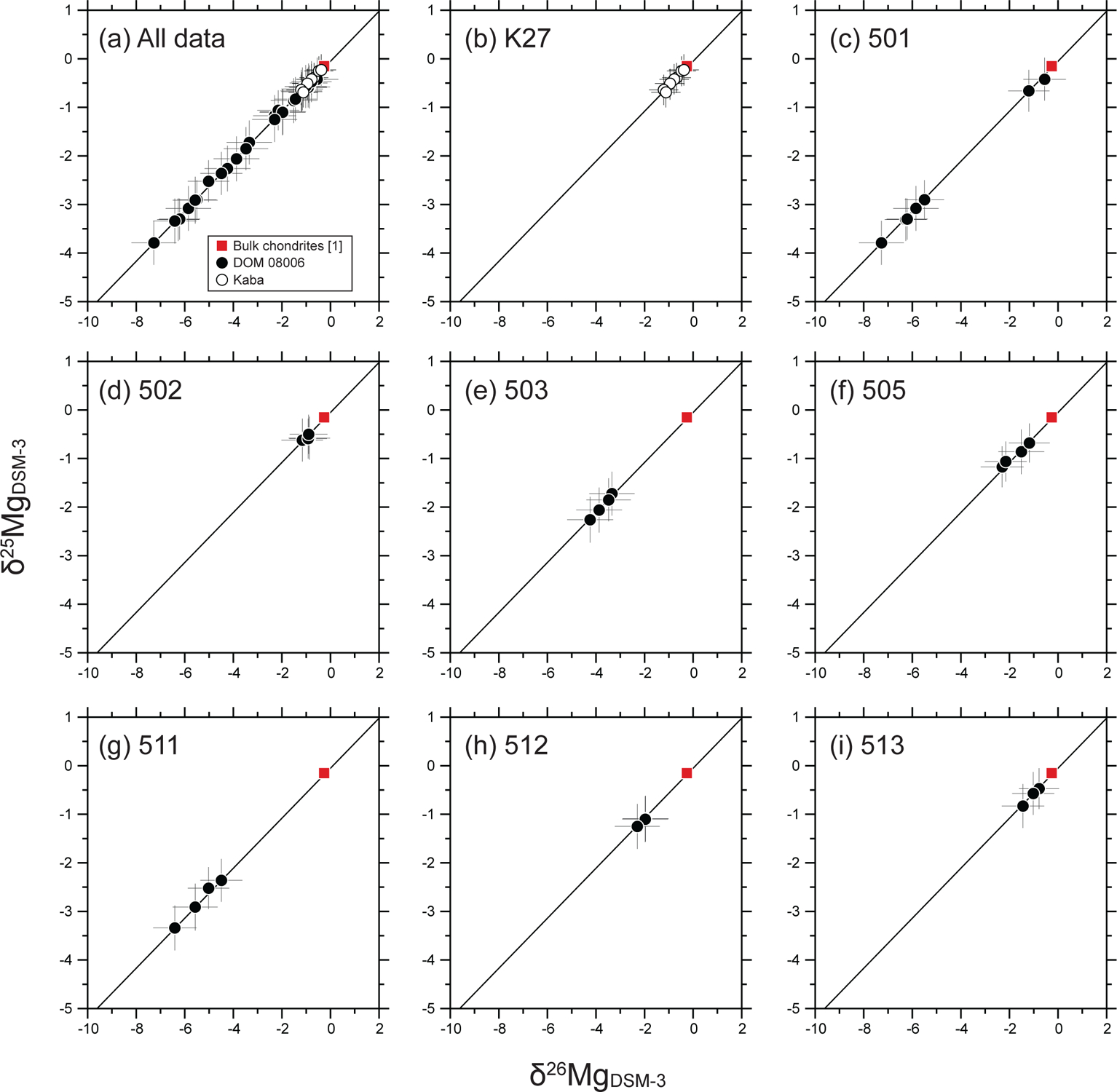

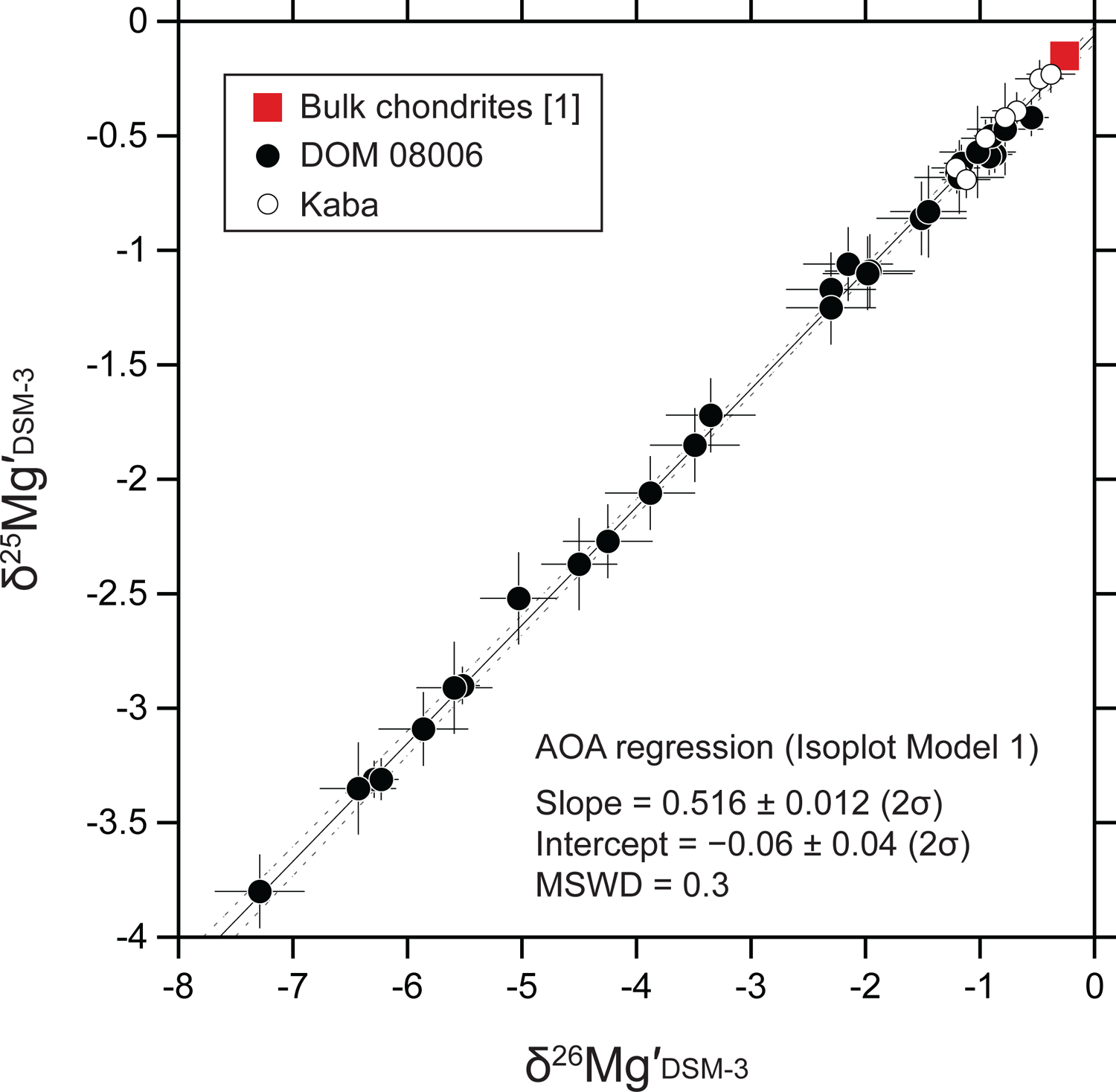

We obtained 36 olivine magnesium three-isotope ratio data from eight of the nine AOAs studied here. We did not acquire Mg isotope data from AOA 514 because large secondary deflector values (DTFA values > 50) had to be applied, and under such a condition δ25Mg analyses are inaccurate due to additional instrument fractionation. Magnesium isotope ratios (δ25Mg and δ26Mg) are listed in Table 4 and plotted in Fig. 7. Individual SIMS data including raw-measured Mg isotope ratios are reported in Electronic Annex EA4–2–6 and EA4–2–7. δ25Mg values of AOA olivines range from −3.8 ± 0.5‰ (2σ) to −0.2 ± 0.3‰ (2σ). All Mg isotope analyses obtained in AOA olivines show a linear correlation between δ26Mg and δ25Mg (Fig. 7a). We also calculated logarithmic values (δ25Mg′ and δ26Mg′) that are converted from δ25Mg and 26Mg values using the following formula: δiMg′ = 1000 × ln (1 + δiMg/1000) (Electronic Annex EA4–2–8). The logarithmic values are used to determine the slope and intercept in δ26Mg′ versus δ25Mg′ space (Fig. 8), with values of 0.516 ± 0.012 (2σ) and −0.06 ± 0.04 (2σ), respectively (using Isoplot 4.15 model 1; Ludwig, 2012). Variation in δ25Mg and δ26Mg within each AOA is identified, which follows a line with the same slope of 0.516 (Figs. 7b–i). Among them, δ25Mg and δ26Mg values of AOA 501 are bimodally distributed on the slope 0.516 line (Fig. 7c).

