Abstract

Fatty acids are energy substrates and cell components which participate in regulating signal transduction, transcription factor activity and secretion of bioactive lipid mediators. The acyl-CoA synthetases (ACSs) family containing 26 family members exhibits tissue-specific distribution, distinct fatty acid substrate preferences and diverse biological functions. Increasing evidence indicates that dysregulation of fatty acid metabolism in the liver-gut axis, designated as the bidirectional relationship between the gut, microbiome and liver, is closely associated with a range of human diseases including metabolic disorders, inflammatory disease and carcinoma in the gastrointestinal tract and liver. In this review, we depict the role of ACSs in fatty acid metabolism, possible molecular mechanisms through which they exert functions, and their involvement in hepatocellular and colorectal carcinoma, with particular attention paid to long-chain fatty acids and small-chain fatty acids. Additionally, the liver-gut communication and the liver and gut intersection with the microbiome as well as diseases related to microbiota imbalance in the liver-gut axis are addressed. Moreover, the development of potentially therapeutic small molecules, proteins and compounds targeting ACSs in cancer treatment is summarized.

Keywords: Long-chain fatty acids, Short-chain fatty acids, Acyl-CoA synthetases, Microbiota, Liver-gut axis

Core Tip: To understand the role of acyl-CoA synthetases (ACSs) in the fatty acid metabolism, it is necessary to explore the biological function, gene interactions/ regulations and signal pathways in physiological and pathological conditions. Growing evidence demonstrates that the control of microbial balance plays an important role in maintaining homeostasis and normal functions of the liver-gut axis, and the bidirectional communication in turn affects microbial communities. As novel therapeutic targets, miRNAs are receiving more and more attention, together with other compounds targeting ACSs.

INTRODUCTION

Lipids, one of three main nutrients, are mainly composed of fatty acids (FAs), triglycerides (TGs), phospholipid and cholesterol. Lipid metabolites are involved in various biological functions and physiological processes, ranging from energy storage and degradation and structural composition to molecule signaling as well as signal transduction cascade[1].

The liver-gut axis plays a critical role in the homeostasis of lipid metabolism in the human body during the feed-fast cycle. Free FAs are absorbed by enterocyte and intestine-derived products released into portal blood which is directed to the liver; in turn, the liver responds by secreting bile acids (BAs) to the intestine via the biliary tract. BAs are transported back to the liver via enterohepatic circulation. Since the Volta group identified the important role of microorganisms in the liver-gut axis for the first time[2], a number of studies have confirmed that gut microbiota, described as an invisible metabolic ‘organ’, has a tight and coordinated connection with the gut and liver[3,4]. The intestinal mucosal barrier either acts as a physical barrier or lives in symbiosis with microbiota. Once the balance of symbiosis is disrupted, microbiota responds to this imbalance, microbiota metabolites (short-chain fatty acids, SCFAs) are modified and circulated into the liver. Aberrant lipid metabolism in the liver-gut axis has been linked with intestinal bowel diseases and diverse liver diseases[5].

Around 95% of dietary lipids absorbed are TGs, mainly composed of long-chain fatty acids (LCFAs)[6]. Fatty acid metabolism takes place mainly in intestinal enterocytes and hepatocytes, further assisted by adipocytes and other cell types. To become further involved in both anabolic and catabolic pathways, FAs must be taken up and activated by thioesterification. This ATP-mediated coupling reaction of FAs with coenzyme A is catalyzed by the enzymes called acyl-CoA synthetases (ACSs). ACSs are classified into five groups according to the fatty acid chain length: short-chain, medium-chain, bubblegum-chain, long-chain and very-long-chain acyl CoA synthetases (ACSVLs)[7]. ACSVLs as membrane channel proteins have been identified as a major enzyme responsible for LCFA uptake and activation[8]. Long-chain acyl-CoA synthetases (ACSLs) are responsible for the catalyzation of intracellular free LCFAs which are transported by other transport proteins, such as fatty acid translocase (CD36) and fatty acid binding proteins (FABPs)[9]. Short-chain acyl-CoA synthetases (ACSSs) are involved in the activation of microbiota-derived SCFAs, such as acetate and propionate[10] (Table 1).

Table 1.

miRNA and compounds targeting acyl-CoA synthetases

| Type | Name | Target | Mechanism | Ref. |

| miRNA | miR-205 | ACSL4/ACSL1 | Inhibition of ACSL4/ACSL1 in hepatocellular carcinoma | [155,171] |

| miR-211-5p | ACSL4 | Inhibition of ACSL4 in hepatocellular carcinoma | [172] | |

| miR-19b-1 | ACSL1/ACSL4/SCD1 | Inhibition of ACSL1/ACSL4/SCD1 axis in colorectal cancer | [173] | |

| miR-142-3p | ACSL1/ACSL4/SCD1 | Inhibition of ACSL1/ACSL4/SCD1 axis in colorectal cancer | [173,174] | |

| miR-34c | ACSL1 | Inhibition of ACSL1 and induction of liver fibrogenesis | [175] | |

| miR-497-5p | ACSL5 | Inhibition of ACSL5 in colon cancer | [170] | |

| Compounds | Triacsin C | ACSL1/ACSL3/ACSL4 and ACSL51 | Inhibition of ACSL1/ACSL3/ACSL4 and ACSL51 | [177,178] |

| Roglitazone Pioglitazone Troglitazone | ACSL4 | Inhibition of ACSL4 | [179-181] | |

| Lipofermata | FATP2 | Inhibition of FATP2 | [191,192] | |

| Grassofermata | FATP2 | Inhibition of FATP2 | [191,193,194] | |

| Ursodiol chenodiol | FATP5 | Inhibition of FATP5 in liver | [195] | |

| Fenofibrate | PPARα | Indirect activation of FATP in liver predominantly | [196,197] |

Triacsin C is also competitive inhibitor of ACSL5 when used in higher concentration.

In this review, we will summarize the functional role of ACSs in fatty acid metabolism, focusing on LCFAs and SCFAs, as well as potential therapeutic targets of ACSs. Furthermore, we will explore the influence of dietary diversity on microbiota and the microbial metabolites, and their bidirectional communication in the liver-gut axis.

FATTY ACID METABOLISM MEDIATED BY ACYL-COA SYNTHETASES IN THE LIVER-GUT AXIS

Circulation of fatty acids and bile acids in the liver-gut axis

Intestinal absorption of FAs is a multistep process that includes digestion, uptake and absorption and needs to cooperate with large numbers of enzymes secreted by series of organs in the gastrointestinal tract[11]. TGs are first released from a fatty diet after digestion with lingual and gastric lipase in the stomach, and released TGs are further hydrolyzed by pancreatic lipase to produce 2-monoacylglycerides and free FAs[12]. Sequentially those digested FAs mix with BAs and emulsify to form spherical water-soluble droplets, called micelles (MCs). With intestinal peristalsis, MCs are transported to the small intestinal lumen and further translocated into the apical membrane of enterocytes.

In intestinal enterocytes, absorbed LCFAs experience a series of catabolic metabolisms for energy supply for massive biological activities, and anabolic metabolism to reconstitute lipids. Newly synthesized lipids are incorporated into transport vehicles, chylomicrons (CMs), that are later liberated from enterocytes, and then transported to the liver through the hepatic portal vein. The liver is the major processing factory of FAs and regulates and balances lipid homeostasis systemically in the liver-gut axis. Fatty acid uptake and metabolism occur in hepatocytes. During feeding, hepatocytes take up the influx of FAs and get rid of FAs via β-oxidation to produce energy, and reformed TGs integrated into CMs partition into two pathways: (1) Secreted into bloodstream; and (2) transported and stored in adipose tissue. During fasting or starvation, hepatocytes recycle TGs from lipid droplets and adipose tissue, and initiate de novo lipogenesis by using other energy sources in the liver, such as carbohydrates[13,14]. Therefore, the pool of FAs is always in dynamic equilibrium between dietary absorption in the enterocytes, process and lipogenesis in the liver and liver feedback regulation via BAs during the feed-fast cycle.

As previously mentioned, BAs are involved not only in facilitating MC formation, but also as signaling molecules and metabolic regulators of lipid/glucose metabolism, energy homeostasis and inflammation in the liver-gut axis[15]. It has been demonstrated that a higher level of BAs can be detected in the tissues of the liver-gut axis compared to peripheral blood[16]. Primary BAs are synthesized in the hepatocytes and secreted into the small intestine; most of them are reabsorbed in the ileum. A small number of unabsorbed BAs are taken up by microbiota and metabolized into secondary BAs[17]. In enterocytes BAs are reabsorbed through the apical sodium-dependent BA transporter (ASBT), carried by the intestinal bile acid-binding protein (FABP6) and released into portal blood via heterodimeric transporter OSTα/OSTβ. BA activation of the nuclear farnesoid X receptor (FXR) also upregulates FABP6, OSTα/OSTβ and fibroblast growth factor 19 (FGF19), which further inhibits BAs synthesis. In hepatocytes, the transport of BAs is mediated by sodium-taurocholate cotransporting polypeptide (NTCP) and organic anion transporters (OATPs). BAs acting as an activator of hepatic FXR regulate the expression of genes involved in bile acid transport and synthesis. This enterohepatic circulation of BAs plays a critical role in maintaining the BAs pool in the liver-gut axis[18,19].

