Abstract

We report a case of Pasteurella multocida meningitis in a 1-month-old baby exposed to close contact with two dogs and a cat but without any known history of injury by these animals. 16S rRNA gene sequencing of the isolate from the baby allowed identification at the subspecies level and pointed to the cat as a possible source of infection. Molecular typing of Pasteurella isolates from the animals, from the baby, and from unrelated animals clearly confirmed that the cat harbored the same P. multocida subsp. septica strain on its tonsils as the one isolated from the cerebrospinal fluid of the baby. This case stresses the necessity of informing susceptible hosts at risk of contracting zoonotic agents about some basic hygiene rules when keeping pets. In addition, this study illustrates the usefulness of molecular methods for identification and epidemiological tracing of Pasteurella isolates.

A previously healthy 1-month-old baby from a rural area of Switzerland was admitted to the pediatric ward of the local hospital in the winter of 1998 to 1999. The baby presented with an irritable state, a temperature of 39°C, and signs of slightly increased intracranial pressure. A lumbar puncture was performed, and the cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) was positive for numerous polymorphonuclear leukocytes and small gram-negative bacilli. After 24 h of incubation, a small, catalase-positive, oxidase-positive and indole-positive gram-negative coccobacillus grew on sheep blood and chocolate agar plates, as well as in thioglycolate enrichment broth. Formal identification of Pasteurella multocida was achieved using the API 20NE system (bioMérieux, Marcy-l'Etoile, France). The organism was susceptible to all tested beta-lactam antibiotics. The patient was successfully treated with ceftriaxone (400 mg/day) for 2 weeks, until complete recovery. An inquiry revealed that the baby had no brother or sister but had been in close contact with two dogs and possibly a cat through a misguided attempt by the parents to promote bonding between the baby and the family's pets. This suggested a probable animal source of infection.

Shortly after the identification of the incriminated pathogen, swab samples were taken from the throats and tonsils of the parents, of the two dogs, and of the cat which had been in contact with the baby. Swabs from the parents were cultured on 5% sheep blood agar, on chocolate agar, and on MacConkey agar, in the same way as the CSF sample of the baby. Cultures of the samples from the dogs and from the cat were made on 5% sheep blood agar plates in a 5% CO2 atmosphere and on MacConkey agar plates. Phenotypic species identification of oxidase- and catalase-positive gram-negative bacilli was made on the basis of the following tests: motility; glucose metabolism (oxidative-fermentative); production of indole, urease, lysine decarboxylase, and ornithine decarboxylase; production of acid from glucose, lactose, salicin, trehalose, sorbitol, and mannitol; and production of gas from glucose and mannitol. Reaction mixtures were incubated for 5 days before definitive reading, but no change was observed later than after the first overnight incubation. Phenotypic identification of Pasteurellaceae from clinical material is occasionally unprecise, leading to improper species designation (5) or making identification at the species and subspecies levels impossible (17). We therefore routinely confirm identification of Pasteurella isolates by comparison of the 16S rRNA gene sequence with a reference database of sequences. This allows more precise and generally unambiguous species identification at the genotype level. The database contains more than 6,000 16S rRNA gene sequences from type strains, reference strains, and clinical isolates with a strong emphasis on the Pasteurellaceae family. The database contains, among others, 16S rRNA gene sequences of the type strains and of 40 representative clinical isolates of the three P. multocida subspecies and shows that P. multocida subsp. septica can clearly be distinguished by a 2% sequence divergence from the two other P. multocida subspecies multocida and gallicida (P. Kuhnert, unpublished data). 16S rRNA gene sequencing was done as previously described (15), and comparison to our reference 16S rRNA gene sequence database was done using BLAST (1). Nine additional P. multocida isolates originating from eight unrelated cats and belonging to the same 16S rRNA gene cluster as P. multocida subsp. septica type strain CCUG 17977T (Culture Collection of the University of Göteborg; identical to NCTC 11995) were used for comparison. Less than 0.3% 16S rRNA gene sequence variation was observed within this cluster.