Table 4.

Magnesium isotope ratios and minor elemental abundances of AOA olivine from Kaba and DOM 08006 obtained with SIMS

| Sample/Location #a | δ25Mgdcm-3 (‰) | Unc. (+/−) (2σ) | δ26Mgdsm-3 (‰) | Unc. (+/−) (2σ) | δ26Mg* (‰) | Unc. (2σ) | CaO (wt%) | Unc. (2σ) | Cr2O3 (wt%) | Unc. (2σ) | FeO (wt%) | Unc. (2σ) | MnO (wt%) | Unc. (2σ) | MnO/FeO | Unc. (2σ) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Kaba (CV3.1) | ||||||||||||||||||||

| K27 | ||||||||||||||||||||

| #3b | −0.39 | 0.30 | 0.31 | −0.68 | 0.59 | 0.59 | 0.04 | 0.06 | 0.128 | 0.004 | 0.110 | 0.007 | 0.324 | 0.017 | 0.027 | 0.002 | 0.08 | 0.01 | ||

| #4 | −0.42 | 0.31 | 0.31 | −0.78 | 0.60 | 0.60 | −0.01 | 0.06 | 0.150 | 0.005 | 0.081 | 0.005 | 0.064 | 0.002 | 0.008 | 0.002 | 0.13 | 0.04 | ||

| #5 | −0.25 | 0.30 | 0.31 | −0.48 | 0.59 | 0.59 | −0.03 | 0.06 | 0.158 | 0.005 | 0.083 | 0.005 | 0.065 | 0.003 | 0.008 | 0.001 | 0.12 | 0.02 | ||

| #6 | −0.51 | 0.30 | 0.33 | −0.95 | 0.59 | 0.62 | 0.00 | 0.06 | 0.230 | 0.022 | 0.057 | 0.004 | 0.116 | 0.003 | 0.009 | 0.001 | 0.08 | 0.01 | ||

| #7 | −0.64 | 0.31 | 0.31 | −1.21 | 0.60 | 0.60 | −0.01 | 0.06 | 0.202 | 0.017 | 0.113 | 0.007 | 0.072 | 0.003 | 0.024 | 0.001 | 0.34 | 0.02 | ||

| #8 | −0.69 | 0.31 | 0.31 | −1.12 | 0.60 | 0.60 | 0.16 | 0.06 | 0.136 | 0.005 | 0.105 | 0.007 | 0.081 | 0.003 | 0.007 | 0.002 | 0.09 | 0.02 | ||

| #9b | −0.23 | 0.32 | 0.32 | −0.38 | 0.61 | 0.61 | 0.01 | 0.06 | 0.089 | 0.006 | 0.138 | 0.012 | 0.184 | 0.006 | 0.098 | 0.004 | 0.53 | 0.03 | ||

| Average & 2SD | −0.45 | 0.35 | 0.35 | −0.80 | 0.63 | 0.63 | 0.02 | 0.13 | 0.156 | 0.094 | 0.098 | 0.037 | 0.129 | 0.192 | 0.026 | 0.066 | 0.20 | 0.59 | ||

| DOM 08006 (CO3.01) | ||||||||||||||||||||

| 501 | ||||||||||||||||||||

| #1_outer left partc | −0.42 | 0.44 | 0.44 | −0.55 | 0.87 | 0.87 | 0.17 | 0.24 | 0.119 | 0.003 | 0.188 | 0.006 | 0.072 | 0.003 | 0.088 | 0.001 | 1.21 | 0.06 | ||

| #2 | −3.31 | 0.44 | 0.44 | −6.27 | 0.86 | 0.86 | 0.09 | 0.24 | 0.082 | 0.002 | 0.177 | 0.010 | 0.073 | 0.002 | 0.108 | 0.004 | 1.49 | 0.07 | ||

| #3 | −2.90 | 0.40 | 0.40 | −5.50 | 0.80 | 0.80 | 0.10 | 0.24 | 0.165 | 0.005 | 0.100 | 0.005 | 0.058 | 0.002 | 0.032 | 0.003 | 0.55 | 0.05 | ||

| #4 | −3.30 | 0.42 | 0.42 | −6.21 | 0.84 | 0.84 | 0.15 | 0.24 | 0.189 | 0.004 | 0.072 | 0.003 | 0.052 | 0.001 | 0.028 | 0.002 | 0.54 | 0.04 | ||

| #5_outer left partc | −0.66 | 0.43 | 0.43 | −1.20 | 0.85 | 0.85 | 0.01 | 0.24 | 0.151 | 0.005 | 0.117 | 0.005 | 0.071 | 0.003 | 0.078 | 0.007 | 1.10 | 0.11 | ||

| #6 | −3.79 | 0.45 | 0.45 | −7.27 | 0.92 | 0.92 | 0.05 | 0.21 | 0.128 | 0.003 | 0.093 | 0.004 | 0.059 | 0.002 | 0.051 | 0.003 | 0.87 | 0.06 | ||

| #7 | −3.08 | 0.46 | 0.46 | −5.85 | 0.93 | 0.93 | 0.05 | 0.21 | 0.142 | 0.003 | 0.163 | 0.005 | 0.073 | 0.002 | 0.093 | 0.003 | 1.28 | 0.05 | ||

| Average (outer left) & 2SD | −0.54 | 0.34 | 0.34 | −0.87 | 0.93 | 0.93 | 0.09 | 0.24 | 0.135 | 0.046 | 0.153 | 0.100 | 0.072 | 0.003 | 0.083 | 0.014 | 1.16 | 0.21 | ||

| Average (#2–4 & #6–7) & 2SD | −3.28 | 0.67 | 0.67 | −6.22 | 1.32 | 1.32 | 0.09 | 0.08 | 0.142 | 0.081 | 0.121 | 0.093 | 0.063 | 0.019 | 0.063 | 0.073 | 0.99 | 1.19 | ||

| 502 | ||||||||||||||||||||

| #1 | −0.62 | 0.44 | 0.44 | −1.16 | 0.85 | 0.85 | −0.05 | 0.24 | 0.033 | 0.001 | 0.320 | 0.011 | 0.063 | 0.002 | 0.074 | 0.003 | 1.18 | 0.06 | ||

| #2 | −0.58 | 0.44 | 0.44 | −0.87 | 0.85 | 0.85 | 0.14 | 0.24 | 0.045 | 0.002 | 0.316 | 0.010 | 0.078 | 0.004 | 0.084 | 0.004 | 1.08 | 0.08 | ||

| #3 | −0.59 | 0.41 | 0.41 | −0.92 | 0.77 | 0.77 | 0.13 | 0.24 | 0.037 | 0.002 | 0.321 | 0.011 | 0.075 | 0.002 | 0.314 | 0.015 | 4.20 | 0.23 | ||

| #4 | −0.50 | 0.40 | 0.40 | −0.90 | 0.77 | 0.77 | −0.03 | 0.24 | 0.037 | 0.001 | 0.295 | 0.010 | 0.072 | 0.002 | 0.283 | 0.002 | 3.92 | 0.10 | ||

| Average & 2SD | −0.57 | 0.11 | 0.11 | −0.96 | 0.26 | 0.26 | 0.05 | 0.21 | 0.038 | 0.010 | 0.313 | 0.017 | 0.072 | 0.013 | 0.189 | 0.255 | 2.62 | 3.57 | ||

| 503 | ||||||||||||||||||||

| #1 | −1.72 | 0.45 | 0.45 | −3.34 | 0.93 | 0.93 | −0.07 | 0.21 | 0.039 | 0.001 | 0.212 | 0.008 | 0.062 | 0.003 | 0.088 | 0.002 | 1.42 | 0.07 | ||

| #2 | −1.85 | 0.44 | 0.44 | −3.48 | 0.91 | 0.91 | 0.06 | 0.21 | 0.063 | 0.001 | 0.164 | 0.006 | 0.061 | 0.002 | 0.024 | 0.002 | 0.40 | 0.04 | ||

| #3 | −2.06 | 0.46 | 0.46 | −3.87 | 0.94 | 0.94 | 0.05 | 0.21 | 0.052 | 0.003 | 0.195 | 0.008 | 0.063 | 0.002 | 0.042 | 0.002 | 0.67 | 0.05 | ||

