Abstract

Autoimmune hepatitis (AIH) is a severe chronic autoimmune disease and has a significant impact on the patient’s quality of life, in particular regarding psychological problems such as anxiety and depression. Consistent evidence on which patient-related, disease-related or physician-related factors cause health-related quality of life (HRQoL) impairment in patients with AIH is lacking. Current studies on HRQoL in AIH are mainly single-centered, comprising small numbers of patients, and difficult to compare because of the use of different questionnaires, patient populations, and cutoff values. Literature in the pediatric field is sparse, but suggests that children/adolescents with AIH have a lower HRQoL. Knowledge of HRQoL and cohesive factors in AIH are important to improve healthcare for AIH patients, for example by developing an AIH-specific chronic healthcare model. By recognizing the importance of quality of life beyond the concept of biochemical and histological remission, clinicians allow us to seek enhancements and possible interventions in the management of AIH, aiming at improved health.

Keywords: Autoimmune hepatitis, Quality of life, Depression, Anxiety, Corticosteroids

Core Tip: Autoimmune hepatitis (AIH) is a severe chronic autoimmune disease and has a significant impact on the patient’s quality of life, in particular regarding psychological problems such as anxiety and depression. The health-related quality of life (HRQoL) of patients with AIH can be affected by various patient-related, disease-related, and physician-related factors. In this review we summarized several specific factors that are liable to influence HRQoL in AIH. By recognizing the importance of quality of life beyond the concept of biochemical and histological remission, clinicians allow us to seek enhancements and possible interventions in the management of AIH.

INTRODUCTION

Autoimmune hepatitis (AIH) is a severe chronic autoimmune disease that occurs mainly in women and affects health-related quality of life (HRQoL) worldwide. The diagnosis of AIH is based on the presence of autoantibodies, typical features on liver histology, and increased immunoglobulin G (IgG) levels[1]. The presentation of AIH is variable, ranging from mild and asymptomatic disease to fulminant hepatic failure. Nonspecific symptoms at presentation are fatigue, anorexia, jaundice, and abdominal pain, whereas others are asymptomatic at disease onset[1]. The majority of patients need lifelong treatment to prevent disease progression to cirrhosis and/or decompensation[2]. Current treatment strategies in AIH include administering corticosteroids (mainly prednisolone) and a long-term corticosteroid-saving regime, including azathioprine (AZA) as first-line treatment[3,4]. Second-line immunosuppressants include mycophenolate mofetil (MMF), calcineurin inhibitors (CNIs), and mercaptopurine and have proven to be effective in mainly uncontrolled studies[5].

The main goal of AIH treatment is to achieve complete biochemical and histological remission without the occurrence of side effects. Alanine aminotransferase, aspartate aminotransferase and IgG serum levels are used as parameters to monitor biochemical response, and current guidelines advocate pursuit of normalization of those parameters as the aim of treatment. As a result, treatment failure, defined as absence of normalization of transaminases, triggers clinical actions such as increase of drug dose or change in drug class. A sole focus on biochemical response is insufficient when managing AIH. From a patient perspective, other aspects that affect HRQoL, including but not limited to side effects, psychological health, and implications of the disease, are just as important.

One of the main objectives relating to AIH according to the International Autoimmune Hepatitis Group (IAIHG), is better assessment of HRQoL in patients. However, literature or guidelines on that topic in AIH are scarce and inconsistent. An update on current literature on HRQoL in AIH, is warranted to reveal the most important research gaps[6]. Understanding which potentially treatable factors are associated with reduced quality of life in patients with AIH is essential for development of interventions targeting well-being. The focus of this paper is to review the current knowledge of HRQoL and associated factors in AIH, to comment on the current status, and to identify future perspectives that may influence and benefit disease management of adult patients with AIH.

METHODOLOGY

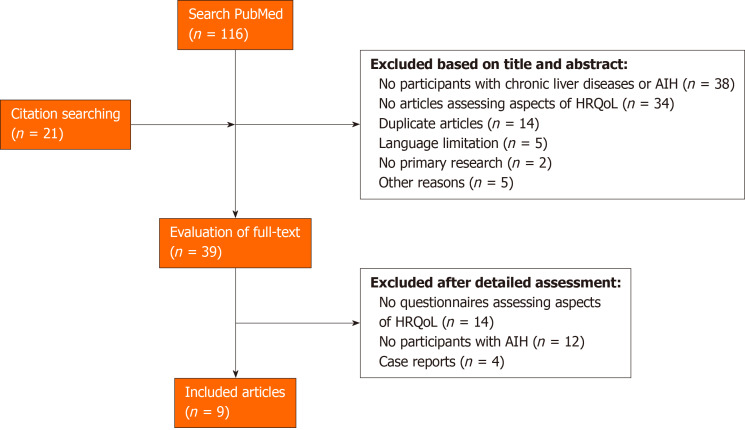

We searched the titles, abstracts, and MeSH terms of articles indexed in PubMed using the keywords “autoimmune hepatitis,” “AIH,” “health-related quality of life,” and “quality of life.” The search was limited to articles published before January 27, 2021. We included articles based on the following criteria: (1) Full-text articles published in peer-reviewed journals; (2) English or Dutch articles; (3) Publication dates within the last 20 years at the time of the search; and (4) Either adult or pediatric AIH. The search retrieved 116 publications; 39 were evaluated in full-text after screening the titles and abstracts (Figure 1). We also checked the reference lists of the included articles to identify other articles. For the purpose of this review, we primarily focused on articles addressing the role of HRQoL in AIH.

Figure 1.

Flowchart of included studies after performing the literature search. AIH: Autoimmune hepatitis; HRQoL: Health-related quality of life.

