Abstract

Introduction:

Many Canadians report decreased mental health during the COVID-19 pandemic, and concerns have been raised about possible increases in suicide. This study investigates the pandemic’s potential impact on adults’ suicide ideation.

Methods:

We compared self-reported suicide ideation in 2020 versus 2019 by analyzing data from the Survey on COVID-19 and Mental Health (11 September to 4 December 2020) and the 2019 Canadian Community Health Survey. Logistic regression was conducted to determine which populations were at higher risk of suicide ideation during the pandemic.

Results:

The percentage of adults reporting suicide ideation since the pandemic began (2.44%) was not significantly different from the percentage reporting suicide ideation in the past 12 months in 2019 (2.73%). Significant differences in the prevalence of recent suicide ideation in 2020 versus 2019 also tended to be absent in the numerous sociodemographic groups we examined. Risk factors of reporting suicide ideation during the pandemic included being under 65 years, Canadian-born or a frontline worker; reporting pandemic-related income/job loss or loneliness/isolation; experiencing a lifetime highly stressful/traumatic event; and having lower household income and educational attainment.

Conclusion:

Evidence of changes in suicide ideation due to the pandemic were generally not observed in this research. Continued surveillance of suicide and risk/protective factors is needed to inform suicide prevention efforts.

Keywords: COVID-19 pandemic, coronavirus, suicide ideation, Canadian adults, public health

Highlights

Recent suicide ideation was not significantly different in 2020 versus 2019 in the overall population, nor in almost every sociodemographic group examined.

Some individuals were more likely than others to report contemplating suicide since the pandemic began: adults under 65 years old; Canadian-born people; frontline workers; those with a high school or lower education level and lower household income; individuals who had experienced a highly stressful/ traumatic event in their lifetime; and people who lost their job/ income or experienced loneliness/ isolation due to the pandemic.

Introduction

Since early in the COVID-19 pandemic, concerns have been raised about the potential impacts of the pandemic and the unintended consequences of public health interventions on the mental health of individuals and, in particular, on suicide-related outcomes.1-3 Indeed, mental health helplines in Canada have had a substantial increase in demand during the pandemic compared to previous years.4-6 Available data from 19 Canadian police services reveal more mental health–related calls for service in the first eight months of the pandemic compared to the same months in 2019.7 Surveys have found that as many as half of Canadians report that their mental health had worsened since the pandemic began,8-14 and around one-fifth of Canadians screened positive for anxiety, depression or posttraumatic stress disorder during Fall 2020.15

Other risk factors of suicide have also increased. For instance, the higher unemployment rate due to the pandemic16 was projected to lead to more suicide deaths in Canada and globally.17,18 Alcohol consumption has also been implicated in suicide,19-21 and while the majority of Canadians surveyed report no changes in their alcohol use during the pandemic, a portion report increasing their consumption.11,22-28

With physical distancing guidelines limiting in-person social interactions to reduce the spread of COVID-19, loneliness has become relatively common, with 4 in 10 adults in Canada reporting feelings of loneliness or isolation due to the pandemic in Fall 2020.15 This is a concern because a sense of belonging and connectedness with others is considered to be a basic psychological need and an important aspect of positive mental health.29,30 Furthermore, loneliness has been associated with subsequent suicide ideation and suicide-related behaviour.31 More generally, evidence of higher suicide mortality (at least in some subpopulations) has been found in studies investigating the impact of previous infectious disease–related public health emergencies.32

Thus far, there have been no signs of higher numbers of suicide deaths or self-harm hospitalizations/emergency department visits in Canada during the pandemic.33,34 Higher than expected suicide mortality in the initial months of the pandemic was also typically not observed in analyses of data from 21 countries, with some places even showing lower than expected suicide mortality.35 While data from numerous Canadian police services show more mental health–related calls for service during the pandemic than in 2019, higher numbers of calls for service for suicide/attempted suicide have not been reported.7

Suicide ideation in Canada has been assessed during the pandemic in three surveys by the Canadian Mental Health Association (CMHA) and researchers at the University of British Columbia. Respondents were asked if they had experienced suicidal thoughts/feelings as a result of the COVID-19 pandemic in the past two weeks. The percentage indicating “yes” ranged from 6% in May 2020, to 10% in September 2020 and 8% in January 2021.9-11 In contrast, the 2016 Canadian Community Health Survey (CCHS) recorded 2.5% of Canadians reporting seriously contemplating suicide in the past 12 months.36 This has led some to conclude that suicide ideation has become more prevalent during the pandemic.24,37

However, these comparisons are not ideal given the different ways the surveys assessed suicide ideation. For instance, the prevalence of suicide ideation during the pandemic could be overestimated as people may be less likely to report seriously contemplating suicide versus experiencing thoughts or feelings related to suicide that may be more fleeting and/or ambivalent. Alternatively, the prevalence of suicide ideation during the pandemic may be greater if people described their experiences since the beginning of the pandemic (not just the past two weeks). Furthermore, estimates of suicide ideation during the pandemic were compared to data from 2016, but pre-pandemic estimates from more recent data would be a more appropriate baseline for determining the pandemic’s potential impact.

Fortunately, the 2019 Canadian Community Health Survey (CCHS)38 and the 2020 Survey on COVID-19 and Mental Health (SCMH)39 both assessed suicide ideation. The similarly worded questions about suicide ideation and the relatively large sample sizes in these two surveys allowed us to compare the prevalence of self-reported serious contemplation of suicide before the pandemic versus during it in the overall population and in various sociodemographic groups.

Because other surveys suggested that feelings/thoughts of suicide were more prevalent in certain population subgroups during the pandemic (e.g. young adults; those who identify as LGBTQ2+; those with a pre-existing mental health condition; parents with children under 18 years living at home),24,37 we investigated how the likelihood of seriously contemplating suicide during the pandemic differed by numerous sociodemographic characteristics and by potentially high-risk experiences (e.g. being a frontline worker, experiencing income/job loss or loneliness/isolation due to the pandemic).15,31,40-42 We also stratified findings by gender as some surveys suggest that the pandemic has had a more negative impact on the mental health of women8,11,43 and because suicide-related outcomes often differ between males and females.44-46

Methods

Data and participants

To obtain estimates of suicide ideation before the COVID-19 pandemic, we analyzed data from the 2019 CCHS – Annual Component.38 Respondents were surveyed from 2 January to 24 December 2019. The target population was people aged 12 years and older living in the provinces and territories.38 The CCHS excludes full-time members of the Canadian forces and people living on First Nations reserves/settlements, in foster homes, in two remote health regions in Quebec or in institutions; these exclusions represent less than 3% of the population.38 Statistics Canada used the Labour Force Survey sampling frame to sample adults in the provinces for the 2019 CCHS.47 After a dwelling is sampled, an adult living in that dwelling is selected as the respondent.38 Respondents complete the CCHS voluntarily via computer-assisted personal interviews or telephone interviews.38 We only analyzed data from adults in the 2019 CCHS as individuals under 18 years were excluded from the 2020 SCMH.39 Moreover, as CCHS data from respondents living in the territories are only released by Statistics Canada after two consecutive years of data collection, we were only able to analyze 2019 CCHS data from individuals living in the provinces. The response rate for adults in the 2019 CCHS was 54.9%.

