Abstract

Background

Implanted spinal neuromodulation (SNMD) techniques are used in the treatment of refractory chronic pain. They involve the implantation of electrodes around the spinal cord (spinal cord stimulation (SCS)) or dorsal root ganglion (dorsal root ganglion stimulation (DRGS)), and a pulse generator unit under the skin. Electrical stimulation is then used with the aim of reducing pain intensity.

Objectives

To evaluate the efficacy, effectiveness, adverse events, and cost‐effectiveness of implanted spinal neuromodulation interventions for people with chronic pain.

Search methods

We searched CENTRAL, MEDLINE Ovid, Embase Ovid, Web of Science (ISI), Health Technology Assessments, ClinicalTrials.gov and World Health Organization International Clinical Trials Registry from inception to September 2021 without language restrictions, searched the reference lists of included studies and contacted experts in the field.

Selection criteria

We included randomised controlled trials (RCTs) comparing SNMD interventions with placebo (sham) stimulation, no treatment or usual care; or comparing SNMD interventions + another treatment versus that treatment alone. We included participants ≥ 18 years old with non‐cancer and non‐ischaemic pain of longer than three months duration. Primary outcomes were pain intensity and adverse events. Secondary outcomes were disability, analgesic medication use, health‐related quality of life (HRQoL) and health economic outcomes.

Data collection and analysis

Two review authors independently screened database searches to determine inclusion, extracted data and evaluated risk of bias for prespecified results using the Risk of Bias 2.0 tool. Outcomes were evaluated at short‐ (≤ one month), medium‐ four to eight months) and long‐term (≥12 months). Where possible we conducted meta‐analyses. We used the GRADE system to assess the certainty of evidence.

Main results

We included 15 unique published studies that randomised 908 participants, and 20 unique ongoing studies. All studies evaluated SCS. We found no eligible published studies of DRGS and no studies comparing SCS with no treatment or usual care. We rated all results evaluated as being at high risk of bias overall. For all comparisons and outcomes where we found evidence, we graded the certainty of the evidence as low or very low, downgraded due to limitations of studies, imprecision and in some cases, inconsistency.

Active stimulation versus placebo

SCS versus placebo (sham)

Results were only available at short‐term follow‐up for this comparison.

Pain intensity

Six studies (N = 164) demonstrated a small effect in favour of SCS at short‐term follow‐up (0 to 100 scale, higher scores = worse pain, mean difference (MD) ‐8.73, 95% confidence interval (CI) ‐15.67 to ‐1.78, very low certainty). The point estimate falls below our predetermined threshold for a clinically important effect (≥10 points). No studies reported the proportion of participants experiencing 30% or 50% pain relief for this comparison.

Adverse events (AEs)

The quality and inconsistency of adverse event reporting in these studies precluded formal analysis.

Active stimulation + other intervention versus other intervention alone

SCS + other intervention versus other intervention alone (open‐label studies)

Pain intensity

Mean difference

Three studies (N = 303) demonstrated a potentially clinically important mean difference in favour of SCS of ‐37.41 at short term (95% CI ‐46.39 to ‐28.42, very low certainty), and medium‐term follow‐up (5 studies, 635 participants, MD ‐31.22 95% CI ‐47.34 to ‐15.10 low‐certainty), and no clear evidence for an effect of SCS at long‐term follow‐up (1 study, 44 participants, MD ‐7 (95% CI ‐24.76 to 10.76, very low‐certainty).

Proportion of participants reporting ≥50% pain relief

We found an effect in favour of SCS at short‐term (2 studies, N = 249, RR 15.90, 95% CI 6.70 to 37.74, I2 0% ; risk difference (RD) 0.65 (95% CI 0.57 to 0.74, very low certainty), medium term (5 studies, N = 597, RR 7.08, 95 %CI 3.40 to 14.71, I2 = 43%; RD 0.43, 95% CI 0.14 to 0.73, low‐certainty evidence), and long term (1 study, N = 87, RR 15.15, 95% CI 2.11 to 108.91 ; RD 0.35, 95% CI 0.2 to 0.49, very low certainty) follow‐up.

Adverse events (AEs)

Device related

No studies specifically reported device‐related adverse events at short‐term follow‐up. At medium‐term follow‐up, the incidence of lead failure/displacement (3 studies N = 330) ranged from 0.9 to 14% (RD 0.04, 95% CI ‐0.04 to 0.11, I2 64%, very low certainty). The incidence of infection (4 studies, N = 548) ranged from 3 to 7% (RD 0.04, 95%CI 0.01, 0.07, I2 0%, very low certainty). The incidence of reoperation/reimplantation (4 studies, N =5 48) ranged from 2% to 31% (RD 0.11, 95% CI 0.02 to 0.21, I2 86%, very low certainty). One study (N = 44) reported a 55% incidence of lead failure/displacement (RD 0.55, 95% CI 0.35, 0 to 75, very low certainty), and a 94% incidence of reoperation/reimplantation (RD 0.94, 95% CI 0.80 to 1.07, very low certainty) at five‐year follow‐up. No studies provided data on infection rates at long‐term follow‐up.

We found reports of some serious adverse events as a result of the intervention. These included autonomic neuropathy, prolonged hospitalisation, prolonged monoparesis, pulmonary oedema, wound infection, device extrusion and one death resulting from subdural haematoma.

Other

No studies reported the incidence of other adverse events at short‐term follow‐up. We found no clear evidence of a difference in otherAEs at medium‐term (2 studies, N = 278, RD ‐0.05, 95% CI ‐0.16 to 0.06, I2 0%) or long term (1 study, N = 100, RD ‐0.17, 95% CI ‐0.37 to 0.02) follow‐up.

Very limited evidence suggested that SCS increases healthcare costs. It was not clear whether SCS was cost‐effective.

Authors' conclusions

We found very low‐certainty evidence that SCS may not provide clinically important benefits on pain intensity compared to placebo stimulation. We found low‐ to very low‐certainty evidence that SNMD interventions may provide clinically important benefits for pain intensity when added to conventional medical management or physical therapy. SCS is associated with complications including infection, electrode lead failure/migration and a need for reoperation/re‐implantation. The level of certainty regarding the size of those risks is very low. SNMD may lead to serious adverse events, including death. We found no evidence to support or refute the use of DRGS for chronic pain.

Plain language summary

What are the benefits and risks of electrical spinal cord and dorsal root ganglion stimulation for the treatment of chronic pain in adults?

Why this question is important

Persistent (chronic) pain is a common problem that affects people from all walks of life. It can be the result of a wide range of different medical conditions and is sometimes unexplained, but it often causes substantial suffering, distress and disability and can have major impacts on a person's quality of life.

Implanted spinal neuromodulation (SNMD) interventions involve surgically implanting wires (electrodes) into the space around nerves or the spinal cord that are connected to a "pulse generator" device which is usually implanted under the patient's skin. This delivers electrical stimulation to the nerves or spinal cord. It is thought that this stimulation interferes with danger messages being sent to the spinal cord and brain with the goal of reducing the perception of pain. Once implanted with a SNMD device people live with the device implanted, potentially on a permanent basis. We reviewed the evidence to find out whether these interventions were effective at reducing pain, disability and medication use, at improving quality of life and to find out the risk and type of complications they might cause. There are two broad types of SNMD: spinal cord stimulation (SCS), where electrodes are placed near the spinal cord and dorsal root ganglion stimulation (DRGS) where electrodes are placed near the nerve root, where the nerve branches off from the spinal cord.

How we identified and assessed the evidence

First, we searched for all relevant studies in the medical literature. We then compared the results, and summarised the evidence from all the studies. Finally, we assessed the certainty of the evidence. We considered factors such as the way studies were conducted, study sizes, and consistency of findings across studies. Based on our assessments, we rated the evidence as being of very low, low, moderate or high certainty.

What we found

We found 15 published studies that included 908 people with persistent pain due to a variety of causes including nerve disease, chronic low back pain, chronic neck pain and complex regional pain syndrome. All of these studies evaluated SCS; no studies evaluated DRGS.

Eight studies (that included 205 people) compared SCS with a sham (placebo) stimulation, where the electrodes were implanted, but no stimulation was delivered. Six studies that included 684 people compared SCS added with either medical management or physical therapy with medical management or physical therapy on its own. We rated the evidence as being of low, or very low certainty. Limitations in how the studies were conducted and reported, the amount of evidence we found and inconsistency between studies in some instances means that our confidence in the results is limited.

The evidence suggests the following.

Compared to receiving medical management or physical therapy alone, people treated with the addition of SCS may experience less pain and higher quality of life after one month or six months of stimulation. There is limited evidence to draw conclusions in the long term of one year or more. It is unclear whether SCS reduces disability or medication use.

