Abstract

Background

Multiple sclerosis (MS) is a chronic, demyelinating disease of the central nervous system that results in progressive and irreversible disability. Fatigue is one of the most common MS-related symptoms and is characterized by a persistent lack of energy that impairs daily functioning. The burden of MS-related fatigue is complex and multidimensional, and to our knowledge, no systematic literature review has been conducted on this subject. The purpose of this study was to conduct a systematic literature review on the epidemiology and burden of fatigue in people with multiple sclerosis (pwMS).

Methods

Systematic searches were conducted in MEDLINE, Embase, and Evidence-Based Medicine Reviews to identify relevant studies of fatigue in pwMS. English-language records published from 2010 to January 2020 that met predefined eligibility criteria were included. We initially selected studies that reported quality of life (QoL) and economic outcomes according to categories of fatigue (e.g., fatigued vs non-fatigued). Studies assessing associations between economic outcomes and fatigue as a continuous measure were later included to supplement the available data.

Results

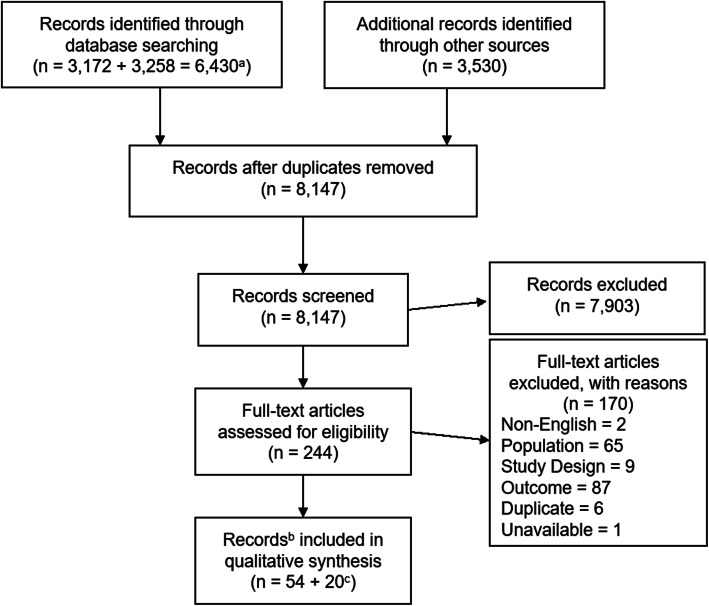

The search identified 8147 unique records, 54 of which met the inclusion criteria. Of these, 39 reported epidemiological outcomes, 11 reported QoL, and 9 reported economic outcomes. The supplementary screen for economic studies with fatigue as a continuous measure included an additional 20 records.

Fatigue prevalence in pwMS ranged from 36.5 to 78.0%. MS-related fatigue was consistently associated with significantly lower QoL. Results on the economic impact of fatigue were heterogeneous, but most studies reported a significant association between presence or severity of fatigue and employment status, capacity to work, and sick leave. There was a gap in evidence regarding the direct costs of MS-related fatigue and the burden experienced by caregivers of pwMS.

Conclusion

Fatigue is a prevalent symptom in pwMS and is associated with considerable QoL and economic burden. There are gaps in the evidence related to the direct costs of MS-related fatigue and the burden of fatigue on caregivers. Addressing fatigue over the clinical course of the disease may improve health and economic outcomes for patients with MS.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1186/s12883-021-02396-1.

Keywords: Multiple sclerosis, Fatigue, Burden of illness, Systematic review, Prevalence, Economic, Quality of life

Introduction

Multiple sclerosis (MS) is a chronic inflammatory disease that results in progressive demyelination in the central nervous system. Approximately 2.3 million people worldwide have been diagnosed with MS, with the highest prevalence in North America, Western Europe, and Australasia [1, 2]. The onset of MS usually occurs in early adulthood [2, 3], however, 3–5% of people with MS (pwMS) are diagnosed before this age [2, 4]. The clinical course of MS can be differentiated by disease history, progression of irreversible disability, and the presence or absence of acute disease relapses. Four courses of MS have been identified: clinically isolated syndrome (CIS), relapsing-remitting MS (RRMS), secondary progressive MS (SPMS), and primary progressive MS (PPMS). Approximately 85% of pwMS are initially diagnosed with RRMS, which may eventually progress to SPMS with or without superimposed relapses [5].

Fatigue, which can be defined as a “significant lack of physical and/or mental energy that is perceived by the individual or caretaker to interfere with usual or desired activity,” [6] is one of the most common and debilitating symptoms of MS. [2, 7–10] Several studies have been published describing the prevalence and impact of fatigue on QoL and employment [11–13]; however, to our knowledge, no systematic literature review (SLR) synthesizing the available evidence has been published. Therefore, the primary objective of the current report was to conduct an SLR synthesizing the published data on the prevalence, economic cost, and QoL burden of fatigue in pwMS.

Methods

An SLR was conducted to identify primary studies reporting epidemiological, economic, or QoL-related outcomes of MS-related fatigue in patients with CIS, RRMS, and/or SPMS, based on a predefined search strategy. The SLR adhered to the methodological and reporting guidelines outlined in the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analysis (PRISMA) checklist [14].

Search strategy

The search strategy was developed and performed by an experienced medical information specialist through an iterative process in consultation with the review team. Peer review was completed by a second information specialist using the Peer Review of Electronic Search Strategies (PRESS) Checklist [15]. Databases searched included Ovid MEDLINE®, including Epub Ahead of Print and In-Process & Other Non-Indexed Citations, Embase, and the following Evidence-Based Medicine Reviews (EBMR) databases: Health Technology Assessment, and the National Health Service (NHS) Economic Evaluation Database. All searches were performed on January 27, 2020.

The search incorporated controlled vocabulary (e.g., “Multiple Sclerosis”, “Incidence”, “Prevalence”, “Fatigue”) and keywords (e.g., “RRMS”, “occurrence”, “epidemiology”, “tired”, “cost”). Results were limited to the publication years 2000 to present and excluded conference abstracts published prior to 2018.

A comprehensive search of the grey literature was conducted using the Grey Matters checklist [16]. The following conference websites were also searched for relevant abstracts published within the past 2 years: American Academy of Neurology (AAN), American Neurology Association (ANA), Academy of Managed Care Pharmacy (AMCP), Americas Committee for Treatment and Research in Multiple Sclerosis (ACTRIMS), European Academy of Neurology (EAN), European Committee for Treatment and Research in Multiple Sclerosis (ECTRIMS), International Society for Pharmacoeconomics and Outcomes (ISPOR) America and Europe.

The reference lists of included articles were also reviewed, and records identified as potentially relevant were screened.

For additional details, please see Additional file 1.

Study eligibility criteria

The predefined inclusion and exclusion criteria pertaining to the population, intervention, comparator, outcome, and study design (PICOS) are presented in Table 1. Studies were included that evaluated at least 70% patients with RRMS, SPMS, or CIS, and that reported at least one outcome related to the epidemiological burden, humanistic burden, and/or economic burden of MS-related fatigue. Eligibility criteria were initially designed to select for studies reporting fatigue as a categorical measure (i.e., fatigued vs. non-fatigued patients, or low vs. high levels of fatigue) and its relationship with relevant outcomes. However, the eligibility criteria were revised to include studies reporting economic outcomes that evaluated fatigue as a continuous measure due to the sparse data available from the categorical studies in this area.

Table 1.

PICOS criteria for inclusion and exclusion of studies

| Inclusion Criteria | Exclusion Criteria |

|---|---|

| Population | |

| • People with MS and fatigue |

• Studies in which greater than 30% of subjects have MS types other than RRMS, SPMS, or CIS (e.g. PPMS, RIS) • Studies reporting fatigue as a continuous measure a |

| Intervention | |

| • Any or none | • N/A |

| Comparator | |

| • Any or none | • N/A |

| Outcomes | |

|

• Epidemiologic measures of MS-related fatigue (i.e., prevalence or incidence, current or projected) • Health resource utilization and costs (e.g., hospitalization, physician visits, drugs, assistive devices, long-term care) associated with MS-related fatigue • Lost productivity/income experienced by patients, caregivers, family members, society associated with MS-related fatigue • Community costs (e.g., personal support professionals, home care) associated with MS-related fatigue • Other costs (e.g., disability payments or other income support) associated with MS-related fatigue • Measures of patient-reported health-related quality of life (HRQoL) using a validated general health measure or disease-specific instrument |

• Studies that do not report methodology for assessing or identifying fatigue • Studies that do not report an outcome of interest in relation to MS-related fatigue, e.g., ° Only overall health costs for MS reported ° Only isolated dimensions of HRQoL or patient function (e.g. gait, cognitive impairment, anxiety/depression) reported |

| Study Design | |

| • Primary studies (e.g., surveys, epidemiological studies, natural history and disease progression studies, observational studies, registries or other real-world studies, BOI studies, clinical trials, economic evaluations) reporting one or more of the above outcomes | • Opinions, editorials, narrative reviews |

| Language | |

| • Articles in English b | • All non-English articles |

| Publication types and time frame | |

|

• 2010-present • All publication types (peer-reviewed articles, grey literature such as reports from government or other organizations, conference abstracts) • Conference abstracts from the past 2 years only |

• None |

aInitially, only studies reporting fatigue as a categorical measure (i.e., fatigued vs. non-fatigued patients, or levels of fatigue) were included. However, the eligibility criteria were later revised to include studies that evaluated fatigue as a continuous measure for outcomes related to economic burden, due to the sparse data identified in this area from categorical studies

bSearch was not restricted to English language studies, but non-English studies were excluded in study selection phase

Abbreviations: BOI burden of illness, CIS clinically isolated syndrome, FACIT Functional Assessment of Chronic Illness Therapy, FSS Fatigue Severity Scale, HRQoL health-related quality of life, MFIS Modified Fatigue Impact Scale, MS multiple sclerosis, N/A not applicable, PPMS primary progressive multiple sclerosis, RCT randomized controlled trial, RIS radiologically isolated syndrome, RRMS relapsing-remitting multiple sclerosis, SLR systematic literature review, SPMS secondary progressive multiple sclerosis, VAS visual analogue scale

Study selection

Study screening was performed using the systematic review software DistillerSR (Evidence Partners, Ontario, Canada). Screening was conducted by two reviewers who independently reviewed the citation titles and abstracts identified in the literature search to assess study eligibility based on the predefined PICOS criteria. Potentially relevant records were then screened by two reviewers in full-text form. Reasons for exclusion were documented at the full-text stage and are provided in Additional file 2. Any disagreements during study screening were resolved by discussion or by a third independent reviewer.

