Abstract

Objectives

Learning healthcare systems are foundational for measuring and achieving value in oral health care. This paper describes the components of a preventive dental care program and the quality of care in a large dental accountable care organization.

Methods

A retrospective study design describes and evaluates the cross-sectional measures of process of care (PoC), appropriateness of care (AoC), and outcomes of care (OoC) extracted from the electronic health record (EHR), between 2014–2019. Annual and composite measures are derived from EHR-based clinical decision support for risk determination, diagnostic and treatment terminology, and DMFT measures.

Results

Annually, 253,515 ± 27,850 patients were cared for with 618,084 ± 80,559 visits, 209,366 ± 22,300 exams and 2,072,844 ± 300,363 clinical procedures. PoC metrics included provider adherence (98.3%) in completing caries risk assessments and patient receipt (96.9%) of a proactive dental care plan. AoC metrics included patients receiving prevention according to the risk-based protocol. The percent of patients at risk for caries receiving fluoride varnish was 95.4 ± 0.4%. OoC metrics included untreated decay and new decay. The 6-year average prevalence of untreated decay was 11.3 ± 0.3%, and average incidence of new decay was 13.6 ± 0.5%, increasing with risk level: low=7.5%, medium=18.8%, high=29.4% and extreme=28.1%.

Conclusions

The preventive dental care system demonstrates excellent provider adherence to the evidence-based prevention protocol, with measurably better dental outcomes by patient risk compared to national estimates. These achievements are enabled by a value-centric, accountable model of care and incentivized by a compensation model aligned with performance measures.

Keywords: Dentistry, Dental Caries, Electronic Health Records, Primary Prevention, Secondary Prevention, Dental Informatics, Value-based Payment

Introduction:

Dental caries (tooth decay) is the most prevalent chronic disease in the US, affecting children and adults. Healthy People 2020 goals for children and adults include reducing untreated decay. Sixteen percent of children have untreated dental decay. Experience with tooth decay varies by age and dentition: 36% of children ages 2–8 years with primary teeth, 21% among children ages 6–11 with both primary and permanent teeth, rising to 58% of children ages 12–19 with permanent teeth.(1) In adults, 91% of people ages 20–64 have experienced tooth decay, with 27% of this population having untreated tooth decay.(1) Oral care is among the greatest unmet health needs in the US.(2) While oral health is universally accepted as a critical component of overall health and wellbeing, 30% of the US population lacks dental insurance coverage, resulting in the US Surgeon General declaring dental caries a “silent epidemic.”(3) The economic cost to society of the oral disease burden is substantial, with annual US dental expenditures at $96 billion in 2015.(4)

Value-based reforms to the delivery and payment of dental care have been touted as critical to making progress in improving access to high-quality care and reducing the overall burden of oral disease. “Value-based care (VBC) is a person/patient centered approach to health care delivery designed to improve health outcomes and lower the cost of care. Value-based payers reimburse providers based on the quality of care instead of the volume of care.”(5) While value-based payment models have been conceptualized,(6) there are few empirical studies which demonstrate this approach. In part, this is because the traditional surgical approach to treatment in dentistry, along with the historical small business, fee-for-service delivery model, leaves providers ill-equipped to measure or manage population level outcomes.(7) Medicare and Medicaid have pioneered contracting in new managed care and value-based models,(8) but traditional Medicare doesn’t cover dental care, and most dentists don’t accept Medicaid.(9) However, as dental care evolves and consolidates into larger delivery systems,(10) we see both infrastructure and contracting changes that enable value-based approaches. Large organizations are able to adopt the necessary tools such as health information technology (HIT), electronic health records (EHRs), dental diagnostic terminology and clinical decision support (CDS) that enable a population, prevention-based, chronic disease-management approach.

By integrating HIT into patient care, dental practices can enable the implementation of standardized, evidence-based guidelines endorsed by the American Dental Association (ADA) and create new opportunities for research and quality improvement both at the individual patient as well as population levels.(11) Embracing HIT has occurred simultaneously with growing evidence that supports philosophically shifting dental caries treatment away from conventional surgical dentistry in favor of medical management with an emphasis on disease treatment, prevention and personalized care.(12) This is achieved by using existing, easy-to-implement caries risk assessment (CRA) tools, embedded within the electronic health record, that have demonstrated high predictive validity for future caries.(13, 14) Randomized controlled trials that used risk prediction to target non-surgical therapies to high-risk patients have demonstrated reduced caries risk(15) and caries incidence,(16) as well as cost-effectiveness.(17) When providers and patients engage in risk-based preventive care, patients experience less tooth decay and require fewer surgical treatments.(14) These approaches are the bedrock of bringing value to oral health care.

Willamette Dental Group (WDG), a large dental accountable care organization, is an example of a learning healthcare system driving value in oral health care, aiming to align science, informatics, incentives, and culture through a continuous quality improvement process moving toward innovation. WDG’s mission is “to deliver proactive patient care through a partnership with our patients to stop the disease-repair cycle by means of evidence-based methods of prevention and treatment.” WDG is a privately-owned organization consisting of a large, multi-specialty group practice and integrated dental insurance company delivering care through a full-risk capitation model. With 50 dental offices located throughout Washington (WA), Oregon (OR), and Idaho (ID), the company employs 155 general dentists, 52 specialists, 235 hygienists, 222 care advocates and 549 dental assistants, among it’s over 1,500 employees. Their caries prevention program includes a robust prevention focus, self-management support, CDS, efficient and consistent delivery system design, clinical information systems, and quality of care measures derived from system-wide EHR/HIT. This has been made possible through a $10M investment in HIT, along with high levels of engagement and participation by leadership from the executive to clinic levels and fully integrating data capacity and roles into every level of the organizational system. Their model of care embraces the tenets of a learning healthcare system and the quadruple aim (better health, better care, lower cost, and an engaged workforce) by utilizing the EHR to standardize clinical workflows and robust data analytics for continual quality improvement.(18–22)

This study describes the implementation of WDG’s evidence-based dental caries prevention and management program, and describes its performance measures over the first six years using EHR measures derived from dental diagnostic terms and a newly validated clinical outcome measure.(13, 23) The study aim is to utilize HIT to track and report retrospective, cross-sectional, annual oral health measures in a large health care system that has implemented current best practices to improve oral health care quality and effectiveness, and examine the value of this approach in managing caries in the dental clinic setting.