No Pasteurella organisms could be detected and isolated from the cultures made with the samples taken from the parents. However, a Pasteurella strain was isolated from the tonsils of the cat which had been in contact with the baby. This isolate had the same P. multocida biochemical profile as the isolate from the CSF of the baby (typical profile for P. multocida, trehalose-negative and sorbitol-positive reactions). 16S rRNA gene sequencing and comparison with our reference database led to the unambiguous identification of these two isolates as P. multocida subsp. septica (100% identity with the P. multocida subsp. septica type strain, 0.28% divergence from the less closely related P. multocida subsp. septica isolate of our database, and 1.85% divergence from the most closely related isolate of the two other P. multocida subspecies). A second isolate from the cat (oral cavity) showed a biochemical profile compatible with an unidentifiable Pasteurella species. This latter profile was identical to the profile obtained with an isolate from one of the dogs which had also been in contact with the baby. Another isolate from the second dog which had contacts with the baby also had a biochemical profile compatible with an unidentifiable Pasteurella species (data not shown). 16S rRNA gene sequencing did not allow further identification of the latter three isolates to the species level but confirmed their affiliation with the Haemophilus-Pasteurella-Actinobacillus cluster and clearly distinguished them from the baby's isolate (6% or more sequence divergence compared to the P. multocida subsp. septica isolate from the baby and to the Pasteurella multocida subsp. septica cluster in general).

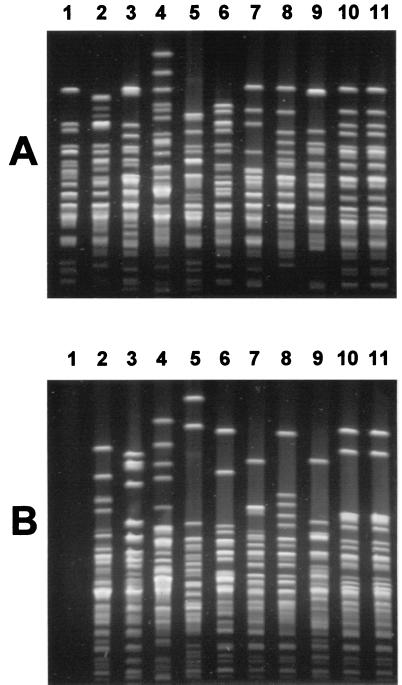

The P. multocida subsp. septica isolates were typed by ribotyping and macrorestriction analysis. Ribotyping was performed as described elsewhere (8). Briefly, DNA was extracted using guanidium thiocyanate (20) and digested with the restriction enzymes HindIII and EcoRI following the manufacturer's (Roche Diagnostics, Rotkreuz, Switzerland) instructions. The resulting fragments were separated by agarose gel electrophoresis and transferred by vacuum blotting on positively charged nylon membranes (Roche Diagnostics). A digoxigenin-labeled probe specific for 16S rRNA genes was prepared by PCR and used for hybridizations, and the hybridization patterns were revealed using the digoxigenin luminescence kit (Roche Diagnostics). For macrorestriction analysis, bacteria were grown on sheep blood agar plates and resuspended in TE (10 mM Tris, 1 mM EDTA, pH 8.0) to a final optical density at 600 nm of 4.0. The suspensions were mixed with an equal volume of melted 1.2% SeaKem Gold agarose (FMC, Rockland, Maine), and 1-mm-thick plugs were prepared. The plugs were incubated overnight at 50°C in 0.5 M EDTA–1% lauroylsarcosine containing 2 mg of proteinase K per ml and washed five times for 45 min each time in TE. The DNA was subsequently digested for 4 h with 30 U of SalI or SmaI under conditions described by the manufacturer (Roche Diagnostics). The resulting DNA fragments were separated with a CHEF III electrophoresis system (Bio-Rad, Hercules, Calif.) in 1% SeaKem Gold agarose gels (FMC) for 16 h in 0.5 × Tris-borate-EDTA at 14°C by applying an electric field of 6 V/cm with an angle of 120°C and a linear ramping ranging of 1.5 to 17 s. Gels were stained in 1 mg of ethidium bromide per ml and destained in water before photography under UV light. Results of ribotyping and macrorestriction analysis are summarized in Table 1. Only three very similar ribotypes could be distinguished when using the restriction enzyme HindIII, with nine isolates belonging to a single type (Table 1). These three ribotypes were clearly different from those recently described for P. multocida subsp. multocida (9), thus confirming their identification as P. multocida subsp. septica. EcoRI was more discriminatory (Table 1), but the profiles obtained with this enzyme remained relatively similar and were difficult to read because of the presence of variable bands in the high-molecular-weight range (data not shown). The isolates from the baby and from the cat had identical ribotypes with both restriction enzymes. Macrorestriction profiles were easy to read and allowed us to distinguish all of the P. multocida subsp. septica isolates from one another, except those from the baby and the contact cat, which remained identical (Fig. 1).

