Abstract

Recently, gram-negative bacteria isolated from a variety of marine mammals have been identified as Brucella species by conventional phenotypic analysis. This study found the 16S rRNA gene from one representative isolate was identical to the homologous sequences of Brucella abortus, B. melitensis, B. canis, and B. suis. IS711-based DNA fingerprinting of 23 isolates from marine mammals showed all the isolates differed from the classical Brucella species. In general, fingerprint patterns grouped by host species. The data suggest that the marine mammal isolates are distinct types of Brucella and not one of the classical species or biovars invading new host species. In keeping with historical precedent, the designation of several new Brucella species may be appropriate.

Brucellosis is a worldwide zoonotic disease caused by gram-negative bacteria of the genus Brucella. Currently, there are six recognized species of Brucella based on host specificity: B. abortus (cattle), B. canis (dogs), B. melitensis (goats), B. neotomae (desert wood rats), B. ovis (sheep), and B. suis (pigs, reindeer, and hares). The six species have been subdivided into 18 biovars (12, 13) based on a panel of culture and biochemical characteristics (1, 13).

In the last five years, there have been several reports of Brucella species isolated from marine mammals, predominantly seals and cetaceans. Identification was based on serology, morphology, staining, metabolic phenotype, culture characteristics, and phage typing (3, 6, 7, 8, 11, 14, 15). Further characterization of these isolates was crucial because of concerns within the agricultural community about whether marine hosts were reservoir hosts for classical Brucella species that could be transmitted to livestock. The purpose of this study was to genetically characterize Brucella isolated from marine mammals and to compare them to the classical Brucella species and biovars.

Bacteriology.

The Brucella strains used in this report are listed in Table 1. Each isolate was obtained from a separate animal. The history of strains M1068/91, M644/93, M2357/93, M2466/93, 2533/93, 292/94, M336/94, M339/94, M972/94, and M490/95 was described by Foster et al. (7). Phenotypic characterization of these same strains was published by Jahans et al. (11). Strain 1312, isolated from an aborted dolphin fetus, was the same strain characterized by Ewalt et al. (6). Strains 1508 and 98-230 were isolated from different individuals within the same group of captive dolphins as strain 1312. Strain 1508 was isolated from placental tissue following an abortion, while strain 98-230 was isolated from the lung tissue of a dolphin that had died of unrelated causes. Most isolates were obtained from beach-stranded animals posthumously or from captive animals in rehabilitation centers. Except in the two cases involving abortion, none of the isolates were associated with disease symptoms. The classical Brucella strains selected were the designated type strains for species and biovars (12, 13). The strains are available from the National Animal Disease Center (NADC) Brucella Culture Collection and may be requested through the corresponding author (some restrictions may apply as required by law).

TABLE 1.