HRQOL IN ADULT PATIENTS WITH AIH

Several studies have reported reduced general or liver-specific HRQoL in AIH patients (Tables 1 and 2)[7-15]. The first study published was conducted in the Netherlands and showed a reduced quality of life in 141 patients with AIH compared with healthy controls, using three instruments, the SF-36 for generic HRQoL, the Multidimensional Fatigue Index-20, and the Liver Disease Symptom Index 2.0, which is a liver-specific questionnaire addressing nine topics. In particular, patients had lower scores in subscales measuring physical problems or general health. Patients with AIH mentioned fatigue more often than healthy controls did[13]. A landmark study performed in Germany compared 102 AIH patients to the German general population and to published data of patients with arthritis using the SF-12[12]. They reported lower mental well-being in patients with AIH compared with both groups, but the physical component score (PCS) was unaffected[12]. A Polish single-center study showed that patients with AIH (n = 140) scored significantly worse in all subscales of the SF-36, except for one measuring the impact of emotional problems on work and daily activities[15]. The majority of the AIH patients in that cohort had cirrhosis (55%), and as in the previously mentioned study, that did not have a significant effect on well-being. A recent Italian multicenter study of chronic liver disease reported that of a total of seven different chronic liver diseases without cirrhosis, patients with AIH had a lower quality of life measured with the EQ-5D VAS score, and experienced difficulties in the self-care domain, even after adjusting for multiple possible confounders, including age, sex, education, and professional status[10]. That was confirmed in a Cuban study in which AIH patients had lower quality of life scores than hepatitis B patients using the disease-specific Chronic Liver Disease Questionnaire (CLDQ)[7]. Only one meta-analysis was performed, including three studies that evaluated HRQoL measured with the SF-36. The analysis confirmed reduction of the PCS and mild reduction of the mental component score in patients with AIH. However, they included only older studies and compared all AIH patients (including Dutch and German patients) to the United States general population norm[16]. Finally, the largest study conducted so far involved multiple health centers in the United Kingdom and confirmed previous results by finding that the HRQoL of patients with AIH (n = 990) was worse than it was in the general population, adjusted for age and gender and using the EQ-5D-5L[14]. Although these studies consistently report a lower HRQoL in AIH, albeit in varying domains, it remains difficult to compare the studies because of the use of different questionnaires (EQ-5D-5L vs SF-12 or SF-36 vs CLDQ), cutoff values, methodology, and patient populations. Moreover, most studies were conducted at single centers and included small numbers of participants, thereby introducing bias based on the heterogenicity in study populations (e.g., remission status and demographic differences).

Table 1.

Overview of the studies assessing aspects of health-related quality of life in autoimmune hepatitis

|

Ref.

|

Country

|

Population (n)

|

Biochemical remission (%)

|

Cirrhosis (%)

|

Questionnaire

|

Factors/results

|

| van der Plas et al[13], 2007 | The Netherlands | AIH (142), other liver diseases (776) | - | - | SF-36, MFI-20, LDSI | HRQoL impairment; Association with: Fatigue |

| Afendy et al[8], 2009 | United States, Italy | AIH (13), other chronic liver diseases (1090) | - | 84.61 | SF-36 | HRQoL impairment; Negative correlation: Age (every scale), female gender (primary predictor of mental health), cirrhosis (every scale, primary predictor of physical health) |

| Schramm et al[12], 2014 | Germany | AIH (103) | 77 | 27 | SF-12, PHQ-9, GAD-7 | HRQoL impairment (total mental score/mental well-being); Association with: depression and anxiety (positive correlation with female gender, corticosteroid use, and concerns about progression of the liver disease) |

| Takahashi et al[11], 2018 | Japan | AIH (265), chronic hepatitis C (88) | - | 10.6 | CLDQ, SF-36 | HRQoL impairment; Negative correlation: Age, cirrhosis, comorbid diseases, corticosteroid use (worry domain), disease duration, AST; Positive correlation: platelet count |

| Wong et al[14], 2018 | United Kingdom | AIH (990) | 56 | 33 | EQ-5D-5L, FIS, CFQ, HADS | HRQoL impairment; Positive correlation: Biochemical remission; Negative correlation: overlap syndromes, corticosteroid use, and calcineurin inhibitor use |

| Janik et al[15], 2019 | Poland | AIH (140) | - | 55 | SF-36, MFIS, PHQ-9, STAI | HRQoL impairment (every scale, except role emotional2); Negative correlation: Female gender, depression, trend toward better HRQoL (physical health) with budesonide vs prednisone; Association with: Anxiety, depression, and fatigue |

| Dirks et al[9], 2019 | Germany | AIH (27), AIH/PBC (8), other liver diseases (97) | - | 0 | SF-36, FIS, HADS | HRQoL impairment; Association with: Anxiety, depression, and fatigue |

| Castellanos-Fernández et al[7], 2021 | Cuba | AIH (22), overlap syndrome of AIH and PBC (7), PBC (14), other liver diseases (500) | - | 43.93 | FACIT-F, WPAI:SHP, CLDQ | HRQoL impairment; Positive correlation: Male gender, exercising > 90 min/wk; Negative correlation: Fatigue, abdominal pain, anxiety, depression, and extrahepatic comorbidity (diabetes mellitus type 2, sleep apnea) |

| Cortesi et al[10], 2020 | Italy | AIH (51), other chronic liver diseases (2911) | - | 0 | EQ-5D-3L | HRQoL impairment in AIH |

Eight patients with Child-Pugh class A and three patients with Child-Pugh class C.

Scale measures the impact of emotional problems on work and daily activities.

Cirrhosis in patients with autoimmune liver diseases (n = 43). AIH: Autoimmune hepatitis; HRQoL: Health-related quality of life; PBC: Primary biliary cholangitis; AST: Aspartate aminotransferase; CFQ: Cognitive failure questionnaire; CLDQ: Chronic liver disease questionnaire; ECR: Experiences in close relationship scale; EQ-5D-5L/3L: European quality of life 5-dimension 5-level/3-level; FACIT-F: Functional assessment of chronic illness therapy-fatigue; FIS: Fatigue impact scale; GAD-7: Generalized anxiety disorder screener; HADS: Hospital anxiety depression scale; LDSI: Liver disease symptom index 2.0; MFI-20: Multidimensional fatigue index-20; PHQ-9: Patient health questionnaire; SF-12: Short-form 12; SF-36: Short-form 36; STAI: State-trait anxiety inventory; WPAI:SHP: Work productivity and activity-specific health problem.

