Abstract

Background

Impulsive processes driving eating behaviour can often undermine peoples’ attempts to change their behaviour, lose weight and maintain weight loss.

Aim

To develop an impulse management intervention to support weight loss in adults.

Methods

Intervention Mapping (IM) was used to systematically develop the “ImpulsePal” intervention. The development involved: (1) a needs assessment including a qualitative study, Patient and Public advisory group and expert group consultations, and a systematic review of impulse management techniques; (2) specification of performance objectives, determinants, and change objectives; (3) selection of intervention strategies (mapping of change techniques to the determinants of change); (4) creation of programme materials; (5) specification of adoption and implementation plans; (6) devising an evaluation plan.

Results

Application of the IM Protocol resulted in a smartphone app that could support reductions in unhealthy (energy dense) food consumption, overeating, and alcoholic and sugary drink consumption. ImpulsePal includes inhibition training, mindfulness techniques, implementation intentions (if-then planning), visuospatial loading, use of physical activity for craving management, and context-specific reminders. An “Emergency Button” was also included to provide access to in-the-moment support when temptation is strong.

Conclusions

ImpulsePal is a novel, theory- and evidence-informed, person-centred app that aims to support impulse management for healthier eating. Intervention Mapping facilitated the incorporation of app components that are practical operationalisations of change techniques targeting our specific change objectives and their associated theoretical determinants. Using IM enabled transparency and provided a clear framework for evaluation, and enhances replicability and the potential of the intervention to accomplish the desired outcome of facilitating weight loss through dietary change.

Keywords: Intervention mapping, weight loss, eHealth, mhealth, obesity, digital behaviour change intervention, implicit process, automatic process, dual-process

Background

Tackling obesity remains a public health priority. Excess weight has adverse consequences for health1,2 and wellbeing3,4 and has been associated with lowered life expectancy. 5 With two in three adults in the UK and western world living with overweight or obesity, it is one of the most costly preventable social burdens alongside smoking and excessive alcohol consumption. 6 The World Health Organisation defines overweight and obesity as excessive fat accumulation that may impair health 7 and a person's excess weight status is still commonly classified using the Body Mass Index (BMI).

This obesity epidemic is complex and multi-factorial, but a crucial contributor has been the consumption of excess energy without a response in energy expenditure. 8 Many people fail to meet the daily recommendations for healthy dietary intake 9 and one major risk factor contributing to the increased energy intake in the population, is the frequent consumption of (high) energy-dense food and drink items8,10–13. Following the British Nutrition Foundation, energy density refers to the amount of energy (i.e. calories) per gram of food. To achieve the same energy intake, energy-dense foods (e.g. food high in fat and sugar) need to be eaten in smaller volumes than those that are less energy-dense. 14 Energy-dense food and drinks that have been shown to be associated with increased energy intake include fast food,15,16 snacks and sweets,17,18 sugary soft-drinks,19–22 and alcoholic drinks.23,24 Moreover, experimental studies have shown that eating rate and energy density have independent yet additive effects on overeating (eg., 25 ). Thus, food items that are consumed quickly such as fast food, snacks, sugary drinks, which are generally consumed in between meals while “on-the-go”, are considered key contributors to excess energy intake and are therefore important targets for change in weight management interventions.

The modern environment is sometimes referred to as “obesogenic” with cues and temptations 26 ever-present through increased food availability, food outlets, and 24/7 marketing and advertising. These cues trigger excess energy intake through increased eating opportunities and portion sizes27–29 and contribute to the rising obesity prevalence.10,30,31 However, there are differences in how susceptible people are to cues32,33 and in the extent to which cues capture attention,34,35 motivate towards immediate rewards, and trigger food consumption. 36 Genetic factors explain 40–70% of individual differences in BMI, 37 and these effects are partially mediated by differences in self-control towards food (i.e. disinhibited eating).38–40 Thus ones genetic make up could be making it more difficult to resist the food temptations in our environment. Individual-level interventions to alter behaviour should support people to manage and override their, in part genetic, responses to the obesogenic environment.

To maximise the efficacy of behaviour change interventions, the application of appropriate theory is advocated as an integral step in intervention development and evaluation.41,42 A systematic review of reviews 43 highlighted that self-directed weight management interventions have been predominantly based on social-cognitive and motivational theories (e.g. Theory of Planned Behaviour 44 and the Transtheoretical Model 45 ). The common assumption in these theories is that behavioural action is determined by deliberative, intentional processes. However, despite strong intentions to lose or maintain weight, people still commonly fail to lose weight, or subsequently regain weight that had been lost (e.g. 46 ). Similarly, research has shown that though many people intend to cut down and reduce their snack consumption, strong habits can prevent them from achieving that goal.47,48 This finding is supported by literature showing that dieting intentions alone are often not sufficiently effective for regulating consumption behaviour.49–51

More appropriate theoretical insights for weight management intervention development may come from recent advances in “dual-process” approaches to human behaviour such as the Reflective Impulsive Model( 52 ), the Temporal Self-Regulation Theory (TST 53 ) and the Context, Executive, and Operating Systems model (CEOS; 54 ). These approaches propose that in addition to deliberative intentional determinants, behaviour is influenced by unconscious, swift-acting, automatic, impulsive processes which are triggered by situational cues. The influence of impulsive processes on behaviour is supported by research showing that implicit attitudes and beliefs are positively correlated with food choice and eating behaviour. 55 Such processes often reflect deeply ingrained behavioural habits which are resistant to change. However, recent research suggests that these processes may be modifiable.56,57 Consequently, research to identify effective strategies for addressing the impulsive determinants of behaviour to improve health outcomes, has increasingly been advocated.58,59

It is not only important to identify or develop, effective weight management interventions, but also to ensure they are scalable and cost-effective. One way of maximising scalability is offering self-directed interventions 43 using the internet and digital devices. For example, app-based interventions to improve diet, physical activity, and sedentary behaviour have shown modest evidence for the efficacy for non-communicable disease prevention and provide the opportunity to intervene or provide support in the context of real-life situations where real-time decision making occurs. 60 In addition to its scalability, using digital technology as a platform for intervention delivery has the potential of minimising variability in delivery fidelity (i.e. whether the intervention is delivered as intended). Such interventions using the internet and digital technology for health have been referred to as ‘eHealth’ interventions. 61 However, more recently, and specific to lifestyle interventions, the term digital behaviour change interventions (DBCIs) has emerged, which typically refer to the use of websites and smartphones as intervention delivery platforms. 62

The aim of this paper is to describe the systematic development of a self-delivered smartphone app-based weight management intervention that targets impulsive processes to improve self-regulation of eating behaviour, with a view to facilitating weight loss. However, it is important to note that decisions regarding the delivery platform and theoretical underpinnings were informed by the needs assessment activities as described below.

Methods and results

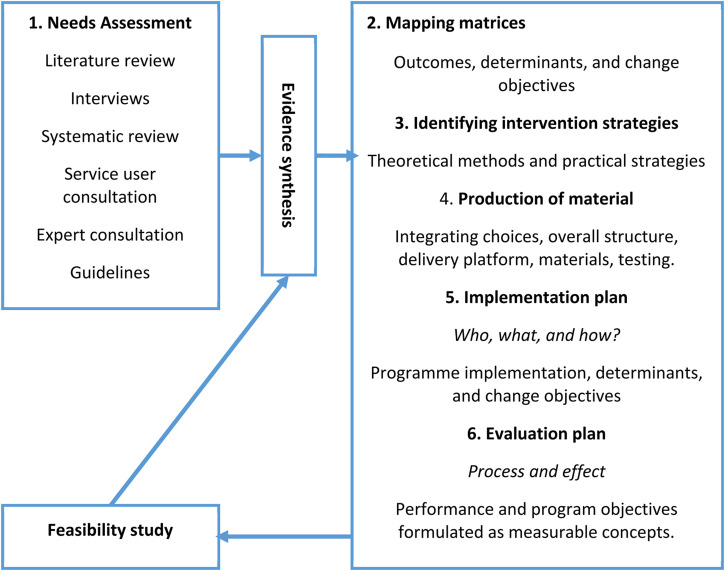

An overview of the development process is provided in Figure 1. We used Intervention Mapping (IM), 63 which is a well-established and widely used framework for developing health behaviour change interventions (e.g.64–68) and had been used previously by members of the research team.67,69 The IM protocol provides a structured approach to making intervention design decisions that are based on theory, evidence, and an appropriate range of stakeholder perspectives. The protocol comprises six consecutive yet iterative steps: (1) needs assessment; (2) identification of performance objectives and change objectives; (3) selection of theory-based methods and practical strategies; (4) development of intervention programme materials; (5) development of an adoption and implementation plan; and (6) development of an evaluation plan. Reporting of methods and results in the following section is structured in line with these six steps to describe work undertaken between September 2012 (beginning of Needs Assessment) to September 2015 (finalisation of evaluation protocol).