To obtain estimates of suicide ideation during the COVID-19 pandemic, we analyzed data from the 2020 SCMH.39 Respondents were surveyed from 11 September to 4 December 2020, and the target population was people aged 18years and older living in the provinces and the three territorial capitals.39 The 2020 SCMH frame was stratified by province; a simple random sample of dwellings was selected within each province and territorial capital from the Dwelling Universe File, and an adult within each dwelling was then sampled to participate.39 The sampling frame for the 2020 SCMH excluded people living in non-capital cities in the territories, in institutions, in collective/unmailable/inactive/vacant dwellings and on reserves.39 Respondents completed the 2020 SCMH voluntarily via electronic questionnaire or computer-assisted telephone interview.39 The total number of respondents in the 2020 SCMH was 14689, a response rate of 53.3%. We analyzed 2020 SCMH data from the 12344 respondents who agreed to share their information with Public Health Agency of Canada (PHAC).

Measures

Suicide ideation

Lifetime suicide ideation was assessed in both surveys by asking respondents “Have you ever seriously contemplated suicide?”. To assess recent suicide ideation, those who reported seriously contemplating suicide were asked “Has this happened in the past 12 months?” in the 2019 CCHS and “Have you seriously contemplated suicide since the COVID-19 pandemic began?” in the 2020 SCMH.

Sociodemographic characteristics and experiences

A number of sociodemographic variables were included in both surveys, including age, gender, household income, immigrant status, racialized group member, educational attainment, place of residence (population centre, rural area), presence of children at home who are less than 18 years (yes, no) and province/territorial capital.

We coded individuals into three age groups: young adults (18–34 years), middle-aged adults (35–64 years) and older adults (65 years and older).

Gender identity was assessed by asking respondents “What is your gender?”, with “male,” “female” and “or please specify” as response options.

We coded household income into tertiles, representing low-income, middle-income and high-income households.

For the immigrant status variable, immigrants included landed immigrants and non-permanent residents, and non-immigrants included those born in Canada.

Individuals classified as a visible minority or who identified as Indigenous were coded as a racialized group member, while individuals who identified only as White were coded as non-racialized.

We coded highest educational attainment into two groups: respondents with a high school education or less, and respondents with a post-secondary certificate/degree/diploma.

Some potentially high-risk experiences that were only included in the 2020 SCMH were also of interest. Respondents were asked “Have you experienced any of the following impacts due to the COVID-19 pandemic?”, with “Loss of job or income” (yes, no) and “Feelings of loneliness or isolation” (yes, no) listed among other experiences. The 2020 SCMH respondents were also asked “Have you ever experienced a highly stressful or traumatic event during your life?”, with “yes” and “no” as response options.

The 2020 SCMH also asked respondents if during the past 7 days they were considered an “essential worker” (yes, no, don’t know), defined as “an individual who works in a service, facility or in an activity that is necessary to preserving life, health, public safety and basic societal functions of Canadians.” Respondents were also asked if they were considered a “frontline worker” (yes, no, don’t know), defined as “an individual who has the potential to come in direct contact with COVID-19 by assisting those who have been diagnosed with the virus,” with police officers, doctors, nurses, firefighters and paramedics listed as examples. We coded respondents as frontline workers if they answered “yes” to being a frontline worker and as essential non-frontline workers if they only answered “yes” to being an essential worker; the remaining respondents we coded as having an “other” work status.

Analysis

We used SAS Enterprise Guide version 7.1 (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC, USA) to conduct analyses. All estimates were weighted by sampling weights provided by Statistics Canada so that the complex survey design was accounted for and the results were representative. We used bootstrap weights to estimate the coefficients of variation, standard errors and 95% confidence intervals. Clopper–Pearson confidence intervals were obtained when estimating the proportion of individuals reporting suicide ideation so that adequate coverage was obtained even when proportions were small.48 We identified statistically significant results when p-values were under 0.05.

The percentage of individuals reporting recent suicide ideation in 2019 and in 2020 was estimated overall and for each sociodemographic group. Chi-square tests were conducted using PROC SURVEYFREQ to determine whether the 2019 versus 2020 estimates differed significantly. The same analyses were also conducted for lifetime suicide ideation. Separate univariate logistic regression analyses for 2019 and 2020 were conducted to examine how the likelihood of reporting recent suicide ideation differed by sociodemographic characteristic. As the 2019 CCHS data did not include responses from individuals living in the territories, data from 2020 SCMH respondents in the territorial capitals were excluded from these analyses so that we compared similar groups of individuals across the two surveys.

The percentage of individuals reporting recent suicide ideation by potential high-risk experiences (i.e. pandemic-related job/income loss; pandemic-related loneliness/isolation; lifetime highly stressful/traumatic event; frontline/essential worker) was also estimated. Univariate logistic regression analyses were conducted to examine how the likelihood of reporting recent suicide ideation during the pandemic differed by experience. As these potential high-risk experiences were only assessed in the 2020 SCMH, we used data from 2020 SCMH respondents living in the provinces and territorial capitals in analyses involving those variables.

All analyses were also stratified by gender. Individuals who specified a different gender identity beyond “male” or “female” were not included in gender-stratified analyses because of insufficient sample sizes (<1.00%).

