Abstract

In recent electrocochleographic studies, the amplitude of the summating potential (SP) was an important predictor of performance on word-recognition in difficult listening environments among normal-hearing listeners; paradoxically the SP was largest in those with the worst scores. SP has traditionally been extracted by visual inspection, a technique prone to subjectivity and error. Here, we assess the utility of a fitting algorithm [Kamerer, Neely, and Rasetshwane (2020). J Acoust Soc Am. 147, 25–31] using a summed-Gaussian model to objectify and improve SP identification. Results show that SPs extracted by visual inspection correlate better with word scores than those from the model fits. We also use fast Fourier transform to decompose these evoked responses into their spectral components to gain insight into the cellular generators of SP. We find a component at 310 Hz associated with word-identification tasks that correlates with SP amplitude. This component is absent in patients with genetic mutations affecting synaptic transmission and may reflect a contribution from excitatory post-synaptic potentials in auditory nerve fibers.

I. INTRODUCTION

Animal studies from the past decade have shown that the synapses between inner hair cells and auditory nerve fibers can be permanently damaged as a result of a cochlear insult, including noise exposure and aging (Kujawa and Liberman, 2009; Sergeyenko et al., 2013). This cochlear nerve degeneration (CND), also known as cochlear synaptopathy or hidden hearing loss, is also found in human temporal bones, where the rate of cochlear neural loss outstrips the rate of sensory cell loss in the aging ear (Viana et al., 2015; Wu et al., 2019). In mouse studies, CND is reflected in the reduction of suprathreshold amplitude of ABR wave 1, the summed activity of cochlear neurons, so long as cochlear thresholds remain normal (Kujawa and Liberman, 2009; Sergeyenko et al., 2013; Kujawa and Liberman, 2015). However, diagnosing CND in humans is challenging, as wave 1 amplitude is smaller and varies widely across normal-hearing participants when measured via conventional ABR electrode configurations (Boston and Moller, 1985).

Researchers have tried to enhance wave 1 amplitudes by means of intra-meatal electrodes (Harder and Arlinger, 1981; Lang et al., 1981; Walter and Blegvad, 1981; Durrant and Ferraro, 1991) and/or by varying electrode montages (Laughlin et al., 1999). Despite these efforts, and in contrast to the robustness of response latencies, wave 1 amplitudes remain highly variable, presumably due, in part, to differences in head size, electrode contact, etc. (Jerger and Hall, 1980; Michalewski et al., 1980; Schwartz and Berry, 1985; Gorga et al., 1988; Nikiforidis et al., 1993). In our quest for reliable CND markers in humans (Liberman et al., 2016), we hoped to reduce the variability of wave 1 amplitude by normalizing it to the summating potential (or SP), a low-frequency component classically thought to comprise hair cell receptor potentials (Durrant et al., 1998). Since the generators of SP and wave 1 are physically close, we initially reasoned that both would be similarly affected by many of the inter-subject differences that generate amplitude variability. As it turned out, our measures of SP itself have proven to be a better predictor of performance on word identification tasks, which, in turn, may be a biomarker of CND (Alvord, 1983; Santarelli et al., 2019; Grant et al., 2020; Kara et al., 2020; Mepani et al., 2020; Monaghan et al., 2020) as shown in studies showing poorer temporal processing and signal-in-noise detection task performances in (1) animal with CND (Chambers et al., 2016; Lobarinas et al., 2020; Monaghan et al., 2020; Resnik and Polley, 2021) and (2) in humans with reduced ABR wave 1 amplitude, larger SP amplitude or larger SP/AP ratio (Bramhall et al., 2015; Liberman et al., 2016; Ridley et al., 2018; Buran et al., 2020; Grant et al., 2020) or with reduced EFR magnitudes (Mepani et al., 2021).

Although wave 1, or AP as it is referred to in electrocochleography, generated with intra-meatal electrodes, high-level click stimuli and a horizontal montage is large and easy to identify in normal-hearing subjects, SP amplitudes can be low and are therefore more prone to inter-observer discrepancy when identified by visual inspection. In light of these challenges (Arnold, 1985), a number of alternative methods to objectify and automate ABR wave identification have been developed (Valderrama et al., 2014). Recently, a summed-Gaussian model was evaluated in fitting electrocochleographic waveforms of 32 participants with normal hearing or sensorineural hearing loss (Kamerer et al., 2020). This model yielded excellent agreement with visual determination of ABR wave 1 amplitude (ICC = 0.88, p < 0.001) but relatively poor matches for SP amplitudes (ICC = 0.24, p = 0.104).

Here, we apply the summed Gaussian model of Kamerer et al. (2020) to a larger cohort of normal-hearing subjects (n = 116) and analyze the nature of the discrepancies with measurements by visual inspection. In the same cohort of participants we also investigate the contributions of hair cells vs auditory nerve fibers to the ABR waves using Fourier transforms of electrocochleographic waveforms and by comparing these data to those obtained from patients with mutations of the otoferlin (OTOF) gene that disrupt synaptic-vesicle release from the inner hair cell ribbon synapses, leaving hair cell receptor potentials intact (Santarelli et al., 2009).

II. MATERIALS AND METHODS

A. Model

ABR waveforms were modeled using two Gaussian functions as described by Kamerer et al. (2020), each designed to fit the SP (1) and AP (2), respectively, where A is the peak amplitude (μV), L is the peak latency (ms), and W is the width (ms),

with tmin = L2 – 1.25 (ms) and tmax = L2 + 0.25 (ms).

Table I describes two sets of initial values and boundary conditions. Model determination of SP was either following (1) a set of constraints described in Table I(A), adapted from Kamerer et al. (2020) to account for differences in stimulus (1-ms Blackman-gated pure tone at 4 kHz vs 100-μs click) or (2) a set of constraints described in Table I(B) that relies partly on the tester's identification of AP.

TABLE I.

ABR waveform model bond constraints aimed at identifying SP (1) and wave I (2). A: peak amplitude; L: peak latency; W: peak width.

| (A) Not constrained to AP | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Initial value | Lower bound | Upper bound | |

| A1 (μV) | 0.75 | 0 | ∞ |

| L1 (ms) | 0.5 | 0 | 1 |

| W1 (ms) | 0.3 | 0 | 0.7 |

| A2 (μV) | 1 | 0 | ∞ |

| L2 (ms) | 1.75 | 1 | 2.5 |

| W2 (ms) | 0.2 | 0 | 0.7 |

| (B) Constrained to AP | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Initial value | Lower bound | Upper bound | |

| A1 (μV) | 0.75 | 0 | ∞ |

| L1 (ms) | L2 tester − 1.0 | 0.01 | L2 tester − 0.5 |

| W1 (ms) | 0.3 | 0 | 0.7 |

| A2 (μV) | 1 | 0 | ∞ |

| L2 (ms) | L2 tester | L2 tester − 0.1 | L2 tester + 0.1 |

| W2 (ms) | 0.2 | 0 | 0.7 |

B. Subject pool and inclusion criteria

116 native speakers of English in good health, between the ages of 18 and 63, with no history of ear or hearing problems, no history of neurologic disorders and unremarkable otoscopic examinations were recruited. All participants had normal audiometric thresholds from 0.25 to 8 kHz in both ears (≤25 dB HL) and normal middle-ear function. Tympanometry was performed using the titan suite from Interacoustics, with a probe-tone frequency of 226 Hz and an ear-canal pressure change ranging from −300 to +200 daPa in each ear to ensure that ear canal volume, tympanic membrane mobility and middle-ear pressure were normal. This study was reviewed and approved by the Institutional Review Board of Mass Eye & Ear. Analyses of middle-ear muscle reflexes and electrocochleographic responses from most of the same subjects have been presented in prior reports (Grant et al., 2020; Mepani et al., 2021).

