Abstract

Death from opioid overdose is typically caused by opioid-induced respiratory depression (OIRD). A particularly dangerous characteristic of OIRD is its apparent unpredictability. The respiratory consequences of opioids can be surprisingly inconsistent, even within the same individual. Despite significant clinical implications, most studies have focused on average dose–r esponses rather than individual variation, and there remains little insight into the etiology of this apparent unpredictability. The preBötzinger complex (preBötC) in the ventral medulla is an important site for generating the respiratory rhythm and OIRD. Here, using male and female C57-Bl6 mice in vitro, we demonstrate that the preBötC can assume different network states depending on the excitability of the preBötC and the intrinsic membrane properties of preBötC neurons. These network states predict the functional consequences of opioids in the preBötC, and depending on network state, respiratory rhythmogenesis can be either stabilized or suppressed by opioids. We hypothesize that the dynamic nature of preBötC rhythmogenic properties, required to endow breathing with remarkable flexibility, also plays a key role in the dangerous unpredictability of OIRD.

SIGNIFICANCE STATEMENT Opioids can cause unpredictable, life-threatening suppression of breathing. This apparent unpredictability makes clinical management of opioids difficult while also making it challenging to define the underlying mechanisms of OIRD. Here, we find in brainstem slices that the preBötC, an opioid-sensitive subregion of the brainstem, has an optimal configuration of cellular and network properties that results in a maximally stable breathing rhythm. These properties are dynamic, and the state of each individual preBötC network relative to the optimal configuration of the network predicts how vulnerable rhythmogenesis is to the effects of opioids. These insights establish a framework for understanding how endogenous and exogenous modulation of the rhythmogenic state of the preBötC can increase or decrease the risk of OIRD.

Keywords: network, opioid, preBötzinger, respiratory, rhythm, stability

Introduction

The use of opioids remains a mainstay for the clinical management of pain (McQuay, 1999; Niscola et al., 2006; Kuehn, 2007; Dowell et al., 2013). Yet, despite the analgesic utility, opioids pose a major risk with overdose often resulting in death (Rudd et al., 2016; Scholl et al., 2018; Seth et al., 2018). According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, currently ∼130 U.S citizens die every day from opioid overdose, a rate of death six times that of 20 years ago. Opioid-induced respiratory depression (OIRD) is the most common cause of death associated with opioid use. An important contributor to the high mortality rate is the apparent unpredictable response of the respiratory network to opioids. The respiratory consequences of opioid use can vary substantially between individuals and can also be surprisingly inconsistent even within the same individual (Cherny et al., 2001; Dahan et al., 2013; Fleming et al., 2015). However, it is not clear where this variability originates, and the mechanisms that underlie this dangerous feature of OIRD remain elusive.

Multiple interacting regions throughout the brain and brainstem can contribute to OIRD (Gruhzit, 1957; Hurlé et al., 1982, 1983; Keifer et al., 1992; Ballanyi et al., 1997; Wojciechowski et al., 2007; Montandon et al., 2011; Prkic et al., 2012; Zhang et al., 2012; Lalley et al., 2014; Stucke et al., 2015). Yet, discrete nuclei involved in the control of breathing play prominent roles (Varga et al., 2019, 2020; Bachmutsky et al., 2020). Within the brainstem, rhythmic respiratory activity is produced and shaped through interactions between a distributed network located bilaterally along the ventrolateral medulla (Baekey et al., 2004; Baertsch et al., 2019) and certain areas within the pons (Levitt et al., 2015; Saunders and Levitt, 2020). Of particular importance is the opioid-sensitive preBötzinger complex (preBötC), which produces periodic inspiratory activity fundamental to mammalian breathing. Perturbing this region in vivo can result in respiratory failure and fatal apnea (Wenninger et al., 2004), and when isolated in vitro, the preBötC remains sufficient for rhythmogenesis (Smith et al., 1991; Ramirez et al., 1998; Gray et al., 2001; Wenninger et al., 2004). The duration between inspiratory bursts is the primary determinant of breathing frequency and becomes dramatically prolonged during OIRD (Ramirez et al., 2021). The interval between inspirations is influenced by a gradual increase in excitation among preBötC neurons that eventually synchronize to produce a population burst (Kam et al., 2013; Baertsch and Ramirez, 2019). Implicated in this process are network-based mechanisms involving synaptic interactions between interconnected excitatory and inhibitory neurons, as well as intrinsic-based mechanisms within the preBötC involving burst-promoting inward cation currents such as the persistent sodium current (INaP; Rekling and Feldman, 1998; Del Negro et al., 2005, 2008; Ramirez and Baertsch, 2018b). The contributions of these intertwined mechanisms are not static, but can be dynamically tuned, for example, by changes in excitability and neuromodulatory inputs (Tryba et al., 2006), to endow breathing with the flexibility and adaptability required to meet ever changing metabolic and behavioral demands (Ramirez and Baertsch, 2018a).

Here, we test the hypothesis that the dynamic nature of these rhythmogenic properties plays a key role in the unpredictability of OIRD. We find that the ability of opioids to suppress rhythmogenesis in vitro varies significantly between individual preBötC networks, and that the excitability of a given network is predictive of its individual response to opioid exposure. Furthermore, we demonstrate that modulation of either network excitability or the activity of INaP within any individual network in vitro can alter susceptibility to OIRD. The concept that the respiratory network can assume different rhythmogenic states in vitro with different sensitivity to OIRD may provide a novel framework for improving the predictability of OIRD and inspire new strategies for prevention and reversal of OIRD.

Materials and Methods

Animals

All experiments were performed on male and female neonatal [postnatal (P)4–P12] C57-Bl6 mice bred at Seattle Children's Research Institute in accordance with Seattle Children's Research Institute Animal Care and Use Committee and National Institutes of Health guidelines. Mice were group housed and given access to food and water ad libitum. Light/dark cycles were maintained at 12 h each and temperature controlled at 22 ± 1°C.

In vitro medullary slice preparation and recording

Horizontal medullary slices containing the ventral respiratory column were obtained and prepared from neonatal mice between P4 and P12, as described previously (Baertsch et al., 2019). Briefly, whole brainstems were dissected, and the dorsal surface glued onto an agar block cut at ∼15° angle. The brainstem was sectioned at 200 μm stepwise in the transverse plane until prominence of the facial nerves (VII) were visualized. The block was then reoriented to position the ventral surface upward with the rostral surface adjacent to the vibratome blade. The blade was manually aligned flush with ventral surface on rostral end of the tissue. Following blade alignment, a single 850 μm section was obtained to generate the horizontal slice. The horizontal slice contains the ventral respiratory column extending from the spinal cord to the prominence of the facial nerve. However, the dorsal aspects of the brainstem and areas rostral to the facial nerve are omitted. Nuclei within the ventral aspects of the medulla are preserved such as the ventrolateral medulla and the preinspiratory complex. Dissection and tissue sectioning occurred in ice-cold artificial (a)CSF with an osmolarity between 305 and 312 mOsm, containing the following (in mm): 118 NaCl, 3.0 KCL, 25 NaHCO3, 1 MgCL2, 1.5 CaCl2, 30 D-glucose) equilibrated with carbogen (95% O2, 5% CO2); pH remained 7.4 ± 0.05 when equilibrated with carbogen.

Slices were placed in a recording chamber with circulating aCSF (15 ml/min) warmed to 30°C for subsequent study. The aCSF [K+] was varied between 3 and 14 mm in accordance with each experimental condition. At least 10 min was allowed between each stepwise increase in [K+]. Extracellular neuronal population recordings were obtained at the preBötC, as described previously (Baertsch et al., 2019). Briefly, the preBötC within horizontal slices can be located one-half to three-fourths of the distance between the midline and lateral edge of the slice at the level of the rostral end of central canal opening on an ∼850 μm brainstem slice. Extracellular neuronal population activity was recorded using glass suction pipettes (tip resistance <1 MΩ) filled with aCSF positioned on the surface of the slice. Signals were recorded at 10 kHz through an AC Differential Amplifier (A-M Systems), amplified by 10 K, bandpass filtered between 300 Hz and 5 kHz, rectified, integrated, digitized (Digidata 1550A, Molecular Devices), acquired in pClamp software (Molecular Devices), and analyzed post hoc with Clampfit software. For drug application, drugs were bath applied sequentially in 10 min intervals.

Analysis and statistics

To quantify the variability of neuronal bursting we define the irregularity score (IRS) as follows:

| (1) |

and stability () was then calculated as follows:

| (2) |

Extracellular neuronal population recordings were analyzed burst to burst from the integrated population signal. Bursting characteristic measurements represent the last 2 min within a 10 min window following either bath application of K+ or drug. Bursting characteristics were normalized to appropriate control periods for each set of conditions. Xn represents the peak amplitude or interburst interval of the nth burst, and Xn−1 as peak amplitude or interburst interval of the preceding burst. For extracellular population recordings, we calculate the burst stability with Equations 1 and 2, with as the peak burst amplitude, as the time of population burst onset, and as the time of the prior burst offset. Burst stability represents a quantitative value of how similar a successive set of inspiratory burst cycles are as a function of peak burst amplitude and the interburst interval.

Burst stability was measured independently for each K+ concentration and then normalized by the maximal stability. Normal distribution of data was assessed with a D'Agostino–Pearson normality test before statistical assessment. Differences in bursting characteristics, IRS, and stability between control and drug-applied conditions were determined by a paired t test, one-way repeated-measures ANOVA, or two-way repeated-measures ANOVA, with statistical significance representing p < 0.05.

Spike train correlations were computed using the spike time tiling coefficient (Cutts and Eglen, 2014) with

All statistics throughout the study were computed using GraphPad Prism.