Long-chain fatty acid transport to enterocytes and hepatocytes

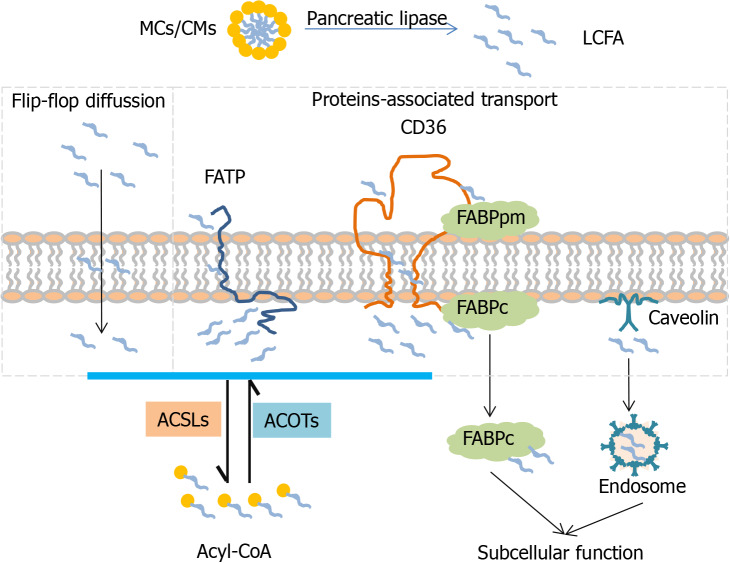

Free fatty acid uptake is requested across the phospholipid bilayer in the mammalian membrane. It is widely known that LCFAs can be taken up into cells via flip-flop diffusion with rate limiting[20,21]. High permeability of LCFA transport is mediated by several membrane-associated transport proteins including FA transport proteins (FATPs), FABPs, CD36 and caveolin (CAV)[9].

FATP1-6 (fatp in mice, also called ACSVL1-6) is a group of enzymatic proteins with double capabilities of transport and activation. FATP can trap and activate a broad range of LCFA and VLCFA to form acyl-CoA[9,22]. Different FATP family members have tissue-specific expression patterns[23]. In the intestine, FATP4 (ACSVL5) is strongly expressed in intestinal villi but not in crypts, which plays an important role in fatty acid absorption[24]. Fapt4-null mice display an embryonic lethality with a defective epidermal barrier. Fapt4 depletion alters the ceramide fatty acid composition significantly, especially in saturated VLCFA substitutes C26:0 and C26:0-OH[25]. FAPT5 (ACSVL6) mainly transports BAs but also LCFAs, is only expressed in the liver and particularly in the basal membrane of hepatocytes[8,26]. Fapt5 knockout mice showed this defective bile acid conjugation, indicating that Fapt5 is essential for fatty acid uptake by hepatocytes and maintenance of the lipid balance which further regulates body weight[27]. With the discovery of the topological structure of murine FAPT1 containing one transmembrane domain and a large cytoplasm domain[28], different mechanisms of FATP1 transporting exogenous FAs into cells have been proposed, one of which is vectorial transport or flipase function[29]. Moreover, BAs acting as a FATP5 antagonist dramatically decrease hepatic fatty acid uptake as well as liver triglyceride synthesis[30].

FABP 1-9 (fabp in mice) are a fatty acid binding protein superfamily that binds to FAs, cholesterol or other non-esterified FAs, facilitate fatty acid uptake and lipid metabolism[31]. FABP appears in two distinct forms depending on localization: one is peripheral membrane protein (FABPpm) and the other is intracellular/cytoplasmic protein (FABPc)[32]. Like FATP, different family members of FABPs exhibit organ-specific expression. FABP2 (Intestinal-FABP, I-FABP) encodes the intestinal form which is only expressed in the small intestine, and FABP-1(Liver-FABP, L-FABP) is only expressed in the liver[33]. I-FABP and L-FABP are all cytoplasmic proteins, but it is reported that they deliver FAs through different mechanisms of L-FABP in diffusion and I-FABP in collision[34]. L-fabp-null mice showed a reduced uptake of LCFAs as well as new biosynthesis for lipid storage or secretion, suggesting the important role of L-fabp in fatty acid esterification at endoplasmic reticulum (ER)[35]. Furthermore, L-FABP depletion suppresses lipid catabolism in mitochondria and downregulates the transcription of oxidative enzymes through inhibition of peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor (PPARα) transcriptor in the nucleus[36,37].

CD36, officially designated as scavenger receptor B2 (SR-B2), is a transmembrane glycoprotein which has a broad range of binding profiles including LCFAs, plasma lipoproteins, phospholipids, collagen[38]. CD36 whole body knockout mice showed significantly decreased fatty acid uptake in the heart and skeletal muscle[39]. In the intestine, CD36 is only detected in the duodenal and jejunal parts and plays a critical role for fatty acid and cholesterol uptake in the small intestine[40]. Although CD36 has a very low expression level in the liver, CD36 liver-specific knockout in the steatosis model indicated that CD36 deletion reduces lipid content and inflammation and improves insulin sensitivity[41].

CAV 1-3 (cav in mice) are intramembrane proteins which are responsible for caveolae formation. CAV1 as a cholesterol-binding protein is implicated in cholesterol trafficking and absorption[42]. However, Cav1 knockout mice did not show a compensatory mechanism to increase other family members, such as Cav2 and Cav3, and cholesterol absorption and sterol excretion were also not changed in the intestine[43]. Additionally, CAV1 also acts as a cytosolic intermediate form involved in lipogenesis and lipid body formation during liver regeneration[44].

It is widely recognized that several fatty acid transport proteins cooperate synergistically to accomplish the process of fatty acid transport (Figure 1). Due to the tissue-specific expression pattern, FATP4, FABPpm, FABP-I, CD36 are main types in the intestine and FATP5, FABPpm, FABP-L, CD36 are major types in the liver. Partial LCFAs are activated during transport via FATP. The rest of the LCFAs are grabbed by FABPpm and presented to CD36. Free cytosolic LCFAs is not only activated by ACSLs for esterification of acyl-CoA but also trapped by FABPc for subcellular function. Generated acyl-CoA as a raw material initiates the subsequent metabolism pathway to produce energy or synthesize diverse complex lipids. In addition, acyl-CoA can be deactivated to free FAs and CoA, and this process is mediated by acyl-CoA thioesterases (ACOTs). ACSLs and ACOTs are two critical enzymes helping to control the dynamic balance between acyl-CoA and free FAs.

Figure 1.

Mechanism of long-chain fatty acid transport across the lipid raft. LCFAs are taken up into cell in two different ways. One is passive transport by a flip-flop with rate limiting. The other is active transport, which is mediated with transport-associated proteins (FATPs, CD36, FABPs and Caveolin). FATPs with tissue-specific distribution integrating both transport and activation functions are responsible for LCFAs uptake. Free FAs trapped by the FABPpm present to CD36 and are transported into cells. Consequently released free FAs bind with FABPc and CAV channel into different organelles and are activated by different subcellular expression of ACSLs into acyl-CoA. In addition, acyl-CoA can be deactivated to free FA and CoA which is mediated by ACOTs. Liver-specific proteins: FATP5, FABP-L, ACSL1; Intestine-specific proteins: FATP4, FABP-I, ACSL5; ACSL: Acyl-CoA synthetase, ACOT: Acyl-CoA thioesterase; MCs: Micelles, CMs: Chylomicrons

Long-chain fatty acid activation in enterocytes and hepatocytes

As mentioned previously, most of the abundant dietary FAs are LCFAs so ACSLs are addressed in more details here. In humans and rodents there are five existing ACSL isoforms namely ACSL1, ACSL3, ACSL4, ACSL5 and ACSL6 (acsl in mice), each one coded by the different gene containing several splice variants[45]. Due to the differences in the 5’UTRs, the first coding exon, alternative coding exons and exchangeable motifs, different variants of each ACSL isoform are available[46]. The ACSL isoforms have two motifs: ATP binding and fatty acid binding[47]. The fatty acid binding tunnel located at the N-terminal domain has been linked to the substrate specificity of each ACSL isoform[48]. Since the N-terminal domain varies between the different ACSL isoforms, it contributes to the substrate preference of each family member and its different subcellular localization which is essential for vectorial acylation[49].

ACSL1 is predominantly located in the liver. Knockout of ACSL1 in the liver demonstrated a reduction in total ACSL activity of up to 50%, together with a decrease in the hepatic amount of acyl-CoA and a decreased level of oleic acid-derived TG[1,50]. Acsl1 deficient mice showed a 50% reduction in the amount of long-chain acyl-carnitines, leading to the conclusion that the loss of Acsl1 impaired partitioning of its products into TG synthesis and oxidation pathways[1]. Due to its both endoplasmic and mitochondrial localization, ACSL1 directs its metabolites to both the anabolic (TG synthesis ) and catabolic (β-oxidation) pathway[1].

ACSL3 Localization is linked to the lipid droplets and ER in the liver and other tissue. The increase in fatty acid uptake causes a transition of ACSL3 from ER to the lipid droplets, suggesting its role in neutral lipid synthesis[1]. Knockdown of ACSL3 reduced the activity of transcription factors including PPARγ, ChREBP, SREBP1C and Liver X receptor and their target genes involved in hepatic lipogenesis[1]. ACSL3 activates FAs incorporated into phospholipids, which are used for very-low density lipoprotein (VLDL) production[50]. As revealed by Yan et al, ACSL3 knockdown decreased the level of VLDL in hepatic cells[50]. Besides its role in the activation of FAs, overexpression of ACSL3 was found to be able to induce cellular fatty acid uptake[51].

ACSL4 is mostly expressed in adrenal glands and steroid-producing organs[52,53]. The role of ACSL4 is related to the activation of polyunsaturated FAs in steroidogenic tissue. ACSL4 has a preference for the arachidonic acid which is involved in the eicosanoid synthesis.