Data extraction

Details for selected articles were collected using a standardized data extraction template in Microsoft Excel. Data extraction was performed by a single reviewer and validated by a second reviewer. General study information (reference identification, first author last name, publication year, and country/region of study) was extracted, in addition to a predefined list of epidemiological, economic, and QoL outcomes.

Data synthesis

When multiple publications reporting data from the same study were identified, the most comprehensive data were used. When multiple analyses were conducted in a single study, the analysis with the most robust design was selected to be included in the synthesis, based on the following hierarchy: multivariate regression analyses; univariate regression analyses; correlation analyses; and statistical tests of association (e.g., t-test, χ2 test).

Results

Identification and description of studies

A total of 9960 records were identified through the database and grey literature searches. After de-duplication, 8147 records remained for title and abstract review. At the title and abstract stage, 244 full-text records were selected to be reviewed. Of these, 54 were found to fulfill the inclusion criteria. Results for each stage of the screening process are presented in Fig. 1. Of the included records, 40 (35 unique studies) examined epidemiological parameters (prevalence or incidence), nine investigated effects of fatigue on economic outcomes (costs, employment, etc.), and 11 investigated the effects of fatigue on QoL. Among these, one study reported data related to all three outcomes [11], two reported both epidemiology and QoL data [17, 18] and one reported both epidemiology and economic data [19]. An additional 20 records were identified through the supplementary screen for economic studies with fatigue as a continuous measure.

Fig. 1.

Search and exclusion process. a Searches were run separately for (1) epidemiology (n = 3172) and (2) economic/QoL studies (n = 3258). Each search was then deduplicated (epidemiology = 3081; economic/QoL = 3229). The two searches were then combined and deduplicated once again (n = 4631). b In some cases, more than one record was identified for a given study/population. c Supplemental search of economic studies with fatigue measured as a continuous parameter. Abbreviations: MA = meta-analysis; NMA = network meta-analysis; QoL = quality of life; SLR = systematic literature review

Epidemiology

Prevalence

The SLR search identified 39 publications reporting the prevalence of fatigue in pwMS, based on 35 unique datasets (Additional file 3). Twenty-five studies used self-reported measurements administered in different settings (online, at the clinic, etc.) [11, 18, 20–42]. Physicians and/or researchers administered the assessment in four studies [17, 19, 43, 44] and seven studies did not specify an administration method [45–51]. Most studies (n = 25 studies) were conducted in Europe, North America, and Australasia [18, 21–24, 26–33, 36–39, 42, 43, 45, 48–52] and an additional five records were linked to the same international study in which most of the participants reported living in North America, Australasia, and Europe [11, 25, 34, 35, 40]. The remaining five datasets were from South America, the Middle East, or the region was not reported [17, 19, 20, 46, 47]. Sample sizes ranged from 26 to 5475 participants.

Adult population

Twenty-seven studies reported results for adults with MS. Across these studies, the prevalence of fatigue ranged from 18.2 to 97.0% (Table 2). The wide range of values reported was likely due to the considerable heterogeneity across studies in the instruments or criteria used to classify patients as having fatigue.

Table 2.

Results – Epidemiology

| Author (year) | Tool to Measure Fatigue; Cut-off Value Used | Outcome(s) | n evaluated for fatigue | Fatigue (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Adult | ||||

| Alvarenga-Filho (2015) | MFIS; ≥ 38 | Prevalence | NR | 35.0 |

| Anens (2014) | FSS; ≥ 4 | Prevalence | 285 | 61.7 |

| Battaglia (2017) | VAS (0–10); NR | Prevalence | 997 | 96.0 |

| Calabrese (2017) | VAS (0–10); NR | Prevalence | 703 | 93.0 |

| Fiest (2016) | D-FIS; ≥ 5.0 | Prevalence, Incidence | 943 | 78.0 |

| Flachenecker (2017) | VAS (0–10); NR | Prevalence | 5233 | 96.0 |

| Fricska-Nagy (2016) | FIS; NR | Prevalence | 402 | 62.4 |

| Hadgkiss (2013) | FSS; ≥ 4 | Prevalence | 2143 | 65.7 |

| Havrdova (2017) | VAS (0–10); NR | Prevalence | 727 | 92.0 |

| Kratz (2016) | 11-point scale; Occurrence: > 0, Severe: > 6 | Prevalence | 180 | 88.0 |

| Labuz-Roszak (2012) | FSS; > 36 a | Prevalence | 122 | 61.5 |

| Larnaout (2018) b | FSS; > 4, MFIS; > 38 c | Prevalence | NR | 60.0 |

| Lebrun-Frenay (2017) | VAS (0–10); NR | Prevalence | 454 | 95.0 |

| Oreja-Guevara (2017) | VAS (0–10); NR | Prevalence | 446 | 92.0 |

| Pentek (2017) | VAS (0–10); NR | Prevalence | 508 | 94.0 |

| Pokryszko-Dragan (2016) | FSS; ≥ 4 | Prevalence | 44 | 18.2 |

| Reilly (2017) | FSS; ≥ 4 | Prevalence | 2079 | 65.6 |

| Rooney (2019) | FSS; ≥ 5 | Prevalence | 412 | 68.7 |

| Runia (2015) | FSS; ≥ 5 | Prevalence | 127 | 46.5 |

| Selmaj (2017) | VAS (0–10); NR | Prevalence | 408 | 97.0 |

| Thompson (2017) | VAS (0–10); NR | Prevalence | 769 | 96.0 |

| Uitdehaag (2017) | VAS (0–10); NR | Prevalence | 381 | 96.0 |

| van der Vuurst de Vries (2017) | FSS; ≥ 5 | Prevalence | NR | 35.3 |

| von Bismarck (2018) | FSMC; At least mild fatigue (> 42 Pt.) | Prevalence | 1069 | 36.5 |

| Weiland (2015) | FSS; ≥4 | Prevalence | 2138 | 65.6 |

| Weiland (2019) d | FSS; ≥ 4 | Prevalence, Longitudinal |

1268 1268 509 |

56.0 62.5 53.8 |

| Wood (2013) | FSS; ≥ 5 | Prevalence | 192 | 53.7 |

| Pediatric | ||||

| Florea (2019) | FSS; Moderate ≥3 | Prevalence | 23 | 43.0 |

| Goretti (2010) | FSS; ≥ 4 | Prevalence | 56 | 20.0 |

| Parrish (2013) | PedsQL Multidimensional Fatigue Scale; Total Fatigue ≥36 | Prevalence | 24 | 29.2 |

| van’s Gravesande (2019) b | PedsQL Multidimensional Fatigue Scale; Mildly impaired: score 1–2 SDs below healthy controls, severely impaired: score > 2 SDs below healthy controls | Prevalence | 106 | 40.6 |

| Mixed or unknown age | ||||

| Garcia (2019) a, b, e | FSS; Persistent fatigue ≥28, NFI-MS/BR; persistent fatigue ≥30 | Prevalence, Longitudinal; Mixed age |

38 26 |

FSS: 74.4, 54.0 NFI-MS/BR: 64.0, 47.0 |

| Kaya Aygunoglu (2015) | FSS; ≥4 | Prevalence | 120 | 70.0 |

| Razazian (2014) | FSS; ≥ 5 | Prevalence | 300 | 62.3 |

| Rupprecht (2018) b | MFIS; NR | Prevalence | NR | 45.0 |

aRefers to the total FSS score, not the average as is mostly calculated

bConference abstract

cUnclear if FSS or MFIS was used to report fatigue percentage

dBaseline data are presented in bold text and validation cohort in italics

eBaseline data are presented in bold text

Abbreviations: D-FIS daily FIS, FIS Fatigue Impact Scale, FSS Fatigue Severity Scale, MFIS modified FIS, FSMC Fatigue Scale for Motor and Cognitive Functions, NFIS-MS/BR Neurological Fatigue Index – multiple sclerosis, Brazilian Portuguese version, NR not reported, VAS visual analogue scale

Prevalence of Fatigue Reported by Different Scales:

Eleven studies did not use fatigue-specific validated instruments in estimating prevalence; ten studies used a 10-point visual analogue scale (VAS, cut-off not reported) and one study used an 11-point scale (fatigue presence defined as a score over 0) to measure fatigue. The prevalence of fatigue in these 11 studies ranged from 88.0 to 97.0% (Table 2). Validated fatigue scales (Table 3) were used in 16 studies (17 datasets) to define fatigue: seven studies used the Fatigue Severity Scale (FSS) ≥ 4, four used FSS ≥ 5, one used FSS > 36, two used the Modified Fatigue Impact Scale (MFIS) ≥ 38, one used the daily Fatigue Impact Scale (D-FIS) ≥ 5, one used the Fatigue Scale for Motor and Cognitive Functions (FSMC) > 42, and one used the Fatigue Impact Scale (FIS) with no cut-off reported. In these studies, the prevalence of fatigue ranged from 18.2 to 78.0%.

Table 3.

