Abstract

Toxigenic Clostridium difficile is the most common etiologic agent of hospital-acquired diarrhea in developed countries. The role of this pathogen in nosocomial diarrhea in Eastern Europe has not been clearly established. The goal of this study was to determine the prevalence of C. difficile in patients and the hospital environment in Belarus and to characterize these isolates as to the presence of toxin genes and their molecular type. C. difficile was isolated from 9 of 509 (1.8%) patients analyzed and recovered from 28 of 1,300 (2.1%) environmental sites cultured. A multiplex PCR assay was used to analyze the pathogenicity locus (PaLoc) of all isolates, and strain identity was determined by an arbitrarily primed PCR (AP-PCR). The targeted sequences for all the genes in the PaLoc were amplified in all C. difficile strains examined. A predominantly homogenous group of strains was found among these isolates, with five major AP-PCR groups being identified. Eighty-three percent of environmental isolates were classified into two groups, while patient isolates grouped into three AP-PCR types, two of which were also found in the hospital environment. Although no data on the role of C. difficile infection or epidemiology of C. difficile-associated diarrhea (CDAD) in this country exist, the isolation of toxigenic C. difficile from the hospital environment suggests that this pathogen may be responsible for cases of diarrhea of undiagnosed origin and validates our effort to further investigate the significance of CDAD in Eastern Europe.

Toxigenic Clostridium difficile is the most common cause of hospital-acquired diarrhea in economically developed countries. Few reports on the isolation and identification of C. difficile as a nosocomial pathogen in Eastern European countries exist in the literature. This may be due to the lack of anaerobic technology and facilities for identification of this pathogen in these countries. Meisel-Mikolacjzyk et al. isolated C. difficile from the stools of children and adults hospitalized for different circumstances in Polish hospitals (4, 5). These investigators also isolated C. difficile from the stools of neonates and from the environment of a maternity hospital in Warsaw (5). Genotyping of these isolates identified at least seven major groups among the patient and environmental isolates (6). The significance of C. difficile in the etiology of hospital-acquired diarrhea in Eastern Europe is not known. In the present study, we describe the isolation and characterization of strains of C. difficile from patients with diarrhea and from the environment in hospitals in Belarus.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Patient population.

The patients analyzed in this study had a preliminary diagnosis of colitis and were both inpatients and outpatients. The patients ranged in age from 6 months to 80 years. All patients had diarrhea (loose watery stools two to five times a day). Eight of nine (88%) had colitis; one of these patients was considered to have granulomatous colitis. The antibiotic history was not known for six of nine of these patients. For the other three patients, no consistent agent was identified (ampicillin, chloramphenicol, and a clindamycin-gentamicin combination). The majority of the patients (five of nine) were outpatients. Two patients were in the surgical unit, but no other clusters were seen.

Isolation of C. difficile from patients and the hospital environment.

Stool specimens from patients were cultured on the selective medium cycloserine-cefoxitin-fructose agar (CCFA) (2) and incubated anaerobically for 48 h at 37°C. Isolates were purified by several passages on CCFA and identified as C. difficile by Gram staining, biochemical tests, the Culturette CDT rapid latex agglutination test (Becton-Dickinson, Cockeysville, Md.), and PCR.

To determine the distribution of C. difficile in hospital environments, several units at Belarusian hospitals were selected for this study. Environmental sites were cultured by using sterile premoistened cotton swabs inoculated into brain heart infusion broth and incubated anaerobically at 37°C for 48 to 72 h. The environmental surfaces screened included walls, doorknobs, floors, night tables, bedpans, and washstands. Cultures were then streaked onto CCFA plates, incubated, and purified as described above.

Table 1 lists the strains of C. difficile analyzed in this study and their sources. Isolates 1E to 28E were obtained from the various medical units at the Minsk General Hospitals, Minsk, Belarus, between January and April 1998. Isolates P1 to P9 were cultured from patients with diarrhea (Table 1) between September 1997 and April 1998. With the exception of one patient (patient 8), who was housed in the intensive care unit, the inpatients were not in locations where isolates were recovered from environmental surfaces.

TABLE 1.