Methods:

This work was conducted under approval of the UCSF Institutional Review Board.

Caries Preventive Care Program

Using the current best evidence and practice guidelines, based on caries risk(13, 16, 24–30), WDG created the Caries Preventive Care Program Clinical Guidelines (Table 1 and supplemental materials for evidence). WDG’s caries preventive care program is a treatment philosophy that is standardized, diagnosis-driven, risk-based and evidence-based with CDS in a preventive care model. The program combines prevention, minimally invasive intervention and patient engagement to reduce caries risk status and improve patient outcomes. Patients receive oral hygiene instructions to reduce plaque, diet management to reduce sugars and fermentable carbohydrates, fluoride supplements for developing teeth in non-fluoridated areas, toothpaste (over the counter or prescription) and anti-cavity rinses, antimicrobial rinses, in-office fluoride varnish, sealants, standardized recall and radiographs according to caries risk level and age (less than 6, and 6 and older).

Table 1.

Willamette Dental Group Caries Preventive Care Program Clinical Guidelines

| Caries Risk Level | In-Office Preventive Care | Home Care Guidance | Home Care Prevention Products | Next Caries Risk Assessment | Next Comprehensive Exam |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Low | Sealants for teeth with pits & fissures at risk for breakdown | OHI to reduce plaque & diet evaluation to reduce sugar | OTC toothpaste OTC mouthwash | @ next comprehensive exam (12 months) | @ 12 months BW radiographs every 24–36 mos. |

| Moderate | Above + FV, consider SDF for interproximal lesions | OHI to reduce plaque & diet evaluation to reduce sugar | Rx toothpaste or OTC toothpaste + OTC mouthwash | @ 6 months SDF on cavitated or incipient lesions or FV if no lesions, BWs if monitoring interproximal lesions, re-evaluate risk | @ 12 months FV or SDF, BWs if monitoring interproximal lesions |

| High & Extreme | Above + minimally invasive restorations or SDF on all cavitated surfaces | OHI to reduce plaque & diet evaluation to reduce sugar | Rx toothpaste, CHX regimen if not treating with SDF, acid reduction strategy if has dry mouth | @ 3 or 6 months Above + re-evaluate risk monitoring interproximal lesions | @ 6 or 12 months FV or SDF, BW radiographs |

FV= fluoride varnish; SDF= silver diamine fluoride; OHI= oral hygiene instruction (brushing/flossing);

Rx = prescription 1.1% fluoride toothpaste; CHX= chlorhexidine/anti-microbial rinse;

BW= bitewing radiographs; OTC = over-the-counter anti-cavity fluoride products

To implement the program in 2013 over a 6-month period, WDG trained all employees involved in clinical care with formative assessments consisting of written and hands-on case-based examinations. WDG launched the program company-wide in the fall of 2013, with a 3-month roll-in period. Every patient receiving a comprehensive or periodic oral exam completes a demographic and standardized health and dental history form recorded in the EHR. A standardized caries risk determination is achieved by consideration of disease indicators, risk factors and protective factors, calculated in an integrated CDS algorithm in the EHR.(13, 31, 32) The clinicians select dental diagnoses before selecting a procedure code using a validated set of standardized diagnostic terminology (13, 33). CDS in the EHR suggests/flags procedures that may be performed to treat the diagnosis.

The entire team has access to the system-wide EHR (axiUm, Exan, Coquitlam, BC, Canada). The team is trained to document health history, risk status, diagnosis, and treatment plan in the EHR, which automatically populates a personalized Proactive Dental Care Plan (PDCP) that identifies the patient’s disease risk using a visual scale of green (low) to red (high) and lists at-home and in-office preventive actions to reduce risk and decay. The PDCP is used to foster patient engagement and to counsel and motivate patients toward specific caries preventive interventions based on caries risk, such as in-office applications of fluoride varnish, over-the-counter anti-cavity products, prescription antimicrobial rinses, or prescription high fluoride toothpaste, and diet modifications. High-risk patients are scheduled to return for a CRA every 3–6 months for patient education, motivation, and assessment. Trained office staff known as Care Advocates coordinate managing all patients, focusing additional care and interventions for high-risk patients using a structured form in the EHR for follow-up.

Data Metrics and Analytics

The WDG caries prevention program is supported by performance data analytics available at the patient, office, regional and organizational levels. Provider teams have multiple measures at the individual level readily available and displayed in the EHR. Measures to describe the patient population are Members enrolled, Visits, and Patients with an exam. The care measures we include in this study are for Process of Care (PoC), Appropriateness of Care (AoC) and Outcomes of Care (OoC). PoCs are derived from the robust documentation of patient information, including medical and dental history, vital signs, extra/intraoral examination, self-reported oral hygiene/nutrition, findings of demineralization and decay, and conditions, including existing restorations. The measures include patients with a CRA, provider-selected caries risk alignment to CDS and patients receiving their PDCP. AoCs include radiographic recall interval, radiograph planned/taken, fluoride varnish and silver diamine fluoride (SDF) applications for cavitated carious lesions in dentin, and procedures in phase. OoCs are derived from patients with an exam and measured with a validated tool that calculates the recognized standard caries index outcome measures; number of decayed, missing, or filled permanent teeth and tooth surfaces (DMFT/S for permanent teeth and dmft/s for primary teeth).(23) WDG adapted these caries indices to measure untreated decay and new decay, the OoC measures. (Full definitions of measures are available in online supplementary material.)