The nuclear-coded ACSL5 is prominent in both the mitochondria and ER of the intestinal mucosa and liver[50]. Highest expression was detected in the jejunum and ACSL5 was assumed to be involved in dietary fatty acid absorption. However, studies in acsl5 null mice showed no alteration in dietary fatty acid absorption but a significant decrease in total ACSL activity[1]. In the liver, ACSL5 activates LCFAs mostly of C18 carbon atoms, which are further incorporated into TGs, phospholipids and cholesterol esters. According to previous reports, ACSL5 plays a role in the metabolism of dietary FAs, but not in de novo synthetized ones[50,54,55]. Since ACSL5 is localized on the mitochondrial outer membrane, the activity was initially attributed to β-oxidation. Some studies with ectopic expression of ACSL5 failed to prove this, but the increased synthesis of TGs and diglycerides was observed in the liver[54]. ACSL5 is a dominant activator of dietary LCFAs and displayed an 80% lower activity in total acsl of the jejunum in acsl5 knockout mice[56]. ACSL5 is strongly expressed by enterocytes in an ascending gradient along the crypt-villus axis with the highest expression level at the villus tip; however, nuclear β-catenin, a hallmark of Wnt activation, is expressed in a descending gradient along the crypt-villus axis[57], suggesting an interplay between ACSL5 and Wnt activity during enterocyte differentiation and maturation[58].

ACSL6 is highly expressed in the brain where it plays a role in phospholipid synthesis during neurite outgrowth. ACSL expression is controlled by the level of intracellular FAs in physiological conditions[1].

Short-chain fatty acid transport and activation in enterocytes and hepatocytes

Microbiota-derived SCFAs cross the lipid membrane via different mechanisms: non-ionized diffusion, Na+/H+-dependent gradient exchange[59,60]. Intracellular SCFAs can shuttle between cytosol, nucleus and mitochondria via a diffusion mechanism[10,60]. SCFA activation by ACSSs is the first step in utilizing the energy source. ACSS 1-3 (acss in mice) are encoded and designated in humans. ACSS1 and ACSS3 are localized at the mitochondria matrix, while ACSS2 is a nuclear-cytosolic enzyme. ACSS1 and ACSS2 activate acetate to thioester into acetyl-CoA, but ACSS3 favors propionate[10].

In humans, mitochondrial ACSS1 is most highly expressed in the brain, blood, testis and intestine, also to a certain level in the heart, muscle and kidney, but not in the liver or spleen[61]. In mice, ACSS1 is strongly expressed in the heart, kidney, skeletal muscle and brown adipose tissue, which all need high energy expenditure[62]. Acss1 knockout mice showed a remarkably decreased acetate oxidation in the whole body during fasting compared with the wild type, however, no histological changes were detected in multiple tissues including the intestine and liver[63]. ACSS3 displays the character of propionyl-CoA synthetase as well as the highest expression in the liver. Knockdown of ACSS3 in hepG2 significantly decreases the activity of propionyl-CoA synthetase. During fasting, ACSS3 is upregulated, which is probably linked to ketogenesis, and ACSS2 is downregulated[64].

ACSS2 is most highly expressed in the liver and kidney[64,65]. Moffet et al[10] introduced the concept that the expression of ACSS2 in different cell types is based on the different physiological conditions to utilize acetate. Therefore, the liver is supposed to be the main organ for processing acetate. With the feature of localization, ACSS2 catalyzes acetate into acetyl-CoA which is correlated with fatty acid biosynthesis in cytosol, and retains acetate released from histone in the nucleus[66]. Acss2-deficient mice with high-fat feeding can lighten fat deposition in the liver by regulating many genes involved in lipid metabolism, suggesting that Acss2 acts as a transcription regulator during lipogenesis[67].

The expression and localization pattern of ACSS 1-3 suggests that ACSS1 and ACSS3 are responsible for energy production by using acetate in the intestine and liver respectively. The majority of acetate is taken up by the liver, ACSS2 in cytoplasm is involved in lipogenesis and is distributed to other organs in ketone bodies through systemic circulation. Acetyl-CoA as a central metabolite can go into either energy production or lipid biosynthesis. ACSS1-3 plays a key role in regulating the level of acetyl-CoA in the nucleus, mitochondria and cytoplasm (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

The crosslink between acyl-CoA synthetases and short-chain fatty acids. In mitochondria, acetyl-CoA is generated either from fatty acid β-oxidation and glucose via pyruvate or SCFAs through ACSS1 and ACSS3; acetyl-CoA is directed into energy production through the TCA cycle and electron respiration chain, as well as reflux into cytosol via citrate and again synthesizes acetyl-CoA. In addition, excessive acetate and butyrate synthesize into ketone bodies and are released into cytosol. In cytosol, acetyl-CoA is produced from pyruvate which is from both glucose and propionate; the source of acetyl-CoA can be converted from butyrate and acetate via butyryl-CoA/acetate CoA-transferase and ACSS2 respectively; cytosolic ketone bodies can also either produce acetyl-CoA or enter the blood circulation in the whole body. On the other hand, acetyl-CoA is involved in cholesterol biosynthesis. In the nucleus, acetate synthesizes acetyl-CoA via ACSS2 which is responsible for chromosome stability through histone acylation regulation. Cyto: Cytoplasma; Mito: mitochondria; Nucl: Nucleus; TCA: tricarboxylic acid cycle.

MICROBIOTA UTILIZATION OF DIET, MICROBIOTA METABOLITES AND THE ROLE OF MICROBIOTA IN THE LIVER-GUT AXIS

Dietary structure shapes the composition of microbiota

Gut microbiota, a diverse microbial community with approximately 100 trillion microorganisms, is colonized in the gastrointestinal tract. In human adults, five families microbiota are mainly Firmicutes, Bacteroidetes, Actinobacteria, Proteobacteria and Verrucomicrobia, while phylum Firmicutes and Bacteroidetes make up approximately 80% of all species[68].

A high-fiber intake population has higher diversity microbiota and more SCFAs production than a high-calorie diet population, and two populations showed distinct diet favor microbiota[69]. Bacteroides and Prevotella are two dominant groups which are highly enriched in a high-protein/fat diet population and high-fiber population respectively[70,71]. Moreover, the composition of fecal microbiota varies by age, geography and lifestyle due to the behavior of microbiota dietary preferences[72]. The term microbiota-accessible carbohydrates (MACs) introduced by Sonnenburg et al refers to microbiota favorable-carbohydrates that cannot be digested by the host. Mice feeding on a long-term low-MACs diet display a remarkably reduced diversity of microflora containing mostly Bacteroildales and Clostridiales. Although the microbiota composition cannot be restored after refeeding with a high-MAC diet, it increases again mainly in Bacteroidales upon reintroduction of fecal microbiota[73].

SCFAs are metabolic end-products from specialized bacteria utilizing with undigested dietary polysaccharides in human small intestine. The most abundant SCFAs in the intestine are acetate (C2), propionate (C3) and butyrate (C4). The phylum Bacteroidetes, the most abundant gram-negative bacteria with a high flexibility to adapt the environment, are associated with acetate production[74]. Phylum Bacteroidetes and Negativicutes (Akkermansia muciniphila, family Veillonellacear and phylum Firmicutes) are dominantly responsible for production of propionate by the succinate pathway, small bacterial genera from phylum Firmicutes have been identified to form propionate through the acrylate pathway, and distant Lachnospiraceae are known to produce propionate by utilizing the propanediol pathway[75]. Several species from families Lachnospiraceae, Ruminococcaceae and Erysipelotrichacear (Phylum Firmicutes) produce butyrate via butyrate kinase route and butyryl-CoA:acetate CoA-transferase route[76]. Diverse composition of microbiota has distinct SCFAs profiles, and additionally, SCFAs-metabolic network is a cross-feeding microbial system between different bacterial species[77].

In all, a high intake of MACs is pivotal in shaping the diversity and composition of microbiota. Diverse microbiota-generated SCFAs reversely influence the microbial communities and further act as a mediator is strongly involved in host-microbiota cross-talk.

Utilization of long-chain fatty acid in microbiota

Microbiota can also employ luminal unabsorbed LCFAs directly as energy source once there is a fermentable fiber deficiency[78]. LCFAs cross the cellular envelope in bacteria and yeast, unlike in mammalian cells. In bacteria, FadL transports exogenous LCFAs from outer membrane to periplasm, FadD (role as ACSLs) extracts LCFAs into the cytoplasmic membrane and activates to form acyl-CoA. In yeast, Fat1p and Faa1p/Faa4p are required for LCFAs transport and activation respectively[29]. Moreover, LCFAs can also permeate the bilayers via the TolC channel in E. coli[79,80].

Subsequently activated acyl-CoA is degraded to acetyl-CoA via β-oxidation. Acetyl-CoA is located at the crossroads of central metabolism[81]. During bacterial overgrowth, acetyl-CoA is not only necessary only for energy generation via entering citric acid cycle and respiratory chain, but also synthesizes new cell material via the glyoxylate cycle. Moreover, the conversion from acetyl-CoA to acetate and ethanol takes place through anaerobic fermentation due to oxidant deficiency[82].

In addition to being a nutrient, LCFAs serve as an environmental factor which guides a series of gram-negative bacteria to colonize and invade intestinal lumen by repressing the expression of the strain-specific pathogenicity island. A pathogenicity island has been reported as a transcriptional activator which is mandatory for tissue invasion, such as Salmonella PI1/hilA[80], the Vibril cholera AraC/Xyls family ToxT[83], Yersinia enterocolitica VirF and enterotoxigenic E. coli Rns[84].