A. Characteristics of environmental and patient isolates of C. difficilea

| Isolate type | Isolate no. | Date isolated (mo/yr) | Sourceb | AP-PCR type |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Environmental | 1E | 1/98 | Hem. unit | IV |

| 2E | 2/98 | ICU-Hem-N1 | IV | |

| 3E | 2/98 | ICU-N1 | IV | |

| 4E | 2/98 | CU-N1 | IV | |

| 5E | 2/98 | ICU-N1 | IV | |

| 6E | 2/98 | ICU-N1 | IV | |

| 7E | 2/98 | ICU-N1 | IVa | |

| 8E | 2/98 | ICU-N1 | IVa | |

| 9E | 2/98 | ICU-N1 | IVa | |

| 10E | 2/98 | ICU-N1 | IVa | |

| 11E | 2/98 | ICU-N1 | V | |

| 12E | 2/98 | ICU-N2 | IV | |

| 13E | 2/98 | ICU-N2 | IV | |

| 14E | 2/98 | ICU-N3 | V | |

| 15E | 2/98 | ICU-N3 | V | |

| 16E | 2/98 | ICU-N3 | I | |

| 17E | 2/98 | ICU-N3 | I | |

| 18E | 2/98 | ICU-N3 | I | |

| 19E | 2/98 | ICU-N3 | I | |

| 20E | 2/98 | ICU-N3 | II | |

| 21E | 3/98 | ICU-N4 | I | |

| 22E | 4/98 | ICU-N5 | II | |

| 23E | 4/98 | ICU-N5 | I | |

| Patient | P-1 | 11/97 | II | |

| P-2 | 10/97 | I | ||

| P-3 | 10/97 | I | ||

| P-4 | 10/97 | I | ||

| P-5 | 10/97 | III | ||

| P-6 | 4/98 | III | ||

| P-7 | 3/98 | I | ||

| P-8 | 4/98 | III | ||

| P-9 | 9/97 | I |

All of the isolates contained the genes constituting the PaLoc.

Hem., hematology; ICU, intensive care unit; ICU-Hem, hematology intensive care unit. Numbers following ICU indicate different ICUs.

Amplification of genes in the PaLoc.

tcdA and tcdB gene sequences were amplified as described previously (3, 9). The presence of the genes tcdD, tcdE, and tcdC as well as cdu-2 and cdd-3 was determined by using the primers and conditions described by Braun et al. (1). Table 2 shows the primers used to amplify each of the genes in the pathogenicity locus (PaLoc) and the expected sizes of the amplified products.

TABLE 2.

Primer pairs used for amplification of PaLoc genes and size of amplicon

| Primer pair | Sequence (5′→3′) | Gene | Expected size (bp) |

|---|---|---|---|

| YT-28 | GCATGATAAGGCAACTTCAGTGG | tcdA | 602 |

| YT-29 | GAGTAAGTTCCTCCTGCTCCATCAA | ||

| YT-17 | GGTGGAGCTGCTTCATTGGAGAG | tcdB | 399 |

| YT-18 | GTGTAACCTACTTTCATAACACCA | ||

| Tim 2 | GCACCTCATCACCATCTTCAA | tcdC | 345 |

| Struppi 2 | TGAAGACCATGAGGAGGTCAT | ||

| Tim 3 | AAAAGCGATGCTATTATAGTCAAA | tcdD | 300 |

| Struppi 3 | CCTTATTAACAGCTTGTCTAGAT | ||

| Tim 1 | GTTTAAGTGCAATAAAAAGTCGTA | tcdE | 262 |

| Struppi 1 | GGTAATCCACATAAGCACATATT | ||

| Tim 5 | CCACAGATGCTTTTAGCAGGAA | cdu2 | 162 |

| Struppi 5 | TCCAATCACTGCTCCAGCTAT | ||

| Tim 6 | TCCAATATAATAAATTAGCATTCCA | cdd3 | 622 |

| Struppi 6 | GGCTATTACACGTAATCCAGATA |

Genotyping by AP-PCR.

Arbitrarily-primed PCR (AP-PCR) was performed as described previously with the arbitrary primer T-7 (5, 10).

Detection of amplified products.

Amplicons from the genes in the PaLoc were visualized by running 9 μl of the PCR product in a 2% agarose gel (Life Technologies, GIBCO, BRL, Grand Island, N.Y.) in Tris-borate-EDTA buffer. DNA banding patterns from AP-PCR amplifications were visualized by running 12 μl of the amplification product in a 1.5% agarose gel in Tris-borate-EDTA buffer. In all gels, a 123-bp DNA ladder was included as the size marker. Gels were run at a constant 110 V for 80 min and then stained in an ethidium bromide solution (0.5 μg/ml) for 20 min, destained for 20 min, and photographed under UV light with a Polaroid Land camera. In the case of the AP-PCR amplification, DNA banding patterns from individual strains were compared visually by running the amplification products on the same gel and the degree of homology was determined by Dice coefficient analysis using the Molecular Analyst fingerprinting software (Bio-Rad, Hercules, Calif.).