For this retrospective study, all data were extracted directly from the EHR’s relational database management system, using standard query language (SQL) statements, from January 1, 2014 through December 31st, 2019. Data were analyzed annually, calculating annual percentages, averages, and standard deviations.

Results:

Patient Population.

Between 2014–2019, there were 1,521,088 patients seen, 3,708,503 visits and 12,437,065 clinical procedures performed at WDG. The average number of members enrolled in WDG per year was 441,631 ± 41,588. Among all members, children (less than 18 years of age) were 25 ± 1.4%, adults (ages 18 to 55) were 58.2 ± 0.9% and seniors (greater than 55 years of age) were 16.7 ± 0.5%. Of the patients who had a visit, 55.6% reside in OR, 34.8% reside in WA and 9.6% reside in ID, while 44.1% were male and 55.9% were female. The number of patients with a visit increased from 221,471 to 291,434. The number of patient visits increased from 530,137 to 735,354, with an average of 2.4 visits per patient per year. Procedures increased from 1,790,452 to 2,509,618, with an average of 3.4 clinical procedures/visit. In total, 1,256,197 patient examinations were completed, with 345,204 comprehensive exams, 887,688 periodic oral exams and 28,305 oral evaluations for patients less than 3 years old. In each year, 82.6 ± 0.4% of patients seen had an examination within the year (D0150, D0120 or D0145), which increased from 183,779 to 241,540. Of the patients seen annually, 22.7 ± 0.6% were seen for new patient visits (D0150), 58.4 ± 0.7% were periodic oral examinations (D0120) and 2.3 ± 0.1% were oral evaluations for patients less than 3 years old (D0145) (Table 2).

Table 2.

Description of patient population of Willamette Dental Group Caries Preventive Care Program from 2014 through 2019

| Patient Population | Program Year | Average (SD) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2014 | 2015 | 2016 | 2017 | 2018 | 2019 | ||

| Members enrolled | 397,146 | 403,224 | 425,221 | 445,315 | 476,410 | 502,471 | 441,631 (41,588) |

| Children members (< 18 yr) | 108,674 | 104,533 | 106,023 | 109,172 | 114,043 | 118,167 | 110,102 (5,121) |

| Adult members (18–55 yr) | 225,283 | 232,633 | 248,177 | 260,804 | 280,996 | 297,149 | 257,507 (27,850) |

| Senior members (> 55 yr) | 63,187 | 66,057 | 71,020 | 75,338 | 81,371 | 87,153 | 74,021 (9,143) |

| Utilization rate | 54.3% | 55.8% | 56.3% | 57.9% | 57.0% | 57.1% | 56.5% (1.3) |

| Churn rate | 22.8% | 21.2% | 20.1% | 19.2% | 12.6% | 19.1% | 19.2% (3.5) |

| Patients with a visit | 221,471 | 229,543 | 242,179 | 260,485 | 275,976 | 291,434 | 253,515 (27,280) |

| Visits | 530,137 | 550,003 | 580,489 | 624,649 | 687,871 | 735,354 | 618,084 (80,559) |

| Clinical procedures | 1,790,452 | 1,818,520 | 1,891,939 | 2,065,406 | 2,361,130 | 2,509,618 | 2,072,844 (300,363) |

| Patients with Exam | 183,779 | 190,610 | 198,754 | 214,730 | 226,784 | 241,540 | 209,366 (22,300) |

| Comprehensive Oral Exams (D0150) | 52,548 | 50,934 | 55,230 | 59,484 | 63,532 | 63,476 | 57,534 (5,456) |

| Periodic Oral Exams (D0120) | 128,048 | 136,154 | 140,078 | 151,159 | 158,887 | 173,362 | 147,948 (16,570) |

| Oral Evaluations (<3 yr old) (D0145) | 3,973 | 4,239 | 4,202 | 4,876 | 5,290 | 5,725 | 4,718 (695) |

Process of Care (PoC)

PoC measures of the preventive care program were consistently high throughout the six-year period (Table 3 and supplemental online information). A total of 1,235,254 caries risk assessments were completed with an annual average of 205,876 ± 21,590 patients receiving a CRA at their exam visit (98.3 ± 0.2%). The caries risk of the patients receiving a CRA was 62.6 ±2.8% low risk, 16.6 ± 2.3% moderate risk, 20.4 ± 1.3% high risk and 0.4 ± 0.2% extreme risk. The provider-selected caries risk was aligned with the CRA CDS algorithm 90.2 ± 1.3% of the time. Provider alignment with CRA CDS for low risk was 93.6 ± 0.5%, moderate risk was 74.5 ± 4.5%, high risk was 92.6 ± 0.5% and extreme risk was 87.4 ± 3.0%. Patients received a PDCP 96.9 ± 0.2% of the time.

Table 3.