C. Electrocochleography

Stimuli were generated by our custom rig, stimulus waveforms were transduced via ER-3A insert earphones, and data acquisition was handled by the Interacoustics Eclipse hardware and software. Subjects' ear canals were prepped by scrubbing with a cotton swab coated in Nuprep®. Electrode gel was applied on the cleaned portion of the canal and over the gold-foil of ER3- 26 A/B tiptrodes before insertion. A horizontal montage was used, with a ground on the forehead at midline, one tiptrode as the inverting electrode and the other as the non-inverting electrode in the opposite ear. Low (<5 kΩ) and balanced impedance readings were obtained with inter-electrode impedance values within 2 kΩ of each other. Acoustic stimuli were delivered via silicone tubing connected to the ER-3A earphones. Stimuli were 100 μs-clicks delivered at 125 dB pSPL in alternating polarity at a presentation rate of 9.1 or 40.1 Hz in presence or absence of a 90-ms forward masking noise (8–16 kHz, 5-ms ramp) presented 6 ms before the click onset (Grant et al., 2020). The total noise dose for all ECochG measurements was well within OSHA and NIOSH standards. Electrical responses were amplified 100 000×, and 2000 sweeps were averaged for each recording. Average traces acquired by the Eclipse software (passband 3.3–5000 Hz) were exported as raw traces or underwent further analysis, including digital filtering (64-point zero-phase finite impulse response filter) with different passband of various high-pass cutoff frequencies ranging from 10–3000 Hz to 300–3000 Hz.

D. Visual inspection of waveforms

All visual inspections of waveforms were done independently by two observers blinded to all other test results. Baseline was defined as the first data point two standard deviations (SDs) above the mean pre-onset amplitude (–2 to 0 ms). AP peak was defined as the maximum amplitude within the window 1–2 ms post stimulus onset.

Under unfiltered conditions and using a 10–3000 Hz filter, SP peak was defined as the last and common inflection point preceding the rising phase of AP as identified in all unfiltered waveforms obtained from the same ear (under a stimulus presentation rate of 9.1 Hz with and without a 8–16 kHz masking noise and under a 40.1 Hz presentation rate). Under a 300–3000 Hz filter, SP peak was defined as the maximum amplitude of the wave preceding AP. See text below for further details.

E. Cluster analysis

Hierarchical clustering analyses of individual spectra derived from ABR waveforms were performed under matlab® to obtain a dendrogram where the distance of split/merge was recorded. Spearman and Euclidean correlations were used to compute the distance between each pair of observations. Rules of hierarchical clustering between pairs were based on either a Ward's method or a complete-linkage clustering method to define spectral groups. The cutting distance was set to separate all data into 2 clusters of similar size.

F. Statistical analysis

Agreement between measures (estimation of wave amplitude obtained from model vs measured data obtained from visual inspection) for each participant is reported as intraclass correlation coefficients (ICC). To ease comparison across studies, we adopted the same criteria defined by Koo and Li (2016) and used in Kamerer et al. (2020) to characterize the strength of the agreement between measures. ICC scores were considered: excellent if ICC ≥ 0.90, good if 0.9 ≥ ICC > 0.75, moderate if 0.75 ≥ ICC>0.5 and poor if ICC < 0.50.

Pearson's correlation coefficients were used to assess the strength of the pairwise correlations between ABR waveform measures and spectral peak amplitudes derived from their fast Fourier transform (FFT). Two-tailed Student's t test for homoscedastic groups were used to test for a difference in the mean of predictor variables.

III. RESULTS

A. Model fit vs visual inspection

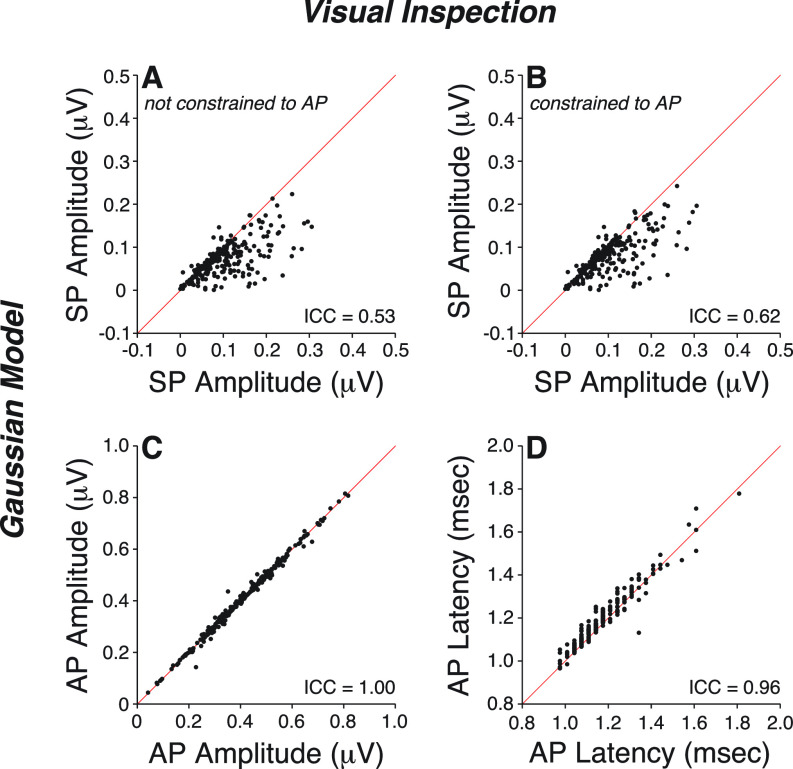

As shown in Fig. 1 and Table II, model estimates of AP amplitude and latency were in excellent agreement with data obtained from visual inspection, when analyzed with a 10–3000 Hz filter [ICC > 0.90, Figs. 1(C) and 1(D)]. However, model estimates of SP amplitudes were only in moderate agreement with visual determinations [ICC = 0.53, Fig. 1(A)].

FIG. 1.

(Color online) Measures of SP amplitude (A,B), AP amplitude (C), and AP latency (D) were obtained by visual inspection of ABR waveforms digitally filtered through a 10–3000 Hz passband and compared to model estimations. Model estimation of SP was either constrained (B) or not (A) to the tester's identification of AP. Diagonal lines indicates a slope of 1. ICC: intraclass correlation coefficient.

TABLE II.

Agreement between model determination and visual inspection of SP amplitude as assessed with intraclass correlation coefficients (ICCs) from waveforms obtained in response to a click delivered at 9.1 Hz without a forward masker.

| Method | Filter | 95% CI Value | F Test | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ICC | Lower | Upper | Value | df | p | ||

| User independent | 10–3000 | 0.53 | 0.22 | 0.71 | 4.33 | 231 | <0.001 |

| Constrained to AP | 10–3000 | 0.62 | 0.38 | 0.76 | 5.45 | 231 | <0.001 |

| User independent | 300–3000 | 0.90 | 0.86 | 0.92 | 19.51 | 216 | <0.001 |

To improve model performance, we tested the idea that the asymmetry between the rising and falling slopes of the AP causes the poor SP fits. Errors due to fitting a single symmetric Gaussian waveform to an asymmetric AP may outweigh errors due to misfitting the smaller SP, as the Gaussian model's capture of SP can be coopted by the nonlinear regression used to improve the fit of AP. To address this, we constrained the model using a tester-supplied value for AP latency (L2,tester) (Fig. 1, Table I) and limiting the fit to a 1.5-ms segment preceding AP peak by 1.25 ms and lagging it by 0.25 ms. By excluding the portion of AP greater than 0.25 ms beyond its peak, we minimized the contribution of the falling slope to the fit. However, this model adjustment only led to minimal improvement [ICC = 0.62, Fig. 1(B)].