Figure 1.

Intervention development process.

Needs assessment – step 1

Step 1: methods

The main aims of the needs assessment were to specify the programme outcome (core output Step 1) and to identify the potential targets for behaviour change, their associated modifiable, determinants, and an appropriate platform for intervention delivery, to help inform Steps 2 and 3 respectively.

Intervention development group

A multi-disciplinary intervention development group (n = 8) comprising behaviour change experts (4), neuro-cognitive psychologists (2), and app programmers (2) was assembled to guide the process. The app programmers joined the group after early work suggested an app-based delivery platform would be most suitable. The team was led by a behavioural scientist and discussed weight management, and barriers and facilitators to weight management, based on data from various sources:

A qualitative study to explore perceptions of and experiences with existing web-based weight management interventions among general practice patients with a BMI of over 25 kg/m2 who indicated a desire to lose weight. 70

Patient and public advisory group (n = 10) and expert group (n = 10) consultations. Members from an existing local group advising on weight loss and weight loss maintenance were invited to a specific consultation for this project. A separate group of experts (n = 10) were invited through network emails and consisted of people with expertise in behaviour change theory, change techniques, eHealth, and the development of weight management and other behaviour change interventions. Both consultations discussed facilitators and barriers to the reduction of unhealthy eating behaviours identified in the literature and qualitative study, and whether there was anything missing. They also focused on potential strategies to facilitate impulse management and prioritising potential targets for change to help inform Step 3. These groups did not comprise participants taking part in the research. 71

an informal review of the literature was undertaken on (i) factors affecting eating behaviour, (ii) factors influencing engagement with digital interventions, and (iii) current national guidance for weight management interventions.

a de novo systematic review of techniques targeting impulsive processes that drive eating behaviour, to explore if and how such determinants might be modifiable. 72

Synthesis of needs assessment data

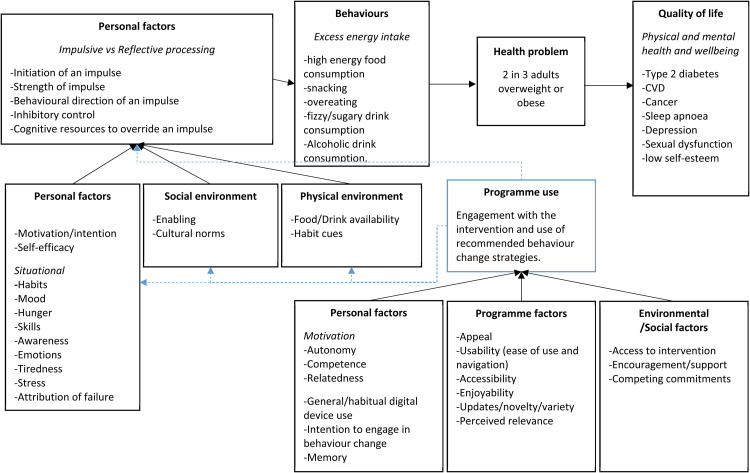

To synthesise the evidence and recommendations from the above sources, summary reports and findings were thematically analysed. The focus was on specifying the overarching programme outcome and identifying (a) potential performance objectives, (b) their associated modifiable determinants, and (c) potential strategies. Using triangulation, 73 the sources were assessed for agreement, disagreement, or silence in relation to the identified potential performance objectives (See Table S1 in the Additional File). Areas of disagreement were discussed in the intervention development group to identify the causes of disagreement and to seek resolution. The resulting themes and categories were organised into a logic model of the problem (See Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Logic model of the problem and impulsePal.

Step 1: results

Specification of the programme outcome

Overall, the intervention development group agreed that the programme's health outcome should be weight loss and prevention of weight (re)gain in adults who are at increased risk of health conditions associated with excess fat accumulation (i.e. a BMI of 25 kg/m2 and over for a white European population, or 22 kg/m2 and over for African-Caribbean / Black Caribbean population). Based on literature linking dietary behaviours to weight gain (See Background) and the continued struggle to change dietary behaviour even with available support as reported in the qualitative interviews, 70 reduction in dietary intake was adopted as the overall behavioural programme outcome.

Behaviours leading to excess energy intake

Based on the agreement among all sources, including literature presented above, the intervention development group agreed that to support weight management, key behavioural risk factors to be addressed were (a) unplanned eating and/or drinking (i.e. snacking), (b) type of food or drink consumed (e.g. palatable high energy food and drink), and (c) amount consumed in one sitting (i.e. overeating). The expert consultation and research literature also highlighted that alcoholic drinks are not only high in energy, but their consumption also acts as a potential facilitator of overeating and unplanned snacking and is, therefore, a risk factor for excessive energy intake (e.g. 23 ).

Impulsive processes

Early discussions with the intervention development group based on theory52,54,74 and research literature cited above, acknowledged the importance of managing impulsive processes that facilitate excess energy intake. These processes can result in mindless eating, including making unhealthy food choices and overeating, particularly if there are deficits in executive functioning, or if self-control resources are depleted (e.g.33,75–77). The strength of the impulse to be controlled also influences the behavioural outcome. The stronger the impulse, the greater the likelihood of self-regulation failure. 78 In addition, there are factors that affect whether an impulse is triggered in the first place such as food availability, portion size 79 ), habit cues, 80 and other situational cues. 81 This need to address impulsive processes that guide behaviour also came across strongly in the consultation groups and the qualitative study. 70 Both members of the advisory group and participants in the qualitative study highlighted that they felt that current interventions were not providing support to deal with eating too much in one go (e.g. portion size) and temptation resistance for unhealthy snacking as these were often experienced as automatic, habitual, or mindless behaviours. The systematic review identified various techniques addressing impulsive processes working through different mechanisms. For example, impulsive processes could be modified directly, by changing their initiation, strength, or motivational direction. However, they may also be overridden or otherwise managed by cognitive resources. 72 Such processes may therefore indeed be modifiable.

Situational cues

Impulsive processes are proposed to guide behaviour based on hedonic reward-based motivations or habitual routines and are triggered and maintained by situational cues, such as tempting stimuli.74,82 The literature (See Background), consultation groups, and intervention development group considered the modern obesogenic environment with its abundance of eating-related situational cues, to be a crucial influence on the initiation and maintenance of food-related impulses. Moreover, elements of the situation may result in difficulty in overriding the impulsive processes. For example, in situations when resources required for the reflective processes to run in order to be able to override the impulsive processes, are depleted. These include times of stress, tiredness, when engaged in multiple tasks (busy), and when trying to regulate behaviour or emotions (e.g. quitting smoking or resisting food temptations or trying not to get angry).83,84 When these resources are depleted people are more likely to give into food temptation and consume excess energy.77,85,86

The consultation groups also stressed that social situations are considered to be barriers to healthier eating, particularly where unhealthy food or drink consumption frequently occurs (e.g. celebrations). In such situations, individuals are not only confronted with food cues in the environment but are also having to deal with social norms and pressures. The consultation groups expressed there was a lack of confidence to resist such social influence and lack of motivation to adhere to healthier behaviours in these contexts.