Compared to a sham (placebo) stimulation, SCS may result in small reductions in pain intensity in the short term that may not be clinically important, but this is currently unclear. There is no evidence at medium or long‐term follow‐up points.

SCS can result in complications. These include movement or malfunction of the electrode wires, wound infections and the need for further surgical procedures to fix issues with the implanted devices. We also found instances of serious complications that included one death, nerve damage, lasting muscle weakness, lung injury, serious infection, prolonged hospital stay and the extrusion of a stimulation device through the skin.

Very limited evidence around the costs and economics of SCS suggested that SCS increases the costs of healthcare. It was not clear whether SCS was cost‐effective.

What this means

SCS may reduce pain intensity in people with chronic pain. It is currently not clear how much of this effect is due to the SCS itself and how much is due to so‐called "placebo" effects, which are the result of the experience of undergoing the procedure and the person's expectations that it will help them. Receiving SCS does present a risk of relatively common complications and less common serious complications. We are currently unsure of the precise degree of this risk.

How up‐to‐date is this review?

The evidence in this review is current to September 2021.

Summary of findings

Background

Description of the condition

Chronic pain is a common problem. Global burden of disease data indicate that chronic pain is a leading cause of years lived with disability, with painful conditions comprising 4 of 10 leading causes of disability in both developed and developing countries (Rice 2016; Vos 2015). Chronic pain impacts the physical and mental health and quality of life of those who experience it (Moore 2014; Sylwander 2020), but it also has a substantial economic impact on society, in terms of reduced productivity, participation, and healthcare utilisation (Gaskin 2012; Gustavsson 2012).

Chronic pain is a heterogenous phenomenon with a wide variety of potential causes. These include nociceptive pain conditions, in which there is clear evidence of ongoing peripheral tissue pathology, such as rheumatoid arthritis; neuropathic pain, in which the pain arises as a result of identifiable nerve injury or disease, for example diabetic neuropathy; and many other chronic pain problems, such as fibromyalgia and chronic low back pain, in which the relationship between peripheral tissue pathology and clinical symptoms is less clear. In 2016, the term 'nociplastic pain' was added to the International Association for the Study of Pain (IASP) taxonomy of pain in an attempt to classify this latter group (Kosek 2016). It is likely that different mechanisms underpin these different types of chronic pain, though current understanding of those mechanisms is incomplete (Ossipov 2006; Vardeh 2016). In 2019, chronic pain was formally classified in the International Classification of Diseases (ICD‐11) under the categories of 'chronic primary pain', characterised by disability or emotional distress not attributable to another diagnosis, and 'chronic secondary pain', when the pain is a symptom of an identifiable underlying condition (Detlef‐Treede 2019).

Description of the intervention

Electrical stimulation of neural structures, commonly labelled 'neuromodulation', is becoming an increasingly common intervention for the treatment of chronic pain. In this review, we will focus on neuromodulation procedures that stimulate the spinal cord or the nerve roots that arise directly from the spinal cord, which involve the implantation of electrodes into the epidural space around the spinal cord (spinal cord stimulation (SCS)) or dorsal root ganglion (dorsal root ganglion stimulation (DRGS)). Electrodes can be implanted either surgically or percutaneously. These electrodes remain in situ, and are connected to a portable battery‐powered stimulation unit 'pulse generator' that is either implanted under the skin or worn by the person, and delivers electrical stimulation to the neural structures. The procedure usually consists of a trial phase, with temporary electrode leads attached to an external wearable device, followed by the implantation of permanent electrode leads attached to a pulse generator that is implanted under the skin (Patel 2015).

There are various types of spinal neuromodulation devices (SNMDs), and approaches may differ in terms of the surgical approach taken, the neural structures targeted, the device and equipment, and the parameters of electrical stimulation delivered to the tissues. While novel approaches to stimulation continue to be reported, current stimulation parameters can be classified into the following broad categories (Sdrulla 2018).

Conventional stimulation: involves the delivery of a tonic pulse, at a constant stimulation frequency between 40 Hz and 80 Hz, with a fixed pulse width.

High frequency stimulation: involves the delivery of a tonic pulse, at a frequency between 1 kHz and 10 kHz, with a fixed pulse width.

Burst stimulation: involves the delivery of intermittent trains of stimulation, though the stimulation parameters may vary.

High frequency and burst stimulation approaches differ from conventional stimulation approaches, as they do not induce paraesthesia (tingling) sensations. This potentially improves the tolerability of the intervention, and offers the advantage of allowing the use of sham stimulation under blinded conditions as a comparator in clinical trials, to control for placebo effects (Kjaer 2019). Spinal neuromodulation interventions are typically offered to people whose pain has been refractory to other interventions. They may include pharmacological, surgical, rehabilitation, or a combination of approaches.

How the intervention might work

The fundamental rationale common to all spinal neuromodulation approaches is that the stimulation of neural tissue may impact the processing of nociceptive input from nerve fibres from the painful body area, may alter the excitability (readiness to fire) of nerve cells in the target region, and may have upstream or downstream effects on neural activity in related structures in both the peripheral and central nervous system (Jensen 2019; Sdrulla 2018). It is proposed that neuromodulation techniques can reduce pain by altering the behaviour of the structures that are involved in the generation of the experience of pain. The precise mechanisms by which neuromodulation techniques might reduce pain are not known, and debate continues on which specific nerve structures are activated by SNMD, or which are optimal to achieve the greatest pain relief (Caylor 2019; Jensen 2019; Sdrulla 2018). It is proposed that DRGS and SCS may have distinct analgesic effects due to their respective direct actions on DRG nerve cells, or those in the dorsal column of the spinal cord (Deer 2017; Esposito 2019). While it is possible that different stimulation locations (SCS or DRGS) or parameters (conventional, high frequency, or burst stimulation) might elicit clinical effects through distinct mechanistic pathways, this is yet to be convincingly demonstrated in mechanistic studies (Sdrulla 2018).

Why it is important to do this review

Implanted spinal neuromodulation interventions are becoming a common option for the treatment of chronic pain, particularly for people who have not improved with drug or non‐invasive therapies (Prager 2010). In the Cochrane Library, there are no up‐to‐date reviews specifically focusing on these interventions for non‐cancer and non‐ischaemic pain. A 2013 overview of reviews of interventions for complex regional pain syndrome concluded that there was only very low‐quality evidence that SCS was effective for that condition, and that adverse events appeared to be frequent (O'Connell 2013).

In 2005, a review of health technology appraisals from the Ontario Ministry of Health and Long‐term Care concluded that weak‐to moderate‐quality evidence supported the use of SCS to decrease pain in neuropathic pain conditions (MoH‐LTC 2005). In the UK, the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) recommended SCS for people with chronic pain of neuropathic origin who had not responded to conventional medical management, based on a technology appraisal, the searches for which have not been updated since 2014 (NICE 2008). That appraisal considered no placebo‐controlled studies, and only two small trials in populations with failed back surgery syndrome and complex regional pain syndrome. In 2019, a new technology appraisal from NICE focused specifically on a proprietary high‐frequency spinal cord neuromodulation device (SENZA), and recommended the system for chronic neuropathic back or leg pain after failed back surgery, despite conventional medical management, based on limited evidence from two small trials with contradictory findings (NICE 2019). In 2016, the European Academy of Neurology (EAN) guidelines on central neurostimulation therapy in chronic pain conditions, made a weak recommendation to add SCS to medical management in painful diabetic neuropathy, chronic post‐surgical back and leg pain, and complex regional pain syndrome (CRPS) type I, and recommended offering SCS instead of reoperation in chronic low back pain (Cruccu 2016). They highlighted the quality of the evidence as a key issue.

While these guidance documents have made recommendations for the use of these interventions, they have done so from a limited evidence base. Given the relative costs of the treatment, and its invasive nature, there is need for a rigorous, and up‐to‐date review of the efficacy, effectiveness, cost‐effectiveness, and safety of the full range of these interventions, completed to Cochrane standards. This review aims to provide valuable information for people with chronic pain who have been offered, or who are considering these interventions, clinicians who work with people with chronic pain, clinical guideline organisations, and policy makers.

Objectives

To evaluate the efficacy, effectiveness, adverse events, and cost‐effectiveness of implanted spinal neuromodulation interventions for adults with chronic pain.

Methods

Criteria for considering studies for this review

Types of studies

We included randomised controlled trials (RCTs) comparing implanted spinal neuromodulation devices with placebo (sham) stimulation, no treatment or usual care; or comparing SNMDs + another treatment versus that treatment alone. We included RCTs of parallel, cross‐over, or cluster design, because RCTs are the best design to minimise bias when evaluating the effectiveness of an intervention.