TABLE 1.

Ribotypes and macrorestriction profiles obtained with 11 P. multocida subsp. septica isolatesa

| Isolate | Ribotyping analysis

|

Macrorestriction analysis

|

||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| HindIII | EcoRI | SalI | SmaI | |

| D25/99b | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| D129/99b | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 |

| D138/99b | 1 | 3 | 3 | 3 |

| D167/99b | 3 | 4 | 4 | 4 |

| D496/99b | 1 | 5 | 5 | 5 |

| D514/99b | 1 | 6 | 6 | 6 |

| D755/99b | 1 | 7 | 7 | 7 |

| D777a/99b | 1 | 8 | 8 | 8 |

| D777b/99b | 1 | 9 | 9 | 9 |

| D590/99c | 1 | 10 | 10 | 10 |

| D708/99d | 1 | 10 | 10 | 10 |

The numbers in columns 2 to 5 represent random numbering of the profiles obtained by ribotyping and macrorestriction analysis.

One of nine P. multocida subsp. septica isolates from eight epidemiologically unrelated cats.

P. multocida subsp. septica isolate from the baby.

P. multocida subsp. septica isolate from the contact cat.

FIG. 1.

Macrorestriction analysis of P. multocida subsp. septica isolates. (A) Macrorestriction profiles of Pasteurella isolates obtained after digestion with SalI. Lanes: 1 to 9, P. multocida subsp. septica isolates from unrelated cats; 10 and 11, P. multocida subsp. septica isolates from the baby and from the contact cat, respectively. (B) Macrorestriction profiles of Pasteurella isolates obtained after digestion with SmaI. Isolates are in the same order as in panel A. The DNA in lane 1, isolate remained uncut because of methylation.

Cattle, pigs, and poultry have been incriminated in the past as the major sources of human infections with zoonotic agents. However, humans have very frequent and close contacts with pets, an often forgotten source of zoonoses. In the particular case of Pasteurella infections, animal bites and scratches are the major sources of infection for humans (11). P. multocida subsp. multocida represents the majority of Pasteurella isolates from these cases, followed by a smaller proproportion of P. canis and P. multocida subsp. septica (12). P. multocida subsp. multocida has been previously associated with dogs, and P. multocida subsp. septica has been associated with cats (4). Analysis of our sequence database also confirms the strong association of clinical isolates of the P. multocida subsp. septica 16S rRNA gene cluster with cats (data not shown), including isolates with atypical biochemical profiles (one ornithine decarboxylase-negative isolate and several isolates with variable reactions for trehalose and sorbitol). Especially the subspecies may be difficult to identify using conventional phenotypic testing. In contrast, the identification of P. multocida subsp. septica by 16S rRNA gene sequencing at the subspecies level was unequivocal for the CSF isolate of the baby and therefore pointed to the cat as the origin of the infection. This hypothesis was also supported by previous reports of transmission of P. multocida subsp. septica between cats and babies (2, 18). As in the present case, a significant proproportion of P. multocida infections in humans are associated with animal exposure without any injury (3, 10, 13, 16, 19). Moreover, some systemic infections can even not be associated with any animal exposure at all (7, 16). In such cases, only the comparison of environmental and clinical isolates with discriminatory and reproducible typing methods is able to demonstrate any link between a potential source of infection and a particular clinical case. Molecular typing methods like restriction enzyme analysis (16, 23), random amplification of polymorphic DNA (20), ribotyping (2, 9), and macrorestriction analysis (6, 14, 22) have been used for typing of members of the genus Pasteurella and have been shown to be good tools for epidemiological tracing. In the present case, the molecular analysis of the isolates demonstrated the identity of the P. multocida subsp. septica strains from the cat and the baby. The analysis of additional, unrelated P. multocida subsp. septica isolates demonstrated the high discriminatory power of ribotyping and particularly of macrorestriction analysis for this Pasteurella subspecies and confirmed that the identity of the profiles for the cat and human isolates was not fortuitous. Inhalation or licking and oral transmission has been suggested by others as a possible infection route for those patients without injury (7, 12) and is likely to have occurred in the present case. A particular tropism of P. multocida subsp. septica for the central nervous system has been suggested by others (4), which fits our particular case.