Process of Care (PoC), Appropriateness of Care (AoC) and Outcomes of Care (OoC) measures of Willamette Dental Group Caries Preventive Care Program from 2014 through 2019

| Program Year | Average (SD) | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2014 | 2015 | 2016 | 2017 | 2018 | 2019 | ||

| Process of Care (PoC) | |||||||

| Percent of patients with CRA | 98.4% | 98.6% | 98.5% | 98.3% | 98.2% | 98.1% | 98.3% (0.2) |

| Proactive Dental Care Plan | 96.9% | 97.2% | 97.2% | 96.8% | 96.8% | 96.7% | 96.9% (0.2) |

| Appropriateness of Care (AoC) | |||||||

| Radiographs Planned Interval | 94.7% | 95.2% | 95.4% | 95.0% | 92.6% | 94.9% | 94.6% (1.0) |

| Radiographs Taken (on interval) | 78.3% | 77.1% | 78.1% | 78.3% | 74.2% | 74.9% | 76.8% (1.7) |

| Fluoride Varnish (elevated risk) | 94.8% | 95.6% | 95.3% | 95.1% | 95.6% | 96.1% | 95.4% (0.4) |

| Silver Diamine Fluoride Patients with high/extreme caries risk, within 30 days of exam* | n/a | n/a | 0.9% | 12.5% | 23.9% | 18.6% | 14.0% (9.8) |

| Outcome of Care (OoC) | |||||||

| Patients with untreated decay at end of year | 21,071 | 20,748 | 21,856 | 23,366 | 25,454 | 27,989 | 23,414 (2,833) |

| Patients with new decay | 11,008 | 15,774 | 17,331 | 17,993 | 19,842 | 23,079 | 17,505 (4,050) |

SDF= Silver diamine fluoride use was added to the program in 2016

Appropriateness of Care (AoC)

AoC measures of the preventive care program were also consistently high throughout the six-year period (Table 3). Providers planned recall radiographs according to the evidence-based protocol intervals on average 94.6 ± 1.0% of the time. The radiographs are taken shorter than interval 76.8 ± 1.7% of the time. Dental procedures were completed in the appropriate phase of care on average 99.6 ± 0.04% of the time. Patients at elevated risk (moderate/high/extreme) received fluoride varnish on average 95.4 ± 0.4% of the time. SDF application to arrest deep cavitated caries in dentin was incorporated into the preventive care program in 2016. Use of SDF in high/extreme caries risk patients increased beginning with its introduction, 0.9% in 2016, 12.5% in 2017, 23.9% in 2018, and 18.6% in 2019.

Outcomes of Care (OoC)