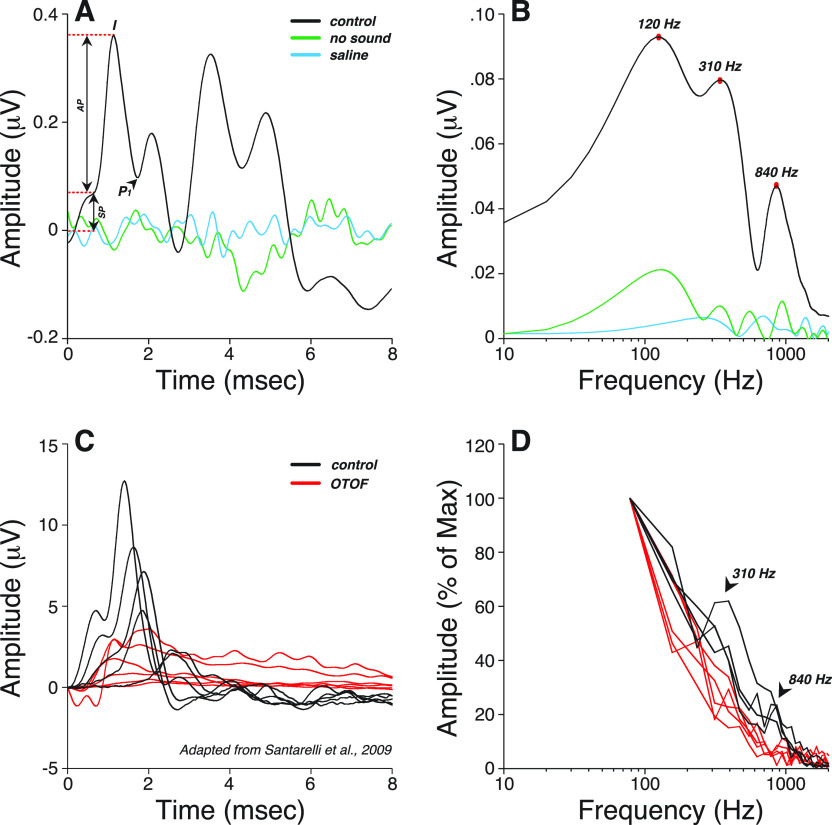

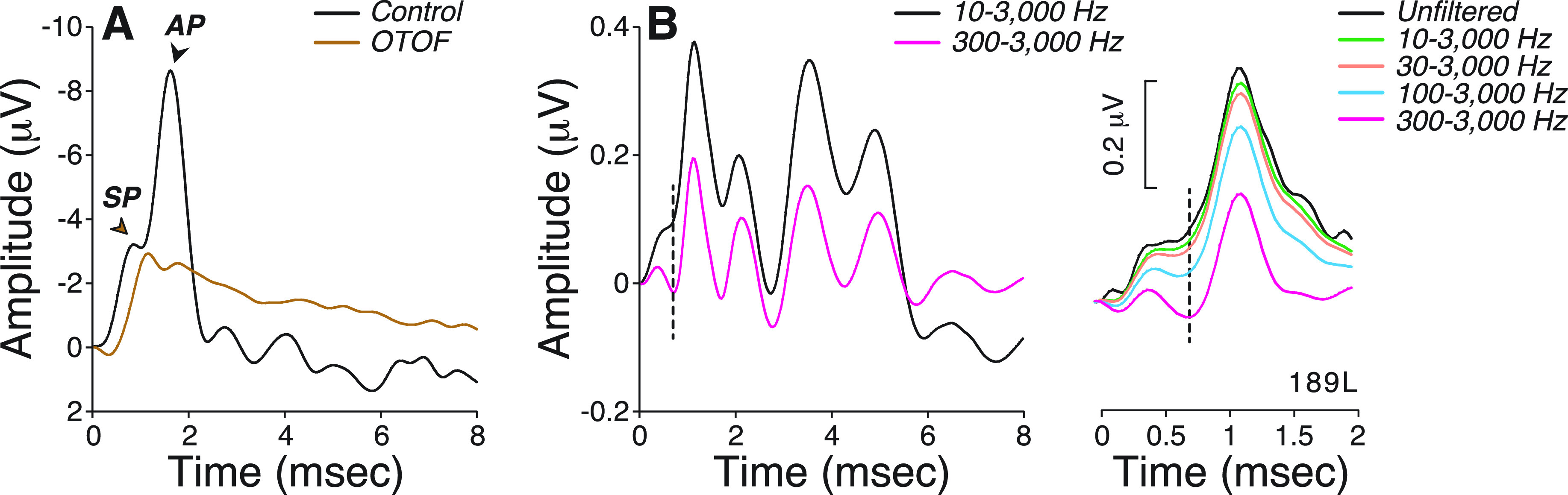

When the same ABR waveforms were analyzed through a narrower filter (300–3000 Hz), model performance in matching visual inspection of SP improved to excellent (ICC = 0.90, Table II). This is not surprising given the contribution of the missing 10–300 Hz band on waveform morphology (Fig. 2). As shown in patients carrying OTOF gene mutations that block synaptic transmission but leave hair cell function otherwise intact (Santarelli et al., 2009), SP is a slow-declining low-frequency potential that overlaps in time with AP [Fig. 2(A)]. Raising the high-pass filter cutoff changes SP shape [Fig. 2(B)], removing most of its low-frequency component. With a 300–3000 Hz filter, SP emerges as a distinct small wave, separated from AP by a clear trough, and is easily identifiable with a model based on two Gaussians. On the other hand, when using a 10–3000 Hz filter, a larger SP acts as a pedestal for the emerging and overlapping AP wave, rendering their separation more difficult. Thus, improving the model fit comes at the expense of filtering out most of the SP.

FIG. 2.

(Color online) (A) SP and AP waves recorded from one control and one patient with otoferlin (OTOF) gene mutations in response to a click stimulus [adapted from (Santarelli et al., 2009)]. (B,C) Effects of post hoc digital filtering on the mean ABR waveforms from all participants (B) or on one participant (C) using multiple high-pass frequency cutoffs, as indicated.

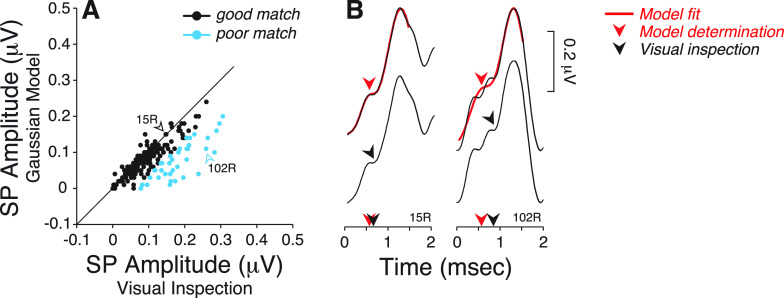

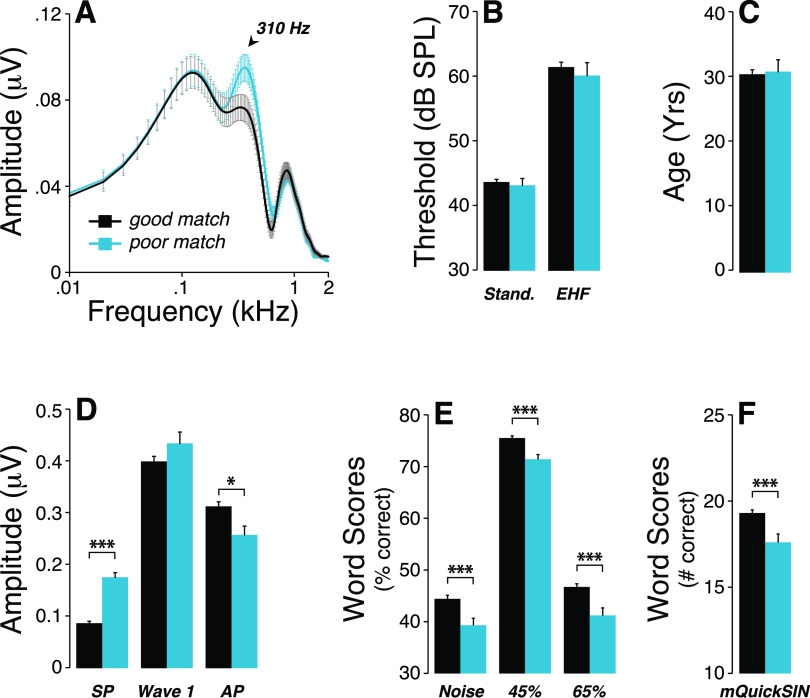

Since that trade-off is unacceptable, we returned to the data with the wider filter and further investigated why visual inspection differs from model-fit results. To do so, we identified all ears where model-fit SP amplitude differed by more than one standard deviation (SD) from the visually determined value (Fig. 3). This separated a good match group of 190 ears from a poor match group of 42 ears (∼18%). Note that all visual SP amplitudes for the latter group were larger than predicted by model fit [Fig. 3(A)]. One source of discrepancy arises from smoothing the multiple inflection points preceding AP, as seen here [Fig. 3(B)] and in other studies (Ferraro and Krishnan, 1997; Sass et al., 1997; Kim et al., 2005).

FIG. 3.

(Color online) (A) A good and poor match groups were defined based on whether the SP amplitude values obtained from model determination differed (or not) by more than one standard deviation (SD) from the SP values obtained by visual inspection. Data were obtained from ABR waveforms digitally filtered through a 10–3000 Hz passband. Diagonal line indicates a slope of 1. (B) Comparison of SP determination using model fit vs visual inspection on two examples of individual ABR waveforms. Arrowheads indicate the location and latency of the SP as determined by each method.