We did not include quasi‐randomised studies or non‐randomised studies, due to the risk of bias inherent in such designs. We excluded non‐randomised studies, studies of experimental pain, case reports, and clinical observations.

Types of participants

We included participants ≥ 18 years old who were identified as having non‐cancer and non‐ischaemic pain of longer than three months duration. We excluded studies of people with cancer, or ischaemic‐related pain, or headache of any origin. We excluded studies in which average baseline (pre‐intervention) pain intensity levels in participants were less than 4/10 or 40/100. For studies in which only some participants met these inclusion criteria, we included these studies if data from participants who met the criteria were presented separately.

Types of interventions

We included studies that used any electrical spinal neuromodulation technique that involves the implanting of electrodes in the epidural space around the spinal cord (spinal cord stimulation (SCS)) or the dorsal root ganglion (dorsal root ganglion stimulation (DRGS)). We did not include interventions of peripheral nerve stimulation (of sites distal to the dorsal root) or transcutaneous stimulation procedures.

Studies must have compared these procedures with either placebo (sham) stimulation, usual care, no treatment, or other treatments, or compared stimulation plus other treatments or usual care versus the same treatment or usual care alone. We did not include studies that compared one form of spinal neuromodulation with another, or compared different stimulation regimens using the same type of spinal neuromodulation. We considered the effectiveness of SCS and DRGS separately, because they differ by procedure, their proposed distinct analgesic effects, and mechanisms.

The key comparisons of interests were:

active stimulation versus placebo stimulation;

active stimulation versus usual care or no treatment;

active stimulation plus another intervention versus that intervention alone.

Types of outcome measures

Primary outcomes

-

Pain intensity, measured using a visual analogue scale (VAS), numerical rating scale (NRS), verbal rating scale, or Likert scale. These must have been reported by the participant to be considered valid, and included. We presented and analysed primary outcomes as change on a continuous scale, or in a dichotomised format as the proportion of participants in each group who attained a predetermined threshold of improvement. For example, we judged cut‐points from which to interpret the likely clinical importance of (pooled) effect sizes according to criteria proposed in the IMMPACT consensus statement (Dworkin 2008). Specifically, we judged reductions in pain intensity compared with baseline as follows:

≥ 30%: moderately important change;

≥ 50%: substantially important change.

Adverse events (AEs; their nature, frequency, and the approach taken to record and classify them). Adverse events included, but were not limited to: electrode lead failure or displacement, infection, need for repeated implantation procedure(s). We treated them as separate outcomes, and included other AEs in an 'other' category.

Secondary outcomes

Disability, measured by validated, self‐report questionnaires or scales, or functional testing protocols

Analgesic medication use

Health‐related quality of life, using any validated tool

Health economic outcomes, including quality‐adjusted life‐years (QALYs), costs, health resource utilisation, and incremental cost‐effectiveness ratios (ICERS)

The planned follow‐up time‐points were:

during use: for trials that report during stimulation outcomes (most likely during the initial trial period of stimulation), we used the outcome reported closest to, but before the end of that period;

short‐term: we used outcomes reported within the first month post permanent implantation. When multiple time points were reported in this timeframe, we took the closest to the implantation date;

medium‐term: we used outcomes reported between four and eight months following permanent implantation. When multiple time points were reported in this timeframe, we took the latest date;

long‐term: we used outcomes reported at one year or longer post‐implantation. When multiple time points were reported in this timeframe, we took the latest date.

The distinction between "during use" and other time‐points was not possible to make and proved artificial in the context of the included studies, as outcomes were evaluated whilst stimulation was active at all time points. As a result, we restricted our analyses to short‐term, medium‐term and long‐term follow‐up. For cross‐over studies, follow‐up was measured from the point of the onset of stimulation.

Search methods for identification of studies

Electronic searches

We searched the following electronic databases from their inception, using a combination of controlled vocabulary, i.e. medical subject headings (MeSH), and free‐text terms to identify published articles:

Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL) in the Cochrane Library ‐Issue 10 of 12 2020;

MEDLINE (Ovid) ‐1946 to21 Oct 2020;

Embase (Ovid) ‐ 1980 to 2020 week 42;

Web of Science (ISI) SCI‐EXPANDED, SSCI, CPCI‐S, CPCI‐SSH ‐1970 to 21‐10‐20;

International HTA Database (https://database.inhata.org) searched on 2/11/20;

US National Institutes of Health Ongoing Trials Register ClinicalTrials.gov (www.clinicaltrials.gov);

World Health Organization International Clinical Trials Registry Platform (apps.who.int/trialsearch).

There were no language restrictions. All database searches were based on this strategy, but adapted to individual databases as necessary. We used medical subject headings (MeSH) or equivalent and text word terms. The search strategies can be found in Appendix 1; Appendix 2; Appendix 3.

Searching other resources

In addition, we checked reference lists of reviews and retrieved articles for additional studies. We contacted experts in the field for unpublished and ongoing trials. We contacted study authors for additional information when necessary.

Data collection and analysis

Selection of studies

Two review authors (NOC and WG) independently assessed the titles and abstracts of potential trials identified by the search strategy for their eligibility. We obtained the full text of studies we considered may be eligible, or if the eligibility of a study was unclear from the title and abstract. We excluded studies that did not match the inclusion criteria (see Criteria for considering studies for this review). We resolved disagreements between review authors regarding a study's inclusion by discussion. If we could not reach agreement, we planned that a third review author would assess relevant studies, and a majority decision was made. This was not found to be necessary. We did not anonymise studies prior to assessment. We included a PRISMA study flow diagram to document the screening process (Moher 2009).

Data extraction and management

Two review authors (from NOC, MF, WG) independently extracted data from each included study using a standardised and piloted data extraction form. They resolved discrepancies and disagreements by consensus. In cases where consensus could not be achieved, we planned that a third review author assessed the trial for arbitration, and a majority decision was made. This was not found to be necessary. We extracted the following data from each study included in the review:

country of origin;

study design;

study population (including diagnosis, diagnostic criteria used, symptom duration, age range, gender split, number, details of and reasons for participants excluded during the pre‐randomisation period, if used);

concomitant treatments that may affect outcome: (medication, procedures, etc);

sample size: active and control or comparator groups; loss to follow‐up, including number of people, characteristics, and reasons for withdrawal;

intervention(s) (including type of spinal neuromodulation, device type and manufacturer, details of implantation methods and sites, including details of initial trial period (if any), stimulation parameters, e.g. frequency, intensity, duration, electrode type and position, clinical setting);

type of placebo or comparator intervention;

outcomes (primary and secondary) and time points assessed (only for the comparisons of interest to this review);

declared industry sponsorship, study funding, author conflict of interest statements.

We collated multiple reports of the same study, so that each study rather than each report was the unit of interest in the review. We collected characteristics of the included studies in sufficient detail to populate a table of 'Characteristics of included studies'.

Assessment of risk of bias in included studies

Two review authors (NOC and MF) independently assessed risk of bias for each study using the Cochrane risk of bias 2 (RoB 2) tool, using the criteria outlined in Chapter 8 of the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions, with any disagreements resolved by discussion (Higgins 2020). In cases where consensus could not be achieved, we planned that a third review author would assess the trial for arbitration, and a majority decision made. This was not found to be necessary.

We used the RoB 2 tool (Sterne 2019) to assess the risk of bias around the effect of assignment to the interventions (the intention‐to‐treat effect) for the following results, for DRGS and SCS separately.

Comparisons

Active stimulation versus placebo stimulation

Active stimulation versus usual care or no treatment

Active stimulation plus another intervention vs that intervention alone

Outcomes

Pain intensity (continuous measures)

Pain intensity (dichotomous measures)

Adverse effects

Time points

For pain

Short term

Mid term

Long term

For adverse events

Short term

Medium term

Long term

The RoB 2 tool assesses the risk of bias in individual studies across the following domains:

bias arising from the randomisation process;

bias due to deviations from intended interventions;

bias due to missing outcome data;

bias in the measurement of the outcome; and

bias in the selection of the reported results.

For each domain, we followed the series of signalling questions outlined in the Handbook, and assigned a judgement of low risk of bias, some concerns, or high risk of bias. We planned to use interim guidance from the Cochrane Methods Support Unit to assess risk of bias for cluster‐RCTs but did not find any cluster trials. Since we planned to only take data from the first phase of cross‐over studies (see Unit of analysis issues), we planned to assess them as though they were of parallel design. However, as first phase data were not available for any cross‐over studies we took the decision to analyse them as presented and used the ROB2 tool for cross‐over studies to assess this risk of bias. (https://www.riskofbias.info/welcome/rob-2-0-tool/current-version-of-rob-2). This tool adds a supplementary domain "Risk of bias arising from period and carryover effects" with its own set of signalling questions.