Bacterial strains used in this study

| Strain designation | Host species | Host location | Sourcea |

|---|---|---|---|

| M1068/91 | Harbour porpoise | Scotland | Foster |

| M644/93 | Common dolphin | Scotland | Foster |

| M2357/93 | Common seal | Scotland | Foster |

| M2466/93 | Common seal | Scotland | Foster |

| M2533/93 | Common seal | Scotland | Foster |

| M292/94 | Common seal | Scotland | Foster |

| M336/94 | Common seal | Scotland | Foster |

| M339/94 | Common seal | Scotland | Foster |

| M972/94 | Common seal | Scotland | Foster |

| M490/95 | Common seal | Scotland | Foster |

| 1312 | Bottlenose dolphin | San Diego, Calif. | G. Miller |

| 1508 | Bottlenose dolphin | San Diego, Calif. | G. Miller |

| 98-230 | Bottlenose dolphin | San Diego, Calif. | G. Miller |

| 96-408 | Harbor seal | Puget Sound, Wash. | Ewalt and NVSLb |

| 96-566 | Harbor seal | Puget Sound, Wash. | Ewalt and NVSL |

| 97-269 | Harbor seal | Snolomish C., Wash. | Ewalt and NVSL |

| 97-324 | Harbor seal | Puget Sound, Wash. | Ewalt and NVSL |

| 98-473 | Harbor seal | Puget Sound, Wash. | Ewalt and NVSL |

| 98-629 | Ringed seal | Baffin Island, Canada | Ewalt and NVSL |

| 98-630 | Ringed seal | Baffin Island, Canada | Ewalt and NVSL |

| 98-631 | Ringed seal | Baffin Island, Canada | Ewalt and NVSL |

| 98-632 | Ringed seal | Baffin Island, Canada | Ewalt and NVSL |

| 98-633 | Harp seal | Madeline Island, Canada | Ewalt and NVSL |

| B. abortus biovar 1 544 | Cow | England | NADC |

| B. abortus biovar 2 86/8/59 | Cow | England | NADC |

| B. abortus biovar 3 Tulya | Cow | Uganda | NADC |

| B. abortus biovar 4 292 | Cow | England | NADC |

| B. abortus biovar 5 B3196 | Cow | England | NADC |

| B. abortus biovar 6 870 | Cow | Africa | NADC |

| B. abortus biovar 9 C68 | Cow | England | NADC |

| B. canis L715 | Dog | United States | NADC |

| B. melitensis biovar 1 16M | Goat | United States | NADC |

| B. melitensis biovar 2 63/9 | Goat | Turkey | NADC |

| B. melitensis biovar 3 Ether | Goat | Italy | NADC |

| B. neotomae | Wood rat | United States | NADC |

| B. ovis ANH3572 | Sheep | Idaho | NADC |

| B. suis biovar 1 1330 | Swine | United States | NADC |

| B. suis biovar 2 Thomsen | Hare | Denmark | NADC |

| B. suis biovar 3 686 | Swine | United States | NADC |

| B. suis biovar 4 40 | Reindeer | Former Soviet Union | NADC |

| B. suis biovar 5 513 | Mouse | Former Soviet Union | NADC |

Strains may be requested from the corresponding author (some restrictions may apply as required by law).

NVSL, National Veterinary Services Laboratory.

Brucella strains were grown either on potato infusion agar or tryptose serum agar plates at 37°C, with or without 5% CO2 depending on strain requirements (1). When cultures achieved light confluence (approximately 3 days growth), cells were harvested by rinsing the agar surface repeatedly with saline (0.85% NaCl in water). Alternatively, the Brucella strains were grown in 30 ml of Trypticase soy broth with 5% bovine serum in a 37°C shaking water bath for 48 to 72 h (1). The cell suspension was centrifuged, and the bacterial pellet was resuspended in saline. Brucella strains grown by either method were killed by the addition of two parts methanol to the saline suspension and were stored in this mixture at 4°C until needed.

DNA sequence of the 16S genes.

One of the genetic targets frequently used for strain identification and strain phylogeny is the rRNA operon, particularly the 16S rRNA gene. These genes are highly conserved and diverge very slowly. The DNA sequences from separate species within a genus will differ by only a few percent. Sequence identity among 16S rRNA sequences is typically interpreted as indicating a single species.

The 16S rRNA genes from isolate M2357/93 (common seal) and from B. abortus biovar 1 544 were amplified by PCR with primers 16S-RNA1 and 16S-RNA2 (Table 2). These were consensus primers (17) based on conserved regions of sequence from other bacteria. DNA was amplified from 105 to 106 killed bacteria (see above) in a 50-μl volume containing 60 mM Tris-HCl (pH 9.0), 15 mM (NH4)2SO4, 1.5 mM MgCl2, 250 μM (each) deoxynucleoside triphosphates, 200 nM each primer, and 1.0 unit Taq polymerase. The Taq polymerase was temporarily deactivated until the first denaturation step by the addition of TaqStart Antibody (Cat # 5400-1; ClonTech Labs Inc., Palo Alto, Calif.). The following parameters were used for 35 cycles of amplification: 95°C for 1.0 min, 45°C for 2.0 min, and 72°C for 2.0 min. The resulting PCR products were cloned into the plasmid pCR 2.1 (designed for PCR products) (Cat #K2000; Invitrogen Corp., Carlsbad, Calif.). The plasmids were replicated in Escherichia coli DH10B (Cat #18290-015; Life Technologies, Gaithersburg, Md.). To correct for Taq polymerase misincorporation during amplification, three positive colonies (in the same orientation with respect to the vector) were pooled prior to sequencing. A 0.5-μg portion of double-stranded plasmid was sequenced by dideoxy chain termination (ABI PRISM dRhodamine Terminator Kit, Cat # 403044; Perkin Elmer/Applied Biosystems, Foster City, Calif.) on an ABI PRISM Model 377 Sequence Instrument (Perkin Elmer/Applied Biosystems). Both strands were analyzed to determine the correct sequence.