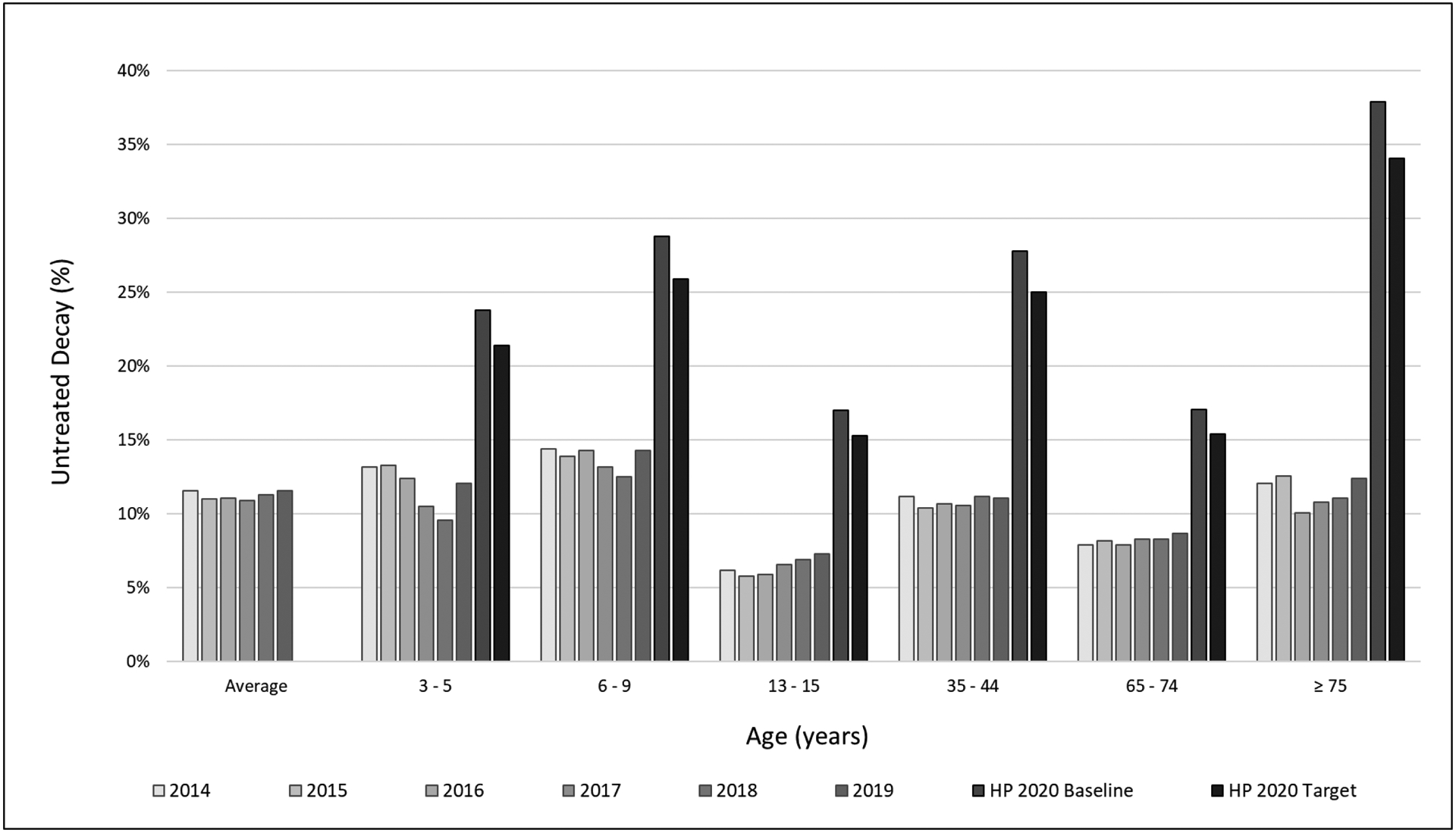

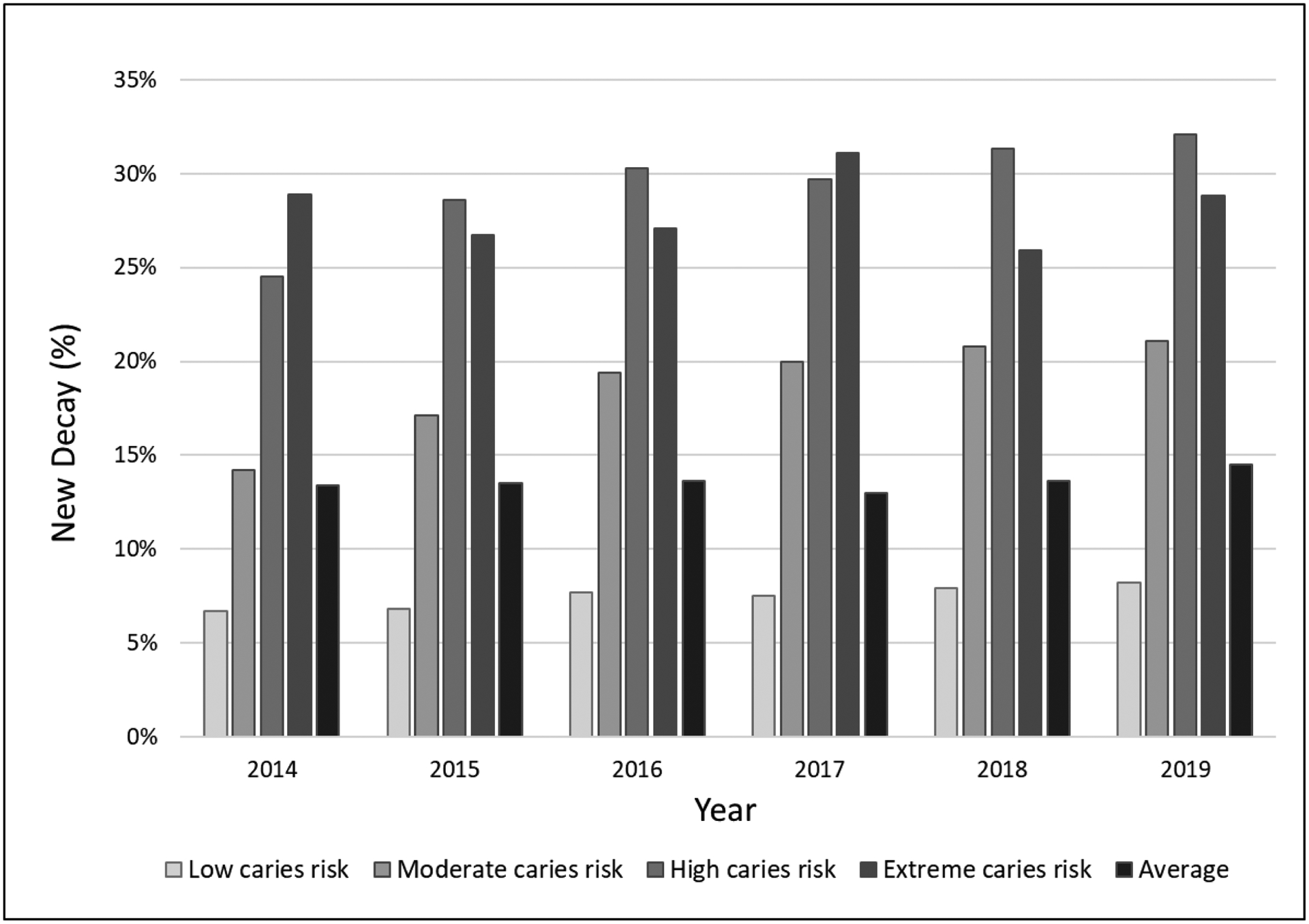

On average 207,828 ± 23,028 patients received an annual examination, of which, 23,414 ± 2,833 patients had untreated decay at the end of the year. The percent of patients with untreated decay was on average 11.3 ± 0.3% (Table 3 and supplemental online information). Percent of children ages 3 to 5 with untreated decay on primary teeth was on average 11.8 ± 1.5%. Percent of children ages 6 to 9 years old with untreated decay on primary or permanent teeth was on average 13.8 ± 0.8%. Percent of adolescents ages 13 to 15 years with untreated decay was on average 6.4 ± 0.6%. Percent of adults ages 25 to 44 years with untreated coronal caries averaged 10.9 ± 0.4% while those ages 65 to 74 years averaged 8.2 ± 0.3%, and the percent of adults ages 75 and older with untreated coronal or root caries averaged 11.5 ± 1.0%. All of the WDG measures were lower than their comparable HP2020 baseline and target measures (Figure 1). On average, 128,102 ± 26,813 patients had a qualifying prior exam, with an average of 17,505 ± 4,050 patients having new decay annually (13.6 ± 0.5%). Of the patients who had a CRA of low caries risk, 7.5 ± 0.6% had new decay, while 18.8 ± 2.7% of moderate risk, 29.4 ± 2.7% of high risk and 28.1 ± 1.9% of extreme risk patients having new decay (Figure 2).