When studies used a sham stimulation control as the comparator, as part of the RoB 2 domain 'bias due to deviations from intended interventions', we assessed the credibility of the sham condition, in terms of the likelihood that it was indistinguishable from the active stimulation condition and successfully blinded participants to the treatment condition. We rated the credibility of the sham used in sham‐ or placebo‐controlled studies as follows.

Optimal: high frequency or burst (sub‐perceptual) stimulation is delivered, which would not be expected to induce sensation, and sham stimulation involves implantation of electrodes and the use of a stimulator device that is identical, and appears to be active, but does not induce stimulation. Formal evaluation should indicate that blinding was likely to have been successful.

Suboptimal: stimulation occurs at a frequency that elicits sensation (e.g. paraesthesia), or is compared to a sham condition that is materially distinguishable from the active stimulation condition, or both. Stimulation for which aspects of the intervention other than sensations might compromise blinding, for example, if battery recharging requirements differ substantially between conditions, or sham stimulation for which a formal assessment or explicit report suggests that blinding was likely unsuccessful.

We used these judgements to inform the judgements made on participant blinding. When we made a judgement of suboptimal, we subsequently made a judgement of yes or probably yes for the signalling question 2.1. Were participants aware of their assigned intervention during the trial?

When evaluating the signalling question 2.2. Were carers and people delivering the interventions aware of participants' assigned intervention during the trial?, we considered whether the clinicians implanting the electrodes, involved in the perioperative process, or both, and follow‐up care of the participants were blind to the programmed stimulation parameters.

We reached overall judgements of risk of bias as outlined in Chapter 8 of the Handbook (Higgins 2020):

low risk of bias: the trial is judged to be at low risk of bias for all domains;

some concerns: the trial is judged to raise some concerns for at least one domain, but not to be at high risk of bias for any domain;

high risk of bias: the trial is judged to be at high risk of bias for at least one domain, or the trial is judged to have some concerns for multiple domains, in a way that substantially lowers confidence in the results.

We used the 'RoB Excel' tool and word templates (available at riskofbias.info) to record and manage RoB 2 assessments and processes, and we made available the full data related to this process on Figshare (DOI: 10.17633/rd.brunel.14838678).

Measures of treatment effect

When data were available, we presented outcomes in a dichotomised format. For dichotomised data (responder analyses), we considered analyses based on a 30% or greater reduction in pain intensity to represent a moderately important benefit, and a 50% or greater reduction in pain intensity to represent a substantially important benefit, as suggested by the IMMPACT guidelines (Dworkin 2008). When possible, we calculated risk ratio (RR) and risk difference (RD) with 95% confidence intervals (CIs) for dichotomised outcome measures. For device/procedure‐related adverse events, we prioritised the risk difference as there were zero events in the control arm. We calculated the number needed to treat for an additional beneficial outcome (NNTB) or the number needed to treat for an additional harmful outcome (NNTH) as an absolute measure of treatment effect.

We planned to express the size of the treatment effect for pain intensity, measured with a Visual Analogue Scale (VAS) or = Numerical Rating Scale (NRS), using the mean difference (MD) when all studies utilised the same measurement scale. As all studies measured pain intensity on a 0 to 10 or 0 to 100 VAS or NRS, we normalised all scales to a 0 to 100 scale and expressed the effect size as the mean difference to aid interpretability. We planned to use the standardised mean difference (SMD) when studies used substantially different scales. When we pooled data from different scales for which the direction of interpretation varies, we normalised the direction of the scales to a common direction.

The OMERACT 12 group has developed recommendations for establishing the minimal clinically important difference for pain outcomes (Busse 2015). They recommend 10 mm on a 0 to 100 mm VAS as the threshold for minimal clinical importance for the mean between‐group difference. They advise this should be interpreted with caution, as it remains possible that estimates that fall just below this point may still reflect a treatment that benefits an appreciable number of people. We used this threshold, but interpret it in light of the certainty of the included evidence.

Unit of analysis issues

For studies with more than two eligible comparisons in a single meta‐analysis, we divided the number of participants in each arm by the number of comparisons included from that study to avoid double‐counting. For cluster‐RCTs, we planned to seek direct estimates of the effect from an analysis that accounted for the cluster design. When the analysis in a cluster trial did not account for the cluster design, we planned to use the approximately correct analysis approach, presented in the Handbook (Higgins 2020). For cross‐over studies, we planned to only include data from the first phase of the study, when they were available. This is because it is theorised that spinal cord stimulation may elicit lasting effects beyond the period of stimulation, raising a high risk of carry‐over effects (Duarte 2020). As first‐phase, or phase‐by‐phase data were not available for any of the included cross‐over studies we took the decision to analyse these studies as presented. As we did not have access to individual patient data from any of these studies, we were unable to adjust for the paired nature of the data from these trials as recommended in the Cochrane Handbook (Higgins 2021). As such, while point estimates in this analysis should be accurate representations of the data it is possible that these analyses may be conservative, in terms of overestimating imprecision.

Dealing with missing data

When there were insufficient data presented in the study report to enter into a meta‐analysis, we requested the missing data from the study authors. We preferentially calculated effect sizes derived from intention‐to‐treat analyses. We had planned to exclude studies rated at high risk of bias from the primary meta‐analyses, including those at risk of bias due to missing outcome data. However, all included studies were rated at high risk of bias on one or more domain of the ROB2 tool.

Assessment of heterogeneity

We attempted to deal with clinical heterogeneity by combining studies that examined similar interventions. We did not combine studies that compared spinal neuromodulation techniques to usual care with studies that compared spinal neuromodulation techniques to sham within the same analysis. We assessed heterogeneity using the Chi² test to investigate the statistical significance of such heterogeneity, and the I² statistic to estimate the amount of heterogeneity. When significant heterogeneity (I² ≥ 50%, P < 0.10) was present, we explored subgroup analyses, described in the section Subgroup analysis and investigation of heterogeneity.

Assessment of reporting biases

We considered the possible influence of small‐study biases on review findings. When possible, for studies that reported dichotomised outcomes, we tested for the possible influence of publication bias on each outcome, by estimating the number of participants in studies with no effect required to change the NNTB to an unacceptably high level (defined as an NNTB of 10), as outlined in Moore 2008. When continuous outcomes were reported, we planned to use funnel plots to visually explore small‐study biases when there were at least 10 studies in a meta‐analysis, and the included studies differed substantially in size. However, no analysis contained this number of unique studies.

We identified the number of registered trials that have not been published or had results made available for this review, and report the number of participants that this represents. When results data were available in the trials registers, but there was no study report (published or made available by study authors upon request), we planned to exclude those data in the primary analyses, but conduct sensitivity analyses to evaluate how the inclusion of these data impacted our results and conclusions.

Data synthesis

We pooled the results of included studies using Review Manager 5 (Review Manager 2014). We planned to conduct separate meta‐analyses for SCS and DRGS interventions using a random‐effects model, as there are likely to be a number of sources of clinical heterogeneity between the included studies. However, we identified no studies of DRGS that met our inclusion criteria. We performed analyses at the following follow‐up points:

short term

medium term

long term

In the primary analysis, we pooled data from studies regardless of the specific diagnosis, stimulation site, or parameters. When inadequate data were found to support statistical pooling, we conducted narrative synthesis of the evidence, based upon the same key comparisons.

Subgroup analysis and investigation of heterogeneity

When there was significant heterogeneity (I² ≥ 50%, P < 0.10), we explored subgroup analyses by clinical population, stimulation site, and stimulation parameters.

We planned to explore the effect of clinical condition, using the following distinct subgroups:

neuropathic pain: studies that exclusively include participants with confirmed pain of neuropathic origin;

non‐neuropathic pain: studies that exclusively include participants with pain of non‐neuropathic origin (including conditions that are not clearly neuropathic in origin);

mixed populations: studies that include participants with both neuropathic and non‐neuropathic pain (including conditions that are not clearly neuropathic in origin).

We planned to explore the effect of stimulation parameters, using the following distinct subgroups:

conventional stimulation: the delivery of a tonic pulse, at a constant stimulation frequency between 40 Hz and 80 Hz, with a fixed pulse width;

high‐frequency stimulation: the delivery of a tonic pulse, at a frequency between 1 kHz and 10 kHz, with a fixed pulse width;

burst stimulation: the delivery of intermittent trains of stimulation.

To explore whether there is a difference in mean effects between subgroups, we used the test for subgroup differences (Deeks 2020). We were only able to do this for one comparison (Analysis 1.1) due to a lack of adequate data.