Table 2.

Overview of the questionnaires assessing aspects of health-related quality of life in autoimmune hepatitis

|

Questionnaire

|

Main function

|

Domains

|

Items, total score

|

| CFQ[41] | Cognition | Memory, attention, concentration, forgetfulness, word-finding abilities, and confusion | 25 items scored 0-4, total score 0-100 |

| CLDQ[42] | Generic HRQoL | Abdominal symptoms, fatigue, systemic symptoms, activity, emotions, and worry | 29 items scored 1-7, total score 29-203 |

| ECR[43] | Relationship styles | ECR-anxiety, and ECR-avoidance | 12 items scored 1-7, each scale total score 7-42 |

| EQ-5D-5L/EQ-5D-3L/EQ-VAS[44] | Generic HRQoL, EQ-VAS: participants’ self-rated health on a visual analog scale | Mobility, self-care, usual activities, pain/discomfort, and anxiety/depression | EQ-5D: 5 items scored 1-5, total score 5-25; EQ-VAS: total score 0-100 |

| FACIT-F[45] | Fatigue | Physical well-being, social well-being, emotional well-being, functional well-being, and a fatigue-specific domain | 40 items scored 0-4, total score 0-160 |

| FIS[46] | Fatigue | Cognitive functioning, physical functioning, and psychosocial functioning | 40 items scored 0-4, total score 0-160 |

| GAD-7[47] | Anxiety | - | 7 items scored 0-3, total score 0-21 |

| HADS[48] | Anxiety, depression | Anxiety, and depression | 14 items scored 0-3, total score 0-42 |

| LDSI[49] | Liver disease symptoms | Itch, joint pain, abdominal pain, daytime sleepiness, worry about family situation, decreased appetite, depression, fear of complications, and jaundice (+ symptom hinderance) | 18 items scored 1-5, total score 18-90 |

| MFI-20[50] | Fatigue | General fatigue, physical fatigue, reduction in activity, reduction in motivation, and mental fatigue | 20 items scored 1-5, each domain total score 4-20 |

| MFIS[46,51] | Fatigue | Physical, cognitive, and psychosocial functioning | 21 items scored 0-4, total score 0-84 |

| PHQ-9[52] | Depression | Anhedonia, feeling down, sleep, feeling tired, appetite, feeling bad about self, concentration, activity, and suicidality | 9 items scored 0-3, total score 0-27 |

| SF-12[53] | Generic HRQoL | Physical functioning, role limitations due to physical problems, bodily pain, general health, vitality, social functioning, role limitations due to emotional problems, and mental health | 12 items scored 1-5, total score 0-100 |

| SF-36[54] | Generic HRQoL | General health, physical and social functioning, bodily pain, role-physical, mental health, role-emotional, and vitality | 36 items, total score 0-100 |

| STAI[55] | Anxiety | State anxiety, and trait anxiety | 40 items scored 1-4, total score 0-80 |

| WPAI:SHP[56] | Impairment in daily activities and in work | Work productivity impairment, and activity impairment | 6 items scored 0-10, total score - |

Included in the table are the questionnaires that were employed in the reviewed studies. CFQ: Cognitive Failure Questionnaire; CLDQ: Chronic Liver Disease Questionnaire; ECR: Experiences in Close Relationship Scale; EQ-5D-5L/EQ-5D-3L/EQ-VAS: European Quality of life 5-Dimension 5-Level/3-Level/EQ-visual analog scale; FACIT-F: Functional Assessment of Chronic Illness Therapy-Fatigue; FIS: Fatigue Impact Scale; GAD-7: Generalized Anxiety Disorder Screener; HADS: Hospital Anxiety Depression Scale; LDSI: Liver Disease Symptom Index 2.0); MFI-20: Multidimensional Fatigue Index-20; MFIS: Modified Fatigue Impact Scale); PHQ-9: Patient Health Questionnaire; SF-12: Short-form 12; SF-36: Short-form 36; STAI: State-Trait Anxiety Inventory; WPAI:SHP: Work Productivity and Activity-Specific Health Problem).

HRQOL IN PEDIATRIC PATIENTS WITH AIH

A lower HRQoL was also found in children and adolescents with AIH, although literature in the pediatric field is sparse[17-19]. A study performed in Portugal compared 43 children with AIH to 62 healthy children using the Pediatric Quality of Life Inventory 4.0 (PedsQL 4.0)[17]. They found that especially children with associated comorbidities (e.g., inflammatory bowel disease, hemolytic anemia, and hypothyroidism) had a lower quality of life. That was confirmed in a Brazilian cohort using the same questionnaire[18]. Interestingly, the evaluation of HRQoL in the parents differed from the children’s self-reports[18]. Only the physical and total scores were significantly lower in patients with AIH based on the parental reports, whereas in the children’s reports the emotional, school, physical, and total scores were significantly lower.

DETERMINANTS OF HRQOL IN AIH

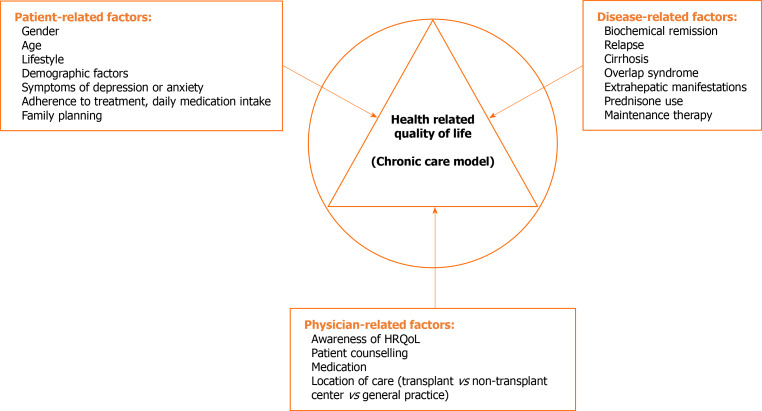

The HRQoL of patients with chronic diseases can be affected by various patient-related, disease-related, and physician-related factors. We have summarized the patient-, disease- and physician-related factors that are liable to influence HRQoL in AIH in Figure 2.