Figure 1.

Prevalence of Untreated Decay as a function of age and average - Outcome of Care Measures (OoC) of Willamette Dental Group Caries Preventive Care Program from 2014 through 2019, compared to Healthy People 2020 (HP 2020) Baseline and Target measures

Figure 2.

Incidence of New Decay as a function of caries risk and average - Outcome of Care Measures (OoC) of Willamette Dental Group Caries Preventive Care Program from 2014 through 2019

Discussion:

This paper describes the first six years of measurable performance of a model of dental care that is evidence-based, standardized, diagnosis-driven, risk-based, clinical decision supported, patient-centered, preventive and minimally invasive, deployed in a large dental accountable care organization. The system-wide EHR enables standardized care and provides the data for performance analytics to drive patient care, provider behavior, and quality improvement throughout the enterprise.(22) The value-based approach to care advances the quadruple aim of better health, better care, lower cost and an engaged workforce.(18–20).

The goal of the program is to prevent, arrest, remove and restore decay. At WDG, it is considered a failure of prevention when a dentist must intervene surgically. The system allows the practitioners easy access to data and decisions support that allows them to adhere to best practices that underpin the clinical approach. In the course of this retrospective study and through results of satisfaction surveys, we found that the program was well-received by patients and providers.(34, 35) Adherence to PoC and AoC measures is excellent. PoC, AoC and OoC measures provide data elements that populate the patients PDCP. Patients receive their PDCP, which is a PoC measure that includes the caries risk (PoC), at home prevention and in office prevention and treatment recommendations (AoC, e.g. prescription fluoride toothpaste and fluoride varnish) and their oral health status (OoC, untreated decay and new decay). Patients receive appropriate prevention. Restorative care provided is within the appropriate phase, addressing patients’ emergency needs first, then disease removal and restoration before tooth reconstruction and replacement all with ongoing prevention and recall.

WDG is a learning healthcare system that utilizes a robust HIT system to drive better oral health outcomes at the patient, provider, office, region and company-wide levels.(36) The program uses standardized care following guidelines and best practices with CDS within a robust EHR. This allows the organization to maintain control over quality improvement as the organization grows and new evidence for practice is developed. The number of WDG offices stayed steady over the study period. As the number of members increased, there was an increase in the number of patient exam visits from 183,779 to 241,540. WDG increased the number of providers during the study period to accommodate the growth in membership. The percent of patients with a risk assessment at exam stayed steady at over 98% attesting to the robust IT system and culture to support the practice over time.

The comprehensive use of CRA drives value by concentrating resources where they are most needed to positively influence population health, as our data on the connection between caries risk level and new decay clearly show. In this study, large scale implementation of caries management by risk assessment (CAMBRA) enabled the proportion of patients with new decay to be consistently lower than previous work validating CRA(13, 14) and in a randomized prospective clinical trial(16). The prevalence of untreated caries on average and for each age group were lower than HP2020 baseline and target goals,(37) indicating the WDG caries prevention program at the population level has positive program impact.

WDG drives this level of performance by utilizing data analytics in their value-based delivery model with goals and measures at the provider, office, region and company level that are incorporated in the “pay for value” compensation model. Factors considered for compensation/incentives for the dentists are a combination of patient mix, schedule effectiveness score, quality improvement score (PoC, AoC and OoC measures) and customer service. The compensation model emphasizes a preventive care philosophy, incentivizing performance, value and outcomes (e.g., reduction in untreated caries and new decay).

PoC measures, as quality assurance measures, allows for the capture of the essential elements of patient care quality. Adherence to PoC measures allows for the determination of AoC measures, which ensure patients receive appropriate care based on caries risk, including prevention and treatment of dental decay. Adherence to both PoC and AoC measures are critical in tracking and achieving outcomes, where OoC measures allow for evaluating the preventive care program’s success in removing and restoring decay (i.e., untreated decay) and prevention (i.e., new decay). All three sets of measures work together to help the organization achieve appropriate and timely care and provide data for continual quality improvement.

This model of care is different than traditional fee for service dental practice and dental service organizations where the financial incentives are procedure based. Similar to physicians’ practice consolidation, large group practices are now the largest growth sector, reshaping the future of dentistry.(10, 38) WDG is similar to other large group dental practices, such as HealthPartners and Kaiser Permanente Northwest, enrolled in the national dental Practice-Based Research Network, which have been shown to have many commonalities with dentists at large in the US.(39) Yet, each WDG office is functionally similar to traditional dental practices in the community. WDG dentists are also representative of the profession’s future diversity. Compared to other dentists in OR, WA, and ID, WDG dentists are more commonly female (35.9% vs. 26.2%), non-white (47.5% vs. 22.3%), and younger (29.5% ages 21–34 vs. 16.7%). Similarly, WDG’s patient demographics are comparable to overall population demographics in ID, OR, and WA (50% female, 26% non-white, 19% Medicaid beneficiaries)(40, 41) and dental attenders across the US (58% female, 30% non-white, 29% Medicaid beneficiaries).(42)

This study describes the organization, measurement, and clinical implications of widely incorporating a risk-based caries prevention program for a large population with long-term follow-up. This paper provides rich context for ongoing studies focused on the real-world effectiveness of clinical preventive approaches to patient and population health management in dentistry. By utilizing the robust EHR data, we will be able to further study the model of care longitudinally, through the construction of matched groups for health disparities research in order to draw causal inferences.(43) The economic aspects of this model of care can also be assessed to determine the cost-effectiveness (i.e., the preventive costs to cavity) and cost-benefit (i.e., patients’ willingness to pay for prevention verses restoration). In sum, the observational research on systems performance is ripe for translation, replication, and dissemination.

