Abstract

Senescence is a cellular state in which cells undergo persistent cell cycle arrest in response to nonlethal stress. In the treatment of cancer, senescence induction is a potent method of suppressing tumour cell proliferation. In spite of this, senescent cancer cells and adjacent nontransformed cells of the tumour microenvironment can remain metabolically active, resulting in paradoxical secretion of pro‐inflammatory factors, collectively termed the senescence‐associated secretory phenotype (SASP). The SASP plays a critical role in tumorigenesis, affecting numerous processes including invasion, metastasis, epithelial‐to‐mesenchymal transition (EMT) induction, therapy resistance and immunosuppression. With increasing evidence, it is becoming clear that cell type, tissue of origin and the primary cellular stressor are key determinants in how the SASP will influence tumour development and progression, including whether it will be pro‐ or antitumorigenic. In this review, we will focus on recent evidence regarding therapy‐induced senescence (TIS) from anticancer agents, including chemotherapy, radiation, immunotherapy, and targeted therapies, and how each therapy can trigger the SASP, which in turn influences treatment efficacy. We will also discuss novel pharmacological manipulation of senescent cancer cells and the SASP, which offers an exciting and contemporary approach to cancer therapeutics. With future research, these adjuvant options may help to mitigate many of the negative side effects and protumorigenic roles that are currently associated with TIS in cancer.

Keywords: cancer, cellular senescence, senescence‐associated secretory phenotype, therapy‐induced senescence

In response to therapy or other stimuli, cancer cells can undergo cellular senescence, a stress response leading to cell cycle arrest. An unintended consequence of cellular senescence is a perturbed, pro‐inflammatory cancer cell secretome, the senescence‐associated secretory phenotype (SASP). Here, we explore the role of SASP in promoting tumorigenesis and treatment resistance, with particular focus on mechanisms of therapy‐induced senescence (TIS).

Abbreviations

- ADAM17

ADAM (a disintegrin and metalloproteinase) metallopeptidase domain 17

- ALCAM

activated leukocyte cell adhesion molecule

- ALK

anaplastic lymphoma kinase

- AMPK

5' AMP‐activated protein kinase

- ATM

ataxia telangiectasia mutated

- BCL‐2

B‐cell lymphoma 2

- BETi

bromodomain and extraterminal protein inhibitors

- BH3

Bcl‐2 homology 3

- BMI1

B lymphoma Mo‐MLV insertion region 1 homolog

- BRAF

v‐raf murine sarcoma viral oncogene homolog B1

- CAF‐T

chimeric antigen receptor T cells

- CDC7

cell division cycle kinase 7

- CDKs

cyclin‐dependent kinases

- C‐EBP

CCAAT/enhancer‐binding protein

- CHK2

checkpoint kinase 2

- CSCs

cancer stem cells

- DCA

deoxycholic acid

- DCs

dendritic cells

- DDR

DNA damage response

- DIPG

diffuse intrinsic pontine glioma

- DNA

deoxyribonucleic acid

- DOX

doxorubicin

- EGF/R

epidermal growth factor/receptor

- EMT

epithelial‐to‐mesenchymal transition

- EOC

epithelial ovarian cancer

- EV

extracellular vesicles

- FBP1

fructose‐1,6‐bisphosphatase

- FGF/R

fibroblast growth factor/receptor

- GCV

ganciclovir

- GM‐CSF

granulocyte‐macrophage colony‐stimulating factor

- H3K27M

substitution mutation of lysine for methionine at position 27 in histone H3

- HCC

hepatocellular carcinoma

- HGF

hepatocyte growth factor

- HGSC

high‐grade serous carcinoma

- HNSCC

head and neck squamous cell carcinoma

- HSCs

hepatic stellate cells

- ILs

interleukins

- IRE1

inositol‐requiring enzyme 1

- JAK‐STAT

Janus kinase/signal transducer and activator of transcription

- M‐CSF

macrophage colony‐stimulating factor

- MMP

matrix metalloproteinase

- mTOR

mammalian target of rapamycin

- NAMPT

nicotinamide phosphoribosyltransferase

- NASP

NFκB‐driven SASP

- NFκB

nuclear factor kappa‐light‐chain‐enhancer of activated B cells

- NK

natural killer (cells)

- p38 MAPK

p38 mitogen‐activated protein kinase

- PARP

poly(ADP‐ribose) polymerase

- PASP

p53‐driven SASP

- PD‐1

programmed cell death protein 1

- PDGFa/b

platelet‐derived growth factor subunit A/B

- PTBP1

polypyrimidine tract‐binding protein 1

- Pten

phosphatase and tensin homolog

- PyMT

polyomavirus middle T antigen

- QoL

quality of life

- Rb

retinoblastoma

- RNA

ribonucleic acid

- ROCK

Rho‐associated coiled‐coil containing kinases

- ROS

reactive oxygen species

- SASP

senescence‐associated secretory phenotype

- scRNASeq

single‐cell RNA sequencing

- siRNA

short interfering RNA

- TGFB

transforming growth factor beta

- TIMP1

tissue inhibitor of metalloproteinase 1

- TIS

therapy‐induced senescence

- TME

tumour microenvironment

- TNBC

triple‐negative breast cancer

- TOP1

topoisomerase I

- TOP1cc

TOP1‐DNA cleavage complexes

- uPAR

urokinase‐type plasminogen activator receptor

- VEGF/R

vascular growth factor/receptor

1. Introduction

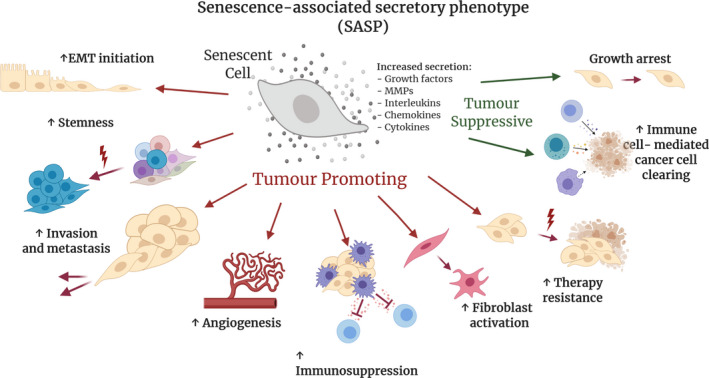

Cellular senescence is an important mechanism that has evolved to protect tissues from dangerous overproliferation of cells and therefore plays a tumour‐suppressive role [1]. In malignancy, cancer cells begin to proliferate uncontrollably, and somatic mutations are acquired at a greater frequency than in normal tissue [2]. Therefore, in many circumstances, cellular senescence is a protective process that safeguards the tissue from the development of cancer by permanently halting the cell cycle, inhibiting proliferation and preventing the propagation of deleterious genetic mutations. For this reason, anticancer therapies often aim to impede cancer progression by inducing cell cycle arrest [3]. Despite this concept being initially advantageous in reducing tumour burden, a key setback in overall patient outcome is the eventual therapy resistance and/or relapse that many patients endure. Although targeted cancer cells have stopped proliferating, senescent cells remain metabolically active and can have the unintended side effect of developing an altered cellular secretome, which is associated with local inflammation, extracellular changes and increased growth factor activity [4]. These secretions, collectively known as the senescence‐associated secretory phenotype (SASP), are a dynamic, cell type‐dependent phenomenon where senescent cells secrete high levels of cytokines, chemokines, proteases, growth factors and extracellular vesicles (EVs), all of which are typically pro‐inflammatory. This response is due to a persistent cellular stressor that can elicit a DNA damage response (DDR), which can be induced in both cancer cells and nontransformed cells of the tumour microenvironment (TME) [5] and can be both pro‐ or antitumorigenic. For example, the SASP can promote epithelial–mesenchymal transition (EMT) initiation [6, 7], stemness induction [8, 9], local tissue invasion [10], angiogenesis [11], activation of fibroblasts [12], immunosuppression [13, 14], enhanced metastasis [15] and therapy resistance [16, 17, 18, 19] (Fig. 1, see red arrows). Conversely, the SASP has also been shown to aid chemotherapy delivery [20] as well as enhance clearing of senescent cancer cells via recruitment of immune cells such as natural killer (NK) cells, macrophages and cytotoxic T cells [13, 21, 22, 23, 24], therefore impeding tumour progression (Fig. 1, see green arrows).

Fig. 1.

Senescence‐associated secretory phenotype (SASP) exhibits both tumour‐promoting and tumour‐suppressing roles. Senescent cells secrete a number of factors. including growth factors, MMPs, interleukins, chemokines and cytokines, which can play many complex roles in the tumour microenvironment (TME). The red arrows highlight tumour‐promoting roles, including increases in epithelial‐to‐mesenchymal (EMT) initiation, cancer cell stemness, invasion and metastasis, angiogenesis, immunosuppression, fibroblast activation and therapy resistance. The green arrows highlight tumour‐suppressive roles of SASP, including cell cycle arrest and an increase in immune surveillance resulting in improved cancer cell clearing by the immune system.