Characteristics of validated fatigue scales

| Validated fatigue scales | Domains/Components | Range of possible scores | Cut-offs for defining clinically relevant fatigue |

|---|---|---|---|

| Fatigue Severity Scale (FSS) | 9 items: activities of daily living, life participation, and sleep |

Total: 9–63 Mean of all scores: 1–7 |

Total: > 36 [53] |

| Fatigue Impact Scale (FIS) | 40 items: physical, cognitive, and social |

Total: 0–160 Physical: 0–40 Cognitive: 0–40 Social: 0–80 |

Cut-off not reported [9] |

| Modified Fatigue Impact Scale (MFIS) | 21 items (full-length) or 5 items (abbreviated): physical, cognitive, and psychosocial functioning |

21-item version: 0–84 (total) Physical: 0–36 Cognitive: 0–40 Psychosocial: 0–8 5-item version: 0–20 |

21-item (total): ≥ 38 [55] or ≥ 45 [56] a |

| Daily Fatigue Impact Scale (D-FIS) | 8 items: physical, cognitive, and psychosocial | Total: 0–32 | Cut-off not reported [57] |

| Fatigue Scale for Motor and Cognitive Functions (FSMC) | 20 items: Cognition and gait |

Total: 20-100 Cognitive: 10-50 Physical: 10-50 |

Total [58] Mild fatigue: > 42 Moderate fatigue: > 52 Severe fatigue: > 62 Cognitive Mild fatigue: > 21 Moderate fatigue: > 27 Severe fatigue: > 33 Physical Mild fatigue: > 21 Moderate fatigue: > 26 Severe fatigue: > 31 |

aCut-offs for components and 5-item version unknown

Higher values indicate greater fatigue

Prevalence of Fatigue in Relevant Subgroups:

Three studies exclusively included patients with CIS, in which fatigue was observed in 18.2 to 46.5% of participants [33, 36, 49]. Excluding the CIS-only studies, the prevalence of fatigue ranged from 35.0 to 97.0% based on both validated and non-validated instruments.

One study specifically examined fatigue in patients with no disability by restricting inclusion to those with Expanded Disability Status Scale [EDSS] scores between 0 and 1.5. Patients with EDSS scores in this range exhibit no or minimal neurological signs of MS. The prevalence of fatigue was estimated to be 35.0% in this sample [20].

The 12 studies that measured fatigue using a validated scale, did not restrict enrolment to CIS only, and did not restrict by level of disability may provide the most reliable and generalizable estimates of fatigue prevalence in the overall MS population. The prevalence of fatigue in these studies ranged from 36.5 to 78.0% [11, 18, 21, 25, 28, 34, 35, 40, 42, 47, 50, 51]. Eight of these studies (describing nine datasets) recruited 300 or more participants, the number required to estimate fatigue prevalence in pwMS with a standard error of ≤5%, assuming that fatigue prevalence was 60%; these studies reported prevalence estimates ranging from 36.5 to 78.0% [11, 25, 34, 35, 40, 42, 48, 50].

Longitudinal Data:

A single large international study (1401 participants) estimated the prevalence of fatigue at baseline (56.0%) and after 2.5 years (62.5%) using the FSS with fatigue defined as an FSS score ≥ 4 [40].

Pediatric and mixed-aged population

Four studies examined fatigue in a pediatric population, reporting a prevalence of 20.0 to 43.0% (Table 2).

Two additional studies included a mix of adult and pediatric patients [17, 19] and another two did not report age-related eligibility criteria [46, 48]. In these four studies, the prevalence of MS-related fatigue ranged from 45.5 to 74.4%.

One study recorded fatigue using the FSS as well as the Neurological Fatigue Index – multiple sclerosis, Brazilian Portuguese version (NFIS-MS/BR) at three time points with three-month intervals; fatigue was defined as FSS ≥28 or NFI-MS/BR ≥30. Of the 26 patients who attended the three interviews, 54.0% of the patients reported persistent fatigue at all three timepoints when measured with the FSS, and 47% with the NFIS-MS/BR [46].

Incidence

One Canadian study reported an incidence of fatigue per 100 of 28.9 (95% Confidence Interval [CI]: 23.4, 35.1) at year one after study enrolment, 29.9 (95% CI: 24.5, 35.9) at year two, and overall cumulative incidence of 38.8 (95% CI: 32.7, 45.3) [59].

Economic burden

A total of nine studies reported the economic burden associated with fatigue in pwMS, in which fatigue was reported categorically (Additional file 3) [11, 13, 19, 60–65]. Most studies were cross-sectional in design (n = 7). Sample sizes ranged from 90 to 5173. Most studies were conducted in Europe, North America, and Australasia (n = 6). Over half of the studies used the FSS to measure fatigue (n = 5) and the most commonly reported outcomes were related to employment (n = 7). All studies were of economic outcomes related to the impact of fatigue on the patient themselves; no records were identified pertaining to the societal or caregiver burden of MS-related fatigue. Two studies examined the relationship between fatigue and direct costs, such as drug costs and physician visits [60, 64]. Seven studies in adult populations reported indirect costs such as employment-related outcomes in relation to fatigue. Results for each study are available in Table 4.

Table 4.

Results – Economic burden (fatigue assessed as categorical)

| Author (year) | Type of Analysis | Sample Size (n) | Cut-off for Fatigue | Outcome | Predictor(s) | Value | 95% CI | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| da Silva (2016) | Multivariate ANOVA | 210 | MFIS Low impact (39–58), High impact (≥ 59) | Non-DMT costs | EDSS, gender, educational level, MFIS-BR (cut-off NR), MS relapse, any self-reported comorbidities, MS type, and occupation | NR | NR | 0.83 |

| Doesburg (2019) | Multiple logistic regression | 78 | NFI-MS Low (0–10 pts), Middle (11–20), High (21–30) | High work absence | Marital status, relapses in the past year, NFI-MS (middle vs low) | OR = 1.41 | 0.42, 4.76 | 0.581 |

| Marital status, relapses in the past year, NFI-MS (high vs low) | OR = 15.80 | 3.00, 83.26 | 0.001 | |||||

| Marital status, relapses in the past year, NFI-MS (high vs middle) | OR = 11.22 | 2.13, 59.16 | NR | |||||

| Grytten (2017) | Univariate logistic regression | 91 | FSS ≥ 4 | Unemployment at baseline | FSS ≥ 4 | OR = 3.03 | 1.19, 7.71 | 0.02 |

| Univariate Cox regression | 40 | Time to awarding disability pension | HR = 2.03 | 0.86, 4.78 | 0.09 | |||

| Koziarska (2018) | Multivariate logistic regression | 150 | FSS > 4 | Unemployment | FSS > 4, EDSS > 3, PQD5, KNS | OR = 2.63 | 1.02, 6.90 | 0.046 |

| Lorefice (2018) | Multivariate logistic regression | 123 | FSS > 4 | Unemployment status | Female, age, education, age at onset of MS, disease duration, EDSS, AES-S > 35, BDI-II > 14, FSS > 4 | OR = 2.10 | NR | 0.179 |

| McKay (2018) | Generalized estimating equations | 340 | D-FIS ≥ 5 | Hospitalizations | Age, sex, EDSS, D-FIS ≥ 5, comorbidity count, HUI pain | adjRR = 1.82 | 0.86, 3.87 | NR |

| Physician visit | Age, sex, D-FIS ≥ 5, smoker, comorbidity count, HUI pain, HUI cognition | adjRR = 1.06 | 0.97, 1.17 | NR | ||||

| Razazian (2014) | Pearson’s χ2 test | 300 | FSS ≥ 5 | Medication use | FSS ≥ 5 vs FSS < 5 | NR | NR | 0.002 |

| Employment status | FSS ≥ 5 vs FSS < 5 | NR | NR | 0.025 | ||||

| Salter (2017) | Multivariable logistic regression | 4607 | FPS Normal (0), Mild (1, 2), Moderate-to-severe (3–5) | Not working | MS clinical course, age, age at diagnosis, sex, number of comorbidity categories, CPS, FPS severe (vs. normal), HPS, PDDS | OR = 1.93 | 1.64, 2.26 | < 0.0001 |

| 1921 | Working < 35 h/week | OR = 1.63 | 1.04, 2.33 | 0.0031 | ||||

| 1788 | Cut back hrs. Past 6 mos. | OR = 7.19 | 3.29, 15.70 | < 0.0001 | ||||

| 1706 | Missed work days past 6 mos. | OR = 4.73 | 2.67, 8.37 | < 0.0001 | ||||

| 1717 | Receiving disability benefits | OR = 1.99 | 1.39, 2.84 | 0.0005 | ||||

| Weiland (2015) | Binary logistic regression | 2133 | FSS ≥ 4 | FSS ≥ 4 | Work part time | OR = 1.58 | 1.24, 2.02 | ≤ 0.001 |

| Stay at home parent/carer | OR = 19.4 | 1.36, 2.77 | ≤ 0.001 | |||||

| Unemployed | OR = 2.15 | 1.48, 3.11 | ≤ 0.001 | |||||

| Retired due to disability | OR = 5.54 | 4.11, 7.47 | ≤ 0.001 | |||||

| Retired due to age | OR = 1.59 | 0.94, 2.67 | NR | |||||

| Other (inc. student) | OR = 0.834 | 0.55,1.27 | NR |

Abbreviations: adjRR adjusted rate ratio, AES-S Apathy Evaluation Scale, ANOVA analysis of variance, BDI-II Beck Depression Inventory-Second Edition, CI confidence interval, CPS Cognition Performance Scale, D-FIS daily FIS, EDSS Expanded Disability Status Scale, FIS Fatigue Impact Scale, FPS Fatigue Performance Scale, FSS Fatigue Severity Scale, HPS Hand function Performance Scale, HR hazard ratio, hrs. hours, HUI Health Utility Index, KNS Hope for Success Questionnaire, MFIS modified FIS, MFIS-BR MFIS Brazilian Portuguese version, mos. months, NFIS-MS/BR Neurological Fatigue Index – Multiple Sclerosis, Brazilian Portuguese version, NR not reported, OR odds ratio, PDDS Patient Determined Disease Steps, PQD5 Perceived Deficits Questionnaire 5-items version, VAS visual analogue scale

Direct costs

Two studies reported the association between fatigue and direct costs. A longitudinal study conducted in Canada examined the association between baseline fatigue (D-FIS ≥ 5) and physician visit and hospitalization rates in pwMS. After adjusting for age, sex, comorbidity count, and other baseline characteristics, no significant associations were found between fatigue and physician visits (adjusted rate ratio = 1.06 [95% CI: 0.97, 1.17]) or hospitalizations (adjusted rate ratio = 1.82 [95% CI: 0.86, 3.87]) [64].