Results

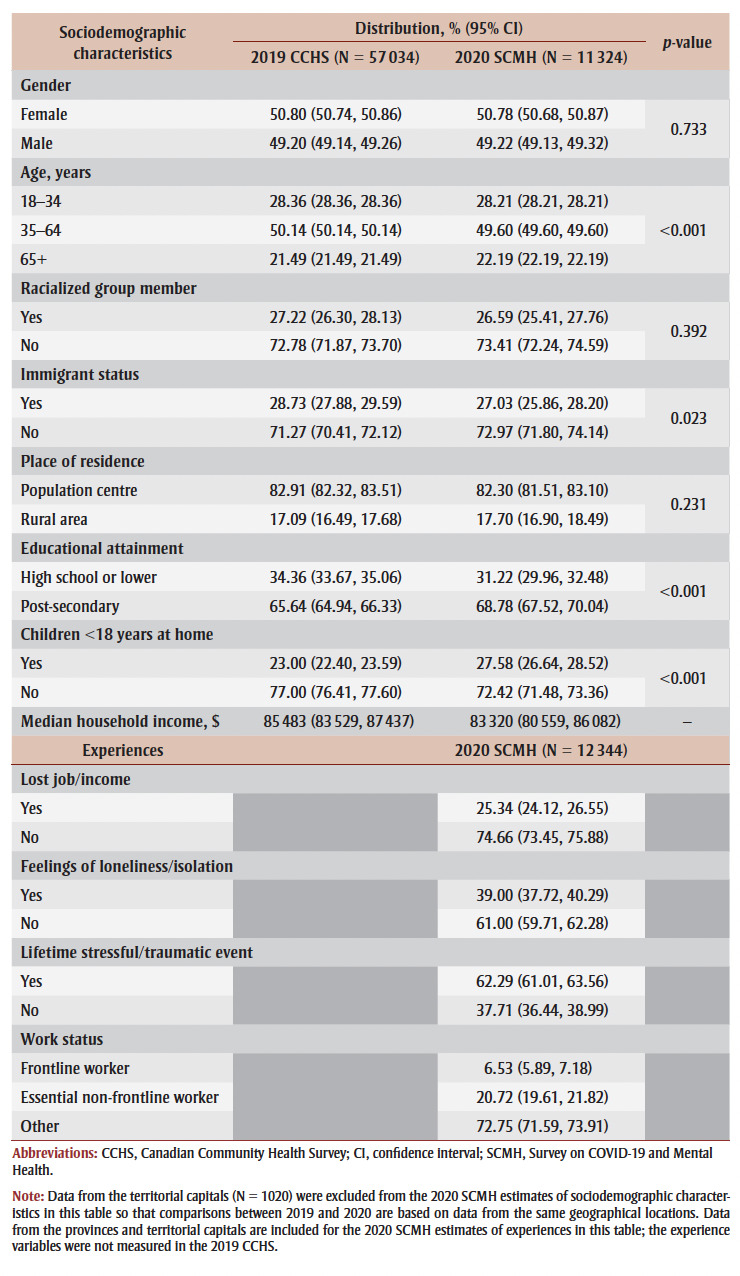

The distribution of the sociodemographic characteristics and experiences in the 2019 CCHS and the 2020 SCMH are shown in Table 1.

Table 1. Sociodemographic characteristics and experiences.

|

Suicide ideation before versus during the pandemic

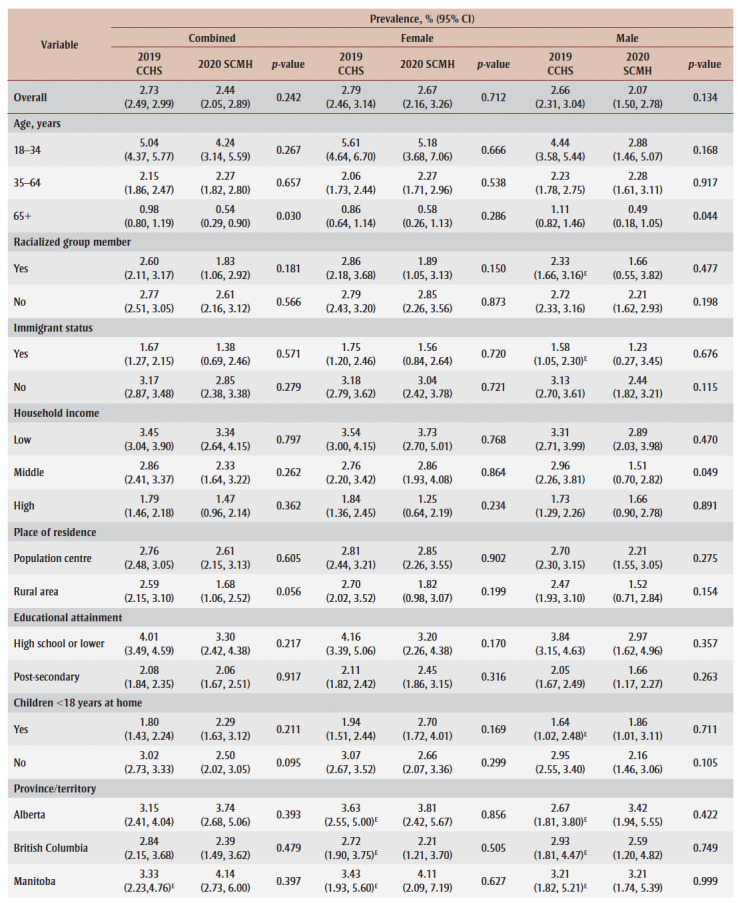

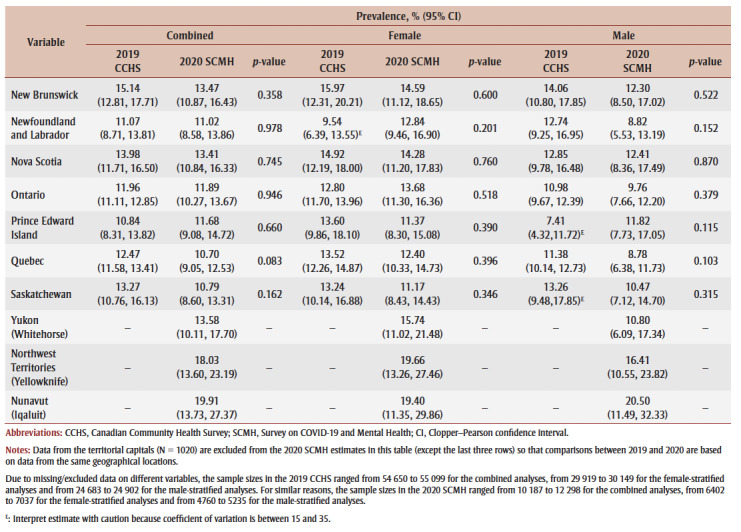

Overall, the percentage of adults in Fall 2020 who reported seriously contemplating suicide since the COVID-19 pandemic began was 2.44%, which did not differ significantly from the 2.73% who reported seriously contemplating suicide in the past 12 months in 2019 (see Table 2). Significant differences in the percentage of recent suicide ideation in 2020 versus 2019 were found in almost none of the sociodemographic groups examined. The percentage of males aged 65 years and older, males with middle household income and individuals living in Quebec who reported seriously contemplating suicide since the pandemic began was significantly lower than the percentage who reported seriously contemplating suicide in the past 12months in 2019. However, it is unclear whether recent suicide ideation was actually lower in 2020 in these groups or if these results were due to the shorter timeframe that was asked about in 2020 versus 2019 (i.e. since the pandemic began 6–8 months ago versus the past 12 months).