Due to cancer therapeutics generally being administered systemically, a problem arises when surrounding nontransformed cells become senesced as a response to the cytotoxic agent. As a result, an accumulation of senescent cells can cause the onset of secondary disease such as fibrosis‐driven disorders, cardiothoracic diseases and neurodegenerative disease [25]. The SASP can be further reinforced via autocrine signalling [26, 27], while also spreading to adjacent cells and tissues in a long‐range paracrine manner [28], including via EVs [29]. Recently, there have been attempts to eliminate SASP‐expressing cells to enhance anticancer therapies by using senescence‐targeting drugs (known as ‘senolytics’ or ‘senostatics’), which hold some promise for overcoming this diverse and complex resistance mechanism. Here, we will describe the latest discoveries in the context of therapy‐induced senescence (TIS) and the SASP, and its dynamic role in both promoting and mitigating tumour development and progression.

2. Diversity of SASP induction

Senescence can occur from several sources of cellular stressors, including genomic or telomeric injury, epigenomic disturbances, oxidative stress and changes to oncogene or tumour suppressor expression [30]. These processes can activate the tumour suppressor pathways p53 and retinoblastoma (Rb), which can then cause increased p16INK4A expression, triggering cell cycle arrest [31]. Several downstream pathways involved in DNA damage, cell cycle arrest and inflammation can then become activated, inducing the SASP in these cells. These pathways include ATM [32], CHK2 [33], p38 MAPK [34, 35], CCAAT/enhancer‐binding proteins (C/EBP) [27], NFκB [21], mTOR [36] and JAK‐STAT signalling [37], which have been summarised extensively by Faget, Ren [31]. However, senescence can also be triggered by direct overexpression of p16INK4A, which does not produce an inflammatory SASP (normally mediated by NFκB), for reasons that are still being elucidated [38, 39, 40]. Due to the diverse nature of secreted factors and involvement of several prominent transcriptional pathways, biomarkers for SASP‐expressing cells have been difficult to identify [41]. Despite this, a recent study was able to identify 55 genes aligned with a common ‘senescence‐associated’ signature, albeit with high levels of transcriptional heterogeneity between senescent cell types [41]. In general, the SASP is considered highly cell type‐dependent and diverse in secreted factors; however, there are several SASP markers that are shared by most SASP‐expressing cells. These markers include (but are not limited to) growth factors (vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF), platelet‐derived growth factor (PDGF), hepatocyte growth factor (HGF)), interleukins (IL‐1α, IL‐6, IL‐8, IL‐10, IL‐13, IL‐15), matrix metalloproteinases (MMP3, MMP9) and cytokines/chemokines (CXCL1, CXCL2, CXCL5, CXCL11, CXCL12, CCL2, CCL20); however, it is important to note that none of these markers are truly specific to the phenotype alone [31]. That is, these cellular secretions often overlap with common markers of cell type or cellular activation, as well as inflammation and proliferation [31]. Efforts are now being made to further profile the SASP of different cells by characterising the specific factors being secreted in order to develop better biomarkers. For example, Basisty et al. (2020) have recently developed the ‘SASP Atlas’, which is the first proteomic‐based database for soluble SASP‐related factors and SASP factors contained in exosomal cargo [42]. This resource offers insight into the diversity of the SASP secreted factors, which is dependent on both stressor that induces the SASP and also cell type [42]. Therefore, it is important to consider that the specific features of the SASP are determined not only by the senescent cell type and tissue, but also by what caused senescence to occur.

Interestingly, recent work has highlighted that alterations in cellular metabolism may play a central role in SASP activation, thereby promoting cancer development and progression. For example, Yoshimoto and colleagues (2013) showed that obesity can induce the SASP in hepatic stellate cells (HSCs) via increased levels of deoxycholic acid (DCA), a metabolite that can cause DNA damage [43]. These SASP‐expressing HSCs then produced increased levels of inflammatory cytokines, enhancing the development of carcinogen‐stimulated hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) in mice [43]. More recently, Li et al. (2020) reported that hepatocyte‐specific deletion of fructose‐bisphosphatase 1 (FBP1), a rate‐limiting enzyme in the process of gluconeogenesis, results in a fatty liver as well as activation of HSCs, which exhibit the SASP [44]. When treated with drugs that can kill senescent cells, such as dasatinib or ABT‐263, this effect was reversed, highlighting FBP1 as a potential novel liver cancer tumour suppressor [44]. Similarly, a preclinical study by Dorr et al. (2013) reported that senescent lymphomas were shown to utilise glucose at a much higher rate due to the presence of the SASP [45]. In this study, the senescent cells relied heavily on glucose utilisation as a response to cope with the macromolecular stress induced by the SASP [45]. When glucose utilisation was inhibited, tumours regressed more successfully following chemotherapy treatment [45]. Moreover, it has been shown that a high level of nicotinamide phosphoribosyltransferase (NAMPT), a rate‐limiting enzyme in the NAD+ pathway, can determine the strength of the pro‐inflammatory SASP [46]. This study by Nacarelli et al. (2019) showed that a high NAD+/NADH ratio could regulate AMPK signalling and downstream NFκB signalling [46]. This, in turn, could increase the strength of the pro‐inflammatory SASP, thereby enhancing mitochondrial respiration and glycolytic processes [46]. Considering that NAMPT inhibitors are currently in clinical trials (reviewed in [47, 48]), this study offers further insight into how the molecular mechanisms of the SASP can be clinically targeted in the context of dysregulated cellular metabolism. Interestingly, there is also evidence that cancer cells have the ability to utilise unusual nutrient sources when in a senescent state. For example, Tonnessen‐Murray et al. (2019) reported that breast cancer cells rendered senescent with doxorubicin (Dox) treatment can completely engulf neighbouring cells via a phagocytosis‐like phenomenon to aid their survival [49]. This study highlights the resourcefulness of senesced cells, where they can exploit surrounding cells as a source of nutrients to survive during dormancy, allowing them to potentially relapse at a later stage.

Overall, mainstream cancer treatment modalities such as chemotherapy, radiation, immunotherapy, and targeted therapies aim to kill cancer cells; however, sometimes only senescence is achieved. Activating cellular senescence has been shown to significantly modulate the cancer secretome via activation of a therapy‐induced SASP, which is discussed in detail below.

2.1. Chemotherapy and radiation induce the SASP

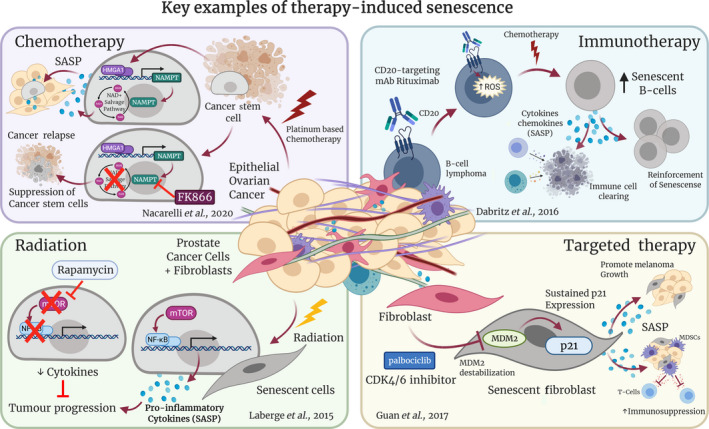

Chemotherapy and radiation are common systemic modalities for the treatment of cancer and therefore can trigger the SASP in both cancer cells and surrounding TME cells [4]. Both treatments aim to cause catastrophic DNA damage, leading to a DDR, which can cause subsequent senescence and associated SASP. Logue et al. (2018), for example, reported that paclitaxel, a common chemotherapy for the treatment of triple‐negative breast cancer (TNBC), causes aberrant regulation of ER stress via enhanced inositol‐requiring enzyme 1 alpha (IRE1) RNAse activity [50]. This increase in IRE1 activity results in an increase in SASP‐associated factors such as IL‐6, IL‐8, CXCL1, granulocyte‐macrophage colony‐stimulating factor (GM‐CSF) and TGFβ2 [50]. When IRE1 RNAse activity was normalised, paclitaxel efficacy was enhanced in preclinical TNBC models, highlighting how the chemotherapy‐induced cancer cell secretome can drive tumour development and progression [50]. Furthermore, chemotherapy‐induced senescence and the resulting SASP can drive the expansion of cancer stem cells (CSCs) from dormant senescent cells, which are critical for cancer relapse. For example, Wang et al. (2019) showed that IL‐6 secretion induced by platinum treatment causes enrichment of CSCs in the residual tumours of high‐grade serous carcinoma (HGSC) [51]. This phenomenon was also shown by Nacarelli et al. (2020) [9], building on their previous study [46], which highlighted NAMPT as a key regulator of the SASP. In epithelial ovarian cancer (EOC), Nacarelli and colleagues showed that platinum‐induced senescence‐associated CSCs could be suppressed by treatment with the NAMPT inhibitor FK866 [9] (Fig. 2, see purple box). A combination of FK866 and cisplatin inhibited the outgrowth and eventual relapse of EOC, improving overall survival in these mice. Similarly, Shen et al. (2019) reported that breast cancer cells treated with docetaxel or Dox produce abundant EVs containing miRNAs that stimulate CSC expansion via targeting of ONECUT2, a master regulator of cell fate [52].