In-the-moment accessibility

It was suggested that as impulsive processes drive behaviour on a moment-to-moment basis, any intervention targeting such processes related to eating behaviour would benefit from being accessible at any time. However, the delivery methods of traditional weight management interventions (e.g. group-based, face-to-face) do not allow for the provision of in-the-moment intervention. The intervention development group highlighted smartphone technology as a promising delivery platform as people tend to have their phone with them most of the time and look at it frequently.87–89 This pattern of smartphone use means that the intervention could be accessed whenever and wherever the user requires it, allowing for the provision of the desired “in-the-moment support”. App-based delivery was also supported by the consultation groups and qualitative study in which some participants mentioned this would offer a solution to overcome barriers to accessing and engaging with weight management interventions. 70 Aside from being accessible, potentially cost-effective and scalable, mobile technologies such as smartphones have sensors which could identify when a person may be most vulnerable to influences that lead to unhealthy behaviours (e.g. Global Positioning System (GPS)). Moreover, digital interventions have been shown to be effective in modifying a range of health behaviours. 90

Programme engagement

At the time this needs assessment had been conducted, level of engagement with an intervention had been positively linked to physical health outcomes.91–93 However, low-use of internet-based interventions was (and continues to be) a challenge in many behavioural domains (e.g. eating, smoking, condom use, alcohol consumption 94 ). The qualitative study conducted as part of this needs assessment 70 identified a range of facilitators of, and barriers to, using web-based weight management interventions such as the appeal of the interface, the effort required to engage with the tool and strategies, usability, choice of information and strategies available, ease of access to the intervention, general internet device use, novelty and variety, perceived relevance of target audience, ongoing motivation to change and motivation to engage with the intervention. Similar influences on engagement were found in a related qualitative study with a younger community-based sample focused specifically on app-based interventions. 95

Specification of outcomes, performance objectives and change objectives – step 2

Step 2: methods

The second step involved the detailed specification of who and what needed to change, and how that would lead to the programme outcome being achieved. The potential performance objectives identified in the needs assessment (above) were examined by the intervention development group and the patient and public advisory group, to assess which objectives to prioritise. The prioritisation task involved individually rating the top three most important (and achievable) objectives. The performance objectives were formulated in a measurable way and were then further scrutinised, to identify the specific impulsive (and other) determinants related to that behavioural objective. This task included reflecting on potentially modifiable determinants identified in Step 1. This stage in the mapping process required that change objectives were selected and clear specifications were made, to reflect actual changes that needed to occur in the modifiable determinants for the performance objective to be achieved. This specification task involved creating a matrix where performance objectives were cross-referenced with modifiable determinants and change objectives were formulated in the intersecting cells (see Table S2 in the Additional File).

Step 2: results

The prioritisation task highlighted that, from the advisory group perspective, reductions in overeating (i.e. “Individual reduces frequency of overeating episodes (over a 28 day period)”) and unhealthy food choices were the most important achievable objectives. Resisting unhealthy snacks (i.e. high calorie but low nutritional value) appeared second to least frequently in the “top three”s. In consultation with the intervention development group and as a result of further discussion with the advisory group, this was later rephrased to combine with reducing unhealthy food choices (i.e. “Individual reduces weekly frequency of unhealthy snack/food consumption”). Sugary, fizzy, and alcoholic drink consumption was reported in the qualitative study as a problem, but had not initially been proposed to the advisory group as a separate standalone objective. However, the research literature provided a strong rationale for minimising the consumption of sugary and alcoholic drink consumption (e.g.21,23). Therefore, the intervention development group included this as a specific performance objective (i.e. “Individual reduces weekly fizzy drink consumption.” and “Individual reduces weekly alcoholic drink consumption.”). Finally, to minimise barriers to uptake and use of the intervention and its strategies, programme engagement was specified from the outset as a key performance objective (i.e. “Individual effectively engages with the intervention).

The next task in Step 2 was to specify how these performance objectives were to be achieved. Table 1 shows selected examples of change objectives for one of the performance objectives cross-referenced with a selection of the associated determinants. The full Intervention Map, including all other objectives, can be seen in Additional file 1.

Table 1.

Example performance objective cross-referenced to determinants.

| Determinants | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Performance objectives | Initiation of impulse | Strength of impulse | Inhibitory control |

| PO1. Individual reduces weekly frequency of unhealthy snack/food consumption |

I.I. 1. Prevent initiation of impulse to eat unhealthy snack /food. | S.I. 1. Reduce strength of impulse to eat unhealthy snack /food. | I.C.1. Engage inhibitory control to inhibit behavioural responses towards unhealthy snack /food. |

| I.I. 2. Initiate impulse to engage in alternative /healthier action. | S.I. 2. Engage strategies to cope with the strength of an impulse to eat unhealthy food /snack without eating. | ||

| I.I. 3. Identify personal cues /triggers that initiate impulses to eat unhealthy snacks and food. | S.I.3 Identify where strong impulses /cravings to eat unhealthy snack /food may occur. | ||

Selection of theory-based methods and practical strategies – step 3

Step 3: methods

The third step of IM involves choosing intervention techniques to influence the change objectives. For each determinant of each change objective, change techniques likely to alter the determinant were selected. 63 The selection of techniques drew on a de novo systematic review conducted during the needs assessment to identify impulse management techniques 72 focusing on techniques which showed promising evidence for change in weight, eating behaviour, and /or craving strength or frequency. A framework of theoretical behaviour change processes (the Theoretical Domains Framework), 96 and a taxonomy of 93 behaviour change techniques 97 were also consulted. Techniques were selected based on the evidence for the techniques in their ability to modify specific determinants (as identified in the systematic review 72 and subsequent literature98–100), the expert knowledge of the intervention development group, and the possibility of delivering the technique via a smartphone app. To address the final performance objective: “Individual effectively engages with the intervention”, reviews on strategies and features to improve engagement101–103 and literature on gamification 104 were consulted.

Step 3: results

Six key impulse management techniques were selected from the systematic review; 72 (a) visuospatial loading (e.g.105,106), (b) inhibition training (e.g.98,99,107), (c) implementation intentions,107,108 (d) mindfulness-based strategy (e.g. acceptance109,110), (e) physical activity,111,112 and (f) situational priming.81,113 These techniques were selected on the basis of the quality of (1) the evidence identified in the systematic review, 72 (2) subsequently available evidence (i.e. published following completion of the systematic review e.g.98–100), and 3 evidence outside of the scope of our de novo review.81,113–116

To optimise engagement, the intervention development group decided to include persuasive system design features (i.e. reminders) and interactive elements. The intervention is also required to foster a sense of autonomy, relatedness, and competence to enhance motivation to engage with the intervention, through offering choice, using language and examples that were relatable and conveyed empathy, and incorporating a navigational flow and presentation that is intuitive and similar to other frequently used apps.

How the selected intervention techniques and strategies relate to each specific change objectives and their determinants is illustrated in the intervention map (Table S2). We describe our practical applications of these selected techniques below in Step 4.

Creating the programme – step 4

Step 4: methods

The next step in the IM process was to create an organised, structured programme. This step entailed defining the scope and the limitations of the intervention, translating the change techniques selected and specified in step 3 (see above) into specific programme materials and identifying appropriate and feasible delivery methods.