A cross-sectional cost analysis conducted in Brazil reported that higher non–disease-modifying therapy (DMT) direct costs were not associated (p = 0.83) with impact of fatigue (MFIS, Brazilian Portuguese version [MFIS-BR], cut-off not reported) after adjusting for disability, gender, educational level, MS relapse, self-reported comorbidities, MS type, and occupation [60].

Unemployment

Two European (Poland and Italy) and one North American (USA and Canada) cross-sectional studies assessed whether fatigue was predictive of unemployment in pwMS [62, 63, 65]. Both European studies reported that the odds of being unemployed were higher in pwMS experiencing fatigue (FSS > 4) than in non-fatigued patients after adjustment for patient characteristics such as sex, age, and disability status, although the relationship was only statistically significant in the Polish study (OR = 2.63, 95% CI: 1.02, 6.90 in the Polish study [62]; OR = 2.10, p = 0.179 in the Italian study [63]). The North American study also reported that fatigued participants (Fatigue Performance Scale [FPS] 3–5) had statistically significantly higher odds of not working (OR = 1.93; 95% CI: 1.64, 2.26) after adjustment for clinical course, age, and other patient characteristics [65].

One large international cross-sectional study reported that being unemployed was predictive of fatigue (FSS ≥ 4; OR = 2.15; 95% CI: 1.48, 3.11) [11]. Similarly, a Norwegian longitudinal study found fatigue (FSS ≥ 4) was predictive of unemployment at baseline (OR = 3.03 [95% CI: 1.19, 7.71]) [61]. Finally, an Iranian study found that employment status varied between fatigued and non-fatigued participants (p = 0.025) [19].

Other employment-related outcomes

A North American cross-sectional study found that fatigued participants (FPS 3–5) had statistically significantly higher odds of working less than 35 h per week (OR = 1.63; 95% CI: 1.04, 2.33), cutting back hours in the past 6 months (OR = 7.19; 95% CI: 3.29, 15.70), missing work days in the past 6 months (OR = 4.73; 95% CI: 2.67, 8.37), and receiving disability benefits (OR = 1.99; 95% CI: 1.39, 2.84), after adjustment for clinical course, age, age at diagnosis, sex, comorbidities, cognition, hand function, and disability [65].

A Dutch study found that high fatigue (NFI-MS 21–30) predicted high work absence when compared to low fatigue (NFI-MS 0–10; OR = 15.80; 95% CI: 3.00, 83.26) and intermediate fatigue (NFI-MS 11–20; OR = 11.22; 95% CI: 2.13, 59.16) after adjustment for marital status and relapses in the past year [13].

In contrast to the preceding studies, a Norwegian longitudinal study found fatigue (FSS ≥ 4) did not predict time to awarding disability pension (HR = 2.03; 95% CI: 0.86, 4.78) [61].

Supplemental studies

Due to the paucity of studies regarding key economic outcomes such as direct costs and caregiver burden, supplemental screening for studies assessing fatigue as a continuous measure was conducted; 20 additional studies were identified (see Additional file 4). Also included in these 20 are studies in which it was not clear whether fatigue was analyzed as a dichotomous or continuous variable. Most studies reported cross-sectional data (n = 17) [66–81]. Most studies were conducted in Europe and North America (n = 16) [66–68, 71–79, 81–84], one was conducted in Argentina [69], one in Australia [85], and two did not clearly report the study location [70, 80]. FSS and MFIS were the most commonly used tools to measure fatigue, used in seven studies each. Similar to the categorical studies, the supplemental screening returned a high proportion of studies examining employment-related outcomes (n = 18).

Two studies reported data on direct costs of fatigue. A cross-sectional study conducted in Germany found that drug costs and total costs, including indirect costs, drugs, hospital, rehabilitation, etc., were predicted by fatigue (MFIS) after adjusting for depression, disability status, and age [77]. In contrast, a Swedish study found no significant correlation between change in fatigue (FSMC) and change in sickness benefits after 1 year of natalizumab treatment [84].

Eighteen studies reported outcomes pertaining to general indirect costs such as employment/unemployment status and work capacity. One study found that indirect costs, unlike total and drug costs, were not predicted by fatigue [77]. Six studies found an association between fatigue and employment status [67, 69, 74, 80, 82, 86]; conversely, five studies failed to find a statistically significant association [66, 68, 76, 79, 83].

Regarding work capacity outcomes, higher fatigue was associated with sick leave [70] and productivity loss [72, 85] while work capacity was correlated with [73, 81] or impacted by [71, 73, 80, 87] fatigue among other symptoms.

Humanistic burden

Eleven studies reporting QoL/humanistic burden outcomes were identified through the systematic search (Additional file 3) [11, 12, 17, 18, 88–94]. Most studies were cross-sectional in design (n = 10) [11, 12, 17, 18, 89–94], and the sample sizes in all studies ranged from 31 to 2138. Geographically, studies were conducted in Europe (n = 6) [12, 17, 18, 88, 91, 92], Brazil (n = 3) [89, 93, 94] and Australia (n = 1) [90], with an additional international study where most of the participants reported living in North America, Australasia, and Europe [11]. QoL was assessed in six studies using MS-specific QoL assessment scales (Multiple Sclerosis Quality of Life-54 [MSQOL-54], Multiple Sclerosis International Quality of Life Questionnaire [MusiQoL], and the Functional Assessment of Multiple Sclerosis [FAMS]) [11, 12, 17, 18, 92, 94], while the 36-Item Short Form Survey (SF-36) was applied in four studies [88–91]. One study investigated the humanistic burden of MS-related fatigue by estimating utilities across fatigue levels [93]. Results for each study are available in Table 5.

Table 5.

Results – Humanistic burden

| Author (year) | Type of Analysis | Sample Size | Cut-off for Fatigue | Outcome | Predictor(s) | Value | 95% CI | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cioncoloni (2014) | Binary logistic regression | 57 | FSS ≥ 5 | PCS (SF-36) < 40 | FSS ≥ 5 | OR = 11.00 | 2.97, 40.78 | < 0.001 |

| MCS (SF-36) < 40 | OR = 8.64 | 2.39, 31.28 | 0.001 | |||||

| Filho (2019) a | Multiple linear regression | 31 | NR | Vitality (SF-36) | NR; included FSS (cut-off NR) | NR | NR | 0.006 |

| Physical Function (SF-36) | NR | NR | 0.001 | |||||

| Fricska-Nagy (2016) | Multiple linear regression | 428 | NR | Overall QoL (MSQOL-54) | BDI-I, EDSS, cognitive FIS (cut-off NR), physical FIS, social FIS | β = 0.094 | NR | 0.320 |

| BDI-I, EDSS, cognitive FIS, physical FIS (cut-off NR), social FIS | β = −0.785 | NR | 0.0001 | |||||

| BDI-I, EDSS, cognitive FIS, physical FIS, social FIS (cut-off NR) | β = − 0.152 | NR | 0.0001 | |||||

| Cognitive QoL (MSQOL-54) | BDI-I, EDSS, cognitive FIS (cut-off NR), physical FIS, social FIS | β = − 0.550 | NR | 0.0001 | ||||

| BDI-I, EDSS, cognitive FIS, physical FIS (cut-off NR), social FIS | β = −0.051 | NR | 0.475 | |||||

| BDI-I, EDSS, cognitive FIS, physical FIS, social FIS (cut-off NR) | β = −0.130 | NR | 0.097 | |||||

| Sexual QoL (MSQOL-54) | BDI-I, EDSS, cognitive FIS (cut-off NR), physical FIS, social FIS | β = −0.249 | NR | 0.001 | ||||

| BDI-I, EDSS, cognitive FIS, physical FIS (cut-off NR), social FIS | β = 0.008 | NR | 0.926 | |||||

| BDI-I, EDSS, cognitive FIS, physical FIS, social FIS (cut-off NR) | β = −0.185 | NR | 0.058 | |||||

| Goksel Karatepe (2011) | Hierarchical regression | 79 | FSS ≥ 4 | Physical health (MSQOL-54) | Disease course, education level, employment status, BDI, EDSS, FSS ≥ 4 | β = −1.641 | −2.99, −0.29 | 0.018 |

| Mental health (MSQOL-54) | β = −1.652 | −3.26, −0.04 | 0.045 | |||||

| Gullo (2019) | T-test | 62 | MFIS, Cognitive > 20, Physical > 23 | Physical summary (SF-36) | Cognitive fatigue (low vs. high; MFIS) | t = −0.31 | NA | 0.761 |

| Physical fatigue (low vs. high; MFIS) | t = 3.24 | NA | 0.002 | |||||

| Mental summary (SF-36) | Cognitive fatigue (low vs. high; MFIS) | t = 4.82 | NA | 0.001 | ||||

| Physical fatigue (low vs. high; MFIS) | t = 1.90 | NA | 0.063 | |||||

| Kaya Aygunoglu (2015) | Pearson’s correlation | 120 | FSS ≥ 4 | Physical and mental scores (MSQOL-54) | FSS | r = −0.58 | NA | < 0.01 |