Detection of toxin A by the TOX A enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay.

Production of toxin A in the patient isolates was detected by the C. difficile TOX A TEST kit (TechLab, Blacksburg, Va.) as instructed by the manufacturer.

RESULTS

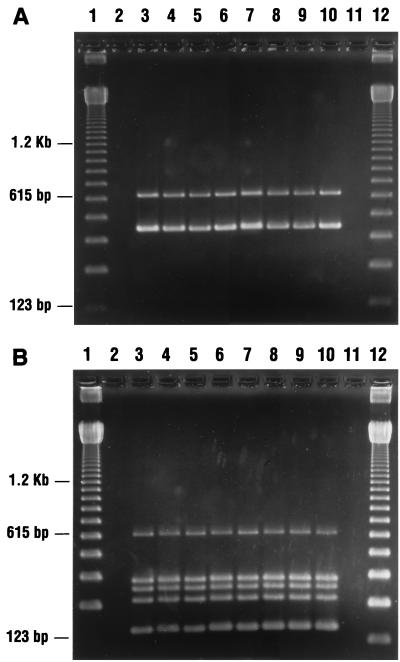

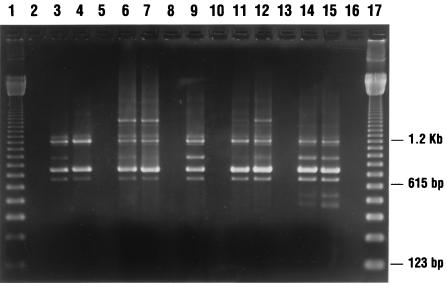

C. difficile was isolated from 9 of 509 (1.8%) patients with diarrhea and from 28 of 1,300 (2.1%) sites cultured at the Minsk General Hospitals. Most environmental isolates were recovered from bedpans in the intensive care units. All the isolates analyzed in this study had the toxin A and B gene sequences targeted by our primers, as well as the genes tcdC, tcdD, and tcdE, which constitute the PaLoc (Fig. 1). A cytotoxin assay was not performed with stools from the patients; however, all of the patient isolates produced toxin A as determined by the TOX A enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay. Five major AP-PCR groups were identified among these isolates (Table 1; Fig. 2). Isolates from patients grouped into three AP-PCR types, two of which were also found in the hospital environment (types I and II). AP-PCR type I was the predominant type isolated from the patients; type III was unique to patient isolates. The isolates recovered from the environment constituted a predominantly homogenous group classified into four AP-PCR types, with groups I and IV accounting for about 83% of all the environmental isolates (Table 1; Fig. 2). Several types were found in different units and also throughout the units. Although AP-PCR types I and II were identified in both patient and environmental isolates, there was no epidemiological association between them. The environmental locations where these isolates were recovered and the locations where the patients were housed were different.

FIG. 1.

(A) Ethidium bromide-stained 2% agarose gel of PCR products of DNA from C. difficile isolates in Belarus. Lanes 1 and 12, 123-bp DNA marker ladder; lanes 3 to 10, DNA from C. difficile isolated from patients (lanes 3 to 6) and the environment (lanes 7 to 10) and amplified with primers targeting toxin A and B genes. (B) Ethidium bromide-stained 2% agarose gel of PCR products of DNA from C. difficile isolates in Belarus. Lanes 1 and 12, 123-bp DNA marker ladder; lanes 3 to 10, DNA from C. difficile isolates from patients (lanes 3 to 6) and the environment (lanes 7 to 10) and amplified with primers targeting genes tcdC, tcdD, tcdE, cdu-2, and cdd-3 See Table 2.

FIG. 2.

Genotyping of C. difficile isolates with the arbitrary primer T-7. Lanes 1 and 17, 123-bp DNA marker ladder; lanes 3 and 4, AP-PCR type I; lanes 6 and 7, AP-PCR type II; lane 9, AP-PCR type III; lanes 11 and 12, AP-PCR type IV; lanes 14 and 15, AP-PCR type IVa; lanes 2, 5, 8, 10, 13, and 16, blank lanes.