TABLE 2.

PCR primer pairs used in this study

| Primer pair | 5′ to 3′ Sequence | Target |

|---|---|---|

| IR-1 | GGC-GTG-TCT-GCA-TTC-AAC-G | IS711 |

| IR-2 | GGC-TTG-TCT-GCA-TTC-AAG-G | |

| 1258-A6 | CCC-TTT-TTT-TTC-AAG-CCC-CTG-C | Marine-specific IS711 and flanking DNA |

| IS591 | TGC-CGA-TCA-CTT-AAG-GGC-CTT-CAT | |

| 16S-RNA1 | AGA-GTT-TGA-TCC-TGG-CTC-AG | 16S RNA |

| 16S-RNA2 | ACG-GCT-ACC-TTG-TTA-CGA-CTT |

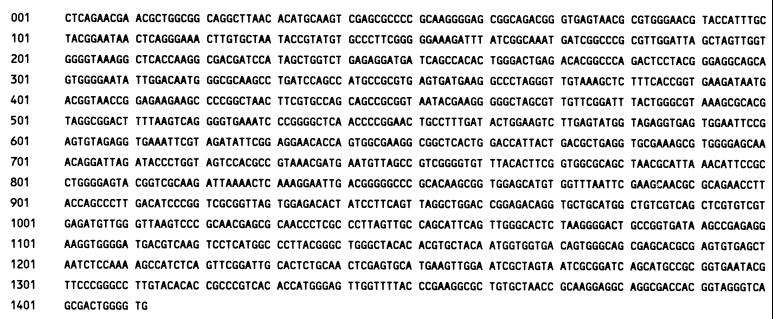

The DNA sequence of the 16S rRNA gene from isolate M2357/93 (GenBank accession no. AF091353) (Fig. 1) was identical to the sequence determined for B. abortus 544 (GenBank accession no. AF091354), confirming that the isolate belonged to the genus Brucella. It should be noted that our sequence for B. abortus 544 differed slightly from the published sequence for B. abortus 11/19 (GenBank accession no. X13695) (5). It is unlikely that this divergence reflected strain differences, since our B. abortus sequence was identical to the homogeneous 16S rRNA sequences of B. canis, B. melitensis, and B. suis, recorded in GenBank (accession no. L37584, L26166, and L26169, respectively) (K. H. Wilson and H. G. Hills, unpublished data). The rRNA sequence of B. ovis (accession no. L26168) (K. H. Wilson, unpublished data) was nearly identical, with a single nucleotide difference.

FIG. 1.

DNA sequence of the 16S rRNA gene from Brucella isolate M2357/93 (common seal). A 1,412-bp sequence of the 16S rRNA locus is presented. The sequence is identical to that determined for B. abortus biovar 1 (strain 544) in this study.

IS711 fingerprinting.

The presence of the mobile genetic element IS711 (GenBank accession no. M94960, also known as IS6501) (9) has been a useful target for molecular characterization of classical Brucella species and biovars (2) based on the number and distribution of IS711 copies within the bacterial genomes. We have previously shown that among classical Brucella species, IS711-based fingerprints are stable, species specific (except B. canis), and to some extent biovar specific (2).