The intervention development group discussed and guided the scope, selection of operational strategies, the feasibility of delivery via a smartphone app, and sequencing of the intervention components. Discussions with the app developers focussed on the practicalities of each technique and their form within the intervention. Members from the public and patient advisory group (n = 6) provided initial feedback on the textual content of a prototype app, the clarity of the written instructions, the flow of navigation, and any technical issues that arose. Usability and navigational issues were further assessed via individual “thinking aloud” testing sessions with two of the available advisory group members, during which they were asked to continuously verbalise their thoughts as they moved through the prototype app. Any issues or misunderstandings were noted and addressed prior to developing the first fully functional (Android) version of the ImpulsePal app. This section describes the resulting app programme in detail following the Template for Intervention Description and Replication (TIDieR) checklist. 117 For a briefer intervention description, please see. 118

Step 4: results

The ImpulsePal app-based intervention was designed to be entirely self-delivered and interactive, allowing users to identify and specify personal barriers to unhealthy eating, identify strategies to overcome these barriers, and to track the usefulness of any impulse management techniques that they tried. Users register with a username and password. On successful registration, an additional thumbnail is added to users’ smartphone home screen which functions as the “Emergency Button”. Finally, users are presented with the app's welcome page, which provides information about what eating-related impulses are, when they might be triggered, and how they might be perceived (e.g. temptation, craving, desire). It also provides information about how users can identify their own triggers and a brief introduction to the app: “This app will help you manage your impulses to avoid unhealthy eating. You will find a variety of tips and tricks from brain training to defence strategies such as if-then planning which you can apply in the heat of temptation.” The introduction is followed by a page asking users about their main motivation for losing weight and their key struggles in weight loss. Once users have entered this information, they are directed to the main menu. The main menu (See Figure 3) acts as the home screen for the app and displays navigational buttons to return to the information about the app, the motivations page, and self-monitoring statistics on the user's progress with developing “temptation resistance”. This main menu also displays navigational buttons to the five key components of the app: (1) Brain Training, (2) My Plan, (3) Urge Surfing, (4) Danger Zones, and (5) Emergency Button. These are the operationalisations (practical applications) of the evidence-based techniques selected in Step 3 and are described in turn below. Issues identified following feedback from the public and patient advisory group on the prototypes is summarised in Table S3 in the Additional file which highlights the actions taken.

Figure 3.

The impulsePal App.

Brain training operationalises the inhibition training technique as used by van Koningsbruggen and Veling and colleagues.107,119 This technique, as described in earlier literature, had been proposed to strengthen inhibitory control but it appears to work via reductions in impulse strength through devaluation of the trained foods and potentially the training of an automatic stopping association. 120 In the instructions, users are informed that the brain training will help them inhibit motor impulses that are triggered when they see food. This training involves a Go/No-go task98,99,107,119 and is presented as a game which provides feedback in the form of scores. During the game, users are presented with images of unhealthy foods and neutral images. Only one image is presented on the screen at any given time and 100 ms following presentation of an image a Go or No-go cue is presented. These cues are displayed as a green “Go” sign and red “Stop” sign, with neutral images consistently paired with a Go sign and unhealthy food images with the Stop sign. When a green Go sign appears on the screen, users need to touch the side of the screen where the image appeared. They are instructed to withhold touching the screen when a red Stop sign appears. Images are presented at random and before the next image is presented, users are provided with performance feedback, with points given based on their correct response and reaction time. Two points are deducted for an incorrect response. All users are encouraged to play the 5-min brain training game three times per week for four weeks and are prompted to engage with the feature via in-app reminders, if the game has not been played on two consecutive days during the first four weeks.

My Plan operationalises implementation intentions in the form of if-then plans. 108 This component presents users with a form where plans can be selected or created. Users are instructed to keep their overall goal in mind and to think of situations that could prevent them from achieving their goal. They are offered existing if-then plans which include common situations where people may struggle with eating-related impulses (“ifs”) and responses to deal with those situations (“thens”), which were derived from the two consultation workshops and the qualitative study. In addition, users are also provided with the option to create their own if-then plans. Multiple if-then plans and amendments can be made and saved at any time.

Urge Surfing 121 was selected as it aims to help users deal with in-the-moment temptations and cravings through acceptance of thoughts and feelings. This technique is the practical application of the mindfulness-based strategies selected in Step 3. This component provides users with information on how and when urge-surfing can be used and textual instructions which follow the steps: Stop, Take a breath, Observe and imagine, and Practice and proceed. The instructions encourage users to imagine cravings to be like waves which may build over time, but eventually subside and pass. Users are also encouraged to practice this technique in the absence of a craving.

Danger Zones makes use of smartphones’ location function (GPS) to enable users to create location and time specific (situational) cues for themselves (thereby operationalising the cueing or priming technique 81 ). This component requires users to identify their own “high-risk situations” for unhealthy eating that are location and time specific. Once a location has been selected on the map, users can link the particular location to their own specified goal for the location, which requires identifying the problem and problem-solving in advance. Whenever the smartphone location service detects that the smartphone has entered the selected location, the app sends a notification which is presented in the notification bar. This notification reminds users of their specified goal for that particular location. The Danger Zones component also allows users to select “time boundaries” to more precisely define the high-risk situation, making it context specific. For example, if the location is only ever a personal trigger for unhealthy behaviour during lunch hours, then a notification outside these hours would not be helpful.

The Emergency button is a separate function of the app which enables users to access strategies to deal with the craving “in-the-moment”, and (following such events) to record which strategy was chosen and how well the strategy worked. Users are encouraged to use the emergency button whenever they experience a strong craving or temptation. On pressing the emergency button, users are presented with a message congratulating them on putting their impulse on hold. The background of this screen consists of dynamic visual noise in the form of television static, which provides the visuospatial loading. 105 The next screen displays options for accessing My Plan (if-then planning), brain training (inhibition training), or urge surfing (mindfulness-based strategy) to choose from. Fifteen minutes after an emergency button event (e.g. when a user has indicated that a craving or temptation is particularly strong and that they required extra help), the app sends a notification that asks users about the strength of their craving at the time. Users are prompted to respond by rating their craving from 0–100 using a slider displayed on a visual analogue scale ranging from “very weak” to “extreme” craving. The craving scale is followed by a question about whether they were (a) successful, (b) partly or mostly successful or (c) not successful in resisting the urge to eat. The answer to this question is recorded and followed up with an associated message (e.g. congratulatory message or a message normalising a lapse and to encourage learning from the experience and continuing to practice). The statistics page supports self-monitoring of “temptation resistance” and is found in the main menu. This statistics page displays the number of uses of the emergency button for the week and in total. It also displays the success rate for resisting cravings or temptations in relation to their usage of the if-then plans, brain training, and urge surfing following the emergency button events. Users are encouraged to try all techniques and use their statistics to review which techniques are most useful for them personally.

Adoption and implementation plan – step 5

Step 5: methods

In this penultimate step, an adoption and implementation plan was created. This step was informed by literature about factors influencing digital technology uptake and use. However, addressing challenges around adoption and implementation also involved including strategies within the intervention to facilitate sustained engagement which had already been addressed (See Steps 2, 3, and 4). The intervention does not require a programme facilitator, therefore no facilitator training is required. However, because of this, the intervention needed to be very clear and self-explanatory. These issues were addressed in Step 4. Thus, Step 5 primarily focused on how ImpulsePal could be distributed.

Step 5: results

The UK user base for smartphones reached 81% of the population in 2016 (91% among 18–44 year-olds) and smartphone use continues to permeate daily life. 122 Thus, the potential reach of a smartphone-based behaviour change intervention is substantial. However, there are various facilitators and barriers to digital weight management intervention uptake and engagement.70,95 These were taken into account throughout development (See Steps 2, 3, and 4).

In relation to distribution and uptake, ImpulsePal will be made available from commonly used app stores. We may issue press releases to raise awareness. Moreover, local organisations with whom we are already working and have requested the use of ImpulsePal, will be encouraged to refer people. Findings from a longitudinal qualitative evaluation of a national digital health innovation programme in the UK 123 also highlighted that accreditation and clinical endorsement may strongly influence the adoption and implementation of digital technologies. To facilitate uptake in the longer term, we therefore plan to get the ImpulsePal app evaluated within the NHS following their guidance in the Mobile Health space for developers 124 to get ImpulsePal validated, safety checked, and ultimately hosted on the NHS Digital Health Apps Library. 125

Evaluation plan – step 6

Step 6: methods

The final step of the IM process involved creating an appropriate evaluation plan. The transparent documenting of a behaviour change intervention enabled by the Intervention Mapping process, facilitates this. The Logic Model (Figure 2) and detailed Intervention Map (See Table S2) provide the outcomes and processes of interest and therefore inform the design of any evaluation of the intervention.