Microbiota-derived short-chain fatty acids

Microbiota-derived SCFAs make up almost all SCFAs due to the lower level of SCFAs in human blood[85]. SCFAs as the basic substance sources play an important role in regulating lipid metabolism as well as maintaining the host energy homeostasis. In part, SCFAs can be absorbed directly as an energy source by enterocytes or transported to the liver via the portal vein; in part, SCFAs are reassigned by the liver and released into bloodstream for the systemic circulation through the whole body[10,86]. SCFAs are mainly composed of acetate, butyrate and propionate which comprise 60%, 20% and 20% respectively[87]. SCFAs are transported and taken up into cells via non-ionized and ionized diffusion. The liver-gut axis plays a key role in the absorption, metabolism and systemic circulation of SCFAs[88].

Acetate, which is produced from pyruvate via acetyl-CoA and the wood-Ljungdahl pathway in microbiota, is the most abundant SCFA. Acetate is activated by ACSS1-3 to form acetyl-CoA and metabolized for energy production. However, the majority of acetate reaches and is processed in the liver. In cytosol, acetyl-CoA can synthesize cholesterol[89]; in the nucleus, acetate and acetyl-CoA are involved in regulating DNA histone acetylation and deacetylation[90]; in mitochondria, acetyl-CoA can be either for energy supply or ketogenesis in case of glucose deficiency, ketone bodies enter blood circulation for peripheral tissues usages[91]. Moreover, acetate can cross the blood-brain barrier freely and is an energy source for glial cells[92]. Acetate has a direct role in appetite regulation. Acetate is metabolized to generate more adenosine triphosphate, and inhibits adenosine monophosphate-active protein kinase (AMPK), as well as upregulating anorectic neuropeptide POMC and downregulating orexigenic neuropeptide AgRP[93].

Of the SCFAs which are mainly composed of acetate, butyrate and propionate, butyrate is the most widely studied. Butyrate is generated through the butyrate kinase or butyryl-CoA/acetate CoA-transferase route. Butyrate is a major SCFA in the large intestine. In enterocytes, the majority of butyrate is converted into acetyl-CoA that further participates in catabolism for host energy supply[94]; a small amount of butyrate is delivered to the liver and incorporated into ketone bodies (β-hydroxybutyrate) in mitochondrial for ATP production[95]. Butyrate plays a key role in maturating the intestinal barrier function in premature infants[96]. In vivo studies showed that butyrate administration has favorable therapeutic effects on normal colonic health in a safe dose[86]. In a mouse model with globin chain synthesis disorder, the application of a high dose of butyrate resulted in striking neuropathological changes and multiorgan system failure due to harmful systemic concentrations[97]. Therefore, mechanisms underlying the dosage-dependent effects on the intestinal barrier are controversial, but reasonable. A low dose promotes restitution of intestinal epithelial lumen and a high dose impairs the intestinal barrier function with regulation of permeability by inducing apoptosis[98]. The selective paracellular permeability is determined by junction proteins including tight junction, adherence junction and desmosomes[99]. Excessive SCFA accumulation downregulates the expression of junction protein and further impairs the integrity of the membrane, leading to a leaky gut[100]. Moreover, increased intestinal permeability has been linked to inflammatory bowel disease[101].

Propionate is produced via the succinate, acrylate and propanediol pathway in microbiota. Propionate is activated by ACSS3 in mitochondria of hepatocytes. The concentration of dietary propionate regulates the balance between lipid and glucose metabolism[102]. Propionate reduces cancer cell proliferation through activation of G-protein-coupled receptors 43 GPR43) in mice liver[103].

In view of the biosynthesis of SCFAs, acetate, butyrate and propionate have crosslinks through acetyl-CoA, pyruvate, oxaloacetate, some of which can be converted between them to meet the physiological need of microbiota[104]. SCFAs as key microbiota metabolites are closely correlated with host health and disease conditions through regulation of diverse physiological processes. Two major signaling pathways related to SCFAs including G-protein-coupled receptors (GPCRs) and histone deacetylases have been characterized[105]. GPCRs, also named free fatty acid receptors (FFAR) are activated by SCFAs. Two SCFA receptors, GPR41 (FFAR3) and GPR43 (FFAR2) have been reported. FFAR2 has preference to acetate and propionate, and FFAR3 has a specificity in butyrate[106]. FFAR2 is expressed along the entire gastrointestinal tract. FFAR2 can be upregulated by propionate during adipocyte differentiation[107]. In addition, FFAR2 activated by SCFAs releases glucagon-like peptide 1(GLP-1) and peptide YY (PYY) in enteroendocrine L cells, GLP-1 and PYY, are involved in gut motility, glucose tolerance and regulation of appetite[108]. Moreover, Butyrate plays a role in anti-inflammation through inhibition of pro-inflammatory mediators/adipokines, adhesion molecules, metalloproteinase production as well as inflammatory signaling pathways (NFκB, MAPKinase, AMPK-α, and PI3K/Akt). However, the anti-inflammatory activity of butyrate was eliminated by FFRA3 knockdown[109]. Supplementation of SCFAs significantly improved hepatic metabolic actiity in FFAR3-dificient mice, but not FFAR-2 deficient mice[110].

SCFAs are also considered a promising supplementary treatment for active intestinal bowel disease[111]. Moreover, SCFAs, as inhibitors of histone deacetylases, show potential anti-inflammatory activity[112,113]. It is demonstrated that three SCFAs alone or in combination protect the intestinal barrier via stimulation of tight junction formation and repression of NLRP3 inflammasome and autophagy in the colon cancer cell model[114]. Apart from this, a high-fiber intake, fecal microbiota transplant, prebiotics and probiotics are suggested to have a beneficial effect on colonic health by increasing the level of SCFAs.

Microbiota-imbalance-related diseases in the liver-gut axis

Gut microbiota exert multifunction in maintaining the host homeostasis, including defensing against pathogens, affecting immune system, mediating digestion and metabolism, involving in insulin regulation and maintaining the intestinal epithelial cell renewal[115]. Gut microbiota interact with host through producing a serial of metabolites, particularly SCFAs. Imbalance in diversity and composition as well as alterations in the function of gut microbiota is associated with the pathogenesis of diverse gastrointestinal tract diseases, such as small intestinal bacterial overgrowth (SIBO), intestinal bowel disease (IBD), and a serial of liver diseases[116].

SIBO takes place in short bowel syndrome (SBS) and causes variable signs and symptoms resulting in nutrient malabsorption[117]. SIBO is characterized with the small intestinal excessive numbers and types of bacteria overgrowth exceeding 105 organisms/mL, which are mainly colonic type with predominantly gram-negative aerobic species (Streptococcus, Escherichia coli, staphylococcus) and anaerobic species (Lactobacillus, bacteroides, clostridium and veillonella)[118]. Enterotoxins expressing in the outer membrane of germ-negative species can damage the intestinal mucosa barrier by stimulation of fluid secretion in enterocytes, and further affect the absorptive function[119]. SIBO is associated with irritable bowel syndrome (IBS), celiac disease (CD) as well as IBD[120], and also involved in the development of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease[121].

IBD occurs due to the imbalance between the host immune system and gut microbiota in digestive tract and is becoming an increasing health problem. Crohn’s disease and ulcerative colitis are the two prevailing types. The worldwide epidemiologic data shows that the higher incidence and prevalence of IBD is associated with industrialization[122]. Differences in dietary habits highly influence the composition of microbiota; a high-fat diet induces microbiota dysbiosis which alters the intestinal permeability[123].

Additionally, the disruption of bacterial colonization with dysbiosis and an exaggerated inflammatory response has been linked with the pathological process of necrotizing enterocolitis (NEC) in preterm infants[124]. In NEC cases, an increased proportion of Proteobacteria and Actinobacteria, a decreased numbers of Bifidobacteria and Bacteroidetes were detected before NEC diagnosis. Moreover, a type of bacteria related to Klebsiella pneumoniae has been strongly correlated with the NEC development later stage[125].

Although the mechanism involved in diverse gastrointestinal tract diseases is still not completely understood, an impaired intestinal mucosal barrier is common feature among them. In addition, Paneth cells located in the crypts of the small intestine are very important for providing a sterile inner mucus layer and maintaining mucosal barrier integrity against microbiota by secreting antibiotic peptides containing α-defensin, angiogenin, lysozyme and lectins[126]. α-defensin 5/6 are the most abundant components. α-defensin 5 can be digested into fragments which exert specific antibiotic activity[127]. However, α-defensin 6 prevents invasion by bacterial pathogens through self-assembly to form fibrils and nanonets[128]. Diminished expression of Paneth cell defensins regulated by the Wnt factor is associated with Crohn’s disease (also called Paneth’s disease)[129,130]. Paneth-cell-deficient mice showed a dysbiosis in favor of an E. coli expansion and further weakening of the intestinal mucosal barrier with a visceral hypersensitivity[131]. Moreover, active Crohn’s disease is accompanied by bile acid malabsorption due to altered expression of the major bile acid transporter[132].

As a consequence of intestinal mucosal barrier disruption, microbial/pathogen-associated molecular patterns (MAMPs/PAMPs) pass through lumen and mucosa to induce the inflammatory signaling nuclear factor kappa B (NFκB) via toll-like receptors (TLRs) and nod-like receptors (NLRs). Activation of this signaling induces the release of cytokines and chemokines into portal circulation[133,134].

Both bacterial components and metabolites reach the liver via the portal vein to induce hepatocytes damage. Additionally if dysbiosis occurs, secondary BAs including deoxycholic and lithocholic acid, which are toxic for both intestine and liver, are produced more than usual in microbiota[135]. Hepatocytes are damaged due a high level of secondary BAs, bacterial components and metabolites. High lipid peroxides and PAMPs derived from damaged hepatocytes induce liver microphage activation and initiate an immune response through NFκB, p-38/c-Jun-N-terminal kinase, TGF-β1 and other inflammation cytokines[136]. A macrophage-mediated immune response is a major player in liver fibrogenesis. Chronic liver injury leads to hepatic stellate cells to transition into myofibroblast-like cells which produce an extracellular matrix and further contribute to the progression of fibrosis[137,138]. Moreover, chronic liver inflammation is significantly involved in the pathogenesis of liver fibrosis/cirrhosis and probably contributes to carcinogenesis.