1.1. Analysis.

Comparison 1: SCS vs sham, Outcome 1: Pain Intensity: average post‐intervention. Short‐term follow up. Mean difference

Sensitivity analysis

When sufficient data were available, we planned to conduct the following sensitivity analyses.

Choice of meta‐analysis model: random‐effects models can produce inflated effect sizes in circumstances when many of the included studies are small. We explored this by repeating our analyses using a fixed‐effect model.

Risk of bias: based on the overall ROB 2 judgement for studies, we planned to explore the impact of risk of bias for the primary analyses, by repeating the analyses and excluding studies rated at high risk of bias. As all studies were rated at high risk of bias for one or more domains we were not able to conduct this analysis.

When results data are available in the trials registers, but there was no study report (published or made available by study authors upon request), we planned not include those data in the primary analyses, but to conduct sensitivity analyses to evaluate how the inclusion of these data impacts our results and conclusions. As we did not find any studies with data reported in the trial registry with no published study report we were unable to conduct this analysis.

Incorporating economic evidence

We developed a brief economic commentary based on current methods guidelines, to summarise the availability and principal findings of formal cost‐effectiveness analyses that were conducted as part of the identified RCTs (Shemilt 2019). This included reviewing the methods used, reporting data on costs per quality‐adjusted life‐year (QALY) for each treatment group, and reporting the incremental cost‐effectiveness ratio (ICER) for our comparisons of interest, when reported. We did not develop a new health economic model as part of this review.

Summary of findings and assessment of the certainty of the evidence

Two review authors (NOC, MF) independently used the GRADE system to rate the level of certainty of the evidence (Schünemann 2020).

The GRADE approach uses five considerations (limitations of studies, consistency of effect, imprecision, indirectness, and publication bias) to assess the certainty of the body of evidence for each outcome, and uses the following criteria to describe the confidence in the evidence:

high: we are very confident that the true effect lies close to that of the estimate of the effect;

moderate: we are moderately confident in the effect estimate; the true effect is likely to be close to the estimate of effect, but there is a possibility that it is substantially different;

low: our confidence in the effect estimate is limited; the true effect may be substantially different from the estimate of the effect;

very low: we have very little confidence in the effect estimate; the true effect is likely to be substantially different from the estimate of effect.

We decreased the grade rating by one (‐ 1), two (‐ 2), or three (‐ 3) levels, up to a maximum of ‐ 3, (or very low) for any criteria, based on the level of concern it raises.

Summary of findings table

We planned to include Summary of findings tables to present the findings for the following comparisons:

spinal cord stimulation versus placebo stimulation;

spinal cord stimulation versus usual care or no treatment;

dorsal root ganglion stimulation versus placebo stimulation;

dorsal root ganglion stimulation versus usual care or no treatment.

We included key information concerning the sum of available data on the following outcomes at short‐, medium‐and long‐term follow‐up, the magnitude of effect of the interventions examined, and the certainty of the evidence.

Pain intensity (continuous measures)

Pain intensity (dichotomous measures)

Adverse events

For continuous outcomes, we presented the mean difference; for dichotomous outcomes, we presented the risk ratio, risk difference, and the NNTB or NNTH (where the 95% confidence intervals did not include' no effect'), with 95% confidence intervals.

Results

Description of studies

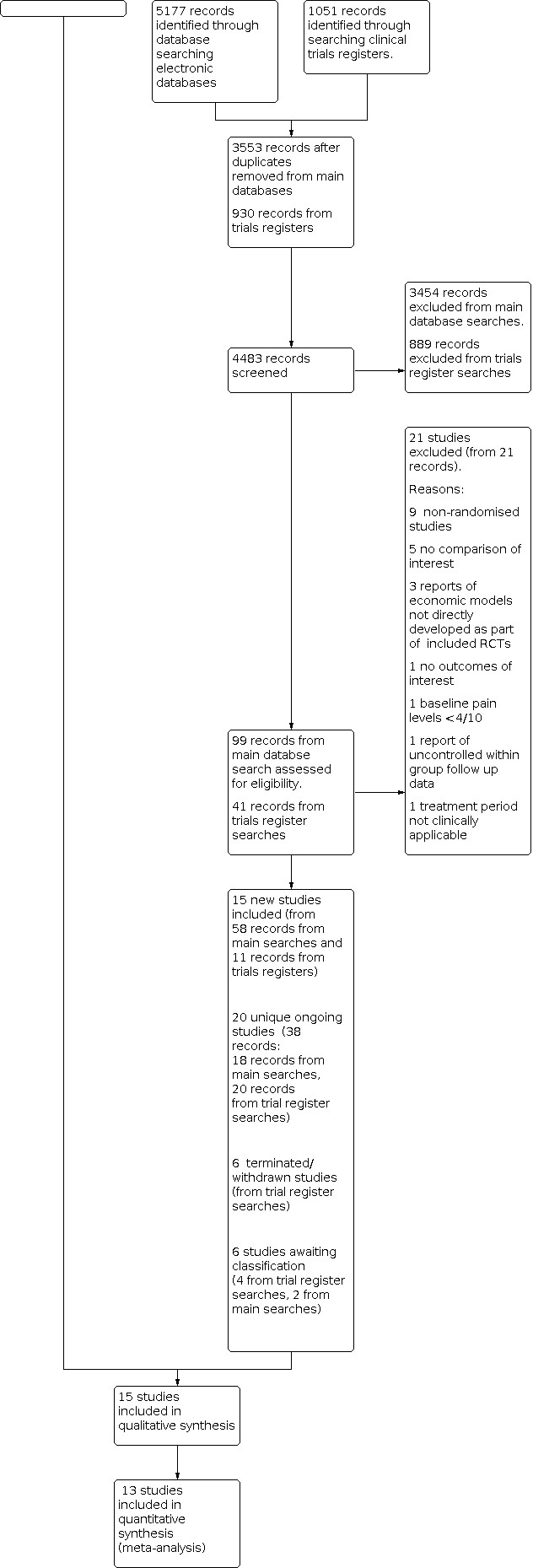

Results of the search

For a full description of our screening process, see the study flow diagram (Figure 1). For a summary of the search results for this review see Appendix 2 and Appendix 3.

1.

The main database searches were conducted in October 2020 and updated in September 2021 (see Electronic searches) and retrieved 3553 records after de‐duplication. We excluded 3454 of those at the title and abstract screening stage. After full‐text screening of the remaining 99 records we excluded 21 records of 21 studies (see Characteristics of excluded studies and Excluded studies for details). Two studies (Miller 2015; Miller 2016) were awaiting classification as were only available as conference abstracts. This left 58 records describing 15 unique studies and 18 records of ongoing studies.

We searched the trials registries in October 2020 and September 2021. Due to decreased functionality of the WHO registry related to the COVID pandemic we conducted a simplified search strategy of that registry. After deduplication our searches identified 930 records of which 889 were excluded on screening. This left 41 records, 11 of which were of published studies already identified and included, 20 were of ongoing studies, six were of studies identified as being terminated or withdrawn, and four studies were awaiting classification.

The final review includes 15 unique published studies that randomised 908 participants in total, and 20 unique ongoing studies.

Included studies

Country of origin and number of sites

Studies were conducted in the UK (Al‐Kaisy 2018; Eldabe 2021), Belgium (De Ridder 2013), the Netherlands (Kemler 2000; Kriek 2017; Slangen 2014; Tjepkema‐Cloostermans 2016), Germany (Schu 2014), Poland (Sokal 2020), Sweden (Lind 2015), and the USA (SENZA‐PDN). There were four international studies. de Vos 2014 was conducted in centres in the Netherlands, Denmark, Belgium and Germany, Perruchoud 2013 was conducted in Switzerland and the UK, PROCESS in Australia, Belgium, Canada, Italy, Israel, Spain and the UK and PROMISE in Belgium, Canada, Colombia, France, Germany, the Netherlands, Spain, the UK and the USA.

Six studies (Al‐Kaisy 2018; De Ridder 2013; Kemler 2000; Schu 2014; Sokal 2020; Tjepkema‐Cloostermans 2016) were conducted in a single centre. The number of centres in the remaining studies ranged from 2 (Eldabe 2021; Perruchoud 2013; Slangen 2014) to 28 (PROMISE).

Study funding and author declarations of interest

Of the 15 included trials 11 declared some form of industry funding (Al‐Kaisy 2018; de Vos 2014; Eldabe 2021; Kriek 2017; Lind 2015; Perruchoud 2013; PROCESS; PROMISE; Schu 2014; SENZA‐PDN; Slangen 2014). One study was funded by the Dutch Health Insurance council (Kemler 2000), one by the host hospital (Tjepkema‐Cloostermans 2016), one declared no external funding (Sokal 2020), and one provided no information (De Ridder 2013).