Neuropixels recordings

In three slices, high-density Neuropixels probes (Imec; Jun et al., 2017) were used to simultaneously record many single neurons. The Neuropixels probes have been described in detail previously (Jun et al., 2017). Briefly, they consist of 384 recordings sites packed along a 70 μm × 4 mm probe with a pitch of 20 μm, allowing for simultaneous, extracellular recording of many single neurons. Horizontal slices were prepared as above. An extracellular population recording was first obtained to determine the approximate location of the preBötzinger complex as evidenced by rhythmic population bursting in 8 mm K+ aCSF. A single Neuropixels probe was inserted contralaterally to the population electrode, at approximately a 45° angle to the horizontal surface of the brain slice through the preBötzinger complex. About 100 of the 384 available channels were in contact with the brain tissue during recordings. aCSF [K+] was then reduced to 3 mm before recording began. Recordings from Neuropixels probe and the integrated contralateral population recording were acquired with SpikeGLX (release 20200520; https://billkarsh.github.io/SpikeGLX). Neuropixels probes were set to action potential gain = 500, local field potential gain = 250, recorded from bank 0, and an external reference was soldered to a silver wire and submerged in the slice bath. Neuropixels traces were filtered first with a local common average reference filter, and spikes were sorted off-line with Kilosort2 (Steinmetz et al., 2021) to obtain spike times of simultaneously recorded, putative single neurons.

Results

Variation in the susceptibility to OIRD within the inspiratory rhythm generating network in vitro

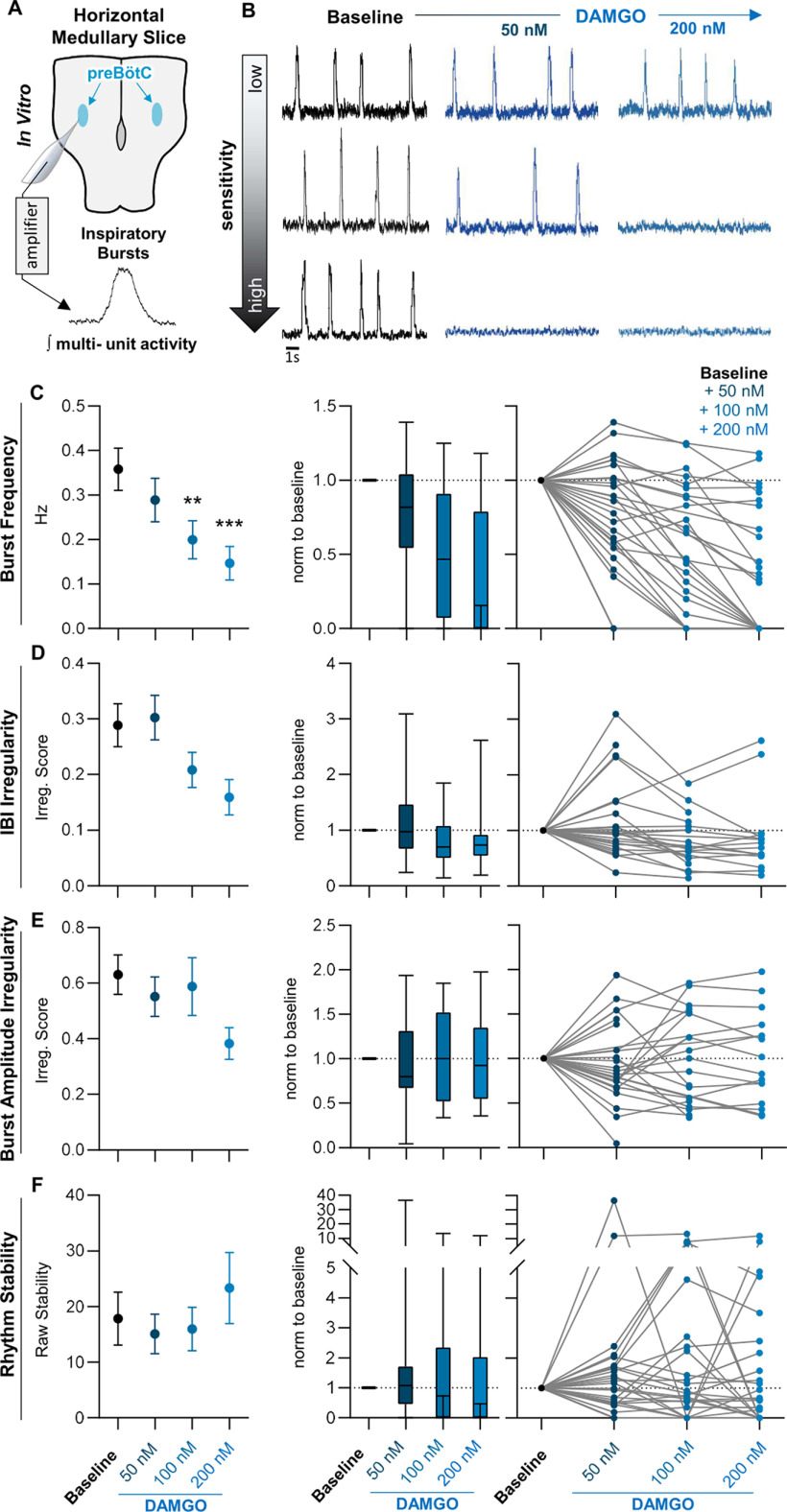

Because systemic morphine has been shown to have variable effects on the breathing rhythm, we examined whether this variability is preserved in horizontal brainstem slice preparations containing the respiratory rhythm generating network (Fig. 1A). Horizontal slice preparations preserve the ventral respiratory column rostrocaudally, including the autonomously rhythmic preBötC as well as neurons rostral to the preBötC that may also contribute to rhythmogenesis (Baertsch et al., 2019). Yet, horizontal slices exclude other sources of respiratory control, for example, chemosensory and mechanosensory inputs from areas such as the nucleus tractus solitarius and the carotid bodies that can regulate breathing pattern. Neuronal population activity was recorded from the preBötC under control conditions in 8 mm [K+] aCSF before and after increasing doses of the synthetic μ-opioid receptor agonist [d-Ala2, N-MePhe4, Gly-ol]-enkephalin (DAMGO). As expected from previous reports (Mellen et al., 2003; Montandon et al., 2011; Wei and Ramirez, 2019), we found a mean depression of the respiratory rhythm following 50–200 nm DAMGO administration (−20 ± 14% from control at 50 nm, −44 ± 12% at 100 nm, and −60 ± 10% at 200 nm, p < 0.001, F = 20.6, n = 28, df = 27; Fig. 1B,C). Yet, across individual slice preparations, changes in population burst frequency elicited by DAMGO were highly variable. In some slices, the inspiratory rhythm was completely suppressed at 50 nm DAMGO, whereas in others the rhythm remained relatively unperturbed by DAMGO concentrations as high as 200 nm (Fig. 1C). Similar variable responses were observed for both the interburst-interval irregularity (p = 0.01, F = 4.7, N = 28, df = 27) and burst amplitude irregularity (p = 0.12, F = 2.1, N = 28, df = 27; Fig. 1D,E), as well as the overall stability (p = 0.35, F = 1.1, N = 28, df = 27; Eqs. 1, 2) of the rhythm, which increased in some, but decreased in others, following DAMGO administration (Fig. 1F). These results demonstrate that the net suppressive effect of DAMGO on the frequency and regularity of the inspiratory rhythm involves a wide range of individual responses.

Figure 1.

The functional consequences of opioids in the preBötC are variable in vitro. A, Horizontal brainstem slice preparations were used to compare the effects of opioids on the inspiratory rhythm across different preBötC networks. Integrated population bursts represent fictive inspiratory activity. B, C, Horizontal slices showed a wide range of responses to bath application of 50–200 nm DAMGO with some slices silenced by 50 nm DAMGO (bottom), whereas others showed little to no response up to 200 nm (top). C, Despite the variation in individual responses, the mean effect was a dose-dependent decrease in burst frequency with increasing doses of DAMGO. D, E, The IRS of the interburst interval (D) and peak amplitude (E) across successive population bursts increased in some slices and decreased in others following bath application of DAMGO from 50 to 200 nm DAMGO. F, Changes in rhythm stability following DAMGO application similarly showed variation across slices with some slices increasing stability, and others decreasing stability with subsequent DAMGO application. Left, Graphs show means ± SE. Middle, Graphs show median, interquartile rage, and minimum/maximum. Right, Graphs show individual replicates. **,***p < 0.05, significantly different from control value. Repeated-measures mixed-model analysis with Sidak's multiple comparisons was used to determine significant differences across doses.

Peak stability of the inspiratory rhythm occurs at variable levels of network excitability