| #4 | −2.26 | 0.47 | 0.47 | −4.24 | 0.94 | 0.94 | 0.06 | 0.21 | 0.052 | 0.002 | 0.152 | 0.005 | 0.072 | 0.004 | 0.067 | 0.003 | 0.93 | 0.07 | ||

| Average & 2SD | −1.97 | 0.48 | 0.48 | −3.74 | 0.81 | 0.81 | 0.03 | 0.13 | 0.051 | 0.020 | 0.181 | 0.039 | 0.065 | 0.010 | 0.055 | 0.056 | 0.86 | 0.87 | ||

| 505 | ||||||||||||||||||||

| #1 | −0.86 | 0.46 | 0.46 | −1.51 | 0.94 | 0.94 | 0.08 | 0.21 | 0.060 | 0.001 | 0.259 | 0.010 | 0.080 | 0.004 | 0.135 | 0.006 | 1.70 | 0.11 | ||

| #2 | −0.68 | 0.40 | 0.40 | −1.18 | 0.84 | 0.84 | 0.13 | 0.21 | 0.079 | 0.003 | 0.128 | 0.004 | 0.058 | 0.003 | 0.026 | 0.002 | 0.45 | 0.05 | ||

| #3 | −1.17 | 0.42 | 0.42 | −2.30 | 0.88 | 0.88 | −0.06 | 0.21 | 0.066 | 0.002 | 0.179 | 0.006 | 0.062 | 0.002 | 0.073 | 0.002 | 1.18 | 0.05 | ||

| #4 | −1.06 | 0.41 | 0.41 | −2.15 | 0.86 | 0.86 | −0.10 | 0.21 | 0.075 | 0.003 | 0.129 | 0.004 | 0.057 | 0.002 | 0.019 | 0.002 | 0.33 | 0.03 | ||

| Average & 2SD | −0.94 | 0.44 | 0.44 | −1.79 | 1.05 | 1.05 | 0.02 | 0.22 | 0.070 | 0.017 | 0.174 | 0.087 | 0.064 | 0.021 | 0.063 | 0.108 | 0.99 | 1.71 | ||

| 511 | ||||||||||||||||||||

| #1 | −2.36 | 0.44 | 0.44 | −4.49 | 0.86 | 0.86 | 0.08 | 0.25 | 0.090 | 0.002 | 0.096 | 0.006 | 0.046 | 0.003 | 0.020 | 0.003 | 0.44 | 0.06 | ||

| #2 | −2.91 | 0.48 | 0.48 | −5.57 | 0.92 | 0.92 | 0.00 | 0.25 | 0.077 | 0.002 | 0.123 | 0.005 | 0.044 | 0.003 | 0.090 | 0.005 | 2.02 | 0.16 | ||

| #3 | −2.52 | 0.43 | 0.43 | −5.02 | 0.85 | 0.85 | −0.15 | 0.25 | 0.101 | 0.002 | 0.128 | 0.007 | 0.044 | 0.001 | 0.095 | 0.002 | 2.14 | 0.08 | ||

| #4 | −3.34 | 0.46 | 0.46 | −6.41 | 0.89 | 0.89 | 0.03 | 0.25 | 0.109 | 0.005 | 0.113 | 0.007 | 0.056 | 0.003 | 0.005 | 0.001 | 0.09 | 0.01 | ||

| Average & 2SD | −2.78 | 0.87 | 0.87 | −5.37 | 1.64 | 1.64 | −0.01 | 0.20 | 0.094 | 0.027 | 0.115 | 0.020 | 0.048 | 0.011 | 0.052 | 0.093 | 1.10 | 1.97 | ||

| 512 | ||||||||||||||||||||

| #1 | −1.09 | 0.47 | 0.47 | −1.96 | 0.94 | 0.94 | 0.05 | 0.21 | 0.040 | 0.001 | 0.273 | 0.009 | 0.068 | 0.002 | 0.215 | 0.003 | 3.18 | 0.10 | ||

| #2 | −1.10 | 0.47 | 0.47 | −1.97 | 0.94 | 0.94 | 0.06 | 0.21 | 0.037 | 0.001 | 0.233 | 0.008 | 0.068 | 0.002 | 0.088 | 0.002 | 1.28 | 0.05 | ||

| #3 | −1.25 | 0.46 | 0.46 | −2.30 | 0.92 | 0.92 | 0.03 | 0.21 | 0.032 | 0.001 | 0.245 | 0.008 | 0.066 | 0.002 | 0.048 | 0.002 | 0.73 | 0.04 | ||

| Average & 2SD | −1.15 | 0.18 | 0.18 | −2.08 | 0.38 | 0.38 | 0.05 | 0.04 | 0.036 | 0.008 | 0.250 | 0.029 | 0.067 | 0.003 | 0.117 | 0.174 | 1.74 | 2.59 | ||

| 513 | ||||||||||||||||||||

| #1 | −0.47 | 0.42 | 0.42 | −0.78 | 0.82 | 0.82 | 0.13 | 0.25 | 0.269 | 0.006 | 0.055 | 0.003 | 0.042 | 0.003 | 0.0039 | 0.0009 | 0.09 | 0.02 | ||

| #2 | −0.83 | 0.45 | 0.45 | −1.44 | 0.87 | 0.87 | 0.12 | 0.25 | 0.249 | 0.006 | 0.062 | 0.004 | 0.032 | 0.001 | 0.0046 | 0.0011 | 0.14 | 0.03 | ||

| #3 | −0.57 | 0.44 | 0.44 | −1.02 | 0.86 | 0.86 | 0.06 | 0.25 | 0.283 | 0.007 | 0.078 | 0.004 | 0.039 | 0.001 | 0.0040 | 0.0005 | 0.10 | 0.01 | ||

| Average & 2SD | −0.62 | 0.37 | 0.37 | −1.08 | 0.67 | 0.67 | 0.10 | 0.08 | 0.267 | 0.035 | 0.065 | 0.017 | 0.038 | 0.010 | 0.004 | 0.001 | 0.11 | 0.04 | ||

Analysis points are shown in Electronic Annex EA3.

Average values are listed for minor element data. Individual data are reported in Electronic Annex EA4–3–3.

These data are obtained from an outer left part of AOA 501, which shows compact textures relative to the most part of this AOA.

Fig. 7.

Magnesium-three isotope ratios of the eight AOA olivines from Kaba and DOM 08006. All measured data are shown in (a). (b-i) Individual AOA diagrams from Kaba (b) and DOM 08006 (c-i). Square symbols represent the Mg isotope ratios of bulk chondrites ([1] Teng et al., 2010). Solid lines represent a best-fit line for all the measured data determined by a least squares fitting (Ludwig, 2012). Errors are 2σ.

Fig. 8.

Relationships between δ25Mg′DSM-3 and δ26Mg′DSM-3 values of individual AOA olivine analyses. The square symbol represents the Mg isotope ratios of bulk chondrites ([1] Teng et al., 2010). The solid line represents a linear regression line (Isoplot model 1; Ludwig, 2012) for all AOA data (N = 36) obtained in this study. The dotted curves are error envelopes that show 95% confidence limits. Note that uncertainties of δ25Mg′DSM-3 and δ26Mg′DSM-3 values were not propagated from those related to instrumental mass fractionation. See more details in Electronic Annex EA5.

Magnesium isotope ratios (δ25Mg and δ26Mg) of Wild 2 olivine particles T57/F10, T77/F4, T77/F50, T149/F1, and T175/F1 are listed in Table 5 and plotted in Fig. 9. Difficulties with the analyses of three Wild 2 particles (T77/F6, T77/F7, and T149/F11a) or data reduction problems prevented the reporting of bias-corrected δ25Mg and δ26Mg values. For analyses of T77/F6 and T77/F7, (Mg+/Si+/Fo) values of these particles are outside the range of the instrumental fractionation calibration curve, meaning we could not properly correct data for instrumental mass fractionation. For T149/F11a, we observed that the Mg ion yields and δ25Mgm values changed significantly during the analysis. These changes were not observed among olivine RM analyses, meaning we could not properly correct data for instrumental mass fractionation. More detailed explanations for these three particles can be found in Electronic Annex EA7. All individual data, including raw-measured Mg isotope ratios of the eight Wild 2 particles, are reported in Electronic Annex EA4–2–5. Regarding the five Wild 2 particles for which Mg isotope ratios were successfully determined, they show slight variations in δ25Mg, ranging from −1.0 +0.4/−0.5‰ (2σ) to 0.6 +0.5/−0.6‰ (2σ). The Mg isotopic data from these five Wild 2 particles fall on the same slope 0.516 line that is defined by individual AOA olivines (Fig. 9). Particles T77/F50 and T149/F1 were analyzed multiple times (N = 3 and N = 4, respectively) and do not show intra-grain variations in δ25Mg and δ26Mg values beyond uncertainties (Table 5 and Fig. 9).

Table 5.