Twenty-three isolates from seven marine host species located in four widely dispersed geographic locations were fingerprinted by Southern blot analysis of EcoRI-digested DNAs from each marine mammal isolate as previously described (2). Fingerprints were generated with a DIG-labeled IS711 probe. The probe was prepared by PCR amplification of an 842-bp fragment containing the entire IS711 element from 75 pg of the plasmid pBO31-I1 (10) per manufacturer's instructions (PCR DIG Probe Synthesis Kit, Cat #1636-090; Boehringer Mannheim Biochemicals Corp., Indianapolis, Ind.). The primers used for PCR are listed in Table 2. The labeled probe was denatured by boiling in hybridization buffer (TBS [100 mM Tris, pH 7.5, and 150 mM sodium chloride] containing 1% blocking reagent [Cat #1096 176; Boehringer Mannheim Biochemicals] and 5% sodium dodecyl sulfate) then allowed to anneal with the membrane blot overnight at 65°C. The membrane was washed, blocked, reacted with anti-DIG-Alkaline Phosphatase-conjugated Fab antibody, and washed as described in the manufacturer's instructions for the DIG Luminescent Detection Kit (Cat no. 1 363 514, Boehringer Mannheim Biochemicals). Luminescence was induced with LumiPhos 530 impregnated substrate sheets (Cat # 78043) per manufacturer's instructions (Schleicher & Schuell, Keene, N.H.). Luminescence was recorded on Kodak X-OMAT film.

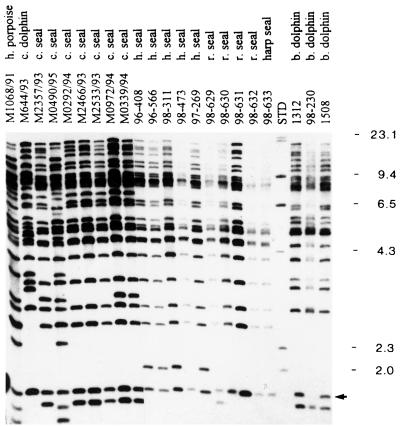

The results, shown in Figure 2, demonstrated that IS711 occurred in every isolate and that each genome contained at least 25 or more copies. There was a general similarity in the fingerprints, but among the 23 isolates, 10 different fingerprints emerged that differed by at least one copy or locus. The fingerprint patterns tended to group by host species, with the exception of the single harp seal isolate (98-633), which was identical to three ringed seal isolates (98-630, 98-631, and 98-632) and one harbor seal isolate (98-473). There was some variability within a host species (e.g., common seal isolates M2357/93, M490/95, and M972/94). Minor variations could be found within a limited geographic location. For example, both 98-473 and 96-408 were isolated from harbor seals in the Puget Sound, and isolates 1312, 98-230, and 1508 were obtained from a small fleet of captive bottlenose dolphins maintained in California.

FIG. 2.

Southern blot analysis of Brucella isolates obtained from marine mammal hosts probed with IS711 DNA. EcoRI genomic digests of 23 Brucella strains were electrophoresed, blotted onto nylon membrane, and probed with DIG-labeled IS711 DNA. Sizes of fragment are given in kilobase pairs on the right side. H. porpoise, harbour porpoise; c. dolphin, common dolphin; c. seal, common seal; h. seal, harbor seal; r. seal, ringed seal; b. dolphin, bottlenose dolphin; and std, size standard (DIG-labeled lambda DNA cut with HindIII). Lanes 1 through 9 contain DNA obtained from hosts in the eastern North Atlantic Ocean or North Sea; lanes 10 through 19 and 21 through 23 contain DNA from hosts found in the eastern Pacific Ocean, Canada, and the western Atlantic Ocean. The arrow indicates a 1.7-kbp fragment common to most isolates. Isolate M336/94 (common seal) is not pictured but has a pattern identical to common seal isolates M972/94 and M339/94.

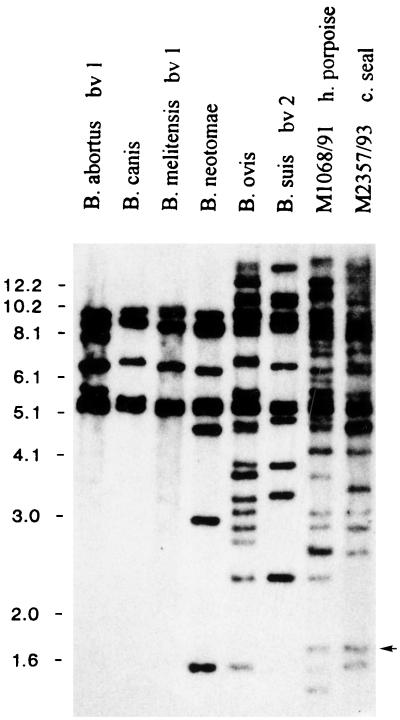

To see how the distribution of IS711 copies within the genomes of marine mammal isolates differed from the classical Brucella species and biovars, two representative marine mammal isolates were directly compared to members from each of the six Brucella species (Fig. 3). For the five biovars of B. suis, the biovar with the most IS711 copies was used. The data showed that the fingerprints from the Brucella isolates derived from marine mammals were quite distinct from the fingerprints of the classical Brucella species. The marine mammal isolates had significantly more copies of IS711 than all classical species except B. ovis. The fingerprint patterns differed extensively from the B. ovis fingerprint.