Ten studies (Al‐Kaisy 2018; de Vos 2014; Eldabe 2021; Kriek 2017; Perruchoud 2013; PROCESS; PROMISE; Schu 2014; SENZA‐PDN; Slangen 2014) reported one or more authors with relationships with industry involved in SNMD technology. These took the form of non‐financial support, research funding, consultancies, stock options, honoraria, speakers fees and travel grants. De Ridder 2013 declared that the first author had obtained a patent for burst stimulation, which was being evaluated in that study. Lind 2015 reported that authors had no financial interest to declare and Kemler 2000 and Tjepkema‐Cloostermans 2016 reported no information relating to author conflicts of interest.

Study designs

We included nine cross‐over studies (Al‐Kaisy 2018; De Ridder 2013; Eldabe 2021; Kriek 2017; Lind 2015; Perruchoud 2013; Schu 2014; Sokal 2020; Tjepkema‐Cloostermans 2016) with a total of 224 participants randomised. Study size ranged from 10 to 41 participants. Eight of these studies (Al‐Kaisy 2018; De Ridder 2013; Eldabe 2021; Kriek 2017; Perruchoud 2013; Schu 2014; Sokal 2020; Tjepkema‐Cloostermans 2016) compared various types of SCS (high‐frequency, burst, conventional stimulation) to a placebo stimulation condition and one study (Lind 2015) compared conventional stimulation with the stimulator switched off. Seven cross‐over studies (Al‐Kaisy 2018; De Ridder 2013; Lind 2015; Perruchoud 2013; Schu 2014; Sokal 2020; Tjepkema‐Cloostermans 2016) reported no washout period between stimulation conditions, while Kriek 2017 reported a two‐day washout period and Eldabe 2021 reported a nine‐day washout period.

We included six parallel studies (de Vos 2014; Kemler 2000; PROCESS; PROMISE; SENZA‐PDN; Slangen 2014) with a total of 684 participants randomised. Study size ranged from 36 to 218 participants. Of these, five studies compared conventional SCS in addition to other forms of management with the other management alone, and one study (SENZA‐PDN) compared high‐frequency SCS + conventional medical management with conventional medical management alone.

Participants

All studies included both male and female participants. Across all trials 50% of participants were female. Across studies that reported the range, the age of participants ranged from 25 to 74 years. In studies that reported the mean or median age of participants, the age ranged from 37 to 61 years.

Studies included participants with a range of painful conditions. Four studies (Al‐Kaisy 2018; PROCESS; PROMISE; Schu 2014) included participants with failed back surgery syndrome (FBSS), and one study included participants with chronic low back pain with or without leg pain (Eldabe 2021). Of these one study (PROCESS) mandated that leg pain was dominant over back pain in their inclusion criteria and two studies (Al‐Kaisy 2018, PROMISE) required participants' back pain intensity to be greater than their leg pain intensity. Three studies (de Vos 2014; SENZA‐PDN; Slangen 2014) included participants with painful diabetic neuropathy, and two studies (Kemler 2000; Kriek 2017) included participants with complex regional pain syndrome(CRPS) (though Kemler 2000 used the older diagnostic label "reflex sympathetic dystrophy"). Three studies included participants with various diagnoses. Of these De Ridder 2013 included participants with FBSS, failed neck surgery syndrome (FNSS), myelopathy and myelomalacia, Sokal 2020 included participants with CRPS and FBSS and Tjepkema‐Cloostermans 2016 included people with FBSS, peripheral neuropathy, diabetic neuropathic pain, multiple sclerosis (MS), and CRPS. One study (Lind 2015) included participants with irritable bowel syndrome.

Four studies included participants on the basis of a diagnosis of neuropathic pain. These included the three studies in painful diabetic neuropathy (de Vos 2014; SENZA‐PDN; Slangen 2014) and two studies in FBSS (PROCESS; Schu 2014) which specified that participants suffered from neuropathic pain of radicular origin. In the PROCESS study, the neuropathic nature was checked clinically by investigation of the pain distribution, examination of sensory, motor and reflex changes with supporting clinical tests such as electromyography (EMG). One study (Sokal 2020), included a mixed population of participants (CRPS, FBSS with predominant leg pain) with pain of neuropathic and non‐neuropathic origin, although did not describe how that distinction was made. One study in FBSS (PROMISE) reported that pain seemed to be neuropathic in nature in 84.4% of cases as indicated by the Neuropathic Pain questionnaire, Douleur Neuropathique 4 [DN4]. Two studies alluded to the neuropathic nature of the presenting pain in their reports but included conditions that are not necessarily neuropathic in nature such as CRPS, FBSS and FNSS (De Ridder 2013; Kriek 2017). These studies did not report any criteria or process for confirming a neuropathic mechanism. Three studies did not report or discuss the possible neuropathic nature of participants' pain (Al‐Kaisy 2018; Kemler 2000; Perruchoud 2013).

The majority of studies (Al‐Kaisy 2018; De Ridder 2013; de Vos 2014; Kemler 2000; Kriek 2017; Lind 2015; PROMISE; SENZA‐PDN; Slangen 2014; Sokal 2020) stated in their inclusion criteria that participant's pain must be refractory to previous treatments, though the details of those treatments varied. Al‐Kaisy 2018; de Vos 2014; Kemler 2000; PROCESS; PROMISE; SENZA‐PDN; Slangen 2014 all included a minimum level of pain at baseline of at least the equivalent of between 4/10 and 6/10 on a visual analogue scale (VAS) in their inclusion criteria. Four studies included people already implanted with, and receiving SCS at the point of recruitment (Eldabe 2021;nPerruchoud 2013; Schu 2014; Tjepkema‐Cloostermans 2016).

Across studies that reported baseline average pain levels for the pain that was the target of the intervention, these ranged from the equivalent of 4/10 to 8.2/10. Only three studies reported average baseline pain levels below 6/10 (Eldabe 2021; Perruchoud 2013; Schu 2014). In these studies, participants were implanted with a spinal cord stimulator and were receiving conventional stimulation prior to enrolment in the study. Of those studies that reported the average duration of participants' painful symptoms (Al‐Kaisy 2018; de Vos 2014; Kemler 2000; Kriek 2017; PROCESS; PROMISE; SENZA‐PDN; Slangen 2014; Sokal 2020) values ranged from 3 to 8.3 years, indicating longstanding pain.

Interventions and comparisons

All the included trials investigated SCS. We found no eligible completed trials of dorsal root ganglion stimulation(DRGs).

Of the cross‐over studies that compared different simulation parameters with placebo stimulation, five studies (De Ridder 2013; Kriek 2017; Lind 2015; Sokal 2020; Tjepkema‐Cloostermans 2016) compared conventional stimulation with sham, four studies (Al‐Kaisy 2018, Kriek 2017, Perruchoud 2013, Sokal 2020) included a high‐frequency (HF) condition, allowing for a comparison of HF versus sham. Four studies (De Ridder 2013; Eldabe 2021; Kriek 2017; Schu 2014; Tjepkema‐Cloostermans 2016) included a burst stimulation condition, allowing for a comparison of burst stimulation versus sham. Three studies (Eldabe 2021; Kriek 2017; Schu 2014) included a stimulation condition (500 Hz) that did not fit into either our predefined categories for conventional or HF stimulation. Data from that condition were not included in this review. In these studies, the intervention period (first phase) for each stimulation condition ranged from one to six weeks per condition. All of these studies provided outcome data for short‐term follow‐up only.

Of the five parallel studies that compared conventional SCS in addition to other forms of management with the other management alone, four studies compared the addition of SCS with medical management labelled as "conventional medical therapy" (de Vos 2014), "best medical treatment (BMT)" (Slangen 2014), "optimal medical treatment (OMT)" (PROMISE) and "conventional medical management (CMM)" (PROCESS; SENZA‐PDN) with medical management alone. In these studies, the duration of the spinal neuromodulation device (SNMD) intervention mirrored the maximum length of follow‐up, notwithstanding treatment discontinuations; as once implanted these interventions are intended to be used long term. The length of the follow‐up period in these studies ranged from six months to five years.