Step 6: results

The initial evaluation of the intervention was a feasibility study incorporating two cycles of action-research to refine the intervention in close collaboration with its intended users. The measures selected map onto the intervention's effects on the health-related outcome (objective weight change), the programme objectives (self-reported eating and drinking behaviour using a food frequency questionnaire, 126 questions relating to overeating occurrences, 127 and measures assessing engagement - objectively assessed through app usage statistics and explored in semi-structured interviews). The feasibility study also explored the mechanisms of action through semi-structured interviews and questionnaires tapping into intermediary outcomes such as impulsiveness, 128 reactivity to the food environment and situational cues,126,129 strength of cravings and temptations (assessed using an event-related ecological momentary assessment requesting a rating on a VAS scale), and self-efficacy in managing situations where impulse triggers are commonly present. The design and methods of this feasibility evaluation and its findings are reported in detail elsewhere 118 and showed that both the intervention and the trial procedures are feasible to implement and that they are acceptable to the participants. The next phase of the evaluation is to progress to a fully powered randomised controlled trial (RCT) to investigate the effectiveness of the intervention and further process evaluation to investigate the mechanisms of action.

Discussion

This paper describes the systematic development of a smartphone app-based weight management intervention, ImpulsePal. To our knowledge, ImpulsePal is one of few apps to date130,131 designed to target impulsive processes in order to facilitate dietary behaviour change. The app was iteratively developed using the Intervention Mapping (IM) protocol 63 and offers a multipronged approach to targeting impulsive processes. IM enabled us to consider behaviour change theory, incorporate evidence-based change techniques, and co-create the app-based intervention with potential end-users and experts in a systematic way.

The importance of providing clarity and transparency in the development and description of an intervention is increasingly recognised (e.g.132–134) and several studies have been published in recent years which have adopted similar, comprehensive and structured approaches to intervention development and this is a crucial advancement in the field (e.g..64,135,136) Such a systematic and comprehensive approach to development and evaluation, as well as clear reporting of intervention content is particulary unusual for app-based behaviour change interventions. 137 Although the process is time-consuming and can be resource- intensive, its systematic approach ensured that all ImpulsePal components were practical translations of change techniques that targeted our specific change objectives and thus the associated determinants of the behavioural targets. Using this approach enhanced transparency, provided a clear framework for evaluation and process evaluation, and facilitates replicability. It also maximises the potential of the intervention to accomplish the desired outcome of weight loss.

Unlike most other digital weight loss interventions, 43 ImpulsePal is designed to address both impulsive and reflective processes. As well as regularly used features such as action-planning and self-regulation tools, 138 ImpulsePal provides in-the-moment support where temptations cause difficulty for successful self-regulation 78 and offers evidence-based strategies to manage impulsive and automatic behaviour.52,58,74 This approach acknowledges that good intentions are not always enough to prevent lapses and therefore that additional support may be required at crucial times. A smartphone-app delivery platform allows the provision of 24 h easy access to the intervention and the inclusion of an “Emergency Button” feature emphasises this element of the programme.

Strengths and limitations

This is one of few studies to describe in detail the systematic development of a smartphone-app based behaviour change intervention and offers a comprehensive description of the intervention according to the TIDieR check list. 117 It used rigorous methods to move from a sound theory and evidence base to practical intervention techniques and strategies, whilst incorporating strong patient and public involvement to ensure the perspectives of the target population were accounted for.41,139 Although the intervention has been developed in a UK context, it may be suitable (with proper translation and adaptation) for use in a wide range of countries and cultures. There is no evidence that impulsive processes are culturally patterned (although triggers may be culturally specific, the process itself is not), and the app does not include any country-specific information content. One element that would particularly require cultural adaptation is the Go/No-go task which includes pictures of common foods eaten in the UK.

Various frameworks are available for intervention developers (for a recent overview see 140 ) to guide the development process such as the Medical Research Council (MRC) Framework for developing and evaluating complex interventions, 141 the behaviour change wheel, 142 and IM. 63 Although, the MRC Framework 42 recommends that interventions are described comprehensively and that the mechanisms by which they work are made explicit throughout their development, this framework does not offer detailed guidance on how to achieve this. The behaviour change wheel, is a well-established and often-cited method for intervention development which uses the COM-B model of behaviour (Capacity, Opportunity, Motivation, Behaviour) to guide the process. However, this framework is limited to a single unifying theory whereas Intervention Mapping allows developers to draw on a range of theoretical approaches depending on the behavioural targets and their modifiable determinants identified in the needs assessment, thus making this approach more specific to the behaviour, population, and context in which the intervention is to be implemented. Although not published when development of the intervention commenced, the approach taken was broadly in line with the more recent guidance for the development of digital behaviour change interventions62,143 and has integrated elements that have been recommended in the Person-Based Approach 139 such as in-depth qualitative research at various stages of development (i.e. semi-structured interviews Stage 1 and think-aloud interviews Stage 4).

Several limitations need to be acknowledged regarding the use of IM. Firstly, although one of the core strengths of IM is its iterative and comprehensive nature which ensures a thorough development process grounded in theory and evidence, on the flipside, as has been reported in other development studies using IM,64,144 it is a time-consuming and resource-intensive process. Secondly, definitions of what constitutes a performance objective, a determinant or behaviour change technique can become blurred. Using a behaviour change technique can be considered a behaviour in itself and could, therefore, be mapped with its own determinants. This can make it difficult to distinguish where mapping of the active ingredients in the intervention ends, and considerations regarding receipt and enactment (i.e. appropriate implementation of the techniques by individuals) begin.

Despite the systematic steps and transparency enabled by the IM protocol, it is probable that a different intervention development group using the same methods would produce a different intervention. Throughout the process, decisions were based on available evidence, appropriate expertise (behaviour change experts, app developers, neuroscientists), experience (Patient and Public advisory group), and practical considerations. Thus, intervention development is a function of these variables and the interaction between those involved in collective decision-making at a particular point in time. We attempted to document and justify decisions made throughout the process as much as possible using reports, synthesis tables, and triangulation, however, a tool has recently been developed to aid the documentation of justifications and decisions during intervention development enabling an even clearer documentation trail of the process.145,146

It is also important to acknowledge the limitations of the ImpulsePal intervention. Firstly, although some of the techniques do not require motivation to be effective (e.g. Go/No-go task 107 ) the use of the strategies by an individual may still be influenced by their motivation to lose weight and therefore willingness to change. 95 Though strategies have been incorporated to increase motivation to engage with the intervention among those who want to lose weight,70,147 this app may not be appropriate for those who are at risk of weight-related health issues but are not motivated to manage their weight through dietary change. Although this development study accommodates for the perspectives of the target population throughout the development stages, enabled by the Patient and Public advisory group, qualitative study and qualitative literature, this development work would have benefitted from following the Person-Based Approach139,148 which was published after work reported here had already been completed. The person-based approach complements theory and evidence-based approaches and uses in-depth qualitative research to accommodate for the target user's perspectives to optimise the acceptability of and engagement with the intervention platform and behaviour change strategies.

Secondly, the technological landscape is ever-changing. The intervention may currently be appropriate and fully functional, but it is important that it evolves with technological advances and the way people engage with technology, when required. Finally, smartphone apps generally have short life spans. Of 26,176 apps which had peak monthly users in 2011, 2012, and 2013, half lost 50% of their peak number of users within 3-months after reaching that peak usage, although apps used for news and health lose users at a slower rate. 149 However, ImpulsePal has incorporated techniques which do not rely on app use once initially learnt. Moreover, our intention is to support people in getting better at managing the impulsive processes involved in eating behaviour as opposed to enticing the app user to rely solely on the intervention.

Future directions

Further research is now needed to assess the effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of the ImpulsePal intervention. A feasibility randomised controlled trial showed that both the intervention and trial are feasible to implement and acceptable to participants. 118 Funding will now be sought for a fully-powered randomised controlled trial. Beyond this, further research should include assessment of the effectiveness of the intervention on weight loss maintenance as behavioural interventions are only moderately effective in attenuating weight regain by about 1.6 kg at 12 months (e.g. 150 ). Moreover, ImpulsePal consists of multiple strategies, using factorial designs evaluating individual intervention components and interactions in terms of effectiveness may inform refinements to the intervention for the optimisation of outcomes such as dietary change, weight loss or weight loss maintenance. 151 Relatedly, such optimisation might require a personalised approach. For example, what works for one individual might not necessarily work in the same way for someone else. N-of-1 randomised trials could help inform who might benefit from which particular technique which would help with personalisation of the intervention. 152 The ImpulsePal app also provides a great platform to potentially conduct Ecological Momentary Assessment 153 which involves repeated sampling of the participants’ current behaviours and experiences (e.g. strength of eating impulses) in real-time and natural environments. Texted prompts, or in-app notifications (as are used in ImpulsePal), asking about frequency and strength of cravings at periodic intervals (e.g. 154 ) or at context specific occurrences (i.e. when cravings or temptations are strong enough to trigger the individual to use ImpulsePal's emergency button) may provide a better measurement of craving as opposed to the use of retrospective questionnaires.