FIG. 3.

Southern blot analysis of two marine mammal isolates and six classical Brucella species probed with IS711 DNA. EcoRI genomic digests of eight Brucella strains were electrophoresed, blotted onto nylon membrane, and probed with DIG-labeled IS711 DNA. Sizes of fragment are given in kilobase pairs on the right side. The arrow indicates the location of the marine-mammal-specific copy of IS711 used for PCR identification.

The observation that the marine mammal isolates had more copies of IS711 per genome and showed greater diversity in localization of the elements suggests that IS711 elements at some time were more active in the marine mammal isolates than in most terrestrial isolates. Whether this activation is ongoing or related to host adaptation needs to be examined. Despite the differences observed in IS711 fingerprints, there were greater similarities among the isolates from marine animals.

PCR amplification of a DNA sequence specific for marine mammal isolates.

The fingerprints shown in Fig. 2 revealed many fragments that appeared to be common among the isolates from marine mammals but showed no corresponding fragment among the classical isolates (Fig. 3). We wanted to see if at least one of these fragments was from the same locus in each genome and, if so, whether it could serve as a marker for the marine mammal isolates as a group. To promote cloning of the target, we selected a small, 1.7-kb EcoRI fragment (Fig. 2). No corresponding copy was apparent in other Brucella strains (Fig. 3). An EcoRI genomic library of strain M644/93 (dolphin) was created in pBluescript II SK(+) (Cat #212205; Stratagene, La Jolla, Calif.) and was probed for IS711 elements as previously described (2). The DNA flanking the IS711 copy in the selected clone was sequenced. The sequence data was used to develop a locus-specific PCR primer (Table 2).

To determine if this specific copy of IS711 was present in other marine mammal isolates, PCR amplification was performed by using one primer homologous to IS711 and the locus-specific primer. The cycling parameters were 95°C for 2.0 min, followed by 95°C for 10 s, 50°C for 10 s, and 72°C for 1.0 min, for a total of 30 cycles. The predicted product of 375 bp was amplified from all marine mammal isolates (data not shown). No product was amplified from the classical Brucella species and biovars with the exception of B. ovis. Examination of several B. ovis isolates by PCR routinely produced a small quantity of product at the predicted size, suggesting partial but not total homology to the PCR primers (data not shown). Surprisingly, DNA from isolate 98-230 (bottlenose dolphin) did not demonstrate a 1.7-kbp IS711 fragment by Southern blot analysis (Fig. 2) but did amplify large quantities of the DNA sequence targeted by the locus-specific probe.

The demonstration of one and possibly many IS711 loci common to all marine mammal isolates but not their terrestrial counterparts could indicate that the marine mammal isolates may have arisen from a single progenitor strain that differed from the current terrestrial strains. The discovery that B. ovis showed partial homology to the primer specific for marine mammal isolates was unexpected. It may suggest that the marine mammal isolates are closest phylogenetically to B. ovis, or it may be that a copy inserted into the same locus in B. ovis as in the marine mammal isolates by an independent event. Further characterization of the marine mammal isolates at other loci should help illuminate phylogeny.

The results of this study complicate the issue of how to name the new isolates. While the classical Brucella have been grouped into species, ribotyping and other genetic analyses suggest that the Brucella genus is actually monospecific (16). For practical reasons, the species designations have been retained (4). Based on their 16S DNA sequences, the marine mammal isolates appear to belong to the same Brucella monospecies as the classical Brucella strains. If the historical precedence is continued, the marine mammal isolates appear to comprise several new species of Brucella corresponding to diverse marine mammal hosts, and some species may contain more than one subtype.