| Leonavicius (2016) | Multiple linear regression | 137 | FSS ≥ 4 | FSS ≥ 4 | Gender, age, residence, education, marital status, professional activity, duration of RRMS, EDSS, DMT, sleep problems, HADS-D, HADS-A, MCS < 50 (SF-36), PCS < 50 (SF-36) | OR = 3.82 | 1.44, 5.54 | NR |

| Gender, age, residence, education, marital status, professional activity, duration of RRMS, EDSS, DMT, sleep problems, HADS-D, HADS-A, MCS < 50 (SF-36), PCS < 50 (SF-36) | NR | NR | > 0.05 | |||||

| Schmidt (2019) | Multivariate linear regression | 254 | FSMC ≥43 mild, ≥53 moderate, ≥63 severe | Overall QoL (MusiQoL) | Physical exercise, family status, occupation, CES-D, FSMC (cut-off NR) | β = 4.75 | 1.73, 7.78 | 0.002 |

| Family status, occupation, EDSS score, CES-D, FSMC (cut-off NR) | β = 3.46 | 0.51, 6.41 | 0.022 | |||||

| CES-D, FSMC, EDSS score (cut-off NR) | β = 4.98 | 2.10, 7.87 | 0.001 | |||||

| CES-D, FSMC, occupation, EDSS score (cut-off NR) | β = 4.17 | 1.29, 7.05 | 0.005 | |||||

| Takemoto (2015) | Wilcoxon test | 210 | MFIS-BR Absent: ≤38 points, Low: 39–58 points, High: ≥59 points | Utility score (Brazilian and UK algorithm) | MFIS-BR (absent vs. low vs. high) | NR | NA | < 0.001 |

| Taveira (2019) | T-test | 39 | MFIS ≥38 | FAMS | MFIS (fatigued vs non-fatigued) | NR | NA | 0.001 |

| Weiland (2015) b | Binary logistic regression | 2090 | FSS ≥ 4 | FSS ≥ 4 | Overall HRQoL domain (MSQOL-54) | OR = 0.94 | 0.93, 0.94 | < 0.001 |

| 1802 | Physical health composite (MSQOL-54) | OR = 0.91 | 0.90, 0.92 | < 0.001 | ||||

| 2131 | Energy domain (MSQOL-54) | OR = 0.92 | 0.92, 0.93 | < 0.001 | ||||

| 2047 | Mental health composite (MSQOL-54) | OR = 0.94 | 0.93, 0.94 | < 0.001 |

aConference abstract

bFor every increase of one point in overall MSQOL-54 the odds of clinically significant fatigue reduced by 0.06, 0.09, 0.08, 0.06, respectively

Abbreviations: BDI Beck Depression Inventory, BDI-I Beck Depression Inventory-First Edition, CES-D Center for Epidemiological Studies Depression Scale, CI confidence interval, DMT disease-modifying therapy, EDSS Expanded Disability Status Scale, FAMS Functional Assessment of Multiple Sclerosis quality of life scale, FIS Fatigue Impact Scale, FSMC Fatigue Scale for Motor and Cognitive functions, FSS Fatigue Severity Scale, HADS-A Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale – Anxiety, HADS-D Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale – Depression, HRQoL health-related quality of life, MCS mental component summary score of SF-36, MFIS Modified Fatigue Impact Scale, MFIS-BR MFIS, Brazilian Portuguese version, MSQOL-54 Multiple Sclerosis Quality of Life-54, MusiQoL Multiple Sclerosis International Quality of Life questionnaire, NR not reported, OR odds ratio, PCS physical component summary of SF-36, QoL quality of life, RRMS relapsing-remitting multiple sclerosis, SF-36 36-item Short Form health survey

Quality of life

Ten studies investigated the relationship between fatigue and QoL in pwMS [11, 12, 17, 18, 88–92, 94]. Four were European, two South American, two Middle Eastern, one Australian, and one international. The most commonly used scale to report fatigue was the FSS (n = 6), followed by the MFIS (n = 3), FIS (n = 1) and FSMC (n = 1). The SF-36 (n = 4) and the MSQOL-54 (n = 4) instruments were most often used to measure QoL.

The 36-item short form health survey

Four studies used the SF-36 to assess QoL in pwMS. All four studies found a significant association between fatigue and at least one of the subdomains of the SF-36 [88–91].

Two studies (one European and one Brazilian) examined the relationship between fatigue and the SF-36. After adjusting for demographic and socioeconomic variables, duration of RRMS, disease severity, DMT, sleep problems, depression, anxiety and the physical or mental component summary (PCS and MCS respectively) of the SF-36, the European study found higher odds of being fatigued (FSS > 4) with lower PCS scores (< 50) (OR = 3.82 [95% CI: 1.22, 5.54]), but not with lower MCS scores (< 50) (p > 0.05) [91]. The Brazilian study found that fatigue (FSS) was associated with a reduction in the physical functioning (p = 0.006) and vitality components (p = 0.001) of the SF-36 [89].

A second European study explored how fatigue (FSS ≥ 5) relates to physical and mental QoL [88]. This study demonstrated that fatigue was a significant predictor of poorer than average physical QoL (PCS < 40) (OR = 11.00 [95% CI: 2.94, 40.78]) and mental QoL (MCS < 40) (OR = 8.64 [95% CI: 2.39, 31.28]) [88].

An Australian study used the MFIS to measure cognitive (low ≤20, high > 20) and physical fatigue (low ≤23, high > 23) [90]. The study found that physical fatigue was significantly associated with the PCS (t = 3.24, p = 0.002) and cognitive fatigue was associated with the MCS (t = 4.82, p = 0.002). Cognitive fatigue was not associated with PCS (t = − 0.31, p = 0.761) and physical fatigue was not associated with MCS (t = 1.90, p = 0.063) [90].

Multiple sclerosis quality of Life-54

Four studies used the MSQOL-54 instrument to evaluate QoL [11, 12, 17, 18].

One study examined the relationship between physical, cognitive, and social fatigue measured using FIS with overall QoL, cognitive QoL, and sexual QoL. For each fatigue outcome, the study adjusted for depression, disease severity and the remaining two fatigue types [18]. Physical fatigue was significantly predictive of overall QoL (β = − 0.785, p = 0.0001) but not cognitive or sexual QoL.

Three studies used the FSS to measure fatigue. A large international study reported that for a one-point increase in any of the evaluated domains/composites of the MSQOL-54 (i.e., the overall QoL domain, the physical health composite, the energy domain, and the mental health composite), the odds of clinically significant fatigue (FSS ≥ 4) were reduced (OR = 0.94 [95% CI: 0.93, 0.94]; OR = 0.91 [95% CI: 0.90, 0.92]; OR = 0.92 [95% CI: 0.92, 0.93]; OR = 0.94 [95% CI: 0.93, 0.94], respectively) [11]. One study from Turkey, adjusting for disease course, education level, employment status, depression, and disease severity, found that fatigue (FSS ≥ 4) was predictive of physical and mental health based on the MSQOL-54 (β = − 1.641 [95% CI: − 2.99, − 0.29]; β = − 1.652 [95% CI: − 3.26, − 0.04], respectively) [12].

Finally, a second study conducted in Turkey found a strong negative correlation between fatigue (FSS ≥ 4) and the MSQOL-54 physical and mental scores (r = − 0.58, p < 0.01) [17].

Multiple sclerosis international quality of life

One German study measured QoL using the MusiQoL instrument and the FSMC (cut-off not reported) to measure fatigue [92]. Four analyses were performed with different predictors, and adjusted for different combinations of physical exercise, family status, occupations, depression and disease severity. All found fatigue to be predictive of overall QoL (β ranged from 3.46 to 4.98 and p values ranged from 0.001 to 0.022) [92].

Functional assessment of multiple sclerosis

One study conducted in Brazil used the FAMS instrument to measure QoL and the MFIS to evaluate fatigue [94]. FAMS score was significantly lower in patients who reported the presence of fatigue (p = 0.001, Student’s t-test) [94].

Utilities

One Brazilian study used the EQ-5D-3L to investigate the relationship between fatigue and utilities [93]. Fatigue was measured using the MFIS-BR. MS patients were categorized based on the MFIS-BR score into three groups; absent impact, low impact, and high impact of fatigue. The study reported significant differences between the utility scores between the three fatigue groups (p < 0.001), indicating a relationship between fatigue and utilities [93].

Discussion

A comprehensive SLR was conducted following pre-specified inclusion/exclusion criteria in order to understand the burden of MS-related fatigue through a descriptive summary of the published literature, and to identify gaps in current knowledge. Outcomes of interest included prevalence, economic burden, and humanistic burden of MS-related fatigue in patients of any age.

Across studies of adults with sample sizes of > 300 in which a validated fatigue-specific scale was used, and the population was not limited to CIS or non-disabled patients, the prevalence of fatigue ranged from 36.5 to 78.0%. In contrast, when considering all adult studies irrespective of type of MS, disability status, and tool used to estimate fatigue, prevalence ranged from 18.2 to 97.0%.

Nine studies reported data on the economic burden of fatigue in pwMS with fatigue analyzed as a categorical parameter. Of these, seven reported employment-related outcomes such as employment status and sick leave. Of these, all but one study found statistically significant associations between fatigue and the outcomes of interest. Two studies reported data on direct costs and resource utilization, respectively, and found no associations with fatigue.

In contrast, the evidence obtained from the 20 studies included through the supplemental screening for economic outcomes in which fatigue was assessed as a continuous parameter was more heterogeneous. Similar to the categorical studies, most of these records reported data on employment-related outcomes. Of the 11 studies analyzing the impact of fatigue on employment status (e.g. employed vs. unemployed), six found a statistically significant association between the presence of fatigue and unemployment, but no association was found in five other studies. Additionally, eight other studies reported data on the impact of fatigue on outcomes related to work capacity, all of which found a statistically significant association between fatigue and at least one work capacity outcome. One study found an association between fatigue and increased total and drug costs, but no association with indirect costs. Finally, one study found no correlation between fatigue improvement and reduction in sickness benefits.