Magnesium isotope ratios and minor elemental abundances of Wild 2 olivine particles obtained with SIMS

| Sample/Location #a | δ25Mgdsm-3 (‰) | Unc. (+/−) (2σ) | δ26Mgdsm-3 (‰) | Unc. (+/−) (2σ) | δ26Mg* (‰) | Unc. (2σ) | CaO (wt%) | Unc. (2σ) | Cr2O3 (wt%) | Unc. (2σ) | FeO (wt%) | Unc. (2σ) | MnO (wt%) | Unc. (2σ) | MnO/FeO | Unc. (2σ) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 16O-depleted particles | |||||||||||||||||||

| T77/F4 | |||||||||||||||||||

| #1 | −0.17 | 0.77 | 0.51 | −0.46 | 1.17 | 0.87 | −0.07 | 0.43 | 0.186 | 0.015 | 0.07 | 0.01 | 29.72 | 0.99 | 0.481 | 0.005 | 0.016 | 0.001 | |

| T149/F1 | |||||||||||||||||||

| #1 | −0.53 | 0.70 | 0.70 | −0.74 | 1.05 | 1.05 | −0.06 | 0.76 | 0.115 | 0.009 | 0.51 | 0.05 | 12.24 | 0.41 | 0.332 | 0.008 | 0.027 | 0.001 | |

| #2 | −0.40 | 0.70 | 0.70 | −0.78 | 1.05 | 1.05 | −0.33 | 0.76 | 0.116 | 0.009 | 0.53 | 0.06 | 12.84 | 0.43 | 0.342 | 0.008 | 0.027 | 0.001 | |

| #3 | −0.36 | 0.70 | 0.70 | −0.77 | 1.05 | 1.05 | −0.41 | 0.76 | --- | --- | --- | --- | --- | --- | --- | --- | --- | --- | |

| #4 | −0.70 | 0.70 | 0.70 | −0.87 | 1.05 | 1.05 | 0.16 | 0.76 | --- | --- | --- | --- | --- | --- | --- | --- | --- | --- | |

| Average & 2SD | −0.50 | 0.30 | 0.30 | −0.79 | 0.11 | 0.11 | −0.16 | 0.52 | 0.116 | 0.001 | 0.52 | 0.03 | 12.54 | 0.85 | 0.337 | 0.014 | 0.027 | 0.002 | |

| 16O-rich particles | |||||||||||||||||||

| T57/F10 | |||||||||||||||||||

| #1 | 0.56 | 0.47 | 0.63 | 1.40 | 0.97 | 1.30 | 0.15 | 0.45 | 0.043 | 0.003 | 0.42 | 0.05 | 1.75 | 0.06 | 0.664 | 0.016 | 0.38 | 0.02 | |

| T77/F50 | |||||||||||||||||||

| #1 | −0.97 | 0.41 | 0.49 | −1.68 | 0.76 | 1.01 | 0.08 | 0.71 | --- | --- | --- | --- | --- | --- | --- | --- | --- | --- | |

| #2 | −0.93 | 0.41 | 0.49 | −1.69 | 0.76 | 1.01 | −0.01 | 0.70 | 0.031 | 0.002 | 0.31 | 0.03 | 0.065 | 0.003 | 0.247 | 0.004 | 3.80 | 0.16 | |

| #3 | −0.60 | 0.41 | 0.49 | −0.94 | 0.76 | 1.01 | 0.11 | 0.70 | --- | --- | --- | --- | --- | --- | --- | --- | --- | --- | |

| Average &2SD | −0.83 | 0.40 | 0.40 | −1.44 | 0.87 | 0.87 | 0.06 | 0.13 | |||||||||||

| T175/F1 | |||||||||||||||||||

| #1 | −0.48 | 0.51 | 0.62 | −0.47 | 1.04 | 1.26 | 0.31 | 0.37 | 0.0038 | 0.0003 | 0.15 | 0.02 | 0.151 | 0.015 | 0.055 | 0.004 | 0.37 | 0.05 | |

Analysis points are shown in Electronic Annex EA1.

Fig. 9.

Magnesium-three isotope ratios of the five Wild 2 olivine particles studied. The red square symbol represents the Mg isotope ratios of bulk chondrites ([1] Teng et al., 2010). All measured AOA data (Fig. 7a) are shown for comparison. Errors for Wild 2 olivine data are 2σ. For clarity, errors for AOA data are not shown.

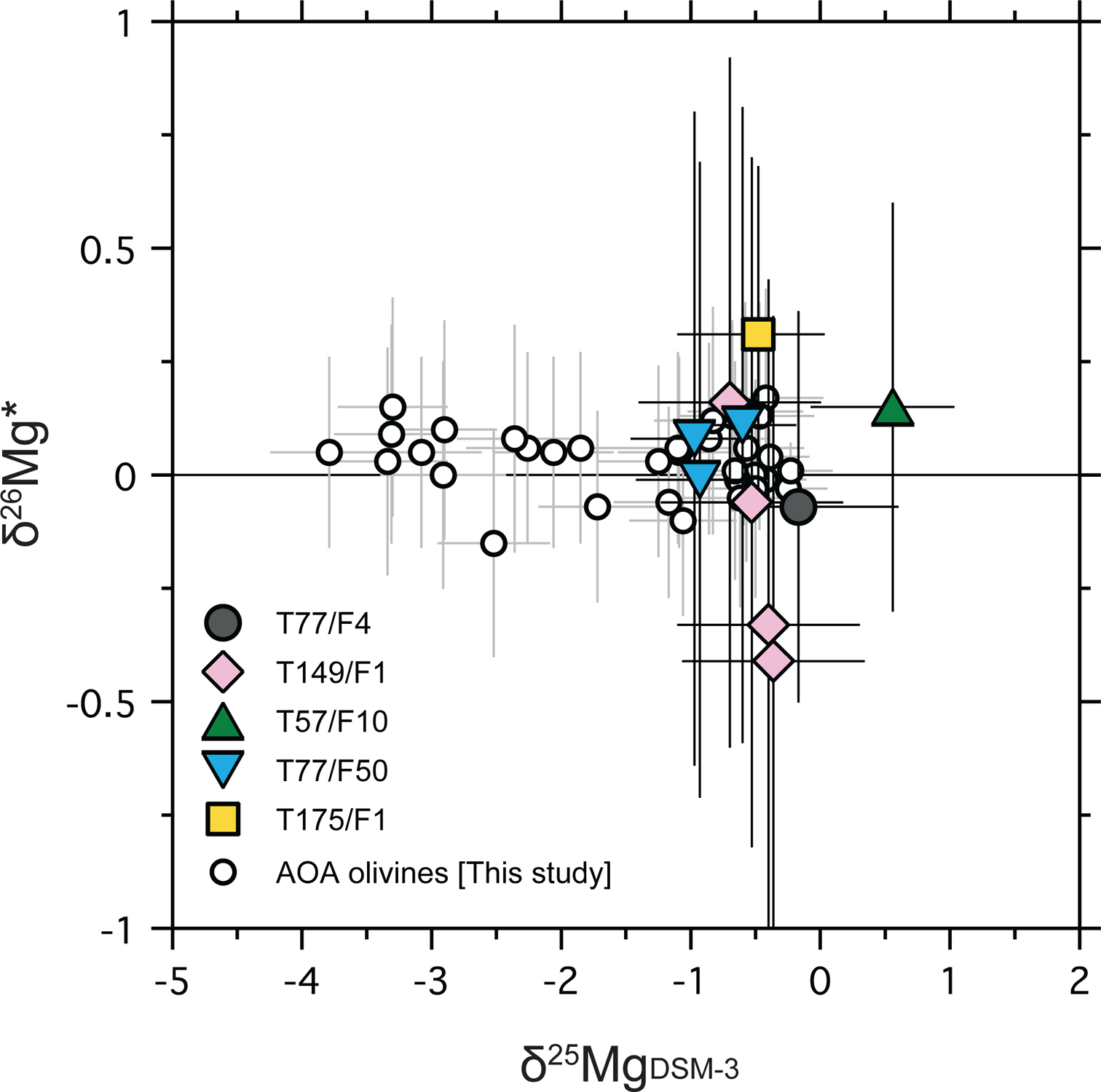

δ26Mg* values of AOA olivines and Wild 2 olivines are reported in Tables 4 and 5, and are plotted against their δ25Mg values in Fig. 10. δ26Mg* values of AOA olivines from Kaba and DOM 08006 range from −0.15 ± 0.25‰ (2σ) to 0.17 ± 0.24‰ (2σ) and do not show resolvable excesses in 26Mg when compared to inferred Solar System initial δ26Mg* values (−0.040‰; Jacobsen et al., 2008 or −0.016‰; Larsen et al., 2011). δ26Mg* values of Wild 2 olivines range from −0.41 ± 0.76‰ (2σ) to 0.31 ± 0.37‰ (2σ) and do not show resolvable excesses in 26Mg.