Acknowledgments

We thank Tonia McNunn and Chad McFadden for technical assistance in preparing purified genomic DNAs. We also thank Allen Jensen for his assistance in the preparation of Brucella cultures.

USDA, Agricultural Research Service, CRIS project 3625-32000-031-00D funded this study.

REFERENCES

- 1.Alton G G, Jones L M, Pietz D E. Monograph series. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization; 1975. Laboratory techniques in brucellosis. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bricker B J, Halling S M. Differentiation of Brucella abortus bv. 1, 2, and 4, Brucella melitensis, Brucella ovis, and Brucella suis bv. 1 by PCR. J Clin Microbiol. 1994;32:2660–2666. doi: 10.1128/jcm.32.11.2660-2666.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Clavareau C, Wellemans V, Walravens K, Tryland M, Verger M J, Grayson M, Cloeckaert A, Letesson J J, Godfroid J. Phenotypic and molecular characterization of a Brucella strain isolated from a minke whale (Balaenoptera acutorostrata) Microbiology. 1998;144:3267–3273. doi: 10.1099/00221287-144-12-3267. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Corbel M J. International committee on systematic bacteriology—subcommittee on the taxonomy of Brucella. Int J Syst Bacteriol. 1988;38:450–452. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Dorsch M, Moreno E, Stackbrandt E. Nucleotide sequence of the 16S rRNA from Brucella abortus. Nucleic Acids Res. 1989;17:1765. doi: 10.1093/nar/17.4.1765. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ewalt D R, Payeur J B, Martin B M, Cummins D R, Miller W G. Characteristics of a Brucella species from a bottlenose dolphin (Tursiops truncatus) J Vet Diagn Investig. 1994;6:448–452. doi: 10.1177/104063879400600408. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Foster G, Jahans K L, Reid R J, Ross H M. Isolation of Brucella species from cetaceans, seals and an otter. Vet Rec. 1996;138:583–586. doi: 10.1136/vr.138.24.583. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Garner M M, Lambourn D M, Jeffries S J, Hall P B, Rhyan J C, Ewalt D R, Polzin L M, Cheville N F. Evidence of Brucella infection in Parafilaroides lungworms in a Pacific harbor seal (Phoca vitulina richardsi) J Vet Diagn Investig. 1997;9:298–303. doi: 10.1177/104063879700900311. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Halling S M, Tatum F M, Bricker B J. Sequence and characterization of an insertion sequence, IS711, from Brucella ovis. Gene. 1993;13:123–127. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(93)90236-v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Halling S M, Zehr E Z. Polymorphism in Brucella spp. due to highly repeated DNA. J Bacteriol. 1990;172:6637–6640. doi: 10.1128/jb.172.12.6637-6640.1990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Jahans K L, Foster G, Broughton E S. The characteristics of Brucella strains isolated from marine mammals. Vet Microbiol. 1997;57:373–382. doi: 10.1016/s0378-1135(97)00118-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Meyer M E, Morgan W J B. Designation of neotype strains and of biotype reference strains for species of the genus Brucella—Meyer and Shaw. Int J Syst Bacteriol. 1973;23:135–141. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Morgan W J, Corbel M J. Recommendations for the description of species and biotypes of the genus Brucella. Dev Biol Stand. 1976;31:27–37. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ross H M, Foster G, Reid R J, Jahans K L, MacMillan A P. Brucella species infection in sea mammals. Vet Record. 1994;134:359. doi: 10.1136/vr.134.14.359-b. . (Letter.) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ross H M, Jahans K L, MacMillan A P, Reid R J, Thompson P M, Foster G. Brucella species infection in North Sea seal and cetacean populations. Vet Record. 1996;138:647–648. doi: 10.1136/vr.138.26.647. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Verger J M, Grimont F, Grimont P A D, Grayson M. Taxonomy of the Genus Brucella. Ann Inst Pasteur Microbiol. 1987;138:235–238. doi: 10.1016/0769-2609(87)90199-2. . (Letter.) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Weisburg W G, Barns S M, Pelletier D A, Lane D J. 16S ribosomal DNA amplification for phylogenetic study. J Bacteriol. 1991;173:697–703. doi: 10.1128/jb.173.2.697-703.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]