Figure 2.

Patient-, disease- and physician-related factors affecting health-related quality of life in patients with autoimmune hepatitis. HRQoL: Health-related quality of life.

Patient-related factors

Patients with AIH are more often diagnosed with symptoms of depression and anxiety compared with the general population or healthy controls[7,9,10,12,15]. Studies by Schramm and Janik et al[15] showed a significantly higher percentage of depression and anxiety symptoms, measured with the PHQ-9, GAD-7, or State-Trait Anxiety Inventory[12,15]. Depression was strongly correlated with both physical and mental components of SF-36. Despite biochemical remission in 77% of the patients (n = 103), the occurrence of severe depressive symptoms within the German cohort appeared to be five times as frequent compared with the general population.12 In addition, even AIH patients without cirrhosis revealed more problems with regard to depression and anxiety compared with the general population[10]. It is interesting to note that psychological stress was also associated with relapses in patients with AIH type 1[20].

Other patient-related factors, particularly age and sex, have been described often in previous studies[7,11,12,14]. Studies in the United Kingdom and Japan reported a negative correlation between age and HRQoL[11,14], but Polish and Cuban studies did not find such a correlation [7,15]. With respect to sex differences, female patients experience more symptoms of depression[12,15] and have a worse quality of life than their male counterparts[7,15]. In our experience, women experience weight increase and other cosmetic changes associated with corticosteroids as a great inconvenience in particular. In contrast, a study in the United Kingdom study found that the female sex was associated with a higher quality of life, albeit in an unadjusted regression analysis. These inconsistent correlations highlight that we still do not know which patient factors are important when assessing HRQoL in patients with AIH.

For all chronic liver diseases, it holds that lifestyle changes are part of the treatment. While tackling lifestyle is a hot topic in chronic disease, it is infrequently addressed in AIH. However, patients should still be informed about the risk of specific lifestyles, such as overweight, alcohol misuse, and sedentary behavior. Losing weight, more exercise, and a healthier diet contribute to successful management of chronic liver diseases and cirrhosis[21]. Indeed, exercising for more than 90 min/wk is a predictor of a better quality of life in patients with chronic liver diseases (e.g., AIH)[7]. Another study confirmed that an increased body mass index was associated with a lower quality of life in patients with AIH[14]. In addition, alcohol consumption presents a clear risk of the progression of liver fibrosis in chronic liver diseases. Other factors, such as education level, socioeconomic data, smoking, or losing weight, were not frequently mentioned in the described studies. It follows that physicians need to communicate with patients about lifestyle adaptations through motivational interviews.

Coping with chronic conditions and taking medication daily goes hand in hand with discomfort, which potentially results in reduced HRQoL. Patients with more than one chronic disease that take daily medication have a lower quality of life[22]. Adherence to treatment is rarely discussed with patients but has a great impact on well-being and treatment response. A high psychosocial burden has been shown to significantly decrease adherence to treatment and to be associated with poor treatment response[23]. Therefore, prompt recognition of symptoms of depression and anxiety is important to improve patient adherence and lead to better response to treatment. Various factors may influence adherence to drug treatment in adolescents with AIH, particularly depression, anxiety, younger age, sex, prednisone dose, and long-term therapy have been found in previous studies[23-25]. In liver transplant recipients, marital status (if the patient is divorced) and having mental distress are associated with reduced self-reported adherence to immunotherapy[26]. However, information on demographic factors or socioeconomic data, including the status of a relationship and educational level, were not explicitly examined in all previous studies, which would be necessary for more detailed conclusions.

Disease-related factors

As mentioned previously, the main objective in treating AIH is to achieve complete biochemical and histological remission without side effects. While it is plausible that achieving biochemical remission results in better HRQoL, the association has not been studied often. One study found that patients with biochemical remission had a significantly higher quality of life [14]. One could speculate that incomplete biochemical remission causes uncertainty about, and possibly fear of, a relapse, which is understandable given that every relapse increases the risk of decompensated liver failure or the necessity of liver transplantation[27]. Whether this has a role in AIH is unknown at present.

Liver cirrhosis, or an advanced stage of fibrosis in patients with chronic liver disease is a known cause for reduced HRQoL, independent of the underlying liver disease[8,28,29]. However, studies in patients with AIH demonstrate significant variability regarding the relation between fibrosis and HRQoL. Most studies describe that having liver fibrosis or compensated cirrhosis does not affect patient well-being in general[12,14,15]. In contrast, another study did find an impaired physical condition in patients with AIH using the same SF-36 questionnaire and an overall lower quality of life using the CLDQ[11]. Plausible explanations for the discrepancy are the use of different general vs disease-specific, SF-36 vs SF-12 vs EQ-5D-5L questionnaires and the inclusion of different AIH populations regarding biochemical remission status and disease duration. Interestingly, none of the cited studies included AIH patients with decompensated cirrhosis in their cohort, which is known to be a major factor for reduced HRQoL in cirrhosis with other etiologies[30,31].