Fig. 10.

δ26Mg*-δ25MgDSM-3 plot for AOA olivines (Kaba and DOM 08006) and the five Wild 2 olivine particles studied.

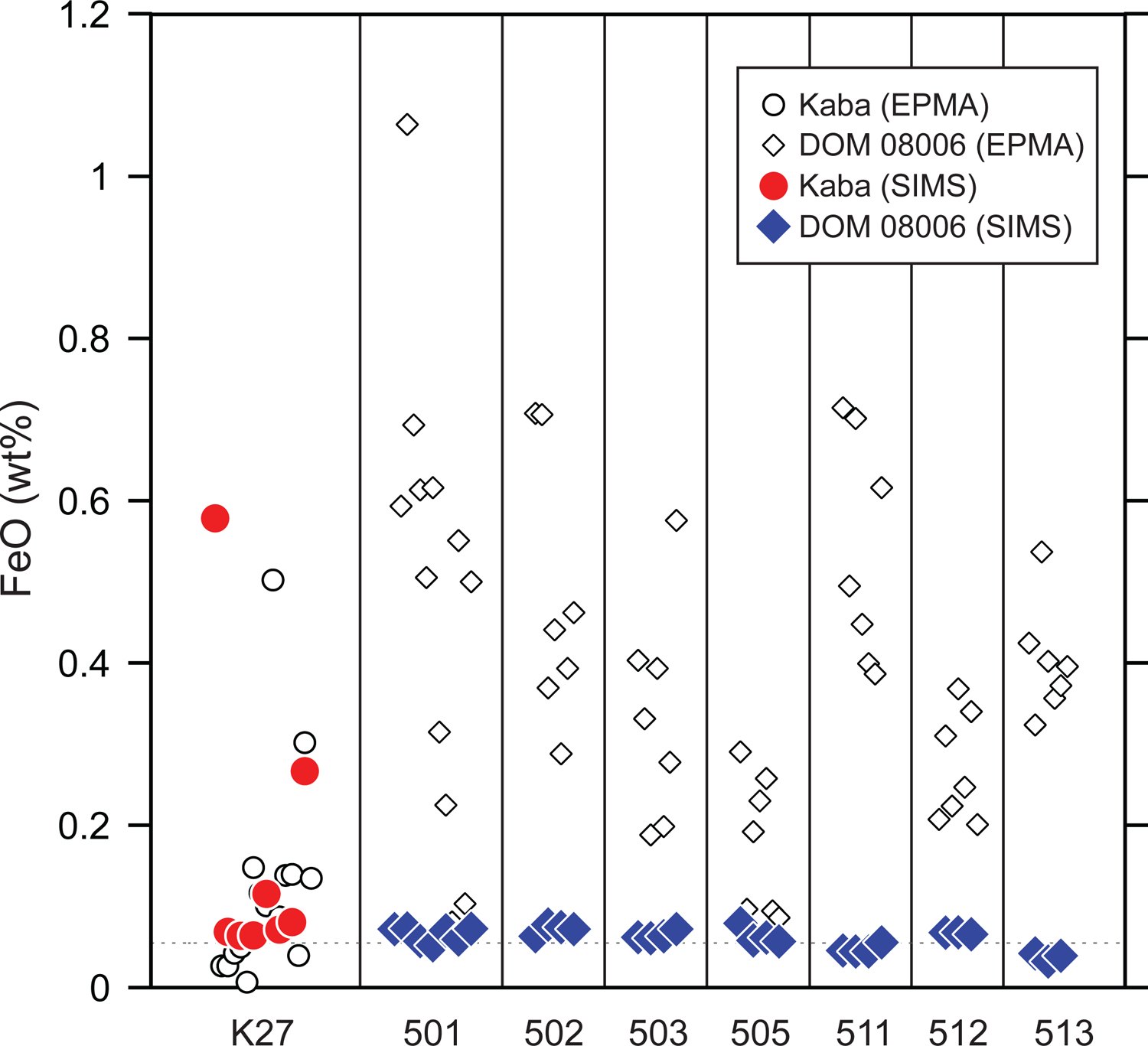

4.4. Minor element abundances of AOA and Wild 2 olivines obtained with SIMS

CaO, Cr2O3, MnO and FeO contents in AOA and Wild 2 olivines were determined with a spatial resolution of ~1.5 μm by SIMS (Tables 4 and 5). Olivines from Kaba and DOM 08006 AOAs show one or two orders of magnitude variation in CaO, Cr2O3, and MnO contents ranging from 0.03 to 0.28 wt%, 0.06 to 0.32 wt%, and 0.004 to 0.31 wt%, respectively. FeO contents in olivines from DOM 08006 AOAs do not show significant variation among the seven examples investigated (0.03–0.08 wt%; Fig. 11). In contrast, olivines from Kaba AOA K27 are more variable (0.06–0.58 wt%) than DOM 08006 AOAs (Fig. 11). MnO/FeO (wt%) ratios of 38 olivine analyses show a large variation (0.1–4.2) even within a single inclusion (e.g., 0.1–2.1 in AOA511; see Table 4).

Fig. 11.

FeO contents (wt%) of AOA olivines from Kaba and DOM 08006. Data obtained with FE-EPMA (open symbols) and SIMS (closed symbols) are shown. Data obtained with FE-EPMA might be overestimated due to secondary fluorescence effects (see section 5.3.2). The dotted line represents the detection limit (0.05 wt%) for FE-EPMA analyses.

CaO, Cr2O3, and MnO contents in five Wild 2 olivine particles (T57/F10, T77/F4, T77/F50, T149/F1, and T175/F1) range from 0.004 to 0.19 wt%, 0.07 to 0.53 wt%, and 0.06 to 0.66 wt%, respectively. The 16O-depleted, FeO-rich Wild 2 olivines (T77/F4 and T149/F1) have higher CaO contents (0.12–0.19 wt%) than the 16O-rich, FeO-poor Wild 2 olivines (0.004–0.04 wt%). The MnO/FeO (wt%) ratio of 16O-rich olivine from T77/F50 is 3.8, is consistent with LIME olivine (Klöck et al., 1989). The MnO/FeO (wt%) ratios of the other 16O-rich olivines (T57/F10 and T175/F1) are 0.38 and 0.37, respectively. 16O-depleted Wild 2 olivines T77/F4 and T149/F1 have very low MnO/FeO ratios (≤0.03) due to their abundant FeO contents.

5. DISCUSSION

5.1. Distribution of O isotopes at the AOA-forming regions

Ushikubo et al. (2017) conducted O isotope analyses of individual AOA minerals from the Acfer 094 (C-ungrouped 3.00) carbonaceous chondrite and observed subtle variations in O isotope ratios along slope ~1 lines (CCAM and PCM). Some AOA olivines studied here show similar detectable variability (Fig. 6a), indicating slight oxygen isotope variation of early solar nebular gas (Ushikubo et al., 2017). However, these variations are very small compared to the differences between O isotope ratios of AOAs and more 16O-depleted objects (e.g., chondrules). In fact, the averaged O isotope ratios of individual AOAs from Kaba and DOM 08006 cannot be distinguished from each other (Fig. 6b). Those of AOAs from Acfer 094 (Ushikubo et al., 2017) also plot within the range of Kaba and DOM 08006 AOAs (Fig. 6b). These observations indicate that AOAs from Kaba, DOM 08006, and Acfer 094 formed in a single 16O-rich gaseous reservoir (average Δ17O = −23.9 ± 0.5‰; 2SD; N = 12; Ushikubo et al., 2017 and this study), probably near the proto-Sun (Krot et al., 2004) and were transported to accretion regions of each chondrite parent body.

In addition to AOAs, O isotope ratios of fine-grained CAIs from type 3.00–3.05 chondrites as well as spinel-hibonite inclusions (SHIBs) from CM chondrites are distributed between the CCAM and PCM lines with limited variations in Δ17O from −24‰ to −22‰ (Kööp et al., 2016; Ushikubo et al., 2017). Regarding Δ17O values, CAIs from the least metamorphosed CO and CR chondrites also exhibit consistently 16O-rich isotope characteristics (Δ17O ≤ −20‰; Makide et al., 2009; Bodénan et al., 2014; Simon et al., 2019; Zhang et al., 2020). The O isotope similarity among refractory inclusions from thermally unmetamorphosed chondrites suggests that they formed in a homogeneously 16O-rich reservoir.