Fig. 2.

Key examples of therapy‐induced SASP. Many cancer therapy modalities induce senescence and associated SASP, and these can influence treatment efficacy in various ways. Chemotherapy (purple box): Nacarelli et al. (2020) showed that platinum‐based chemotherapy induces cellular senescence, which can promote the formation of cancer stem cells, eventually promoting tumour relapse [9]. Treatment with the NAMPT inhibitor FK866 suppressed these cancer stem cells, preventing outgrowth of cisplatin‐treated epithelial ovarian cancer cells. Radiation (green box): Laberge et al. (2015) showed that rapamycin (an mTOR inhibitor) prevented NFκB‐driven pro‐inflammatory SASP that is induced by radiation treatment of prostate cancer cells and fibroblasts, therefore inhibiting tumour progression [36]. Immunotherapy (blue box): Däbritz et al. (2016) used a CD20‐targeting monoclonal antibody to sensitise B‐cell lymphoma cells to senescence induction alongside chemotherapy [60]. This resulted in reinforcement of senescence and enhancement of immune cell action [60]. Targeted therapy (yellow box): Guan et al. (2017) showed that prolonged exposure to palbociclib, a CDK4/6 inhibitor (CDK4/6i), could induce senescence in normal fibroblasts in a DNA damage‐independent mechanism [53]. These fibroblasts exhibited MDM2 destabilisation and sustained p21Cip1/Waf1 expression, which resulted in the promotion of melanoma growth and enhanced immunosuppression [53].

Incidental senescence due to systemic treatments can foster a SASP‐rich TME, which can not only potentiate tumorigenesis [5, 27, 53], but can also generate a multitude of side effects in normal tissues. These alterations in adjacent nontransformed tissue can cause reduced therapeutic efficacy in the short term [16, 54, 55], while also impacting quality‐of‐life (QoL) parameters in the long term [56]. For example, development of chronic inflammation via signalling molecules such as IL‐1A, IL‐6, IL‐8, CCL2 and CXCL is common in cancer patients, and consequences of systemic chemotherapy delivery are similar to those seen in ageing populations, such as frailty and insulin resistance [25]. As many of these cytokines also closely overlap with the SASP, it is possible that TIS is partly responsible for these adverse QoL side effects. Supporting this, Demaria et al. (2017) showed that treatment with a range of chemotherapy drugs, such as paclitaxel, Dox, temozolomide and cisplatin, induced a SASP in stromal host cells [18]. In this study, the authors utilised a transgenic mouse model (p16‐3MR) where host senescent cells can be tracked using a reporter gene under control of the senescence‐sensitive p16INK4a promoter and additionally can also be eliminated by administering ganciclovir (GCV) [18]. They showed that chemotherapy‐induced senescence can promote cardiac dysfunction, bone marrow suppression, inflammation, frailty and fatigue, mirroring common side effects observed in human cancer patients when administered chemotherapy [18]. When these mice were orthotopically implanted with PyMT (polyoma middle tumour‐antigen) breast cancer cells and treated with Dox, those receiving the GCV dose to eliminate host senescent cells had significantly increased survival and decreased lung and liver metastases compared to Dox‐only controls, indicating that senescent host cells were pivotal to these protumorigenic processes [18]. Furthermore, Baar et al. (2017) showed that therapeutically targeting senescent cells in preclinical mouse models of Dox‐induced senescence can have the off‐target effect of improving liver function [57].

Strikingly, even after transcription and protein synthesis, anticancer treatments can influence SASP factor functionality. For example, the manipulation of the glycosylation state of secreted proteins has also been implicated in the chemotherapy‐induced secretome. In gastric cancer, Wu et al. (2016) identified that Dox‐ and vincristine‐resistant cancer cells secreted proteins which were uniquely glycosylated compared to parental lines using a glycosite enrichment mass spectrometry protocol [58]. These alterations in post‐translational modification add another layer of complexity to the characterisation of the chemotherapy‐induced secretome and could be used to better predict drug resistance in patients [58]. Other studies have also shown that reduction of senescent cells can potentially induce normalising effects on adjacent tissues and organs [57].

Although radiation therapy is generally a more targeted approach, it can still induce senescence in local adjacent cells, in addition to tumour cells. For example, Laberge et al. (2015) showed that multiple prostate and breast cancer lines, as well as fibroblasts, exhibit SASP after treatment with radiation [36] (Fig. 2, see green box). In this study, the authors showed that this was mTOR‐dependent, as treatment with rapamycin (an mTOR inhibitor) resulted in reduced cytokine levels, particularly those driven by NFκB signalling [36] (Fig. 2, see green box). Importantly, rapamycin inhibited prostate tumour growth in vivo via suppression of senescent fibroblasts (Fig. 2, see green box). Similarly, Sharma et al. (2016) reported that radiation exposure activates ADAM17 in non‐small cell lung cancer, resulting in the secretion of multiple SASP‐related factors, including ALCAM (activated leukocyte cell adhesion molecule) and amphiregulin, resulting in enhanced growth factor signalling and increased cytotoxicity in animal models [59].

Overall, having a more comprehensive understanding of SASP activation in chemotherapy‐ and radiation‐treated cancer cells and the TME will allow for the development of more tailored therapies, according to the patient’s response. If treatment can be precisely regulated to benefit not just survival, but also the patient’s treatment experience by reducing some of the extreme side effects as discussed, it will be beneficial for a wide‐reaching population of cancer patients.

2.2. The immunomodulatory roles of SASP in the context of immunotherapy

As immunotherapy is a relatively new modality in cancer treatment, few studies have investigated how senescence, and the associated SASP, is implicated in its therapeutic mechanisms. Nevertheless, there are a few indications that immunotherapy can drive TIS. For example, Däbritz et al. (2016) reported that rituximab, a CD20‐targeting monoclonal antibody, elevated intracellular reactive oxygen species (ROS) in B‐cell lymphoma, inducing and enhancing a SASP programme in these cells [60] (Fig. 2, see blue box). In this study, SASP was shown to sensitise these cells to the chemotherapy drugs Dox and vincristine, resulting in a pro‐inflammatory network that not only reinforced senescent behaviour, but also improved immune cell clearing [60] (Fig. 2, see blue box).

As it stands, it is still unclear how prominent the SASP phenomenon is following immunotherapy as a stand‐alone treatment, with further research required. The majority of evidence in this area has focussed on targeting senescent cells induced by first‐line treatments, to then enhance the efficacy of immunotherapy. For example, Zhao et al. (2020) revealed that ovarian cancer cells exposed to cisplatin underwent a SASP that was dependent on topoisomerase 1‐DNA covalent cleavage complex (TOP1cc). Knockdown of HMGB2, which stabilises TOP1cc, resulted in decreased efficacy of anti‐PD‐1 blockade, suggesting that this signalling axis plays a key role in checkpoint efficacy [61]. Hao et al. (2020) then built upon these results by combining cisplatin with a topoisomerase 1 (TOP1) inhibitor, which promotes the formation of TOP1cc by sequestering the complex on the DNA. This combination therapy boosted the SASP, thereby sensitising the ovarian cells to anti‐PD‐1 treatment, which resulted in increased infiltration of activated T cells and dendritic cells (DCs) [62]. Furthermore, Jerby‐Arnon and colleagues (2018) used single‐cell RNA sequencing (sc‐RNAseq) to identify an anti‐PD‐1‐resistant population in melanoma [63]. From here, they found that CDK4/6 inhibition reversed this resistant phenotype by inducing components of SASP, therefore enhancing the effectiveness of checkpoint blockade [63].