Table 2. Prevalence of recent suicide ideation in 2019 versus 2020, overall and stratified by gender.

|

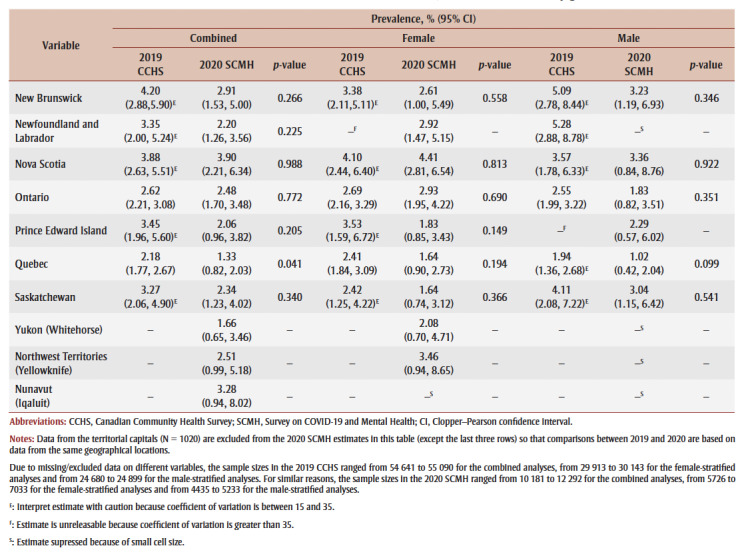

Significant differences also tended to be absent when we examined lifetime suicide ideation (see Table 3). Specifically, the percentage of adults who reported ever seriously contemplating suicide did not differ significantly in 2019 (12.58%) compared with Fall 2020 (12.21%). Moreover, no significant differences in lifetime suicide ideation from 2019 to 2020 were found in any of the sociodemographic groups, with the one exception being females with high household income who more frequently reported ever seriously contemplating suicide in Fall 2020 (12.97%) than in 2019 (9.44%).

Table 3. Prevalence of lifetime suicide ideation in 2019 versus 2020, overall and stratified by gender.

|

Sociodemographic characteristics and experiences associated with suicide ideation during the pandemic

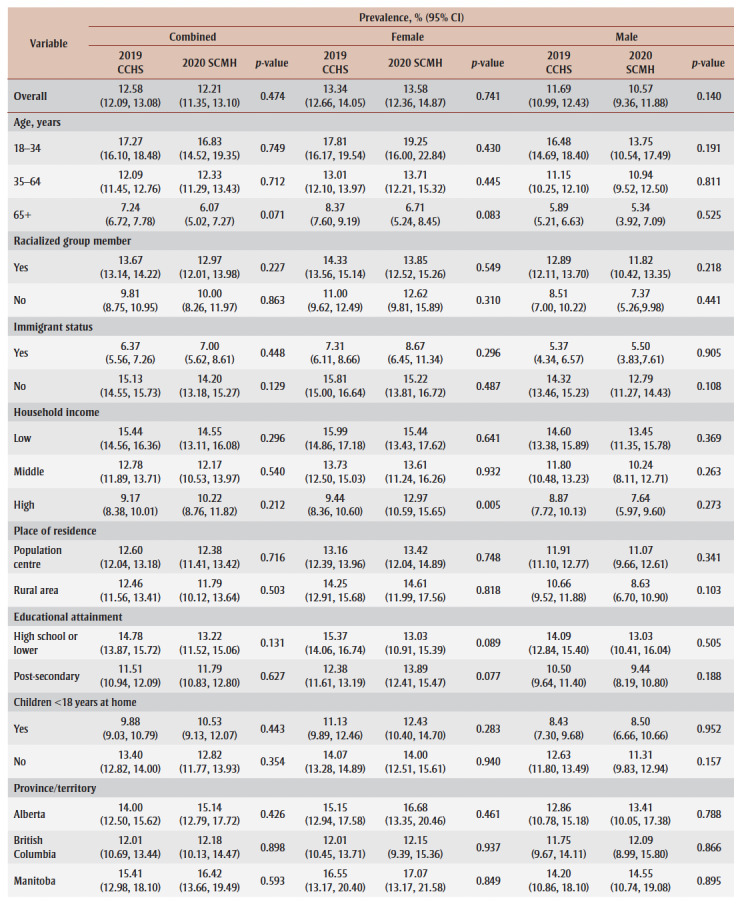

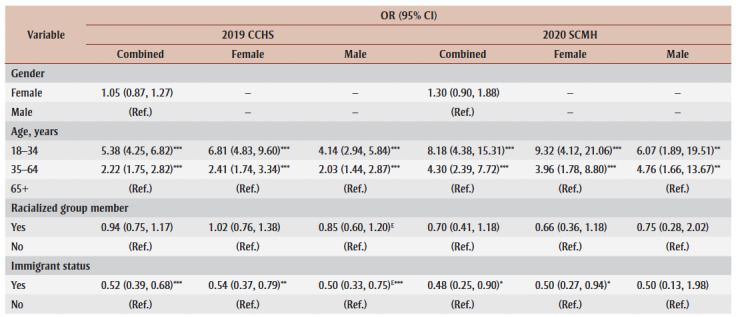

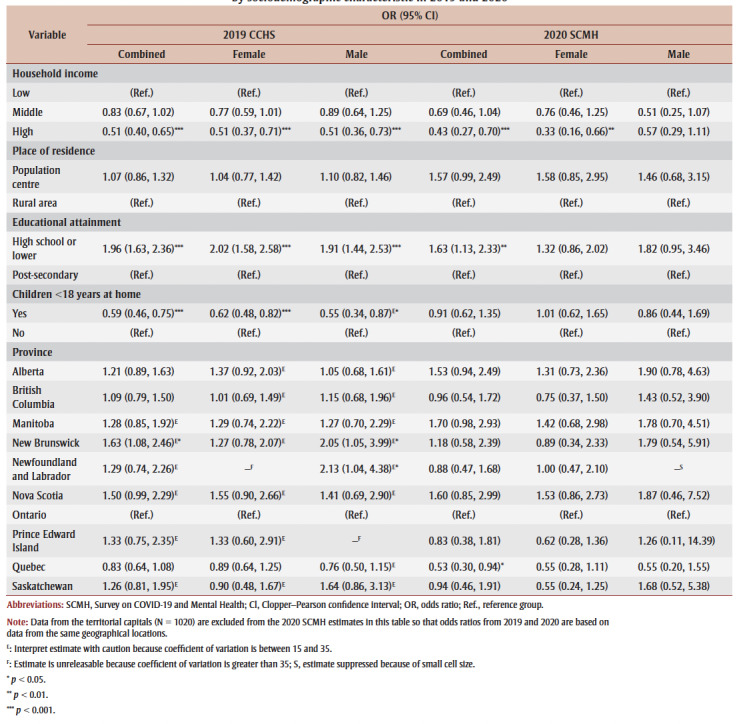

Table 4 presents logistic regression results examining the likelihood of reporting serious suicide contemplation since the pandemic began across numerous sociodemographic characteristics and experiences.