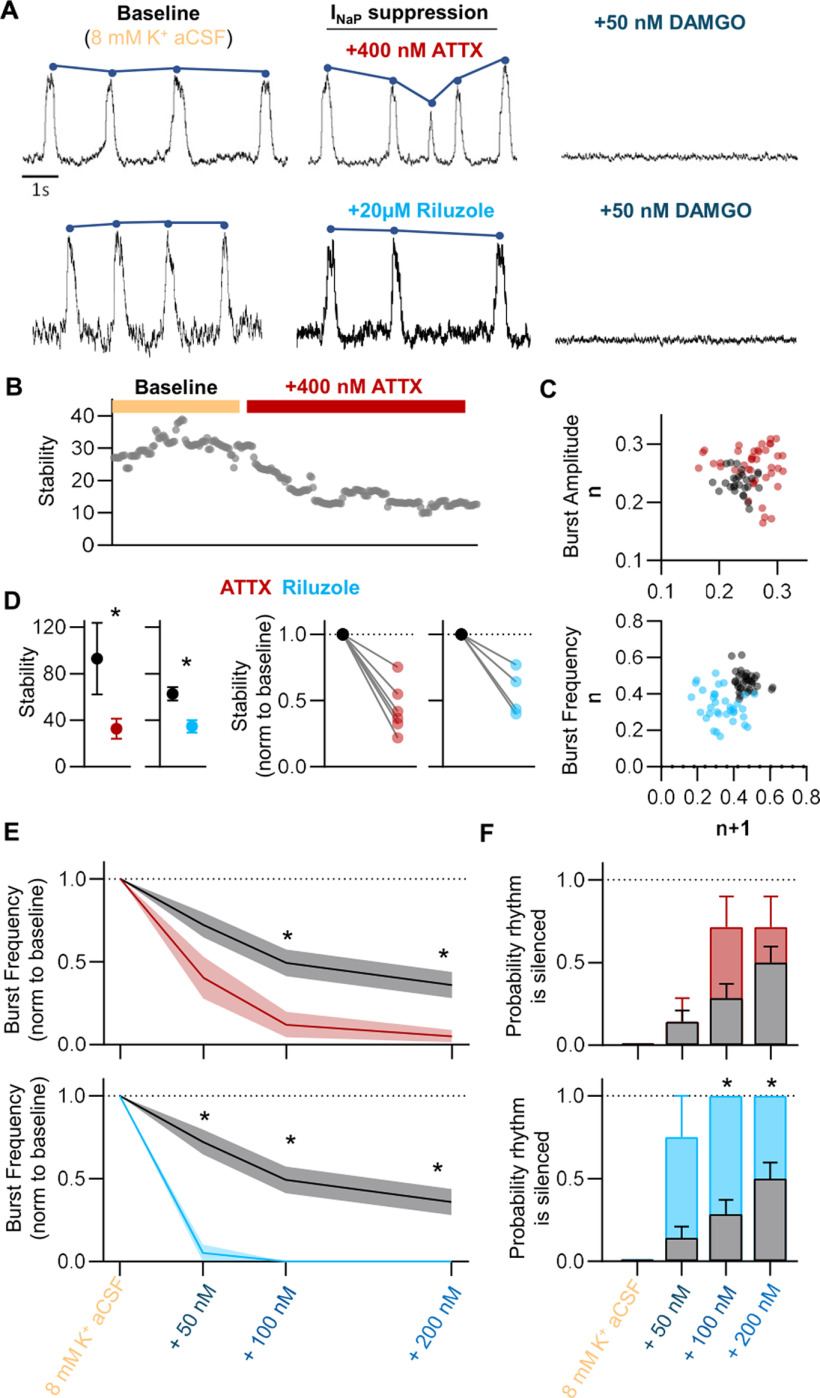

When assessing preBötC population activity, transverse brainstem slices are routinely exposed to elevated extracellular [K+] (8–9 mm) to boost network excitability ensuring they are consistently rhythmically active (Smith et al., 1991; Del Negro et al., 2009). However, it is known that transverse brainstem slice preparations can also generate rhythmic activity at 3 mm extracellular [K+] (Tryba et al., 2003; Ruangkittisakul et al., 2006, 2008). Because transverse slices contain a relatively small portion of the ventral respiratory network, it is hypothesized that only slices that accurately capture the entire preBötC are rhythmic at 3 mm extracellular [K+] (Ruangkittisakul et al., 2008). However, to our surprise we found that despite containing the entire preBötC, many horizontal slices also fail to produce a population rhythm at 3 mm [K+]. Indeed, similar to transverse slices, the specific amount of aCSF [K+] required to induce population bursting was variable among individual horizontal slices; 24% were rhythmic at 3 mm [K+] (n = 7/29), 10% required 5 mm [K+] (n = 3/29), 17% required 6.5 mm [K+] (n = 5/29), and 48% of horizontal slices required aCSF [K+] to be raised to 8 mm before the inspiratory rhythm emerged (n = 14/29; Fig. 2A). Unexpectedly, we found that on initiation of rhythmic population bursting, further increases in aCSF [K+] could cause either an increase or decrease in the regularity of the rhythm (Fig. 2B). Based on this finding, we hypothesized that each individual slice has an optimal level of aCSF [K+], depending on its intrinsic excitability, that produces a rhythmogenic state of maximum stability (stabilitymax). Consequently, in some slices, increasing aCSF [K+] drives the network rhythm toward stabilitymax, making the rhythm less irregular, whereas in others, increasing aCSF [K+] elevates excitability beyond stabilitymax, making the rhythm more irregular. To test this hypothesis further, we evaluated the stability of the inspiratory rhythm (Eqs. 1, 2) as aCSF [K+] was incrementally raised from 3 to 14 mm (Fig. 2C). The level of aCSF [K+] required for the preBötC to produce the most stable rhythm varied across individual slices and was unpredictable (Fig. 2B). However, consistent with our hypothesis, when aligned by stabilitymax (level of extracellular K+ that produced the highest stability value), changes in stability in response to changes in aCSF [K+] were predictable, following a positive-skew-type bell curve (Fig. 2C). Along this curve, increasing [K+] initially resulted in an increase in rhythm stability from 5 ± 4% to 30 ± 9% stabilitymax. After stabilitymax was reached, further 2 mm stepwise increases in [K+] decreased stability by −40 ± 7%, −55 ± 7%, −52 ± 9%, and −71 ± 9% (%stabilitymax; Fig. 2C). Thus, these results suggest that perturbations to network activity have highly variable effects on rhythmogenesis depending on whether the network state is underexcited or overexcited relative to stabilitymax.

Figure 2.

Peak stability occurs at variable levels of network excitability. A, The level of aCSF [K+] needed to elicit bursting within the preBötC is variable among slices. Forty-eight percent of slices required 8 mm [K+] to elicit network-wide bursting, whereas 17% required 6.5 mm, 10% required 5 mm, and 24% required 3 mm. B, Representative tracings from preBötC population recordings following stepwise increases in aCSF [K+] from 3 to 8 mm. Top, Tracing shows a rhythm that increases stability as aCSF [K+] is increased. Middle, Tracing shows a rhythm that increases and then decreasing stability in response to increased aCSF [K+]. Bottom, Tracing shows a rhythm that is destabilized by increasing aCSF [K+]. The point of maximum stability (stabilitymax) is noted for each example. C, Following alignment of stabilitymax for each rhythm, levels of aCSF [K+] before reaching peak stability show lower rhythm stability, whereas increases in aCSF [K+] beyond stabilitymax result in decreasing rhythm stability. Averaging across slices results in a stability curve, where increasing aCSF [K+] initially increases rhythm stability followed by a decrease in stability as aCSF [K+] is further increased.