It is important to note that, although SASP can be immunostimulatory in some cellular contexts, there are also many settings where SASP can instead drive an immunosuppressive phenotype. For example, in Pten‐null prostate tumours, activation of the JAK2/STAT3 signalling pathway promotes a senescent phenotype where secretion of pro‐inflammatory cytokines such as CXCL1/CXCL2, IL‐6 and macrophage colony‐stimulating factor (M‐CSF) recruits myeloid‐derived suppressor cells to the tumour site, thereby inhibiting effective cytotoxic T‐cell responses [37]. Combination of a JAK2 inhibitor with chemotherapy inhibited this SASP pro‐inflammatory network, increasing infiltration of T cells and decreasing tumour burden [37]. Interestingly, the immunosuppressive effects of the SASP are not only localised to the primary tumour. For example, Luo et al. (2016) reported that senescent osteoblasts secreting IL‐6 increased local bone resorption, thereby fostering a prometastatic niche in the bone of breast cancer patients, driving metastatic outgrowth [64]. This group later found that the IL‐6 secreted by senescent stromal cells can recruit myeloid‐derived suppressor cells, inhibiting effective antitumour T‐cell responses [14]. It is clear that, in settings where SASP induces an immunosuppressive phenotype, ablation of these senescent cells could help stimulate antitumour immune responses. Recently, chimeric antigen receptor (CAR) T cells against a broad senescent cell marker, urokinase‐type plasminogen activator receptor (uPAR), have been utilised to ablate senescent cells during liver fibrosis and lung adenocarcinomas, exhibiting increased survival and decreased associated toxicities, and have exciting implications for the ablation of protumorigenic senescent cells in other cancer types [65].

Cancer cell‐derived lysosomes, although not strictly a SASP component, can also have an immunomodulatory effect in the TME, reducing efficacy of immunotherapy in melanoma. This was shown by Satana‐Magal et al. (2020): tumour‐infiltrating DCs, which usually enhance cytotoxic T‐cell‐mediated cancer killing, were progressively depleted in mouse models of melanoma [66]. The authors established that the DCs were undergoing apoptosis due to their uptake of cancer cell lysosomes, which resulted in incomplete clearance of melanoma lesions and reduced immunotherapy efficacy [66]. This study highlights the diversity of cancer cell secretions in the context of therapy resistance for emerging anticancer therapies such as immunotherapy. As the SASP plays a fundamental immunomodulatory role in many cancer types, further understanding and manipulation of this phenotype might represent an important step towards enhancing the efficacy of immunotherapy and could also help explain the variation in patient response often found in the clinical setting.

2.3. Targeted cancer therapies can induce a detrimental SASP

Targeted kinase inhibitors for specific oncogenic drivers are an emerging area within oncology and have been shown to be clinically effective in some settings; however, complete tumour remission is rare due to development of chemoresistance or adverse effects [67]. For example, hyperactivity of the cyclin‐dependent kinase proteins (CDKs) is often observed in cancer, as it allows the cells to pass through the cell cycle at an accelerated rate [68]. In the past two decades, CDK4/6 inhibitors (CDK4/6i) have offered promising opportunities for normalising the continual proliferative capabilities of malignant cells. By initiating cell cycle arrest at the G1 phase, CDK4/6i have been shown to effectively block the normal function of CDK4 and CDK6, thereby halting the transition into S phase, which allows the cell to cycle [69]. As their primary goal is to halt the cell cycle, CDK4/6i can induce a transient senescence of cancer cells [70], and therefore, their ability to produce a damaging SASP must be considered. Stemming from their original work in 2009 [32], Guan et al. (2017) recently showed that prolonged exposure to palbociclib, a CDK4/6i, could induce senescence in normal fibroblasts in a DNA damage‐independent mechanism [53] (Fig. 2, see yellow box). They showed that senescent fibroblasts harboured an increased degradation of Mdm2, promoting downregulation of p53, while also holding elevated p21Cip1/Waf1 expression, the cumulation of which they suggest triggers senescence and activates the pro‐inflammatory SASP (Fig. 2, see yellow box). In vivo, the senescent fibroblasts aided tumorigenesis in four genetically distinct lines of melanoma [53]. Although the authors referred to this DNA damage‐independent mechanism in a previous publication [71], further work should be considered regarding this noncanonical senescence pathway to confirm that the protumorigenic effects of the CDK4/6i‐induced SASP are truly causative of this transcriptional signature activity.

More recently, Wang et al. (2020) have shown that abemaciclib and palbociclib did indeed induce senescence in resident fibroblasts but did not induce the NFκB‐mediated and pro‐inflammatory SASP [72]. This again was the result of a DNA damage‐independent mechanism, and the authors showed that the SASP from some of the senescent fibroblasts lacked the normal pro‐inflammatory phenotype and instead was driven by p53 transcriptional activity instead of NFκB, which produced an independent programme that the authors termed ‘PASP’ [72]. The PASP‐only expressing cells, in this circumstance, were reported to be cleared more quickly by the immune system than the NFκB‐driven SASP cells (named ‘NASP’), thereby removing the possibility of detrimental effects of senesced nonmalignant cells, reported in previous studies [53]. This study may challenge the previously established dogma that senescence of nonmalignant cells always contributes to enhanced tumorigenesis and also brings to light that distinct phenotypes of the SASP can be driven by differing transcriptional programmes.

Other kinase inhibitors have also been implicated in inducing a detrimental SASP. For example, Obenauf et al. (2015) found that treatment with kinase inhibitors against BRAF, ALK (anaplastic lymphoma kinase) or EGFR mutations significantly modulates the secretome of drug‐sensitive cancer cells. This drug‐altered secretome paradoxically creates a tumour microenvironment which supports inhibitor‐resistant cancer cell clones, promoting tumour progression [54]. Interestingly, Mastri et al. (2018) reported that a VEGFR tyrosine kinase inhibitor can induce a ‘transient pseudosenescent secretory’ phenotype in cancer cells, which have become resistant to the treatment. Once treatment is halted, these cells drive significant rebound growth at both primary and metastatic sites in preclinical models [73]. Similarly, Wang et al. (2019) reported that fibroblast growth factor receptor (FGFR) inhibitor resistance in lung cancer is initially mediated by the cancer cell secretome activating STAT3 signalling; however, they also showed that this resistance could be enhanced via interactions with both fibroblasts and macrophages [74]. Rho‐associated protein kinase (ROCK) inhibitors have recently been reported to improve chemotherapy delivery and reduce metastases in cancers such as pancreas and breast [75, 76, 77]. Interestingly, Niklander et al. (2020) found that the ROCK inhibitor Y‐27632 could decrease activity of several factors within the pro‐inflammatory SASP, without altering cell cycle arrest in oral dysplastic keratinocytes [78]. The authors show that this is mediated by IL‐1 inhibition from Y‐27632, which in turn regulated the secretion of protumorigenic SASP components such as IL‐6 and IL‐8 [78]. This study therefore offers an interesting insight into, and highlights a potential added benefit of, ROCK inhibition: the reduced production of pro‐inflammatory and protumorigenic IL‐6 and IL‐8.

On the whole, kinase therapies offer new hope for improving responses in specific cancers by tailoring the antitumorigenic effects to known molecular mechanisms occurring within that cancer. Less is known about the consequences of kinase‐therapy‐induced senescence and associated SASP, and more work will be required to understand the apparent cancer type‐ and therapy‐driven differences.

3. Senolytics and senostatics: targeting and utilising the SASP

Considering the potential risk of accumulating protumorigenic senescent cells, novel mechanisms to selectively target senescent cancer cells following treatment are now being researched. Moreover, the concept of synthetic lethality [79], also known as the ‘two‐step’ approach, has gained traction in recent times, with growing evidence exploring the idea of inducing vulnerability in cancer cells to then eliminate them with a second agent [80]. Following TIS, second‐line therapies can target senescent cells by two methods: (a) selectively killing the senescent cells and therefore removing the possibility of the SASP impacting tumorigenesis; or (b) directly targeting and inhibiting the SASP‐related factors, thereby reducing the potential for toxic reactions in the TME [81, 82]. These exciting therapeutic approaches, known under the broad terms of senolytics and senostatics, respectively, will be discussed further below (and summarised in Table 1).

Table 1.