Conclusions

ImpulsePal is a novel, theory and evidence informed, person-centred app to improve impulse management and promote healthier eating for weight management. Intervention Mapping was a useful framework for helping to develop this intervention.

Abbreviations

- BMI

Body Mass Index

- DBCI

Digital behaviour change intervention

- IM

Intervention Mapping

Additional material

Additional file 1.pdf – Table S1 Triangulation, Table S2 Intervention Map, Table S3 Key changes after prototype testing.

Supplemental Material

Supplemental material, sj-docx-1-dhj-10.1177_20552076211057667 for ImpulsePal: The systematic development of a smartphone app to manage food temptations using intervention mapping by Samantha B van Beurden, Colin J Greaves, Charles Abraham, Natalia S Lawrence and Jane R Smith in Digital Health

Acknowledgements

The authors would particularly like to thank Prof Frederick Verbruggen and Dr Jenny Lloyd for their constructive advice on the development and evaluation plans, Dan Marshall and Diana Onu from Psynovigo Ltd for their invaluable insight in the technological possibilities and the programming of ImpulsePal and the Patient and Public advisory group and expert consultation group. The authors would also like to thank Prof Lucy Yardley and Prof Sarah Dean, who critically and constructively examined the doctoral thesis towards which the work reported here contributed. The views expressed in this publication are those of the authors and not necessarily of the University of Exeter Medical School or the NIHR.

Footnotes

Contributorship: All authors participated in the intervention development group discussions. SvB, convened the intervention development group, gathered and collated the needs assessment data from all described sources, developed the intervention map, created the programme materials, and was responsible for usability testing. CG, JS, and CA critically reviewed the intervention map. NL provided substantial advice on current evidence for, and operationalisation of inhibition training. SvB wrote the manuscript and all authors read, critically reviewed the manuscript and approved the final manuscript.

Ethics approval: The qualitative study referred to in the paper received ethical approval from the East of England Research Ethics Committee (Norfolk) in November 2012. No further approvals were required for the Patient and Public Involvement (https://www.invo.org.uk/) or Expert advisory groups.

Declaration of conflicting interests: The authors declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Funding: This intervention development study was funded through a University of Exeter Medical School PhD Scholarship held by SvB. The funding body had no role in the design of the development study, collection, analysis, and interpretation of the evidence base, the design of the intervention, or in the writing of the manuscript. CA's and CG's input was supported by the UK National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) through the Collaboration for Leadership in Applied Health Research and Care in the South West Peninsula (PenCLAHRC) and a Career Development Fellowship (CDF-2012-05-259) respectively.

ORCID iD: Samantha B van Beurden https://orcid.org/0000-0001-7848-2159

Reporting guidelines: This report follows the template for intervention description and replication (TIDieR) checklist and guide.

Guarantor: SvB.

Ethical Approval: Not applicable, because this article does not contain any studies with human or animal subjects.

Informed Consent: Not applicable, because this article does not contain any studies with human or animal subjects.

Trial Registration: Not applicable, because this article does not contain any clinical trials.

Supplemental material: Supplemental material for this article is available online.

References

- 1.Field AE, Coakley EH, Must A, et al. Impact of overweight on the risk of developing common chronic diseases during a 10-year period. Arch Intern Med 2001; 161: 1581–1586. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Fontaine KR, Bartlett SJ, Barofsky I. Health-related quality of life among obese persons seeking and not currently seeking treatment. Int J Eating Disord 2000; 27: 101–105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kolotkin RL, Binks M, Crosby RDet al. et al. Obesity and sexual quality of life. Obesity 2006; 14: 472–479. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kushner RF, Foster GD. Obesity and quality of life. Nutrition 2000; 16: 947–952. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Fontaine KR, Redden D, Wang Cet al. et al. Years of life lost due to obesity. JAMA 2003; 289: 187–193. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.McKinsey Global Institute. Overcoming obesity: An initial economic analyses [Internet]. 2014. Available from: www.mckinsey.com/mgi (04.01.2017).

- 7.World Health Organization. Obesity and overweight factsheet No. 311 [internet]. World Health Organization, 2016, [cited 2017 Apr 4]. Available from: http://www.who.int/mediacentre/factsheets/fs311/en/ [Google Scholar]

- 8.World Health Organisation. WHO Technical report series 916. Diet, nutrition and the prevention of excess weight gain and obesity. Report of a joint WHO/FAO expert consultation. Switzerland: World Health Organisation, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bates B, Cox L, Nicholson S, et al. National diet and nutrition survey. Results from years 5 and 6 (combined) of the rolling programms (2012/2013–2013–2014) [internet]. London: Public Health England, 2016, [cited 2017 Jun 29]. Available from: https://www.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/551352/NDNS_Y5_6_UK_Main_Text.pdf [Google Scholar]

- 10.French SA, Story M, Jeffery and RW. Environmental influences on eating and physical activity. Annu Rev Public Health 2001; 22: 309–335. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Poppitt SD, Prentice AM. Energy density and its role in the control of food intake: evidence from metabolic and community studies. Appetite 1996; 26: 153–174. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Stubbs RJ, Whybrow S. Energy density, diet composition and palatability: influences on overall food energy intake in humans. Physiol Behav 2004; 81: 755–764. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Swinburn BA, Caterson ID, Seidell JCet al. et al. Diet, nutrition and the prevention of excess weight gain and obesity. Public Health Nutr 2004; 7: 123–146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.What is energy density? - British Nutrition Foundation [Internet]. [cited 2020 Aug 28]. Available from: https://www.nutrition.org.uk/healthyliving/fuller/what-is-energy-density.html?__cf_chl_jschl_tk__=6ea420b5c7a3b07468f0f3aab7068d7b67936bfb-1598625344-0-Aa954tTFlx8TbSxknP0SuZNvv_owBQWs7V-_f-W_WOSDoC0t0e-KHlmG7ZXxnA_U8bPzfRHn4jYrRkSQasJbZZ86WvQpHpIzXdV9DKiQhZXtPbaqJ2my2SDti3KOz99yXDM6-cG10zBCfGCC-37yrvVsv7uRkaCPZufX_F_qh4NsHVd8×7m_sZSCitSSPLslokDaAeTuOmoQFIZgpJtRjsahXaDUxPMXRgrDBy5EIPLHQOLGJr-bxBYg-PemEWTrzBGVQiR1Byx GKezrhhwkZlWXdOx31q8CDBe7Te1PrP5Ug-ha1OFmOVR cvclcDEZMC1Nej4hr2s8H4_mkgddbQ0U1hM7lwtUQsBZjyRTijnDLv8RP5sO-ZHjK1iVZaBjLcFts2mxuZVf3nWW3zn UCLxo

- 15.Prentice AM, Jebb SA. Fast foods, energy density and obesity: a possible mechanistic link. Obes Rev 2003; 4: 187–194. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Rosenheck R. Fast food consumption and increased caloric intake: a systematic review of a trajectory towards weight gain and obesity risk. Obes Rev 2008; 9: 535–547. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Whybrow S, Mayer C, Kirk TRet al. et al. Effects of two weeks’ mandatory snack consumption on energy intake and energy balance. Obesity (Silver Spring) 2007; 15: 673–685. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Zizza C, Siega-Riz AM, Popkin BM. Significant increase in young adults’ snacking between 1977–1978 and 1994–1996 represents a cause for concern!. Prev Med 2001; 32: 303–310. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Morenga LT, Mallard S, Mann J. Dietary sugars and body weight: systematic review and meta-analyses of randomised controlled trials and cohort studies. Br Med J 2013; 346: e7492. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Malik VS, Schulze MB, Hu FB. Intake of sugar-sweetened beverages and weight gain: a systematic review. Am J Clin Nutr 2006; 84: 274–288. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Malik VS, Pan A, Willett WCet al. et al. Sugar-sweetened beverages and weight gain in children and adults: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Am J Clin Nutr 2013; 98: 1084–1102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Vartanian LR, Schwartz MB, Brownell KD. Effects of soft drink consumption on nutrition and health: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Am J Public Health 2007; 97: 667–675. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Yeomans MR. Alcohol, appetite and energy balance: is alcohol intake a risk factor for obesity? Physiol Behav 2010; 100: 82–89. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Public Health England. Obesity and Alcohol [Internet]. [cited 2017 Feb 1]. Available from: https://www.noo.org.uk/uploads/doc/vid_14627_Obesity_and_alcohol.pdf