The details of medical management were reported as follows. In the study by de Vos 2014, medication adjustments and other conventional pain treatments, such as physical therapy, were allowed at any time if required. The PROMISE study reported that OMM was individualised for each patient and optimised at each visit and could include a range of treatments including acupuncture, psychological/behavioural therapies, physiotherapy as well as invasive treatments such as spinal injection, nerve blocks, epidural adhesiolysis and neurotomies. The PROCESS study similarly reported that CMM could include a range of physical, psychological and drug treatments but not spinal surgery or intrathecal drug delivery. Drug therapies included opioids, non‐steroidal anti‐inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs), antidepressants, anticonvulsants/antiepileptics and other analgesic therapies (not defined). SENZA‐PDN reported that CMM may include a variety of non‐invasive or minimally‐invasive treatments that comprise the standard of care for neuropathic limb pain, including, but are not limited to, pharmacological agents, physical therapy, cognitive therapy, chiropractic care, nerve blocks, and other non‐invasive or minimally invasive therapies. Slangen 2014 reported that BMT was based on international guidelines for the treatment of peripheral neuropathic pain but did not offer further detail. In the registry record for that study, the comparator was labelled "treatment as usual".

One study (Kemler 2000) compared SCS in addition to physical therapy versus physical therapy alone. Physical therapy was administered for 30 minutes twice weekly and lasted for six months and consisted of a standardised programme of graded exercises designed to improve strength, mobility and function of the affected hand or foot.

Study blinding

All of the parallel studies (de Vos 2014; Kemler 2000; PROCESS; PROMISE; SENZA‐PDN; Slangen 2014) evaluated open‐label comparisons of SCS + another therapy versus the other therapy alone. As such, neither participants nor clinicians/providers were blinded to the interventions allocated.

Eight of the cross‐over studies (Al‐Kaisy 2018; De Ridder 2013; Eldabe 2021; Kriek 2017; Lind 2015; Perruchoud 2013; Schu 2014; Sokal 2020) employed a sham control during which no stimulation was delivered from the stimulator. Tjepkema‐Cloostermans 2016 employed a low‐amplitude burst paradigm where standard stimulation with 0.1 mA bursts was used as this was expected to be subtherapeutic. This was labelled as a sham in the trial registry record, however, in the final published report was labelled as an active stimulation condition "low amplitude burst stimulation." In their discussion, Tjepkema‐Cloostermans 2016 stated that the difference in amplitude between low (0.1 mA for every participant) and high amplitude (individually adjusted) burst stimulation was less than expected and only minimal in some participants. For this reason, they considered that low amplitude burst was most likely not subtherapeutic in all participants and it is more appropriate to call this form of stimulation low amplitude burst stimulation instead of sham. We have included this study as the sham condition was intended as a sham a priori and an alternative explanation for the lack of contrast in stimulation amplitude may be a lack of efficacy.

For comparisons between conventional stimulation and sham (included by De Ridder 2013; Kriek 2017; Lind 2015; Sokal 2020), we rated blinding as suboptimal since conventional stimulation is associated with paraesthesia sensations and is thus distinguishable from sham. Perruchoud 2013 compared HF stimulation to sham, reported equivalent battery recharging requirements and a formal assessment of blinding was not indicative of problems and so blinding was rated as optimal for this study/comparison. For the comparisons of HF or Burst stimulation to sham, included by Al‐Kaisy 2018; De Ridder 2013; Eldabe 2021; Kriek 2017; Lind 2015; Schu 2014; Sokal 2020; Tjepkema‐Cloostermans 2016, we rated blinding as suboptimal. While these stimulation frequencies are generally sub‐perceptual, no formal evaluation of the success of blinding was reported.

Pre‐implantation trial periods

It is common clinical practice for participants to undergo a trial period of stimulation, in which electrodes are implanted and attached to an external stimulator. If a successful clinical response to trial stimulation is considered to have been established then participants usually proceed to full implantation of the final stimulator device. The timing and details of this trial period with regards to its relationship to the time of recruitment and randomisation varied across studies.

Three cross‐over studies (Al‐Kaisy 2018; Kriek 2017; Sokal 2020) included a trial period of conventional stimulation of between one and two weeks prior to full implantation which was completed after recruitment and prior to randomisation. Those considered to achieve a successful clinical response were subsequently implanted with a permanent stimulator. Four cross‐over studies (Eldabe 2021; Perruchoud 2013; Schu 2014; Tjepkema‐Cloostermans 2016) recruited participants who had been previously implanted were currently being treated with conventional SCS. One cross‐over study (De Ridder 2013) was conducted within the pre‐implantation trial period (that is, participants were randomised to different stimulation parameters during this period before the stimulation device had been permanently implanted), and one study did not report a pre‐implantation trial period (Lind 2015). As a result, it is important to note that in all cross‐over studies except De Ridder 2013 and Lind 2015, participants were pre‐selected on the basis of a positive response to a trial period of conventional stimulation.

All six parallel studies (de Vos 2014; Kemler 2000; PROCESS; PROMISE; SENZA‐PDN; Slangen 2014) included a pre‐implantation trial period in the SCS arm as part of the study intervention. In these studies the pre‐implantation trial period occurred after randomisation had occurred.

Pre‐implantation trial periods ranged from 5 to 28 days in those studies that reported the duration. Not all studies reported criteria for determining the success of these trial periods. Of those that did an average reduction on pain of ≥ 50% was commonly used (Al‐Kaisy 2018; Kemler 2000; Kriek 2017; PROCESS; SENZA‐PDN; Slangen 2014; Sokal 2020). One study (PROCESS) additionally required at least 80% overlap of participant's pain with stimulation‐induced paraesthesia, and one study (Slangen 2014) also considered a score of six or higher on the participant global impression of change (PGIC) scale for pain or sleep as a successful trial. One trial (PROMISE) required "adequate LBP relief with usual activity and appropriate analgesia in the context of post‐operative pain...as assessed by the investigator".

In the parallel design trials (de Vos 2014; Kemler 2000; PROCESS; PROMISE; SENZA‐PDN; Slangen 2014), the proportion of participants randomised to SCS who received trial stimulation ranged from 92% to 100% (median 100%). The proportion of participants who received trial stimulation and were judged to have had a successful trial ranged from 67% to 94% (median 85.5%). The proportion of participants who received a trial period of stimulation and who were subsequently permanently implanted ranged from 67% to 93% (median 83.5%). As a proportion of the total number of participants randomised to SCS between 67% and 93% were received a permanent SCS implant (median 80.7%).

Primary outcomes

None of the cross‐over studies reported data for pain for each phase of the cross‐over study. Therefore, separate first‐phase data were not available in the study reports. For all studies we contacted the authors to request some data that could not be found in the published reports. The authors of three studies (de Vos 2014; Kemler 2000; SENZA‐PDN) provided data upon request.

Pain intensity

All the included studies included pain intensity as an outcome. Pain intensity was measured using 0 to 10 or 0 to100 NRS or VAS in all studies. There was variation across studies in the reported anchors of the scales and in the level of detail provided regarding the precise question asked of participants. Five studies (de Vos 2014; PROCESS; PROMISE; SENZA‐PDN; Slangen 2014) reported the numbers of people who achieved ≥ 50% pain relief and presented responder analyses based on that outcome. Thirteen studies (Al‐Kaisy 2018; De Ridder 2013; de Vos 2014; Eldabe 2021; Kemler 2000; Kriek 2017; Perruchoud 2013; PROCESS; PROMISE; Schu 2014; SENZA‐PDN; Sokal 2020; Tjepkema‐Cloostermans 2016) reported the post‐intervention mean pain score, the average pain score over a period of two to five days at the end of an intervention period, or the average (mean) change from baseline in the pain score. One study (Lind 2015) did not report pain scores in a numeric form in their results.

Adverse events

Adverse events (AEs) were reported in 14 studies (Al‐Kaisy 2018; de Vos 2014; Eldabe 2021; Kemler 2000; Kriek 2017; Lind 2015; Perruchoud 2013; PROCESS; PROMISE; Schu 2014; SENZA‐PDN; Slangen 2014; Sokal 2020; Tjepkema‐Cloostermans 2016). While the level of detail regarding the methods used for monitoring and reporting adverse events varied, for most studies limited information on methods was reported. In five studies (Lind 2015; Perruchoud 2013; Slangen 2014; Sokal 2020; Tjepkema‐Cloostermans 2016), no methods were described for measuring, classifying or reporting AEs. In two studies (Schu 2014; Slangen 2014), only serious adverse events (SAEs)were reported, though the definition used for classifying SAEs was not described. For studies with medium‐ to long‐term follow‐up, AEs were generally reported for the full follow‐up period rather than at each follow‐up time point. In one study (De Ridder 2013), the report did not provide any details for measuring AEs and did not report any data on AEs. In one study (SENZA‐PDN), only SCS‐related adverse events were reported.