5.2. Distribution of Mg isotopes at the AOA- and Wild 2 olivine-forming regions

We observe large variation in Mg isotopes of AOA olivine (Fig. 7). Other types of refractory inclusions (i.e., CAIs) also exhibit isotopic variations in multiple elements, including Mg (e.g., Liu et al., 2009; Wasserburg et al., 2012; MacPherson et al., 2017; Park et al., 2017), which are sometimes attributed to nucleosynthetic anomalies. However, a nucleosynthetic origin for the negative δ25Mg and δ26Mg values observed in AOA olivine seems unlikely because these values are linearly correlated with each other (Fig. 7), with a slope of ~0.5. Instead, this correlation is most likely the result of mass-dependent isotope fractionation. Based on theoretical studies, equilibrium and kinetic mass-dependent processes have different slopes in δ26Mg′ versus δ25Mg′ space (0.521 and 0.511, respectively; Young and Galy, 2004; Davis et al., 2015). The slope of the mass-dependent fractionation observed in the AOA olivines studied here (0.516 ± 0.012, 2σ; Fig. 8) is in between these expected slopes, and therefore cannot be distinguished as being the result of an equilibrium or kinetic process.

Teng et al. (2010) conducted Mg isotope analyses of 38 chondrites which show indistinguishable ratios (δ25Mg = −0.15 ± 0.04‰, δ26Mg = −0.28 ± 0.07‰, 2SD). In this study, the Mg isotope regression for AOA olivines is δ25Mg′ = (−0.06 ± 0.04) + (0.516 ± 0.012) × δ26Mg′ (Fig. 8). If using the δ26Mg′ value of bulk chondrites (Teng et al., 2010) in this formula, the calculated δ25Mg′ is −0.20 ± 0.04‰ (95% confidence limit), which is indistinguishable from that of the bulk chondrites within their uncertainties. This suggests that AOA olivines originated from a reservoir with a chondritic Mg isotope ratio.

Five Wild 2 particles show resolvable variability in Mg isotope ratios (Fig. 9). All Wild 2 olivine analyses fall on a mass-dependent fractionation line defined by individual AOA analyses (Fig. 9), suggesting Wild 2 olivine particles also derived from a chondritic Mg isotope reservoir. While uncertainties from comet particles are relatively larger, our data demonstrate for the first time that Mg isotopes are in agreement between Wild 2 comet olivine particles and other known Solar System solids.

5.3. Origin of AOAs: Condensation and thermal processing in the solar protoplanetary disk

5.3.1. Variations in texture among AOAs

Earlier studies have hypothesized a condensation origin for AOAs based on textural and mineralogical signatures (Krot et al., 2004a and references therein). The porous and irregular shapes of some AOAs indicate that they are aggregates of olivine grains and were never completely molten (e.g., Grossman and Steele, 1976; Krot et al., 2004a and references therein). Also, the presence of silica in an AOA from the Yamato-793261 (CR) is indicative of gas-solid condensation (Komatsu et al., 2018). The AOAs studied here show textural variations (Figs. 3–5), allowing for interpreting their origins. Three of them (K27, 505 and 513) have a compact texture with little porosity in their forsterite portions (Fig. 3), similar to “compact AOAs” from Yamato-81020 (CO3.05) (Sugiura et al., 2009). In contrast, AOAs 502 and 503 are porous, irregularly shaped objects (Fig. 4), similar to “porous AOAs” reported in Sugiura et al. (2009). Compact and porous AOAs are found in other types of carbonaceous chondrites (e.g., Krot et al., 2004a; Weisberg et al., 2004; Ruzicka et al., 2012; Rubin, 2013; Krot et al., 2014; Han and Brearley, 2015; Komatsu et al., 2015), suggesting this textural variation is a general characteristic among AOAs. From our observations, we categorize the nine AOAs investigated here into two types of AOAs; (1) three AOAs, K27, 505, and 513 are categorized as compact AOAs, as they have almost no pores and show a concentric texture with spinel and/or anorthite at the core → Al-diopside → forsterite (Figs. 3c, e, g); and (2) those with pore-rich, irregular-shaped, ±fine-grained textures are categorized as pore-rich AOAs (501, 502, 503, 511, 512, 514; Figs. 4–5). Spinel grains are observed in compact AOAs, but are not present in pore-rich AOAs of this study. Conversely, diffuse Ca-Al-rich haloes are observed in pore-rich AOAs, but are not a feature of compact AOAs. Moreover, the pores within pore-rich AOAs have polygonal outlines (e.g., Figs. 4b–d and 4f–g), suggesting these AOAs avoided melting (Han and Brearley, 2015).

Many AOAs do not appear to be the result of simple condensation (e.g., Komatsu et al., 2009; 2015). As shown in Fig. 3, compact AOA olivines have low porosity textures, indicating that they experienced high-temperature annealing after their condensation and aggregation (e.g., Krot et al., 2004a; Sugiura et al., 2009; Komatsu et al., 2009; Han and Brearley, 2015). In addition, compact AOAs K27 and 513 contain 5–10 μm size anorthite that is rimmed by 5–10 μm thick Al-diopside, which is in turn rimmed by olivine grains (Figs. 3c and 3e). This texture is not consistent with a sequence that is predicted by equilibrium condensation calculations (Petaev and Wood, 2005). Komatsu et al. (2009) performed heating experiments on mineral assemblages similar to those of AOAs and suggested that Al-diopside in AOAs can be produced from a small degree of melting of forsterite and anorthite. Based on the compact texture and the occurrence of Al-diopside between forsterite and anorthite (Figs. 3c and 3e), it appears that some AOAs experienced high-temperature annealing.

Similar occurrences of Al-diopside between forsterite and anorthite are also found among pore-rich AOAs (e.g., Figs. 5b–c), but at much finer scales. In addition, minor low-Ca pyroxenes are found in two pore-rich AOAs (502 and 503), which occur with Fe,Ni-metal (Figs. 4b, 4d, 4g). Similar textural occurrences of low-Ca pyroxene are present in AOAs from CR chondrites (Krot et al., 2004b). The existence of low-Ca pyroxene suggests interaction with gaseous SiO or direct condensation (Krot et al., 2004b). These observations indicate that some pore-rich AOAs have also experienced high-temperature annealing, although to a smaller degree relative to compact AOAs.

5.3.2. Variations in minor element abundances among AOAs

Among the AOAs investigated there is an inconsistency in FeO contents determined by EPMA versus SIMS (Fig. 11). Previous studies employing EPMA found that AOA olivines from the least metamorphosed chondrites have detectable FeO (~1 wt%; e.g., Krot et al., 2004a; Weisberg et al., 2004; Itoh et al., 2007; Sugiura et al., 2009; Komatsu et al., 2015; 2018), most of which are more enriched than concentrations predicted by equilibrium condensation calculations (e.g., ~0.14 wt% at a total pressure of 10−4 bar and with a dust enrichment factor of 1 (nominal solar composition); Sugiura et al., 2009). The enrichment in FeO suggests condensation of olivine at more oxidizing conditions (= high dust/gas ratios) (e.g., Komatsu et al., 2015; 2018). Our FE-EPMA-derived FeO contents from AOA olivines are variable (~0.05–1 wt%; open symbols in Fig. 11), with some values that are also much higher than that predicted by Sugiura et al. (2009). In contrast, our SIMS data reveal uniform olivine FeO contents of ~0.05 wt% among the AOAs studied (with a few exceptions for Kaba AOA K27; Fig. 11), which is consistent with equilibrium condensation calculations with a nominal solar composition gas from Sugiura et al. (2009). The uniform olivine FeO contents suggest that AOA olivine formed at more reducing conditions than previously thought. As higher FeO is mostly observed in porous AOAs, Sugiura et al. (2009) pointed out the possibility of contributions from FeO-bearing matrix materials during olivine EPMA analyses. Our present results also indicate that FeO contents of AOA olivine determined by EPMA analyses tend to be influenced by fluorescence from surrounding matrix materials and/or Fe,Ni-metals in AOAs, and that this may result in an overestimation of FeO contents and in an underestimation of MnO/FeO ratios in AOA olivine. The similar problem on EPMA analyses has also been pointed out by Wasson et al. (1994), who demonstrated that FeO contents in enstatite grains separated from EL6 meteorite chips are an order of magnitude lower than those in meteorite thin sections, suggesting a secondary fluorescence and/or double backscattering of electrons from surrounding opaque minerals. Therefore, we only refer to minor element abundances, including FeO contents, obtained by SIMS in the following discussion.