Table 4. Univariate logistic regression analyses comparing likelihood of reporting recent suicide ideation by sociodemographic characteristic in 2019 and 2020.

|

Overall, females (2.67%) were not significantly more likely to report recent suicide ideation than males (2.07%) during the pandemic. Adults aged 18 to 34 years (4.24%) and 35 to 64 years (2.27%) were significantly more likely to report recent suicide ideation than those aged 65 years and older (0.54%). Individuals born in Canada (2.85%) were significantly more likely to report recent suicide ideation than individuals who immigrated to Canada (1.38%).

Adults with low household income (3.34%) were significantly more likely to report recent suicide ideation than those with high household income (1.47%). Individuals with a high school education or lower (3.30%) were significantly more likely to report recent suicide ideation than individuals with a post-secondary education (2.06%). Quebec (1.33%) was the only province where recent suicide ideation significantly differed from that in Ontario (2.48%).

Significant differences by racialized group membership, place of residence and presence of children at home were not observed.

As seen in Table 4, similar patterns tended to be present in 2019. The only exceptions were individuals with children at home being less likely to report recent suicide ideation than those without children at home in 2019, and the prevalence of recent suicide ideation being significantly different in New Brunswick (but not Quebec) compared to Ontario in 2019.

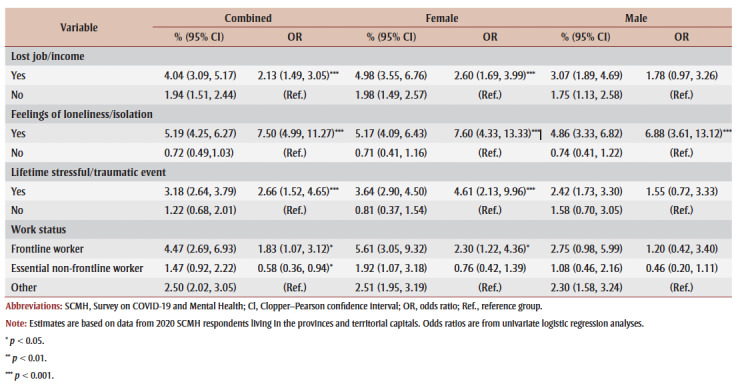

Of the variables only measured in the 2020 SCMH (see Table 5 for logistic regression results), recent suicide ideation was significantly more likely among individuals who reported pandemic-related job/income loss (4.04%) versus those who did not (1.94%), and among individuals who reported having feelings of pandemic-related loneliness/isolation (5.19%) versus those who did not (0.72%). Moreover, seriously contemplating suicide since the pandemic began was more likely among those who reported experiencing a highly stressful/traumatic event during their life (3.18%) versus those who did not (1.22%), and among frontline workers (4.47%) versus other work status (2.50%).

Table 5. Prevalence and likelihood of reporting recent suicide ideation by potential high-risk sociodemographic characteristics and experiences during the COVID-19 pandemic, SCMH 2020.

|

All of these differences remained significant for females in the gender-stratified analyses, but only the difference between those who did versus did not report loneliness/isolation remained significant for males.

Discussion

The COVID-19 pandemic has had negative consequences for the physical and mental health of many Canadians. Despite some risk factors of suicide increasing during the pandemic (e.g. unemployment),16-18 we did not find evidence for recent suicide ideation becoming more prevalent in the current study. This is consistent with preliminary surveillance data of other suicide-related outcomes in Canada, including suicide mortality, self-harm hospitalizations/emergency department visits and police calls for service concerning suicide.7,33,34

Previous surveys finding higher prevalence of suicide ideation than what we observed could be due to differences in how suicide ideation was asked about in those surveys (i.e. experiencing suicidal thoughts/feelings) compared to the CCHS and the SCMH (i.e. seriously contemplating suicide).9-11

There are a number of plausible explanations for why projected increases in suicide-related outcomes have generally not been observed thus far. Investments in mental health services as well as financial support for individuals negatively impacted by lockdowns may have buffered the pandemic’s impact on the most severe and acute experiences of distress.35,49 People experiencing worse mental health during the pandemic may be accessing help before suicide is seriously considered or attempted. It is also possible that Fall 2020 may be too early to detect the pandemic’s impact on suicide as some research suggests that there can be a delay in the effect of large-scale events on suicide-related outcomes.50,51 This highlights the importance of continued suicide surveillance to understand how the pandemic might impact suicide-related outcomes in the short- and long-term in Canada.52,53

Although differences in the prevalence of suicide ideation in 2020 versus 2019 were largely not observed in the overall population or in specific sociodemographic groups, we did find that some people were more likely than others to report seriously contemplating suicide since the pandemic began. Those at higher risk of recent suicide ideation before the pandemic also tended to be at higher risk during the pandemic, including individuals under 65years old, those born in Canada and those with lower household income and educational attainment. These results provide further evidence for the “healthy immigrant effect,”54 and the link between socioeconomic status and suicide.55

Of note, having children at home was a protective factor against suicide ideation before but not during the pandemic, which may hint at the difficulties associated with increased childcare responsibilities and work-life balance experienced by parents/guardians due to school/daycare closures, isolation from extended family, and other reasons.

Given previous research findings on associations between suicide-related outcomes and loneliness, unemployment/socioeconomic status and stressful life events,31,42,55,56 it is not surprising that suicide ideation during the pandemic was more common among individuals who reported pandemic-related job/income loss and loneliness/isolation, and those who had experienced a highly stressful/traumatic event during their life.