- 25.Karl JP, Young AJ, Rood JCet al. et al. Independent and combined effects of eating rate and energy density on energy intake, appetite, and gut hormones. Obesity 2013; 21: E244–E252. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hou R, Mogg K, Bradley BPet al. et al. External eating, impulsivity and attentional bias to food cues. Appetite 2011; 56: 424–427. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ledikwe JH, Ello-Martin JA, Rolls BJ. Portion sizes and the obesity epidemic. J Nutr 2005; 135: 905–909. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Zlatevska N, Dubelaar C, Holden SS. Sizing up the effect of portion size on consumption: a meta-analytic review. J Mark 2014; 78: 140–154. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Livingstone MBE, Pourshahidi LK. Portion size and obesity. Adv Nutr 2014; 5: 829–834. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hill JO, Wyatt HR, Reed GWet al. et al. Obesity and the environment: where Do We Go from here? Science 2003; 299: 853–855. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Jeffery RW, Harnack LJ. Evidence implicating eating as a primary driver for the obesity epidemic. Diabetes 2007; 56: 2673–2676. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Grucza RA, Krueger RF, Racette SBet al. et al. The emerging link between alcoholism risk and obesity in the United States. Arch Gen Psychiatry 2010; 67: 1301–1308. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Guerrieri R, Nederkoorn C, Jansen A. The interaction between impulsivity and a varied food environment: its influence on food intake and overweight. Int J Obes 2007; 32: 708–714. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Hagan KE, Alasmar A, Exum Aet al. et al. A systematic review and meta-analysis of attentional bias toward food in individuals with overweight and obesity. Appetite 2020; 01: 104710. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Hendrikse JJ, Cachia RL, Kothe EJet al. et al. Attentional biases for food cues in overweight and individuals with obesity: a systematic review of the literature. Obes Rev 2015; 16: 424–432. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Fedoroff I, Polivy J, Herman CP. The specificity of restrained versus unrestrained eaters’ responses to food cues: general desire to eat, or craving for the cued food? Appetite 2003; 41: 7–13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Locke AE, Kahali B, Berndt SI, et al. Genetic studies of body mass index yield new insights for obesity biology. Nature 2015; 518: 197–206. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.de Lauzon-Guillain B, Clifton EA, Day FR, et al. Mediation and modification of genetic susceptibility to obesity by eating behaviors. Am J Clin Nutr 2017; 106: 996–1004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Konttinen H, Llewellyn C, Wardle J, et al. Appetitive traits as behavioural pathways in genetic susceptibility to obesity: a population-based cross-sectional study. Sci Rep 2015; 5: 14726. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Jacob R, Drapeau V, Tremblay Aet al. et al. The role of eating behavior traits in mediating genetic susceptibility to obesity. Am J Clin Nutr 2018; 108: 445–452. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Craig P, Dieppe P, Macintyre Set al. et al. Developing and evaluating complex interventions: the new medical research council guidance. Br Med J 2008; 337: a1655–a1655. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Craig P, Dieppe P, Macintyre Set al. et al. Developing and evaluating complex interventions: the new medical research council guidance. Int J Nurs Stud 2013; 50: 587–592. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Tang JCH, Abraham C, Greaves CJet al. et al. Self-Directed interventions to promote weight loss: a systematic review of reviews. J Med Internet Res 2014; 16: e58. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Ajzen I. The theory of planned behavior. Organ Behav Hum Decis Process 1991; 50: 179–211. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Prochaska JO, DiClemente CC. Stages and processes of self-change of smoking: toward an integrative model of change. J Consult Clin Psychol 1983; 51: 390–395. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Klesges RC, Isbell TR, Klesges LM. Relationship between dietary restraint, energy intake, physical activity, and body weight: a prospective analysis. J Abnorm Psychol 1992; 101: 668–674. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Verhoeven AAC, Adriaanse MA, Evers Cet al. et al. The power of habits: unhealthy snacking behaviour is primarily predicted by habit strength. Br J Health Psychol 2012; 17: 758–770. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Weijzen PLG, de G, Dijksterhuis GB. Discrepancy between snack choice intentions and behavior. J Nutr Educ Behav 2008; 40: 311–316. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Elfhag K, Rössner S. Who succeeds in maintaining weight loss? A conceptual review of factors associated with weight loss maintenance and weight regain. Obes Rev 2005; 6: 67–85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Jeffery RW, Drewnowski A, Epstein LH, et al. Long-term maintenance of weight loss: current status. Health Psychol 2000; 19: 5–16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Mann T, Tomiyama AJ, Westling Eet al. et al. Medicare’s search for effective obesity treatments: diets are not the answer. Am Psychol 2007; 62: 220–233. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Strack F, Deutsch R. Reflective and impulsive determinants of social behavior. Pers Soc Psychol Rev 2004; 8: 220–247. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Hall PA, Fong GT. Temporal self-regulation theory: a model for individual health behavior. Health Psychol Rev 2007; 1: 6–52. [Google Scholar]

- 54.Borland R. Understanding hard to maintain behaviour change: a dual process approach [internet]. West Sussex, UK: Wiley and Sons, 2014, [cited 2016 Jul 12]. Available from: http://eu.wiley.com/WileyCDA/WileyTitle/productCd-1118572912.html. [Google Scholar]

- 55.Friese M, Hofmann W, Wänke M. When impulses take over: moderated predictive validity of explicit and implicit attitude measures in predicting food choice and consumption behaviour. Br J Soc Psychol 2008; 47: 397–419. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Veling H, Aarts H. Changing impulsive determinants of unhealthy behaviours towards rewarding objects. Health Psychol Rev 2011; 5: 150–153. [Google Scholar]

- 57.Veling H, Aarts H, Stroebe W. Using stop signals to reduce impulsive choices for palatable unhealthy foods. Br J Health Psychol 2013; 18: 354–368. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Marteau TM, Hollands GJ, Fletcher PC. Changing human behavior to prevent disease: the importance of targeting automatic processes. Science 2012; 337: 1492–1495. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Sheeran P, Gollwitzer PM, Bargh JA. Nonconscious processes and health. Health Psychol 2013; 32: 460–473. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Schoeppe S, Alley S, Van Lippevelde W, et al. Efficacy of interventions that use apps to improve diet, physical activity and sedentary behaviour: a systematic review. Int J Behav Nutr Phys Act 2016; 13: 127. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Oh H, Rizo C, Enkin Met al. et al. What is eHealth (3): a systematic review of published definitions. J Med Internet Res [Internet] 2005 [cited 2014 Feb 24]; 7(1): e1. Available from: http://www.jmir.org/2005/1/e1/ [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Michie S, Yardley L, West Ret al. et al. Developing and evaluating digital interventions to promote behavior change in health and health care: recommendations resulting From an international workshop. J Med Internet Res 2017; 19: e232. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Bartholomew LK, Parcel GS, Kok Get al. et al. Planning health promotion programs. An intervention mapping approach. 3rd ed. San Francisco: John Wiley & Sons, Ltd, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 64.Lloyd JJ, Logan S, Greaves CJet al. et al. Evidence, theory and context - using intervention mapping to develop a school-based intervention to prevent obesity in children. Int J Behav Nutr Phys Act 2011; 8: 73. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Verbestel V, Henauw SD, Maes L, et al. Using the intervention mapping protocol to develop a community-based intervention for the prevention of childhood obesity in a multi-centre european project: the IDEFICS intervention. Int J Behav Nutr Phys Act 2011; 8: 82. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Taylor NJ, Sahota P, Sargent J, et al. Using intervention mapping to develop a culturally appropriate intervention to prevent childhood obesity: the HAPPY (healthy and active parenting programme for early years) study. Int J Behav Nutr Phys Act 2013; 10: 142. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Greaves CJ, Wingham J, Deighan C, et al. Optimising self-care support for people with heart failure and their caregivers: development of the rehabilitation enablement in chronic heart failure (REACH-HF) intervention using intervention mapping. Pilot Feasibility Stud 2016; 2: 37. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.De Decker E, De Craemer M, De Bourdeaudhuij I, et al. Using the intervention mapping protocol to reduce european preschoolers’ sedentary behavior, an application to the ToyBox-study. Int J Behav Nutr Phys Act 2014; 11: 19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Dalal H, Taylor RS, Jolly K, et al. The effects and costs of home-based rehabilitation for heart failure with reduced ejection fraction: the REACH-HF multicentre randomized controlled trial. Eur J Prev Cardiol 2018; 26: 262–272. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.van Beurden SB, Simmons SI, Tang JCHet al. et al. Informing the development of online weight management interventions: a qualitative investigation of primary care patient perceptions. BMC Obes 2018; 5: 7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.INVOLVE | INVOLVE Supporting public involvement in NHS, public health and social care research [Internet]. [cited 2019 Nov 13]. Available from: https://www.invo.org.uk/