DISCUSSION

Studies on C. difficile-associated diarrhea (CDAD) in Eastern Europe have been limited, probably due to the lack of technology and facilities for culturing anaerobic pathogens. C. difficile has been isolated from the feces of adults and children in Polish hospitals, where it is a significant etiologic agent of hospital-acquired diarrhea (4, 5). Meisel-Mikolacjzyk et al. have reported new serotypes, not identified in the serogroups of Delmee et al., among strains of C. difficile isolated in Poland (7). Aside from these reports, the significance of CDAD in Eastern European countries remains unclear. Because C. difficile is not one of the commonly tested pathogens in diarrheal diseases in Belarus, we undertook this study to determine the prevalence of C. difficile in the hospital environments and in patients with diarrhea. Despite the fact that toxigenic C. difficile was isolated from only 1.8% of the patients analyzed, the increase in widespread and indiscriminate use of antibiotics in Eastern Europe raises the concern of CDAD becoming a significant cause of hospital-acquired diarrhea in this country.

The presence of toxin A or B in the stools of patients was not tested; however, toxin A production was demonstrated in all the strains isolated from patients with diarrhea. The production of toxin A and the presence of all the genes in the PaLoc in the clinical isolates strongly suggest that these isolates are capable of causing clinical symptoms. The recovery of toxigenic C. difficile from the hospital environment and the identification of two strain types common to patients and the environment suggest that the environment may be a reservoir and serve as a source of acquisition of toxigenic C. difficile. Sixty-two percent of the patient isolates were identified as type I, which also represented 35.4% of the environmental isolates. None of the patients were in the locations from which environmental isolates were recovered, with the exception of patient 8. No correlation was found between isolate 8 and those recovered from the environment in that unit, raising the possibility of transmission by medical personnel.

It is interesting that the strains analyzed in this study constituted a mostly homogenous group, that all were toxigenic, and that the most distant types were 68% related as determined by Dice coefficient analysis. The degree of relatedness observed in these isolates may indicate that specific strain types are common to certain geographical areas. Further studies are in progress to obtain a better understanding of the epidemiology of CDAD in Belarus.

REFERENCES

- 1.Braun V, Hundsberger T, Leukel P, Sauerborn M, von Eichel-Streiber C. Definition of the single integration site of the pathogenicity locus in Clostridium difficile. Gene. 1996;181:29–38. doi: 10.1016/s0378-1119(96)00398-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.George W L, Sutter V L, Citron D, Finegold S M. Selective and differential medium for the isolation of Clostridium difficile. J Clin Microbiol. 1979;9:214–219. doi: 10.1128/jcm.9.2.214-219.1979. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gumerlock P H, Tang Y J, Weiss J B, Silva J., Jr Specific detection of Clostridium difficile in stool specimens. J Clin Microbiol. 1993;31:507–511. doi: 10.1128/jcm.31.3.507-511.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Martirosian G, Polanski J, Szubert A, Meisel-Mikolajczyk F. Clostridium difficile in a department of surgery. Mater Med Pol. 1993;25:145–147. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Meisel-Mikolajczyk F, Martirosian G, Marianowski L, Dworczynska M, Cwyl-Zembruzuska L. Clostridium difficile in a maternity hospital. J Feto-Maternal Med. 1992;5:173–177. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Meisel-Mikolajczyk F, Martirosian G, Tang Y J, Silva J., Jr Genotyping of Clostridium difficile isolates from a hospital in Warsaw: a preliminary study. Int J Infect Dis. 1997;2:88–90. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Meisel-Mikolajczyk F, Sokol B. New Clostridium difficile serotypes in Poland. Eur J Epidemiol. 1991;7:434–436. doi: 10.1007/BF00145011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Silva J, Jr, Tang Y J, Gumerlock P H. Genotyping of Clostridium difficile isolates. J Infect Dis. 1994;169:661–664. doi: 10.1093/infdis/169.3.661. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Tang Y J, Gumerlock P H, Weiss J B, Silva J., Jr Specific detection of Clostridium difficile toxin A gene sequences in clinical isolates. Mol Cell Probes. 1994;8:463–467. doi: 10.1006/mcpr.1994.1066. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Tang Y J, Houston S T, Gumerlock P H, Mulligan M E, Gerding D N, Johnson S, Fekety F R, Silva J., Jr Comparison of arbitrarily primed PCR with restriction endonuclease and immunoblot analyses for typing Clostridium difficile isolates. J Clin Microbiol. 1995;33:3169–3173. doi: 10.1128/jcm.33.12.3169-3173.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]