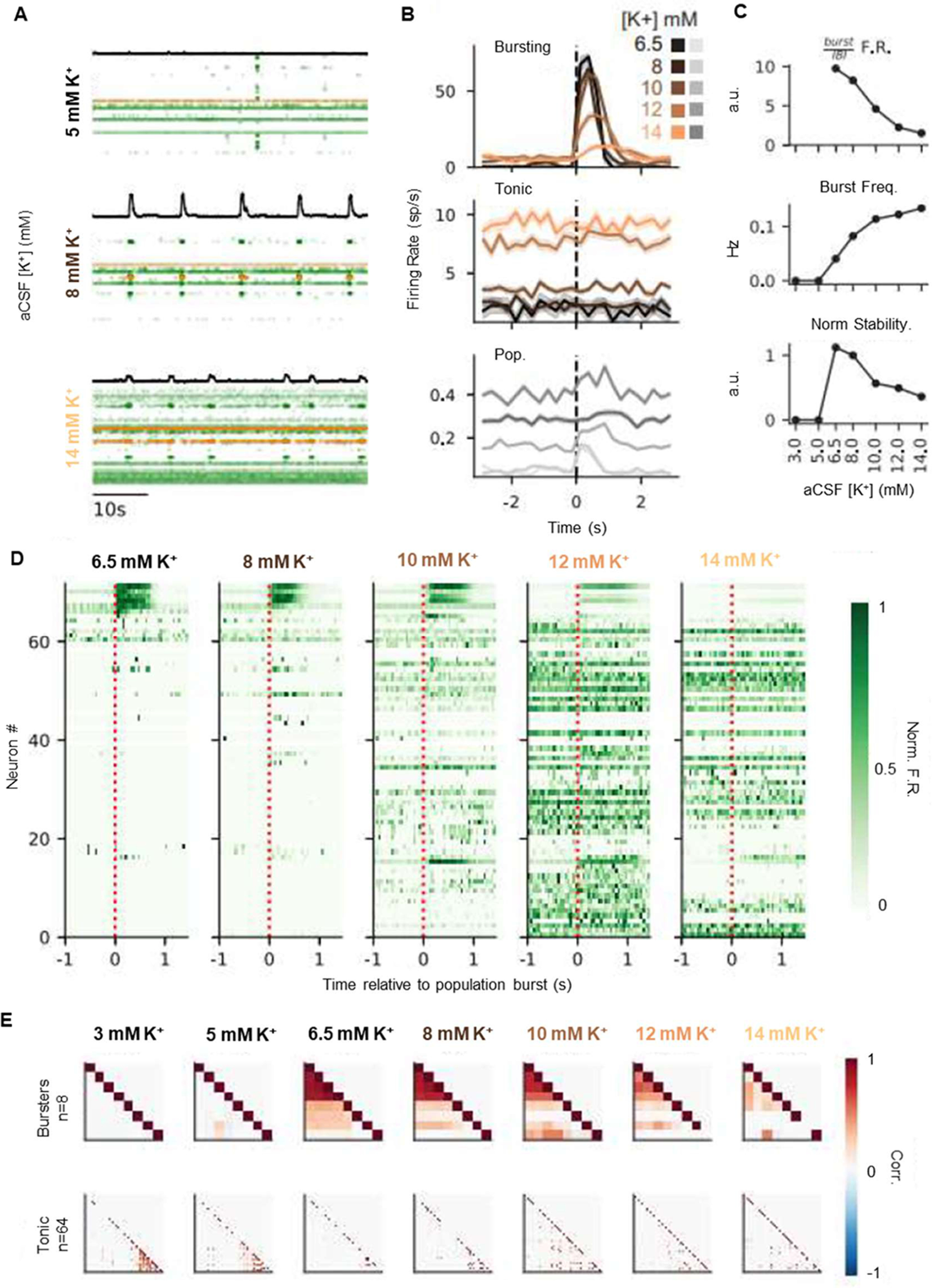

To assess the extracellular spiking activity of single neurons as the population rhythm emerges, stabilizes, and destabilizes, we simultaneously recorded with high-density Neuropixels probes between 33 and 72 single units in three slices (n = 138 neurons total) as we increased the aCSF [K+] from 3 mm to 14 mm (Fig. 3). This allowed us to investigate the dynamics of the neural population with single neuron resolution. As expected (Fig. 2), we found that as [K+] was increased, stability increased initially and then decreased (Fig. 3C). Raster plots from a recording of 72 simultaneously recorded neurons are shown in Figure 3A for 5 mm, 8 mm, and 14 mm aCSF [K+]. Neurons recorded included both burst-modulated neurons (bursting), and neurons that fire tonically throughout the burst cycle (tonic; Fig. 3B). We found that, as [K+] increased and stability decreased (Fig. 3C), spiking activity became less concentrated during the burst phase of the rhythm (Fig. 3B,C,D). Bursting neurons fired less robustly with a decrease in the number of action potentials throughout the burst, whereas tonic neurons became more active across all phases of the rhythm (Fig. 3B,D). To examine how temporal synchrony among neurons evolves as the rhythm emerges and destabilizes in response to increasing network excitability, we computed pairwise correlations between all bursting and tonic neurons (Fig. 3E). Bursting neurons exhibited a peak in temporal correlations that corresponded to stabilitymax ([K+] = 6.5 mm; Fig. 3). As aCSF [K+] was elevated further and the rhythm destabilized, bursting neurons became less correlated, consistent with a decrease in synchrony among bursting neurons. Interestingly, a subpopulation of tonic neurons exhibited high correlations before the emergence of population bursting. However, these correlations decreased as [K+] increased, despite higher overall firing rates of these neurons. Together, our results demonstrate that burst stability is characterized by high-frequency spiking and correlation among bursting neurons, and reduced stability at high aCSF [K+] is concomitant with derecruitment of burst-related neurons and higher levels of decorrelated activity among the tonic population.

Figure 3.

Changes in rhythm stability are associated with a trade-off between bursting and tonic spiking activity. A, Rasters of 72 simultaneously recorded single units at 5, 8, and 14 mm [K+]. Black trace is integrated contralateral population recording. Each row is a single neuron, and each dot is a recorded spike. Rows are ordered by recording depth. Cells highlighted in orange represent the tonic and bursting cell examples in B. B, Burst aligned spiking at each K+ concentration for a bursting (top) and tonic (middle) neuron (highlighted in A). Traces are average spikes/s over 10 min recordings for each K+ level, binned at 250 ms. Pooled spiking activity across all neurons is shown (bottom) in gray, where y-axis is spikes/s/neuron. Shaded regions are ± SE. Burst spiking decreases and tonic spiking increases as K+ increases; = (9,25,39,45,40) for K+ = (6.5,8,10,12,14) mm. C, Top, Ratio of burst firing rate (500 ms after burst onset) to interburst firing rate (1 s before burst onset) pooled across all neurons, as a function of K+. Middle, Burst frequency increases, and burst stability decreases (bottom) as [K+] increases. D, Burst aligned peristimulus time histograms of spike rate for each recorded neuron (rows), at each K+ concentration. Neurons are ordered by decreasing burst-related firing rate as observed at K+ = 6.5 mm. Spike rates are normalized by the maximal firing rate of each neuron. E, Top, Pairwise correlations between bursting and tonic (bottom) neurons for each K+ level. Neurons are clustered by Ward linkage at 6.5 mm K+ (bursters) or 3 mm (tonic).

Rhythmogenic state relative to stabilitymax predicts susceptibility to OIRD

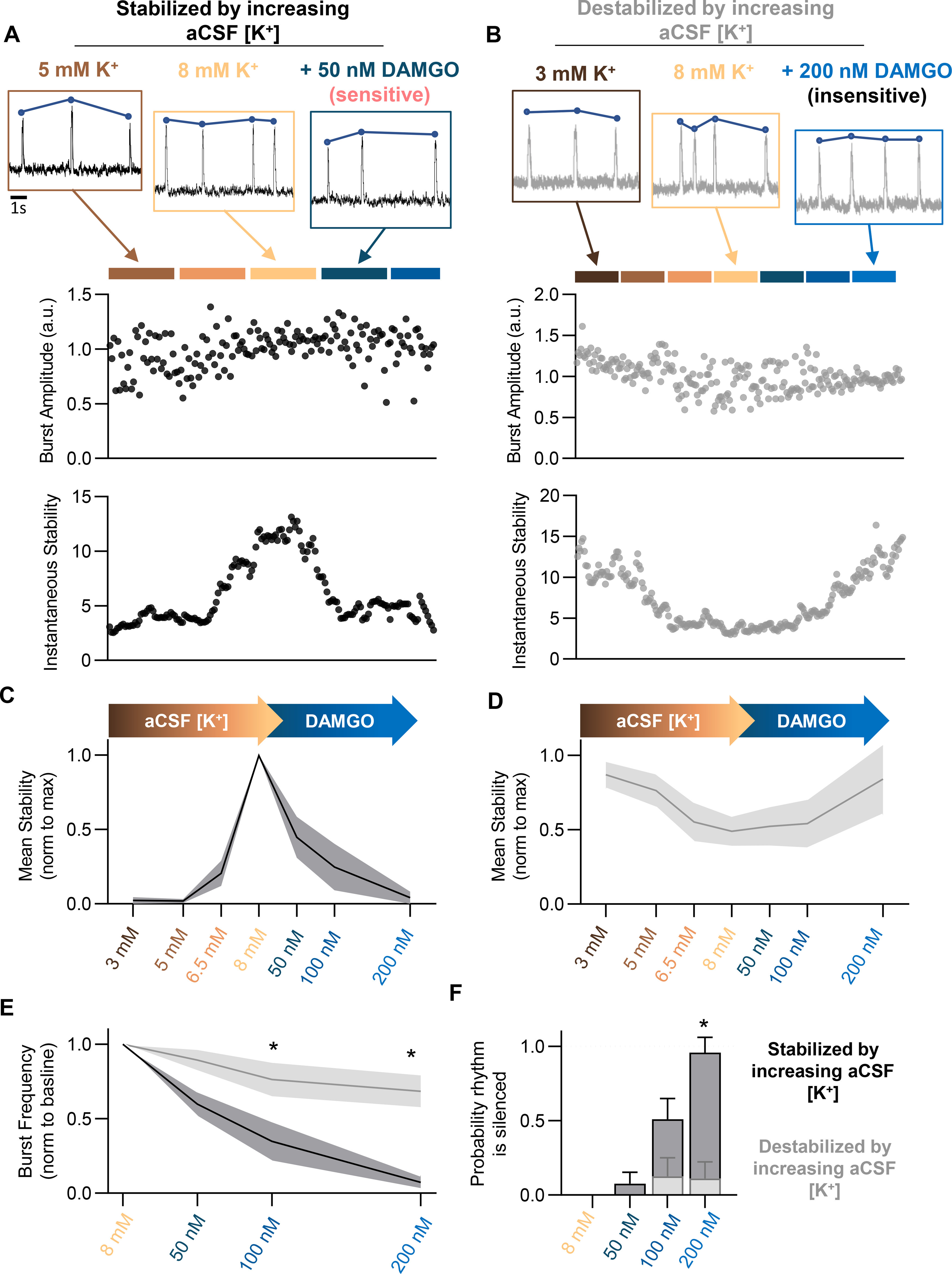

Next, we tested whether the trajectory of network stability in response to changing excitability could predict the response of the inspiratory network to opioids. Inspiratory rhythms were recorded from horizontal slices while aCSF [K+] was increased from 3 to 8 mm followed by application of 50–200 nm DAMGO. Inspiratory rhythms that became stabler in response to increasing aCSF [K+] and were near or below stabilitymax in 8 mm [K+] (n = 13/22) were highly responsive to DAMGO, which decreased rhythm stability (−96 ± 5%), and silenced (n = 11/13), or nearly silenced (n = 2/13), rhythmic activity at a concentration of 200 nm (−93 ± 12% change in burst frequency; Fig. 4A,C,E,F). In contrast, inspiratory rhythms that reached stabilitymax at aCSF [K+] lower than 8 mm and started to become destabilized in 8 mm [K+] (Fig. 4B,D) showed minimal changes in burst frequency following DAMGO application (n = 9/22; Fig. 4E,F). Among these rhythms, inspiratory burst frequency was only modestly suppressed (−32 ± 11% in 200 nm DAMGO), and none were silenced (n = 0/9; Fig. 4E,F). Importantly, in these unresponsive rhythms, DAMGO increased the stability of the rhythm (+72 ± 24% in 200 nm DAMGO; Fig. 4B,D), suggesting that DAMGO drove the network toward stabilitymax, making the rhythm more robust rather than causing a dissociation of network activity.

Figure 4.

PreBötC excitability relative to stabilitymax predicts DAMGO sensitivity. Stability of preBötC bursting was assessed while increasing aCSF [K+] from 3 to 8 mm, followed by DAMGO application. A–F, Representative recordings and quantified peak amplitude and stability over the course of aCSF [K+] and DAMGO administration. Rhythms that increased stability with increasing aCSF [K+] (A, C; N = 13) exhibited significantly greater susceptibility to OIRD (E, F) compared with rhythms that decreased stability with increasing aCSF [K+] (B, D; N = 9). Rhythms that increased stability with increasing aCSF [K+] became destabilized following DAMGO application (A, C), whereas rhythms decreasing stability with increasing aCSF [K+] became stabilized following DAMGO (B, D); *p < 0.05. Differences in the effect of DAMGO between preBötC networks that increased versus decreased rhythm stability during increasing aCSF [K+] were assessed with a repeated-measures mixed-effect analysis with Sidak's multiple comparisons.