POTENTIAL THERAPEUTIC APPLICATION TARGETING ACYL-COA SYNTHETASES

Long-chain acyl-CoA synthetases and cancer

Alteration in a fatty acid metabolism with a higher fatty acid synthesis and lipid deposition is a major player in the pathogenesis of metabolic disorders and cancer[139]. Deregulation of metabolism is known as a hallmark of cancer[140]. The Warburg effect, one of the hallmarks of cancer, first introduced by Otto Warburg, has been used to describe the deregulated metabolism of cancer cells characterized by increased conversion of glucose into lactate even in the presence of oxygen[141]. Many cancer cells are highly dependent on aerobic glycolysis for their growth and division[142]. Recently, several studies have shown that some cancers, including colon cancer, rather synthetize ATP by oxidative phosphorylation, which has been called the reverse Warburg effect[143-146]. In addition to previously reported abnormalities of glucose and glutamine metabolism in cancers, abnormal lipid metabolism was also found in different cancer types[143]. Highly proliferative cancer cells are dependent not only on glucose but also on other metabolites including glutamine, serine and FAs[147-151]. It was reported that many cancer cells are characterized by an increased level of de novo fatty acid synthesis[152,153]. Upregulation of processes as fatty acid synthesis and FA release from lipid storage on the one hand, and downregulation of β-oxidation of FAs and their reesterification on the other, leads to an increased level of fatty acid in cancer cells. The fatty acid level was reported as a prognostic marker in several types of cancers including colorectal carcinoma (CRC)[7]. A high level of FA is considered a cancer biomarker and is associated with a worse prognosis and survival[7].

There is some evidence from mice with genetic inactivation of the Muc2 gene that in adenocarcinoma arising in both the small and large intestine, alterations of the glucose metabolism induce expression of genes linked to de novo lipogenesis[154]. However, a systematic comparative analysis of adenocarcinomas arising in different locations of the intestinal tract with lipidomics is not available at present. Increased expression of ACSL1 was reported in several cancers, including colon[155,156] and liver[157,158], related to a poor clinical outcome[159]; ACSL4 was also upregulated in multiple cancer types, including colon[155,160] and liver[161-163]. Poorer patient survival in stage II colon cancer was correlated with the expression of ACSL4 and expression of stearoyl CoA desaturase 1 (SCD1)[156]. Concomitant overexpression of ACSL1, ACSL4 and SCD1 was found to induce epithelial-mesenchymal transtion in colorectal cancer[155]. ACSL3 and ACSL4 were upregulated in hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC)[164]. Deregulated expression of both ACSL3 and ACSL4 is associated with disease and especially with cancer[7]. ACSL3 drives tumor growth by increasing both fatty acid β-oxidation[165] and arachidonic acid conversion into prostaglandin[166]. As previously reported, ACSL4 indirectly stabilizes c-Myc by acting on the ERK/FBW7 axis and driving oncogenesis via c-Myc-oncogenic signaling in HCC[167]. ACSL4 expression is highly linked to the cell sensitivity for ferroptosis, known as an iron-mediated non-apoptotic cell death[168]. Reported roles of ACSL4 include metabolic signaling resulting in drug resistance and the activation of intracellular, pro-oncogenic signaling pathways[139]. Impaired expression of ACSL5 is associated with coeliac disease and sporadic colorectal adenocarcinomas[169] and overexpression of ACSL5 induces apoptosis[170] and suppresses proliferation by inhibiting the activation of the Wnt/β-catenin signaling pathway in colon cancer[57].

ACSS1 and ACSS2 are overexpressed in HCC[171]. Both are key players in acetate metabolism which is shown to be highly taken up by several types of cancers, including liver. Gao et al[171] reported a role of acetate in epigenetic regulation (Histone acetylation) of a promoter region of FASN. Induction of lipid synthesis driven by increased FASN expression supports tumor cell survival and growth[171].

miRNAs targeting of long-chain acyl-CoA synthetases

Micro RNAs (miRNAs) are non-coding single stranded RNAs which regulate transcription of messenger RNA via binding to their 3’-untranslated region[172]. Cancer cells evolved a regulatory mechanism to control the mRNA stability of ACSLs by targeting their 3'-untranslated regions (3'UTR). For example, it was reported that miR-205 was decreased in liver cancer[173]. Negative correlation between miR-205 and ACSL4 expression was reported in human HCC patients[173]. The miR-205 targeting site is reported at the 3'UTR region of ACSL4-mRNA[173]. In addition, it is known that miR-205 binds to the 3'UTR of ACSL1 and induces its degradation[157]. The role of miR-211-5p as a tumor suppressor was reported in HCC[174]. This tumor-suppressive role was accomplished by downregulation of ACSL4 which is highly expressed in HCC[174]. miR-19b-1 showed an inhibitory effect on the ACSL1/ACSL4/SCD1 axis by downregulating the Wnt/β-catenin pathway[175]. ACSL/SCD increases GSK3β phosphorylation, activating Wnt signaling and EMT, therefore, downregulation of β-catenin signaling by miR-19b-1 can be beneficial in colon cancer[175]. miR-142-3p has been reported to target cancer stem cell markers, such as the Wnt target and LGR5 in colorectal cancer cells[176], in agreement with its action on the ACSL/SCD network cancer stem cell feature generation[175,176]. miR-34c was reported to be involved in hepatic fibrogenesis, miR-34c increases lipid droplet formation and hepatic stellate cell activation by downregulating ACSL1 in the liver[177]. miR-497-5p was reported to induce death in colon cancer cells by targeting ACSL5, suggesting its therapeutic potential in colon cancer[172].

Pharmacological targeting of long-chain acyl-CoA synthetases

Triacsin C, a fungal metabolite and a potent competitive inhibitor of ACSs activity[178,179], competes with FAs for the catalytic domain. It inhibits ACSL1, ACSL3 and ACSL4, and in higher concentration proves effective against ACSL5[179,180]. It is worth highlighting that triacsin C has a high toxicity (IC50) and consequently normal cells can be damaged[7].

Thiazolidinediones, also known as glitazones, are used for the therapy of diabetes II. Troglitazone and rosiglitazone are PPARγ agonists; interestingly they inhibit ACSL4 via PPARγ indirect mechanism[181,182]. Some of these drugs (Troglitazone, Ciglitazone) showed a protective effect against diabetes-promoted cancer[183].

Pharmacological targeting of very-long-chain acyl-CoA synthetases

FATP1 and FATP4 inhibitors were detected using high-throughput screening[184-186]. However, these compounds were not effective as revealed by in vivo studies. Screening compounds that specifically target domains involved in fatty acid transport, rather than the ACSL activity domain, might help to discover more effective compounds which could inhibit fatty acid transport. FATP2/ACSVL1, expressed mostly in the liver and intestine, acts as a transport protein and ACS[187]. FATP2 might be considered as an early marker for the development of overweight disorder after a high-fat diet[188]. A high-fat diet significantly upregulated fatp2 expression in the intestine of mice[188,189] It has a role in hepatic long-chain fatty acid uptake[190]. Due to its important role in fatty acid transport, FATP2 can be a promising pharmacological target in diseases which are characterized by an abnormal accumulation of intracellular FAs and lipids which may eventually result in irreversible hepatic cirrhosis[191,192]. Lipofermata and Grassofermata are selected FATP2 inhibitors which show specificity toward attenuating transport of LCFAs and VLCFAs. Lipofermata (5'-bromo-5-phenyl-spiro[3H-1,3,4-thiadiazole-2,3'-indoline]-2'-one) inhibits the function of FATP2 as a transport protein, without compromising its function as an ACS[193,194]. Grassofermata (2-benzyl-3-(4-chlorophenyl)-5-(4-nitrophenyl) pyrazolo[1,5-a] pyrimidin-7(4H)-one) suppresses palmitic acid mediated lipotoxicity[193,195,196]. Both of them reduce intestinal fat absorption of 13C labeled oleate[186]. In addition to its contribution to the development of metabolic liver diseases, FATP2 promotes the growth of cancer cells and induces their resistance to targeted therapies[190]. A study by Veglia et al[194] demonstrated that lipofermata abrogated the activity of polymorphonuclear myeloid-derived suppressor cells (PMN-MDSCs) and substantially delayed tumor progression in colon cancer cell line CT26 tumor-bearing mice. STAT5 signaling induced by granulocyte-macrophage colony stimulating factor (GM-CSF) upregulated the FATP2 in these cells. FATP2 overexpression in these PMN-MDSCs cells induced PGE2 synthesis and its immunosuppressive effect on CD8+ T cell[194]. Interestingly in this study, it was found that lipofermata elevated the therapeutical effect of immune checkpoint inhibitor therapy (anti-PD-1 and anti-CTLA-4) as well as macrophage targeted therapy (anti CSF-1R)[194].

FATP5 can be exclusively found in liver, at the basal plasma membrane of hepatocytes[197]. Both its location and role in long-chain fatty acid uptake make it an attractive target for treatment of metabolic disorders. Interestingly, screening of potential compounds revealed the potential of BAs including the primary BAs produced by the liver and the secondary BA secreted by intestinal bacteria (microbiota) to attenuate specifically FATP5 function without affecting FATP4[197]. The following BAs showed potential for FATP5 inhibition: chenodiol, primary BA, produced by the liver and ursodiol, secondary BA, which is metabolically produced by intestinal bacteria[197].