To our knowledge, this is the first report of a P. multocida subsp. septica meningitis in which the organism was transmitted without any injury from a cat to a baby to be clearly documented by genotypic and molecular epidemiological methods. The baby had been massively exposed to the dogs by licking but less clearly to the cat, and only the use of molecular identification and typing methods unequivocally led to the discovery of the unexpected association between the cat and the baby. Finally, the present case stresses the danger of casual contact between humans and pets. In view of the very frequent contacts between pets and humans (10) and the low number of reported P. multocida infections, the risk of transmission of this zoonotic agent from domestic animals to humans is probably very low. However, some basic rules of hygiene should be respected when immunocompromised patients, small children, and the elderly come into contact with pets (7, 16). Predisposed persons may have to be made aware of these precautions. Since the limited phenotypic identification tests applicable in a routine diagnostic laboratory would have misidentified several of the P. multocida subsp. septica isolates used in this study, the present work exemplifies the need for molecular identification methods for taxa such as members of the family Pasteurellaceae. Finally, our results also clearly illustrate the potentials of pulsed-field gel electrophoresis for epidemiological tracing of the occurrence of P. multocida infections in humans.

REFERENCES

- 1.Altschul S F, Gish W, Miller W, Myers E W, Lipman D J. Basic local alignment search tool. J Mol Biol. 1990;215:403–410. doi: 10.1016/S0022-2836(05)80360-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Andersson S, Larinkari U, Vartia T, Forsblom B, Saarela M, Rautio M, Seppälä I, Schildt R, Kivijärvi A, Haavisto H, Jousimies-Somer H. Fatal congenital pneumonia caused by cat-derived Pasteurella multocida. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 1994;13:74–75. doi: 10.1097/00006454-199401000-00017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Armengol S, Mesalles E, Domingo C, Samso E, Manterolas J. A new case of meningitis due to Pasteurella multocida. Rev Infect Dis. 1991;13:1254. doi: 10.1093/clinids/13.6.1254. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Biberstein E L, Jang S S, Kass P H, Hirsch D C. Distribution of indole-producing urease-negative pasteurellas in animals. J Vet Diagn Investig. 1991;3:319–323. doi: 10.1177/104063879100300408. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bisgaard M, Falsen E. Reinvestigation and reclassification of a collection of 56 human isolates of Pasteurellaceae. Acta Pathol Microbiol Immunol Scand. 1986;94:215–222. doi: 10.1111/j.1699-0463.1986.tb03044.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Blackwood R A, Rode C K, Read J S, Law I H, Bloch C A. Genomic fingerprinting by pulsed field gel electrophoresis to identify the source of Pasteurella multocida sepsis. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 1996;15:831–833. doi: 10.1097/00006454-199609000-00020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Boocock G R, Bowley J A. Meningitis in infancy by Pasteurella multocida. J Infect. 1995;31:161–162. doi: 10.1016/s0163-4453(95)92310-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Burnens A P, Frey A, Nicolet J. Association between clinical presentation, biogroups and virulence attributes of Yersinia enterocolitica strains in human diarrhoeal disease. Epidemiol Infect. 1996;116:27–34. doi: 10.1017/s0950268800058921. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Fussing V, Nielsen J P, Bisgaard M, Meyling A. Development of a typing system for epidemiological studies of porcine toxin-producing Pasteurella multocida ssp. multocida in Denmark. Vet Microbiol. 