With the challenges of COVID-19, dentistry is in the process of transforming and adapting its care delivery. To protect patients, providers and the public, dentistry is prioritizing emergent and urgent care over routine dental care, until testing is more widely available. Due to the hazards of aerosols, routine restorative procedures and ultrasonics require additional safety requirements. The model of care reported in this paper is very well suited towards changes required by COVID-19 with their focus on prevention and a minimally invasive approach. Use of silver diamine fluoride to arrest deep cavitated carious lesions in dentin, atraumatic restorative technique and glass ionomer restorations as minimally invasive dentistry lowers the risk of COVID-19 exposure to patients, providers and the public. Learning healthcare systems will adapt quickly and meet the challenges posed by COVID-19

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements:

Research reported in this paper was supported by the National Institute on Minority Health and Health Disparities of the National Institutes of Health under award number R01MD013719: Reducing Oral Health Disparities in Children: Assessing the Multilevel Impact of a Standardized Preventive Dental Care System. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

We are grateful to Dr. Eugene Skourtes, the executive leadership and the entire Willamette Dental Group organization, without which this study would not have been possible. We acknowledge the excellent background work of Dr. Larry Jenson made possible by the financial support provided by the Khandros Family Foundation. We acknowledge Shaeema Siddiqui for her contribution to reference management that was supported by the Raymond L. and Mary V. Bertolotti Distinguished Professorship in Restorative Dentistry.

Research reported in this article was supported by the National Institute on Minority Health and Health Disparities of the National Institutes of Health under award number R01MD013719: Reducing Oral Health Disparities in Children: Assessing the Multilevel Impact of a Standardized Preventive Dental Care System. Support was also provided by the National Institute of Dental and Craniofacial Research under award R01DE024166: Implementing Dental Quality Measures in Practice. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health. The authors are grateful to Dr. Eugene Skourtes, the executive leadership, and the entire Willamette Dental Group organization, without which this study would not have been possible. The authors acknowledge the excellent background work of Dr. Larry Jenson made possible by the financial support provided by the Khandros Family Foundation. The authors acknowledge Shaeema Siddiqui for her contribution to reference management that was supported by the Raymond L. and Mary V. Bertolotti Distinguished Professorship in Restorative Dentistry.

References:

- 1.Dye BA, Thornton-Evans G, Li X, Iafolla TJ. Dental caries and tooth loss in adults in the United States, 2011–2012. Hyattsville, MD: National Center for Health Statistics; 2015. May 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Institute of Medicine. Improving Access to Oral Health Care for Vulnerable and Underserved Populations. Washington, DC: National Academies Press; 2011. May. [Google Scholar]

- 3.U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. Oral Health in America: A Report of the Surgeon General. Rockville, MD: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 4.M RJ, R F. Dental Services: Use, Expenses, Source of Payment, Coverage and Procedure Type, 1996–2015. In: Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality, editor. Research Findings No 38 Rockville, MD: 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Apostolon D. Value-Based Care: DentaQuest Partnership for Oral Health Advancement; 2018. [Available from: https://www.dentaquestpartnership.org/about/keys-to-success/value-based-care.

- 6.Riley W, Doherty M, Love K. A framework for oral health care value-based payment approaches. J Am Dent Assoc. 2019;150(3):178–85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Rubin MS, Edelstein BL. Perspectives on evolving dental care payment and delivery models. J Am Dent Assoc. 2016;147(1):50–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Value-Based Programs: Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services 2020. [Available from: https://www.cms.gov/Medicare/Quality-Initiatives-Patient-Assessment-Instruments/Value-Based-Programs/Value-Based-Programs.