Experimental in vivo studies in rats showed induction of FATP mRNA expression, finding the highest upregulation in the liver. In the intestine, there was an increase in the FATP mRNA level but two times less than in the liver[198], suggesting that fenofibrates show specificity towards liver FATPs. Fibrates are known as PPARα activators, their hypolipidemic effect is accomplished via FATP activation, induction of β-oxidation and consequently reduction in triglyceride synthesis[198]. The indirect activation of FATP by the fenofibrate is mediated via PPARα[199].

Targeting of short-chain acyl-CoA synthetases

As reported by Bjorson et al[200], mitochondrial acetate appears to be the main metabolic energy source under hypoxia in HCC patients. Upregulation of ACSS1 Led to an enhanced level of mitochondrial acetate in HCC, which is associated with several metabolic alterations including decreased fatty acid oxidation, glutamine utilization, gluconeogenesis and increased glycolysis[200] This finding suggests a potential of ACSS1 as a target in cancer treatment. Indeed, the ACSS1 inhibitor showed a growth inhibitory effect on glioma[201].

CONCLUSION

LCFAs and SCFAs are the most abundant energy sources from dietary lipid intake and microbiota-derived fermentation products. Members of ACSs play a critical role in lipid metabolism, participating in fatty acid transport and activation. Abnormal expression of ACSs is closely associated with lipid metabolic disorders and carcinogenesis. Research on ACSs will shed further light on their biological functions and molecular mechanisms in fatty acid metabolism and eventually lead to the development of therapeutic drugs targeting ACSs in the treatment of human metabolic diseases.

Footnotes

Conflict-of-interest statement: Authors declare no conflict of interests for this article

Provenance and peer review: Invited article; Externally peer reviewed.

Peer-review started: February 25, 2021

First decision: June 15, 2021

Article in press: October 11, 2021

Specialty type: Gastroenterology and hepatology

Country/Territory of origin: Germany

Peer-review report’s scientific quality classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): B

Grade C (Good): 0

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

P-Reviewer: Kvit K S-Editor: Wang LL L-Editor: A P-Editor: Wang LL

Contributor Information

Yunxia Ma, Section Pathology, Institute of Forensic Medicine, Jena University Hospital, Friedrich Schiller University Jena, Jena 07747, Germany.

Miljana Nenkov, Section Pathology, Institute of Forensic Medicine, Jena University Hospital, Friedrich Schiller University Jena, Jena 07747, Germany.

Yuan Chen, Section Pathology, Institute of Forensic Medicine, Jena University Hospital, Friedrich Schiller University Jena, Jena 07747, Germany.

Adrian T Press, Department of Anesthesiology and Intensive Care Medicine and Center for Sepsis Control and Care, Jena University Hospital, Friedrich Schiller University Jena, Jena 07747, Germany.

Elke Kaemmerer, Department of Pediatrics, Jena University Hospital, Friedrich Schiller University Jena, Jena 07747, Germany.

Nikolaus Gassler, Section Pathology, Institute of Forensic Medicine, Jena University Hospital, Friedrich Schiller University Jena, Jena 07747, Germany. nikolaus.gassler@med.uni-jena.de.