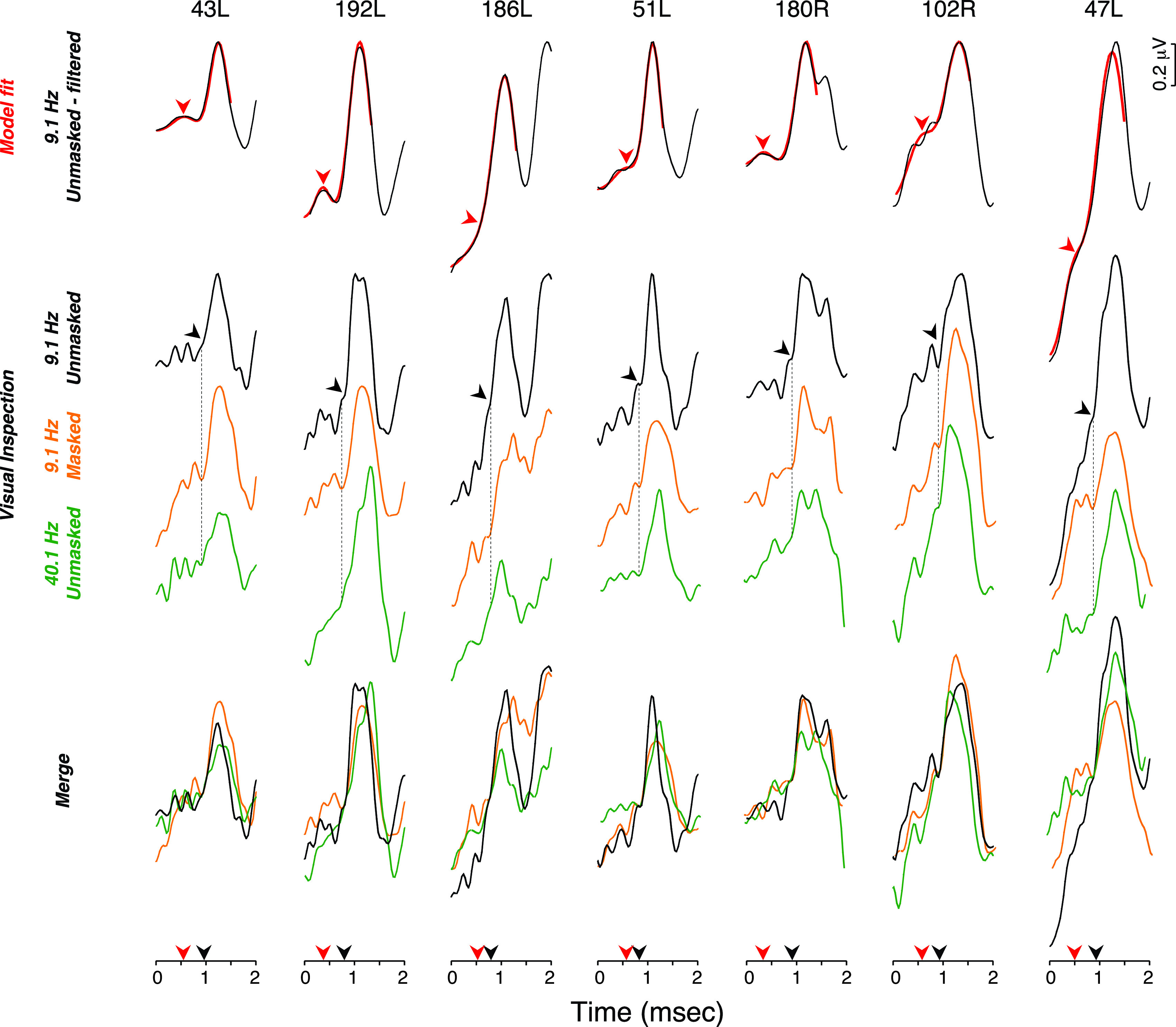

Under the visual-fit algorithm, SP was defined as the last and common inflection point preceding the rising phase of AP. Figure 4 further illustrates this with seven ABR waveforms from the poor match group for which visual determination of SP is aided by superimposing the unfiltered waveforms obtained from each subject under three conditions: (a) standard repetition rate (9.1 Hz), (b) fast repetition rate (40.1 Hz), and (c) standard repetition rate with a forward masker. Increasing the stimulus presentation rate and using a forward masker should affect AP much more than SP, if these waves are dominated by neural and hair cell potentials, respectively. These examples show how the filtering often removes (1) a late inflection point preceding AP (e.g., 51 L, Fig. 4) and (2) multiple inflection points present within the first ms segment of the waveform (e.g., 102R, Fig. 4).

FIG. 4.

(Color online) (A) Top row: ABR waveforms digitally filtered with a 10–3000 Hz passband from 7 ears from the poor match group were compared to Gaussian model fits. Arrowhead points at model determination of SP. Middle row: Unfiltered ABR waveforms obtained in response to clicks delivered at a presentation rate of 9.1 or 40.1 Hz in presence or absence of a forward masking noise, as indicated. Arrowhead points at the location of SP as determined visually. Bottom row: merged waveforms from the middle row show the common and last inflection point preceding AP and defining SP.

B. Fast Fourier transform of ABR waveforms

To gain insight into the generators underlying the SP, and to explore a different approach to ECochG analysis, we computed fast Fourier transforms (FFTs) of the waveforms. The resultant spectra have peaks, at 120, 310, and 840 Hz [Fig. 5(A) and 5(B)]. In a patient carrying OTOF mutations, both the 310 and 840 Hz spectral peaks were absent [Figs. 5(C) and 5(D)] suggesting that they arise from neural generators. Unfortunately, the length of the sample in time did not allow for an evaluation of the 120 Hz peak.

FIG. 5.

(Color online) (A) Averaged click-evoked ABR obtained from all participants shows how measures were visually extracted under a 10–3000 Hz filter. Baseline was defined as the first amplitude point exceeding 2 SD above the mean pre-onset amplitude (–2 to 0 ms). The summating potential (SP) was defined as the difference between baseline and the last inflection point on the rising phase of wave I. Wave I peak or AP was defined as the maximum amplitude 1–2 ms post-stimulus onset, and P1 was defined as the next major trough. As a control for line-locked electrical artifacts, additional waveforms were obtained in one subject with no sound output or with recording electrodes in saline (green and blue traces respectively). (B) Averaged fast Fourier transform (FFT) of the waveforms shown in (A). (C) Cochlear potentials recorded in a normal hearing subject and in a patient with mutations in the OTOF gene in response to clicks at decreasing stimulation levels (110–70 dB pSPL) [adapted from (Santarelli et al., 2009)]. In a patient with OTOF mutations, the SP was present at all levels whilst the AP remained absent at levels as high as 110 dB pSPL. (D) FFTs of the cochlear potentials shown in (C) indicate that both spectral peaks at 310 and 840 Hz observed in normal-hearing controls are absent in a patient with OTOF mutations.

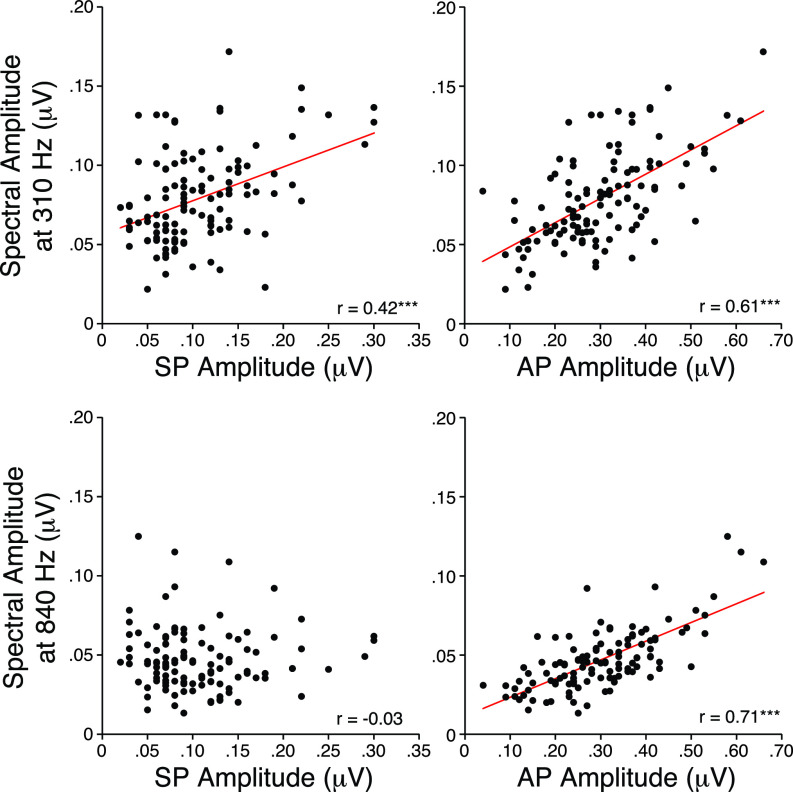

One way of providing clues as to the generator(s) of each spectral peak is to evaluate the correlations between time-domain measures of waveform peaks and the FFT spectral peaks as illustrated by the scatterplots in Fig. 6. While SP amplitude correlated best with the 310 Hz peak (p < 0.001), AP amplitudes correlated best with the 840 Hz peak (p < 0.001).