- 9.American Dental Association HPI. Dentist Participation in Medicaid or CHIP Chicago, IL: American Dental Association; [Available from: https://www.ada.org/~/media/ADA/Science%20and%20Research/HPI/Files/HPIGraphic_0318_1.pdf?la=en. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Health Policy Institute. How Big are Dental Service Organizations? Chicago, IL: American Dental Association; 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Liu K, Acharya A, Alai S, Schleyer TK. Using electronic dental record data for research: a data-mapping study. J Dent Res. 2013;92(7 Suppl):90S–6S. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Fontana M, Young DA, Wolff MS. Evidence-based caries, risk assessment, and treatment. Dent Clin North Am. 2009;53(1):149–61, x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Domejean S, White JM, Featherstone JD. Validation of the CDA CAMBRA caries risk assessment--a six-year retrospective study. J Calif Dent Assoc. 2011;39(10):709–15. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Chaffee BW, Cheng J, Featherstone JD. Baseline caries risk assessment as a predictor of caries incidence. J Dent. 2015;43(5):518–24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Rechmann P, Chaffee BW, Rechmann BMT, Featherstone JDB. Changes in caries risk in a practice-based randomized controlled trial. Adv Dent Res. 2018;29(1):15–23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Featherstone JD, White JM, Hoover CI, Rapozo-Hilo M, Weintraub JA, Wilson RS, et al. A randomized clinical trial of anticaries therapies targeted according to risk assessment (caries management by risk assessment). Caries Res. 2012;46(2):118–29. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Warren E, Pollicino C, Curtis B, Evans W, Sbaraini A, Schwarz E. Modeling the long-term cost-effectiveness of the caries management system in an Australian population. Value Health. 2010;13(6):750–60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Medicine Io. The Learning Healthcare System: Workshop Summary. Olsen L, Aisner D, McGinnis JM, editors. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press; 2007. 374 p. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Institute of Medicine. Best Care at Lower Cost: The Path to Continuously Learning Health Care in America. Washington DC: National Academy of Sciences; 2012. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Berwick DM, Nolan TW, Whittington J. The triple aim: care, health, and cost. Health affairs (Project Hope). 2008;27(3):759–69. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Bodenheimer T, Sinsky C. From triple to quadruple aim: care of the patient requires care of the provider. Annals of family medicine. 2014;12(6):573–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Finkelstein J, Zhang F, Levitin SA, Cappelli D. Using big data to promote precision oral health in the context of a learning healthcare system. J Public Health Dent. 2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.White JM, Mertz EA, Mullins JM, Even JB, Guy T, Blaga E, et al. Developing and Testing Electronic Health Record-Derived Caries Indices. Caries Res. 2019(53):650–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Chaffee BW, Cheng J, Featherstone JD. Baseline caries risk assessment and anti-caries therapy predict caries incidence. J Dent Res. 2014;93(B):190. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Featherstone JD, Domejean-Orliaguet S, Jenson L, Wolff M, Young DA. Caries risk assessment in practice for age 6 through adult. J Calif Dent Assoc. 2007;35(10):703–7, 10-3. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ramos-Gomez FJ, Crall J, Gansky SA, Slayton RL, Featherstone JD. Caries risk assessment appropriate for the age 1 visit (infants and toddlers). J Calif Dent Assoc. 2007;35(10):687–702. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Weintraub JA, Ramos-Gomez F, Jue B, Shain S, Hoover CI, Featherstone JD, et al. Fluoride varnish efficacy in preventing early childhood caries. Journal of dental research. 2006;85(2):172–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Young DA, Featherstone JD, Roth JR, Anderson M, Autio-Gold J, Christensen GJ, et al. Caries management by risk assessment: implementation guidelines. J Calif Dent Assoc. 2007;35(11):799–805. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Jenson L, Budenz AW, Featherstone JD, Ramos-Gomez FJ, Spolsky VW, Young DA. Clinical protocols for caries management by risk assessment. J Calif Dent Assoc. 2007;35(10):714–23. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ismail AI, Tellez M, Pitts NB, Ekstrand KR, Ricketts D, Longbottom C, et al. Caries management pathways preserve dental tissues and promote oral health. Community Dent Oral Epidemiol. 2013;41(1):e12–40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Walsh CJ, Gansky SA, Vaderhobli RM, Fontana M, Rechmann P, White JM. Usability testing of clinical decision support caries risk assessment tools. J Dent Res. 2015;94(A):1080. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Domejean S, Leger S, Rechmann P, White JM, Featherstone JD. How do dental students determine patients’ caries risk level using the Caries Management By Risk Assessment (CAMBRA) system? J Dent Educ. 2015;79(3):278–85. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Yansane A, Tokede O, White J, Etolue J, McClellan L, Walji M, et al. Utilization and Validity of the Dental Diagnostic System over Time in Academic and Private Practice. JDR Clin Trans Res. 2019;4(2):143–50. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Mertz E, Bolarinwa O, Wides C, Gregorich S, Simmons K, Vaderhobli R, et al. Provider Attitudes Toward the Implementation of Clinical Decision Support Tools in Dental Practice. J Evid Based Dent Pract. 2015;15(4):152–63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Mertz E, Wides C, White J. Clinician attitudes, skills, motivations and experience following the implementation of clinical decision support tools in a large dental practice. J Evid Based Dent Pract. 2017;17(1):1–12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Simmons K, Gibson S, White JM. Drivers Advancing Oral Health in a Large Group Dental Practice Organization. J Evid Based Dent Pract. 2016;16 Suppl:104–12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. Healthy People 2020: Oral Health Washington, DC: Office of Disease Prevention and Health Promotion; 2013–2014. [Available from: https://www.healthypeople.gov/2020/topics-objectives/topic/oral-health. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Health Policy Institute. How Many Dentists are in Solo Practice? Chicago, IL: American Dental Association; 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Makhija SK, Gilbert GH, Rindal DB, Benjamin P, Richman JS, Pihlstrom DJ. Dentists in practice-based research networks have much in common with dentists at large: evidence from “The Dental PBRN”. Gen Dent. 2009;57(3):270. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Kaiser Family Foundation. State Health Facts: Medicaid Coverage Rates for the Nonelderly by Age, 2016: Kaiser Commission on Medicaid and the Uninsured; 2018. [Available from: https://www.kff.org/medicaid/state-indicator/rate-by-age-3/?currentTimeframe=0&sortModel=%7B%22colId%22:%22Location%22,%22sort%22:%22asc%22%7D. [Google Scholar]

- 41.U.S. Census Bureau. American FactFinder: Community Facts: 2017 American Community Survey; Washington, DC: Department of Commerce; 2018. [Available from: https://factfinder.census.gov/faces/nav/jsf/pages/community_facts.xhtml. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Christian B, Chattopadhyay A, Kingman A, Boroumand S, Adams A, Garcia I. Oral health care services utilisation in the adult US population: Medical Expenditure Panel Survey 2006. Community dental health. 2013;30(3):161–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Cheng J, Gregorich SE, Gansky SA, Fisher-Owens SA, Kottek AM, White JM, et al. Constructing Matched Groups in Dental Observational Health Disparity Studies for Causal Effects. JDR Clin Trans Res. 2020;5(1):82–91. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.