Summary table of senolytic and senostatic drugs currently being utilised to target SASP in various cancers. BCL‐2, B‐cell lymphoma 2; EOC, epithelial ovarian cancer; FBP1, fructose‐bisphosphatase 1; HCC, hepatocellular carcinoma; HNSCC, head and neck squamous cell carcinoma; NAMPT, nicotinamide phosphoribosyltransferase; PARP, poly(ADP‐ribose) polymerase; TNBC, triple‐negative breast cancer; TOP1, topoisomerase 1; uPAR, urokinase‐type plasminogen activator receptor.

| Drug name | Target | Effect | References |

|---|---|---|---|

| Senolytics | |||

| ABT‐263 (Navitoclax) | BLC‐2 inhibitor | ↓ HCC tumour growth following FBP1 loss via SASP inhibition | [44, 85, 86] |

| ↓ PARP inhibitor induced senescent cells in ovarian and breast cancer | |||

| ↓ Metastatic burden by targeting TIMP1‐deficient senescent cells in prostate cancer | |||

| GX15‐070 (Obatoclax) | BCL‐2 inhibitor | ↑ Apoptosis of senescent cells induced by BET inhibition in TNBC | [84, 87] |

| ↓ Senescent cells induced by BMI1 inhibition enhancing tumour killing in DIPG | |||

| uPAR CAR T cells | uPAR | ↓ Senescent cells extending lung adenocarcinoma survival. | [65] |

| Senostatics | |||

| Dasatinib | SRC‐family protein‐tyrosine kinase inhibitor | ↓ HCC tumour growth following FBP1 loss via SASP inhibition | [44] |

| FK866/GMX1778 | NAMPT inhibitor | ↓ Senescent‐associated cancer stem cell outgrowth in EOC | [9, 46] |

| Irinotecan | TOP1 inhibitor | ↑ SASP in ovarian cancer sensitising cells to anti‐PD‐1 therapy | [62] |

| Metformin | Gluconeogenesis inhibition | ↓ mTOR and STAT3 pathway signalling in response to a CDK4/6 inhibitor repressing the stemness of HNSCC cancer cells. | [89] |

| NVP‐BSK805 | JAK2 inhibitor | ↓ SASP in Pten‐deficient prostate tumours leading to increased CD8 activity | [36] |

| Rapamycin | mTOR inhibitor | ↓ Senescent fibroblasts in prostate cancer inhibiting tumour growth | [35] |

| Sertraline | Serotonin reuptake inhibitor | ↓ mTOR signalling in HCC senescent cells causing apoptosis and reduction of tumour growth | [90] |

| Y‐27632 | ROCK inhibitor | ↓ IL‐6 and IL‐8 production from senescent oral keratinocytes | [78] |

Senescent cells are able to persist without cell death, partly due to an upregulation of anti‐apoptotic network pathways [83], and as such, many senolytic studies involve targeting the B‐cell lymphoma 2 (BCL‐2) family, which regulates cell apoptosis to enhance senescent cancer cell killing. For example, GX15‐070 (obatoclax mesylate), a BCL‐2 inhibitor, was shown to improve bromodomain and extraterminal protein inhibitors (BETi) in TNBC [84]. Similarly, another BCL‐2 inhibitor, ABT‐263 (Navitoclax), was reported to eliminate senescent cells and enhance the efficacy of olaparib, a poly(ADP‐ribose) polymerase (PARP) inhibitor, in both breast and ovarian cancer cell lines [85]. Furthermore, in a preclinical model of prostate cancer, TIMP1 loss, a pan‐matrix metalloproteinase inhibitor, was reported to promote metastasis in senescent tumours [86]. When targeting TIMP1‐deficient senescent tumour cells with ABT‐263, the authors showed that the metastatic potential was significantly reduced. Moreover, docetaxel treatment, which is standard chemotherapy for prostate cancer, perpetrated TIS and exacerbated metastasis in TIMP1‐deficient cancer cells, but this reaction could be rescued with ABT‐263, thereby reducing metastatic events [86].

Balakrishnan et al. (2020) have recently used obatoclax, a BH3 mimetic, in diffuse intrinsic pontine glioma (DIPG), an aggressive paediatric brain tumour. Due to an epigenomic mutation of H3K27M that is characteristic of the disease, increased expression of a polycomb complex protein, BMI1, causes cancer cells to senesce and drive the SASP [87]. By inhibiting BMI1 using a small molecule inhibitor and combining this with obatoclax, the authors showed significant improvement in survival and tumour regression [87]. Delay to tumour regrowth was sustained after drugs were removed, suggesting that this dual therapy could have long‐term benefits. This study highlights an exciting senolytic therapy option for a normally fatal childhood brain tumour. This preclinical work also supports an ongoing clinical trial in which a BMI1 small molecule inhibitor (PTC596) is being used in combination with radiotherapy, which was started without substantial in vivo research (NCT03605550). Similarly, Ruscetti et al. (2020) showed that treatment with CDK4/6i triggered the production of pro‐angiogenic SASP factors such as VEGF, basic FGF (bFGF), PDGFα and β, as well as multiple MMPs, resulting in vascular remodelling in preclinical models of PDAC [20]. In this study, the authors showed that this enhanced gemcitabine chemotherapy delivery to the tumours, while also enhancing cytotoxic T‐cell infiltration [20]. Then, due to this improved immunogenicity, the efficacy of checkpoint blockade via anti‐PD‐1 was enhanced, increasing overall survival [20]. However, although this study provides strong rationale for combining SASP‐inducing therapies with other treatment modalities, such as chemotherapy and/or immunotherapy, layering treatments in this manner will likely increase the risk of toxicity in cancer patients, with further research required to elucidate whether this is a viable therapeutic route within the clinic.

It is important to remember that, although senescence does play a role in these detrimental effects after cancer therapy, it has also evolved to accompany humans as they age. Recent work has shown that senescent cells may remain biologically functional in some situations, such as in pancreatic β‐cells, where senescent cells increase secretion of insulin to compensate for decreased proliferation [88]. Therefore, the use of senolytic therapy should be considered with caution, and much more research is needed prior to application in humans.

A more moderate approach may be instead to modulate factors secreted by senescent cells through the use of senostatics. However, as previously discussed, the SASP shares many overlapping secreted factors that have important physiological functions. As such, many researchers are now working to identify a more precise SASP. For example, in a large‐scale small interfering RNA (siRNA) screen for regulators of SASP, Georgilis et al. (2018) identified 50 genes, including splicing factor PTBP1, whose depletion prevents the protumorigenic effects of SASP, such as NFκB‐driven inflammation, without impacting senescence growth arrest [19]. This study highlights that targeting specific aspects of SASP may be the key to exploiting this complex reaction, especially when the malignancy is driven by inflammation [19].

Regulating the activity of the SASP has also been shown to be effective in head and neck squamous cell carcinoma (HNSCC) by repurposing the hyperglycaemic drug metformin [89]. In this study, Hu et al. (2020) demonstrate that the efficacy of a CDK4/6i (LY2835219) can be potentiated by administering it in combination with metformin. LY2835219 successfully prevented cell cycling into S phase, whereas metformin inhibited mTOR and STAT3 pathways that are normally upregulated in the SASP by senescent HNSCC cells following CDK4/6 inhibition [89]. Furthermore, the synergistic effect of combining the drugs resulted in a more efficient cell cycle arrest than when LY2835219 was administered alone and, when combined, reduced the expression of several pro‐inflammatory proteins known to be within the SASP and to aid tumorigenesis, such as IL‐6, IL‐8 and CXCL2 [89]. Overall, the authors showed that, by regulating the SASP following CDK4/6 inhibition, the stemness of the cancer cells could be repressed via the IL‐6‐STAT3 axis. Similarly, Wang et al. (2019) reported that targeting liver cancer cells with CDC7, a DNA‐replication kinase, followed by sertraline, a commonly prescribed antidepressant, enhanced cancer cell death. In this study, targeting CDC7 induced senescence and the associated SASP, after which sertraline triggered apoptosis via suppressed mTOR signalling [90]. These studies are exciting examples of a growing field where FDA‐approved drugs are repurposed in other disease settings. Considering the long journey to developing FDA‐approved drugs, this offers new hope for a fast‐tracked approach to cancer therapy.

4. Future perspectives

Many chemotherapeutic agents are successful in tackling cancer by inflicting high levels of DNA damage, but only recently have we begun to understand the secondary and often opposing effects of these treatments. Senescence and the associated SASP can affect not only malignant cells, but also cells within the TME, which have been shown to be detrimental in several preclinical models of cancer. Aside from assisting in tumorigenesis, the SASP has also been shown to affect other unwanted side effects of chemotherapies. For example, Dox‐treated fibroblasts became senescent and secreted SASP factors associated with haemostasis, where activated platelets produced harmful blood clots [91]. Furthermore, evidence from the past decade is collectively highlighting that the SASP is a particularly diverse phenomenon that can be manipulated depending on the stressor‐derived transcriptional driver and the cell that it is occurring in. In particular, studies have recently shown that there are highly pro‐inflammatory SASPs that promote the secretion of protumorigenic factors such as IL‐1A and IL‐6 and less inflammatory SASPs that promote the clearance of senescent cells by the immune system, by secreting factors such as TGF‐β [31]. Novel investigations are now pursuing the idea of either clearing senescent and SASP‐producing cells or equilibrating the activity of specific SASP factors by pharmacological inhibition in combination with primary anticancer therapies. This remains a difficult but important area of research, as we are still learning of the protective elements of the SASP after TIS and eliminating all SASP‐related factors might impact other physiological functions, such as wound healing [92]. Overall, the research of senotherapies is an extremely promising area of cancer pharmacology that may in the future reduce the adverse effects of senescence and the SASP following cancer therapy.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Acknowledgements

CRC is supported by the Baxter Family Postgraduate Scholarship. SR is supported by the University of New South Wales (UNSW) University International Postgraduate Award. BAP is supported by the Sydney Catalyst Seed Funding Grant. PT is supported by the Len Ainsworth Fellowship in Pancreatic Cancer Research and is a National Health and Medical Research Council (NHMRC) Senior Research Fellow. This work was made possible by an Avner Pancreatic Cancer Foundation Grant. This work was supported by Suttons, Sydney Catalyst, Australian Research Council (ARC), NHMRC, Cancer Council NSW, Cancer Institute NSW, National Breast Cancer Foundation (NBCF) and St. Vincent’s Clinic Foundation. The manuscript figures were created with BioRender.com.