Patients with an overlap syndrome or a variant syndrome of AIH and primary biliary cholangitis (PBC) or primary sclerosing cholangitis (PSC), had a worse quality of life than patients not reporting those comorbidities[7,9,14]. In addition, fatigue is a typical symptom in patients with characteristics of PBC, and is expected to have a negative impact on HRQoL[7,9]. In that context, it is not only essential to treat both AIH and the overlapping syndrome (i.e., PBC or PSC), but also to address associated symptoms (i.e., IBD in PSC, itch in PBC) in the patients[14]. Interestingly, such a correlation was not found in a study in children with autoimmune liver diseases. It found no differences in HRQoL scores in children with AIH vs overlap syndrome or variant syndrome with PSC[19]. Extrahepatic manifestations, for example thyroid disease, insulin-dependent diabetes mellitus, connective tissue disorders, and autoimmune skin disease, are common in AIH and can affect well-being, including fatigue, but the effect on HRQoL is unstudied so far[32].

A large proportion of patients with AIH receive corticosteroid therapy[11,33]. All treatments have specific side effects[34,35], but long-term use of corticosteroids is well-known for its undesirable effects, including osteoporosis, mood swings, depression, obesity, cognitive dysfunction, chronic fatigue, and reduced physical activity[1,5]. The negative impact of the use of corticosteroids on HRQoL was demonstrated in several studies[12,14]. In the United Kingdom cohort, corticosteroids were extensively linked to impaired HRQoL. Even patients who received low-dose of corticosteroids, and independent of their biochemical status, had a lower HRQoL[14]. Schramm et al[12] found a significant correlation between corticosteroids and depression. Sockalingam et al[23] found that patients with a moderate or high PHQ-9 score of > 10 were administered a significantly higher dose of prednisone compared with patients with a score of < 10. These data give additional support for steroid-free therapy as a treatment goal in every AIH patient to prevent steroid-related complications, and should be attempted within the first year of treatment. Other disease-related factors affecting mental well-being or HRQoL, such as markers of disease activity or disease duration, are so far unknown[12,15].

Currently, AZA is still the primary choice for maintenance therapy, and was not directly associated with a lower quality of life or health utility in a large cross-sectional analysis[14]. It is important to note that the use of AZA is associated with an increased risk of lymphoma and nonmelanoma skin cancer[36,37]. Although lymphoma in the long term is rare, it has to be taken into account that the occurrence of these side effects, or even the patient’s concerns, might affect their quality of life. AZA may also cause hair loss that leads to alopecia. The possibility is frequently raised by the female patients and may affect various aspects of quality of life and lead to incompliance. The effect of other prescribed therapies on improving psychosocial outcomes, such as mycophenolate mofetil and mercaptopurine, is unknown. However, calcineurin inhibitors that have undesirable effects may be associated with lower health utility[14].

Physician-related factors

Physician-related factors are usually not addressed in studies and are thus difficult to take into account. Schramm et al[12] found that patient concerns about the severity of their disease, and being fearful of cirrhosis (mostly unnecessary) were factors associated with depression and anxiety symptoms. Providing the patient with information on his/her illness or medications and involving the patient in treatment options, can contribute to the patient’s well-being. Whether the location of care (i.e. transplant vs nontransplant center) matters is uncertain. One study showed that there was no difference in health utility between transplant and nontransplant centers[14], and another found that biochemical remission rates were higher in transplant centers compared with nontransplant centers[33]. Both were conducted in the United Kingdom. Extrapolation of the results to other countries is difficult given the differences in health care management among countries.

CONCLUSION

It is clear that patients with AIH experience a lower quality of life and have more psychological problems, such as anxiety and depression, compared with the general population. Consistent evidence on which patient-related, disease-related, or physician-related factors cause HRQoL impairment in patients with AIH is lacking. Most studies did not include information on important socioeconomic, disease behavior, maintenance treatment, or even geographical factors, whereas they are known to affect patient well-being and HRQoL in other chronic liver diseases. In addition, some aspects of AIH are unexplored so far, for example the effect of lifestyle changes, extrahepatic manifestations, and patient counseling on HRQoL. Studies addressing HRQoL in pediatric AIH and their parents/support team are scarce and are desperately needed as a first step to improve their well-being.

Knowledge of HRQoL and associated factors in AIH are important to improve healthcare for AIH patients, for example by incorporating the factors in a chronic healthcare model (CCM). A CCM provides a clear approach for managing chronic diseases, with focus on assessment of the modifiable factors affecting the disease in order to improve patient well-being. While no studies mentioned a CCM for AIH so far, some studies discussed elements that could be part of a model. For example, Janik et al[38] screened AIH patients for moderately severe depression and redirected them to a psychiatrist and psychiatric therapeutic interventions in case of a PHQ ≥ 15 points. Another example are lifestyle interventions for overweight patients[39]. There is also a role for the development of a disease-specific questionnaire for AIH patients, similar to the PBC-40 questionnaire, to measure the patient’s perspective of the disease[40]. In what way, a CCM can be developed and implemented that would probably differ from country to country because of differences in health care. However, it is paramount that the AIH-specific CCM incorporate the most important factors of HRQoL in AIH, as discussed in this review.

Finally, HRQoL should not only be targeted in everyday clinical treatment approaches, but also as an important outcome of clinical trials and a research objective per se. Most studies of HRQoL in AIH have been conducted at a single center and comprised small numbers of patients, which underlines the need for collaboration between healthcare centers in different countries. Currently, there is an ongoing multicenter, cross-sectional study of HRQoL in patients with AIH within the European Network for Rare Liver Diseases. Recognizing the importance that quality of life has for the patient beyond the concept of biochemical and histological remission allows us to strive for significant improvements in management of adult and pediatric AIH.

Footnotes

Conflict-of-interest statement: All authors report no potential conflicts that are relevant to the manuscript.

Provenance and peer review: Invited article; Externally peer reviewed.

Peer-review started: March 25, 2021

First decision: June 4, 2021

Article in press: August 16, 2021

Specialty type: Gastroenterology and hepatology

Country/Territory of origin: Netherlands

Peer-review report’s scientific quality classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): 0

Grade C (Good): C

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

P-Reviewer: Shahini E S-Editor: Gao CC L-Editor: Filipodia P-Editor: Li JH

Contributor Information

Romée JALM Snijders, Department of Gastroenterology and Hepatology, Radboudumc, Nijmegen 6525GA, The Netherlands; European Reference Network RARE-LIVER, Hamburg, Germany.