References

- 1.Grevengoed TJ, Klett EL, Coleman RA. Acyl-CoA metabolism and partitioning. Annu Rev Nutr . 2014;34:1–30. doi: 10.1146/annurev-nutr-071813-105541. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Volta U, Bonazzi C, Bianchi FB, Baldoni AM, Zoli M, Pisi E. IgA antibodies to dietary antigens in liver cirrhosis. Ric Clin Lab . 1987;17:235–242. doi: 10.1007/BF02912537. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Guinane CM, Cotter PD. Role of the gut microbiota in health and chronic gastrointestinal disease: understanding a hidden metabolic organ. Therap Adv Gastroenterol . 2013;6:295–308. doi: 10.1177/1756283X13482996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Konturek PC, Harsch IA, Konturek K, Schink M, Konturek T, Neurath MF, Zopf Y. Gut⁻Liver Axis: How Do Gut Bacteria Influence the Liver? Med Sci (Basel) . 2018;6 doi: 10.3390/medsci6030079. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Park W. Gut microbiomes and their metabolites shape human and animal health. J Microbiol . 2018;56:151–153. doi: 10.1007/s12275-018-0577-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Niot I, Poirier H, Tran TT, Besnard P. Intestinal absorption of long-chain fatty acids: evidence and uncertainties. Prog Lipid Res . 2009;48:101–115. doi: 10.1016/j.plipres.2009.01.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Rossi Sebastiano M, Konstantinidou G. Targeting Long Chain Acyl-CoA Synthetases for Cancer Therapy. Int J Mol Sci . 2019;20 doi: 10.3390/ijms20153624. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Anderson CM, Stahl A. SLC27 fatty acid transport proteins. Mol Aspects Med . 2013;34:516–528. doi: 10.1016/j.mam.2012.07.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hamilton JA. New insights into the roles of proteins and lipids in membrane transport of fatty acids. Prostaglandins Leukot Essent Fatty Acids . 2007;77:355–361. doi: 10.1016/j.plefa.2007.10.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Moffett JR, Puthillathu N, Vengilote R, Jaworski DM, Namboodiri AM. Acetate Revisited: A Key Biomolecule at the Nexus of Metabolism, Epigenetics and Oncogenesis-Part 1: Acetyl-CoA, Acetogenesis and Acyl-CoA Short-Chain Synthetases. Front Physiol . 2020;11:580167. doi: 10.3389/fphys.2020.580167. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wang TY, Liu M, Portincasa P, Wang DQ. New insights into the molecular mechanism of intestinal fatty acid absorption. Eur J Clin Invest . 2013;43:1203–1223. doi: 10.1111/eci.12161. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lowe ME. The triglyceride lipases of the pancreas. J Lipid Res . 2002;43:2007–2016. doi: 10.1194/jlr.r200012-jlr200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Alves-Bezerra M, Cohen DE. Triglyceride Metabolism in the Liver. Compr Physiol . 2017;8:1–8. doi: 10.1002/cphy.c170012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hardie DG. Organismal carbohydrate and lipid homeostasis. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Biol . 2012;4 doi: 10.1101/cshperspect.a006031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Chiang JY. Bile acid metabolism and signaling. Compr Physiol . 2013;3:1191–1212. doi: 10.1002/cphy.c120023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Zhang YK, Guo GL, Klaassen CD. Diurnal variations of mouse plasma and hepatic bile acid concentrations as well as expression of biosynthetic enzymes and transporters. PLoS One . 2011;6:e16683. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0016683. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ramírez-Pérez O, Cruz-Ramón V, Chinchilla-López P, Méndez-Sánchez N. The Role of the Gut Microbiota in Bile Acid Metabolism. Ann Hepatol . 2017;16:s15–s20. doi: 10.5604/01.3001.0010.5494. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.de Aguiar Vallim TQ, Tarling EJ, Edwards PA. Pleiotropic roles of bile acids in metabolism. Cell Metab . 2013;17:657–669. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2013.03.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Li T, Chiang JY. Nuclear receptors in bile acid metabolism. Drug Metab Rev . 2013;45:145–155. doi: 10.3109/03602532.2012.740048. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Massey JB, Bick DH, Pownall HJ. Spontaneous transfer of monoacyl amphiphiles between lipid and protein surfaces. Biophys J . 1997;72:1732–1743. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(97)78819-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kamp F, Hamilton JA. How fatty acids of different chain length enter and leave cells by free diffusion. Prostaglandins Leukot Essent Fatty Acids . 2006;75:149–159. doi: 10.1016/j.plefa.2006.05.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Schaffer JE, Lodish HF. Expression cloning and characterization of a novel adipocyte long chain fatty acid transport protein. Cell . 1994;79:427–436. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(94)90252-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Pohl J, Ring A, Hermann T, Stremmel W. Role of FATP in parenchymal cell fatty acid uptake. Biochim Biophys Acta . 2004;1686:1–6. doi: 10.1016/j.bbalip.2004.06.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Stahl A, Hirsch DJ, Gimeno RE, Punreddy S, Ge P, Watson N, Patel S, Kotler M, Raimondi A, Tartaglia LA, Lodish HF. Identification of the major intestinal fatty acid transport protein. Mol Cell . 1999;4:299–308. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(00)80332-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Herrmann T, van der Hoeven F, Grone HJ, Stewart AF, Langbein L, Kaiser I, Liebisch G, Gosch I, Buchkremer F, Drobnik W, Schmitz G, Stremmel W. Mice with targeted disruption of the fatty acid transport protein 4 (Fatp 4, Slc27a4) gene show features of lethal restrictive dermopathy. J Cell Biol . 2003;161:1105–1115. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200207080. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Doege H, Baillie RA, Ortegon AM, Tsang B, Wu Q, Punreddy S, Hirsch D, Watson N, Gimeno RE, Stahl A. Targeted deletion of FATP5 reveals multiple functions in liver metabolism: alterations in hepatic lipid homeostasis. Gastroenterology . 2006;130:1245–1258. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2006.02.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hubbard B, Doege H, Punreddy S, Wu H, Huang X, Kaushik VK, Mozell RL, Byrnes JJ, Stricker-Krongrad A, Chou CJ, Tartaglia LA, Lodish HF, Stahl A, Gimeno RE. Mice deleted for fatty acid transport protein 5 have defective bile acid conjugation and are protected from obesity. Gastroenterology . 2006;130:1259–1269. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2006.02.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lewis SE, Listenberger LL, Ory DS, Schaffer JE. Membrane topology of the murine fatty acid transport protein 1. J Biol Chem . 2001;276:37042–37050. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M105556200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Black PN, DiRusso CC. Transmembrane movement of exogenous long-chain fatty acids: proteins, enzymes, and vectorial esterification. Microbiol Mol Biol Rev . 2003;67:454–472, table of contents. doi: 10.1128/MMBR.67.3.454-472.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Nie B, Park HM, Kazantzis M, Lin M, Henkin A, Ng S, Song S, Chen Y, Tran H, Lai R, Her C, Maher JJ, Forman BM, Stahl A. Specific bile acids inhibit hepatic fatty acid uptake in mice. Hepatology . 2012;56:1300–1310. doi: 10.1002/hep.25797. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Chmurzyńska A. The multigene family of fatty acid-binding proteins (FABPs): function, structure and polymorphism. J Appl Genet . 2006;47:39–48. doi: 10.1007/BF03194597. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Glatz JF, van der Vusse GJ. Cellular fatty acid-binding proteins: their function and physiological significance. Prog Lipid Res . 1996;35:243–282. doi: 10.1016/s0163-7827(96)00006-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Sweetser DA, Birkenmeier EH, Klisak IJ, Zollman S, Sparkes RS, Mohandas T, Lusis AJ, Gordon JI. The human and rodent intestinal fatty acid binding protein genes. A comparative analysis of their structure, expression, and linkage relationships. J Biol Chem . 1987;262:16060–16071. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Mansbach CM, Abumrad NA. Chapter 60 - Enterocyte Fatty Acid Handling Proteins and Chylomicron Formation. In: Johnson LR, Ghishan FK, Kaunitz JD, Merchant JL, Said HM, Wood JD, editors. Physiology of the Gastrointestinal Tract (Fifth Edition). Boston: Academic Press, 2012: 1625-1641. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Newberry EP, Xie Y, Kennedy S, Han X, Buhman KK, Luo J, Gross RW, Davidson NO. Decreased hepatic triglyceride accumulation and altered fatty acid uptake in mice with deletion of the liver fatty acid-binding protein gene. J Biol Chem . 2003;278:51664–51672. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M309377200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Atshaves BP, McIntosh AM, Lyuksyutova OI, Zipfel W, Webb WW, Schroeder F. Liver fatty acid-binding protein gene ablation inhibits branched-chain fatty acid metabolism in cultured primary hepatocytes. J Biol Chem . 2004;279:30954–30965. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M313571200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Huang H, Starodub O, McIntosh A, Atshaves BP, Woldegiorgis G, Kier AB, Schroeder F. Liver fatty acid-binding protein colocalizes with peroxisome proliferator activated receptor alpha and enhances ligand distribution to nuclei of living cells. Biochemistry . 2004;43:2484–2500. doi: 10.1021/bi0352318. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Glatz JF, Luiken JJ. From fat to FAT (CD36/SR-B2): Understanding the regulation of cellular fatty acid uptake. Biochimie . 2017;136:21–26. doi: 10.1016/j.biochi.2016.12.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Coburn CT, Knapp FF Jr, Febbraio M, Beets AL, Silverstein RL, Abumrad NA. Defective uptake and utilization of long chain fatty acids in muscle and adipose tissues of CD36 knockout mice. J Biol Chem . 2000;275:32523–32529. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M003826200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Lobo MV, Huerta L, Ruiz-Velasco N, Teixeiro E, de la Cueva P, Celdrán A, Martín-Hidalgo A, Vega MA, Bragado R. Localization of the lipid receptors CD36 and CLA-1/SR-BI in the human gastrointestinal tract: towards the identification of receptors mediating the intestinal absorption of dietary lipids. J Histochem Cytochem . 2001;49:1253–1260. doi: 10.1177/002215540104901007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Wilson CG, Tran JL, Erion DM, Vera NB, Febbraio M, Weiss EJ. Hepatocyte-Specific Disruption of CD36 Attenuates Fatty Liver and Improves Insulin Sensitivity in HFD-Fed Mice. Endocrinology . 2016;157:570–585. doi: 10.1210/en.2015-1866. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Murata M, Peränen J, Schreiner R, Wieland F, Kurzchalia TV, Simons K. VIP21/caveolin is a cholesterol-binding protein. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A . 1995;92:10339–10343. doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.22.10339. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Valasek MA, Weng J, Shaul PW, Anderson RG, Repa JJ. Caveolin-1 is not required for murine intestinal cholesterol transport. J Biol Chem . 2005;280:28103–28109. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M504609200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Pol A, Martin S, Fernandez MA, Ferguson C, Carozzi A, Luetterforst R, Enrich C, Parton RG. Dynamic and regulated association of caveolin with lipid bodies: modulation of lipid body motility and function by a dominant negative mutant. Mol Biol Cell . 2004;15:99–110. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E03-06-0368. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Mashek DG, Bornfeldt KE, Coleman RA, Berger J, Bernlohr DA, Black P, DiRusso CC, Farber SA, Guo W, Hashimoto N, Khodiyar V, Kuypers FA, Maltais LJ, Nebert DW, Renieri A, Schaffer JE, Stahl A, Watkins PA, Vasiliou V, Yamamoto TT. Revised nomenclature for the mammalian long-chain acyl-CoA synthetase gene family. J Lipid Res . 2004;45:1958–1961. doi: 10.1194/jlr.E400002-JLR200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Soupene E, Kuypers FA. Mammalian long-chain acyl-CoA synthetases. Exp Biol Med (Maywood) . 2008;233:507–521. doi: 10.3181/0710-MR-287. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Watkins PA, Maiguel D, Jia Z, Pevsner J. Evidence for 26 distinct acyl-coenzyme A synthetase genes in the human genome. J Lipid Res . 2007;48:2736–2750. doi: 10.1194/jlr.M700378-JLR200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Hisanaga Y, Ago H, Nakagawa N, Hamada K, Ida K, Yamamoto M, Hori T, Arii Y, Sugahara M, Kuramitsu S, Yokoyama S, Miyano M. Structural basis of the substrate-specific two-step catalysis of long chain fatty acyl-CoA synthetase dimer. J Biol Chem . 2004;279:31717–31726. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M400100200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Li LO, Klett EL, Coleman RA. Acyl-CoA synthesis, lipid metabolism and lipotoxicity. Biochim Biophys Acta . 2010;1801:246–251. doi: 10.1016/j.bbalip.2009.09.024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Yan S, Yang XF, Liu HL, Fu N, Ouyang Y, Qing K. Long-chain acyl-CoA synthetase in fatty acid metabolism involved in liver and other diseases: an update. World J Gastroenterol . 2015;21:3492–3498. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v21.i12.3492. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Poppelreuther M, Rudolph B, Du C, Großmann R, Becker M, Thiele C, Ehehalt R, Füllekrug J. The N-terminal region of acyl-CoA synthetase 3 is essential for both the localization on lipid droplets and the function in fatty acid uptake. J Lipid Res . 2012;53:888–900. doi: 10.1194/jlr.M024562. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Coleman RA, Lewin TM, Van Horn CG, Gonzalez-Baró MR. Do long-chain acyl-CoA synthetases regulate fatty acid entry into synthetic vs degradative pathways? J Nutr . 2002;132:2123–2126. doi: 10.1093/jn/132.8.2123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Ellis JM, Frahm JL, Li LO, Coleman RA. Acyl-coenzyme A synthetases in metabolic control. Curr Opin Lipidol . 2010;21:212–217. doi: 10.1097/mol.0b013e32833884bb. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Mashek DG, McKenzie MA, Van Horn CG, Coleman RA. Rat long chain acyl-CoA synthetase 5 increases fatty acid uptake and partitioning to cellular triacylglycerol in McArdle-RH7777 cells. J Biol Chem . 2006;281:945–950. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M507646200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Bu SY, Mashek MT, Mashek DG. Suppression of long chain acyl-CoA synthetase 3 decreases hepatic de novo fatty acid synthesis through decreased transcriptional activity. J Biol Chem . 2009;284:30474–30483. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109.036665. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Meller N, Morgan ME, Wong WP, Altemus JB, Sehayek E. Targeting of Acyl-CoA synthetase 5 decreases jejunal fatty acid activation with no effect on dietary long-chain fatty acid absorption. Lipids Health Dis . 2013;12:88. doi: 10.1186/1476-511X-12-88. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Klaus C, Kaemmerer E, Reinartz A, Schneider U, Plum P, Jeon MK, Hose J, Hartmann F, Schnölzer M, Wagner N, Kopitz J, Gassler N. TP53 status regulates ACSL5-induced expression of mitochondrial mortalin in enterocytes and colorectal adenocarcinomas. Cell Tissue Res . 2014;357:267–278. doi: 10.1007/s00441-014-1826-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Klaus C, Jeon MK, Kaemmerer E, Gassler N. Intestinal acyl-CoA synthetase 5: activation of long chain fatty acids and behind. World J Gastroenterol . 2013;19:7369–7373. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v19.i42.7369. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Paroder V, Spencer SR, Paroder M, Arango D, Schwartz S Jr, Mariadason JM, Augenlicht LH, Eskandari S, Carrasco N. Na(+)/monocarboxylate transport (SMCT) protein expression correlates with survival in colon cancer: molecular characterization of SMCT. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A . 2006;103:7270–7275. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0602365103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Rowe WA, Lesho MJ, Montrose MH. Polarized Na+/H+ exchange function is pliable in response to transepithelial gradients of propionate. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A . 1994;91:6166–6170. doi: 10.1073/pnas.91.13.6166. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Castro LF, Lopes-Marques M, Wilson JM, Rocha E, Reis-Henriques MA, Santos MM, Cunha I. A novel Acetyl-CoA synthetase short-chain subfamily member 1 (Acss1) gene indicates a dynamic history of paralogue retention and loss in vertebrates. Gene . 2012;497:249–255. doi: 10.1016/j.gene.2012.01.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Fujino T, Kondo J, Ishikawa M, Morikawa K, Yamamoto TT. Acetyl-CoA synthetase 2, a mitochondrial matrix enzyme involved in the oxidation of acetate. J Biol Chem . 2001;276:11420–11426. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M008782200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Sakakibara I, Fujino T, Ishii M, Tanaka T, Shimosawa T, Miura S, Zhang W, Tokutake Y, Yamamoto J, Awano M, Iwasaki S, Motoike T, Okamura M, Inagaki T, Kita K, Ezaki O, Naito M, Kuwaki T, Chohnan S, Yamamoto TT, Hammer RE, Kodama T, Yanagisawa M, Sakai J. Fasting-induced hypothermia and reduced energy production in mice lacking acetyl-CoA synthetase 2. Cell Metab . 2009;9:191–202. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2008.12.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Yoshimura Y, Araki A, Maruta H, Takahashi Y, Yamashita H. Molecular cloning of rat acss3 and characterization of mammalian propionyl-CoA synthetase in the liver mitochondrial matrix. J Biochem . 2017;161:279–289. doi: 10.1093/jb/mvw067. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Luong A, Hannah VC, Brown MS, Goldstein JL. Molecular characterization of human acetyl-CoA synthetase, an enzyme regulated by sterol regulatory element-binding proteins. J Biol Chem . 2000;275:26458–26466. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M004160200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Bulusu V, Tumanov S, Michalopoulou E, van den Broek NJ, MacKay G, Nixon C, Dhayade S, Schug ZT, Vande Voorde J, Blyth K, Gottlieb E, Vazquez A, Kamphorst JJ. Acetate Recapturing by Nuclear Acetyl-CoA Synthetase 2 Prevents Loss of Histone Acetylation during Oxygen and Serum Limitation. Cell Rep . 2017;18:647–658. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2016.12.055. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Huang Z, Zhang M, Plec AA, Estill SJ, Cai L, Repa JJ, McKnight SL, Tu BP. ACSS2 promotes systemic fat storage and utilization through selective regulation of genes involved in lipid metabolism. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A . 2018;115:E9499–E9506. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1806635115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Rios-Covian D, Salazar N, Gueimonde M, de Los Reyes-Gavilan CG. Shaping the Metabolism of Intestinal Bacteroides Population through Diet to Improve Human Health. Front Microbiol . 2017;8:376. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2017.00376. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.De Filippo C, Cavalieri D, Di Paola M, Ramazzotti M, Poullet JB, Massart S, Collini S, Pieraccini G, Lionetti P. Impact of diet in shaping gut microbiota revealed by a comparative study in children from Europe and rural Africa. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A . 2010;107:14691–14696. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1005963107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Wu GD, Chen J, Hoffmann C, Bittinger K, Chen YY, Keilbaugh SA, Bewtra M, Knights D, Walters WA, Knight R, Sinha R, Gilroy E, Gupta K, Baldassano R, Nessel L, Li H, Bushman FD, Lewis JD. Linking long-term dietary patterns with gut microbial enterotypes. Science . 2011;334:105–108. doi: 10.1126/science.1208344. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Arumugam M, Raes J, Pelletier E, Le Paslier D, Yamada T, Mende DR, Fernandes GR, Tap J, Bruls T, Batto JM, Bertalan M, Borruel N, Casellas F, Fernandez L, Gautier L, Hansen T, Hattori M, Hayashi T, Kleerebezem M, Kurokawa K, Leclerc M, Levenez F, Manichanh C, Nielsen HB, Nielsen T, Pons N, Poulain J, Qin J, Sicheritz-Ponten T, Tims S, Torrents D, Ugarte E, Zoetendal EG, Wang J, Guarner F, Pedersen O, de Vos WM, Brunak S, Doré J MetaHIT Consortium, Antolín M, Artiguenave F, Blottiere HM, Almeida M, Brechot C, Cara C, Chervaux C, Cultrone A, Delorme C, Denariaz G, Dervyn R, Foerstner KU, Friss C, van de Guchte M, Guedon E, Haimet F, Huber W, van Hylckama-Vlieg J, Jamet A, Juste C, Kaci G, Knol J, Lakhdari O, Layec S, Le Roux K, Maguin E, Mérieux A, Melo Minardi R, M'rini C, Muller J, Oozeer R, Parkhill J, Renault P, Rescigno M, Sanchez N, Sunagawa S, Torrejon A, Turner K, Vandemeulebrouck G, Varela E, Winogradsky Y, Zeller G, Weissenbach J, Ehrlich SD, Bork P. Enterotypes of the human gut microbiome. Nature . 2011;473:174–180. [Google Scholar]