Over half of the economic studies (including the original and supplementary studies) reported statistically significant associations between fatigue and the economic outcomes evaluated. Of the studies in which the results were not statistically significant, there was a trend for fatigue to be associated with negative impacts on employment-related outcomes.

Eleven studies reported humanistic outcomes, 10 of which were measures of QoL in fatigued and non-fatigued pwMS. A statistically significant association between fatigue and worsening QoL was observed in at least one of the QoL subdomains examined in each of these 10 studies. Only two studies found that physical fatigue was not associated with cognitive or sexual QoL [18, 90]. In the remaining study, statistically significantly lower utilities were observed in pwMS experiencing fatigue [93].

Numerous DMTs are available for the treatment of MS, however outcomes related to fatigue are not consistently reported in trials and it remains uncertain whether some treatments may be more beneficial for alleviating fatigue than others. Non-specific treatments such as amantadine and modafinil have demonstrated a statistically significant impact on fatigue, although the magnitude of benefit is modest at best, with a recent study showing that these treatments are not superior to placebo [95–99].

An important strength of this review is that it adheres to the PRISMA guidelines to ensure best practices for the conduct and reporting of systematic reviews were followed. In particular, a comprehensive literature search was performed and peer-reviewed by experienced information specialists, a detailed grey literature search was conducted, and study selection was performed according to pre-specified criteria. The limitations of this SLR are largely due to the numerous data gaps in the available literature regarding the burden of MS-related fatigue. Very few studies reported on the direct costs associated with fatigue in pwMS. Data were also somewhat sparse for indirect costs; although employment-related outcomes were available, the findings of these studies were not usually translated into monetary values. Therefore, few studies have quantified the indirect financial losses incurred by pwMS experiencing fatigue, their families, and society. The SLR also identified a paucity of longitudinal studies of the impact of fatigue throughout a patient’s life. Moreover, because of the heterogeneity in fatigue scales, methods, and outcome measures between studies, meaningful quantitative synthesis of results across studies was not feasible.

Conclusions

Clinically relevant fatigue affects a majority of pwMS. There is considerable evidence that the presence of fatigue is associated with poorer employment outcomes, however there was sparse and conflicting evidence as to whether fatigue is associated with greater healthcare costs. There was a lack of evidence regarding the burden of fatigue on caregivers of pwMS, or costs to society more broadly, therefore further study in these areas is required. MS-related fatigue appears to have a negative impact on QoL as measured by both generic HRQoL instruments and MS-specific instruments. It is expected that treatments alleviating fatigue may help mitigate the economic and humanistic burden of this prevalent manifestation of MS.

Supplementary Information

Additional file 1: Search strategies. Full epidemiology search strategy and full economic and quality of life search strategy.

Additional file 2: List of studies excluded from the SLR. Full references of excluded studies grouped by reason for exclusion

Additional file 3: Study and baseline characteristics of included studies. File includes three tables: 1) Study and baseline characteristics –Epidemiology; 2) Study and baseline characteristics – Economic burden (fatigue assessed as categorical); and 3) Study and baseline characteristics – Humanistic burden.

Additional file 4: Economic studies reporting fatigue as a linear variable. File includes two tables: 1) Baseline and study characteristics for economic studies reporting fatigue as a linear variable; and 2) Results of economic studies reporting fatigue as a linear variable.

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Abbreviations

- AAN

American Neurology Association

- ACTRIMS

Americas Committee for Treatment and Research in Multiple Sclerosis

- adjRR

Adjusted rate ratio

- AES-S

Apathy Evaluation Scale

- AMCP

Academy of Managed Care Pharmacy

- ANA

American Neurology Association

- ANOVA

Analysis of variance

- BDI

Beck Depression Inventory

- BDI-I

Beck Depression Inventory-First Edition

- BDI-II

Beck Depression Inventory-Second Edition

- BOI

Burden of illness

- CES-D

Center for Epidemiological Studies Depression Scale

- CI

Confidence interval

- CIS

Clinically isolated syndrome

- CPS

Cognition Performance Scale

- D-FIS

Daily Fatigue Impact Scale

- DMT

Disease-modifying therapy

- EAN

European Academy of Neurology

- EBMR

Evidence-Based Medicine Reviews

- ECTRIMS

European Committee for Treatment and Research in Multiple Sclerosis

- EDSS

Expanded Disability Status Scale

- EQ-5D

EuroQoL-5D

- FACIT

Functional Assessment of Chronic Illness Therapy

- FAMS

Functional Assessment of Multiple Sclerosis

- FIS

Fatigue Impact Scale

- FPS

Fatigue Performance Scale

- FSMC

Fatigue Scale for Motor and Cognitive functions

- FSS

Fatigue Severity Score

- HADS-A

Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale – Anxiety

- HADS-D

Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale – Depression

- HPS

Hand function Performance Scale

- HR

Hazard ratio

- HRQoL

Health-related quality of life

- HUI

Health Utility Index

- ISPOR

International Society for Pharmacoeconomics and Outcomes

- KNS

Hope for Success Questionnaire

- MCS

Mental component summary score of SF-36

- MFIS

Modified Fatigue Impact Scale

- MS

Multiple sclerosis

- MSQOL-54

Multiple Sclerosis Quality of Life-54

- MusiQoL

Multiple Sclerosis International Quality of Life questionnaire

- N/A

Not applicable

- NFIS-MS

Neurological Fatigue Index – Multiple Sclerosis

- NFIS-MS/BR

Neurological Fatigue Index – Multiple Sclerosis, Brazilian Portuguese version

- NHS

National Health Service

- NMA

Network meta-analysis

- NR

Not reported

- OR

Odds ratio

- PCS

Physical component summary of SF-36

- PDDS

Patient Determined Disease Steps

- PICOS

Population, intervention, comparator, outcome, and study design

- PPMS

Primary progressive MS

- PQD5

Perceived Deficits Questionnaire 5-items version

- PRESS

Peer Review of Electronic Search Strategies

- PRISMA

Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses

- pwMS

People with multiple sclerosis

- RCT

Randomized controlled trial

- RIS

Radiologically isolated syndrome

- RRMS

Relapsing-remitting multiple sclerosis;

- SF-36

36-item Short Form health survey

- SLR

Systematic literature review

- SPMS

Secondary progressive multiple sclerosis

- VAS

Visual analogue scale

Authors’ contributions

All authors made substantive intellectual contributions to this study to qualify as authors. All authors participated in study design through drafting or approval of the protocol. AOR, OK, EW, and LC contributed to the literature search. AOR, OK, EW, and LC worked on data collection. AOR, AK, OK, EW, LC, and SS analyzed and interpreted the data. AOR and OK wrote the manuscript draft. EW, AK, LC, and SS provided critical review and revisions. All authors reviewed and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Funding

Sponsorship for this study was provided by Janssen Research & Development, LLC. The funders had a role in study design and editorial assistance. The corresponding author had full access to all the data in the study and had final responsibility for the decision to submit for publication.

Availability of data and materials

The authors declare that the data supporting the findings of this study are available within the article and its supplementary information files. Data are also available from the corresponding author, AK, upon reasonable request.

Declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

AOR, OK, EW, LC, and SS have disclosed that they are employees of EVERSANA, which received consulting fees from Janssen Research & Development, LLC in connection with the development of this manuscript. AK is employed by Janssen Research & Development, LLC. AK has disclosed that he is also a shareholder of Janssen Research & Development, LLC.

Footnotes

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Wallin MT, Culpepper WJ, Nichols E, Bhutta ZA, Gebrehiwot TT, Hay SI, Khalil IA, Krohn KJ, Liang X, Naghavi M, Mokdad AH, Nixon MR, Reiner RC, Sartorius B, Smith M, Topor-Madry R, Werdecker A, Vos T, Feigin VL, Murray CJL. Global, regional, and national burden of multiple sclerosis 1990–2016: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2016. Lancet Neurol. 2019;18(3):269–285. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(18)30443-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.MS international federation. What is MS? [updated 2019-10-14. Available from: https://www.msif.org/about-ms/what-is-ms/.

- 3.Milo R, Kahana E. Multiple sclerosis: Geoepidemiology, genetics and the environment. Autoimmun Rev. 2010;9(5):A387–AA94. doi: 10.1016/j.autrev.2009.11.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chitnis T, Glanz B, Jaffin S, Healy B. Demographics of pediatric-onset multiple sclerosis in an MS center population from the northeastern United States. Mult Scler J. 2009;15(5):627–631. doi: 10.1177/1352458508101933. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.National Multiple Sclerosis Society. Types of MS [Available from: https://www.nationalmssociety.org/What-is-MS/Types-of-MS.