1999;65:61–74. doi: 10.1016/s0378-1135(98)00288-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Genne D, Siegrist H H, Monnier P, Nobel M, Humair L, de Torrente A. Pasteurella multocida endocarditis: report of a case and review of the literature. Scand J Infect Dis. 1996;28:95–97. doi: 10.3109/00365549609027158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Holmes B, Pickett M J, Hollis D G. Pasteurella. In: Murray P R, Baron E J, Pfaller M A, Tenover F C, Yolken R H, editors. Manual of clinical microbiology. Washington, D.C.: American Society for Microbiology; 1999. pp. 632–637. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Holst E, Rollof J, Larsson L, Nielsen J P. Characterization and distribution of Pasteurella species recovered from infected humans. J Clin Microbiol. 1992;30:2984–2987. doi: 10.1128/jcm.30.11.2984-2987.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hubbert W T, Rosen M N. Pasteurella multocida infections in man unrelated to animal bite. Am J Public Health. 1970;60:1109–1117. doi: 10.2105/ajph.60.6.1109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kodjo L, Villard L, Bizet C, Martel J-L, Sanchis R, Borges E, Gauthier D, Maurin F, Richard Y. Pulsed-field gel electrophoresis is more efficient than ribotyping and random amplified polymorphic DNA analysis in discrimination of Pasteurella haemolytica strains. J Clin Microbiol. 1999;37:380–385. doi: 10.1128/jcm.37.2.380-385.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kuhnert P, Capaul S E, Nicolet J, Frey J. Phylogenetic positions of Clostridium chauvoei and Clostridium septicum based on 16S rRNA gene sequences. Int J Syst Bacteriol. 1996;46:1174–1176. doi: 10.1099/00207713-46-4-1174. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kumar A, Devlin H R, Vellend H. Pasteurella multocida in an adult: case report and review. Rev Infect Dis. 1990;12:440–448. doi: 10.1093/clinids/12.3.440. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lindberg J, Frederiksen W, Gahrn-Hansen B, Bruun B. Problems of identification in clinical microbiology exemplified by pig bite wound infections. Zentl Bakteriol. 1998;288:491–499. doi: 10.1016/s0934-8840(98)80067-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Miller J J, Gray B M. Pasteurella multocida meningitis presenting as fever without a source in a young infant. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 1995;14:331–332. doi: 10.1097/00006454-199504000-00021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Parry C M, Cheesbrough J S, O'Sulivan G. Meningitis due to Pasteurella multocida. Rev Infect Dis. 1991;13:187. doi: 10.1093/clinids/12.5.187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Pitcher D G, Saunders N A, Owen R J. Rapid extraction of bacterial genomic DNA with guanidium thiocyanate. Lett Appl Microbiol. 1989;8:151–156. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Schuur P M H, Haring A J P, van Belkum A, Draaisma J M, Buiting A G M. Use of random amplification of polymorphic DNA in a case of Pasteurella multocida meningitis that occurred following a cat scratch on the head. Clin Infect Dis. 1996;24:1004–1006. doi: 10.1093/clinids/24.5.1004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Townsend K M, Dawkins H J S, Papadimitriou J M. Analysis of hemorrhagic septicemia-causing isolates of Pasteurella multocida by ribotyping and field alternation gel electrophoresis (FAGE) Vet Microbiol. 1997;57:383–395. doi: 10.1016/s0378-1135(97)00121-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Vasquez J E, Ferguson D A, Bin-Sagheer S, Myers J W, Ramsak A, Wilson M A, Sarubbi F A. Pasteurella multocida endocarditis: a molecular epidemiological study. Clin Infect Dis. 1998;26:518–520. doi: 10.1086/517105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]