Secondary outcomes

Five studies (Kriek 2017; PROCESS; PROMISE; Schu 2014; Sokal 2020) reported measuring disability as an outcome. Of these, four studies used the Oswestry Disability Index (ODI) and one study in CRPS used the Disabilities of Arm Shoulder and Hand Questionnaire (DASH) when the upper extremity was affected, and the Walking Ability Questionnaire when the lower extremity was affected.

Eleven studies (de Vos 2014; Eldabe 2021; Lind 2015; Kemler 2000; Kriek 2017; Perruchoud 2013; PROCESS; PROMISE; SENZA‐PDN; Slangen 2014; Tjepkema‐Cloostermans 2016) reported measuring health‐related quality of life (HRQoL). The EuroQoL 5D (EQ‐5D) was used in eight studies (de Vos 2014; Eldabe 2021; Kemler 2000; Perruchoud 2013; PROCESS; PROMISE; SENZA‐PDN; Slangen 2014), theShort Form 36 (SF‐36) was used in four studies (Kriek 2017; PROCESS; PROMISE; Slangen 2014), and the Nottingham Health profile was also used in one study (Kemler 2000). Lind 2015 and Tjepkema‐Cloostermans 2016 used a 0‐10 VAS to measure HRQoL without reporting the anchors of the scale or the specific question. We did not consider this a valid form of measurement and did not include these data in any analyses. Tjepkema‐Cloostermans 2016 also measured the McGill Pain Questionnaire QoL scale.

Six studies (de Vos 2014; Kriek 2017; Perruchoud 2013; PROCESS; Slangen 2014; Sokal 2020) reported medication use as an outcome. Kriek 2017; PROCESS; Slangen 2014 and Sokal 2020 reported measuring all medication consumption in the trial period. de Vos 2014 used the Medication Quantification Scale III (MQS). Perruchoud 2013 did not report the methods used to measure this outcome. SENZA‐PDN reported measuring medication use in the published protocol but did not report these data.

Two studies (PROCESS; Slangen 2014) reported data on economic aspects of the intervention. The PROCESS study performed an economic evaluation with cost‐effectiveness analysis with long‐term modelling. Slangen 2014 performed an economic evaluation with a 12‐month time horizon. Kriek 2017 reported a cost analysis of SCS in the study protocol but these results were not reported in the published paper.

Ongoing studies

We have identified 20 unique ongoing studies that may be included in future updates of this review. In terms of our comparison "SCS versus placebo" these include eight more cross‐over studies (ACTRN12620000720910; Burst SCS; NCT03546738; NCT03733886; NCT04039633; NCT04894734; PANACEA; PET‐SCS) with a median N of 22 participants(range 10 to 60, total N 246), all of which compare Burst SCS with sham. There are also two parallel design studies, one of which is of high‐frequency SCS (MODULATE‐ LBP, N = 96) and the other is unclear (CITRIP N = 54).

For our comparison SCS + other intervention versus other intervention alone, we have identified six ongoing studies (ChiCTR‐IOR‐17012289; DISTINCT; ISRCTN10663814; NCT04676022; SCS‐PHYSIO; SENZA‐NSRBP) with a median N of 200 participants (range 30 to 300, total N 1100), three of which are of conventional SCS, two of high‐frequency SCS and one of Burst SCS. Three ongoing studies are investigating DRGs, one of which is a cross‐over study (DRKS00022557, N = 50) and two use a parallel design of which one (TSUNAMI DRG, N = 38) is testing high‐frequency DRGs and one (PENTAGONS, N = 56) is unclear. Nine out of 20 of these ongoing studies are reported as industry‐sponsored.

Excluded studies

We excluded 21 studies at the full‐text screening stage. Nine were not RCTs (Alo 2016; Dones 2008; Liem 2013; Marchand 1991; Rigoard 2013; Sagher 2008; Steinbach 2017; Tesfaye 1995; Winfree 2005), five did not include a comparison of interest to this review (Falowski 2019; Kufakwaro 2012; Liu 2020; Gilligan 2020; Liu 2021), three were reports of economic models that were not directly developed as part of the included RCTs (Annemans 2014; Kemler 2010; Taylor 2005), one presented no outcomes of interest (Kemler 2000), one was a report of uncontrolled within‐group follow‐up data (van Beek 2015), and one included participants with average baseline pain levels of < 4/10 on a 0 to 10 Numerical Rating Scale (NRS) (Wolter 2012). In one study (Meier 2015), the clinical stimulation periods were only 12 hours in duration and not considered clinically applicable.

Risk of bias in included studies

A summary of the risks of bias of studies included in each analysis can be found in forest plots of each outcome and in the risk of bias tables (Table 49; Table 50; Table 51; Table 52; Table 53; Table 54; Table 57; Table 55; Table 56; Table 58; Table 59; Table 60; Table 61). Risk of bias assessments for each outcome, including all domain judgements and support for judgements, are located in the risk of bias section (located after the Characteristics of included studies). Additional details on how we applied the Risk of Bias‐2 tool for each trial for each outcome can be found in the supplemental data file available in Figshare (DOI: 10.17633/rd.brunel.14838678).

Risk of bias for analysis 2.1 Pain intensity: average post‐intervention. Short‐term follow‐up. Mean Difference.

| Study | Bias | |||||||||||

| Randomisation process | Deviations from intended interventions | Missing outcome data | Measurement of the outcome | Selection of the reported results | Overall | |||||||

| Authors' judgement | Support for judgement | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement | |

| de Vos 2014 | Low risk of bias | Randomisation block stratified by centre. Allocation concealed. No apparent baseline imbalance. | Some concerns | Open‐label study without blinding of participants and personnel and no information provided to assess deviations in the medical management across groups. | Low risk of bias | Low levels of missing data and balanced between groups (7.5% SCS group, 10% CMM group). Authors shared complete dataset which indicates no meaningful bias. | High risk of bias | Open label study of a complex, invasive intervention with a subjective self‐reported outcome (Pain VAS). | Low risk of bias | While no protocol or full SAP is available sharing of the full dataset by the study authors indicates no evidence of selectivity. | High risk of bias | High risk of bias based on bias in the measurement of the outcome. |

| Kemler 2000 | Low risk of bias | Computer generated randomisation. Allocation concealed. Minor imbalance of gender (61%F in SCS group and 83%F in PT group) but compatible with chance. | Some concerns | Open label study without blinding of participants and personnel and no information provided to assess deviations in PT management across groups. | Low risk of bias | Only 1 participant in PT only group lost to follow up at this time‐point | High risk of bias | Open‐label study of a complex, invasive intervention with a subjective self‐reported outcome (Pain VAS). | Some concerns | No trial registry record, SAP or protocol available. | High risk of bias | High risk of bias based on bias in the measurement of the outcome. |

| SENZA‐PDN | Low risk of bias | Computer generated randomisation. Allocation concealed. No apparent baseline imbalance. | Some concerns | Open‐label study without blinding of participants and personnel and no information provided to assess deviations in the medical management across groups. An ITT approach is reported, though there are a number of post‐randomisation exclusions. | High risk of bias | Post randomisation exclusions took place prior to pre‐implantation trial period and were omitted from the analysis. In total at 1 month there are 16% of randomised participants excluded from the SCS group and 9% from the CMM group. It is possible that exclusions may be related to the value of the outcome. | High risk of bias | Open label study of a complex, invasive intervention with a subjective self‐reported outcome (Pain VAS). | Some concerns | While an SAP is available it is unclear whether it was finalised and unchanged ahead of the end of data collection. While authors shared data on request, they remained post‐randomisation exclusions and the N of participants analysed do not clearly match those in the CONSORT flow chart. | High risk of bias | High risk of bias on mutliple domains |

Risk of bias for analysis 2.2 Pain: participants with ≥50% pain relief. Short‐term follow‐up. Risk Ratio.

| Study | Bias | |||||||||||

| Randomisation process | Deviations from intended interventions | Missing outcome data | Measurement of the outcome | Selection of the reported results | Overall | |||||||

| Authors' judgement | Support for judgement | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement | |

| de Vos 2014 | Low risk of bias | Randomisation block stratified by centre. Allocation concealed. No apparent baseline imbalance. | Some concerns | Open label study without blinding of participants and personnel and no information provided to assess deviations in the medical management across groups. | Low risk of bias | Low levels of missing data (7.5% in SCS group and 0 in CMM group). Missing data treated as non‐responders. Authors shared complete dataset which indicates no meaningful bias. | High risk of bias | Open‐label study of a complex, invasive intervention with a subjective self‐reported outcome (Pain VAS). | Low risk of bias | While no protocol or full SAP is available sharing of the full dataset by the study authors indicates no evidence of selectivity. | High risk of bias | High risk of bias based on bias in the measurement of the outcome. |