FIG. 6.

(Color online) Bivariate correlations with their respective regression lines (red) between measures of SP, AP amplitudes compared to spectral peak amplitudes measured at 310 Hz and 840 Hz. r = correlation coefficient. *** p < 0.001.

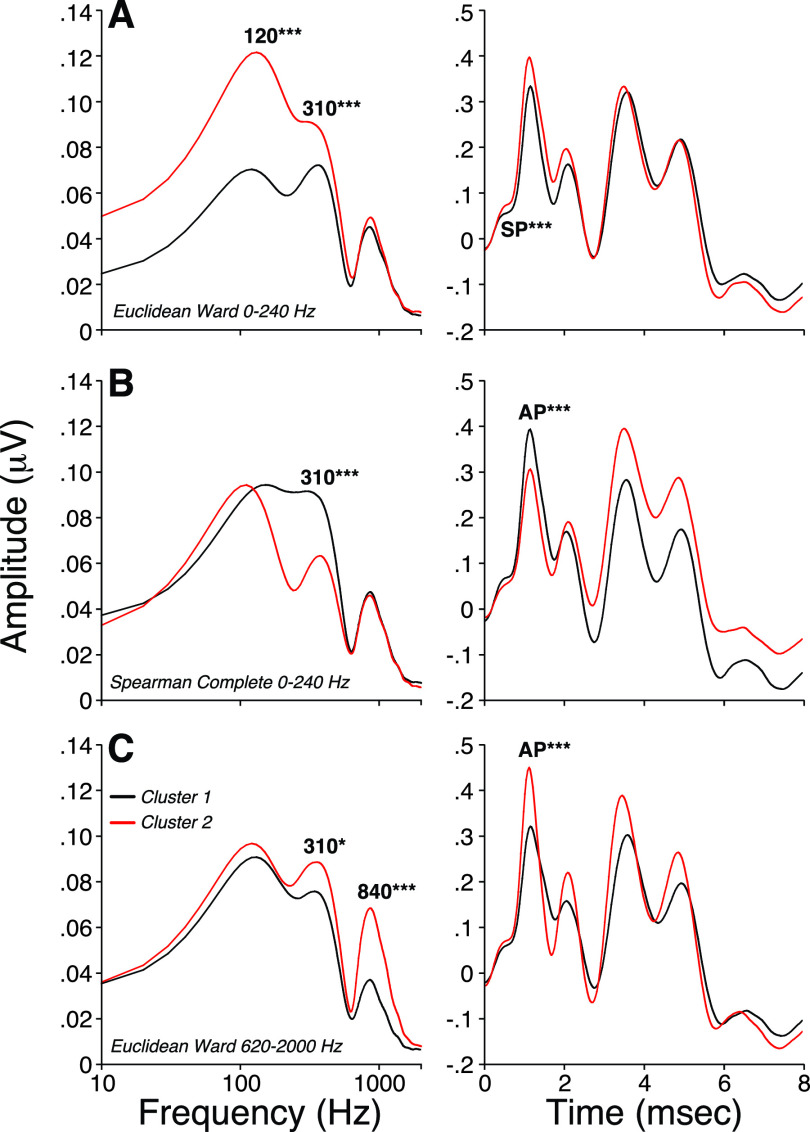

Another approach is to apply cluster analyses to objectively group each spectral peak in such a way that peak amplitudes within the same group (or cluster) are more similar to each other than to those in other groups. By doing so, we obtain clusters with maximal differences at either 120, 310, and 840 Hz, allowing us to evaluate the resultant mean time-domain waveforms. As shown in Fig. 7(A), maximizing differences in the energy near 120 Hz was associated with larger SP amplitudes without changes in AP. Maximizing spectral peaks at 310 Hz [Fig. 7(B)] or 840 Hz [Fig. 7(C)] was associated with larger AP responses without significant changes in SP. These results suggest that the spectral peak at 840 Hz is dominated by neural generators, the peak at 120 Hz most closely reflects the SP, and energy near 310 Hz contributes to both. The latter observation is consistent with the notion that SP has a neural component in addition to a hair cell component (Pappa et al., 2019).

FIG. 7.

(Color online) Hierarchical clustering analysis of spectra obtained from the first 8 ms post stimulus onset of ABR waveforms. Spearman and Euclidean correlations were used to compute the distance between each pair of observations. Rules of hierarchical clustering between pairs were based on either a Ward's method or a complete-linkage clustering method to define spectral groups. The cutting distance was set to separate all data into two clusters of similar size. Averaged ABR waveforms were obtained after identification of the participants composing each spectral group. Two-tailed Student's t test for homoscedastic groups were used to test for differences in mean spectral values at 120, 310, and 840 Hz or in mean SP, AP, and AP-P1 values obtained from ABR waveforms. * p < 0.05; *** p < 0.001.

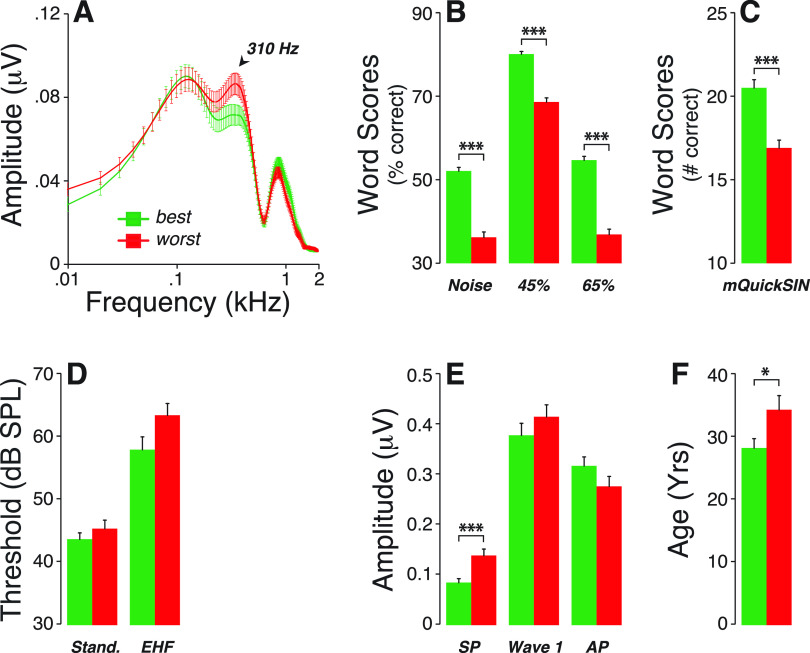

If true, and if cochlear neural deficits are associated with speech-in-noise difficulties (Alvord, 1983; Dubno et al., 1984; Rajan and Cainer, 2008; Kujawa and Liberman, 2015), the spectral peaks at either 310 or 840 Hz could be useful biomarkers. Thus, we compared average spectra from participants with the best vs worst word scores (i.e., with speech-in-noise recognition scores above the 75th and below the 25th percentile, respectively) [Figs. 8(A) to 8(C)]. Interestingly, the resultant mean spectra differed significantly only near 310 Hz, with larger peaks in those with poorer scores. This difference could not be attributed to inter-group differences in thresholds at standard audiometric frequencies or extended high frequencies [Fig. 8(D)] and was associated with larger SP amplitudes [Fig. 8(E)] and older ages [Fig. 8(F)].

FIG. 8.

(Color online) (A) Averaged FFT of ABR waveforms obtained from the best and worst performers on speech recognition tests. Participants who obtained the worst speech scores (B,C) were those with the largest 310-Hz spectral peak (A). While these differences in speech scores could not be attributed to differences in threshold at standard audiometric frequencies or extended high frequencies (D), they were associated with larger SP amplitudes (E) and older participants (F). * p < 0.05; *** p<0.001.