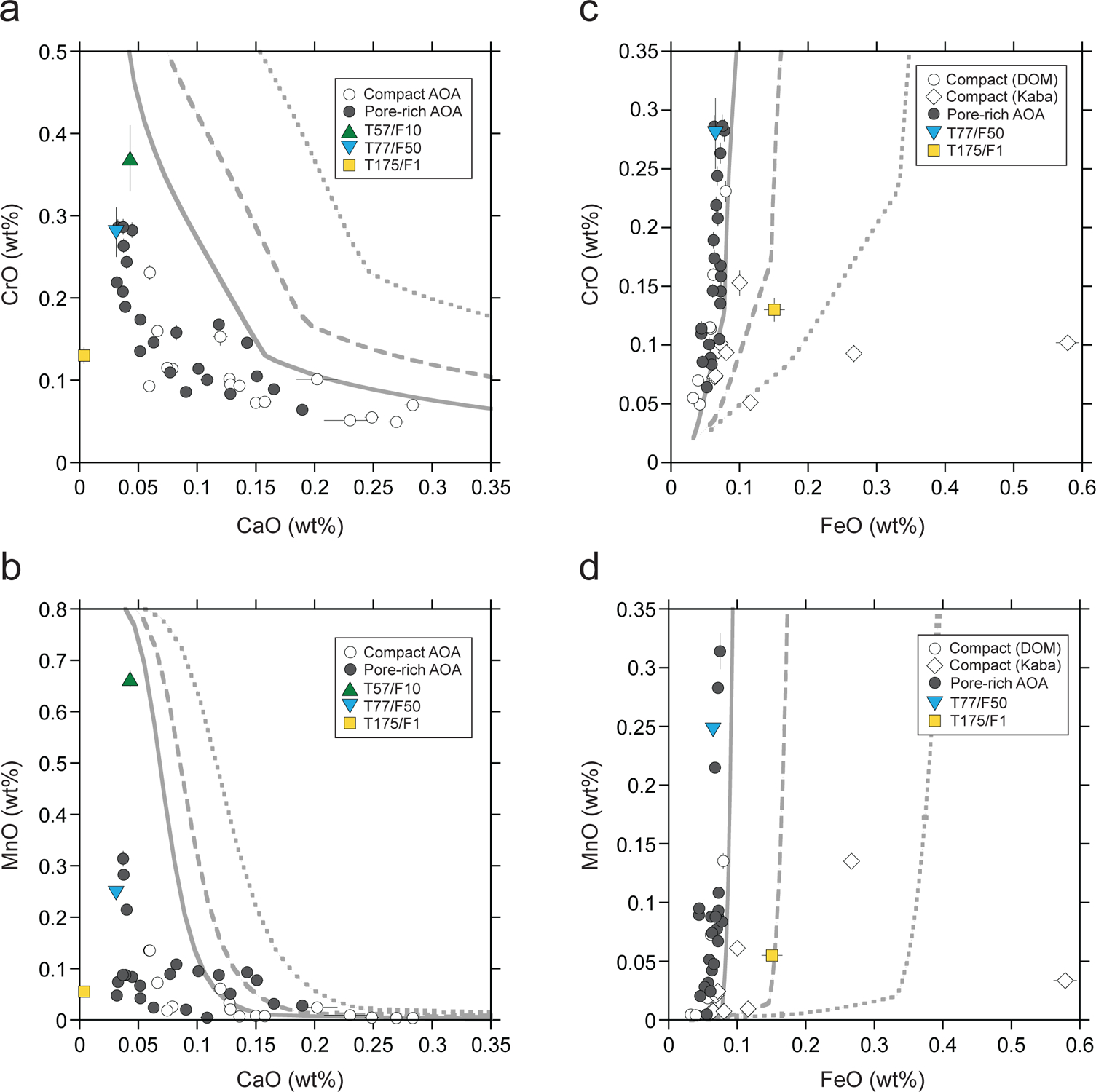

In Figure 12 CrO and MnO contents from SIMS olivine analyses are plotted as functions of CaO (Figs. 12a–b) and FeO (Figs. 12c–d), along with predicted values from Sugiura et al. (2009). Here we use CrO contents instead of Cr2O3 to compare SIMS data and predicted values from Sugiura et al. (2009). Generally, CrO (and possibly MnO) contents of AOA olivine are anti-correlated with CaO contents (Figs. 12a–b). Some olivines in pore-rich AOAs are enriched in Cr and Mn and are depleted in Ca relative to those in compact AOAs, but ~70% plot within a narrow range (CaO ~0.05–0.2 wt%; Figs. 12a–b). The correlations between textures and volatility controlled elemental abundances of AOAs are consistent with observations from Sugiura et al. (2009) and Komatsu et al. (2015), and indicate that compact AOAs are more refractory than pore-rich AOAs. As shown in Figs. 12c–d, plots of MnO and CrO versus FeO contents in AOA olivine are similar to those predicted by condensation models with a dust enrichment factor of 1 (nominal solar composition), except for some Kaba K27 AOA data. While all DOM 08006 data show a limited range in FeO contents regardless of their textural variations (compact versus pore-rich), it is possible that some Kaba AOA olivines were influenced by parent body alteration, leading to subtle Fe addition. Using data from DOM 08006 alone, we find CrO, MnO, and FeO compositions of AOA olivine are slightly offset, but broadly consistent with the condensation paths calculated by Sugiura et al. (2009) (Figs. 12c–d). In contrast, when CrO and MnO are plotted against CaO (Figs. 12a–b), they are clearly offset from the condensation paths, which is similar to AOA data reported in Sugiura et al. (2009). These relationships could be the result of two possibilities: (1) equilibrium condensation with lower dust/gas ratios (dust enrichment factor < 1), or (2) disequilibrium condensation of AOA olivine. In the case of (1), the condensation paths in Figs. 12c–d could be shifted to a lower side with respect to FeO contents (X-axis) because disk environments with very low dust/gas ratios could have resulted in lower FeO contents of condensed olivine without significant changes in MnO and CrO contents (Sugiura et al., 2009; Komatsu et al., 2015). However, even in environments with lower dust/gas ratios, CaO contents in AOA olivine may not be significantly reduced when compared to those predicted from condensation calculations (Figs. 12a–b). In the case of (2), disequilibrium condensation could explain low concentrations of CaO relative to those predicted from a model condensation path. In the temperature range of equilibrium olivine condensation (e.g., 1300–1370 K at 10−4 bar with a dust enrichment factor of 1), most Ca is predicted to be consumed by the formation of Ca-Al-rich minerals that do not remain in the gas phase (Sugiura et al., 2009). Thus, if AOA olivine condensed from the gas phase and was never equilibrated with pre-existing Ca-Al-rich minerals, CaO contents in olivine would be lower than those expected by equilibrium condensation. In contrast, Mn and Cr would have been largely in the gas phase, such that MnO and CrO abundances versus CaO contents in AOA olivine would plot parallel to the equilibrium condensation trajectories (Figs. 12a–d). Therefore, the observed offsets from condensation paths indicate that AOAs formed by disequilibrium condensation.

Fig. 12.

Minor element systematics of 16O-rich Wild 2 olivine particles (T57/F10, T77/F50, and T175/F1) and AOA olivines from Kaba and DOM 08006 obtained by SIMS. (a and c) CrO contents as functions of (a) CaO and (c) FeO. (b and d) MnO contents as functions of (b) CaO and (d) FeO. Equilibrium condensation trajectories at 10−4 bar with dust enrichment factor = 1 (nominal solar composition shown by solid curve), 2 (dashed curve), and 5 (dotted curve) calculated by Sugiura et al. (2009) are shown for comparison. Data for T57/F10 are not shown in (c) and (d) because of its high FeO content (1.75 wt%).