- 72.van Beurden SB, Greaves CJ, Smith JRet al. et al. Techniques for modifying impulsive processes associated with unhealthy eating: a systematic review. Health Psychol 2016; 35: 793–806. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.O’Cathain A, Murphy E, Nicholl J. Three techniques for integrating data in mixed methods studies. Br Med J 2010; 341: c4587. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Hofmann W, Friese M, Wiers RW. Impulsive versus reflective influences on health behavior: a theoretical framework and empirical review. Health Psychol Rev 2008; 2: 111–137. [Google Scholar]

- 75.Nederkoorn C, Guerrieri R, Havermans Ret al. et al. The interactive effect of hunger and impulsivity on food intake and purchase in a virtual supermarket. Int J Obes (Lond) 2009; 33: 905–912. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Allan JL, Johnston M, Campbell N. Unintentional eating. What determines goal-incongruent chocolate consumption? Appetite 2010; 54: 422–425. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Hagger MS, Panetta G, Leung C-M, et al. Chronic inhibition, self-control and eating behavior: test of a ‘resource depletion’ model. PLOS ONE 2013; 8: e76888. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Baumeister RF, Heatherton TF. Self-regulation failure: an overview. Psychol Inq 1996; 7: 1–15. [Google Scholar]

- 79.Wansink B, Painter JE, North J. Bottomless bowls: why visual cues of portion size may influence intake. Obes Res 2005; 13: 93–100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Verplanken B, Aarts H. Habit, attitude, and planned behaviour: is habit an empty construct or an interesting case of goal-directed automaticity? Eur Rev Soc Psychol 1999; 10: 101–134. [Google Scholar]

- 81.Papies EK. Health goal priming as a situated intervention tool: how to benefit from nonconscious motivational routes to health behavior. Health Psychol Rev 2016; 0: 1–35. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Papies EK, Stroebe W, Aarts H. Pleasure in the mind: restrained eating and spontaneous hedonic thoughts about food. J Exp Soc Psychol 2007; 43: 810–817. [Google Scholar]

- 83.Baumeister RF, Vohs KD, Tice DM. The strength model of self-control. Curr Dir Psychol Sci 2007; 16: 351–355. [Google Scholar]

- 84.Hagger MS, Wood C, Stiff Cet al. et al. Ego depletion and the strength model of self-control: a meta-analysis. Psychol Bull 2010; 136: 495. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Vohs KD, Heatherton TF. Self-regulatory failure: a resource-depletion approach. Psychol Sci 2000; 11: 249–254. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Hofmann W, Rauch W, Gawronski B. And deplete us not into temptation: automatic attitudes, dietary restraint, and self-regulatory resources as determinants of eating behavior. J Exp Soc Psychol 2007; 43: 497–504. [Google Scholar]

- 87.Miller G. The smartphone psychology manifesto. Perspect Psychol Sci 2012; 7: 221–237. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Boschen MJ, Casey LM. The use of mobile telephones as adjuncts to cognitive behavioral psychotherapy. Prof Psychol: Res Pract 2008; 39: 546–552. [Google Scholar]

- 89.Morris ME, Aguilera A. Mobile, social, and wearable computing and the evolution of psychological practice. Prof Psychol: Res Pract 2012; 43: 622–626. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Webb TL, Joseph J, Yardley Let al. et al. Using the internet to promote health behavior change: a systematic review and meta-analysis of the impact of theoretical basis, use of behavior change techniques, and mode of delivery on efficacy. J Med Internet Res 2010; 12(1): e4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Donkin L, Christensen H, Naismith SLet al. et al. A systematic review of the impact of adherence on the effectiveness of e-therapies. J Med Internet Res 2011; 13: e52. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Kelders SM, Van Gemert-Pijnen JEWC, Werkman Aet al. et al. Effectiveness of a web-based intervention aimed at healthy dietary and physical activity behavior: a randomized controlled trial about users and usage. J Med Internet Res 2011; 13: e32. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Hwang KO, Ning J, Trickey AWet al. et al. Website usage and weight loss in a free commercial online weight loss program: retrospective cohort study. J Med Internet Res 2013; 15: e11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Kohl LF, Crutzen R, Vries Nd. Online prevention aimed at lifestyle behaviors: a systematic review of reviews. J Med Internet Res 2013; 15: e146. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Tang JCH, Abraham C, Stamp Eet al. et al. How can weight-loss app designers’ best engage and support users? A qualitative investigation. Br J Health Psychol 2015; 20: 151–171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Michie S, Johnston M, Francis JJet al. et al. From theory to intervention: Mapping theoretically derived behavioural determinants to Behaviour Change Techniques. 2008 [cited 2013 Nov 4]; Available from: http://aura.abdn.ac.uk/handle/2164/302

- 97.Michie S, Richardson M, Johnston M, et al. The behavior change technique taxonomy (v1) of 93 hierarchically clustered techniques: building an international consensus for the reporting of behavior change interventions. Ann Behav Med 2013; 46: 81–95. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Lawrence NS, Verbruggen F, Morrison Set al. et al. Stopping to food can reduce intake. Effects of stimulus-specificity and individual differences in dietary restraint. Appetite 2015; 85: 91–103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Lawrence NS, O’Sullivan J, Parslow D, et al. Training response inhibition to food is associated with weight loss and reduced energy intake. Appetite 2015; 95: 17–28. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Allom V, Mullan B, Hagger M. Does inhibitory control training improve health behaviour? A meta-analysis. Health Psychol Rev 2015; 0: 1–38. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Kelders SM, Kok RN, Ossebaard HCet al. et al. Persuasive system design does matter: a systematic review of adherence to web-based interventions. J Med Internet Res 2012; 14: e152. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Brouwer W, Kroeze W, Crutzen R, et al. Which ntervention characteristics are related to more exposure to internet-delivered healthy lifestyle promotion interventions? A systematic review. J Med Internet Res 2011; 13: e2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Morrison LG, Yardley L, Powell Jet al. et al. What design features Are used in effective e-health interventions? A review using techniques from critical interpretive synthesis. Telemedicine and e-Health 2012; 18: 137–144. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Deterding S, Dixon D, Khaled Ret al. et al. From game design elements to gamefulness: Defining ‘gamification’. In 2011. p. 9–15.

- 105.Kemps E, Tiggemann M. Hand-held dynamic visual noise reduces naturally occurring food cravings and craving-related consumption. Appetite 2013; 68: 152–157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Kemps E, Tiggemann M, Woods Det al. et al. Reduction of food cravings through concurrent visuospatial processing. Int J Eating Disord 2004; 36: 31–40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]