Cecilia R. Chambers and Shona Ritchie are co‐first authors

Contributor Information

Brooke A. Pereira, Email: b.pereira@garvan.org.au.

Paul Timpson, Email: p.timpson@garvan.org.au.

References

- 1. Campisi J & d'Adda di Fagagna F (2007) Cellular senescence: when bad things happen to good cells. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol 8, 729–740. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Martincorena I, Raine KM, Gerstung M, Dawson KJ, Haase K, Van Loo P, Davies H, Stratton MR & Campbell PJ (2017) Universal patterns of selection in cancer and somatic tissues. Cell 171, 1029–1041. 10.1016/j.cell.2017.09.042 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Hernandez‐Segura A, Nehme J & Demaria M (2018) Hallmarks of cellular senescence. Trends Cell Biol 28, 436–453. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Wang B, Kohli J & Demaria M (2020) Senescent cells in cancer therapy: friends or foes? Trends Cancer 6, 838–857. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Coppé J‐P, Patil CK, Rodier F, Sun Y, Muñoz DP, Goldstein J, Nelson PS, Desprez P‐Y & Campisi J (2008) Senescence‐associated secretory phenotypes reveal cell‐nonautonomous functions of oncogenic RAS and the p53 tumor suppressor. PLoS Biol 6, e301. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Canino C, Mori F, Cambria A, Diamantini A, Germoni S, Alessandrini G, Borsellino G, Galati R, Battistini L, Blandino R et al., (2012) SASP mediates chemoresistance and tumor‐initiating‐activity of mesothelioma cells. Oncogene 31, 3148–3163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Laberge RM, Awad P, Campisi J & Desprez PY (2012) Epithelial‐mesenchymal transition induced by senescent fibroblasts. Cancer Microenviron 5, 39–44. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Milanovic M, Fan DNY, Belenki D, Däbritz JHM, Zhao Z, Yu Y, Dörr JR, Dimitrova L, Lenze D, Monteiro Barbosa IA et al., (2018) Senescence‐associated reprogramming promotes cancer stemness. Nature 553, 96–100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Nacarelli T, Fukumoto T, Zundell JA, Fatkhutdinov N, Jean S, Cadungog MG, Borowsky ME & Zhang R (2020) NAMPT inhibition suppresses cancer stem‐like cells associated with therapy‐induced senescence in ovarian cancer. Cancer Res 80, 890–900. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Kim YH, Choi YW, Lee J, Soh EY, Kim J‐H & Park TJ (2017) Senescent tumor cells lead the collective invasion in thyroid cancer. Nat Commun 8, 1–14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Coppé J‐P, Kauser K, Campisi J & Beauséjour CM (2006) Secretion of vascular endothelial growth factor by primary human fibroblasts at senescence. J Biol Chem 281, 29568–29574. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Toste PA, Nguyen AH, Kadera BE, Duong M, Wu N, Gawlas I, Tran LM, Bikhchandani M, Li L, Patel SG et al., (2016) Chemotherapy‐induced inflammatory gene signature and protumorigenic phenotype in pancreatic CAFs via stress‐associated MAPK. Mol Cancer Res 14, 437–447. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Eggert T, Wolter K, Ji J, Ma C, Yevsa T, Klotz S, Medina‐Echeverz J, Longerich T, Forgues M, Reisinger F et al., (2016) Distinct functions of senescence‐associated immune responses in liver tumor surveillance and tumor progression. Cancer Cell 30, 533–547. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Ruhland MK, Loza AJ, Capietto A‐H, Luo X, Knolhoff BL, Flanagan KC, Belt BA, Alspach E, Leahy K, Luo J et al., (2016) Stromal senescence establishes an immunosuppressive microenvironment that drives tumorigenesis. Nat Commun 7, 11762. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Angelini PD, Zacarias Fluck MF, Pedersen K, Parra‐Palau JL, Guiu M, Bernadó Morales C, Vicario R, Luque‐García A, Navalpotro NP, Giralt J et al., (2013) Constitutive HER2 signaling promotes breast cancer metastasis through cellular senescence. Cancer Res 73, 450–458. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Demaria M, O'Leary MN, Chang J, Shao L, Liu S, Alimirah F, Koenig K, Le C, Mitin N & Deal AM (2017) Cellular senescence promotes adverse effects of chemotherapy and cancer relapse. Cancer Discov 7, 165–176. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Georgilis A, Klotz S, Hanley CJ, Herranz N, Weirich B, Morancho B, Leote AC, D'Artista L, Gallage S, Seehawer M et al., (2018) PTBP1‐mediated alternative splicing regulates the inflammatory secretome and the pro‐tumorigenic effects of senescent cells. Cancer Cell 34, 85–102.e109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Jackson JG, Pant V, Li Q, Chang LL, Quintás‐Cardama A, Garza D, Tavana O, Yang P, Manshouri T, Li Y et al., (2012) p53‐mediated senescence impairs the apoptotic response to chemotherapy and clinical outcome in breast cancer. Cancer Cell 21, 793–806. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Sun Y, Campisi J, Higano C, Beer TM, Porter P, Coleman I, True L & Nelson PS (2012) Treatment‐induced damage to the tumor microenvironment promotes prostate cancer therapy resistance through WNT16B. Nat Med 18, 1359–1368. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Ruscetti M, Morris JP, Mezzadra R, Russell J, Leibold J, Romesser PB, Simon J, Kulick A, Ho Y‐J, Fennell M et al., (2020) Senescence‐induced vascular remodeling creates therapeutic vulnerabilities in pancreas cancer. Cell 181, 424–441.e421. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Chien Y, Scuoppo C, Wang X, Fang X, Balgley B, Bolden JE, Premsrirut P, Luo W, Chicas A & Lee CS (2011) Control of the senescence‐associated secretory phenotype by NF‐κB promotes senescence and enhances chemosensitivity. Genes Dev 25, 2125–2136. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Iannello A, Thompson TW, Ardolino M, Lowe SW & Raulet DH (2013) p53‐dependent chemokine production by senescent tumor cells supports NKG2D‐dependent tumor elimination by natural killer cells. J Exp Med 210, 2057–2069. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Kang T‐W, Yevsa T, Woller N, Hoenicke L, Wuestefeld T, Dauch D, Hohmeyer A, Gereke M, Rudalska R & Potapova A (2011) Senescence surveillance of pre‐malignant hepatocytes limits liver cancer development. Nature 479, 547–551. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Cupit‐Link MC, Kirkland JL, Ness KK, Armstrong GT, Tchkonia T, LeBrasseur NK, Armenian SH, Ruddy KJ & Hashmi SK (2017) Biology of premature ageing in survivors of cancer. ESMO Open 2, e000250. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Acosta JC, O'Loghlen A, Banito A, Guijarro MV, Augert A, Raguz S, Fumagalli M, Da Costa M, Brown C, Popov N et al., (2008) Chemokine signaling via the CXCR2 receptor reinforces senescence. Cell 133, 1006–1018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Kuilman T, Michaloglou C, Vredeveld LC, Douma S, van Doorn R, Desmet CJ, Aarden LA, Mooi WJ & Peeper DS (2008) Oncogene‐induced senescence relayed by an interleukin‐dependent inflammatory network. Cell 133, 1019–1031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Acosta JC, Banito A, Wuestefeld T, Georgilis A, Janich P, Morton JP, Athineos D, Kang TW, Lasitschka F, Andrulis M et al., (2013) A complex secretory program orchestrated by the inflammasome controls paracrine senescence. Nat Cell Biol 15, 978–990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Takasugi M, Okada R, Takahashi A, Virya Chen D, Watanabe S & Hara E (2017) Small extracellular vesicles secreted from senescent cells promote cancer cell proliferation through EphA2. Nat Commun 8, 15729. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Campisi J (2013) Aging, cellular senescence, and cancer. Annu Rev Physiol 75, 685–705. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Faget DV, Ren Q & Stewart SA (2019) Unmasking senescence: context‐dependent effects of SASP in cancer. Nat Rev Cancer 19, 439–453. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Rodier F, Coppé J‐P, Patil CK, Hoeijmakers WA, Muñoz DP, Raza SR, Freund A, Campeau E, Davalos AR & Campisi J (2009) Persistent DNA damage signalling triggers senescence‐associated inflammatory cytokine secretion. Nat Cell Biol 11, 973–979. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Goehe RW, Di X, Sharma K, Bristol ML, Henderson SC, Valerie K, Rodier F, Davalos AR & Gewirtz DA (2012) The autophagy‐senescence connection in chemotherapy: must tumor cells (self) eat before they sleep? J Pharmacol Exp Ther 343, 763–778. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Alspach E, Flanagan KC, Luo X, Ruhland MK, Huang H, Pazolli E, Donlin MJ, Marsh T, Piwnica‐Worms D, Monahan J et al., (2014) p38MAPK plays a crucial role in stromal‐mediated tumorigenesis. Cancer Discov 4, 716–729. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Freund A, Patil CK & Campisi J (2011) p38MAPK is a novel DNA damage response‐independent regulator of the senescence‐associated secretory phenotype. EMBO J 30, 1536–1548. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Laberge R‐M, Sun Y, Orjalo AV, Patil CK, Freund A, Zhou L, Curran SC, Davalos AR, Wilson‐Edell KA & Liu S (2015) MTOR regulates the pro‐tumorigenic senescence‐associated secretory phenotype by promoting IL1A translation. Nat Cell Biol 17, 1049–1061. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Toso A, Revandkar A, Di Mitri D, Guccini I, Proietti M, Sarti M, Pinton S, Zhang J, Kalathur M, Civenni G et al., (2014) Enhancing chemotherapy efficacy in Pten‐deficient prostate tumors by activating the senescence‐associated antitumor immunity. Cell Rep 9, 75–89. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Coppe JP, Rodier F, Patil CK, Freund A, Desprez PY & Campisi J (2011) Tumor suppressor and aging biomarker p16(INK4a) induces cellular senescence without the associated inflammatory secretory phenotype. J Biol Chem 286, 36396–36403. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Efeyan A, Ortega‐Molina A, Velasco‐Miguel S, Herranz D, Vassilev LT & Serrano M (2007) Induction of p53‐dependent senescence by the MDM2 antagonist nutlin‐3a in mouse cells of fibroblast origin. Cancer Res 67, 7350–7357. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Wiley CD, Schaum N, Alimirah F, Lopez‐Dominguez JA, Orjalo AV, Scott G, Desprez PY, Benz C, Davalos AR & Campisi J (2018) Small‐molecule MDM2 antagonists attenuate the senescence‐associated secretory phenotype. Sci Rep 8, 2410. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Hernandez‐Segura A, de Jong TV, Melov S, Guryev V, Campisi J & Demaria M (2017) Unmasking transcriptional heterogeneity in senescent cells. Curr Biol 27, 2652–2660.e4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Debacq‐Chainiaux F, Erusalimsky JD, Campisi J & Toussaint O (2009) Protocols to detect senescence‐associated beta‐galactosidase (SA‐betagal) activity, a biomarker of senescent cells in culture and in vivo. Nat Protoc 4, 1798–1806. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Basisty N, Kale A, Jeon OH, Kuehnemann C, Payne T, Rao C, Holtz A, Shah S, Sharma V, Ferrucci L et al., (2020) A proteomic atlas of senescence‐associated secretomes for aging biomarker development. PLoS Biol 18, e3000599. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Yoshimoto S, Loo TM, Atarashi K, Kanda H, Sato S, Oyadomari S, Iwakura Y, Oshima K, Morita H, Hattori M et al., (2013) Obesity‐induced gut microbial metabolite promotes liver cancer through senescence secretome. Nature 499, 97–101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Li F, Huangyang P, Burrows M, Guo K, Riscal R, Godfrey J, Lee KE, Lin N, Lee P, Blair IA et al., (2020) FBP1 loss disrupts liver metabolism and promotes tumorigenesis through a hepatic stellate cell senescence secretome. Nat Cell Biol 22, 728–739. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Dorr JR, Yu Y, Milanovic M, Beuster G, Zasada C, Dabritz JH, Lisec J, Lenze D, Gerhardt A, Schleicher K et al., (2013) Synthetic lethal metabolic targeting of cellular senescence in cancer therapy. Nature 501, 421–425. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Nacarelli T, Lau L, Fukumoto T, Zundell J, Fatkhutdinov N, Wu S, Aird KM, Iwasaki O, Kossenkov AV, Schultz D et al., (2019) NAD(+) metabolism governs the proinflammatory senescence‐associated secretome. Nat Cell Biol 21, 397–407. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Galli U, Colombo G, Travelli C, Tron GC, Genazzani AA & Grolla AA (2020) Recent advances in NAMPT inhibitors: a novel immunotherapic strategy. Front Pharmacol 11, 656. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Heske CM (2019) Beyond energy metabolism: exploiting the additional roles of NAMPT for cancer therapy. Front Oncol 9, 1514. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Tonnessen‐Murray CA, Frey WD, Rao SG, Shahbandi A, Ungerleider NA, Olayiwola JO, Murray LB, Vinson BT, Chrisey DB, Lord CJ et al., (2019) Chemotherapy‐induced senescent cancer cells engulf other cells to enhance their survival. J Cell Biol 218, 3827–3844. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Logue SE, McGrath EP, Cleary P, Greene S, Mnich K, Almanza A, Chevet E, Dwyer RM, Oommen A, Legembre P et al., (2018) Inhibition of IRE1 RNase activity modulates the tumor cell secretome and enhances response to chemotherapy. Nat Commun 9, 3267. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Wang Y, Zong X, Mitra S, Mitra AK, Matei D & Nephew KP (2018) IL‐6 mediates platinum‐induced enrichment of ovarian cancer stem cells. JCI Insight 3, e122360. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Shen M, Dong C, Ruan X, Yan W, Cao M, Pizzo D, Wu X, Yang L, Liu L, Ren X et al., (2019) Chemotherapy‐induced extracellular vesicle miRNAs promote breast cancer stemness by targeting ONECUT2 . Cancer Res 79, 3608–3621. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Guan X, LaPak KM, Hennessey RC, Yu CY, Shakya R, Zhang J & Burd CE (2017) Stromal senescence by prolonged CDK4/6 inhibition potentiates tumor growth. Mol Cancer Res 15, 237–249. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Gilbert LA & Hemann MT (2010) DNA damage‐mediated induction of a chemoresistant niche. Cell 143, 355–366. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Obenauf AC, Zou Y, Ji AL, Vanharanta S, Shu W, Shi H, Kong X, Bosenberg MC, Wiesner T, Rosen N et al., (2015) Therapy‐induced tumour secretomes promote resistance and tumour progression. Nature 520, 368–372. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Yao Z, Murali B, Ren Q, Luo X, Faget DV, Cole T, Ricci B, Thotala D, Monahan J, van Deursen JM et al., (2020) Therapy‐induced senescence drives bone loss. Cancer Res 80, 1171–1182. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Baar MP, Brandt RMC, Putavet DA, Klein JDD, Derks KWJ, Bourgeois BRM, Stryeck S, Rijksen Y, van Willigenburg H, Feijtel DA et al., (2017) Targeted apoptosis of senescent cells restores tissue homeostasis in response to chemotoxicity and aging. Cell 169, 132–147.e116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Wu J, Qin H, Li T, Cheng K, Dong J, Tian M, Chai N, Guo H, Li J, You X et al., (2016) Characterization of site‐specific glycosylation of secreted proteins associated with multi‐drug resistance of gastric cancer. Oncotarget 7, 25315–25327. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Sharma A, Bender S, Zimmermann M, Riesterer O, Broggini‐Tenzer A & Pruschy MN (2016) Secretome signature identifies ADAM17 as novel target for radiosensitization of non‐small cell lung cancer. Clin Cancer Res 22, 4428–4439. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Däbritz JHM, Yu Y, Milanovic M, Schönlein M, Rosenfeldt MT, Dörr JR, Kaufmann AM, Dörken B & Schmitt CA (2016) CD20‐targeting immunotherapy promotes cellular senescence in B‐cell lymphoma. Mol Cancer Ther 15, 1074–1081. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Zhao B, Liu P, Fukumoto T, Nacarelli T, Fatkhutdinov N, Wu S, Lin J, Aird KM, Tang H‐Y, Liu Q et al., (2020) Topoisomerase 1 cleavage complex enables pattern recognition and inflammation during senescence. Nat Commun 11, 908. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Hao X, Zhao B, Zhou W, Liu H, Fukumoto T, Gabrilovich D & Zhang R (2021) Sensitization of ovarian tumor to immune checkpoint blockade by boosting senescence‐associated secretory phenotype. iScience 24, 102016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63. Jerby‐Arnon L, Shah P, Cuoco MS, Rodman C, Su MJ, Melms JC, Leeson R, Kanodia A, Mei S, Lin JR et al., (2018) A cancer cell program promotes T cell exclusion and resistance to checkpoint blockade. Cell 175, 984–997.e24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64. Luo X, Fu Y, Loza AJ, Murali B, Leahy KM, Ruhland MK, Gang M, Su X, Zamani A, Shi Y et al., (2016) Stromal‐initiated changes in the bone promote metastatic niche development. Cell Rep 14, 82–92. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65. Amor C, Feucht J, Leibold J, Ho YJ, Zhu C, Alonso‐Curbelo D, Mansilla‐Soto J, Boyer JA, Li X, Giavridis T et al., (2020) Senolytic CAR T cells reverse senescence‐associated pathologies. Nature 583, 127–132. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66. Santana‐Magal N, Farhat‐Younis L, Gutwillig A, Gleiberman A, Rasoulouniriana D, Tal L, Netanely D, Shamir R, Blau R, Feinmesser M et al., (2020) Melanoma‐secreted lysosomes trigger monocyte‐derived dendritic cell apoptosis and limit cancer immunotherapy. Cancer Res 80, 1942–1956. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67. Pottier C, Fresnais M, Gilon M, Jerusalem G, Longuespee R & Sounni NE (2020) Tyrosine kinase inhibitors in cancer: breakthrough and challenges of targeted therapy. Cancers (Basel) 12, 731. 10.3390/cancers12030731 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68. Goel S, DeCristo MJ, McAllister SS & Zhao JJ (2018) CDK4/6 inhibition in cancer: beyond cell cycle arrest. Trends Cell Biol 28, 911–925. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69. Finn RS, Dering J, Conklin D, Kalous O, Cohen DJ, Desai AJ, Ginther C, Atefi M, Chen I, Fowst C et al., (2009) PD 0332991, a selective cyclin D kinase 4/6 inhibitor, preferentially inhibits proliferation of luminal estrogen receptor‐positive human breast cancer cell lines in vitro. Breast Cancer Res 11, R77. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70. Goel S, DeCristo MJ, Watt AC, BrinJones H, Sceneay J, Li BB, Khan N, Ubellacker JM, Xie S, Metzger‐Filho O et al., (2017) CDK4/6 inhibition triggers anti‐tumour immunity. Nature 548, 471–475. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71. Kovatcheva M, Liu DD, Dickson MA, Klein ME, O'Connor R, Wilder FO, Socci ND, Tap WD, Schwartz GK, Singer S et al., (2015) MDM2 turnover and expression of ATRX determine the choice between quiescence and senescence in response to CDK4 inhibition. Oncotarget 6, 8226–8243. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72. Wang B, Brandenburg S, Hernandez‐Segura A, van Vliet T, Jongbloed EM, Wilting S, Ohtani N, Jager A & Demaria M (2020) Pharmacological CDK4/6 inhibition unravels a p53‐induced secretory phenotype in senescent cells. bioRxiv 2020.06.05.135715. 10.1101/2020.06.05.135715 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 73. Mastri M, Tracz A, Lee CR, Dolan M, Attwood K, Christensen JG, Liu S & Ebos JML (2018) A transient pseudosenescent secretome promotes tumor growth after antiangiogenic therapy withdrawal. Cell Rep 25, 3706–3720.e3708. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74. Wang X, Ai J, Liu H, Peng X, Chen H, Chen Y, Su Y, Shen A, Huang X, Ding J et al., (2019) The secretome engages STAT3 to favor a cytokine‐rich microenvironment in mediating acquired resistance to FGFR inhibitors. Mol Cancer Ther 18, 667–679. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75. Liu S, Goldstein RH, Scepansky EM & Rosenblatt M (2009) Inhibition of rho‐associated kinase signaling prevents breast cancer metastasis to human bone. Cancer Res 69, 8742–8751. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76. Rath N, Munro J, Cutiongco MF, Jagiello A, Gadegaard N, McGarry L, Unbekandt M, Michalopoulou E, Kamphorst JJ, Sumpton D et al., (2018) Rho kinase inhibition by AT13148 blocks pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma invasion and tumor growth. Cancer Res 78, 3321–3336. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77. Vennin C, Chin VT, Warren SC, Lucas MC, Herrmann D, Magenau A, Melenec P, Walters SN, Del Monte‐Nieto G, Conway JR et al., (2017) Transient tissue priming via ROCK inhibition uncouples pancreatic cancer progression, sensitivity to chemotherapy, and metastasis. Sci Transl Med 9, eaai8504. 10.1126/scitranslmed.aai8504 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78. Niklander S, Bandaru D, Lambert DW & Hunter KD (2020) ROCK inhibition modulates the senescence‐associated secretory phenotype (SASP) in oral keratinocytes. FEBS Open Bio 10, 2740–2749. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79. Huang A, Garraway LA, Ashworth A & Weber B (2020) Synthetic lethality as an engine for cancer drug target discovery. Nat Rev Drug Discov 19, 23–38. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80. Sieben CJ, Sturmlechner I, van de Sluis B & van Deursen JM (2018) Two‐step senescence‐focused cancer therapies. Trends Cell Biol 28, 723–737. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81. Myrianthopoulos V, Evangelou K, Vasileiou PVS, Cooks T, Vassilakopoulos TP, Pangalis GA, Kouloukoussa M, Kittas C, Georgakilas AG & Gorgoulis VG (2019) Senescence and senotherapeutics: a new field in cancer therapy. Pharmacol Ther 193, 31–49. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82. Short S, Fielder E, Miwa S & von Zglinicki T (2019) Senolytics and senostatics as adjuvant tumour therapy. EBioMedicine 41, 683–692. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83. Zhu Y, Tchkonia T, Pirtskhalava T, Gower AC, Ding H, Giorgadze N, Palmer AK, Ikeno Y, Hubbard GB, Lenburg M et al., (2015) The Achilles' heel of senescent cells: from transcriptome to senolytic drugs. Aging Cell 14, 644–658. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84. Gayle SS, Sahni JM, Webb BM, Weber‐Bonk KL, Shively MS, Spina R, Bar EE, Summers MK & Keri RA (2019) Targeting BCL‐xL improves the efficacy of bromodomain and extra‐terminal protein inhibitors in triple‐negative breast cancer by eliciting the death of senescent cells. J Biol Chem 294, 875–886. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85. Fleury H, Malaquin N, Tu V, Gilbert S, Martinez A, Olivier M‐A, Sauriol A, Communal L, Leclerc‐Desaulniers K & Carmona E (2019) Exploiting interconnected synthetic lethal interactions between PARP inhibition and cancer cell reversible senescence. Nat Commun 10, 1–15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86. Guccini I, Revandkar A, D'Ambrosio M, Colucci M, Pasquini E, Mosole S, Troiani M, Brina D, Sheibani‐Tezerji R, Elia AR et al., (2021) Senescence reprogramming by TIMP1 deficiency promotes prostate cancer metastasis. Cancer Cell 39, 68–82.e9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87. Balakrishnan I, Danis E, Pierce A, Madhavan K, Wang D, Dahl N, Sanford B, Birks DK, Davidson N, Metselaar DS et al., (2020) Senescence induced by BMI1 inhibition is a therapeutic vulnerability in H3K27M‐mutant DIPG. Cell Rep 33, 108286. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88. Helman A, Klochendler A, Azazmeh N, Gabai Y, Horwitz E, Anzi S, Swisa A, Condiotti R, Granit RZ, Nevo Y et al., (2016) p16(Ink4a)‐induced senescence of pancreatic beta cells enhances insulin secretion. Nat Med 22, 412–420. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89. Hu Q, Peng J, Jiang L, Li W, Su Q, Zhang J, Li H, Song M, Cheng B, Xia J et al., (2020) Metformin as a senostatic drug enhances the anticancer efficacy of CDK4/6 inhibitor in head and neck squamous cell carcinoma. Cell Death Dis 11, 925. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90. Wang C, Vegna S, Jin H, Benedict B, Lieftink C, Ramirez C, de Oliveira RL, Morris B, Gadiot J, Wang W et al., (2019) Inducing and exploiting vulnerabilities for the treatment of liver cancer. Nature 574, 268–272. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91. Wiley CD, Liu S, Limbad C, Zawadzka AM, Beck J, Demaria M, Artwood R, Alimirah F, Lopez‐Dominguez JA, Kuehnemann C et al., (2019) SILAC analysis reveals increased secretion of hemostasis‐related factors by senescent cells. Cell Rep 28, 3329–3337.e5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92. Demaria M, Ohtani N, Youssef SA, Rodier F, Toussaint W, Mitchell JR, Laberge RM, Vijg J, Van Steeg H, Dolle ME et al., (2014) An essential role for senescent cells in optimal wound healing through secretion of PDGF‐AA. Dev Cell 31, 722–733. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]