Attenuation of INaP destabilizes the inspiratory rhythm and increases susceptibility to OIRD

As indicated by our Neuropixels recordings, increased stability was associated with increased spiking during bursts and increased correlation among bursting neurons. The persistent INaP is well known to promote bursting among respiratory neurons (Ramirez et al., 2004), and computational models predict that the robustness of the preBötC network is related to the proportion of cells within the rhythmogenic network that exhibit INaP-dependent bursting (Purvis et al., 2007). Therefore, we hypothesized that attenuation of INaP would destabilize network activity and render the rhythm more responsive to DAMGO. To test this, we bath applied INaP blockers to horizontal brainstem slices in 8 mm [K+] aCSF, before increasing doses of DAMGO from 50 to 200 nm. Following bath application of 4,9-Anhydrotetrodotoxin (ATTX; 400 nm), a specific blocker of voltage-gated Na+ currents carried by the NaV1.6 channel (Ptak et al., 2005), the stability of rhythmic bursting decreased by −65 ± 9% (p = 0.04, t = 2.6, n = 7, df = 6; Fig. 5 A,B,C,D), with the greatest effect on burst amplitude irregularity (Fig. 5C). NaV1.6 is not the only carrier of an INaP current; however, the activation threshold for NaV1.6 is much lower compared with other NaV channels. Thus, it likely plays a prominent role in carrying a persistent Na+ current within the network. We also used riluzole, a less specific but more commonly used blocker of INaP-dependent bursting within the preBötC (Del Negro et al., 2002; Ptak et al., 2005; Viemari and Ramirez, 2006). Bath-applied riluzole (20 μm) resulted in a 20 ± 13% decrease in stability (p = 0.03, t = 3.8, n = 4, df = 3; Fig. 5A,D), with the most pronounced effect on burst frequency irregularity (Fig. 5C) with less of an effect on burst amplitude irregularity. The reason for the differential effects of ATTX and riluzole on amplitude and frequency is unknown, however differences in pharmacological specificity may contribute. In addition to destabilizing the rhythm, application of either ATTX or riluzole significantly increased the susceptibility of all slices to respiratory depression induced by DAMGO. In the presence of ATTX or riluzole, DAMGO had a significantly greater suppressive effect on inspiratory frequency compared with controls (p = 0.007, F = 7.0 and p = 0.001; F = 5.0 for ATTX (n = 7) and riluzole (n = 4), respectively; Fig. 5E) and a higher proportion of rhythms were silenced completely (Fig. 5F). These results suggest that the activity INaP within the preBötC promotes stable rhythmic bursting, which protects against the depressant effects from DAMGO.

Figure 5.

INaP attenuation destabilizes the inspiratory rhythm and increases the severity of OIRD. A, Representative population recordings before and after bath application of the NaV1.6 inhibitor, ATTX, or riluzole, followed by subsequent bath application of DAMGO. B, Representative quantified rhythm stability following bath application of ATTX. C, Peak amplitude and frequency Poincaré plots demonstrating increases in amplitude and frequency irregularity following ATTX (400 nm) or riluzole (20 μm) application, respectively. D, Mean (left) and individual (right) changes in rhythm stability following application of ATTX (red) or riluzole (blue). E, Mean burst frequency responses to stepwise increases in [DAMGO] following control conditions (gray) or pretreatment with either 400 nm ATTX (top, red) or 20 μm riluzole (bottom, blue). Brainstem slices pretreated with ATTX or riluzole displayed greater depression in burst frequency following DAMGO application, compared with control values. F, Probability that the inspiratory burst rhythm was silenced following stepwise increases in [DAMGO] during control conditions (gray), or following pretreatment with 400 nm ATTX (top, red) or 20 μm riluzole (bottom, blue); *p < 0.05, significantly different from mean control values. Differences in stability assessed with paired two-tailed t test. Differences in DAMGO sensitivity between control and pretreated conditions assessed as two-way repeated-measures ANOVA with Sidak's multiple comparisons test (condition and [DAMGO] as factors).

Potentiation of INaP reduces the susceptibility to OIRD

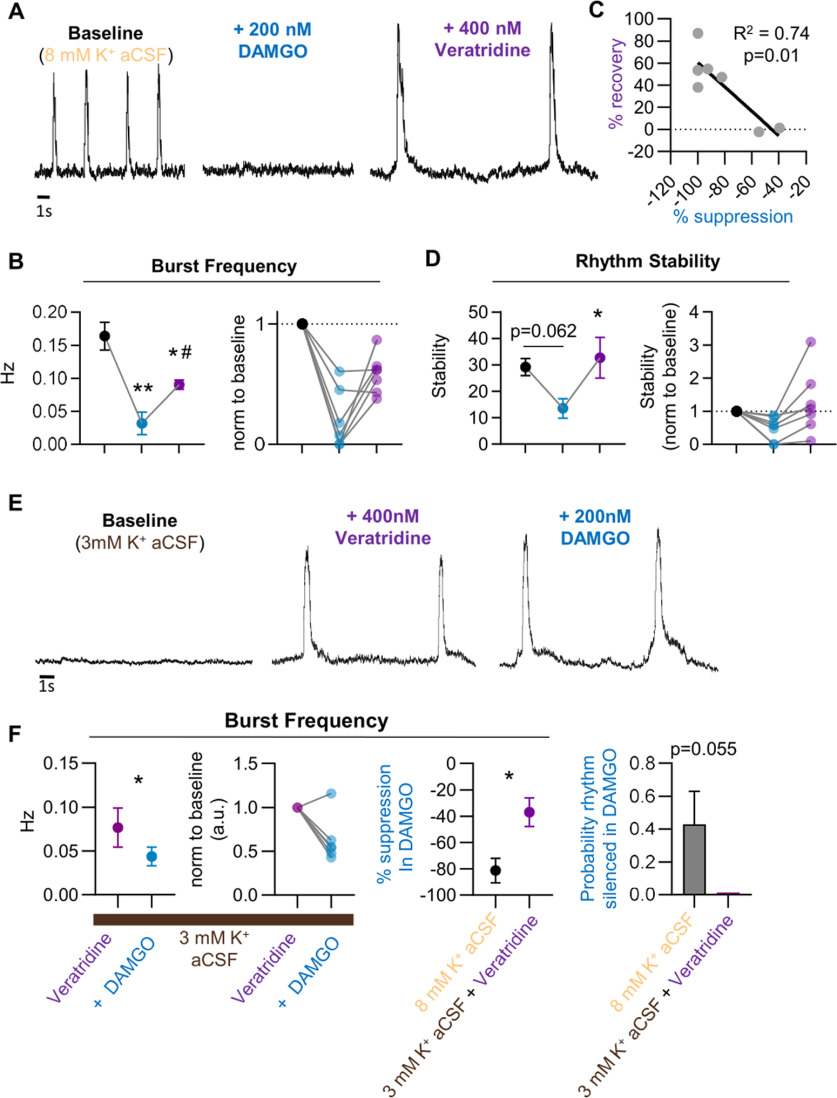

Our finding that the respiratory consequences of DAMGO are exaggerated following attenuation of INaP suggests that this neuronal property plays a protective role against OIRD. Thus, we next assessed whether potentiating INaP within brainstem slices could prevent or reverse OIRD by bath applying veratridine (400 nm), which slows the inactivation voltage-dependent Na+ channels, before or after application of 200 nm DAMGO. Following DAMGO application in the absence of veratridine, burst frequency was suppressed by −81 ± 10% (p < 0.001, F = 26.5 n = 7, df = 6; Fig. 6A,B). However, veratridine application partially recovered the inspiratory rhythm, and burst frequency returned to 59 ± 6% of control (Fig. 6A,B). Recovered rhythms following veratridine application tended to display large amplitude and area burst characteristics, consistent with preventing Na+ channel inactivation (Fig. 6A). Notably, there was a linear correlation between the magnitude of DAMGO suppression and the ability of veratridine to reverse OIRD; rhythms with the greatest suppression of burst frequency in DAMGO showed the greatest recovery following veratridine application (p = 0.01, R2 = 0.74, n = 7, df = 6; Fig. 6C). Following DAMGO suppression, the rhythms displayed a decrease in stability (p = 0.06, t = 3.2, n = 7, df = 6). However, veratridine application increased rhythm stability which coincided with partial recovery of the bursting (Fig. 6D; p = 0.04, t = 3.4, n = 7, df = 6).

Figure 6.

Slowing Na+ channel inactivation can protect against and partially reverse OIRD. A, Representative preBötC population recording demonstrating cessation of bursting following 200 nm DAMGO application and partial recovery with Veratridine (400 nm). B, Mean burst frequency (left) and individual replicates (right) following bath application of 200 nm DAMGO and subsequent application of 400 nm Veratridine. C, Linear regression analysis shows a correlation between burst frequency recovery with veratridine and the magnitude of frequency suppression following 200 nm DAMGO. D, Following DAMGO administration, suppression of bursting coincided with reduced stability of the rhythm (p = 0.06). Four hundred micromolars Veratridine partially recovered the rhythm and resulted in an increase in rhythm stability (p < 0.05). E, Application of 400 nm Veratridine in 3 mm [K+] aCSF elicits rhythmic bursting from the preBötC that is significantly less sensitive to suppression by 200 nm DAMGO. F, Population burst frequency decreases following 200 nm DAMGO in the presence of 400 nm Veratridine; however, the magnitude of suppression is significantly less compared with frequency suppression following 200 nm DAMGO in control conditions with 8 mm [K+] aCSF; *p < 0.05, significantly different from control; #p < 0.05, significantly different from 200 nm [DAMGO]. Differences in burst frequency and stability (B, D) assessed as one-way repeated-measures ANOVA with Sidak's multiple comparisons test. F, Differences in burst frequency following DAMGO in control and Veratridine pretreated conditions assessed as unpaired two-tailed t test.

To amplify INaP-dependent bursting and test for a protective role in OIRD, 400 nm veratridine was applied in 3 mm [K+] aCSF before DAMGO administration. Veratridine application resulted in stimulation of bursting with the production of large amplitude and area bursts, similar to bursts recorded following veratridine-induced recovery from OIRD (Fig. 6D). Subsequent bath application of 200 nm DAMGO resulted in a reduction of burst frequency. However, importantly, this reduction was significantly less compared with control conditions in 8 mm [K+] (only −37 + 11% vs −81 + 10%, p = 0.04, t = 2.6, n = 7, df = 6; Fig. 6E). Further, in the presence of veratridine no rhythms were silenced by DAMGO (Fig. 6E). Collectively, these results support a protective role of INaP-dependent bursting against OIRD.