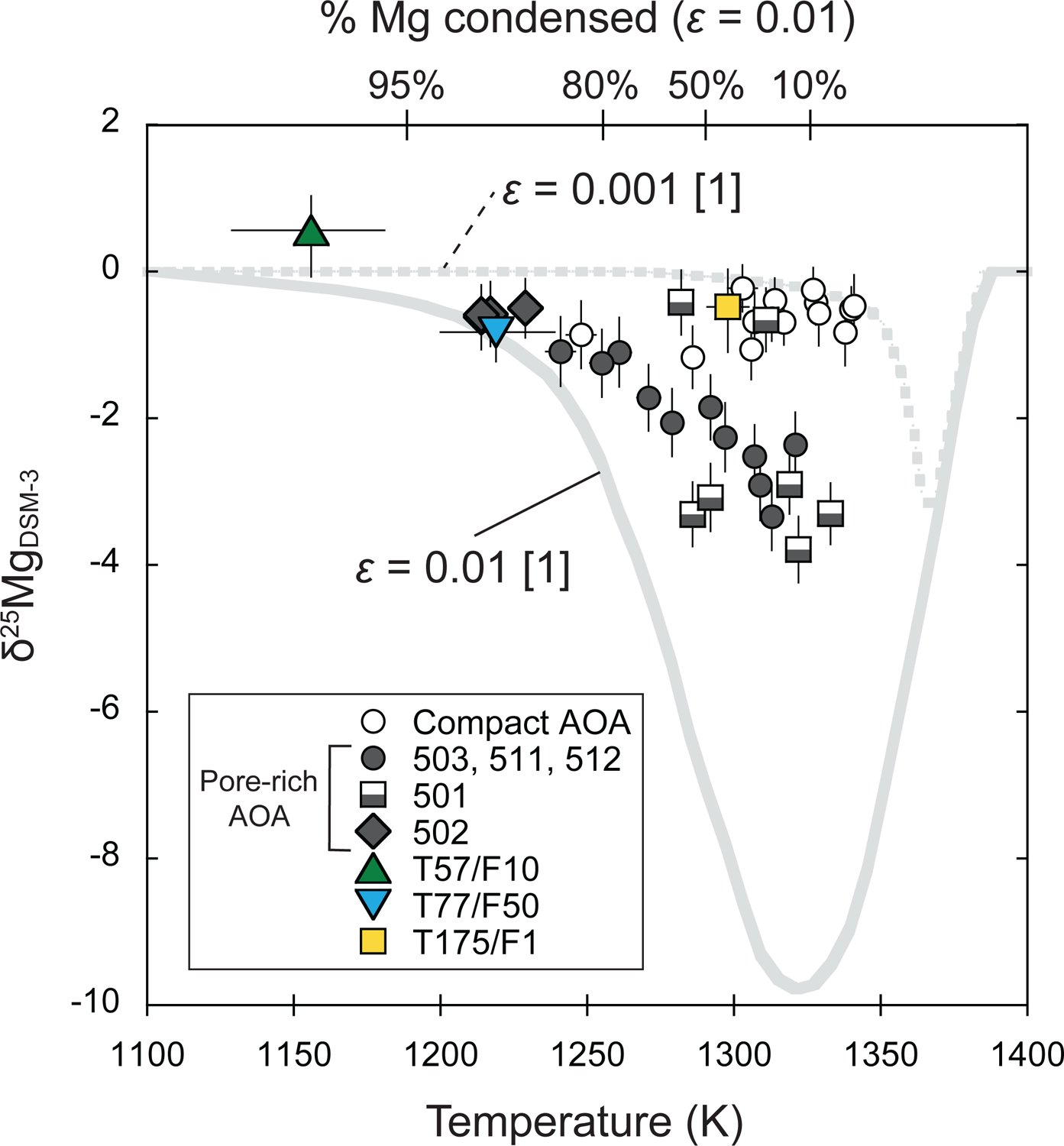

5.3.3. Kinetic isotope fractionation during condensation

During condensation, mineral phases can become enriched in light isotopes due to disequilibrium effects. For example, Richter (2004) modeled Mg isotope fractionation during condensation and demonstrated that Mg isotopes of the condensate are enriched in lighter isotopes when the ambient temperature changes faster than the condensation timescale. In this condition, the pressure of Mg gas is greater than its saturation vapor pressure, which facilitates disequilibrium condensation. This supersaturated condition could produce condensates enriched in lighter isotopes.

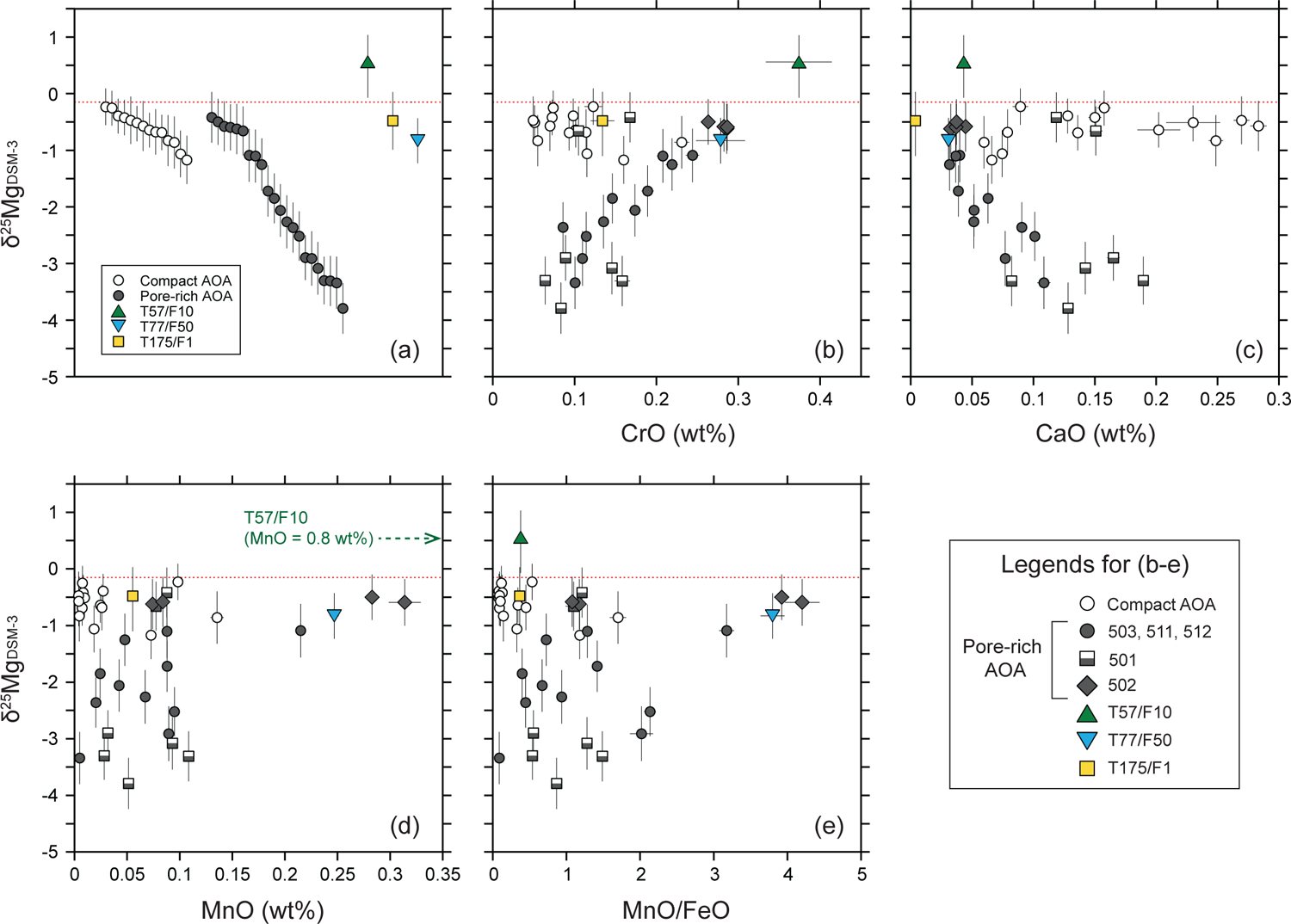

Fig. 13a shows δ25Mg values for individual olivines from AOAs with different textures (compact versus pore-rich). Compact AOAs are more limited in δ25Mg values (−1.2‰ to chondritic), while pore-rich AOAs exhibit greater variability (−3.8‰ to chondritic). As pore-rich AOAs may have experienced limited post-formation annealing, their larger and more negative δ25Mg variations may have been caused by disequilibrium condensation processing. As discussed earlier, variations of trace element abundances in AOA olivine suggest they are controlled by volatility even though concentrations do not exactly follow equilibrium condensation trajectories. The δ25Mg values in pore-rich AOA olivine correlate positively with CrO and negatively with CaO contents, respectively (Figs. 13b and c), which could represent a condensation trajectory in a cooling nebula gas.

Fig. 13.

Relationships among Mg isotope ratios and minor element abundances of 16O-rich Wild 2 olivine particles T57/F10, T77/F50, and T175/F1, and AOA olivines from Kaba and DOM 08006 obtained by SIMS. Open circle symbols represent AOA olivines with compact textures (compact AOA), while closed circle, diamond, and half-closed square symbols represent AOA olivines with pore-rich textures (pore-rich AOA; see section 5.3.1 for details). The dotted lines represent the Mg isotope ratio of bulk chondrites (Teng et al., 2010). (a) δ25MgDSM-3 values of three 16O-rich Wild 2 particles and AOA olivines with different textures (compact versus pore-rich). (b-e) δ25MgDSM-3 values as functions of (b) CrO, (c) CaO, (d) MnO contents (wt%) and (e) MnO/FeO (wt%) ratio. Errors are 2σ.

A similar positive correlation between δ25Mg and MnO concentration is expected, but is not clearly seen in Fig. 13d. Most AOAs have MnO contents < 0.1wt% and a large range of δ25Mg. Equilibrium condensation calculations by Sugiura et al. (2009) predict that condensation of Mn into olivine should occur at a lower temperature than Cr, and that the increase of MnO with decreasing temperature is steeper than that of CrO (see Fig. 2 in Sugiura et al., 2009). If the cooling rate is faster than the equilibrium condensation timescale (i.e., disequilibrium condensation), and if the temperature is within the range of Mn condensation, Mn will not sufficiently condense into olivine. Thus, relatively lower MnO contents are consistent with kinetic mass-dependent isotope fractionation of Mg, due to supersaturated conditions during condensation of olivine.