Finally, frontline workers were more likely to report seriously considering suicide since the pandemic began compared to individuals with other work statuses. This could be due to overall declines in mental health due to the unique demands placed on this group during the pandemic,41,57 and/or it could reflect the elevated risk of suicide among some frontline workers that was observed before the pandemic.40,58 Regardless, these findings identify high-risk characteristics and experiences that targeted mental health promotion and suicide prevention efforts may want to focus on.

Strengths and limitations

This study contributes to suicide surveillance in Canada by examining suicide ideation before versus during the COVID-19 pandemic using representative data from the relatively large and recent samples of the 2019 CCHS and the 2020 SCMH. Our estimates based on surveys with probability sampling answer recent calls for better quality estimates of population mental health in Canada during the pandemic.59 We investigated differences in suicide ideation in 2020 versus 2019 in numerous sociodemographic groups, and examined how various characteristics and experiences were associated with suicide ideation both before and during the pandemic.

However, caution is warranted when interpreting the results of this study due to methodological differences between the 2019 CCHS and 2020 SCMH data. The 2019 CCHS had a full year for data collection, compared to approximately three months for the 2020 SCMH. Nevertheless, when we restricted analyses to data from the same time of the year, there was not a significant difference in Fall 2019 versus Fall 2020 in the overall prevalence of recent suicide ideation (2.81% versus 2.44%, chi-square test p-value = 0.267) or in the overall prevalence of lifetime suicide ideation (12.96% versus 12.21%, chi-square test p-value = 0.256).

The 2019 CCHS asked about serious suicide contemplation over the past 12months whereas the 2020 SCMH asked about serious suicide contemplation “since the COVID-19 pandemic began,” which is closer to a six- to eight-month recall period. While it is possible that this shorter time period may explain why the prevalence of recent suicide ideation was not higher in 2020, it is unlikely as we found largely similar results when lifetime suicide ideation was examined.

Other differences between surveys that could have affected the responses and the estimates we obtained include the sampling frames, how some of the sociodemographic factors were distributed and the mode of data collection (i.e. 2020 SCMH respondents could complete the survey online on their own; this data collection method was associated with a lower likelihood of agreeing to share data with PHAC).

It is possible that other differences between respondents who did versus did not agree to share their data, or who did versus did not respond to the survey, could have biased estimates. In addition, respondents’ household income in the 2019 CCHS was based on tax data, self-reported income and imputed income amounts, while it was only self-reported in the 2020 SCMH. Moreover, the presence of children under 18 years at home was measured by different variables in the two surveys.

We were not able to examine additional important sociodemographic characteristics (e.g. marital status, LGBTQ2+ status)60,61 as they were not measured in the 2020 SCMH. We solely examined univariate associations in the logistic regression analyses; some of the associations found between suicide ideation and high-risk experiences in Fall 2020 could be accounted for by sociodemographic factors.

Our study only included adults aged 18 and over; additional research is needed to examine how suicide-related outcomes among youth in Canada might have changed due to the pandemic. Given data availability issues, analyses comparing suicide ideation in 2020 to 2019 were restricted to the provinces. Lastly, to maximize statistical power, we adopted a lenient alpha level of 0.05 to identify statistically significant results. Given the numerous comparisons made in this research, it is possible that some significant findings are false positives.

Conclusion

The current research suggests that, in general, the prevalence of suicide ideation in 2020 has neither increased nor decreased compared to 2019. It is possible that suicide-related outcomes may change as the COVID-19 pandemic continues and as Canada recovers. Continued surveillance of suicide and risk/protective factors (e.g. through analyzing data from the 2021 SCMH)62 will be important for informing suicide prevention efforts.

Conflicts of interest

The authors have no conflicts of interest.

Authors’ contributions and statement

LL conceived the project.

LL, CC and RD decided on the analytic approach.

LL conducted the statistical analyses.

LL, CC and RD interpreted the results.

CC and RD drafted and revised sections of the manuscript.

LL, CC and RD provided feedback on manuscript drafts.

The content and views expressed in this article are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect those of the Government of Canada.

References

- Gunnell D, Appleby L, Arensman E, et al, et al. Suicide risk and prevention during the COVID-19 pandemic. Lancet Psychiatry. 2020;7((6)):468–71. doi: 10.1016/S2215-0366(20)30171-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holmes EA, O’Connor RC, Perry VH, et al, et al. Multidisciplinary research priorities for the COVID-19 pandemic: a call for action for mental health science. Lancet Psychiatry. 2020;7((6)):547–60. doi: 10.1016/S2215-0366(20)30168-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reger MA, Stanley IH, Joiner TE, et al. Suicide mortality and coronavirus disease 2019—a perfect storm. JAMA Psychiatry. 2020;77((11)):1093–4. doi: 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2020.1060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krugel L, et al. CTV News. Toronto(ON): ‘Dealing with a lot:’ suicide crisis calls mount during COVID-19 pandemic [Internet] Available from: https://www.ctvnews.ca/health/coronavirus/dealing-with-a-lot-suicide-crisis-calls-mount-during-covid-19-pandemic-1.5215056. [Google Scholar]

- Wright T, et al. CTV News. Toronto(ON): Crisis lines face volunteer, cash crunch even as COVID-19 drives surge in calls [Internet] Available from: https://www.ctvnews.ca/health/coronavirus/crisis-lines-face-volunteer-cash-crunch-even-as-covid-19-drives-surge-in-calls-1.4912975. [Google Scholar]

- Yousif N, et al. Toronto Star. Toronto(ON): 4 million cries for help: calls to Kids Help Phone soar amid pandemic [Internet] Available from: https://www.thestar.com/news/gta/2020/12/13/4-million-cries-for-help-calls-to-kids-help-phone-soar-amid-pandemic.html. [Google Scholar]

- Statistics Canada. Ottawa(ON): Selected police-reported crime and calls for service during the COVID-19 pandemic, March to October 2020 [Internet] Available from: https://www150.statcan.gc.ca/n1/daily-quotidien/210127/dq210127c-eng.htm. [Google Scholar]