Discussion

Variation in the susceptibility to OIRD greatly enhances the risk of an opioid overdose and has been a major contributor to the current opioid crisis. Our study provides a mechanistic framework for understanding this unpredictability. Although it is well established that the preBötC is critical for breathing (Smith et al., 1991; Ramirez et al., 1998; Wenninger et al., 2004) and produces a rhythm that is intrinsically responsive to opioids, exhibiting a dose-dependent frequency decrease on average (Mellen et al., 2003; Sun et al., 2019; Wei and Ramirez, 2019), we demonstrate that the network response to opioids varies. Indeed, we find that the preBötC network in vitro exhibits remarkable variability in opioid responsiveness (Fig. 1C), a property often overlooked. This variability is reminiscent of the variability observed clinically and is the source of considerable confusion in numerous animal studies in vivo (Dahan et al., 2005; Lewanowitsch et al., 2006; Ren et al., 2006, 2015; Levran et al., 2013; Langer et al., 2017a,b; Wei and Ramirez, 2019). Our results not only provide a conceptual explanation for the variation in the susceptibility to OIRD but also provide insights into the underlying mechanisms. Targeting these cellular mechanisms may open new therapeutic avenues for treating OIRD.

The preBötC comprises an estimated ∼800–1000 sparsely connected glutamatergic neurons representing the minimal circuitry necessary to produce the inspiratory rhythm (Smith et al., 1991; Feldman et al., 2013; Del Negro et al., 2018). Rhythm emerges within this circuit through excitatory synaptic interactions and intrinsic membrane properties that control synchrony and stability in the network (Purvis et al., 2007; Phillips and Rubin, 2019). Individual preBötC neurons express varied amounts of the bursting currents ICAN and INaP (Thoby-Brisson and Ramirez, 2000, 2001; Tryba et al., 2003, 2008; Peña et al., 2004; Peña and Ramirez, 2004; Del Negro et al., 2005). In some neurons that express high densities of these currents, bursting can continue intrinsically in the absence of synaptic interactions (autorhythmic bursting neurons). In many other neurons, excitatory synaptic inputs are important for the activation of these bursting currents. This contribution of synaptic mechanisms to rhythmogenesis, called the group-pacemaker hypothesis, posits that spiking activity among highly interconnected excitatory neurons cause a buildup of excitation that culminates in a subsequent population burst (Rekling and Feldman, 1998; Rekling et al., 2000; Del Negro and Hayes, 2008). This network-based mechanism is dependent on spiking activity between preBötC bursts, and in some cases, the dynamics of these excitatory synaptic interactions may be sufficient to drive rhythmogenesis in the absence of intrinsic bursting properties (Rubin et al., 2009). However, in the functional preBötC network these intrinsic- and network-based mechanisms are intimately intertwined, and rhythmogenesis depends on both intrinsic bursting properties and excitatory synaptic activity in the network (Ramirez and Baertsch, 2018b).

Importantly, these mechanisms are dynamic, and different neuromodulatory and metabolic conditions, such as hypoxia, can bias rhythmogenesis toward intrinsic- or network-based mechanisms (Peña et al., 2004; Peña and Ramirez, 2004; Baertsch and Ramirez, 2019). Activity patterns within the network, however, do not seem to segregate into two distinct states. Indeed, we find that the preBötC generates a robust, stable rhythm within a narrow unimodal excitability window because rhythmogenesis becomes unstable if excitability is too low or too high. In contrast to the activity of single neurons that can transition from distinct quiescent to bursting to tonic phenotypes depending on their persistent sodium conductance (gNaP) and membrane potential (VM; Phillips and Rubin, 2019), the rhythmogenic state of the network is determined by the constellation of activity phenotypes at any given time and operates along a spectrum of states as the ratios of quiescent, bursting, and tonic neurons change. As suggested by our data, the constellation of neuronal firing phenotypes and corresponding network stability (Fig. 3) can be dynamically modulated by the amount of general network excitation and INaP-dependent bursting (Purvis et al., 2007; Rybak et al., 2014; Phillips and Rubin, 2019). Indeed, our multiunit recordings indicate that the profile of neuronal spiking within the preBötC changes throughout different levels of network excitation and network stability, leading to the important conclusion that the preBötC network can shift states while maintaining rhythmogenesis.

In vitro, some preBötC slices produce bursting at low levels of excitability (3 mm [K+] aCSF), whereas other slices require excitability to be higher (8 mm [K+] aCSF; Fig. 2; Tryba et al., 2003; Ruangkittisakul et al., 2008). The mechanisms that determine which slices are capable of producing bursting under conditions of low extrinsic excitability are largely unknown. Many factors may contribute, including the precise anatomic plane where the slice is cut (Ruangkittisakul et al., 2008), slice thickness, sparsity of synaptic connectivity within the network (Carroll et al., 2013; Carroll and Ramirez, 2013), the extent of the respiratory network preserved in the preparation, and neuromodulatory state (Doi and Ramirez, 2008). Studies modeling the preBötC in silico have demonstrated that the number of INaP-dependent autorhythmic neurons within the network regulates the robustness of bursting from the preBötC, which may influence the level of network excitability required to initiate population-wide bursting (Purvis et al., 2007). For example, increasing the proportion of autorhythmic neurons within the network increases the input and output ranges of bursting from the network (Purvis et al., 2007). Because INaP is regulated by neuromodulation (Peña et al., 2004; Tryba and Ramirez, 2004), differences in the endogenous neuromodulatory state may explain, at least in part, why some slices burst in low extracellular [K+], whereas other require higher [K+].

As excitability increases in the preBötC, activity phenotypes of individual neurons change, modulating the stability of the emergent network rhythm (Fig. 3). This is likely true for both excitatory and inhibitory neurons within the network; however, discerning the different responses among these neurons requires further study. Nonetheless, the stability of the rhythm reaches a maximum when the network is composed of an optimal balance of activity phenotypes. As shown by our Neuropixels recordings, maximum stability is associated with increased spike frequencies during bursts and higher correlations among bursting neurons (Fig. 3). If excitability continues to increase, tonic activity within the network begins to dominate, destabilizing the rhythm. Thus, within any given slice preparation, changes in excitability (e.g., via aCSF [K+]) cause a bell-shaped response in rhythm stability (Fig. 2C). Determining where on this stability curve rhythmogenesis occurs is important for predicting how an individual network will respond when network excitability is perturbed. Integrating these in vitro findings with in vivo models will be important to fully understand the relationships among breathing pattern, the rhythmogenic state of the respiratory network, and the response to OIRD. For example, respiratory networks in vivo receive multiple neuromodulatory inputs from regions throughout the CNS such as the pontine respiratory group (Yang and Feldman, 2018), which may also regulate the state of the respiratory rhythm generating network and alter the likelihood of OIRD, for example, through changes in excitatory input.

Furthermore, our unexpected finding that opioids can stabilize inspiratory bursts in vitro in some rhythmogenic states may point to a role for endogenous μ-opioid receptor signaling in the preBötC. Whether this stabilizing effect exists in vivo is unknown. However, under natural conditions endorphins are presumably released when the organism and the respiratory network is in a heightened excitatory state. Based on our findings in vitro, we speculate that under such conditions, in addition to reducing the sensation of pain, the release of endorphins may also stabilize breathing. In this context, expression of μ-opioid receptors on neurons critical for breathing may be evolutionarily advantageous. This may also provide a mechanistic basis for why opioids are beneficial if given for the treatment of dyspnea or panic attacks (Muers, 2002; Gallagher, 2011). In contrast, in most clinical situations, opioids are given exogenously, independent of the network state. Indeed, in the context of obstructive sleep apnea (Nagappa et al., 2017; Cozowicz et al., 2018), the presence of contraindicated drugs such as benzodiazepines (Boon et al., 2020), and during anesthesia (Gupta et al., 2018), opioids may be more likely to destabilize or stop breathing because the respiratory network is in a state of reduced excitability. Accordingly, treatments that promote the respiratory network to shift rightward along the stability curve may confer a state of rhythmogenesis that is less susceptible to OIRD. Increasing the contribution of INaP within the respiratory network may be one such mechanism. Indeed, we find this dynamic network property is critical for regulating the functional consequences of opioids as amplifying or inhibiting INaP-dependent bursting mechanisms enhances or decreases the severity of OIRD, respectively (Figs. 5, 6). However, modulation of INaP is likely one of many mechanisms that plays a role in regulating the rhythmogenic state of the respiratory network. Thus, further research aimed at understanding such mechanisms will be an important next step to better predict and prevent OIRD.

In summary, variation in the susceptibility to OIRD within and among individuals greatly increases the risk of opioid use, with no dose being considered safe. To mitigate these risks, it will be important to develop strategies to protect respiratory rhythmogenesis from the effects of opioids. Our experiments in vitro indicate that the susceptibility to OIRD is not a static property but is determined by the state of the respiratory rhythm generating network. The milieu of factors determining the basal state of rhythmogenesis, and consequent opioid response will require future studies to be fully understood. However, the evidence provided here suggests that the activity of INaP and the level of network excitability play important roles. Further investigations of these factors are regulated, and whether other critical networks exhibit similar state dependencies will be key to better predict why and when some individuals are at high risk for OIRD.

Footnotes

This work was supported by National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute Grants HL-126523 (J.M.R.), HL-144801 (J.M.R.), HL-090554 (J.M.R.), HL-145004 (N.A.B.), and HL154558-01 (N.J.B.).