Looping back to the Gaussian model and the correspondence between model-fit and visual determination, we computed the mean FFTs of the good match vs poor match groups and noted that the 310-Hz peak was a source of differences between groups [Fig. 9(A)]. This inter-group difference was not associated with differences in thresholds [Fig. 9(B)] or age [Fig. 9(C)]. Remarkably, participants from the poor match group had larger SP and smaller AP amplitudes [Fig. 9(D)], and their word scores were significantly poorer than those from the good match group [Figs. 9(E) and 9(F)].

FIG. 9.

(Color online) (A) Averaged FFT of ABR waveforms obtained from the poor and good match groups as defined in Fig. 3 shows a larger spectral peak at 310 Hz in the poor match group. While no significant group differences in thresholds at standard audiometric frequencies or extended high frequencies (B) and age (C) were observed, SP was larger, AP was smaller (D) and all speech-in- noise test performances were poorer (E,F) in the poor match group. *p < 0.05; ***p < 0.001.

To compare the potential utility of each ABR quantification method in the context of CND markers, we computed their respective correlations with word scores for time-compressed words (65%) plus reverberation. Altogether, the thorough visual identification of SP using waveforms acquired under different conditions (e.g., fast vs slow repetition rate; with and without forward masking) and viewed without post hoc filtering provided the best prediction of speech-in-noise performance: r = –0.21, p = 0.0013 vs r = –0.04, p = 0.5458 for the Gaussian model, r = –0.07, p = 0.2993 for the 310-Hz peak, and r = 0.12, p = 0.0782 for the 840-Hz peak).

IV. DISCUSSION

The purpose of this study was to improve methods for SP quantification, as well as to gain insight into its underlying generators, given its role as potential CND marker in humans. Inspired by the work of Kamerer and colleagues (2020), we used a Gaussian model to extract SP and AP amplitudes and latencies from ABRs, which is traditionally achieved by visual inspection of a single waveform and prone to subjectivity. Using their model in a large cohort of normal-hearing participants, we obtained excellent agreement between model and visual determination of AP amplitude and latency; however, model performance in matching SP metrics was only moderate (Fig. 1). The discrepancies arose predominantly from cases in which the SP waveform presented with multiple ripples, which were not well fit by a single Gaussian waveform. Electrocochleographic studies of the effects of noise overexposure (Kim et al., 2005), Ménière's disease (Ferraro and Tibbils, 1999), or perilymphatic fistula (Sass et al., 1997) also showed SP waveforms with multiple inflection points similar to some of those observed in a subset of subjects in this study (Fig. 4, 102R).

Although the model fit was improved when the high-pass filter cutoff was moved from 10 to 300 Hz, the resulting attenuation of the low-frequency components of the SP is counterproductive to the overall purpose of our measurements. Our methodology has been to maximize SP amplitude by recording closer to its generators (e.g., with tiptrodes) using a horizontal montage, and by not filtering out the low-frequency energy (i.e., 10–300 Hz). A critical further step is to superimpose waveforms elicited under different stimulus conditions designed to differentially affect the AP (e.g., higher repetition rate or with a forward masker). This helps identify a common inflection point (e.g., Fig. 4), defining the SP peak at the last and common inflection preceding the fast rise to an AP peak.

Fourier transforms of the response waveforms could provide an alternative way to separate contributions from different cellular generators in auditory periphery and their relative contributions to AP and SP. As shown in Fig. 5(B), the mean FFT spectrum showed major peaks near 120, 310, and 840 Hz. A peak near 840 Hz was expected as (1) ABR waveforms have peaks that are separated by approximately 1 ms that, in itself, would lead to a spectral peak around 1 kHz and (2) animal studies of the background activity from gross electrodes at the round window show a spectrum with a broad peak from 0.8 to 1.0 kHz, even in the absence of acoustic stimulation (Dolan et al., 1990; Lima da Costa et al., 1997). The click-evoked wave 1, or AP as it is called in electrocochleographic recordings, comprises summed currents from action potentials in auditory nerve fibers, primarily those in the basal half of the cochlea, where the traveling wave moves rapidly and thus all fibers have a similar response latency (Kiang et al., 1976). The contribution of a single action potential (either spontaneous or sound-evoked) to an electrocochleographic recording at the round window is a small biphasic wave resembling one cycle of a sinusoid with a frequency near 800 Hz (Kiang et al., 1976; Prijs, 1986). The contribution of a single auditory nerve spike to an ABR-style scalp or meatal electrode montage must be similar in spectral content though smaller in amplitude. Thus, it is reasonable to associate the bulk of the 840 Hz spectral peak in the ABR recordings to auditory-nerve action potentials. This conclusion is further supported by (1) its absence in patients with auditory-neuropathy due to OTOF mutations (Fig. 5) and (2) the significant correlations of the spectral 840-Hz peak amplitude with AP (Fig. 6). Furthermore, clustering analyses meant to segregate spectra with low vs high energy at 840 Hz led to groups of waveforms with small vs large AP amplitudes, respectively (Fig. 7).

Since the SP has a shorter latency than AP, it must arise from hair cell receptor potentials and/or excitatory post-synaptic potentials (EPSPs) in auditory nerve synaptic terminals (Pappa et al., 2019). Early work using hair cell lesions came to differing conclusions about the relative importance of IHCs vs OHCs, but it was also clear that recording configuration was important and that there could be opposing polarities in the contributions from different generators (Dallos, 1975; Durrant et al., 1998). A recent gerbil study using kainate and tetrodotoxin to block post-synaptic potentials and action potentials, respectively, has suggested that SP includes contributions from both hair cells and auditory-nerve dendrites (Pappa et al., 2019), and that the polarities of the neural and hair cell contributions can be opposite in sign. Human studies have also hinted at a neural contribution to the SP. We and others have noted that both wave 1 and SP are reduced with increased stimulus presentation rate (Santarelli et al., 2008; Santarelli et al., 2009; Grant et al., 2020), although hair cell potentials should be robust to changes in repetition rate (Kiang and Peake, 1960).

In a study where normal-hearing participants were evaluated before and after a temporary threshold shift following a night of noisy clubbing, a decrease in wave 1 amplitude was paired with an increase in SP amplitude (Kim et al., 2005). These results echo our prior studies where SP amplitude was larger in participants who performed more poorly on word-recognition tests (Liberman et al., 2016; Grant et al., 2020; Mepani et al., 2020). One interpretation of these paradoxical findings is that a rise in SP amplitudes can result from a fall in one of the components (e.g., EPSPs), if its polarity is opposite to the less affected one (e.g., hair cell contributions).

The spectral peak at 310 Hz was absent in patients with genetic defects in OTOF, a key protein mediating synaptic transmission (Fig. 5), suggesting that it is not dominated by hair cell receptor potentials, which should be reasonably normal in such patients. Correspondingly, spectral amplitudes at 310 Hz were correlated with both the AP and SP amplitudes from ABR waveforms (Fig. 6), suggesting that both may contain contributions from the generators with energy around 310 Hz.

Animal studies have shown that excitatory post-synaptic currents recorded from afferent boutons contacting inner hair cells can be either monophasic or multiphasic, and both types persist in mature animals (Grant et al., 2010). Monophasic EPSCs have a periodicity close to 800 Hz, while multiphasic EPSCs appear to have significant spectral content near 300 Hz. Thus, the latter could represent an important contributor to the 310 Hz peak in the ABR spectra, which in turn was associated with SP amplitudes (Fig. 6), again suggesting a contribution of cochlear neural potentials to the SP.

Clustering of spectra based on the 310-Hz peak amplitude led to ECochG waveforms with significant differences in AP amplitudes; yet, when clustering was based on spectral differences at both 120 and 310 Hz, associated waveforms showed significant differences only in SP amplitudes (Fig. 7). The 120 Hz peak almost certainly includes a contribution from hair cell receptor potentials. The basilar membrane response to a high-level click throughout the basal turn should be a damped sinusoid, which will produce a DC response in the inner hair cells, decaying over a few ms, and thereby producing a signal which could well have peak energy near 120 Hz.