- 6.Multiple Sclerosis Clinical Practice Guidelines . Fatigue and multiple sclerosis: evidence-based management strategies for fatigue in multiple sclerosis. Washington D.C.: Paralyzed Veterans of America; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Freal JE, Kraft GH, Coryell JK. Symptomatic fatigue in multiple sclerosis. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 1984;65(3):135–138. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Krupp L. Mechanisms, measurement, and management of fatigue in multiple sclerosis. In: Thompson A, Polman C, Hohfeld R, editors. Multiple sclerosis: clinical challenges and controversies. London: Martin Dunitz; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Fisk JD, Pontefract A, Ritvo PG, Archibald CJ, Murray TJ. The impact of fatigue on patients with multiple sclerosis. Can J Neurol Sci. 1994;21(1):9–14. doi: 10.1017/S0317167100048691. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hadjimichael O, Vollmer T, Oleen-Burkey M. Fatigue characteristics in multiple sclerosis: the north American research committee on multiple sclerosis (NARCOMS) survey. Health Qual Life Outcomes. 2008;6(1):100. doi: 10.1186/1477-7525-6-100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Weiland TJ, Jelinek GA, Marck CH, Hadgkiss EJ, Meer DMvd, Pereira NG, et al. Clinically significant fatigue: prevalence and associated factors in an international sample of adults with multiple sclerosis recruited via the internet. PLoS One. 2015;10(2):e0115541. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0115541. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Goksel Karatepe A, Kaya T, Gunaydn R, Demirhan A, Ce P, Gedizlioglu M. Quality of life in patients with multiple sclerosis: the impact of depression, fatigue, and disability. Int J Rehabil Res. 2011;34(4):290–298. doi: 10.1097/MRR.0b013e32834ad479. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Doesburg D, Vennegoor A, Uitdehaag BMJ, van Oosten BW. High work absence around time of diagnosis of multiple sclerosis is associated with fatigue and relapse rate. Mult Scler Relat Disord. 2019;31:32–37. doi: 10.1016/j.msard.2019.03.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, Altman DG, The PG. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and Meta-analyses: The PRISMA statement. PLoS Med. 2009;6(7):e1000097. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1000097. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.McGowan J, Sampson M, Salzwedel DM, Cogo E, Foerster V, Lefebvre C. PRESS peer review of electronic search strategies: 2015 guideline statement. J Clin Epidemiol. 2016;75:40–46. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2016.01.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Canadian Agency for Drugs and Technologies in Health. Grey Matters: a practical tool for searching health-related grey literature [updated May 8, 2019.

- 17.Kaya Aygunoglu S, Celebi A, Vardar N, Gursoy E. Correlation of fatigue with depression, disability level and quality of life in patients with multiple sclerosis. Noro Psikiyatr Ars. 2015;52(3):247–251. doi: 10.5152/npa.2015.8714. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Fricska-Nagy Z, Fuvesi J, Rozsa C, Komoly S, Jakab G, Csepany T, et al. The effects of fatigue, depression and the level of disability on the health-related quality of life of glatiramer acetate-treated relapsing-remitting patients with multiple sclerosis in Hungary. Mult Scler Relat Disord. 2016;7:26–32. doi: 10.1016/j.msard.2016.02.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Razazian N, Shokrian N, Bostani A, Moradian N, Tahmasebi S. Study of fatigue frequency and its association with sociodemographic and clinical variables in patients with multiple sclerosis. Neurosciences (Riyadh) 2014;19(1):38–42. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Alvarenga-Filho H, Papais-Alvarenga RM, Carvalho SR, Clemente HN, Vasconcelos CC, Dias RM. Does fatigue occur in MS patients without disability? Int J Neurosci. 2015;125(2):107–115. doi: 10.3109/00207454.2014.909415. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Anens E, Emtner M, Zetterberg L, Hellstrom K. Physical activity in subjects with multiple sclerosis with focus on gender differences: a survey. BMC Neurol. 2014;14:47. doi: 10.1186/1471-2377-14-47. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Battaglia M, Kobelt G, Ponzio M, Berg J, Capsa D, Dalen J, et al. New insights into the burden and costs of multiple sclerosis in Europe: Results for Italy. Multiple Sclerosis (Houndmills, Basingstoke, England) 2017;23(2_suppl):104. doi: 10.1177/1352458517708176. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Calabrese P, Kobelt G, Berg J, Capsa D, Eriksson J. Sclerosis Platform European M. New insights into the burden and costs of multiple sclerosis in Europe: Results for Switzerland. Multiple Sclerosis (Houndmills, Basingstoke, England) 2017;23(2_suppl):192. doi: 10.1177/1352458517708685. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Flachenecker P, Kobelt G, Berg J, Capsa D, Gannedahl M. Sclerosis Platform European M. New insights into the burden and costs of multiple sclerosis in Europe: Results for Germany. Multiple Sclerosis (Houndmills, Basingstoke, England) 2017;23(2_suppl):78. doi: 10.1177/1352458517708141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hadgkiss EJ, Jelinek GA, Weiland TJ, Pereira NG, Marck CH, van der Meer DM. Methodology of an International Study of People with Multiple Sclerosis Recruited through Web 2.0 Platforms: Demographics, Lifestyle, and Disease Characteristics. Neurol Res Int. 2013;2013:580596. doi: 10.1155/2013/580596. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Havrdova E, Kobelt G, Berg J, Capsa D, Gannedahl M, Dolezal T, et al. New insights into the burden and costs of multiple sclerosis in Europe: Results of the Czech Republic. Multiple Sclerosis (Houndmills, Basingstoke, England) 2017;23(2_suppl):41. doi: 10.1177/1352458517708117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kratz AL, Ehde DM, Hanley MA, Jensen MP, Osborne TL, Kraft GH. Cross-sectional examination of the associations between symptoms, community integration, and mental health in multiple sclerosis. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2016;97(3):386–394. doi: 10.1016/j.apmr.2015.10.093. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Labuz-Roszak B, Kubicka-Baczyk K, Pierzchala K, Machowska-Majchrzak A, Skrzypek M. Fatigue and its association with sleep disorders, depressive symptoms and anxiety in patients with multiple sclerosis. NeurolNeurochir Pol. 2012;46(4):309–317. doi: 10.5114/ninp.2012.30261. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lebrun-Frenay C, Kobelt G, Berg J, Capsa D, Gannedahl M. Sclerosis Platform European M. New insights into the burden and costs of multiple sclerosis in Europe: Results for France. Multiple Sclerosis (Houndmills, Basingstoke, England) 2017;23(2_suppl):65. doi: 10.1177/1352458517708125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Oreja-Guevara C, Kobelt G, Berg J, Capsa D, Eriksson J. Sclerosis Platform European M. New insights into the burden and costs of multiple sclerosis in Europe: Results for Spain. Multiple Sclerosis (Houndmills, Basingstoke, England) 2017;23(2_suppl):166. doi: 10.1177/1352458517708672. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Parrish JB, Weinstock-Guttman B, Smerbeck A, Benedict RH, Yeh EA. Fatigue and depression in children with demyelinating disorders. J Child Neurol. 2013;28(6):713–718. doi: 10.1177/0883073812450750. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Pentek M, Kobelt G, Berg J, Capsa D, Dalen J, Biro Z, et al. New insights into the burden and costs of multiple sclerosis in Europe: Results for Hungary. Multiple Sclerosis (Houndmills, Basingstoke, England) 2017;23(2_suppl):91. doi: 10.1177/1352458517708142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Pokryszko-Dragan A, Dziadkowiak E, Zagrajek M, Slotwinski K, Gruszka E, Bilinska M, Podemski R. Cognitive performance, fatigue and event-related potentials in patients with clinically isolated syndrome. Clin Neurol Neurosurg. 2016;149:68–74. doi: 10.1016/j.clineuro.2016.07.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Reilly GD, Mahkawnghta AS, Jelinek PL, Livera AMD, Weiland TJ, Brown CR, et al. International Differences in Multiple Sclerosis Health Outcomes and Associated Factors in a Cross-sectional Survey. Front Neurol. 2017;8:229. doi: 10.3389/fneur.2017.00229. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Rooney S, Wood L, Moffat F, Paul L. Prevalence of fatigue and its association with clinical features in progressive and non-progressive forms of multiple sclerosis. Multiple Sclerosis Related Disord. 2019;28:276–282. doi: 10.1016/j.msard.2019.01.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Runia TF, Jafari N, Siepman DA, Hintzen RQ. Fatigue at time of CIS is an independent predictor of a subsequent diagnosis of multiple sclerosis. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2015;86(5):543–546. doi: 10.1136/jnnp-2014-308374. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Selmaj K, Kobelt G, Berg J, Orlewska E, Capsa D, Dalen J, et al. New insights into the burden and costs of multiple sclerosis in Europe: Results for Poland. Multiple Sclerosis (Houndmills, Basingstoke, England) 2017;23(2_suppl):130. doi: 10.1177/1352458517708666. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Thompson A, Kobelt G, Berg J, Capsa D, Eriksson J, Miller D, et al. New insights into the burden and costs of multiple sclerosis in Europe: Results for the United Kingdom. Multiple Sclerosis (Houndmills, Basingstoke, England) 2017;23(2_suppl):204. doi: 10.1177/1352458517708687. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Uitdehaag B, Kobelt G, Berg J, Capsa D, Dalen J. Sclerosis Platform European M. New insights into the burden and costs of multiple sclerosis in Europe: Results for the Netherlands. Multiple Sclerosis (Houndmills, Basingstoke, England) 2017;23(2_suppl):117. doi: 10.1177/1352458517708663. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Weiland TJ, Livera AMD, Brown CR, Jelinek GA, Aitken Z, Simpson SL, et al. Health outcomes and lifestyle in a sample of people with multiple sclerosis (HOLISM): longitudinal and validation cohorts. Front Neurol. 2019;9:1074. doi: 10.3389/fneur.2018.01074. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Wunderlich M, Heesen C, Haase R, Stellmann JP, Angstwurm K, Marziniak M, et al. Early stages of disability in patients with multiple sclerosis by physician and patient-reported outcomes: A two-year study. Mult Scler J. 2018;Conference(2 Supplement):923. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Fiest KM, Fisk JD, Patten SB, Tremlett H, Wolfson C, Warren S, McKay KA, Berrigan LI, Marrie RA, for the CIHR Team in the Epidemiology and Impact of Comorbidity on Multiple Sclerosis (ECoMS) Fatigue and comorbidities in multiple sclerosis. Int J MS Care. 2016;18(2):96–104. doi: 10.7224/1537-2073.2015-070. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Goretti B, Ghezzi A, Portaccio E, Lori S, Zipoli V, Razzolini L, Moiola L, Falautano M, de Caro MF, Viterbo R, Patti F, Vecchio R, Pozzilli C, Bianchi V, Roscio M, Comi G, Trojano M, Amato MP, Study Group of the Italian Neurological Society Psychosocial issue in children and adolescents with multiple sclerosis. Neurol Sci. 2010;31(4):467–470. doi: 10.1007/s10072-010-0281-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.KSVs G, Blaschek A, Calabrese P, Rostasy K, Huppke P, Kessler JJ, et al. Fatigue and depression predict health-related quality of life in patients with pediatric-onset multiple sclerosis. Multiple Sclerosis Related Disord. 2019;36:101368. doi: 10.1016/j.msard.2019.08.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Florea A, Maurey H, Sauter ML, Bellesme C, Sevin C, Deiva K. Fatigue, depression, and quality of life in children with multiple sclerosis: a comparative study with other demyelinating diseases. DevMed Child Neurol. 2019;2019. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 46.Garcia L, Alvarenga R, Bento C, Filho HA. Evaluation of persistent fatigue in multiple sclerosis patient with low disability. Neurol Therapy. 2019;Conference(Supplement 1):S2. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Larnaout F, Mrabet S, Nasri A, Hmissi L, Djabara MB, Gargouri A, et al. Interplay Between Fatigue and Sleep Disturbances in Patients with Multiple Sclerosis. Multiple Sclerosis Related Disord. 2018;Conference:252. doi: 10.1016/j.msard.2018.10.072. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Rupprecht S, Kluckow S, Witte O, Schwab M. Sleep disturbances, fatigue, anxiety and depression in multiple sclerosis (MS): results of the German SLEEP-MS Survey. J Sleep Res. 2018;Conference(Supplement 1):188. [Google Scholar]