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

References

- Bachmutsky I, Wei XP, Kish E, Yackle K (2020) Opioids depress breathing through two small brainstem sites. Elife 9:e52694. 10.7554/eLife.52694 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baekey DM, Morris KF, Nuding SC, Segers LS, Lindsey BG, Shannon R (2004) Ventrolateral medullary respiratory network participation in the expiration reflex in the cat. J Appl Physiol (1985) 96:2057–2072. 10.1152/japplphysiol.00778.2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baertsch NA, Ramirez JM (2019) Insights into the dynamic control of breathing revealed through cell-type-specific responses to substance P. Elife 8:e51350. 10.7554/eLife.51350 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baertsch NA, Severs LJ, Anderson TM, Ramirez JM (2019) A spatially dynamic network underlies the generation of inspiratory behaviors. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 116:7493–7502. 10.1073/pnas.1900523116 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ballanyi K, Lalley PM, Hoch B, Richter DW (1997) cAMP-dependent reversal of opioid- and prostaglandin-mediated depression of the isolated respiratory network in newborn rats. J Physiol 504:127–134. 10.1111/j.1469-7793.1997.127bf.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boon M, van Dorp E, Broens S, Overdyk F (2020) Combining opioids and benzodiazepines: effects on mortality and severe adverse respiratory events. Ann Palliat Med 9:542–557. 10.21037/apm.2019.12.09 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carroll MS, Ramirez JM (2013) Cycle-by-cycle assembly of respiratory network activity is dynamic and stochastic. J Neurophysiol 109:296–305. 10.1152/jn.00830.2011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carroll MS, Viemari JC, Ramirez JM (2013) Patterns of inspiratory phase-dependent activity in the in vitro respiratory network. J Neurophysiol 109:285–295. 10.1152/jn.00619.2012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cherny N, Ripamonti C, Pereira J, Davis C, Fallon M, McQuay H, Mercadante S, Pasternak G, Ventafridda V (2001) Strategies to manage the adverse effects of oral morphine: an evidence-based report. J Clin Oncol 19:2542–2554. 10.1200/JCO.2001.19.9.2542 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cozowicz C, Chung F, Doufas AG, Nagappa M, Memtsoudis SG (2018) Opioids for acute pain management in patients with obstructive sleep apnea: a systematic review. Anesth Analg 127:988–1001. 10.1213/ANE.0000000000003549 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cutts CS, Eglen SJ (2014) Detecting pairwise correlations in spike trains: an objective comparison of methods and application to the study of retinal waves. J Neurosci 34:14288–14303. 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2767-14.2014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dahan A, Overdyk F, Smith T, Aarts L, Niesters M (2013) Pharmacovigilance: a review of opioid-induced respiratory depression in chronic pain patients. Pain Physician 16:E85–94. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dahan A, Yassen A, Bijl H, Romberg R, Sarton E, Teppema L, Olofsen E, Danhof M (2005) Comparison of the respiratory effects of intravenous buprenorphine and fentanyl in humans and rats. Br J Anaesth 94:825–834. 10.1093/bja/aei145 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Del Negro CA, Funk GD, Feldman JL (2018) Breathing matters. Nat Rev Neurosci 19:351–367. 10.1038/s41583-018-0003-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Del Negro CA, Hayes JA (2008) A “group pacemaker” mechanism for respiratory rhythm generation. J Physiol 586:2245–2246. 10.1113/jphysiol.2008.153627 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Del Negro CA, Kam K, Hayes JA, Feldman JL (2009) Asymmetric control of inspiratory and expiratory phases by excitability in the respiratory network of neonatal mice in vitro. J Physiol 587:1217–1231. 10.1113/jphysiol.2008.164079 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Del Negro CA, Morgado-Valle C, Feldman JL (2002) Respiratory rhythm: an emergent network property? Neuron 34:821–830. 10.1016/S0896-6273(02)00712-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Del Negro CA, Morgado-Valle C, Hayes JA, Mackay DD, Pace RW, Crowder EA, Feldman JL (2005) Sodium and calcium current-mediated pacemaker neurons and respiratory rhythm generation. J Neurosci 25:446–453. 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2237-04.2005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Del Negro CA, Pace RW, Hayes JA (2008) What role do pacemakers play in the generation of respiratory rhythm? Adv Exp Med Biol 605:88–93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Doi A, Ramirez J-M (2008) Neuromodulation and the orchestration of the respiratory rhythm. Respir Physiol Neurobiol 164:96–104. 10.1016/j.resp.2008.06.007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dowell D, Kunins HV, Farley TA (2013) Opioid analgesics–risky drugs, not risky patients. JAMA 309:2219–2220. 10.1001/jama.2013.5794 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feldman JL, Del Negro CA, Gray PA (2013) Understanding the rhythm of breathing: so near, yet so far. Annu Rev Physiol 75:423–452. 10.1146/annurev-physiol-040510-130049 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fleming E, Voscopoulos C, George E (2015) Non-invasive respiratory volume monitoring identifies opioid-induced respiratory depression in an orthopedic surgery patient with diagnosed obstructive sleep apnea: a case report. J Med Case Rep 9:94. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gallagher R (2011) The use of opioids for dyspnea in advanced disease. CMAJ 183:1170. 10.1503/cmaj110024 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gray PA, Janczewski WA, Mellen N, McCrimmon DR, Feldman JL (2001) Normal breathing requires preBötzinger complex neurokinin-1 receptor-expressing neurons. Nat Neurosci 4:927–930. 10.1038/nn0901-927 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gruhzit CC (1957) Chemoreflex activity of dextromethorphan (romilar), dextrorphan, codeine and morphine in the cat and the dog. J Pharmacol Exp Ther 120:399–407. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gupta K, Prasad A, Nagappa M, Wong J, Abrahamyan L, Chung FF (2018) Risk factors for opioid-induced respiratory depression and failure to rescue: a review. Curr Opin Anaesthesiol 31:110–119. 10.1097/ACO.0000000000000541 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hurlé MA, Mediavilla A, Flórez J (1982) Morphine, pentobarbital and naloxone in the ventral medullary chemosensitive areas: differential respiratory and cardiovascular effects. J Pharmacol Exp Ther 220:642–647. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hurlé MA, Mediavilla A, Flórez J (1983) Participation of pontine structures in the respiratory action of opioids. Life Sci 33 Suppl 1:571–574. 10.1016/0024-3205(83)90567-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jun JJ, Steinmetz NA, Siegle JH, Denman DJ, Bauza M, Barbarits B, Lee AK, Anastassiou CA, Andrei A, Aydın Ç, Barbic M, Blanche TJ, Bonin V, Couto J, Dutta B, Gratiy SL, Gutnisky DA, Häusser M, Karsh B, Ledochowitsch P, et al. (2017) Fully integrated silicon probes for high-density recording of neural activity. Nature 551:232–236. 10.1038/nature24636 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kam K, Worrell JW, Ventalon C, Emiliani V, Feldman JL (2013) Emergence of population bursts from simultaneous activation of small subsets of preBötzinger complex inspiratory neurons. J Neurosci 33:3332–3338. 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4574-12.2013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keifer JC, Baghdoyan HA, Lydic R (1992) Sleep disruption and increased apneas after pontine microinjection of morphine. Anesthesiology 77:973–982. 10.1097/00000542-199211000-00021 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuehn BM (2007) Opioid prescriptions soar: increase in legitimate use as well as abuse. JAMA 297:249–251. 10.1001/jama.297.3.249 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lalley PM, Pilowsky PM, Forster HV, Zuperku EJ (2014) CrossTalk opposing view: the pre-Botzinger complex is not essential for respiratory depression following systemic administration of opioid analgesics. J Physiol 592:1163–1166. 10.1113/jphysiol.2013.258830 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Langer TM, Neumueller SE, Crumley E, Burgraff NJ, Talwar S, Hodges MR, Pan L, Forster HV (2017a) Effects on breathing of agonists to μ-opioid or GABA. Respir Physiol Neurobiol 239:10–25. 10.1016/j.resp.2017.01.007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Langer TM, Neumueller SE, Crumley E, Burgraff NJ, Talwar S, Hodges MR, Pan L, Forster HV (2017b) Ventilation and neurochemical changes during µ-opioid receptor activation or blockade of excitatory receptors in the hypoglossal motor nucleus of goats. J Appl Physiol (1985) 123:1532–1544. 10.1152/japplphysiol.00592.2017 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levitt ES, Abdala AP, Paton JF, Bissonnette JM, Williams JT (2015) μ opioid receptor activation hyperpolarizes respiratory-controlling Kölliker-Fuse neurons and suppresses post-inspiratory drive. J Physiol 593:4453–4469. 10.1113/JP270822 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levran O, Peles E, Randesi M, Shu X, Ott J, Shen P-H, Adelson M, Kreek MJ (2013) Association of genetic variation in pharmacodynamic factors with methadone dose required for effective treatment of opioid addiction. Pharmacogenomics 14:755–768. 10.2217/pgs.13.58 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lewanowitsch T, Miller JH, Irvine RJ (2006) Reversal of morphine, methadone and heroin induced effects in mice by naloxone methiodide. Life Sci 78:682–688. 10.1016/j.lfs.2005.05.062 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McQuay H (1999) Opioids in pain management. Lancet 353:2229–2232. 10.1016/S0140-6736(99)03528-X [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mellen NM, Janczewski WA, Bocchiaro CM, Feldman JL (2003) Opioid-induced quantal slowing reveals dual networks for respiratory rhythm generation. Neuron 37:821–826. 10.1016/S0896-6273(03)00092-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Montandon G, Qin W, Liu H, Ren J, Greer JJ, Horner RL (2011) PreBotzinger complex neurokinin-1 receptor-expressing neurons mediate opioid-induced respiratory depression. J Neurosci 31:1292–1301. 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4611-10.2011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muers MF (2002) Opioids for dyspnoea. Thorax 57:922–923. 10.1136/thorax.57.11.922 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nagappa M, Weingarten TN, Montandon G, Sprung J, Chung F (2017) Opioids, respiratory depression, and sleep-disordered breathing. Best Pract Res Clin Anaesthesiol 31:469–485. 10.1016/j.bpa.2017.05.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Niscola P, Scaramucci L, Romani C, Giovannini M, Maurillo L, del Poeta G, Cartoni C, Arcuri E, Amadori S, De Fabritiis P (2006) Opioids in pain management of blood-related malignancies. Ann Hematol 85:489–501. 