Difficulty hearing in noisy environments is one of the classic impairments associated with sensorineural hearing loss. CND could be a major contributor to those speech intelligibility deficits as it affects primarily the cochlear neurons with high thresholds and low spontaneous rates (SRs) (Schmiedt et al., 1996; Furman et al., 2013), the same neurons that are key to the coding of transient stimuli in the presence of background noise (Costalupes et al., 1984). By definition, CND will affect the connections between the auditory-nerve terminals and their peripheral targets, the inner hair cells. We suspect that those post-synaptic boutons, shown to contribute to the generation of the SP in gerbils (Pappa et al., 2019), provide some energy to the 310-Hz spectral peak of ABR waveforms. If true, loss or dysfunction of the synapse ought to impact the 310-Hz component of ABR waveform spectra. Likewise, if CND is associated with speech-in-noise deficits (Bramhall et al., 2015; Gilles et al., 2016; Liberman et al., 2016; Ridley et al., 2018; Buran et al., 2020; Grant et al., 2020; Mepani et al., 2021; Shehorn et al., 2020), differences in word recognition performance ought to be linked with differences in the magnitude of the 310-Hz spectral peak. As shown in Fig. 8, when we considered two cohorts with similar thresholds (at standard and extended high frequencies) and large differences in worst scores, we found that the 310-Hz component was the only spectral peak significantly different across groups. Participants with larger peak magnitudes were those with the worst performances on word recognition tests (Fig. 8). They were also older and had larger SP amplitudes on ABR waveforms, both features consistent with CND (Wu et al., 2019; Grant et al., 2020).

V. CONCLUSIONS

-

(1)

Identification of SP and AP peaks by a two-Gaussian model is slightly improved by constraining one of the Gaussians to a user-supplied AP latency and significantly improved by high-pass filtering. However, the latter comes at the expense of attenuating the SP amplitude, which is an unacceptable outcome.

-

(2)

The strongest correlations between an electrophysiological measure and performance on speech in noise tests was the SP amplitude, as measured visually by comparing unfiltered ABR waveforms acquired under different repetition rate and masking conditions designed to have a differential effect on SP and AP amplitudes.

-

(3)

FFT analysis of ABR waveforms suggests that SP generators also dominate a spectral peak at 310 Hz, which, in turn, may include a strong contribution from excitatory post-synaptic potentials in auditory nerve terminals as well as from hair cell receptor potentials.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This work was supported by the NIH Grant No. NIDCD P50 DC015857.

References

- 1. Alvord, L. S. (1983). “ Cochlear dysfunction in ‘normal-hearing’ patients with history of noise exposure,” Ear Hear. 4, 247–250. 10.1097/00003446-198309000-00005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Arnold, S. A. (1985). “ Objective versus visual detection of the auditory brain stem response,” Ear Hear. 6, 144–150. 10.1097/00003446-198505000-00004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Boston, J. R. , and Moller, A. R. (1985). “ Brainstem auditory-evoked potentials,” Crit. Rev. Biomed. Eng. 13, 97–123. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Bramhall, N. , Ong, B. , Ko, J. , and Parker, M. (2015). “ Speech perception ability in noise is correlated with auditory brainstem response wave I amplitude,” J. Am. Acad. Audiol. 26, 509–517. 10.3766/jaaa.14100 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Buran, B. N. , McMillan, G. , Keshishzadeh, S. , Verhulst, S. , and Bramhall, N. (2020). “ Predicting synapse counts in living humans by combining computational models with auditory physiology,” OSF Preprints. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 6. Chambers, A. R. , Resnik, J. , Yuan, Y. , Whitton, J. P. , Edge, A. S. , Liberman, M. C. , and Polley, D. B. (2016). “ Central gain restores auditory processing following near-complete cochlear denervation,” Neuron 89, 867–879. 10.1016/j.neuron.2015.12.041 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Costalupes, J. A. , Young, E. D. , and Gibson, D. J. (1984). “ Effects of continuous noise backgrounds on rate response of auditory nerve fibers in cat,” J. Neurophysiol. 51, 1326–1344. 10.1152/jn.1984.51.6.1326 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Dallos, P. (1975). “ Electrical correlates of mechanical events in the cochlea,” Audiology 14, 408–418. 10.3109/00206097509071753 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Dolan, D. F. , Nuttall, A. L. , and Avinash, G. (1990). “ Asynchronous neural activity recorded from the round window,” J. Acoust. Soc. Am. 87, 2621–2627. 10.1121/1.399054 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Dubno, J. R. , Dirks, D. D. , and Morgan, D. E. (1984). “ Effects of age and mild hearing loss on speech recognition in noise,” J. Acoust. Soc. Am. 76, 87–96. 10.1121/1.391011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Durrant, J. D. , and Ferraro, J. A. (1991). “ Analog model of human click-elicited SP and effects of high-pass filtering,” Ear Hear. 12, 144–148. 10.1097/00003446-199104000-00011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Durrant, J. D. , Wang, J. , Ding, D. L. , and Salvi, R. J. (1998). “ Are inner or outer hair cells the source of summating potentials recorded from the round window?,” J. Acoust. Soc. Am. 104, 370–377. 10.1121/1.423293 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Ferraro, J. A. , and Krishnan, G. (1997). “ Cochlear potentials in clinical audiology,” Audiol. Neurootol. 2, 241–256. 10.1159/000259251 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Ferraro, J. A. , and Tibbils, R. P. (1999). “ SP/AP area ratio in the diagnosis of Meniere's disease,” Am. J. Audiol. 8, 21–28. 10.1044/1059-0889(1999/001) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Furman, A. C. , Kujawa, S. G. , and Liberman, M. C. (2013). “ Noise-induced cochlear neuropathy is selective for fibers with low spontaneous rates,” J. Neurophysiol. 110, 577–586. 10.1152/jn.00164.2013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Gilles, A. , Schlee, W. , Rabau, S. , Wouters, K. , Fransen, E. , and Van de Heyning, P. (2016). “ Decreased speech-in-noise understanding in young adults with tinnitus,” Front. Neurosci. 10, 288. 10.3389/fnins.2016.00288 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Gorga, M. P. , Kaminski, J. R. , Beauchaine, K. A. , and Jesteadt, W. (1988). “ Auditory brainstem responses to tone bursts in normally hearing subjects,” J. Speech Hear. Res. 31, 87–97. 10.1044/jshr.3101.87 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Grant, K. J. , Mepani, A. M. , Wu, P. , Hancock, K. E. , de Gruttola, V. , Liberman, M. C. , and Maison, S. F. (2020). “ Electrophysiological markers of cochlear function correlate with hearing-in-noise performance among audiometrically normal subjects,” J. Neurophysiol. 124, 418–431. 10.1152/jn.00016.2020 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Grant, L. , Yi, E. , and Glowatzki, E. (2010). “ Two modes of release shape the postsynaptic response at the inner hair cell ribbon synapse,” J. Neurosci. 30, 4210–4220. 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4439-09.2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Harder, H. , and Arlinger, S. (1981). “ Ear-canal compared to mastoid electrode placement in BRA,” Scand. Audiol. Suppl. 13, 55–57. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Jerger, J. , and Hall, J. (1980). “ Effects of age and sex on auditory brainstem response,” Arch. Otolaryngol. 106, 387–391. 10.1001/archotol.1980.00790310011003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Kamerer, A. M. , Neely, S. T. , and Rasetshwane, D. M. (2020). “ A model of auditory brainstem response wave I morphology,” J. Acoust. Soc. Am. 147, 25–31. 10.1121/10.0000493 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Kara, E. , Aydin, K. , Akbulut, A. A. , Karakol, S. N. , Durmaz, S. , Yener, H. M. , Gozen, E. D. , and Kara, H. (2020). “ Assessment of hiadden hearing loss in normal hearing individuals with and without tinnitus,” J. Int. Adv. Otol. 16, 87–92. 10.5152/iao.2020.7062 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Kiang, N. Y. , and Peake, W. (1960). “ Components of electrical responses recorded from the cochlea,” Ann. Otol. Rhinol. Laryngol. 69, 448–458. 10.1177/000348946006900213 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Kiang, N. Y. S. , Moxon, E. C. , and Kahn, A. R. (1976). “ The relationship of gross potentials recorded from the cochlea to single unit activity in the auditory nerve,” in Electrocochleography, edited by Ruben R. J., Eberling C., and Solomon G. ( University Park, Baltimore: ). [Google Scholar]