Piotr Milkiewicz, Liver and Internal Medicine Unit, Medical University of Warsaw, Warsaw 02-091, Poland; Translational Medicine Group, Pomeranian Medical University, Szczecin 70-204, Poland; European Reference Network RARE-LIVER, Hamburg, Germany.

Christoph Schramm, First Department of Medicine, University Medical Center Hamburg Eppendorf, Hamburg 20246, Germany; Martin Zeitz Center for Rare Diseases and Hamburg Center for Translational Immunology (HCTI), University Medical Center Hamburg Eppendorf, Hamburg 20246, Germany; European Reference Network RARE-LIVER, Hamburg, Germany.

Tom JG Gevers, Department of Gastroenterology and Hepatology, Radboudumc, Nijmegen 6525GA, The Netherlands; Division of Gastroenterology and Hepatology, Maastricht University Medical Center, Maastricht 6229HX, The Netherlands; European Reference Network RARE-LIVER, Hamburg, Germany. tom.gevers@mumc.nl.

References

- 1.Manns MP, Czaja AJ, Gorham JD, Krawitt EL, Mieli-Vergani G, Vergani D, Vierling JM American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases. Diagnosis and management of autoimmune hepatitis. Hepatology. 2010;51:2193–2213. doi: 10.1002/hep.23584. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Harrison L, Gleeson D. Stopping immunosuppressive treatment in autoimmune hepatitis (AIH): Is it justified (and in whom and when)? Liver Int. 2019;39:610–620. doi: 10.1111/liv.14051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Doycheva I, Watt KD, Gulamhusein AF. Autoimmune hepatitis: Current and future therapeutic options. Liver Int. 2019;39:1002–1013. doi: 10.1111/liv.14062. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Terziroli Beretta-Piccoli B, Mieli-Vergani G, Vergani D. Autoimmune hepatitis: Standard treatment and systematic review of alternative treatments. World J Gastroenterol. 2017;23:6030–6048. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v23.i33.6030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.European Association for the Study of the Liver. EASL Clinical Practice Guidelines: Autoimmune hepatitis. J Hepatol. 2015;63:971–1004. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2015.06.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Dyson JK, De Martin E, Dalekos GN, Drenth JPH, Herkel J, Hubscher SG, Kelly D, Lenzi M, Milkiewicz P, Oo YH, Heneghan MA, Lohse AW IAIHG Consortium. Review article: unanswered clinical and research questions in autoimmune hepatitis-conclusions of the International Autoimmune Hepatitis Group Research Workshop. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2019;49:528–536. doi: 10.1111/apt.15111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Castellanos-Fernández MI, Borges-González SA, Stepanova M, Infante-Velázquez ME, Ruenes-Domech C, González-Suero SM, Dorta-Guridi Z, Arus-Soler ER, Racila A, Younossi ZM. Health-related quality of life in Cuban patients with chronic liver disease: A real-world experience. Ann Hepatol. 2021;22:100277. doi: 10.1016/j.aohep.2020.10.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Afendy A, Kallman JB, Stepanova M, Younoszai Z, Aquino RD, Bianchi G, Marchesini G, Younossi ZM. Predictors of health-related quality of life in patients with chronic liver disease. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2009;30:469–476. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2036.2009.04061.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Dirks M, Haag K, Pflugrad H, Tryc AB, Schuppner R, Wedemeyer H, Potthoff A, Tillmann HL, Sandorski K, Worthmann H, Ding X, Weissenborn K. Neuropsychiatric symptoms in hepatitis C patients resemble those of patients with autoimmune liver disease but are different from those in hepatitis B patients. J Viral Hepat. 2019;26:422–431. doi: 10.1111/jvh.12979. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cortesi PA, Conti S, Scalone L, Jaffe A, Ciaccio A, Okolicsanyi S, Rota M, Fabris L, Colledan M, Fagiuoli S, Belli LS, Cesana G, Strazzabosco M, Mantovani LG. Health related quality of life in chronic liver diseases. Liver Int. 2020;40:2630–2642. doi: 10.1111/liv.14647. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Takahashi A, Moriya K, Ohira H, Arinaga-Hino T, Zeniya M, Torimura T, Abe M, Takaki A, Kang JH, Inui A, Fujisawa T, Yoshizawa K, Suzuki Y, Nakamoto N, Koike K, Yoshiji H, Goto A, Tanaka A, Younossi ZM, Takikawa H Japan AIH Study Group. Health-related quality of life in patients with autoimmune hepatitis: A questionnaire survey. PLoS One. 2018;13:e0204772. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0204772. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Schramm C, Wahl I, Weiler-Normann C, Voigt K, Wiegard C, Glaubke C, Brähler E, Löwe B, Lohse AW, Rose M. Health-related quality of life, depression, and anxiety in patients with autoimmune hepatitis. J Hepatol. 2014;60:618–624. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2013.10.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.van der Plas SM, Hansen BE, de Boer JB, Stijnen T, Passchier J, de Man RA, Schalm SW. Generic and disease-specific health related quality of life of liver patients with various aetiologies: a survey. Qual Life Res. 2007;16:375–388. doi: 10.1007/s11136-006-9131-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wong LL, Fisher HF, Stocken DD, Rice S, Khanna A, Heneghan MA, Oo YH, Mells G, Kendrick S, Dyson JK, Jones DEJ UK-AIH Consortium. The Impact of Autoimmune Hepatitis and Its Treatment on Health Utility. Hepatology. 2018;68:1487–1497. doi: 10.1002/hep.30031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Janik MK, Wunsch E, Raszeja-Wyszomirska J, Moskwa M, Kruk B, Krawczyk M, Milkiewicz P. Autoimmune hepatitis exerts a profound, negative effect on health-related quality of life: A prospective, single-centre study. Liver Int. 2019;39:215–221. doi: 10.1111/liv.13960. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Honoré LR, Kjær TW, Kjær MS. Health-related quality of life in patients with autoimmune hepatitis - a systematic review and meta-analysis. Clin Res Hepatol Gastroenterol. 