- Angus Reid Institute. Vancouver(BC): Worry, gratitude & boredom: as COVID-19 affects mental, financial health, who fares better; who is worse. Available from: http://angusreid.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/04/2020.04.27_COVID-mental-health.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- CMHA. Toronto(ON): Mental health impacts of COVID-19: wave 2 [Internet] pp. wave 2 [Internet]–4. Available from: https://cmha.ca/wp-content/uploads/2020/12/CMHA-UBC-wave-2-Summary-of-Findings-FINAL-EN.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- CMHA. Toronto(ON): Summary of findings; pp. round 3 [Internet]–4. Available from: https://cmha.ca/wp-content/uploads/2021/05/CMHA-UBC-Round-3-Summary-of-Findings-FINAL-EN.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- Jenkins EK, McAuliffe C, Hirani S, et al, et al. A portrait of the early and differential mental health impacts of the COVID-19 pandemic in Canada: findings from the first wave of a nationally representative cross-sectional survey. Prev Med. 2021:106333–4. doi: 10.1016/j.ypmed.2020.106333. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ipsos. Paris(FR): One year of COVID-19: Ipsos survey for The World Economic Forum [Internet] pp. Ipsos survey for The World Economic Forum [Internet]–4. Available from: https://www.ipsos.com/sites/default/files/ct/news/documents/2021-04/wef_-_expectations_about_when_life_will_return_to_pre-covid_normal_-final.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- Mental Health Commission of Canada. Ottawa(ON): Canadians report an increase in feeling stressed regularly or all the time now compared to one month before COVID-19 [Internet] Available from: https://www.mentalhealthcommission.ca/sites/default/files/2020-05/nanos_covid_may_2020.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- Statistics Canada. Ottawa(ON): Canadians health and COVID-19, by age and gender, monthly estimates [Internet] Available from: [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Statistics Canada. Ottawa(ON): Survey on COVID- 19 and mental health, September to December 2020 [Internet] Available from: https://www150.statcan.gc.ca/n1/daily-quotidien/210318/dq210318a-eng.htm. [Google Scholar]

- Statistics Canada. Ottawa(ON): Labour force survey, April 2021 [Internet] Available from: https://www150.statcan.gc.ca/n1/daily-quotidien/210507/dq210507a-eng.htm. [Google Scholar]

- Kawohl W, Nordt C, et al. COVID-19, unemployment, and suicide. Lancet Psychiatry. 2020;7((5)):389–90. doi: 10.1016/S2215-0366(20)30141-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McIntyre RS, Lee Y, et al. Projected increases in suicide in Canada as a consequence of COVID-19. psychres. 2020:113104–90. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2020.113104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaplan MS, McFarland BH, Huguet N, et al, et al. Acute alcohol intoxication and suicide: a gender-stratified analysis of the National Violent Death Reporting System. Inj Prev. 2013:38–43. doi: 10.1136/injuryprev-2012-040317. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Orpana H, Giesbrecht N, Hajee A, Kaplan MS, et al. Alcohol and other drugs in suicide in Canada: opportunities to support prevention through enhanced monitoring. Inj Prev. 2021;27((2)):194–200. doi: 10.1136/injuryprev-2019-043504. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pompili M, Serafini G, Innamorati M, et al, et al. Suicidal behavior and alcohol abuse. Int J Env Res Public Health. 2010;7((4)):1392–431. doi: 10.3390/ijerph7041392. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- CCSA. Ottawa(ON): COVID-19 and increased alcohol consumption: NANOS poll summary report [Internet] Available from: https://www.ccsa.ca/sites/default/files/2020-04/CCSA-NANOS-Alcohol-Consumption-During-COVID-19-Report-2020-en.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- CCSA. Ottawa(ON): Boredom and stress drives increased alcohol consumption during COVID-19: NANOS poll summary report [Internet] pp. NANOS poll summary report [Internet]–431. Available from: https://ccsa.ca/sites/default/files/2020-06/CCSA-NANOS-Increased-Alcohol-Consumption-During-COVID-19-Report-2020-en_0.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- CAMH. Toronto(ON): Despair and suicidal feelings deepen as pandemic wears on: new national survey finds Canadians’ mental health eroding [Internet] Available from: https://cmha.ca/news/despair-and-suicidal-feelings-deepen-as-pandemic-wears-on. [Google Scholar]

- MHRC. Toronto(ON): Mental health during COVID-19 outbreak poll 2 [Internet] Available from: https://static1.squarespace.com/static/5f31a311d93d0f2e28aaf04a/t/5f866fab9ec4b03a7a306890/1602645935216/MHRC+Poll+2+MH+Final+Public+Release+Oct+1+2020.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- Rotermann M, et al. Statistics Canada. Ottawa(ON): Canadians who report lower self-perceived mental health during the COVID-19 pandemic more likely to report increased use of cannabis, alcohol and tobacco [Internet] Available from: https://www150.statcan.gc.ca/n1/pub/45-28-0001/2020001/article/00008-eng.htm. [Google Scholar]

- Statistics Canada. Ottawa(ON): Alcohol and cannabis use during the pandemic: Canadian Perspectives Survey Series 6 [Internet] Available from: https://www150.statcan.gc.ca/n1/daily-quotidien/210304/dq210304a-eng.htm. [Google Scholar]

- Statistics Canada. Ottawa(ON): Canadian Perspectives Survey Series 2: monitoring the effects of COVID-19, May 2020 [Internet] Available from: https://www150.statcan.gc.ca/n1/daily-quotidien/200604/dq200604b-eng.htm. [Google Scholar]

- Orpana H, Vachon J, Dykxhoorn J, McRae L, Jayaraman G, et al. Monitoring positive mental health and its determinants in Canada: the development of the Positive Mental Health Surveillance Indicator Framework. Health Promot Chronic Dis Prev Can. 2016:1–10. doi: 10.24095/hpcdp.36.1.01. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ryan RM, Deci EL, et al. Self-determination theory and the facilitation of intrinsic motivation, social development, and well-being. Am Psychol. 2000;55((1)):68–78. doi: 10.1037//0003-066x.55.1.68. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McClelland H, Evans JJ, Nowland R, Ferguson E, O’Connor RC, et al. Loneliness as a predictor of suicidal ideation and behaviour: a systematic review and meta-analysis of prospective studies. J Affect Disord. 2020:880–96. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2020.05.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zortea TC, Joyce M, et al, et al. The impact of infectious disease-related public health emergencies on suicide, suicidal behavior, and suicidal thoughts: a systematic review. Crisis. 2020:1–14. doi: 10.1027/0227-5910/a000753. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- CIHI. Ottawa(ON): 2021. Unintended consequences of COVID-19: impacts on self-harm behaviour; pp. impacts on self–harm behaviour. [Google Scholar]

- Statistics Canada. Ottawa(ON): Selected grouped causes of death, by week [Internet] Available from: [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Pirkis J, John A, Shin S, et al, et al. Suicide trends in the early months of the COVID-10 pandemic: an interrupted time-series analysis of preliminary data from 21 countries. Lancet Psychiatry. 2021;8((7)):579–88. doi: 10.1016/S2215-0366(21)00091-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- PHAC. Ottawa(ON): Suicide in Canada: key statistics (infographic) [Internet] Available from: https://www.canada.ca/en/public-health/services/publications/healthy-living/suicide-canada-key-statistics-infographic.html. [Google Scholar]