- 49.van der Vuurst de Vries RM, JJvd D, Mescheriakova JY, Runia TF, Jafari N, Siepman TA, et al. Fatigue after a first attack of suspected multiple sclerosis. Multiple Sclerosis (Houndmills, Basingstoke, England) 2018;24(7):974. doi: 10.1177/1352458517709348. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.von Bismarck O, Dankowski T, Ambrosius B, Hessler N, Antony G, Ziegler A, Hoshi MM, Aly L, Luessi F, Groppa S, Klotz L, Meuth SG, Tackenberg B, Stoppe M, Then Bergh F, Tumani H, Kümpfel T, Stangel M, Heesen C, Wildemann B, Paul F, Bayas A, Warnke C, Weber F, Linker RA, Ziemann U, Zettl UK, Zipp F, Wiendl H, Hemmer B, Gold R, Salmen A. Treatment choices and neuropsychological symptoms of a large cohort of early MS. Neurol Neuroimmunol Neuroinflamm. 2018;5(3):e446. doi: 10.1212/NXI.0000000000000446. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Wood B, IAvd M, Ponsonby AL, Pittas F, Quinn S, Dwyer T, et al. Prevalence and concurrence of anxiety, depression and fatigue over time in multiple sclerosis. Multiple Sclerosis (Houndmills, Basingstoke, England) 2013;19(2):217. doi: 10.1177/1352458512450351. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Gravesande K, Storm van's PCA, Blaschek KR, LR PH, JK VM, VK EK, CE ED, et al. The Multiple Sclerosis Inventory of Cognition for Adolescents (MUSICADO): A brief screening instrument to assess cognitive dysfunction, fatigue and loss of health-related quality of life in pediatric-onset multiple sclerosis. Eur J Paediatr Neurol. 2019;23(6):792. doi: 10.1016/j.ejpn.2019.08.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Krupp LB, LaRocca NG, Muir-Nash J, Steinberg AD. The fatigue severity scale: application to patients with multiple sclerosis and systemic lupus erythematosus. Arch Neurol. 1989;46(10):1121–1123. doi: 10.1001/archneur.1989.00520460115022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Lerdal A, Wahl AK, Rustoen T, Hanestad BR, Moum T. Fatigue in the general population: a translation and test of the psychometric properties of the Norwegian version of the fatigue severity scale. Scand J Public Health. 2005;33(2):123–130. doi: 10.1080/14034940410028406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Flachenecker P, Kümpfel T, Kallmann B, Gottschalk M, Grauer O, Rieckmann P, Trenkwalder C, Toyka KV. Fatigue in multiple sclerosis: a comparison of different rating scales and correlation to clinical parameters. Mult Scler. 2002;8(6):523–526. doi: 10.1191/1352458502ms839oa. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Veauthier C, Radbruch H, Gaede G, Pfueller CF, Dörr J, Bellmann-Strobl J, Wernecke KD, Zipp F, Paul F, Sieb JP. Fatigue in multiple sclerosis is closely related to sleep disorders: a polysomnographic cross-sectional study. Mult Scler J. 2011;17(5):613–622. doi: 10.1177/1352458510393772. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Fisk JD, Doble SE. Construction and validation of a fatigue impact scale for daily administration (D-FIS) Qual Life Res. 2002;11(3):263–272. doi: 10.1023/A:1015295106602. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Penner IK, Raselli C, Stöcklin M, Opwis K, Kappos L, Calabrese P. The fatigue scale for motor and cognitive functions (FSMC): validation of a new instrument to assess multiple sclerosis-related fatigue. Mult Scler. 2009;15(12):1509–1517. doi: 10.1177/1352458509348519. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Fiest KM, Fisk JD, Patten SB, Tremlett H, Wolfson C, Warren S, et al. Fatigue and Comorbidities in Multiple Sclerosis. 2016;18(2):96–104. 10.7224/1537-2073.2015-070. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 60.da Silva NL, Takemoto MLS, Damasceno A, Fragoso YD, Finkelsztejn A, Becker J, Gonçalves MVM, Tilbery C, de Oliveira EML, Callegaro D, Boulos FC. Cost analysis of multiple sclerosis in Brazil: a cross-sectional multicenter study. BMC Health Serv Res. 2016;16(1):102. doi: 10.1186/s12913-016-1352-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Grytten N, Skar AB, Aarseth JH, Assmus J, Farbu E, Lode K, et al. The influence of coping styles on long-term employment in multiple sclerosis: a prospective study. Mult Scler. 2017;23(7):1008–1017. doi: 10.1177/1352458516667240. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Koziarska D, Krol J, Nocon D, Kubaszewski P, Rzepa T, Nowacki P. Prevalence and factors leading to unemployment in MS (multiple sclerosis) patients undergoing immunomodulatory treatment in Poland. PLoS One. 2018;13(4):e0194117. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0194117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Lorefice L, Fenu G, Frau J, Coghe G, Marrosu MG, Cocco E. The impact of visible and invisible symptoms on employment status, work and social functioning in multiple sclerosis. Work. 2018;60(2):263–270. doi: 10.3233/WOR-182682. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.McKay KA, Marrie RA, Fisk JD, Patten SB, Tremlett H. Comorbidities are associated with altered health services use in multiple sclerosis: a prospective cohort study. Neuroepidemiology. 2018;51(1–2):1–10. doi: 10.1159/000488799. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Salter A, Thomas N, Tyry T, Cutter G, Marrie RA. Employment and absenteeism in working-age persons with multiple sclerosis. J Med Econ. 2017;20(5):493–502. doi: 10.1080/13696998.2016.1277229. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Beier M, Hartoonian N, D'Orio VL, Terrill AL, Bhattarai J, Paisner ND, et al. Relationship of perceived stress and employment status in individuals with multiple sclerosis. Work. 2019;62(2):243–249. doi: 10.3233/WOR-192859. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Bøe Lunde HM, Telstad W, Grytten N, Kyte L, Aarseth J, Myhr K-M, et al. Employment among patients with multiple sclerosis-a population study. PLoS One. 2014;9(7):e103317-e. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0103317. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Cadden M, Arnett P. Factors associated with employment status in individuals with multiple sclerosis. Int J MS Care. 2015;17(6):284–291. doi: 10.7224/1537-2073.2014-057. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Carnero Contentti E, Lopez P, Balbuena ME, Tkachuk V. Impact of multiple sclerosis on employment and its association with anxiety, Depression, Fatigue and Sleep Disorders. 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 70.Doesburg D, Mokkink W, Vennegoor A, Uitdehaag B, van Oosten B. Sick leave in early MS is associated with fatigue and relapse rate, not disability. 2018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Flensner G, Landtblom AM, Soderhamn O, Ek AC. Work capacity and health-related quality of life among individuals with multiple sclerosis reduced by fatigue: a cross-sectional study. BMC Public Health. 2013;13(1):224. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-13-224. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Glanz BI, Degano IR, Rintell DJ, Chitnis T, Weiner HL, Healy BC. Work productivity in relapsing multiple sclerosis: associations with disability, depression, fatigue, anxiety, cognition, and health-related quality of life. Value Health. 2012;15(8):1029–1035. doi: 10.1016/j.jval.2012.07.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Jongen PJ, Wesnes K, van Geel B, Pop P, Sanders E, Schrijver H, Visser LH, Gilhuis HJ, Sinnige LG, Brands AM, and the COGNISEC study group Relationship between working hours and power of attention, memory, fatigue, depression and self-efficacy one year after diagnosis of clinically isolated syndrome and relapsing remitting multiple sclerosis. PLoS One. 2014;9(5):e96444. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0096444. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Moore P, Harding KE, Clarkson H, Pickersgill TP, Wardle M, Robertson NP. Demographic and clinical factors associated with changes in employment in multiple sclerosis. Mult Scler. 2013;19(12):1647–1654. doi: 10.1177/1352458513481396. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Ness N-H, Haase R, Cornelissen C, Ziemssen T. Link between health-related quality of life, occupational disability and sick leaves in patients with multiple sclerosis in Germany. 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 76.Povolo CA, Blair M, Mehta S, Rosehart H, Morrow SA. Predictors of vocational status among persons with multiple sclerosis. Mult Scler Relat Disord. 2019;36:101411. doi: 10.1016/j.msard.2019.101411. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]