2018;42:e97–e99. doi: 10.1016/j.clinre.2018.06.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Trevizoli IC, Pinedo CS, Teles VO, Seixas RBPM, de Carvalho E. Autoimmune Hepatitis in Children and Adolescents: Effect on Quality of Life. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2018;66:861–865. doi: 10.1097/MPG.0000000000001930. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bozzini AB, Neder L, Silva CA, Porta G. Decreased health-related quality of life in children and adolescents with autoimmune hepatitis. J Pediatr (Rio J) 2019;95:87–93. doi: 10.1016/j.jped.2017.10.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Gulati R, Radhakrishnan KR, Hupertz V, Wyllie R, Alkhouri N, Worley S, Feldstein AE. Health-related quality of life in children with autoimmune liver disease. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2013;57:444–450. doi: 10.1097/MPG.0b013e31829ef82c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Srivastava S, Boyer JL. Psychological stress is associated with relapse in type 1 autoimmune hepatitis. Liver Int. 2010;30:1439–1447. doi: 10.1111/j.1478-3231.2010.02333.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Tandon P, Berzigotti A. Management of Lifestyle Factors in Individuals with Cirrhosis: A Pragmatic Review. Semin Liver Dis. 2020;40:20–28. doi: 10.1055/s-0039-1696639. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Moussavi S, Chatterji S, Verdes E, Tandon A, Patel V, Ustun B. Depression, chronic diseases, and decrements in health: results from the World Health Surveys. Lancet. 2007;370:851–858. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(07)61415-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Sockalingam S, Blank D, Abdelhamid N, Abbey SE, Hirschfield GM. Identifying opportunities to improve management of autoimmune hepatitis: evaluation of drug adherence and psychosocial factors. J Hepatol. 2012;57:1299–1304. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2012.07.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Leoni MC, Amelung L, Lieveld FI, van den Brink J, de Bruijne J, Arends JE, van Erpecum CP, van Erpecum KJ. Adherence to ursodeoxycholic acid therapy in patients with cholestatic and autoimmune liver disease. Clin Res Hepatol Gastroenterol. 2019;43:37–44. doi: 10.1016/j.clinre.2018.08.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Gray WN, Denson LA, Baldassano RN, Hommel KA. Treatment adherence in adolescents with inflammatory bowel disease: the collective impact of barriers to adherence and anxiety/depressive symptoms. J Pediatr Psychol. 2012;37:282–291. doi: 10.1093/jpepsy/jsr092. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lamba S, Nagurka R, Desai KK, Chun SJ, Holland B, Koneru B. Self-reported non-adherence to immune-suppressant therapy in liver transplant recipients: demographic, interpersonal, and intrapersonal factors. Clin Transplant. 2012;26:328–335. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-0012.2011.01489.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Montano-Loza AJ, Carpenter HA, Czaja AJ. Consequences of treatment withdrawal in type 1 autoimmune hepatitis. Liver Int. 2007;27:507–515. doi: 10.1111/j.1478-3231.2007.01444.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Younossi Z, Henry L. Overall health-related quality of life in patients with end-stage liver disease. Clin Liver Dis (Hoboken) 2015;6:9–14. doi: 10.1002/cld.480. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Bonkovsky HL, Snow KK, Malet PF, Back-Madruga C, Fontana RJ, Sterling RK, Kulig CC, Di Bisceglie AM, Morgan TR, Dienstag JL, Ghany MG, Gretch DR HALT-C Trial Group. Health-related quality of life in patients with chronic hepatitis C and advanced fibrosis. J Hepatol. 2007;46:420–431. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2006.10.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.van der Plas SM, Hansen BE, de Boer JB, Stijnen T, Passchier J, de Man RA, Schalm SW. Generic and disease-specific health related quality of life in non-cirrhotic, cirrhotic and transplanted liver patients: a cross-sectional study. BMC Gastroenterol. 2003;3:33. doi: 10.1186/1471-230X-3-33. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Labenz C, Toenges G, Schattenberg JM, Nagel M, Huber Y, Marquardt JU, Galle PR, Wörns MA. Health-related quality of life in patients with compensated and decompensated liver cirrhosis. Eur J Intern Med. 2019;70:54–59. doi: 10.1016/j.ejim.2019.09.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Wong GW, Yeong T, Lawrence D, Yeoman AD, Verma S, Heneghan MA. Concurrent extrahepatic autoimmunity in autoimmune hepatitis: implications for diagnosis, clinical course and long-term outcomes. Liver Int. 2017;37:449–457. doi: 10.1111/liv.13236. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Dyson JK, Wong LL, Bigirumurame T, Hirschfield GM, Kendrick S, Oo YH, Lohse AW, Heneghan MA, Jones DEJ UK-AIH Consortium. Inequity of care provision and outcome disparity in autoimmune hepatitis in the United Kingdom. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2018;48:951–960. doi: 10.1111/apt.14968. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Pape S, Gevers TJG, Vrolijk JM, van Hoek B, Bouma G, van Nieuwkerk CMJ, Taubert R, Jaeckel E, Manns MP, Papp M, Sipeki N, Stickel F, Efe C, Ozaslan E, Purnak T, Nevens F, Kessener DJN, Kahraman A, Wedemeyer H, Hartl J, Schramm C, Lohse AW, Heneghan MA, Drenth JPH. High discontinuation rate of azathioprine in autoimmune hepatitis, independent of time of treatment initiation. Liver Int. 2020;40:2164–2171. doi: 10.1111/liv.14513. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Snijders RJALM, Pape S, Gevers TJG, Drenth JPH. Discontinuation rate of azathioprine. Liver Int. 2020;40:2878. doi: 10.1111/liv.14615. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Smith MA, Irving PM, Marinaki AM, Sanderson JD. Review article: malignancy on thiopurine treatment with special reference to inflammatory bowel disease. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2010;32:119–130. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2036.2010.04330.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Ngu JH, Gearry RB, Frampton CM, Stedman CA. Mortality and the risk of malignancy in autoimmune liver diseases: a population-based study in Canterbury, New Zealand. Hepatology. 2012;55:522–529. doi: 10.1002/hep.24743. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Janik MK, Wunsch E, Moskwa M, Raszeja-Wyszomirska J, Krawczyk M, Milkiewicz P. Depression in patients with autoimmune hepatitis: the need for detailed psychiatric assessment. Pol Arch Intern Med. 2019;129:645–647. doi: 10.20452/pamw.14898. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Rubin RR, Wadden TA, Bahnson JL, Blackburn GL, Brancati FL, Bray GA, Coday M, Crow SJ, Curtis JM, Dutton G, Egan C, Evans M, Ewing L, Faulconbridge L, Foreyt J, Gaussoin SA, Gregg EW, Hazuda HP, Hill JO, Horton ES, Hubbard VS, Jakicic JM, Jeffery RW, Johnson KC, Kahn SE, Knowler WC, Lang W, Lewis CE, Montez MG, Murillo A, Nathan DM, Patricio J, Peters A, Pi-Sunyer X, Pownall H, Rejeski WJ, Rosenthal RH, Ruelas V, Toledo K, Van Dorsten B, Vitolins M, Williamson D, Wing RR, Yanovski SZ, Zhang P Look AHEAD Research Group. Impact of intensive lifestyle intervention on depression and health-related quality of life in type 2 diabetes: the Look AHEAD Trial. Diabetes Care. 2014;37:1544–1553. doi: 10.2337/dc13-1928. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Jacoby A, Rannard A, Buck D, Bhala N, Newton JL, James OF, Jones DE. Development, validation, and evaluation of the PBC-40, a disease specific health related quality of life measure for primary biliary cirrhosis. Gut. 2005;54:1622–1629. doi: 10.1136/gut.2005.065862. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Broadbent DE, Cooper PF, FitzGerald P, Parkes KR. The Cognitive Failures Questionnaire (CFQ) and its correlates. Br J Clin Psychol. 1982;21:1–16. doi: 10.1111/j.2044-8260.1982.tb01421.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Younossi ZM, Guyatt G, Kiwi M, Boparai N, King D. Development of a disease specific questionnaire to measure health related quality of life in patients with chronic liver disease. Gut. 1999;45:295–300. doi: 10.1136/gut.45.2.295. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Lo C, Walsh A, Mikulincer M, Gagliese L, Zimmermann C, Rodin G. Measuring attachment security in patients with advanced cancer: psychometric properties of a modified and brief Experiences in Close Relationships scale. Psychooncology. 2009;18:490–499. doi: 10.1002/pon.1417. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Lloyd A, Pickard AS. The EQ-5D and the EuroQol Group. Value Health. 2019;22:21–22. doi: 10.1016/j.jval.2018.12.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Webster K, Cella D, Yost K. The Functional Assessment of Chronic Illness Therapy (FACIT) Measurement System: properties, applications, and interpretation. Health Qual Life Outcomes. 2003;1:79. doi: 10.1186/1477-7525-1-79. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Fisk JD, Ritvo PG, Ross L, Haase DA, Marrie TJ, Schlech WF. Measuring the functional impact of fatigue: initial validation of the fatigue impact scale. Clin Infect Dis. 1994;18 Suppl 1:S79–S83. doi: 10.1093/clinids/18.supplement_1.s79. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Spitzer RL, Kroenke K, Williams JB, Löwe B. A brief measure for assessing generalized anxiety disorder: the GAD-7. Arch Intern Med. 2006;166:1092–1097. doi: 10.1001/archinte.166.10.1092. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Zigmond AS, Snaith RP. The hospital anxiety and depression scale. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 1983;67:361–370. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0447.1983.tb09716.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.van der Plas SM, Hansen BE, de Boer JB, Stijnen T, Passchier J, de Man RA, Schalm SW. The Liver Disease Symptom Index 2.0; validation of a disease-specific questionnaire. Qual Life Res. 2004;13:1469–1481. doi: 10.1023/B:QURE.0000040797.17449.c0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Smets EM, Garssen B, Bonke B, De Haes JC. The Multidimensional Fatigue Inventory (MFI) psychometric qualities of an instrument to assess fatigue. J Psychosom Res. 1995;39:315–325. doi: 10.1016/0022-3999(94)00125-o. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Kos D, Kerckhofs E, Nagels G, D'Hooghe BD, Duquet W, Duportail M, Ketelaer P. Assessing fatigue in multiple sclerosis: Dutch modified fatigue impact scale. Acta Neurol Belg. 2003;103:185–191. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Kroenke K, Spitzer RL, Williams JB. The PHQ-9: validity of a brief depression severity measure. J Gen Intern Med. 2001;16:606–613. doi: 10.1046/j.1525-1497.2001.016009606.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Ware J Jr, Kosinski M, Keller SD. A 12-Item Short-Form Health Survey: construction of scales and preliminary tests of reliability and validity. Med Care. 1996;34:220–233. doi: 10.1097/00005650-199603000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Ware JE Jr, Sherbourne CD. The MOS 36-item short-form health survey (SF-36). I. Conceptual framework and item selection. Med Care. 1992;30:473–483. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Gaudry E, Vagg P, Spielberger CD. Validation of the State-Trait Distinction in Anxiety Research. Multivariate Behav Res. 1975;10:331–341. doi: 10.1207/s15327906mbr1003_6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Reilly MC, Zbrozek AS, Dukes EM. The validity and reproducibility of a work productivity and activity impairment instrument. Pharmacoeconomics. 1993;4:353–365. doi: 10.2165/00019053-199304050-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]