- CAMH. Toronto(ON): Warning signs: more Canadians thinking about suicide during pandemic [Internet] Available from: https://cmha.ca/news/warning-signs-more-canadians-thinking-about-suicide-during-pandemic. [Google Scholar]

- Statistics Canada. Ottawa(ON): Canadian Community Health Survey - Annual Component (CCHS): detailed information for 2019 [Internet] Available from: https://www23.statcan.gc.ca/imdb/p2SV.pl?Function=getSurvey&Id=1208978. [Google Scholar]

- Statistics Canada. Ottawa(ON): Survey on COVID- 19 and Mental Health (SCMH): detailed information for September to December 2020 [Internet] Available from: https://www23.statcan.gc.ca/imdb/p2SV.pl?Function=getSurvey&Id=1283036. [Google Scholar]

- Dutheil F, Aubert C, Pereira B, et al, et al. Suicide among physicians and health-care workers: a systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS One. 2019;14((12)):e0226361–88. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0226361. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- The Centre. Carlton(AU): 2020. Moral stress amongst healthcare workers during COVID-19: a guide to moral injury; pp. a guide to moral injury–88. [Google Scholar]

- Milner A, Page A, LaMontagne AD, et al. Cause and effect in studies on unemployment, mental health and suicide: a meta-analytic and conceptual review. Psychol Med. 2014;44((5)):909–17. doi: 10.1017/S0033291713001621. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Findlay L, Arim R, et al. Statistics Canada. Ottawa(ON): Canadians report lower self-perceived mental health during the COVID-19 pandemic [Internet] Available from: https://www150.statcan.gc.ca/n1/pub/45-28-0001/2020001/article/00003-eng.htm. [Google Scholar]

- Fox KR, Millner AJ, Mukerji CE, Nock MK, et al. Examining the role of sex in self-injurious thoughts and behaviors. Clin Psychol Rev. 2018:3–11. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2017.09.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miranda-Mendizabal A, s-Badell O, et al, et al. Gender differences in suicidal behavior in adolescents and young adults: systematic review and meta-analysis of longitudinal studies. Int J Public Health. 2019:265–83. doi: 10.1007/s00038-018-1196-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- PHAC. Ottawa(ON): Suicide in Canada: key statistics (infographic) [Internet] Available from: https://www.canada.ca/en/public-health/services/publications/healthy-living/suicide-canada-key-statistics-infographic.html. [Google Scholar]

- Statistics Canada. Ottawa(ON): Methodology of the Canadian Labour Force Survey. [Google Scholar]

- Clopper CJ, Pearson ES, et al. The use of confidence or fiducial limits illustrated in the case of the binomial. Biometrika. 1934;26((4)):404–13. [Google Scholar]

- PHAC. Ottawa(ON): The Federal Framework for Suicide Prevention – Progress Report 2020 [Internet] Available from: https://www.canada.ca/en/public-health/services/publications/healthy-living/2020-progress-report-federal-framework-suicide-prevention.html. [Google Scholar]

- Kaplan MS, Huguet N, Caetano R, Giesbrecht N, Kerr WC, McFarland BH, et al. Economic contraction, alcohol intoxication and suicide: analysis of the National Violent Death Reporting System. Injury Prev. 2015:35–41. doi: 10.1136/injuryprev-2014-041215. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Orui M, Sato Y, Tazaki K, Kawamura I, Harada S, Hayashi M, et al. Delayed increase in male suicide rates in tsunami disaster-stricken areas following the Great East Japan Earthquake: a three-year follow-up study in Miyagi Prefecture. Tohoku J Exp Med. 2015:215–22. doi: 10.1620/tjem.235.215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Varin M, Orpana HM, Palladino E, Pollock NJ, Baker MM, et al. Trends in suicide mortality in Canada by sex and age group, 1981 to 2017: a population-based time series analysis. Can J Psychiatry. 2021;66((2)):a population–based time series analysis. doi: 10.1177/0706743720940565. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu L, Capaldi CA, Orpana HM, Kaplan MS, Tonmyr L, et al. Changes over time in means of suicide in Canada: an analysis of mortality data from 1981 to 2018. Changes over time in means of suicide in Canada: an analysis of mortality data from 1981 to 2018. CMAJ. 2021;193((10)):E331–8. doi: 10.1503/cmaj.202378. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vang ZM, Sigouin J, Flenon A, Gagnon A, et al. Are immigrants healthier than native-born Canadians. Ethn Health. 2017;22((3)):209–41. doi: 10.1080/13557858.2016.1246518. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li Z, Page A, Martin G, Taylor R, et al. Attributable risk of psychiatric and socio-economic factors for suicide from individual-level, population-based studies: a systematic review. Soc Sci Med. 2011;72((4)):608–16. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2010.11.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Howarth EJ, O’Connor DB, Panagioti M, Hodkinson A, Wilding S, Johnson J, et al. Are stressful life events prospectively associated with increased suicidal ideation and behaviour. J Affect Disord. 2020:731–42. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2020.01.171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Statistics Canada. Ottawa(ON): Mental health among health care workers in Canada during the COVID-19 pandemic [Internet] Available from: https://www150.statcan.gc.ca/n1/daily-quotidien/210202/dq210202a-eng.htm. [Google Scholar]

- Stanley IH, Hom MA, Joiner TE, et al. A systematic review of suicidal thoughts and behaviors among police officers, firefighters, EMTs, and paramedics. Clin Psychol Rev. 2016:25–44. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2015.12.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patten SB, Kutcher S, Streiner D, Gratzer D, Kurdyak P, Yatham L, et al. Population mental health and COVID- 19: why do we know so little. Can J Psychiatry. 2021:why do we know so little? Can J Psychiatry–44. doi: 10.1177/07067437211010523. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kyung-Sook W, SangSoo S, Sangjin S, Young-Jeon S, et al. Marital status integration and suicide: a meta-analysis and meta-regression. Soc Sci Med. 2018:116–26. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2017.11.053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salway T, Ross LE, Fehr CP, et al, et al. A systematic review and meta-analysis of disparities in the prevalence of suicide ideation and attempt among bisexual populations. Arch Sex Behav. 2019:89–111. doi: 10.1007/s10508-018-1150-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Statistics Canada. Ottawa(ON): Survey on COVID- 19 and Mental Health (SCMH): detailed information for February to May 2021 [Internet] Available from: https://www23.statcan.gc.ca/imdb/p2SV.pl?Function=getSurvey&Id=1295371. [Google Scholar]