10.1007/s00277-005-0062-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peña F, Parkis MA, Tryba AK, Ramirez JM (2004) Differential contribution of pacemaker properties to the generation of respiratory rhythms during normoxia and hypoxia. Neuron 43:105–117. 10.1016/j.neuron.2004.06.023 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peña F, Ramirez JM (2004) Substance P-mediated modulation of pacemaker properties in the mammalian respiratory network. J Neurosci 24:7549–7556. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Phillips RS, Rubin JE (2019) Effects of persistent sodium current blockade in respiratory circuits depend on the pharmacological mechanism of action and network dynamics. PLoS Comput Biol 15:e1006938. 10.1371/journal.pcbi.1006938 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prkic I, Mustapic S, Radocaj T, Stucke AG, Stuth EAE, Hopp FA, Dean C, Zuperku EJ (2012) Pontine μ-opioid receptors mediate bradypnea caused by intravenous remifentanil infusions at clinically relevant concentrations in dogs. J Neurophysiol 108:2430–2441. 10.1152/jn.00185.2012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ptak K, Zummo GG, Alheid GF, Tkatch T, Surmeier DJ, McCrimmon DR (2005) Sodium currents in medullary neurons isolated from the pre-Bötzinger complex region. J Neurosci 25:5159–5170. 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4238-04.2005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Purvis LK, Smith JC, Koizumi H, Butera RJ (2007) Intrinsic bursters increase the robustness of rhythm generation in an excitatory network. J Neurophysiol 97:1515–1526. 10.1152/jn.00908.2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ramirez JM, Baertsch NA (2018a) The dynamic basis of respiratory rhythm generation: one breath at a time. Annu Rev Neurosci 41:475–499. 10.1146/annurev-neuro-080317-061756 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ramirez JM, Baertsch N (2018b) Defining the rhythmogenic elements of mammalian breathing. Physiology (Bethesda) 33:302–316. 10.1152/physiol.00025.2018 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ramirez J-M, Burgraff NJ, Wei AD, Baertsch NA, Varga AG, Baghdoyan HA, Lydic R, Morris KF, Bolser DC, Levitt ES (2021) Neuronal mechanisms underlying opioid-induced respiratory depression: our current understanding. J Neurophysiol 125:1899–1919. 10.1152/jn.00017.2021 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ramirez JM, Schwarzacher SW, Pierrefiche O, Olivera BM, Richter DW (1998) Selective lesioning of the cat pre-Bötzinger complex in vivo eliminates breathing but not gasping. J Physiol 507:895–907. 10.1111/j.1469-7793.1998.895bs.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ramirez JM, Tryba AK, Peña F (2004) Pacemaker neurons and neuronal networks: an integrative view. Curr Opin Neurobiol 14:665–674. 10.1016/j.conb.2004.10.011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rekling JC, Feldman JL (1998) PreBötzinger complex and pacemaker neurons: hypothesized site and kernel for respiratory rhythm generation. Annu Rev Physiol 60:385–405. 10.1146/annurev.physiol.60.1.385 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rekling JC, Shao XM, Feldman JL (2000) Electrical coupling and excitatory synaptic transmission between rhythmogenic respiratory neurons in the preBötzinger complex. J Neurosci 20:RC113. 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.20-23-j0003.2000 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ren J, Poon BY, Tang Y, Funk GD, Greer JJ (2006) Ampakines alleviate respiratory depression in rats. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 174:1384–1391. 10.1164/rccm.200606-778OC [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ren ZY, Xu XQ, Bao YP, He J, Shi L, Deng JH, Gao X-J, Tang H-L, Wang Y-M, Lu L (2015) The impact of genetic variation on sensitivity to opioid analgesics in patients with postoperative pain: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Pain Physician 18:131–152. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ruangkittisakul A, Schwarzacher SW, Secchia L, Ma Y, Bobocea N, Poon BY, Funk GD, Ballanyi K (2008) Generation of eupnea and sighs by a spatiochemically organized inspiratory network. J Neurosci 28:2447–2458. 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1926-07.2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ruangkittisakul A, Schwarzacher SW, Secchia L, Poon BY, Ma Y, Funk GD, Ballanyi K (2006) High sensitivity to neuromodulator-activated signaling pathways at physiological [K+] of confocally imaged respiratory center neurons in on-line-calibrated newborn rat brainstem slices. J Neurosci 26:11870–11880. 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3357-06.2006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rubin JE, Hayes JA, Mendenhall JL, Del Negro CA (2009) Calcium-activated nonspecific cation current and synaptic depression promote network-dependent burst oscillations. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 106:2939–2944. 10.1073/pnas.0808776106 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rudd RA, Seth P, David F, Scholl L (2016) Increases in drug and opioid-involved overdose deaths—United States, 2010–2015. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 65:1445–1452. 10.15585/mmwr.mm655051e1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rybak IA, Molkov YI, Jasinski PE, Shevtsova NA, Smith JC (2014) Rhythmic bursting in the pre-Bötzinger complex: mechanisms and models. Prog Brain Res 209:1–23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saunders SE, Levitt ES (2020) Kölliker-Fuse/Parabrachial complex mu opioid receptors contribute to fentanyl-induced apnea and respiratory rate depression. Respir Physiol Neurobiol 275:103388. 10.1016/j.resp.2020.103388 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scholl L, Seth P, Kariisa M, Wilson N, Baldwin G (2018) Drug and opioid-involved overdose deaths—United States, 2013–2017. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 67:1419–1427. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seth P, Rudd RA, Noonan RK, Haegerich TM (2018) Quantifying the epidemic of prescription opioid overdose deaths. Am J Public Health 108:500–502. 10.2105/AJPH.2017.304265 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith JC, Ellenberger HH, Ballanyi K, Richter DW, Feldman JL (1991) Pre-Bötzinger complex: a brainstem region that may generate respiratory rhythm in mammals. Science 254:726–729. 10.1126/science.1683005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steinmetz NA, Aydin C, Lebedeva A, Okun M, Pachitariu M, Bauza M, Beau M, Bhagat J, Böhm C, Broux M, Chen S, Colonell J, Gardner RJ, Karsh B, Kloosterman F, Kostadinov D, Mora-Lopez C, O'Callaghan J, Park J, Putzeys J, et al. (2021) Neuropixels 2.0: A miniaturized high-density probe for stable, long-term brain recordings. Science 372:eabf4588. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stucke AG, Miller JR, Prkic I, Zuperku EJ, Hopp FA, Stuth EA (2015) Opioid-induced respiratory depression is only partially mediated by the preBötzinger complex in young and adult rabbits in vivo. Anesthesiology 122:1288–1298. 10.1097/ALN.0000000000000628 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sun X, Thörn Pérez C, Halemani D N, Shao XM, Greenwood M, Heath S, Feldman JL, Kam K (2019) Opioids modulate an emergent rhythmogenic process to depress breathing. Elife 8:e50613. 10.7554/eLife.50613 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thoby-Brisson M, Ramirez JM (2000) Role of inspiratory pacemaker neurons in mediating the hypoxic response of the respiratory network in vitro. J Neurosci 20:5858–5866. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thoby-Brisson M, Ramirez JM (2001) Identification of two types of inspiratory pacemaker neurons in the isolated respiratory neural network of mice. J Neurophysiol 86:104–112. 10.1152/jn.2001.86.1.104 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tryba AK, Peña F, Lieske SP, Viemari JC, Thoby-Brisson M, Ramirez JM (2008) Differential modulation of neural network and pacemaker activity underlying eupnea and sigh-breathing activities. J Neurophysiol 99:2114–2125. 10.1152/jn.01192.2007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tryba AK, Peña F, Ramirez JM (2003) Stabilization of bursting in respiratory pacemaker neurons. J Neurosci 23:3538–3546. 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.23-08-03538.2003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tryba AK, Peña F, Ramirez JM (2006) Gasping activity in vitro: a rhythm dependent on 5-HT2A receptors. J Neurosci 26:2623–2634. 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4186-05.2006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tryba AK, Ramirez JM (2004) Hyperthermia modulates respiratory pacemaker bursting properties. J Neurophysiol 92:2844–2852. 10.1152/jn.00752.2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Varga AG, Reid BT, Kieffer BL, Levitt ES (2019) Differential effects of morphine on a dispersed respiratory network to induce respiratory depression in awake mice. FASEB J 33:546.542–546.542. 10.1096/fasebj.2019.33.1_supplement.546.2 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Varga AG, Reid BT, Kieffer BL, Levitt ES (2020) Differential impact of two critical respiratory centres in opioid-induced respiratory depression in awake mice. J Physiol 598:189–205. 10.1113/JP278612 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Viemari JC, Ramirez JM (2006) Norepinephrine differentially modulates different types of respiratory pacemaker and nonpacemaker neurons. J Neurophysiol 95:2070–2082. 10.1152/jn.01308.2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wei AD, Ramirez JM (2019) Presynaptic mechanisms and KCNQ potassium channels modulate opioid depression of respiratory drive. Front Physiol 10:1407. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wenninger JM, Pan LG, Klum L, Leekley T, Bastastic J, Hodges MR, Feroah TR, Davis S, Forster HV (2004) Large lesions in the pre-Bötzinger complex area eliminate eupneic respiratory rhythm in awake goats. J Appl Physiol (1985) 97:1629–1636. 10.1152/japplphysiol.00953.2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wojciechowski P, Szereda-Przestaszewska M, Lipkowski AW (2007) Supranodose vagotomy eliminates respiratory depression evoked by dermorphin in anaesthetized rats. Eur J Pharmacol 563:209–212. 10.1016/j.ejphar.2007.02.012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang CF, Feldman JL (2018) Efferent projections of excitatory and inhibitory preBötzinger complex neurons. J Comp Neurol 526:1389–1402. 10.1002/cne.24415 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang Z, Zhang C, Zhou M, Xu F (2012) Activation of opioid μ-receptors, but not δ- or κ-receptors, switches pulmonary C-fiber-mediated rapid shallow breathing into an apnea in anesthetized rats. Respir Physiol Neurobiol 183:211–217. 10.1016/j.resp.2012.06.032 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]