- 26. Kim, J. S. , Nam, E. C. , and Park, S. I. (2005). “ Electrocochleography is more sensitive than distortion-product otoacoustic emission test for detecting noise-induced temporary threshold shift,” J. Am. Acad. Otolaryngol. Head Neck Surg. 133, 619–624. 10.1016/j.otohns.2005.06.012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Koo, T. K. , and Li, M. Y. (2016). “ A guideline of selecting and reporting intraclass correlation coefficients for reliability research,” J. Chiropr. Med. 15, 155–163. 10.1016/j.jcm.2016.02.012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Kujawa, S. G. , and Liberman, M. C. (2009). “ Adding insult to injury: Cochlear nerve degeneration after ‘temporary’ noise-induced hearing loss,” J. Neurosci. 29, 14077–14085. 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2845-09.2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Kujawa, S. G. , and Liberman, M. C. (2015). “ Synaptopathy in the noise-exposed and aging cochlea: Primary neural degeneration in acquired sensorineural hearing loss,” Hear. Res. 330, 191–199. 10.1016/j.heares.2015.02.009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Lang, A. H. , Happonen, J. M. , and Salmivalli, A. (1981). “ An improved technique for the non-invasive recording of auditory brain-stem responses with a specially constructed meatal electrode,” Scand. Audiol. Suppl. 13, 59–62. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Laughlin, N. K. , Hartup, B. K. , Lasky, R. E. , Meier, M. M. , and Hecox, K. E. (1999). “ The development of auditory event related potentials in the rhesus monkey (Macaca mulatta),” Dev. Psychobiol. 34, 37–56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Liberman, M. C. , Epstein, M. J. , Cleveland, S. S. , Wang, H. , and Maison, S. F. (2016). “ Toward a differential diagnosis of hidden hearing loss in humans,” PloS One 11, e0162726. 10.1371/journal.pone.0162726 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Lima da Costa, D. , Erre, J. P. , Charlet de Sauvage, R. , Popelar, J. , and Aran, J. M. (1997). “ Bioelectrical cochlear noise and its contralateral suppression: Relation to background activity of the eighth nerve and effects of sedation and anesthesia,” Exp. Brain Res. 116, 259–269. 10.1007/PL00005754 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Lobarinas, E. , Salvi, R. , and Ding, D. (2020). “ Gap detection deficits in chinchillas with selective carboplatin-induced inner hair cell loss,” J. Assoc. Res. Otolaryngol. 21, 475–483. 10.1007/s10162-020-00744-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Mepani, A. M. , Kirk, S. A. , Hancock, K. E. , Bennett, K. , de Gruttola, V. , Liberman, M. C. , and Maison, S. F. (2020). “ Middle ear muscle reflex and word recognition in ‘normal-hearing’ adults: Evidence for cochlear synaptopathy?,” Ear Hear. 41, 25–38. 10.1097/AUD.0000000000000804 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Mepani, A. M. , Verhulst, S. , Hancock, K. E. , Garrett, M. , Vasilkov, V. , Bennett, K. , de Gruttola, V. , Liberman, M. C. , and Maison, S. F. (2021). “ Envelope following responses predict speech-in-noise performance in normal hearing listeners,” J. Neurophysiol. 125, 1213–1222. 10.1152/jn.00620.2020 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Michalewski, H. J. , Thompson, L. W. , Patterson, J. V. , Bowman, T. E. , and Litzelman, D. (1980). “ Sex differences in the amplitudes and latencies of the human auditory brain stem potential,” Electroencephalogr. Clin. Neurophysiol. 48, 351–356. 10.1016/0013-4694(80)90271-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Monaghan, J. J. M. , Garcia-Lazaro, J. A. , McAlpine, D. , and Schaette, R. (2020). “ Hidden hearing loss impacts the neural representation of speech in background noise,” Curr. Biol. 30, 4710–4721. 10.1016/j.cub.2020.09.046 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Nikiforidis, G. C. , Koutsojannis, C. M. , Varakis, J. N. , and Goumas, P. D. (1993). “ Reduced variance in the latency and amplitude of the fifth wave of auditory brain stem response after normalization for head size,” Ear Hear. 14, 423–428. 10.1097/00003446-199312000-00008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Pappa, A. K. , Hutson, K. A. , Scott, W. C. , Wilson, J. D. , Fox, K. E. , Masood, M. M. , Giardina, C. K. , Pulver, S. H. , Grana, G. D. , Askew, C. , and Fitzpatrick, D. C. (2019). “ Hair cell and neural contributions to the cochlear summating potential,” J. Neurophysiol. 121, 2163–2180. 10.1152/jn.00006.2019 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Prijs, V. F. (1986). “ Single-unit response at the round window of the guinea pig,” Hear. Res. 21, 127–133. 10.1016/0378-5955(86)90034-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Rajan, R. , and Cainer, K. E. (2008). “ Ageing without hearing loss or cognitive impairment causes a decrease in speech intelligibility only in informational maskers,” Neuroscience 154, 784–795. 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2008.03.067 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Resnik, J. , and Polley, D. B. (2021). “ Cochlear neural degeneration disrupts hearing in background noise by increasing auditory cortex internal noise,” Neuron 109, 984–996. 10.1016/j.neuron.2021.01.015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Ridley, C. L. , Kopun, J. G. , Neely, S. T. , Gorga, M. P. , and Rasetshwane, D. M. (2018). “ Using thresholds in noise to identify hidden hearing loss in humans,” Ear Hear. 39, 829–844. 10.1097/AUD.0000000000000543 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Santarelli, R. , Del Castillo, I. , Rodriguez-Ballesteros, M. , Scimemi, P. , Cama, E. , Arslan, E. , and Starr, A. (2009). “ Abnormal cochlear potentials from deaf patients with mutations in the otoferlin gene,” J. Assoc. Res. Otolaryngol. 10, 545–556. 10.1007/s10162-009-0181-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Santarelli, R. , La Morgia, C. , Valentino, M. L. , Barboni, P. , Monteleone, A. , Scimemi, P. , and Carelli, V. (2019). “ Hearing dysfunction in a large family affected by dominant optic atrophy (OPA8-related DOA): A human model of hidden auditory neuropathy,” Front. Neurosci. 13, 501. 10.3389/fnins.2019.00501 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Santarelli, R. , Starr, A. , Michalewski, H. J. , and Arslan, E. (2008). “ Neural and receptor cochlear potentials obtained by transtympanic electrocochleography in auditory neuropathy,” Clin. Neurophysiol. 119, 1028–1041. 10.1016/j.clinph.2008.01.018 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Sass, K. , Densert, B. , and Magnusson, M. (1997). “ Transtympanic electrocochleography in the assessment of perilymphatic fistulas,” Audiol. Neurootol. 2, 391–402. 10.1159/000259264 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Schmiedt, R. A. , Mills, J. H. , and Boettcher, F. A. (1996). “ Age-related loss of activity of auditory-nerve fibers,” J. Neurophysiol. 76, 2799–2803. 10.1152/jn.1996.76.4.2799 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Schwartz, D. M. , and Berry, G. A. (1985). “ Normative aspects of the ABR,” in The Auditory Brainstem Response, edited by Jacobson J. T. ( College-Hill Press, San Diego: ), pp. 65–97. [Google Scholar]

- 51. Sergeyenko, Y. , Lall, K. , Liberman, M. C. , and Kujawa, S. G. (2013). “ Age-related cochlear synaptopathy: An early-onset contributor to auditory functional decline,” J. Neurosci. 33, 13686–13694. 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1783-13.2013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Shehorn, J. , Strelcyk, O. , and Zahorik, P. (2020). “ Associations between speech recognition at high levels, the middle ear muscle reflex and noise exposure in individuals with normal audiograms,” Hear. Res. 392, 107982. 10.1016/j.heares.2020.107982 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Valderrama, J. T. , de la Torre, A. , Alvarez, I. , Segura, J. C. , Thornton, A. R. , Sainz, M. , and Vargas, J. L. (2014). “ Automatic quality assessment and peak identification of auditory brainstem responses with fitted parametric peaks,” Comput. Methods Programs Biomed. 114, 262–275. 10.1016/j.cmpb.2014.02.015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Viana, L. M. , O'Malley, J. T. , Burgess, B. J. , Jones, D. D. , Oliveira, C. A. , Santos, F. , Merchant, S. N. , Liberman, L. D. , and Liberman, M. C. (2015). “ Cochlear neuropathy in human presbycusis: Confocal analysis of hidden hearing loss in post-mortem tissue,” Hear Res. 327, 78–88. 10.1016/j.heares.2015.04.014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Walter, B. , and Blegvad, B. (1981). “ ABR following severe head trauma. A study of click-evoked and frequency-following responses,” Scand. Audiol. Suppl. 13, 125–130. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Wu, P. Z. , Liberman, L. D. , Bennett, K. , de Gruttola, V. , O'Malley, J. T. , and Liberman, M. C. (2019). “ Primary neural degeneration in the human cochlea: Evidence for hidden hearing loss in the aging ear,” Neurosci. 407, 8–20. 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2018.07.053 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]