- 72.Yatsunenko T, Rey FE, Manary MJ, Trehan I, Dominguez-Bello MG, Contreras M, Magris M, Hidalgo G, Baldassano RN, Anokhin AP, Heath AC, Warner B, Reeder J, Kuczynski J, Caporaso JG, Lozupone CA, Lauber C, Clemente JC, Knights D, Knight R, Gordon JI. Human gut microbiome viewed across age and geography. Nature . 2012;486:222–227. doi: 10.1038/nature11053. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Sonnenburg ED, Smits SA, Tikhonov M, Higginbottom SK, Wingreen NS, Sonnenburg JL. Diet-induced extinctions in the gut microbiota compound over generations. Nature . 2016;529:212–215. doi: 10.1038/nature16504. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Salonen A, Lahti L, Salojärvi J, Holtrop G, Korpela K, Duncan SH, Date P, Farquharson F, Johnstone AM, Lobley GE, Louis P, Flint HJ, de Vos WM. Impact of diet and individual variation on intestinal microbiota composition and fermentation products in obese men. ISME J . 2014;8:2218–2230. doi: 10.1038/ismej.2014.63. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Reichardt N, Duncan SH, Young P, Belenguer A, McWilliam Leitch C, Scott KP, Flint HJ, Louis P. Phylogenetic distribution of three pathways for propionate production within the human gut microbiota. ISME J . 2014;8:1323–1335. doi: 10.1038/ismej.2014.14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Louis P, Flint HJ. Formation of propionate and butyrate by the human colonic microbiota. Environ Microbiol . 2017;19:29–41. doi: 10.1111/1462-2920.13589. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Giri S, Oña L, Waschina S, Shitut S, Yousif G, Kaleta C, Kost C. Metabolic dissimilarity determines the establishment of cross-feeding interactions in bacteria. bioRxiv 2020: 2020.2010.2009.333336. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Wall R, Ross RP, Shanahan F, O'Mahony L, O'Mahony C, Coakley M, Hart O, Lawlor P, Quigley EM, Kiely B, Fitzgerald GF, Stanton C. Metabolic activity of the enteric microbiota influences the fatty acid composition of murine and porcine liver and adipose tissues. Am J Clin Nutr . 2009;89:1393–1401. doi: 10.3945/ajcn.2008.27023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Lennen RM, Politz MG, Kruziki MA, Pfleger BF. Identification of transport proteins involved in free fatty acid efflux in Escherichia coli. J Bacteriol . 2013;195:135–144. doi: 10.1128/JB.01477-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Golubeva YA, Ellermeier JR, Cott Chubiz JE, Slauch JM. Intestinal Long-Chain Fatty Acids Act as a Direct Signal To Modulate Expression of the Salmonella Pathogenicity Island 1 Type III Secretion System. mBio . 2016;7:e02170–e02115. doi: 10.1128/mBio.02170-15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Wolfe AJ. The acetate switch. Microbiol Mol Biol Rev . 2005;69:12–50. doi: 10.1128/MMBR.69.1.12-50.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Clark DP, Cronan JE. Two-Carbon Compounds and Fatty Acids as Carbon Sources. EcoSal Plus . 2005;1 doi: 10.1128/ecosalplus.3.4.4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Childers BM, Cao X, Weber GG, Demeler B, Hart PJ, Klose KE. N-terminal residues of the Vibrio cholerae virulence regulatory protein ToxT involved in dimerization and modulation by fatty acids. J Biol Chem . 2011;286:28644–28655. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M111.258780. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Cruite JT, Kovacikova G, Clark KA, Woodbrey AK, Skorupski K, Kull FJ. Structural basis for virulence regulation in Vibrio cholerae by unsaturated fatty acid components of bile. Commun Biol . 2019;2:440. doi: 10.1038/s42003-019-0686-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Ktsoyan ZA, Mkrtchyan MS, Zakharyan MK, Mnatsakanyan AA, Arakelova KA, Gevorgyan ZU, Sedrakyan AM, Hovhannisyan AI, Arakelyan AA, Aminov RI. Systemic Concentrations of Short Chain Fatty Acids Are Elevated in Salmonellosis and Exacerbation of Familial Mediterranean Fever. Front Microbiol . 2016;7:776. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2016.00776. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.van der Beek CM, Bloemen JG, van den Broek MA, Lenaerts K, Venema K, Buurman WA, Dejong CH. Hepatic Uptake of Rectally Administered Butyrate Prevents an Increase in Systemic Butyrate Concentrations in Humans. J Nutr . 2015;145:2019–2024. doi: 10.3945/jn.115.211193. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.den Besten G, van Eunen K, Groen AK, Venema K, Reijngoud DJ, Bakker BM. The role of short-chain fatty acids in the interplay between diet, gut microbiota, and host energy metabolism. J Lipid Res . 2013;54:2325–2340. doi: 10.1194/jlr.R036012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Zambell KL, Fitch MD, Fleming SE. Acetate and butyrate are the major substrates for de novo lipogenesis in rat colonic epithelial cells. J Nutr . 2003;133:3509–3515. doi: 10.1093/jn/133.11.3509. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Sunami Y, Rebelo A, Kleeff J. Lipid Metabolism and Lipid Droplets in Pancreatic Cancer and Stellate Cells. Cancers (Basel) . 2017;10 doi: 10.3390/cancers10010003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]